Abstract

The widespread adoption of electric vehicles intensifies the spatiotemporal mismatch between charging demand and station capacity, leading to operational inefficiencies. This paper proposes a cooperative charging scheduling strategy based on a novel queuing model that integrates virtual charging piles and state variables to accurately estimate queuing time, overcoming the limitations of conventional methods. A bi-level optimization model is established to coordinate grid load balancing and station-level queue management. An adaptive large-neighborhood search algorithm combining heuristic rules with mathematical solving is developed for efficient solution. Numerical experiments demonstrate that the proposed strategy outperforms existing approaches by significantly increasing fulfilled charging demand and reducing queuing times with only minimal travel distance increase. Analysis further reveals a computational performance trade-off related to scheduling frequency, providing critical insights for practical implementation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The global transition towards sustainable transportation has positioned EVs as a cornerstone of future mobility systems [1]. With their zero tailpipe emissions, EVs are hailed as a pivotal solution to urban environmental challenges [2]. However, the uncoordinated charging of a rapidly growing EV fleet poses significant adverse effects on the operational stability of local power distribution networks [3]. Consequently, managing the EV charging process is essential to reduce grid congestion and balance load [4].

The scale of this challenge is monumental, a trend powerfully exemplified by the market dynamics in China. By the end of 2024, China’s pure EV stock had reached 22.09 million. To support this massive fleet, the country witnessed an explosive growth in public charging infrastructure, adding 4.222 million new charging points in 2024 alone, a 24.7% year-on-year increase, bringing the total to 12.818 million. This phenomenon of “parallel growth of vehicles and charging points” represents a common challenge faced by many regions. However, the rapid expansion often masks underlying operational inefficiencies. The development of public charging facilities is highly uneven, leading to a significant “spatiotemporal mismatch” between charging demand and supply. Some stations are chronically under-utilized while others suffer from severe congestion, and the large-scale, unscheduled charging of EVs continues to exacerbate fluctuations in local grid load [5]. This indicates that merely deploying more charging infrastructure fails to address the core challenges of supply–demand imbalance, low station utilization, and increased grid stress.

Smart and orderly charging emerges as a critical solution. Unlike uncoordinated charging, orderly charging intelligently controls the charging power of in-station EVs across different time periods. The primary objective is to shift charging loads while ensuring that both individual charging demands and the total power capacity constraints of the station are met. By optimally distributing the charging load over time, this approach can significantly flatten the load profile, mitigate fluctuations, and enhance the overall stability of the local power network.

However, implementing effective orderly charging in practice faces significant hurdles. The uncertain and diverse nature of EV users’ charging demands increases both the time and financial costs for users. This presents a shared challenge for both users and operators. On one hand, EV users seek high-quality, convenient charging services with minimal detours, cost, and queue times. On the other hand, charging station operators must improve service quality to meet diverse user needs and enhance facility utilization to avoid losses from long queues. Moreover, as critical load nodes, charging stations must operate within strict power capacity constraints imposed by the local grid infrastructure while executing charging schedules.

1.2. Literature Review

The existing body of research on EV charging coordination can be broadly categorized into several streams, primarily focusing on power management-based orderly charging and queue-aware scheduling strategies.

A significant line of research addresses the challenge of grid stress by shifting charging loads from peak to off-peak hours using time-of-use (TOU) pricing. Studies have developed scheduling models that leverage knowledge of EV arrival, departure, and energy demand to flatten the load profile and maximize charged energy [6,7] or to adjust charging start times and power levels across different periods [8]. Beyond simple time-shifting, other scholars have enhanced charging flexibility through coordinated power control across different time slots, analyzing its impact on charging fairness and grid load [9,10]. Research has also focused on minimizing charging costs under time-varying electricity prices [11] and designing pricing mechanisms that incentivize users to delay their charging completion times [12].

Further extending these economic strategies, substantial research has been conducted from user and operator perspectives. From the user’s standpoint, studies have developed reservation-based mechanisms considering the heterogeneity of user information to select optimal charging stations [13], and proposed scheduling strategies that account for charging urgency [14]. To enhance user participation, various reservation mechanisms have been explored, including models based on EV willingness [15], mechanisms integrating travel and charging time windows [16], and intelligent scheduling for mobile chargers [17]. Other approaches include Markov chain modeling for reservation forecasting [18], dynamic pricing schemes [19].

Conversely, from the operator’s perspective, studies have developed models to minimize electricity procurement costs by scheduling both reserved and walk-in users under real-time pricing [20,21]. Other work has aimed to minimize waiting times while maximizing fully charged durations in vehicle-to-vehicle contexts [22]. Research has also focused on maximizing revenue through optimized pricing and reservation fees [23], or computing schedules that maximize social welfare [24].

While power management is crucial, another critical research stream acknowledges that station queueing conditions are a decisive factor influencing user behavior. Effectively leveraging queue information is thus a potent means to induce user compliance with scheduling schemes. Several studies have integrated waiting time considerations into their models, utilizing information sharing to estimate future waiting times [25] or balancing time-aware fairness with overall waiting time [26]. Recent research has also explored charging guidance strategies from multiple perspectives. From the user viewpoint, studies have developed station ranking systems [27], while others have inferred user preferences through tensor factorization [28]. Approaches have introduced user satisfaction indices in bi-level optimization models [29], and employed chaotic optimization to reduce charging time and travel distance [30].

The integration of traffic congestion factors represents another important direction. Studies have combined real-time traffic and grid conditions to minimize comprehensive user costs, demonstrating the potential to alleviate both traffic and grid congestion [31]. Other work has incorporated time-varying traffic conditions into station recommendations based on vehicle counts [32]. Additional approaches include designing systems to minimize response time under stochastic demand [31], and developing strategies considering distribution network constraints [32] and range anxiety [33].

The modeling of these complex problems often employs sophisticated mathematical frameworks like Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) [34] and hierarchical hybrid optimization [35]. The bi-level modeling framework is particularly suited for this context, naturally decomposing the problem into upper-level vehicle-to-station assignments and lower-level in-station scheduling [24,36]. To accurately represent queueing, methods such as Markov state-switching processes [37] and charging conflict matrices [38] have been introduced. To solve these complex models, various algorithms have been proposed, including learning-based methods [39], approximate dynamic programming [40], and metaheuristics [25].

1.3. Contributions and Organization

A critical synthesis of the prior work reveals the following persistent gaps at the intersection of power management and queueing dynamics that this study aims to bridge:

- Inaccurate Queueing Modeling: Traditional queueing theory often fails to precisely calculate waiting times from the station’s perspective under dynamic charging states and power constraints. A more granular model that captures the real-time state of the charging queue is needed for realistic user satisfaction evaluation.

- Uncoordinated Objectives: A significant limitation is the frequent disconnect between the objectives of minimizing grid load fluctuations and minimizing user queue times. An integrated framework that simultaneously addresses both operational and user-centric goals is lacking.

- Computational Inefficiency for Integrated Models: The integration of detailed queueing models with multi-stage, power-constrained scheduling leads to complex problems. There remains a need for efficient solution methods that can handle this integrated complexity for practical-scale problems.

In contrast to the prior work, this research proposes a comprehensive multi-stage orderly charging scheduling framework under power capacity constraints. The main contributions of this thesis are threefold:

- We introduce a novel queuing model with virtual charging piles and state variables to accurately calculate EV waiting times, addressing the first gap.

- We formulate a bi-level optimization model that explicitly co-optimizes the goal of flattening the station’s load profile with the objective of minimizing user queue times, thereby bridging the second gap.

- We develop an adaptive large-neighborhood search (ALNS) algorithm, which hybridizes heuristics with a mathematical solver, to solve the resulting complex model efficiently, which addresses the third gap.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed elaboration of the research problem, the vehicle charging scheduling process, and the novel queuing modeling approach. Section 3 comprehensively introduces the bi-level optimization model for orderly EV charging scheduling. Section 4 presents the improved adaptive large neighborhood search algorithm developed to solve the proposed model efficiently. Section 5 details the numerical experiments, including case studies and comparative analyses, conducted to validate the effectiveness of both the model and the algorithm. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the principal findings, discussing the associated managerial insights, and outlining potential avenues for future research. Section 7 summarizes the full study.

2. Problem Formulation for EV Charging Scheduling

2.1. Problem Description

This study considers a smart charging coordination system operating within an urban transportation network, denoted as G. Multiple charging stations, managed by a single operator, are distributed across this network. EV users in need of charging submit requests to a central reservation platform. Each request comprises a set of information, including the user’s current location, origin-destination (OD) trip details, and the desired amount of charge. Upon receiving a request, the reservation platform evaluates the real-time status of all charging stations, including the availability of idle charging piles and the existing queue conditions. The platform first assesses whether the station nearest to the user can fulfill the charging demand. If the nearest station suffers from a shortage of available chargers or is experiencing a queue, the platform will assign the user to an alternative station. To incentivize user acceptance of this potentially less convenient assignment, a certain scheduling compensation is offered. If the user accepts the assigned station, their charging information is formally allocated to that specific station. Subsequently, the assigned charging station, operating under a total power capacity constraint imposed by the local grid, is responsible for developing a detailed charging schedule for all EVs on its premises. This involves determining the optimal allocation of charging power across different time periods for each vehicle, a process defined as multi-stage orderly charging.

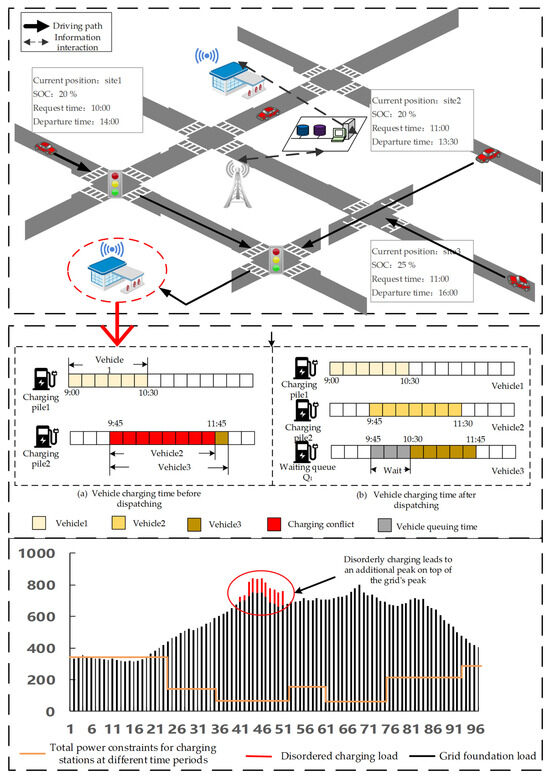

As shown in Figure 1, the core decisions in this coordinated scheduling process are twofold and operate at different levels: At the upper level, the reservation platform must decide on the optimal assignment of each EV user to a specific charging station. At the lower level, each individual charging station must decide on the optimal allocation of charging power across different time slots for every EV assigned to it, while strictly adhering to the station’s total power limit. The overarching objective of this bi-level decision-making framework is to achieve a system-wide optimum that balances the minimization of user costs, the maximization of station operational efficiency, and the flattening of the aggregate power load on the grid. The structure of this problem naturally lends itself to a bi-level programming model, which will be formally defined in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the orderly charging scheduling problem for EVs.

2.2. Charging Scheduling Process and Detour Compensation

Due to the limited availability of charging resources at individual stations, it may not be possible to fulfill all incoming user reservation requests at the initially preferred location. In such cases, the system recommends that users proceed to another station within the same corporate network for service.

EV users typically base their routing and charging station choices on minimizing total travel cost. However, users have diverse travel plans and charging requirements, and may not automatically comply with the system’s proposed scheduling. To encourage acceptance, the charging operator provides a compensation to users who are assigned to a non-nearest station. This compensation is proportional to the additional distance traveled, or detour. If the user does not accept the scheduling proposal, the reservation request is canceled, and the user must independently find an alternative station, potentially joining a physical queue.

The rerouting caused by following the system’s assignment can increase the user’s travel cost. This detour cost is quantified by comparing two shortest-path distances within the road network:

- The shortest path from the user’s origin to destination that includes any suitable charging station.

- The shortest path from the origin to destination that includes the specifically assigned charging station.

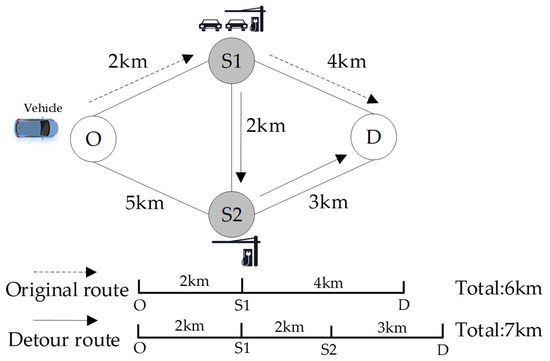

Illustrative Example: To clearly illustrate the detour cost calculation central to our compensation mechanism, we refer to the simplified road network depicted in Figure 2. The network consists of four key nodes: the origin (Node O), two charging stations (Nodes S1 and S2), and the destination (Node D), interconnected by five links with distances annotated.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the detour cost calculation.

Consider an EV user traveling from Origin O to Destination D who requires charging route. The user’s original, shortest path, which includes the charging station S1, is O → S1 → D, with a total travel distance of 2 km + 4 km = 6 km. Now, suppose the charging station S1 is congested, and the system operator schedules the user to charge at station S2 instead to balance the load. The user’s new assigned path becomes O → S1 → S2 → D. The total travel distance for this scheduled path is 2 km + 2 km + 3 km = 7 km. The detour distance is therefore calculated as the difference between the scheduled path and the original path, which is 7 km − 6 km = 1 km.

This calculated detour distance of 1 unit forms the objective basis for the financial compensation offered to the user. This compensation mechanism is pivotal for our model, as it aligns individual user incentives with the system-level objective of optimal station utilization and grid load balancing. By internalizing the congestion externality making the system operator directly account for the inconvenience of detours in its scheduling decisions, it encourages user acceptance of system-optimal routing and enhances the overall efficiency of the charging network.

To mathematically formulate the compensation mechanism, we define the following notation. Let denote the minimum travel cost for EV user from their origin to destination, which inherently includes a stop at least one suitable charging station along the optimal path. This value A represents the user’s baseline travel cost under an ideal, unconstrained scenario.

When the scheduling platform assigns user to a specific charging station , it results in a new travel route. Let be the minimum travel cost for user from their origin to destination, including a stop at the specifically assigned charging station . The detour cost, denoted as , incurred by user due to this assignment to station is then defined as the difference between the cost of the assigned route and their original optimal baseline cost.

This value quantifies the additional travel burden, in terms of cost, placed upon the user. To incentivize the user to accept this sub-optimal routing and internalize this negative externality, the operator provides a monetary compensation. The compensation offered to user for accepting an assignment to station is calculated as a linear function of the incurred detour cost:

Here, is a predefined value coefficient, representing the monetary value per unit of detour cost. This coefficient is a critical policy parameter that balances the operator’s compensation costs against the achieved improvement in system-wide efficiency through successful load redistribution.

To ensure transparency and facilitate informed user consent, the scheduling platform presents a comprehensive charging information alongside any reassignment proposal. This information includes the forecasted waiting time and energy price at the assigned station along with the calculated detour compensation. While a user’s acceptance decision could theoretically be modeled using a total cost baseline incorporating travel time and queue risk, our compensation mechanism is deliberately designed from a system operator’s perspective. It employs a fixed, distance-based coefficient (α) to ensure operational simplicity and, crucially, to uphold fairness by providing identical compensation to users incurring the same physical detour, thereby avoiding the practical challenges and potential inequities of estimating user-specific values of time and real-time traffic conditions.

2.3. Modeling Approach for EV Charging Queue Status

The number of EVs assigned to a station by the upper-level model may lead to charging congestion and queuing phenomena. Given that the charging time required for each EV varies significantly, using the average service time from classical queuing theory to estimate waiting times is often inaccurate. To precisely capture the queuing dynamics, we introduce a queue status variable to accurately record the waiting time of each EV.

To represent the queuing state of EVs at charging stations within the model, we propose the concept of a virtual charging pile to accommodate EVs in the queue. A variable is defined to indicate that EV user is waiting in period for a physical charging pile to complete its current charging task. Only when all physical charging piles at a station are occupied can additional EVs be assigned to virtual charging piles. While in a virtual pile, an EV’s charging power is zero, representing that the vehicle has arrived at the station but has not yet started charging. The number of virtual charging piles corresponds to the maximum queue length allowed at the station. For modeling simplicity, we constrain only the maximum occupancy of charging piles in any single time period, without explicitly modeling the detailed queue discipline for each physical pile. The transition of an EV from the queuing state to the charging state is represented by a conversion between a virtual charging pile and a physical one.

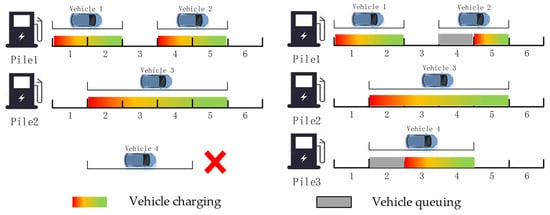

Consider a charging station with two physical charging piles and the arrival of four EVs, with their respective arrival and dwell times as shown in Figure 3. If queuing is not permitted, the station, aiming to maximize its own revenue, would choose to serve Vehicles 1 to 3, while Vehicle 4 would be denied service due to scheduling conflicts. However, if the station allows queuing, it can accommodate all four vehicles. The gray segments represent periods when vehicles are waiting to charge.

Figure 3.

A comparison diagram of charging station charging scheduling and queuing.

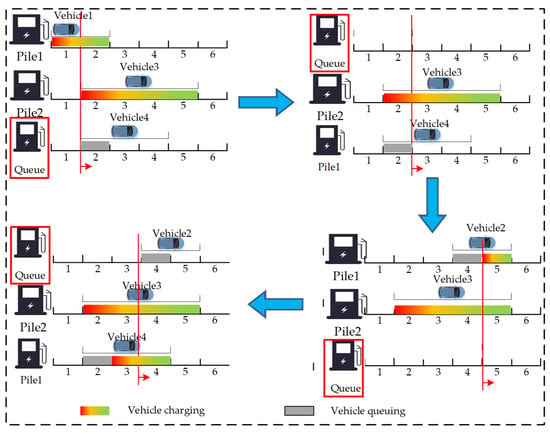

The conceptual framework for modeling this queuing process is illustrated in Figure 4. Here, the Charging Pile 3 is a virtual pile, the red lines and arrows in the figure indicate the current time period. In time period 2, when Vehicle 4 arrives at the station and all physical piles are occupied, it is assigned to the virtual pile (Pile 3) to wait, denoted by status variable . In time period 3, Vehicle 1 completes its charging and vacates physical Pile 1. At this point, Virtual Pile 3 effectively replaces the now-available Physical Pile 1. The physical charging resources are now Piles 2 and 3, while Pile 1 transitions to a virtual state, representing the waiting queue. In time period 4, Vehicle 2 arrives and is assigned to wait at the virtual pile (Pile 1), indicated by status variable . Finally, in time period 5, after Vehicle 4 departs, Vehicle 2 begins charging, and Pile 3 reverts to a virtual state, again representing the charging queue. This method is scalable and can be extended to model scenarios involving multiple queues and complex waiting times.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the queuing concept in station charging scheduling modeling.

3. Model Formulation

3.1. Model Assumptions and Notation

The mathematical model for the coordinated EV charging scheduling problem is formulated in this section. To provide a clear reference, we first present in Table 1 a structured nomenclature, where key notations are categorized into sets, parameters, and decision variables, which will be extensively referenced in the ensuing formulations.

Table 1.

Notation and descriptions in the EV orderly charging scheduling problem.

The problem of variable-power charging scheduling for EVs at stations requires consideration of both the operational decisions and power resource constraints of the charging station, as well as the travel plans and charging demands of EV users. To simplify the problem while maintaining the model’s generality, the proposed fundamental assumptions are as follows:

Assumption 1:

The charging station operating system is capable of implementing precise, time-slotted control over the output power of charging piles.

Assumption 2:

Key parameters of EV users, such as vehicle battery performance and driving speed, are assumed to be homogeneous.

Assumption 3:

The charging power at the station is variable, and the state of charge (SOC) of an EV increases linearly during the charging process.

Assumption 4:

The unit marginal revenue for electricity sold by the charging station during grid peak load hours is significantly lower than that during off-peak hours.

Assumption 5:

Queuing Discipline. The charging station operates under a non-preemptive, earliest-available-start-time queuing discipline.

Assumption 1 establishes the technical foundation for the charging scheduling of EVs at the station and is a common premise in research on time-slotted power dispatch. Assumption 2 simplifies the model parameters related to EVs; since the heterogeneity of different EV parameters does not fundamentally alter the nature of the model or the efficiency of its solution, a uniform setting is adopted. Assumption 3 facilitates the modeling of the charged energy per time slot in the model; in reality, the variation in charged energy over a fixed period at a constant charging power can be achieved by controlling the specific charging duration and energy transferred. Assumption 4, aligned with time-of-use pricing policies, ensures the economic incentive for the station to prioritize charging during periods of low grid load. Assumption 5 ensures EVs are served in the order of their arrival at the virtual queue. However, the actual charging start time for an EV is determined by the earliest time slot in which a physical charging pile becomes available and the station’s power capacity constraint is satisfied, following the departure of preceding vehicles.

3.2. Formalization of the Queuing Discipline and Causality

To rigorously address the operational logic of the proposed virtual charging pile concept, this subsection formalizes the queuing discipline and demonstrates how the model inherently maintains service causality.

The queue management operates under a non-preemptive, earliest-available-start-time discipline. Conceptually, EVs are admitted to the virtual queue in the order of their arrival. However, the precise moment an EV transitions from the queuing state to the charging state is determined by the optimization process, which seeks to maximize station revenue while respecting two fundamental sets of constraints: (1) the physical coupling constraints of charging piles and power capacity, and (2) the temporal state-tracking constraints for each vehicle.

Critically, the binary variables and do not represent a static, one-to-one mapping of vehicles to specific virtual or physical piles. Instead, they are global state indicators that track, for each time period , whether vehicle is in a queuing state or a charging state, respectively. The causality of service ensuring that no vehicle can begin charging before earlier-arriving ones that are still queuing is implicitly enforced by the combination of the objective function and the system constraints.

Specifically, the continuity of a vehicle’s queuing state, enforced by constraints of the form over the relevant time horizon, ensures that its “place” in the virtual queue is logically maintained. The optimization solver, when simultaneously scheduling all vehicles, cannot violate this continuity without also violating the station’s capacity constraints (Equations (19) and (20)) or producing a suboptimal solution. For instance, scheduling a later-arriving vehicle to charge before an earlier-arriving one would force the earlier vehicle’s queuing state variable to illogically change from 1 to 0 and back to 1, which is prohibited by the state continuity constraints. Therefore, the model structure itself naturally prevents overtaking and upholds a fair service order aligned with the stated discipline, as any solution violating this principle would be deemed infeasible or non-optimal by the solver.

3.3. Optimization Model

3.3.1. Upper-Level Model

After EV users transmit their charging information to the charging station scheduling platform, the platform proceeds to assign charging stations to the EVs based on this information. Subsequently, upon receiving the assigned charging tasks, each charging station aims to maximize its own revenue by devising a charging power allocation plan across different time periods. Given that the overall problem involves these two interconnected decision-making layers, a bi-level programming model is established. The upper-level model focuses on the charging station assignment scheme for EVs as its primary decision variable, formulating an optimization model with the objective of maximizing the total charging revenue of the system. The objective function is presented in Equation (2).

s.t.

Specifically, Equation (3) represents the total charging revenue of the stations. Equation (4) denotes the detour compensation cost incurred by the stations for directing EV users to their assigned charging stations; this cost is calculated as the difference between the travel cost of the route from the user’s origin to destination via the specifically assigned station and the travel cost of the shortest feasible route from the origin to destination that includes at least one charging station. Equation (5) expresses the time penalty cost imposed on EV users for queuing and waiting at the assigned station. Equation (6) enforces the driving range constraint for EV users traveling to the assigned charging station, ensuring the station is within reach. Equation (7) specifies the assignment constraint, guaranteeing that each EV user is assigned to one and only one charging station. Finally, Equation (8) defines the critical feedback relationship in the bi-level structure: variables and are the optimal solutions obtained from the lower-level model, given the specific values of the decision variables X determined by the current upper-level model.

3.3.2. Lower-Level Model

Based on the decision variables determined by the upper-level model, which assign EVs to specific charging stations, the lower-level model performs coordinated management of the charging power for each vehicle upon receiving their charging information, formulating a detailed charging schedule across different time periods. For an individual charging station s, the decision-making objective is to maximize its own charging revenue. Consequently, the objective function of the optimization model for the coordinated allocation of variable charging power at the station is presented in Equation (9).

s.t.

Specifically, Equation (10) imposes the maximum charging power constraint for each EV. Equation (11) ensures that each EV user arriving at the charging station is assigned to at most one charging pile. Equations (12)–(14) introduce auxiliary variables to resolve the nonlinearity caused by the multiplication of decision variables, while simultaneously enforcing the constraint that multiple vehicles assigned to the same physical charging pile must not have overlapping charging times. Equation (15) states that the charging power must be zero for any charging pile that does not have a vehicle present during a given time period. Equation (16) represents the station’s total power capacity constraint, which must be respected in every time period. Equation (17) guarantees that each EV user reaches their required state of charge before departing from the station. Equation (18) is a logical constraint specifying that the charging power must be zero during time periods when the EV user is not physically present at the station.

Equation (19) restricts the number of vehicles charging simultaneously at the station to no more than the total number of physical charging piles available. Equation (20) defines the maximum queue length constraint, limiting the number of vehicles that can be in a queuing state at any time. Equation (21) enforces the maximum allowable queuing time for any EV. Equation (22) is a logical constraint preventing an EV from entering the queue after it has already started charging. Equation (23) ensures that the start time of queuing for an EV falls between its arrival time and its departure time from the station. Equation (24) reinforces the logical condition that charging power must be zero when the EV is not at the station. Equation (25) is a logical constraint. Finally, Equation (26) implements the queue triggering logic: a newly arrived vehicle must enter the queuing state if and only if all physical charging piles at the station are occupied at the time of its arrival.

4. Solution Methodology

4.1. Model Analysis and Solution Framework

The bi-level optimization model formulated for the coordinated EV charging scheduling problem in this study is intrinsically NP-hard. For small-scale instances, exact methods can be employed to guarantee global optimality; however, as the number of EVs and charging stations increases, the computational complexity of such methods becomes prohibitive, leading to severe efficiency bottlenecks. Consequently, efficient meta-heuristic strategies emerge as a superior alternative for obtaining high-quality solutions within reasonable timeframes. Among them, the Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search algorithm has been extensively validated as a highly effective meta-heuristic through numerous empirical studies in related combinatorial optimization domains and is adopted here.

An analysis of the proposed bi-level model reveals its nested structure: the upper-level model, from the perspective of the charging scheduling platform, aims to maximize total charging revenue by planning the initial EV-to-station assignment scheme. The lower-level model, based on the assignment decided by the upper level, subsequently optimizes the detailed charging plan for each station with the objective of maximizing its own operational revenue, and then feeds the resulting performance metrics back to the upper model. The upper model subsequently refines the charging scheduling scheme based on this feedback. Since the feasible solution space of the lower-level model is constrained by the decision variables transferred from the upper level and varies in size, solving both levels simultaneously would lead to an explosion in the dimensionality of the decision variables, making it computationally intractable. To address this challenge, a hybrid method combining heuristic algorithms and exact solution techniques is adopted. The ALNS algorithm is utilized in the upper level to intelligently explore and adjust the scheduling scheme, while commercial solvers such as CPLEX or Gurobi are called to solve the lower-level integer programming model exactly for a given assignment, thereby ensuring solution quality while accelerating the overall solving speed.

This section systematically elaborates on the specific procedure of employing the ALNS algorithm to solve the EV charging scheduling model. The solution process initiates by generating a feasible initial solution using a greedy strategy. The algorithm then proceeds iteratively: in each iteration, a destruction phase employs adaptive removal operators to partially dismantle the current solution, followed by a repair phase that uses insertion operators to reconstruct a new candidate solution. This destroy-and-repair cycle, guided by an adaptive weight adjustment mechanism that rewards effective operators, enables dynamic exploration of the search space. The algorithm iterates until a predefined termination condition is met, finally outputting the best-found solution. The overall flowchart illustrating this multi-stage scheduling and algorithmic solution framework is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

EV charging scheduling process and solution step diagram.

4.2. Initial Solution Generation

This section employs a greedy algorithm to generate an initial solution for the EV charging scheduling problem. The process begins by comparing the total number of EV users to the total number of available charging piles across all stations. If the number of EV users is less than or equal to the total number of charging piles, the initial assignment aims to minimize the total detour cost. Each EV user is initially assigned to their geographically nearest charging station. The algorithm then iterates through all stations. If the number of EVs assigned to any station exceeds its number of physical charging piles, the excess EVs are reassigned to their next nearest available station. This step ensures that no charging station experiences queuing in the initial solution under this condition.

Conversely, if the number of EV users exceeds the total number of charging piles, a different strategy is applied. EV users are first sorted in ascending order based on their potential detour cost. Then, an attempt is made to distribute the EVs as evenly as possible among the stations, considering their respective numbers of charging piles, while respecting the sorted order. This approach aims to balance the initial load across stations and minimize overall detour costs, even though some queuing becomes inevitable due to the excess demand.

4.3. Removal Operators

To optimize the objective function of the upper-level model, five distinct removal operators are designed as follows:

- (1)

- Random Removal Operator

Randomly removes EV users from one charging station.

- (2)

- Longest Queue Removal Operator

Based on the results computed by the lower-level model, identifies the station with the longest total waiting time and randomly removes EV users from that station.

- (3)

- Maximum Conflict Removal Operator

Based on the results computed by the lower-level model, identifies the station with the largest cumulative stay-time conflict among EV users and randomly removes EV users from that station.

- (4)

- Maximum Detour Cost Removal Operator

Based on the results computed by the lower-level model, identifies the station where EV users incur the highest total detour cost and randomly removes EV users from that station.

- (5)

- Maximum Unserved Users Removal Operator

Due to conflicts in EV user stay times and limited charging pile resources, some stations may be unable to fulfill all charging requests. This operator identifies the station with the highest number of unfulfilled charging requests based on the lower-level results and randomly removes EV users from that station.

4.4. Insertion Operators

To support the upper-level objective function, three insertion operators are designed as follows:

- (1)

- Random Insertion Operator

Randomly inserts EV users into one charging station.

- (2)

- Shortest Queue Insertion Operator

Based on the results computed by the lower-level model, identifies the station with the shortest total waiting time and randomly inserts EV users into that station.

- (3)

- Minimum Conflict Insertion Operator

Based on the results computed by the lower-level model, identifies the station with the smallest cumulative stay-time conflict among EV users and randomly inserts EV users into that station.

4.5. Solution Feasibility Repair

To ensure solutions remain feasible after removal and insertion operations, each newly generated solution undergoes a feasibility check. If a solution is infeasible, the algorithm identifies the infeasible station, removes half of the currently assigned EV users from those stations, and applies a greedy reinsertion process. The feasibility check is repeated until a feasible solution is obtained. The quality of the new solution is then evaluated. If it improves upon the current solution, it is accepted.

4.6. Search Weight Adjustment

To enhance solution quality, the algorithm assigns adaptive weights to each operator. During each iteration, one removal operator and one insertion operator are selected using a roulette wheel selection mechanism based on their current weights. The selected operators are then applied to perform a neighborhood search.

If the new solution after the neighborhood search is better than the current solution but worse than the best-known solution, the weights of the employed removal and insertion operators are increased by .

If the new solution outperforms the best-known solution, the weights of the employed operators are increased by σ2 (where > ).

To prevent any single operator from dominating the search process and to maintain diversity, operator weights are periodically decayed based on the number of iterations.

Furthermore, recognizing that different combinations of removal and insertion operators may yield varying performances, the algorithm records the pairwise performance scores between removal operator and insertion operator after each neighborhood search. When a removal operator is selected, the weights of the insertion operators are adjusted based on these pairwise scores before performing the roulette wheel selection for the insertion operator.

4.7. Algorithm Solution Procedure

The detailed steps of the Improved Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search algorithm proposed for this model are as follows:

Step 1: Input the road network data, charging station information, EV user data, relevant parameter values, and algorithm termination conditions. Generate an initial EV charging scheduling scheme using the greedy algorithm.

Step 2: Compute and record the total cost of the current scheduling scheme, along with station-specific metrics such as queue lengths, vehicle conflicts, and the number of unserved EVs.

Step 3: Select one removal operator and one insertion operator based on their current weights and perform the removal and insertion operations.

Step 4: Check the feasibility of the newly generated solution. If it is infeasible, apply the feasibility repair procedure. If the solution is accepted, perform a local search to further refine it.

Step 5: Compare the new solution with the current and best-known solutions. Determine the operator performance scores and update the weights of the operators accordingly.

Step 6: Increment the iteration counter. Check if the termination conditions are meet. If terminated, output the optimal scheduling scheme and total cost; otherwise, return to Step 2.

Integrating the components described in the previous sections, the complete Improved Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Improved Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search | |

| Input: Network data, EV data, ALNS parameters. | |

| Output: Best scheduling scheme , | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | do |

| 6 | Select removal operator and insertion operator via roulette wheel |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | then |

| 11 | |

| 12 | end if |

| 13 | then |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | then |

| 17 | |

| 18 | end if |

| 19 | moddecayInterval == 0 then |

| 20 | |

| 21 | end if |

| 22 | |

| 23 | end for |

| 24 | |

The ALNS parameter Settings are shown in the following Table 2.

Table 2.

Algorithm parameter Settings.

5. Computational Experiments and Results Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model and solution algorithm, numerical experiments are conducted using both a standard test network and a real-world road system. All algorithms are implemented on the MATLAB R2021a platform. The lower-level optimization problem at each charging station is solved using the Gurobi 10.0.1 optimizer called via its MATLAB interface.

5.1. Small-Scale Instances

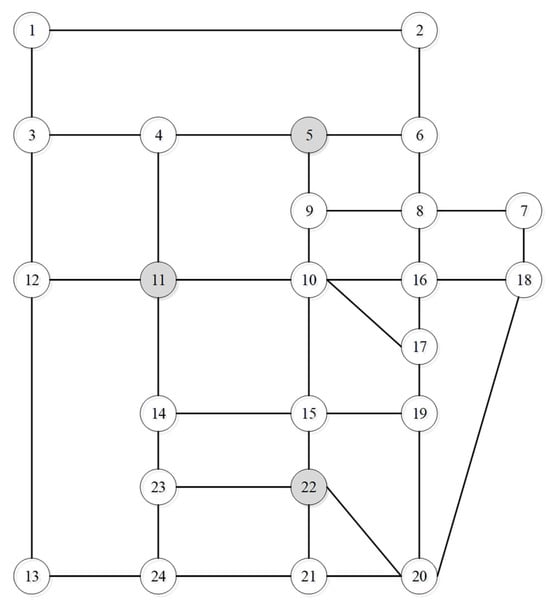

To illustrate the operational status of charging piles under coordinated power allocation and to verify the validity of the proposed model, this section utilizes the classic Sioux Falls transportation network as the test platform. This network topology comprises 24 nodes and 38 links. Charging infrastructure is configured at three nodes: 5, 11, and 22, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the road network of Sioux Falls.

Each station is equipped with 2 charging piles. It is assumed that the total power constraints and electricity procurement prices for each station across different time periods are as specified in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Station power capacity and procurement electricity price per time period.

This table provides the essential input parameters regarding resource availability and operational costs for the charging stations in the optimization model for the subsequent case study simulations. The power constraint limits the total simultaneous charging power at each station per time slot, while the procurement price directly influences the station’s operational revenue calculation within the lower-level model.

Fifteen EVs were generated within the road network for the simulation. Their specific trip information is detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

EV travel information.

Furthermore, the value coefficient for EV users’ waiting time during queuing at charging stations is set at 1 CNY per unit time interval, and the value coefficient for detour cost during rerouted charging is set at 1 CNY per unit distance.

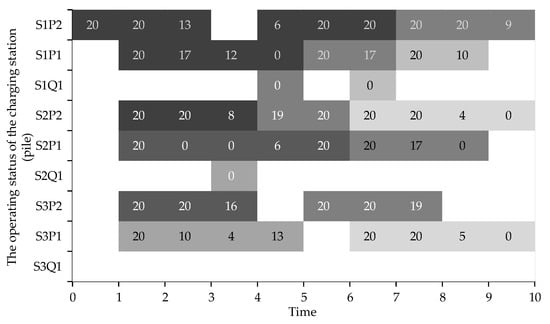

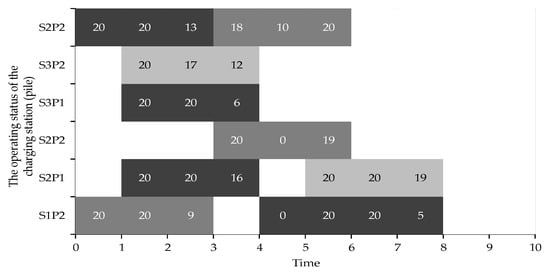

Figure 7 shows an orderly charging scheduling scheme for charging stations considering queuing. The grids of different colors represent different vehicles, and the numbers indicate the charging amounts at different stages. Comparing the proposed model against a non-queuing variant: When queuing is considered (Scenario 1), the charging demands of all 15 EVs are met. In contrast, the charging allocation scheme without considering queuing (a variant of Scenario 3), illustrated in Figure 8. Satisfies the charging demands of only 9 EVs. This starkly demonstrates the critical role of explicitly modeling queuing in enhancing service levels and resource utilization.

Figure 7.

The operation status of the charging piles after considering the scheduling optimization of queuing.

Figure 8.

The operating status of the charging piles without considering the queue.

To test the effectiveness of the proposed improved algorithm, its performance on the small-scale Sioux Falls network case was compared against direct using the Gurobi 10.0.1 optimizer solver. The maximum runtime for both methods was set to 7200 s. The comparative results are summarized in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Comparison of solution results for small-scale instances.

Within the allotted time, Gurobi successfully solved 8 problem instances. A comparison of the results reveals that both methods found solutions with the identical objective value for these instances. This confirms that the algorithm proposed in Section 4 achieves high solution quality for small-scale problems, matching the performance of a state-of-the-art commercial exact solver. Furthermore, comparing the instances with 19 and 20 EVs, the optimal objective values are the same. This indicates that the charging stations were operating at full capacity for the 19 EV case and could not accommodate any additional demand, implying that the charging resource utilization had reached its maximum.

Scalability Analysis: As the problem size increases, Gurobi solution time increases rapidly. This is because the speed of exact solvers is heavily dependent on the size of the model’s solution space. In this problem, the solution space grows exponentially with the number of EVs, primarily due to the proliferation of the charging power decision variables across time periods and vehicles. In contrast, the Improved Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search algorithm effectively manages the problem’s complexity. By decomposing the problem and solving the lower-level station power allocation models separately for each station, the algorithm successfully controls the dimensionality of the decision variables being handled at any one time. Solving three separate lower-level models, each with only about 4 EVs, is computationally far less expensive than solving a single large model encompassing all 12 EVs across all stations simultaneously. Consequently, the solution time for the improved algorithm increases approximately linearly with the number of vehicles, ensuring computational efficiency and making it suitable for larger-scale practical applications.

5.2. Case Study

5.2.1. Case Background and Experimental Setup

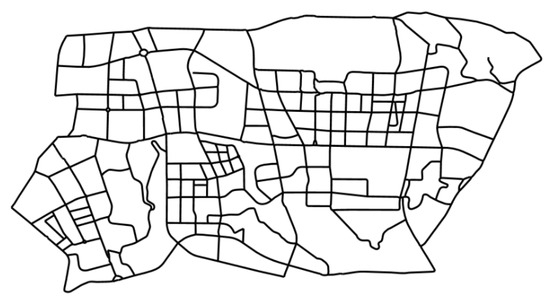

A partial road network from Jiangbei District, Chongqing, China, is selected for the case study. The skeletal structure of the main arterial roads forming this network is illustrated in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

Road network skeleton of a part of Jiangbei district, Chongqing.

Within this road network, five charging stations are selected for the scheduling experiment. Each station is equipped with 5 charging piles. The test period is set from 2:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m., discretized into 15 min intervals, resulting in a total of 24 time slots. According to the relevant Chongqing Time-of-Use electricity price policy documents [41]:

- The period from 14:00 to 17:00 is designated as the peak period, with a charging price of 1.59 CNY/kWh.

- The period from 17:00 to 20:00 is designated as the off-peak period, with a charging price of 0.99 CNY/kWh.

EV travel and charging demands are randomly generated based on the 2017 US National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) statistics, scaled and adapted to the context. The maximum algorithm runtime is set to 7200 s.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed EV charging scheduling strategy, three distinct scenarios are defined for comparative simulation analysis:

- Scenario 1: The proposed integrated approach, considering both coordinated EV charging scheduling and station queuing.

- Scenario 2: A partially coordinated scenario considering station queuing, but where EV users simply choose the nearest charging station without system-level reassignment.

- Scenario 3: A baseline, uncoordinated scenario where EV users only choose the nearest charging station and are unwilling to queue, leaving immediately if no pile is available.

This structured experimental design allows for a clear isolation and evaluation of the individual and combined benefits of the scheduling system and the queuing model, against a common baseline of uncoordinated user choice.

5.2.2. Effectiveness Validation of the Scheduling Strategy

The simulation results for the three scenarios under different EV fleet sizes are presented in Table 6. The analysis reveals the distinct advantages of the proposed scheduling strategy.

Table 6.

Simulation results of EV charging under different scenarios.

Comparing Scenario 1 (Proposed Model) and Scenario 3 (Uncoordinated Charging): The implementation of coordinated EV charging scheduling demonstrates a substantial performance improvement over the uncoordinated mode. As the number of EV users increases, although the coordinated strategy induces some additional travel distance due to detours, it achieves a remarkable increase of up to 40% in the charging demand fulfillment rate. This significant enhancement confirms that the scheduling strategy, by intelligently reallocating vehicles to different stations, effectively alleviates the spatiotemporal mismatch between charging supply and demand and leads to a more efficient utilization of the charging infrastructure resources.

Comparing Scenario 1 (Proposed Model) and Scenario 2 (Nearest Station with Queuing): The superiority of the full scheduling model over the simpler nearest-station policy is also evident. Scenario 1 achieves a charging demand fulfillment rate that is up to 20% higher than that of Scenario 2. Furthermore, when examining the queuing times in Scenarios 1 and 2 under similar fulfillment rates, Scenario 1 reduces the average queuing time by a maximum of 66.7% (observed when the number of users is 35). This clearly indicates that the coordinated scheduling not only serves more users but also significantly alleviates congestion and waiting times at the stations.

Comparing Scenario 2 (Nearest Station with Queuing) and Scenario 3 (Uncoordinated): The analysis of Scenarios 2 and 3 provides insights into the value of queuing alone. In the initial phase of increasing EV user numbers, the charging demand fulfillment rate in Scenario 2 decreases at a slower pace compared to Scenario 3. This suggests that allowing queuing at stations is initially effective in mitigating temporal conflicts in charging demand. However, in the later stages with a high number of EVs, the fulfillment rate in Scenario 2 gradually converges towards that of the uncoordinated Scenario 3. This implies that the marginal benefit of relying solely on queuing to resolve demand conflicts diminishes under heavy load. This is further corroborated by the observation that the queuing times for 55 and 60 users in Scenario 2 are identical, indicating that the station queues have reached their practical upper limit and can no longer effectively absorb additional demand through waiting alone.

In conclusion, the case study validates that the proposed bi-level optimization model (Scenario 1) successfully integrates the benefits of spatial load balancing and temporal demand management, outperforming strategies that rely on either one alone, especially as the system scales. It proves most effective in maximizing service capacity while minimizing user inconvenience due to waiting.

5.2.3. Analysis of ALNS Operator Contributions

The performance of the Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search algorithm hinges on the effective collaboration of its destruction and repair operators. To quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each removal operator to the overall search process, an ablation study was conducted. This method systematically disables individual components to isolate their impact on performance.

The experiment was performed using the 50-EV instance from the Jiangbei District case study. We created five variant configurations of the ALNS algorithm, each identical to the full algorithm except for the disabling of one specific removal operator. Each variant was independently run 10 times to ensure statistical reliability, and the average final objective value was recorded. The results, comparing the performance of each variant against the full ALNS, are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of the ablation study on removal operators (50-EV instance).

The “Max Unserved Users Removal” and “Longest Queue Removal” operators are identified as the most crucial. Disabling them resulted in the most significant performance degradation, with revenue drops of 6.5% and 4.8%, respectively. This strongly indicates that operators specifically designed to alleviate station-level congestion and service failures are paramount. They directly address the core challenge of spatiotemporal demand mismatch by proactively reassigning vehicles from overwhelmed stations. The “Max Conflict Removal” operator also demonstrated considerable importance, with a 2.7% performance drop when disabled. This underscores the necessity of explicitly managing temporal charging conflicts between EVs at the same station, ensuring that the generated schedules are feasible and efficient. While the “Random Removal” and “Max Detour Cost Removal” operators exhibited a smaller individual impact on the final revenue, their role should not be underestimated. These operators are vital for maintaining search diversity. The “Random Removal” operator helps the algorithm escape local optima, while the “Max Detour Cost Removal” operator fine-tunes the spatial distribution of vehicles by addressing suboptimal assignments with high travel costs. Their presence prevents the search from stagnating and enables a more thorough exploration of the solution space.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To analyze the impact of key parameters in the proposed model on charging scheduling outcomes, a sensitivity analysis is conducted based on the experimental setup described in Section 5.2, using the case study with 50 EV users.

5.3.1. Analysis of the Number of Time Intervals on Scheduling Results

In the model formulated in Section 3, the continuous time horizon is discretized into multiple equal-length time intervals to facilitate the implementation of orderly charging and the calculation of EV queuing times. The number of time intervals directly determines the length of each interval, which in turn influences three critical aspects: (a) The precision of calculating EV charging revenue and queuing time. (b) The granularity of charging power control. (c) The size of the model’s solution space and consequently the computational time required.

To systematically evaluate this impact, we test four different configurations for the number of time intervals, i.e., 12, 18, 24, and 36, corresponding to time interval lengths of 30 min, 20 min, 15 min, and 10 min, respectively. The charging scheduling optimization results under these different temporal resolutions are compared and analyzed in terms of key performance metrics including total system revenue, average queuing time, charging demand fulfillment rate, and computational time.

Observation of Table 8 reveals that, when the total scheduling time horizon remains constant, an increase in the number of time intervals leads to a significant expansion of the decision space in the lower-level model of the EV charging scheduling optimization problem. This results in a rapid, non-linear increase in the solver’s computation time. This phenomenon aligns with theoretical expectations regarding model complexity: while finer temporal discretization enhances scheduling precision, it concurrently imposes an exponential growth in computational burden.

Table 8.

Scheduling optimization results under different numbers of time intervals.

It is noteworthy, however, that the increased number of time intervals delivers substantial optimization benefits. The finer time resolution allows for a more precise charging plan at each station, enabling it to better adapt to dynamic grid conditions and user demand. This is directly reflected in the following performance improvements: (a) A notable increase of approximately in the total charging revenue for the stations. (b) A significant reduction of nearly in the average vehicle queuing time. (c) An improvement in charging resource utilization. These enhancements validate the inherent value of fine-grained scheduling for improving overall system performance.

Even with a coarse 30 min step, the relative error in revenue is only 2.52%. This suggests that the revenue calculation is robust against temporal discretization. The relative error in queuing time reaches 23.53% with a 30 min step. More notably, the detour distance shows the highest sensitivity, with an error of 42.70% at the 30 min step. This significant overestimation occurs because coarse time steps cannot accurately capture the precise moments of vehicle arrivals and charging completions, leading to imprecise waiting time calculations and substantial errors in route optimization. The errors for this bulk energy metric range from 1.32% to 0.44%, indicating that time granularity primarily affects time-sensitive and routing metrics rather than total delivered energy. Reducing the number of time slots from 36 to 24 (increasing the step from 10 to 15 min) results in a substantial 68.7% reduction in computation time, while maintaining reasonable error levels for most metrics.

Based on this comprehensive error-efficiency trade-off analysis, we recommend a 15 min time step (24 time slots) as the minimum practical time step for implementing the proposed scheduling strategy. The 15 min step represents the optimal compromise where the marginal improvement in accuracy from further refinement to 10 min does not justify the substantial additional computational cost, particularly for the critical detour distance metric.

To address the computational efficiency bottleneck associated with a large number of time intervals, this study proposes a distributed computing framework to alleviate the computational burden. Specifically, in a practical charging scheduling operation, the task of solving the lower-level model can be delegated to and computed locally by individual charging stations. This distributed solution approach not only effectively mitigates the computational challenge but also provides a feasible and practical technical pathway for the real-world deployment of large-scale EV charging scheduling systems.

To assess the practical scalability of the proposed algorithm for large-scale deployments, this section evaluates its performance in a distributed computing environment. The experimental setup follows the 50-EV case from Section 5.2, executed on a computing cluster with 1, 2, and 4 nodes.

The results in Table 9 demonstrate compelling scaling characteristics. The near-linear speed-up and high parallel efficiency stem from the natural parallelism in our bi-level framework: once the upper-level assigns EVs to stations, the lower-level problems for each station become independent and can be solved concurrently across different nodes with minimal communication overhead.

Table 9.

Performance analysis of distributed computing (50 EVs Case).

This analysis confirms that our method is not only algorithmically sound but also computationally tractable for real-world, large-scale applications through distributed implementation.

5.3.2. Analysis of Different Cost Coefficients on Scheduling Results

In EV charging scheduling, users may have different charging preferences, making it necessary to analyze how these varying preferences influence the scheduling outcome. This can be achieved within the model by assigning different values to the detour cost coefficient (α) and the queuing time cost coefficient (β), which represent the user’s relative aversion to detours versus waiting. During periods of high charging demand, users can be given an option to state their preference: Priority on Minimizing Detour, Priority on Minimizing Queuing Time, or Neutral.

When a user’s detour cost coefficient (α) is high and their queuing time coefficient (β) is low, the user will preferentially choose to queue and wait at a busier station. Conversely, if α is low and β is high, the user will preferentially choose to detour to a less congested station. When both α and β are either high or low, it indicates a consistent preference level regarding both detours and queuing.

We assume that the basic detour value coefficient (α) is set at 1 CNY/km and the basic queue time value coefficient (β) is set at 36 CNY/hour. A percentage parameter γ was introduced to represent the intensity of user preference. A higher γ value indicates a greater tendency to minimize detours or queue time. To observe and compare the impact of different user preference combinations on the scheduling results, we designed four user composition scenarios with different preference distributions, as detailed in Table 10.

Table 10.

Combinations of user preferences in different proportions.

Based on the model parameters and EV user trip data from the experimental setup in Section 5.2, a charging scenario with 50 randomly generated EV users is created. The EV charging scheduling problem is solved for each of the four preference combinations in Table 10. The influence of different preference types and their intensities on the scheduling results is then analyzed; the key results are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Scheduling results under different user preference combinations and preference intensities.

Observations from the results for different preference combinations: Comparing Combination 1 and Combination 4, Combination 4 has a smaller proportion of users with a neutral preference than Combination 1. This results in a slightly higher total station revenue and a shorter total detour distance for Combination 4. This suggests that the scheduler in Combination 4 directs more EVs to detour, thereby alleviating congestion at critical stations and enabling better utilization of off-peak electricity prices.

Comparing Combination 2 and Combination 3, it is found that a higher proportion of users who prioritize minimizing queuing time (Combination 2) leads to an overall shorter total detour distance. However, this concentrates demand, causing congestion and long queues at some stations, forcing some vehicles to charge during high-price periods, which ultimately yields high station revenue. Conversely, a higher proportion of users who prioritize minimizing detour distance (Combination 3) results in a longer total detour distance but a more balanced distribution of charging demand across stations. This offers slightly greater charging flexibility, allowing more charging to occur during low-price periods, which also leads to relatively high station revenue. Furthermore, across all preference combinations, a higher preference intensity (γ) among users exerts a stronger influence on the final scheduling results.

5.3.3. Analysis of the Impact of the Detour Value Coefficient on Scheduling Results

To incentivize EV users to comply with charging scheduling arrangements, charging stations can offer corresponding economic compensation to users who accept detours for charging. The lower limit of this compensation amount is the actual detour cost incurred by the user, which serves as the benchmark for determining the compensation standard. While the model assumes users will fully adhere to scheduling instructions, in reality, user acceptance of compensation amounts may vary. To ensure fairness, a standardized detour compensation is paid to all users who traverse the same detour distance. From an operational cost perspective, detour compensation constitutes a significant expenditure item for the scheduling system.

To investigate the impact of different detour value coefficients (α) on charging station operational strategies, a sensitivity analysis is conducted by testing a gradient of α values ranging from 0.5 to 2.75. This setup systematically observes the dynamic changes in station revenue and the number of EVs served. In this experimental design, all other parameters are held constant. The detailed scheduling results are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Scheduling optimization results under different detour value coefficients.

As shown in Table 12, when the detour value coefficient (λ) varies within the range of [0.5, 2.75], the implementation of charging scheduling consistently demonstrates significant advantages compared to the uncoordinated charging mode. As the value of λ increases, the growth rate of system revenue shows a diminishing trend, while the scheduling compensation costs initially increase and subsequently decrease. This phenomenon stems from the erosion effect of compensation costs on operating profits: when the compensation standard rises beyond a certain level, the pro-activeness of charging stations to perform scheduling diminishes accordingly. Operators tend to reduce scheduling frequency or only schedule EVs to nearby stations, resulting in some immediate charging demands remaining unfulfilled. This ultimately weakens the potential for optimizing EV charging in both spatial and temporal dimensions.

5.3.4. Analysis of the Incentive Effect of Time-of-Use Electricity Pricing on Station Operations

Procurement cost of electricity is a critical variable determining the profitability of charging stations. To mitigate grid load fluctuations, power supply systems implement Time-of-Use pricing mechanisms. By setting high electricity prices during peak hours and low prices during off-peak hours, these price signals guide charging stations to concentrate their charging activities during periods of abundant power supply. This price transmission mechanism can be extended to the user side. Charging stations, by adopting TOU pricing strategies for EV users, can effectively reshape the distribution of charging demand across different time periods, achieving peak shaving and valley filling from the perspective of supply–demand relationships.

This experiment employs a fixed electricity selling price. The theoretical rationale is that TOU pricing essentially alters the temporal distribution of demand through price elasticity. When charging demand exhibits rigid characteristics, the effectiveness of the TOU pricing policy is significantly diminished. In this context, the profit margin of the charging station depends primarily on the difference between the selling price and the procurement price.

Furthermore, the electricity consumption pattern of a charging station is constrained by the parking duration of the EVs. To investigate the incentive effect of the TOU pricing mechanism on charging power control, this study constructs experimental scheduling scenarios combining different TOU pricing schemes with varying vehicle dwell times. By comparing and analyzing key performance indicators such as operational revenue and service completion rate, the practical effectiveness of TOU pricing policies in promoting grid peak-valley balance is systematically evaluated.

Analysis of the data characteristics in Table 13 reveals the following: When the off-peak electricity price is held constant at 0.3 CNY/kWh, and the peak price increases from 0.5 to 0.8 CNY/kWh, the electricity procurement cost continuously rises, leading to a narrowing of the charging station’s marginal profit margin. Concurrently, the expanding peak-to-off-peak price differential strengthens the economic incentive for stations to guide vehicles to charge during off-peak hours. Although scheduling costs increase accordingly, the charging service coverage rate improves significantly. Conversely, when the peak price is fixed at 0.9 CNY/kWh, an increase in the off-peak price from 0.4 to 0.7 CNY/kWh compresses the price differential. This weakens the incentive for scheduling charging to the valley periods, resulting in reduced scheduling efforts and a contraction in the scale of service.

Table 13.

Optimization results of different electricity price dispatching.

Comparative analysis of charging data under different pricing policies indicates a significant positive correlation between the magnitude of the peak-to-off-peak price differential and the pro-activeness of charging stations to implement orderly scheduling. Specifically, a larger price differential corresponds to an increase in the number of vehicles served by the stations. Grid operators can effectively stimulate charging stations to actively engage in temporal power coordination management by widening the peak-to-off-peak price gap. This approach not only enhances the utilization rate of charging infrastructure but also positively contributes to flattening grid load fluctuations.

5.3.5. Analysis of Heterogeneous and Non-Linear Charging Characteristics of Electric Vehicles

To validate the robustness of the proposed model under non-idealized conditions, this section conducts a sensitivity analysis focusing on two key assumptions: electric vehicle parameter heterogeneity and non-linear charging curves.

- (1)

- Analysis of EV Parameter Heterogeneity

To evaluate the model’s sensitivity to heterogeneity in EV parameters, three test scenarios were designed based on the 50 EV case study from Section 5.2, and compared against the original homogeneous baseline:

Scenario H1 (Heterogeneous Capacity): EV battery capacity was uniformly distributed between 40 kWh and 80 kWh, while the maximum charging power remained constant (20 kW).

Scenario H2 (Heterogeneous Power): Maximum charging power was uniformly distributed between 20 kW and 60 kW, while battery capacity remained constant (60 kWh).

Scenario H3 (Mixed Heterogeneity): Both battery capacity (40–80 kWh) and maximum charging power (20–60 kW) were randomized simultaneously.

The scheduling results under these scenarios are summarized in Table 14.

Table 14.

Comparison of scheduling results under EV parameter heterogeneity.

The results indicate that the performance ranking of the three strategies remains consistent under varying degrees of parameter heterogeneity. The proposed integrated scheduling strategy (Scenario 1) consistently and significantly outperforms both the partially coordinated (Scenario 2) and uncoordinated (Scenario 3) benchmarks in terms of the number of EVs served and total revenue. Although minor fluctuations are observed in absolute performance metrics. This indicates that coordinated scheduling has effectively enhanced the system efficiency. Notably, the presence of heterogeneous charging power (H2) slightly reduced the average queuing time in Scenario 1, potentially because some high-power EVs shortened their service duration, introducing flexibility into the system.

- (2)

- Impact of Non-linear Charging Curves

Actual EV charging follows a non-linear constant-current, constant-voltage (CC/CV) profile, unlike the idealized linear assumption. To estimate the error introduced by the linear assumption, a post hoc analysis was performed.

Three representative EVs with low, medium, and high charging demands were randomly selected from the baseline homogeneous scenario results. The total time required to fulfill their charging demand was calculated using both the linear model and a simplified CC/CV model. The CC/CV model was parameterized to charge at maximum power until reaching 80% State of Charge, followed by a constant-voltage phase up to 100% SOC, with charging power decreasing linearly. The experimental results in different situations are shown in Table 15 below.

Table 15.

Comparison of charging times: linear vs. CC/CV model.

The linear model systematically underestimates the total charging time, with errors ranging from 4 to 7 min, corresponding to a relative error of approximately 5% to 8%. This stems from the power tapering in the final constant-voltage stage of the CC/CV curve. Within the 15 min discrete-time framework, this error implies that the model-predicted “charging completion period” might be one period earlier than in reality. This could potentially lead to minor scheduling conflicts in practice, e.g., a charging pile predicted to be free at the end of period might actually become available at the beginning of period .

The discretization of continuous charging processes into time slots for scheduling is a well-established simplification in both academic and practical contexts [34,35], valued for providing a computationally tractable and efficient decision-making framework for complex problems. This error is manageable and compensable. In practical operation, its impact can be mitigated by incorporating an operational safety margin, for instance, by adding a buffer period after the model-predicted charging completion time or by including a small redundancy in the target charging amount . Most importantly, the error is systematic and does not alter the relative performance comparison between the different scheduling strategies. The core contribution of this study is to demonstrate the significant superiority of the coordinated scheduling mechanism over uncoordinated strategies. This qualitative conclusion remains robust despite the minor quantitative inaccuracy introduced by the linear assumption.

In summary, the sensitivity analysis confirms that, while the linear charging assumption introduces a quantifiable and manageable error, the core conclusions and advantages of the proposed model and methodology remain robust when confronted with vehicle heterogeneity and realistic charging physics.

5.4. Extended Experiments with Time-Varying Traffic Congestion

To validate the robustness of the proposed model under realistic traffic conditions, this subsection introduces time-varying traffic congestion effects in both a standard test network and a large-scale real-world case study, with corresponding enhancements to the user decision model.

5.4.1. Small-Scale Network Experiment

This experiment was conducted on the Sioux Falls network described in Section 5.1. The following key modifications were implemented to simulate traffic:

The BPR function was employed to calculate the travel time for each link : , where is the free-flow travel time, is the link capacity, and is the traffic volume on the link during time period l. The parameters were set to , . And a fixed background traffic matrix was generated to simulate the typical road network traffic congestion state

In this experiment, both the user’s default behavior (baseline) and the system’s scheduling decisions were based on the least-time path. Consequently, the basis for detour compensation was shifted from distance to time. The compensation was calculated as: , where is the shortest travel time to the assigned station i, and is the shortest travel time to the user’s originally nearest station. The coefficient here represents the value of time (CNY/min).

The performance of the three scheduling strategies under time-varying congestion in the Sioux Falls network is compared in Table 16.

Table 16.

Scheduling performance comparison under time-varying congestion in a small-scale network (15 EVs).

The results demonstrate: Under traffic conditions, the proposed coordinated scheduling strategy (Scenario 1) successfully served all 15 EVs and maintained a significant advantage in total system revenue. This confirms that the core value proposition of coordinated scheduling for enhancing overall system efficiency remains valid even in congested environments.

Compared with scenarios that do not take into account the state of road network congestion, the total system travel time increased across all strategies. However, the intelligent scheduling in Scenario 1 resulted in a lower total travel time than the partially coordinated strategy (Scenario 2). This indicates that the proposed strategy not only responds to congestion but also partially mitigates its effects by optimizing station assignment, demonstrating its comprehensive optimization capability across both spatial and temporal resources.

5.4.2. Large-Scale Case Study

This experiment enhanced the Chongqing Jiangbei District case study from Section 5.2 by integrating real-world time-varying traffic data.

We used the historical average road speed data of a typical working day to simulate the road network congestion state, in order to reconstruct the time-varying traffic conditions of the day, with a time resolution of 15 min. To quantify the impact of traffic congestion, two contrasting scenarios were defined:

Ideal scenario: Ignore congestion; Routing is based on the shortest time path using the free flow speed.

Congestion scenario: Routing is based on time-varying travel times derived from real-world data.

Consistent with Section 5.4.1, the time-based compensation calculation was used.

The scheduling results for a fleet of 50 EVs, with and without consideration of real-world traffic congestion, are compared below Table 17.

Table 17.

Scheduling performance comparison with and without real-world traffic congestion in the large-scale network (50 EVs).