Abstract

A landform is a physical feature of the Earth’s surface with its own recognizable shape. Most current automated landform identification methods use Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) techniques. Such methods segment the terrain into landform elements and assemble them into topographic objects and landforms. Usually, these methods are specific to the landform to be identified. However, geomorphologist experts can contextually recognize any landform on the Earth’s surface in relation to its environment. They have a holistic view of the landscape, adopting a physiographic approach for the interpretation of the observed regions, the objects that they contain and their relationships. Moreover, geomorphological processes leave marks on the Earth’s surface that enable geomorphologists to identify homogeneous regions by recognizing features known as structural elements. In this paper, we show that the physiographic approach can be formalized and that the context of appearance of a landform and its association with other types of landforms can be represented as a landsystem. We propose a conceptual model that organizes the main concepts and relationships characterizing the physiographic approach: they are used to formalize landsystems, landforms and structural elements. The approach is illustrated using a case study of the identification of landsystems characteristic of mountainous glacial valleys. We developed a software to automatically identify landsystems, in a way that is compatible with the geomorphologists’ physiographic approach. The core of this system is a knowledge base implemented as a Neo4j graph database. We also provide details about the logical transformation of the conceptual model and the corresponding ontologies in Noe4j structures. The tool automates the identification of landsystems in accordance with geomorphological practices, facilitating the integration of expert knowledge in the computational workflows.

1. Introduction

Geomorphology is the study of landforms that appear on the Earth’s surface. A landform is a physical feature with a characteristic, recognizable shape [1]. In this research we are particularly interested in landforms that can be described according to two approaches: the topographic and the physiographic approaches.

In the topographic approach, a landform is defined as an individual geomorphologic element, produced by a set of geomorphologic processes in a region of the Earth’s surface [2]. A landform has a characteristic shape which is identified by a set of morphometric elements, generally based on the assembly of homogeneous regions known as landform elements. A landform element is a ‘smaller’ geomorphologic element primarily characterized by its morphology using parameters such as shape, slope and orientation. ‘Bottom of valley’ and ‘slope’ are examples of landform elements.

With the increasing availability of data, automatic and semi-automatic methods based on the topographic approach have become increasingly used to identify landforms, considering their morphometric characteristics [3]. The first methods were based on a quantitative data analysis of local terrain descriptors computed at the pixel level. The methods then evolved towards Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) approaches to go beyond the limits of pixel-level analysis and to study phenomena at different geographical scales. Using OBIA approaches, interpretation is no longer carried out at the pixel level and seeks to identify so-called objects formed from homogeneous groups of pixels. The identification of objects is achieved by image segmentation using indices such as the ‘degree of slope’ or by other techniques based on the functional grouping of pixels. An example is the identification of dunes [4,5]. Notably, all these methods are data dependent. Indeed, the specification of segmentation rules using OBIA must be determined in advance for specific datatypes [6]. In addition, these methods are designed for specific scales and landforms [7,8]. Therefore, one needs to redefine and adjust the parameters for each new study. Moreover, these methods are not generalizable because they only perform image analysis and cannot consider the geomorphological context.

More recently, researchers developed machine learning techniques using neural networks to detect landforms in image data. Machine learning algorithms are used because they have good recognition and information extraction capabilities [9] and they can extract information from multiple large data sources [10]. However, while not requiring the preliminary definition of parameters, machine learning (and deep learning) approaches require large datasets to learn object patterns and require a lot of preparatory work. Moreover, the results of these learning techniques are still limited [11].

Overall, techniques that automatically process images (OBIA, deep learning) do not reflect the practical approach of geomorphologists and lack the ability to justify their results, since they cannot draw on geomorphologists’ specialized knowledge [12]. Such inability to integrate geomorphologists’ expertise is an important limitation that so-called cognitive approaches attempt to remedy by drawing on the knowledge and perception of geomorphologists. Structured knowledge models were proposed to capture and formalize the expert knowledge to improve landform classification approaches [7]. However, the perception of landforms depends on the specialist’s experience and on the context of observation [13].

In this paper we suggest that such models should also be able to formalize the geomorphological context of appearance of landform. Adopting a cognitive approach, it can be observed that geomorphologists usually recognize landforms on the Earth’s surface by associating them with the natural processes that have shaped the landscape over geological time. This observation leads to the physiographic approach that has long been used by geographers and geomorphologists for the qualitative analysis of the Earth’s surface.

Specialists think of the geographic space as a dynamic whole, made up of spatial structures (including landforms) that evolve over time and space [14]. The visible part of this ensemble defines what can be named the landscape, which is shaped by phenomena (i.e., processes) that are mostly beyond human perception [14]. These processes leave marks on the Earth’s surface that enable geomorphologists to identify homogeneous regions by recognizing features known as structural elements [14,15]. In practice, geomorphologists first identify homogeneous global regions of the Earth’s surface by identifying structural elements which are typical of global geomorphological processes that have influenced these regions. Then, these specialists observe smaller regions within these global regions, recognizing more detailed structural elements that correspond to other processes that shaped the landscape. They can also identify spatial relationships (such as contiguity and inclusion) between these smaller regions. They continue to determine spatially nested regions until they can identify the landforms contained in them. In this hierarchical approach, the preferred relationship is the spatial inclusion (‘containment’) of objects (landforms) within regions (representing the context of appearance of landforms).

For example, to identify marine deltas (landforms created by the deposition of alluvial deposits at the mouth of a river), geomorphologists observe emerged areas, considering their altitude in relation to sea level as a structural element. Then, they observe coastal zones from the infralittoral limit, which serves as a structural element. In coastal zones, they observe river outcrops that emerge from the coastal limit, as a structural element, to identify deltaic forms that are the structural elements that define deltas.

The geomorphologists’ physiographic classifications are used to organize the complexity of identifiable systems on the Earth’s surface by defining and delimiting spatial units that are ecologically and functionally homogeneous at any scale [16]. These regions can be associated with homogeneous natural geographic systems called landsystems [17]. When identifying a landsystem in a study area, geomorphologists rely on their expertise to anticipate which kinds of landforms can be observed. Sochava defined landsystems as ‘terrestrial spaces of varying dimensions (ranging from the geographical environment as a whole, to an elementary physical geographical geofacies), where the individual components of nature are in a system connected with one another and as a definite entirety’ [17]. This holistic view is aligned with the geomorphologist’s physiographic approach [18] and draws on their knowledge and interpretation of the observed regions and their relationships [16].

In this paper, we propose to take advantage of the physiographic approach to automatically identify the context of appearance (named ‘geomorphologic context’) of landforms in the landscape. We hypothesize that landform identification should be facilitated by the determination of the geomorphologic context as a set of nested regions associated with structural elements that are relevant to the geomorphologist’s analysis. Therefore, the proposed approach does not put the emphasis on geomorphological processes themselves, but rather on their context of occurrence and their products: landforms and landsystems. We suggest that the introduction of a landsystem recognition capability in landform classification systems would provide geomorphologists with contextual geographic information that can be exploited for landform identification. Here, we present the foundations of the approach that we propose to build such a landsystem recognition capability by modeling the relevant knowledge of expert geomorphologists.

As a first step, we propose a conceptual model to formalize the experts’ knowledge related to the physiographic approach. Based on this model, we propose a method to help geomorphologists identify landsystems and relevant structural elements to model the geomorphological context as part of their study of landforms. We then present the foundations of a software tool that we developed to support this approach and to automatically identify landsystems, based on the way geomorphologists work.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, the geomorphologists’ knowledge representation is reviewed to propose precise definitions of concepts relevant to landsystem recognition and the link between the physiographic knowledge and the topographic approach. Section 3 introduces a case study that is used to illustrate the approach throughout the paper. In Section 3, a conceptual model is presented to capture the main concepts and relationships that formalize landsystems, landforms and structural elements. Section 4 presents an overview of the application which supports the proposed approach using a Neo4j graph database. Section 5 details the logical model that supports the transformation of the conceptual model into a structure that is compatible with the Neo4j framework. In Section 6, the logical model is applied to the case study. Results are presented and discussed in Section 7. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and presents some research perspectives.

2. Geomorphologic Knowledge Representation

Using a knowledge elicitation approach [19] and working collaboratively with an expert geomorphologist, the relevant geomorphologic fundamental and practical knowledge was collected from the specialized literature and enhanced with field-level expertise. Such a knowledge acquisition process was led by a knowledge engineer who ensured the coherence of both the knowledge itself and its sources. Chosen sources of relevant knowledge were peer-reviewed, and throughout the acquisition process cross comparisons were systematically performed between different sources within the relevant domain. In the remainder of this paper, it will be shown how such knowledge can be used to develop an approach to identify and model landsystems.

The Physiographic Approach: Concepts and Principles

Geomorphologists usually study and observe the landscape from a holistic and ‘systemic’ point of view [20,21]. They observe and analyze the landscape elements that characterize geomorphologic elements and interpret the processes that have shaped them. Several work sessions with our expert geomorphologist enabled us to elicit the relevant knowledge and to identify the main structures characterizing the physiographic approach.

A geomorphologic element is defined as an object located in a region of the Earth’s surface in which geomorphological processes (i.e., Earth’s surface processes) leave imprints that make them recognizable. These imprints are characteristic of the geomorphologic object and are named ‘structural elements’ [14]. A structural element is thus a relevant characteristic associated with a region that serves to recognize a geomorphologic feature resulting from the actions of one or several of the Earth’s surface processes. A structural element can be one of different kinds such as geological, climatic and topographical.

Three main concepts therefore need to be considered: (1) the area capturing the spatial dimension; (2) the geomorphologic element representing any geomorphologic feature, such as landforms and landsystems, that are of interest to the geomorphologist; and (3) the structural element capturing the imprints of Earth’s surface processes observed by geomorphologists.

To manage the complexity of the features of the Earth’s surface, geomorphologists adopt the classical approach of spatial knowledge hierarchization [22]. Consequently, a geomorphologist first observes the study area at a global level, recognizing larger areas where more global Earth’s surface processes apply. For example, they can first identify emerged lands when looking for landforms above sea level. Then, in these areas, they look for distinctive signs of the influence of other Earth’s surface processes. For example, they can consider signs related to the influence of glaciation in land areas. These signs lead the geomorphologist to identify the structural elements that they can recognize and measure to identify the influence of Earth’s surface processes in a region.

A structural element can thus be used to divide wider areas into sub-areas, reflecting both the influence of the main process (associated with the overall area) and of the Earth’s surface processes (associated with the structural elements) having a local influence. And within each sub-area, it is possible to recognize other signs reflecting the influence of even more local Earth’s surface processes and variabilities in the geological setting, such as the lithology influencing, for example, differential erosion. The principle of hierarchy divides the geographic space into nested areas, each reflecting the combined influences of several of the Earth’s surface processes.

In this hierarchical approach, the larger regions associated with more global processes provide the context in which more local regions associated with more precise structural elements can be identified. Considering this nesting at different levels, we hypothesize that these regions observed by geomorphologists can be used to define a geomorphological context in which one may identify landforms. As mentioned in Section 1, these regions can be associated with homogeneous natural geographic systems named landsystems. We define a landsystem as an assemblage of geomorphologic elements; this assemblage being characteristic of the observed landscape. Geographers and geomorphologists define landsystems as homogeneous regions that differ from adjacent landsystems. Hence, landsystems provide a natural segmentation of the terrain in which one can observe the effects of Earth’s surface processes and the resulting landforms. Interestingly, [2] pointed out that landforms do not cover the whole of the Earth’s surface: there are ‘surfaces left between landforms’ which are not usually considered in classifications. Indeed, such residual surfaces may appear in a landsystem. In our approach we consider them as important elements when partitioning the area associated with a landsystem.

As mentioned earlier, areas characterized by structural elements define the context of smaller areas characterized by more local structural elements. As such, landsystems form a spatial hierarchy where smaller landsystems are contained in larger landsystems [23]. In this hierarchy, a landsystem is therefore characterized by the combination of local structural elements [23]. Each geomorphologic element, whether a landsystem or a landform, is located in specific areas. This hierarchical structure leads to a full hierarchical partition of the geographic space where the area of a landsystem is obtained by the intersection of areas of its parent landsystems. For example, glacial mountainous landsystems are obtained by the intersection of glacial landsystems and mountainous landsystems. Furthermore, a landsystem can be partitioned into a set of landforms and leftover surfaces so that one can preserve a spatial continuum in the morphometric description of the terrain [2].

To sum up, we propose modeling the geomorphological context as an ensemble of landsystems associated with regions which have typical and recognizable characteristics (i.e., structural elements) differentiating them from adjacent regions. The regions associated with landsystems can also be viewed at different levels of detail and partitioned into subregions characterized by more specific structuring elements.

Table 1 displays the definitions of the main concepts that will be used to establish the conceptual model.

Table 1.

Main concepts of the physiographic approach.

3. Conceptual Modeling

An important step of our approach is the creation of a conceptual model that organizes the above-mentioned concepts in a data structure that can be used by automated applications. This conceptual model is presented and discussed in Section 3.2. Section 3.1 presents the case study which is used in this paper to illustrate the proposed approach.

3.1. Case Study: Mountainous Glacial Valley

As a case study we consider the identification of mountainous glacial valleys. Applying the physiographic approach and observing the areas characterized by landmass, geomorphologists can recognize subregions that were influenced by glaciations. Then, in such areas they can identify subregions with a mountain topography. Within these subregions, they can recognize sub-areas by identifying signs of glacial erosion. In this way, they can recognize mountainous glacial valleys which result from the combined influences of these various geomorphological processes.

By definition, a mountainous glacial valley is the consequence of tectonic processes acting on the lithosphere on which glacial erosion processes occurred [25]. These processes may have been applied to landmass areas of various extents, over several time intervals, and their effects can be observed at different levels of detail. Hence, it seems appropriate to use a landsystem-based approach to model the context of appearance of mountainous glacial valleys and the associated landforms. A focused literature review and several elicitation sessions allowed us to identify appropriate landsystems and their associated structural elements.

It is well known that tectonic processes led to the formation of emerged lands (landmass) and mountain ranges. The structural element allowing characterizing landmass is the ‘altitude above sea level’. Moreover, mountain ranges can be observed on landmass by considering their elevated positions relative to the surrounding landscape: they are modeled as mountainous landsystems. Glaciation processes lead to the creation of glacial landsystems. In mountainous regions, the combination of processes creates characteristic areas that are modeled as mountainous glacial. More specifically, a glacial valley is formed when a glacier flows through it, erodes it and widens its bottom. We call this the mountainous glacial valley landsystem (MGVLS for short), a landsystem that is part of a mountainous glacial landsystem. It is shaped by glacial erosion and is characterized by an elongated shape. Table 2 lists the above-mentioned landsystems (LS) and the associated structural elements (SE) that were identified in this case study.

Table 2.

Structural elements and hierarchical landsystem parents from which the mountainous glacial valley landsystem inherits.

3.2. Conceptual Model

The proposed conceptual model provides a synthetic view of the knowledge required to recognize landsystems. In this subsection we provide precise definitions of the different notions that are structured in the conceptual model.

A landsystem, as any other geomorphologic element, is not an independent feature: it is defined in relation to other geomorphologic elements. Four categories of geomorphologic elements have been identified: (a) the landsystem; (b) the landform; (c) the leftover surface; and (d) the landform element.

Landform elements are elementary components of landforms. Each landform element is a homogeneous part of the terrain. The association of several landform elements can be used to characterize a specific landform. For example, identifying landform elements allows for defining landforms when using OBIA approaches. Hence, we have a way to relate the physiographic approach and the object-based topographic approaches.

A landform is viewed as an individual object with a characteristic shape. Since both landform elements and landforms are characterized by their shapes, the structural elements that are associated with them are morphometric elements.

We define leftover surfaces as geomorphologic elements whose spatial extension may not currently be of interest to the geomorphologist, but which fill the gaps between the landforms contained in a landsystem.

A landsystem is associated with an area containing an assemblage of landforms and leftover surfaces. As already mentioned, the notion of landsystem provides the contextual knowledge from which a landform can be identified. It results from the action of Earth’s surface processes characterized by physiographic structural elements. Since landforms are also morphometric elements that result from these processes, a landsystem can be associated with the possible landforms that can be found in the associated area.

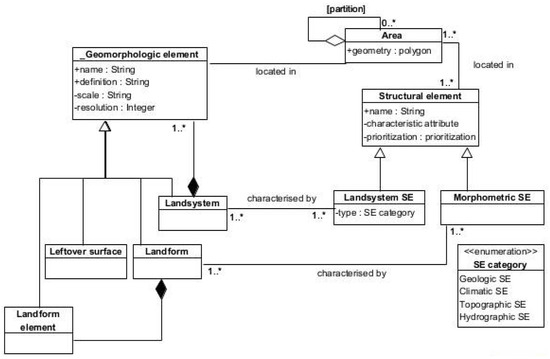

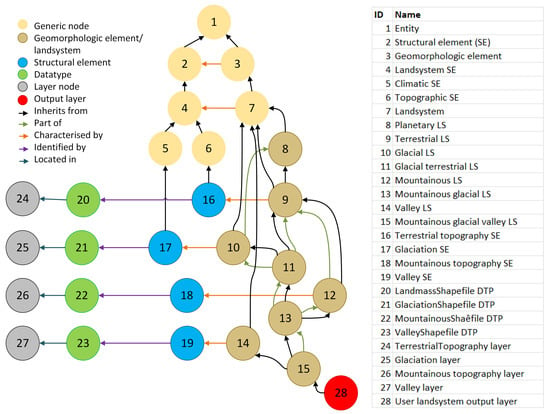

Figure 1 displays the proposed conceptual model, using a UML class model convention [26]. In this model, a Geomorphologic element is a generic concept which captures the common properties of landsystems, landforms, leftover surfaces and landform elements. Therefore, there are inheritance relationships (arrows with a triangle) between these concepts and the concept Geomorphologic element. These elements, being specializations of Geomorphologic element, inherit the relationship located-in with the Area concept. This relationship denotes that each landsystem, landform, landform element and leftover surface is associated with specific areas. Moreover, the aggregation relation (relation with a diamond and denoted [partition]) between areas indicates that the division of the geographic space in these areas forms a spatial partition. This hierarchical representation of regions, defined by various types of geomorphological elements, introduces into the model a set of geomorphological components distributed across distinct levels of granularity.

Figure 1.

Generic conceptual model. Arrows mark inheritance, plain diamond are part-of, numbers at the ends of associations are cardinality.

Now, we can discuss the Landsystem concept which is central to our approach. In the conceptual model, we observe that a Landsystem is an aggregation of Geomorphologic elements (displayed by the black diamond relation), including other landsystems, landforms and leftover surfaces, all of which are spatially embedded in the landsystem. Hence, considering the inheritance relationship and the located-in relationship with the Area concept, the area of a landsystem is decomposed into sub-areas which constitute a partition; each of these sub-areas are associated with either a ‘sub-landsystem’, a landform or a leftover surface. This decomposition applies recursively to sub-landsystems that can also be decomposed in the same way. We obtain the conceptual representation of the hierarchical decomposition of the geographic space discussed above.

While landsystems are geomorphological elements described according to a physiographic approach, landforms describe topographic features characterized by morphometric elements. They are discrete elements of the terrain surface and do not form a partition. Because landforms are the results of geo-processes that lead to landsystems, landforms are always located within landsystems.

Let us look at the concept of Leftover surface. Considering a landsystem Ls and its associated area A(Ls), a geomorphologist may identify in A(Ls) a number of landforms, each of which being associated with an area that characterizes its spatial extension in the geographic space. However, these areas may not be contiguous, and their spatial union may not constitute a spatial partition of A(Ls). Therefore, we introduce the Leftover surface, which is the spatial complement of these embedded areas, to provide a partition of A(Ls). The leftover surfaces may not be of immediate interest to a geomorphologist, but they are nonetheless important areas that may be analyzed later on.

The structural element concept is introduced in the model to characterize landsystems and landforms. Two kinds of structural elements are considered. Landsystem structural elements characterize landsystems, according to the physiographical approach. Morphometric structural elements characterize landforms, corresponding to topographic features. Each landsystem or landform is associated with one or several Structural elements. This association corresponds to the assumption that each of these geomorphologic elements can be identified by a set of characteristic marks (i.e., imprints) observed in the landscape, with each mark being associated with a geo-process according to the physiographic approach. Leftover surfaces are elements within a landsystem that are not considered by the geomorphologist as having morphometric features of interest. They are thus not characterized by any structural element.

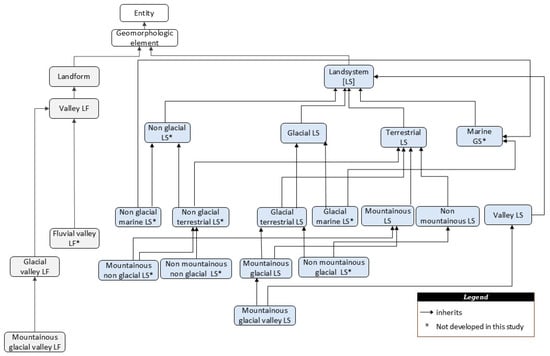

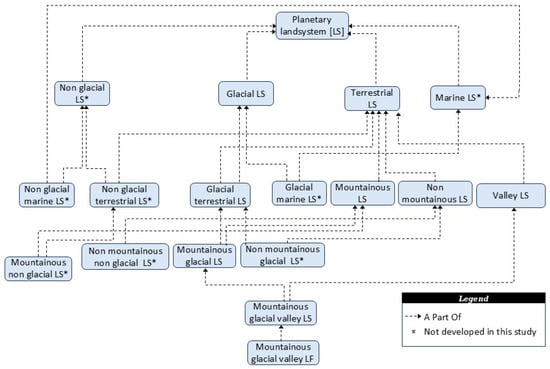

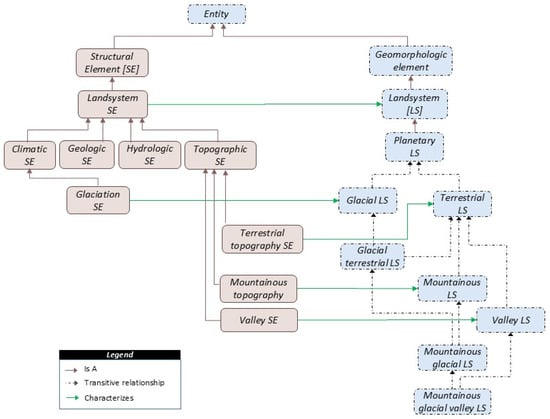

This conceptual model can be used to develop domain ontologies for different sub-domains of geomorphology such as glacial landsystems and landslides. As an illustration, we present the ontology for our case study of a mountainous glacial valley landsystem. The concepts of the domain ontology extend the classes Landsystem and Structural element of the conceptual model (Figure 1). For the sake of clarity, we present this domain ontology using several figures, each highlighting a fundamental relationship displayed in the conceptual model: (1) the inheritance relationship (Figure 2); (2) the part-of relationship (Figure 3) that captures the aggregation relationship between areas in the conceptual model; (3) the association between landsystems and structural elements (Figure 4) which captures the relationship characterized-by between the landsystem and structural element in the conceptual model.

Figure 2.

The inheritance relationship of the mountainous glacial valley landsystem domain ontology.

Figure 3.

‘Part-of’ relationship of the mountainous glacial valley landsystem domain ontology.

Figure 4.

‘Characterizes’ relationship of the mountainous glacial valley landsystem domain ontology.

The design of an ontology depends on the definitions which are chosen for the different concepts that are integrated in the data structure. In Section 3.1 we presented the main concepts and their properties that were used to create this ontology. Figure 2 presents the inheritance relationship between the main concepts of the proposed ontology. Since Landsystem and Landform are the two main semantic categories that are detailed in this application domain, there are two main parts in this ontology: the inheritance structure of Landsystem (concepts in blue boxes) and the inheritance structure of Landform (concepts in gray boxes).

Considering the inheritance of landsystems, we see that Mountainous glacial valley LS inherits from Mountainous glacial LS and Valley LS. Mountainous glacial LS inherits from Mountainous LS and Glacial terrestrial LS while Valley LS inherits from Terrestrial LS. Moreover, Mountainous LS inherits from Terrestrial LS, while Glacial terrestrial LS inherits from Glacial LS and Terrestrial LS. Considering the landform inheritance, Valley LF inherits from Landform. Then, both Fluvial valley LF and Glacial valley LF inherit from Valley LF. Finally, Mountainous glacial valley LF, the landform relevant to our case study, inherits from Glacial valley LF.

As we observed in the conceptual model, a landsystem is composed of characteristic landforms that inherit its properties. Examples of landforms that can be found in a Mountainous glacial LS are the cirque or the moraine. These landforms have their own morphometric structural elements. Geomorphologists looking for glacial landforms can also consider the glacial valley as a landform. Indeed, the glacial valley is defined as a U-shaped valley bounded by two shoulders. The Glacial valley LF inherits from the properties of the Valley LF (defined as an elongated depression). In this specific case, the Glacial valley LS and the Glacial valley LF are two kinds of geomorphological elements. The Glacial valley LS is an area within which the glacial erosion process has occurred, encompassing the Glacial valley LF which is the exact area where the glacier carved the ground. This distinction allows for a partition of the terrain, according to the physiographic approach and the identification of landforms, based on their morphometric characteristics. Because a landsystem defines the context of appearance of a landform, the Glacial valley LF should be within a Glacial valley LS.

The spatial parthood relationship between areas is displayed in Figure 3: it captures the spatial decomposition of the geographic space in nested landsystems (LS). Let us recall that in the conceptual model (Figure 1), the spatial decomposition applies to the areas associated with the landsystems. This property is denoted in the ontology by using the part-of relationship (dashed arrows) in Figure 3.

Looking at the bottom of the hierarchy in Figure 3, a Mountainous glacial valley LF is part-of a Mountainous glacial valley LS. Mountainous glacial valley LS is part-of a Mountainous glacial LS. A Mountainous glacial LS is defined as a landsystem located in a rugged glacial region having a higher altitude relative to the surrounding regions. Hence, a Mountainous glacial LS is part-of both Mountainous LS and Glacial terrestrial LS. A Glacial terrestrial LS is a landsystem defined by a region of the emerged Earth surface that has been glaciated in the past or is glaciated today. Moreover, a Mountainous LS is part-of a Terrestrial LS and a Glacial terrestrial LS is part-of both a Glacial LS and Terrestrial LS. A Glacial LS is a landsystem defined by a region of the Earth’s surface that has been glaciated in the past or is glaciated today and a Terrestrial LS is a landsystem defined by an area of emerged earth (continent, island, etc.).

Using green arrows, Figure 4 displays the associations between Landsystems and Structural elements, which is also an important part of our ontology. A landsystem is directly characterized by several structural elements; but, because it inherits from other landsystems, a landsystem is also characterized by the structural elements of its parent landsystems. Considering the parent landsystems displayed in Figure 2 and according to Table 2, we can see that Mountainous glacial valley LS is characterized by the structural elements Glaciation influence SE, Terrestrial topography SE, Mountainous topography SE and Valley SE.

Using such a domain ontology, the goal of this work is to develop a software that can automatically identify landsystems in a way that is compatible with the geomorphologists’ physiographic approach.

Considering the generality of the proposed model, let us emphasize that the conceptual model (Figure 1) is generic and applies to any domain. The upper parts of the ontologies (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) are also generic. However, when dealing with a new domain such as the study of deltaic landforms, these ontologies need to be expanded. This modeling activity will be carried out by the knowledge engineer and expert geomorphologists and the models, as well as the system, will be updated (see Section 4). The good news is that when a new domain is introduced in the system, it will be available for subsequent studies in this domain.

4. Structure of a Graph Database Application for Landsystem Identification

The domain ontology is composed of categories that describe the different geomorphological elements and structural elements. While definitions are derived from the same conceptual model, they each have their own properties and do not follow a common schema. Moreover, an ontology cannot be easily implemented using a relational model that enforces a fixed data schema. Furthermore, the ontology forms a complex network of concepts (a lattice), hierarchically structuring landsystems which are related to different structural elements. For all these reasons, we chose a graph-based data representation that is more efficient to model domain ontologies and to handle their contents using knowledge graphs.

The most widely used format for knowledge graphs is the triplestore where data are stored in RDF files. Such data can be queried using the SPARQL language and GeoSPARQL to handle spatial data. However, RDF is based on an XML format which is not the most efficient way to process data. Furthermore, linking spatial data across an RDF-based system and managing spatial data within such a system requires the use of external tools that involve additional spatial data exportation and management functionalities. Therefore, we chose another solution based on a graph database system that provides an efficient graph storage solution as well as a query language for handling large volumes of data and to infer new knowledge. The Neo4j database system [27] was chosen. Neo4j has its own query language, Cypher, that is more expressive and powerful than SPARQL. It also provides an extension, Neo4j Spatial for handling spatial data. An interface was also produced to encapsulate the queries. The interface offers a menu for users to load their data and select landsystems to look for, allowing them to avoid handling Cypher queries.

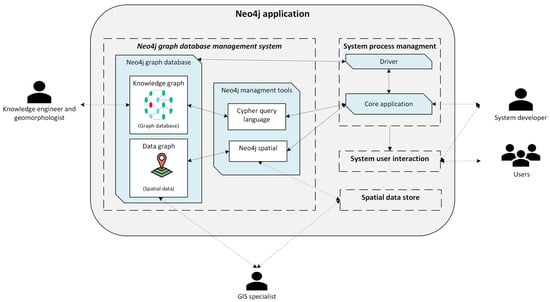

Figure 5 presents the main components of the architecture of our Neo4j application. The main actors (represented as stickman icons) are displayed in relation to the relevant architectural components. Data are stored in the Neo4j graph database (left blue trimmed-corner rectangle). A Neo4j graph database is composed of nodes and edges. A node represents a data object. An object is described by its properties and can be associated with labels that define different categories of the object. A graph database does not rely on a rigid data schema as a relational database does: each node can have its own properties. Relationships between nodes are represented by edges. Edges can also have their own properties and labels. The graph query language Cypher (top-middle white rectangle) allows for specifying queries that apply to subgraphs and can use propagation mechanisms through the graphs. Neo4j is modular and various extensions can be added to provide additional management tools. One extension of interest to us is Neo4j Spatial (bottom-middle white rectangle). It provides functions to handle and structure spatial data with geometrical features.

Figure 5.

Landsystem identification application.

More technically, let us consider how the data graph stores spatial data. Spatial data are stored in ‘spatial layers’. A spatial layer contains spatial data corresponding to a collection of spatial entities (geographic classes) having the same geometry types and semantic attributes. Data specifying land plots or patches, as well as a hydrographic network, are examples of spatial data that can be stored in spatial layers. An empty spatial layer can be created first and spatial data can then be imported in this empty spatial layer.

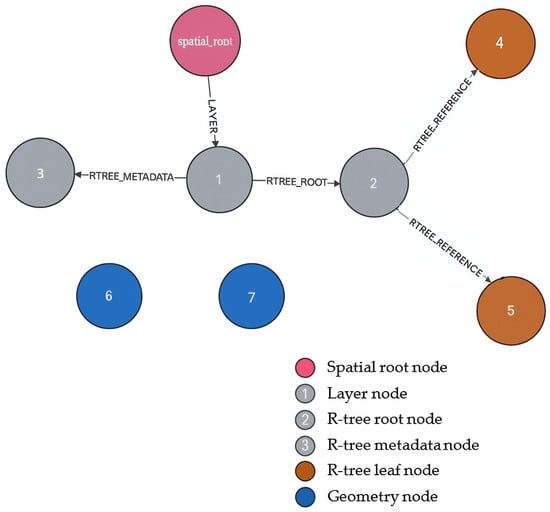

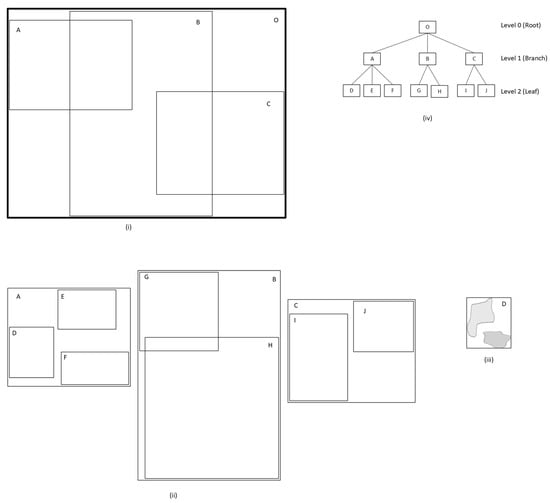

A spatial layer is organized as a subgraph of the graph database (Figure 6). All spatial layers are connected to a top node called spatial root. Each layer is composed of several nodes representing the layer, the spatial data and an R-tree [28] that serves as a spatial index. First, Neo4J provides a node called Layer node (node 1 in Figure 6) which contains general attributes of the spatial data such as the name and spatial reference information. A second node (node 3) contains metadata such as the total of spatial entities contained in the layer. A third node is the root of the R-tree (node 2) that contains the minimal rectangle (bounding box) delimiting the spatial layer. Figure 7 illustrates a representation of an R-tree. An R-tree is composed of a hierarchy of boxes in different levels from root cells (Level 0 in Figure 7) to children bounding boxes (D from F in Level 1 in Figure 7). This hierarchy provides subspaces of each bounding box of each spatial entity through the cells. Such a subspace allows for simplifying access to each spatial entity delimited by its bounding box. In Neo4j, the R-tree is composed of a hierarchy of nodes where each node is a cell of the R-tree with its bounding box. Leaves of the R-tree (brown nodes in Figure 6) contain the bounding boxes of the spatial entities and the ID of the spatial entities of the spatial data. Geometries and semantic attributes of the spatial entities are stored in a sixth type of node (blue nodes in Figure 6) in the Neo4J database. Access to spatial entities is achieved through the nodes of the R-tree which allow for recovering the geometry of each spatial entity using its identifier.

Figure 6.

Structure of spatial data in Neo4j.

Figure 7.

Representation of an R-tree: (i) Bounding box in level 0, (ii) Bounding boxes in level 1, (iii) Illustration of geometries in a bounding box D, (iv) Hierarchy level in an R-treeix Hierarchy level in an R-tree.

An example of a spatial layer is a set of polygons representing landmasses. The set of polygons can be delimited by a minimal rectangle (a bounding box) stored in the root node (node 2 in Figure 6) of the R-tree. Each spatial entity of landmasses is represented by a polygon of land which has its own bounding box. Each bounding box (rectangle represented by capital letter in Figure 7) is stored in a reference node (brown node in Figure 6) as an R-tree leaf node. In the simple example of Figure 6, there are only two polygons (nodes 6 and 7) and the hierarchy corresponds to nodes 2, 4 and 5. The geometry of each polygon is stored in another node (blue node). The identifier id of the geometry node of each polygon is stored as an attribute in the relevant R-tree leaf node that contains the bounding box of the geometry.

The Cypher interpreter and the Neo4J spatial extension provide the tools needed to manage the graph database (blue trimmed-corner rectangle in the middle of Figure 5). The Cypher language can also be easily extended by embedding functions written with other programming languages thanks to the Neo4j driver (top-right blue trimmed-corner rectangle). For example, queries can include spatial operations written in Java to generate new spatial objects.

Our application consists of four main components (big, dashed rectangles in Figure 5). The left dashed rectangle represents the Neo4j graph database management system which contains the above-mentioned Neo4j graph management tools and the Neo4j graph database.

The Neo4j graph database contains the knowledge graph and the data graph. The knowledge graph (top-right white rectangle) is initialized by nodes and edges derived from the domain ontology created by the knowledge engineer in collaboration with the geomorphologist (actor on the left side of Figure 5).

In our application, spatial data are imported from an external Geographic Information System (GIS). The data relevant to the user’s study is prepared by a GIS specialist and stored in a spatial data store (dashed rectangle, bottom right of Figure 5). Thanks to the extension Neo4J Spatial, the data are extracted from the spatial data store, formatted and included in the graph data (bottom-left white rectangle). They are ready to be used in our Neo4J application.

The system process management (right dashed rectangle in Figure 5) constitutes the heart of the system. The core application (blue trimmed-corner rectangle) is the program developed by the system developer to control the whole system. The core application can connect to the Neo4j graph database thanks to the Neo4j driver. The connection to the driver enables the system to perform queries on the knowledge base and on the spatial database, using, respectively, the Cypher and Neo4j spatial management tools mentioned above.

Finally, the bottom-right dashed rectangle corresponds to the system user interaction module which manages the user’s interactions with the application. The system developer programs this third component in conjunction with the development of the system process management module using the Java language.

5. The Logical Model and the Data Level

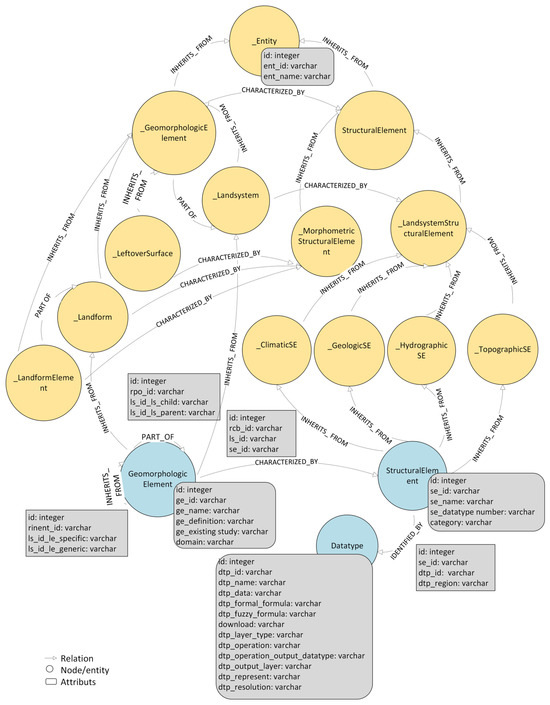

Our logical model transforms the conceptual model and the ontologies (presented in Section 3) into data structures that are compatible with the functionalities of a Neo4j graph database. This corresponds to the content of the Neo4j Graph Database (see Figure 5). We chose to distinguish three levels of nodes in our Neo4j graph (Figure 8). The first two levels correspond to the logical level. The third level corresponds to the data level where the instances are stored. In the following paragraphs, a detailed description of these levels is given.

Figure 8.

Logical model of data level of nodes.

The yellow nodes in Figure 8 display the first set of nodes and edges corresponding to the concepts and relations of our conceptual model (Figure 1). They represent the generic knowledge involved when modeling and manipulating landsystems and landforms. The second level is also displayed in Figure 8: the blue nodes and edges correspond to the domain ontology that defines the expert’s knowledge. The nodes of the second level are the geomorphologic elements and the structural elements from the domain ontology that form two taxonomies whose roots are the nodes of Level 1 in Figure 8. Nodes from one taxonomy are connected to nodes of the other taxonomy by characterization relationships in the conceptual model, which correspond to the characterized-by edge between the GeomorphologicElement and StructuralElement nodes in Figure 8.

As previously mentioned, geomorphologic elements and structural elements are located in one or several areas (Figure 1). In the conceptual model, an area corresponds to one surface or a set of surfaces of the geographic space representing an instance of geomorphologic element or an instance of structural element. The geographic information of an area can be obtained from a Geographic Information System (GIS). However, an area can be represented in different ways (for example, by a vector polygon or by a raster) since GIS data may have different formats. Consequently, we added a Datatype node in the graph data structure (Figure 8) to enable the connection between different data formats. A Datatype node stores the information about the data format and how to identify the areas using this data format.

The third level of nodes and edges contains instances of geomorphologic elements and instances of structural elements. These instances can be located in one or several areas in the geographic space. An object or element that represents a specific location or area in a model is called a spatial entity [29]. The area, or spatial characteristics of spatial entities, is defined by the geometry of spatial data in a GIS. As mentioned in Section 4, Neo4j offers no direct access to geometry. Instead, it is accessed using the R-tree through the Layer node. Thus, the areas of our conceptual model are not defined by nodes, but rather by spatial layers and the geometry of a structural element is obtained (computed) through the datatype node. Hence, we chose to connect a Datatype node to a Structural element node and to a Layer node, knowing that a Layer node is a representative of a Neo4j spatial layer. The edge between the Datatype and the StructuralElement nodes contains the properties used to extract the areas from the GIS data and to transfer it in the layer. For example, if the data file is a polygon shapefile, a property can indicate which parts of the polygons are structural elements. This representation allows for a structural element to be associated with different data files. A data file can be associated with several structural elements as well. Thus, instances of a structural element are located by defined geometries of the collection of spatial entities related to the Layer node. Such geometries are identified by Neo4j from the above-mentioned properties (structural element–datatype) through the R-tree index.

6. Landsystem Determination Using the Graph Database

Instances of geomorphologic elements are not initially stored in the data level. Considering that usually users are only interested in a subset of landsystems that are relevant to their study, it is unnecessary and computationally too expensive to compute and store the instances related to all possible landsystems in our Neo4j database. Rather, our system generates the landsystem instances on request from the user. These instances are not obtained directly from the data but rather inferred from the nodes of the second level (Figure 8), considering the type of landsystem of interest to the user. Indeed, a landsystem either inherits the characteristics of its parent landsystems or is directly characterized by a structural element. In the latter case, an instance of landsystems is located where an instance of a structural element is observed in the geographic space. In the former case, the landsystem is located in the area where all its parent landsystems are present. Thus, the landsystem area is obtained by intersecting the areas of its parent landsystems.

The process of instantiation is performed systematically in three steps. First, a query retrieves in the second level all the nodes of the structural elements that characterize the requested landsystem. This query is performed by going upwards through the landsystem hierarchy. Second, instances of all these structural elements are inferred from the related datatypes (Figure 8). For example, in Figure 9, the glaciation structural element (node 17) is connected to a shapefile datatype (node 21): an instance of a glaciation structural element can be inferred from such a shapefile datatype. Third, for each datatype, a layer is linked to the datatype. The resulting nodes and edges are added to the graph, enhancing the data level.

Figure 9.

Graph database instance related to mountainous glacial valley landsystem.

As an example, Figure 9 displays a portion of such a graph database which contains instances related to the mountainous glacial valley landsystem (MGVLS). As previously said, the graph database fits with the structure defined in the logical model (Figure 8) as follows:

(1) There are several kinds of nodes. Generic nodes related to high level concepts (yellow nodes in Figure 9), GeomorphologicElement/landsystem nodes (brown nodes in Figure 9), StructuralElement nodes (blue nodes in Figure 9), datatype nodes (green nodes in Figure 9) and Layer nodes (gray nodes in Figure 9).

(2) There are different types of edges: inheritance relationships between hierarchical landsystems, partition relationships between aggregated landsystems, characterization relationships between landsystems and structural elements, identification relationships between structural elements and datatypes as well as location relationships between layer and datatypes or landsystems.

We already mentioned that a landsystem inherits the characteristics of its parent landsystems or is directly characterized by a structural element. Hence, the system searches through the graph of instances to find the instances of structural elements. The type of operation to be performed to extract a structural element from data stored in a layer is defined in the properties of the edge connecting the datatype node and the structural element. For example, a property in the association edge between the Landmass Shapefile datatype (node 20) and the Terrestrial topography structural element (node 16) is ‘inside polygon’. Thus, multipolygon in the Terrestrial shapefile in the Terrestrial Topography layer (in node 24) defines the instances of Terrestrial Topography structural element (node 16) within the study area. This structural element characterizes the Terrestrial landsystem (node 9) in the study area. Similarly, multipolygon in the glaciation shapefile (in node 25) defines the instances of the Glaciation structural element (node 17) within the study area. This structural element characterizes the Glaciation landsystem (node 10) in the study area. Glaciated terrestrial landsystem (node 11) inherits from Terrestrial landsystem (node 9) and Glacial landsystem (node 10). Thus, the area of Glacial terrestrial landsystem (node 11) is obtained by intersecting the spatial data of the Terrestrial topography layer (node 24) and of the Glaciation layer (node 25). The previously retrieved spatial data (related to Glacial terrestrial landsystem in node 11) is intersected with the spatial data in the layer of the next landsystem in the hierarchy of landsystems (Mountainous landsystem: node 12). The resulting intersection coincides with the areas of structural elements corresponding to the region of the next landsystem in the hierarchy of landsystems (Mountainous glacial landsystem in node 13).

Finally, the spatial data related to Mountainous glacial landsystem in node 13 is intersected with the spatial data of the Valley landsystem (node 14). If an intersection is empty, the process is stopped, and it is concluded that the landsystem does not appear in the study area. Once reaching the final landsystem, the result of all the consecutive intersections defines the location of the instance of landsystem that has been requested by the user: the Mountainous glacial valley landsystem (node 15), in our example.

Finally, the system creates a new layer (node 28) linked to the GeomorphologicElement that represents the landsystem that has been identified (node 15). The result of the consecutive above-explained operations is stored in an output node (node 28). Through the various steps described above and using the relevant knowledge and data, the system can therefore automatically identify a landsystem in a specified study area.

7. Results and Discussions

In this section, we demonstrate how the approach introduced in this paper applies in a practical case study. First, we present the implementation of the proposed automatic physiographic approach, detailing the various datasets integrated in the logical model as well as the methods used for their acquisition, if appropriate. The purpose of this case study is to extract glacial valleys by applying our physiographic approach to a dataset of structural elements. The system automatically determines the successive landsystems that help identify the mountainous glacial valley landsystems. The final result of the whole process provides a map of the areas where glacial valleys can be found.

7.1. Study Area

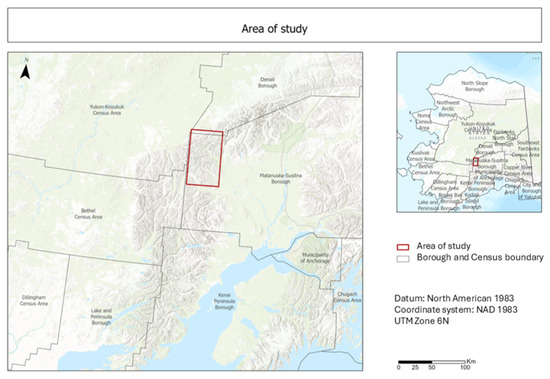

The chosen study area is located in the Alaska Range, as presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Localization of the study area.

The red polygon delimits the study area. The figure on the right illustrates the global location of the study area. Table 3 summarizes the spatial data that we use to locate each structural element (blue nodes in Figure 9) related to node 15 and the mountainous glacial valley landsystem (abbreviated as MGVLS in this section) that we are seeking in this experiment. These data are stored in the graph database in different layers (represented by the gray nodes in Figure 9).

Table 3.

Datatypes and sources related to the structural elements associated with the mountainous glacial valley landsystem.

7.2. Application of Our Approach and Tool

7.2.1. Data Sources and Data Operations

The MGVLS is characterized by the influence of glacial erosion along valleys within glacial mountainous regions. The glacial mountainous landscape is delineated successively by the three structural elements previously mentioned: Terrestrial topography SE, Mountainous topography SE and Glaciation SE. The characteristics that are typical of valleys are related to the Valley SE, which serves to identify valley landsystems embedded within the broader context of glacial mountainous landsystems.

For certain SEs, the instances can be imported from available datasets. In this study, this data importation is performed for the SEs Terrestrial topography (node 24 in Figure 9), Mountainous topography (node 26) and Glaciation (node 25 in Figure 9). The spatial datasets were selected considering several key criteria: open access availability, the required spatial resolution(s) and their fitness for use in this study.

We mentioned that a landsystem either inherits from the characteristics of its parent landsystems or is directly characterized by a structural element. As we saw in Section 6, the system navigates through the graph of instances (Figure 9) to retrieve the areas of higher landsystems of the MGVLS (nodes 8 to 14 in Figure 9) using the spatial data corresponding to the corresponding structural elements (Table 3).

Valley LS Computation

No available dataset identifies Valley SEs in the study area. Hence, in contrast to the direct importation of available data, we had to compute the areas corresponding to the Valley SE, using a Digital Elevation Model (abbreviated DEM in the second row of Table 3).

Let us recall that a valley SE can be defined as an Earth surface containing an elongated linear depression that typically contains a stream. The identification of the river network from a DEM can help find such elongated depressions. Moreover, a direct catchment is an area drained by a stream. Indeed, a direct catchment of a river is the portion of the catchment that drains directly into the river, without considering the flows drained from its tributaries [34]. Therefore, the determination of the river network and the associated direct catchment may help identify the valley SEs of the study area. Consequently, the first step applied to our case study is the delineation of the hydrographic network using a DEM.

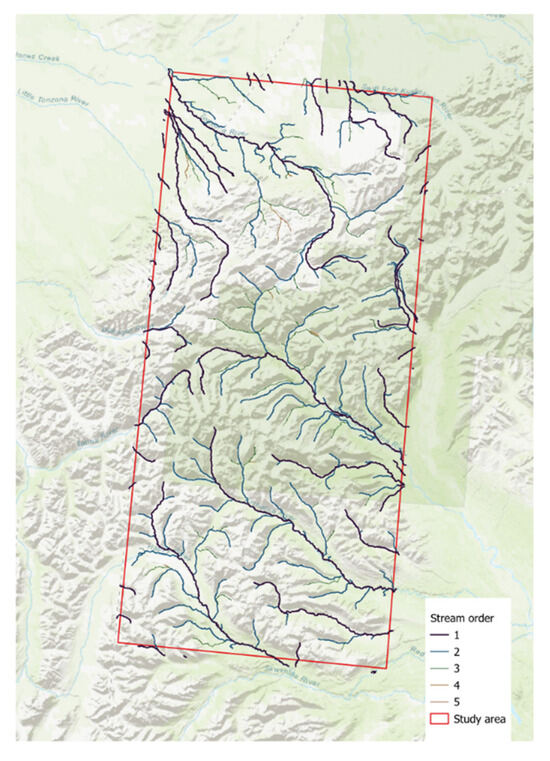

The hydrographic network is obtained by applying the Fill operation to the DEM to eliminate depressions, followed by the application of the D8 flow direction algorithm to determine the steepest descent for each cell [35]. Considering a flow accumulation threshold of 2 hectares, the algorithm identifies cells of the hydrographic network with sufficient flow accumulation. In this way the streams are delineated. There are different techniques to determine the order of streams and of their tributaries in a hydrographic network. For this project Hack’s stream ordering method has been chosen.

Hack’s order represents the hierarchical relationship between stream segments based on their discharge [36]. It is determined by assigning an order of 1 to the main channel, then incrementing the order by one for each tributary that discharges into a stream of a given order. Hence, all streams discharging in the mainstream are assigned an order of 2, and so on. For our study area, Figure 11 displays the hydrographic network ordered using Hack’s method with an order scale from 1 to 5.

Figure 11.

Hack’s stream ordering.

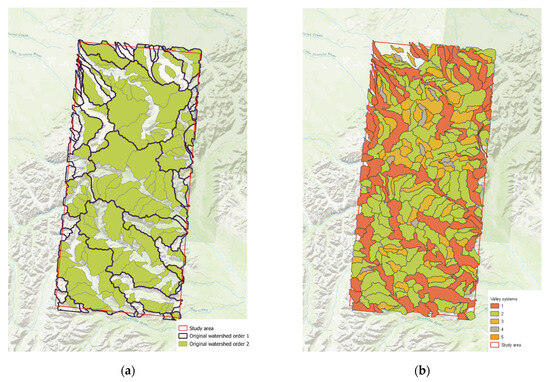

The second step of our method takes advantage of the spatial inclusion of watersheds associated with streams ordered using Hack’s method. Interestingly, using such an ordering, the watershed of an order-n stream includes all the watersheds of the order-n-1 streams. Consequently, if the areas of all the watersheds of the order-n-1 streams are removed from the area of the watershed of an order-n stream (spatial difference in areas), the remaining area includes the order-n stream as well as the area surrounding it (its direct catchment) that can be considered as its own portion of the valley. Therefore, we use this approach to determine the instance of the valley LS for each stream in the study area, considering its Hack’s order. As illustrated in Figure 4, Valley LS is identified through the Valley SE. Previously, we established that Valley SE is derived based on the direct catchment approach. Consequently, the areas delineated by the direct catchments correspond to the spatial instances of Valley LS.

Figure 12a illustrates the order-1 watersheds (black-bounded surfaces) and order-2 watersheds (green surfaces) that are initially computed. Figure 12b shows the partitioning of the study area into valley LS instances. Indeed, the order-1 watersheds represent the surface areas from which water flows toward the order-1 hydrographic network. Similarly, the order-2 watersheds correspond to the drainage area feeding into the order-2 network. To extract the instances of the Valley LS, as we saw, we apply the concept of direct catchment, which isolates the immediate contributing area to a given stream, excluding upstream contributions. Specifically, for the order-1 network (purple lines in Figure 11), the direct catchment (orange surface in Figure 12b) is computed as the spatial difference between the order-1 watershed (black-bounded surfaces in Figure 12a) and order-2 watershed (green surfaces in Figure 12a). This differential approach enables the identification of the direct catchment associated with each stream. This approach is applied iteratively across each order of the hydrographic network (Figure 11), allowing the delineation of the instance of the Valley LS (colored surfaces in Figure 12). Let us recall that a landsystem is a context of appearance of a landform and its association with other types of landforms. The instances of valley landystem which are previously identified define the regions in which it is likely to find valley landforms.

Figure 12.

(a) Order 1 watersheds (black-bounded surfaces) and order 2 watersheds (green surfaces)—(b) instances of the valley landsystem (colored surfaces).

7.2.2. Operation Process of the Proposed Physiographic Approach

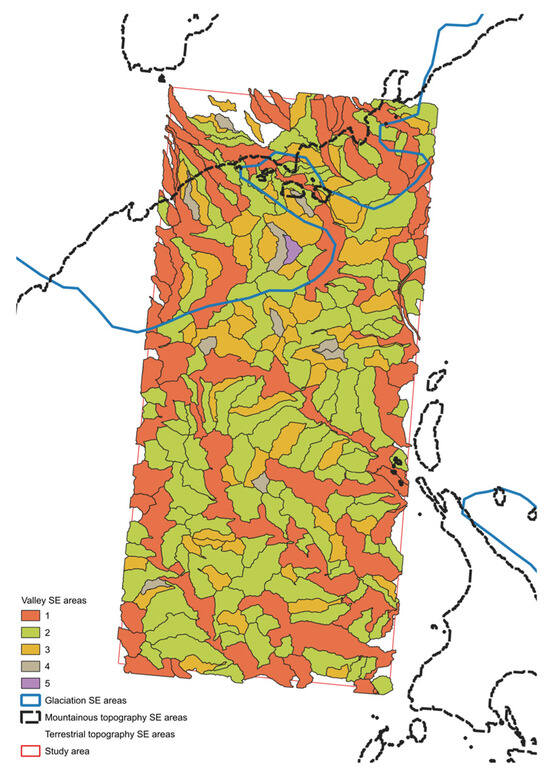

Now, let us see how the automatic determination of landsystems is carried out using the above-mentioned spatial data. Following the hierarchy of landsystems related to each structural element (nodes 8 to 15 in Figure 9), the system performs successive intersections between the areas of the structural elements in the study area, obtaining the areas characterizing the successive landsystems. Figure 13 represents the areas of the structural element related to the MGVLS. The system first computes the intersections between areas of the Terrestrial topography SE (white surfaces in Figure 13, node 16 in Figure 9) and the areas of the Glaciation SE (light blue-bounded surfaces in Figure 13, node 17 in Figure 9) to obtain the area of structural elements related to Glacial terrestrial landsystem (node 11 in Figure 9). The resulting areas are then intersected with the areas of the Mountainous topography SE (transparent surfaces with black dashed border in Figure 13, node 18 in Figure 9) to obtain the areas of the structural elements related to the Mountainous glacial terrestrial LS (node 13 in Figure 9). The resulting areas are then intersected with the areas of the Valley SE (colored surfaces in Figure 13) to obtain the areas of the structural elements related to the Mountainous glacial LS. Then, the resulting areas are intersected with the areas of the Valley SE (colored polygons in Figure 13, node 19 in Figure 9) to obtain the areas of the structural elements related to the Mountainous glacial valley landsystem (MGVLS). As a result of all these intersections, we obtain Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Areas of structural elements in the study area related to the mountainous glacial valley landsystem.

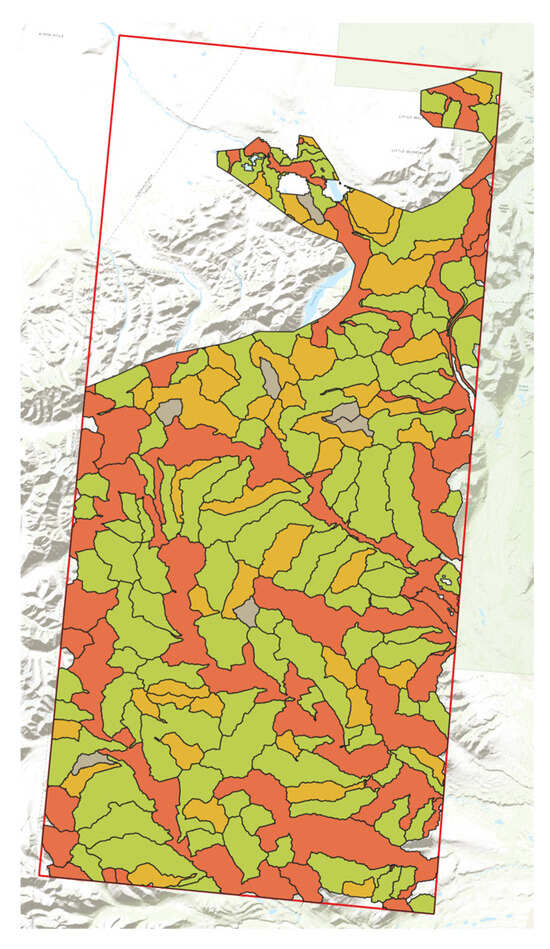

Figure 14.

Instances of MGVLS in the study area.

The colored surfaces represent the instances of MGVLS in the study area (Figure 14) according to the Hack order, as explained above. In this result, the landsystems were obtained by considering their context of appearance expressed by the structural elements of all the landsystems located above in the hierarchy. This context consideration and refinement involved the successive identification of relevant regions through the structural elements of parent landsystems. This approach mirrors the geomorphologist’s intuitive process of identifying landforms by considering the context defined by the successive landsystems. Moreover, the result illustrates the interdependent nature of valleys within the MGVLS. Second-order MGVLS instances (green surfaces) constitute the tributary of first-order MGVLS instances (represented by orange surfaces) and so forth for all MGVLS instances. This spatial partition structure demonstrates that MGVLS instances of order-n are tributaries of instances of order-n-1. Such a dynamic representation is invaluable for studying various phenomena entailing the MGVLS instances; for example, glacier flow patterns, ice melt tracking, sea-level rise or sediment transport.

The proposed physiographic approach enables the automation of the hierarchical identification method employed by geomorphologists. This approach is achieved using structural elements of the landsystems. The sequential steps within the proposed methodology allow for the generation of results that concretely reflect what geomorphologists can achieve through their expert knowledge.

7.3. Limits of the Proposed Approach

Geomorphologists aim at explaining the formation of landforms through the interaction of different processes; this is a complex endeavor, especially when considering the overall dynamics. Processes occurring on the Earth’s surface result in different types of landforms which, for example, interact with the geological characteristics of the underlying rock. In the case of glacial erosion, factors such as lithology and its physical properties play a crucial role. For instance, the strength of the bedrock and the degree of weathering significantly influence the rate of erosion that helps shape a valley profile. It should be noted that the analysis of these complex issues is beyond the scope of the present research.

Moreover, geomorphological elements are routinely identified by geomorphologists when observing visible characteristics on the Earth’s surface. These characteristics are the imprints left on land surfaces by the above-mentioned processes and their interactions. Our approach has been inspired by the observation and interpretation of these imprints carried out by the geomorphologist. This approach explains the introduction of structural elements in the proposed model and the fact that processes are not explicitly represented in this paper.

This paper is intentionally focused on landsystem modeling from a structural and conceptual standpoint. The proposed approach aims at formalizing expert geomorphological knowledge for the purpose of identifying and characterizing landsystems, rather than simulating or explaining the physical genesis of landforms or the processes involved in their formation.

Moreover, our approach does not attempt to address geotechnical, engineering or geological aspects, nor does it address the dynamic processes that shape landforms over time. Rather, it provides a framework for organizing and reasoning about landsystem structures based on observable and interpretable landforms modeled as structural elements.

One can also stress the importance of carefully choosing, with the help of expert geomorphologists, the definitions used to specify the structural elements to be input in our system. Choosing a different set of structural elements, or even different definitions, will indeed influence the final landsystem identification. It is recommended that each definition be validated using multiple peer-reviewed sources to minimize subjectivity and to ensure methodological rigor. The models derived from these definitions need also to be explained to expert geomorphologists and validated with their help. It is also recommended to inform geomorphologists—both the experts and the users of the proposed approach and tool—about the influence of the chosen definitions and the way they are translated into model elements (through the ontologies and the functions defined using Neo4j). We do not consider these knowledge engineering activities as a limit of the proposed approach, but rather as a good practice when using a well-founded cognitive approach and system, based on semantics and expert knowledge.

8. Conclusions

Landform classification presents a difficult task due to the inherent complexity of the Earth’s surface. With the increasing availability of geospatial data, the use of automatic and semi-automatic methods has become essential for identifying landforms. Among these, morphometric approaches, Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) and deep learning techniques are prominent. Automatic landform identification methods are typically designed for a specific landform and a particular study area, limiting their generalizability across diverse landscapes. These approaches often rely on parameter settings—such as threshold values or classification criteria—that are not universally defined and may vary depending on the characteristics of the dataset. As a result, the subjectivity inherent in parameter selection can significantly influence the results, impacting reproducibility and consistency in such landform analyses.

Observing geomorphologists’ practice, it appeared that they typically identify landforms by associating them with the natural processes that have shaped the Earth’s surface over geological time. This observation underpins the physiographic approach frequently used by geomorphologists in quantitative surface analysis. Indeed, structural elements are the result of geomorphological processes. These processes give rise to geosystems, which provide the context in which landforms appear. Inspired by the methodology employed by geomorphologists, we proposed a cognitive approach to landsystem identification that integrates the contextual factors typically considered in geomorphological analyses.

Building upon this holistic physiographic understanding, this paper presents a knowledge-based approach for landsystem identification, implemented in a Neo4j graph database.

The major contributions of the paper are as follows:

- A method to support geomorphologists in identifying relevant landsystems and structural elements to model the geomorphological context as part of their study of landforms.

- A conceptual model that formally captures geomorphological knowledge related to the physiographic approach. Such a model defines key concepts and their relations, with a particular focus on landsystems.

- A methodological approach that supports geomorphologists in the identification of landsystems. By introducing a dedicated identification approach and tool, this method enhances the ability to process large datasets and to conduct analyses over broader geographic extents, thereby improving the scalability and precision of landsystem identification.

- A software architecture specifically designed to implement this approach. The tool automates the identification of landsystems in accordance with geomorphological practices, facilitating the integration of expert knowledge in the computational workflows.

Our approach adopts a geomorphologist’s holistic perspective, focusing on the hierarchical structure of landsystems and their relationships to physiographic elements shaping the Earth’s surface. The case study demonstrated that applying a holistic perspective can be used to effectively incorporate structural elements into geomorphological analysis. The proposed approach relies on a limited number of parameters, all of which are generic and directly defined by domain experts. In this way, the results are easily interpretable and explainable.

The use of a graph database provides significant advantages in terms of flexibility and of computational power. While conventional graph-based approaches primarily rely on querying existing relationships within the database, our method goes further by enabling the inference of new spatial instances through the analysis of the graph structure and semantic connections. This inference mechanism leverages domain-specific rules based on the geomorphologist knowledge to uncover new knowledge that is not previously stored in the database. These newly inferred insights can be incorporated in the existing knowledge base, thereby enriching geomorphological understanding and supporting more nuanced interpretations. In future developments, the system can be extended to incorporate user profiles, allowing for adaptive reasoning based on the user’s expertise, preferences and/or research objectives. This personalization would enable the tool to prioritize certain types of knowledge or inference paths, tailoring the output to the user’s context.

Currently, structural elements are defined by GIS specialists beforehand, which ensures precision but limits scalability and the autonomy of geomorphologists. A promising direction is to integrate in the system a component for the automatic extraction of these structural elements from geospatial datasets, such as digital elevation models (DEMs). This approach would facilitate large-scale deployment and reduce the dependency on manual input, while maintaining the integrity of the inferred knowledge.

Another direction worth considering is to investigate how OBIA techniques could take advantage of our approach that models the geomorphological context using landsystems and structural elements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R., E.G., B.M. and P.L.; methodology, H.R., E.G. and B.M.; software, H.R.; validation, H.R., E.G., B.M. and P.L.; formal analysis, H.R.; investigation, H.R.; resources, E.G.; data curation, H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.; writing—review and editing, H.R., E.G., B.M. and P.L.; visualization, H.R.; supervision, E.G., B.M. and P.L.; project administration, E.G.; funding acquisition, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, grant number 2022-03885.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Open access data; details on Table 3 of the present paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OBIA | Object-Based Image Analysis |

| MGVLS | Mountainous Glacial Valley Landsystem |

| LS | Landsystem |

| SE | Structural Element |

| LF | Landform |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

References

- Schoeneberger, P.J.; Wysocki, D.A. Geomorphic Description System, Version 5.0; Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Soil Survey Center: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2017.

- Evans, I.S. Geomorphometry and Landform Mapping: What Is a Landform? Geomorphology 2012, 137, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, R.J.; Evans, I.S.; Hengl, T. Chapter 1 Geomorphometry: A Brief Guide. In Developments in Soil Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 3–30. ISBN 978-0-12-374345-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cassol, W.N.; Daniel, S.; Guilbert, É. A Segmentation Approach to Identify Underwater Dunes from Digital Bathymetric Models. Geosciences 2021, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Mayer, L. An Automatic Procedure for the Quantitative Characterization of Submarine Bedforms. Geosciences 2018, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Oleire-Oltmanns, S.; Eisank, C.; Drǎguţ, L.; Schrott, L.; Marzolff, I.; Blaschke, T. Object-Based Landform Mapping at Multiple Scales from Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and Aerial Photographs. In Proceedings of the 4th GEOBIA, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7–9 May 2012; pp. 496–500. [Google Scholar]

- Eisank, C.; Dragut, L. A Generic Procedure for Semantics-Oriented Landform Classification Using Object-Based Image Analysis. Geomorphometry 2011, 2011, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, R.A.; Shary, P.A. Chapter 9 Landforms and Landform Elements in Geomorphometry. In Developments in Soil Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 227–254. ISBN 978-0-12-374345-9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Xiong, L.; Tang, G.; Strobl, J. Deep Learning-Based Approach for Landform Classification from Integrated Data Sources of Digital Elevation Model and Imagery. Geomorphology 2020, 354, 107045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berral, J.L.; Gavalda, R.; Torres, J. Power-Aware Multi-Data Center Management Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2013 42nd International Conference on Parallel Processing, Lyon, France, 1–4 October 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 858–867. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Arundel, S.T.; Li, W.; Wang, S. GeoNat v1.0: A Dataset for Natural Feature Mapping with Artificial Intelligence and Supervised Learning. Trans. GIS 2020, 24, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvor, D.; Belgiu, M.; Falomir, Z.; Mougenot, I.; Durieux, L. Ontologies to Interpret Remote Sensing Images: Why Do We Need Them? GISci. Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 911–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumann, R.K.; Purves, R.S. Computation and Elicitation of Valleyness. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2011, 11, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, G. Les structures naturelles de l’espace géographique. L’exemple des Montagnes Cantabriques centrales (nord-ouest de l’Espagne). Rev. Géographique Pyrén. Sud-Ouest 1972, 43, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.U.; Doornkamp, J.C.; Doornkamp, J.C. Geomorphology in Environmental Management: A New Introduction, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-19-874151-0. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Duque, J.F.; Godfrey, A.E.; Pedraza, J.; Díez, A.; Sanz, M.A.; Carrasco, R.M.; Bodoque, J.M. Landform Classification for Land Use Planning in Developed Areas: An Example in Segovia Province (Central Spain). Environ. Manag. 2003, 32, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochava, V.B. Introduction to the Theory of Geosystems; Science: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, J.M. The Legacy of Sochava: The Theory of Geosystems; Federal University of Ceará: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kokla, M.; Guilbert, E. A Review of Geospatial Semantic Information Modeling and Elicitation Approaches. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, G.; Fryirs, K.; Reid, H.; Williams, R. The Dark Art of Interpretation in Geomorphology. Geomorphology 2021, 390, 107870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, R.; Barbosa, S.; Kurths, J.; Marwan, N. Understanding the Earth as a Complex System—Recent Advances in Data Analysis and Modelling in Earth Sciences. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2009, 174, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, R. The Need for Field Evidence in Modelling Landform Evolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, R.A.; Jones, R.K.; McNabb, D.H. Defining a Hierarchy of Spatial Entities for Environmental Analysis and Modeling Using Digital Elevation Models (DEMs). Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2004, 28, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstappen, H.T. Old and New Trends in Geomorphological and Landform Mapping. In Developments in Earth Surface Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 15, pp. 13–38. ISBN 978-0-444-53446-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huggett, R.J. Fundamentals of Geomorphology, 3rd ed.; Routledge fundamentals of physical geography series; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-203-86008-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Fernández, L.; Vallecillo-Moreno, A. An Introduction to UML Profiles. UML Model Eng. 2004, 2, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Guia, J.; Gonçalves Soares, V.; Bernardino, J. Graph Databases: Neo4j Analysis. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Porto, Portugal, 26–29 April 2017; SCITEPRESS-Science and Technology Publications: Porto, Portugal, 2017; pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, A. R-Trees: A Dynamic Index Structure for Spatial Searching. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 1984, 14, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, F.; Sheeren, D.; Becu, N.; Gaudou, B.; Lang, C.; Marilleau, N.; Monteil, C. 2-Description Formalisms in Agent Models. In Agent-Based Spatial Simulation with Netlogo; Banos, A., Lang, C., Marilleau, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 29–73. ISBN 978-1-78548-055-3. [Google Scholar]

- Coastlines. Available online: https://osmdata.openstreetmap.de/data/coastlines.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sayre, R. Global Mountains K3. Available online: https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/638fbf72d34ed907bf7d3080 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Last Glacial Maximum. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=046cde34ce804141a8d5303656e74f44 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- USGS National Hydrography Dataset Best Resolution (NHD). Available online: https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/61f8b882d34e622189c32886 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Smith, D.R. Assessment of In-Stream Phosphorus Dynamics in Agricultural Drainage Ditches. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3883–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, J.F.; Mark, D.M. The Extraction of Drainage Networks from Digital Elevation Data. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1984, 28, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]