Abstract

This study extends our previous investigation into whether multimodal large language models (MLLMs) can reason about physical reasoning, using a game environment as the testbed. Stability served as a foundational scenario to probe model understanding of physical reasoning. We evaluated twelve models, combining those from the earlier study with six additional open-weight models, across three tasks designed to capture different aspects of reasoning. Human participants were included as a reference point, consistently achieving the highest accuracy, underscoring the gap between model and human performance. Among MLLMs, the GPT series continued to perform strongly, with GPT-4o showing reliable results in image-based tasks, while the Qwen2.5-VL series reached the highest overall scores in this extended study and in some cases surpassed commercial counterparts. Simpler binary tasks yielded balanced performance across modalities, suggesting that models can capture certain basic aspects of reasoning, whereas more complex multiple-choice tasks led to sharp declines in accuracy. Structured inputs such as XML improved results in the prediction task, where Qwen2.5-VL outperformed GPT variants in our earlier work. These findings demonstrate progress in scaling and modality design for physical reasoning, while reaffirming that human participants remain superior across all tasks.

1. Introduction

Multimodal large language models (MLLMs) have recently emerged as powerful systems that integrate text and image understanding [1,2,3,4]. However, despite their impressive abilities in processing visual and textual information, current MLLMs face notable limitations in tasks that require physical reasoning and spatial understanding. Prior work has demonstrated that these models face remarkable challenges in intuitive physics tasks, such as reasoning about object permanence [5,6], structural stability [7], physical simulation [8], and causal interactions [9]. Human-derived evaluation is essential for capturing the nuanced physical reasoning that automated metrics often miss. Nevertheless, our earlier work [7], while revealing these model limitations, overlooked such human benchmarks and relied only on a narrow set of models.

Our earlier work evaluated a set of MLLMs on stability-related tasks within a procedural game environment. The work evaluated the performance of MLLMs of different parameter sizes, including both open-source and closed-source models. However, it was limited to a few models and did not include human performance. The research from [10,11] provides an insight that higher parameter counts lead to significantly improved understanding and capabilities in language models. These observations highlight the need for a broader investigation of both model capabilities and design factors. By evaluating both high-parameter and low-parameter MLLMs, this research aims to unpack scaling effects on physical understanding.

The importance of incorporating human judgment in AI evaluation has become increasingly recognized, as automated metrics often struggle to align reliably with human assessment [12], especially for complex multimodal tasks [13,14]. Human evaluation serves as the gold standard for assessing model performance because it provides contextual understanding, ethical considerations, and nuanced judgment that automated systems may overlook. A study by Stein et al. [15] showed that human evaluations can uncover model capabilities and limitations not captured by conventional metrics, particularly in tasks requiring subjective interpretation or complex reasoning.

Hence, this paper extends our previous work [7] on evaluating stability reasoning in MLLMs. We conducted an exploratory study to examine how models and humans judge stability across binary, comparative, and predictive tasks in procedural game environments. This paper provides the following key contributions:

- Inspired by our previous study, we deliver an updated empirical benchmark evaluating a range of MLLMs, including newly added open-weight models, on stability judgment tasks in game-inspired environments.

- We design three task types—binary, comparison, and prediction—across multiple input modalities to probe different aspects of physical reasoning.

- We analyze scaling effects of MLLM performance in physics tasks, providing critical insights for future model development.

2. Related Work

MLLMs have emerged as transformative tools in artificial intelligence, demonstrating remarkable capabilities in understanding and reasoning across diverse modalities, including text, images, audio, and video. These models represent a significant advancement beyond traditional unimodal approaches by integrating powerful large language models (LLMs) with various modality encoders, positioning LLMs as the “brain” while treating visual [16] and other sensory encoders [17,18] as specialized organs. The potential of MLLMs to emulate human-like cognitive abilities has rekindled interest across multiple domains, from robotic control [19,20] to scientific reasoning [21], marking a potential pathway toward achieving artificial general intelligence.

Our previous research [7] investigated MLLMs’ physical reasoning capabilities using the Science Birds platform, an Angry Birds-inspired physics simulation. This work evaluated binary and comparative stability assessment along with forward simulation through visual and textual inputs. The findings demonstrated quantifiable accuracy in visual reasoning tasks while revealing significant performance variations based on model architecture and input modality. The study highlighted multimodal integration’s importance for accurate physical inference while exposing substantial limitations in structured visual reasoning tasks requiring deep understanding of stability principles and object interaction dynamics.

The role of human evaluation extends beyond performance assessment to encompass fairness, ethics, empathy, and inclusivity. A study from Stein et al. [15] showed that human judgment can reveal model capabilities and limitations often overlooked by automated evaluation metrics. Benchmarks such as HumaniBench [22] highlight that even state-of-the-art MLLMs often struggle to balance accuracy with human-aligned principles. This underscores the necessity of human evaluation in guiding model development toward outcomes that are both technically sound and socially responsible.

3. Methodology

3.1. Tasks

Physics-based games provide rich environments for artificial intelligence (AI) research because they combine well-defined rules with complex dynamic interactions. Among them, Angry Birds has become a widely used testbed, as its gameplay integrates complex mechanics such as gravity, collision, and balance. In this environment, level design requires careful attention to stability, since structures must remain intact and playable under the game’s physics engine. Within this context, two key challenges remain. The first is generating levels that achieve controllable similarity to reference designs while maintaining diversity, and the second is investigating the ability of language models to handle stability-related scenarios in physics-driven environments.

The design of the three tasks in our previous work [7] and this study was motivated by the need to evaluate MLLMs at different levels of physical reasoning, while ensuring comparability with our previous work. First, the binary task provides a foundational measure, as determining whether a given structure is stable or unstable represents the most direct form of physical judgment. The comparison task, the second one, extends this evaluation by introducing a relative dimension, requiring the model to assess multiple input structures and identify the one that differs in stability, either the single stable structure among unstable ones or the single unstable structure among stable ones. To increase variability and difficulty, the number of candidate options varies between two, three, and four.

The third one is the prediction task, which further increases complexity by requiring the model to anticipate future states of a structure after a specified time, thereby testing the model’s capacity for temporal reasoning rather than static evaluation. The prediction horizon was fixed at 10 s, consistent with prior work [23]. We assume that beyond 10 s no further changes occur, as the simulation reaches a final state where structures remain stable or unstable. It contains three subtasks: “diff_block”, where options differ in block quantity; “diff_level”, where arrangements vary despite equal block counts; and “diff_id”, where structures appear identical but differ in block identifiers. These subtasks collectively probe the model’s ability to simulate structural dynamics under variations in quantity, arrangement, and identity, thus providing a comprehensive test of temporal reasoning. By integrating these tasks, we establish a robust benchmark that highlights the limits and potentials of multimodal reasoning, fostering deeper exploration of language models’ physical reasoning capabilities.

3.2. Model Selection

To extend the original evaluation, six additional open-weight MLLMs were incorporated in this study, i.e., Gemma3-12B [3], Gemma3-27B [3], LLaVA-13B [4], LLaVA-34B [4], Qwen2.5-VL-32B [2], and Qwen2.5-VL-72B (Q4) [2]. These models were selected to provide a more comprehensive assessment of multimodal reasoning capabilities, particularly for physical stability tasks. The selection criteria were based on the models’ relevance to the previously evaluated series with parameters below 8B, ensuring continuity and comparability with the earlier experiments.

Among the selected models, Qwen2.5-VL-72B was evaluated using the Q4 quantization format due to computational resource constraints, allowing efficient inference without significantly affecting performance. By including models across different architectures and parameter scales, this extended evaluation investigates whether larger models or specific architectures demonstrate improved reasoning about physical stability tasks. The subsequent analysis maintains the same experimental framework used in the original study, providing a consistent basis for comparison across all models.

3.3. Prompting Strategy

We employed three commonly used prompting approaches—zero-shot, null-shot [24], and chain-of-thought (CoT) [25]—to ensure fairness and comparability across models. These approaches were selected to avoid potential bias that may arise from task-specific fine-tuning or instruction engineering, thereby providing a fair comparison across models without relying on prompt-specific optimizations. A minimal role-based instruction was included for models (e.g., “You are a level designer for the Angry Birds game”) to provide basic task grounding, while human participants received only the neutral task description without any domain framing. The same prompt templates as in our previous study [7] were reused to maintain continuity of experimental design. These prompting choices guided both the model evaluation and the human user study, with implementation details described in Section 4.1.

3.4. Human Performance as Descriptive Baseline

To establish a human performance baseline, a survey was conducted using the same set of physical stability tasks presented to MLLMs in the preceding study. These tasks encompassed three categories: binary (Task 1), comparison (Task 2), and prediction (Task 3). The selection of these categories aimed to capture a comprehensive range of reasoning capabilities relevant to physical stability, ensuring consistency with the tasks evaluated by the MLLMs.

Recognizing the potential for participant fatigue, the survey was designed to mitigate this factor by limiting the number of questions and not utilizing the entire dataset. This approach was intended to maintain participant engagement and ensure the reliability of responses. Additionally, to facilitate intuitive human understanding, only the image modality was employed in the survey. The use of textual representations, such as XML or JSON formats, was excluded due to their complexity and the challenge they pose for human participants in interpreting physical environments effectively.

To further enhance the reliability of the responses, an additional question was incorporated into Task 1 as a duplicate. This strategy aimed to identify inconsistencies in participants’ answers, which could indicate a lack of careful consideration or engagement with the survey. By comparing responses to original and duplicate questions, we confirmed that participants gave answers with purposefulness, ensuring reliability in the collected data.

Human performance in this study serves as a descriptive baseline, following established practices in recent physical reasoning and multimodal AI benchmarks such as PHYRE [26] and I-PHYRE [27], where human data provide empirical context for evaluating model accuracy rather than theoretical interpretation. In line with these studies, human results function as quantitative reference points that help calibrate model capabilities without inferring underlying cognitive mechanisms. Consistent with recommendations for transparent benchmarking, we interpret differences between human and MLLM results as empirical capability gaps rather than evidence of distinct reasoning strategies. In this way, human data contextualize what can be achieved by non-expert participants under the same task conditions, offering a practical reference for assessing model performance in this domain.

To compare human performance with MLLM predictions, we employed two-stage bootstrap resampling to generate empirical distributions of mean accuracy for each task. This approach estimates confidence intervals and captures variability without normality assumptions. Comparing these distributions with MLLM scores allows robust, non-parametric testing of statistically meaningful differences in reasoning performance.

4. Results and Discussion

The evaluation results reveal meaningful differences between human participants and MLLMs, alongside notable variability in model performance across the range of tasks.

4.1. Experiment

4.1.1. Model Evaluation

Models were evaluated on three tasks: binary classification, comparative selection, and predictive reasoning. In each case, the instructions were tailored to the task—for example, deciding whether a structure was stable or unstable (Task 1), selecting the most stable option among candidates (Task 2), or predicting which modified variant would remain stable (Task 3). Each task consisted of 300 curated samples, with balanced distributions of stable and unstable cases for Task 1, balanced choice options for Task 2, and three distinct subtasks (“diff_block,” “diff_id,” and “diff_level”) for Task 3. Models were tested under three input modalities: image, JSON, and XML. To ensure deterministic outputs, the temperature parameter was set to zero across all evaluations. This design allowed us to compare reasoning performance across visual and symbolic representations. Representative examples of XML prompts for each task are provided in Appendix A, illustrating the exact input format shown to the models. JSON and image prompts followed the same task-specific framing.

4.1.2. Human User Study

The tasks presented to human participants were derived from the same set of tasks: binary, comparison, and prediction tasks. To facilitate participant judgement, and as outlined in Section 3.4, only the image modality was employed, excluding complex textual representations such as XML or JSON. This design allows humans to focus on visual stability cues while maintaining alignment with the multimodal evaluation of the models.

In constructing the survey questions for each task, we adopted a principle similar to zero-shot prompt engineering, ensuring that the questions were kept deliberately basic and direct to minimize ambiguity while capturing essential reasoning about physical stability. Given that the dataset includes both stable and unstable structures, questions were evenly sampled from these two categories to provide a balanced assessment. A strict rule was applied to maintain challenge and consistency across all tasks. Each question structure contained exactly twelve blocks. Candidate questions were first filtered based on this rule and subsequently selected at random to ensure variety.

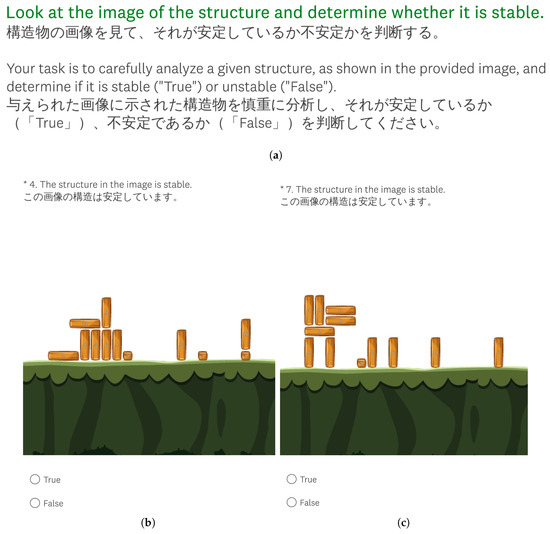

Task 1 consisted of 10 questions, evenly split between 5 stable and 5 unstable structures. The corresponding instruction and example questions are illustrated in Figure 1, where panel (a) shows the instruction provided to participants and panels (b) and (c) present sample questions depicting a stable and an unstable structure, respectively. Task 2 followed a similar set, also comprising 10 questions balanced across stable and unstable conditions, but with the addition of a four-option multiple-choice format based on images. Task 3 was designed to cover three distinct subtasks (“diff_block”, “diff_id”, and “diff_level”), selecting 5 questions for each subtask, resulting in a total of 15 questions. This careful selection process ensures that the experimental design is both challenging and representative of the dataset, enabling meaningful evaluation of human performance relative to multimodal models. The example instructions and questions for Tasks 2 and 3 are provided in the repository.

Figure 1.

Instruction and corresponding questions used in Task 1 of the user study. (a) Instruction provided for Task 1. Question depicting a stable (b) and an unstable (c) structure.

4.2. Performance of Multimodal Models

Building on the experimental framework, this subsection presents the results of MLLMs evaluated on the three tasks. Namely, we analyze model accuracy, error patterns, and the influence of architecture and parameter scale across them. These results reveal the strengths and limitations of the models’ reasoning capabilities and set the stage for a comparison with human performance.

The results in Table 1 reveal several notable patterns in the performance of MLLMs across tasks and modalities. Consistent with our previous study [7], most models show a gradual decline in accuracy when shifting from Task 1 to Task 3, indicating that longer contexts and more complex reasoning demands continue to challenge current architectures. At the same time, the overall mean performance of most models has increased compared to the previous study, suggesting that scaling contributes to performance gains. An exception is LLaVA-34B, which did not follow this trend. Qwen2.5-VL-72B achieved the highest overall performance among the models evaluated in this study. In particular, it surpassed both GPT-4o and GPT-4.1 mini from the previous study in the XML modality of Task 3, reaching an accuracy of 0.91. This advantage aligns with the claims in the Qwen2.5-VL technical report [2], which highlights the model’s strength in handling text-rich scenarios.

Table 1.

Performance of MLLMs on physical reasoning tasks across modalities.

Furthermore, a clear parameter-scaling effect is observed within the Qwen2.5-VL family. Both the 32B and 72B variants demonstrate measurable improvements, highlighting the importance of scaling in supporting more robust multimodal reasoning. In contrast, LLaVA-34B exhibited the lowest overall accuracy, with a particularly severe drop in Task 3 JSON format, suggesting potential deficiencies in structured data exposure during training. These results underscore that while larger parameter counts enhance general multimodal reasoning, training strategies and modality-specific data coverage remain equally critical. Overall, the findings highlight the need for further research into the physical reasoning abilities of MLLMs, showing that performance depends not only on model size but also on the interaction between modality, task complexity, and training objectives.

To further assess model robustness, we examined the number of invalid responses across tasks, modalities, and models, as shown in Table 2. An invalid response occurs when the model fails to generate a parsable or meaningful output during the answer extraction process. Overall, invalid responses were most frequent in the JSON modality, far exceeding those observed for image and XML. This pattern was most evident in LLaVA-34B, which recorded the highest number of invalid responses in Task 2 and Task 3. These findings indicate that structured formats such as JSON pose challenges for some large-parameter models, likely due to uneven training data exposure.

Table 2.

Frequency of invalid responses by each model across the three core tasks.

A secondary observation is that invalid response rates show diverse patterns across models and modalities, rather than a consistent decline with increasing parameter size. For instance, Gemma3 demonstrates a clear decrease in invalid responses across modalities and tasks, suggesting improved reliability within this family. In contrast, LLaVA-34B performs substantially worse under the JSON modality despite its larger size in Task 2 and Task 3, highlighting that scale alone does not guarantee robustness. Across tasks, invalid responses were least frequent in Task 1 and most frequent in Task 3, indicating that more complex tasks exacerbate validity issues. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating not only accuracy but also response validity, since invalid outputs can distort performance comparisons across tasks and modalities.

4.3. Comparison with Human Judgments

To contextualize model performance, we compared MLLM outputs with judgments from 14 human participants collected through the user study. Participants completed the same tasks under the constraints outlined in Section 3.4 and Section 4.1: image-only modality, balanced stable and unstable structures, and random selection of candidate questions. Their responses provide a clear empirical reference for evaluating MLLM accuracy under identical task conditions.

As described in Section 3.4, a duplicate question was included in Task 1 to assess response reliability. This mechanism ensured that participants were attentive and engaged with the survey. All 14 participants provided consistent answers for the duplicate question, confirming the reliability of the human responses.

Table 3 presents the performance of humans and selected MLLMs on the stability reasoning tasks. For model comparison, we included the highest-scoring model from this study (Qwen2.5-VL-72B) and the highest-scoring model from the previous study (GPT-4o) to establish representative reference points. Although MLLMs were originally evaluated on all 300 levels across modalities, we also report their performance on the same 35 image-based items to enable fair comparison with human participants. Human participants demonstrated high accuracy across tasks, with particularly strong results in Task 1 (0.91) and Task 2 (0.83), though performance was lower in Task 3.

Table 3.

Performance of human participation and MLLMs.

Human participants achieved consistently high accuracy across tasks, especially in the binary and comparison categories, whereas models exhibited larger variability across modalities and subtasks. These results illustrate the present empirical performance gap between human participants and current MLLMs in physical reasoning tasks. However, as clarified in Section 3.4, the human data are used strictly as a descriptive reference to contextualize model capabilities. We do not interpret these differences as evidence of distinct reasoning mechanisms or perceptual strategies, but rather as measurable disparities in task accuracy. In this way, the human benchmark serves to indicate what level of performance can be achieved under identical conditions, providing a practical frame for assessing progress in multimodal physical reasoning.

In contrast, the models showed more variability. GPT-4o performed perfectly on stable structures in Task 1 but failed on unstable structures, resulting in an overall accuracy of 0.50. Qwen2.5-VL-72B showed a more balanced performance between stable and unstable conditions in Task 1 (0.40 and 0.60, respectively), but its overall accuracy remained lower than that of human participants across most subtasks. For Task 2, which involved multiple-choice options, human accuracy remained relatively high (0.83), whereas both models struggled to consistently identify stable and unstable structures, highlighting the difficulty of integrating visual cues under more complex formats.

In Task 3, humans maintained strong performance on “diff_block” and “diff_level” subtasks, but lower accuracy on “diff_id” subtasks (0.60), reflecting subtle challenges in recognizing structural identity differences. Interestingly, GPT-4o achieved higher accuracy than humans on the “diff_block” and “diff_id” subtask, with a larger difference observed in “diff_id”, suggesting that the model can sometimes detect small visual details more consistently than human participants. Nevertheless, the models exhibited inconsistent performance across other subtasks, indicating that current MLLMs still face significant limitations in capturing nuanced human-like reasoning about physical stability.

To assess the statistical significance of differences between human participants and MLLMs at the subtask level, we employed a two-stage bootstrap approach suitable for two independent groups. This method considers participant variability and the limited number of questions (items) in each task, ensuring reliable estimates despite the small sample size. The procedure was applied consistently across all three tasks. Task 1 and Task 2 each consisted of 10 questions, evenly divided between stable and unstable structures, while Task 3 comprised 15 questions partitioned into three subtasks (“diff_block”, “diff_id”, and “diff_level”). Each scenario was analyzed separately to ensure that bootstrap estimates accurately capture performance differences at a fine-grained level.

Human participant responses were represented as matrices of size 14 × number of questions per task, whereas model outputs were represented as 12 × number of questions and treated as fixed for bootstrap resampling. Notably, the set of 12 models (Group B) consisted of both the MLLMs evaluated in this study and those reported in prior work, providing a broader comparative perspective. This approach enabled a direct and fair comparison between humans and models for each subtask while capturing the uncertainty arising from both question-level and participant-level variability.

Table 4 summarizes the bootstrap results comparing human participants (Group A) and MLLMs (Group B) across three tasks and their subtasks. Group A and Group B means represent the average accuracy of humans and models, respectively, while the observed difference (A–B) reflects the accuracy gap between the two groups. In Task 1, humans achieved significantly higher accuracy than models for both stable (0.59, p = 0.001) and unstable (0.22, p = 0.039) subtasks, demonstrating stronger physical reasoning in identifying stability. In Task 2, humans again outperformed models, with differences of 0.62 (p < 0.001) for stable and 0.51 (p < 0.001) for unstable subtasks. This confirms that human participants apply more reliable reasoning when evaluating relative stability across multiple structures.

Table 4.

Bootstrap comparison of human participants (Group A) and MLLMs (Group B) across tasks. Reported values include group means, observed mean differences, bootstrap standard errors, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values.

In Task 3, the results were more varied. Humans showed clear advantages in “diff_block” (0.63, p < 0.001) and “diff_level” (0.55, p = 0.001), indicating stronger reasoning when assessing the consequences of structural changes. In “diff_id”, the difference (0.23) was not statistically significant (p = 0.167), suggesting that MLLMs performed closer to humans when the task relied on recognizing object identity. It is worth noting that several subtasks report p-values of 0.000. These should be interpreted as p < 0.001, reflecting extremely small values below the reporting threshold and providing strong evidence of significant differences. Overall, humans consistently demonstrated superior physical reasoning across most tasks, while MLLMs exhibited comparable performance only in the binary classification task, where all models showed similar reasoning ability when responding to basic and direct stability questions.

5. Additional Analysis

To gain deeper insight into the reasoning patterns observed in the main results, this section presents a finer-grained analysis of performance at the subtask level. By examining the models’ responses in detail, we aim to uncover patterns that may not be evident in overall accuracy metrics, including strengths, weaknesses, and subtle differences in how tasks are approached. This analysis complements the previous Results and Discussion Section by providing a more nuanced understanding of stability reasoning across tasks and subtasks.

5.1. Subtask-Level Analysis

This subsection explores the performance of MLLMs on individual subtasks within each main task category. By analyzing these subtasks, we identify specific areas where models succeed or fail. This provides insight into how parameter scale and visual reasoning capabilities influence performance on fine-grained physical reasoning problems.

Table 5 shows performance across different modality inputs (image, JSON, and XML) and varying levels of choice complexity (two, three, or four options). Across all models, the setting with two options yielded the highest accuracy, while performance steadily decreased as the number of options increased. This trend mirrors findings from the previous work [7] with smaller-parameter models, reinforcing the interpretation that increased complexity or longer context reduces the models’ ability to perform reliable physical reasoning task.

Table 5.

Comparison task (Task 2) accuracy of open-weight models across modalities and varying numbers of options.

Within this broader trend, the Qwen2.5-VL series displayed distinctive behavior across tasks and modalities. In Task 2, Qwen2.5-VL models performed best with the image modality under the two-option setting, reaching scores of 0.62 for Qwen2.5-VL-72B and 0.57 for Qwen2.5-VL-32B. However, in Task 3, the same series achieved notably higher accuracy with the XML modality, suggesting that symbolic input formats may provide an advantage for prediction tasks. Another highlight comes from the four-option setting. While Qwen2.5-VL models struggled with four-option multiple-choice questions in Task 2, they showed competitive results in Task 3 with the same number of options. This apparent contradiction suggests that Qwen models are particularly adept at prediction-style reasoning but remain sensitive to context complexity in comparison-style tasks.

In contrast, models from the Gemma3 and LLaVA families demonstrated more consistent performance across modalities and option settings. While their scores were generally lower than Qwen2.5-VL on certain subtasks, this stability may reflect a different balance between visual and symbolic reasoning strategies. Overall, these results suggest that, while all models face challenges as task complexity increases, they adopt different pathways for handling modality and option variations.

Extending the analysis from the comparison task, Table 6 presents the models’ performance on the prediction task, providing further evidence of the uneven strengths of MLLMs across modalities and task types. A notable weakness is observed in LLaVA-32B, which records the lowest accuracy in the JSON modality. Its performance falls below 0.1 despite having a larger parameter count than LLaVA-13B. Interestingly, the smaller variant of LLaVA achieves more balanced results across all modalities. This finding suggests that scaling alone does not guarantee improved reasoning ability, particularly when certain data types are underrepresented in training. This highlights the importance of both architectural scaling and training data diversity, echoing recent observations in multimodal benchmark studies where training coverage plays a decisive role in performance consistency.

Table 6.

Prediction task (Task 3) accuracy of open-weight models across modalities and subtasks.

In contrast, Qwen2.5-VL demonstrates a clear advantage in handling structured XML input, with accuracy rising markedly as parameter size increases. The 32B variant already achieves a mean accuracy of 0.80 in XML, while the 72B version reaches 0.89, which not only surpasses other models in this evaluation but also exceeds the GPT-4o and GPT-4.1 mini results reported in our earlier study. This strong performance in XML is particularly significant given that the format requires integrating both structural understanding and reasoning over symbolic content, reinforcing prior findings that Qwen2.5-VL is more adept in text-rich modalities. Moreover, the progressive gains across the 32B and 72B models suggest that parameter scaling contributes directly to more sophisticated handling of physically grounded tasks in structured representations.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that current MLLMs are not uniformly competent across modalities. JSON remains a persistent weakness for some architectures, whereas XML emerges as a relative strength for models such as Qwen2.5-VL. This divergence indicates that advancing the field of physical reasoning with MLLMs requires not only scaling model capacity but also refining modality-specific training strategies. In particular, the strong results of Qwen2.5-VL in structured tasks provide a compelling case for further research on how model design and training can bridge the gap between perceptual input and symbolic reasoning, a challenge that remains central to developing models with deeper physical understanding.

5.2. Error Analysis of Model Failures

An invalid response is defined as a failure in the answer extraction process, indicating that the model could not produce a parsable or meaningful output for evaluation. We standardized the output format to a JSON structure: {“Reason”: “string”, “Answer”: “string”}. This format facilitates straightforward parsing and evaluation of both the reasoning process and the final answer. Any deviation from this structure, such as malformed syntax, incomplete outputs, repetitive tokens, or answers outside the provided options, was classified as invalid.

To better understand these failures, we conducted a qualitative analysis of LLaVA-34B outputs, as this model produced the largest number of invalid responses. We manually checked ten randomly selected cases and found three recurring error types across Task 2 and Task 3. The first type was syntax errors, where the output was malformed, empty, or unrelated to the Angry Birds task. The second type was repetition loops, where the model produced tokens or phrases repeatedly without termination. The third type was trivial or collapsed outputs, where the response remained related to Angry Birds but contained only minimal reasoning or provided an answer outside the available options.

Table 7 presents the observed error types along with representative outputs. The results show that invalid responses were not random noise, but indicated limitations in the model’s ability to consistently produce well-formed and meaningful structured outputs. In the case of LLaVA-34B, several invalid outputs appeared when the model was required to follow the standardized output schema, leading to repetitive, malformed, or semantically uninformative results instead of coherent reasoning. These findings suggest that such errors may arise from difficulties in adapting to structured output requirements or from other alignment limitations, rather than from issues with the evaluation format itself.

Table 7.

Taxonomy of invalid response types observed in LLaVA-34B (JSON modality). Examples are drawn from sampled outputs in Task 2 and Task 3.

6. Limitation

Although this extended study aimed to enhance generalizability compared to the initial work, several constraints remain. The selection of models was deliberately limited to families used in the previous work [7], ensuring consistency in comparison but narrowing the scope of analysis. This restriction may limit the generalizability of our findings in this study, as models outside these families could display different reasoning patterns. A broader pooling of models across architectures and training approaches would provide a more comprehensive perspective.

Resource limitations also played an important role in shaping the scope of our investigation. While larger-parameter models were included to extend the previous work, the maximum scale reached was 72B parameters using Q4 quantization. This setting provided valuable insight into scaling behavior but does not fully capture the performance of uncompressed high-capacity models. Consequently, conclusions about scaling trends must be interpreted with caution, as they may not hold when considering models with higher precision or even larger parameter counts.

Finally, the human evaluation and prompting strategies introduce additional limitations. The number of human participants was relatively small, which restricts the statistical power of comparisons. Moreover, the human results were used as a descriptive performance reference rather than a cognitive analysis. The comparison was designed to contextualize achievable task accuracy under identical visual conditions without inferring underlying reasoning or perceptual mechanisms. As such, differences between human and model performance should be interpreted as empirical capability gaps, not as evidence of distinct cognitive strategies. Future research could expand the participant pool, incorporate targeted behavioral analyses, and explore optimized prompting or fine-tuning approaches to gain a more comprehensive understanding of multimodal physical reasoning.

7. Conclusions

This study presents an extended investigation of physical reasoning in MLLMs, building upon our previous work. By including additional models and comparing their performance with human participants, this extended version provides a broader perspective on model capabilities. Compared to the original study, we observed both continuity and new insights. Although GPT models maintained high overall scores, human participants consistently outperformed all models across tasks, highlighting the limitations of current MLLMs in physical reasoning.

Across all tasks, GPT-4o demonstrated strong performance in the image modality, showing robust reasoning capabilities in both comparison and prediction subtasks. The Qwen2.5-VL series also performed competitively with commercial models, achieving the highest scores in this extended study for certain tasks. Using simpler tasks, such as Task 1, all models showed balanced performance across modalities, suggesting that MLLMs have the potential to grasp fundamental aspects of physical reasoning. Some surprising results emerged as well; for Task 3 under the XML modality, Qwen2.5-VL models outperformed GPT variants from the previous study, indicating that structured inputs can enhance reasoning outcomes.

These findings suggest that more advanced prompting strategies or tasks designed to closely engage reasoning approaches may further unlock the capabilities of MLLMs. Expanding the human participant pool would also provide a more robust benchmark and contribute valuable insights into the comparative evaluation of models. Overall, this study highlights the strengths and limitations of current MLLMs while pointing to promising directions for future research in understanding physical reasoning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.D., F.A. and R.T.; methodology, M.F.D., F.A. and R.T.; software, M.F.D. and F.A.; validation, F.A., I.K. and Y.X.; formal analysis, M.F.D.; investigation, M.F.D.; resources, W.O., F.A. and R.T.; data curation, M.F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.D.; writing—review and editing, M.F.D., F.A., Y.X., I.K., M.F.D., W.O., R.T. and F.A.B.; visualization, M.F.D.; supervision, R.T.; project administration, M.F.D.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ritsumeikan University does not require approval for this kind of nonmedical research. We consulted with the Research Ethics Review Committee Executive Office before conducting similar studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets, source code, experimental scripts, and example questions used in the user study are openly available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/kuralemot/game-physics-eval. (accessed on 11 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Grammarly (Chrome Extension) version 14.1253.0 and Chat GPT-5 for the purposes of grammar correction and language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| JSON | Java Script Object Notation |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| MLLMs | Multimodal Large Language Models |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

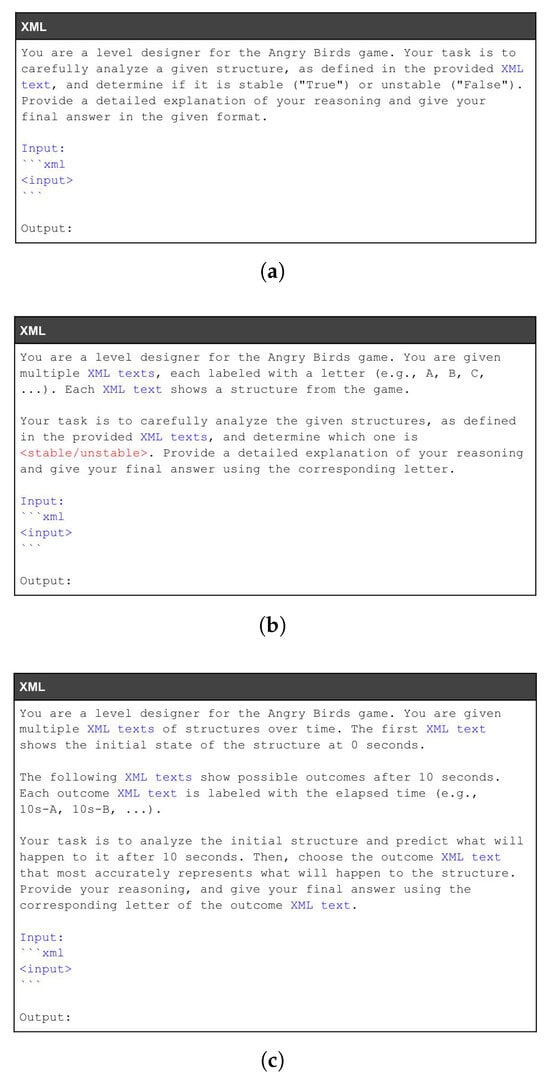

Appendix A

To improve transparency and replicability, we provide representative prompt examples for each task in the XML modality, shown in Figure A1. These samples illustrate the exact input format shown to the models during evaluation. For brevity, only XML prompts are included here; the JSON and image modalities followed the same task-specific framing, differing only in input format.

Figure A1.

Representative sample prompts for the three evaluation tasks (binary (a), comparison (b), and prediction (c)) in the XML modality. These examples illustrate the input format shown to the models.

References

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Tang, J.; Zhong, H.; et al. Qwen2. 5-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, A.; Ferret, J.; Pathak, S.; Vieillard, N.; Merhej, R.; Perrin, S.; Matejovicova, T.; Ramé, A.; Rivière, M.; Rouillard, L.; et al. Gemma 3 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.19786v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 26296–26306. [Google Scholar]

- Jassim, S.; Holubar, M.; Richter, A.; Wolff, C.; Ohmer, X.; Bruni, E. Grasp: A novel benchmark for evaluating language grounding and situated physics understanding in multimodal language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.09048. [Google Scholar]

- Voudouris, K.; Donnelly, N.; Rutar, D.; Burnell, R.; Burden, J.; Hernández-Orallo, J.; Cheke, L.G. Evaluating object permanence in embodied agents using the Animal-AI environment. In Proceedings of the EBeM’22: Workshop on AI Evaluation Beyond Metrics, Vienna, Austria, 25 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dewantoro, M.F.; Abdullah, F.; Xia, Y.; Khan, I.; Thawonmas, R.; Ouyang, W. Can Multimodal LLMs Reason About Stability? An Exploratory Study with Insights from the LLMs4PCG Challenge. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG), Lisboa, Portugal, 26–29 August 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, M.; Wang, H. MAPS: Advancing Multi-Modal Reasoning in Expert-Level Physical Science. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze Buschoff, L.M.; Akata, E.; Bethge, M.; Schulz, E. Visual cognition in multimodal large language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; Bosma, M.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; et al. Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.07682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, A.; Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Bodapati, S.B.; Roth, D. ConSiDERS-The-Human Evaluation Framework: Rethinking Human Evaluation for Generative Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 1137–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, M.; Chen, B.; Eghbalzadeh, H.; Nagarajan, T.; Desai, R. User-in-the-Loop Evaluation of Multimodal LLMs for Activity Assistance. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, P.; Wan, Y.; Sun, L. MLLM-as-a-Judge: Assessing Multimodal LLM-as-a-Judge with Vision-Language Benchmark. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, G.; Cresswell, J.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Sui, Y.; Ross, B.; Villecroze, V.; Liu, Z.; Caterini, A.L.; Taylor, E.; Loaiza-Ganem, G. Exposing flaws of generative model evaluation metrics and their unfair treatment of diffusion models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 3732–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, D.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J. Self-Bootstrapped Visual-Language Model for Knowledge Selection and Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 1857–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yu, W.; Sun, G.; Chen, X.; Tan, T.; Li, W.; Lu, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, C. Extending Large Language Models for Speech and Audio Captioning. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 11236–11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Do, C.T.; Keizer, S.; Farag, Y.; Stoyanchev, S.; Doddipatla, R. WHISMA: A Speech-LLM to Perform Zero-Shot Spoken Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Macao, China, 2–5 December 2024; pp. 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Dou, J.; Ni, Z.; Guan, H. Lightweight Design of Robotic Arm Based on Multimodal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR), Hangzhou, China, 16–18 May 2025; pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lu, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, Q.; Han, S.; Finn, C.; et al. CoT-VLA: Visual Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Vision-Language-Action Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Mishra, S.; Xia, T.; Qiu, L.; Chang, K.W.; Zhu, S.C.; Tafjord, O.; Clark, P.; Kalyan, A. Learn to explain: Multimodal reasoning via thought chains for science question answering. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 35, pp. 2507–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.; Narayanan, A.; Khazaie, V.R.; Vayani, A.; Chettiar, M.S.; Singh, A.; Shah, M.; Pandya, D. Humanibench: A human-centric framework for large multimodal models evaluation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11454. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, F.; Paliyawan, P.; Thawonmas, R.; Harada, T.; Bachtiar, F.A. An Angry Birds Level Generator with Rube Goldberg Machine Mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG), London, UK, 20–23 August 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveekitworachai, P.; Abdullah, F.; Thawonmas, R. Null-Shot Prompting: Rethinking Prompting Large Language Models With Hallucination. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 13321–13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain of Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November 2022–9 December 2022; Oh, A.H., Agarwal, A., Belgrave, D., Cho, K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, A.; van der Maaten, L.; Johnson, J.; Gustafson, L.; Girshick, R. PHYRE: A New Benchmark for Physical Reasoning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wu, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y. I-PHYRE: Interactive Physical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).