Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Current Relevant Publications on Brayton Batteries

- Scalability: They are well-suited for energy storage on medium-to-large scales.

- Versatile energy output: These systems can deliver not only electrical power but also heating and cooling.

- Long service life and reduced material expenses: Their design avoids the use of rare or degradable materials, offering favorable long-term economic prospects.

1.2. Literature Review on Dynamic System Analyses of Brayton Batteries

1.3. Technology Overview of Heat Storage for Brayton Batteries

- Conclusion: Comparison and System Integration

- Novelty Statement

- A fully time-resolved system-level dynamic simulation of 15 Brayton battery architectures, including the transient evolution of regenerator-based TES;

- The assessment of hybrid system performance (electricity and heat and cooling) under realistic load changes, which is largely absent in existing LAES, CAES, and high-temperature thermal storage studies;

- A unified techno-economic comparison framework enabling direct benchmarking of Brayton batteries against other LDES technologies;

- The identification of operating regimes in which Brayton batteries achieve competitive round-trip utilization (RTU > 85%) despite lower peak electrical RTE, demonstrating system advantages in multi-energy applications.

2. Methods

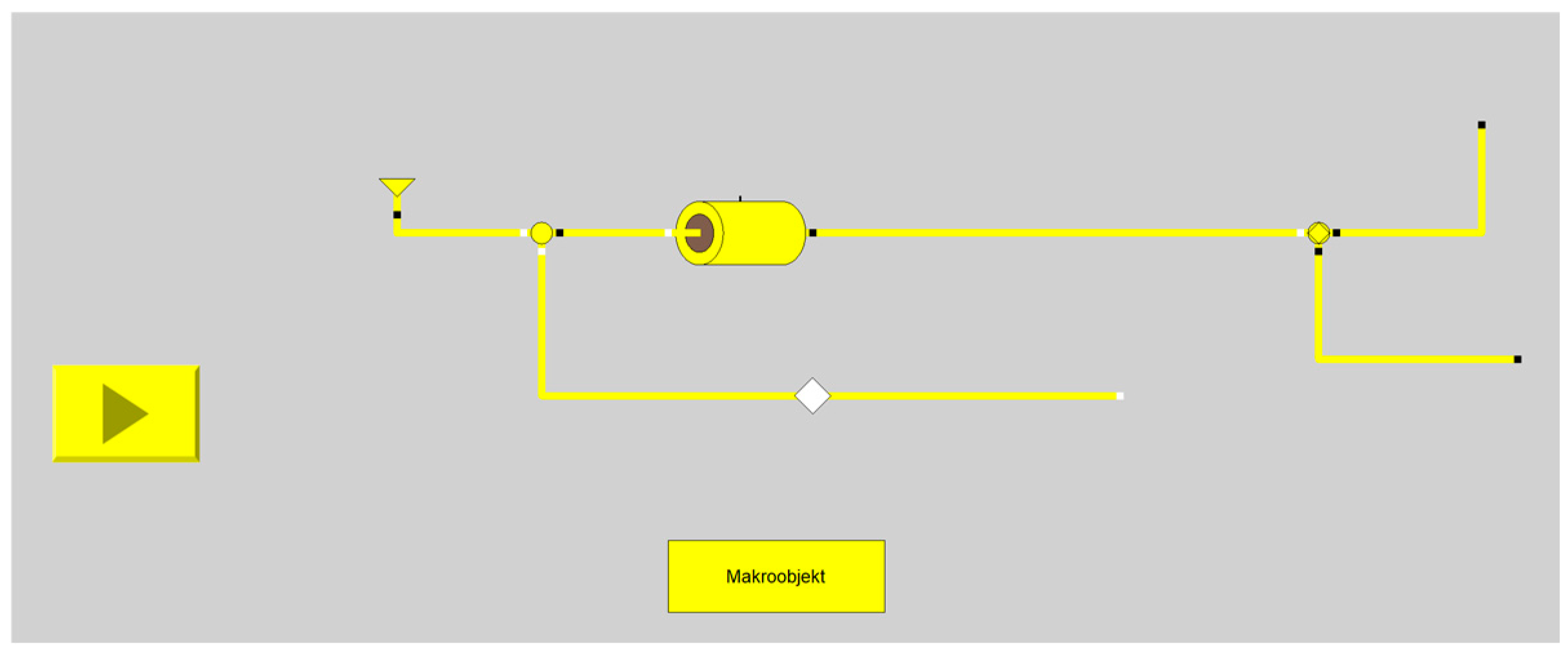

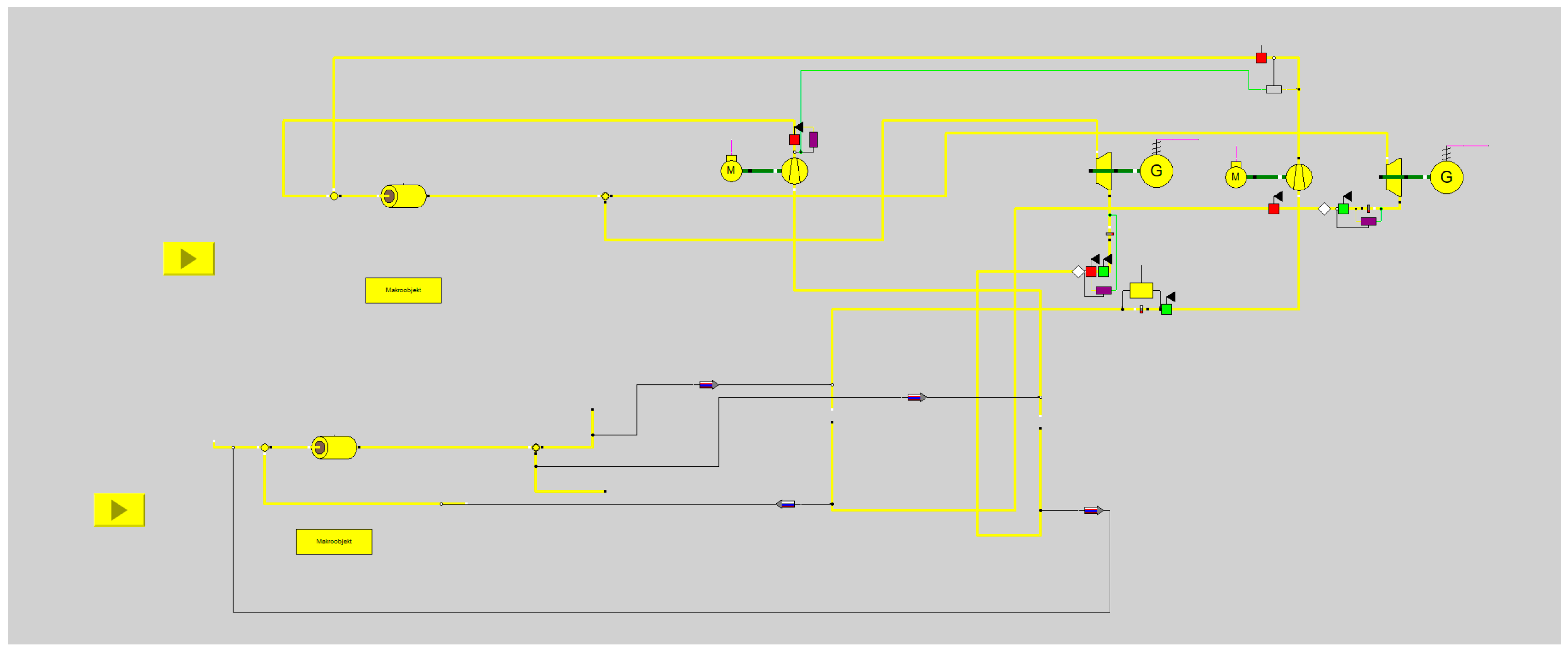

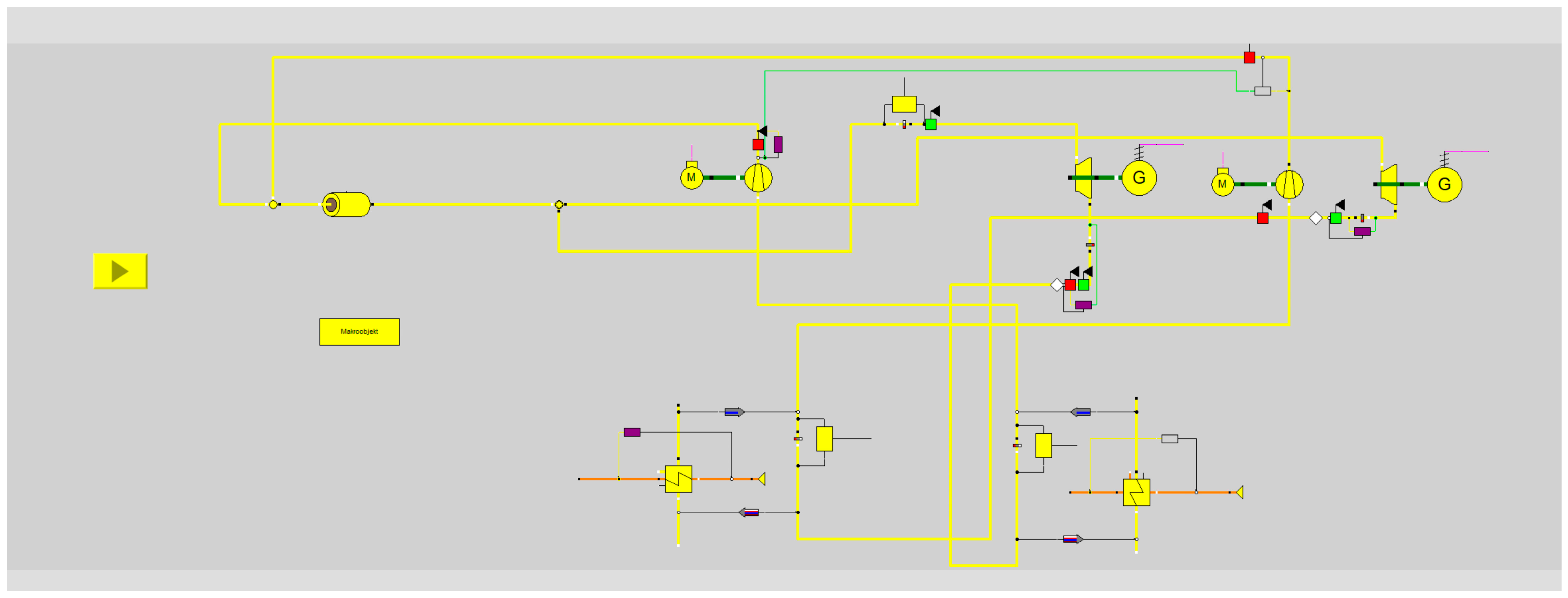

2.1. Modeling/Design of Components

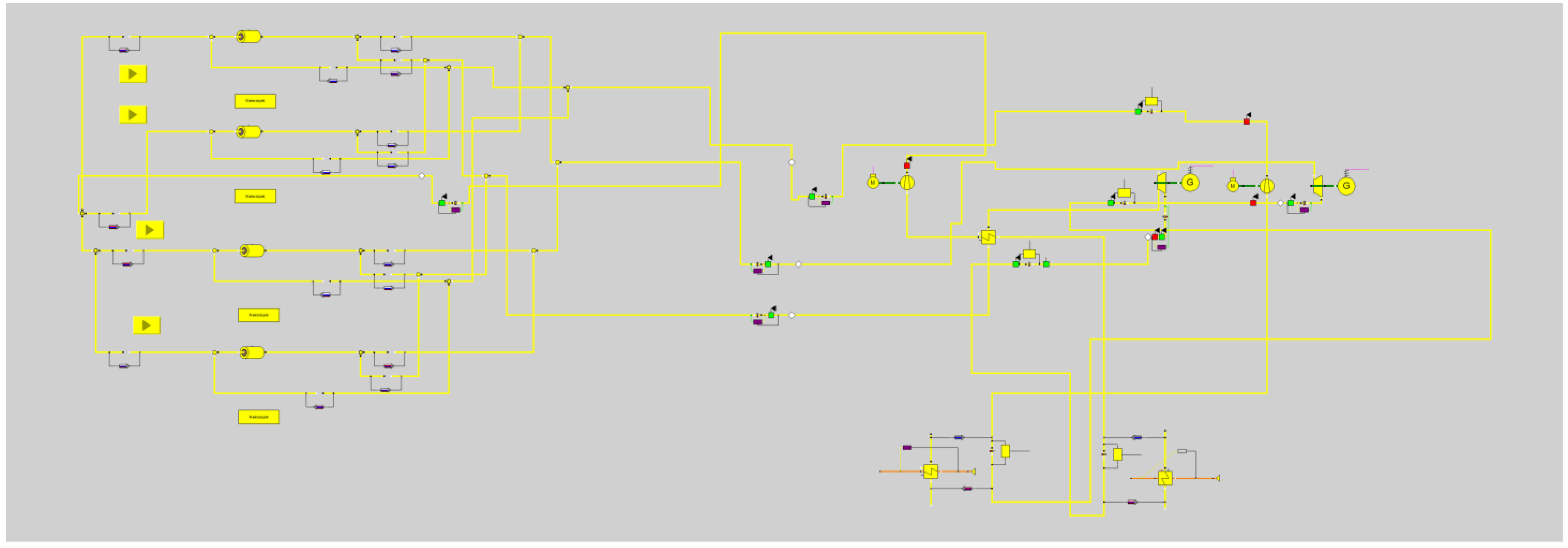

2.1.1. Numerical Methods

- Clarification of quasi-stationary vs. dynamic simulation:

2.1.2. Regenerator-Based TES Model

2.2. Modeling/Simulation of Complete Systems

- Regenerator-based TES: (pressurized) container, inventory, thermal insulation inside (if applicable) and outside, liner to protect the inner insulation of the container if applicable, foundation: DLR internal cost models.

- Heat storage based on liquids:

- Heat exchangers [41].

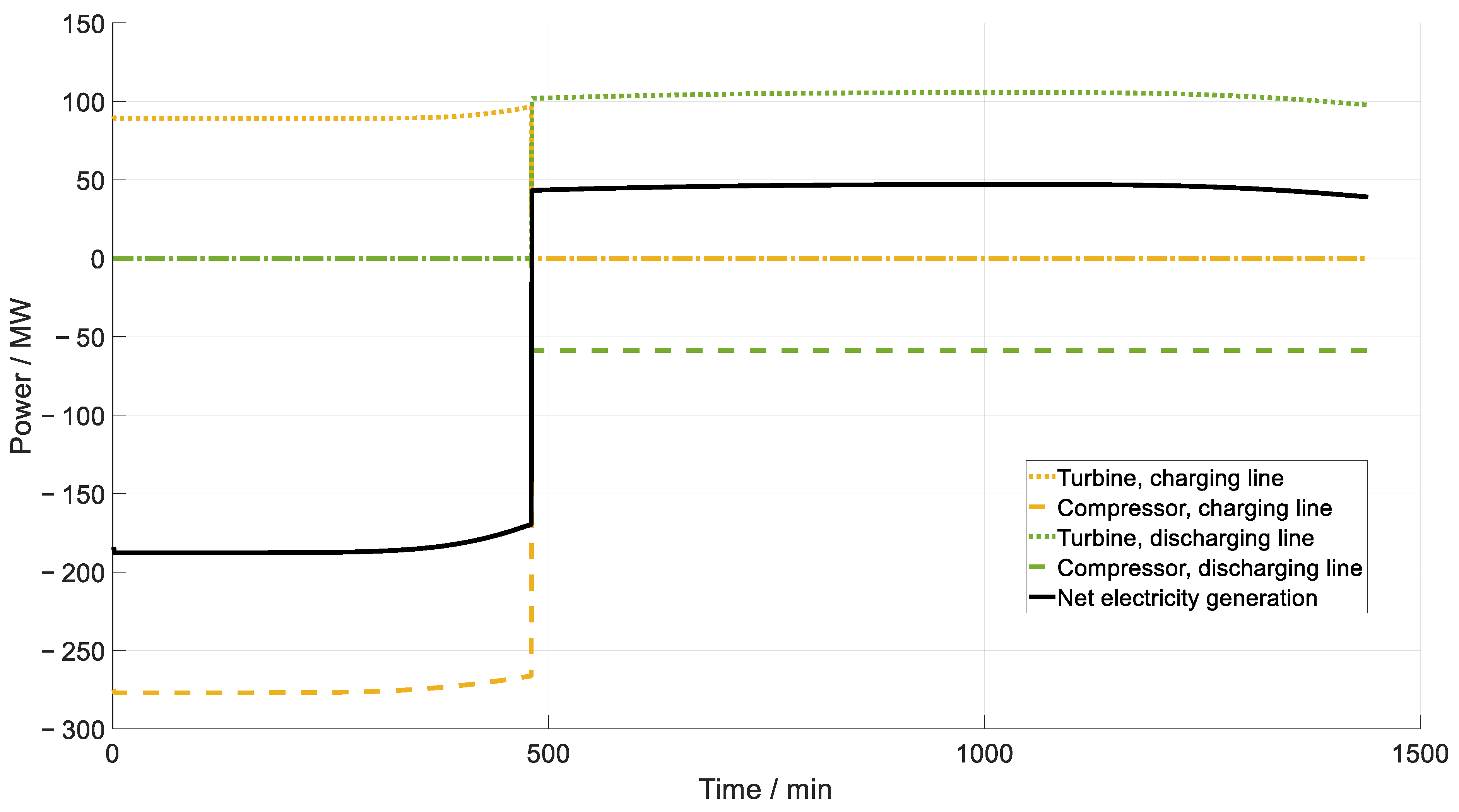

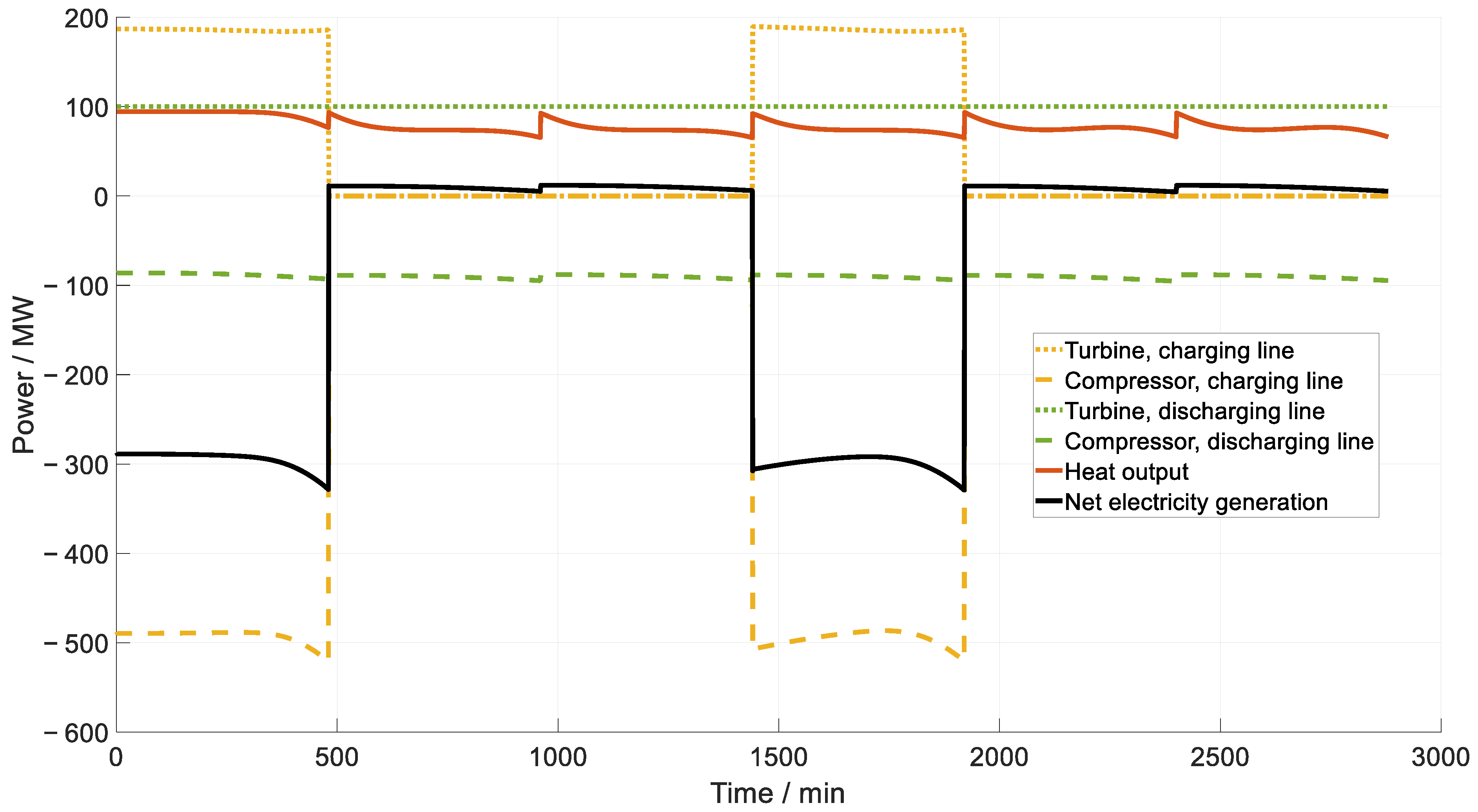

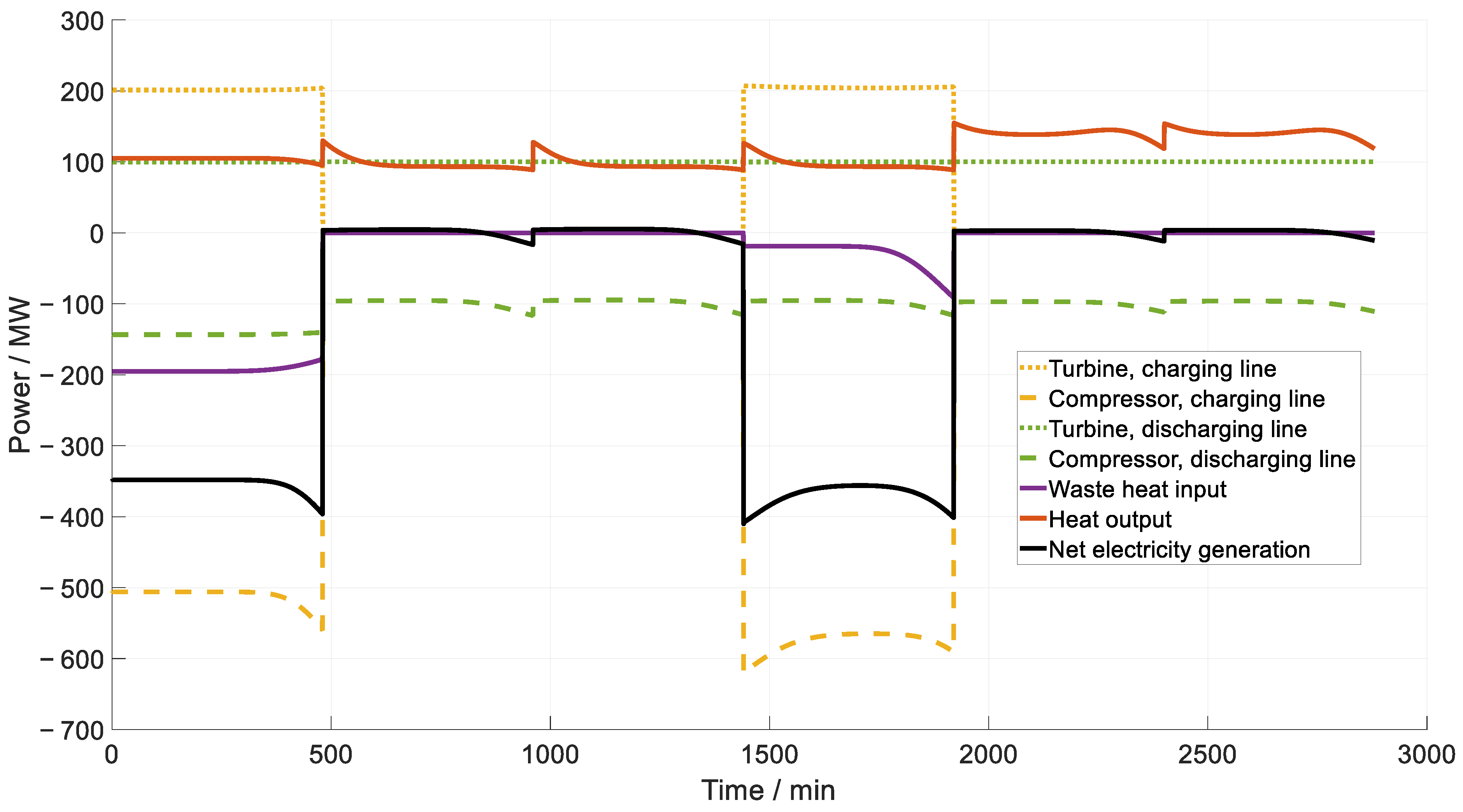

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Calculated Efficiencies with Literature Data

4.2. Dynamic Behavior and Transient System Characteristics

4.3. Evaluation of Thermal Energy Storage Technologies

4.4. System Architecture and Operating Strategies

4.5. Techno-Economic Assessment

4.6. Summary of Discussion

- Air-based systems achieve RTEs of up to 50%, with RTUs achieving over 85% in combined heat and power.

- RTU values of over 100% can be achieved by integrating waste heat.

- Regenerator-based TES systems are currently the most efficient and economical storage solution for Brayton batteries.

- The dynamic behavior is largely determined by temperature fronts in regenerator-based TESs.

- Economic competitiveness depends primarily on storage and turbine costs.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

- The calculated round-trip efficiencies (RTEs) reach up to 50% for concepts with pure electricity generation.

- For combined electricity and heat generation, round-trip utilizations (RTUs) of over 85% are achieved.

- With additional waste heat integration, RTU values of over 100% are possible—albeit at the expense of RTE.

- For combined electricity and cooling generation, RTUs of up to 60% are achieved with continued high RTEs of around 40%.

- The dynamic simulations show a stable control behavior with load gradients of up to 2 MW/min, which underlines the suitability for flexible energy and industrial applications.

- The investment cost estimate shows that the largest cost drivers are the heat storage (30–40%) and turbomachinery (20–30%), whereby the total system costs are in the range of other large-scale Carnot battery concepts.

5.2. Identified Optimization Potentials

- 1.

- Variable operating conditionsTo increase system flexibility, future analyses should include variable boundary conditions with different temperature and load profiles. A parameter study on sliding compressor outlet temperatures (COTs) can help to determine optimum operating windows and increase economic efficiency.

- 2.

- Configuration of the heat storage tanksAs outlined in Section 3, the permanent (24/7) provision of process heat requires either an additional storage system on the user side (outside the car-not-battery) or an alternating high/low-temperature storage system on the producer side to enable parallel charging and discharging operation. In this study, the second approach was chosen, which allows autonomous operation but requires eight thermal storage units. For cost reasons, the first variant—a central user storage system—could be more economical in the long term.

- 3.

- Bidirectional turbomachineryThe development of compressors and expanders that work in both directions could halve the amount of equipment required. In techno-economic terms, this would be evaluated against a potentially lower RTE.

- 4.

- Hybrid and multi-storage conceptsFuture developments should combine solid media and liquid storage to improve both thermal stability and economics.

- 5.

- System integration and control strategiesFurther optimization should include an integrated view of control, storage management, and process coupling. The modeling of sliding COT values in particular offers potential for a more realistic representation of dynamic operating conditions.

5.3. Outlook

- Experimental validation of the model assumptions and simulation results;

- Evaluation of hybrid storage architectures under real operating conditions;

- Integrated optimization of efficiency, control and economy;

- Overall ecological and systemic assessment of the use of the technology.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCP | Combined Cooling and Power |

| Ch | Charging |

| COT | Compressor Outlet Temperature |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| Dis | Discharging |

| HEX | Heat Exchanger |

| HT-TES | High-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage |

| ID | Identifier |

| LDES | Long-Duration Energy Storage |

| LT-TES | Low-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage |

| PEG | Pure Electricity Generation |

| Recu | Recuperator |

| Reg | Regenerator |

| RTE | Round-Trip Efficiency |

| RTU | Round-Trip Utilization |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| WHI | Waste Heat Integration |

References

- Krüger, M. Systematic Concept Study of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandersickel, A.; Ludwig, K. Carnot Battery Development—State of the art & prospects. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Carnot Batteries, Stuttgart, Germany, 24–26 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Li, Q.; Werle, S.; Wang, S.; Yu, H. Development and comprehensive thermo-economic analysis of a novel compressed CO2 energy storage system integrated with high-temperature thermal energy storage. Energy 2024, 303, 131941. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.; Song, J.; Ding, Y. Thermodynamic investigation of a Carnot battery based multi-energy system with cascaded latent thermal (heat and cold) energy stores. Energy 2024, 296, 131148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neises, T.; McTigue, J. Design-Point Techno-Economics of Brayton Cycle PTES for Combined Heat and Power. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2025, 147, 21008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, P.; Liu, B. Thermodynamic investigation of a Joule-Brayton cycle Carnot battery multi-energy system integrated with external thermal (heat and cold) sources. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124652. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi, S.S.M.; Barberis, S.; Maccarini, S.; Traverso, A. Thermo-economic performance evaluation of thermally integrated Carnot battery (TI-PTES) for freely available heat sources. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112979. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Du, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Sun, S. Performance analysis and multi-objective optimization of a combined system of Brayton cycle and compression energy storage based on supercritical carbon dioxide. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121837. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Shi, X.; He, Q. Thermodynamic analysis of novel carbon dioxide pumped-thermal energy storage system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 255, 123969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, Q. Thermodynamic analysis of pump thermal energy storage system with different working fluid coupled biomass power plant. Energy 2025, 318, 134758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, M.; Frate, G.F.; Ferrari, L. Capital cost reduction in thermomechanical energy storage: An analysis of similitude-based reversible Brayton systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsagri, A.S.; Rahbari, H.R.; Wang, L.; Arabkoohsar, A. Thermo-economic optimization of an innovative integration of thermal energy storage and supercritical CO2 cycle using artificial intelligence techniques. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 186, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, S.; Guedez, R. Techno-economic analysis of power-to-heat-to-power plants: Mapping optimal combinations of thermal energy storage and power cycles. Energy 2024, 312, 133500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.S.M.; Barberis, S.; Maccarini, S.; Traverso, A. Large scale energy storage systems based on carbon dioxide thermal cycles: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, K.; Bai, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y. Feasibility of transcritical pumped thermal energy storage system bottoming at ambient temperature. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 268, 126000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, J.I.; Arenas, E.; Montes, M.J.; Cantizano, A.; Pérez-Domínguez, J.R.; Porras, J. Direct coupling of pressurized gas receiver to a brayton supercritical CO2 power cycle in solar thermal power plants. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guan, H.; Shao, J.; Jin, X.; Su, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Sun, D.; Wei, T. Thermodynamic and advanced exergy analysis of a trans-critical CO2 energy storage system integrated with heat supply and solar energy. Energy 2024, 302, 131507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, J.; Hirschey, J.; Ma, Z. Advancing pumped thermal energy storage performance and cost using silica storage media. Appl. Energy 2025, 387, 125567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, B.; Jasim, D.J.; Anqi, A.E.; Aich, W.; Rajhi, W.; Marefati, M. Multi-criteria/comparative analysis and multi-objective optimization of a hybrid solar/geothermal source system integrated with a carnot battery. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 54, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shukla, A.K.; Singh, O.; Sharma, M. Exergoeconomic, thermodynamic and working fluid selection analysis of a novel combined Brayton cycle-regenerative organic Rankine cycle for solar application. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 26, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Han, W.; Liu, Q.; Jiao, F.; Ma, W. Proposal and analysis of an energy storage system integrated hydrogen energy storage and Carnot battery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, J.; Tran, A.P.; Stathopoulos, P. Simulation of a Safe Start-Up Maneuver for a Brayton Heat Pump. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 13–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinari, M.; Frate, G.F.; Tran, A.P.; Oehler, J.; Stathopoulos, P.; Ferrari, L. Transient analysis and control of a Brayton heat pump during start-up. In Proceedings of the ECOS 2023, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 25–30 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinari, M.; Frate, G.F.; Kyprianidis, K.; Ferrari, L. Dynamic modelling and part-load behavior of a Brayton heat pump. In Proceedings of the 64th International Conference of Scandinavian Simulation Society, SIMS 2023, Västerås, Sweden, 25–28 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Ge, Z.; Yang, L.; Du, X. Dynamic performance for discharging process of pumped thermal electricity storage with reversible Brayton cycle. Energy 2023, 263, 125930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, J.; Neises, T. Off-design operation and performance of pumped thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99 Pt A, 113355. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Ge, Z.; Yang, L.; Du, X. Dynamic characteristics and control strategy of pumped thermal electricity storage with reversible Brayton cycle. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sava, S. Joule-Brayton Pumped Thermal Electricity Storage Based on Packed Beds. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.J.; Zhao, C.Y. Transient behavior and thermodynamic analysis of Brayton-like pumped-thermal electricity storage based on packed-bed latent heat/cold stores. Appl. Energy 2023, 329, 120274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, X.; Chai, L.; Peng, L.; Yu, D.; Chen, H. Cyclic transient behavior of the Joule–Brayton based pumped heat electricity storage: Modeling and Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 111, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frate, G.F.; Baccioli, A.; Bernardini, L.; Ferrari, L. Assessment of the off-design performance of a solar thermally-integrated pumped-thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 2022, 201 Pt 1, 636–650. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Wu, C. Off-design performance evaluation of thermally integrated pumped thermal electricity storage systems with solar Energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frate, G.F.; Pettinari, M.; Di Pino Incognito, E.; Costanzi, R.; Ferrari, L. Dynamic Modelling of a Brayton PTES System. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 13–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gallego, D.; Gonzalez-Ayala, J.; Medina, A.; Calvo Hernández, A. Comprehensive review of dynamical simulation models of packed-bed systems for thermal energy storage applications in renewable power production. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolscht, L.; Knobloch, K.; Jacquemoud, E.; Jenny, P. Dynamic simulation and experimental validation of a 35 MW heat pump based on a transcritical CO2 cycle. Energy 2024, 294, 130897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, P.; Cai, X.; Du, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Li, R. Dynamic thermodynamic performance analysis of a novel pumped thermal electricity storage (N-PTES) system coupled with liquid Piston. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Shi, X.; He, Q.; Liu, Y.; An, X.; Cui, S.; Du, D. Dynamic modeling and numerical investigation of novel pumped thermal electricity storage system during startup process. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykas, P.; Bellos, E.; Kitsopoulou, A.; Tzivanidis, C. Dynamic analysis of a solar-biomass-driven multigeneration system based on s-CO2 Brayton cycle. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 59, 1268–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, M.; Krüger, M. SolarPACES Guideline for Bankable STE Yield Assessment: Appendix E—Thermal Energy Storage; SolarPACES: Almería, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dreissigacker, V.; Müller-Steinhagen, H.; Zunft, S. Thermo-mechanical analysis of packed beds for large-scale storage of high temperature heat. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 46, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.S.; Timmerhaus, K.D.; West, R.E. Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Towler, G.; Sinnott, R. Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Engineering Economics and Economic Design for Process Engineers; Taylor & Francis Group, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turton, R.; Bailie, R.C.; Whiting, W.B.; Shaeiwitz, J.A. Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes; Prentice Hall PTR: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, W.; Giuliano, S.; Koll, G.; May, M.; Bauer, T.; Belik, S.; Bohnes, S.; Dersch, J.; Dreißigacker, V.; Geyer, M.; et al. StoreToPower—Phase 1: Stromspeicherung in Hochtemperatur-Wärmespeicherkraftwerken. 2022. Available online: https://elib.dlr.de/186474/1/TIBKAT_1799875180.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

| Option | ID | Cooler/ Heater | Essential Data | Thermal Energy Storage (TES) | Compressor/ Expander | Recu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure electricity generation (PEG) | PEG1 | CbC_Dis | Air ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 49.5% | HT-TES: Reg (2.6 bar; 601–155 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Oil (1 bar; 82–409 °C) | Ch: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 2.74 Dis: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.58 | - |

| PEG2 | CbT_Ch | Air; ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 42.9% | HT-TES: Reg (2.6 bar; 431–85 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Oil (1 bar; −23–269 °C) | Ch: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 3.15 Dis: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.61 | - | |

| Coupled generation of electricity and heat (CHP) | CHP1 | CbT_Dis | Air ϑmax = 450 °C П = 8.1 RTU = 86.8% RTE = 10.3% Q/Wel = 7.45 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (8.1 bar; 433–121 °C) LT-TES: Reg (1 bar; −82–39 °C) | Ch: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 2.87 Dis: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.88 | Fixed head tube bundle |

| CHP2 | CaC_Dis | Air ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.0 RTU = 81.2% RTE = 19.0% Q/Wel = 3.27 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (2.0 bar; 607–279 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Salt (1 bar; 205–460 °C) | Ch: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 2.12 Dis: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.87 | - | |

| Coupled generation of electricity and heat with waste heat integration (CHP+WHI) | CHP+WHI1 | HbT_Ch + CbT_Dis | Air ϑmax = 625 °C П = 12.3 RTU = 103.1% RTE = 0.9% Q/Wel = 119.32 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (12.3 bar; 602–175 °C) LT-TES: Reg (1 bar; −78–11 °C) | Ch: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 3.26 Dis: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.99 | Fixed head tube bundle |

| CHP+WHI2 | HaLTTES_Ch + CbT_Dis | Air ϑmax = 450 °C П = 6.1 RTU = 94.2% RTE = 2.5% Q/Wel = 36.73 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (6.1 bar; 435–155 °C) LT-TES: Reg (1 bar; −38–62 °C) | Ch: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 2.56 Dis: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.97 | Fixed head tube bundle | |

| CHP+WHI3 | HaT_Ch + CaC_Dis + CaT_Dis | Air ϑmax = 625 °C П = 5.5 RTU = 84.6% RTE = 19.4% Q/Wel = 3.37 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (5.5 bar; 607–279 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Oil (1 bar; 89–251 °C) | Ch: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 2.19 Dis: Turbo compressor, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.86 | Fixed head tube bundle | |

| Coupled generation of electricity and cooling (CCP) | CCP1 | CbT_Ch + HaT_Ch | Air ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.8 RTU = 53.2% RTE = 42.4% Q/Wel = 0.20 (Ch.) | HT-TES: Reg (2.8 bar; 601–154 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Oil (1 bar; 18–394 °C) | Ch: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 3.92 Dis: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.58 | - |

| CCP2 | CbT_Ch + HbC_Dis | Air ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.7 RTU = 51.7% RTE = 38.3% Q/Wel = 0.34 (Dis.) | HT-TES: Reg (2.7 bar; 433–289 °C) LT-TES: Reg o. Oil (1 bar; −22–273 °C) | Ch: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 3.15 Dis: Turbo blower, air turbine; PC/PT = 0.65 | - |

| Phase | Hour | HT-TES1 | HT-TES2 | HT-TES3 | HT-TES4 | LT-TES1 | LT-TES2 | LT-TES3 | LT-TES4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charging | 1.–8. | Charging | Charging | Charging | Discharging | Discharging | Discharging | Discharging | Charging |

| Discharging | 9.–16. | Discharging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill | Charging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill |

| 17.–24. | Standstill | Discharging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill | Charging | Standstill | Standstill | |

| Charging | 25.–32. | Charging | Charging | Discharging | Charging | Discharging | Discharging | Charging | Discharging |

| Discharging | 33.–40. | Discharging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill | Charging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill |

| 41.–48. | Standstill | Discharging | Standstill | Standstill | Standstill | Charging | Standstill | Standstill |

| ID | Essential Data | Thermal Energy Storage (TES) | Compressor/ Expander | Recu | Cooler/ Heater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

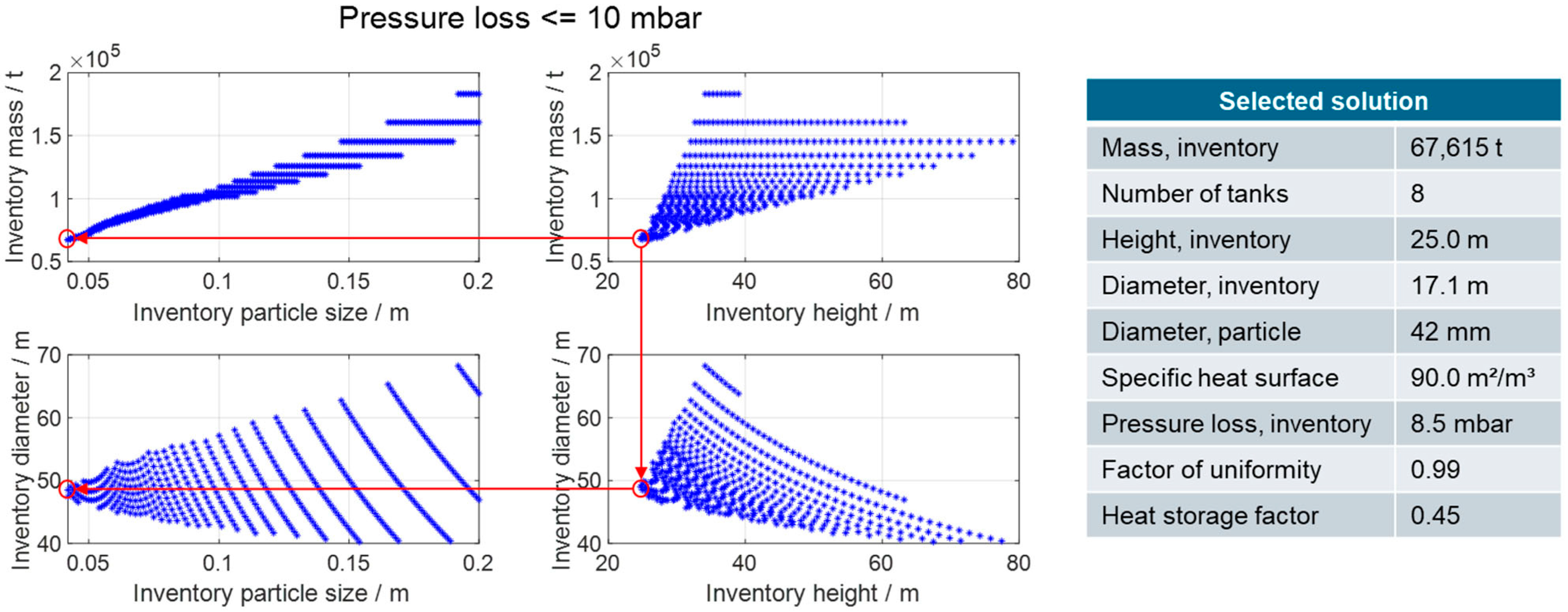

| PEG1—Reg | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 50.0% Charging: = 1073.4 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 536.7 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 155 °C, = 67,615 t, = 42 mm, 8 tanks (H = 25 m, D = 17.1 m), η = 45% LT-TES: ϑmax = 427 °C, ϑmin = 63 °C, = 81,442 t, = 81 mm, 7 tanks (H = 27 m, D = 18.1 m), η = 36% | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 265 MWel); air turbine (PN = 98 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbC_Dis (AHEX = 91,301 m2) |

| PEG1—Oil | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 50.0% Charging: = 1073.4 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 536.7 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 155 °C, s = 67,615 t, = 42 mm, 8 tanks (H = 25 m, D = 17.1 m), η = 45% LT-TES: ϑmax = 427 °C, ϑmin = 63 °C, = 20,033 t, = 22,259 m3, 12 tanks (each cold and hot, H = 21.1 m, D = 10.6 m), AHEX = 696113 m2 | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 265 MWel); air turbine (PN = 98 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbC_Dis (AHEX = 91,301 m2) |

| PEG2—Reg | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 47.1% Charging: = 1318.2 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 659.1 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 65 °C, = 79,101 t, = 41 mm, 8 tanks (H = 27.2 m, D = 17.8 m), η = 46% LT-TES: ϑmax = 285 °C, ϑmin = −40 °C, = 94,089 t, = 75 mm, 7 tanks (H = 27.8 m, D = 18.1 m), η = 38% | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN= 264 MWel); air turbine (PN = 98 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 1,265,181 m2) |

| PEG2—Oil | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.6 RTE = 44.5% Charging: = 1318.2 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 659.1 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 65 °C, = 79,101 t, = 41 mm, 8 tanks (H = 27.2 m, D = 17.8 m), η = 46% LT-TES: ϑmax = 285 °C, ϑmin = −40 °C, = 22,523 t, = 25,024 m3, 13 tanks (each cold and hot, H = 21.4 m, D = 10.7 m), AHEX = 839,975 m2 | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 264 MWel); air turbine (PN = 98 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 1,265,181 m2) |

| ID | Essential Data | Thermal Energy Storage (TES) | Compressor/ Expander | Recu | Cooler/ Heater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHP1 | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 8.1 RTU = 85.6% RTE = 6.4% Charging: = 1408.3 kg/s, = 469.4 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 469.4 kg/s | HT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 104 °C, = 27,546 t, = 39 mm, 3 tanks (H = 24.6 m, D = 18 m), η = 48% LT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 46 °C, ϑmin = −82 °C, = 46,408 t, = 160 mm, 3 tanks (H = 39,7 m, D = 18,4 m), η = 27% | Charging line: Turbo compressor (PN= 516 MWel); air turbine (PN = 182 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo compressor (PN = 88 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | Fixed head tube bundle (AHEX= 92,702 m2) | CbT_Dis (AHEX = 18,904 m2) |

| CHP2—Reg | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.0 RTU = 61.2% RTE = 13.0% Charging: = 2087.5 kg/s, = 695.8 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 695.8 kg/s | HT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 260 °C, = 49,480 t, = 48 mm, 6 tanks (H = 22.1 m, D = 18 m), η = 41% LT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 474 °C, ϑmin = 190 °C, = 52,438 t, = 27 mm, 6 tanks (H = 23.1 m, D = 18.1 m), η = 38% | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 397 MWel); air turbine (PN = 190 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 87 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CaC_Dis (AHEX = 12,266 m2) |

| CHP2—Salt | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.0 RTU = 83.2% RTE = 9.8% Charging: = 2087.5 kg/s, = 695.8 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 695.8 kg/s | HT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 260 °C, = 49,480 t, = 48 mm, 6 tanks (H=22.1 m, D=18 m), η = 41% LT-TES: ϑmax = 474 °C, ϑmin = 190 °C, = 54,534 t, = 31,341 m3, 16 tanks (each cold and hot, H = 21.5 m, D = 10.8 m), AHEX = 608,966 m2 | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 397 MWel); air turbine (PN = 190 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 87 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CaC_Dis (AHEX = 12,266 m2) |

| ID | Essential Data | Thermal Energy Storage (TES) | Compressor/ Expander | Recu | Cooler/ Heater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHP+WHI1 | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 12.3 RTU = 106.9% RTE = 1.4% Charging: = 1239.0 kg/s, = 413.0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 413.0 kg/s | HT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 150 °C, = 22,868 t, = 28 mm, 4 tanks (H = 17.2 m, D = 17 m), η = 52% LT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 16 °C, ϑmin = −83 °C, = 26,653 t, = 41 mm, 4 tanks (H = 18 m, D = 17.9 m), η = 42% | Charging line: Turbo compressor (PN = 644 MWel); air turbine (PN = 201 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo compressor (PN = 99 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | Fixed head tube bundle (AHEX = 82,287 m2) | HbT_Ch (AHEX = 144,178 m2) + CbT_Dis (AHEX = 23,538 m2) |

| CHP+WHI2 | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 6.1 RTU = 94.4% RTE = 0.8% Charging: = 1570.0 kg/s, = 523.3 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 523.3 kg/s | HT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 139 °C, = 28,172 t, = 28 mm, 4 tanks (H = 18.5 m, D = 18.2 m), η = 52% LT-TES (4x): ϑmax = 68 °C, ϑmin = −44 °C, = 58,223 t, = 40 mm, 4 tanks (H = 23.7 m, D = 17.5 m), η = 24% | Charging line: Turbo compressor (PN = 519 MWel); air turbine (PN = 205 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo compressor (PN = 97 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | Fixed head tube bundle (AHEX = 103,621 m2) | HaLTTES_Ch (AHEX = 61,281 m2) + CbT_Dis (AHEX = 21,228 m2) |

| ID | Essential Data | Thermal Energy Storage (TES) | Compressor/ Expander | Recu | Cooler/ Heater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCP1—Reg | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.8 RTU = 57.7% RTE = 46.9% Charging: = 501.9 kg/s, = 0 kg/s, Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 501.9 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 128 °C, = 52,625 t, = 65 mm, 5 tanks (H = 29 m, D = 17.8 m), η = 41% LT-TES: ϑmax = 414 °C, ϑmin = −4 °C, = 54,917 t, = 68 mm, 7 tanks (H = 22.9 m, D = 17.2 m), η = 38% | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 132 MWel); air turbine (PN = 34 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN= 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 144,658 m2) + HaT_Ch (AHEX = 13,456 m2) |

| CCP1—Oil | ϑmax = 625 °C П = 2.8 RTU = 55.8% RTE = 44.9% Charging: = 501.9 kg/s, = 0 kg/s, Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 501.9 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 625 °C, ϑmin = 128 °C, = 52,625 t, = 65 mm, 5 tanks (H = 29 m, D = 17.8 m), η = 41% LT-TES: ϑmax = 414 °C, ϑmin = −4 °C, = 13043 t, = 14,491 m3, 8 tanks (each cold and hot, H = 21 m, D = 10.5 m), AHEX = 432,998 m2 | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 132 MWel); air turbine (PN = 34 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 58 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 144,658 m2) + HaT_Ch (AHEX = 13,456 m2) |

| CCP2—Reg | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.7 RTU = 60.7% RTE = 39.6% Charging: = 674.5 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 674.5 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 88 °C, = 63,420 t, = 52 mm, 7 tanks (H = 24.5 m, D = 17.9 m), η = 45% LT-TES: ϑmax = 289 °C, ϑmin = −38 °C, = 73,543 t, = 71 mm, 8 tanks (H = 25.3 m, D = 17.8 m), η = 37% | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 132 MWel); air turbine (PN = 43 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN= 65 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 123,245 m2) + HbC_Dis (AHEX = 11,188 m2) |

| CCP2—Oil | ϑmax = 450 °C П = 2.7 RTU = 54.2% RTE = 40.0% Charging: = 674.5 kg/s, = 0 kg/s Discharging: = 0 kg/s, = 674.5 kg/s | HT-TES: ϑmax = 450 °C, ϑmin = 88 °C, = 63,420 t, = 52 mm, 7 tanks (H = 24.5 m, D = 17.9 m), η = 45% LT-TES: ϑmax = 289 °C, ϑmin = −38 °C, = 17226 t, = 19,139 m3, 10 tanks (each cold and hot, H = 21.4 m, D = 10.7 m), AHEX = 576,587 m2 | Charging line: Turbo blower (PN = 132 MWel); air turbine (PN = 43 MWel) Discharging line: Turbo blower (PN = 65 MWel); air turbine (PN = 101 MWel) | - | CbT_Ch (AHEX = 123,245 m2) + HbC_Dis (AHEX = 11,188 m2) |

| Lead Concept ID | Estimated Investment Costs in EUR Million | Capacity-Related Investment Costs in EUR/kWhel | Power-Related Investment Costs in EUR/kWel | Exemplary Distribution in % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-TES | LT-TES * | Compressor | Turbines | HEX * | ||||

| PEG1—Reg | 175–317 | 241–436 | 3853–6975 | 31 | 30 | 26 | 10 | 4 |

| PEG1—Oil | 213–355 | 302–503 | 4827–8051 | 26 | 39 | 23 | 9 | 3 |

| PEG2—Reg | 198–263 | 274–363 | 4385–5810 | 32 | 33 | 16 | 9 | 9 |

| PEG2—Oil | 246–311 | 383–484 | 6133–7737 | 27 | 44 | 14 | 8 | 8 |

| CHP1 | 351–619 | 2289–4037 | 36,624–64,597 | 28 | 34 | 29 | 7 | 2 |

| CHP2—Reg | 436–704 | 1674–2703 | 26,787–43,255 | 38 | 34 | 21 | 6 | 0 |

| CHP2—Salt | 481–749 | 2818–4387 | 45,080–70,185 | 35 | 39 | 20 | 6 | 0 |

| CHP+WHI1 | 380–832 | 8273–18,116 | 132,369–289,850 | 27 | 19 | 44 | 6 | 4 |

| CHP+WHI2 | 416–627 | 18,158–27,396 | 290,534–438,340 | 26 | 41 | 23 | 7 | 3 |

| CCP1—Reg | 136–206 | 194–294 | 3111–4700 | 33 | 30 | 19 | 10 | 8 |

| CCP1—Oil | 154–223 | 219–319 | 3510–5098 | 29 | 36 | 18 | 9 | 8 |

| CCP2—Reg | 157–194 | 264–326 | 4220–5221 | 34 | 37 | 13 | 9 | 7 |

| CCP2—Oil | 180–217 | 302–365 | 4840–5841 | 30 | 44 | 11 | 8 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krüger, M. Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12636. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312636

Krüger M. Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12636. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312636

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrüger, Michael. 2025. "Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12636. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312636

APA StyleKrüger, M. (2025). Investigation of the Dynamic Behavior of Brayton Batteries for Coupled Generation of Electricity, Heat, and Cooling. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12636. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312636