Abstract

The aim of this study was to experimentally assess the effect of increased rolling resistance, generated by the Anti-Rollback System, on the muscular load of a manual wheelchair user during downhill movement. Three descent conditions were compared: without the module (NAR), with a flexible roller (EAR), and with a rigid roller (SAR). The experiment was conducted on a 6.3 m ramp inclined at 5°, involving eight adult male participants. Muscle effort was evaluated using three indicators: normalized cumulative muscle load per second (CML/s), normalized muscle activity (EMGnorm), and the peak-to-mean ratio of the EMG signal (PMR). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between configurations (p < 0.05). Use of the module significantly reduced muscular load compared with the reference condition: CML/s decreased by 29.41% in both EAR and SAR, while EMGnorm was reduced by 44.44% in EAR and 50.00% in SAR. PMR reached its lowest value in EAR (4.78), suggesting smoother muscle activation and lower local peak tension. The results indicate that the resistive torque generated by the frictional coupling between the wheelchair tire and the anti-rollback roller, although disadvantageous during propulsion, contributes to improved control and stability during downhill descent, highlighting the system’s dual functional potential.

1. Introduction

A manual wheelchair is a primary mobility tool for individuals with physical disabilities. It enables independent movement, daily activities, and active social participation. Movement is generated through cyclic upper limb actions that provide propulsion and control speed. While many studies focus on uphill propulsion, downhill movement presents significant biomechanical and functional challenges. During descent, the user must control both speed and direction. This places high demands on the upper limbs and may lead to overuse injuries [1,2]. As slope steepness increases, torso and shoulder positioning become more demanding. Users typically increase trunk and shoulder flexion to maintain stability, which can cause fatigue and elevate injury risk [3,4]. Maintaining a constant speed requires braking force, which is especially difficult for older adults or those with reduced upper limb function [5]. Additionally, descent forces the user to adjust posture, including lateral trunk lean and altered shoulder positioning. These changes are crucial for safe and efficient maneuvering. All these factors highlight the need for proper downhill driving technique training [2,6], wheelchair design improvements such as braking assistance or speed control systems [5,7], and environmental adaptations. In the present study, we focused exclusively on a longitudinal downhill slope without any lateral (cross-slope) inclination. This design choice isolates the effects of braking resistance from asymmetric postural stabilization demands that typically arise on outdoor cross-slopes.

Descending a slope in a manual wheelchair is a complex technical task. It requires continuous braking and precise control of the travel path. Braking is achieved by holding the pushrims, which generates high friction forces between the hand and the wheel rim. This heavily engages upper limb muscles, especially in the shoulder girdle and wrists [8,9,10]. Prolonged braking leads to quick fatigue, overuse, and increased injury risk. This is particularly relevant for users with poor trunk control, who struggle to compensate for inertia during sudden stops [11]. Braking forces are not constant and typically peak during the initial phase of free rolling. Additionally, downhill movement increases the risk of instability. Manual wheelchairs are prone to tipping, slipping on inclines, and caster wheel shimmy. These issues elevate the risk of accidents [12,13]. To reduce these negative effects, users adopt compensatory strategies, such as changing trajectory or trunk position. However, such actions can reduce propulsion efficiency and overload the shoulders [2]. Design solutions like braking support systems, automatic stability control, ergonomic pushrims, and downhill driving technique training can significantly improve user comfort and safety.

Despite well-documented biomechanical loads associated with downhill movement in manual wheelchairs [14,15], there is a noticeable lack of technical descriptions and operational studies on descent-supporting solutions in both literature and engineering practice. Most existing research focuses on uphill support. In this context, mechanical and semi-active Anti-rollback Systems play a key role. These systems work through frictional coupling between a roller and the drive wheel [16,17]. Their operation increases rolling resistance due to tire deformation and contact pressure [18,19]. This secondary effect can be interpreted as an auxiliary benefit: the increased rolling resistance functions as a passive braking aid during descent. Prior studies indicate that such effects may enhance wheelchair stability, reduce the risk of losing control, and lower the muscular force required to regulate downhill speed [20,21,22]. Additionally, this resistance may suppress caster wheel shimmy and improve motion smoothness [23]. Despite the potential of these side effects, there is a lack of systematic research analyzing their impact on downhill biomechanics and their engineering application in the form of dedicated design solutions. From a biomechanical standpoint, braking tends to engage flexor-dominant strategies, which are generally weaker than extensor-dominant propulsion patterns. In the present work, we analyzed the same muscle set as in our previous uphill-propulsion experiments (TBM, TBL, ECU, ERC) to maintain methodological consistency and enable direct functional comparison between the assistive (ascent) and resistive (descent) phases of the anti-rollback system. Future studies will extend EMG analysis to flexor-dominant muscles specific to braking to deepen the physiological interpretation of downhill control.

The aim of this study was to experimentally assess the effect of increased rolling resistance, generated by the Anti-rollback System, on the muscular load of a manual wheelchair user during downhill movement. The goal was to experimentally determine whether the auxiliary down-slope effects of the system, originally designed to assist uphill propulsion, could provide functional support as a passive braking aid and improve safety during descent. Three research hypotheses were proposed. The first assumed that use of the system would significantly reduce upper limb muscle activity during descent. The second hypothesized that increased rolling resistance would lower the CML/s index, which reflects cumulative muscular load per second of braking. The third hypothesis assumed that increased rolling resistance would improve muscle coordination, as reflected by a higher PMR value [24]. These assumptions were verified through analysis and processing of surface electromyography (EMG) measurements. The study aimed not only to evaluate the functionality of the existing solution but also to provide insights for designing passive downhill-assist systems in manual wheelchairs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

A key component of the drive system was the set of 24-inch drive wheels with pneumatic tires, mounted without axle camber (0°). A constant tire pressure of 0.7 MPa was maintained by an integrated pressure monitoring and regulation system. The wheels were integrated with the semi-active Vermeiren Trigo T wheelchair (Trzebnica, Poland), with an empty weight of 12 kg, which was additionally equipped with a configurable Anti-rollback System.

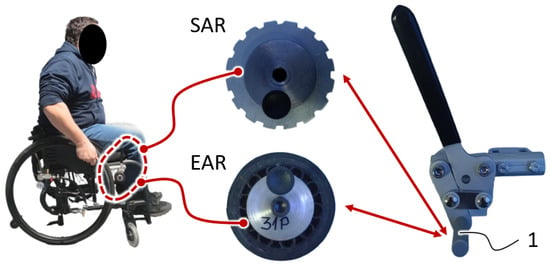

During downhill trials, two configurations of the module were tested (Figure 1): the variant with a rigid roller (SAR) and the variant with a flexible roller (EAR). These variants were compared with descent using the wheelchair without the module (NAR). The module’s design was based on the modification of a classic parking brake, in which the standard pin (1 on Figure 1) was replaced with one of the tested rollers. In the SAR version, a rigid roller with an outer diameter of 60 mm was used, featuring a grooved surface to increase friction. In the EAR variant, a composite roller was used, with a key element being a flexible thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) core with a hardness of 55° Sh, covered with an outer layer of ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) rubber. The EPDM rubber coating had a thickness of 3 mm, while the TPU core featured an inner diameter of 30 mm and an outer diameter of 55 mm. The lattice wall thickness of the elastic core structure was 1 mm. The core had an openwork geometry, which allowed dynamic adaptation to the deformation of the wheel surface and compensation for its local eccentricities. All three variants of the Anti-rollback System were developed as part of the project “Anti-rollback module for manual wheelchairs–functional prototype, operational testing, dissemination” (ID: BEA/000005/BF/2023), funded by the State Fund for Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons (PFRON).

Figure 1.

Experimental wheelchair with anti-rollback module configurations. Left: baseline configuration (NAR); Center: flexible roller module (EAR); Right: rigid roller module (SAR). The photos are supplemented by a schematic technical drawing to illustrate the operating principle of each variant.

During downhill movement using the Anti-rollback System, the roller preload was adjusted to achieve a wheelchair tire deformation (eT) of 2–3 mm. This deformation corresponds to a non-dimensional circumferential strain of approximately 0.7–1.0%, which represents the relative reduction in the wheel radius under load and remains consistent with typical ranges observed for pneumatic wheelchair tires under comparable loading conditions. This preload value was originally determined for the primary function of the anti-rollback module—to prevent unintended backward rolling during uphill propulsion. Preliminary calibration confirmed that a 2–3 mm tire deformation ensures stable frictional coupling between the tire and the roller, preventing slip during spontaneous rollback. The same preload was applied in downhill braking trials to maintain consistent tire–roller contact conditions and allow a direct mechanical comparison between propulsion and braking modes. This approach also reflects real-world system behavior, as anti-rollback modules typically maintain a constant spring force independent of wheel rotation direction. This deformation range provided sufficient frictional coupling between the roller and the tire, eliminating the risk of slippage caused by gravitational force on slopes up to 10°, with a user weight of 100 kg. This setting is essential to ensure the system’s primary function, which is to assist during uphill propulsion.

2.2. Participants

Eight adult males participated in the study, with anthropometric parameters corresponding to the 50th percentile of the population (C50). The sample size (n = 8) was based on previous within-subject EMG reliability studies [25,26], which indicated that 6–10 participants are sufficient for stable normalization and reproducible comparisons of upper-limb muscle activity. This number ensured adequate measurement reliability while maintaining controlled experimental conditions. Each participant was informed of the requirement to refrain from physical activity within the 24 h preceding the tests. To ensure appropriate conditions for electromyographic signal recording, the skin at the electrode placement sites was prepared according to the established procedure: hair was removed, dead skin cells were exfoliated, and the skin surface was cleaned [27,28]. Due to the experimental nature of the prototype solution and its intended use by individuals new to wheelchair use, only participants with full physical ability were included. This approach reduced the risk of potential incidents, as participants were able to exit the wheelchair independently if necessary [29,30]. At the same time, individuals with physical disabilities who were in the early stages of recovery were excluded to avoid any potential psychological burden related to participating in laboratory-based studies.

All volunteers signed informed consent for participation in the study and the publication of results, with full confidentiality ensured. Participant characteristics, including variables such as height, body mass, BMI, and maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), are presented anonymously in Table 1. The project was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences, in accordance with Resolution No. 1100/16 of 10 November 2016, and the study was supervised by Dr. B. Wieczorek under the guidance of Prof. P. Chęciński, MD, PhD.

Table 1.

Summary of the tested participants, where: BMI—body mass index; MVC60%—muscle activity value for voluntary contraction; TBM—caput mediale of the triceps brachii muscle; TBL—caput laterale of the triceps brachii muscle; ECU—extensor carpi ulnaris muscle; ERC—extensor carpi radialis muscle.

2.3. Procedure

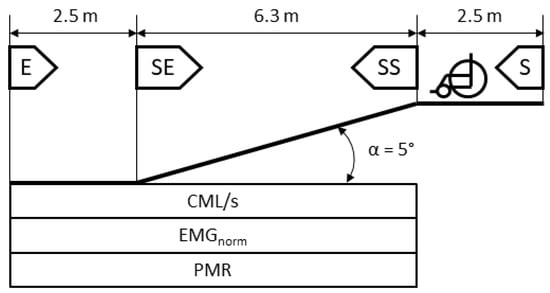

The designed research procedure involved the assessment of user behavior during downhill movement using three wheelchair configurations: without the Anti-rollback System (NAR), with the flexible roller of the Anti-rollback System (EAR), and with the rigid roller of the Anti-rollback System (SAR). The experiment was conducted on a specially prepared test track (Figure 2) located indoors. The track surface was made of smooth oak wood, characterized by a slip resistance value of SRV = 31 [31,32]. The track consisted of three segments: a flat acceleration section (S–SS) 2.5 m in length, an inclined section (SS–SE) 6.3 m long with a slope of 5° ± 0.5°, and a final flat section (SE–E) 2.5 m in length.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the test track used in the study with specification of the analyzed parameters and the segments on which they were measured, where: EMGnorm—value of normalized muscle activity; CML—normalized cumulative muscle load; PMR—peak-to-mean ratio of the EMGnorm signal.

After completing the acceleration phase, the participant positioned himself at point SS, where a single, firm push on the drive rim was performed to initiate motion. Care was taken to ensure that the same push angle and rotational speed were applied in each trial. Participants were instructed to perform one full handrim push immediately before entering the descent and then allow the wheelchair to roll freely while maintaining manual control.

This procedure was selected to ensure participant safety and voluntary control of movement, as enforcing a fixed initial velocity or braking torque would not be ethically acceptable. The experimenters supervised all trials and monitored descent time to verify comparable dynamics across participants. When a participant’s descent duration deviated substantially from the group average, the trial was repeated. After initiating the descent, participants controlled speed and trajectory according to their personal preference. During this phase, the muscular system was engaged in manual braking and directional corrections. The only procedural requirement was a complete stop at the designated endpoint E.

For each device variant, each participant performed three downhill runs, with the configuration order alternated according to the NAR–EAR–SAR sequence, repeated three times. This trial arrangement minimized the influence of order effects (e.g., body warm-up) and reduced the risk of systematic fatigue. The sequence of configurations was counterbalanced using a Latin Square design to minimize potential order effects. Visual inspection of the results confirmed no systematic trend related to trial order, indicating that sequence-related effects were effectively controlled [33]. The participant’s seating position and upper limb alignment relative to the pushrims remained unchanged across all configurations. The Anti-Rollback System did not alter posture or arm geometry; its effect was limited to additional resistive torque generated at the roller–tire interface, which required proportionally higher braking force through the handrim.

The study analyzed the biomechanical load on upper limb muscles during downhill movement in a wheelchair, with particular focus on activity related to braking and trajectory control. Three normalized electromyographic indicators were evaluated, calculated for a single propulsion cycle on the downhill segment (from point SS to SE): relative muscle tension level (EMGnorm), cumulative muscle load (CML), and the peak-to-mean ratio (PMR). The PMR index reflects the ratio of the peak value to the average amplitude of the EMG signal and allows the assessment of the dynamics of muscle effort changes. Electromyographic signals were recorded using the Noraxon TeleMyo DTS wireless system, in combination with double Ag/AgCl surface electrodes. Electrodes were placed over the bellies of selected muscles in accordance with the SENIAM protocol [34]. Before measurements began, an impedance test was performed for each channel (<5 kΩ) [35]. Raw EMG signals were visually inspected to confirm the absence of motion artifacts and to verify baseline stability. All signals were then band-pass filtered (20–450 Hz, 2nd-order Butterworth), full-wave rectified, and smoothed using a moving RMS window of 100 ms. This workflow ensured reliable detection of muscle activation envelopes and minimized noise contamination.

In summary, the EMG procedure included electrode placement following SENIAM guidelines, signal acquisition at 2000 Hz, filtering, rectification, and smoothing prior to normalization to MVC. The derived parameters (EMGnorm, CML/s, and PMR) together provide a quantitative assessment of overall muscular effort, cumulative workload, and activation dynamics. This approach ensured consistent signal interpretation and enabled a comprehensive evaluation of upper limb muscular demand during braking.

2.4. EMG Data Acquisition and Processing

Based on previous studies and literature recommendations [36,37,38,39], muscle activity recording included four upper limb muscle groups: the medial and lateral heads of the triceps brachii (TBM and TBL), the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), and the extensor carpi radialis (ERC). The same muscle set (TBM, TBL, ECU, and ERC) was analyzed here as in our previous experiments conducted during uphill propulsion the primary operational phase of the anti-rollback module. Maintaining identical electrode placements and target muscles ensured methodological consistency and enabled direct, within-study comparison of neuromuscular activation patterns between propulsion and braking tasks, isolating the functional influence of the module itself. During downhill movement, these muscles also perform essential functions related to braking control. The wrist extensor muscles (ECU, ERC) generate controlled eccentric contractions that stabilize the hand on the pushrim and regulate braking torque, while the triceps brachii muscles (TBM, TBL), although not directly locking the elbow joint, assist in trajectory control and compensate for sudden wheel reactions or variations in rolling resistance. This configuration allowed a consistent electrode placement to be used for both ascent and descent phases, ensuring methodological continuity and direct comparison between propulsion and braking conditions. The normalization procedure was performed relative to a reference value, which was the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) of the muscles. MVC recording was conducted with the wheelchair stationary, under conditions reflecting the actual body position during propulsion. Normalization was completed before the main downhill trials, and a rest interval of at least ten minutes was provided between MVC recordings and experimental runs to minimize the potential impact of fatigability. The participant assumed a posture with hands placed on the pushrims at a position 30° forward from the top dead center. The participant then attempted to move the locked wheelchair, which led to maximum activation of the muscles typically involved in propulsion [40,41]. The entire procedure was repeated four times, with each contraction held for 4 s and 5 s rest intervals between trials to reduce fatigue effects. From the recorded EMG signals, segments corresponding to maximum contraction were extracted and standardized in terms of duration, enabling a uniform time base for further calculations. From these processed signals, a submaximal reference level (MVC60%) was calculated. This value represented the mean EMG amplitude corresponding to approximately 60% of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). The procedure was applied to reduce variability associated with transient peaks during full MVC and to provide a more stable normalization baseline, as recommended in recent EMG methodology studies [40,41]. In this article, the term MVC60% is used to denote this normalized submaximal reference value rather than literal 60% exertion of MVC. Simultaneously, a confidence band for a significance level of p = 0.05 was determined to account for natural fluctuations in contraction strength and to provide a stable reference point for the normalization of experimental data.

The previously obtained MVC60% value, together with the corresponding upper confidence limit (UCL, for p = 0.05), served as the reference point for calculating the normalized muscle activity curve EMGₙₒᵣₘ. This process required prior extraction of the EMG signal for the segment from SS to E. Each of these signal fragments was then transformed to a common time base, expressed as a percentage of the total time taken to travel the designated section of the track. This procedure made it possible to determine the average EMG signal and its amplitude. As a result, the function avg. EMG(t) was obtained, describing average muscle activity over time during descent. Based on this, proper normalization was carried out using the MVC60% value increased by the UCL as the baseline. Finally, the EMGₙₒᵣₘ(t) curve (1) was obtained, expressed as a function of the percentage of descent duration, which enabled quantitative comparison of results between different participants and test conditions in a biomechanically relevant and consistent manner.

Under the conditions of the conducted experiment, in which participants performed downhill movement in a wheelchair, the analysis of parameters enabling continuous and movement-phase-independent assessment of muscle activity was of key importance. One such indicator was the cumulative muscle load (CML) (2), which was calculated as the total area under the curve of the normalized EMG signal during descent from point SS to E. This parameter can be considered an indicator of the energy demand of the muscles, particularly in tasks with a predominantly eccentric-isometric character, such as braking during downhill motion. CML values correlate well with actual energy expenditure under dynamic and submaximal conditions, as confirmed in the biomechanical literature [42,43,44].

Additionally, the peak-to-mean ratio (PMR) was analyzed as a supplementary indicator. We acknowledge that PMR is sensitive to random signal fluctuations and may not fully capture coordination quality [reviewer’s remark]. Therefore, it was used only in combination with more robust indicators (CML, EMGnorm) to provide a complementary perspective on local peak activations rather than as a primary outcome variable. Its analysis allows the assessment of muscle overload or defensive strategies related to sudden trajectory corrections. The third important indicator was the maximum value of the normalized EMG signal () (4). This parameter made it possible to determine the peak muscular effort reached during descent and was particularly useful for comparisons between the tested wheelchair configurations.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in MATLAB R2023b (Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox). Exact p-values and effect sizes (partial η2 for ANOVA, Cohen’s d for post hoc comparisons) are reported. A post hoc power analysis based on observed effect sizes (α = 0.05, two-tailed) confirmed sufficient power (>0.80) for all main effects.

3. Results

3.1. CML and CML/s Results

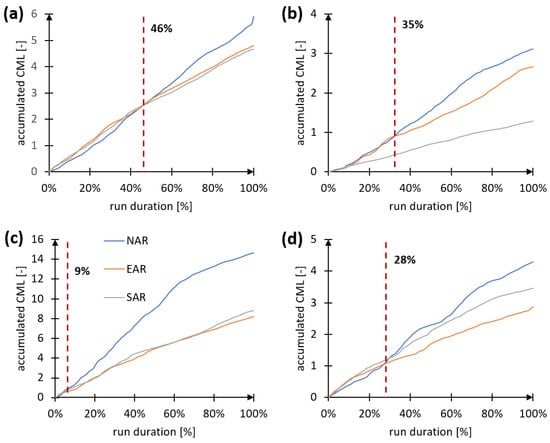

The CML and CML/s parameters are calculated as the integral of the EMG signal amplitude over time. During each trial, the descent duration was recorded to confirm comparable dynamic conditions among participants. The mean descent times were NAR = 9.9 ± 2.1 s (CV = 21%), EAR = 10.4 ± 1.9 s (CV = 18%), and SAR = 8.9 ± 1.0 s (CV = 11%), indicating moderate differences between systems but consistent performance within each configuration. This supports the interpretation that the observed differences in EMG and CML/s reflect muscular effects rather than timing artifacts. Therefore, they can be interpreted as EMG-based indicators proportional to metabolic energy expenditure, reflecting the total and instantaneous muscular energy cost, respectively. In this sense, the term “energy expenditure” used in the present study refers to the functional interpretation of muscle effort derived from EMG analysis, rather than a direct measurement of metabolic energy. When analyzing the accumulated CML value throughout the entire duration of the descent (Figure 3), a pattern was observed in which the initial phase of descent with the Anti-rollback System showed a more rapid rate of CML accumulation. This trend was visible across all participants. On average, 46% of the descent duration elapsed before the accumulated CML value for the NAR configuration exceeded those for SAR and EAR. In most participants, the most effective reduction in CML accumulation was observed with the use of the SAR (rigid roller) variant. The average difference in the rate of CML accumulation between the SAR and EAR rollers was 4.33%.

Figure 3.

CML accumulation graphs as a function of the percentage of descent duration, with the averaged intersection point marked where CML accumulation for NAR exceeds that of SAR and EAR. Where: (a)—mean values from all tested participants, (b)—participant M04, (c)—participant M01, (d)—participant M02.

An analysis of the CML growth rate, expressed as the slope angle of the CML accumulation trend during descent, showed that effort increased most rapidly in the no-module (NAR) condition, with an average slope of 3.41°. The next configuration was EAR, with a slope of 2.73°, representing a 19.9% reduction. For the SAR module, the average slope was 2.65°, corresponding to a 22.3% reduction.

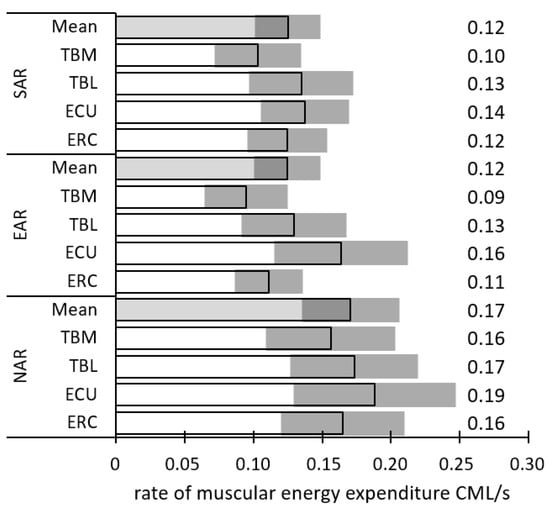

The results of the CML/s index analysis (Figure 4, Table 2) confirm the beneficial effect of using the Anti-rollback System on reducing energy consumption during descent. This effect is consistent with previous observations regarding CML accumulation. The NAR variant showed the highest mean CML/s level, amounting to 0.17 ± 0.036. The introduction of rolling resistance via the EAR or SAR module reduced this value to 0.12, corresponding to a 29.4% decrease compared to NAR. A narrowing of the confidence intervals was also observed in both module variants, which may indicate a more consistent muscular response and more stable effort conditions.

Figure 4.

Mean values of the CML/s index for four upper limb muscles: TBM (caput mediale of the triceps brachii muscle), TBL (caput laterale of the triceps brachii muscle), ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris muscle), and ERC (extensor carpi radialis muscle) in three descent variants: without assistance (NAR), with the Anti-rollback System using a flexible roller (EAR), and with a rigid roller (SAR). The shaded area represents the confidence interval of the measurement for p = 0.05.

Table 2.

Summary of CML/s index values for the following muscles: TBM (caput mediale of the triceps brachii muscle), TBL (caput laterale of the triceps brachii muscle), ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris muscle), ERC (extensor carpi radialis muscle), CI (confidence interval), and the average energy load for the upper limb (CMLarm/s) in three descent variants: without assistance (NAR), with the Anti-rollback System using a flexible roller (EAR), and with a rigid roller (SAR).

The highest CML/s values in the NAR variant were observed in the TBL muscle (caput laterale musculi tricipitis brachii), where they reached 0.19. The EAR module reduced CML/s for this muscle to 0.16 (−15.8%) and to 0.09 in the ERC muscle (musculus extensor carpi radialis), representing a 43.8% reduction. In the TBM (triceps brachii–medial head), the decrease was 31.3%, while in the ECU (musculus extensor carpi ulnaris) it was 23.5%. The SAR variant also resulted in reductions across all muscles: 37.5% in ERC, 25% in TBM, 26.3% in TBL, and 23.5% in ECU. The most effective effort reduction was observed in the TBL and ERC muscles, especially in the SAR variant. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, after confirming normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test). Post hoc Tukey tests were applied where significant main effects were observed. For example, differences in CML/s between NAR, EAR, and SAR were significant (F = 6.01, p = 0.0177). All reported values represent subject means across three trials, not pooled data. The differences between the NAR, EAR, and SAR variants are not random but result from the specific characteristics of the applied technical solution.

To verify that the reduction in EMG activity was not associated with slower motion, descent duration and mean velocity were calculated for each configuration. The mean descent times were 9.97 ± 1.90 s for NAR, 10.27 ± 1.64 s for EAR, and 8.95 ± 0.92 s for SAR, corresponding to mean velocities of 0.89 ± 0.17 m/s, 0.86 ± 0.14 m/s, and 0.99 ± 0.10 m/s, respectively. Despite slight inter-configuration differences, the intra-condition variability was small, confirming that participants maintained comparable descent dynamics. Additionally, the analysis of CML/s, which quantifies the rate of cumulative muscle load, showed consistent configuration-related differences independent of descent duration, confirming that lower EMG levels reflected reduced muscular effort rather than slower motion. ANOVA confirmed a significant main effect of configuration on CML/s (F(2,14) = 6.01, p = 0.018, ηₚ2 = 0.46). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant reductions for both EAR and SAR compared with NAR (p < 0.01, d = 1.0–1.2), whereas EAR–SAR differences were not significant (p > 0.05).

3.2. EMGnorm Results

The values of normalized muscle activity EMGnorm (Table 3) allowed for the comparison of muscle workload intensity regardless of individual differences in maximum contraction level (MVC60%). The average EMGnorm activity in the NAR variant was 0.18 (±0.070), indicating the highest level of effort among the analyzed configurations. The EAR variant reduced the average value to 0.10 (±0.019), while SAR reached 0.09 (±0.018), showing the lowest mean muscle tension. The reduction compared to NAR amounted to 44.4% for EAR and 50.0% for SAR. The observed decrease in EMGnorm values was present across all tested muscles, with the most notable reduction in the ERC muscle (extensor carpi radialis), where the value dropped from 0.16 to 0.07 (EAR, −56.3%) and to 0.08 (SAR, −50.0%). In the TBL muscle (caput laterale of the triceps brachii), EMGnorm decreased from 0.22 to 0.12 for EAR (energy demand reduction of 45.5%) and to 0.10 for SAR (reduction of 54.5%). In the TBM muscle (caput mediale of the triceps brachii), the reduction was 43.8% for both module variants, while in the ECU muscle (extensor carpi ulnaris), the metabolic energy demand decreased by 47.4%.

Table 3.

Summary of normalized muscle activity (EMGnorm) values for the following muscles: TBM (triceps brachii–medial head), TBL (triceps brachii–lateral head), ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris muscle), ERC (extensor carpi radialis muscle), CI (confidence interval), and the mean normalized muscle activity for the entire upper limb (EMGarm) in three descent variants: without assistance (NAR), with the Anti-rollback System using a flexible roller (EAR), and with a rigid roller (SAR).

The significance of the effect of the Anti-rollback System on muscle activity level (EMGnorm) during descent was confirmed by a one-way ANOVA, which showed a statistically significant difference between the values obtained in the NAR, EAR, and SAR variants (p = 0.00027). At the same time, an additional analysis did not reveal any significant differences in the distribution of load among individual muscles depending on the Anti-rollback System variant (p = 0.757). Thus, the reduction in muscle tension occurred uniformly across the entire muscular system, without compensatory overload of any of the analyzed muscle groups. The configuration effect on EMGnorm was statistically significant (F(2,14) = 11.4, p = 0.001, ηₚ2 = 0.45). Post hoc tests indicated that both EAR and SAR significantly differed from NAR (p < 0.01, d = 1.1–1.4), while the difference between EAR and SAR was not significant (p > 0.05). These values confirm a strong and consistent reduction in muscular effort induced by the Anti-rollback System.

3.3. PMR Results

The PMR (peak-to-mean ratio) values were also analyzed. This indicator describes the ratio of the maximum to the average amplitude of the normalized EMG signal and allows for the assessment of the dynamics of muscle tension changes during trajectory control and braking (Table 4). The mean PMR value for the entire upper limb was highest in the SAR variant, amounting to 5.43 (±0.45). The NAR variant showed a value lower by 2.0% (5.32 ± 0.46), while the EAR variant demonstrated a 12.0% reduction (4.78 ± 0.99). This indicates that only the EAR configuration effectively limited the occurrence of sudden muscle tension spikes.

Table 4.

Summary of peak-to-mean ratio (PMR) values for the following muscles: TBM (caput mediale of the triceps brachii muscle), TBL (caput laterale of the triceps brachii muscle), ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris muscle), ERC (extensor carpi radialis muscle), CI (confidence interval), and the mean value for the entire upper limb (PMRarm) in three descent variants: without assistance (NAR), with the Anti-rollback System using a flexible roller (EAR), and with a rigid roller (SAR).

In the analysis of individual muscles, the highest PMR values were recorded for the ERC muscle (extensor carpi radialis), with values of 6.58 in NAR, 6.14 in EAR (a decrease of 6.7%), and 6.80 in SAR (an increase of 3.3%). The EAR variant led to a PMR reduction in all muscles, with the most significant decrease observed in TBM (caput mediale of the triceps brachii), where the reduction was 23.6%, and in TBL (caput laterale of the triceps brachii), where PMR decreased by 11.9%. A slight increase of 1.0% was noted only in the ECU muscle (extensor carpi ulnaris).

The SAR variant showed a less consistent muscle response: PMR in TBM decreased by 5.8%, while in TBL and ERC it increased by 6.2% and 3.3%, respectively, and in ECU by 4.6%. Only the EAR variant demonstrated a uniform reduction in peak muscle tension. Although the SAR variant was generally effective, it showed increases in PMR in selected muscles.

The one-way ANOVA did not show a statistically significant effect of the descent variant (NAR, EAR, SAR) on the PMR index value (F = 0.57; p = 0.58669). This indicates that the observed differences in mean PMR values between the Anti-rollback System variants may result from individual descent style and wheelchair handling, including sudden trajectory corrections or compensatory responses [45,46,47]. Although the main ANOVA result was not significant (F(2,14) = 0.57, p = 0.587, ηₚ2 = 0.08), the EAR variant showed a moderate within-subject reduction in PMR relative to NAR (d ≈ 0.7), suggesting smoother activation dynamics in most participants. It should be noted that the observed variations in EMG activity during braking do not primarily reflect differences in metabolic energy expenditure but rather changes in local muscular strain and eccentric loading, which may be more directly associated with the risk of overuse or micro-lesions in the upper limb.

4. Discussion

The analysis of cumulative effort values (CML) and their rate of increase (CML/s) revealed clear differences between the three tested descent variants. The NAR variant, in which the Anti-rollback System was not used, reached the highest values for both indicators. The CML/s value was 0.17, and the slope angle of the CML trend line reached 3.41°. This indicates the need for continuous regulation of wheel rotation and maintenance of an appropriate movement trajectory using the upper limbs. Effective control of the wheelchair on a slope, both during ascent and during descent, requires coordinated work of flexor and extensor muscle groups [48,49], however in the present study only the activity of the triceps brachii and the wrist extensor muscles extensor carpi ulnaris and extensor carpi radialis was recorded. These muscles generate propulsion during ascent, and they also stabilize the upper limb on the handrim and maintain a steady movement trajectory during descent, which was important for evaluating the auxiliary stabilizing effect of the anti-rollback module. The experimental protocol required participants to perform repeated ascent and descent cycles with continuous EMG recording, therefore electrode repositioning between phases was not possible. For this reason, the analysis was limited to muscle groups for which reliable and uninterrupted signal acquisition could be ensured throughout the entire test cycle. Such a propulsion–braking strategy, when sustained on steep segments, leads to rapid fatigue, impaired muscle coordination, and overload. As a result, the risk of upper limb injuries increases significantly [36,50]. The EAR and SAR variants, equipped with the Anti-rollback System, allowed for a reduction in both indicators. The EAR variant achieved a CML/s value of 0.12 and a CML trend line slope of 2.73°. The SAR variant showed the same CML/s value (0.12), with a trend slope of 2.65°. These values indicate a lower rate of effort buildup when passive braking-assist systems are used during descent [51]. In terms of these dependent variables, the EAR variant demonstrated greater effectiveness, as the flexible roller does not cause sudden increases in rolling resistance. These resistances are a common effect of surface contact between the roller and the wheelchair wheel with significant roundness deviations [17,19]. The deformability of the flexible roller contributes to smoother and more comfortable motion. The average percentage of descent duration in which CML values in the NAR variant were higher than in the EAR and SAR variants was 46%. This shows that the differences between variants occur over a significant portion of the descent. However, it should be noted that in the initial phase of descent, CML values in the EAR and SAR variants were occasionally higher than in NAR. This may be related to the need to overcome rolling resistance during the initial acceleration of the wheelchair. In practice, this means that the user may experience greater muscular load on horizontal sections separating two adjacent descents.

The results concerning normalized muscle activity (EMGnorm) allow for the evaluation of the impact of the Anti-rollback System on muscle tension levels [52,53]. The NAR variant, in which the system was not used, showed the highest mean EMGarm value for the entire upper limb, equal to 0.18. This indicates that during descent without assistance, the upper limb muscles operated at an average intensity equal to 18% of maximum tension. The introduction of the Anti-rollback System resulted in a significant reduction in this value. In the EAR variant, the mean value dropped to 0.10, corresponding to a 44.4% reduction compared to NAR. In the SAR variant, a value of 0.09 was obtained, representing a 50.0% reduction. These percentage reductions in normalized average EMG for the upper limb directly translate into a significant and meaningful decrease in physical effort [54,55] required to slow down the wheelchair during descent.

The decrease in EMGnorm values was observed across all analyzed muscles. The largest reduction was noted in the ERC muscle (extensor carpi radialis), where muscle tension decreased from 0.16 in NAR to 0.07 in EAR and 0.08 in SAR. The reduction in muscle activity for this muscle is significant because it plays a major role in wheelchair propulsion [56], particularly during ramp ascent and descent [57]. Considering the importance of this muscle in the biomechanics of wheelchair propulsion [58,59], lowering its load minimizes the risk of injuries [60] that could impair the user’s ability to operate the manual drive system. In the TBM muscle (caput mediale of the triceps brachii), values dropped from 0.16 to 0.09 in both the EAR and SAR variants. A decrease in activity was also observed in the TBL (caput laterale of the triceps brachii) and ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris) muscles, indicating a uniform reduction in tension across the entire analyzed muscular system. These differences were confirmed by statistical analysis. The p-value was 0.00027, confirming a significant effect of the Anti-rollback System on muscle tension during descent. These results highlight the auxiliary down-slope effect of rolling resistance introduced by the Anti-rollback System: while not its primary purpose, this mechanism effectively reduces the muscular effort required to control speed during downhill movement. Under real-world conditions, this helps reduce fatigue [61] and enhances the safety of the wheelchair user [62].

The peak-to-mean ratio (PMR) enables the assessment of the dynamics of muscle tension changes and serves as a complement to indicators describing the level of average load [63]. Its value depends not only on the force generated, but primarily on upper limb kinematics [64] and wheelchair propulsion technique [65]. The statistical analysis performed did not reveal significant differences between the NAR, EAR, and SAR variants (p = 0.58669), indicating that the presence of the Anti-rollback System does not have a clear effect on reducing PMR values. The observed changes should be interpreted as dependent on the muscular system’s response to varying resistance and on adaptive speed control strategies. Impulse-like muscle activations, resulting from trajectory corrections, sudden stabilization reactions, or postural compensations, can increase PMR despite an overall reduction in physical effort. This pattern was observed in the SAR variant, where EMGnorm and CML/s values decreased, but PMR increased for the ERC muscle from 6.58 (NAR) to 6.80, and for the TBL muscle from 4.71 to 5.00. In contrast, the EAR variant showed a consistent reduction in PMR across all muscles, including 23.6% in TBM and 11.9% in TBL, which may qualitatively reflect smoother muscle activation. However, due to the high intra-individual variability and sensitivity of PMR to movement execution, this indicator should be regarded as an auxiliary descriptive parameter rather than direct evidence of motor coordination quality. Its interpretation requires reference to the user’s individual driving style and upper limb propulsion mechanics, which may vary depending on user experience, environmental conditions, and descent characteristics. Although PMR did not show statistically significant differences between configurations, it was included as a complementary, descriptive indicator illustrating potential fluctuations in neuromuscular activation patterns during wheelchair braking, without implying causal differences in coordination between configurations. A comprehensive evaluation of the NAR, EAR, and SAR variants was conducted based on four biomechanical indicators of muscular system performance: CML, CML/s, EMGnorm, and PMR. For each of these parameters, not only the measured values obtained in the study were considered, but also their maximum allowable physiological limits. The maximum for CML was set at 15 units, corresponding to 15 s of muscle work at full engagement (EMGnorm = 1). For CML/s, the maximum value was set at 1, indicating constant full-force muscle load throughout the entire descent. EMGnorm refers to maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), and therefore its maximum is 1. The PMR value, as a peak tension indicator, was limited to 10, which corresponds to a tenfold instantaneous increase in amplitude relative to the mean.

To account for the importance of each variable in terms of safety, ergonomics, and measurement reliability, a weighting system was applied: CML = 0.25, CML/s = 0.35, EMGnorm = 0.35, and PMR = 0.05. Criteria with greater diagnostic significance and lower susceptibility to the influence of driving style (CML/s and EMGnorm) were assigned higher weights. In contrast, PMR, as the variable most dependent on upper limb kinematics, was given the lowest weight. For each variant, partial scores were calculated using a Formula (5) that allows normalization on a scale from 0 to 1:

where: Fi′—normalized score of the i-th criterion, Fi—actual score of the i-th criterion, Fi−max—maximum allowable value of the actual score for the i-th criterion, wi—weight of the i-th criterion.

The adopted evaluation criteria and the maximum values of the analyzed indicators made it possible to assess the variants in terms of muscular system load, where a score of 1 represents the worst result—indicating the highest muscular load—and a score of 0 represents the best result (Table 5).

Table 5.

Partial and overall scores of the Anti-rollback System variants.

The evaluation results clearly indicate that the SAR and EAR variants, both equipped with the Anti-rollback System, effectively reduce muscular effort compared to descent without assistance (NAR). The highest load-reduction efficiency was demonstrated by the SAR variant, which achieved the lowest total score (0.7495), primarily due to a strong reduction in cumulative effort (CML) and average muscle tension (EMGnorm). The EAR variant, with a slightly higher total score (0.6960), achieved very good results in reducing effort intensity (CML/s and EMGnorm), and notably was the only one to significantly lower the PMR, indicating greater stability and smoother muscle activity. The reference NAR variant, with the highest total score (0.8085), showed the greatest muscular load, especially in terms of CML, which confirms the rationale for using rolling resistance during descent. From the perspective of effort reduction, SAR is the most effective variant, whereas EAR may offer better neuromechanical comfort and lower peak overload.

The article aligns with the current scientific trend focused on the development of rehabilitation devices, prosthetics, and manually operated machines which, if not properly adapted to the user, can lead to increased musculoskeletal load [66] and higher energy expenditure during task performance. The findings of this study position the proposed anti-rollback module as a complementary innovation within the broader context of wheelchair technology development. While existing active and electronically controlled braking systems offer adjustable resistance and real-time feedback, they often increase system complexity, cost, and energy demand. In contrast, the present design provides a purely mechanical, self-acting resistance mechanism that enhances stability and braking control without external power or user intervention. This solution therefore complements current mechanical systems by providing passive support for both uphill propulsion and controlled downhill motion. Such an approach aligns with current trends in assistive mobility design, emphasizing simplicity, reliability, and user independence.

The study was conducted with able-bodied participants, as the tested anti-rollback module was at a prototype stage and the downhill braking trials involved a potential risk of instability or fall. This approach allowed participants to evacuate safely from the wheelchair if needed. The device is intended primarily for novice wheelchair users, individuals who typically have limited propulsion experience; therefore, the recruitment of participants unfamiliar with wheelchair use was justified to simulate this user profile. From an ethical standpoint, it would not be appropriate to involve individuals who are newly adapting to wheelchair mobility, as this period often follows a traumatic event associated with loss of independent locomotion. The results should therefore be interpreted as representing controlled laboratory conditions rather than clinical testing in disabled populations.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of an Anti-rollback System on the biomechanical load of upper-limb muscles during downhill movement in a manual wheelchair. Three descent configurations were compared. The reference configuration did not include the module, whereas the other two introduced rolling resistance generated by a flexible or a rigid roller. It was assumed that this resistance would reduce the need for active braking and consequently decrease muscular load. The results confirmed that both module configurations reduced the intensity and average level of muscular effort. EMGnorm and CML/s values decreased by 44% and 50% in the EAR and SAR variants for EMGnorm and by 29% for CML/s in both variants. A reduction in cumulative effort expressed by the CML index also indicated a lower overall muscular demand. No statistically significant differences were observed in the PMR index, which showed high inter-individual variability, although the EAR variant was the only one to reduce PMR across all muscles, which may indicate smoother muscle activation. The study has several limitations. Only extensor-dominant muscles were recorded, because the experimental protocol required uninterrupted EMG acquisition during repeated uphill and downhill cycles, and electrode repositioning between phases was not possible. As a result, muscle groups involved in braking through flexion could not be assessed. The experiment was conducted with able-bodied participants in controlled laboratory conditions, which limits direct generalization to everyday wheelchair users and real-world environments. The anti-rollback module was evaluated only in a straight downhill task, and factors such as cross-slopes, surface irregularities or environmental variability were not included. Future work will address these limitations. A complementary study focused on uphill propulsion has already been accepted for publication, and both datasets will be used to develop a dedicated comparative analysis of ascent and descent. Planned research will also include a wider set of muscle groups, redesigned electrode placement optimized for braking mechanics, and tests involving novice wheelchair users as well as outdoor conditions. These efforts will help verify the stabilizing potential of the Anti-rollback System under more diverse and ecologically valid settings. The present findings provide initial evidence that the Anti-rollback System can reduce muscular load during descent and may support safer and more stable downhill control, especially when precise upper-limb coordination is required. Although the observed effects are promising, broader studies are needed to confirm the functional and clinical relevance of this solution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and Ł.W.; methodology, B.W., M.G. and Ł.W.; software, B.W. and Ł.W.; validation, B.W., M.G. and Ł.W.; formal analysis, B.W. and Ł.W.; investigation, B.W. and Ł.W.; resources, B.W. and Ł.W.; data curation, B.W. and Ł.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W. and Ł.W.; writing—review and editing, B.W. and Ł.W.; visualization, B.W.; supervision, B.W.; project administration, B.W.; funding acquisition, B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PFRON (Poland State Fund for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons), grant number “BEA/000068/BF/D” and “Reverse Locking Module for Wheelchairs— Functional Prototype, Operational Testing, Popularization”.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Resolution No. 1100/16, 10 November 2016). All participants were informed about the experimental procedures and objectives, and provided written informed consent to participate in the study and for the publication of the results. The research involved non-invasive measurements only.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Richter, W.M.; Rodriguez, R.; Woods, K.R.; Axelson, P.W. Consequences of a Cross Slope on Wheelchair Handrim Biomechanics. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assila, N.; Rushton, P.W.; Duprey, S.; Begon, M. Trunk and Glenohumeral Joint Adaptations to Manual Wheelchair Propulsion over a Cross-Slope: An Exploratory Study. Clin. Biomech. 2024, 111, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, D.; Babineau, A.-C.; Champagne, A.; Desroches, G.; Aissaoui, R. Trunk and Shoulder Kinematic and Kinetic and Electromyographic Adaptations to Slope Increase during Motorized Treadmill Propulsion Among Manual Wheelchair Users with a Spinal Cord Injury. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 636319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway, C.S.; Symonds, A.; Suzuki, T.; Gall, A.; Smitham, P.; Taylor, S. Linking Wheelchair Kinetics to Glenohumeral Joint Demand during Everyday Accessibility Activities. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–17 July 2015; Volume 2015, pp. 2478–2481. [Google Scholar]

- Heerwan, P.M.; Shahrom, M.A.; Ishak, M.I.; Kato, H.; Narita, T. Investigation of the Performance of Plugging Braking System as a Hill Descent Control (HDC) for Electric-Powered Wheelchair. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2023, 20, 10906–10916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.A.; Tucker, S.M.; Klaesner, J.W.; Engsberg, J.R. A Motor Learning Approach to Training Wheelchair Propulsion Biomechanics for New Manual Wheelchair Users: A Pilot Study. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradon, D.; Garrec, E.; Vaugier, I.; Weissland, T.; Hugeron, C. Effect of Power-Assistance on Upper Limb Biomechanical and Physiological Variables During a 6-Minute, Manual Wheelchair Propulsion Test: A Randomised, Cross-Over Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 6783–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvier, T.; Louessard, A.; Simonetti, E.; Hybois, S.; Bascou, J.; Pontonnier, C.; Pillet, H.; Sauret, C. Manual Wheelchair Biomechanics While Overcoming Various Environmental Barriers: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lin, Y.-S.; Hogaboom, N.S.; Wang, L.-H.; Koontz, A.M. Relationship between Linear Velocity and Tangential Push Force While Turning to Change the Direction of the Manual Wheelchair. Biomed. Tech. 2017, 62, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavens, B.A.; Jahanian, O.; Schnorenberg, A.J.; Hsiao-Wecksler, E.T. A Comparison of Glenohumeral Joint Kinematics and Muscle Activation During Standard and Geared Manual Wheelchair Mobility. Med. Eng. Phys. 2019, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, T.D.; Ricard, M.D. Effects of Trunk Functional Capacity on the Control of Angular Momentum During Manual Wheelchair Braking. Open Sports Sci. J. 2022, 15, e2208150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, S.J.; Dahlstrom, R.J.; Condon, J.P.; Hedin, D.S. Yaw Rate and Linear Velocity Stabilized Manual Wheelchair. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; pp. 878–881. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.; Borisoff, J.; Sparrey, C.J. Manual Wheelchair Downhill Stability: An Analysis of Factors Affecting Tip Probability. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Marciniak, A. The Symmetry of the Muscle Tension Signal in the Upper Limbs When Propelling a Wheelchair and Innovative Control Systems for Propulsion System Gear Ratio or Propulsion Torque: A Pilot Study. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabryelski, J.; Kurczewski, P.; Sydor, M.; Szperling, A.; Torzyński, D.; Zabłocki, M. Development of Transport for Disabled People on the Example of Wheelchair Propulsion with Cam-Thread Drive. Energies 2021, 14, 8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Kukla, M.; Warguła, Ł.; Giedrowicz, M.; Rybarczyk, D. Evaluation of Anti-Rollback Systems in Manual Wheelchairs: Muscular Activity and Upper Limb Kinematics during Propulsion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Kukla, M.; Rybarczyk, D.; Warguła, Ł. Evaluation of the Biomechanical Parameters of Human-Wheelchair Systems During Ramp Climbing with the Use of a Manual Wheelchair with Anti-Rollback Devices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwarciak, A.M.; Yarossi, M.; Ramanujam, A.; Dyson-Hudson, T.A.; Sisto, S.A. Evaluation of Wheelchair Tire Rolling Resistance Using Dynamometer-Based Coast-Down Tests. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J.; Wilson-Jene, H.; Koontz, A.; Pearlman, J. Evaluation of Rolling Resistance in Manual Wheelchair Wheels and Casters Using Drum-Based Testing. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauret, C.; Vaslin, P.; Lavaste, F.; de Saint Remy, N.; Cid, M. Effects of User’s Actions on Rolling Resistance and Wheelchair Stability During Handrim Wheelchair Propulsion in the Field. Med. Eng. Phys. 2013, 35, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deves, M.; Poulet, Y.; Hays, A.; Faupin, A.; Sauret, C. Are Manual Wheelchair Rear Wheel Rolling Resistance and Friction (in)-Dependent of Load, Tire Pressure, and Camber Angle? An Evaluation Across Different Surfaces. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 2415–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, E.; Kloosterman, M.G.M.; Buurke, J.H.; Rietman, J.S.; Janssen, T.W.J. Rolling Resistance and Propulsion Efficiency of Manual and Power-Assisted Wheelchairs. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavacece, M. Distribution of the Residual Tolerable Imbalance Between Correction Plans. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 52, 9757–9774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, S.J.; Polgar, J.M.; Dickerson, C.R.; Callaghan, J.P. Trunk Muscle Activity During Wheelchair Ramp Ascent and the Influence of a Geared Wheel on the Demands of Postural Control. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, T.I.; Mulloy, F.; Gibbon, K.C.; Stone, M.R.; Thompson, K.G. Reliability of Electromyography During 2000 m Rowing Ergometry. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murley, G.S.; Menz, H.B.; Landorf, K.B.; Bird, A.R. Reliability of Lower Limb Electromyography during Overground Walking: A Comparison of Maximal- and Sub-Maximal Normalisation Techniques. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merletti, R.; Cerone, G.L. Tutorial. Surface EMG Detection, Conditioning and Pre-Processing: Best Practices. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2020, 54, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferriere, P.; Lemaire, E.D.; Chan, A.D.C. Surface Electromyographic Signals Using Dry Electrodes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2011, 60, 3259–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peula, J.M.; Urdiales, C.; Herrero, I.; Fernandez-Carmona, M.; Sandoval, F. Case-Based Reasoning Emulation of Persons for Wheelchair Navigation. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 56, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.; Gooch, S.D.; Theallier, D.; Dunn, J. Analysis of a Lever-Driven Wheelchair Prototype and the Correlation between Static Push Force and Wheelchair Performance. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 9895–9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B.; Krystofiak, T.; Sydor, M. Impact of Surface Finishing Technology on Slip Resistance of Oak Lacquer Wood Floorboards with Distinct Gloss Levels. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 19, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majka, J.; Sydor, M.; Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B. Anti-Slip Properties of Thermally Modified Hardwoods. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2024, 83, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.V. Complete Counterbalancing of Immediate Sequential Effects in a Latin Square Design. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchor-Uceda, I.A.; Gutierrez-Gnecchi, J.A.; Olivares-Rojas, J.C.; Reyes-Archundia, E.; Gonzalez-Vazquez, A. Principal Component Regression and Partial Least Squares Regression Evaluation of Electrode Performance for Non-Invasive Multimodal Measurement of Arm Muscle Activity. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC), Ixtapa, Mexico, 18–20 October 2023; Volume 7, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sae-lim, W.; Phukpattaranont, P.; Thongpull, K. Effect of Electrode Skin Impedance on Electromyography Signal Quality. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Chiang Rai, Thailand, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 748–751. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Wakeling, J.; Grange, S.; Ferguson-Pell, M. Coordination Patterns of Shoulder Muscles During Level-Ground and Incline Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Rehabilitation Res. Dev. 2013, 50, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Ferguson-Pell, M.; Lu, Y. The Effect of Manual Wheelchair Propulsion Speed on Users’ Shoulder Muscle Coordination Patterns in Time-Frequency and Principal Component Analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, B.; Warguła, Ł.; Gierz, L.; Zharkevich, O.; Nikonova, T.; Sydor, M. Electromyographic Analysis of Upper Limb Muscles for Automatic Wheelchair Propulsion Control. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2024, 100, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiuk, Z.; Błaszczyszyn, M.; Piechota, K.; Nowicki, T. Movement Patterns of Polish National Paralympic Team Wheelchair Fencers with Regard to Muscle Activity and Co-Activation Time. J. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 82, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, B.; Gyemi, D.L.; Brydges, E.; Stefanczyk, J.M.; Kahelin, C.; Burkhart, T.A.; Andrews, D.M. Comparison of Upper Extremity Muscle Activation Levels Between Isometric and Dynamic Maximum Voluntary Contraction Protocols. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sports Sci. 2019, 7, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Beltran Martinez, K.; Golabchi, A.; Tavakoli, M.; Rouhani, H. A Dynamic Procedure to Detect Maximum Voluntary Contractions in Low Back. Sensors 2023, 23, 4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Forsman, M.; Enquist, H.; Olsen, H.B.; Søgaard, K.; Sjøgaard, G.; Østensvik, T.; Nilsen, P.; Andersen, L.L.; Jacobsen, M.D.; et al. Frequency of Breaks, Amount of Muscular Rest, and Sustained Muscle Activity Related to Neck Pain in a Pooled Dataset. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraga-García, B.; Lozano-Berrio, V.; Gutiérrez, Á.; Gil-Agudo, Á.; del-Ama, A.J. A Systematic Methodology to Analyze the Impact of Hand-Rim Wheelchair Propulsion on the Upper Limb. Sensors 2019, 19, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amancio, A.; Leonardi, F.; de Toleto Fleury, A.; Ackermann, M. The Influence of Inertial Forces on Manual Wheelchair Propulsion. In Proceedings of the DINAME 2017, São Sebastião, Brazil, 5–10 March 2017; Fleury, A.d.T., Rade, D.A., Kurka, P.R.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 459–469. [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczyszyn, M.; Piechota, K.; Borysiuk, Z.; Kręcisz, K.; Zmarzły, D. Correlation Analysis of Upper Limb Muscle Activation in the Frequency Domain in Wheelchair Fencers. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1523358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, C.M.; Cohn, B.A.; Valero-Cuevas, F.J. Temporal Control of Muscle Synergies Is Linked with Alpha-Band Neural Drive. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 3385–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, S.; Rogowski, I.; Champely, S.; Hautier, C. Reliability of EMG Normalisation Methods for Upper-Limb Muscles. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-C.; Lee, M.-H.; Yoo, J.-S. Effect of the Height of a Wheelchair on the Shoulder and Forearm Muscular Activation During Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2012, 24, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.P.; Wakeling, J.; Grange, S.; Ferguson-Pell, M. Effect of Velocity on Shoulder Muscle Recruitment Patterns During Wheelchair Propulsion in Nondisabled Individuals: Pilot Study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 49, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boninger, M.L.; Koontz, A.M.; Sisto, S.A.; Dyson-Hudson, T.A.; Chang, M.; Price, R.; Cooper, R.A. Pushrim Biomechanics and Injury Prevention in Spinal Cord Injury: Recommendations Based on CULP-SCI Investigations. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2005, 42, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.A.D.A.; Ackermann, M.; Leonardi, F. Effects of a closed-loop partial power assistance on manual wheelchair locomotion. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.Y.; Echeimberg, J.O.; Pompeu, J.E.; Lucareli, P.R.G.; Garbelotti, S.; Gimenes, R.O.; Apolinário, A. Root Mean Square Value of the Electromyographic Signal in the Isometric Torque of the Quadriceps, Hamstrings and Brachial Biceps Muscles in Female Subjects. J. Appl. Res. 2010, 10, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, K.C.; Heroux, M.E.; Gandevia, S.C.; Butler, J.E.; Diong, J. Estimation of Maximal Muscle Electromyographic Activity from the Relationship Between Muscle Activity and Voluntary Activation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, R.; Yunoki, T.; Arimitsu, T.; Lian, C.S.; Roghayyeh, A.; Matsuura, R.; Yano, T. Relationship Between Effort Sense and Ventilatory Response to Intense Exercise Performed with Reduced Muscle Glycogen. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Oliveira, A.S.C. Effects of Elbow Flexor Muscle Resistance Training on Strength, Endurance and Perceived Exertion. Hum. Mov. 2013, 14, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, C.-R. Comparison of Neck and Upper-Limb Muscle Activities between Able-Bodied and Paraplegic Individuals During Wheelchair Propulsion on the Ground. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-C.; Lee, M.-H. Effect of Wheelchair Seat Height on Shoulder and Forearm Muscle Activities during Wheelchair Propulsion on a Ramp. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2012, 24, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.W.; Richter, W.M.; Neptune, R.R. Individual Muscle Contributions to Push and Recovery Subtasks During Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Naito, A. Co-Contraction of the Pronator Teres and Extensor Carpi Radialis during Wrist Extension Movements in Humans. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2007, 17, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, N.A.C.; Correa, C.O.; Mercado Chaparro, M.D.C.; Gallego, A.M.V.; Moreno, J.L.; Velásquez, A.T. Measurement of the Strength of Upper Limbs in Cervical Injury Users to Design a Propulsion Wheelchair Mechanism. In Proceedings of the VII Latin American Congress on Biomedical Engineering CLAIB 2016, Bucaramanga, Colombia, 26–28 October 2017; Volume 60, pp. 686–689. [Google Scholar]

- Togni, R.; Zemp, R.; Kirch, P.; Plüss, S.; Vegter, R.J.K.; Taylor, W.R. Steering-by-Leaning Facilitates Intuitive Movement Control and Improved Efficiency in Manual Wheelchairs. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.; Mortenson, B.; Sawatzky, B. Starting and Stopping Kinetics of a Rear Mounted Power Assist for Manual Wheelchairs. Assist. Technol. 2019, 31, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sy, A.C.; Bugtai, N.T.; Domingo, A.D.; Liang, S.-Y.M.V.; Santos, M.L.R. Effects of Movement Velocity, Acceleration and Initial Degree of Muscle Flexion on Bicep EMG Signal Amplitude. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Cebu City, Philippines, 9–12 December 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H. Upper Limb Dynamics during Manual Wheelchair Propulsion with Different Resistances. In Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of Biomechanics (WCB 2010), Singapore, 1–6 August 2010; Volume 31, pp. 632–635. [Google Scholar]

- Kwarciak, A.M.; Turner, J.T.; Guo, L.; Richter, W.M. The Effects of Four Different Stroke Patterns on Manual Wheelchair Propulsion and Upper Limb Muscle Strain. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2012, 7, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B.; Giedrowicz, M.; Kukla, M.; Nati, C. Wood Chippers: Influence of Feed Channel Geometry on Possibility of Musculoskeletal System Overload. Croat. J. Eng. 2025, 46, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).