Abstract

Predicting blast-induced vibrations in twin tunnels is challenging due to complex wave-cavity interactions, which render conventional scaled-distance (PPV-SD) models inadequate. This study introduces a hybrid empirical-probabilistic framework to quantify the probability of exceeding regulatory vibration thresholds. Field data from the Northern Marmara Highway project first quantitatively confirm the severe degradation of the classical scaled-distance (PPV-SD) method in twin-tunnel geometry, reducing a strong correlation (R = 0.82) to insignificance. A Random Forest sensitivity analysis, applied to 123 blast records, ranked the governing parameters, guiding the development of a deterministic multi-parameter regression model (R = 0.72). The core innovation of this framework is the embedding of this deterministic model within a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) to propagate documented input uncertainties, thereby generating a full probability distribution for PPV. This represents a fundamental advance beyond deterministic point-estimates, as it enables the direct calculation of exceedance probabilities for risk-informed decision-making. For instance, for a regulatory threshold of 10 mm/s, the framework quantified the exceedance probability as P (PPV > 10 mm/s) = 5.2%. The framework’s robustness was demonstrated via validation against 100 independent blast records, which showed strong calibration with 94% of observed PPV values captured within the model’s 90% confidence interval. This computationally efficient framework (<10,000 iterations) provides engineers with a practical tool for moving from deterministic safety factors to quantifiable, risk-informed decision-making.

1. Introduction

The management of blast-induced vibrations presents a critical challenge in urban tunneling, a problem that is significantly amplified during the construction of closely-spaced twin tunnels. The dynamic interaction between adjacent underground voids—known as the “cavity effect”—fundamentally disrupts seismic wave propagation. A growing body of empirical evidence indicates that this geometric phenomenon can exert a more dominant influence on vibration patterns than even substantial lithological variations, thereby directly challenging the core assumptions of conventional predictive models [1,2].

The physical basis for this challenge is rooted in wave mechanics. An underground cavity acts as a massive impedance discontinuity, creating a sharp interface between a high-impedance rock mass and a low-impedance, air-filled void. When an incident seismic wavefront encounters this boundary, it undergoes a complex process of energy partitioning: a portion is reflected back into the rock mass, another is refracted or diffracted around the void, and another may be trapped, setting up standing waves or focusing effects [3,4]. The resulting vibration field at any given point is the vector sum of these direct, reflected, and diffracted waves, leading to intricate patterns of constructive and destructive interference. This transforms the problem from one of simple geometric attenuation to one of complex wavefield synthesis—a problem the classical scaled-distance law is utterly unequipped to handle [5,6].

The challenges of predicting dynamic wave interactions with underground structures are not unique to blast-induced vibrations. A significant body of research in seismic engineering has long grappled with the complexities of wave-soil-structure interaction. For instance, Abate and Massimino [7] demonstrated through detailed parametric finite element analysis that the presence of a tunnel can significantly alter seismic wave propagation, often leading to de-amplification at the ground surface—a finding with beneficial implications for urban seismic risk. Complementing this, studies on seismic mitigation, such as Maleska et al. [8], have shown that engineered materials like expanded polystyrene (EPS) geofoam can effectively dampen seismic energy and protect underground structures by absorbing and redistributing dynamic stresses. These studies underscore a critical theme: the geometry and composition of underground cavities, as well as the surrounding medium, fundamentally control the propagation and impact of dynamic waves. This principle is directly transferable to the context of blast-induced vibrations, where the “cavity effect” represents a similarly complex wave-cavity-structure interaction problem.

Using comprehensive field data from the Northern Marmara Highway twin tunnels project, this study first quantitatively demonstrates the failure of standard methods and subsequently develops and validates a novel probabilistic framework designed to overcome these limitations. The literature currently lacks a framework that integrates a physically-informed, site-calibrated model with a rigorous uncertainty quantification method to translate a deterministic prediction into a probabilistic risk metric. Therefore, practitioners still lack a robust methodology to answer the most critical operational question: “For a given blast design, what is the numerical probability of exceeding the regulatory safety threshold?”

To bridge this gap, this study proposes a hybrid empirical-probabilistic framework anchored in Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS), which is specifically designed to answer this precise operational question. The MCS method was selected as the core of the framework for several compelling reasons: (1) It seamlessly integrates with empirically-derived regression models, requiring no complex constitutive material models. (2) It is exceptionally well-suited for propagating input parameter uncertainties through a non-linear model. (3) It directly provides the full probability distribution of PPV, enabling the direct calculation of exceedance probabilities. This capability stands in stark contrast to prior machine-learning or advanced numerical models [9,10], which, despite offering improved point estimates, remain deterministic in nature. While these models predict a single ‘most likely’ PPV value, they cannot quantify the likelihood of exceeding a critical threshold—the very essence of risk. This MCS framework, by contrast, explicitly quantifies this risk by generating a full distribution of potential outcomes. This output is directly interpretable as risk, moving practice from deterministic safety factors to a quantifiable probability of failure, aligning with the philosophical shift advocated by risk assessment pioneers like Harrison [11]. MCS has proven its value in related geotechnical problems, including the probabilistic estimation of fly rock distances [12,13,14], prediction of ground vibration propagation [15], and assessment of blast-induced damage [16].

2. Aim of the Study

The primary aim of this study is to bridge the critical gap between deterministic blast vibration prediction models and the need for quantifiable risk assessment in twin-tunnel projects. This is achieved by introducing a novel hybrid empirical-probabilistic framework. This study distinguishes itself from existing literature by moving beyond point estimates to provide a full probability distribution of Peak Particle Velocity (PPV), enabling the direct calculation of exceedance probabilities—a capability absent in current state-of-the-art models, whether based on sophisticated numerical analysis or machine learning.

The specific objectives are:

- To quantitatively document the deterioration of the classical PPV-SD correlation using field data from single and twin-tunnel excavation phases.

- To identify the most influential parameters governing PPV in twin-tunnels.

- To develop a deterministic multi-parameter predictive model based on the findings of the sensitivity analysis.

- To integrate this deterministic model into a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) framework to propagate input uncertainties and derive a full probability distribution of PPV.

- To rigorously validate the probabilistic framework by assessing its calibration against an independent dataset.

The ultimate engineering contribution of this work lies in providing a practical, computationally efficient tool that enables engineers to proactively manage blast vibration risks in complex geometries, thereby optimizing both safety and operational efficiency.

3. Literature Review

The evolution of research on the cavity effect began with foundational studies that moved it from an anecdotal concern to a documented phenomenon. Hao et al. [3], in a seminal theoretical and numerical analysis, systematically demonstrated that cavities act as powerful scatterers of seismic waves, with the effect heavily dependent on the ratio of wavelength to cavity size. Building on this, Shin et al. [1] issued a direct challenge to industry practice, cautioning that conventional PPV prediction formulas “often fail in discontinuous rock masses with cavities.”

Subsequent research has further delineated the complex spatial and spectral manifestations of the cavity effect. There is a broad consensus that cavities redistribute seismic energy non-uniformly, creating a complex mosaic of vibration risk characterized by localized amplification and “shadow” zones [17]. This redistribution is empirically evidenced by observations that vibrations in an adjacent tunnel can, at close ranges, exceed those in the actively blasting tunnel [18]. Moreover, the cavity effect is profoundly frequency-dependent; cavities act as low-pass filters, preferentially attenuating higher-frequency components [19], and exhibit directional characteristics [20]. These spectral and directional alterations critically complicate the assessment of potential structural resonance in nearby infrastructure.

Recent contributions have continued to deepen our understanding. High-accuracy predictive formulas [18], improved signal processing techniques [21], and integrated field and numerical studies [22] have been developed. Li et al. [9] provided a practical empirical equation for predicting PPV on adjacent tunnels using the Geological Strength Index (GSI), bypassing the need for initial site-specific data. Crucially, studies have begun to provide physically grounded damage criteria. Zhou et al. [23], through advanced LS-DYNA modeling of twin-arch tunnels, established a linear relationship between dynamic tensile stress in the concrete lining and the product of wave impedance and PPV, validating a critical PPV threshold of 23.3 cm/s for C30 concrete failure. This finding is powerfully corroborated by the independent field and numerical study of Liu et al. [24], who established a similar linear relationship, and is supported by the earlier theoretical work of Li et al. [25]. Adding to this, Wang et al. [26] conducted a meticulous field and numerical investigation on zero-spacing twin tunnels, identifying the right hance as the critical point of maximum Principal Tensile Stress and systematically evaluating mitigation strategies like excavation sequence optimization, reduced excavation footage, and EPS damping layers.

Despite these significant advancements, a critical methodological chasm persists, particularly for practicing engineers. The current state-of-the-art, encompassing both sophisticated numerical models and contemporary machine-learning techniques [9,11], remains predominantly deterministic, yielding a single “most likely” PPV value. This paradigm is fundamentally inadequate as it ignores the inherent, significant uncertainties stemming from stochastic charge release, spatially variable rock mass properties, and highly complex wave-cavity interactions. While recent studies provide improved point estimates, they fail to quantify the risk associated with these estimates. Consequently, a pronounced disconnect exists between high-fidelity academic models and the practical, quantifiable risk-assessment tools required for daily decision-making.

The complexities of dynamic wave interaction with underground cavities are a recurring theme beyond blast engineering, particularly in seismic analysis. Seismic studies provide a valuable parallel, emphasizing that the presence of tunnels and the properties of the surrounding medium are dominant factors in wave propagation. Abate and Massimino [7], in a comprehensive parametric finite element study, quantified how tunnels alter seismic wave paths, often causing de-amplification at the ground surface—a finding that highlights the potential for underground structures to mitigate vibration risks in urban environments. Their work on fully-coupled tunnel–soil–aboveground building systems reveals the non-negligible interactions that can influence dynamic forces in the tunnel lining. Further advancing this field, research on seismic mitigation strategies offers insights applicable to vibration control in general. For example, Maleska et al. [8] numerically demonstrated that incorporating EPS geofoam as a damping material around a soil-steel composite bridge effectively reduced seismic deformations and stresses by absorbing wave energy and redistributing loads away from the structure. The core principle emerging from these seismic studies—that cavity geometry and strategic material use can dramatically reshape the dynamic response—resonates strongly with the challenges of blast-induced vibrations in twin tunnels. It underscores that the “cavity effect” is a manifestation of a broader class of wave-cavity-structure interaction problems, where lessons from one domain of dynamic loading can inform solutions in another.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Methodology and Framework Development

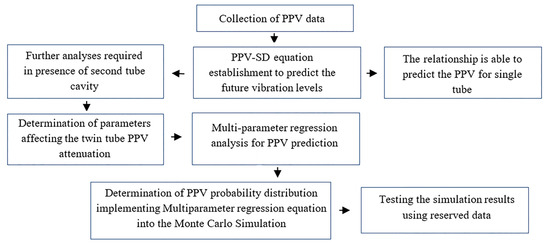

The research methodology was structured as a sequential, decision-driven framework designed to systematically address the distinct challenges of blast vibration prediction in single and twin-tunnel environments. The overall workflow, depicted in Figure 1, progressed through critical stages, each informed by empirical data analysis and the evolving geometric conditions of the excavation site. This structured approach ensured a logical and defensible transition from simple empirical correlation to a sophisticated, validated, probabilistic framework.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the sequential, decision-driven research methodology for PPV analysis in twin tunnels, from data collection to probabilistic validation.

The methodology commenced with the collection of Peak Particle Velocity (PPV) data from field monitoring stations. An initial dataset of 59 records from the single-tunnel excavation phase established a reliable baseline. A pivotal condition check was the introduction of the second cavity. Empirical evidence from the subsequent twin-tunnel excavation phase (123 records from the right tunnel) revealed a fundamental shift in vibration behavior, characterized by a significant deterioration of the previously robust PPV-Scaled Distance (PPV-SD) correlation. This empirical deterioration triggered the necessity for a more sophisticated, multi-parameter analysis path specific to the twin-tunnel geometry.

For the single-tunnel excavation phase, the classical PPV-SD approach remained sufficient and effective. A site-specific PPV-SD equation was established, demonstrating a strong correlation (R = 0.82) and proving capable of reliably predicting vibration levels for that specific, simple geometric condition.

In contrast, addressing the complex twin-tunnel condition required a multi-parameter and probabilistic path. The methodology first involved a rigorous determination of the governing parameters affecting PPV attenuation, achieved through a comprehensive sensitivity analysis using the Random Forest algorithm on the dataset of 123 blast records. This ensured the subsequent predictive model was founded upon physically meaningful and statistically significant variables.

Following the parameter selection, a multi-parameter linear regression model was developed for the twin-tunnel scenario. This model form was selected for three primary reasons: (1) Computational Efficiency: Its low computational cost is critical for the thousands of iterations required by the subsequent Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS). (2) Interpretability and Uncertainty Propagation: The linear structure provides transparency and allows for the straightforward propagation of input uncertainties through first-order second-moment (FOSM) principles, unlike the more complex uncertainty paths in “black-box” machine learning models. (3) Empirical Adequacy: Initial exploratory data analysis and the performance of the final model (R = 0.72) indicated that a linear model could capture the dominant trends with sufficient accuracy for the purpose of serving as the transfer function within the probabilistic framework, where the focus is on propagating the documented input variability.

While more complex machine learning models (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks) could potentially offer marginally higher predictive accuracy for point estimates, their ‘black-box’ nature complicates uncertainty propagation within the MCS framework and increases computational cost. The chosen linear regression model provides an optimal balance between performance, transparency, and practical utility for the probabilistic framework’s purpose.

The core innovation of this study was then implemented by integrating this deterministic model into a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) framework. This step involved characterizing the key input parameters as probability distributions derived from the observed field data variability. The MCS propagated these input uncertainties through thousands of iterations to generate a full probability distribution of PPV, thereby transforming a simple point-estimate model into a powerful probabilistic risk assessment tool.

The final, crucial step was the independent validation of this entire framework. The simulation results were rigorously tested against a completely independent set of 100 blast records from the left tunnel, which had been reserved exclusively for this purpose and was withheld from all prior model development and calibration stages. This comprehensive workflow effectively addresses the unique challenges posed by the cavity effect, providing a robust and validated tool for risk-informed decision-making in twin-tunnel projects.

To ensure the reproducibility of this study, the key computational steps and software tools are explicitly stated. The sensitivity analysis was performed using the Random Forest algorithm within the WEKA software (version 3.8.6) with an ensemble of 100 trees and 10-fold cross-validation. The multi-parameter linear regression model was developed using SPSS software (version 26). The Monte Carlo Simulation was implemented in @RISK software (version 8.2) integrated with Microsoft Excel, utilizing the distribution parameters specified in Title5.4 and a convergence criterion of 0.1% tolerance on the mean and standard deviation over 1000 consecutive iterations. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

4.2. Monte Carlo Simulation and Input Characterization

The cornerstone of the probabilistic framework is Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS), a technique selected for its proven efficacy in propagating input uncertainties through complex, non-linear models [9]. In the context of blast vibrations, where parameters like distance and charge weight are inherently variable and stochastic, MCS provides a robust methodology to move beyond deterministic point estimates [12,13,27].

The fundamental principle of MCS involves treating each input variable not as a fixed value, but as a Probability Density Function (PDF) that represents its observed variability and uncertainty based on field measurements [28,29]. The process entails executing the predictive model through thousands of iterations. In each iteration, a unique set of input values is randomly sampled from their respective PDFs. The collective output from these iterations forms a comprehensive probability distribution of the output variable—in this case, PPV—thereby enabling a probabilistic interpretation of the results essential for direct risk assessment and decision-making under uncertainty [30,31]. Crucially, MCS provides not only point estimates but also quantifies uncertainty by determining confidence intervals and exceedance probabilities [32]. This capability allows engineers to answer critical questions such as, “What is the probability that the PPV will exceed the regulatory limit of 10 mm/s for a given blast design?”—a question deterministic models cannot adequately address [4,25].

In this study, the MCS workflow was operationalized as follows: (1) The deterministic model was defined as the transfer function. (2) Each of its seven input parameters (Q, W, R, SD, Y, Z, CA) was characterized by a PDF, the parameters of which were derived exclusively from the 123 blast records in the calibration dataset. (3) For each iteration, a random value for each input variable was sampled independently from its respective PDF. This assumption of independence, while a simplification of the complex physical system, was deemed appropriate for this initial probabilistic model based on a comprehensive correlation analysis. The analysis between all input parameter pairs yielded Pearson correlation coefficients consistently below |0.7|, with the majority below |0.3|, indicating that strong multicollinearity was not present in the calibration dataset. While more complex dependency structures (e.g., copulas) could be explored in future work, their implementation was not warranted given the observed weak linear correlations. It is acknowledged that neglecting any residual non-linear dependencies might lead to a slight underestimation of the output variance; however, the strong validation performance against independent data (94% within the 90% CI) suggests that the model robustly captures the dominant uncertainty sources. (4) These independently sampled values were fed into equation to compute a single PPV output. (5) The collective output from thousands of such iterations formed the final probability distribution of PPV.

The selection of appropriate PDFs for each input parameter was a critical two-step process combining statistical rigor with engineering judgment. First, a statistical goodness-of-fit analysis (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) of the field data was conducted using @RISK software to identify candidate distributions. Second, physical plausibility and engineering judgment were applied to finalize the choices, ensuring the selected distributions were not only statistically sound but also physically meaningful [26,27]. Lognormal distributions were selected for distance (R) and cumulative advance (CA) as they accurately represent positive, skewed engineering data and prevent non-physical negative values [33,34,35,36]. A Triangular distribution was adopted for charge per delay (W) to encapsulate expert knowledge of the minimum (0.5 kg), most likely (~1.3 kg), and maximum (2.2 kg) values from field practice [2]. A Uniform distribution was used for the discrete Stage (S) parameter due to the lack of a natural ordinal weighting in its effect. The final selection between candidate distributions (e.g., Lognormal vs. Weibull) was based on achieving the lowest Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistic while upholding physical plausibility.

The MCS was implemented in @RISK software with a convergence criterion established to ensure statistical reliability. The simulation was configured to stop once the mean and standard deviation of the output PPV distribution stabilized within a 0.1% tolerance over 1000 consecutive iterations. This rigorous approach guarantees that the results accurately reflect both observed field variability and sound engineering principles [1,14]. The specific distribution parameters and convergence results are documented in Section 5.

The application of MCS in blast vibration analysis offers significant advantages. It explicitly accounts for input parameter variability, providing a full probabilistic output that significantly enhances risk-based decision-making [13]. This approach enables the direct calculation of exceedance probabilities for safety assessments and regulatory compliance, allowing for informed decisions on blast designs and safety measures [12]. Furthermore, MCS offers flexibility by allowing both empirical and mechanistic models to be integrated into its framework, enabling powerful hybrid methodologies [37]. The resulting output distributions can be effectively communicated to stakeholders through histograms, cumulative distribution functions, and risk curves, facilitating a better understanding of potential outcomes and supporting more effective risk communication [24].

Despite its advantages, MCS presents certain limitations. The computational demand can be substantial, especially for complex models with multiple interdependent parameters, as a large number of iterations may be required to achieve convergence [36]. The accuracy of MCS is highly sensitive to the choice of input PDFs, which must be based on sufficient and reliable data; inadequate data can lead to misleading results [28]. Additionally, MCS is primarily a numerical tool that does not inherently improve the underlying physical model—it only propagates uncertainty through existing models without adding new physical insights [3]. The method is also data-intensive, requiring a robust dataset for calibration and validation, which may not always be available in practice, particularly for new sites or unusual geological conditions [4]. These limitations underscore the importance of combining MCS with sound engineering judgment and comprehensive field data collection.

4.3. Study Area

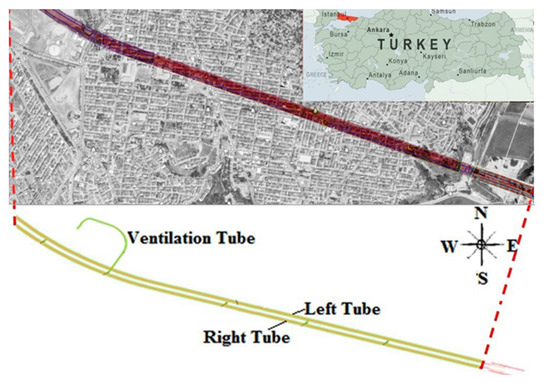

The field data for this study were collected from approximately 450 m of twin-tunnel excavation on the European side of Istanbul, as part of the Northern Marmara Highway project. Vibration monitoring focused specifically on 123 m of initial single-tunnel excavation (right tunnel) and the subsequent 320 m of twin-tunnel excavation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Satellite view showing the location of the Northern Marmara Highway twin-tunnel project on the European side of Istanbul, Turkey.

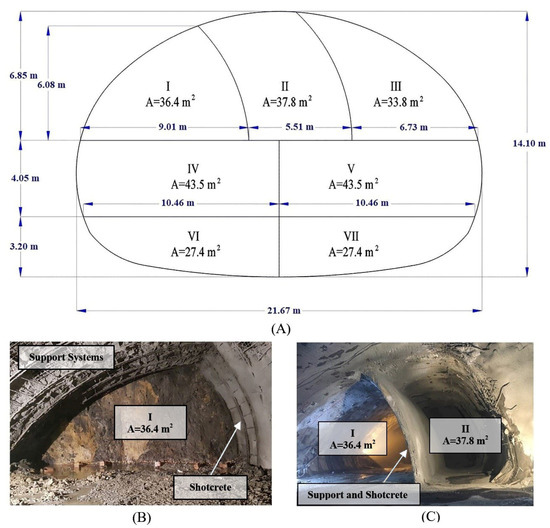

The tunnel face was strategically divided into seven distinct sections, excavated sequentially in an overlapping manner (Figure 3A). Excavation commenced with Section I, with subsequent sections initiated after the previous ones reached required advances. This phased approach aimed to gradually increase excavation space and aid tunnel stabilization. Each initiation point is a critical moment, and the time interval between two such moments is defined as a Phase (e.g., Phase I: Section I; Phase II: Sections I and II; up to Phase 7). Figure 3B,C provide photographic views of the initial excavation phases.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic diagram of the seven distinct sections and sequential excavation phases on the tunnel face. (B) Photograph of the initial excavation (Section I). (C) Photograph showing the progress after initiating Section II.

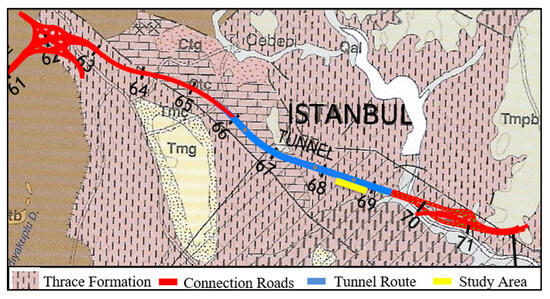

4.4. Geological and Geotechnical Setting

The geological context is characterized by the Thrace formation [38], primarily consisting of an alternation of sandstone, claystone, siltstone, and shale. The specific member encountered is the Cebeciköy limestone, comprising turbiditic sediments with colors ranging from dark yellowish coffee and greyish blue to blackish grey and black (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Geological map of the study area (modified from [38]).

The geotechnical properties are central to understanding the ground response. The Geological Strength Index (GSI) for this limestone is rated at 28, characterizing a rock mass of very poor quality according to widely accepted classifications (Table 1). This weak and heterogeneous nature, coupled with the inherent spatial variability of turbiditic sediments, introduces significant uncertainty into the system, which is reflected in the scatter of the vibration records.

Table 1.

Rock unit engineering parameters [38].

4.5. Field Data Collection and Experimental Program

The experimental program encompassed an extensive field monitoring campaign designed to capture blast-induced vibration characteristics throughout the tunnel excavation process. A total of 282 PPV recordings were collected from strategically positioned monitoring stations. This dataset includes 59 records from single right tunnel excavation, 123 records from the right tunnel during twin-tunnel excavation, and 100 records from the left tunnel reserved for model validation. Vibration measurements were personally conducted by the authors to ensure data quality and consistency.

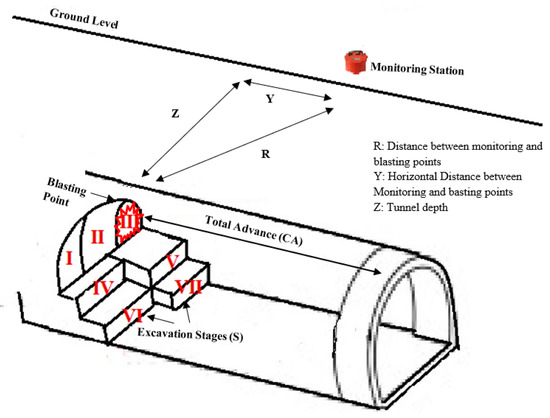

The spatial relationships between blasting sources and monitoring stations are crucial. As illustrated in Figure 5, vibration waves travel to the surface through the shortest path (parameter Z) and also propagate as surface waves along the horizontal distance (parameter Y). The blasting stages (parameter S) proved significant as they determine the direction and orientation of each shot relative to the monitoring stations.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of measurement parameters (conceptual illustration after Wang et al. [39]).

The core metric for vibration analysis was the triaxial Peak Particle Velocity (PPV), defined as the maximum vector sum of the three orthogonal components. While raw time-history data (encompassing both frequency and velocity records) were captured for each of the 123 blast events, PPV was extracted as the definitive parameter for model development, aligning with established engineering practice and regulatory standards. The blasting design itself was characterized by parameters with a direct physical influence on vibrations: the total charge (Q) and, more critically, the maximum charge per delay (W), which primarily governs vibration magnitude and duration. Each blast achieved an average advance of approximately three meters, and the cumulative advance (CA)—calculated by summing the advance from consecutive shots—was employed as a proxy for the evolving underground cavity dimensions. It is important to note that while CA quantifies the gross excavation volume, the analysis suggests that vibration propagation is more profoundly disrupted by the mere presence of the second tunnel cavity itself, highlighting the complex wave interaction phenomena central to this study. To support the modeling effort, the dominant frequency for each record was derived from the velocity time-history using the arithmetic mean method (as reported in Section 5.1), and the comprehensive descriptive statistics for all key parameters (PPV, Q, W, R, SD, Y, Z, CA) are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the collected field data.

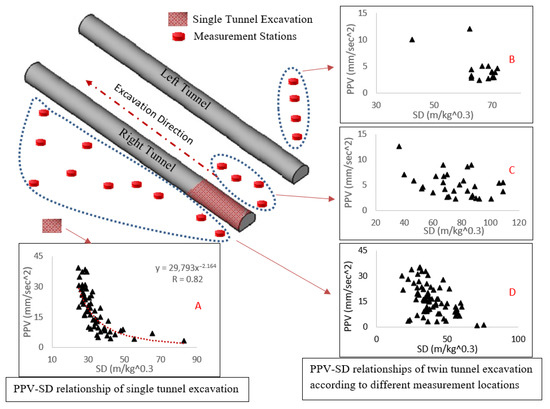

The strategic placement of vibration monitoring stations (Figure 6) allowed capture of varying vibration patterns relative to excavation progress and geometry. Stations were categorized into three groups based on position relative to the tunnels: ahead of the left tunnel, behind the right tunnel, and between the twin tunnels. This classification later proved essential for understanding spatial variations in the cavity effect.

Figure 6.

PPV-SD relationships for different monitoring station groups: (A) Single-tunnel excavation, (B) Stations ahead of left tunnel, (C) Stations behind right tunnel, (D) Stations between tunnels.

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation of Experimental Data and Cavity Effect

The PPV-SD correlation was robust (R = 0.82) during the single-tunnel excavation phase, confirming the validity of the empirical approach for simple geometries. However, the commencement of the left tunnel excavation fundamentally altered wave propagation, as evidenced by the significant deterioration of the PPV-SD correlation. This transformation underscores that the introduction of a second cavity disrupts site-specific attenuation characteristics, invalidating conventional empirical methods for twin-tunnel geometries.

The spatial distribution of vibration monitoring stations was analysed (Figure 6). Stations were categorized into three groups: ahead of the left tunnel, behind the right tunnel, and between the twin tunnels. Figure 6A confirms the strong PPV-SD relationship during single-tunnel excavation, while Figure 6B–D illustrate the deteriorated correlations observed in the three station groups during twin-tunnel excavation. This spatial variability—where some locations may experience amplification and others shadowing—is a direct manifestation of the complex wave interference patterns (constructive and destructive) described in Section 1, resulting from reflections and diffractions at the cavity interfaces. None of these groups maintained a significant PPV-SD relationship. Quantitatively, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the PPV-SD model dropped from 0.67 during single-tunnel excavation to less than 0.1 for all station groups during twin-tunnel excavation, underscoring the comprehensive impact of the cavity effect across all measurement locations. This evidence confirms that traditional empirical methods based solely on scaled distance become inadequate once a second tunnel cavity is introduced.

Beyond PPV magnitude, the frequency content provides additional insights. Average frequencies were calculated using the arithmetic mean method. During single-tunnel excavation in the right tunnel, the mean frequency was 76 Hz. During twin-tunnel excavation, mean frequencies decreased to 64.3 Hz in the right tunnel and 70.4 Hz in the left tunnel (Table 3). This reduction suggests that underground cavities have a damping effect on higher frequency components, potentially altering vibration characteristics relevant to structural response. From a regulatory perspective, all measured frequencies exceeded the 41 Hz breakpoint in DIN 4150 [40] for residential buildings, placing them in the higher frequency group where damage potential is generally reduced.

Table 3.

Mean frequencies of the twin tunnel.

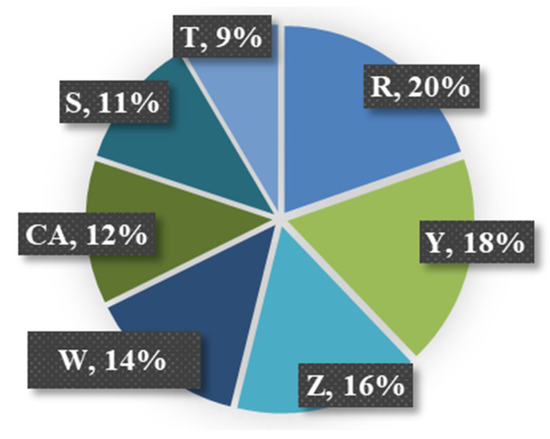

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis Using Random Forest Algorithm

Given the inadequacy of the PPV-SD approach, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the Random Forest algorithm in WEKA. An ensemble of 100 trees was used, a number sufficient for stable feature importance rankings, with robustness ensured via 10-fold cross-validation. Feature importance was calculated using the mean decrease in Gini impurity. The results (Figure 7) identified distance-related parameters (R, Z, Y) and charge per delay (W) as the primary drivers of PPV, which aligns with fundamental blasting principles. Critically, the Cumulative Advance (CA) emerged as a highly influential factor, quantitatively confirming that the evolving cavity geometry is a major controller of wave propagation, overshadowing the influence of total charge (T) and excavation stage (S).

Figure 7.

Random Forest sensitivity analysis results.

5.3. Statistical Estimation of Peak Particle Velocity

Building on the sensitivity analysis, statistical models for PPV estimation were developed. For single-tunnel excavation, the traditional PPV-SD relationship remained effective (Equation (1)):

For the complex twin-tunnel scenario, a multi-parameter linear regression analysis was performed using the 123 blast records from the right tunnel (during twin-tunnel excavation) with SPSS software. The resulting model is presented in Equation (2):

The coefficients of the multi-parameter model (Equation (2)) conform to physical intuition. The negative coefficients for geometric parameters (Y, Z) confirm the expected attenuation with distance. The positive coefficient for charge per delay (W) correctly reflects increased vibration energy. Most notably, the negative coefficients for stage (S) and cumulative advance (CA) provide quantitative evidence of a progressive damping effect linked to the evolving cavity geometry, directly substantiating the influence of the cavity effect on wave transmission.

The statistical performance of the developed regression models is summarized in Table 4. The single-tunnel model (Equation (1)) demonstrates a strong correlation (R = 0.82), accounting for approximately 67% of the variance in PPV. The multi-parameter twin-tunnel model (Equation (2)) achieves a good and statistically highly significant correlation (R = 0.72, R2 ≈ 0.52, p < 0.001), confirming its utility as a substantial improvement over a null model in a complex geological and geometric setting. It is critical to emphasize that the R2 value of 0.52 indicates that a significant portion of the variance remains unexplained by the model—a reflection of the inherent stochasticity of blast vibrations. This inherent uncertainty is precisely why this deterministic model is not proposed as a standalone predictive tool, but rather as a robust and computationally efficient engine for the subsequent probabilistic framework, which is designed to quantify this very uncertainty.

Table 4.

Statistical Performance of the Regression Analyses.

5.4. Probabilistic Risk Assessment Using Monte Carlo Simulation

While the deterministic model provides valuable insights, its point estimates cannot capture inherent uncertainties. To address this, the multi-parameter regression model (Equation (2)) was integrated into a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) framework implemented in @RISK software. This approach propagates input parameter uncertainties to generate a full probability distribution of PPV, enabling quantitative risk assessment.

The foundation of the MCS lies in the accurate representation of input parameter variability. Table 5 presents the probability density functions (PDFs) selected for each key parameter, derived from the 123 blast records through statistical goodness-of-fit tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and engineering judgment.

Table 5.

Input Distribution of MSC.

The MSC was executed with a convergence criterion of 0.1% tolerance on the mean and standard deviation over 1000 consecutive iterations. As summarized in Table 6, the simulation achieved convergence after 9738 iterations, providing results at a 95% confidence level.

Table 6.

Summary of Monte Carlo Simulation Execution.

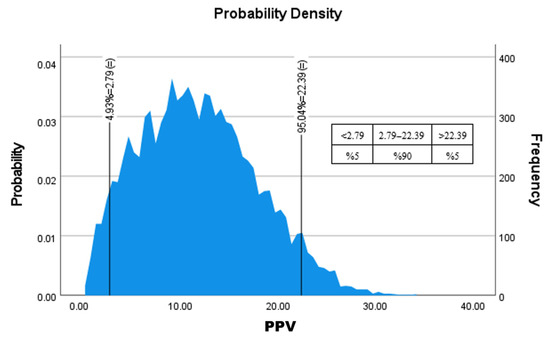

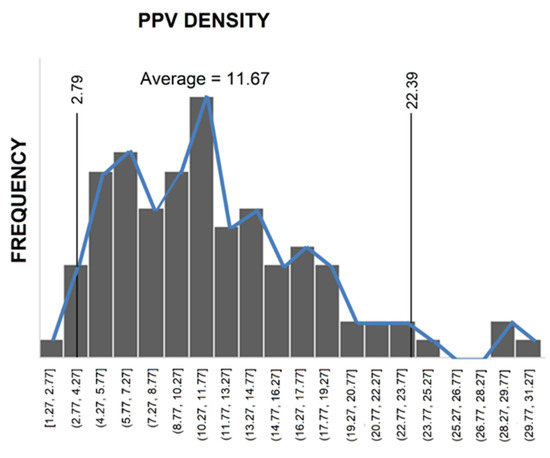

The primary output is the probability distribution of PPV (Figure 8). This distribution encapsulates the combined effect of all input uncertainties. The critical advantage is the ability to directly calculate exceedance probabilities. For the project’s regulatory safety threshold of 10 mm/s, analysis of the cumulative distribution function reveals:

Figure 8.

Probability density and cumulative distribution function of PPV obtained from the Monte Carlo Simulation (9738 iterations).

This quantitatively expresses the risk that any given blast may produce vibrations exceeding the safe limit—information inaccessible through deterministic methods.

To validate the MCS framework, its predictions were compared against the 100 independent blast records from the left tunnel. The frequency distribution of these actual PPV measurements is shown in Figure 9. A visual comparison shows strong agreement between the simulated and empirical distributions. For quantitative validation, the simulation’s 90% confidence interval was calculated, revealing that 94 out of 100 actual PPV values (94%) fell within the model’s 90% confidence interval, demonstrating excellent calibration where the model’s predicted uncertainty range reliably contains the observed outcomes. This high capture rate demonstrates that the MCS framework provides accurate point estimates and correctly characterizes the range of probable outcomes.

Figure 9.

Frequency distribution of validation PPV measurements from left tunnel.

6. Discussion

6.1. Empirical Validation of the Cavity Effect and Parameter Influence

The empirical data from this study provides unequivocal, quantitative evidence that the cavity effect fundamentally disrupts conventional vibration prediction models. The severe deterioration of the PPV-SD correlation—from a strong relationship (R = 0.82) during single-tunnel excavation to a non-significant one in the twin-tunnel phase—directly validates and quantifies the qualitative warnings and numerical findings of earlier researchers [1,2]. This result conclusively demonstrates that the scaled-distance law, predicated on the assumption of a homogeneous, continuous medium, becomes invalid in the presence of multiple, interacting cavities. The physical basis for this, as elucidated by foundational works [3,4], lies in the complex wave mechanics of energy partitioning—reflection, diffraction, and interference—at the stark impedance discontinuities represented by the tunnel cavities.

This study quantitatively validates this deterioration using 123 blast records. The strong correlation (R = 0.82) observed during single-tunnel excavation was significantly weakened upon the commencement of the second tunnel’s excavation. This finding underscores that the cavity effect is not merely a theoretical phenomenon but a fundamental engineering reality that invalidates practical prediction models. The physical basis for this, as explained in foundational works by Hao et al. [3] and Jiang & Zhou [4], lies in the complex wave mechanics of energy reflection, diffraction, and interference caused by the impedance discontinuity created by cavities.

The interpretation of correlation strength in this study follows established guidelines in geotechnical engineering and statistical practice. A correlation coefficient (R) value of 0.82, as observed during single-tunnel excavation, is widely regarded as indicating a strong positive relationship, signifying that the scaled-distance model explains a substantial portion (R2 = 0.67) of the variance in PPV. In contrast, the deterioration to non-significant and very low R values (R2 < 0.1) across all monitoring groups in the twin-tunnel phase represents a fundamental breakdown of this relationship. The multi-parameter model developed for the twin-tunnel scenario achieved an R value of 0.72, which is considered a good correlation in the context of complex, field-scale geotechnical data where numerous uncontrolled variables exist. This level of correlation indicates that the model captures the dominant trends effectively, making it a suitable and robust engine for the subsequent probabilistic framework, whose primary goal is to propagate the remaining, unexplained variance quantified by these statistics.

Existing literature, primarily through sophisticated numerical modeling, has effectively mapped the cavity effect’s manifestations, showing that cavities create a complex mosaic of energy redistribution with localized amplification and shadow zones [17]. This study builds upon this by linking these complex wave phenomena to practical, measurable engineering parameters. The Random Forest sensitivity analysis revealed that Cumulative Advance (CA) is a highly influential parameter. This implies that the gross, cumulative modification of the underground space—the total volume of excavated material—is a more significant controller of the global vibration field than the instantaneous blast design parameters for a given geometry. This finding provides an empirical basis for a “progressive decoupling” effect, wherein the expanding void network progressively alters the overall dynamic stiffness and wave transmission paths between the source and the surrounding rock mass. This data-driven insight into the system-level geometric control is a key contribution of this study.

6.2. Paradigm Shift: From Deterministic Prediction to Probabilistic Risk Assessment

This study explicitly challenges the prevailing deterministic paradigm in blast vibration prediction. While recent studies have advanced predictive accuracy through numerical modeling [22] or machine learning [9], they predominantly yield a single “most likely” PPV value. This approach condenses a stochastic phenomenon into a point estimate, discarding critical information about low-probability, high-consequence tail events paramount for risk management. In contrast, this framework formalizes a paradigm shift by acknowledging that the cavity effect reshapes the entire probability distribution of PPV, not just its mean. By embedding a site-calibrated model within a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS), we directly quantify this full distribution. This enables the calculation of exceedance probabilities (e.g., P (PPV > 10 mm/s) = 5.2%), representing a fundamental leap from deterministic prediction to quantifiable probabilistic risk assessment, aligning with the philosophy championed by pioneers like Harrison [11].

6.3. Engineering Implications and Practical Utility of the MCS Framework

The engineering utility of this research is realized through the practical application and robust validation of the probabilistic framework. The deterministic regression model (R = 0.72) serves as a necessary foundation, but its integration with MCS transforms it into a powerful tool for proactive risk management. Consider a scenario where the deterministic model predicts an ostensibly “safe” PPV of 6.5 mm/s. The MCS framework, however, can reveal a 5.2% probability of exceedance above the 10 mm/s regulatory limit. This exceedance probability can be directly interpreted as a Quantified Risk Factor (QRF). This QRF empowers engineers and project managers to move beyond simplistic binary (safe/unsafe) decisions and make informed judgments that balance operational efficiency with project-specific risk tolerance. For example, a project with sensitive adjacent structures might have a risk tolerance of <1%, requiring design modifications if the calculated QRF is 5.2%. A practical case from the Northern Marmara project illustrates this: A blast design was initially evaluated using the deterministic model, which predicted a ‘safe’ PPV of 6.5 mm/s. However, the MCS framework revealed a 5.2% probability of exceeding the 10 mm/s threshold. While this risk was deemed acceptable for the project’s general operational phase, when excavation approached a zone with older, potentially vulnerable surface structures, the project team proactively decided to implement mitigation measures (specifically, reducing the charge per delay, W) for the blasts in that zone. A subsequent MCS analysis with the reduced charge weight showed the exceedance probability dropped to 1.1%, which aligned with the temporarily adopted, stricter risk tolerance for that sensitive area. This demonstrates how the quantified probability directly informed and justified a targeted, cost-effective risk mitigation strategy. This shift from deterministic point-based judgment to probability-based decision-making represents a substantial advancement in engineering practice

The independence of this validation dataset was rigorously ensured; the 100 records from the left tunnel were physically and temporally separate from the 123 records from the right tunnel used for model calibration. Furthermore, this left tunnel data was explicitly withheld from all stages of model development, including the sensitivity analysis, regression, and MCS input characterization, guaranteeing a truly independent test. The validation of the MCS framework against these 100 independent blast records, showing a 94% capture rate within the 90% confidence interval, is where its superiority becomes undeniable. This result has a tripartite significance, as highlighted in the literature discussion: First, it proves Calibrated Uncertainty, confirming that the input probability distributions, selected through statistical and engineering judgment, accurately represent real-world variability. Second, it validates the Robust Model Form, demonstrating that the structure of the deterministic regression model correctly captures the dominant physical relationships in the system. Third, and most importantly, it delivers a Risk-Ready Output. An engineer can now state with quantified confidence that for a given blast design, there is a 90% chance the PPV will fall between specific values. This ability to provide a reliable and calibrated map of uncertainty is the cornerstone of modern geotechnical risk communication and decision-making.

Finally, while recent studies like Zhou et al. [22] and Wang et al. [26] have provided profound, physically-grounded damage criteria and evaluated mitigation strategies for twin tunnels, they also highlight the limitations of deterministic solutions, noting the non-uniform effectiveness of measures like damping trenches or the trade-offs in excavation sequence. The study’s probabilistic framework does not replace this need for physical understanding or mitigation design; rather, it complements it by providing the tool to quantify the residual risk after such measures are implemented. It allows engineers to answer the question: “How much does this mitigation strategy reduce the probability of exceedance?” This creates a direct pathway for optimizing and justifying risk control measures in a cost-effective manner.

In summary, this study’s principal innovation is the paradigm shift it enables: from deterministic prediction to quantifiable probabilistic risk assessment. The transition from a singular “most likely” PPV value to a full distribution and its associated exceedance probability (e.g., P (PPV > 10 mm/s) = 5.2%) represents a fundamental leap in actionable intelligence. This empowers engineers to move beyond binary safe/unsafe judgments, transforming their role from passive predictors to proactive risk managers who can optimize safety and efficiency based on quantitative risk. The proposed MCS-based methodology successfully bridges the gap between computationally intensive numerical models and oversimplified empirical approaches, offering a practical, powerful, and probabilistically rigorous tool for modern underground infrastructure projects.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While the proposed MCS framework represents a substantive advancement in blast vibration risk assessment, it is imperative to contextualize its findings within the study’s inherent limitations, which also delineate clear pathways for future research.

A primary limitation of this study is the site-specific nature of the calibrated deterministic model (Equation (2)). The model’s coefficients are intrinsically tied to the specific geological context (Thrace formation, very poor-quality rock with GSI ≈ 28) and the geometric configuration of the Northern Marmara Highway tunnels. Crucially, the model was developed and validated within the specific parameter ranges encountered in this project, as detailed in Table 2. For instance, the PPV values used for calibration ranged from 2.3 to 25.9 mm/s, charge per delay (W) varied between 0.5 and 2.2 kg, and monitoring distances (R) were between 26.8 and 105.9 m. The model’s performance is therefore statistically robust within these bounds, but its accuracy when extrapolating beyond this envelope—for example, to projects with significantly higher charge weights, much stronger rock masses, or vastly different tunnel spacings—is unverified and likely to deteriorate. Therefore, the direct transfer of Equation (2) to other projects is strongly discouraged. The primary, transferable contribution of this work is not the regression equation itself, but the universally applicable probabilistic workflow (Figure 4).

To adapt this framework to a new project with divergent geotechnical conditions, practitioners should follow the outlined workflow: (1) Collect a site-specific dataset of blasts and corresponding PPV measurements. (2) Perform a sensitivity analysis (e.g., using Random Forest) to identify the governing parameters for that specific site. (3) Develop a new, site-specific deterministic model (which could be a regression model as here, or another suitable form). (4) Characterize the input uncertainties for the new site based on the collected data. (5) Propagate these uncertainties through the new model via MCS to obtain a site-specific PPV probability distribution and exceedance probabilities.

A related limitation is the framework’s reliance on surrogate parameters (e.g., Cumulative Advance, Stage) to implicitly account for the complex cavity effect. While practical and data-driven, this approach does not explicitly incorporate fundamental dynamic rock properties, such as material damping ratios or in-situ P- and S-wave velocities, nor does it capture the detailed spatial wave interaction between the twin tunnels. This simplification enhances practical utility but may limit the model’s ability to extrapolate to geometries or rock masses vastly different from the calibration site. Future research should investigate the development of a hybrid framework that integrates a simplified physical or numerical wave propagation model within the MCS. Such an approach could offer a more generalizable balance between physical rigor and computational efficiency.

A significant shortfall of the current framework is its exclusive focus on predicting PPV magnitude. Modern blast damage criteria (e.g., DIN 4150 [40]) and structural response analyses are inherently dependent on both vibration amplitude and frequency content. This limitation impacts the framework’s utility for full regulatory compliance, as standards like DIN 4150 prescribe different velocity thresholds for different frequency bands. For instance, a PPV of 10 mm/s might be acceptable for high frequencies (>41 Hz) but unacceptable for lower frequencies that could induce resonance in common structures. As shown in Table 3, the measured frequencies in this study (64.3–76 Hz) were consistently high, falling well above the 41 Hz breakpoint in DIN 4150 [40] for residential buildings. This indicates that, for this specific project, the damage potential was likely low. However, the model’s inability to probabilistically predict frequency spectra for other sites where frequencies might be lower—and thus closer to the natural frequencies of structures—constitutes a notable limitation for comprehensive risk assessment. A model predicting only a “safe” PPV of 8 mm/s could be misleading if that vibration occurs at a damaging resonant frequency, a risk this current framework cannot quantify.

Furthermore, the probabilistic analysis is inherently constrained by the statistical properties of its input data. The probability distributions for the MCS inputs were derived from the 123 blast records of this single project. While statistically robust for this case study, this dataset may not encompass the full epistemic uncertainty and variability encountered across different global ground conditions and blasting practices. A pivotal future task is, therefore, the creation of a multi-project database for blast vibrations in twin tunnels. This would facilitate the development of more representative ‘prior distributions’ for Bayesian updating or for defining more globally applicable input variability ranges, significantly enhancing the framework’s generalizability.

The model’s inability to probabilistically predict frequency spectra constitutes a notable limitation for comprehensive risk assessment, as the potential for structural resonance remains unquantified. Therefore, a compelling and necessary trajectory for future research is the expansion of this framework into a multi-output, probabilistic predictor. As a direct extension of this work, it was planned to develop a complementary model for predicting dominant frequency (e.g., via separate regression or machine learning) and integrating it within the MCS to generate joint probability distributions of PPV and frequency. This would deliver a truly holistic risk assessment tool aligned with modern engineering standards.

In conclusion, these limitations do not undermine the value of the proposed framework but rather define the frontiers for its evolution. Addressing these points in future work will transition the methodology from a powerful site-specific tool to a universally robust paradigm for probabilistic risk management in underground construction.

6.5. Distinctive Innovation and Engineering Contribution

The principal innovation of this research transcends the mere application of MCS; it lies in the operationalization of a paradigm shift from deterministic prediction to quantifiable probabilistic risk assessment for blast vibrations in complex geometries. While previous studies have acknowledged the cavity effect and some have even employed advanced techniques for point prediction, they remain confined within a deterministic paradigm that obscures the inherent risk. This framework formally recognizes and quantifies that the cavity effect alters the entire probability distribution of potential PPV outcomes.

The transition from a singular, and potentially misleading, “most likely” value to a quantified exceedance probability (e.g., P (PPV > 10 mm/s) = 5.2%) represents a fundamental leap in the actionable intelligence available to engineers. This output is directly interpretable as risk. It enables a move from binary, safety-factor-based judgments to a nuanced, probability-informed decision-making process. For instance, a deterministic prediction of 6.5 mm/s might be deemed “safe,” while this framework can reveal a non-negligible 5.2% risk of exceedance, allowing project managers to weigh this risk against operational priorities and mitigation costs.

The ultimate engineering contribution is thus the transformation of the engineer’s role from a passive predictor, relying on oversimplified models, to a proactive risk manager, equipped with a practical, computationally efficient tool to quantify, communicate, and mitigate vibration risks in the complex reality of twin-tunnel excavations.

7. Conclusions

This study led to the following principal conclusions:

- Empirical Validation of the Cavity Effect: The classical PPV-SD relationship, which was reliable (R = 0.82) during single-tunnel excavation, deteriorated significantly upon the introduction of the second tunnel. This quantitatively confirms the profound impact of the cavity effect and establishes the inadequacy of conventional scaled-distance methods for twin-tunnel geometries.

- Governing Parameters: The Random Forest sensitivity analysis identified and ranked the key parameters governing PPV. While distance-related parameters and charge per delay were fundamentally important, the significant influence of Cumulative Advance (CA) quantitatively highlighted the critical role of the evolving underground cavity geometry.

- Deterministic Model Performance: A robust, multi-parameter linear regression model was developed, effectively capturing geometric and blast design parameters specific to twin-tunnels and achieving a statistically significant correlation (R = 0.72, p < 0.001).

- Paradigm Shift to Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The core innovation was the integration of the deterministic model within an MCS framework. This enabled a paradigm shift from point estimates to a full probability distribution of PPV, allowing for the direct calculation of exceedance probabilities (e.g., P (PPV > 10 mm/s) = 5.2%).

- Validation and Practical Utility: The framework was rigorously validated against an independent dataset, with 94% of observed PPV values falling within the 90% confidence interval. This provides engineers with a practical, computationally efficient tool for moving from binary safety judgments to quantitative, risk-informed decision-making, enabling the optimization of blast designs based on project-specific risk tolerance.

In conclusion, this study has successfully bridged a critical gap between deterministic blast vibration prediction and the pressing need for quantifiable risk assessment in complex twin-tunnel projects. By empirically validating the profound cavity effect, identifying key governing parameters, and pioneering a hybrid empirical-probabilistic framework, we have moved beyond simplistic point estimates to deliver a tool that quantifies the probability of exceeding regulatory thresholds. The robust validation against independent field data confirms the framework’s reliability and practical utility. This paradigm shift empowers engineers to transition from reactive compliance to proactive, risk-informed decision-making, ultimately enhancing both safety and operational efficiency in the construction of modern underground infrastructure. The proposed methodology not only addresses a significant challenge in tunneling engineering but also sets a new standard for integrating uncertainty quantification into daily engineering practice.

Author Contributions

A.K. and M.C.O. were integrally involved in all aspects of the research, including study conceptualization, methodological development, data acquisition and analysis, and manuscript preparation. U.K.S., U.O. and A.A. made significant contributions to the methodological framework and analytical approach. The field-based investigations were primarily conducted by A.K., M.C.O. and U.O., whereas U.K.S. and A.A. performed the statistical analyses and Monte Carlo Simulation. All authors contributed substantially to data interpretation, participated actively in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Executive Secretariat of Scientific Research Projects of Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa (Project No: 25573), the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkiye (TÜBİTAK Project No: 1059B192100471), and the Engineering Faculty Revolving Fund (Project No: 18.01.2018/24470).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa Engineering Faculty, Executive Secretariat of Scientific Research Projects of Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa and KRP Construction Company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shin, J.H.; Moon, H.G.; Chae, S.E. Effect of blast-induced vibration on existing tunnels in soft rocks. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2011, 26, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Ou, E. Effect of blast-induced vibration from new railway tunnel on existing adjacent railway tunnel in Xinjiang, China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 46, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Y. Numerical analysis of blast-induced stress waves in a rock mass with anisotropic continuum damage models part 1: Equivalent material property approach. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2002, 35, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zhou, C. Blasting vibration safety criterion for a tunnel liner structure. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2012, 32, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, C.H. Blast Vibration Monitoring and Control; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Siskind, D.E.; Stagg, M.S.; Kopp, J.W.; Dowding, C.H. Structure Response and Damage Produced by Ground Vibration from Surface Mine Blasting; RI 8507; US Bureau of Mines: Washington, DC, USA, 1980.

- Abate, G.; Massimino, M.R. Parametric analysis of the seismic response of coupled tunnel–soil–aboveground building systems by numerical modelling. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 15, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleska, T.; Beben, D.; Vaslestad, J.; Sukuvara, D.S. Application of EPS Geofoam below Soil–Steel Composite Bridge Subjected to Seismic Excitations. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2024, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Empirical prediction of blast-induced vibration on adjacent tunnels. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1212654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Oh, D.W.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, Y.J. Investigation of pile group response to adjacent twin tunnel excavation utilizing machine learning. Geomech. Eng. 2024, 38, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.L. Introduction to Monte Carlo simulation. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1204, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.N.; Blair, D.P. Mechanistic Monte Carlo models for analysis of flyrock risk. In Rock Fragmentation by Blasting; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 641–647. [Google Scholar]

- Armaghani, D.J.; Mahdiyar, A.; Hasanipanah, M.; Faradonbeh, R.S.; Khandelwal, M.; Amnieh, H.B. Risk assessment and prediction of flyrock distance by combined multiple regression analysis and Monte Carlo simulation of quarry blasting. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 3631–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Aghili, N.; Ghaleini, E.N.; Bui, D.T.; Tahir, M.M.; Koopialipoor, M.A. Monte Carlo simulation approach for effective assessment of flyrock based on intelligent system of neural network. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiyar, A.; Armaghani, D.J.; Koopialipoor, M.; Hedayat, A.; Abdullah, A.; Yahya, K. Practical risk assessment of ground vibrations resulting from blasting, using gene expression programming and Monte Carlo simulation techniques. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadabfar, M.; Huang, H.; Kordestani, H.; Muho, E.V. Probabilistic modeling of excavation-induced damage depth around rock-excavated tunnels. Results Eng. 2020, 5, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.A. Case study on the cavity effect of a water tunnel on the ground vibrations induced by excavating blasts. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 71, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, G.; Wu, L.; Zuo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Comparative study on tunnel blast-induced vibration for the underground cavern group. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; An, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, D.; Yan, L. Comparative study on calculation methods of blasting vibration velocity. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2011, 44, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Xia, C.; Li, G.; Jin, B.; He, Y.; Fu, Y. Safety threshold determination for blasting vibration of the lining in existing tunnels under adjacent tunnel blasting. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8303420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shan, R.L.; Wang, H.L. Research on vibration effect of tunnel blasting based on an improved Hilbert–Huang transform. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Liang, Y. Propagation characteristics and prediction of blast-induced vibration on closely spaced rock tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 123, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, J.; Khalid, M.I. Mitigation strategies for blasting-induced cracks and vibrations in twin-arch tunnel structures. Def. Technol. 2025, 49, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, N.; Sun, J.; Xia, Y.; Lyu, G. Influence of tunnel blasting construction on adjacent highway tunnel: A case study in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2019, 11, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Li, H.B.; Ma, G.W.; Zhou, Y.X. Assessment of underground tunnel stability to adjacent tunnel explosion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 35, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Luo, C. Response of existing lining subjected to closed blasting in zero-spacing twin tunnels and its damping measures. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 166, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.A.; Ficarazzo, F. Monte Carlo simulation as a tool to predict blasting fragmentation based on the Kuz–Ram model. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, E.; Sari, M.; Ataei, M. Development of an empirical model for predicting the effects of controllable blasting parameters on flyrock distance in surface mines. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012, 52, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Hao, H.; Li, X. Numerical analysis of the stability of abandoned cavities in bench blasting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 92, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Wu, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhou, Y. Characteristics of surface ground motions induced by blasts in jointed rock mass. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2001, 21, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; Yuan, Q. The effect of blast-induced vibration on the stability of underground water-sealed gas storage caverns. Geosystem Eng. 2018, 21, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, A.; Pearson, T.; Casarim, F. Guidance on Applying the Monte Carlo Approach; Winrock International: Little Rock, AR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Suliman, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B.; Xiong, F.; Elmageed, A.A. The difference in the slope supported system when excavating twin tunnels: Model test and numerical simulation. Geomech. Eng. 2022, 31, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Long, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, L. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of blast-induced vibration from adjacent tunnel on existing tunnel. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, H.B.; Li, J.C.; Liu, B.; Yu, C. A case study on rock damage prediction and control method for underground tunnels subjected to adjacent excavation blasting. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Matsagar, V. Dynamic analysis of a twin tunnel in soil subjected to internal blast loading. Indian Geotech. J. 2016, 46, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.B.; Moore, A.J. Flyrock Control—By Chance or Design. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference on Explosives and Blasting Technique, New Orleans, LO, USA, 1–4 February 2004. [Google Scholar]

- TTS Engineering. North Marmara Motorway—Cebeci Tunnel Geological and Geotechnical Report; TTS Engineering: Stockton-on-Tees, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Peng, K.; Xie, J. Impact of blasting parameters on vibration signal spectrum: Determination and statistical evidence. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 48, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 4150-3; Structural Vibrations—Part 3: Effects of Vibration on Structures. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).