3.1. LIDAR-Based EDR and Comparison with Modeling Results

This section concerns the LIDAR-based estimation of EDR and compares two model-derived EDR methods: (i) EDR from the model’s prognostic turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) equation, and (ii) EDR estimated using a subfilter-scale reconstruction (SFSR) approach [

20]. The comparison spans six sites across Hong Kong, providing a general assessment of which model-derived EDR is more suitable under tropical cyclone conditions.

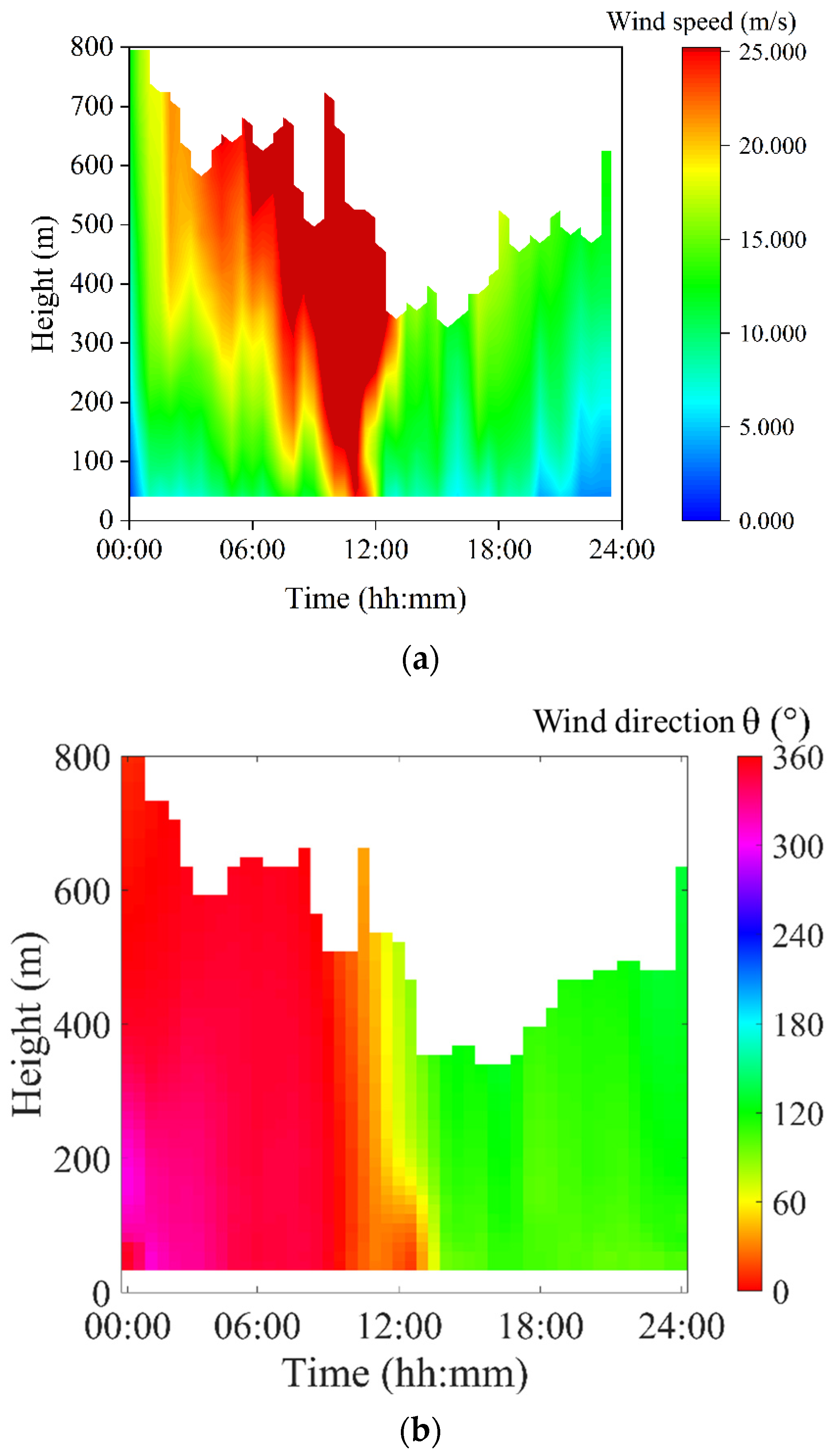

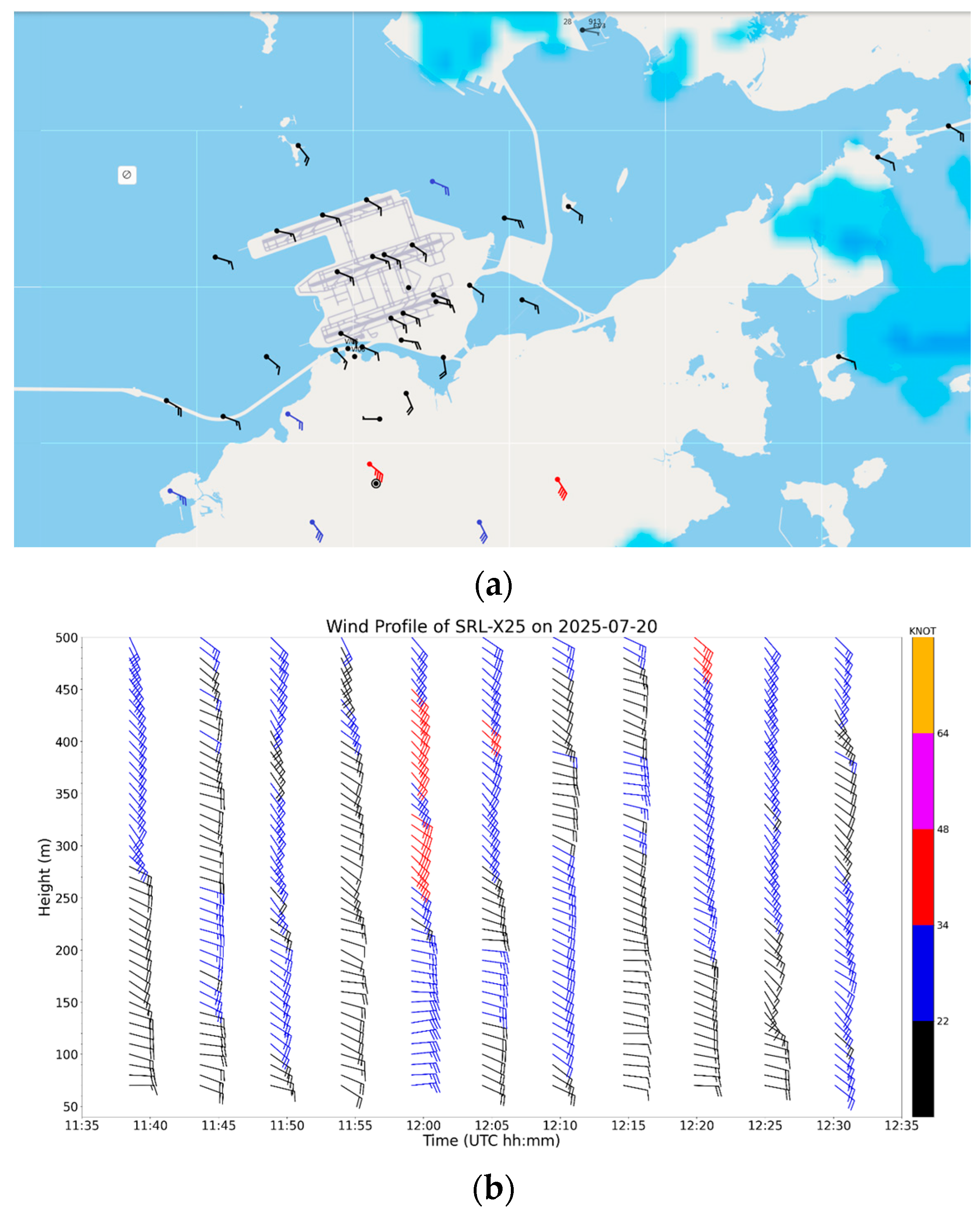

An example of vertical wind profiles measured by LIDAR at Bui O (BO) in the southern part of Lantau Island is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1a gives the time-height plot of horizontal wind speed. There was a descending jet with wind speed exceeding 25 m s

−1 following the approach of Wipha, with the strongest winds from approximately 10:00 to 12:00 Hong Kong Time (HKT) on 20 July 2025 (HKT = UTC + 8 h). Following the departure of Wipha, wind speed decreased rapidly at all heights. The time-height plot of horizontal wind direction is shown in

Figure 1b, displaying the rapid change in wind direction from north to south following the passage of Wipha’s eye across BO.

To compute the EDR from LIDAR measurements, 10-min mean wind profiles were used. For each 10-min averaging period, individual measurements of the three wind components were available every 15 s. As such, the 15-s updating wind data could be used to construct a time series to calculate EDR using the spectral method, following [

12]. Because wind direction can vary rapidly near a tropical cyclone, nonstationary periods were screened following [

21]. A candidate segment was rejected if either (i) the difference between the scalar and vector mean wind speeds exceeded 0.51 m s

−1, or (ii) the standard deviation of wind direction exceeded 10°. Only segments passing these criteria were used in the spectral fit. After quality control, EDR was estimated directly from Doppler velocity spectra. A Fourier transform was applied to the 15-s time series to obtain the velocity power spectrum,

, which was fitted to a generalized power-law model:

where

is the frequency,

is the Kolmogorov constant, and

is a fitted spectral slope. EDR can then be obtained by taking the cube root of

.

The hourly vertical profile of EDR derived from LIDAR in BO is shown in

Figure 1c. When Wipha was closest to BO, EDR below a height of approximately 300 m was highest, reaching approximately 1.1 m

2/3s

−1 at 12:00–13:00 HKT. This high turbulence could be associated with local terrain because there are mountains as high as 1000 m above mean sea level north of BO on Lantau Island. This is also attributable to the high turbulence within the surface layer of the typhoon, especially following the change in wind direction to southerly winds without much upstream terrain blockage.

A high-resolution NWP with a horizontal resolution of approximately 1 km was performed using the Regional Atmospheric Modeling System (RAMS) version 6.3, nested with the reanalysis of the European Centre of Medium Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) following the method described in [

22]. At a horizontal resolution of 1 km, the Deardorff turbulence parameterization scheme [

23] was adopted, in which the EDR is directly computed from the prognostic TKE equation. In the inertial subrange, the dissipation rate

is a function of TKE and the integral scale of turbulence

L, based on Kolmogorov’s theory:

where

is the TKE. In the Deardorff scheme,

is related to the subgrid-scale (SGS) mixing length

via

, with

, and

and

denote the grid spacings in the x-, y-, and z-directions, respectively. EDR can then be obtained by taking the cube root of

. In this study, RAMS was configured to output the instantaneous EDR field and other variables every minute.

Alternatively, the SFSR technique [

20] was applied to the RAMS output data to calculate the time-height contour of EDR at BO. This method estimates EDR by applying an explicit top-hat filter [

24] to the model-resolved three-dimensional velocity field and reconstructing the resolvable sub-filter-scale (RSFS) motions through a truncated deconvolution. The reconstructed RSFS TKE and the SGS TKE, which are calculated from the strain-rate and rotation-rate tensors of the resolved model velocity fields using a nonlinear backscatter and anisotropy model [

25], are combined to obtain the total TKE. The total TKE is then converted to EDR via Equation (1). In SFSR, the integral scale of turbulence is taken as

, where λ is a flow-dependent quantity. A constant value of 8 was set for λ in this work following [

20].

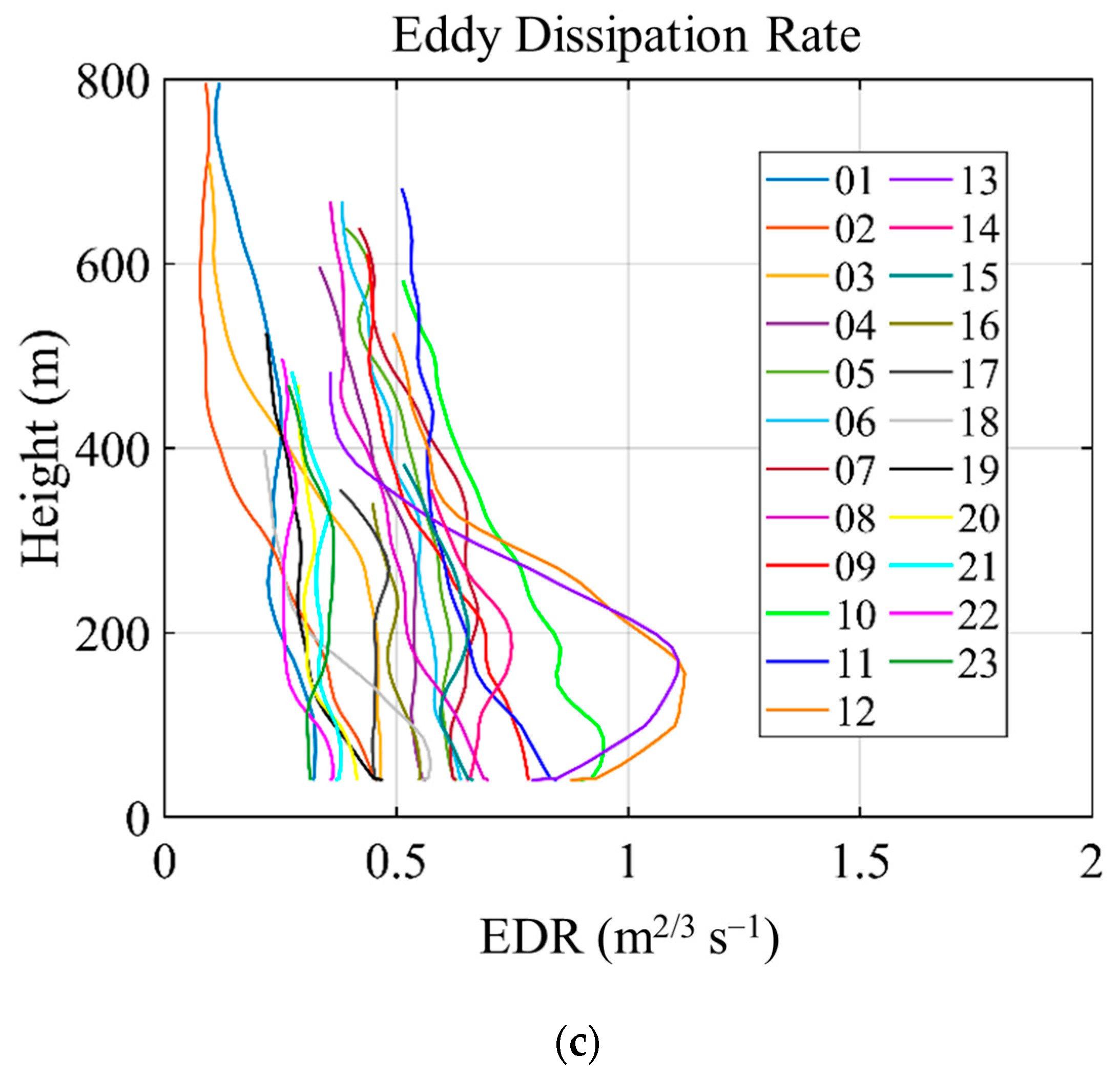

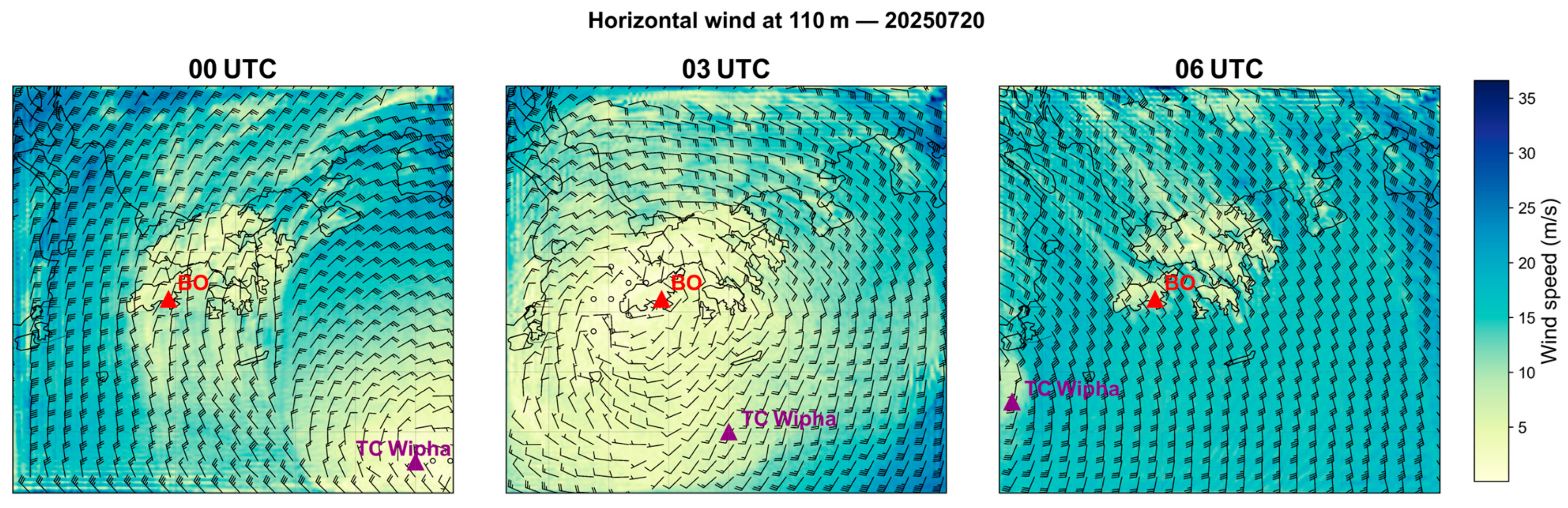

The time-height plot of EDR from LIDAR measurement at BO is shown in

Figure 2a.

For comparison, the EDR derived from RAMS’s prognostic TKE equation and SFSR are shown in

Figure 2b and

Figure 2c, respectively. It can be seen that both have some deficiencies in comparison with observations in

Figure 2a; namely, the direct RAMS output failed to give higher turbulence between 10 a.m. and noon on 20 July 2025, whereas the SFSR technique generally underestimated EDR.

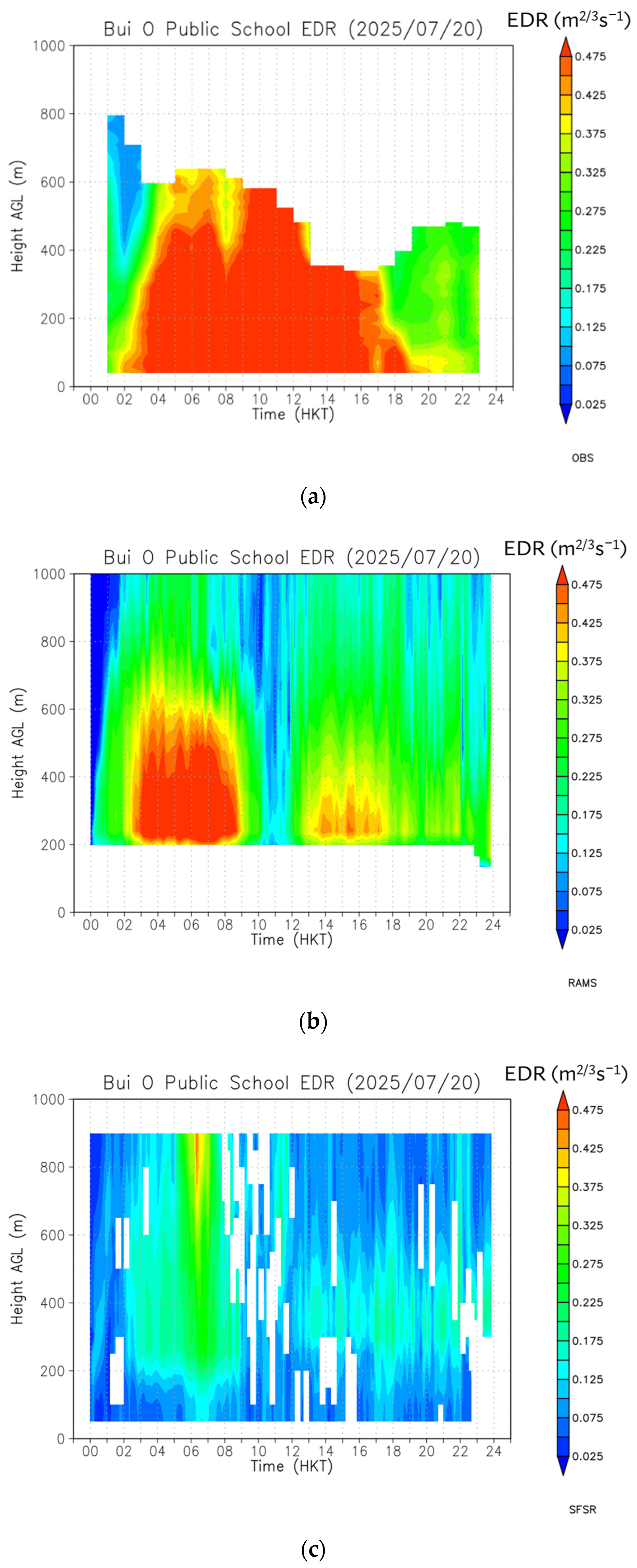

The underestimation of turbulence by the direct RAMS output between 10:00 and 12:00 HKT (02–04 UTC) on 20 July 2025 is mainly attributed to position errors in the simulated TC.

Figure 3 compares the horizontal wind fields at 110 m simulated by RAMS with the Hong Kong Observatory’s operational analysis position of tropical cyclone Wipha. At 00 UTC, the model reproduced the observed northerly winds at BO reasonably well, although the simulated TC center was slightly displaced from the analyzed location. By 03 UTC, however, the simulated TC had migrated northward toward Lantau Island, placing BO near the TC’s center where weaker winds prevailed in the model. In reality, Wipha remained about 60 km south of Hong Kong, and BO lay within the eyewall region, experiencing stronger winds and higher turbulence as indicated by the LIDAR-derived EDR in

Figure 2a. Consequently, the simulated EDR showed a spurious decrease during this period (

Figure 2b). As Wipha moved away from Hong Kong, the positional discrepancy lessened by 06 UTC, the simulated wind direction shifted correctly to southeasterly, and the model-derived EDR aligned more closely with both the observations. This demonstrates model-derived EDR is highly sensitive to TC position errors, especially when the circulation center is close to the observing site; track bias can even invert the temporal trend of EDR, underscoring the need for careful interpretation of the model results.

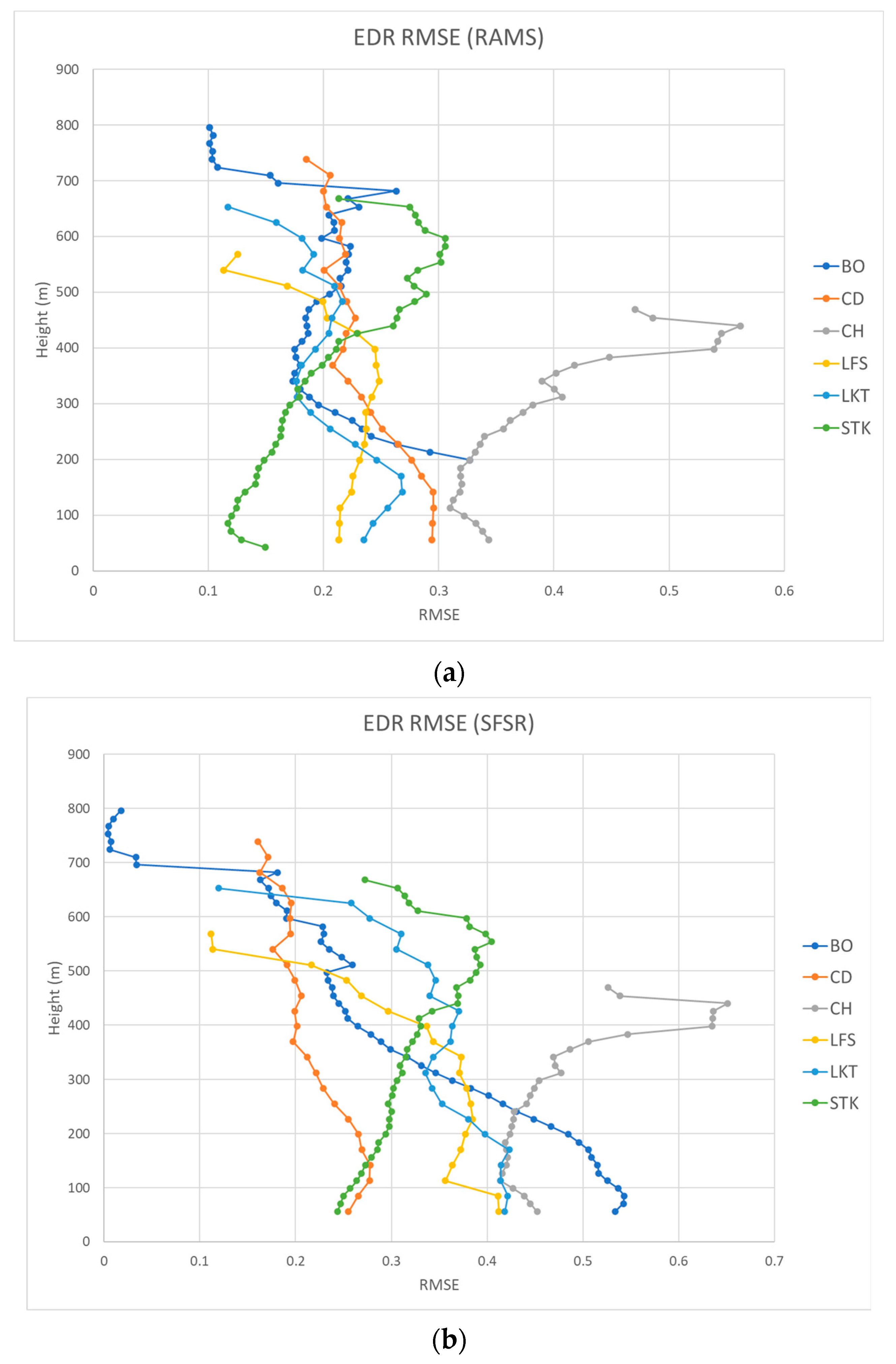

To quantitatively compare EDRs from RAMS direct output and SFSR methods, we calculated the root-mean-square errors (RMSEs) of EDRs against LIDAR observations at six locations in Hong Kong for the whole day of 20 July 2025, when Typhoon Wipha impacted the territory. The results are shown in

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b, respectively. In general, the former had smaller errors, with RMSEs mostly in the region of 0.1 to 0.3 m

2/3 s

−1. In contrast, the latter had slightly larger RMSEs in the region of around 0.2 to 0.5 m

2/3 s

−1. A distinct peak in the EDR error at approximately 400 m was found for both methods at the CH site, which was likely caused by the limited number of LIDAR retrievals around those altitudes instead of local terrain effect or systematic model bias. The differences between the RAMS and SFSR EDR estimates are examined in greater detail in the next section using higher-frequency radiosonde data.

3.2. Radiosonde-Based EDR and Comparison with Modeling Results

Similar to

Section 2, which compared LIDAR-derived and model-derived EDR, this section analyzes turbulence characteristics obtained from high-resolution radiosonde measurements to provide an independent observational reference for model evaluation. Compared with LIDAR, radiosonde measurements offer much finer vertical resolution, enabling a more detailed examination of the vertical structure of EDR and providing valuable insight into small-scale turbulence features within the atmospheric boundary layer [

26,

27,

28]. Radiosonde observations with a two-second sampling interval from King’s Park in Hong Kong were used to calculate the vertical profile of the EDR following the Thorpe method [

29], which has been applied to radiosonde data over the United States and shown to be comparable to the flight-derived EDR [

30].

In the Thorpe method, temperature inversions in the potential temperature

profile are first reordered to a monotonically increasing profile. The resulting vertical displacements of

are the Thorpe displacements, and the root-mean-square value of the Thorpe displacement is the Thorpe scale

, which represents the local overturning scale. Assuming a linear relationship between

and the Ozmidov scale

[

31], the turbulent energy dissipation rate

can be determined as

, where

is an empirical constant and set to 1.0,

is the Brunt-Väisälä frequency.

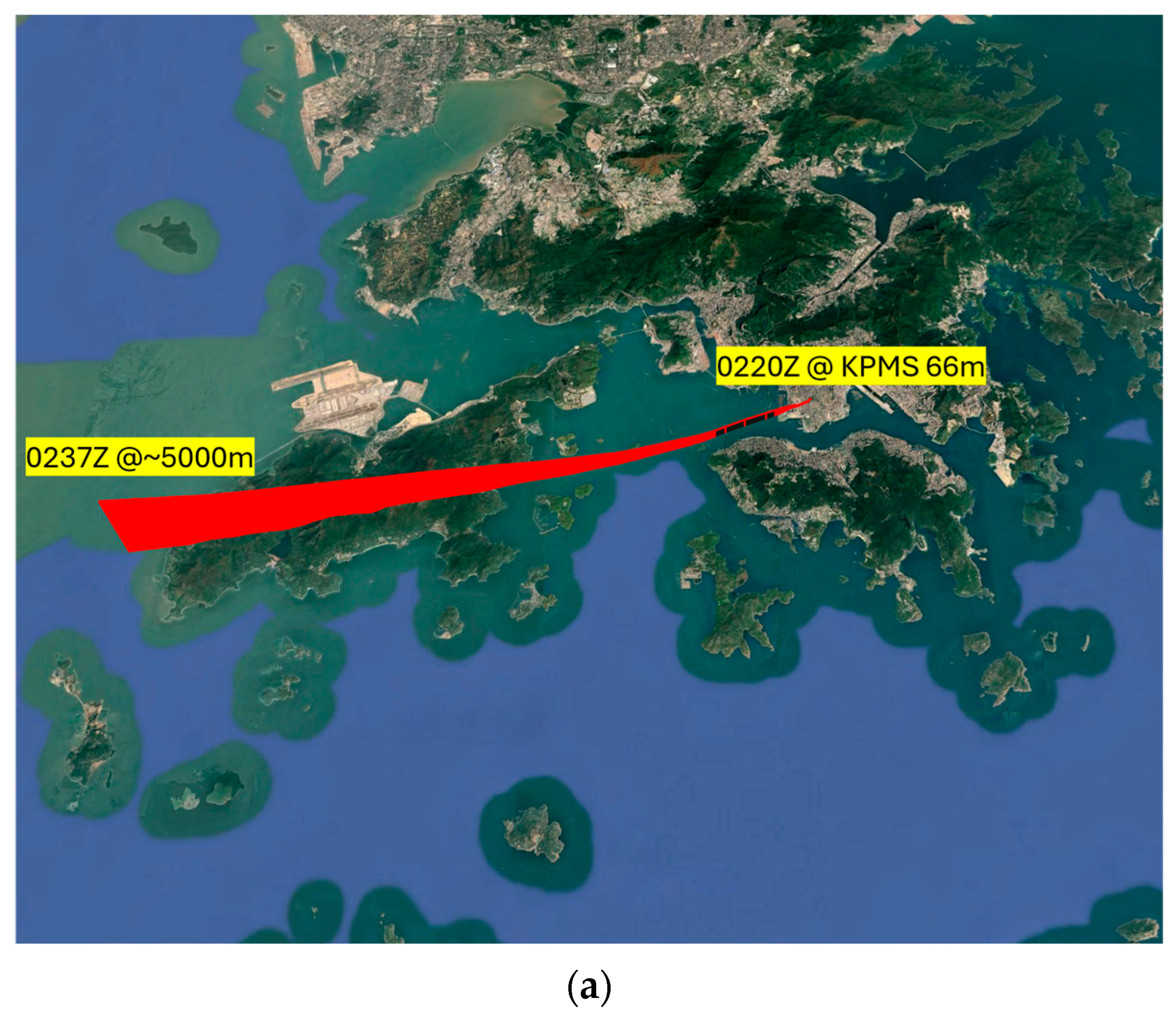

An example of the radiosonde track launched during Typhoon Wipha is shown in

Figure 5a. To facilitate model comparison, the one-minute RAMS outputs were temporally and spatially interpolated along the ascending track of the radiosonde. Following

Section 2, two sets of model-derived EDR profiles were analyzed: (i) the prognostic EDR directly available from the TKE equation in RAMS and (ii) the EDR reconstructed using the SFSR technique.

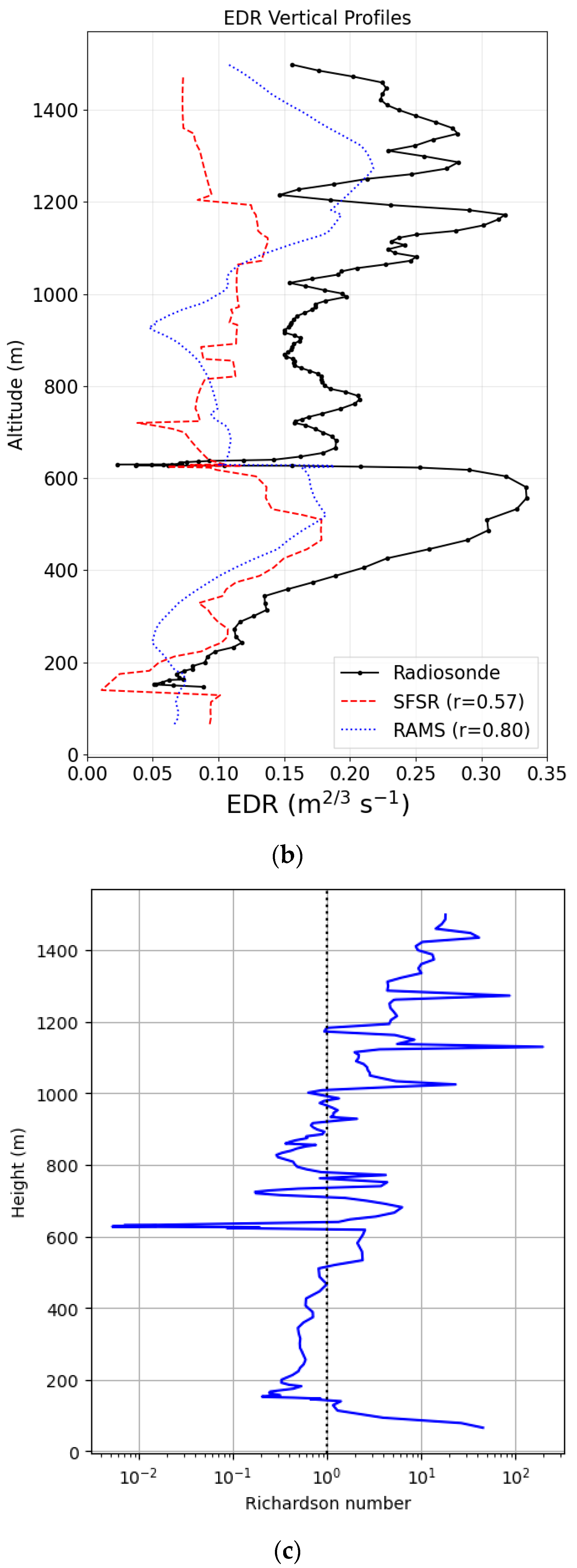

Figure 5b shows the vertical profile of EDR from radiosonde measurements (black solid line); the RAMS direct output (blue dotted line), and the SFSR EDR (red dashed line). In the observation, EDR was the highest within the atmospheric boundary layer, reaching approximately 0.35 m

2/3 s

−1, while the peak value from RAMS direct output was only about 0.22 m

2/3 s

−1 and even smaller from the SFSR estimation.

Apart from underestimating the peak intensity, both model-derived EDR profiles display smoother vertical variations. These characteristics mainly reflect the coarser temporal (1-min) and spatial resolution of the model output relative to the 2-s, meter-scale radiosonde measurements. The limited resolution effectively filters out short-lived or small-scale turbulent overturns, resulting in weaker and less fluctuating EDR amplitudes. Despite these differences at small scales, the modeled vertical structures agree reasonably well with the radiosonde, with correlations of 0.57 for the SFSR-derived EDR and 0.80 for the direct RAMS EDR, indicating that the dominant boundary-layer turbulence structure is broadly captured.

The two modeling approaches agree closely up to approximately 1000 m, beyond which their behaviors diverge. Above this altitude, the RAMS/Deardorff EDR reproduces a secondary maximum evident in the radiosonde profile (aside from small-scale fluctuations), whereas the SFSR-derived EDR exhibits only a weak increase, leading to a lower correlation with the observations. These results indicate that, for the direct RAMS output, a simple bias correction to address representativeness errors could mitigate the underestimation of EDR, at least in cases similar to the current one. Although one might expect that adjusting the SGS constants in the Deardorff TKE scheme would shift the EDR profile toward the observations, sensitivity experiments showed a nontrivial dependence (

Figure S1 in Supplementary Material), and the simulation with original parameter values provided the best overall match.

For SFSR, the diagnosed EDR scales inversely with the cube root of the flow-dependent parameter λ. Achieving parity with the RAMS direct output would therefore require a very large reduction in λ, suggesting that the discrepancy reflects a systematic underestimation rather than a tunable bias alone. Additional context is provided by the vertical profile of the gradient Richardson number from RAMS (

Figure 5c), which generally exceeded unity above 1000 m, indicating buoyancy-dominated flow. In the current SFSR implementation, the SGS TKE is diagnosed with strain-rate and rotation-rate tensor from the model-resolved velocity field without explicit buoyancy terms [

32]. This might explain why SFSR performs comparably to RAMS below 1000 m but underestimates EDR aloft, where buoyancy effects become important.

3.3. City-Scale Simulation

Section 3 demonstrated that RAMS generally reproduces the vertical structure of turbulence with good correlation to radiosonde measurements, apart from reduced small-scale variability. However, its resolution is insufficient to represent the intricate wind field in dense urban environments. Therefore, this section investigates the ability of a mesoscale-driven CFD simulation to reproduce urban flow patterns. Using output from RAMS as time-varying boundary forcing, the large-eddy simulation (LES) model, PALM, was employed to resolve the fine-scale features of the wind field in Tsim Sha Tsui.

The RAMS configuration utilized five nested grids with horizontal resolutions of 25 km, 5 km, 1 km, 200 m, and 40 m. For turbulence parameterization, the Smagorinsky scheme [

33] was applied to the two coarsest grids, while the Deardorff scheme [

23] was used for the remaining three finer grids. The LEAF-3 land-surface model was implemented to represent surface energy and momentum exchanges. The offline coupling between the innermost RAMS domain and PALM was achieved through a dynamic input file that provided time-varying boundary conditions for the CFD simulation. This file was generated by interpolating meteorological variables, including the three-dimensional wind components, potential temperature, and water-vapor mixing ratio, from the RAMS output onto the PALM grids.

PALM is a parallel large-eddy simulation (LES) model that solves the nonhydrostatic, filtered, and incompressible Navier–Stokes equations under the Boussinesq approximation. In the LES, energy-containing eddies are explicitly resolved, whereas SGS turbulence is represented by parameterization. A 1.5-order TKE closure, following Deardorff for the SGS fluxes and dissipation, was used in the PALM simulation [

23]. For momentum advection and time integration, a fifth-order upwind scheme [

34] and a third-order Runge–Kutta method [

35] were used, respectively. For more details on PALM, see [

36,

37,

38]. In the current study, the horizontal grid spacing was 2 m. The vertical grid spacing was 2 m near the surface, with a vertical stretching ratio of 1.08 applied above 50 m, capped at a maximum value of 12 m. Synthetic turbulence generation was also applied at the inflow [

39,

40].

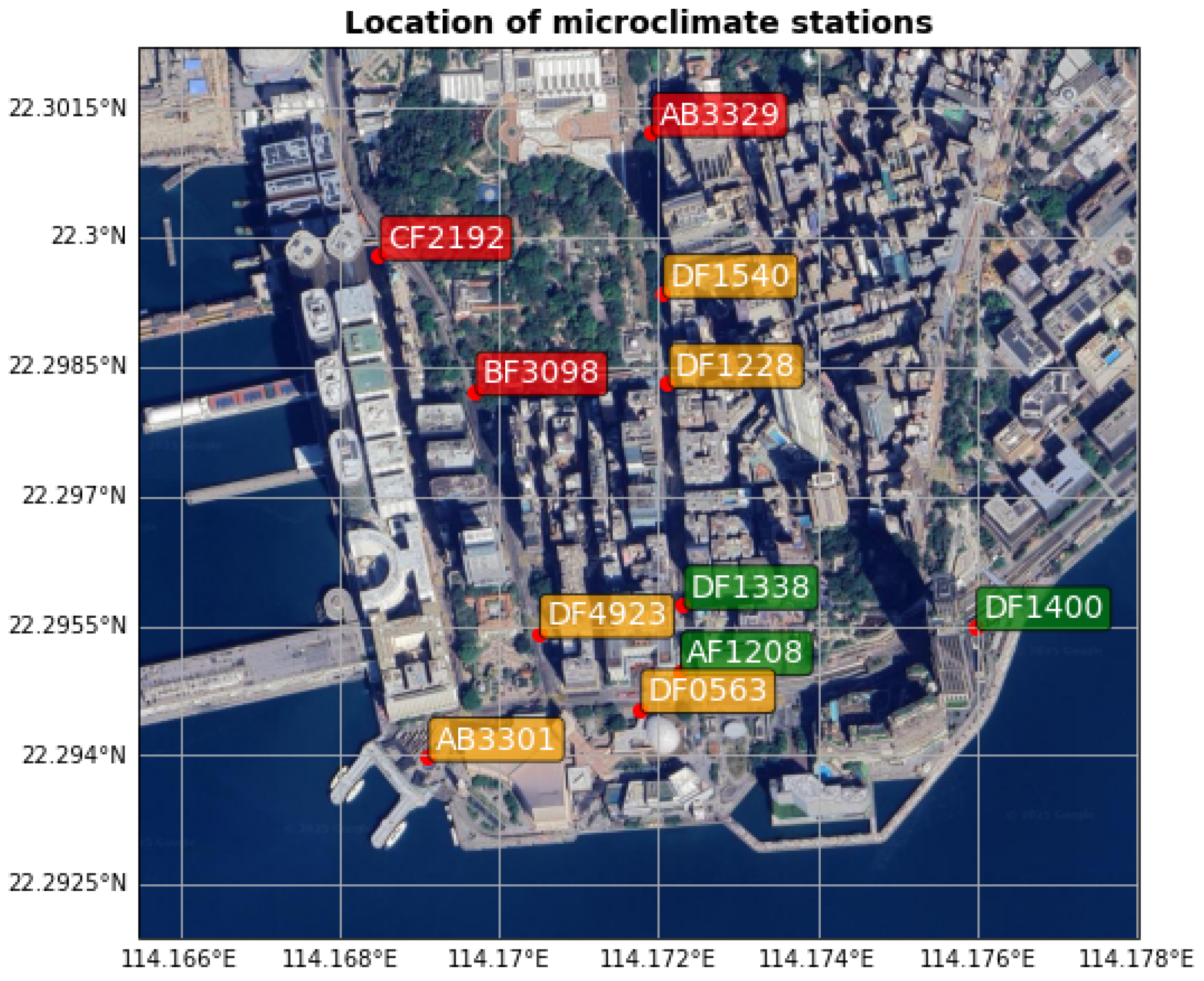

To evaluate the mesoscale–CFD coupling and its ability to reproduce local wind characteristics, we compared model output with measurements from an expanded network of microclimate stations in urban Kowloon. Whereas Lo et al. evaluated a similar approach for urban winds in Tsim Sha Tsui during Typhoon Saola using only two stations [

15], the present study utilizes eleven stations, each with two sensors at different heights. The distribution of these microclimate stations is shown in

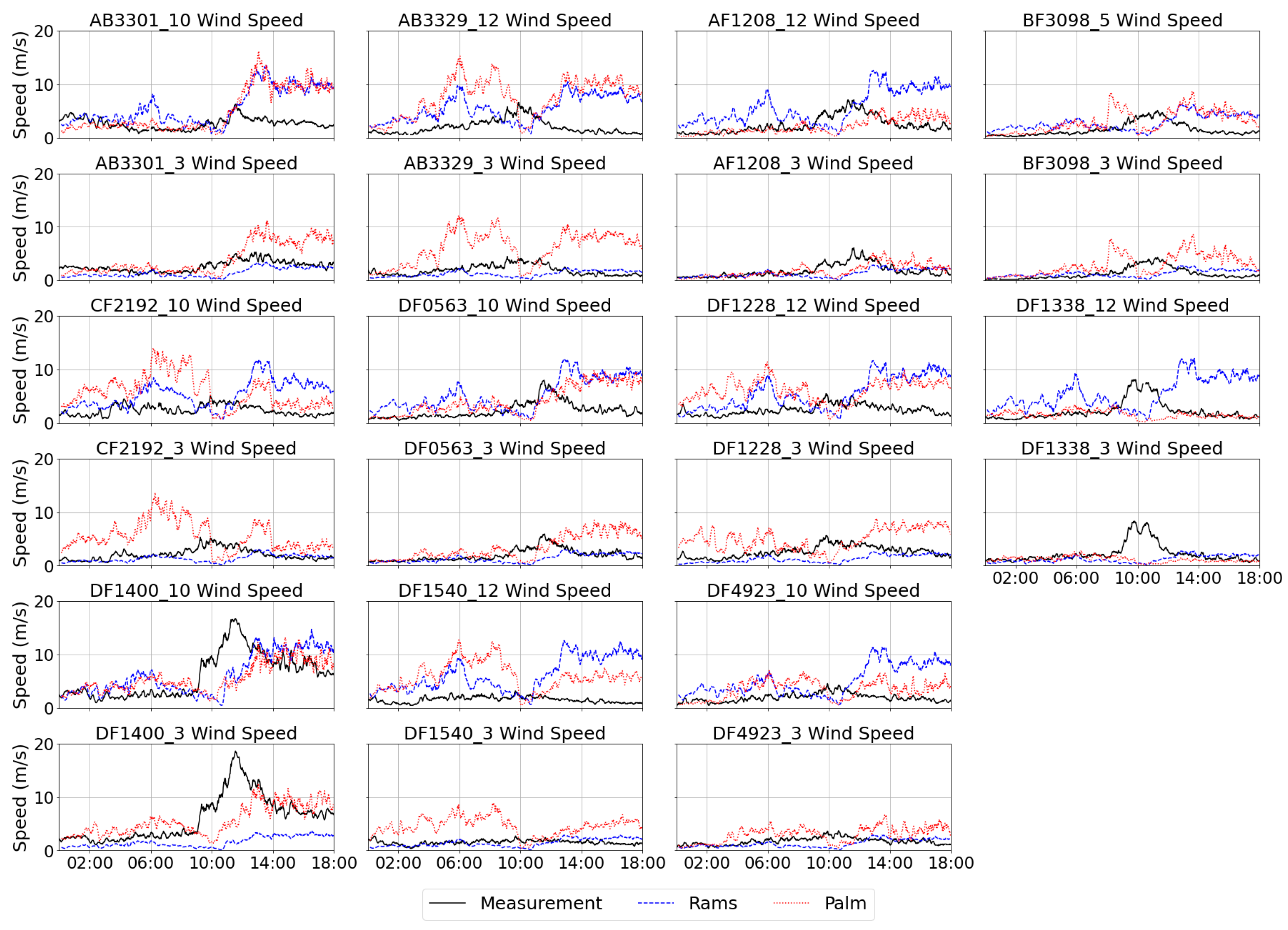

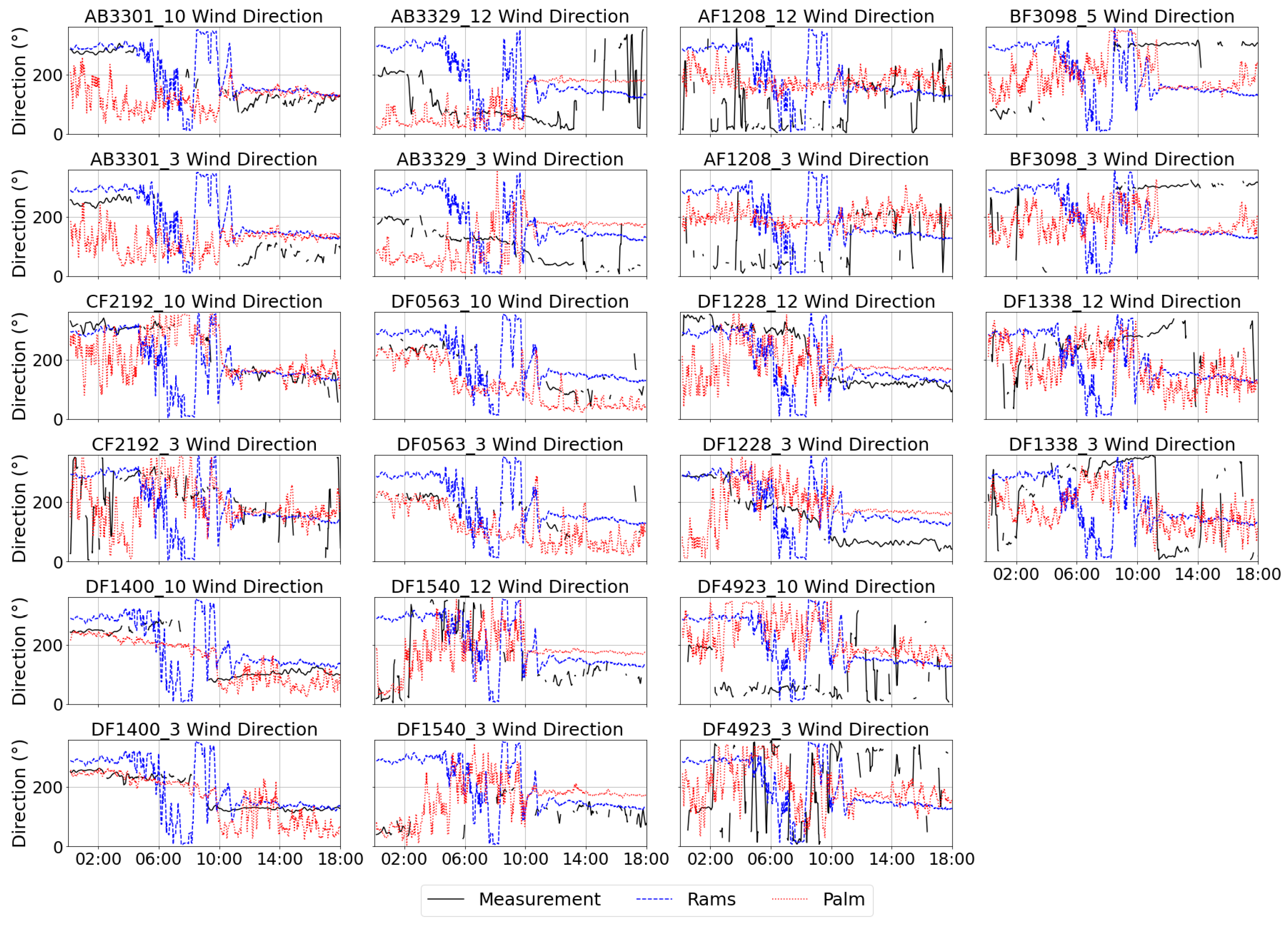

Figure 6. We analyzed the period from 00:00 to 18:00 HKT on 20 July 2025, spanning the increase in wind speed during the approach of Typhoon Wipha and the subsequent weakening after its passage.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present time series of 10-min mean wind speed and direction measured at multiple microclimate stations, compared with the simulation from RAMS and PALM. Performance was mixed across sites. At some stations, PALM reduced wind-speed errors relative to RAMS; at others, PALM exhibited substantial positive biases (e.g., AB3329 and CF2192). Root-mean-square errors (RMSEs) over the entire analysis period are summarized in

Table 1 for both RAMS alone and RAMS-driven PALM (additional metrics are provided in

Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). The RMSEs for wind speeds ranged between 1 and 5 ms

−1. The wind direction discrepancies were much larger (in the order of 60° to 140°), showing the complexity of the airflow in a highly urbanized area, especially the variability of wind direction in higher wind conditions. To assess the statistical significance of differences between PALM and RAMS, we applied a non-parametric bootstrap with 1000 resamples to obtain 95% confidence intervals and two-sided

p-values for the difference in RMSE at each measurement (

Table S2 in Supplementary Materials). Results again indicated mixed performance: nine measurements showed statistically lower RMSE for PALM, eleven for RAMS, and two showed no significant difference. To visualize these outcomes, the station labels in

Figure 6 were color-coded—green for sites where PALM outperformed RAMS at both measurement heights, red where RAMS performed better at both heights, and orange for mixed results.

Interestingly, the colored labels formed discernible clusters: the green (PALM-better) stations were mainly located in the lower-right part of the study area, closer to the waterfront and more open spaces. In contrast, the red (RAMS-better) stations were concentrated around Kowloon Park, where a large vegetation area exists. Since the PALM configuration in the current simulation did not include drag effects from plants, the absence of such resistance may have led to an overestimation of wind speeds in PALM, thereby reducing its performance in that region. The orange-labeled stations, showing mixed results, were primarily located within the most densely built-up sectors, characterized by narrow street canyons and complex building arrangements. In these areas, strong flow separations and wake interactions likely cause greater model-observation discrepancies, possibly due to boundary-forcing limitations from the coarser RAMS input or uncertainties in the building representations. Careful refinement of building representations and inclusion of vegetation canopy in future CFD simulations are expected to improve model performance in such complex urban settings. Sensitivity tests on surface roughness length indicate that the present results are relatively insensitive to plausible variations in the surface roughness length (

Figures S2 and S3 in Supplementary Materials).

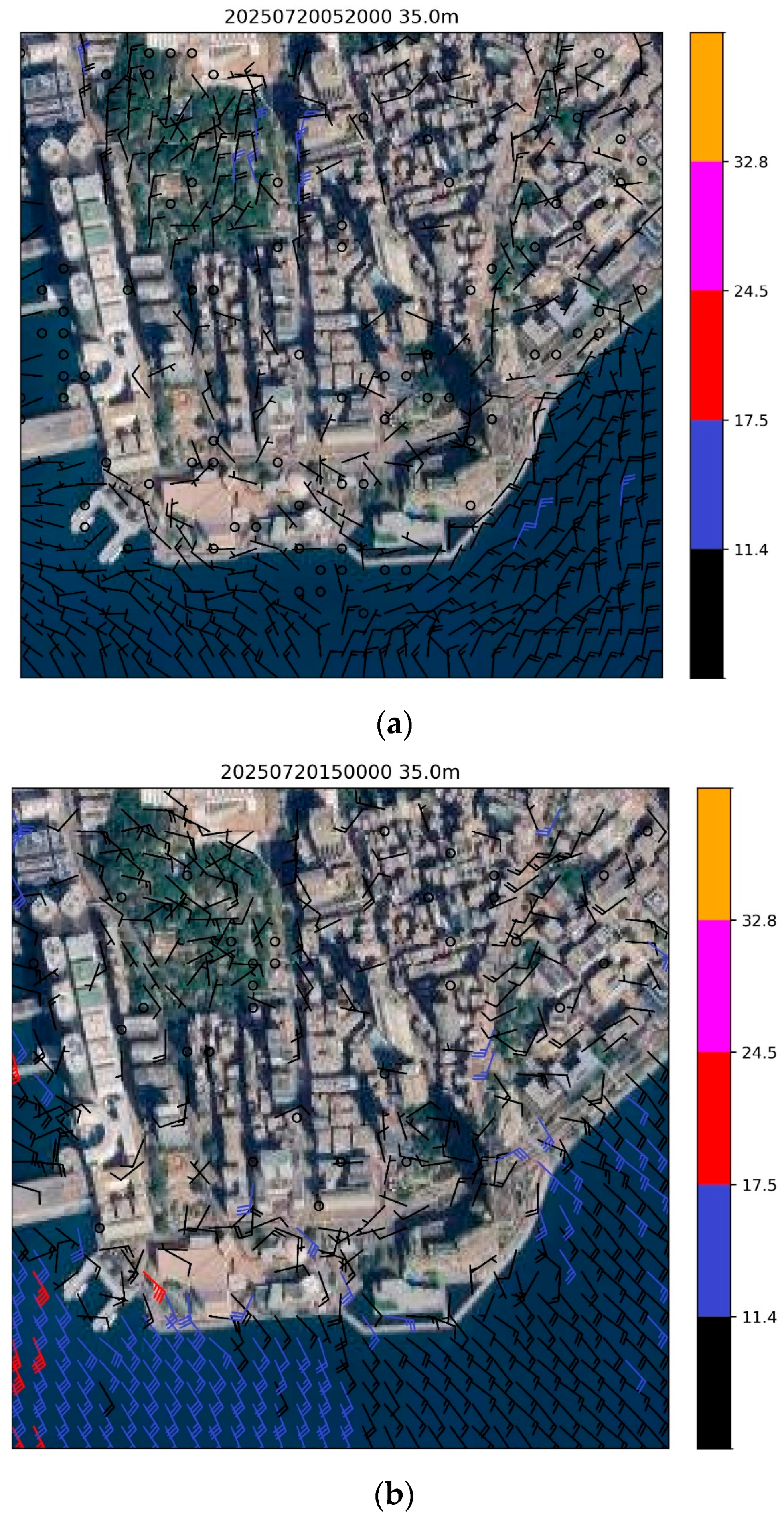

Two snapshots of simulated winds are shown in

Figure 9, representing two contrasting stages of Typhoon Wipha’s influence on Hong Kong.

Figure 9a shows the simulation at 05:20 HKT on 20 July 2025, when Wipha was centered about 150 km east-southeast of Hong Kong. At this stage, winds were generally light to moderate northerly, prior to the rapid strengthening associated with the approach of Wipha. In contrast,

Figure 9b shows the situation later the same day when Wipha skirted about 50 km south of the Hong Kong Observatory and started to depart westward. The prevailing winds had shifted to strong southeasterly winds. A height of 35 m above mean sea level was chosen. In the morning, wind speeds were generally light, with a slight northerly jet in the northern part of the modeling domain due to channeling along Nathan Road (the main north-south oriented road in the center of the domain). During the afternoon, as Wipha moved over the south of Hong Kong, the prevailing wind shifted to southeasterly, producing stronger breezes along the waterfront, particularly at Tsim Sha Tsui East (eastern part of the domain in

Figure 9b) and near the Star Ferry pier (southwestern part of the domain). The distribution of stronger winds appears to be reasonable and consistent with the conceptual anticipation of locations for the occurrence of jets under different prevailing wind directions.

3.4. Turbulence Associated with Terminal Building at the Airport

Many buildings have been constructed on the reclaimed island of the HKIA, and some of them have been found to produce turbulent flow in certain prevailing wind directions, as observed by plan position indicator (PPI) scans of the long-range LIDAR at HKIA (with a measurement range of 10–15 km) and high-resolution modeling results using RAMS coupled with PALM [

16]. However, no previous study has been conducted on building-induced turbulent flow at HKIA under southeasterly wind conditions. Typhoon Wipha provided a unique opportunity for this study.

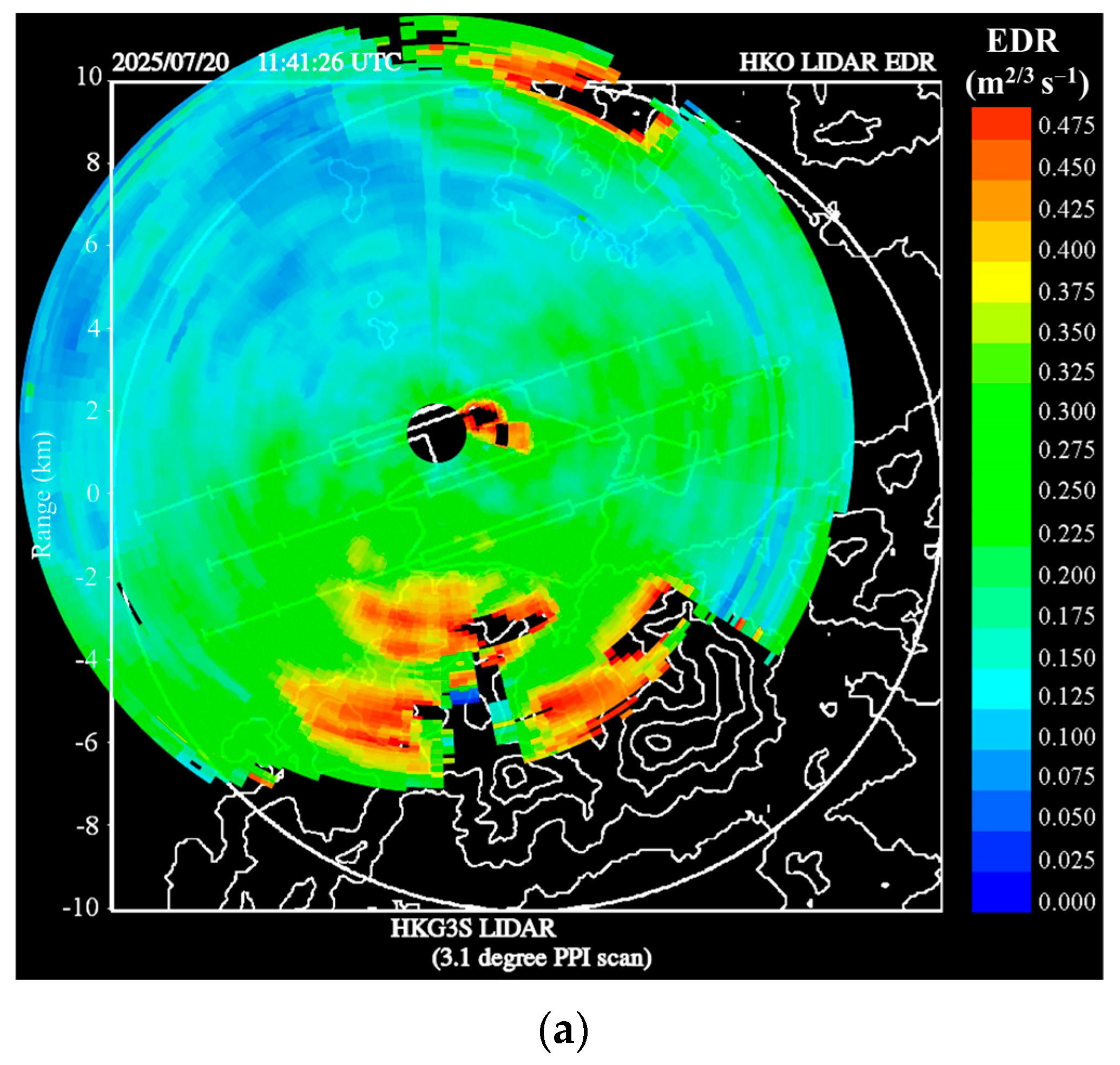

Two samples of LIDAR-based EDR maps (following the method in [

41]) are shown in

Figure 10a,b between 11 and 12 UTC (i.e., 19:00 and 20:00 HKT) on 20 July 2025. Near the location of the new terminal building (at a height of around 40 m above ground) to the southeast of the LIDAR, there was an enhanced and quasi-stationary area of higher turbulence (colored red and black, with EDR of 0.4 m

2/3 s

−1 or above), and this area of highly turbulent flow appeared to spread into the central part of the north runway of HKIA. Under southeasterly wind conditions, aircraft mostly arrive at the north runway from the west. At the location of the turbulent flow, the aircraft typically touches down and taxies; therefore, the turbulent flow area is not expected to have a significant impact. However, if the aircraft conducts a missed approach, it may hit the turbulent flow area.

A high-resolution RAMS–PALM coupled simulation was conducted for Wipha following the configuration in [

16]. The simulation domains of RAMS and PALM are shown in

Figure 11a.

Figure 11b shows a snapshot of the simulated EDR, with EDR plotted in the same conical scan area as the PPI scan of the long-range LIDAR on the northern runway in

Figure 10. It can be seen that turbulent flow was simulated successfully downstream of the new terminal building, and this turbulent flow area spread toward the central part of the north runway.

A vertical cross-section was created across the location of the turbulent flow (the location of the vertical cross-section is indicated by the cyan line in

Figure 11a), and the height-range plots of simulated EDR at three times are shown in

Figure 12a–c. Turbulence was simulated to be generated when southeasterly winds hit the building (colored red with an EDR exceeding 0.5 m

2/3 s

−1). The higher turbulence area then extended upward and drifted downwind (to the left-hand side of the figures), with the vertical extent increasing from approximately 100 m to approximately 150 m above ground. While simulation results appear to be reasonable and consistent with the anticipation of turbulent flow with southeasterly winds hitting the terminal building, there were no LIDAR observations nor other data sources available to verify the cross-section of the simulated EDRs, unfortunately.

3.5. Windshear of a Departing Aircraft

Building upon the preceding analyses of wind and turbulence structures during Typhoon Wipha, this section presents an observational case study that demonstrates their operational significance. Low-level windshear is a form of turbulent flow experienced by aircraft. At the HKIA, this is mainly related to terrain disruption of airflow. With the passage of Wipha, the southeasterly flow generally affected Hong Kong, and the terrain on Lantau Island is expected to generate near-ground turbulence. Such low-level windshear reports mostly originate from aircraft arriving at HKIA. However, in the case of Wipha, a departing aircraft reported a headwind loss of 20 knots at rotation during an eastbound departure from the south runway of HKIA at approximately 12:30 UTC on 20 July 2025. Low-level windshear reports for departing aircraft in rotation are rather rare at HKIA, especially during typhoon conditions; thus, this case was studied in detail.

Surface wind observations at that time are shown in

Figure 13a. Runway winds are generally moderate southeasterlies, with winds reaching strong forces (wind barbs colored blue) and gale forces (wind barbs colored red) on the mountains of Lantau Island (south of HKIA). The vertical wind profiles from a vertically pointing LIDAR near the center of the southern runway around that time are shown in

Figure 13b. It can be observed that low-level winds fluctuated between easterly and southeasterly winds. Wind speeds also varied with time, with winds occasionally reaching a strong force, especially at the time of the event (12:30 UTC; southeasterly winds of up to 25 knots near the surface).

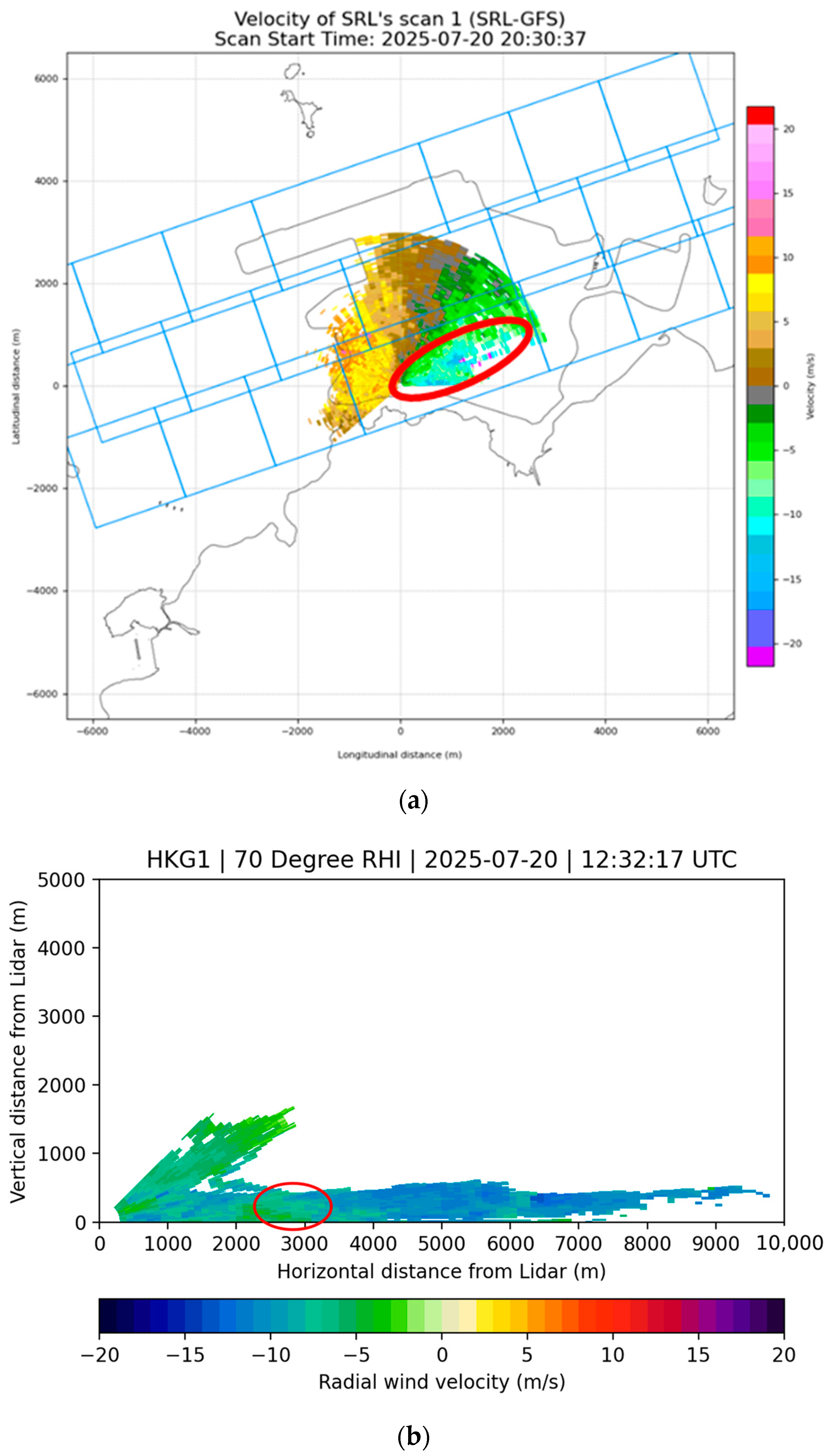

From the PPI scan of a LIDAR (

Figure 14a), turbulent flow was observed in the Doppler velocity field with a highly fluctuating Doppler wind (area highlighted in the red ellipse). From the range-height indicator (RHI) scan of a LIDAR around that time (

Figure 14b), there is an area of weaker winds (in the red ellipse) in the generally inbound flow. It appears that there was a drop in the headwind near the center of the runway, which may result in low-level windshear or headwind loss.

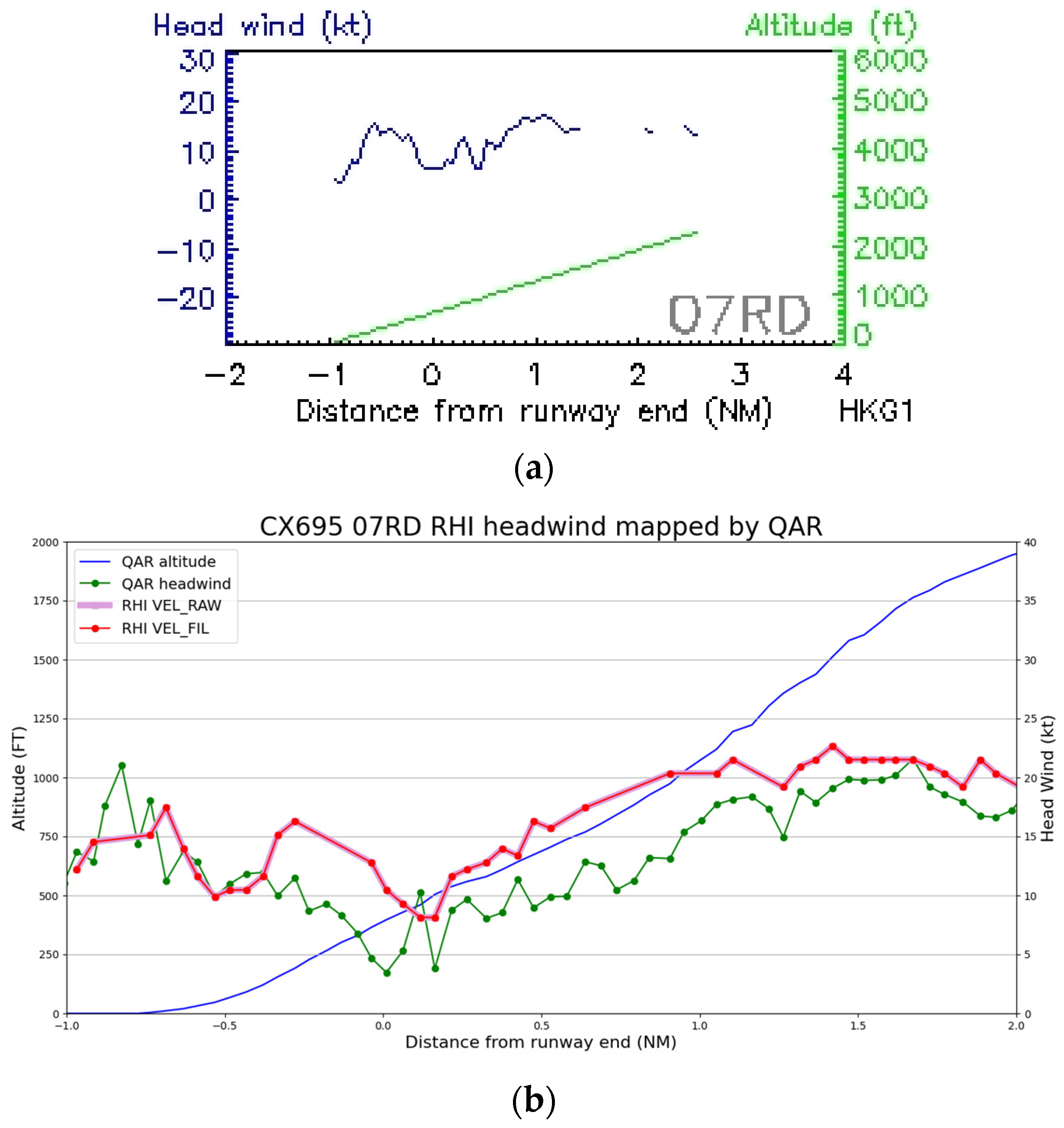

From the LIDAR-based headwind profile used operationally (

Figure 15a, assuming a 6-degree glide path originating from the center of the runway for departing flights), there was indeed a headwind loss of approximately 10 knots between the center of the runway (location −1 nautical mile from the runway end) and the runway end itself (0 nautical mile). However, the magnitude of the headwind loss was smaller than that reported by the pilot (headwind loss of 20 knots). The case was investigated further by using the actual location of the aircraft from the flight data and then extracting the LIDAR-based headwind from the RHI scan of the long-range LIDAR (

Figure 14b) so that the LIDAR-based headwind at the location of the aircraft could be used to construct the headwind profile. The results are presented in

Figure 14b. The time of the windshear encounter of the flight was at 12:30:14–32 UTC, and the RHI scan time was about 2 min after the event. The horizontal of the RHI scan plane is set to be parallel to the runway orientation, such that the magnitude of radial velocity generally corresponds to the headwind at low scan angles, and the sign would be adjusted to align with the traveling direction of the flight. Each data point from aircraft data was mapped to the closest point on the RHI plane with available data, with the condition that the angle formed by the line joining the two aforementioned points and the line joining the point on the RHI plane and the LIDAR should be within 12° of the perpendicular. This headwind profile (bold red curve) is more consistent with the measured headwind profile on the aircraft (green curve). The altitude of the aircraft is shown as a blue curve in

Figure 15b). Between −0.5 nautical miles from the runway end, to the runway end itself (0 nautical miles), the LIDAR-based headwind based on RHI scan and actual measurement from the aircraft has a magnitude (headwind loss) of around 12 knots, but such a loss appears to be “double losses”, i.e., “two bumps” of headwind changes. In contrast, the headwind profile based on flight data exhibited a “single loss” of around 16 to 17 knots (from −0.8 nautical mile to 0.0 nautical mile), close to the reported headwind loss of 20 knots. This example shows that, in actual turbulent flow, the headwind structure can be rather complex (“double losses” versus “single loss”), which is challenging for windshear alerting in an operational environment.