Abstract

The paper focuses on a transition from studying synthetic analogs of rare titanosilicate minerals (lintisite, ivanyukite, and zorite) in the powdery state to investigating their new granulated forms. Five different methods for granulating titanosilicate samples are tested: fluidized bed and spray dry granulation, spray bed granulation, screw rotor granulation, and manual pressing of paste through a stainless-steel sieve with a 1 mm mesh size. The results of studying sorption of trace amounts of 137Cs and 90Sr radionuclides from model solutions of various compositions onto inorganic sorbents in powdered and granulated forms are presented.

Keywords:

titanosilicate; sorbent; hydrothermal synthesis; granulation; radionuclides; cesium; strontium 1. Introduction

The valuable properties of synthetic titanosilicate materials have been verified experimentally in many publications [,,,,,,,,].

Inorganic sorbent materials belonging to various classes are currently increasingly used in applied radiochemistry (in particular, in selective extraction of cesium and strontium radionuclides from solutions with complex salt compositions) due to their distinct physicochemical characteristics, including high sorption capacity, selectivity for specific elements, and enhanced chemical, thermal, and radiochemical stability [,]. Among these, titanates and zirconosilicates are of particular interest owing to their specific crystalline or semi-crystalline architectures ensuring high selectivity for Cs+ and Sr2+ radionuclides even in solutions with complex compositions. These compounds therefore remain stable under harsh chemical and radiation conditions, which makes them indispensable for purification of radioactive solutions.

In recent years, synthetic analogs of rare natural minerals, such as titanium-, niobium-, and zirconium-silicates, have garnered significant interest for use in radiochemical technologies. The greatest diversity of these compounds is associated with alkaline complexes of the Kola Peninsula [,,]. These unique geological formations in northwestern Russia host numerous transition-metal silicate minerals that serve as prototypes for synthetic analogs.

Owing to the combination of zeolite-like properties [,,,] and high resistance to chemical, thermal, and radiation effects, such sorbents are highly promising for the selective extraction and long-term immobilization of radionuclides in various technological processes [].

However, not all new materials are currently obtained in a granulated form (for example, SIV, AM-4) [,,]. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to synthesize such sorbents in sufficient quantities, to test various methods for converting them into a granular form, and to identify the most optimal approach for their future granulation.

Bentonite or Al2Si2O7-metakaolin is often added as an inorganic binder at various ratios, from 20 to 40 wt.%, to improve the mechanical stability of zeolite granules []. The mechanical stability of granules is linearly increased as binder content is raised from 20 to 40 wt.%. Nevertheless, many publications note that a binder often reduces the adsorption capacity of materials and can worsen the maximum absorption of divalent cations by as much as 35% []. Furthermore, in a number of research papers and patents [,,,,,,], granulation was conducted at an elevated calcination temperature of 873 K [], often involving several stages [,], which may have complicated the technological process of granule preparation. Granulation usually yields core–shell structures with mechanical properties suitable for industrial use. However, such aggregates may have a lower water absorption capacity because of the cementing material []. Binders that have already been applied for sorbent granulation with a primitive extruder (pressure, 2–6 kg/m2) at our laboratory, without employing specialized equipment, were liquid glass and the solution remaining after synthesizing the sorbent with the chemical composition (mg/L): TiO2, 4; SiO2, 20.6; Na, 108; NH4, 6.8; SO2−, 32 [].

Earlier, our colleagues from the I.V. Tananaev Institute of Chemistry have already attempted to use the SIV sample for briquetting without additional pressure applied. Adhesion of SIV particles occurs when the synthesized sample (wet paste) is dried and additionally washed with distilled water []. Nevertheless, the research had to be continued to find conditions for obtaining granules that would exhibit stronger mechanical properties, while maintaining the sorbent’s sorption capacity with respect to several cations of alkali, heavy and nonferrous metals.

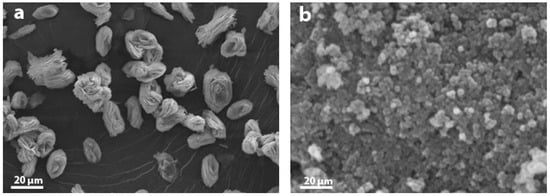

In contrast to the SIV powdered sorbent (Figure 1b), the AM-4 sorbent sample (Figure 1a) is not briquetted without applying additional pressure. This sample turns into a powder again after drying.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the initial powders of AM-4 (a) and SIV (b) titanosilicates sorbents.

For this reason, we started searching for a binder that would meet the requirements posed to potential binders, including the following conditions for practical application of titanosilicates:

- -

- the binder should be insoluble in dilute aqueous solutions (wastewater model solution), alkaline (LRW or Liquid Radioactive Waste) and acidic solutions (electrolyte solutions of copper–nickel production, pH < 1);

- -

- the binder component should not adsorb or incorporate elements extracted using a sorbent, especially in the case of using the sorbent for LRW treatment;

- -

- the binder, in the case of LRW cleaning, should be removed from the granules when the spent sorbent is sintered into the strong titanate-like ceramics (temperature, 600 °C);

- -

- the binder component should be non-toxic (including the stage of its further removal from the granules during calcination) and environmentally friendly; and

- -

- the binder should ensure that the content of the working substance (sorbent) in the granule is maximal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Their Abbreviations

AM-4: the full name for this material is Aveiro-Manchester-4. It is the microporous titanosilicate with the general formula Na3(Na,H)Ti2O2[Si2O6]2·H2O [].

STA is a product with the general formula (NH4)2TiO(SO4)2∙H2O. It is a product of titanite ore treatment using the sulfuric acid methodology (JSC Apatit, PhosAgro company, and Kola Science Center, Russia) [].

STM is titanyl sulfate (TiOSO4∙H2O), one of the semi-products of titanite ore treatment using the sulfuric acid methodology (mining JSC Apatit, PhosAgro company, and Kola Science Center, Russia) [].

SL3 is a synthetic titanosilicate whose crystal structure consists of Ti2Si4O10(OH)4 nano-blocks being extremely resistant to destruction.

ETS-4 is a synthetic titanosilicate, an analog of zorite mineral Na9Si12Ti5O38(OH)∙12H2O [,].

IONSIV IE 911 is a synthetic sorbent with the sitinakite-like crystal structure Na3Ti4Si2O13(OH)∙2H2O [,].

SIV: the full name for this material is synthetic ivanyukite. It is a synthetic analog of the mineral ivanyukite-Na with the general formula Na4(TiO)4(SiO4)3∙nH2O [].

SN is a synthetic analog of the mineral natisite, Na2TiSiO5 [].

TiSi-BS is semi-crystalline sodium silicothitanate synthesized at the Institute of Sorption and Problems of Endoecology (ISPE), National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, (Kyiv, Ukraine), a prototype (the reference sample from the collection of sorbents stored at the Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, RAS).

FNS-10 is ferrocyanide sorbent of FNS-10 grade based on potassium nickel ferrocyanide, applied onto silica gel using the sorption method, TU 2641-003-51255813-2007 (manufactured at the Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, RAS).

Thermoxide-35 is a spherical granulated inorganic sorbent based on nickel ferricyanide and zirconium hydroxide, TU 6200-305-12342266-98, manufactured by research and production company “Thermoxide” (Zarechny, Sverdlovsk Region, Russia).

KY-2 × 8 is a strongly acidic sulfocation cationite.

KL is natural clinoptilolite of the Shivertui deposit (Chita Region, Russia).

MDM is a sorbent based on modified manganese dioxide (TU 2641-001-51255813-2007);

NaA is synthetic zeolite, grade A, TU 2163-003-15285215-2006 produced at the Ishimbay Specialized Chemical Plant of Catalysts (Republic of Bashkortostan, Russia).

SRM-Sr is a sorption-reagent material based on barium silicate synthesized at the Institute of Chemistry, Far East Division, Russian Academy of Sciences (Vladivostok, Russia).

CR-20 is chlorinated rubber (Attika company, St. Petersburg, Russia).

2.2. Reagents

The chemicals (reagent or analytical grade) were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification (Merck, Aldrich and Neva reactive). The main sources of titanium for material synthesis were powders of titanyl sulfate (NH4)2TiO(SO4)2∙H2O (STA); TiOSO4∙H2O (STM) was a product of titanite ore treatment (mining JSC Apatit, PhosAgro company (Apatity city, Russia) and Kola Science Center, Russia).

The following reagents were utilized for granulation: (a) chlorinated rubber CR-20 (Attika company, St. Petersburg, Russia) with xylene solution used as a solvent for chlorinated rubber (fluidized bed granulation); (b) distilled water only (spray bed granulation); (c) 40% liquid glass solution (fluidized bed granulation and screw granulation); (d) mother liquor remaining after titanosilicate synthesis (fluidized bed granulation and screw granulation), and (e) cellulose spherical carriers for fluidized bed granulation.

2.3. Research Methods

The chemical compositions of synthetic powders and granules were identified, and their morphology was studied using a LEO-1450 scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with X-ray energy dispersive system AZtec with detector ULTIM Max 100 (Oxford Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK) (20 kV, 500–1000 pA; beam diameter, 1–3 μm) (Geological Institute, Kola Science Center, RAS). The study was carried out using unpolished samples.

The element contents in study solutions were analyzed using an ELAN 9000 DRC-e mass spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA manufacturer, INEP Institute, Kola Science Center, RAS).

An ED224S-RCE first-class accuracy analytical balance (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) was used for weighing titanosilicate powders. All the filters were weighed separately before filtration, after drying the sample with the filter, and after separating the sample from the filter in all experiments.

The synthetic phases, titanosilicate sample pellets, and their transformation products were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction on a MiniFlex II diffractometer (CuKα radiation, 30 kV/10 mA) (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan, Kola Science Center, RAS). The experiments were carried out in the 2Θ range of 5–65° with a scan step of 0.02° for 1 s/step.

For investigating the morphology of titanosilicate aggregates during transformation after granulation, their surface properties were compared. The BET surface properties and the porosity of the final products were characterized by nitrogen and adsorption/desorption method at 77 K using a TriStar 3020 surface area analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA, I.V. Tananaev Institute of Chemistry, Kola Science Center, RAS). The average pore diameter (Dav) was calculated to be 4 V/S. Prior to adsorption/desorption measurements, the sample was degassed at 393 K for ~24 h.

An MX-50 moisture analyzer (A&D, Tokyo, Japan, Kola Science Center, RAS) was used to study the moisture content in the titanosilicate aggregates.

The specific activity of 137Cs and 90Sr radionuclides in solutions was measured using a multipurpose α-β-γ SKS-50M spectrometer (Green Star Technologies, Moscow, Russia).

The γ-channel was equipped with a CsI scintillation detector having the following parameters: energy resolution, 8 keV; efficiency, 0.08 counts per quantum; measurement error ≤ 10%. The measurement geometry consisted of a glass beaker 60 mm in diameter and 20 mm high. The β-channel was equipped with a BDEB-70 scintillation detector (energy range, 50–3500 keV; energy resolution, 15 keV; measurement error, ≤10%). The measurement geometry was presented by a stainless-steel cup 50 mm in diameter and 3 mm high.

2.4. Preparing Titanium Sources for Synthesizing Titanosilicates

Salts were mainly produced at the Sorbent pilot plant (Kola Science Center, RAS) using 20–25 L autoclaves. The equipment was intended exclusively for sphene concentrate stripping and production of titanium-bearing salts STA and STM. The equipment for Ti-precursor synthesis was used in periodic mode with mechanical loading and unloading of apparatuses. Figure 2 shows the photographs of the reactors used for sorbent synthesis in the processing room.

Figure 2.

Photographs of synthesis reactors in the processing room: (a) a system of reactors for concentrate decomposition and STA salt preparation; (b) a 25 L reactor for hydrothermal synthesis.

Sphene concentrate (provided by JSC Apatit) was the main source of titanium for obtaining precursor salts. The total chemical composition of the concentrate was as follows (wt.%): TiO2, 32.8; SiO2, 28.8; CaO, 25.6; Al2O3, 1.86; P2O5, 0.71; Fe2O3, 1.66; and Nb2O5, 0.59.

Salts produced at the plant using acid stripping solutions of sphene concentrate (salts STA (NH4)2TiO(SO4)2∙H2O and STM TiOSO4∙H2O) were utilized for synthesizing titanosilicate products.

2.5. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Titanosilicates Samples

A SNOL high-precision universal drying furnace (SNOL-TERM Ltd., Tver, Russia, Kola Science Center, RAS) operating in the temperature range from +50 °C to +300 °C, equipped with a programmable thermostat, was used for heating laboratory autoclaves. The 7 L autoclave was heated automatically by a special heating system.

Autoclaves with the volumes of 40 cm3 (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA; in-house production, Kola Science Center, RAS), 100 cm3 (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA, Kola Science Center, RAS), and 450 cm3 (in-house production, Kola Science Center, Russia) and 7 L (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA, Kola Science Center, RAS) were used for hydrothermal synthesis of titanosilicate phases and synthesis scaling. The 7 L autoclave was used for hydrothermal synthesis of ivanyukite only. The synthesized powders were separated from the mother liquor by vacuum filtration using a diaphragm pump (Technology for Vacuum system, Vacuubrand, Germany, Kola Science Center, RAS).

2.6. Granulation of Titanosilicate Powders

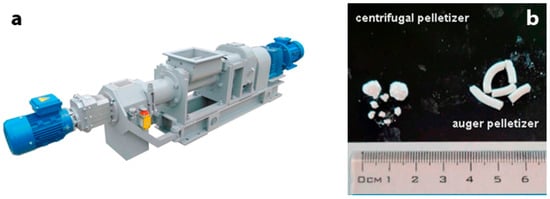

A Mini Glatt fluidized bed unit (Glatt GmbH, D. Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology, Moscow, Russia) was used for testing granulation, drying and coating, processes occurring in the bottom and top spray methods, and flexible retrofitting if needed. A TL-20 centrifugal granulator (Dzerzhinsk, Kola Science Center of RAS, Russia) was utilized for granulating the samples without special polymer binders. An FSH-003RK02 auger pelletizer (Kola Science Center of RAS, Russia) was used to produce cylindrical pellets.

2.7. Granulation Procedures

2.7.1. Fluidized Bed Granulation

The samples were subjected to additional grinding prior to granulation. The presence of an additional pore-forming agent or paste-forming additive was not taken into account. The binder was prepared by dissolving CR-20 chlorinated rubber in xylene. The solution was mixed using a magnetic stirrer until dissolution of chlorinated rubber. Experimental studies were carried out on a Mini Glatt fluidized bed unit (Glatt GmbH, Binzen, Germany). Each sample (ETS-4, AM-4 and SIV) weighed 50 g. Binder concentration in the solvent was 50%. Binder proportion in the final product was 10%.

2.7.2. Spray Bed Granulation

The samples were subjected to additional grinding prior to granulation. The presence of an additional pore-forming agent or paste-forming additive was not taken into account.

The weight of the titanosilicate samples was 300 g. The sample was pre-wetted with a small portion of distilled water (50 mL), 10–40% liquid glass solution or residual mother liquor to prevent dust formation. After this step, the powdered sample was immersed into a special chamber of the centrifugal granulator. Centrifugation was carried out at a chamber rotation speed of 2500 rpm. The resulting AM-4 titanosilicate granules were dried at ambient temperature for 5 h and then dried again at 60 °C for 4 h.

2.7.3. Granulation Using an Auger Pelletizer

The samples were subjected to additional grinding prior to granulation. The presence of an additional pore-forming agent or paste-forming additive was not taken into account. The weight of the titanosilicate samples was 100–250 g. The sample was pre-wetted with a small portion of distilled water (50 mL), 10–40% liquid glass solution or residual mother liquor to prevent dust formation. After this step, the powdered sample was immersed into a special chamber of the auger granulator. Centrifugation was conducted at a rotational speed of 350 rpm. The resulting titanosilicate granules were dried in a SNOL furnace at 60–75 °C for 2 h (SNOL-TERM, Kola Science Center, RAS).

2.7.4. Mechanical Crush Strength of Pellets and Moisture Content in the Samples

The mechanical crush strength of the pellets (the ultimate fixed load) was determined at the St. Petersburg Mining University using a Mark-10 device in compliance with the ASTM D6175 method and using a KRAEMER Hardness Tester HC6.2 (KRAEMER, Zuchwil, Switzerland, Kola Science Center, RAS).

Moisture contents in the samples (powders and granules) were determined using an AND MX-50 weight moisture meter (Japan, Tokyo, FRC Kola Science Center, Russia).

2.8. Testing Granulated Samples in Real Solutions/at Industrial Radioactive Industry Facilities

The KG-7, KG-8, KG-9, KG-10, and KG-11 titanosilicate samples were granules smaller than 300 µm in diameter, fabricated using fluidized bed granulation. The samples were not subject to any pretreatment.

The KG-1, KG-2, KG-3, KG-4, and KG-5 titanosilicate samples were granulated materials shaped as spheres or cylinders (fabricated by screw rotor and centrifugal pelletizing). Before use, the samples were crushed and dispersed on vibrating sieves to obtain a 0.25–0.5 mm fraction.

The KG-12, KG-13, KG-14 samples were light-yellow granulated materials with a particle size of 0.2–0.5 mm. These samples were also not subjected to any pretreatment.

The following sorbents were used as reference sorbents: TiSi-BS; FNS-10; Thermoxide-35; KY-2 × 8; KL; MDM; NaA; and SRM-Sr.

The following solutions were used as the liquid phase for 137Cs sorption:

- -

- 1.0 mol/dm3 NaNO3, pH = 6.0;

- -

- model solution of nuclear power plant with a RBMK-type reactor, g/dm3:

NaNO3, 298; KNO3, 14.1; NaOH, 4.0; pH = 13.0;

- -

- Model solution of nuclear power plant core residue with a WWER-type reactor, g/dm3: Na+, 78.5; K+, 29.6; NO3, 134; Cl−, 6.23; SO42−, 11.0; and BO2, 100 (in conversion to H3BO3); total salt content, 359; pH~13.

Before starting the experiments, the radionuclide 137Cs was added to the solutions and incubated for at least three days at ambient temperature.

The following solutions were used as the liquid phase in 90Sr sorption:

- -

- 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2, pH = 6.0;

- -

- real seawater

Before starting the experiments, the indicator amounts of radionuclide 90Sr were added to water. 90Sr radionuclide (~105 Bq/dm3) was added to water and incubated at ambient temperature for at least three days.

The sorption properties of materials were studied under static and dynamic conditions.

The adsorption under static conditions was conducted by continuous stirring of a 0.1 g air-dried adsorbent sample (weighed with an accuracy of 0.0001 g) with 20 mL of solution for 48 h. The mixture was then filtered through a white ribbon paper filter, and specific activity of 137Cs or 90Sr in the filtrate was determined. The distribution coefficient (Kd) of 137Cs (90Sr) was calculated using the formula:

where Ao and Af denote the specific activity of the adsorbed 137Cs or 90Sr radionuclide in the feed solution and filtrate, respectively, Bq dm−3;

Vl is the volume of the liquid phase, cm3; and

ms is the sorbent mass, g.

During sorption of 90Sr from 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2, in addition to Kd of 90Sr, the static exchange capacity (SEC) for calcium and the separation coefficient of the Sr/Ca pair (DSr/Ca) were also calculated according to Formulas (2) and (3), respectively:

where Co and Cf are the concentrations of Ca2+ ions in the initial solution and in the filtrate, respectively, mol/cm3;

SEC = (Co − Cf) × Vl/ms

DSr/Ca = (Kd × Cf)/SEC

Vf is the volume of the liquid phase, cm3;

ms is the sorbent mass, g;

SEC is the static exchange capacity for calcium, mmol/g; and

Kd is the distribution coefficient of 90Sr, cm3/g.

Experiments under the dynamic conditions were carried out as follows. A total of 3 mL of sorbent was accurately measured using a graduated cylinder, previously soaked under a layer of water for 12 h. The sorbent was quantitatively transferred to a plastic sorption column with an inner diameter of 8.5 mm, and the solution was passed through the sorbent at a rate of 10 mL/h using a peristaltic pump (3.3 column volumes (c.v.)/h). Filtrates after the column were collected fractionwise, and the specific activities of radionuclide 137Cs (90Sr) were determined. Based on the filtrate analysis findings, the output sorption curves were constructed in the coordinates ‘purification coefficient (Kpur) vs. the volume of the passed solution (Vp)’ expressed in column volumes (c.v.). The Kpur value was calculated using the formula:

where Ao and Af are the specific activities of 137Cs(90Sr) in the initial solution and in the filtrate, respectively, Bk/dm3.

Kpur = Ao/Af,

2.9. Determining the Specific Activity of 137Cs and 90Sr and Concentration of Calcium Ions in Solutions

The specific activity of 137Cs in solutions was determined by gamma spectrometry using the 661 keV gamma line. The specific activity of 90Sr in solutions was determined by the total beta activity of the 90Sr+90Y pair after exposure of the analyzed solutions for at least 14 days.

Activity measurements were performed using the SCS-50M spectrometric complex (Green Star Technologies, Moscow, Russia). Concentrations of calcium ions in the solutions were determined using the volumetric complexometric method.

3. Results

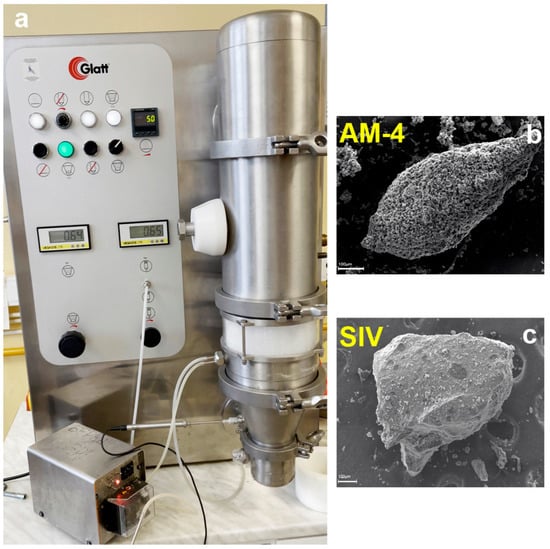

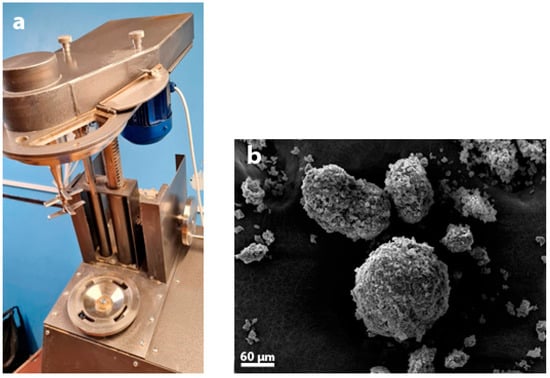

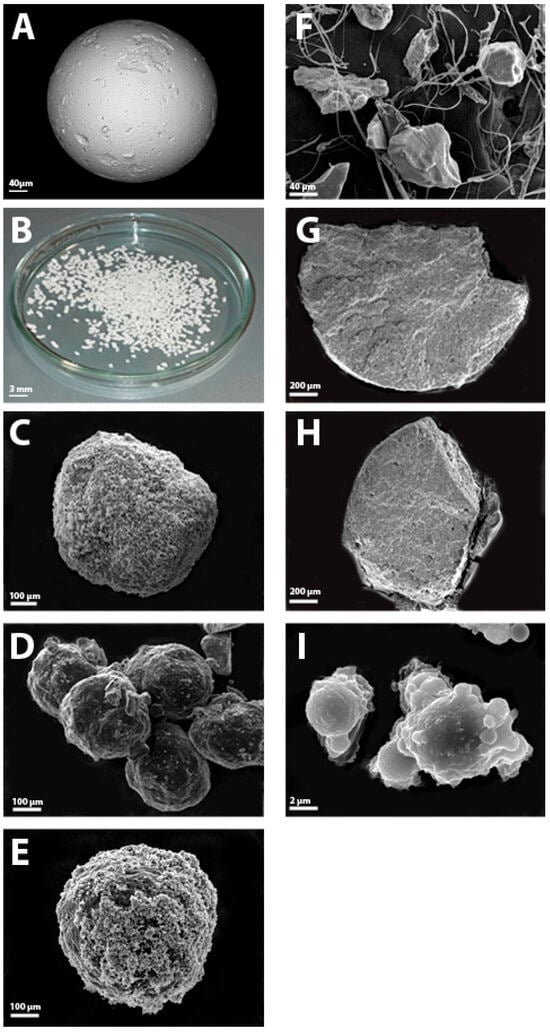

Five different methods were tested to select the optimal conditions for granulation of the synthesized products: fluidized bed granulation (Mini Glatt unit (D. Mendeleev Russian Chemical and Technological University, Moscow, Russia)) (Figure 3), spray dry granulation (Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology, Moscow, Russia), spray bed granulation (TL-20, Kola Science Center of RAS, Russia) (Figure 4), screw rotor granulation (FSH-003RK02, Kola Science Center of RAS, Russia) (Figure 5), and manual pressing of paste through a stainless steel sieve with a 1 mm mesh size.

Figure 3.

(a) Titanosilicate granulation using a Mini Glatt granulator and the SEM images of AM-4 (b) and SIV (c) granules.

Figure 4.

(a) Granulation of AM-4 using a TL-020 granulator, ALB-Group, Dzerzhinsk, Russia) and (b) a SEM image of AM-4 granules.

Figure 5.

(a) Granulation of ETS-4 using an auger pelletizer (FSH-003RK02) and (b) a SEM image of ETS-4 granules.

Chlorinated rubber, being a readily available industrial material, was selected as the initial candidate for fluidized bed granulation. In a parallel process involving fluidized bed experiments, granules were prepared without employing any binders (using distilled water only). Granules were obtained in both cases. However, larger granules (>20 μm) (Figure 3b) can be prepared by spray bed granulation compared to the fluidized bed process. The shortcomings of this granulation process are the production of granules exhibiting potentially worse mechanical properties in large volumes of industrial solutions and the risk of mechanical abrasion of the granules.

The results of the granulation experiments are presented in Figure 6 and Table 1. The results of the experiments measuring the mechanical strength of pellets are listed in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Photographs and SEM images of sorbent granules depending on the granulation method employed: (A) Therrmoxide 35; (B) SIV fabricated without using a binder (pressing the paste through a sieve); (C) AM-4 with H2O or a solution of 40% liquid glass (centrifugal pelletizing); (D) SIV with 40% liquid glass solution (fluidized bed granulation on a cellulosic carrier); (E) SIV with 40% liquid glass solution (fluidized bed granulation on a cellulosic carrier); (F) SIV with 33% solution of CR-20 + o-xylene (fluidized bed granulation); (G) SIV with 40% liquid glass solution (screw rotor pelletizing); (H) SIV with mother liquor solution (screw rotor pelletizing); (I) SIV with 40% liquid glass solution (fluidized bed granulation (spray drying)).

Table 1.

Methods used for fabricating sorbent granules.

Table 2.

Pellet strength (reference Thermoxide 35).

Samples of inorganic sorbents synthesized at the Center for Nanomaterial Science of the Kola Science Center, Russian Academy of Sciences (Table 3) were used to study the sorption of trace amounts of 137Cs and 90Sr radionuclides from model solutions of various compositions.

Table 3.

Methods used for fabricating sorbent granules.

Upon sorption of 137Cs from 1.0 mol/dm3 NaNO3 solution, the KG-7 sample exhibits the best sorption characteristics. The Kd value of 137Cs on this sample is 9.0 × 104 cm3/g, being comparable to those of the known sorbents TiSi-BS, FNS-10 and Thermoxide-35. The Kd values on the KG-9, KG-10, and KG-11 samples are also quite high: (1.3–2.6) × 104 cm3/g. The lowest Kd values of 137Cs (1.5 × 103 cm3/g) were observed for the KG-8 sample. Among cellulose-based sorbents, the best values are observed for the KG-13 core (Kd 137Cs = 3.2 × 103 cm3/g).

Table 4 summarizes the distribution coefficients (Kd) of 137Cs on the studied samples upon sorption from solutions of various compositions. Here and below, the average Kd values according to the results of two parallel experiments are shown. The discrepancy of Kd values in parallel experiments did not exceed 10%.

Table 4.

The distribution coefficient (Kd) of 137Cs on sorbent samples.

The sorption characteristics of the sorbents decrease abruptly upon sorption of 137Cs from the model solutions of the cubic residues from nuclear power plants (NPPs) with RBMK and WWER reactors. The Kd of 137Cs in the aforementioned model solutions are one or two orders of magnitude lower than those of the commercial Thermoxide-35 sorbent. Sorption of 137Cs onto cellulose samples from cubic residues of WWER nuclear power plant virtually does not take place.

Upon sorption of 90Sr from 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2 solution, pH = 6.0, the best sorption characteristics are observed for the KG-8 and KG-10 samples; the Kd values of 90Sr onto them are comparable to those of the known sorbents TiSi-BS and MDM.

Upon sorption of 90Sr from seawater, the best characteristics among the samples synthesized during the project are also observed for the KG-8 and KG-10 samples. Among all the studied sorbents, the SRM-Sr sorbent is characterized by the maximum Kd 90Sr in seawater.

Table 5 lists the distribution coefficient (Kd) of 90Sr, the static exchange capacity (SEC) for calcium, and the separation coefficient of the Sr/Ca pair (DSr/Ca) during sorption of 90Sr from a solution of 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2 onto the studied samples.

Table 5.

The distribution coefficients (Kd) of 90Sr, the static exchange capacity (SEC) for calcium, and the separation coefficients of the Sr/Ca pair (DSr/Ca) on titanosilicate sorbents and reference samples.

The findings demonstrate that all the samples of inorganic sorbents synthesized at the Nanomaterial Center of the Kola Science Center, RAS, exhibit high sorption characteristics with respect to 90Sr in the presence of competing Ca2+ cations. The KG-8 and KG-10 samples have the best characteristics.

Table 5 summarizes the Kd values for the sorbents studied upon extraction of 90Sr from real seawater.

The findings demonstrate that during sorption of 90Sr from seawater, the KG-8 and KG-10 samples exhibit the best characteristics among the samples synthesized at the Nanomaterial Center of the KSC RAS (Table 6). Among all the studied sorbents, the reference sample, the sorbent SRM-Sr, has the maximum Kd 90Sr in seawater.

Table 6.

The distribution coefficients (Kd) of 90Sr onto various sorbents upon sorption from seawater.

Upon dynamic purification to remove 137Cs from the model solution of the WWER nuclear power plant bottom residue, the KG-5 sample is most efficient among the samples studied.

Upon dynamic purification to remove 90Sr from 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2 solution, the most efficient samples are KG-2 and KG-5 (AM-4 and SIV with 40% liquid glass solution); 90Sr slip on them was not observed when passing more than 100 c.v. of solution. The purification coefficients (Kc.v.) for these sorbents are more than 1000. The sorption indices are much lower for all other samples studied in this project. The best rates of dynamic purification to remove 90Sr are observed for the MDM sorbent.

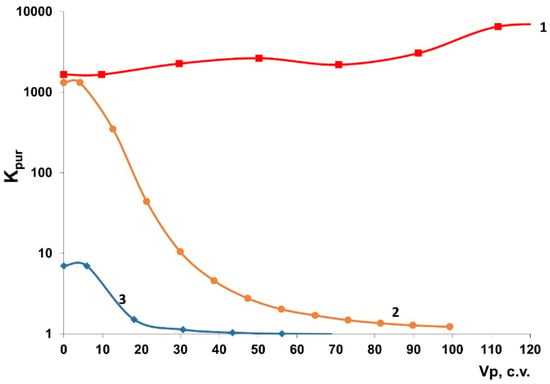

3.1. Sorption of 137Cs Under Dynamic Conditions

Figure 7 shows the output curves of sorption of 137Cs from a model solution of the cubic residue from the nuclear power plant with a WWER-type reactor onto the KG-2, KG-5 (AM-4 and SIV samples with 40% liquid glass solution), as well as onto Thermoxide-35 Ferro cyanide sorbent.

Figure 7.

The output curves of sorption of 137Cs radionuclides onto granulated sorbents: (1) Thermoxide-35; (2) KG-5 (SIV with 40% liquid glass: solution); and (3) KG-2 (AM-4 with 40% liquid glass solution) under dynamic conditions.

Our findings show that the efficiency of dynamic purification to remove 137Cs from the model solution of cubic residue from the WWER NPP using the KG-5 sample (SIV with 40% liquid glass solution), being the highest under static conditions (Table 4), was still significantly lower than that for the commercial Thermoxide-35 sorbent. When passing ~100 c.v. of the model solution through the KG-5 sample (SIV with 40% liquid glass solution), sorption of 137Cs almost stopped, whereas when passing through the Thermoxide-35 sorbent, the Kpur values were more than 1000 units. Furthermore, after passing 100 c.v. of the model solution, the granules of the KG-5 sample (SIV with 40% liquid glass solution) lost their mechanical strength and were hardly discharged from the column.

An even lower sorption efficiency was observed for the KG-2 sample (AM-4 with 40% liquid glass solution), for which the Kd of 137Cs values were lower compared to those of the KG-5 sample (SIV with 40% liquid glass solution).

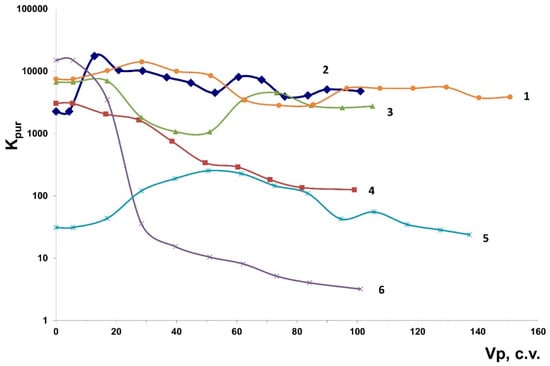

3.2. Sorption of 90Sr Under Dynamic Conditions

Figure 8 shows the output curves of sorption of 90Sr from a solution of 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2, pH = 6.0, onto various samples manufactured at the Nanomaterial Center, as well as onto the MDM sorbent.

Figure 8.

The output data for the 90Sr sample in the set: (1) MDM; (2) KG-5 (SIV cylinders with 40% liquid glass solution); (3) KG-2 (AM-4 spheres with 40% liquid glass solution); (4) KG-1 (spheres ETS-4 with 40% liquid glass solution); (5) SIV+cellulose core; and (6) KG3 (ETS-4 cylinders with 40% liquid glass solution).

Figure 8 demonstrates that the KG-5 and KG-2 samples produced at the Nanomaterial Center are most efficient for dynamic purification to remove 90S from 0.01 mol/dm3 CaCl2 solution; no 90Sr slip on them is observed when passing more than 100 c.v. solution. The purification coefficients (Kpur) for these sorbents are >1000.

For the ETS-4 samples of different morphologies (spheres and cylinders), as well as the KG-1 and KG-3 samples, the Kpur value decreases abruptly when passing 100 c.v. solution: from 1000 to 100 for KG-1 and from 10,000 to 10 for KG-3. For the SIV+cellulose core sample, the Kpur values observed when passing 100 c.v. solution lie within the range of 30–200. The best dynamic purification rates are observed for the MDM sorbent: the Kpur values for it are ~1000 when passing at least 160 c.v. solution.

4. Discussion

A key outcome of this work is the transition from powdered sorbents to their granulated forms. To achieve this, several granulation techniques are evaluated. Among them, granulation in a fluidized bed proved to be the most effective for producing spherical granules of synthetic ivanyukite (SIV) and zorite (ETS-4), providing particle diameters below 3 mm and minimizing product losses. Screw-rotor granulation also appears promising, as it enables the production of granules with mechanical strength comparable to commercial analogues such as Thermoxide-35. Despite the advantages of fluidized-bed granulation, its high cost limits its practical application in large-scale production.

Sorption tests showed a pronounced difference in the behavior of granulated sorbents under static and dynamic conditions. The KG-5 sample, which exhibited the best sorption performance toward 137Cs and 90Sr under static conditions, lost its sorption efficiency in dynamic mode when the volume of processed solution exceeded 100 c.v., due to mechanical degradation of the granules. In contrast, the commercial sorbent Thermoxide-35 maintained high decontamination factors even after 1000 c.v. This suggested the need to improve the strength of the initial granules and to modify the granulation procedure (including variation in the conditions for powder preparation, granulation rate, applied pressure during granulation, and drying regime).

For strontium removal, several synthesized sorbents, in particular KG-2 and KG-5, demonstrated high efficiency in neutral calcium-containing solutions, maintaining decontamination factors above 1000 under dynamic conditions. The best results for dynamic purification of 90Sr were obtained with the MDM sorbent, which retained high efficiency at large solution throughputs. In seawater tests, the KG-8 and KG-10 samples showed the highest sorption performance among the newly developed materials, although the maximum distribution coefficient was observed for the reference commercial sorbent SRM-Sr.

The most probable reason for the high Kd values of KG-5 (SIV + liquid glass) for 137Cs in neutral nitrate solutions, and its low Kd values in alkaline RBMK/WWER model solutions, is related not so much to the Na+/K+ ratio—since the sorbent is synthesized without any potassium source, unlike many similar procedures for ivanyukite analogues—but rather to the high overall salt content in the RBMK/WWER models compared with simple NaNO3 solution. A pH of 13 is not, by itself, a problem for maintaining sorbent performance, as was previously shown and first established in the work “Sorption of cesium and strontium radionuclides onto crystalline alkali metal titanosilicates” [].

The effects of pore blocking, partial dissolution, and swelling of the binder in the granules were not studied in detail in this work, and therefore no well-grounded conclusions can yet be drawn from this perspective without additional investigations. Clarifying these issues is planned for the next stage of work, which will focus on improving the granulation procedure to obtain granules with abrasion resistance comparable to that of Thermoxide-35.

The mechanical degradation of granules in a dynamic column flow is most likely associated with their initially low strength, which in turn is probably caused by an insufficient amount of binder and non-optimal drying parameters. As a consequence, the granules are more susceptible to abrasion during solution flow through the column.

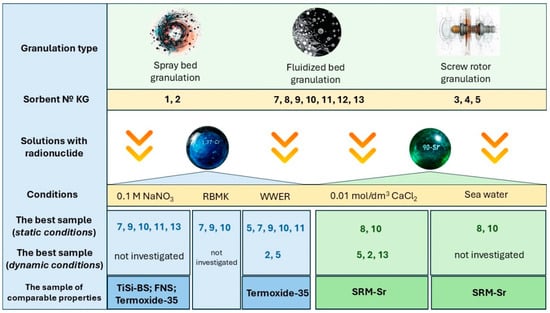

The relationship between specific surface area and sorption properties of the granules is not discussed in detail in this paper, because no direct correlation between these parameters was observed. For dynamic tests, the primary selection criterion was the crushing strength of the granules (for example, in the case of KG-5). As can be seen from the generalized scheme (Figure 9), sorbent KG-10 showed the best performance under static conditions in all experiments; however, due to the size of its granules, it was not used in dynamic tests. Instead, a sorbent with similar properties, KG-5, was employed.

Figure 9.

Generalized experimental scheme for granular sorbents.

The sample KG-5 (SIV with 40% liquid glass binder) has a very high specific surface area (170.69 m2/g) and performs well for Sr2+ and Cs+ in several matrices, but then loses mechanical integrity during long-term Cs+ column runs. The authors suggest that specific surface area is not directly responsible for changes in sorption behavior; rather, both the nature and amount of binder and the details of granule preparation play a significant role. In the authors’ view, there is no simple compromise or monotonic relationship between crushing strength and overall mechanical stability. Mechanical strength is most likely governed primarily by the cohesion between individual particles provided by the binder. In addition, the binder must be stable in the working salt solutions, at the relevant pH, and over the entire contact time between the sorbent granules and the treated solution. In the present work, the authors were able only to identify optimal combinations of granule configuration and binder type. Further development will require a more detailed optimization of parameters such as binder content, treatment time with the binder, initial moisture content and porosity of the sorbent, drying conditions for the granules, and the rate and duration of additional rolling and densification (for example, in centrifugal granulation).

Nevertheless, there is a certain relationship between crushing strength and porosity: samples with the highest specific surface area also tended to exhibit higher crushing strength (for example, KG-5).

The obtained data confirm that the granulation methods developed in this work make it possible to preserve the key chemical and radiochemical properties of the synthesized materials. However, limitations remain: although the new sorbents are efficient in several model systems, they do not yet reach the selectivity and long-term durability of the best commercial products under the complex conditions of real nuclear waste processing. Bridging this gap will require further optimization of both sorbent composition and granulation technology.

Overall, this study advances the field by demonstrating the feasibility of producing functional titanosilicate granules from industrial by-products without specialized polymer binders, and by identifying promising candidate materials and processing routes for further development. The results also highlight the critical importance of both the chemical nature and mechanical stability of sorbents for their industrial application in radiochemistry and environmental remediation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of producing titanosilicate pellets without the use of special polymer binders, employing intermediate products from local mining and metallurgical plants. The main project objective—to develop a universal and environmentally benign method for manufacturing synthetic mineral analogues—was successfully achieved.

The key findings can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- granulated titanosilicate sorbents retain their favorable chemical and radiochemical properties, making them suitable for use in radiochemical applications;

- (2)

- several sorbent samples synthesized at the Nanomaterial Center of the Kola Science Center, RAS, are effective for the removal of cesium radionuclides from neutral salt solutions. However, in the purification of nuclear power plant residues, all studied sorbents were significantly less efficient than commercial analogues (for example, Thermoxide-35);

- (3)

- some synthesized sorbents (in particular, KG-2 and KG-5) exhibit high efficiency in the removal of strontium radionuclides from neutral calcium-containing solutions, with purification coefficients exceeding 1000, while the MDM sorbent shows the highest purification efficiency for strontium;

- (4)

- the granulation methods tested (spray bed, screw-rotor, fluidized bed, and manual pressing) allow the production of mechanically stable granules, with spray bed granulation being the most suitable for SIV- and ETS-4-based materials.

- (5)

- the materials obtained can contribute to the integrated processing and safe disposal of industrial by-products, thereby supporting sustainable development goals in green chemistry.

Overall, the developed approach enables the fabrication of efficient, environmentally friendly, and mechanically robust inorganic sorbents for the selective extraction of radionuclides from complex solutions, although further optimization is required to match the performance of the best commercial products in certain applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.G. and V.N.Y.; methodology, G.O.S.; validation, A.I.N. and E.A.S.; formal analysis, N.A.N.; investigation, G.O.K., V.V.M., N.A.N., D.V.G., Y.A.P. and A.I.K.; resources, V.N.Y.; data curation, V.V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.O.K.; writing—review and editing, E.A.S. and V.V.M.; visualization, Y.A.P.; supervision, A.I.N.; project administration, G.O.K.; funding acquisition, G.O.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the (1) PhosAgro/UNESCO/IUPAC grant in green chemistry, Project 52 “The Development of an Universal and Green method for Granulation of Synthetic Titanosilicate Materials (Sorbents, Catalysts, Recoverable Matrices) Created Based on End-Product Waste from Regional Ore-Enrichment and Metallurgical plants”, Contract number 4500422248; (2) Russian Science Foundation grant No. 24-63-00006 (part of the work on synthesizing the SIV sorbent).

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided upon request with the permission of the leading organization for expert evaluation purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the team of the D.I. Mendeleev Russian Chemical Technology University (Moscow), staff of the Glatt company (Moscow, Russia), Elena Beresneva and Ilja Gorodetsky, as well as staff of the TTC Technology Training Center (Binzen, Germany) for their assistance in conducting the research, ongoing support, and valuable advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM-4 | the full name for this material is Aveiro-Manchester-4. It is the microporous titanosilicate with the general formula Na3(Na,H)Ti2O2[Si2O6]2·H2O |

| STA | the product with the general formula (NH4)2TiO(SO4)2∙H2O. It is a product of titanite ore treatment using the sulfuric acid methodology (JSC Apatit, PhosAgro company, and Kola Science Center, Russia) |

| STM | the titanyl sulfate (TiOSO4∙H2O), one of the semi-products of titanite ore treatment using the sulfuric acid methodology (mining JSC Apatit, PhosAgro company, and Kola Science Center, Russia) |

| SL3 | the synthetic titanosilicate whose crystal structure consists of Ti2Si4O10(OH)4 nano-blocks being extremely resistant to destruction |

| ETS-4 | the synthetic titanosilicate, an analog of zorite mineral Na9Si12Ti5O38(OH)∙12H2O |

| MDM | the sorbent based on modified manganese dioxide (TU 2641-001-51255813-2007) |

| IONSIV IE 911 | the synthetic sorbent with the sitinakite-like crystal structure Na3Ti4Si2O13(OH)∙2H2O |

| SIV | the full name for this material is synthetic ivanyukite. It is a synthetic analog of the mineral ivanyukite-Na with the general formula Na4(TiO)4(SiO4)3∙nH2O |

| SN | the synthetic analog of the mineral natisite, Na2TiSiO5 |

| TiSi-BS | the semi-crystalline sodium silicothitanate synthesized at the Institute of Sorption and Problems of Endoecology (ISPE), National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, (Kyiv, Ukraine), a prototype (the reference sample from the collection of sorbents stored at the Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, RAS). |

| FNS-10 | the ferrocyanide sorbent of FNS-10 grade based on potassium nickel ferrocyanide, applied onto silica gel using the sorption method, TU 2641-003-51255813-2007 (manufactured at the Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, RAS) |

| Thermoxide-35 | the spherical granulated inorganic sorbent based on nickel ferricyanide and zirconium hydroxide, TU 6200-305-12342266-98, manufactured by research and production company “Thermoxide” (Zarechny, Sverdlovsk Region, Russia) |

| KL | the natural clinoptilolite of the Shivertui deposit (Chita Region, Russia) |

| KY-2 × 8 | the strongly acidic sulfocation cationite |

| NaA | the synthetic zeolite, grade A, TU 2163-003-15285215-2006 produced at the Ishimbay Specialized Chemical Plant of Catalysts (Republic of Bashkortostan, Russia) |

| SRM-Sr | the sorption-reagent material based on barium silicate synthesized at the Institute of Chemistry, Far East Division, Russian Academy of Sciences (Vladivostok, Russia) |

| CR-20 | the chlorinated rubber (Attika company, St. Petersburg, Russia) |

| RBMK | the type reactor–(the abbreviation adopted in Russia and in international journals: Reaktor Bolshoy Moshchnosti Kanalnyy, meaning “High Power Channel-type Reactor) |

| WWER | the type reactor–the water-water energetic reactor. |

References

- Oleksiienko, O.; Wolkersdorfer, C.; Sillanpää, M. Titanosilicates in cation adsorption and cation exchange. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaillon, J.G.; Andres, Y.; Mokili, B.M.; Abbe, J.C.; Tournoux, M.; Patarin, J. Study of the ion exchange selectivity of layered titanosilicate Na3(Na,H)Ti2O2[Si2O6]2·2H2O, AM-4, for strontium. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2002, 20, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikova, G.O.; Zhitova, E.S.; Selivanova, E.A.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Ivanyuk, G.Y.; Kasikov, A.G.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V.; Elizarova, I.R.; Kiselev, Y.G.; et al. The new method for obtaining titanosilicate AM-4 and its decationated form: Crystal chemistry, properties and advanced areas of application. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 313, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malara, A.; Fotia, A.; Giglio, F.; Pastura, F.; Bonaccorsi, L.; Frontera, P. Effect of Engelhard titanosilicate microporous material on photocatalytic performance of cement. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovskiy, I.A.; Yanicheva, N.Y.; Stalyugin, V.V.; Panikorovskii, T.L.; Golov, A.A. Sorption of multivalent cations on titanosilicate obtained from natural raw materials: The mechanism and thermodynamics of sorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 311, 110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Navarro, M.T.; Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Corma, A.; Yu, J. Titanosilicate zeolite precursors for highly efficient oxidation reactions. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12341–12349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, K.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; He, M. Insights into the efficiency of hydrogen peroxide utilization over titanosilicate/H2O2 systems. J. Catal. 2020, 381, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J. Development on hydrophobic modification of aluminosilicate and titanosilicate zeolite molecular sieves. Appl. Catal. A 2021, 611, 117952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prech, J. Catalytic performance of advanced titanosilicate selective oxidation catalysts—A review. Sci. Eng. 2018, 60, 71–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Hafeez, M.; Kim, H.; Hong, H.; Kang, J.; Um, W. Inorganic waste forms for efficient immobilization of radionuclides. ACS ES&T Eng. 2021, 1, 1149–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Liu, H.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, W. Extraction of Rubidium and Cesium Ions by Adsorption–Flotation Separation in Titanosilicate–Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Bromide System. Separations 2025, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Ivanyuk, G.Y.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Men’shikov, Y.P. Khibiny; Association with the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland: Apatity, Russia, 2005; ISBN 5-900395-48-0. Available online: https://www.mindat.org/reference.php?id=17737830 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ivanov, N.P.; Marmaza, P.A.; Shichalin, O.O.; Dran’kov, A.N.; Rastorguev, V.L.; Marchenko, A.V.; Pisarev, S.M.; Zernov, Y.G.; Maiorov, A.Y.; Fedorets, A.N.; et al. Removal of Cs(I) and Sr(II) from liquid media with crystalline titanosilicates prepared by hydrothermal synthesis. Radiochemistry 2024, 65, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovskiy, I.A.; Shushkov, D.A.; Ponaryadov, A.V.; Panikorovskii, T.L.; Krivoshapkin, P.V. Controlled reprocessing of leucoxene concentrate for environmentally friendly production of titanosilicate—An effective sorbent for strontium and cesium ions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M. Natural vs. synthetic zeolites. Crystals 2020, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallette, A.J.; Seo, S.; Rimer, J.D. Synthesis strategies and design principles for nanosized and hierarchical zeolites. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Wang, H.; Yokoi, T.; Tatsumi, T. Synthesis of Ti-containing extra-large-pore zeolites of Ti-CIT-5 and Ti-SSZ-53 and their catalytic applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 276, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, D.; Rohani, S.; Kondo, J.N.; Tatsumi, T. Catalytic dehydration of ethanol-to-ethylene over Rho zeolite under mild reaction conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 282, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Gordina, N.E.; Zhidkova, A.B.; Efremov, A.M. Mechanochemical synthesis of granulated LTA zeolite from metakaolin. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 5383–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhi, A.; Kazemeini, M.; Ahmadi, S.J.; Kazemian, H. Fabrication of granulated NaY zeolite nanoparticles using a new method and study of the adsorption properties. Powder Technol. 2012, 231, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q. A Kind of Preparation Process of Novel Tower Granulation Compound Fertilizer production with Tower Granulation. Chinese Patent CN110256143, 20 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Granular Molecular Sieve and Preparing Method Thereof. Korean Patent KR 1019990000703, KOREA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF CHEMICAL TECHNOLOGY, 19 May 1999. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/result.jsf?_vid=P20-MIHG6M-57732 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Lamberov, A.A. Method for Granulation of Zeolite as Synthetic Detergent Component. Russian Patent RU2615506C1, 5 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- LLC “New Technologies Company” (RU). Method for Obtaining Granular Zeolite Type X Without Binders. Russian Patent RU2653033C1, 4 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LLC “New Technologies Company” (RU). Method for Obtaining Granular Zeolite Adsorbent. Russian Patent RU2655104C1, 23 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- BASF Aktiengesellschaft (DE). Method for Obtaining a Solid Containing Zeolite. Russian Patent RU2353580C1, 25 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- GREJS GMBKh UND KO.KG (DE). Adsorbing Material Consisting of a Porous Functional Solid Introduced into a Polymer Matrix. Russian Patent RU2329097C2, 20 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, L.; Rodriguez, G.; Orjuela, A. Study of the pilot-scale pan granulation of zeolite-based molecular sieves. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, K.; Akhtar, F. Freeze granulated zeolites X and A for biogas upgrading. Molecules 2020, 25, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M. Hydrothermal synthesis of zeolite aggregate with potential use as a sorbent of heavy metal cations. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1183, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.; Poveda, Y.A.; Khadivi, M.; Rodriguez, G.; Görke, O.; Esche, E.; Godini, H.R.; Wozny, G.; Orjuela, A. Synthesis and granulation of a 5A zeolite-based molecular sieve and adsorption equilibrium of the oxidative coupling of methane gases. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2017, 62, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, L.G.; Nikolaev, A.I.; Artemenkov, A.G.; Shchukina, E.S.; Maslova, M.V.; Kiselev, Y.G. Pilot-plant production of titanosilicate sorbents. Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 2024, 57, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, L.G.; Schukina, E.S.; Maslova, M.V.; Nikolaev, A.I.; Tosio, O.; Khirimoto, O. Method for Obtaining a Sodium-Containing Titanium-Containing Sorbent. RU Patent 2699614, 6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimova, L.G.; Nikolaev, A.I.; Maslova, M.V.; Schukina, E.S.; Samburov, G.O.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Ivanyuk, G.Y. Titanite ores of the Khibiny Apatite–Nepheline deposits: Selective mining, processing and application for titanosilicate synthesis. Minerals 2018, 8, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Anderson, M. Microporous titanosilicates and other novel mixed octachedral-tetrahedral framework oxides. European J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 5, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.; Roe, A. Synthesis, characterization and crystal chemistry of microporous titanium-silicate materials. Zeolites 1990, 10, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, D.; Nenoff, T.; Headley, T. Characterisation of UOP IONSIVE IE-911. 2001, (No. SAND2001-0999). Sandia National Lab. (SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States); Sandia National Lab. (SNL-CA), Livermore, CA (United States). Available online: https://scholar.google.ru/scholar?hl=ru&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=38.%09Nyman%2C+D.%3B+Nenoff%2C+T.%3B+Headley%2C+T.+Characterisation+of+UOP+IONSIVE+IE-911.+2001%2C+%28No.+SAND2001-0999%29.+Sandia+National+Lab.%28SNL-NM%29%2C+Albuquerque%2C+NM+%28United+States%29%3B+Sandia+National+Lab.%28SNL-CA%29%2C+Livermore%2C+CA+%28United+States%29.+&btnG= (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Oleksiienko, O.; Sillanpää, M. Sol–gel synthesized titanosilicates for the uptake of radionuclides. In Advanced Water Treatment Adsorption; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 361–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdov, S.; Kostov-Kytin, V.; Petrov, O. Improved powder diffraction patterns for synthetic paranatisite and natisite. Powder Diffr. 2012, 17, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyutin, V.V.; Nekrasova, N.A.; Yanicheva, N.Y.; Kalashnikova, G.O.; Ganicheva, Y.Y. Sorption of cesium and strontium radionuclides onto crystalline alkali metal titanosilicates. Radiochemistry 2017, 59, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).