Abstract

Within the framework of the circular economy, this study evaluated the valorization of pig trotters as a source of porcine hydrolyzed collagen, which was microencapsulated via spray drying in maltodextrin (95%) and tara gum (5%) matrices. A 22 factorial design was applied to analyze the effect of inlet temperature (140 °C and 160 °C) and core concentration (5% and 10% w/w) on the physicochemical, techno-functional, structural, and morphological properties of the microcapsules. The hydrolyzed collagen presented a protein content of 52.03%. The microcapsules exhibited protein contents ranging from 17.82 to 29.36%, moisture between 1.58 and 4.71%, water activity ranging from 0.24 to 0.38, bulk density ranging from 0.44 to 0.49 g/mL, hygroscopicity ranging from 24.72 to 38.08%, solubility between 81.23 and 82.80%, and particle size ranging from 4.85 to 6.52 µm. SEM micrographs revealed predominantly spherical particles with indentations and agglomerates. FTIR spectra confirmed the characteristic amide bands of collagen and molecular interactions within the tara gum–maltodextrin matrix, while TGA thermograms demonstrated the thermal stability of the formulations. Core content had a greater influence than temperature on all response variables. Overall, the findings confirm that spray-drying microencapsulation is an effective strategy for producing stable, dispersible collagen-based powders with potential for functional food and nutraceutical applications, representing a sustainable pathway for valorizing animal by-products within the circular economy.

1. Introduction

In the context of the circular economy, the valorization of animal by-products is a key strategy for reducing waste, minimizing environmental impacts, and transforming residues into high-value, functional ingredients for the food and nutraceutical industries [,,,,,,]. The meat industry generates large volumes of by-products, including skin, bones, tendons, viscera, and extremities, whose inadequate management increases the sector’s environmental footprint. These materials are rich sources of collagen and proteins with technological potential, provided that appropriate extraction and stabilization processes are applied [,,]. Among porcine by-products, edible tissues with a high content of connective tissue, such as pig trotters, remain underutilized despite their nutritional and functional value. Their valorization provides a low-cost collagen source with potential for higher value-added formulations []. In particular, pig trotters have received little attention compared to porcine skin or bones, making this study a novel contribution. This trend aligns with growing evidence supporting the comprehensive utilization of animal by-products through bioprocesses and encapsulation technologies, enhancing sustainability, resource-use efficiency, and the production of functional ingredients with traceability and consumer acceptance [,,].

Collagen derived from animal tissues, such as skin, bones, and tendons, is obtained through hydrolysis processes that can be acidic, alkaline, or enzymatic, with the latter being the most widely used to produce hydrolyzed collagen with a low molecular weight and high bioavailability [,,,,]. Its composition, rich in glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, favors its incorporation into functional foods and nutraceutical products [,]. It is currently used in protein supplements, functional beverages, fortified dairy products, and formulations targeting joint and skin health, as well as in diets that require easily digestible and rapidly absorbed proteins [,,]. However, its use is limited by factors such as sensitivity to temperature, humidity, and light exposure, which can affect its stability and reduce its bioactivity during storage and processing [,,,]. These constraints have driven the development of technologies such as encapsulation to protect and enhance their functional properties.

Encapsulation by spray drying is recognized as one of the most effective techniques for protecting bioactive compounds, including high-value proteins and peptides such as collagen, enabling the production of microcapsules with high encapsulation efficiency, controlled morphology, and good solubility [,,,,,]. The choice of wall materials, such as maltodextrin and tara gum, along with the control of operating parameters, including inlet temperature and core-to-matrix ratio, significantly influences the stability and final properties of the product [,,,,,,]. While maltodextrin is a widely recognized carrier, the inclusion of tara gum, a natural hydrocolloid of Peruvian origin scarcely reported in spray-drying applications, provides novelty to this work. It offers unique functional and rheological properties that may enhance microcapsule stability [,]. Furthermore, advances in nano-spray drying offer smaller microcapsules with a greater surface area, thereby benefiting controlled release and bioavailability; however, conventional spray drying remains more viable at the industrial level [,]. Taken together, these aspects highlight a clear research gap regarding the limited exploration of pig trotters as a collagen source and the underuse of tara gum in spray-drying systems, which this study addresses explicitly.

This study hypothesizes that porcine hydrolyzed collagen, microencapsulated by spray drying in maltodextrin and tara gum matrices, will retain stable physicochemical and functional properties, as well as suitable morphological and techno-functional characteristics for use in food and nutraceutical applications. The primary objective of this study was to develop and characterize hydrolyzed collagen microcapsules obtained from pig trotters, using a factorial design to evaluate the effects of inlet temperature and core-to-matrix ratio on their physicochemical, morphological, and techno-functional properties. By addressing this research gap, the study aims to propose a technological and sustainable alternative for the valorization of animal by-products, in line with the principles of the circular economy and current trends in the development of high-value, functional ingredients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Porcine trotters, obtained as slaughter by-products, were sourced from the municipal slaughterhouse of Andahuaylas (Apurímac, Peru), which is registered with the National Agrarian Health Service (SENASA). Selection was carried out through controlled sampling, ensuring that the samples were free of signs of disease. Commercial organic tara gum (Molinos Asociados, Lima, Peru), maltodextrin (Regon, Lima, Peru), sodium hydroxide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 96° ethanol (Coderal, Lima, Peru), pancreatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and isopropyl alcohol (Martell, Lima, Peru) were also used.

2.2. Extraction of Porcine Hydrolyzed Collagen

Hydrolyzed collagen was obtained following the general methodology described by Benítez et al. [], with modifications. Porcine trotters were weighed and washed with potable water to remove visible residues, followed by manual cleaning to remove fat, bone, hair, and skin remnants. The initial extraction was carried out by pressure cooking at 86 °C for 3.5 h to facilitate collagen solubilization. The extract was filtered through gauze and cooled to room temperature to induce gelation and allow the separation of surface fat. For enzymatic hydrolysis, the pH was adjusted to 7.9–8.0 with 1 N NaOH using a potentiometer (Lab 885 SI Analytics, Mainz, Germany) and a thermostatic magnetic stirrer (M6 CAT, Ballrechten-Dottingen, Germany). Pancreatin (10 mg) was added, and the mixture was maintained at 37 °C for 24 h under constant agitation in a water bath with an agitation system (WTB50 Memmert, Schwabach, Germany). The resulting hydrolysate was dried in a forced convection oven (FED 115 Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 60 °C until a dry powder was obtained, which was hermetically packaged in polyethylene containers for storage.

2.3. Microencapsulation by Spray Drying

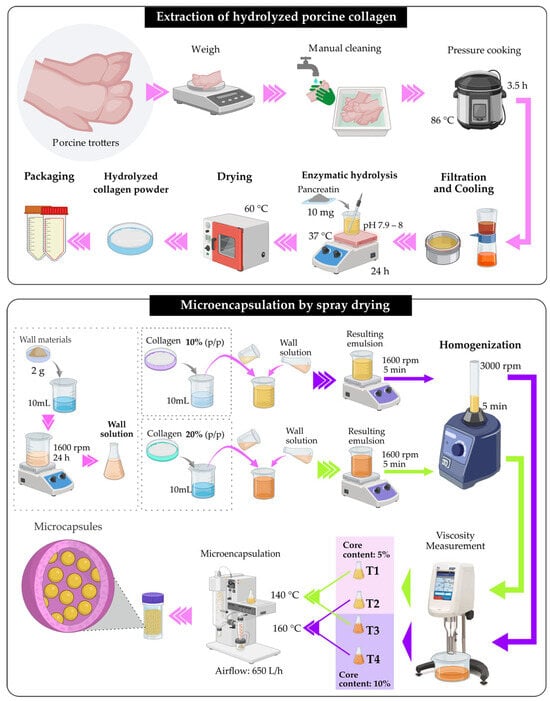

The wall solution was prepared by weighing 2 g of encapsulating agents composed of maltodextrin (95%) and tara gum (5%), dissolved in 10 mL of ultrapure water. In parallel, solutions of porcine hydrolyzed collagen at 10% and 20% (w/w) were formulated in 10 mL of ultrapure water. The encapsulant mixture was stirred at 1600 rpm for 24 h and subsequently combined with the collagen solution at the same speed for 5 min. The resulting solution was homogenized in a vortex at 3000 rpm for 5 min. This final solution constituted the feed supplied to the spray dryer. The viscosity of each formulation was measured to verify its compatibility with the spray-drying process, and it was adjusted to 30 cP using a rotational viscometer (Brookfield DV-E, Stoughton, MA, USA), using spindle No. 61. Microencapsulation was carried out in a Mini Spray Dryer B-290 (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) at inlet temperatures of 140 and 160 °C, using core concentrations of 5% and 10% (w/w), which were selected based on preliminary tests showing that higher core levels markedly increased the viscosity of the mixture and hindered the spray-drying process, an air flow rate of 650 L/h, and a 0.7 mm nozzle. The resulting powders were packaged in hermetically sealed polypropylene tubes and stored in a desiccator at room temperature until analysis. The total solids content of the feed mixture, considering both the wall materials and the core, was 13% and 18% (w/w), corresponding to the formulations with 5% and 10% (w/w) core, respectively [,]. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram for the microencapsulation process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the microencapsulation process.

2.4. Protein Determination

The protein content in the porcine hydrolyzed collagen and the microcapsules was determined using the official AOAC 2003.05 method (AOAC, 2012) [], based on Kjeldahl digestion, by quantifying total nitrogen and multiplying by the conversion factor 6.25.

2.5. Moisture Content Determination

Moisture content was evaluated following the official AOAC 925.10 method (AOAC, 2012) [], by drying in an oven at 105 ± 1 °C until constant weight. Determinations were performed in a forced convection oven (FED 115, Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany).

2.6. Water Activity (aw) Determination

Water activity was determined using a portable HygroPalm23-AW meter (Rotronic, Bassersdorf, Switzerland), previously calibrated according to the manufacturer’s specifications. A 5 g sample was placed in a disposable container, the probe was inserted, and the reading was recorded at 25 ± 1 °C [,].

2.7. Bulk Density Determination

A known portion of the dry sample, without compaction, was placed in a 10.0 mL graduated cylinder, and the occupied volume was recorded. The mass was then determined using an analytical balance. Bulk density was calculated by dividing the sample mass by the recorded volume and expressed in g/mL [].

2.8. Hygroscopicity Determination

0.2 g of the sample was weighed and placed in a hermetically sealed container containing a saturated NaCl solution, maintained at 20 ± 1 °C under controlled conditions for 7 days. At the end of this period, the final mass was recorded. Hygroscopicity was calculated using the following formula:

where is the increase in mass in percentage (%), is the mass of the empty Petri dish, is the mass of the Petri dish with the sample at the beginning, and is the mass of the Petri dish with the sample after seven days [].

2.9. Solubility Determination

A total of 2.5 g of microcapsules was weighed and dissolved in 250 mL of distilled water. The mixture was stirred for 5 min until a homogeneous dispersion was obtained, after which it was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min to separate the supernatant. Subsequently, aliquots of the supernatant were taken and dried in an oven at 105 °C for 5 h. Solubility was calculated using the following formula.

where is the solubility in percentage (%), is the initial mass of the microcapsules, and is the final mass after drying [].

2.10. Particle Size Determination

Particle size was determined by laser diffraction using a Mastersizer 3000 instrument (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) equipped with a 600 nm helium–neon (He–Ne) light source. A representative amount of microcapsules was dispersed in isopropanol and subjected to sonication for 60 s until the optimal obscuration level of the detector was reached [].

2.11. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

The morphology of the microcapsules was evaluated by SEM using a Prisma E microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic). Samples were mounted on aluminum stubs using 12 mm diameter carbon adhesive tape. Observations were carried out under low-vacuum conditions, using the ABS detector at a pressure of 0.07 Torr [].

2.12. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

The functional groups of tara gum, maltodextrin, collagen, and microcapsules were determined using a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer, Nicolet IS50 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA), using the transmission module between 400 and 4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 8 cm−1, 32 scans, and using 0.1% KBr pellets [].

2.13. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

A thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a TGA 550 instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Ten milligrams of the sample were used and heated from room temperature to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

The studied properties were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with a significance level of 5% and three replicates per treatment. The microencapsulation study was conducted under a 22 factorial design, considering two inlet temperatures (140 °C and 160 °C) and two core concentrations (5% and 10% w/w). The best treatment was selected by applying the desirability function to the four experimental points of the design, identifying the one with the highest overall desirability. Statistical analysis was performed using STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVI, version 16.1.03 (StatPoint Technologies, Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA). Pearson correlation and principal component analysis (PCA) plots were generated with OriginPro 2023 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). The assumptions of ANOVA were verified before applying Tukey’s test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wall Materials Morphology, Particle Size, FTIR, and TGA Analyses

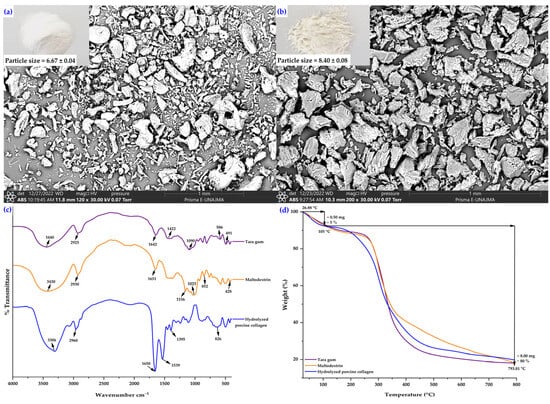

Figure 2a shows that maltodextrin had smaller, irregular, fragmented particles with rough surfaces and a marked tendency to agglomerate, highlighting its amorphous nature and its ability to form highly soluble wall matrices in the spray drying process []. On the other hand, tara gum (Figure 2b) showed larger particles with denser, more compact, and heterogeneous structures, evidencing a polymer network capable of retaining water and conferring greater viscosity to the encapsulating solutions [,]. Maltodextrin promotes rapid film formation during spray drying, while tara gum provides viscosity, emulsifying capacity, and stabilizing properties, which improve the surface integrity and functionality of collagen microcapsules []. Therefore, the formulation used in microencapsulation was 95% maltodextrin and 5% tara gum, as this proportion of hydrocolloid is sufficient to enhance the stability of the system and complement the properties of maltodextrin. These characteristics support the combination of both biopolymers as sustainable wall materials, reinforcing the relevance of their use in the design of polymer composites within the framework of the circular economy.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) and particle size of wall materials: (a) maltodextrin, (b) tara gum, (c) FTIR spectra, and (d) TGA thermograms.

In the case of tara gum (Figure 2c), a band is observed at 3440 cm−1, corresponding to the O–H stretching characteristic of polysaccharides consisting of mannose and galactose. The band at 2925 cm−1 is associated with the C–H stretching of aliphatic groups. The signal at 1642 cm−1 is mainly attributed to the H–O–H bending of absorbed water and, to a lesser extent, to the C=O stretching of possible acetyl groups. The band at 1422 cm−1 corresponds to the deformation of the CH2/CH3 groups of the polysaccharide skeleton. The peak at 1090 cm−1 is related to the C–O–C vibrations of the glycosidic bond typical of polysaccharides. Finally, the bands between 491 cm−1 and 586 cm−1 are assigned to the skeletal vibrations of the pyranose ring [,,,].

In the case of maltodextrin (Figure 2c), a broad band is observed at 3430 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching of the hydroxyl group (O–H), characteristic of polysaccharides with hydrogen bonds. The band at 2930 cm−1 is associated with the C–H stretching of aliphatic groups. The signal at 1651 cm−1 is due to the H–O–H bending of absorbed water. The bands at 1156 cm−1 and 1023 cm−1 correspond to the C–O–C and C–O stretching of the glycosidic bonds in the partially hydrolyzed starch structure. Finally, the signals at 852 cm−1 and 428 cm−1 are attributed to the vibrations of the pyranose ring present in the glucose unit of maltodextrin [,].

In the case of porcine collagen (Figure 2c), a broad band is observed at 3306 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching of the N–H and O–H groups, characteristic of proteins with abundant hydrogen bonds. The band at 2960 cm−1 is associated with the C–H stretching of the aliphatic chains present in amino acids. The intense signal at 1650 cm−1 corresponds to the Amide I band, attributed to the C=O stretching of the peptide bond, while the band at 1539 cm−1 is assigned to the Amide II band, related to N–H deformation and C–N stretching. The band observed at 1395 cm−1 is due to the vibration of the C–H groups of the side chains. Finally, the signal at 826 cm−1 is attributed to the vibrations of the peptide backbone, associated with the helical structure of collagen [,].

Figure 3d, corresponding to thermogravimetric analysis, shows an initial weight loss of approximately 5% at 105 °C, attributed to the removal of moisture adsorbed in the tara gum, maltodextrin, and hydrolyzed porcine collagen samples. Subsequently, continuous thermal degradation is observed between 200 °C and 400 °C, associated with the breakdown of glycosidic bonds in tara gum and maltodextrin, as well as peptide bonds in hydrolyzed porcine collagen. At temperatures close to 800 °C, the three samples retain approximately 20% residue, indicating adequate thermal stability and the formation of carbonaceous residues typical of natural biopolymers [,,].

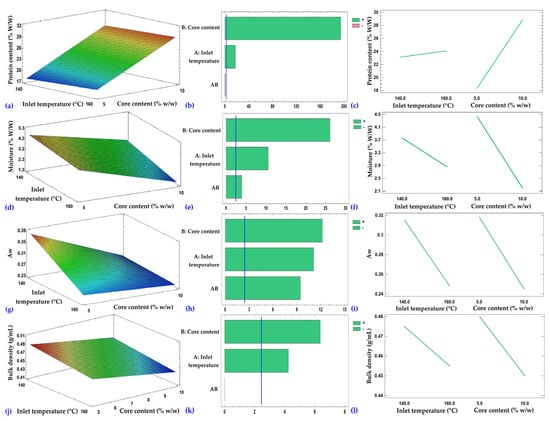

Figure 3.

Response surfaces (a,d,g,j), Pareto charts (b,e,h,k), and main effects plots (c,f,i,l) corresponding to the protein content, moisture, water activity (aw), and bulk density of the microcapsules, respectively.

3.2. Microencapsulation by Spray Drying

The protein content in the porcine hydrolyzed collagen was 52.03% ± 0.65, a value comparable to that reported for tilapia skin collagen (54.14%) [] and slightly lower than that obtained from pig skin (57.9%) []. In comparison, higher values (80.70%) have been reported for hydrolyzed collagen obtained from bovine tendons using pancreatin enzyme hydrolysis []. These differences are associated with the hydrolysis conditions and, notably, with the extraction pH; indeed, it has been reported that collagen hydration is low between pH 6–8 and increases at extreme values, influencing extraction and protein yield []. Table 1 presents the physicochemical and techno-functional properties obtained using a 22 factorial design.

Table 1.

Physicochemical and techno-functional properties of the microcapsules.

The protein content in the microcapsules ranged from 17.82% to 29.36%, evidencing the influence of the evaluated factors. Moisture content varied between 1.58% and 4.71%, while water activity remained in the range of 0.24 to 0.38. Both parameters were low, suggesting good product stability. Bulk density showed similar values among treatments (0.45–0.46 g/mL). Hygroscopicity ranged from 24.72% to 38.08%, with higher values observed in formulations with greater protein content. Solubility was high in all treatments (81.23–82.80%), indicating good dispersibility in aqueous systems. Particle size ranged from 4.85 μm to 6.52 μm, with significant differences between treatments, which could influence rehydration and dissolution behavior.

The response surface of protein content (Figure 3a) showed an increase with a higher core percentage, remaining relatively stable with variations in inlet temperature. Core content was the most influential factor (p ≤ 0.05), while temperature exerted a less pronounced positive effect (Figure 3b,c). The protein content of the microcapsules exceeded that reported for hydrolyzed collagen encapsulated in maltodextrin by Palamutoğlu and Sarıçoban (18.42–22.56%), who also noted that such content depends on the peptide dose used in the formulation, in agreement with the positive effect observed for core content []. Likewise, Kurozawa et al. reported that spray-drying a chicken protein hydrolysate formulated with high levels of carrier agents (maltodextrin and/or gum arabic) resulted in powders containing 7.05% protein, lower than the values found in this study, attributed to the dilution caused by the wall materials []. The selection of the encapsulating agent and the spray-drying conditions significantly influence the retention of bioactive peptides and the structural stability of the microcapsules during storage, as reported in the literature []. Taken together, these variations reflect the combined effect of the core ratio, the final moisture content of the powder, and the matrix-like structure generated by spray drying, which promotes collagen retention and explains the higher protein content in treatments with lower residual moisture.

Regarding moisture (Figure 3d), a progressive decrease was observed with increasing temperature and core percentage. Core content was the main factor (p ≤ 0.05), followed by temperature and, to a lesser extent, their interaction (Figure 3e,f). Moisture values were similar to those reported for casein hydrolysate microcapsules obtained by spray drying with maltodextrin (3.27% and 3.60%) []. They were also lower than those obtained for hydrolyzed collagen from fish scales encapsulated with maltodextrin (6.19–6.35%) []. In another study on the influence of spray-drying conditions on the physicochemical properties of chicken meat powder, moisture values between 2.48% and 8.57% were reported, noting that lower moisture content can be achieved when higher levels of solids are used in the feed, due to the increased solid concentration in solution and reduced free water available for evaporation []. The lower moisture observed in this study could be attributed to the combined use of maltodextrin and tara gum as wall materials, which may favor reduced water retention in the encapsulated matrix. This parameter is critical for the preservation of dry products, as it directly influences their physicochemical and microbiological stability during storage. The literature recommends keeping moisture content below 5%, a criterion met in this study (corresponding to actual values in the 0–4.9% range) [,,].

Water activity (Figure 3g) showed a pattern similar to that of moisture, decreasing with higher core content and temperature. Core content had the most significant effect, followed by temperature; the AB interaction had a minor influence (Figure 3h,i). In this study, the water activity of the microcapsules was within the range reported for guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) blood erythrocyte microcapsules (0.35–0.40) []. This behavior is associated with the nature of the encapsulated material, the formulation, and the drying conditions. The decrease in aw with increasing inlet temperature and core content, consistent with the trend observed for moisture, indicates a more efficient removal of free water. High aw values promote biological and chemical deterioration reactions, such as enzymatic and non-enzymatic browning. Therefore, for spray-dried products, some authors recommend maintaining a water activity below 0.6 as a practical criterion for microbiological stability, which was achieved in the present study [,]. However, several authors have pointed out that to ensure long-term physicochemical stability in spray-dried powders, an aw value below 0.20 is required, a threshold that was not reached in this study [,], with recommended values falling within the 0–0.19 range for long-term stability. In summary, the microbiological stability of powders is mainly due to their low moisture and water activity values, which reduce the free water available for microbial growth. In addition, the particles’ compact morphology limits surface moisture retention, further enhancing the stability achieved.

As for bulk density (Figure 3j), it decreased as core content and temperature increased. Core content was the main factor of variation, followed by temperature (Figure 3k,l). The bulk density values obtained in this study fall within the range reported for microencapsulated systems. In a study on guinea pig blood erythrocyte microencapsulation, values between 0.10 and 0.50 g/mL were reported []. Similarly, in a study on the influence of spray-drying conditions on the physicochemical properties of chicken meat powder, values between 0.31 and 0.44 g/mL were observed []. In the latter study, it was noted that higher bulk density is related to moisture content and product stickiness; with higher moisture, more particles tend to agglomerate, increasing volume and, consequently, bulk density [].

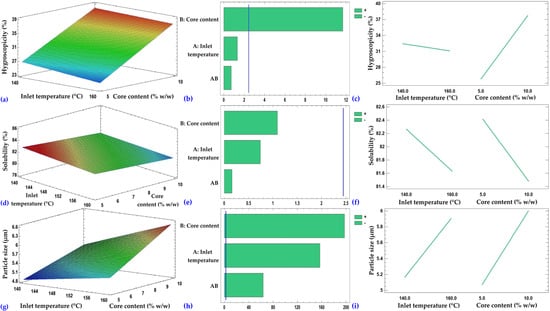

The response surface of hygroscopicity (Figure 4a) showed an increase with higher core percentage and a slight decrease with inlet temperature. Core content was the most influential factor (p ≤ 0.05), followed by temperature (Figure 4b,c). The hygroscopicity obtained in the present study was higher than that reported for the microencapsulation of fish collagen hydrolysates in maltodextrin (9.86–10.73%) [], a difference attributable to the nature of the encapsulated material, as hydrolyzed porcine collagen contains low-molecular-weight peptides with a greater affinity for water. On the other hand, the results are within the range reported for the microencapsulation of guinea pig blood erythrocytes (22.05–32.94%) [] and below the values obtained in casein hydrolysates (≈53%) []. Similarly, values between 13.11% and 26.68% were reported in chicken meat powders produced by spray drying, highlighting that the incorporation of maltodextrin, due to its high molecular weight, improves the stability of the powders by reducing hygroscopicity and stickiness []. In general, the values obtained in this study were above the critical value of 20%, considered optimal for the storage and handling of dehydrated products [,].

Figure 4.

Response surfaces (a,d,g), Pareto charts (b,e,h), and main effects plots (c,f,i) corresponding to the hygroscopicity, solubility, and particle size of the microcapsules, respectively.

In the case of solubility (Figure 4d), a slight decrease was observed with increasing core percentage and inlet temperature. Neither the factors nor their interaction had a significant effect (p > 0.05) on this property (Figure 4,f). The solubility values obtained for the microcapsules were higher than those reported for guinea pig erythrocyte microcapsules (43.22–57.18%) and close to the value for unencapsulated erythrocytes (72.08%), indicating good dispersibility in aqueous media and suggesting that the applied formulation and process favored the rehydration and dissolution of the core []. Solubility is a key property in food products and, in the case of encapsulates, is influenced by spray-drying conditions, such as inlet temperature, as well as by the type of wall materials used. In the literature, solubility values close to 95% have been reported for systems encapsulated with maltodextrin and potato starch, considered high [,,,]. Overall, the high solubility across all formulations suggests good dispersibility, consistent with the low moisture content, reduced water activity, and the observed particle size. These characteristics favor rapid hydration and disaggregation of the powders in aqueous media, supporting the adequate dispersibility of the microcapsules obtained.

Regarding particle size (Figure 4g), it increased progressively with higher core percentage and inlet temperature. Both factors and their interaction significantly influenced this parameter (p ≤ 0.05), with the effect of core content being the most pronounced (Figure 4h,i). The particle size of the microcapsules was larger than that reported in the study on microencapsulation of guinea pig blood erythrocytes, where the size measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) was 0.54–0.90 µm (NICOMP distribution) and 0.82–1.67 µm (Gaussian distribution) []. On the other hand, the sizes fall within the typical micrometric range reported for chicken meat powder obtained by spray drying (5.62–15.36 µm), supporting the consistency of the results within the micrometer scale [].

Overall, the greater effect of core concentration compared to inlet temperature is related to the increase in total solids and the viscosity of the feed mixture. As the proportion of peptides increases, protein retention improves, and the droplet formation during spray drying is altered, which affects both encapsulation efficiency and particle stability. Thus, the solid load and rheological behavior are more decisive than temperature variation within the studied range [,]. Moreover, these findings are consistent with broader evidence on the role of sugars in protein stabilization. For instance, trehalose has been shown to act as a protective sugar, preventing protein aggregation and enhancing stability under stress conditions, such as heat and dehydration. Recent reviews also highlight its neuroprotective role through mechanisms involving autophagy and protein stabilization []. In this sense, the evidence suggests that carbohydrates such as maltodextrin and trehalose, in conjunction with polysaccharides like tara gum, exert complementary functions in protein stabilization under stress conditions, thereby reinforcing the relevance of the encapsulating agents employed in this study.

Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying the loss of bioactivity and changes in functional properties may be related to the thermal and mass-transfer conditions inherent to spray drying. Several studies indicate that high temperatures can induce partial denaturation and reduce the accessibility of functional groups in peptides and proteins [,]. At the same time, the rapid formation of a surface film and moisture gradients affects the powder’s solubility, hygroscopicity, and dispersibility [,]. Similarly, the interaction between tara gum polysaccharides and carbohydrates such as maltodextrin contributes to structural stabilization against thermal stress [,]. Taken together, these effects help explain the functional behavior observed in collagen microcapsules.

3.3. SEM, FTIR, and TGA Analyses of Microcapsules

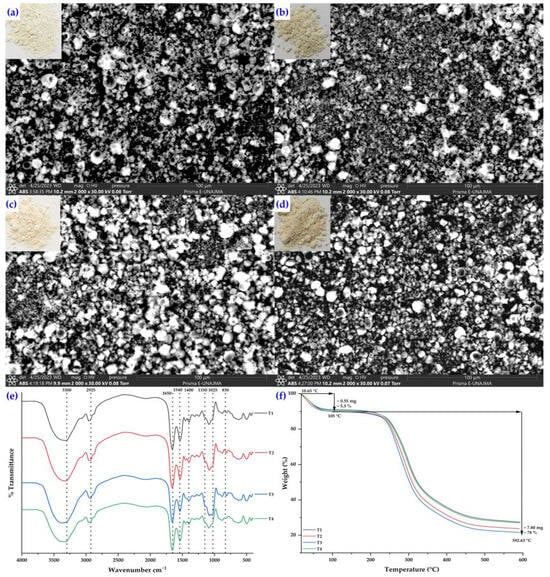

The SEM analysis revealed that the microencapsulation process was effective. The structural micrographs of the porcine hydrolyzed collagen microcapsules (Figure 5) reveal morphological variations among the four treatments, with microcapsules predominantly being spherical. Some exhibit indentations and dents, as well as amorphous structures and the agglomeration of smaller particles, which are typically observed in the spray-drying process [,,,,,,]. In T1 (Figure 5a) and T2 (Figure 5b), a greater number of particles with irregular morphology were observed, possibly associated with the combined presence of maltodextrin and tara gum as wall materials, consistent with reports on the influence of these components on the formation of amorphous structures [,,]. In T3 (Figure 5c) and T4 (Figure 5d), spherical-shaped microcapsules predominated, although dents and heterogeneous sizes were present; particularly, T3 exhibited greater uniformity and fewer deformations. Previous studies indicate that spray drying can induce particle shrinkage due to heating, reducing their size compared to unprocessed samples [,,,,], and that lower inlet temperatures favor the formation of wrinkled or amorphous particles, while a slowly forming surface film during drying may result in dents, wrinkles, cracks, or collapses [,,,,,]. These morphological variations directly affect the functionality of the microcapsules. Spherical and uniform shapes enhance stability and solubility, whereas wrinkled or amorphous particles may increase hygroscopicity and compromise storage stability. Tara gum represents an innovative component within the encapsulating matrix, whose role has been little explored compared to the widely studied function of maltodextrin. Some studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in combination with biopolymers and maltodextrin in microencapsulation processes, showing positive effects on the stability and physicochemical properties of microcapsules, which supports its influence on the observed morphology and functionality [,]. The observed morphology corresponds to a matrix-type microencapsulation, characteristic of spray drying, in which the core is distributed throughout the wall material. This homogeneous structure, lacking differentiated domains, has been widely reported in microcapsules obtained using this technology [,,,,].

Figure 5.

Structural micrographs of spray-dried porcine hydrolyzed collagen microcapsules corresponding to treatment T1 (a), treatment T2 (b), treatment T3 (c), and treatment T4 (d), as well as their FTIR spectra (e) and thermogravimetric analysis (f).

Figure 5e shows the FTIR spectra of the microcapsules (T1, T2, T3, and T4), where the leading characteristic bands of the wall materials (tara gum and maltodextrin) and hydrolyzed porcine collagen can be observed, confirming the effective encapsulation of the protein in the matrix. The broad band at 3300 cm−1 is associated with the stretching of the O–H and N–H groups, indicating the formation of hydrogen bonds between the components. At 2925 cm−1, the C–H stretching of aliphatic chains is observed, while the bands at 1650 and 1540 cm−1 (Amides I and II) correspond to C=O stretching and N–H bending coupled with C–N stretching, characteristic of collagen. The signal at 1400 cm−1 is attributed to the deformation of the CH2 and CH3 groups, and the bands at 1150 and 1025 cm−1 to the C–O–C and C–O vibrations of the glycosidic bonds present in polysaccharides. Finally, the weak band at 830 cm−1 corresponds to the vibrations of the peptide backbone, associated with the helical structure of collagen. Taken together, the results confirm the chemical compatibility between the biopolymers and collagen, as well as the partial preservation of their structure after spray drying [,].

Figure 5f shows the TGA thermograms of the microcapsules corresponding to treatments T1, T2, T3, and T4, which were formulated with hydrolyzed porcine collagen as the core and tara gum and maltodextrin as the wall materials. In all samples, an initial average mass loss of 5.5% is observed at 105 °C, attributed to the removal of adsorbed moisture and water physically retained by the hydroxyl and peptide groups of the polymer matrix. The main thermal degradation occurs between 200 °C and 400 °C, associated with the breakdown of the glycosidic bonds of maltodextrin and tara gum, as well as the peptide bonds of hydrolyzed collagen. At temperatures close to 592 °C, the microcapsules exhibit a total mass loss of approximately 78%, resulting in a carbonaceous residue of 22%, which is characteristic of natural, carbon-rich biopolymers. These results confirm the thermal stability of the formulations and the adequate structural interaction between the hydrolyzed collagen and the wall materials [,,].

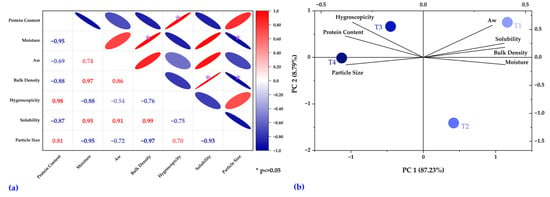

3.4. Pearson Correlation Matrix and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

The Pearson correlation matrix (Figure 6a) allows visualization of the linear correlations between the physicochemical and techno-functional properties []. In this case, positive coefficients are represented in red and negative ones in blue. At the same time, the intensity of the color and the shape of the ellipses reflect the magnitude of the correlation. In addition, asterisks indicate statistically significant relationships (p ≤ 0.05). In the present study, robust positive correlations were identified, such as between moisture and bulk density (r = 0.97), solubility and bulk density (r = 0.99), and hygroscopicity and protein content (r = 0.98). Likewise, marked negative correlations were observed between protein content and moisture (r =−0.95) and between particle size and moisture (r = −0.95).

Figure 6.

Pearson correlation matrix, with asterisks indicating significant correlations (p ≤ 0.05) (a), and PCA showing the distribution of treatments and their association with the variables (b).

The principal component analysis (Figure 6b) allowed the representation of the distribution of the treatments (T1–T4) in the two-dimensional space defined by the first two principal components, which explain 87.23% (PC1) and 8.79% (PC2) of the total variability. This analysis facilitates the identification of associations between variables and treatments, showing, for example, that T1 is closely associated with aw, solubility, bulk density, and moisture; T3 is associated with hygroscopicity; and T4 with protein content and particle size. In turn, T2 presents a differentiated behavior, located in an area opposite to most variables, suggesting a distinctive physicochemical profile. Among the evaluated formulations, the one processed at 160 °C with a 10% core content showed the highest protein content, good stability, and dispersibility.

Complementarily, the PCA of the evaluated properties allowed establishing relationships among complex variables, providing an integrated view of their interactions and facilitating the identification of significant trends, which could contribute to the design and optimization of microcapsule formulations with specific properties [,,]. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for researchers and offer innovative opportunities for the food and nutraceutical industries by incorporating collagen-based microcapsules. Moreover, livestock producers and policymakers gain a sustainable alternative for valorizing animal by-products, aligned with the principles of the circular economy.

Variations in microcapsule properties are explained by the combined effect of inlet temperature, core ratio, and tara gum–maltodextrin matrix. The reduction in moisture and water activity at higher temperatures is due to faster evaporation and the formation of a surface film during spray drying [,]. The higher hygroscopicity in formulations with more core is related to the hydrating affinity of collagen peptides [,]. In contrast, the high solubility is attributed to the amorphous and dispersible nature of maltodextrin [,]. The increase in particle size with increasing solids content is consistent with that observed for spray-dried protein hydrolysates []. In addition, hydrogen bond interactions between maltodextrin and tara gum support the structural stability observed via SEM and FTIR [,]. Taken together, these mechanisms justify the correlations identified in the PCA.

4. Conclusions

This study confirms that microencapsulation of hydrolyzed porcine collagen by spray drying, using maltodextrin and tara gum as wall materials, yields a powder with physicochemical, techno-functional, and structural properties suitable for incorporation into food and nutraceutical products. The process conditions analyzed showed that both the drying temperature and the core ratio influence the properties studied. Among the formulations evaluated, the one made at 160 °C with a 10% core had the highest protein content, microbiological stability, and dispersion capacity, making it a feasible technological alternative for adding value to meat by-products. These results support the potential of microencapsulated porcine collagen for developing new functional products, promoting sustainability, and the comprehensive utilization of raw materials of animal origin.

Furthermore, the descriptive model developed in this study indicates that the combined effects of core proportion, drying temperature, residual moisture, and the matrix-like structure formed during spray drying explain the behavior of the different responses, reinforcing the technological relevance of the optimal treatment identified. Additionally, FTIR confirmed the preservation of characteristic collagen bands and the compatibility between the core and wall materials, while TGA evidenced the thermal stability of the microcapsules.

However, the findings should be considered exploratory, as the experimental region needs to be expanded to optimize the study variables. Additionally, the study did not determine the encapsulation efficiency, which would require the specific quantification of retained bioactive peptides; this limitation is acknowledged and will be addressed in future work. In this sense, the present research provides initial evidence and serves as a starting point for future studies aimed at optimizing drying conditions and validating industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.L.-S. and T.G.C.-B.; methodology, C.A.L.-S., T.G.C.-B., D.C.-Q., H.P.-R., F.T.-P. and E.M.-M.; software, D.C.-Q. and H.P.-R.; validation, F.T.-P. and E.M.-M.; formal analysis, M.M.-M. and R.L.-A.; investigation, M.M.-M., R.L.-A., J.C.C., J.C.M.-S., U.R.Q.-Q. and E.E.J.-C.; data curation, J.C.C., J.C.M.-S. and E.E.J.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.L.-S. and T.G.C.-B.; writing—review and editing, D.C.-Q. and H.P.-R.; supervision, F.T.-P. and E.M.-M.; project administration, U.R.Q.-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research group on nutraceuticals and biomaterials of the UNAJMA supported the project.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Food Nanotechnology Research Laboratory of UNAJMA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A | Inlet Temperature |

| AB | Interaction between A and B |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| aw | Water Activity |

| B | Core Content |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| He–Ne | Helium–Neon |

| N | Normality |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PC1 | First Principal Component |

| PC2 | Second Principal Component |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SENASA | Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria (Peru) |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| T1 | Treatment 1 (140 °C; 5% core, w/w) |

| T2 | Treatment 2 (160 °C; 5% core, w/w) |

| T3 | Treatment 3 (140 °C; 10% core, w/w) |

| T4 | Treatment 4 (160 °C; 10% core, w/w) |

| w/w | Weight/Weight (mass fraction) |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

References

- Pinto, J.; Boavida-Dias, R.; Matos, H.A.; Azevedo, J. Analysis of the Food Loss and Waste Valorisation of Animal By-Products from the Retail Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-López, A.; Morales-Peñaloza, A.; Martínez-Juárez, V.M.; Vargas-Torres, A.; Zeugolis, D.I.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G. Hydrolyzed Collagen—Sources and Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, A.; Gallo, N.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Masi, A.; Lassandro, R.; Sannino, A.; Salvatore, L.; Bunk, O.; Giannini, C.; et al. Travelling through the Natural Hierarchies of Type I Collagen with X-rays: From Tendons of Cattle, Horses, Sheep and Pigs. Materials 2023, 16, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Lv, B.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Q.; Sheng, B.; Zhao, D.; Li, C. Digestion Profiles of Protein in Edible Pork By-Products. Foods 2022, 11, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Xiao, Z.; Ge, C.; Wu, Y. Animal by-products collagen and derived peptide, as important components of innovative sustainable food systems—A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8703–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibekov, R.S.; Alibekova, Z.I.; Bakhtybekova, A.R.; Taip, F.S.; Urazbayeva, K.A.; Kobzhasarova, Z.I. Review of the slaughter wastes and the meat by-products recycling opportunities. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1410640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Calsina-Ponce, W.C.; Cruz, G.D.; Calderón Huamaní, D.F.; Cabel-Moscoso, D.J.; Garcia-Espinoza, A.J.; Sucari-León, R.; Aroquipa-Durán, Y.; Muñoz-Saenz, J.C.; et al. Technological Innovations and Circular Economy in the Valorization of Agri-Food By-Products: Advances, Challenges and Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewat, A.; Shakila, R.J.; Sharma, M.; Mishra, P. The use of spray drying technology to reduce bitter taste of fish collagen hydrolysate. J. Exp. Zool. India 2022, 25, 2383. [Google Scholar]

- Sanprasert, S.; Kumnerdsiri, P.; Seubsai, A.; Lueangjaroenkit, P.; Pongsetkul, J.; Indriani, S.; Petcharat, T.; Sai-ut, S.; Hunsakul, K.; Issara, U.; et al. Techno-Functional, Rheological, and Physico-Chemical Properties of Gelatin Capsule By-Product for Future Functional Food Ingredients. Foods 2025, 14, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluk, E.; Yeliz, K.; Orhan, Ö. Production of Bone Broth Powder with Spray Drying Using Three Different Carrier Agents. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018, 38, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Terán-Figueroa, Y.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Álvarez-Salas, C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Encapsulation of Active Ingredients in Food Industry by Spray-Drying and Nano Spray-Drying Technologies. Processes 2020, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, E. Wall Materials for Encapsulating Bioactive Compounds via Spray-Drying: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani, M.; Siahtiri, S.; Besati, M.; Baghani, M.; Baniassadi, M.; Nejad, A.M. Microencapsulation of natural products using spray drying; an overview. J. Microencapsul. 2024, 41, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraquero-García, C.; Pérez-Gálvez, R.; Espejo-Carpio, F.J.; Guadix, A.; Guadix, E.M.; García-Moreno, P.J. Encapsulation of Bioactive Peptides by Spray-Drying and Electrospraying. Foods 2023, 12, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.O.; da Rocha, M.; Alemán, A.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Tovar, C.A.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Montero, P.; Prentice, C. Yogurt Fortification by the Addition of Microencapsulated Stripped Weakfish (Cynoscion guatucupa) Protein Hydrolysate. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusi-Chipana, R.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E. Stability of Nanoparticles of Bioactive Compounds from Native Potato (Solanum tuberosum spp. andigena) in Yogurt. In Advances in Sciences Behind Food, Energy, and Innovation: Selected Contributions to the 10th International Congress on Agroindustrial Engineering, CIIA-2024; Vilalta-Alonso, G., de Castro Pellegrini, C., Llanes-Santiago, O., Soto Pau, F., Radrigán-Ewoldt, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; De la Cruz, G.; Luciano-Alipio, R.; Calsina Ponce, W.C.; Sucari-León, R.; Quispe-Quezada, U.R.; et al. Preliminary Assessment of Tara Gum as a Wall Material: Physicochemical, Structural, Thermal, and Rheological Analyses of Different Drying Methods. Polymers 2024, 16, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuaychan, S.; Benjakul, S. Effect of maltodextrin on characteristics and antioxidative activity of spray-dried powder of gelatin and gelatin hydrolysate from scales of spotted golden goatfish. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3583–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Muñoz, D.P.; Kurozawa, L.E. Influence of combined hydrolyzed collagen and maltodextrin as carrier agents in spray drying of cocona pulp. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2020, 23, e2019254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudžiuvelytė, L.; Petrauskaitė, E.; Stabrauskienė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Spray-Drying Microencapsulation of Natural Bioactives: Advances in Sustainable Wall Materials. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, H.K.S.; Fagundes-Klen, M.R.; Fiorese, M.L.; Triques, C.C.; da Silva, L.C.; Canan, C.; Rossin, A.R.S.; Furtado, C.H.; Maluf, J.U.; da Silva, E.A. Microencapsulation of Porcine Liver Hydrolysate by Spray Drying and Freeze-Drying with Different Carrier Agents. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 2397–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halahlah, A.; Piironen, V.; Mikkonen, K.S.; Ho, T.M. Polysaccharides as wall materials in spray-dried microencapsulation of bioactive compounds: Physicochemical properties and characterization. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 6983–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano-Laura, F.Y.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H. Influence of Core Percentage and Inlet Temperature on the Microencapsulation of Guinea Pig Blood Erythrocytes in Tara Gum and Quinoa Starch Matrices. In Advances in Sciences Behind Food, Energy, and Innovation: Selected Contributions to the 10th International Congress on Agroindustrial Engineering, CIIA-2024; Vilalta-Alonso, G., de Castro Pellegrini, C., Llanes-Santiago, O., Soto Pau, F., Radrigán-Ewoldt, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; De la Cruz, G.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; Muñoz-Saenz, J.C.; Muñoz-Melgarejo, M.; Quispe-Quezada, U.R.; et al. Microencapsulation of Propolis and Honey Using Mixtures of Maltodextrin/Tara Gum and Modified Native Potato Starch/Tara Gum. Foods 2023, 12, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabrauskiene, J.; Pudziuvelyte, L.; Bernatoniene, J. Optimizing Encapsulation: Comparative Analysis of Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying for Sustainable Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus x paradisi L. Peels. Pharm. 2024, 17, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, R.; Ibarz, A.; Pagan, J. Hidrolizados de proteína: Procesos y aplicaciones. Acta Bioquímica Clínica Latinoam. 2008, 42, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, W. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Volume I, Agricultural Chemicals, Contaminants, Drugs; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fasoyiro, S.; Hovingh, R.; Gourama, H.; Cutter, C. Change in Water Activity and Fungal Counts of Maize-pigeon Pea Flour During Storage Utilizing Various Packaging Materials. Procedia Eng. 2016, 159, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Cruz, G.D.; Martínez-Huamán, E.L.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; Muñoz-Saenz, J.C.; et al. Obtaining and Characterizing Andean Multi-Floral Propolis Nanoencapsulates in Polymeric Matrices. Foods 2022, 11, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Aguirre Landa, J.P.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; Muñoz-Saenz, J.C.; Quispe-Quezada, U.R.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; et al. Nanoencapsulation of Phenolic Extracts from Native Potato Clones (Solanum tuberosum spp. andigena) by Spray Drying. Molecules 2023, 28, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Pozo, L.M.F.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Gutiérrez, R.J.G.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E. Effect of Inlet Air Temperature and Quinoa Starch/Gum Arabic Ratio on Nanoencapsulation of Bioactive Compounds from Andean Potato Cultivars by Spray-Drying. Molecules 2023, 28, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Martínez-Huamán, E.L.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E.; Aroni-Huamán, J.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; Palomino-Rincón, W.; et al. Microencapsulation of Erythrocytes Extracted from Cavia porcellus Blood in Matrices of Tara Gum and Native Potato Starch. Foods 2022, 11, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutavski, Z.; Vidović, S.; Lazarević, Z.; Ambrus, R.; Motzwickler-Németh, A.; Aladić, K.; Nastić, N. Stabilization and Preservation of Bioactive Compounds in Black Elderberry By-Product Extracts Using Maltodextrin and Gum Arabic via Spray Drying. Foods 2025, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, S.; Nan, Z.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Ding, J.; Lv, Y.; Yang, J. Detection of dextran, maltodextrin and soluble starch in the adulterated Lycium barbarum polysaccharides (LBPs) using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and machine learning models. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlov, I.F.; Titov, E.I.; Semenov, G.V.; Slozhenkina, M.I.; Sokolov, A.Y.; Omarov, R.S.; Goncharov, A.I.; Zlobina, E.Y.; Litvinova, E.V.; Karpenko, E.V. Collagen from porcine skin: A method of extraction and structural properties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.M.; Fontoura, A.M.d.; Vidal, A.R.; Dornelles, R.C.P.; Kubota, E.H.; Mello, R.d.O.; Cansian, R.L.; Demiate, I.M.; Oliveira, C.S.d. Characterization of hydrolysates of collagen from mechanically separated chicken meat residue. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Guzmán Gutiérrez, R.J.; Banda Mozo, I. Microencapsulation of Propolis by Complex Coacervation with Chia Mucilage and Gelatin: Antioxidant Stability and Functional Potential. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvera Herrera, M.D. Determinación de los Parámetros Óptimos para la Extracción y Caracterización del Colágeno a Partir de Piel de Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus); Universidad Nacional Micaela Bastidas de Apurímac: Abancay, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido Castelán, E. Efecto de las Proteínas de la Piel de Cerdo Sobre la Textura de Salchichas; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo: Pachuca, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani Charca, M.D. Obtención de Colágeno Hidrolizado de Bovino a Través de Procesos Enzimáticos; Universidad Mayor de San Andrés: La Paz, Bolivia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.J.; Light, N.D. Connective Tissue in Meat and Meat Products; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Palamutoğlu, R.; Sariçoban, C. The Effect of the Addition of Encapsulated Collagen Hydrolysate on Some Quality Characteristics of Sucuk. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2016, 36, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozawa, L.E.; Park, K.J.; Hubinger, M.D. Effect of maltodextrin and gum arabic on water sorption and glass transition temperature of spray dried chicken meat hydrolysate protein. J. Food Eng. 2009, 91, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamutoğlu, R.; Sarıçoban, C. Physico-chemical investigation and antioxidant activity of encapsulated fish collagen hydrolyzates with maltodextrin. Ann. Univ. Dunarea Jos Galati Fascicle VI—Food Technol. 2019, 43, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.A.; Trindade, M.A.; Netto, F.M.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Microcapsules of a Casein Hydrolysate: Production, Characterization, and Application in Protein Bars. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2009, 15, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premi, M.; Sharma, H.K. Effect of different combinations of maltodextrin, gum arabic and whey protein concentrate on the encapsulation behavior and oxidative stability of spray dried drumstick (Moringa oleifera) oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruengdech, A.; Siripatrawan, U. Improving encapsulating efficiency, stability, and antioxidant activity of catechin nanoemulsion using foam mat freeze-drying: The effect of wall material types and concentrations. Lwt 2022, 162, 113478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotarelli, M.F.; da Silva, V.M.; Durigon, A.; Hubinger, M.D.; Laurindo, J.B. Production of mango powder by spray drying and cast-tape drying. Powder Technol. 2017, 305, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kha, T.C.; Nguyen, M.H.; Roach, P.D. Effects of spray drying conditions on the physicochemical and antioxidant properties of the Gac (Momordica cochinchinensis) fruit aril powder. J. Food Eng. 2010, 98, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Arboleda Mejia, J.A.; Versari, A.; Chiarello, E.; Bordoni, A.; Parpinello, G.P. Microencapsulation of polyphenolic compounds recovered from red wine lees: Process optimization and nutraceutical study. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 132, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maag, P.; Dirr, S.; Özmutlu Karslioglu, Ö. Investigation of Bioavailability and Food-Processing Properties of Arthrospira platensis by Enzymatic Treatment and Micro-Encapsulation by Spray Drying. Foods 2022, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Molina, N.; Parada, J.; Zambrano, A.; Chipon, C.; Robert, P.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Microencapsulation of Durvillaea incurvata Polyphenols: Toward a Stable Anti-Inflammatory Ingredient for Functional Foods. Foods 2025, 14, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Kaur, K.; Mehta, N.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Kennedy, J.F. Characterization and optimization of spray dried iron and zinc nanoencapsules based on potato starch and maltodextrin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 282, 119107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Clardy, A.; Hui, D.; Wu, Y. Physiochemical properties of encapsulated bitter melon juice using spray drying. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2021, 26, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslemi, M.; Hosseini, H.; Erfan, M.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Fard, R.M.N.; Neyestani, T.R.; Komeyli, R. Characterisation of spray-dried microparticles containing iron coated by pectin/resistant starch. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.V.d.B.; Borges, S.V.; Botrel, D.A. Gum arabic/starch/maltodextrin/inulin as wall materials on the microencapsulation of rosemary essential oil. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, D.H.; Wardana, I.N.; Ulya, H.N.; Cahyono, H.; Kumoro, A.C.; Aryanti, N. The effect of spray-drying inlet conditions on iron encapsulation using hydrolysed glucomannan as a matrix. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 123, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Díaz, C.; Leal-Calderon, F.; Mosi-Roa, Y.; Chacón-Fuentes, M.; Garrido-Miranda, K.; Opazo-Navarrete, M.; Quiroz, A.; Bustamante, M. Enhancing the Retention and Oxidative Stability of Volatile Flavors: A Novel Approach Utilizing O/W Pickering Emulsions Based on Agri-Food Byproducts and Spray-Drying. Foods 2024, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.; Khawar, M.; Böhm, B.; Gryczke, A.; Ries, F. Experimental Investigation of Spray Drying Breakup Regimes of a PVP-VA 64 Solution Using High-Speed Imaging. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binas, S.; Mardani, M.; Siahtiri, S.; Nejad, A.M. Trehalose and Neurodegeneration: A Review of Its Role in Autophagy, Protein Aggregation, and Neuroprotection. ASME Open J. Eng. 2025, 4, 040805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samborska, K.; Poozesh, S.; Barańska, A.; Sobulska, M.; Jedlińska, A.; Arpagaus, C.; Malekjani, N.; Jafari, S.M. Innovations in spray drying process for food and pharma industries. J. Food Eng. 2022, 321, 110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopde, S.; Datir, R.; Deshmukh, G.; Dhotre, A.; Patil, M. Nanoparticle formation by nanospray drying & its application in nanoencapsulation of food bioactive ingredients. J. Agric. Food Res. 2020, 2, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, A.; Wells, S.; Pratap-Singh, A. Impact of Product Formulation on Spray-Dried Microencapsulated Zinc for Food Fortification. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 2286–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordón, M.G.; Alasino, N.P.X.; Villanueva-Lazo, Á.; Carrera-Sánchez, C.; Pedroche-Jiménez, J.; Millán-Linares, M.d.C.; Ribotta, P.D.; Martínez, M.L. Scale-up and optimization of the spray drying conditions for the development of functional microparticles based on chia oil. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 130, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Montalbano, F.; Zizzo, M.G.; Puleio, R.; Caldara, G.; Cicero, L.; Cassata, G.; Licciardi, M. Enhanced anticancer effect of quercetin microparticles formulation obtained by spray drying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2739–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, S.C.S.R.; Schettini, G.N.; Gallina, D.A.; Dutra Alvim, I.; Hubinger, M.D. Microencapsulation of hibiscus bioactives and its application in yogurt. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueik, V.; Diosady, L.L. Microencapsulation of iron in a reversed enteric coating using spray drying technology for double fortification of salt with iodine and iron. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, L.D.; Zzaman, W.; Abedin, M.Z.; Yang, T.A. Optimization of Spray Drying Process in Commercial Hydrolyzed Fish Scale Collagen and Characterization by Scanning Electron Microscope and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Duarte, M.E.; Cavalcanti-Mata, M.E. Modeling of food drying processes in industrial spray dryers. Food Bioprod. Process. 2018, 107, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Wagh, P.; Naik, J. Solvent evaporation and spray drying technique for micro- and nanospheres/particles preparation: A review. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpagaus, C.; John, P.; Collenberg, A.; Rütti, D. 10—Nanocapsules formation by nano spray drying. In Nanoencapsulation Technologies for the Food and Nutraceutical Industries; Jafari, S.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 346–401. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Cronin, K.; Maidannyk, V.; Miao, S. Breakage behaviour and functionality of spray-dried agglomerated model infant milk formula: Effect of proteins and carbohydrates content. Food Chem. 2022, 391, 133179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Okuyama, K. Progress in developing spray-drying methods for the production of controlled morphology particles: From the nanometer to submicrometer size ranges. Adv. Powder Technol. 2011, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari-Varzaneh, E.; Shahedi, M.; Shekarchizadeh, H. Iron microencapsulation in gum tragacanth using solvent evaporation method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, Y.; Adzahan, N.M.; Yusof, Y.A.; Muhammad, K. Effect of wall materials on the spray drying efficiency, powder properties and stability of bioactive compounds in tamarillo juice microencapsulation. Powder Technol. 2018, 328, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Júnior, M.E.; Araújo, M.V.R.L.; Martins, A.C.S.; dos Santos Lima, M.; da Silva, F.L.H.; Converti, A.; Maciel, M.I.S. Microencapsulation by spray-drying and freeze-drying of extract of phenolic compounds obtained from ciriguela peel. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, B.T.; Baiocco, D.; Al-Sharabi, M.; Routh, A.F.; Zhang, Z.; Cayre, O.J. Current Challenges in Microcapsule Designs and Microencapsulation Processes: A Review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 40326–40355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E. Microencapsulation of bioactive compounds from Hesperomeles escalloniifolia Schltdl (Capachu) in quinoa starch and Tara Gum. CyTA—J. Food 2025, 23, 2564354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Arévalo-Quijano, J.C.; Cruz, G.D.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L.; Quispe-Quezada, U.R.; Gutiérrez-Gómez, E.; Cabel-Moscoso, D.J.; et al. Native Potato Starch and Tara Gum as Polymeric Matrices to Obtain Iron-Loaded Microcapsules from Ovine and Bovine Erythrocytes. Polymers 2023, 15, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vítězová, M.; Jančiková, S.; Dordević, D.; Vítěz, T.; Elbl, J.; Hanišáková, N.; Jampílek, J.; Kushkevych, I. The Possibility of Using Spent Coffee Grounds to Improve Wastewater Treatment Due to Respiration Activity of Microorganisms. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).