Abstract

An experimental technique was developed for two-dimensional Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) measurement of wall shear flow around a bubble growing under dissolved gas supersaturation. Carbonated water was used as dissolved-gas-supersaturated liquid, and its flow was created in a small container with a tube pump. An isolated CO2 bubble nucleated from an intentionally created scratch on the glass surface was placed in the flow. The mass-diffusion-driven growth of the bubble (from nucleation to detachment from the surface) was recorded using a video camera with backlighting; the radius of the detached bubble was below 1 mm in the present experimental conditions. The velocity field without and with the wall-attached bubble was obtained through PIV with the water (seeded with fluorescent particles) and with a planar laser sheet, which enables one to obtain local shear flow. With the measured liquid velocity at the bubble center, the particle Reynolds number was found to be below 1. The proposed PIV measurement technique allows for careful examination of bubble detachment dynamics and convective mass transfer around attached bubbles.

1. Introduction

Bubbles play significant roles in various fields and can have either positive or negative effects. For instance, in water electrolysis, bubble size affects the reaction efficiency at the electrodes [1]. In aeration reactions during wastewater treatment, bubble growth impacts the mass transfer of oxygen molecules [2]. Even in carbonated water, bubble behavior influences the taste [3]. That is, understanding the growth process of wall-attached bubbles is crucial for controlling their detachment size.

Many studies have investigated bubble growth under various conditions with experimental and simulation approaches [4,5,6,7,8]. For example, the case of an isolated bubble that is fixed in space and away from any boundaries (such as other bubbles or solid walls) was studied as a canonical problem; the radius of a bubble growing under constant gas supersaturation is shown to be proportional to the square root of time from nucleation [9,10]. In experiments, the target is the growth of bubbles attached at solid boundaries. Qin et al. (2021) explored the growth of bubbles on electrode surfaces during the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) and the effects of electrode morphology and wettability on bubble growth [11]. Yamashita and Ando (2017) observed the growth of bubbles in water aerated by oxygen microbubbles and analyzed it based on the Epstein–Plesset model that accounts for two-species (oxygen and nitrogen) diffusion phenomena [5]. Duhar and Colin (2006) focused on bubbles growing from gas injection through small orifices under viscous shear flow [12]. Li et al. (2023) examined the periodicity of bubble detachment in viscous shear flow [13]. In these experiments, bubble motion was recorded by a video camera, allowing for shape changes of the bubbles to be carefully examined. Satirtha K et al. (2023) numerically and experimentally demonstrated that forced convection significantly enhances bubble rise dynamics and electrolyte renewal in photoelectrochemical systems [14]. It is instructive to note that in most previous theoretical or numerical studies on the growth of wall-attached bubbles [13,15,16], the analysis was based on the liquid velocity field in the absence of the bubble in a one-way-coupling manner. However, in the immediate vicinity of a wall-attached bubble, the flow field will be altered due to the presence of the bubble. Such local variation in the flow field can in principle influence bubble growth and detachment and recent developments in microscale multiphase flow dynamics further highlight the importance of experimental visualization methods for resolving near-wall flow structures [17,18,19]. Hence, capturing the local velocity field in the presence of a wall-attached bubble is required to improve the validity of the analysis of bubble growth and detachment.

In this study, we develop a two-dimensional Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) technique to visualize shear flow around a bubble growing on a solid wall. The PIV method is widely applied in fluid dynamics research [20,21,22,23]. The application of PIV to the bubble growth problem is still limited [24,25].

Here, we aim to develop an experimental system for two-dimensional PIV measurement of shear flow around a wall-attached bubble growing under dissolved gas supersaturation. Our target is the growth of an isolated bubble sitting at a solid wall, which is suitable for simpler analysis. This work presents a direct measurement of the local shear flow around a wall-attached bubble using a two-dimensional Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) system, enabling both the visualization and quantification of flow disturbances around the growing bubble. The results provide new insights into the hydrodynamic mechanisms that govern bubble detachment and mass transfer. In what follows, we explain the experimental setup and show representative results from the visualization experiment.

2. Experimental Methods

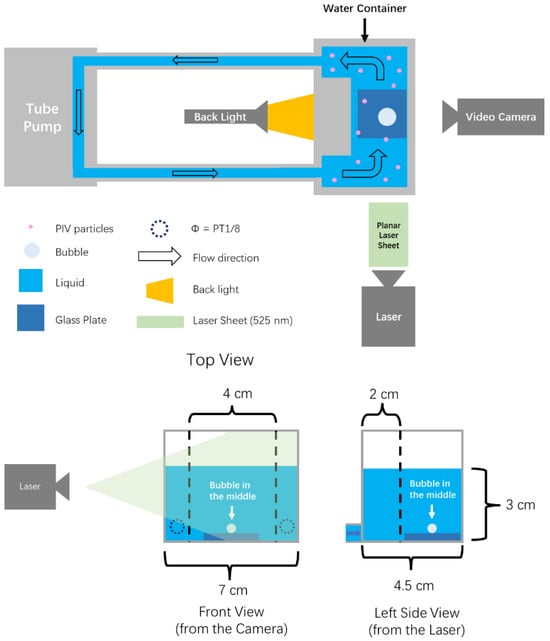

The experimental setup, illustrated in Figure 1, was designed to observe the growth of CO2 bubbles in carbonated water (Asahi Wilkinson Tansan 500 mL, Tokyo, Japan) under supersaturation conditions at atmospheric pressure. For the construction of volume flow, a transparent container (7 cm × 4.5 cm internal dimensions) was used, featuring a protruding acrylic block (2 cm deep, 4 cm wide) at the center of the back wall to create a channel-like flow region open to the atmosphere. The water level was maintained at 3 cm. To induce isolated bubble nucleation, a glass slide (with an area of 18 mm × 18 mm and thickness of 0.15 mm, Matsunami-glass, Osaka, Japan) with a scratch (created by a glass cutter) was placed on the container bottom, serving as a nucleation site [5]. The resulting flow channel had a cross-section of 3 cm × 2.5 cm, with a hydraulic diameter of 2.73 cm [26]. Flow was generated by connecting the container’s inlet and outlet to a peristaltic pump (As One TP-20SA, Osaka, Japan), with the volumetric flow rate varied between 0 and 75 mL/min. The peristaltic pump operated at a relatively low volumetric flow rate, resulting in a low flow velocity. Under these conditions, no noticeable pulsation was observed in the flow field. The water was at room temperature (22 °C) and was confirmed to be undisturbed under pumping.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental setup (top, front and side views).

For flow field measurements, two-dimensional Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) was employed. Fluorescent particles (FA-207, diameter 4 μm, Sinloihi Co., Kanagawa, Japan) were seeded into the water and illuminated using a continuous laser sheet with a wavelength of 525 nm (1 mm thick, Kato Koken KLD-G1, Kanagawa, Japan) from the side, inducing fluorescence. Their motion, driven by fluid advection, was captured using a video camera (KEYENCE VW600M, Osaka, Japan) with a 50× magnification lens (10 μm/pixel), which recorded the process at 30 fps with a shutter speed of 1/60 s. The velocity field was reconstructed by processing particle displacement using FlowExpert64 software (Ver. 1.2.12, Kato Koken, Kanagawa, Japan).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Visualization of the Flow Field with No Bubble

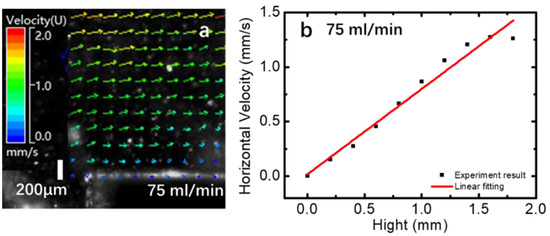

First, we examine the flow field with no bubble, which is to be used in bubble data analysis in the following section. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of liquid flow velocities over the glass surface at a volume flow rate of 75 mL/min. Figure 2a presents the corresponding PIV image, showing wall shear flow with the no-slip condition satisfied at the bottom wall. The velocity at 2 mm above the wall is approximately 1.25 mm/s. The Reynolds number for the channel flow is defined with the hydraulic diameter of its cross-section and the cross-sectionally averaged velocity; it is computed at 45 in this case, meaning that the flow is laminar. Figure 2b presents the measured average horizontal velocity as a function of height from the wall. From the linear fitting, the shear rate of the flow is calculated to be 0.77/s as a result of linear fitting with no-slip constraint (zero velocity at the wall). It is instructive to note that the PIV measurement can become less accurate near the (no-slip) solid wall. However, when it comes to computing particle Reynolds numbers for the wall shear flow with a bubble, we can obtain, with better accuracy, the liquid velocity at the distance of the bubble radius from the wall.

Figure 2.

(a) Velocity field (with no bubble) at volume flow rate of 75 mL/min through the container and (b) its average horizontal velocity as a function of height from the wall.

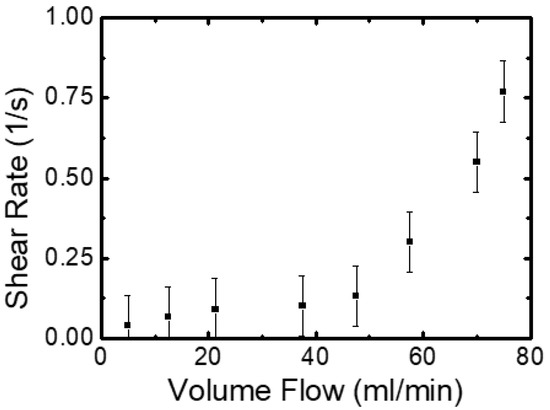

Figure 3 shows the shear rate of the wall shear flow as a function of the volume flow rate through the water container. It can be observed that at lower volume flows, from 0 to 40 mL/min, the shear rate increases slowly from 0 to approximately 0.15/s. However, for flow rates higher than 50 mL/min, the shear rate increases more rapidly. It follows that, by varying the volume flow, one can control the shear rate as an experimental parameter.

Figure 3.

Shear rate of the wall shear flow with varying volume flow rate through the container.

In the present experimental configuration, the inlet is positioned near the bottom of the container with a diameter of PT1/8 (approximately 10 mm), and the total water depth is set to 3 cm. Under these conditions, the upper region of the liquid remains relatively stagnant. This static layer introduces resistance to the horizontal flow developing near the bottom wall, particularly at positions farther from the wall. As a result, the measured velocity profile deviates downward from the ideal linear distribution typically observed in simple shear flows. This flow disturbance is considered to be one of the possible reasons for the nonlinear relationship observed between the volume flow rate and the calculated shear rate. However, in the near-wall region—especially within the vicinity of the growing bubble—the horizontal velocity profile remains approximately linear. Therefore, the deviation observed in the upper region has negligible influence on the local flow field used in the present analysis and does not affect the primary conclusions of this study.

3.2. Visualization of the Flow Field with the Bubble

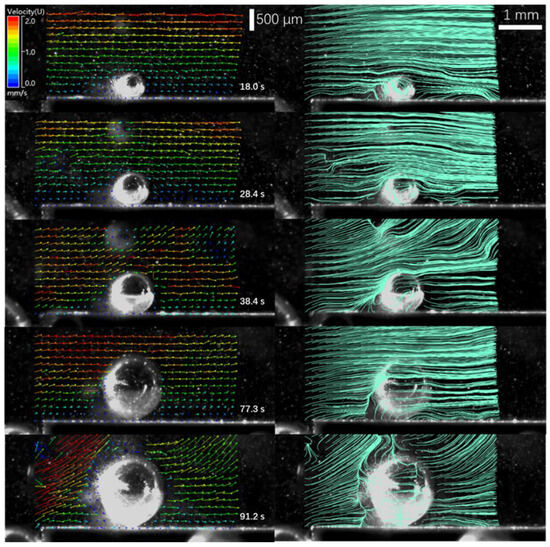

Next, we examine two-dimensional local flow fields in the vicinity of a growing CO2 bubble on the solid wall, using the PIV technique. Figure 4 presents velocity fields with a volume flow rate of 75 mL/min (at different times from bubble nucleation to one frame before detachment) and their corresponding streamlines. The growth of the bubble is driven by mass influx of carbon dioxide from the supersaturated water, and its evolution is presented in Figure S1. In this figure, it is clearly seen that the flow originally aligned along the solid surface is disturbed under the presence of the wall-attached bubble. When the bubble is small (at 18.0 s from nucleation), we do not clearly see a wake region in the downstream side of the bubble. However, as the bubble size increases, which corresponds to the increase in the particle Reynolds number as reported in Table 1, the streamlines tend to separate from the bubble interface, forming a large wake region in the downstream side. It is also important to note that the bubble tends to remain in its spherical shape in all stages: nucleation, growth, and detachment. The radius of the bubble, R, at the different times is documented in Table 1. Note that the values of the bubble radius contain an uncertainty of ±10 μm. The bubble-center velocity that is defined in the absence of the bubble and obtained from the data in Figure 2 is also reported as a function of the time from nucleation in the same table.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the velocity field around a growing bubble on the solid wall (left) and the corresponding streamlines (right). The volume flow rate was set at 75 mL/min.

Table 1.

Evolution of the bubble radius, liquid velocity at the bubble’s center (in the absence of the bubble), and particle Reynolds number and Weber number for flow around the bubble in Figure 4.

To interpret the flow pattern and the bubble shape, we introduce the (dimensionless) particle Reynolds number (Re) and Weber number (We), respectively [27,28]:

where Vp is the bubble-center velocity (in the absence of the bubble), dp = 2R is the diameter of the particle (or bubble), ν is the kinematic viscosity of water (1.0 × 10−6 m2/s), ρ is the density of water (1000 kg/m3), and σ is the surface tension of water (0.072 N/m). The Re and We numbers corresponding to Figure 4 are computed in Table 1. In the bubble growth process, the Re number remains smaller than unity; however, as the bubble size increases, the finite-Re-number effect comes into play, emphasizing flow separation with a broader wake region. In contrast, the We number remains much smaller than unity, meaning that hydrodynamic force is much less effective than surface tension. Furthermore, the capillary number (Ca = We/Re) and the Bond number (Bo = ρgL2/σ with gravitational acceleration g) are small, meaning that both viscous friction and buoyancy force are both minor in comparison to surface tension in this particular example. These observations are consistent with the experimental fact that the bubble remains spherical from its nucleation to detachment.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a two-dimensional PIV technique was developed to obtain a velocity field in the vicinity of a bubble sitting at a solid wall. Carbonated water was used as the working fluid, and its flow was created in a transparent container with a glass bottom. In this setup, an isolated bubble can be nucleated from a scratch on the glass bottom, subsequently growing under CO2 supersaturation. The local velocity field in the vicinity of the wall-attached bubble was obtained through two-dimensional PIV with a planar laser sheet. It follows from the PIV measurement for the particular case of small Weber and Bond numbers that the wake region behind the bubble becomes broader as the bubble size increases (and the particle Reynolds number increases).

Here, we demonstrated how to apply two-dimensional PIV to the study of diffusion-driven growth of bubbles in flowing liquid. For a more careful examination of bubble growth phenomena, there is a need to control the supersaturation level of dissolved gases [29]. Another future work is to extend the PIV technique to more complex three-dimensional flows [28,29], which can be combined with various advanced techniques and applied to complex situations. With access to three-dimensional velocity fields around a wall-attached bubble, one can in principle quantify the hydrodynamic force acting on the bubble and simulate the concentration field of dissolved gases, thereby allowing for the mass transfer across the bubble interface to be computed [30,31].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152212124/s1, Figure S1: Evolution of the radius of the bubble growing in the supersaturated water in Figure 4 of the main text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and K.A.; methodology, Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, K.A.; supervision, K.A.; funding acquisition, K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author acknowledges support from the KLL Ph.D. Program Research Grant for the research theme “The Effect of Fluid Field on Bubble Behavior”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, J.; et al. Ultrahigh Hydrogen Evolution Performance of Under-Water “Superaerophobic” MoS2 Nanostructured Electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2683–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Montes, F.J.; Galán, M.A. Oxygen Transfer from Growing Bubbles: Effect of the Physical Properties of the Liquid. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 128, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Martínez, P.; Enríquez, O.R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. Some Topics on the Physics of Bubble Dynamics in Beer. Beverages 2017, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, F.; Kuang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, H. Interfacial Nanobubbles’ Growth at the Initial Stage of Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Ando, K. Aeration of Water with Oxygen Microbubbles and Its Purging Effect. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 825, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustini, G. Hydrodynamic Analysis of Liquid Microlayer Formation in Nucleate Boiling of Water. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2024, 172, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, A.; Bluck, M.; Peakman, A. Applicability of Novel Critical Heat Flux Criteria to High Pressure Subcooled Flow CFD Simulations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 239, 126537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustini, G.; Issa, R.I. Modelling of Free Bubble Growth with Interface Capturing Computational Fluid Dynamics. Exp. Comput. Multiph. Flow 2023, 5, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, P.S.; Plesset, M.S. On the Stability of Gas Bubbles in Liquid-Gas Solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1950, 18, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, L.E. On the Dynamics of Phase Growth. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1995, 50, 3907–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Xie, T.; Zhou, D.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shang, Z.; Li, J.; Mohapatra, L.; Yu, J.; Xu, H.; et al. Kinetic Study of Electrochemically Produced Hydrogen Bubbles on Pt Electrodes with Tailored Geometries. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 2154–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhar, G.; Colin, C. Dynamics of Bubble Growth and Detachment in a Viscous Shear Flow. Phys. Fluids 2006, 18, 077101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Qian, Z. Diffusion-Driven Periodic Cavitation Bubbling from a Harvey-Type Crevice in Shear Flows. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.K.; Singh, A.; Mohan, R.; Shukla, A. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Bubble Hydrodynamics in Water Splitting: Effect of Electrolyte Inflow Velocity and Electrode Morphology on Cell Performance. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 17769–17782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favelukis, M.; Tadmor, Z.; Semiat, R. Bubble Growth in a Viscous Liquid in a Simple Shear Flow. AIChE J. 1999, 45, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; He, P.; Chen, H. Bubble Growth on Hydrophobic Rough Surfaces in the Shear Flow. Langmuir 2024, 40, 9630–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Xue, R.; Wu, Q.; Wang, B.; Fang, M.; Ruan, Q.; Liu, W.; Ren, Y. Polarization—Selective Dynamic Coupling: Electrorotation—Orbital Motion of Twin Colloids in Rotating Fields. Electrophoresis 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Yu, G.; Ren, Y. Many-Body Electrohydrodynamic Contact Dynamics in Alternating-Current Dielectrophoresis: Resolving Hierarchical Assembly of Soft Binary Colloids. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 082034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gong, X.; Tao, Y.; Liu, W. A Numerical Investigation of Enhanced Microfluidic Immunoassay by Multiple-Frequency Alternating-Current Electrothermal Convection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, P.; Avallone, G.; De Gregorio, F.; Romano, G.P.; Antonia, R.A. Spatial Resolution of PIV for the Measurement of Turbulence. Exp. Fluids 2007, 43, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, F. Overview of PIV in Supersonic Flows. In Particle Image Velocimetry: New Developments and Recent Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 445–463. ISBN 978-3-540-73528-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, F.; Ishikawa, M. A Review of the Recent PIV Studies—From the Basics to the Hybridization with CFD. J. Flow Control Meas. Vis. 2022, 10, 117–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingote, C.; Barghi Golezani, F.; Kharangate, C.R. Investigation of Fluid Flow during Flow Boiling inside a Horizontal Rectangular Channel with Single-Sided Heating Using Particle Image Velocimetry. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2024, 156, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.; Reithmuller, M.L. PIV in Two-Phase Flows: Simultaneous Bubble Sizing and Liquid Velocity Measurements; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pakleza, J.; Duluc, M.-C.; Kowalewski, T. Experimental Investigation of Vapor Bubble Growth. In Proceedings of the International Heat Transfer Conference 12, Grenoble, France, 18–23 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.M.; Majdalani, J. Viscous Fluid Flow; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Frohn, A.; Roth, N. Dynamics of Droplets; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; ISBN 3-540-65887-4. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S.; Balachandar, S. Modeling Approaches and Computational Methods for Particle-Laden Turbulent Flows; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-323-90134-5. [Google Scholar]

- Enríquez, O.R.; Hummelink, C.; Bruggert, G.-W.; Lohse, D.; Prosperetti, A.; Van Der Meer, D.; Sun, C. Growing Bubbles in a Slightly Supersaturated Liquid Solution. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 065111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas-López, P.; Soto, Á.M.; Parrales, M.A.; Van Der Meer, D.; Lohse, D.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. The History Effect on Bubble Growth and Dissolution. Part 2. Experiments and Simulations of a Spherical Bubble Attached to a Horizontal Flat Plate. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 820, 479–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B. Transport Phenomena. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2002, 55, R1–R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).