Bayesian Network-Driven Demand Prediction and Multi-Trip Two-Echelon Routing for Fleet-Constrained Metropolitan Logistics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Trip Vehicle Routing Under Fleet Constraints

2.2. Two-Echelon Routing with Satellite Reload Points

2.3. Dynamic and Stochastic Dispatch Under Fleet Limitations

2.4. Bayesian Networks for Supply Chain Risk and Demand Prediction

2.5. Research Gap

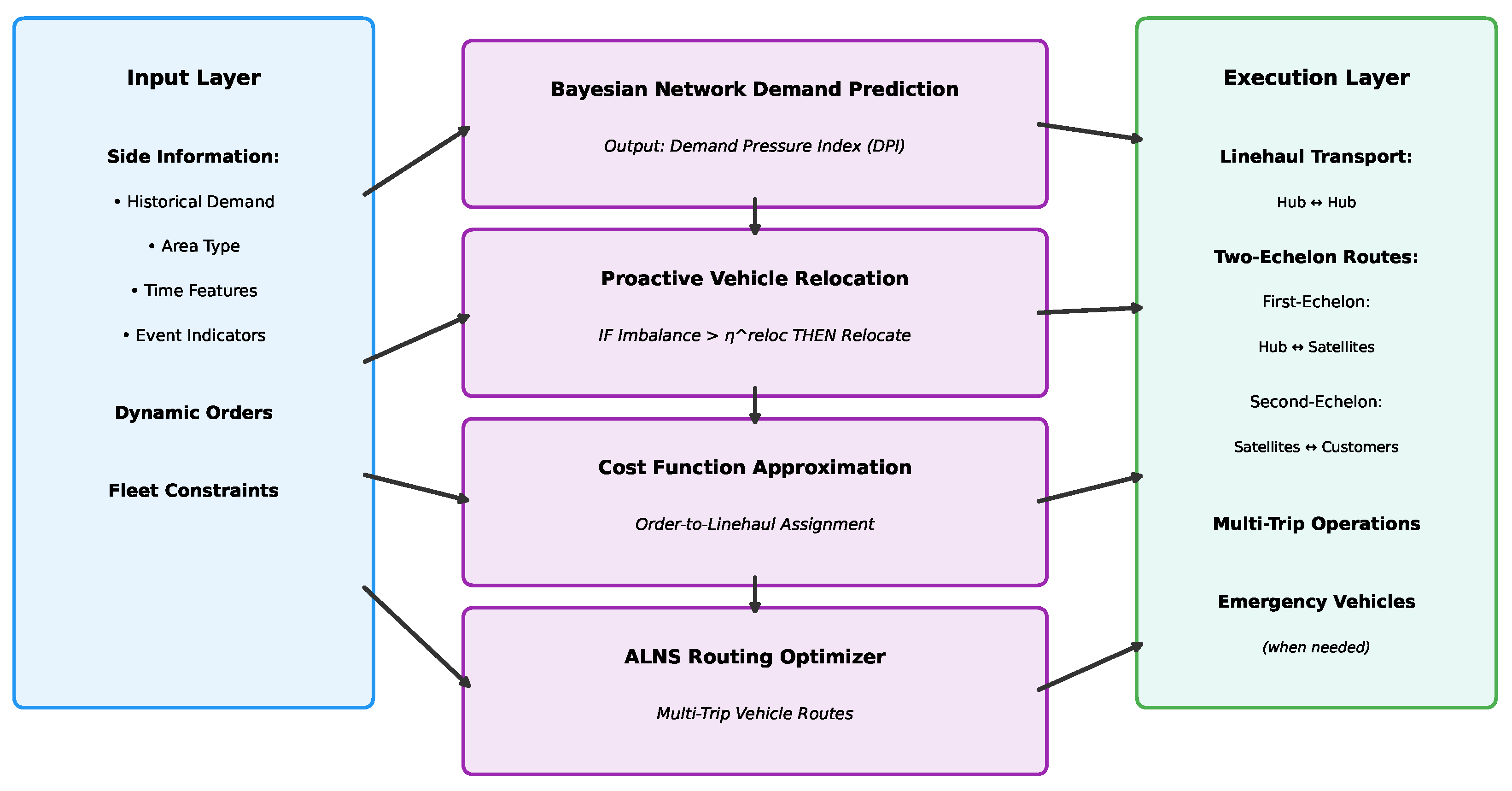

3. Model

3.1. Problem Description

- 1.

- Unlimited First-Echelon Fleet Size: The number of first-echelon vehicles operating between hubs and satellites is assumed to be unlimited. This reflects the fundamental difference in operational characteristics between the two echelons: first-echelon vehicles operate on predictable routes between fixed facilities (hubs and satellites) with consolidated loads, enabling efficient capacity planning and flexible fleet adjustment through third-party logistics providers or on-demand vehicle leasing. This assumption transforms the dynamic first-echelon routing into a sequence of independent static optimization problems, where each epoch’s routing decisions are made without tracking vehicle states or availability constraints. In contrast, second-echelon vehicles must navigate dynamic customer-specific routes with strict time windows, requiring dedicated local resources and specialized knowledge of the service area.

- 2.

- Fixed Second-Echelon Fleet During Operations: The second-echelon fleet size remains constant throughout the operational period. Vehicle acquisition and disposal decisions cannot be made in real-time due to capital investment lead times and labor contracts.

- 3.

- Deterministic Travel Times: Travel times between locations are known and constant. While this simplification is common in strategic fleet sizing problems and aligns with standard VRP literature, we partially capture real-world traffic variations through time-dependent linehaul capacity adjustments during peak (80% capacity) and off-peak (120% capacity) periods. This approach balances model tractability with operational realism for the core fleet sizing and multi-trip coordination challenges.

- 4.

- No Split Deliveries: Each order must be handled entirely by a single vehicle. This maintains operational simplicity and package tracking integrity, reflecting standard practice in parcel delivery operations.

- 5.

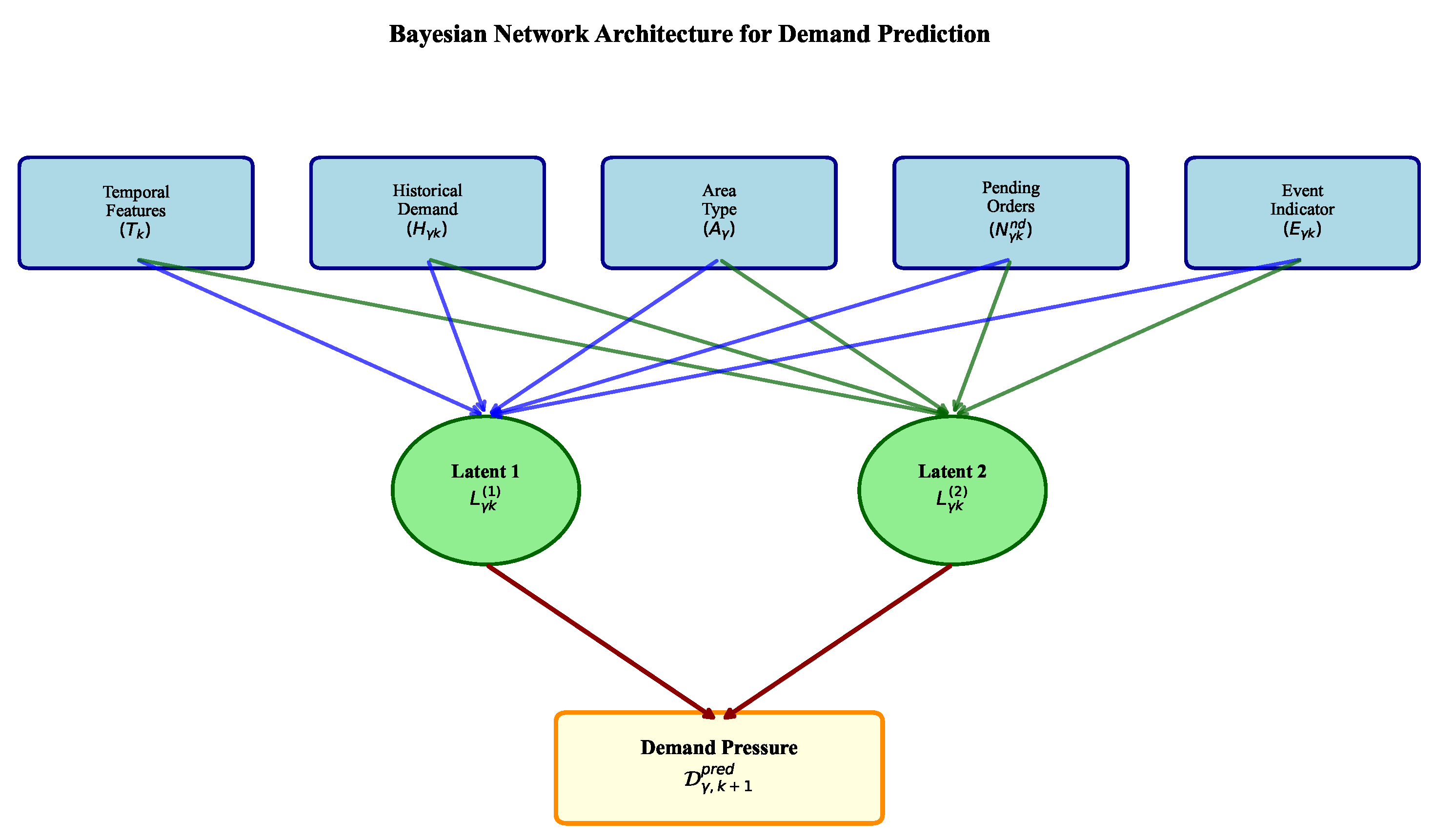

- Predictable Demand Patterns: Order arrivals exhibit spatial-temporal patterns that can be learned from historical data and side information. While individual orders remain stochastic, aggregate demand at the satellite level shows sufficient regularity to enable meaningful predictions through our Bayesian Network approach.

- 6.

- Relocation Time Windows: Vehicle relocations can only occur during idle periods and must be complete before the vehicle’s next anticipated assignment. This ensures that proactive positioning does not interfere with active service commitments.

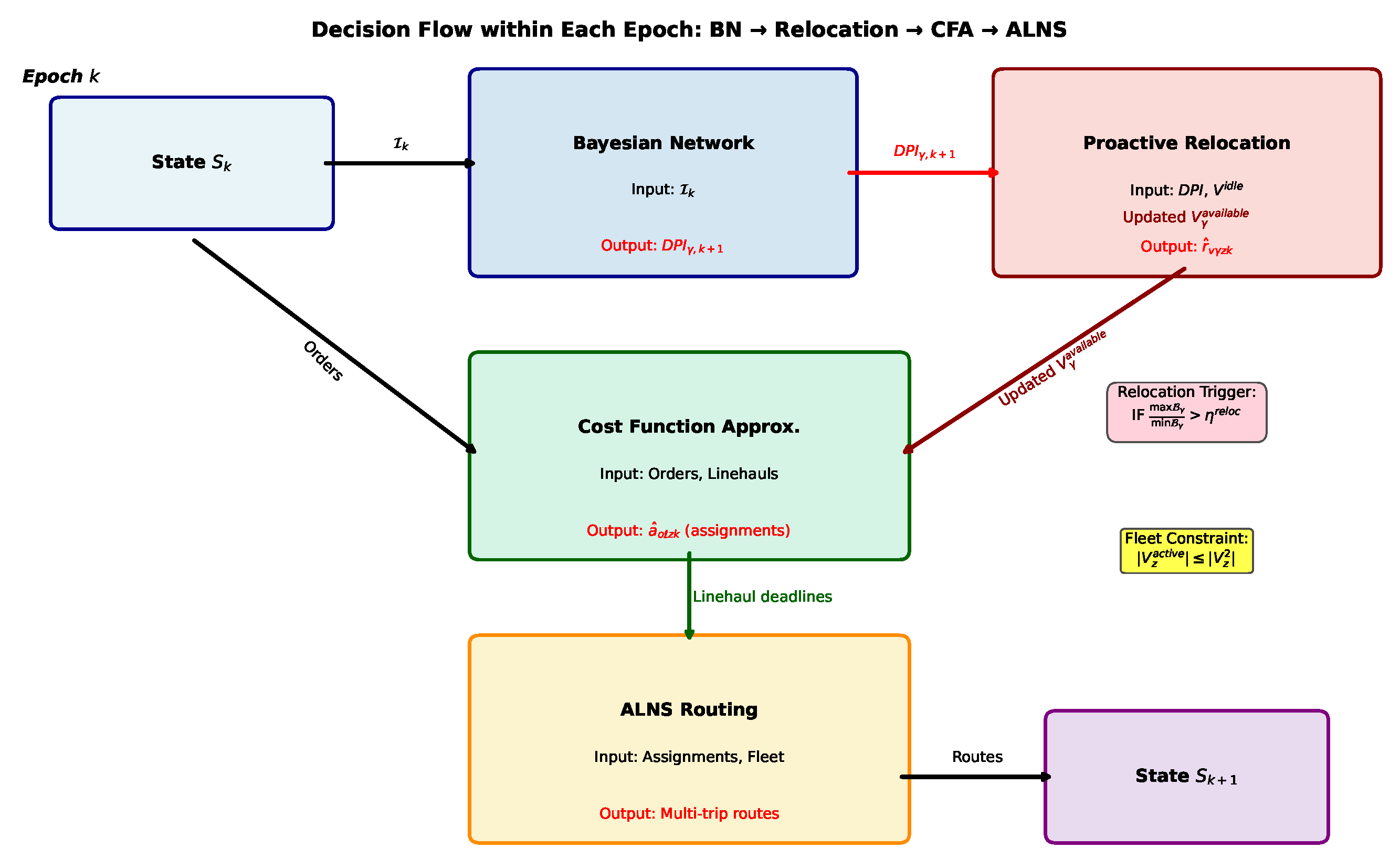

3.2. Markov Decision Process

- is the current time at decision epoch k.

- is a vector of order indices ready for first-mile pickup in each city.

- and are vectors of orders awaiting middle-mile linehaul shipment and their arrival times at origin hubs.

- and are vectors of orders awaiting last-mile delivery and their arrival times at destination hubs.

- denotes the set of linehauls departing after time from city z.

- represents the status of second-echelon vehicles, where the following apply:

- -

- is the current satellite location of vehicle v.

- -

- is the operational status.

- -

- is the time when the vehicle becomes available for new assignments.

- contains satellite-specific side information, where each includes the following:

- -

- : historical average demand at satellite for similar time periods over the past few days.

- -

- : satellite area classification.

- -

- : number of pending next-day orders currently assigned to satellite .

- -

- : binary indicator for special events near satellite .

- 1.

- Order Assignment: Binary variables indicating if order is assigned to linehaul .

- 2.

- Vehicle Dispatch and Routing: Selecting subset and determining multi-trip routes for available second-echelon vehicles, with binary variables indicating if route is executed.

- 3.

- Proactive Vehicle Relocation: To address predicted demand imbalances across satellites, the system can proactively relocate idle vehicles. Binary variables indicate whether idle vehicle v is relocated from its current satellite to satellite in city z at epoch k. These relocation decisions are subject to the following operational constraints:

- Each idle vehicle can be relocated to at most one destination: .

- Only vehicles with are eligible for relocation.

- Relocations occur only between satellites within the same city: if where .

- To prevent cascading relocations, vehicles relocated in the previous epoch cannot be relocated again: if , then .

- is the linehaul assignment cost,where represents all orders eligible for linehaul assignment, and indicates whether linehaul ℓ is used.

- is the regular vehicle routing cost,where is the set of second-echelon routes in city z at epoch k, and denotes the total distance of route .

- is the emergency transportation cost,where is the set of orders that cannot be served within time windows by the regular fleet, and is the emergency vehicle travel distance for order o.

- is the proactive relocation cost, representing the operational expense of repositioning vehicles between satellites,where represents the set of currently idle vehicles in city z, and is the distance between the vehicle’s current satellite and the target satellite.

- (update satellite assignment).

- (update availability time).

- during transit, then idle upon arrival.

- At epoch k, when relocation is initiated, the following apply:

- -

- Vehicle remains physically at origin satellite: unchanged.

- -

- Status updates to prevent new assignments: .

- -

- Availability time set based on travel time: .

- At subsequent epoch, when , the following apply:

- -

- Vehicle arrives at destination: .

- -

- Status returns to idle: .

- -

- Vehicle becomes available for routing from new location.

- First Stage (Strategic Fleet Sizing): The term represents the total fleet operating costs across all cities, where scales linearly with the number of second-echelon vehicles. This captures the fixed daily costs including driver wages, insurance, and maintenance that must be committed before operations begin.

- Second Stage (Operational Decisions): The expectation term represents the expected cumulative operational costs over the planning horizon under policy . At each epoch k, the immediate cost comprises the following four components as defined in Equation (3):

- -

- Linehaul assignment costs for middle-mile transportation.

- -

- Regular vehicle routing costs for first and second-echelon operations.

- -

- Emergency transportation costs when regular fleet capacity is exceeded.

- -

- Proactive relocation costs for anticipatory vehicle repositioning.

- Stochastic Nature: The expectation is taken over the stochastic order arrival process , which captures the uncertainty in demand patterns across time and space. The policy must adapt to these realizations while working within the constraints imposed by the first-stage fleet size decisions.

4. Solution Method

4.1. Demand Prediction and Proactive Vehicle Relocation

4.1.1. Bayesian Network for Demand Prediction

4.1.2. Proactive Relocation Strategy

“Vehicle V12 relocated from Satellite A to Satellite B because of the following:

4.1.3. Initial Fleet Distribution

- represents pending next-day orders at satellite .

- is the historical average morning demand for the satellite.

- and are weights prioritizing immediate needs over historical patterns.

- allocates remaining vehicles after floor operation to highest-priority satellites.

4.2. Cost Function Approximation for Linehaul Assignment

4.2.1. Modified Assignment Cost with Slack Time

4.2.2. Deterministic Assignment Formulation

4.3. Parameterized Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search

4.3.1. Algorithm Overview and Positioning

4.3.2. Parameterized Dispatching Policy

4.3.3. Core ALNS Framework

4.4. Hierarchical Bayesian Optimization for Fleet Sizing and Operational Parameters

4.4.1. Problem Decomposition

4.4.2. Outer Level: Fleet Size Optimization

4.4.3. Inner Level: Operational Parameter Optimization

4.4.4. Knowledge Transfer Mechanism

4.4.5. Implementation Details

5. Computational Experiments

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. System Configuration and Test Instances

5.1.2. Experimental Design

5.1.3. Solution Methods

5.2. Simulation Results

5.2.1. Overall Performance Comparison

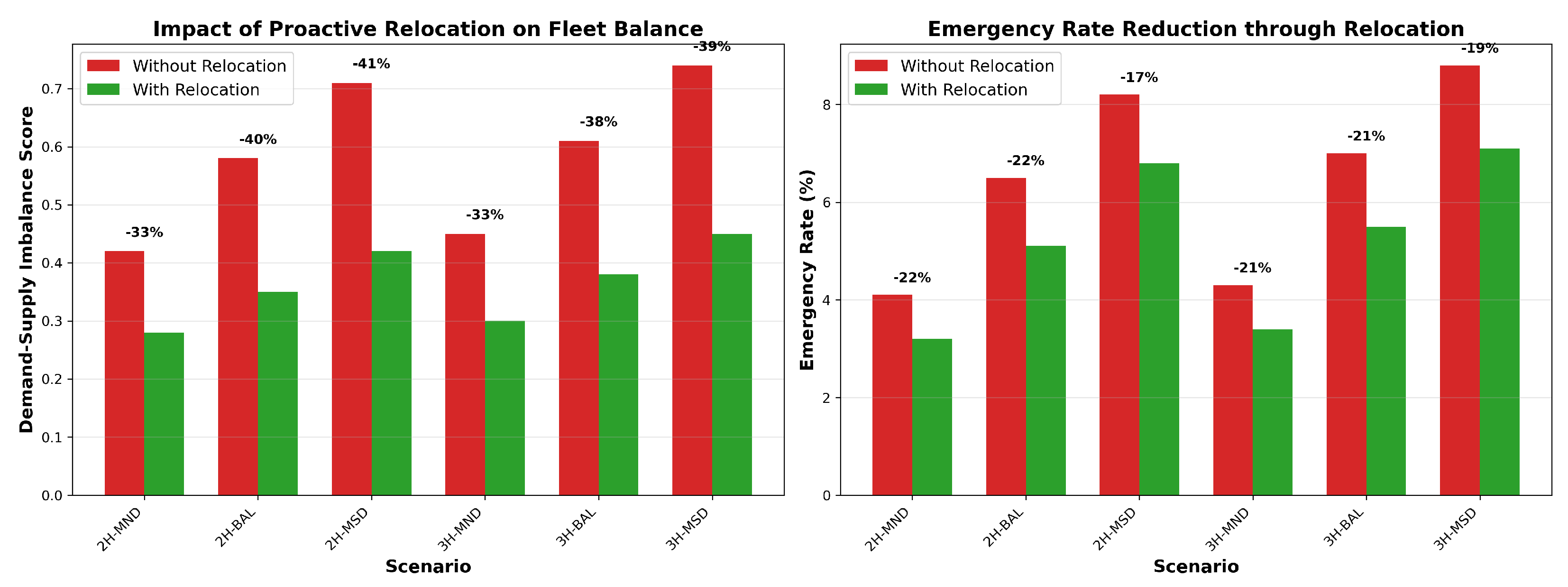

5.2.2. Impact of Proactive Relocation

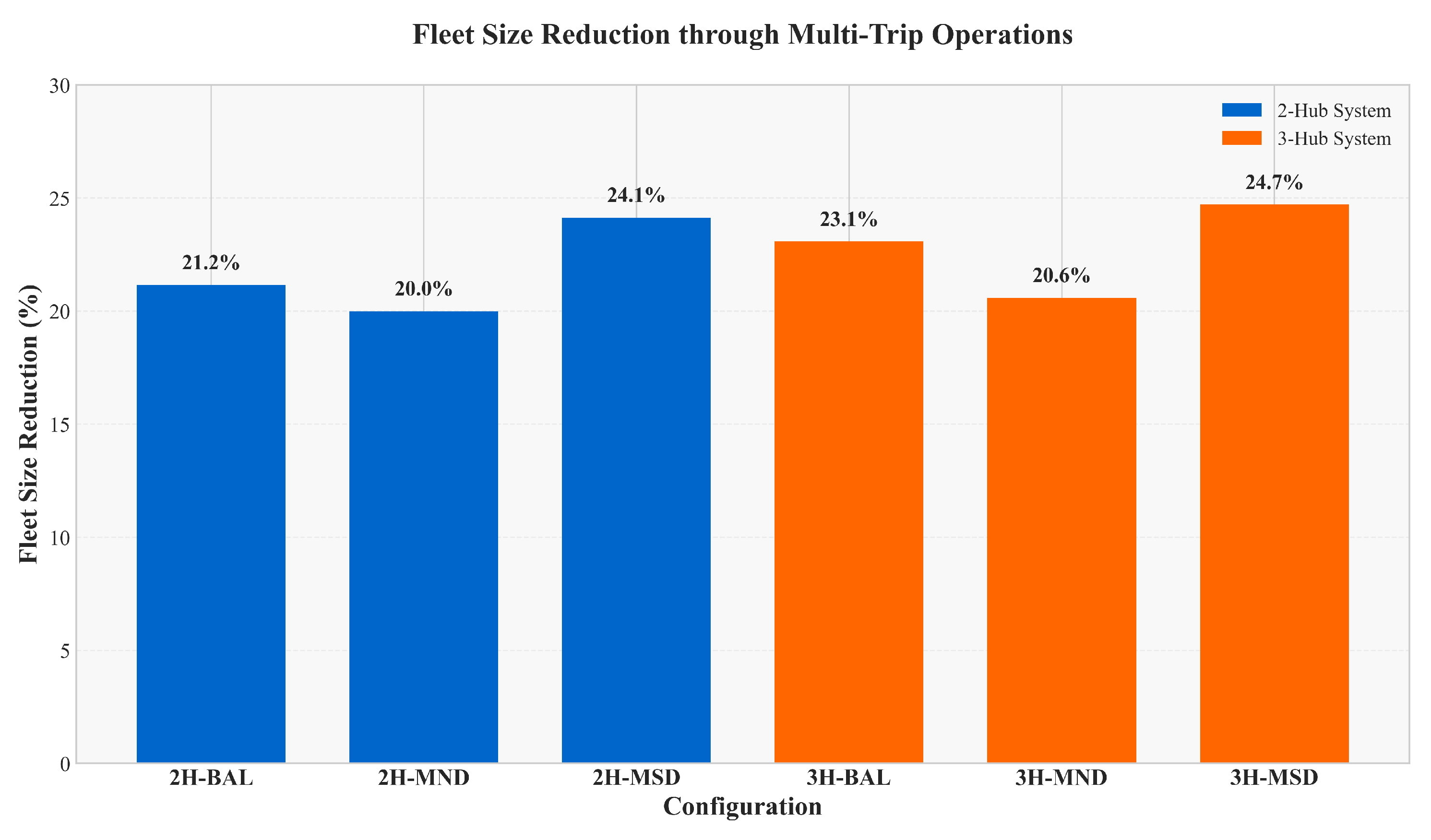

5.2.3. Fleet Reduction Analysis

5.2.4. Cost Structure Analysis

5.2.5. Relocation Pattern Analysis

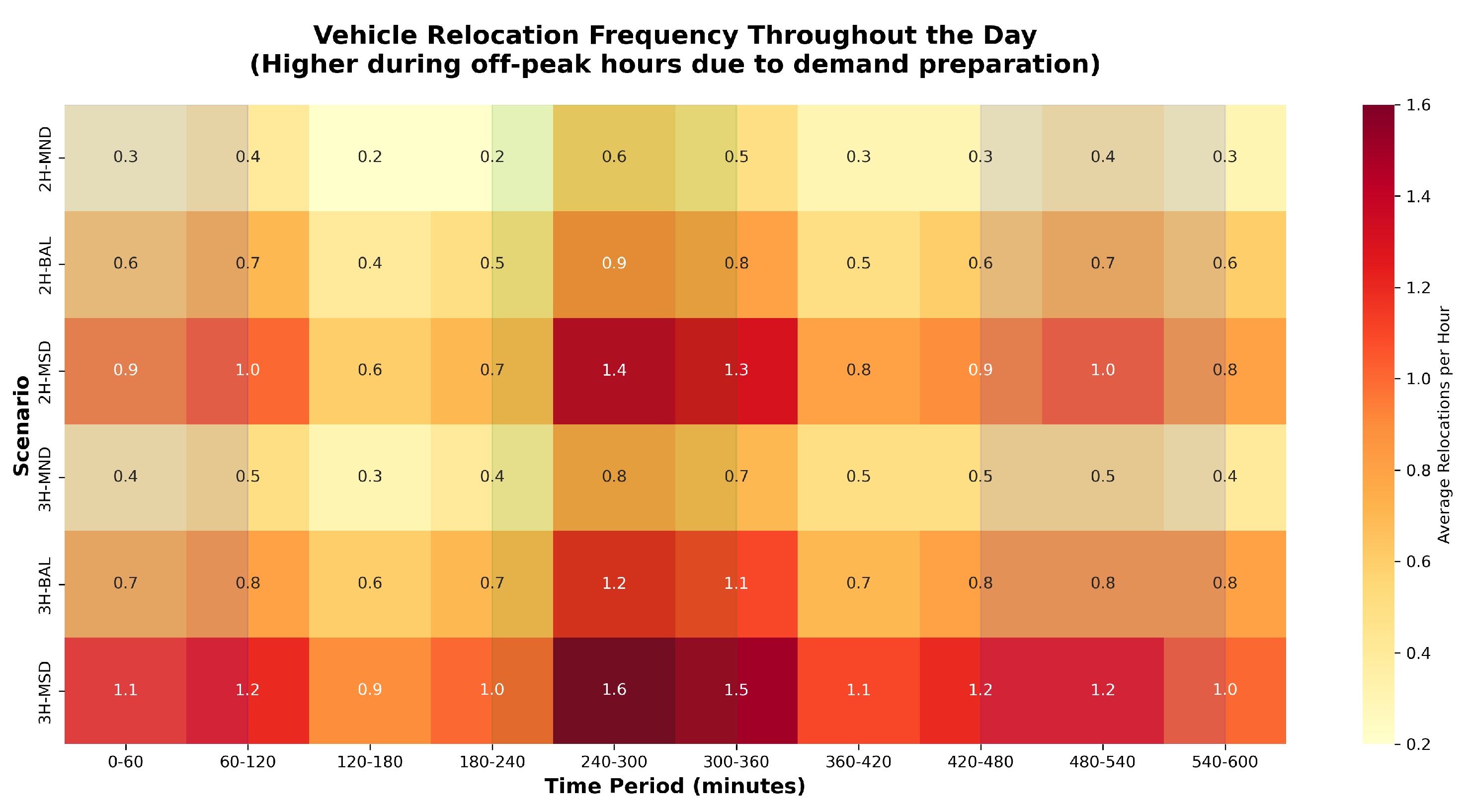

5.2.6. Temporal Relocation Patterns

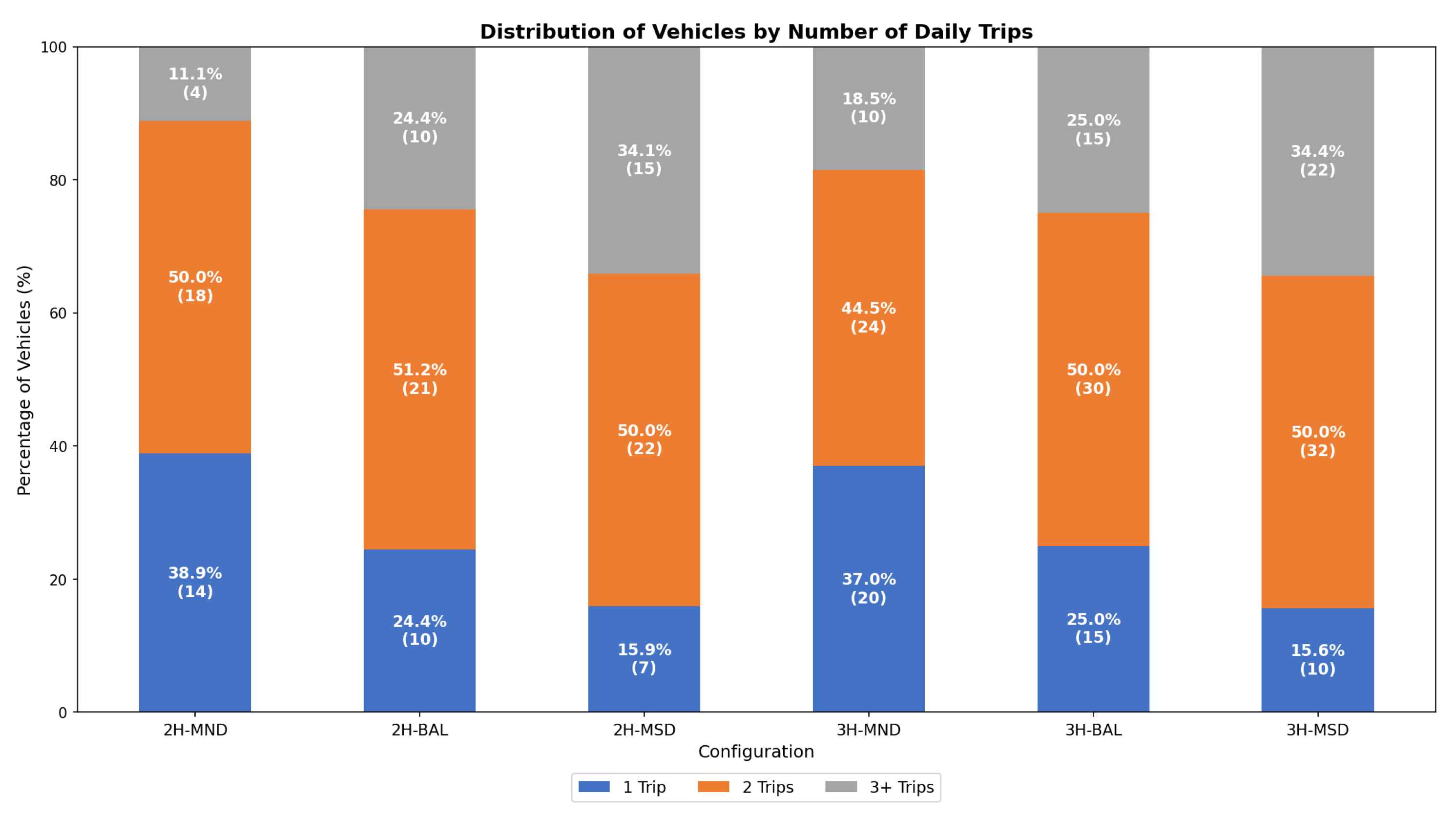

5.2.7. Multi-Trip Utilization Patterns

5.2.8. Optimized Parameter Analysis

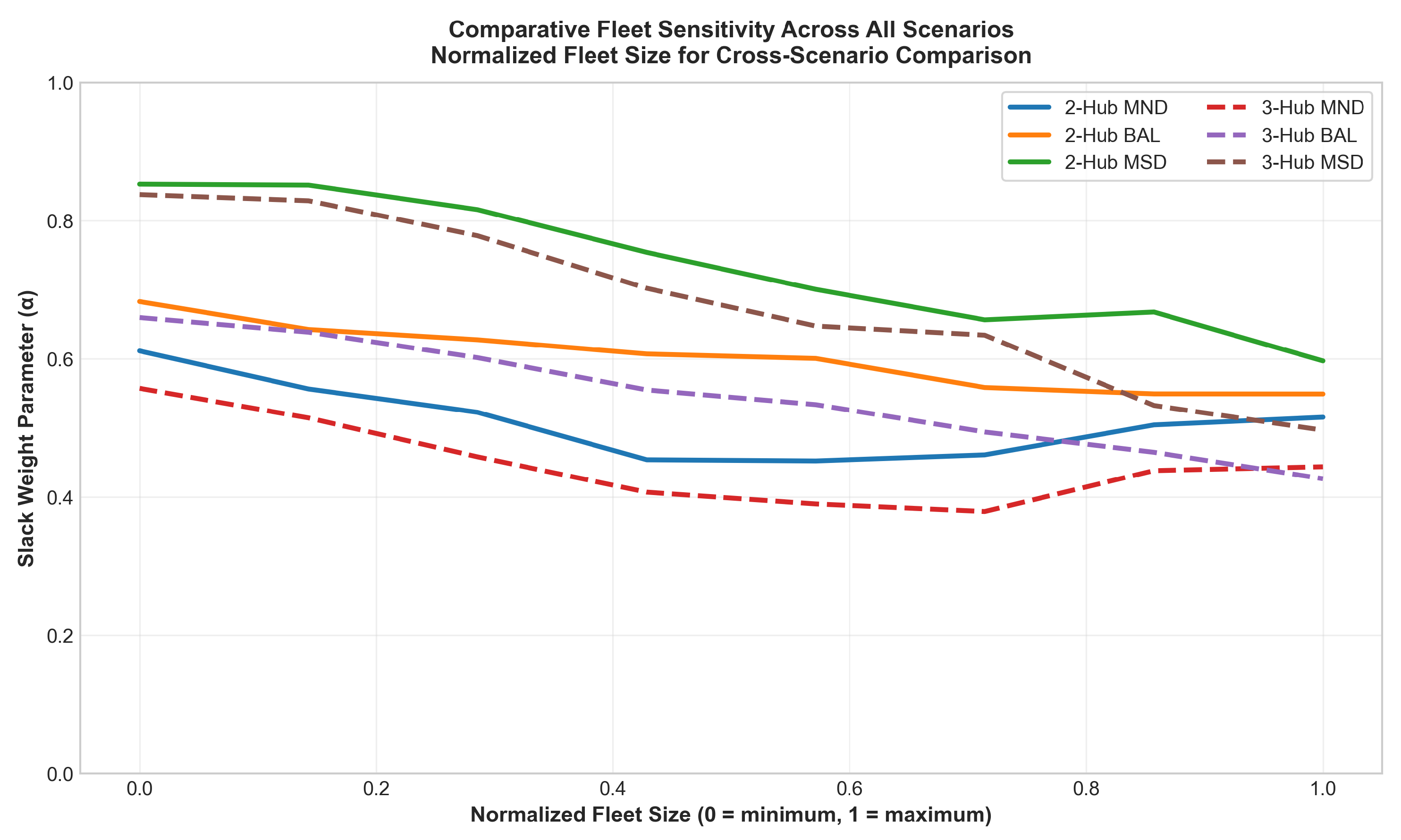

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Impact of Fleet Size on Operational Strategy

5.4. Case Study

5.4.1. Dataset Description

- Time period: 14 operational days.

- Network configurations: 2-hub and 3-hub systems.

- The demand scenarios are as follows:

- -

- More Next-Day (MND): 25% same-day, 75% next-day orders.

- -

- Balanced (BAL): 50% same-day, 50% next-day orders.

- -

- More Same-Day (MSD): 75% same-day, 25% next-day orders.

- Order volume: 2000–3000 orders per configuration.

- Current operation: Latest Departure Schedule (LDS) heuristic with predetermined fleet allocation.

5.4.2. Performance Comparison

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Computational Performance

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sluijk, N.; Florio, A.M.; Kinable, J.; Dellaert, N.; Van Woensel, T. Two-echelon vehicle routing problems: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 304, 865–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaruzza, D.; Absi, N.; Feillet, D. Vehicle routing problems with multiple trips. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 271, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumez, D.; Tilk, C.; Irnich, S.; Lehuédé, F.; Olkis, K.; Péton, O. A matheuristic for a 2-echelon vehicle routing problem with capacitated satellites and reverse flows. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Winkenbach, M. A matheuristic for the Two-Echelon Multi-Trip Vehicle Routing Problem with mixed pickup and delivery demand and time windows. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 160, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, F.; Feillet, D.; Giroudeau, R.; Naud, O. Branch-and-price algorithms for the solution of the multi-trip vehicle routing problem with time windows. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, K.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, W. Multi-depot multi-trip vehicle routing problem with time windows and release dates. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 135, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermín Cueto, P.; Gjeroska, I.; Solà Vilalta, A.; Anjos, M.F. A solution approach for multi-trip vehicle routing problems with time windows, fleet sizing, and depot location. Networks 2021, 78, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Zhou, Z.; Li, R.; Chang, Z.; Shi, J. The multi-fleet delivery problem combined with trucks, tricycles, and drones for last-mile logistics efficiency requirements under multiple budget constraints. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 187, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademir, C.; Beirigo, B.A.; Atasoy, B. A two-echelon multi-trip vehicle routing problem with synchronization for an integrated water- and land-based transportation system. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 322, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Zhang, Z.; Lim, A. Multi-trip time-dependent vehicle routing problem with time windows. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangier, P.; Gendreau, M.; Lehuédé, F.; Rousseau, L.-M. An adaptive large neighborhood search for the two-echelon multiple-trip vehicle routing problem with satellite synchronization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 254, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, D.L.J.U.; Jargalsaikhan, B.; Roodbergen, K.J.; uit het Broek, M.A.J.; Schrotenboer, A.H. The two-echelon vehicle routing problem with covering options: City logistics with cargo bikes and parcel lockers. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 118, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Bai, M. Two-echelon vehicle routing problem with satellite bi-synchronization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 288, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A.G.; Viana, A.; Pedroso, J.P. 2-echelon lastmile delivery with lockers and occasional couriers. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 162, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahimi, A.; Lurkin, V.; Mohammadi, M.; Van Woensel, T. A two-echelon vehicle routing problem with mobile satellites and multiple commodities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 326, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadaros, M.; Kyriakakis, N.A. A Hybrid Clustered Ant Colony Optimization Approach for the Hierarchical Multi-Switch Multi-Echelon Vehicle Routing Problem with Service Times. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Labadie, N.; Prins, C. A Two-echelon Vehicle Routing Problem with time-dependent travel times in the city logistics context. EURO J. Transp. Logist. 2024, 13, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamal, M.A.; Schrotenboer, A.H.; Van Woensel, T. The two-echelon vehicle routing problem with pickups, deliveries, and deadlines. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 179, 107016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.K.; Yaman, H. A Branch and Price Algorithm for the Heterogeneous Fleet Multi-Depot Multi-Trip Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows. Transp. Sci. 2022, 56, 1636–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, H.; Xue, H. A Two-Echelon Multi-Trip Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows for Fresh E-Commerce Logistics under Front Warehouse Mode. Systems 2024, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crainic, T.G.; Gobbato, L.; Perboli, G.; Rei, W. Logistics capacity planning: A stochastic bin packing formulation and a progressive hedging meta-heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 253, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilas, V.; Demir, E.; Van Woensel, T. A scenario-based planning for the pickup and delivery problem with time windows, scheduled lines and stochastic demands. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2016, 91, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapp, M.A.; Erera, A.L.; Toriello, A. The Dynamic Dispatch Waves Problem for same-day delivery. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 271, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heeswijk, W.J.A.; Mes, M.R.K.; Schutten, J.M.J. The Delivery Dispatching Problem with Time Windows for Urban Consolidation Centers. Transp. Sci. 2019, 53, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hewitt, M.; Lehuédé, F.; Medina, J.; Péton, O. A continuous-time service network design and vehicle routing problem. Networks 2023, 83, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.; Hewitt, M.; Lehuédé, F.; Péton, O. Integrating long-haul and local transportation planning: The Service Network Design and Routing Problem. EURO J. Transp. Logist. 2019, 8, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamal, M.A.; Schrotenboer, A.H.; Van Woensel, T. End-to-end logistics in metropolitan areas: A stochastic dynamic order-assignment and dispatching problem. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2025, 199, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijk, N.; Florio, A.M.; Kinable, J.; Dellaert, N.; Van Woensel, T. A Chance-Constrained Two-Echelon Vehicle Routing Problem with Stochastic Demands. Transp. Sci. 2023, 57, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Li, D.; Zhou, T.; Leung, M.-F. JointSTNet: Joint Pre-Training for Spatial-Temporal Traffic Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 6239–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni Prathiba, S.; Ram Krishnamoorthy, S.; Soundari Kannan, K.; Selvaraj, A.K.; Ranganayakulu, D.; Fang, K.; Gadekallu, T.R. Digital Twin-Enabled Real-Time Optimization System for Traffic and Power Grid Management in 6G-Driven Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 29164–29175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, M.D.; Carnovale, S.; Yeniyurt, S. An analytical framework for supply network risk propagation: A Bayesian network approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 243, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Ripple effect modelling of supplier disruption: Integrated Markov chain and dynamic Bayesian network approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3284–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Chu, F.; Chu, C. A new robust dynamic Bayesian network approach for disruption risk assessment under the supply chain ripple effect. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Tang, H.; Chu, F.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, F.; Chu, C. A signomial programming-based approach for multi-echelon supply chain disruption risk assessment with robust dynamic Bayesian network. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 161, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D. A multi-layer Bayesian network method for supply chain disruption modelling in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 5258–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Chu, F.; Zheng, F.; Dolgui, A. Dynamic structural adaptation for building viable supply chains under super disruption events. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2025, 195, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, S.F.; Mohammadi, M.; Pasandideh, S.H.R. A Bayesian network approach to production decisions by incorporating complex causal factors. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnakumar, R.; Nannapaneni, S. Forecasting bike sharing demand using quantum Bayesian network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 221, 119749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Chu, F.; Zheng, F.; Chu, C. Risk-averse dynamic Bayesian network for supply chain risk evaluation under ripple effects and risk dispersion. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2025, 59, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, D.; Song, Z. Adaptive eco-cruising control for connected electric vehicles considering a dynamic preceding vehicle. eTransportation 2024, 19, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.B. Reinforcement learning and stochastic optimization: A unified framework for sequential decisions. Quant. Financ. 2022, 22, 2151–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature | Problem Characteristics | Environment | Operational Features | Analytics | Model | Solution Method | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2E | MT | FC | E2E | DE | SE | RT | MA | BN | PD | PA | |||

| Multi-Trip Vehicle Routing | |||||||||||||

| Hernandez et al. [5] | ✓ | MIP | B&P | ||||||||||

| Zhen et al. [6] | ✓ | MIP | PSO/GA | ||||||||||

| Fermín Cueto et al. [7] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | Robust | |||||||||

| Pan et al. [10] | ✓ | MIP | ALNS | ||||||||||

| Two-Echelon Vehicle Routing | |||||||||||||

| Dumez et al. [3] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | Matheuristic | |||||||||

| Lehmann Winkenbach [4] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | Matheuristic | |||||||||

| Karademir et al. [9] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | LBBD | |||||||||

| Grangier et al. [11] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | ALNS | |||||||||

| Şahin Yaman [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | B&P | ||||||||

| Dynamic and Stochastic Dispatching | |||||||||||||

| Ghilas et al. [22] | ✓ | SP | SAA | ||||||||||

| Klapp et al. [23] | ✓ | ✓ | MIP | Heuristic | |||||||||

| Van Heeswijk et al. [24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MDP | ADP | ||||||||

| Zamal et al. [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MDP | CFA+ALNS | |||||

| Sluijk et al. [28] | ✓ | ✓ | CC-SP | CG | |||||||||

| Bayesian Networks | |||||||||||||

| Garvey et al. [31] | ✓ | BN | Simulation | ||||||||||

| Hosseini et al. [32] | ✓ | ✓ | DBN-DTMC | Analytical | |||||||||

| Liu et al. [33] | ✓ | ✓ | R-DBN | SA | |||||||||

| Liu et al. [34] | ✓ | R-DBN | SP | ||||||||||

| Hosseini Ivanov [35] | ✓ | ✓ | ML-BN | Simulation | |||||||||

| Liu et al. [36] | ✓ | ✓ | SV-DBN | DC | |||||||||

| Attar et al. [37] | ✓ | BN | Learning | ||||||||||

| Harikrishnakumar Nannapaneni [38] | ✓ | ✓ | QBN | Quantum | |||||||||

| Liu et al. [39] | ✓ | ✓ | RA-DBN | QCQP | |||||||||

| Our work | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MDP+BN | CFA+ALNS |

| Parameter Category | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Geographic Layout | |

| City structure | 1 hub + 2 satellites per city |

| Coordinate system | UTM grid |

| Hub location | City center |

| Satellite distance from hub | 20–30 units |

| Temporal Parameters | |

| Planning horizon (T) | 600 min (10 h) |

| Decision epoch interval () | 60 min |

| Number of epochs (K) | 10 |

| Order arrival window | min (uniform) |

| Order Characteristics | |

| Daily order volume per city | 150–200 orders |

| Order weight | 1–4 units (uniform random integer) |

| Same-day pickup window | min |

| Same-day delivery window | min |

| Next-day pickup window | min |

| Next-day delivery window | min |

| Vehicle Specifications | |

| First-echelon capacity () | 75 units |

| First-echelon fleet size | Unlimited |

| Second-echelon capacity () | 10 units |

| Second-echelon fleet size | To be optimized |

| Reload time () | 15 min |

| Service time () | 5 min |

| Maximum trip duration | 180 min |

| Cost Parameters | |

| Fixed cost () | 150 per vehicle per day |

| Variable cost () | 2 per km |

| Emergency fixed cost () | 500 per deployment |

| Emergency variable cost () | 5 per km |

| Linehaul Configuration | |

| Peak hours (0–120, 480–600 min) | |

| Capacity | 72 units (80% of baseline) |

| Travel time | 108–130 min (120% of baseline) |

| Fixed/variable cost | 90–108/12–14.4 (120% of baseline) |

| Off-peak hours (240–360 min) | |

| Capacity | 108 units (120% of baseline) |

| Travel time | 72–86 min (80% of baseline) |

| Fixed/variable cost | 60–72/8–9.6 (80% of baseline) |

| Regular hours (120–240, 360–480 min) | |

| Capacity | 90 units (baseline) |

| Travel time | 90–108 min (baseline) |

| Fixed/variable cost | 75–90/10–12 (baseline) |

| Hubs | Scenario | OF-ST | OF-MT | OF-MT-R | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Reloc/Day | Imb | ||

| 2 | MND | 45 | 185,324 | 3.2 | 36 | 156,875 | 4.1 | 36 | 149,231 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 0.28 |

| BAL | 52 | 198,657 | 5.8 | 41 | 158,926 | 6.5 | 41 | 148,789 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 0.35 | |

| MSD | 58 | 216,482 | 7.5 | 44 | 167,774 | 8.2 | 44 | 154,072 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 0.42 | |

| 3 | MND | 68 | 278,543 | 3.5 | 54 | 231,192 | 4.3 | 54 | 219,632 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 0.30 |

| BAL | 78 | 298,316 | 6.2 | 60 | 232,687 | 7.0 | 60 | 216,398 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 0.38 | |

| MSD | 85 | 319,624 | 8.0 | 64 | 243,374 | 8.8 | 64 | 223,083 | 7.1 | 10.3 | 0.45 | |

| Average | 64.3 | 249,491 | 5.7 | 49.8 | 198,471 | 6.5 | 49.8 | 185,201 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 0.36 | |

| vs. OF-ST | - | - | - | −22.6% | −20.5% | +14.0% | −22.6% | −25.8% | −8.8% | - | - | |

| vs. OF-MT | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0% | −6.7% | −20.0% | - | - | |

| Scenario | Component | OF-ST | OF-MT | OF-MT-R | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleet | Routing | Emerg | LH | Fleet | Routing | Emerg | LH | Fleet | Routing | Emerg | LH+Reloc | ||

| 2H-MND | Amount | 6750 | 141,854 | 6720 | 3500 | 5400 | 118,564 | 8610 | 3426 | 5400 | 115,879 | 5856 | 4096 |

| % of Total | 3.6 | 76.6 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 75.6 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 77.6 | 3.9 | 2.7 | |

| 2H-BAL | Amount | 7800 | 142,567 | 12,180 | 3510 | 6150 | 113,726 | 13,650 | 3474 | 6150 | 110,542 | 9828 | 4269 |

| % of Total | 3.9 | 71.8 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 71.6 | 8.6 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 74.3 | 6.6 | 2.9 | |

| 2H-MSD | Amount | 8700 | 146,032 | 15,750 | 3518 | 6600 | 112,554 | 17,220 | 3400 | 6600 | 108,126 | 12,546 | 4800 |

| % of Total | 4.0 | 67.5 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 67.1 | 10.3 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 70.2 | 8.1 | 3.1 | |

| 3H-MND | Amount | 10,200 | 217,318 | 11,025 | 5457 | 8100 | 182,567 | 13,545 | 5380 | 8100 | 177,865 | 9207 | 6460 |

| % of Total | 3.7 | 78.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 79.0 | 5.9 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 81.0 | 4.2 | 2.9 | |

| 3H-BAL | Amount | 11,700 | 217,366 | 19,530 | 5420 | 9000 | 178,332 | 22,050 | 5305 | 9000 | 172,146 | 15,876 | 6376 |

| % of Total | 3.9 | 72.9 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 76.7 | 9.5 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 79.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | |

| 3H-MSD | Amount | 12,750 | 219,774 | 25,200 | 5400 | 9600 | 171,274 | 27,720 | 5346 | 9600 | 164,532 | 19,404 | 7547 |

| % of Total | 4.0 | 68.8 | 7.9 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 70.4 | 11.4 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 73.7 | 8.7 | 3.4 | |

| Hubs | Scenario | Metric | Time Period | Daily Avg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning | Afternoon | Evening | ||||

| (0–200) | (200–400) | (400–600) | ||||

| 2 | MND | Relocations | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 72.5 | 78.3 | 75.6 | 75.5 | ||

| Cost Savings | 1823 | 2456 | 2365 | 6644 | ||

| BAL | Relocations | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 5.8 | |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 76.2 | 82.1 | 79.4 | 79.2 | ||

| Cost Savings | 2987 | 4123 | 3027 | 10,137 | ||

| MSD | Relocations | 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 8.4 | |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 81.3 | 85.7 | 82.9 | 83.3 | ||

| Cost Savings | 4234 | 5867 | 3601 | 13,702 | ||

| 3 | MND | Relocations | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 4.5 |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 74.2 | 79.5 | 77.1 | 76.9 | ||

| Cost Savings | 2456 | 3897 | 3207 | 11,560 | ||

| BAL | Relocations | 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 7.2 | |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 77.8 | 83.4 | 80.9 | 80.7 | ||

| Cost Savings | 3987 | 5431 | 3871 | 16,289 | ||

| MSD | Relocations | 3.2 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 10.3 | |

| BN Accuracy (%) | 82.7 | 87.1 | 84.2 | 84.7 | ||

| Cost Savings | 5675 | 7234 | 4382 | 20,291 | ||

| Method | Hubs | Scenario | Core Parameters | Relocation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OF-ST | 2 | MND | 0.259 | 158 | 2.2 | – | – |

| BAL | 0.406 | 120 | 2.0 | – | – | ||

| MSD | 0.551 | 99 | 1.8 | – | – | ||

| 3 | MND | 0.201 | 162 | 2.3 | – | – | |

| BAL | 0.350 | 131 | 2.1 | – | – | ||

| MSD | 0.507 | 106 | 1.9 | – | – | ||

| OF-MT | 2 | MND | 0.454 | 135 | 1.8 | – | – |

| BAL | 0.607 | 118 | 1.9 | – | – | ||

| MSD | 0.754 | 89 | 2.0 | – | – | ||

| 3 | MND | 0.407 | 148 | 1.7 | – | – | |

| BAL | 0.555 | 123 | 1.8 | – | – | ||

| MSD | 0.702 | 97 | 1.9 | – | – | ||

| OF-MT-R | 2 | MND | 0.454 | 135 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| BAL | 0.607 | 118 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | ||

| MSD | 0.754 | 89 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.2 | ||

| 3 | MND | 0.407 | 148 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 0.7 | |

| BAL | 0.555 | 123 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 0.9 | ||

| MSD | 0.702 | 97 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | ||

| Hubs | Scenario | LDS (Current) | OF-ST | OF-MT | OF-MT-R (Ours) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | Fleet | Cost | ER (%) | ||

| 2 | MND | 180 | 856,200 | 12.5 | 135 | 599,340 | 8.2 | 108 | 489,468 | 9.5 | 108 | 456,327 | 7.2 |

| BAL | 195 | 918,540 | 15.8 | 150 | 642,978 | 10.1 | 120 | 514,382 | 11.8 | 120 | 472,230 | 8.9 | |

| MSD | 215 | 987,450 | 18.5 | 165 | 691,215 | 11.8 | 130 | 529,300 | 13.2 | 130 | 476,370 | 10.3 | |

| 3 | MND | 260 | 1,286,400 | 13.2 | 195 | 900,480 | 8.7 | 155 | 738,393 | 10.1 | 155 | 687,246 | 7.8 |

| BAL | 285 | 1,377,900 | 16.5 | 220 | 964,530 | 10.8 | 175 | 750,823 | 12.3 | 175 | 683,249 | 9.5 | |

| MSD | 310 | 1,475,640 | 19.2 | 240 | 1,032,948 | 12.5 | 190 | 784,674 | 13.8 | 190 | 702,294 | 10.8 | |

| Average Improvement over LDS: | |||||||||||||

| OF-ST: −23.5% fleet, −30.0% cost, −35.2% emergency rate | |||||||||||||

| OF-MT: −39.1% fleet, −43.8% cost, −24.5% emergency rate | |||||||||||||

| OF-MT-R: −39.1% fleet, −49.5% cost, −42.8% emergency rate | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Yao, X.; Sun, L. Bayesian Network-Driven Demand Prediction and Multi-Trip Two-Echelon Routing for Fleet-Constrained Metropolitan Logistics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312609

Liu M, Yao X, Sun L. Bayesian Network-Driven Demand Prediction and Multi-Trip Two-Echelon Routing for Fleet-Constrained Metropolitan Logistics. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312609

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ming, Xiangye Yao, and Lihua Sun. 2025. "Bayesian Network-Driven Demand Prediction and Multi-Trip Two-Echelon Routing for Fleet-Constrained Metropolitan Logistics" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312609

APA StyleLiu, M., Yao, X., & Sun, L. (2025). Bayesian Network-Driven Demand Prediction and Multi-Trip Two-Echelon Routing for Fleet-Constrained Metropolitan Logistics. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312609