Abstract

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, businesses are constantly under pressure to produce high-quality, engaging content for various marketing channels, including blog posts, social media updates, and email campaigns. However, the traditional manual content generation process is often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and inconsistent in maintaining the desired messaging and tone. As a result, the content production process can become a bottleneck, delay marketing campaigns, and reduce organizational agility. Furthermore, manual content generation introduces the risk of inconsistencies in tone, style, and messaging across different platforms and pieces of content. These inconsistencies can confuse the audience and dilute the message. We propose a hybrid approach for content generation based on the integration of Markov Chains with Semantic Technology (CGMCST). Based on the probabilistic nature of Markov chains, this approach allows an automated system to predict sequences of words and phrases, thereby generating coherent and contextually accurate content. Moreover, the application of semantic technology ensures that the generated content is semantically rich and maintains a consistent tone and style. Consistency across all marketing materials strengthens the message and enhances audience engagement. Automated content generation can scale effortlessly to meet increasing demands. The algorithm obtained an entropy of 9.6896 for the stationary distribution, indicating that the model can accurately predict the next word in sequences and generate coherent, contextually appropriate content that supports the efficacy of this novel CGMCST approach. The simulation was executed for a fixed time of 10,000 cycles, considering the weights based on the top three topics. These weights are determined both by the global document index and by term. The stationary distribution of the Markov chain for the top keywords, by stationary probability, includes a stationary distribution of “people” with a 0.004398 stationary distribution.

1. Introduction

The landscape of semantics is rapidly evolving, incorporating various aspects such as semantic similarity, embeddings, hierarchies, ontologies, Markov chains, open-world semantics, semantic technologies, and semantic compression. Regarding the evaluation of semantic similarity, various models have been applied using the Quora Question Pairs dataset []. These models include a classical TF-IDF baseline, feature-engineered Random Forest and XGBoost, a Siamese Manhattan LSTM (MaLSTM), and a fine-tuned BERT model. As shown by [], each word can alter the entire meaning of the context, causing legal practitioners to often need to analyze preceding related documents for tasks such as summarization and similarity analysis.

Dvořáčková [] employs Random Forest and XGBoost to predict word similarity. The prediction was formulated using the Random Forest regression model, yielding a Pearson correlation of 0.84. Within the legal domain, word embeddings are a prominent approach. De Nicola et al. [] analyze word embeddings by creating a data corpus without any interrelation of words. Their experiment reveals the tendency of word embedding models to form apparent word relationships even when real contextual connections are absent. Furthermore, there is the work of Kraidia et al. [] with semantic similarity estimation using WordNet for tweets. They curated large-scale, high-quality datasets comprising a total of 7000 Arabic and 28,000 English tweets. In a similar vein, Formica et al. [] utilizes contexts and word senses extracted from BabelNet, comparing words as fuzzy sets according to Jaccard’s fuzzy similarity measure. In addition, ontologies are used to share knowledge, as highlighted in []. Miao et al. [] conducts an in-depth analysis of zero-shot open-vocabulary understanding, dynamic semantic expansion in an open world, and multimodal semantic fusion. Moreover, Ren et al. [] developed a system featuring two LLM-based AI agents. Their design allows the receiver to directly generate content based on coded semantic information conveyed by the transmitter. A use case on point-to-point video retrieval demonstrates the superior performance of the generative SemCom system. Improving data visualization in semantics is an open research problem, as is highlighted by []. For scalability and cost-effectiveness in Digital Twins, automation in adaptation, (re-)configuration, and generation of simulation models is crucial []. Furthermore, Listl et al. [] address gaps in semantic interoperability by applying a formal ontology to define informational requirements for incentive-based DR in commercial buildings. Mulayim et al. [] developed a formal ontology evaluation and development approach to define the informational requirements (IRs) necessary for semantic interoperability in the area of incentive-based demand response (DR) for commercial buildings. Huo et al. [] consider data in the form of point clouds, aiming to detect differences in heterogeneity structures across distinct groups of observations, motivated by a brain tumor study. Li et al. [,] alleviate issues by regularizing a Poisson–HMM, enforcing large self-transition probabilities, and naming the algorithm “sticky Poisson-HMM,” which eliminates rapid state switching. Radulescu et al. [] show that for a specific class of solvable Markov models, showing that employing a recursive method for computing symbolic solutions across any number of states using the Thomas decomposition technique is effective. Mitrophanov [] places particular attention on fundamental problems related to approximation accuracy in model reduction. These problems encompass the partial thermodynamic limit, the irreversible-reaction limit, parametric uncertainty analysis, and model reduction for linear reaction networks. Additionally, Han et al. [] investigated various properties of Markov chains related to the spectra and eigenvectors of the transition matrix. These properties include the stationary distribution, periodicity, and persistent and transient states. They demonstrate the possibility of decomposing an extensive network into several sub-networks, computing their PageRank separately, and then reassembling them. Garcia et al. [] employ a discrete-time process to model individual behavior within the system. They derive a probability function to quantify the risk of infection, taking into account the total number of individuals and their distribution across different groups. Lastly, Beck et al. [] use data compression as an end-to-end Information Bottleneck problem, aiming to enable compression while preserving relevant information. As a solution, they proposed the ML-based semantic communication system SINFONY, which they utilize for distributed multipoint scenarios.

TextRank is an effective technique; however, challenges in scalability and computational efficiency arise, particularly when working with large datasets []. The integration of LDA with HMMs often requires complex parameter tuning and is computationally intensive, restricting its effective use in systems with real-time requirements []. Despite their success, large neural language models (LLMs) are often criticized for their lack of interpretability, which poses a challenge for applications that demand transparent processing tools [], among other issues such as a high carbon footprint, data privacy concerns, and the potential for generating biased content. A comparison of key considerations, including scalability, interpretability, multilingual capability, computational efficiency, and the capability of handling large datasets, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative comparison of several different automatic text-generation methods, showcasing valuable capabilities for each method.

The research problem focuses on understanding the effectiveness of using the stationary distribution of an LSA-based Markov chain to rank the importance of latent terms within a document collection. However, the challenge lies in creating high-quality, engaging content for various domain channels using automated approaches.

Currently, LLM content generation often exhibits bias and social stereotypes. In a rapidly evolving digital landscape, writers face immense pressure to consistently produce large volumes of high-quality content. Therefore, maintaining a consistent tone, style, and messaging across different domain platforms is crucial to avoid audience confusion and brand dilution. Nonetheless, automated content generation can enhance organizational efficiency and scalability, providing a more agile response to societal demands. Consequently, integrating Markov chains with semantic technology can address challenges in automated content generation by producing coherent and contextually accurate content.

The combination of using both LSA and Markov chains provides a straightforward and interpretable model, which is crucial for tasks requiring transparency. Additionally, traditional techniques such as LSA and Markov chains demand significantly less computational power and memory compared to the complex large neural network architectures commonly utilized in modern Transformer-based architectures and large language models in general. Consequently, they are more accessible on a wider range of hardware capabilities, including limited hardware situations. Moreover, these methods are capable of dealing with smaller datasets effectively, achieving good performance without the need for extensive training data.

Moreover, it is essential to emphasize the complex relationship between AI technologies and content generation, which includes ethical, legal, and technological considerations. The research scope clearly outlines the evaluation of the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain for term ranking. To address these challenges, we propose to perform content generation by integrating Markov Chains with Semantic Technology (CGMCST) novel approach. Firstly, the probabilistic nature of Markov chains allows the automated system to predict sequences of words and phrases, thus generating coherent and contextually accurate content. Secondly, semantic technology ensures that the content is semantically rich and maintains a consistent tone and style, thereby strengthening the brand’s message and enhancing audience engagement.

The research question is:

- Q1: Does the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain reveal the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the document collection?

Our hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1.

The stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain reveals the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the document collection.

Furthermore, we aim to integrate semantic similarity estimation and contextual understanding techniques to improve the accuracy and efficiency of content generation across various domains. Our approach will leverage datasets and tailored preprocessing steps to examine the role of semantic embeddings in enhancing content coherence and maintaining messaging consistency.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 1 provides the background information. Section 2 introduces the methodology for Content Generation Through the Integration of Markov Chains and Semantic Technology (CGMCST). Section 3 discusses the experiments conducted, followed by Section 4, which presents the results obtained. Finally, we conclude the paper with a discussion in Section 5 and final remarks in Section 6.

2. Content Generation Through the Integration of Markov Chains and Semantic Technology (CGMCST)

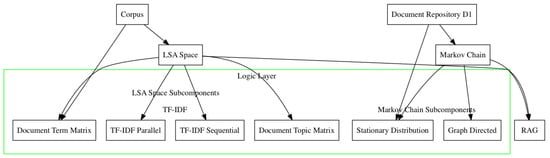

Content Generation Through the Integration of Markov Chains and Semantic Technology (CGMCST) is a method that combines the use of Markov chains and semantic technology to generate text content written in natural language. The process involves three layers, as shown in Figure 1, where each layer is tasked with handling specific aspects of content generation.

Figure 1.

System architecture with a total of three layers of the Content Generation Through the Integration of Markov Chains and Semantic Technology (CGMCST) system. Note the multiple module separation in each layer.

Figure 1 shows the overall system architecture, and an in-depth explanation of each layer is described next. In the Data Layer, relevant documents are retrieved and clustered into categories based on their respective keywords that make upthe foundational dataset for further analysis. The Logic Layer employs Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) to simplify the retrieval mechanism. LSA is used to identify documents relevant to a user’s query, effectively creating a knowledge base. LSA also allows the system to retrieve and analyze documents that contain specific keywords related to the user query. Next, the retrieved documents are processed using a Markov chain. An initial state is chosen, such as the index corresponding to Markov chains. A simulation of length n is then run to calculate the frequency of visiting each state. The simulated sequence and state frequencies are also stored for further analysis.

The stationary distribution shown in Theorem 1, obtained from the Markov chain, represents the long-term probabilities of being in each state (term) if a random surfer were to navigate infinitely through the terms based on their co-occurrence in the documents. The process reveals which terms are more central, or frequently encountered, within the text corpus.

Theorem 1.

Let be a Markov chain with a finite state space and TransitionMatrix P. If the Markov chain is irreducible and aperiodic, then there exists a unique stationary distribution such that

and

Moreover, for all .

A directed graph is then used to visually represent the Markov chain, where each state is represented as a node, and a directed edge exists from state i to state j if the transition probability is non-zero, that is, if . The edges are each labeled with their corresponding transition probabilities.

The states of the Markov chain, defined by key terms or keywords extracted from the documents, model the relationships and flow of terms within the corpus. Transition probabilities are determined based on the co-occurrence of keywords. The process involves iterating through the retrieved documents, identifying keywords, updating the transition matrix based on the ontological relationships, and then normalizing the resulting matrix. A new Markov chain instance is then created using the graph-directed transition matrix. The Markov chain is simulated using the transition matrix to calculate the visit frequency corresponding to each state. Finally, the Presentation Layer generates text starting with a specified term, aiming to produce a keyword sequence of the desired length. This sequence reflects the underlying semantic relationships and keyword frequencies derived from the Markov chain model.

The architecture of CGMCST is thus described next.

2.1. Data Layer

For each corpus, a query with the relevant documents exists, which themselves are clustered into categories, according to their own relevant keywords.

2.2. Logic Layer

This layer utilizes LSA, simplified in order to work exclusively as a retrieval mechanism, utilized to find relevant documents based on a user-defined query. These documents serve as a knowledge base, enabling the system to retrieve documents containing keywords related to the user query.

Furthermore, the retrieved documents are processed using a Markov chain. The frequency of keywords in the documents influences the transition probabilities between states representing those keywords. The steps involved are in Algorithm 1.

The stationary distribution, as shown in Theorem 1, represents the long-term probabilities of being in each state (keyword) if a random surfer were to navigate infinitely through the terms based on their co-occurrence in the provided documents. In other words, it indicates which terms are more central, or frequently encountered, in the given text corpus according to the Markov chain model.

| Algorithm 1 Process Retrieved Documents Using a Markov Chain |

|

A finite state Markov chain can be visually represented as a directed graph. Each state of the Markov chain is represented as a node in the graph, and a directed edge from state i to state j exists if the transition probability from i to j is non-zero, that is, . The edges can be labeled with the corresponding transition probabilities. The states of the Markov chain are defined by key terms or keywords extracted from the documents. The transition probabilities between these states are determined by the co-occurrence of the corresponding keywords within the retrieved documents. A higher frequency of co-occurrence between two keywords increases the probability of transitioning between the states represented by those keywords. The process is as shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Process Markov Chain with Graph-Directed TransitionMatrix |

|

Any change in the transition matrix directly impacts the simulation results and the stationary distribution. Thus the simulated random walks through the states are now constrained by the ontological relationships. That is, instead of moving freely between any co-occurring terms, the chain is guided by the predefined connections. A stationary distribution is calculated such that it reflects the structure of the graph-directed and the frequency of relevant co-occurrences within that structure. The terms that are central to the graph-directed and frequently co-occur with other related terms in the documents will likely have higher probabilities in the stationary distribution.

Using the directed graph to guide the Markov chain transitions offers valuable insights into the flow of ideas and relationships between terms within the corpus, as defined by the knowledge structure. It allows us to analyze how to navigate through the terms based on both their position in the text and their corresponding semantic relationships.

2.3. Presentation Layer

The Presentation Layer is responsible for generating text, that is, a sequence of keywords using the Markov chain transition matrix. First, select the term used as a seed in order to start the generation, and the desired length of the generated keyword sequence. Next, the algorithm maps keywords to their index in the states list and checks if the start keyword is in the states. It then retrieves the transition probabilities from the current state and verifies if the current state has any outgoing transitions. Based on these probabilities, the algorithm chooses the next state, then moves to the selected next state, and appends the next keyword to the generated sequence. This process is presented in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 Calculate Stationary Distribution of a Markov Chain |

|

3. Experiments

The dataset utilized is that proposed by Tom Mitchell [], which includes a collection of 20 newsgroups categorized into four main topics: atheism, religion, computer graphics, and medicine. The dataset in question consists of a total of 3759 documents.

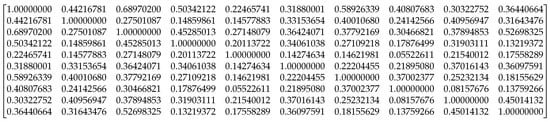

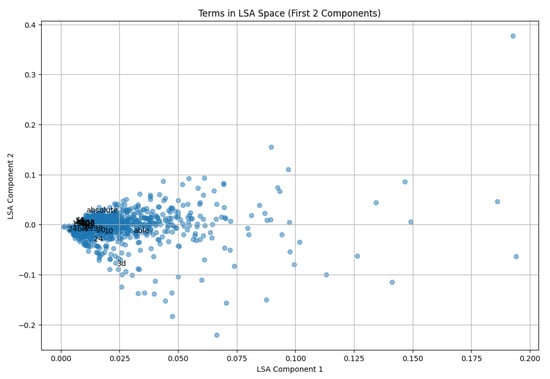

The first step is to preprocess the dataset. Each document is converted to lowercase, non-alphanumeric characters are removed, and the cleaned document is tokenized into words. Stopwords and empty strings are also removed from the entire corpus. Keywords are identified and assigned to the state variable, which forms the basis for the Markov states. The Document-Term Matrix, Document-Topic Matrix, and Term-Topic Matrix are created with the following dimensions: (3759, 1000), (3759, 100), and (1000, 100), respectively. The similarity of the terms is observed in Figure 2. Note that in order to calculate the cosine similarity between topic vectors (columns of the TermTopicMatrix), a transpose operation in the matrix is needed to directly obtain the corresponding topic vectors as rows for cosine similarity. Next, the algorithm converts the TopicSimilarityMatrix into a valid TransitionMatrix by setting the diagonal to 0 and ensuring all values are non-negative since cosine similarity can sometimes produce negative coefficients.

Figure 2.

Raw data from the CosineSimilarityMatrix. Note the expected 1 diagonal.

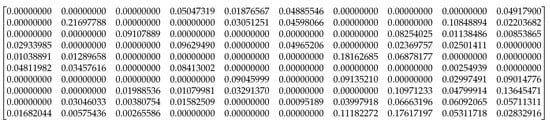

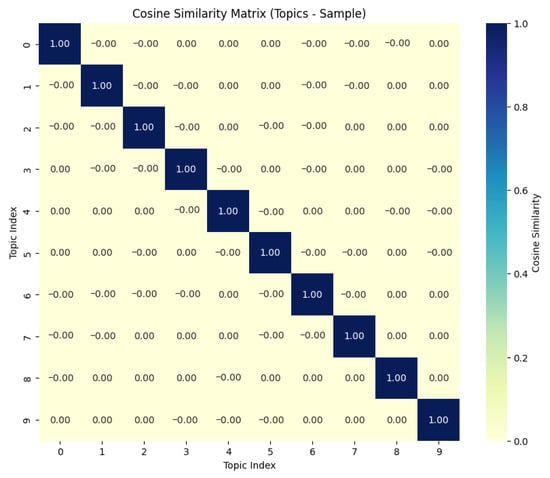

Topics with high Betweenness Centrality significantly influence the flow of transitions, as they lie on the shortest paths between other topics. As shown in Figure 3, a Markov chain TransitionMatrix based on keyword co-occurrence was successfully built and normalized. As a result, the TopicTransitionMatrix was created after 10,000 simulations.

Figure 3.

Raw data from the TopicTransitionMatrix. Note the desired 0 diagonal.

We then proceed to compute the centrality that assesses the extent to which a topic lies on the shortest paths between other topics. Topics with high Betweenness Centrality significantly influence the flow of transactions. Similar to Eigenvector Centrality analysis, this method utilizes a directed graph. According to the Perron–Frobenius theorem, if G is strongly connected, there is a unique eigenvector, and all its entries are strictly positive.

The top 10 topics by visit frequency are shown in Table 2. As we can see, Topic 63 has 128 visits, corresponding to a total visit frequency of 0.0138%.

Table 2.

Top 10 topics by visits and visit frequency.

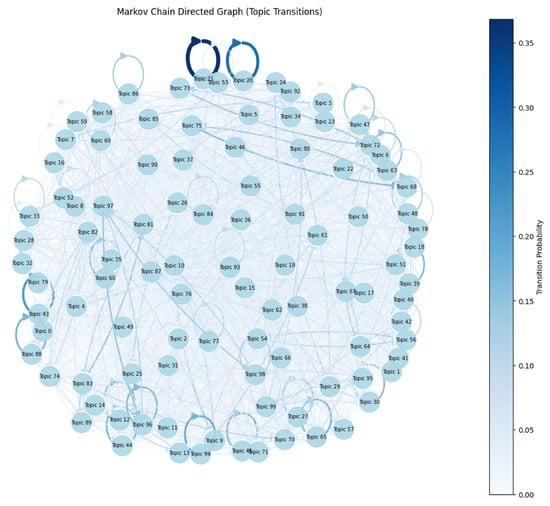

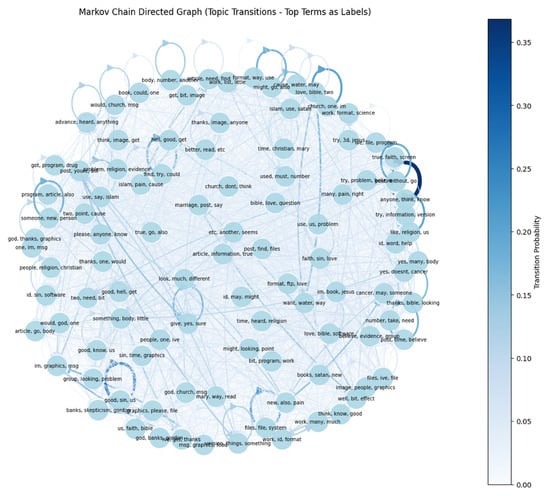

From Figure 3, the algorithm then creates a directed graph for topics. First, it measures the extent to which a topic lies on the shortest paths between other topics. Topics with high centrality have considerable influence over the flow of transitions. Then, the algorithm calculates Eigenvector Centrality, which measures the influence of a topic in a network. A topic with high Eigenvector Centrality is connected to other topics that also have high scores. This process can be computationally expensive for large graphs. In this case, for a graph size of 1000 nodes, it is manageable. The algorithm may fail if the graph structure does not meet certain criteria, such as including disconnected topics. The result is shown in the Markov Chain TransitionMatrix in Figure 4, with transition probabilities ranging from 0 to 0.35.

Figure 4.

A topic with high Eigenvector Centrality is connected to other topics that also have high scores.

Table 3 shows the variables for In-degree Centrality, Out-degree Centrality, and Degree Centrality. In-degree Centrality refers to the number of incoming edges, that is, how often a topic is transitioned to. Out-degree Centrality indicates the number of outgoing edges, i.e., how many different topics a topic transitions to. Degree Centrality is the sum of in-degree and out-degree, representing the total connections. Eigenvector Centrality measures define the influence of a topic in a network. A topic with high Eigenvector Centrality is connected to other topics that also have high scores.

Table 3.

Degree and Eigenvector Centrality for top 10 topics.

Betweenness Centrality measures the extent to which a topic lies on the shortest paths between other topics. Topics with high Betweenness Centrality have considerable influence over the flow of transitions, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Betweenness Centrality for the top 10 topics.

On the other hand, Figure 5 shows the transition probability. When this transition probability is greater than a small threshold, of , an edge is thus added.

Figure 5.

An instance with high Eigenvector Centrality is connected to other topics that also have high scores.

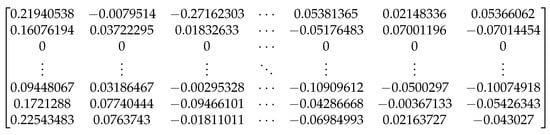

The algorithm analyzes the LSAMatrix, shown in Figure 6, to understand which are the most representative documents for each topic. For each topic (shown as columns in the matrix), it then identifies the documents with the highest values. Then, it lists the indices of the top N documents, as is shown in the LSAMatrix, that is, Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Raw data corresponding to the LSAMatrix.

The simulation was calculated for 10,000 cycles, with the weights based on three topics. These weights are determined by the document index and the term, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

The calculated weights based on top three topics, by the global document index.

Table 6.

The calculated weights based on the top three topics, by the term.

The dimensions of the Document Term Matrix are 3759 × 1000. The LSAMatrix, which is the Document Topic Matrix, has dimensions of 3759 × 100. The Term-Topic Matrix has dimensions of 1000 × 100.

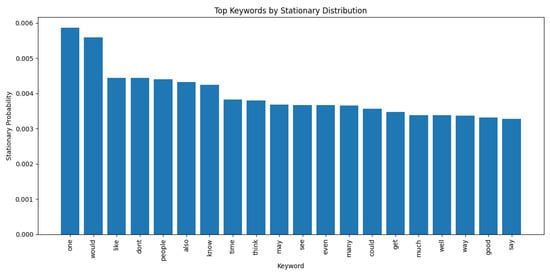

The algorithm calculates the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the TransitionMatrix. It finds the eigenvalue closest to 1. Then, the stationary distribution corresponds to the eigenvector with an eigenvalue of 1. Due to floating point inaccuracies, the algorithm looks for the eigenvalue closest to 1. The stationary distribution of the Markov chain for the top 10 keywords, by stationary probability, is shown in the Table 7.

Table 7.

The stationary distribution of the Markov chain for the top ten keywords, showing the stationary probability of each word.

Starting with the word “require”, the following text is produced: “You are required to have studied discussion comments. Good group 15 issues require community words one back go long posting. Second, people need to understand the product perfectly. Believed rather law deal give idea already given good without back. Want to know email earlier to provide the intended products. Everything is read, including persons who can’t start in user mode. Correct, generally great spiritual. Based on 20 thought matters. Prove like drugs. The community department’s death keeps the newsgroup effective. Next, apparently history indeed normal us. Points don’t interest. Hope treatment practice. Yes, won’t do the religion part, really. Become seems social head first expect a bit”. The assessment of readability, logical leaps, repetition, and stylistic drift are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Evaluation summary of text readability, logical leaps, repetition, and stylistic drift.

4. Results

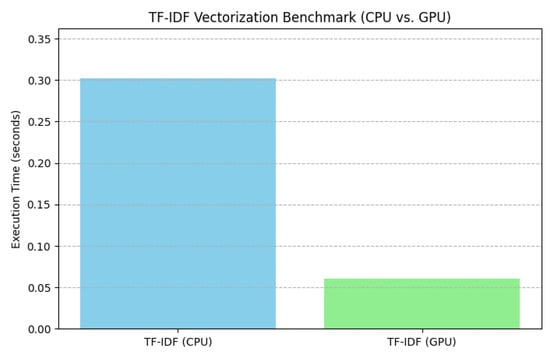

In this section, we present both the numerical analysis and the findings based on the TermTopicMatrix and other various computational metrics. The TermTopicMatrix comprises at least two components, with values ranging from zero to two, and a primary concentration at in the Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) space. The algorithm examines the topic similarity matrix, measured through cosine similarity, which indicates the relationships between topics. Furthermore, we explore the computational efficiency of TF-IDF vectorization, comparing CPU and GPU processing times. The algorithm uses an A100 GPU, which boasts 6912 CUDA cores and 432 Tensor Cores. The CPU time is recorded at s, while the GPU time is significantly lower, at s, showcasing a six-time performance improvement in the TF-IDF vectorization operation. Compare the TF-IDF task latency measured for GPU execution, measuring s, in contrast with a CPU-only execution, which was measured in s. Note that both of the CPU-only and GPU-based implementations yields identical TF-IDF results, indicating that the GPU-based implementation offers a more compelling deployment option for larger-scale and when dealing with frequent computational demands.

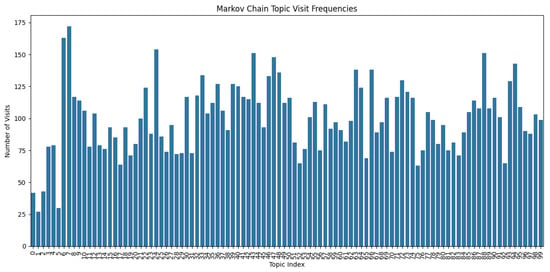

The Markov Chain Topic Visit Frequency provides insights into the frequency of topic visits, highlighting the topic indexed at 7 as the highest visit frequency among all of the 100 topics. Additionally, after achieving the stationary distribution of the Markov chain, the term “people” secures a stationary probability of . To evaluate the stability of the Generalized Conditional Markov Chain Stationary Topic (CGMCST), the algorithm calculates the entropy of the stationary distribution, resulting in a value of .

The algorithm’s entropy value was calculated using a base-2 logarithm (logarithm base 2), which resulted in an entropy of for the stationary distribution. Since the vocabulary size is approximately 1000 words, the maximum possible entropy (H) using the natural logarithm (ln) would indeed be . Therefore, it is crucial to specify that the logarithm base used here is 2 (), aligning the maximum entropy to . This corrected interpretation reinforces the model’s ability to accurately predict the next word in sequences, ensuring coherent and contextually appropriate content generation. For a more robust validation, confidence intervals and bootstrap methods were employed to estimate the entropy with greater accuracy. Additionally, the “effective number of states,” were calculated as exp(H) (where H is the entropy in natural logarithm base), which in turn provides insight into the diversity of vocabulary effectively utilized. Given an entropy (H) of approximately using base-2 logarithms, the effective number of states would be , indicating a highly dynamic and versatile content generation system. The simulation was carried out over 10,000 cycles, with weights determined by the document index and term frequencies across three topics. The stationary distribution of the Markov chain for top keywords, by stationary probability, includes a stationary distribution of “people” with a probability of 0.004398.

This high entropy value suggests a uniform distribution of visits across topics, indicating a stable and robust model in which no single topic predominates. This is a desirable characteristic in various analytical scenarios.

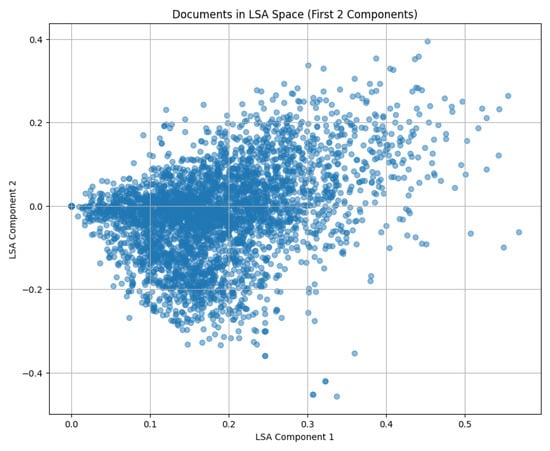

The TermTopicMatrix contains at least two components, ranging from zero to two. The concentration is at the value in the LSA space, as demonstrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The TermTopicMatrix, which contains at least two components.

The topic similarity matrix showcases the distance between topics using the cosine similarity matrix, is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Topic similarity matrix, calculated using the cosine similarity matrix.

The documents in the LSA space are shown in Figure 9, where the main concentration ranges from 0 to .

Figure 9.

The documents included in the LSA space.

The CPU execution time for TF-IDF vectorization task is s, while the execution time using a GPU is s, leading to an performance acceleration of 6 times, as is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Execution times of CPU vs. GPU, with a performance acceleration of 6 times.

The Markov Chain Topic Visit Frequency matrix helps in understanding the topics and their relationship to the number of visits, which is shown in Figure 11. The graph represents 100 topics, where the topic indexed at 7 has the highest visit frequency.

Figure 11.

Markov Chain Topic Visit Frequency. Topic 7 has the highest visit frequency.

Finally, the stationary distribution of the Markov chain is shown in Figure 12. For example, in it we can observe the term “people” has a stationary probability of .

Figure 12.

The stationary distribution of the Markov chain.

In order to assess the stability of the CGMCST, the algorithm calculates the entropy of the stationary distribution, which for this experiment resulted in . The entropy value indicates the degree of unpredictability or randomness in the stationary distribution of the Markov chain. In turn this suggests that the visits across different topics are fairly uniformly distributed, implying a stable and robust model. Having higher entropy values generally signify greater diversity and evenness in the distribution, meaning that no single topic overwhelmingly dominates, which is a desirable property in many real scenarios.

5. Discussion

As shown in Section 4, valuable insights can indeed be gained into the flow of ideas and relationships between terms within a corpus using CGMCST. Additionally, a Markov chain constructed using transition probabilities derived from the latent semantic relationships captured by LSA does reflect the thematic flow and importance of terms in the given corpus, compared to a Markov chain based solely on keyword co-occurrence. Moreover, the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain revealed the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the document collection.

To validate hypothesis 1 (H1), the stationary distribution values and entropy of the LSA-based Markov chain were examined to assess the relative importance or prominence of each latent term. For instance, the stationary probability of terms was a key factor. After achieving the stationary distribution, the term “people” had a stationary probability of . The probability indicated how prominently the term “people” was featured across all the topics in the document collection, highlighting its relative prominence.

Furthermore, performing an entropy analysis was imperative to the work. The overall entropy of the stationary distribution was measured to be . This entropy measures the unpredictability, or randomness, in the stationary distribution, with higher values indicating a more uniform distribution of visit frequencies across topics. A high entropy value, such as the one found in this experiment, suggested that the visits were fairly uniformly distributed across different topics, implying that no single topic dominated in the document collection. Having the presence of this uniform distribution indicated that all latent terms were relatively important and generally well-represented.

In summary, the data supports hypothesis 1 (H1), that the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain revealed the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the document collection. The stationary probabilities reflected the prominence of individual terms, while the high entropy value signified a balanced representation of topics, confirming that the LSA-based Markov chain effectively revealed the importance of each latent term.

We answer our research question: Q1. Does the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain reveal the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the document collection? Yes, the stationary distribution of the LSA-based Markov chain reveals the relative importance or prominence of each latent term within the corpus. After reaching the stationary distribution, the term “people” has a stationary probability of , indicating its relative prominence within the corpus. The entropy value of the stationary distribution is , which signifies a high degree of unpredictability or randomness. The visits across different topics are fairly uniformly distributed, pointing to CGMCST where the importance or prominence of each latent term is balanced and no single topic overwhelmingly dominates the document collection.

The results obtained and the performance improvement achieved when utilizing GPUs suggest that desirable future research directions include conducting additional experiments using similar methodology on a Big Data tech stack to produce both larger models and a richer, larger corpus for further validation.

6. Conclusions

The work presented validated using CGMCST and that an LSA-based Markov chain does reveal the relative importance and prominence of terms within a given corpus. By capturing latent semantic relationships, the method reflected thematic flows more accurately than just utilizing keyword co-occurrences. The stationary distribution showed the prominence of terms, such as “people,” and a high entropy value indicated a balanced representation of topics. These findings confirmed hypothesis 1.

Author Contributions

Investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review, visualization and editing: L.I.B.-S. Validation, data curation resources, and formal analysis: E.L.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors can provide the data upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to NVIDIA for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhardwaj, A.; Hasan, R.; Mahmood, S. Semantic similarity in community forum questions: Case study on Quora dataset. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikita; Rana, D.P.; Mehta, R.G.; Patel, V. Layout features and semantic similarity-based hybrid approach for thematic classification of paragraphs in documents. Knowl. Inf. Syst. Int. J. 2025, 67, 10035–10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořáčková, L. Analyzing word embeddings and their impact on semantic similarity: Through extreme simulated conditions to real dataset characteristics. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 13765–13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nicola, A.; Formica, A.; Mele, I.; Taglino, F. Information Content Methods for Semantic Similarity: An Experimental Assessment. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 113953–113966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraidia, I.; Ghenai, A.; Belhaouari, S.B. A Multi-Faceted Approach to Trending Topic Attack Detection Using Semantic Similarity and Large-Scale Datasets. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21005–21028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, A.; Mele, I.; Taglino, F. Semantic Similarity of Words in a Taxonomy: A Fuzzy and Multiple-Context Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 67149–67158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.S.; Fay, A. Utilisation of semantic technologies for the realisation of data-driven process improvements in the maintenance, repair and overhaul of aircraft components. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2024, 15, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, W.; Deng, Z. A Frontier Review of Semantic SLAM Technologies Applied to the Open World. Sensors 2025, 25, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Sun, Y.; Du, H.; Yuan, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, F.; Cui, S. Generative Semantic Communication: Architectures, Technologies, and Applications. Engineering, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti Hernes, L.; Szejka, A.L.; Mas, F. Intelligent product manufacturing cost estimation framework driven by semantic technologies and knowledge-based systems. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, G.M.; Amalfitano, D.; Russo, C.; Tommasino, C.; Rinaldi, A.M. A systematic mapping study of semantic technologies in multi-omics data integration. J. Biomed. Inform. 2025, 165, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listl, F.G.; Dittler, D.; Hildebrandt, G.; Stegmaier, V.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. Knowledge Graphs in the Digital Twin: A Systematic Literature Review About the Combination of Semantic Technologies and Simulation in Industrial Automation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 187828–187843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulayim, O.B.; Agarwal, Y.; Bergés, M.; Schaefer, S.; Shah, M.; Supple, D. Semantic Technologies in Practical Demand Response: An Informational Requirement-based Roadmap. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.01459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Zhu, H. Learning Data Heterogeneity with Dirichlet Diffusion Trees. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cao, J.; Shi, H.; Shi, X.; Ma, T.; Huang, W. Roughness prediction of asphalt pavement using FGM(1,1-sin) model optimized by swarm intelligence and Markov chain. Neural Netw. 2025, 183, 107000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Camera, G.L. A sticky Poisson Hidden Markov Model for solving the problem of over-segmentation and rapid state switching in cortical datasets. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, O.; Grigoriev, D.; Seiss, M.; Douaihy, M.; Lagha, M.; Bertr, E. Identifying Markov Chain Models from Time-to-Event Data: An Algebraic Approach. Bull. Math. Biol. 2024, 87, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrophanov, A.Y. Markov-Chain Perturbation and Approximation Bounds in Stochastic Biochemical Kinetics. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.B.; Wang, S.; Yu, C. PageRank of Gluing Networks and Corresponding Markov Chains. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Maya, B.I.; Morales-Huerta, Y.; Salgado-García, R. Disease Spread Model in Structurally Complex Spaces: An Open Markov Chain Approach. J. Comput. Biol. 2025, 32, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E.; Bockelmann, C.; Dekorsy, A. Semantic Information Recovery in Wireless Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmajac, D.; Kešelj, V. Automatic Text Summarization of News Articles in Serbian Language. In Proceedings of the 2019 18th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 20–22 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alselwi, G.; Taşcı, T. Extractive Arabic Text Summarization Using PageRank and Word Embedding. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 13115–13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACM. RecSys ’24: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. 20 Newsgroups Dataset. 1996. Available online: http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/20newsgroups/20newsgroups.data.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).