Abstract

Marine risers are susceptible to vortex-induced vibrations (VIV) in complex ocean current environments, posing significant risks to structural safety and fatigue life. This study, conducted on the Ansys Workbench platform, establishes a three-dimensional numerical model using bidirectional fluid–structure interaction (FSI) methods. Wet modal analysis is employed to extract the riser’s natural frequencies, followed by a systematic comparison of vibration responses under uniform flow and linear shear flow conditions. The findings indicate that as the vortex shedding frequency approaches the structural natural frequency, the system exhibits pronounced frequency lock-in. Spectral analysis confirms that VIV dominates the dynamic response. Notably, under initial conditions (uniform flow velocity = 0.5 m/s; shear flow velocity = 0.05 m/s, Gradient = 0.025), shear flow induces larger vibration amplitudes. However, as flow velocity increases, uniform flow surpasses shear flow in both amplitude (maximum 0.03 D) and frequency (maximum 0.02 D). Modal analysis demonstrates that uniform flow excites the fourth-order mode, whereas shear flow confines the system in the second-order mode. Additional controlled simulations highlight the critical influence of the shear flow’s initial velocity on vibration modes, providing a theoretical basis for VIV suppression.

1. Introduction

Marine risers are susceptible to displacement and vortex-induced vibration (VIV) under complex flow conditions, particularly when the vortex shedding frequency approaches the structure’s natural frequency. This phenomenon leads to frequency lock-in and subsequent fatigue failure. These challenges are exacerbated by increasing length-to-diameter ratios. Investigating VIV mechanisms remains crucial for offshore engineering safety and involves experimental, numerical, and theoretical approaches. While physical experiments face significant cost and technical limitations, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a pivotal research tool due to its cost-effectiveness and efficiency, providing critical insights that optimize experimental design.

The study of vortex-induced vibrations (VIV) has evolved substantially since Sarpkaya’s seminal 1979 review, which established the foundational understanding of vortex-induced oscillations [1]. Early theoretical frameworks by Griffin and Ramberg systematically characterized vortex street formation behind vibrating cylinders [2], while Bearman’s research elucidated fundamental vortex shedding mechanisms from oscillating bluff bodies [3]. These pioneering investigations laid the essential groundwork for contemporary VIV research.

Recent decades have witnessed significant methodological advancements in vortex-induced vibration (VIV) research. Wu et al. [4] (2012) and Wang et al. [5] (2013) focused specifically on marine risers, highlighting the growing importance of offshore energy applications. Bearman’s updated analysis of cylinder wakes [6] (2014)and Liu et al.’s critical examination of VIV fundamentals demonstrated ongoing theoretical refinement in the field [7] (2015). The emergence of specialized reviews by Hong [8] (2016) and Shah on flexible structures, along with Williamson’s focused examination of key VIV issues, marked increasing research sophistication [9] (2016). Contemporary reviews highlight several important trends in vortex-induced vibration (VIV) research. Jaiman et al. [10] (2016) and Swithenbank et al. [11] (2017) emphasized the integration of numerical and experimental approaches, while Gao et al. [12] (2018) provided a comprehensive assessment of circular cylinder VIV across multiple disciplines. The growing complexity of engineering systems is evident in Chen et al.’s [13] (2019) examination of long flexible cylinders and Wang et al.’s focus on marine riser applications [14] (2020). Most recently, the field has embraced innovative computational approaches, as documented in Wang et al.’s [15] (2021) review of machine learning applications and Fan et al.’s examination of data-driven modeling techniques [16] (2022). Practical engineering considerations are highlighted in Li and Wan’s [17] (2023) state-of-the-art review of VIV suppression methods, demonstrating the field’s progression from fundamental research to applied solutions.

Over the past decade, experimental research has made significant progress in characterizing vortex-induced vibrations (VIVs) under complex flow conditions. Wang et al. [18] (2018) systematically revealed the multi-mode vibration mechanisms of long flexible risers through sophisticated stepped shear flow experiments, establishing a benchmark for complex flow–structure interaction analysis. Guan et al. [19] (2019) pioneered the investigation of buoyancy modules’ influence on riser dynamics, providing crucial design insights for practical engineering applications. Notably, Zhou’s team [20] (2021) achieved a breakthrough by quantitatively demonstrating the enhancement effect of surface roughness on VIV response, a finding with direct implications for deep-sea riser design. Compared to these studies, the present research introduces a novel approach by systematically comparing the modal behavior under uniform and shear flow modal behavior, addressing a critical gap in the experimental literature.

The advancement of three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics has enabled unprecedented exploration of complex physical mechanisms. Chen and Xiao [21] (2020) elucidated the spatiotemporal evolution of vortex shedding in shear flow through comprehensive two-way fluid–structure interaction simulations. Bai et al. [22] (2022) successfully captured detailed vortex structures in riser wakes using large eddy simulation, providing new insights into vortex–structure interactions. Kim’s team [23] (2023) developed an innovative multi-scale coupling algorithm that effectively addresses the critical challenge of balancing computational efficiency and accuracy in deep-water riser simulations. The present advances build upon computational approaches by implementing a bidirectional FSI within the ANSYS (2023b) Workbench platform, demonstrating superior capability in capturing modal transition phenomena that previous simulations have inadequately addressed.

The emergence of data-driven methods has revolutionized traditional research methodologies. Mao et al. [24] (2020) pioneered the application of deep learning to vortex-induced vibration (VIV) prediction through their modal decomposition-based data-driven model, as published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics. Subsequently, Li et al. [25] (2022) significantly improved prediction accuracy under unsteady flow conditions by developing a hybrid machine learning framework. While these data-driven approaches demonstrate predictive capabilities, our research complements these advancements by providing high-fidelity numerical data essential for training and validating such machine learning models, particularly for under shear flow conditions.

In vibration suppression technology, continuous efforts have focused on developing and optimizing novel suppression devices. Song et al. [26] (2021) established quantitative relationships between the geometric parameters of helical strakes and suppression efficiency through systematic numerical studies. Zhang’s team [27] (2023) demonstrated the potential application of smart materials in flow control via their adaptive fairing concept. The present study extends these suppression studies by providing fundamental insights into flow–structure interaction mechanisms, which are essential for the optimal design of suppression devices for varying flow conditions.

Recent investigations continue to advance the field. Song and Zhang [28] (2025) conducted experimental studies on concave-to-convex fairings, confirming that increased convex geometric dominance progressively enhances vortex-induced vibration (VIV) suppression. Deng and Lu [29] examined VIV in deep-sea mining risers at depths of 6000 m with nonlinear tension, demonstrating effective control strategies that reduced drift distance by over 35% under specific conditions. Despite these advancements, a significant research gap remains in the comparison of uniform versus shear flow effects on modal behavior, particularly regarding the influence of velocity and shear velocity gradient—an issue that the study directly addresses.

Looking ahead, research on vortex-induced vibrations (VIV) is trending toward interdisciplinary integration. Jaiman et al. [30] (2024) proposed a digital twin framework, representing a novel approach for real-time monitoring and intelligent prediction. However, understanding the vibration characteristics of riser arrays under extreme marine environments and multi-physical field coupling remains a significant scientific challenge that requires future breakthroughs.

This research makes a distinctive contribution by developing a three-dimensional numerical model that employs bidirectional fluid–structure interaction to systematically investigate vortex-induced vibration (VIV) characteristics under uniform and linear shear flows. Through integrated wet modal analysis and comprehensive time–frequency vibration analyses, we elucidate critical phenomena, including frequency locking, spatial mode evolution, and the specific effects of flow parameters on vibration behavior. Our approach offers advantages over established methods by providing unprecedented insights into modal transition mechanisms and delivering a robust theoretical and numerical foundation for fatigue life assessment and VIV suppression design in marine risers. This effectively addresses limitations in the current literature regarding systematic comparisons across flow regimes.

2. Numerical Models and Methods

2.1. Governing Equations

(1) Fluid Domain Governing Equations

For incompressible viscous flow problems, the continuity equation and the Navier–Stokes equations governing incompressible viscous fluid flow can be expressed in Cartesian coordinates as follows:

where and represent the coordinates in three orthogonal directions, and and denote the velocity vector components in the and directions, respectively. Here, indicates the pressure field, stands for the fluid density, and represents the dynamic viscosity coefficient of the fluid. The form of this equation follows that illustrated by Versteeg et al. [31] (2007)

(2) Governing Equations for Solid Domain

In structural dynamic analysis, the finite element formulation derived from the principle of virtual work is employed for spatial discretization of the governing equations. This method is consistent with the methodology documented in the ANSYS Mechanical APDL Theory Reference [32]. The dynamic equation for the riser structure can be discretized as

where represents the mass matrix of the structural system; denotes the damping matrix; is the stiffness matrix; and , and represent the nodal displacement, velocity, and acceleration vectors in the in-line (stream wise) and cross-flow directions, respectively. and denote the hydrodynamic forces acting on the riser in the in-line and cross-flow directions.

(3) Coupled Governing Equations

In fluid–structure interaction (FSI) analysis, data exchange between fluid and solid domains primarily occurs at their shared interface. This necessitates strict enforcement of physical continuity across the boundary. Hou and Wang [33] provide a comprehensive description of the numerical methodologies and theoretical foundations underlying fluid–structure interaction (FSI) in their seminal work. For marine risers, the coupling interface between the structural surface and surrounding fluid must satisfy two fundamental constraints:

where is the Cauchy stress tensor, denotes the unit normal vector on the boundary, and the subscripts and refer to the fluid domain and solid domain, respectively. This equation enforces force equilibrium across the interface. Meanwhile, represents the displacement vector.

2.2. Turbulence Modeling

For incompressible flow simulations, the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes approach has been widely adopted in vortex-induced vibration (VIV) studies. The methodology—a cornerstone of engineering turbulence modeling—operates by solving time-averaged governing equations to predict flow characteristics, achieving an optimal balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. Based on the current computing conditions, this study adopts the Shear Stress Transport k-omega model under the framework. The model, developed by Menter [34], integrates the advantages of both the and models. By leveraging the robustness of the formulation in near-wall regions, it significantly improves the accuracy and reliability of numerical predictions close to the wall. The main governing equations of this model are as follows:

In the formula, represents the Reynolds stress term, which indicates the turbulent effect and is usually denoted by . This is an unknown quantity in a equation. Based on the Boussinesq eddy viscosity assumption, this model relates the Reynolds stresses to the mean velocity gradients [35]. To make the entire equation closed, a turbulence model needs to be used for processing, namely,

In the equation, represents the dynamic viscosity, represents the turbulent kinetic energy, and it is assumed to be isotropic. Therefore, the following equation holds:

Among them, the effective pressure , and the effective viscosity , . Using the SST model, is obtained, and the RNAS equation is closed. The transport equation of turbulent kinetic energy is

In the formula, denotes its transient term, is the convection term, stands for the production term, corresponds to the dissipation term, and describes the diffusion term. is the turbulent Prandtl number for the k-equation.

The transport equation for the dissipation rate is as follows:

where denotes the transient term, represents the convection term, corresponds to the production term, is the dissipation term, describes the diffusion term, and constitutes the cross-diffusion term. is the turbulent Prandtl number for the equation.

To close the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, the Shear Stress Transport turbulence model, originally developed by Menter [36], is adopted in this study. The selection and implementation of this model are consistent with the standard settings in the ANSYS Fluent solver [37]. The model combines the advantages of the standard model in near-wall regions and the model in the far field, employing a blending function to ensure a smooth transition between these regimes.

2.3. Numerical Validation

Based on the ANSYS Workbench platform, a bidirectional fluid–structure interaction (FSI) simulation of a riser interacting with internal and external flow fields is implemented by integrating three core components: Fluent (for computational fluid dynamics), Transient Structural (for structural dynamics), and System Coupling (for data exchange and co-simulation). Within Fluent, vortex shedding patterns and pressure nephogram animations are examined to observe the generation, development, and shedding processes of vortices. In Transient Structural, displacements at key points of the riser are extracted and subjected to a Fourier transform to identify the dominant frequencies of vibration.

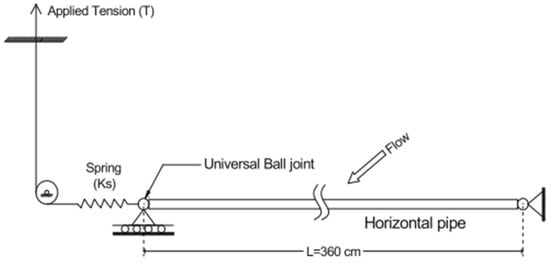

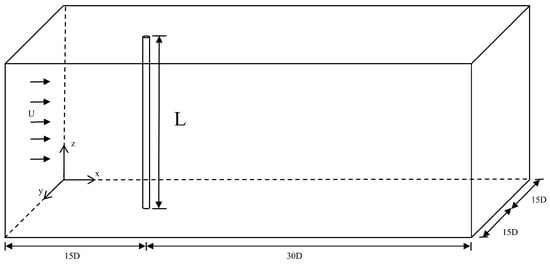

To rigorously evaluate the accuracy of our numerical model and the validity of the boundary condition implementation, we conducted benchmark simulations of flexible riser vortex-induced vibrations (VIV) replicating the experimental conditions described by Sanaati and Kato (2014) [38]. The computational domain precisely matches the experimental geometry (Figure 1 and Figure 2), with key parameters maintained as follows:

Figure 1.

Experimental geometry.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the 3D riser computational model.

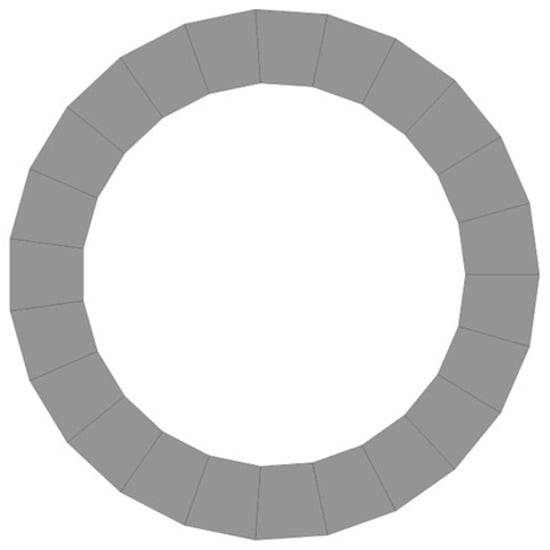

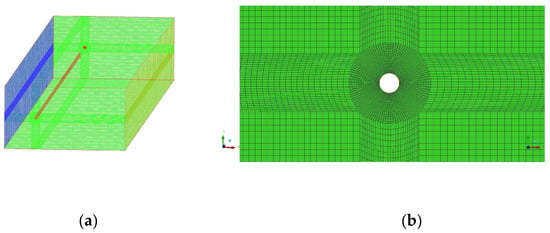

In the present simulations, turbulence is modeled using the SST formulation. The riser mesh is generated with the built-in transient analysis meshing tool. The riser was discretized with 200 layers of elements along its axis, with each layer further partitioned using surface elements; Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the riser mesh. For the external flow field, the ICEM module was employed to generate a mesh comprising approximately 5.3 million elements. Grid refinement was applied in the vicinity of the riser–fluid interface, featuring 120 elements per layer around the riser. The element size was set to 3.8 × 10−4 m in the regions adjacent to the riser and gradually increased in the far-field. The computational domain for the external flow field comprises approximately 5.3 million grid elements. Figure 4a shows the overall mesh of the external flow field, and Figure 4b shows the near-wall mesh. During the coupled simulation, the convergence criterion was set to a residual tolerance of 1 × 10−5 to ensure higher solution accuracy. The analysis was conducted with a time step size of 0.005 s over a total physical time of 50 s in the System Coupling module.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional view of the riser mesh.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the external flow field mesh: (a) schematic of the overall mesh configuration; (b) schematic of the near-wall mesh resolution.

Mesh motion is accommodated through a diffusion-based smoothing algorithm. The riser’s outer surface is designated as a fluid–structure interface, and simply supported boundary conditions are applied at both ends. The riser is modeled with pin connections at both ends. At the lower end, all translational degrees of freedom (x, y, z) are constrained, while rotations about the x- and y-axes are released, and rotation about the z-axis is restrained. At the upper end, translations in the x- and y-directions are constrained, and the z-direction is free.

The numerical predictions are benchmarked against existing experimental and computational data reported in the literature. The model is subjected to a uniform current; the riser aspect ratio is 200, and a top tension of 60 N is imposed. Further details of the validation case are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Calculation of the boundary conditions of the model.

As shown in Table 1, the mass ratio (m*) is defined as the ratio of the structural mass to the mass of the fluid it displaces.

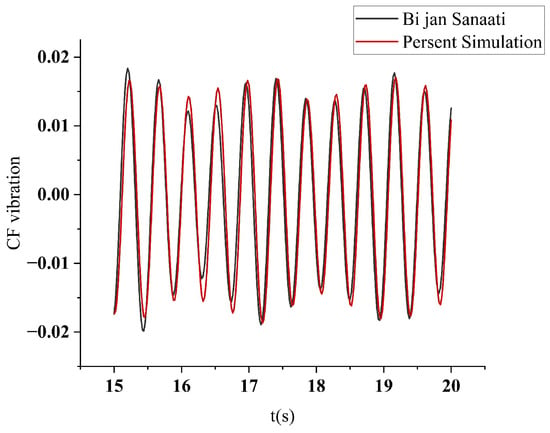

Figure 5 compares the predicted cross-flow vibration amplitude with the experimental measurements outlined by Sannaati and Kato [31]; the numerical response closely matches the experimental envelope, which is in excellent agreement with the experimental value reported by Sannaati.

Figure 5.

Transverse displacement response time–history curve.

3. Results and Discussion

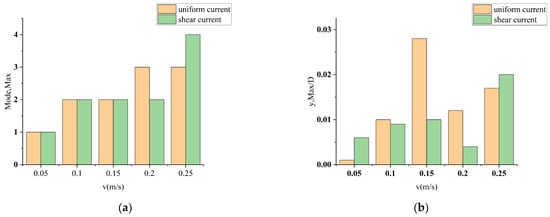

A quantitative analysis was conducted to characterize the vibration response and modal evolution of a flexible riser in both uniform and sheared currents. The computational study included ten environmental cases: five uniform-current scenarios (0.05 m/s to 0.25 m/s) and five shear-current scenarios (0.14 m/s to 0.51 m/s, with a base velocity of 0.05 m/s). Shear gradients of 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, and 0.10 s−1 were applied, along with one shear-free control case. Table 2 presents detailed profiles of the incoming flow velocity under both uniform and shear flow conditions.

Table 2.

The initial and final velocities with their respective velocity ranges under varying flow conditions.

3.1. Natural Frequencies and Mode Shapes

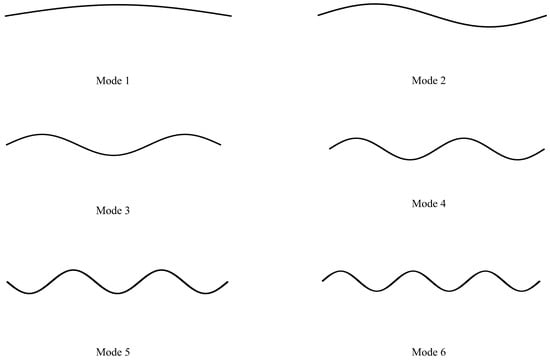

The wet modes of the riser were extracted using the Modal Acoustics solver in ANSYS. The first six natural frequencies and their corresponding mode shapes are listed in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 6. When the vortex-shedding frequency approaches any of these eigenfrequencies, a resonant response is triggered; therefore, characterizing the modal properties of the riser is essential.

Table 3.

The first 6th-order natural frequencies of the riser.

Figure 6.

The first six intrinsic mode shapes of the riser.

3.2. Vortex-Induced Vibration Characteristics of a Flexible Riser in Uniform Flow

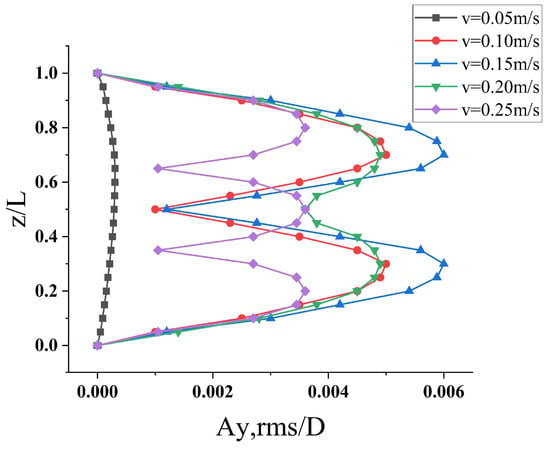

3.2.1. Envelopes of Vibration Amplitude

Figure 7 presents the spanwise distribution of the non-dimensional cross-flow root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude for the riser under increasing uniform current speeds. ( denotes the root-mean-square of the normalized cross-flow riser amplitude). The modal order increases sequentially with flow velocity, exciting up to the third mode within the studied range. At 0.05 m/s, the motion is predominantly first-mode, with occasional second-mode participation and a peak RMS amplitude at mid-span (z/L = 0.5, where z/L is a dimensionless quantity representing the normalized position along the riser’s length). At intermediate speeds, the response adopts the second mode, exhibiting maxima at z/L ≈ 0.3 and 0.7. When the current reaches 0.20 m/s, a transition from the second to the third mode is observed, with peak amplitudes again at z/L ≈ 0.3 and 0.7. Further increasing the velocity to 0.25 m/s amplifies the RMS levels and drives the system toward a third-to-fourth-mode transition, yielding three distinct maxima at z/L ≈ 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8.

Figure 7.

Cross-flow RMS amplitude at different uniform current velocities.

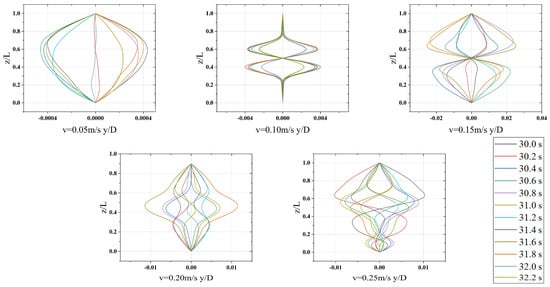

Figure 8 presents the cross-flow vibration envelopes of the riser under uniform current conditions, with colored traces representing instantaneous deflections at successive time points. (The time instances are 30 s and 32.2 s, respectively, with an interval of 0.2 s; note that ‘s’ is the abbreviation for seconds). The envelopes confirm the dominant modal responses identified in Figure 7; however, the patterns at 0.05, 0.20, and 0.25 m/s are noticeably less coherent, indicating multi-modal interactions. Specifically, the response at 0.05 m/s spans the first and second modes, the response at 0.20 m/s lies between the second and third modes, and the response at 0.25 m/s corresponds to a transition between the third and fourth modes. (y/D is a dimensionless parameter representing the displacement of the pipeline normalized by its outer diameter).

Figure 8.

Cross–flow structural response envelopes of riser under uniform current.

3.2.2. Vibration Response Analysis

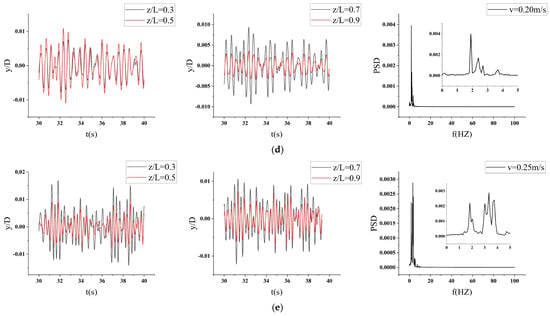

Figure 9 presents the cross-flow displacement time histories and their dominant frequency spectra under uniform currents. Fast Fourier transforms (FFT) of the lateral displacement signals were employed to identify the dominant modes.

Figure 9.

Cross-flow displacement time–history curve under uniform current. (a) = 0.05 m/s; (b) = 0.10 m/s; (c) = 0.15 m/s; (d) = 0.20 m/s; (e) = 0.25 m/s.

At a velocity of 0.05 m/s, the dominant frequency is 1.09 Hz—slightly above the first wet natural frequency (Table 3)—indicating a first-mode response.

For a velocity of 0.10 m/s, the peak at 1.69 Hz exceeds the second natural frequency, confirming a second-mode response.

At 0.15 m/s, the frequency remains close to the second natural frequency, once again indicating a motion dominated by the second mode.

When increased to 0.20 m/s, the spectrum peaks at 2.40 Hz, which lies between the second and third natural frequencies. Consequently, the envelope exhibits a mixed second–third mode pattern. However, the frequency’s proximity to the second mode implies that the second mode remains dominant.

Finally, at a velocity of 0.25 m/s, the dominant frequency is 3.80 Hz, which lies between the third and fourth natural frequencies but is closest to the third; therefore, the response is governed by the third mode. Table 4 presents the vibration frequencies obtained through Fast Fourier Transform analysis of the cross-flow amplitude under different flow velocities.

Table 4.

Dominant frequency for different uniform current velocities.

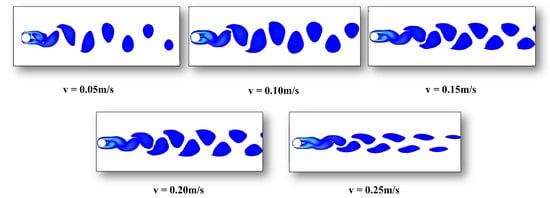

3.2.3. Influence of Uniform Flow Velocity on Vortex Shedding Patterns

The vortex shedding pattern behind the riser undergoes a systematic transition as the uniform flow velocity increases from 0.05 m/s to 0.25 m/s. At the lowest velocity (0.05 m/s), the wake is characterized by weak vortex shedding intensity and a diffuse structure, exhibiting a non-canonical or faint P + S mode. As the velocity rises to the intermediate range (0.10–0.15 m/s), the wake becomes more organized, showing a tendency for vortex pairing, which indicates a transitional state from the 2S to the 2P mode. At higher velocities (0.20–0.25 m/s), a stable and symmetric Kármán vortex street is established, corresponding to the classical 2S shedding mode. Figure 10 illustrates the vortex shedding phenomena around a riser under uniform flow conditions with increasing incoming flow velocity.

Figure 10.

Vortex shedding patterns of a riser under uniform flow conditions.

This evolutionary sequence underscores the governing role of flow velocity on the vortex dynamics: insufficient energy at low Reynolds numbers leads to an unstable wake structure, enhanced vortex interactions at moderate velocities trigger a mode transition, and adequate energy at elevated Reynolds numbers sustains periodic and symmetric vortex shedding. These findings provide crucial insight into the underlying flow mechanisms responsible for the vortex-induced vibration response of risers across different flow regimes. (The images selected in this section and Section 3.3.3 are all taken at the position of z/L = 0.5) The Strouhal numbers for various operating conditions, determined by applying Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis to the lift coefficient signals following the extraction of vortex-shedding frequencies, are presented in Table 5. The calculated Strouhal numbers fluctuate within the range of 0.19–0.21, with a mean value of 0.20. This statistical characteristic holds significant physical implications. First, the results show strong agreement with the classical Strouhal number (≈0.2) for subcritical Reynolds number flow around a circular cylinder, thereby validating both the accuracy of the numerical model and its applicability to vortex-induced vibration (VIV) analysis of marine risers [39].

Table 5.

Strouhal number in uniform flow conditions.

In the equation [40], represents the vortex shedding frequency (unit: Hz), denotes the characteristic length (unit: m), and refers to the incoming flow velocity (unit: m/s).

3.3. Vortex-Induced Vibration Characteristics of Flexible Risers Under Shear Flow

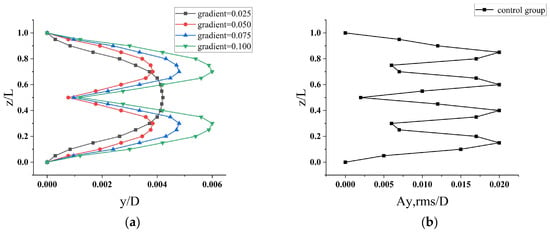

3.3.1. Envelopes of Vibration Amplitude

Figure 11a presents the cross-flow dimensionless root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude distribution along the riser length under shear flow. At a fixed initial velocity, as the shear flow velocity gradient T increases (0.025 to 0.1), the vibration amplitude grows in all directions. When T = 0.025, the riser predominantly exhibits the first-mode response, with occasional second-mode contributions. Amplitude occurs at z/L = 0.5, confirming the dominance of the first mode. For T = 0.05, 0.075, and 0.1, however, the second mode becomes dominant, with the cross-flow vibration peaking at the second-order modal shape.

Figure 11.

Cross-flow RMS amplitude under shear current: (a) cross-flow RMS amplitude under shear current; (b) control group cross-flow RMS amplitude under shear current.

This raises a key question regarding the vibration characteristics under shear flow: is the modal response strongly correlated with the initial velocity? To investigate this, a control group with increased velocity while maintaining the shear gradient was established. The results shown in Figure 11b reveal the interplay between the mode, initial velocity, and gradient.

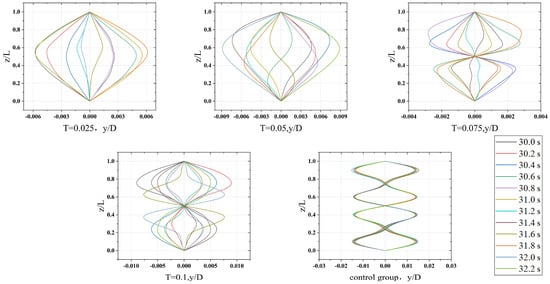

Figure 12 compares the influence of shear-flow velocity gradients (T) on the cross-flow modal envelopes of the riser. Colored traces denote deformations at different time steps. For lower gradients (T = 0.025 and 0.05), envelopes exhibit a disordered, multimodal state indicating a transition between first- and second-mode dominance. At higher gradients (T = 0.075 and 0.1), the response transitions to a distinct second mode.

Figure 12.

Cross–flow structural response envelopes of riser under shear current.

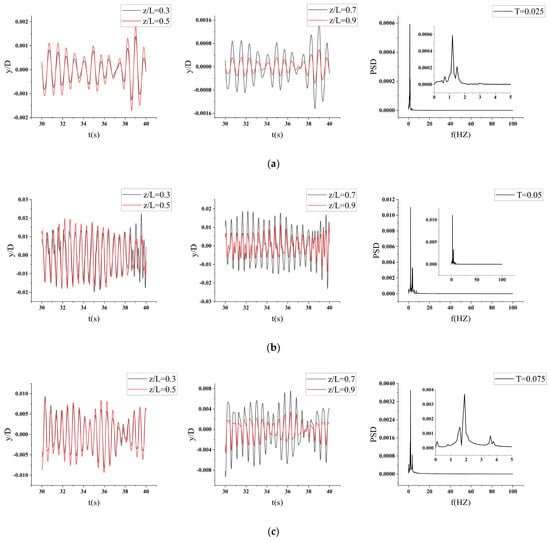

3.3.2. Vibration Response Analysis

Figure 13 presents the cross-flow displacement time–history curves and dominant frequency spectra under shear flow. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis of the displacement time series reveals the governing vibration modes. At T = 0.025, the dominant frequency of 1.10 Hz exceeds but remains close to the first-order natural frequency (Table 3), confirming a first-mode response. For T = 0.05, 0.075, and 0.1, the dominant frequency stabilizes near 1.90 Hz—exceeding the second-order natural frequency—indicating consistent second-mode dominance.

Figure 13.

Cross–flow displacement time–distance curve under shear current. (a) T = 0.025; (b) T = 0.050; (c) T = 0.075; (d) T = 0.10; (e) T = 0.05, 0.15 m/s (control group).

Notably, despite increasing velocity gradients across these three cases, the frequencies remain comparable, while their envelope shapes diverge significantly. This discrepancy highlights a key challenge in characterizing vortex-induced vibrations (VIVs) of three-dimensional risers under shear flow.

Control experiments further demonstrate that increasing the initial velocity while maintaining a fixed temperature gradient drives the system toward higher-order modes. At 5.80 Hz—exceeding the fourth-order natural frequency—the response exhibits clear modal progression. These results establish the initial velocity as a critical determinant of both vibration frequency and modal structure in linear shear flows. Table 6 shows the vibration frequencies of the cross-flow amplitude after Fast Fourier Transform analysis under different shear flow velocity gradients.

Table 6.

Master frequency for different uniform shear currents.

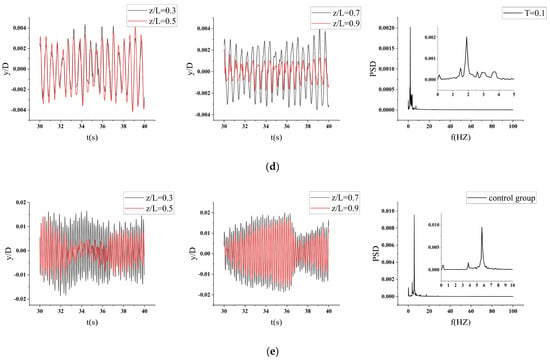

3.3.3. Influence of Shear Flow Velocity on Vortex Shedding Patterns

Figure 14 illustrates vortex shedding patterns around a riser under shear flow conditions, showing the evolution from small to large velocity gradients along with a control case. The vortex shedding behavior under shear flow conditions with an initial velocity of 0.05 m/s exhibits systematic evolution as the velocity gradient T increases from 0.025 to 0.100. In the low-gradient condition (T = 0.025), the flow velocity distribution along the riser axis remains relatively uniform, resulting in the formation of a relatively regular 2S vortex street pattern in the wake. However, the symmetry of the vortex street is already compromised compared to uniform flow conditions due to shear effects. When the gradient increases to the moderate range (T = 0.050–0.075), the velocity variation along the riser axis becomes significantly pronounced, leading to marked differentiation in vortex shedding frequencies at different heights. The middle–upper sections experience higher shedding frequencies while the lower sections maintain lower frequencies, creating a spanwise-segmented mixed vortex shedding pattern characterized by the coexistence of 2P and 2S modes.

Figure 14.

Vortex shedding patterns of a riser under shear flow conditions.

With a further increase in gradient to T = 0.100, the substantial velocity variation along the riser generates strongly three-dimensional and asynchronous vortex shedding characteristics. Significant phase differences in vortex shedding are observed at different heights, forming multiple vortical structures of varying scales and irregular arrangements in the wake. This complex flow pattern cannot be adequately described by classical three-dimensional vortex shedding models, demonstrating the highly three-dimensional nature of vortex dynamics under strong shear conditions.

Comparison with the control case (initial velocity 0.25 m/s, gradient 0.05) reveals that despite an identical velocity gradient, the higher overall flow velocity generates significantly enhanced vortex shedding energy, forming larger-scale and more clearly defined 2P mode vortex streets in the wake. This comparison demonstrates that the vortex shedding pattern in shear flow is simultaneously governed by both initial velocity and velocity gradient, where the velocity gradient primarily controls the degree of spanwise asymmetry in vortex shedding, while the initial velocity influences the vortex scale and shedding intensity. Following the same computational procedure as applied to uniform flow conditions, the Strouhal numbers under various working conditions were determined by extracting the vortex-shedding frequency characteristics of the riser and performing Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on the lift coefficient. The resulting Strouhal numbers are summarized in Table 7. The calculated Strouhal numbers in shear flow show a consistent pattern, remaining stable within the 0.19–0.21 range (mean 0.20). This regularity confirms that the vortex shedding frequency maintains a stable linear relationship with the local flow velocity, even under velocity gradients, and aligns well with classical cylinder flow theory and uniform flow results (0.19–0.21).

Table 7.

Strouhal number in shear flow conditions.

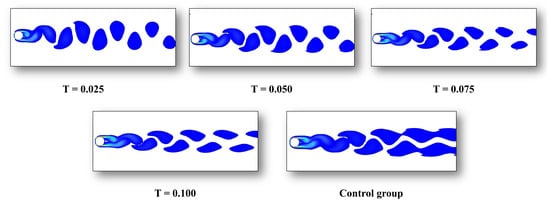

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Riser Vibration Characteristics Under Uniform Flow Versus Shear Flow

Figure 15 compares the number of excited vibration modes and the maximum vibration amplitude of the riser under both uniform flow and shear flow conditions, providing a direct visualization of how different flow regimes affect the vortex-induced vibration response. It should be noted that the horizontal axis represents the increasing velocity of the uniform flow, while the four corresponding shear flow velocities and the control case are not explicitly marked in the figure. The envelope diagrams reveal that at = 0.05 m/s (uniform flow) and T = 0.025 (shear flow gradient), the dominant vibration mode is identical; both exhibit first-mode dominance. Although the primary frequencies exceed the riser’s first-order natural frequency, with occasional contributions from the second mode, the envelopes confirm the predominance of the first mode. Notably, the vibration amplitude under uniform flow is significantly lower than that under shear flow.

Figure 15.

Maximum modal order and amplitude diagram: (a) maximum mode number; (b) maximum amplitude.

When the uniform flow velocity increases to 0.10–0.15 m/s, both flow conditions induce second-mode dominance. Here, amplitude and frequency scale with flow velocity. Under uniform flow, the amplitude peaks at = 0.15 m/s, with a maximum displacement of approximately 0.03 D occurring at z/L = 0.3, consistent with the antinode of the second mode. Similarly, for shear flow at T = 0.1, the maximum amplitude of approximately 0.02 D also localizes at z/L = 0.3, aligning with second-mode dynamics.

At higher uniform flow velocities ( = 0.25 m/s), the riser transitions to third-mode dominance, with frequencies approaching the third natural frequency. The envelope further reveals incipient fourth-mode shapes, reaching a maximum of 0.015 D. In contrast, shear flow—even at maximum velocities (0.41 m/s, exceeding the uniform flow’s range)—persists in second-mode vibration without modal transition.

Control experiments demonstrate that matching the shear flow’s initial velocity to that of the uniform flow’s v, followed by the application of a linear gradient, triggers rapid modal escalation from the second to the fourth mode. This process is accompanied by a frequency doubling, which sharply excites higher-order modes. However, due to boundary condition constraints, the amplitude remains around 0.015 D without significant amplification.

4. Conclusions

Based on the ANSYS Workbench platform, a two-way fluid–structure interaction (FSI) model was developed by coupling the Fluent and Mechanical solvers. Within the Acoustic Modal framework, wet-mode analyses of the riser were conducted to determine its natural frequencies and corresponding mode shapes. The coupled responses under uniform and linear-shear current profiles were then examined. Spatial distributions of riser amplitude were obtained for each test case; these time histories were subjected to fast Fourier transforms (FFT) to identify the dominant response frequencies. Ensemble statistics provided the cross-flow root-mean-square (RMS) amplitudes along the riser span, whose envelopes were subsequently analyzed. Finally, the FFT-derived frequencies were benchmarked against the riser’s natural frequencies, isolating the prevailing modal contributions and leading to the following conclusions:

(1) Flow-Regime Dependent Response: Vibration amplitude and frequency exhibit monotonic increases with flow velocity in both uniform and shear flows, yet demonstrate fundamentally distinct modal evolution patterns. In uniform flow, peak amplitudes reach 0.03D with frequency lock-in occurring at the third structural mode, while shear flow responses stabilize at the second mode with maximum amplitudes of 0.02D, revealing intrinsic differences in energy transfer mechanisms between the two flow regimes.

(2) Comparative Amplitude Behavior: Under low-velocity conditions (uniform: 0.50 m/s; shear: 0.05 m/s, and gradient = 0.025), shear flow induces stronger vibrations. However, this trend reverses at elevated velocities, where uniform flow generates 50% larger amplitudes (0.03D vs. 0.02D) and higher frequency components, challenging conventional assumptions about shear flow dominance.

(3) Shear Flow Sensitivity: This parametric study demonstrates that the initial velocity magnitude plays a crucial role in modal selection, with response frequency reaching 5.80 Hz—exceeding the fourth structural frequency—at elevated inlet velocities under constant gradient conditions. This establishes that both velocity magnitude and gradient collectively govern shear flow VIV characteristics.

(4) The vortex shedding behavior exhibits fundamental differences between uniform and shear flow conditions. Under uniform flow, the wake develops orderly spanwise-coherent structures, transitioning from disordered P + S mode through 2P transition to stable 2S patterns with increasing velocity. In contrast, shear flow generates inherently three-dimensional wake structures due to velocity variation along the span. While low gradients maintain approximately 2S characteristics, moderate to strong gradients produce spanwise-segmented shedding with mixed 2P-2S patterns and ultimately fully asynchronous vortex shedding. This comparison demonstrates that shear flow destroys the spanwise coherence observed in uniform flow, resulting in complex three-dimensional wake organizations that necessitate advanced modeling approaches for accurate VIV prediction in realistic marine environments.

Research Significance: The present work provides the first systematic comparison of modal evolution mechanisms between uniform and shear flows, addressing a critical knowledge gap in offshore engineering. The identified modal transition thresholds and amplitude-limiting behavior in shear flow offer new physical insights for predicting deep-water riser responses, while the quantified sensitivity to initial velocity parameters enables more accurate fatigue life prediction in practical engineering applications.

Limitations and Future Work: While this study establishes important fundamental relationships, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The numerical model assumes ideal boundary conditions and linear shear profiles, whereas real ocean environments involve complex non-linear velocity distributions and platform motions. Furthermore, the current analysis focuses on single riser configurations, neglecting potential interference effects in multi-riser systems. Future research should incorporate full-scale validation measurements and investigate coupled wave-current loading scenarios to enhance the practical applicability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Y.S. and Y.M.; methodology, Y.M.; software, Z.W.; validation, Z.W.; resources, Y.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; supervision, M.L.; project management, Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021YFC2801504), the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52231012), and the Key Joint Fund Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20581).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarpkaya, T. Vortex-induced oscillations: A selective review. J. Appl. Mech. 1979, 46, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, O.M.; Ramberg, S.E. The vortex-street wakes of vibrating cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1982, 116, 1–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, P.W. Vortex shedding from oscillating bluff bodies. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1984, 16, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ge, F.; Hong, Y. A review of recent studies on vortex-induced vibrations of long slender cylinders. J. Fluids Struct. 2012, 28, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; So, R.M.C.; Liu, Y. Vortex-induced vibrations of marine risers: A review. Ocean Eng. 2013, 58, 312–324. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, P.W. Circular cylinder wakes and vortex-induced vibrations. J. Fluids Struct. 2014, 47, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xiao, L.; Yang, L. A critical review of the intrinsic nature of vortex-induced vibrations. J. Fluids Struct. 2015, 55, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Shah, U.H. Vortex-induced vibration of flexible structures: A review. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2016, 68, 010803. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, C.H.K. Vortex-induced vibration: A selective review. J. Fluids Struct. 2016, 66, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiman, R.K.; Guan, M.Z.; Miyanawala, T.P. A review of vortex-induced vibration for flexible structures. Appl. Ocean Res. 2016, 57, 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Swithenbank, S.B.; Incecik, A.; Bearman, P.W.; Xiao, Q.; Hernandez, C.O. Vortex-induced vibration of marine risers: A historical review. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2017, 139, 041801. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Fu, S.; Ren, T. A comprehensive review of vortex-induced vibration of circular cylinders. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2018, 23, 300–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Li, M.; Xu, G.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Ma, L. Vortex-Induced Vibration of Long Flexible Cylinders: A Review. Ocean Eng. 2019, 178, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Fu, S.; Baarholm, R.; Wu, J.; Larsen, C.M. Recent advances in vortex-induced vibration of marine risers. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 94, 101987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Triantafyllou, M.S.; Karniadakis, G.E. Machine learning in vortex-induced vibration prediction: A review. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 103, 103289. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.J.; Triantafyllou, M.S.; Karniadakis, G.E. Data-driven modeling of vortex-induced vibrations: A review. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 051301. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wan, D. Vortex-induced vibration suppression for marine risers: A state-of-the-art review. Ocean Eng. 2023, 272, 113919. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Fu, S.; Baarholm, R.; Wu, J.; Larsen, C.M. Experimental investigation of vortex-induced vibration of a long flexible riser in stepped sheared flows. J. Fluids Struct. 2018, 81, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, D.; Liu, N.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Krokstad, J.R. Experimental study on the multi-mode vortex-induced vibration of a flexible riser with buoyancy modules. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 88, 102967. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, N.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Krokstad, J.R. Experimental investigation on the effect of surface roughness on vortex-induced vibration of a flexible riser. Ocean Eng. 2021, 235, 109412. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Xiao, Q. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of vortex-induced vibration of a flexible riser in shear flow. J. Fluids Struct. 2020, 92, 102823. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Karniadakis, G.E. Large-eddy simulation of vortex-induced vibration of a marine riser with complex fairing configurations. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 045112. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Hwang, J.; Sung, H.J. A multi-scale coupling algorithm for efficient VIV prediction of long flexible risers in deep water. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 408, 115933. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Yang, L.; Feng, L.; Triantafyllou, M.S. A data-driven model for vortex-induced vibration of long flexible cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 884, A8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Fu, S.; Wan, D. A hybrid machine learning framework for predicting vortex-induced vibration responses of flexible risers under unsteady flow conditions. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 110, 103525. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Li, M.; Chen, W.; Xu, G. Optimal design of helical strakes for suppressing vortex-induced vibration of marine risers using CFD. Ocean Eng. 2021, 219, 108261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; He, X. A novel adaptive fairing for vortex-induced vibration suppression of marine risers using shape memory alloys. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 544, 117435. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Song, G.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q. Biomimetic design and experimental study of marine riser fairings for vortex-induced vibration suppression. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3078, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Lu, H.; Yang, J.; Guo, R.; Zhang, B.; Sun, P. Vortex-Induced Vibration of Deep-Sea Mining Riser Under Different Currents and Tension Conditions Using Wake Oscillator Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiman, R.K.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Kareem, A. Digital twins for vortex-induced vibration monitoring and prediction of offshore risers: A review and prospectus. Mar. Struct. 2024, 94, 103567. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS, Inc. ANSYS Mechanical APDL Theory Reference; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, G.; Wang, J.; Layton, A. Numerical Methods for Fluid-Structure Interaction—A Review. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2012, 12, 337–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F. Zonal two equation kw turbulence models for aerodynamic flow. In Proceedings of the 23rd Fluid Dynamics, Plasmadynamics, and Lasers Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–9 July 1993; p. 2906. [Google Scholar]

- Launder, B.E.; Spalding, D.B. The Numerical Computation of Turbulent Flows. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1974, 3, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, Inc. ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sanaati, B.; Kato, N. Vortex-induced vibration (VIV) dynamics of a tensioned flexible cylinder subjected to uniform crossflow. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2013, 18, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Liu, C.; Lu, G. Strouhal number variation in vortex-induced vibration of a long flexible cylinder: Experiments and modelling. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 934, A39. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.M. Fluid Mechanics, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 485–487. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).