Abstract

Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa L.) is a valuable raw material rich in health-promoting compounds, including anthocyanins, making it an excellent ingredient in food such as bread. In this research, water in the bread recipe was substituted with chokeberry extract (ChE). Dried chokeberry powder was used to obtain extracts with 0 and 7.5 °Brix content. Two types of water chokeberry extracts (0 and 7.5 °Brix ChE) were applied in the wheat bread recipe with doses of 10, 15, 20, and 30% (m/m), replacing water, respectively. The obtained chokeberry extract contributed to the enrichment of the bread in total polyphenol content and the antioxidant capacity. The control bread sample (i.e., without the extract) had a total polyphenol content (TPC) of 25.706 mgGAE/100 g, while the bread samples with the extract had TPC values ranging from 29.037 to 45.282 mgGAE/100 g. At the same time, adding chokeberry extract to the bread matrix contributed to increasing the antioxidant capacity. Bread with ChE was characterized by the same dough yield and loaf volume of bread compared to the control sample, but with changed oven loss, total baking loss, bread yield, specific volume, bread acidity and porosity of the crumb. However, there was no statistically significant effect on the chewiness and cohesiveness of the crumb in the sample texture (α = 0.05). A small effect of anthocyanins on the color of bread was observed, and sugars played the dominant role in the tested samples. Chokeberry in the form of an aqueous extract added to wheat bread can be an excellent ingredient in bread, fulfilling both a nutritional and technological function in the design of functional foods.

1. Introduction

Bread is a staple food, with an average annual consumption of 70 kg per person worldwide. It is made mainly from flour, water, yeast and salt. The ingredients are kneaded and fermented (using yeast) to form a dough, which is then baked. A crucial factor in the production of wheat bread is the chemical composition of wheat flour, particularly the content of gluten proteins (gliadin and glutenin), which later form gluten in the dough. It is a protein substance that gives dough elasticity, the ability to retain gases, and a spongy structure to bread. Wheat dough containing the appropriate amount of good-quality gluten is characterized by the presence of small, even spaces filled with CO2 produced by the yeast. These spaces are also evenly distributed throughout the dough. The result is bread with a large loaf volume and a crumb with large, regular pores. The bread-making process involves five main stages: mixing the raw ingredients, fermentation/ aeration, dividing/ shaping, proofing, and baking. The starch gelatinization, protein denaturation, and the transformation of raw dough to highly digestible, brown-colored, flavored, and porous bread occurs through the baking process. Wheat bread is generally characterized by a relatively soft crumb and a dry crust [1,2].

Fortifying flour products with some natural additives allows enhancing their nutritional value while potentially improving their functional and sensory properties [3]. Bread, due to its frequent consumption, provides a good food matrix for introducing aronia powder, pomace, or extract.

Black chokeberries (Aronia melanocarpa L.) contain 1–2 g of total polyphenols, including 300–850 mg of anthocyanins (cyanidin-3-O-galactoside 60%, cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside) and over 1.5 g of catechins and their tannin polymers (80% of which are polymers longer than 10 units). Chokeberry fruits contain hydroxycinnamic acids as chlorogenic (35.5 mg/100 g) and neochlorogenic (21.5 mg/100 g), as well as many other compounds: flavonoids (quercetin), resveratrol, amygdalin [4,5,6]. Due to the presence of large amounts of anthocyanins, procyanidins, tannins, and chlorogenic acid, dark chokeberries (Aronia melanocarpa L.) have one of the highest antioxidant levels of any fruit studied to date. This chemical composition has earned them the distinction of being a “superfruit” [4]. Quercetin is the most potent antioxidant among the monomeric phenolic compounds found in chokeberries, followed by cyanidin glucoside and chlorogenic acid [7]. Moreover, in the aronia fruit are sugars such as sorbitol, fructose, glucose. Due to the health-promoting compounds in chokeberries, they are increasingly used as an ingredient in functional food, such as dairy products [8,9,10], confectionery [11,12], bakery and pastry products [13,14,15,16,17]. The sugar content of bread varies, and consumer awareness of a healthier diet has increased. To meet consumer demand, as well as public health recommendations, the baking industry is striving to reduce sugar content while maintaining the same product quality, which is obviously a challenging task [18,19]. Sugar serves various functions in the bread-baking process, such as browning, flavor, and moisture retention. Chokeberry fruits can be incorporated into the bread matrix, enriching it primarily with sugars, polyphenolic compounds, vitamins, and macro- and micronutrients [20,21].

In the literature, one can find research papers on adding chokeberry powder, pomace, or juice to bread or cookie recipes [14,15,16,17]. In our research, chokeberry was used in the bread recipe in the form of an aqueous extract, which had been previously obtained by extraction with alcohol. Using alcohol as the extractant resulted in extracts rich in bioactive compounds. The obtained ChE also contained sugars (7.5 °Brix); therefore, versions of the extract without sugar content were prepared by purifying the sample and obtaining a sample with a 0 °Brix content. Both of the aqueous aronia samples (with 0 and 7.5 °Brix) were applied in the wheat bread recipe with doses of 10, 15, 20, and 30% (m/m), replacing water, respectively. The study aimed to evaluate the effect of two types of prepared chokeberry extracts on the quality of wheat bread (without and with natural sugars). It is assumed that the sugar contained in the aqueous chokeberry extract may affect selected parameters of bread quality.

These studies can provide bread producers with valuable information on the quality of baked products enriched with bioactive compounds, and at the same time, show how a small amount of naturally occurring simple sugars contained in the raw material can change the product in terms of its organoleptic properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Wheat flour (Gdańskie Młyny, Gdańsk, Poland) type 650 purchased at a local supermarket was used to produce the product (bread). Freeze-dried chokeberries were purchased from LYOFOOD Sp. z o. o. (Kielce, Poland).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Chromatography Analysis of Chokeberry Fruits

The freeze-dried chokeberry fruit samples for chromatographic analysis were extracted using 70% methanol at a ratio of 1 g to 5 mL of the extraction solvent.

UHPLC-ESI-MS analysis was performed using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) coupled with a Bruker maXis spectrometer with an ESI source (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The reverse-phase chromatographic separation used a Kinetex™ 1.7 µm C18 100 Å, 100 mm × 2.1 mm LC column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The methods for separation and detection were previously detailed by Jarosz et al. (2024) [22].

Untargeted analysis of tandem mass spectrometric data was conducted using SIRIUS software version 6 1.0 with the CSI: FingerID web-service (Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany) [23]. The compound classes were predicted using the CANOPUS algorithm [24] from molecular fingerprints generated by CSI: FingerID. The categorization of MS/MS data records presented in the results Section 3 relies on NPClassifier [25], an automated structural classification of natural products based on their counted Morgan fingerprints.

The results of untargeted analysis are presented as the mean percentage of area, along with standard deviation (n = 3).

Furthermore, specific compounds were quantitatively analyzed using standards for confirmation. The concentrations of chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, and anthocyanins (cyanidin-3-hexoside and cyanidin-3-pentosides) were measured. Data processing was performed with TASQ 2.1 (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The limit of quantification (LOQ), where S/N > 15, was at least 0.01 μg/mL for chlorogenic acid and cyanidin-3-glucoside. The results of targeted analysis are presented as concentration in brackets (mg/100 g of dried fruit), along with the standard deviation (n = 3).

2.2.2. Preparation of Chokeberry Fruit Extracts

The chokeberry extracts were made according to Adamczyk et al. (2025) [26], where two types of chokeberry fruit extracts were obtained, namely with 0 and 7.5 °Brix content. Firstly, the 100.0 g of freeze-dried powdered chokeberries was suspended in 1000 mL of 70% methanol solution and extracted for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath (Polsonic, Warsaw, Poland). Then, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 7000 rpm in a laboratory centrifuge (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5430, Hamburg, Germany). Alcohol was removed from the sample using a vacuum evaporator (VWR VP 10 Autovac, Wolfertschwenden, Germany). The resulting amount of concentrated chokeberry extract was divided into two equal portions. The first portion was poured into a measuring cup and filled to 500 mL with distilled water to obtain an aqueous extract of 7.5 °Brix. The second portion was purified from sugars using a column containing adsorber LiChroprep RP-18 (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Next, phenolic compounds were eluted from the LiChroprep column with alcohol. After that, alcohol was removed, and concentrated aqueous chokeberry extract was poured into a measuring cup and topped up with distilled water to 500 mL (final total extract was 0 °Brix). The sugar content in the obtained chokeberry samples was measured by the digital refractometer PAL-1 Atago (Saitama, Japan), and the pH was determined er using pH-Burette 24 (Crison Instruments, Barcelona, Spain).

2.2.3. Laboratory Baking Test of Bread

The doughs of control and tested breads were prepared using a single-phase method according to Jakubczyk and Haber [1]. The control dough was made from 496.50 g wheat flour, 14.90 g of baker’s yeast (Lallemand, Józefów, Poland), 4.96 g of salt, and 288.00 mL of water, up to a consistency of 350 FU using a Brabender farinograph-E (Duisburg, Germany). The tested samples with two types of chokeberry fruit extracts contained

- Chokeberry fruit extract with 0 °Brix content were applied in the wheat bread with doses of 10% (m/m) (10%ChE0°Brix), 15% (m/m) (15%ChE0°Brix), 20% (m/m) (20%ChE 0°Brix), and 30% (m/m) (30%ChE0°Brix) replacing water in the recipe, respectively.

- Chokeberry fruit extract with 7.5 °Brix content were applied in the wheat bread with doses of 10% (m/m) (10%ChE7.5°Brix), 15% (m/m) (15%ChE7.5°Brix), 20% (m/m) (20%ChE7.5°Brix), 30% (m/m) (30%ChE7.5 °Brix) replacing water in the recipe, respectively.

Using a laboratory mixer (Mesko-AGD, Skarżysko-Kamienna, Poland), ingredients of the recipe were mixed, and the dough was fermented (30 min, 30 °C) in a fermentation chamber (Sveba Dahlen, Fristad, Sweden). Then, to release the excess CO2, the dough was punched down (one time, for 1 min) and again fermented at 30 °C for 30 min. After the fermentation was completed, 250 g dough pieces were formed, then placed in molds and placed in the fermentation chamber for optimal proofing (to double the original volume of the dough piece). Baking was conducted at 230 °C for 30 min in a baking chamber of a Classic electric oven (Sveba Dahlen, Fristad, Sweden). Afterward, the bread loaves were weighed and left to cool down. The baking of each type of bread was repeated twice, which constituted two production batches.

2.2.4. Baking Process and Quality Parameters of Breads

Twenty-four hours after baking, the tested breads were weighed. Then, the baking process parameters were calculated, such as dough yield (%), oven loss (%), total baking loss (%), and bread yield (%), described by Jakubczyk and Haber [1]. The volume of a bread loaf (cm3) was determined using millet grain, according to AACC Method No. 10-05.01 [27], and the specific volume of bread (cm3/g) was calculated based on the mass of cooled bread. Also, the crumb moisture content (%) was analyzed according to AACC Method No. 44-15.02 [28], and bread acidity [acidity degree] was determined using the titration method according to Jakubczyk and Haber [1]. The porosity of the crumb was determined by processing a digital image of a cross-section of bread samples obtained using a scanner with an optical resolution of 800 dpi using a V550 Photo scanner (Seiko Epson Corp., Suwa, Nagano, Japan). For quantitative analysis, the image file was processed using ImageJ software version 3.92. 1PL [29]. Automatic image correction is performed by formatting color coordinates into shades of grey. The image corrected in this way is divided into dark (pores) and light (crumb) areas. The ‘lasso’ tool combines dark pores and forms them into circles or ovals. The final image is calculated based on the pixels of the pores and crumb. The ratio of the pixel area of the pores to the area of the image itself is expressed as a percentage, which is characteristic when using the standardized method in Ukraine with the Zhuravliov device Petrusha 2018 [30]. The porosity determined in this way is less than the true porosity, but it is sufficient for analysis [31]. All analyses were performed in triplicate for all varieties of bread from each production batch.

2.2.5. TPC and Antioxidant Properties

The alcohol extracts of crumb bread samples were prepared for analysis of the total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant activity. Using an ultrasonic bath (Polsonic, Warsaw, Poland), the extraction process with alcohol was carried out at 25 °C. The obtained supernatants (extracts) were used for further analysis. The total phenolic content was assessed using the Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent with the method described by Singleton et al. (1999) [32] and expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) in milligrams per 100 g of samples. According to Re et al. (1999) [33], the antioxidant activity was carried out using the ABTS+ cation radical. The ferric ion reducing antioxidant potential (FRAP) assay was read at a wavelength of 593 nm against distilled water [34]. The values of the antioxidant activity (ABTS+, FRAP) of the studied samples were expressed in mmol TE/100 g (Trolox Equivalent).

Measurements carried out in triplicate using a spectrophotometer, Nicolet Evolution 300 (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2.6. Bread Crust and Crumb Color Parameters

The bread crust and crumb color parameters were determined using an UltraScan VIS colorimeter (HunterLab, Reston, VA, USA) in the CIE L*a*b* model (illuminant D65; a visual angle of 10°). The following parameters were determined: lightness (L*), redness+/greenness color saturation (a*), and yellowness+/blueness color saturation (b*). All analyses were performed in triplicate for all varieties of bread from each production batch [35].

2.2.7. Bread Crumb Texture Parameters

Instrumental measurement of crumb texture parameters was performed using the EZ-LX texturometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) supported by Trapezium X Texture PI software version 1.5.6 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The tested cube-shaped bread crumb samples with dimensions of 30 mm × 30 mm × 40 mm, taken from different parts of the loaf, were subjected to double compression to 50% of their original height by a 25 mm diameter disk-shaped probe. The following parameters were determined: hardness (N), cohesiveness (-), chewiness (N), gumminess (N), elasticity (-), and springiness (-). The determination was performed in four replications [35].

2.2.8. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were calculated using Statistica v.13.3 (TIBCO Statistica Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The analysis of variance was performed using Duncan’s test at the confidence level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Chromatography Analysis of Chokeberry Fruits

Chokeberry fruits are rich in polyphenolic compounds like anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, flavanols, flavonols, and phenolic acids. Products derived from this fruit exhibit significant antioxidant and health benefits [6].

Tentative classification of polyphenols in chokeberry methanol-water extracts was performed using tandem mass spectrometry data for unsupervised prediction. The results are presented as the mean area percentage (%), providing a semi-quantitative overview of polyphenol classes. The concentration is given for a few compounds confirmed by standards and detected within the “anthocyanins” and “cinnamic acids and derivatives” classes (mg/100 g of dried fruit) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tentative classification of polyphenols in chokeberry methanol-water extracts.

Many studies report the chemical profile of chokeberry [36,37,38,39,40]. Gao et al. (2024) [37] report that Aronia melanocarpa contains phenolic acids, mainly chlorogenic acid and its isomer, neochlorogenic acid. The primary anthocyanins are cyanidin-3-O-galactoside and cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside. The flavonol group is chiefly represented by quercetin, which binds to various glycosides. Some studies also report the presence of isorhamnetin, eriodictyol, and kaempferol, as well as their glycosides. Comparing the concentrations of specific compounds to literature data is difficult because they depend on the cultivar [40], and the extraction method influences the phenolic profile [38,41]. The untargeted LC-MS analysis was conducted to illustrate the diversity and complexity of chokeberry extracts. The CANOPUS tool was employed to classify tandem mass spectra and assign them to compound classes based on the NPClassifier [25]. A total of 61 spectra were classified as polyphenolic compounds (Table 1). The quantification focused on the most abundant phenolic compounds, including chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, and anthocyanins (cyanidin-3-hexoside and cyanidin-3-pentosides). The most prevalent groups are flavonols, cinnamic acids and derivatives, and flavones. Although the groups that account for the most significant shares of the peak areas are cinnamic acids and derivatives, flavonols, flavonones, and anthocyanins. The area percentage is not directly comparable to absolute values expressed in mg/100 g of raw material due to the detector’s varied response; however, it allows a rough assessment of the shares of individual compound groups in the tested extract.

3.2. Baking Process and Quality Parameters of Wheat Bread

Table 2 presents the results of laboratory baking tests of wheat breads with chokeberry extracts.

Table 2.

Baking process and quality parameters of tested wheat breads with chokeberry fruit extracts.

Using chokeberry extract instead of water in the bread recipe had a significant (α = 0.05) impact on the baking process parameters such as oven loss, total baking loss, and bread yield (Table 2). However, use of chokeberry fruit extracts did not significantly affect (α = 0.05) the dough yield compared to the control sample (Table 2). The values of this parameter ranged from 157.5% for the sample 30%ChE0°Brix to 159.1% for the control sample and a sample with 30%ChE7.5°Brix. In the case of oven loss and total baking loss, the tested samples with chokeberry fruit extracts had lower values compared to the control sample (13.7% and 19.0%). These were from 5.9 to 4.3% lower values for oven loss and from 5.6 to 4.6% lower values for total baking loss (Table 2). There was no significant effect of the type (0 °Brix or 7.5 °Brix) of chokeberry fruit extract on the values of these parameters. Similar values of baking loss were noted by Wójcik et al. (2021) [42] for baking bread enriched with nettle infusions, in the range of 7.1–8.4%. In turn, Akbaş and Kılmaoğlu (2022) [43] reported an increase in baking losses value (from 14.10% for the control sample to 19.44% for the sample with sour cherry extract) for wheat breads with different fruit and vegetable extracts. In our study (Table 2), the bread with chokeberry fruit extracts had a higher bread yield than the control sample (128.9%). For breads with 0 °Brix chokeberry fruit extract bread yield ranged from 134.8 (30%ChE0°Brix) to 137.6% (10%ChE0°Brix), and for breads with 7.5 °Brix chokeberry fruit extract, this parameter ranged from 136.3% (15%ChE7.5°Brix) to 137.2% (20%ChE7.5°Brix). In relation to the literature data given by Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [44], our values of bread yield (Table 2) were lower. According to the cited authors, breads containing black chokeberry pomace powder achieved the bread yield value ranging from 137.8 to 144.1%.

Replacing water with chokeberry fruit extracts also had a significant effect on most of the quality parameters of the tested wheat bread (Table 2). It was noted that the most obtained values were influenced by both the type of chokeberry fruit extract (0 °Brix and 7.5 °Brix) and the percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe (10, 15, 20, 30% (m/m)). But the tested wheat breads with chokeberry fruit extracts had statistically (α = 0.05.) similar loaf volume, ranging from 609.2 (10%ChE7.5°Brix) to 665.0 cm3 (30%ChE0°Brix), where the loaf volume for the control sample was 638.3 cm3 (Table 2). Moreover, in our studies, it was observed that the use of chokeberry in the form of an aqueous extract in the bread recipe, in amounts of 10, 15, 20, and 30% m/m, contributed to an increase in the porosity of the crumb. Wójcik et al. (2021) [42] and Pycia et al. (2024) [45] noted lower values for wheat breads with ground ivy (from 470 to 530 cm3) or nettle infusions (from 317.5 to 385.4 cm3).

Meanwhile, the specific volume values differed significantly (Table 2). It was calculated values from 3.2 cm3/g for the control sample to 2.8 cm3/g for the sample with 10% 7.5°Brix chokeberry fruit extract. This indicates an adverse effect of replacing water with chokeberry fruit extract, especially at a concentration of 7.5 °Brix. Similar observations were reported by Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [15] for wheat bread with chokeberry pomace powder. The obtained bread volume values were from 338.3 to 237.9 cm3/100 g of bread. The bread volume reduction under the influence of various plant additives was also observed by other authors [35,44,46,47,48].

Xu et al. (2019) [49] confirmed in their review that adding phenolic compounds not only boosts antioxidants in bread but also affects the dough’s physicochemical properties and qualities through interactions with flour components. According to Xu et al. (2019) [49], Xu et al. (2021) [50] and Girard and Awika (2020) [51], the introduction of plant-based additives to wheat flour causes interactions between gluten proteins and the bioactive components of the added products (polyphenols, tannins, dietary fiber). Phenolic acids (PAs) interact with proteins and polysaccharides, affecting dough properties like elasticity and viscosity, ultimately influencing bread quality. During dough formation, proteins form an elastic gluten network maintained through intermolecular interactions. PAs can influence these interactions, thereby impacting dough characteristics and the final bread quality [52]. During kneading and dough rising, a loss of some proteins forming the gluten network is observed. As a result, gases produced during fermentation are not fully retained by the weaker gluten network, resulting in a low bread loaf volume. This is particularly true for phenolic compounds introduced with plant-based additives, as they interact with the thiol groups of gluten in wheat dough, weakening the gluten network that has been created. As a result, the bread’s volume decreases after baking [44]. Sun-Waterhouse et al. (2011) [53] also observed a decrease in free thiol groups in bread fortified with fruit polyphenols and examined how these polyphenols influence bread protein secondary structures. The enriched breads had lower specific volumes and a firmer crumb compared to the control, suggesting reduced gluten development. Ou et al. (2022) [54] suggest that this effect could be due to anthocyanins, which may interfere with disulfide bond formation in glutenin and gliadin. As reducing agents, anthocyanins might oxidize thiols in glutenin, thereby disrupting disulphide cross-links that are essential for gluten network formation. In our case, applying extracts to the dough resulted in improving the porosity of wheat bread samples. This suggests that aqueous chokeberry extracts might promote gas production and retention during proofing, leading to a higher porosity [3]. The use of chokeberry fruit extracts did not cause significant differences in the crumb moisture values (Table 2). It ranged from 43.2 (20%ChE7.5°Brix) to 45.1% (20%ChE0°Brix). Similar values of this parameter were noted by Wójcik et al. (2021) [42] and Pycia et al. (2024) [45]. In the case of bread acidity of tested samples (Table 2), a significant factor differentiating the samples was the type of chokeberry fruit extract (0 °Brix and 7.5 °Brix) and the percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe (10, 15, 20, 30% m/m). The control sample achieved a bread acidity of 1.55 acidity degrees. The samples with ChE 0 °Brix and ChE 7.5 °Brix had increasing values of this parameter with the increase in the percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe (Table 2). This was particularly visible in the results obtained for samples with 7.5 °Brix chokeberry fruit extract (ChE 7.5 °Brix), where the sample 10%ChE 7.5°Brix had an acidity of 1.75 acidity degrees and the sample 30%ChE 7.5°Brix—2.00 acidity degrees, respectively. This pattern of values could have been the reason for introducing an extract from a fruit with a high acidic content, such as chokeberry. Our obtained chokeberry extract samples had a pH 3.5. According to Kulling et al. (2008) [55], the pH of fresh chokeberry juice ranges from 3.3 to 3.9, with malic and citric acids as the main acids. This suggests high total acidity values.

3.3. TPC and Antioxidant Properties

Chokeberries are known for their various health benefits, which are rich in phenolic compounds, especially anthocyanins, and have antioxidant properties [4]. On the other hand, Maillard reaction products (e.g., melanoidin), which are formed during heat treatment or prolonged heating, are also responsible for the antioxidant properties of bread (mainly the crust) [56,57].

The content of TPC and antioxidant activity of enriched breads is presented in Table 3. Spectrophotometric analysis of bread crumbs for total polyphenol content showed that a higher proportion of chokeberry extract (30% m/m) in the samples resulted in higher TPC values (34.554 and 45.283 mgGAE/100 g). Furthermore, the extract with a 7.5 °Brix content contributed to this increase (Table 3). At the same time, these samples showed the highest antioxidant potential against ABTS+ and FRAP radicals. Polyphenols still retain their antioxidant activity in samples obtained at a baking temperature (200 °C), which is also supported by research from Szwajgier et al., 2020 [58], but, as mentioned before, melanoidin, which is formed during the Maillard reaction in the heat treatment, also has an impact on the antioxidant properties of bread samples [56,57].

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of bread samples.

Our TPC results and the antioxidant capacity values of the bread samples (Table 3) showed that breads containing extract with naturally occurring sugars (samples with 7.5 °Brix) were characterized by higher total polyphenol content and, therefore, higher antioxidant activity. Amino acids and reducing sugars are two important factors influencing the Maillard reaction [59]. The content of melanoidins formed during the Maillard reaction in bread can also be an indicator of its browning intensity. Other components of bread samples, such as substances contained in aronia, have a lesser effect in this case. Shen et al. (2018) [59] studied the antioxidant properties and activity of bread containing various sugars under different baking conditions. Their results showed that the antioxidant activity of bread increased with the addition of sugars and with baking time, temperature, and sugar amount. It should also be noted that, to a small extent, naturally occurring sugars in flour also contribute to the browning of bread [59].

3.4. Crust and Crumb Color Parameters of Wheat Breads

Table 4 presents the results of tests regarding the color of the tested wheat breads with chokeberry fruit extracts.

Table 4.

Color parameters of wheat bread with chokeberry fruit extracts.

The crumb color of the tested bread was significantly dependent on the type of chokeberry fruit extract (0 and 7.5 °Brix) and the percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe (10, 15, 20, and 30% m/m) (Table 4). The control sample crumb had a lightness range of 62.8. Due to the introduction of compounds from chokeberry extracts to the tested bread, and after their changes during dough fermentation processes and baking bread, the crumb color for finished bread was darker (maximum up to 51.5 for the 30% ChE 7.5° Brix) (Table 4). The value for parameter a* for the control sample and for the tested samples with 0 °Brix chokeberry fruit extract was 2.8. In turn, for samples with 7.5 °Brix chokeberry fruit extract, the gradual increase for this parameter was obtained (from 2.9 to 3.3). It indicates a slight increase in the red color for the tested bread crumb (Table 4). The crumb of control sample had a parameter b* value ranging from 20.3. The introduction of chokeberry extracts resulted in a decrease in the value of this parameter (from 17.6 to 9.0) (Table 4). A gradual change from light yellow to red in the color of bread crumbs was also caused by the increase in the percentage level of chokeberry fruit extracts. Similar values of bread crumb color parameters were noted by Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [15] for wheat bread with chokeberry pomace powder.

The color parameter values of the tested wheat bread crust were statistically significant different, in addition to the values obtained for parameter a* (Table 4). The control sample crust had lightness (L*) of 59.6, parameter a* (redness+/greenness) of 11.8, and parameter b* (yellowness+/blueness) of 31.1 (Table 4). The values of lightness (L*) of the samples with chokeberry fruit extracts decreased with the gradual increase in the percentage level of each type of extract (0 and 7.5 °Brix) tested (maximum up to 53.9 for the 30% ChE 7.5 °Brix). The chromaticity parameters (a* and b*) values showed the dominance of the yellow color component over the red in the crust color (Table 4). The values for parameter a* did not significantly change depending on the type of chokeberry fruit extract (0 °Brix and 7.5 °Brix) and the percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe (10, 15, 20, 30%). In turn, it was observed gradual decrease in the value of parameter b* was observed with increasing percentage level of replacing water in the bread recipe. For crust samples with ChE 0° Brix, it values were from 29.9 to 28.5, and for crust samples with ChE 7.5 °Brix, it values were from 28.1 to 24.4 (Table 4). It indicates a slight decrease in the yellow color. Similar values of crust color parameters were observed by Pycia et al. (2024) [45], Posadzka-Siupik et al. (2025) [35], and Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [15] for breads with plant-based additives.

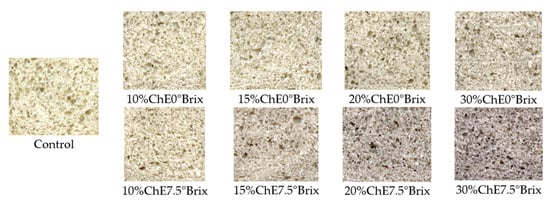

The obtained results for color parameters of wheat bread showed that the darkest bread crumb and crust colors were observed when an extract containing naturally occurring sugars was applied to the bread (Table 4, Figure 1). Removing sugars from the chokeberry extract resulted in no changes in the a* parameter values, compared to the control sample. It can be concluded that the increased red color in the bread was not due to the presence of chokeberry pigments, but rather to changes in the naturally occurring sugars in chokeberries during baking. Therefore, a small effect of anthocyanins on the color of bread was observed, and sugars play the dominant role in the tested samples. This could be the reason for Maillard reactions and caramelization occurring during bread baking [58,60].

Figure 1.

The appearance of the crumb of the tested wheat bread with chokeberry extracts.

3.5. Crumb Texture Parameters

Table 5 presents the results of the crumb texture parameters analysis of the tested wheat bread with chokeberry fruit extracts. The texture parameters of bread crumbs and their values are influenced by recipe ingredients, and the course of the dough fermentation and baking processes [49].

Table 5.

Crumb texture parameters of tested wheat breads with chokeberry fruit extracts.

The results (Table 5) showed a significant effect on the hardness, gumminess, elasticity, and springiness of the crumb due to replacing water in the bread recipe with chokeberry fruit extracts compared to the control sample. For the chewiness and cohesiveness of the crumb, there was no statistically significant effect (α = 0.05). The crumb of tested bread with the extracts was less elastic and more compact, as evidenced by lower values of the elasticity (by approx. 0.03 units) and higher values of hardness parameters (by approx. 4.00 N) compared to the control sample. Other authors also observed similar relationships within the crumb texture parameters [15,42,48]. The obtained results for crumb hardness (Table 5) are also confirmed by the observations recorded by Xu et al. (2019) [49]. These authors Xu et al. (2019) [49] concluded that the hardness of the bread crumb generally increases with the decrease in the volume of bread loaves. Several authors have also reported that partial substitution of wheat flour with powdered fruits or other plant-based additives leads to a weakening of the dough structure due to reduced carbon dioxide retention during dough fermentation, which results in a reduction in the volume of the bread loaf [61], and negatively affects the bread crumb texture, particularly in terms of hardness [45,47].

4. Conclusions

Chokeberry fruit is a rich source of health-promoting compounds and has one of the highest antioxidant capacities among fruits. However, in addition to phenolic compounds, it also contains sugars. In an era when obesity is a disease of civilization, designing foods with reduced sugar content is crucial. Therefore, this study aimed to introduce aqueous extracts of chokeberry fruit, rich in phenolic compounds, obtained through alcohol extraction, into bread recipes. Given that chokeberries are a source of sugar, which will also increase their content in the proposed product (wheat bread), two types of extract were obtained: one without (0 °Brix) and one with (7.5 °Brix) sugars.

The obtained chokeberry extract contributed to the enrichment of the wheat bread in total polyphenol content and the antioxidant capacity. Additionally, breads with chokeberry extracts were characterized by the same dough yield and loaf volume of bread compared to the control sample, but with changed oven loss, total baking loss, bread yield, specific volume, bread acidity, and porosity of the crumb. However, there was no statistically significant effect on the chewiness and cohesiveness of the crumb in the sample texture. A small effect of aronia pigments on the color of bread was observed, and sugars played the dominant role in the tested samples.

The presented research provides a general overview for bread producers, for example, regarding the quality of baked goods enriched with bioactive compounds. It also demonstrates how a small amount of naturally occurring simple sugars contained in the raw material can alter the product’s organoleptic properties. Furthermore, the presence of sugars in the finished product will also be important from a nutritional perspective. Chokeberries in the form of an extract, added to wheat bread, can be an excellent ingredient because of their role in the prevention and treatment of various chronic human diseases, and because they have a positive impact on the technological parameters of the product.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.; methodology, G.A., Z.P.-S. and A.S.; formal analysis, G.A., Z.P.-S., I.B. and A.S.; investigation, G.A.; resources, G.A., Z.P.-S., A.S. and I.B.; data curation, G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., Z.P.-S. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, G.A. and P.Ł.K.; visualization, G.A. and P.Ł.K.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, G.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. and P.Ł.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is financed by the program of the Minister of Education and Science named “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in the years 2019–2023, project number 026/RID/2018/19, the amount of financing PLN 9 542 500.00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jakubczyk, T.; Haber, T. Analiza zbóż i Przetworów Zbożowych: Praca Zbiorowa, Wyd. 2 popr.; Skrypty Szkoły Głównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego Akademii Rolniczej w Warszawie; SGGW-AR: Warszawa, Poland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N.; Sheidaei, Z.; Khorshidian, N.; Nematollahi, A.; Khanniri, E. Sensory Attributes of Wheat Bread: A Review of Influential Factors. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wei, X.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wakisaka, M.; Fang, W. Effects of heterotrophic Euglena gracilis powder on dough microstructure, rheological properties, texture, and nutritional composition of steamed bread. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawer, I.; Eggert, P.; Hołub, B. Aronia. Superowoc; Wektor: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ochmian, I.; Grajkowski, J.; Smolik, M. Comparison of Some Morphological Features, Quality and Chemical Content of Four Cultivars of Chokeberry Fruits (Aronia melanocarpa). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2012, 40, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Black Chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa L.—A Qualitative Composition, Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolić, M.T.; Marković, K.; Vahčić, N.; Samarin, I.R.; Mačković, N.; Krbavčić, I.P. Polyphenolic Profile of Fresh Chokeberry and Chokeberry Products. Croat. J. Food Technol. Biotechnol. Nutr. 2018, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Myracle, A.D. Development and Evaluation of Kefir Products Made with Aronia or Elderberry Juice: Sensory and Phytochemical Characteristics. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Cușmenco, T.; Bulgaru, V. Quality Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Goat Milk Yogurt with Fruits. Ukr. Food J. 2020, 9, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkova, T.; Odarchenko, A.; Silchenko, K.; Danylenko, S.; Verbytskyi, S.; Heida, I.; Kalashnikova, L.; Dmytrenko, A. Effect of Herbal Extracts Upon Enhancing the Quality of Low-Fat Cottage Cheese. Innov. Biosyst. Bioeng. 2023, 7, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sady, S.; Sielicka-Różyńska, M. Quality Assessment of Experimental Cookies Enriched with Freeze-Dried Black Chokeberry. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2019, 18, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Mironeasa, S.; Sturza, R. Aronia Extracts in the Production of Confectionery Masses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, M.; Đurović, I.; Miletić, N.; Radovanović, J. Effect of Convective Drying Method of Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa L.) on Drying Kinetics, Bioactive Components and Sensory Characteristics of Bread with Chokeberry Powder. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2019, 63, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, V.; Petković, M.; Filipović, J.; Đurović, I.; Miletić, N.; Radovanović, J.; Filipović, I. Nutritional Attributes of Wheat Bread Fortified with Convectively Dried Chokeberry Powder. Acta Agric. Serbica 2021, 26, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Parol-Nadłonek, N.; Kalisz, S.; Krajewska, A.; Stępniewska, S. Wheat Bread Enriched with Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa L.) Pomace: Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszuba, J.; Moszkowicz, A.; Adamczyk, G. Badania Jakości i Trwałości Ciastek Biszkoptowych Wzbogaconych Proszkiem z Owoców Aronii. Przegląd Zbożowo-Młynarski 2024, 6, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszuba, J.; Moszkowicz, A.; Adamczyk, G. Porównanie Jakości Ciastek Biszkoptowych Wzbogaconych Proszkiem z Owoców Aronii Przechowywanych Zamrażalniczo. Przegląd Zbożowo-Młynarski 2025, 1, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.; Lowe, T.; Campbell, G.M.; Withers, P.J.; Martin, P.J. Effect of sugar on bread dough aeration during mixing. J. Food Eng. 2015, 150, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.C.; Nguyen, H.; Li, Q.; Schönlechner, R.; Miescher Schwenninger, S.; Wismer, W.; Gänzle, M. Enzymatic and microbial conversions to achieve sugar reduction in bread. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Tanaka, A. Chemical Components and Characteristics of Black Chokeberry. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 48, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotkiewicz, A.; Jaremicz, Z.; Luczkiewicz, M. Aronia Plants: A Review of Traditional Use, Biological Activities, and Perspectives for Modern Medicine. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, M.; Dorna, H.; Szopińska, D.; Krzesiński, W.; Szwengiel, A. Grapefruit Extracts and Black Chokeberry Juice as Potential Antioxidant and Antifungal Agents for Carrot Seed Treatment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Fleischauer, M.; Ludwig, M.; Aksenov, A.A.; Melnik, A.V.; Meusel, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. SIRIUS 4: A Rapid Tool for Turning Tandem Mass Spectra into Metabolite Structure Information. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dührkop, K.; Nothias, L.-F.; Fleischauer, M.; Reher, R.; Ludwig, M.; Hoffmann, M.A.; Petras, D.; Gerwick, W.H.; Rousu, J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Systematic Classification of Unknown Metabolites Using High-Resolution Fragmentation Mass Spectra. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Wang, M.; Leber, C.A.; Nothias, L.-F.; Reher, R.; Kang, K.B.; Van Der Hooft, J.J.J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Gerwick, W.H.; Cottrell, G.W. NPClassifier: A Deep Neural Network-Based Structural Classification Tool for Natural Products. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, G.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Bobel, I.; Szwengiel, A.; Krystyjan, M. Effect of Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) Extracts on the Physicochemical Properties of Wheat Starch Pastes and Gels Stored Under Refrigerated Conditions. Molecules 2025, 30, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Method 10-05.01; Approved Methods of Analysis. Guidelines for Measurement of Volume by Rapeseed Displacement, 11th ed. AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010.

- Method No. 44-15.02; Approved Methods of Analysis. Guidelines for Measurement of Moisture Content—Air Oven Methods, 11th ed. AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010.

- Broeke, J.; Pérez, J.M.M.; Pascau, J. Image Processing with ImageJ: Extract and Analyze Data from Complex Images with ImageJ, the World’s Leading Image Processing Tool, 2nd ed.; Community Experience Distilled; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petrusha, O.; Daschynska, O.; Shulika, A. Development of the Measurement Method of Porosity of Bakery Products by Analysis of Digital Image. TAPR 2018, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, H.A.; Navaratne, S.B.; Navaratne, C.M. Porous crumb structure of leavened baked products. Int. J. Food Sci. 2018, 2018, 8187318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadzka-Siupik, Z.; Kaszuba, J.; Kapusta, I.T.; Jaworska, G. Wheat–Oat Bread Enriched with Beetroot-Based Additives: Technological and Quality Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudonné, S.; Dubé, P.; Anhê, F.F.; Pilon, G.; Marette, A.; Lemire, M.; Harris, C.; Dewailly, E.; Desjardins, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Phenolic Compounds and Abscisic Acid Profiles of Twelve Native Canadian Berries. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 44, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Shu, C.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Lang, Y.; Jin, C.; Cui, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Polyphenol Components in Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) as Clinically Proven Diseases Control Factors—An Overview. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1152–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, A.; Porcedda, S.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Nieddu, M.; Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Rosa, A. Chemical Composition, Nutritional, and Biological Properties of Extracts Obtained with Different Techniques from Aronia melanocarpa Berries. Molecules 2024, 29, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Weever, F.; Hübner, F.; Humpf, H.-U.; Esselen, M. Characterization of Oligomeric Proanthocyanidin-Enriched Fractions from Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliott via High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Investigations on Their Inhibitory Potential on Human Topoisomerases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11053–11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubra Sasmaz, H.; Kilic-Buyukkurt, O.; Selli, S.; Bouaziz, M.; Kelebek, H. Antioxidant Capacity, Sugar Content, and Tandem HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS Profiling of Phenolic Compounds from Aronia melanocarpa Fruits and Leaves (Nero and Viking Cultivars). ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14963–14976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petreska Stanoeva, J.; Balshikevska, E.; Stefova, M.; Tusevski, O.; Simic, S.G. Comparison of the Effect of Acids in Solvent Mixtures for Extraction of Phenolic Compounds From Aronia melanocarpa. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20934675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Różyło, R.; Łysiak, G.; Kulig, R.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G. Textural and Sensory Properties of Wheat Bread Fortified with Nettle (Urtica dioica L.) Produced by the Scalded Flour Method. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaş, M.; Kılmaoğlu, H. Evaluation of The Effects of The Use of Vegetable and Fruit Extracts on Bread Quality Properties. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 1838–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Sułek, A.; Wójcik, M.; Krajewska, A. Dandelion Flowers as an Additive to Wheat Bread: Physical Properties of Dough and Bread Quality. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pycia, K.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Posadzka, Z.; Kaszuba, J. Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea L.) as an Innovative Additive for Enriching Wheat Bread: Study on Flour Fermentation Properties, Dough Rheological Properties and Bread Quality. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziki, D.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Sułek, A.; Kocira, S.; Biernacka, B. Effect of Moldavian Dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) Leaves on the Baking Properties of Wheat Flour and Quality of Bread. CyTA-J. Food 2019, 17, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Różyło, R.; Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Sułek, A.; Biernacka, B. Cistus incanus L. as an Innovative Functional Additive to Wheat Bread. Foods 2019, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G.; Posadzka, Z.; Witczak, T.; Witczak, M. Comparison of the Rheological Behavior of Fortified Rye–Wheat Dough with Buckwheat, Beetroot and Flax Fiber Powders and Their Effect on the Final Product. Foods 2023, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y. Dough properties, bread quality, and associated interactions with added phenolic compounds: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 52, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, W. Influence of Antioxidant Dietary Fiber on Dough Properties and Bread Qualities: A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 80, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.L.; Awika, J.M. Effects of Edible Plant Polyphenols on Gluten Protein Functionality and Potential Applications of Polyphenol–Gluten Interactions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2164–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schefer, S.; Oest, M.; Rohn, S. Interactions between phenolic acids, proteins, and carbohydrates—Influence on dough and bread properties. Foods 2021, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Sivam, A.S.; Cooney, J.; Zhou, J.; Perera, C.O.; Waterhouse, G.I.N. Effects of added fruit polyphenols and pectin on the properties of finished breads revealed by HPLC/LC-MS and Size-Exclusion HPLC. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3047–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.J.L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, M.H. Effects of anthocyanins on bread microstructure and their combined impact on starch digestibility. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulling, S.E.; Rawel, H.M. Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa)—A Review on the Characteristic Components and Potential Health Effects. Planta Medica 2008, 74, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarría, A.P.; Pagán, J.; Ibarz, A. Melanoidins Formed by Maillard Reaction in Food and Their Biological Activity. Food Eng. Rev. 2012, 4, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesias, M.; Morales, F.J. Acrylamide in bakery products. In Acrylamide in Food: Analysis, Content and Potential Health Effects; Gökmen, V., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Szwajgier, D.; Paduch, R.; Kukuła-Koch, W.; Polak-Berecka, M.; Waśko, A. Study on Biological Activity of Bread Enriched with Natural Polyphenols in Terms of Growth Inhibition of Tumor Intestine Cells. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, Y. Bread characteristics and antioxidant activities of Maillard reaction products of white pan bread containing various sugars. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 95, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Jusoh, Y.M.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A.; Abdul Rahman, R. Bread Crust Thickness Measurement Using Digital Imaging and L*a*b Colour System. J. Food Eng. 2009, 94, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguchi, M.; Tabara, A.; Fukawa, I.; Ono, H.; Kumashiro, C.; Yoshino, Y.; Kusunose, C.; Yamane, C. Effects of Size of Cellulose Granules on Dough Rheology, Microscopy, and Breadmaking Properties. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, E79–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).