Abstract

With the advancement of precision agriculture, improving the operational accuracy of agricultural machinery has received increasing attention. The rice transplanter is crucial in this context, as its performance directly affects rice yield. During operation, both the magnitude and stability of the driving wheel slip ratio affect the accuracy of plant spacing, thereby influencing rice yield. However, to date, no control method that can simultaneously stabilize the speed, reduce the slip ratio, and improve the stability of the slip ratio has been proposed for transplanters. To address this issue, this paper proposes a joint speed–slip ratio control method based on an adaptive Student t-kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter (ASMCKF) and sliding mode control (SMC). First, a Student t-kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter (SMCKF) is designed to identify the transplanter’s speed, wheel speed, traction force, and rolling resistance in real time, thereby enhancing control system robustness against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in paddy fields. An adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method is also introduced for the SMCKF to increase the sensitivity of the cost function to variations in the system state, thereby further improving parameter identification accuracy. Building on this, a joint speed–slip ratio control method is designed based on SMC. Simulation results confirm that the ASMCKF achieves higher identification accuracy than conventional methods when facing non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise. Field experiment results show that the proposed method can effectively stabilize the transplanter’s speed while significantly reducing the slip ratio and improving the stability of the slip ratio.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of precision agriculture, improving the operational accuracy of agricultural machinery has become increasingly important. Among these machines, the rice transplanter plays a crucial role in rice planting, where the accuracy of plant spacing directly affects rice yield [1]. This relationship is supported by a study on Liangyou 6326 rice, which found that reducing plant spacing from 14.1 cm to 12.4 cm resulted in a 3.4% decrease in the final yield [2]. Currently, rice transplanters are generally equipped with multiple plant spacing settings to accommodate different rice varieties. However, the influence of driving wheel slip on actual plant spacing has not been adequately considered. When a rice transplanter operates at a constant speed in paddy fields, variations in soil parameters, sinkage depth, and water depth cause significant fluctuations in the traction force and rolling resistance acting on the driving wheels. Consequently, the driving wheel slip ratio exhibits significant fluctuations, typically ranging between 0 and 0.3 [3]. Since the transmission ratio between the driving wheel and the planting arm is fixed for a given plant spacing setting, varying slip ratios during operation lead to inconsistent plant spacings. Thus, slip ratio fluctuations prevent precise plant spacing control. Therefore, during constant-speed operation of the rice transplanter, reducing the slip ratio and its fluctuations is of great significance for achieving precise and quantitative rice planting and even improving rice yield.

Based on the above analysis, the objective of the longitudinal control for the rice transplanter is to stabilize the speed while reducing the slip ratio and improving the stability of the slip ratio. At present, proportional–integral–derivative (PID) algorithms [4,5,6] can meet the accuracy requirements for speed control in road vehicles and agricultural vehicles, including rice transplanters. However, in rice transplanter automation, no speed control method has been proposed that simultaneously reduces the slip ratio and improves slip ratio stability. For slip ratio control, the objectives in road vehicles are generally to improve the tire’s coefficient of adhesion, thereby improving the vehicle’s acceleration performance [7,8,9]. The study in [10] built a traction control system (TCS) with conditional integral-error sliding mode control (CSMC) and a dual-mode coupling drive system (DMCDS). The study in [11] proposed a drive anti-slip controller integrating MPC and SMC for corner-modular electric vehicles, achieving coordinated drive-suspension control on low-traction surfaces. In agricultural vehicles, the objectives of slip ratio control are generally to improve traction performance [12,13]. The study in [14] used ploughing depth as the control variable to regulate the slip ratio based on sliding mode control (SMC), thus improving the tractor’s traction efficiency. The study in [15] used the displacement of the sliding battery pack as the control variable to control the slip ratio without changing the ploughing depth, ensuring both increased work efficiency and ploughing depth uniformity. In the aforementioned studies, since the objectives of slip ratio control are to improve the acceleration performance of road vehicles or the traction performance of agricultural vehicles, the desired slip ratios are set to constant values close to the peak slip ratio, such as 0.2, under which the traction force can overcome not only the rolling resistance of the wheels but also the acceleration resistance or ploughing resistance. However, rice transplanters generally operate at constant speed, and the resistance of their planting implements can be approximately neglected. Moreover, the focus of the rice transplanter is on ensuring planting accuracy rather than acceleration performance or traction efficiency. Therefore, the desired slip ratio for rice transplanters should be set as low as possible, rather than close to the peak slip ratio. Additionally, considering the large variations in the rolling resistance of wheels in paddy fields, and there is no sliding battery pack or working mechanism with adjustable operating depth in conventional rice transplanters, to ensure relative stability of the transplanter’s speed, the desired slip ratio will inevitably fluctuate. The study in [16] minimized the desired slip ratio while ensuring that the tractor’s traction force could overcome all resistances in real time, effectively keeping speed stable and improving the tractor’s traction efficiency. However, the real-time variations in resistances ultimately result in a wide fluctuation in the slip ratio. In summary, no control algorithm has yet been proposed for transplanters that can simultaneously stabilize speed, reduce the slip ratio, and improve slip ratio stability.

In addition, the paddy field condition parameters, such as soil parameters, wheel sinkage depth, and water depth, fluctuate significantly [17], and the hard bottom layer is uneven [18]. Therefore, the robustness of the longitudinal control system is particularly important for transplanters. In the aforementioned studies, scholars commonly used SMC to control the slip ratio, which exhibits strong robustness. However, the performance of SMC depends on the accuracy of model parameters. Compared to paved roads and dry fields, the paddy field environment introduces more significant noise, making it challenging to obtain accurate dynamic model parameters of the rice transplanter. For parameter identification problems in environments with significant noise, the Kalman filter [19] is often applied. However, the Kalman filter and many of its derived algorithms [20,21,22] assume that noise follows the Gaussian distribution. In many practical applications, noise does not follow the Gaussian distribution, particularly when measuring the dynamic parameters of a rice transplanter in a paddy field. In such a case, the noise typically exhibits heavy-tailed characteristics. In recent years, the correntropy [23,24,25], as a new similarity measure, has demonstrated strong noise suppression capability for non-Gaussian noise, without strict limitations on noise distribution. Therefore, as the demand for improving the robustness of Kalman filters against non-Gaussian noise increases, research on the maximum relevant entropy Kalman filter (MCKF) has gradually increased. The MCKF achieves more robust parameter identification by optimizing the maximum posterior cost function, defined using a Gaussian kernel function. However, parameter identification accuracy in MCKF is largely influenced by the kernel bandwidth. Smaller kernel bandwidths result in higher identification accuracy but slower convergence, while larger kernel bandwidths result in faster convergence but with robustness similar to the conventional Kalman filter [26,27]. As a result, many scholars have studied MCKF with an adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method (AMCKF) [28,29,30], with the general idea being to increase the kernel bandwidth as the error increases, to enhance the tracking performance of MCKF. However, the above research has primarily utilized the Gaussian kernel. Student’s t-kernel has a stronger ability to capture non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise than the Gaussian kernel. Its integration into MCKF can further enhance the algorithm’s robustness to non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise. Therefore, the study in [31] proposed an MCKF based on Student’s t-kernel (SMCKF). Experiments have verified that the SMCKF achieves higher parameter identification accuracy compared to MCKF when facing non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise. At the same time, considering that the SMCKF with fixed kernel bandwidth also faces the same issue as the MCKF with fixed kernel bandwidth, the study in [31] also proposed an adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method for the SMCKF using the interacting multiple model (IMM) algorithm, thereby forming IMM-SMCKF, which further enhanced the parameter identification accuracy of SMCKF. This method is more suitable for identifying the dynamic parameters of the rice transplanter in paddy fields. However, the IMM-based adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method relies on empirical knowledge and requires tuning effort. Specifically, several parameters need to be manually set, including the kernel bandwidths for each sub-filter, the initial Markov transition probability matrix between sub-filters, the initial model probabilities, and the total number of models in the IMM framework.

In summary, to simultaneously stabilize the speed of the rice transplanter, reduce the slip ratio, and improve the stability of the slip ratio, thereby improving operational accuracy, this paper proposes a method for identifying the longitudinal dynamic parameters of the transplanter based on ASMCKF (adaptive Student’s t-kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter), and a speed–slip ratio joint control method based on SMC, thereby forming the joint speed–slip ratio control method for rice transplanters based on the ASMCKF and SMC. The ASMCKF incorporates a novel adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method for the SMCKF. The core of this method is an update rule derived directly from the derivative of the cost function, with the explicit objective of increasing its sensitivity to state variations. This provides a principled theoretical foundation for the adaptation mechanism. In practical terms, the implementation is lightweight, introducing only a single adaptive formula and one additional parameter, which results in low dependence on empirical knowledge and eliminates the need for extensive parameter tuning. Finally, simulation experiments demonstrate that the proposed ASMCKF effectively enhances the tracking performance of SMCKF and exhibits greater robustness against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise compared to conventional parameter identification algorithms. Additionally, field experiments validate the accuracy and effectiveness of the proposed joint speed–slip ratio control method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Platform

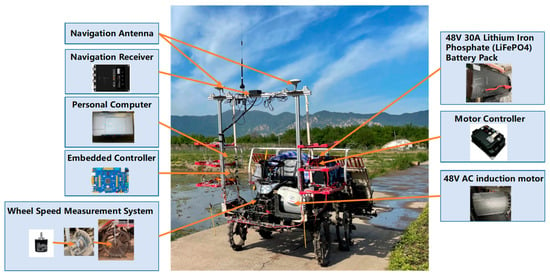

The test platform is a modified Yanmar VP6E rice transplanter (Yanmar Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), as shown in Figure 1. To achieve more precise control, the original gasoline engine was replaced with a 48 V AC induction motor (SME Group, Cusago, Italy), powered by a 48 V 30 A lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) battery pack. The motor controller regulates the drive torque of the motor. Additionally, the navigation system and control system were integrated. The navigation system (CHC (R) CGI-610), which consists of navigation antennas and a navigation receiver, has a speed accuracy of ±0.02 m/s. In the control system, a personal computer (Processor: Intel (R) Core (TM) i5-9300H CPU @ 2.40 GHz) is developed using Matlab/Simulink (R2016a) and communicates with the embedded controller via the serial protocol. It operates at a frequency of 5 Hz, receives the transplanter’s speed and wheel speed data sent by the embedded controller, calculates the desired motor torque based on the control algorithm, and sends the desired motor torque to the embedded controller. The embedded controller is an STM32F407 microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland), which also operates at a frequency of 5 Hz. It receives the encoder pulse signals from the wheel speed measurement system and calculates the wheel speed, obtains the speed data from the navigation system via the serial protocol, and communicates with the motor controller via the CAN bus to send the desired motor torque and read the actual motor torque. The wheel speed measurement system is installed on the right rear wheel of the transplanter, with an Omron E6B2-CWZ6C incremental photoelectric rotary encoder (Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan)as the sensor, which has a resolution of 1000 P/R.

Figure 1.

The modified Yanmar VP6E rice transplanter.

2.2. Longitudinal Dynamic Model of the Rice Transplanter

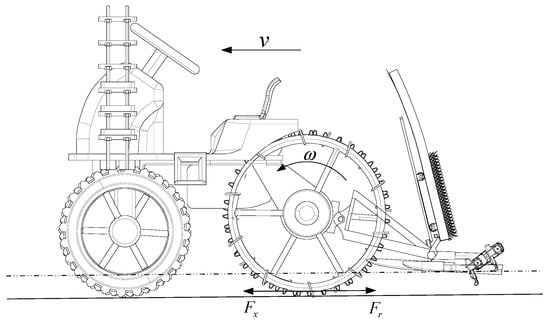

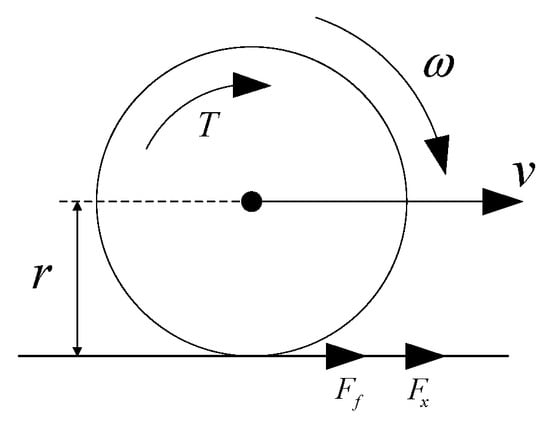

Before performing longitudinal control of the rice transplanter, it is necessary to establish the longitudinal dynamic model of the transplanter. The rice transplanter is a four-wheel-drive vehicle. In this study, to simplify the study, it is assumed that the road conditions are identical for all four wheels. Subsequently, the control algorithm is studied using a quarter-transplanter model corresponding to the right rear driving wheel. In the model, the effects of paddy field hardpan undulations, air resistance, and slope resistance are neglected. Additionally, since the contact area between the transplanter’s working implement and the paddy soil is relatively small, the resistance of the working implement is also neglected. Under the above assumptions, the longitudinal dynamic model of the transplanter is depicted in Figure 2, with the dynamic equation for the quarter-transplanter expressed in Equation (1), where is the speed, is the mass of the quarter-transplanter model, is the traction force of the driving wheel, and is the rolling resistance of the driving wheel. The driving wheel rotational model is shown in Figure 3, with its corresponding equation expressed in Equation (2), where is the driving torque of the driving wheel, is the rolling radius of the driving wheel, is the driving wheel speed, and is the moment of inertia of the driving wheel. Additionally, the driving wheel’s slip ratio is given by Equation (3). Besides, for the transplanter used as the test platform in this paper, , = 224 kg, and r = 0.425 m.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal dynamic model of rice transplanter, where the dashed line at the bottom represents the water layer in the paddy field, and the solid line beneath it denotes the hard bottom layer.

Figure 3.

Rotational model of the drive wheel.

2.3. Parameter Identification Method Based on ASMCKF

The complex non-Gaussian noise in paddy fields generally exhibits a heavy-tailed distribution; this can lead to significant errors in the identification of the transplanter’s longitudinal dynamic parameters when using KF and its derivatives, which assume noise follows the Gaussian distribution. Consequently, the control accuracy of the transplanter’s longitudinal speed and slip ratio will be reduced. Therefore, based on the model in the previous section, an ASMCKF-based identification method for the transplanter’s longitudinal dynamic parameters is proposed, which is robust to the complex non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in paddy fields. This method identifies the transplanter’s speed, driving wheel speed, driving force, and rolling resistance, providing reliable support for subsequent precise joint speed–slip ratio control. This section first establishes the system equations for parameter identification. On this basis, the standard SMCKF is introduced. Subsequently, an adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method for SMCKF is proposed, thereby forming the ASMCKF.

2.3.1. System Equations

In the longitudinal control process of the transplanter, it is necessary to obtain real-time values of the speed, driving wheel speed, the traction force, and rolling resistance acting on the driving wheel. Among these, the speed and driving wheel speed can be observed through integrated navigation and wheel speed sensors, respectively. Therefore, the state vector and observation vector are defined, where the state vector and the observation vector .

Assuming that and remain constant within a single sampling period, and combining Equations (1) and (2), the state equation of the system is derived as follows:

The observation equation of the system is expressed as

Subsequently, assuming the system’s discrete time step is , leading to the discrete state equation and discrete observation equation as follows:

- (1)

- Discrete state equation

- (2)

- Discrete observation equation

2.3.2. SMCKF

The prediction process of the SMCKF is the same as that of the traditional Kalman filter, whereas the update process differs.

Specifically, the prediction process is given by

where is the priori estimate of the state vector at time step , is the posteriori estimate of the state vector at time step , is the priori error covariance at time step , is the error covariance at time step , and is the process noise covariance matrix.

In the update process, the maximum correntropy is introduced. Correntropy is a measure of the similarity between two random variables. For the random variables and with a joint probability density function , the definition of correntropy is given by

where is the mathematical expectation, and is the positive-definite Mercer kernel.

The traditional maximum correntropy Kalman filter (MCKF) typically uses the Gaussian kernel:

where is the kernel bandwidth.

Considering that the Student’s t-kernel function is more sensitive to the non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise characteristics than the Gaussian kernel, it is better at addressing the non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in the transplanter’s operation in paddy fields. Therefore, the following Student’s t-kernel function is chosen to replace the Gaussian kernel:

where is the degree of freedom.

Subsequently, the following cost function is defined to enhance the filter’s robustness and adaptability to non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise using Student’s t-kernel function:

where . is the observation noise covariance matrix.

The , representing the posterior estimation of the state vector at time step , should satisfy the following condition:

Considering that and all exhibit unimodal profiles, and the observation and the prior estimate are both close to the true state in practical applications, it can be approximately assumed that exhibits an unimodal profile.

Therefore, taking the derivative of with respect to , it can be derived that

Let ; thus,

By adding and subtracting on both sides, the following can be obtained:

At this point, an analytical solution of this equation is difficult to obtain. Therefore, a direct substitution based on the fixed-point form is performed by letting .

Thus, the update formula for can be obtained, as shown in Equation (18).

where .

Additionally, the prediction formula for the error covariance matrix in SMCKF is the same as that of the MCKF with a Gaussian kernel, which is given by

where is the identity matrix with the appropriate dimension.

It is worth noting that when the degree of freedom is fixed, the kernel bandwidth directly affects the parameter identification accuracy of the SMCKF. When is small, if the observed parameters undergo significant changes, will decrease significantly. In this case, the tracking performance of SMCKF will be poor. On the other hand, when is large, although the aforementioned issue is mitigated, the SMCKF will tend to behave similarly to the KF, thereby reducing its robustness advantage against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise [31]. Therefore, an adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method can be designed for the SMCKF to maintain robustness against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in the steady state while simultaneously improving tracking performance during significant variations in the observed parameters.

2.3.3. Adaptive Kernel Bandwidth Adjustment Method

To improve the tracking performance of SMCKF while maintaining its robustness, the kernel bandwidth can be adjusted to increase the sensitivity of the cost function to , where can reflect the magnitude of state variation. Therefore, under the approximation assumption , the derivative of with respect to is calculated as follows:

Subsequently, the adaptive kernel bandwidth at the step should optimize to be as small as possible. By analyzing , it can be observed that as approaches positive infinity or zero, approaches zero. Furthermore, it can be easily derived that has a unique stationary point. Therefore, by letting , the equation for calculating , which minimizes , can be expressed as follows:

It is worth noting that when , will become a constant value, and SMCKF will no longer be the maximum correntropy-based method. Therefore, a correction factor is introduced, and Equation (21) is adjusted into Equation (22):

where can theoretically be calculated by Silverman’s rule [30]. However, this method for calculating is based on the specific noise parameters being known, whereas the noise in practical applications is unknown and exhibits strong uncertainty. Therefore, in this study, based on experience, let . By the above method, the ASMCKF is formed, and it can achieve the following functions: when the error is large, it behaves like KF and can converge quickly to a value close to the true value; when the error is small, it behaves like SMCKF and exhibits strong robustness against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise. Notably, the core of the proposed algorithm is the kernel bandwidth adaptive adjustment formula shown in Equation (22), in which only is a newly introduced parameter, while all other parameters are inherited from the conventional SMCKF. Therefore, the proposed method does not significantly increase the computational complexity or parameter tuning effort.

2.4. Joint Speed–Slip Ratio Control Method Based on SMC

To stabilize the transplanter’s speed while reducing the slip ratio and improving the stability of the slip ratio, thereby enhancing the operational accuracy of the transplanter, this paper designs a joint speed–slip ratio control method based on SMC, using as the control variable. Specifically, independent controllers for the transplanter’s speed and slip ratio are first designed, followed by a control switching strategy.

2.4.1. Speed Controller Based on SMC

Sliding mode control (SMC) is a control method that drives the system’s state to a predefined sliding surface to ensure the system’s stability. It enhances the system’s robustness against uncertainties and disturbances by using a switching control law to keep the system on the sliding surface.

For the speed controller, first, the sliding surface is defined as

where the speed error , is the desired speed, and is the integral gain coefficient.

The control objective is to drive to approach 0 by controlling the control variable , thereby ensuring that the error exponentially converges to 0. Therefore, the switching control law is defined as

where is the sign function, and is the switching gain.

Since only excessively high speeds affect transplanting quality parameters such as plant depth, missed planting ratio, and seedling damage ratio, the accuracy requirement for speed control of the rice transplanter is not strict. Consequently, the speed only needs to remain stable within an acceptable range. Therefore, it is assumed that , and by combining Equations (2), (23) and (24), the control law for the transplanter’s speed can be derived, as shown in Equation (25).

where is the output of the speed controller.

2.4.2. Slip Ratio Controller Based on SMC

The design process for the slip ratio controller is the same as that of the speed controller, with the same sliding surface and switching control law. Therefore, by combining Equations (1)–(3), (23) and (24), the control law of the slip ratio controller can be derived as

where is the output of the slip ratio controller, the slip ratio error is , and is the desired slip ratio. In addition, considering that should be as small as possible to ensure that the actual plant spacing is close to the set plant spacing, but excessively, small slip ratio may result in insufficient traction force, is set to 0.05 in this study.

2.4.3. Control Switching Strategy

The transplanter’s speed and slip ratio cannot remain constant simultaneously during actual operation, as analyzed in the Introduction. Therefore, the proposed control method needs to regulate both within a certain range. Given that the primary objective of this study is to enhance the plant spacing accuracy of the transplanter, and that speed variations within a reasonable range have a minor impact on transplanting quality, as analyzed in Section 2.4.1, priority is given to stabilizing the slip ratio, while speed only needs to remain within an acceptable range.

Accordingly, the speed–slip ratio switching control strategy is designed as follows: first, the threshold range of the speed is defined as , where , . When , the control variable , otherwise, the control variable .

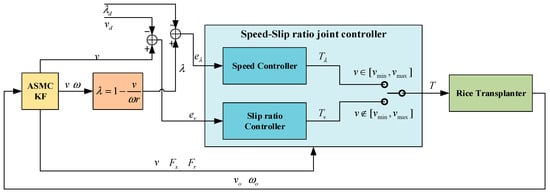

Finally, the overall control system scheme is shown in Figure 4, where is the observed speed, is the observed wheel speed. By this method, the stability of the transplanter’s speed and slip ratio can be guaranteed, and the slip ratio can be controlled close to a small value.

Figure 4.

The overall control system scheme.

2.5. Experimental Design

2.5.1. Comparative Simulation Study of Parameter Identification Algorithms

To verify the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed ASMCKF, a comparative simulation study was conducted to compare the parameter identification accuracy of the following algorithms: the conventional KF, the AMCKF proposed by the study in [30], the SMCKF, and the ASMCKF. Considering the strong coupling relationship among parameters in the transplanter’s longitudinal dynamic model is difficult to model accurately, this simulation study was designed to identify the speed and position of an object.

The state-space equation of the observed object was given as follows:

where , and represent the displacement and speed of the object at the step , respectively. The unit of is , the unit of is . The process noise followed a non-Gaussian heavy-tailed distribution and was generated as follows:

where .

The observation noise was also a non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise, and the noise was generated as follows:

where , was sequentially set to 100, 150, and 200 (the larger the value of , the heavier the tail of the noise distribution).

The true initial state of the observed object was set as , in order to clearly compare the tracking performance of the parameter identification algorithms, the initial states of the filters were all set as . Besides, the initial error covariance matrices of the filters were all set as . The process noise covariance matrices were all set as . The observation noise covariance matrices were all set as . The simulation time was set to 100 s, with a simulation step size of 1 s. Additionally, in the AMCKF, [30], where ; in the SMCKF, , ; in the ASMCKF, ,.

2.5.2. Field Experiment of Joint Speed–Slip Ratio Control

To verify the practical feasibility and effectiveness of the joint speed–slip ratio control method proposed in this paper, the modified electric rice transplanter described in Section 2.1 was used as the experimental platform for verification. During the experiment, the slip ratio under the pure speed control method was compared with that under the proposed joint speed–slip ratio control method. In the pure speed control method, the control variable was calculated based on Equation (25), and the parameter identification was performed using the conventional KF. At the same time, to further demonstrate the superiority of the ASMCKF algorithm proposed in this paper, the transplanter’s speed and slip ratio were controlled using the method described in Section 2.4, based on KF, AMCKF proposed by the study in [30], and ASMCKF, respectively. The initial states of the filters were all set as . The initial error covariance matrices were all set as . The process noise covariance matrices were all set as . The observation noise covariance matrices were all set as . In the AMCKF, , where ; in the AMCKF, , ; in the ASMCKF, , . In SMC, , . Besides, the frequencies for parameter identification and control are both 5 Hz. Notably, the computational burden of both the ASMCKF and SMC algorithms is negligible, as they rely on explicit analytical formulas rather than iterative optimization. This guarantees reliable real-time execution within the 200 ms control cycle on the experimental platform. The field experiments were conducted in a typical paddy field with significant variations in soil strength and a hard, uneven subsoil layer. During the experiments, the transplanter’s wheel sinkage depth varied between approximately 20 cm and 30 cm, and the water layer depth was maintained at approximately 2 cm, which meets the standards for rice transplanting [32]. These conditions created a challenging environment with non-uniform rolling resistance and significant disturbances for the control system. The plant spacing gear was set to 28 cm. At that time, the torque ratio between the drive motor and each rear drive wheel was 0.039; thus, the driving torque of the driving wheel can be adjusted by adjusting the driving torque of the drive motor. The desired speed of the transplanter was set to , , and , respectively. The desired slip ratio was set to 0.05 in each trial, as analyzed in Section 2.4.2. Finally, to ensure the reliability of the results, each method was tested in 10 independent trials. The experimental scenario is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Experimental scenario of joint speed–slip ratio control.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of the Simulation Study

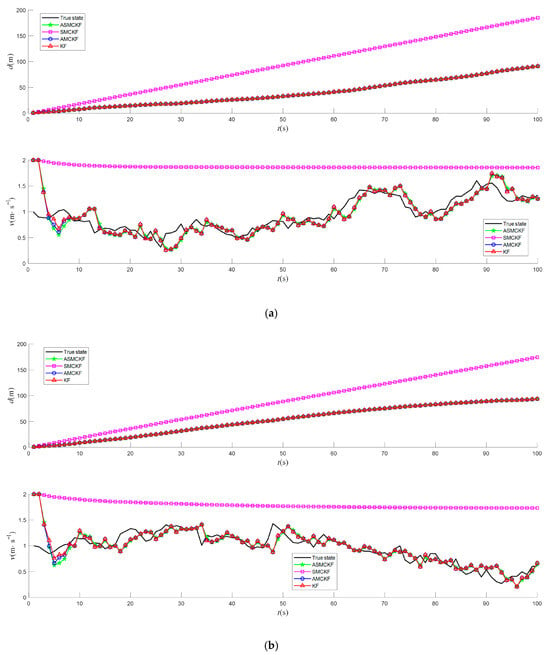

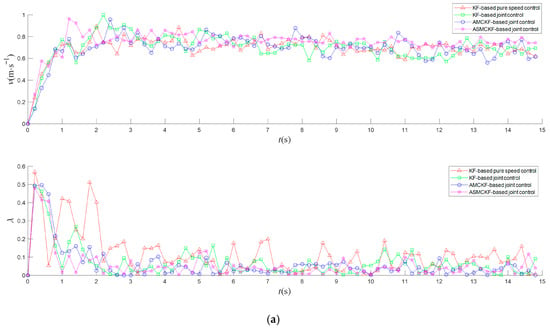

The identification results for different algorithms are shown in Figure 6. The corresponding mean squared errors (MSEs) are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Identification results of different algorithms under non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise: (a) curves of the displacement and speed when ; (b) curves of the displacement and speed when ; (c) curves of the displacement and speed when , where the black line represents the true state, green ☆ represents ASMCKF, magenta □ represents SMCKF, blue ○ represents AMCKF, red △ represents KF.

Table 1.

MSEs of the identification results of different algorithms.

Based on the simulation results, it can be observed that the proposed ASMCKF achieves higher parameter identification accuracy compared to the traditional KF, SMCKF, and AMCKF. Additionally, when significant discrepancies exist between and , the SMCKF fails to track the observed states effectively, resulting in substantial errors. In contrast, the adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method proposed in this study effectively addresses this issue. Furthermore, the simulation results indicate that when the noise distribution is less heavy-tailed, the parameter identification accuracy of the ASMCKF is comparable to that of traditional methods. However, as the tail of the noise distribution becomes heavier, the advantage of ASMCKF becomes more pronounced. Specifically, when , the MSE of displacement identified by ASMCKF is 0.0963 , and the MSE of speed is 0.1151 . Compared to AMCKF, the MSE of is reduced by 1.02%, and the MSE of is reduced by 1.46%; compared to KF, the MSE of is reduced by 5.68%, and the MSE of is reduced by 3.60%. When , the MSE of in ASMSCKF is 0.0905 , and the MSE of is 0.1240 . Compared to AMCKF, the MSE of is reduced by 6.22%, and the MSE of is reduced by 4.37%; compared to KF, the MSE of is reduced by 19.48%, and the MSE of is reduced by 10.28%. When , the MSE of in ASMCKF is 0.1319 , and the MSE of is 0.1053 . Compared to AMCKF, the MSE of is reduced by 10.64%, and the MSE of is reduced by 5.73%; compared to KF, the MSE of is reduced by 21.91%, and the MSE of is reduced by 12.90%.

Therefore, the proposed ASMCKF not only retains the strong robustness of the SMCKF against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise but also improves the tracking performance of SMCKF. These improvements indicate that the ASMCKF holds strong potential for accurate identification of the transplanter’s longitudinal dynamic parameters under paddy field conditions.

3.2. Results of the Field Experiment

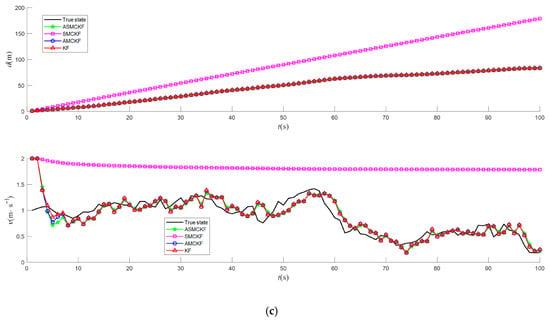

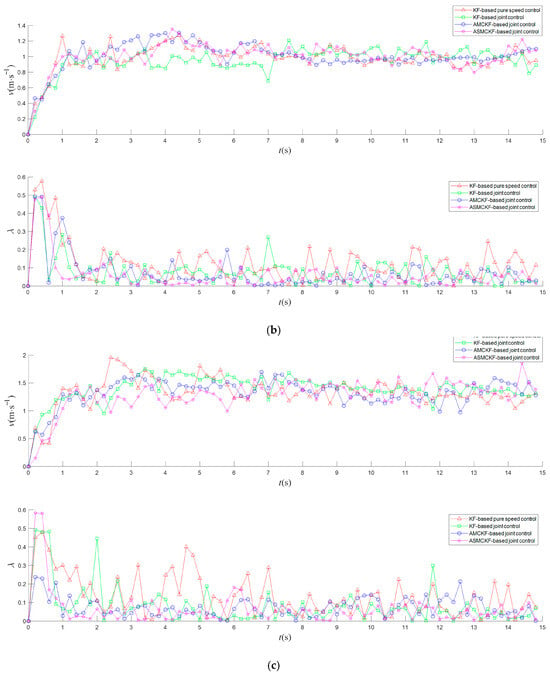

The statistical results of different control methods are shown in Table 2, which were obtained by taking the mean of the outcomes of the 10 independent trials. The speed and slip ratio variation curves presented in Figure 7 are representative of the results of one of the trials conducted.

Table 2.

Statistical summary of field experiment results.

Figure 7.

Field experiment results of different control methods for rice transplanters: (a) curves of speed and slip ratio when ; (b) curves of speed and slip ratio when ; (c) curves of speed and slip ratio when , where red △ represents the KF-based pure speed control, green □ represents the KF-based joint control, blue ○ represents AMCKF-based joint control, magenta ☆ represents ASMCKF-based joint control.

Based on the analysis of the experimental results, it can be concluded that, compared with pure speed control, the proposed joint speed–slip ratio control method can effectively reduce the slip ratio of the rice transplanter and improve slip ratio stability. Specifically, taking as an example, under the KF-based joint speed–slip ratio control, the mean of slip ratio is 0.081, and the MAE of is 0.028. Compared with the KF-based pure speed control, the mean of is reduced by 35.20%, and the MAE of is reduced by 60.56%. Furthermore, when the parameter identification algorithm is based on the maximum correntropy, the robustness of the control systems to non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in paddy fields is enhanced, further improving the effect of reducing the slip ratio and improving the stability of the slip ratio. Among these algorithms, the effect of the proposed ASMCKF is the most significant. Specifically, taking as an example, under the proposed ASMCKF, the mean of is 0.062, and the MAE of is 0.009. Compared with AMCKF, the mean of is reduced by 11.43%, and the MAE of is reduced by 57.14%. Compared with the conventional KF, the mean of is reduced by 23.46%, and the MAE of is reduced by 67.86%. Therefore, the proposed ASMCKF effectively improves the accuracy of slip ratio control for rice transplanters, compared to AMCKF and KF. This is because the proposed ASMCKF has stronger robustness and maintains good tracking performance under non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in paddy fields.

Additionally, the experimental results show that after integrating slip ratio control into speed control, the proportion of speed maintained within the threshold range can still exceed 75%, ensuring strong speed stability. This is because, although slip ratio control frequently interrupts speed control, as can be seen from Equations (25) and (26), both and contain , which occupies a significant proportion of the control variable and can be regarded as a large feedforward control variable. According to the proposed speed–slip ratio switching control strategy, in each control process, the speed is controlled first, and when the speed reaches the threshold range, the control switches between speed control and slip ratio control. At this stage, the control variable consistently contains the large feedforward term with relatively small fluctuations. As a result, the motion state of the rice transplanter generally does not undergo significant variations. Therefore, the speed of the rice transplanter remains stable within the desired range most of the time. Additionally, due to the reduction and stabilization of the slip ratio, the traction efficiency will not experience excessive reduction caused by excessive wheel slip, thereby achieving a good speed control performance.

Beyond the above analysis, the observed reduction in the mean slip ratio from approximately 0.12 to 0.06 holds direct practical implications for field operations. This enhancement significantly minimizes random plant spacing errors, thereby improving planting uniformity—a key agronomic factor for optimizing yield.

4. Conclusions

During rice transplanter operation, the magnitude and stability of the driving wheel slip ratio affect the accuracy of plant spacing, thereby influencing rice yield. Currently, no control method has been proposed for the transplanter that can simultaneously stabilize the speed, reduce the driving wheel slip ratio, and improve slip ratio stability. To address this issue, a joint speed–slip ratio control method based on adaptive Student t-kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter (ASMCKF) and sliding mode control (SMC) is proposed. The main contributions are as follows:

- An adaptive Student t-kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter is employed to identify the speed, wheel speed, traction force, and rolling resistance of the transplanter in real time, where an adaptive kernel bandwidth adjustment method is proposed, which optimizes the kernel bandwidth along the direction of increasing sensitivity of the cost function to state variations, to further improve identification accuracy. It can enhance the robustness of the control system against non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise in paddy fields.

- A joint speed–slip ratio control method is designed based on SMC, incorporating independent controllers for speed and slip ratio, as well as a control switching strategy between speed control and slip ratio control.

- Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed ASMCKF achieves higher identification accuracy than conventional methods and exhibits stronger robustness when facing non-Gaussian heavy-tailed noise.

- Field experiment results show that the proposed joint speed–slip ratio control method based on ASMCKF and SMC can effectively stabilize the transplanter’s speed while significantly reducing the driving wheel slip ratio and improving slip ratio stability. This advancement directly enhances planting uniformity, which can improve the precision and quality of rice transplanting.

Future work will focus on the optimization of SMC in the joint control method. The SMC used in this study, while robust, inherently produces chattering with a certain amplitude. As the impact of this chattering amplitude was indistinguishable from environmental disturbances in our field tests, its practical effect remains unquantified. Therefore, we will conduct a comparative study by implementing SMC variants —such as higher-order sliding mode control and boundary layer approaches— known for achieving lower-amplitude chattering. This will definitely determine if reducing chattering amplitude yields tangible performance gains. Moreover, the controller parameters for slip ratio and speed control will be carefully determined for each based on its specific control requirements, thereby further improving the control accuracy of the transplanter’s speed and slip ratio.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and R.C.; methodology, Y.M. and B.Z.; software, Y.M. and B.Z.; validation, Y.M., Z.L., M.W., and T.S.; formal analysis, Y.M. and B.Z.; investigation, Y.M.; resources, R.C.; data curation, Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, R.C.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, R.C.; project administration, R.C.; funding acquisition, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52172396.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, H.C.; Xia, K.; Chen, J.; Miao, S.J.; Qiao, Y.F. Impacts of plant spacing configuration on canopy photosynthetic characteristics and yield of rice. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 93–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.L.; Liu, X.C.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, D.Q.; Zhao, H.Y.; Li, P.; Gu, M.X. Effects of different plant-to-plant spacing on growth and yield of pot seedling rice. Hybrid Rice 2021, 36, 48–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.C.; Zhou, J.D. Field measurement of slip rate of paddy field plant protection machine. J. Hubei Univ. Technol. 2021, 36, 23–25+64. Available online: http://hubeigydxxb.paperonce.org/#/digest?ArticleID=1767 (accessed on 5 July 2024). (In Chinese).

- Guo, N.; Hu, J.T. Variable universe adaptive fuzzy-PID control of traveling speed for rice transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2013, 44, 245–251. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, Y.; Hu, L. Design and experiment of automatic operation system for rice transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 17–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.S.; Kim, S.Y. An automatic vehicle speed control system with consideration of various uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Bali, Indonesia, 20–23 February 2023; pp. 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi, K.; Yoshimoto, K.; Yokoyama, T. A novel maximum adhesive force control without vehicle speed sensor. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Himeji 2022-ECCE Asia), Himeji, Japan, 15–19 May 2022; pp. 1873–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, B.; Xiong, L.; Yu, Z.; Sun, K.; Liu, M. Robust variable structure anti-slip control method of a distributed drive electric vehicle. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 162196–162208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tang, M.; Sun, L. Adaptive torque control in-wheel-motor driven vehicles based on pavement impact factors. J. Automot. Eng. 2024, 14, 33–48. Available online: http://tougao.ijournals.cn/ch/mobile/m_view_abstract.aspx?file_no=20240104&flag=1 (accessed on 12 April 2025). (In Chinese).

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Traction Control for Electric Vehicles with Dual-Mode Coupling Drive System on Split Ramps. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 2632–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Pi, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, Y. Research on Longitudinal–Vertical Coordinated Recovery Drive Control for Corner-Modular Distributed Drive Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 7979–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubaum, M.; Münch, P.; Costantini, G.; Peschke, T.; Görges, D. Slip detection and control for harvesting machines. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinenko, P.V.; Geissler, M.; Herlitzius, T. A method of optimal traction control for farm tractors with feedback of drive torque. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 129, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Z.B.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Z.X.; Song, Z.H.; Mao, E.R. Control method of driving wheel slip ratio of high-power tractor for ploughing operation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 47–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.D.; Wang, W.; Song, Y.L.; Cui, Y.J. Joint control method based on speed and slip rate switching in plowing operation of wheeled electric tractor equipped with sliding battery pack. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.L.; Xie, B.; Wen, C.K.; Zhao, Y.R.; Du, Y.F.; Zhu, Z.X.; Song, Z.H.; Li, L.M. Intelligent ballast control system with active load-transfer for electric tractors. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 215, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.; Uchida, H.; Kato, K. Evaluation of the work performance of a paddy field weeding robot using disturbance observer. In Robotics in Natural Settings; Cascalho, J.M., Tokhi, M.O., Silva, M.F., Mendes, A., Goher, K., Funk, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 530, pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Wu, T.; Xiao, Y.F.; Gong, L.; Liu, C.L. Path planning in continuous adjacent farmlands and robust path tracking control of a rice-seeding robot in paddy field. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 210, 107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.M.; Hu, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, W.Y.; Chen, G.L.; Huang, H.; Lai, S.Y.; Liu, H.L. Method for estimating vertical kinematic states of working implements based on laser receivers and accelerometers. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 203, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawi, A.; De Pinto, S.; Stano, P.; van Aalst, S.; Praet, K.; Boulay, E.; Ivone, D.; Gruber, P.; Sorniotti, A. An adaptive unscented Kalman filter for the estimation of the vehicle velocity components, slip angles, and slip ratios in extreme driving manoeuvres. Sensors 2024, 24, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghparast, B.; Salarieh, H.; Pishkenari, H.N.; Abdollahi, T.; Jokar, M.; Ghanipoor, F. A cubature Kalman filter for parameter identification and output-feedback attitude control of liquid-propellant satellites considering fuel sloshing effects. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 108813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, H.T.; Ngoc, D.N.; Trung, D.P.; Duy, P.N. Application of the Unscented Kalman Filter for Tracking a Maneuvering Tank Modeled with a Second-Order Gauss-Markov Process: A Comparative Analysis with the Extended Kalman Filter. J. Aerosp. Technol. Manag. 2025, 17, e0625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izanloo, R.; Fakoorian, S.A.; Yazdi, H.S.; Simon, D. Kalman Filtering Based on the Maximum Correntropy Criterion in the Presence of Non-Gaussian Noise. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Conference on Information Science and Systems (CISS), Princeton, NJ, USA, 16–18 March 2016; pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pokharel, P.P.; Principe, J.C. Correntropy: Properties and Applications in Non-Gaussian Signal Processing. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2007, 55, 5286–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, I.; Pokharel, P.P.; Principe, J.C. Generalized Correlation Function: Definition, Properties, and Application to Blind Equalization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 2187–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoorian, S.; Santamaria-Navarro, A.; Lopez, B.T.; Simon, D.; Aghamohammadi, A.A. Towards Robust State Estimation by Boosting the Maximum Correntropy Criterion Kalman Filter with Adaptive Behaviors. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5469–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shan, H.; Xu, J.; Yao, X. Robust Variable Kernel Width for Maximum Correntropy Criterion Algorithm. Signal Process. 2021, 182, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Q.; Li, Z.K.; Chen, Z.B.; Sun, Y.W.; Liu, Y.L. Multiple similarity measure-based maximum correntropy criterion Kalman filter with adaptive kernel width for GPS/INS integration navigation. Measurement 2023, 222, 113666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwo, D.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Cho, T.S.; Biswal, A. A robust GPS navigation filter based on maximum correntropy criterion with adaptive kernel bandwidth. Sensors 2023, 23, 9386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Zhao, J.H.; Qu, H.; Chen, B.D. An adaptive kernel width update method of correntropy for channel estimation. Proceedings of 2015 IEEE International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), Singapore, 21–24 July 2015; pp. 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Q.; Zhang, D.S.; Zhu, Z.L.; Yang, C.Y.; Ma, L. Student’s t kernel maximum correntropy Kalman filter and its kernel bandwidth adaptive selection method. Control Decis. 2024, 40, 1541–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for Mechanized Rice Production Technology. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China. 2017. Available online: https://njhs.moa.gov.cn/qcjxhtjxd/201711/t20171102_6297015.htm (accessed on 2 November 2017). (In Chinese)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).