1. Introduction

Knowledge representation has traditionally relied on graph-based structures, where entities can be modeled as vertices and pairwise interactions are captured through directed or undirected edges. Graph-based analysis plays a crucial role in understanding complex networks across domains such as bioinformatics, traffic systems, recommender systems, and social networks [

1,

2] (to name a few). While effective for simple relational learning [

3,

4], such representations fail to capture the complexity of higher-order interactions that naturally occur in domains such biological systems and social networks [

5]. These interactions often involve multiple entities simultaneously and exhibit asymmetric dependencies, necessitating a shift from graph-based models to directed hypergraphs [

6,

7]. Directed hypergraphs provide a more expressive alternative, capturing higher-order relationships with explicit directionality [

6,

7].

Higher-Ordered Neural Networks (HONNs) operating on directed hypergraphs provide a principled framework to learn from such multi-way, asymmetric relationships [

8]. Unlike standard Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [

3], HONNs can leverage incidence-based formulations, spectral convolutions, and Laplacian operators tailored for higher-order structures. The integration of directionality is particularly critical, as it enables the modeling of causal flows, temporal dependencies, and knowledge hierarchies that cannot be expressed in undirected or pairwise settings.

Recent advances in hypergraph learning have introduced several spectral Laplacians; such as the normalized Laplacian, Hermitian Laplacian, and their complex-valued variants; that generalize classical graph theory to directed higher-order domains. However, existing spectral approaches are based on a single Laplacian formulation [

9], yet its impact on directed HONNs performance remains under-explored. Most studies either restrict themselves to undirected settings or fail to provide a systematic framework that unifies directionality, higher-order representations, and predictive modeling. As a result, there is a pressing need to establish a coherent mathematical and algorithmic foundation for learning directed knowledge using higher-ordered neural networks.

This work lies in unifying directionality, higher-order representations, and predictive learning into a single principled framework. Unlike prior approaches that either focus exclusively on undirected hypergraphs or adopt ad hoc definitions of directionality, we provide the first systematic study of spectral Laplacians tailored to directed hypergraphs and their integration into Higher-Ordered Neural Networks (HONNs). Our specific contributions are as follows:

We extend classical Laplacian constructions by formulating directed variants such as the Hermitian Laplacian with tunable parameter q, and its complex-valued extension. These operators explicitly balance local versus global structural information and capture phase-dependent directionality, offering unprecedented flexibility for predictive learning.

We develop a Higher-Ordered Neural Network (HONN) architecture grounded in spectral convolution, designed to exploit these new Laplacians. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first framework that systematically links Laplacian choice and parameterization with predictive performance in directed knowledge settings.

Through extensive experiments on benchmark datasets, we reveal how Laplacian formulations and q-values govern stability, convergence, and generalization. These findings provide practical guidelines for deploying HONNs in real-world scenarios where higher-order, directed dependencies are critical.

Together, these contributions establish a novel direction in neuro-symbolic [

10,

11] and hypergraph learning. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on graph and hypergraph neural networks, highlighting the limitations of existing approaches in handling directionality and higher-order relationships.

Section 3 introduces the theoretical foundations of directed hypergraphs and defines the spectral Laplacian operators used in HONN.

Section 4 presents the proposed methodology, including dataset descriptions, hypergraph construction, and model design.

Section 5 reports experimental results and ablation studies, followed by a detailed discussion in

Section 6 on general performance, stability, and comparisons with baselines.

Section 7 discusses the results with key insights and directions for future research. Finally,

Section 8 concludes this paper.

2. State of the Art and Research Gaps

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNNs) have become central to learning complex relationships in graph-structured data. GNNs, pioneered by Scarselli et al. [

3], leveraged graph topology for node embeddings, enabling nodes to aggregate information from neighboring nodes. This innovation laid the foundation for modern GNNs. Over time, methods such as MMagNet [

12] and SigMaNet [

13] extended GNNs to incorporate magnetic and sign-magnetic Laplacians, improving edge directionality and weight representation. These advancements have been impactful in tasks like spectral partitioning and link prediction. However, GNNs face challenges in scaling to dynamic, large-scale graphs and struggle to capture higher-order interactions effectively. It is important to note that SigMaNet was designed to handle directed and signed relationships in traditional Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which are limited to pairwise connections.

Building on GNN advancements, HGNNs model hypergraphs, where hyperedges connect multiple nodes simultaneously, facilitating the modeling of higher-order relationships. This approach is valuable in domains like multimodal data integration and citation classification. Models by Bai et al. [

14] and Feng et al. [

15] used convolutional and attention mechanisms to improve hypergraph representation learning. Yet, HGNNs still struggle with scalability, dynamic environments, and the integration of directional dependencies within hypergraphs.

While HGNNs have advanced the field of higher-order learning, recent models like Hypergraph Convolutional Networks (HGCNs) and Hypergraph Convolutional Networks with Hyperedge Attention (HCHAs) [

14] still have limitations. HGCN [

15] is a strong baseline that effectively extends GCNs to hypergraphs, but it operates on undirected hypergraph structures, thus failing to capture the directional information critical in many real-world systems. Similarly, HCHA introduces an attention mechanism [

16] to weigh the importance of hyperedges, but it also does not inherently model the direction of information flow. Both HGCN and HCHA show the importance of spectral and attention-based methods for hypergraphs, but they leave a significant gap in systematically handling directed higher-order relationships, which our framework is specifically designed to address.

Directed Hypergraph Neural Networks (DHGNNs) [

6] have addressed some of these challenges by integrating directionality into hypergraphs, improving the modeling of source–target relationships in domains like traffic systems and citation analysis. Tran et al. [

17] used normalized Laplacians to model dynamic interactions, and Pretolani [

6] explored directed hypergraphs for routing and connectivity. Despite this, existing DHGNNs often lack scalability, efficiency, and generalization for large, diverse datasets.

Recent work on the Generalized Directed Hypergraph Neural Network (GeDi-HNN) [

18] has made strides in overcoming the limitations of both traditional GNNs and HGNNs. GeDi-HNN introduces a novel complex-valued Hermitian matrix (the Generalized Directed Laplacian), which allows for seamless integration of directed and undirected hyperedges while generalizing existing Laplacian formulations. This development is crucial for effectively modeling asymmetric interactions and higher-order relationships. However, a significant limitation is that the model relies on a single, fixed Laplacian formulations. The broader landscape for DHGNNs still presents gaps, particularly regarding the systematic evaluation of different Laplacian formulations and their impact on model performance [

19,

20]. This indicates a need for a more flexible framework that can explore and adapt to various spectral properties beyond a singular, fixed approach. The limitations of traditional GNNs and HGNNs, particularly their difficulty in capturing directionality and complex interactions, create a gap for more expressive models. Domains such as recommendation systems, traffic networks, and academic citation analysis demand models that can represent both higher-order interactions and directional dependencies. Current methods are often inadequate, leading to suboptimal predictions and limited interpretability.

While previous works have introduced Directed Hypergraph Neural Networks (DHGNNs), they have relied on fixed Laplacian formulations without systematically evaluating their impact. The effect of different Laplacian matrices and q-values on DHGNN performance remains unexplored.

This study fills this gap by systematically comparing multiple Laplacian formulations and varying q to control the balance between local node properties and global hypergraph structure. Our goal is to provide a deeper understanding of how spectral properties influence learning stability, accuracy, and generalization in directed hypergraphs.

Recent advances in graph learning have emphasized spectral adaptability, uncertainty estimation, and structural robustness. Lin et al. [

21] proposed Graph Neural Stochastic Diffusion (GNSD), which integrates stochastic diffusion into GNNs to enhance both predictive accuracy and uncertainty estimation, particularly in noisy or out-of-distribution settings. In the hypergraph domain, Yang and Xu [

22] provided a comprehensive survey of recent HGNN models, identifying critical challenges related to expressiveness, directionality, and spectral design—challenges directly addressed by our HONN framework. Ko et al. [

23] introduced a Laplacian perturbation approach for universal graph contrastive learning, demonstrating the benefits of carefully designed spectral modifications. These works reinforce the importance of flexible Laplacian modeling and motivate our investigation of multiple Laplacian variants and adaptive spectral tuning through the q-parameter.

Table 1 provides a summary of different graph-based neural network models, highlighting their key characteristics and spectral foundation. GNNs form the foundation, relying on the Standard Graph Laplacian for simple, undirected pairwise relationships, ensuring stability but lacking the ability to model flow or group dynamics. HGNNs extend this by using the Undirected Hypergraph Laplacians to capture higher-order relationships. Concurrently, DGNNs and DHGNNs incorporate directionality into their analysis, utilizing Directed Laplacians to model flow asymmetry. DHGNNs, which are the focus of this research, offer the most comprehensive representation by combining higher-order interactions and directionality, typically via a Generalized Directed Laplacian. However, as summarized in the table, previous DHGNNs suffer from a lack of spectral flexibility due to reliance on a single, fixed Laplacian formulation. Our framework addresses this critical gap by systematically comparing Multiple Laplacian Variants and introducing the adaptive q-parameter.

However, several key challenges remain in the field of HGNNs and directed hypergraphs:

Scalability and Efficiency: Handling large hypergraphs remains a critical issue [

15,

24]. Developing methods that maintain efficiency and computational speed for massive datasets is essential [

12].

Handling Edge Weights and Directions: While progress has been made with methods like the sign-magnetic Laplacian [

13], fully integrating edge weights and directionality into HGNNs remains a significant challenge [

6,

17].

Combining Different Data Types: Incorporating heterogeneous data types into a unified hypergraph framework is difficult [

24,

25]. Future work should explore more effective ways to merge diverse data types (e.g., categorical, numerical, temporal) into hypergraph representations [

9].

Generalization Across Different Uses: Many HGNN models are domain-specific, limiting their applicability [

3]. There is a need for models that can generalize to various domains, such as social networks, recommendation systems, and biology [

1].

Improving Learning Techniques: Enhancing learning techniques, especially for sparse data, is critical for the practical application of HGNNs [

9,

12]. Improving the efficiency and accuracy of these methods will increase their effectiveness in real-world scenarios [

15].

Addressing these research gaps is crucial to enhancing the scalability, versatility, and real-world applicability of hypergraph neural networks.

3. Directionality in Higher-Ordered Neural Network

In the context of higher-order neural networks (HONNs), effectively capturing directionality is crucial for modeling complex, asymmetric relationships inherent in various data structures. This section delves into the mathematical foundations of directionality within HONNs represented as directed hypergraphs, emphasizing the role of spectral convolution and the associated Laplacian matrices.

3.1. Higher-Ordered Representation

Higher-ordered representations generalize traditional pairwise relationships in graphs to multi-way interactions. This formalism enables modeling complex systems where interactions involve more than two entities, such as knowledge graphs, social networks, and spatio-temporal data. Below, we provide mathematical definitions, properties, and proofs to establish the foundation for higher-ordered neural networks.

Definition 1. A hypergraph [26,27] (generalization of graph) is defined as , where is a finite set of n vertices. is a set of m hyperedges, where each hyperedge connects a subset of vertices. If for all i, G reduces to a traditional graph. The cardinality of a hyperedge defines its order, allowing the representation of relationships involving multiple entities simultaneously.

Definition 2. A directed hypergraph [28,29] is an extension of a hypergraph where each hyperedge is represented as an ordered pair , where is the tail set, representing the source nodes. is the head set, representing the target nodes. to maintain disjoint directionality. Directed hypergraphs generalize directed graphs by allowing hyperedges to connect multiple vertices simultaneously, enabling representation of complex n-arry relationships.

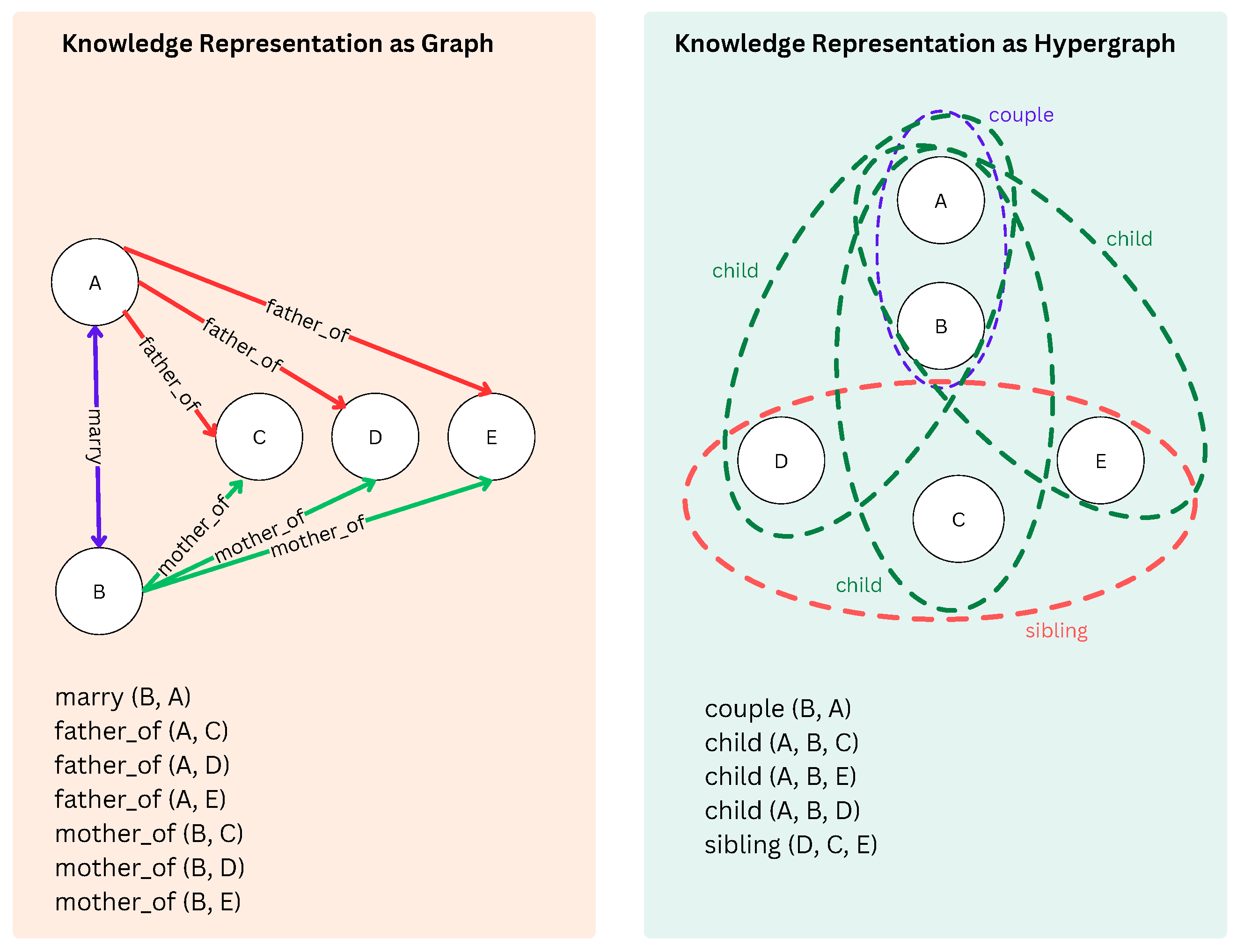

An example is provided in

Figure 1. The left panel illustrates a traditional graph representation, where pairwise directed edges encode relationships such as “father_of” and “mother_of” between vertices

and

E. For example, the directed edge

denotes “father_of(C),” while

denotes “mother_of(C).” The “marry” relationship is modeled as a bidirectional edge between

A and

B.

The right panel shows a directed hypergraph representation, where hyperedges capture multi-way, higher-order relationships. Hyperedges are represented as dashed lines encapsulating vertices. The “child” hyperedge connects and , representing the relationship between parents A and B and their children and E. In this directed hypergraph, the “sibling” relationship between and E is the target to be predicted by the Higher-Ordered Neural Network (HONN), using information encoded in other hyperedges such as “child” and “couple”. Directionality is implied through the hypergraph structure: for example, the “child” relationship flows from (parents) to (children). This demonstrates how directed hypergraphs and HONNs enable learning of higher-order relationships, such as predicting “sibling” from complex, interconnected n-arry data.

Definition 3. The incidence matrix of a directed hypergraph G is defined as follows:This matrix encodes vertex–hyperedge relationships algebraically. Property 1. The degree of a vertex is the sum of weights of all hyperedges connected to it. Mathematically; Proof. From the incidence matrix

H, the entry

if and only if the vertex

is connected to the hyperedge

. The weight of the hyperedge

is given by

, and the contribution of

to

is scaled by

, which equals 1 (for connection) or 0 (otherwise). Thus, summing over all hyperedges

gives:

□

Property 2. The total contribution of a hyperedge to its vertices can be represented as follows: Proof. By the definition of the incidence matrix

H, the absolute value

contributes 1 if vertex

is part of the tail or head of hyperedge

. Summing over all vertices

gives:

This shows that the contribution of

is the combined size of its tail and head sets. □

Property 3. For any hypergraph G with incidence matrix H, weight matrix W, and degree matrices and , the following identity holds: Proof. The vertex degree matrix

is diagonal, where each entry

represents the sum of the weights of all hyperedges connected to the vertex

. By definition:

Since

when

, this simplifies to:

Expressing this operation in matrix form:

where

computes the weighted sum of hyperedges incident to each vertex. □

The above definitions and properties provide a foundation for higher-ordered representations. Directed hypergraphs enable modeling of multi-way, asymmetric interactions, and their algebraic representation facilitates spectral analysis. These properties will underpin the development of spectral convolution and Laplacian-based techniques discussed in subsequent sections.

3.2. Spectral Convolution on Higher-Ordered Neural Network

Spectral convolution provides a powerful framework for capturing global and higher-order dependencies in neural networks operating on hypergraphs [

27,

30,

31]. By leveraging the eigenstructure of hypergraph Laplacian matrices, spectral convolution enables efficient filtering and learning over complex relationships. To perform spectral convolution, signals on hypergraphs are transformed into the spectral domain using the Fourier basis derived from the hypergraph Laplacian [

32]. The spectral hypergraph Laplacian for directionality is discussed in the next subsection.

Definition 4. Given a signal defined on the vertices of a hypergraph, the Fourier transform of x is represented as follows:where Φ

is the matrix of eigenvectors of the Laplacian matrix Θ

, and represents the signal in the spectral domain. The inverse Fourier transform is given by: The eigenvalues of the Laplacian matrix Θ represent the frequency components of the hypergraph. Low eigenvalues correspond to smooth variations, while higher eigenvalues capture rapid changes.

Definition 5. The spectral convolution of a signal x with a filter in the spectral domain is defined as follows:where is a diagonal matrix representing the spectral filter applied to the eigenvalues of Θ.

Direct computation of spectral convolution involves eigenvalue decomposition, which is computationally expensive for large hypergraphs. To address this, the filter is approximated using Chebyshev polynomials [33]. Definition 6. The spectral filter is approximated as follows:where is the k-th Chebyshev polynomial defined recursively as follows:and are the learnable parameters of the filter. This approximation avoids explicit eigen decomposition and allows efficient computation of spectral convolution, making it suitable for large-scale hypergraphs. In the context of higher-ordered neural networks, spectral convolution operates on directed hypergraphs, leveraging the Laplacian

that encodes directionality and higher-order interactions. For a given input signal

, where

d is the feature dimension, the output of a spectral convolution layer can be formulated as [

34]:

Here, the spectral filter adapts to the higher-order structure of the hypergraph, enabling the model to learn from both global and local patterns.

Spectral convolution provides a mathematically principled approach to learning on higher-order structures. Its ability to encode global relationships and adapt to directionality makes it a cornerstone of higher-ordered neural networks. The scalability offered by Chebyshev approximation ensures its applicability to large-scale datasets, while its spectral filtering capabilities enhance learning from complex, structured data.

3.3. Encoding Directionality in Directed Hypergraphs

Let be a directed hypergraph as defined in the previous section, where each hyperedge is an ordered pair with , , and weight . We set and . Vectors are column vectors; for a matrix X, denotes the conjugate transpose. The definitions below apply to real or complex-valued features. All operators introduced are Hermitian.

We define the ‘weight-free’ directed incidence

by:

Let

and define the Hermitian (Gram) moment

Since M is a weighted sum of rank-one Hermitian matrices, and .

We use a real, non-negative degree matrix given by the diagonal of

M:

We can now define the normalized adjacency as follows:

Both and are Hermitian. (We refrain from asserting without extra assumptions; our propagation uses directly.)

Directionality is injected via the complex phase attached to head incidences in (

1). Consequently, each column

has two distinct magnitudes (scaled by

and

) and two distinct phases (1 and

). Swapping

and

does not multiply

by a global unit-modulus scalar; it changes magnitudes and phases entrywise, so

(hence its spectrum) generally changes. Thus, the construction captures genuine directionality beyond undirected orientations.

For permutation behavior, let be any vertex permutation and any hyperedge permutation. With , , and , we have:

Vertex equivariance: , , hence

Within-set invariance: Any permutation of nodes inside (resp. inside ) leaves unchanged up to permutation of equal entries; hence M and are invariant under such within-set permutations.

Tail–head swap sensitivity: Replacing by generally yields a different M (and spectrum) unless in special symmetric cases.

Continuing with

Figure 1, let

and consider two directed hyperedges that encode the ternary relation

child:

each with weight

. Using (

1), the directed incidence

(columns are

; rows are

) is

With

, the Hermitian moment is

:

This matrix is Hermitian (

) and positive semidefinite (since

).

Reversing only to replaces the first column of B by , yielding a different and thus a different normalized operator . This demonstrates that the layer response depends on hyperedge direction beyond mere orientation.

3.4. Spectral Laplacians for Directionality

The Laplacian matrix is a fundamental construct in spectral graph theory, extending naturally to hypergraphs for encoding relationships among vertices and hyperedges. For directed hypergraphs, spectral Laplacians incorporate both directionality and higher-order connectivity, enabling spectral convolution to capture asymmetric dependencies effectively.

Various forms of spectral Laplacians have been developed to encode directionality and higher-order relationships. Each form has unique mathematical properties, tailored to specific computational and application needs. This section provides an overview of these Laplacians, their properties, and their relevance to directionality.

3.4.1. Normalized Laplacian

The normalized Laplacian (inspired from [

35]) is a widely used variant of the spectral Laplacian [

18], designed to stabilize computations by balancing contributions from vertices and hyperedges. This form is particularly effective in heterogeneous hypergraphs, where node and edge degrees vary significantly.

Definition 7. For a directed hypergraph , the normalized Laplacian can be defined as;where is the vertex degree matrix, where . is the hyperedge degree matrix, where . H is the incidence matrix, encoding the connectivity between vertices and hyperedges. W is the diagonal hyperedge weight matrix, where represents the weight of hyperedge . Some properties of the normalized Laplacian are [35]: Property 4. The normalized Laplacian is symmetric: This property ensures that its eigenvalues are real, a critical feature for spectral analysis.

Proof. The term involves (i) is diagonal and symmetric. (ii) W and are diagonal and symmetric. (iii) is symmetric because H is real-valued and is diagonal. Thus, the entire term is symmetric.

Since

, it follows that

is symmetric:

□

Property 5. The normalized Laplacian is positive semi-definite: Proof. The normalized Laplacian can be written as follows:

For any

:

The term

, and

is symmetric and positive semi-definite:

Thus:

□

Property 6. The eigenvalues of lie in the range : Proof. Let

, where

. Since

is a normalized adjacency-like matrix, its eigenvalues are bounded as follows:

For

, the eigenvalues satisfy:

Since

, it follows that:

□

Property 7. The normalized Laplacian is robust to variations in vertex and hyperedge degrees.

Proof. The normalization factors

and

rescale the contributions of vertices and hyperedges in the incidence matrix

H. This ensures that the impact of a vertex

or hyperedge

is independent of their absolute degrees. Specifically:

As a result, remains invariant to changes in the scale of and , ensuring robustness in heterogeneous datasets. □

3.4.2. Hermitian Laplacian

We define the Hermitian Laplacian as a variant of the spectral Laplacian designed to balance structural features and directionality. By incorporating a factor of probabilistic tuning parameter ‘q’, it provides a flexible framework for learning on directed hypergraphs.

Definition 8. The Hermitian Laplacian can be defined as follows:where q is a tunable parameter balancing the identity matrix and normalized Laplacian. H is the incidence matrix. is the diagonal vertex degree matrix. is the diagonal hyperedge degree matrix. W is the diagonal hyperedge weight matrix. The Hermitian Laplacian combines the identity matrix I with the normalized term , allowing flexibility in capturing higher-order relationships. This matrix offers the same properties as that of the normalized Laplacian and can be proved in a similar manner.

Property 8. The Hermitian Laplacian is symmetric: Property 9. The Hermitian Laplacian satisfies: Property 10. The eigenvalues of lie in the range: The Hermitian Laplacian provides a basis for spectral convolution, where its eigenvalues enable filtering of directional signals. Balancing identity and structure makes

suitable for tasks requiring a mix of local and global information. The tunable parameter

q allows focusing on structural relationships, crucial for predicting links in directed hypergraphs. Following the methods used in [

4,

13,

36], we can show that the Hermitian Laplacian is positive semi-definite and thus can be adopted as a convolutional operator.

3.4.3. Hermitian Laplacian Matrix with Imaginary Part

The Hermitian Laplacian with an imaginary part extends the Hermitian Laplacian to include directional and phase information, making it suitable for tasks involving oscillatory or cyclic dynamics in directed hypergraphs.

Definition 9. For a directed hypergraph , the Hermitian Laplacian with an imaginary part is defined as follows:where is the Hermitian Laplacian. i is the imaginary unit (). represents the phase information or imaginary component derived from the directional data. The imaginary part introduces directional dependencies, making a complex-valued Hermitian matrix. Some of its properties are:

Property 11. The Hermitian Laplacian with an imaginary part satisfies:where denotes the conjugate transpose. Proof. By construction,

Since

is symmetric and

is constructed to be antisymmetric, their sum satisfies Hermitian symmetry:

□

Property 12. The Hermitian Laplacian with imaginary part is positive semi-definite: Proof. By definition;

where

is positive semi-definite and

is antisymmetric. For any

, the quadratic form is:

The real part of

is:

Since

is positive semi-definite:

The imaginary part of

is:

Since

is antisymmetric,

contributes a purely imaginary value, which does not affect the non-negativity of the real part. Thus, the real part of the quadratic form satisfies:

and the Hermitian Laplacian with imaginary part

is positive semi-definite. □

Property 13. The eigenvalues of are complex, with the real part derived from the eigenvalues of and the imaginary part introduced by . Specifically,where represents the real part. depends on the directional flows encoded in . Property 14. The eigenvectors of are complex linear combinations of the eigenvectors of its real and imaginary components;where are the eigenvectors of , satisfying . are the eigenvectors of , satisfying . are real-valued scaling factors. 3.5. Directed Higher-Ordered Neural Network

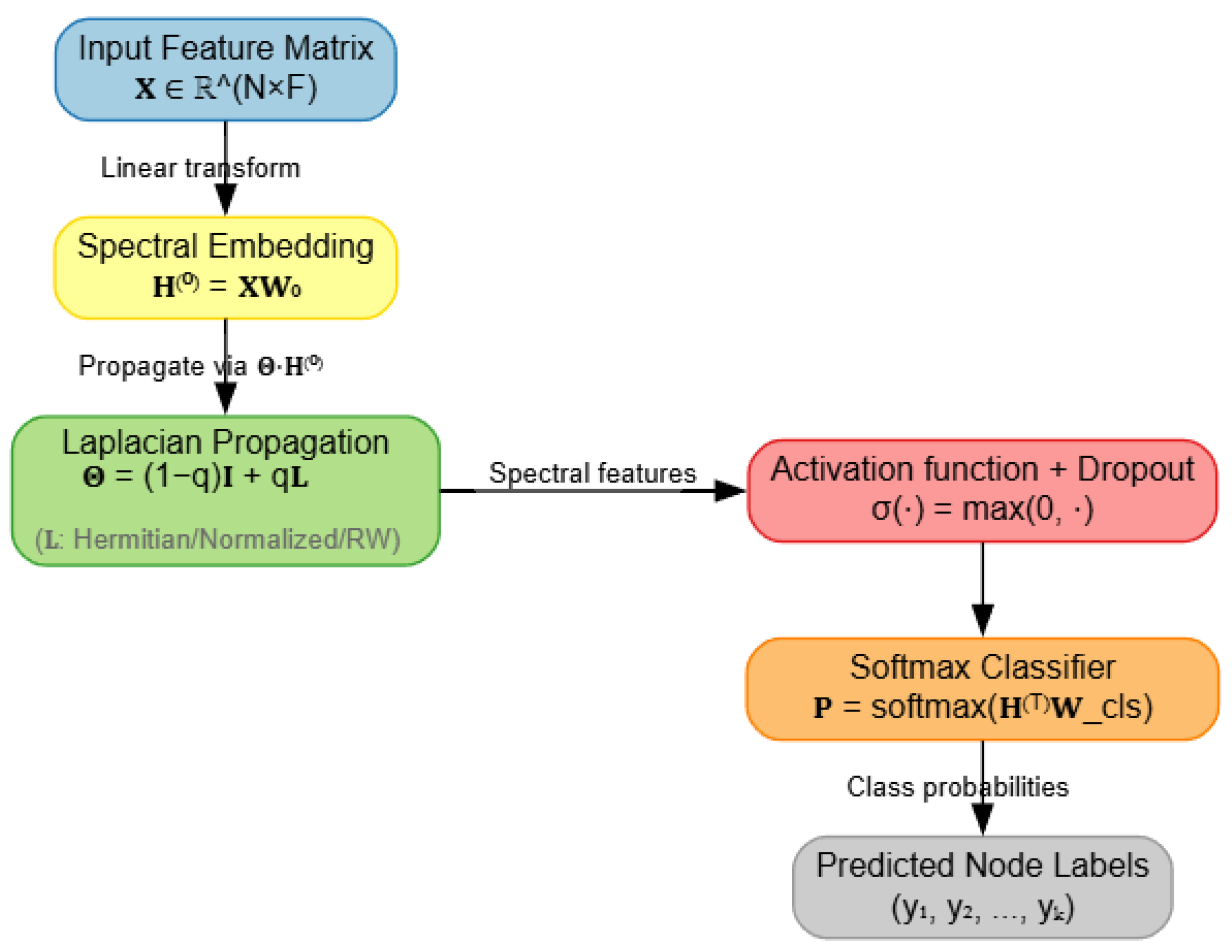

Building upon the spectral Laplacians defined above, we now introduce the Directed Higher-Ordered Neural Network (HONN) architecture. The computational flow is summarized in

Figure 2.

Let

denote the input feature matrix, where

N is the number of vertices and

F the input dimension. A linear transformation with weight matrix

produces the spectral embedding:

To capture higher-order and directional dependencies, we propagate the embedding through a Laplacian operator. Specifically, the propagation rule is:

where

,

,

is a chosen spectral Laplacian (normalized, Hermitian, or complex Hermitian) (see Abbreviations), and

balances identity preservation with structural diffusion. This step injects both local and global structural information into the representation.

The propagated features are passed through a non-linear activation function

and a dropout layer:

where common choices of

include ReLU, sigmoid, or tanh. The activation introduces non-linearity, while dropout regularizes the network by preventing overfitting. Optional attention mechanisms can refine the importance of hyperedges. This design enables HONN to model both node-level attributes and complex directional dependencies.

The HONN architecture includes one hidden layer with 64 units, followed by a ReLU activation and a dropout rate of 0.5 to improve generalization. Finally, the class probabilities are computed using a softmax classifier:

where

is the trainable weight matrix in the classifier. The predicted node labels are obtained as follows:

The classifier uses a fully connected layer with softmax activation. The Laplacian operator

is recalculated per dataset using a selected Laplacian and an optimal

q-value. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a cross-entropy loss function. Batch normalization was optionally applied before the classifier and was found to improve stability on the Citeseer and NTU-2012 datasets. This modular spectral design allows flexible insertion of new Laplacians, making the architecture adaptable to a wide range of hypergraph structures [

22].

This formulation highlights the flexibility of HONNs:

By varying L, we adapt the model to emphasize stability (Hermitian Laplacian), scale-invariance (normalized Laplacian), or cyclic/oscillatory dynamics (complex Hermitian Laplacian).

The parameter q serves as a tunable hyperparameter, controlling the trade-off between retaining local node identity and enabling global structural diffusion.

The combination of spectral embedding and Laplacian propagation ensures that both higher-order and directional dependencies are encoded in the learned representations.

Thus, HONNs generalize beyond conventional GNNs by unifying spectral theory, directionality, and higher-order relationships into a single predictive framework. Now we can list a few properties of the formulation:

Property 15. HONN Propagation is stable.

Let be the propagation operator, where L is a spectral Laplacian (normalized, Hermitian, or complex Hermitian) and . Then, the propagation of features in HONNs is stable, in the sense that the spectral radius of is bounded by: Since the eigenvalues of L are bounded (e.g., for normalized Laplacians), it follows that is also bounded, preventing uncontrolled amplification of features across layers.

Proof. The eigenvalues of

are given by:

where

are the eigenvalues of the Laplacian operator. For normalized Laplacians,

, while for Hermitian and complex Hermitian variants,

remains bounded due to positive semi-definiteness. Thus,

This ensures bounded spectral radius

and hence stable propagation. □

Property 16. The parameter governs the trade-off between local and global information. Specifically:

For : , preserving local node identity and limiting oversmoothing.

For : , maximizing structural diffusion and capturing global dependencies.

By adjusting q, HONNs adapt to the structural density of the dataset: sparse datasets benefit from smaller q (local emphasis), while dense or heterogeneous datasets favor larger q (global emphasis). This mechanism provides a principled way to balance bias and variance in learning, thereby improving generalization.

The stability property guarantees that repeated applications of HONN layers do not lead to divergence, a known problem in deep spectral models. Meanwhile, the generalization property highlights the role of q as a dataset-dependent hyperparameter, effectively controlling the expressive power of HONNs. Together, these properties explain why HONNs achieve strong performance across both sparse and dense benchmarks.

Let

be the linear map which is 1-Lipschitz and cannot amplify features. Let

be the pre-activation and let

be the incoming gradient for a differentiable loss

. Then

Proof. Differentiate (

8):

, hence

. Apply the chain rule and Cauchy–Schwarz. Finally,

. □

Assume

has

-Lipschitz gradient in

and is bounded below. Consider projected SGD with stepsizes

:

Then, the standard non-convex rate holds:

Moreover, the backpropagated gradients through

are bounded (no explosion).

Proof. By the descent lemma for

-smooth functions and non-expansiveness of the projection,

Summing over

t and using

yields the stated rate (textbook-projected SGD analysis). Boundedness of backpropagated gradients follows because each layer’s linear map has operator norm

and the activation is 1-Lipschitz. □

We can interpret the above discussion as follows: q increases when , i.e., when using L (more diffusion) locally improves the loss relative to the identity; it decreases otherwise. Thus, q adapts the spectral regime to the data: for effectively pairwise, homophilous structure, the term is small/negative (pushing ), while for directional higher-order structure, it becomes positive (pushing q upward).

For the complex variant, when , we implement the Hermitian operator via the real 2 × 2 block form , whose spectral norm equals .

4. Methodology

We evaluate the proposed Directed Higher-Ordered Neural Network (HONN) framework on multiple benchmark datasets spanning citation networks, spatio-temporal data, and web graphs [

14]. These datasets are widely used in the literature on graph and hypergraph learning, thereby allowing a rigorous comparison with existing approaches. The properties of these benchmark datasets are shown in

Table 2.

4.1. Datasets

(i) Cora and Citeseer: Cora and Citeseer are citation network datasets, where vertices correspond to scientific publications and edges denote citation relationships. Node features are bag-of-words representations of documents, while labels represent research categories. These datasets are widely adopted benchmarks in semi-supervised classification tasks.

(ii) NTU-2012: The NTU-2012 dataset is a spatio-temporal dataset constructed from multimedia and event records. Nodes represent entities such as documents, locations, and time instances, while hyperedges capture multi-way relationships across these entities. This dataset provides a challenging benchmark for higher-order learning.

(iii) WebKB Texas and (iv) WebKB Cornell: The WebKB datasets are web page networks collected from university computer science departments. Nodes correspond to web pages, and hyperedges represent hyperlinks as well as semantic groupings. These datasets are relatively small and sparse, testing the robustness of HONNs on low-degree hypergraphs.

These datasets collectively cover a wide range of scenarios: (i) medium-to-large-scale citation networks (Cora, Citeseer), (ii) heterogeneous and spatio-temporal data (NTU-2012), and (iii) small, sparse web graphs (WebKB Texas, Cornell). This diversity ensures that our evaluation tests both the stability and generalization capacity of HONNs.

4.2. Hypergraph Construction

To enable learning on higher-order and directed relationships, each dataset is transformed into a directed hypergraph representation , where is the set of vertices and is the set of directed hyperedges. The construction process differs slightly across datasets, depending on their domain characteristics.

Across all datasets, the hypergraph construction follows three steps:

Node Identification: Nodes are defined as fundamental entities such as papers (Cora, Citeseer), web pages (WebKB), or spatio-temporal entities (NTU-2012).

Hyperedge Formation: Hyperedges are created based on co-occurrence or relational patterns. In citation datasets, hyperedges capture sets of references; in web graphs, they capture sets of outgoing hyperlinks; in spatio-temporal data, they capture entities involved in the same event.

Directionality Assignment: Each hyperedge is assigned a tail set (source entities) and a head set (target entities), enforcing a directed flow of influence. This step distinguishes HONNs from traditional hypergraph methods by explicitly embedding asymmetric dependencies.

For citation networks (Cora, Citeseer), each publication corresponds to a vertex , and citations are used to form directed hyperedges. If a paper cites multiple references, the citing paper forms the tail set and all cited papers form the head set . This captures the asymmetric, multi-way flow of knowledge inherent in citation networks.

In NTU-2012, vertices represent heterogeneous entities such as documents, locations, and time points. Hyperedges are constructed to connect all entities involved in the same event. Directionality is enforced by assigning temporal order: entities occurring earlier form the tail set , and subsequent entities form the head set . This enables modeling of causal and temporal dependencies.

For Web Graphs (WebKB Texas and Cornell), nodes correspond to individual web pages, with text-based features extracted from their content. Directed hyperedges are constructed by grouping all outgoing hyperlinks from a page into a single multi-target hyperedge. That is, for a source page u, the hyperedge is defined as and , where are the target pages linked by u. This construction captures both the multi-way and directional nature of web navigation.

For all datasets, the hypergraph is encoded by an incidence matrix

, where entries are defined as follows:

This algebraic representation preserves directionality and enables the use of spectral Laplacians defined in

Section 3. It also generalizes standard graph structures: when

and

, the representation reduces to a directed graph.

4.3. Laplacian Matrix Construction

Once the directed hypergraph is constructed, we compute its spectral representation via Laplacian matrices. The Laplacian encodes both the incidence structure and directionality of hyperedges, serving as the core propagation operator in the HONN framework.

Let

denote the incidence matrix as defined in

Section 4.2, and let

be the diagonal matrix of hyperedge weights. Then, the vertex degree matrix

and hyperedge degree matrix

are given by:

Following

Section 3.2, the normalized Laplacian is defined as follows:

which ensures scale invariance and robustness to degree heterogeneity.

To balance identity preservation and structural diffusion, we define:

Here, the tunable parameter q controls the relative emphasis on local node identity versus global structural propagation.

For tasks requiring phase information and directional flow, we extend the Hermitian Laplacian with an imaginary part:

where

encodes antisymmetric directional dependencies. This construction yields a complex-valued operator that enriches feature propagation with oscillatory and cyclic dynamics.

4.4. Preprocessing and Training Strategy

Once the directed hypergraph and Laplacian matrices are constructed, the datasets undergo preprocessing and the HONN framework is trained using standardized protocols to ensure fair evaluation.

- a.

Feature Normalization:

All node features are normalized to unit variance to prevent scale imbalances. In citation datasets (Cora, Citeseer), features are bag-of-words representations normalized row-wise. In WebKB datasets, TF-IDF normalization is applied to text features. For NTU-2012, spatio-temporal features are standardized to zero mean and unit variance.

- b.

Data Splitting:

Each dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets. We follow conventional semi-supervised splits:

Training set: 60% of nodes with labels.

Validation set: 20% of nodes used for hyperparameter tuning.

Test set: 20% of nodes reserved for final evaluation.

To ensure robustness, we also repeat experiments with multiple random splits and report the mean and standard deviation of classification accuracy.

- c.

Training Strategy:

The HONN is trained with the Adam optimizer. The cross-entropy loss function is applied on the labeled nodes:

where

is the set of labeled vertices,

is the ground-truth label indicator, and

is the predicted probability for class

k. Since different Laplacian formulations impact gradient flow and convergence stability, tuning the learning rate

is critical. To optimize

, a grid search strategy is applied:

where

represents the optimal learning rate that maximizes the validation score. This approach ensures that the training process remains stable under different Laplacian operators, addressing potential issues such as gradient vanishing or explosion [

37,

38].

Similarly, while we apply grid search to determine optimal

q-values for each dataset, this process is not the core innovation of our work. Rather, it supports a broader spectral adaptation framework designed to study the interaction between Laplacian formulations and spectral weighting. By decoupling the Laplacian operator from the spectral balance parameter

q, our model gains flexibility in capturing both local and global structural information. Unlike previous architectures that rely on fixed spectral assumptions [

18], our approach enables systematic tuning and structural adaptation across datasets. This design allows for empirical insight into how

q and Laplacian type jointly influence learning dynamics [

23].

- d.

Regularization:

To mitigate overfitting and stabilize training, we adopt:

- e.

Hyperparameters:

Key training hyperparameters are summarized as follows:

Learning rate: .

Maximum epochs: 100.

Early stopping: triggered if validation loss does not improve within 20 epochs.

Activation functions: ReLU, sigmoid, and tanh (evaluated comparatively).

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed HONN framework, we adopt multiple evaluation metrics that capture predictive accuracy, stability, and generalization capacity.

a. Classification Accuracy. The primary evaluation metric is node classification accuracy, defined as follows:

where

denotes the test set,

is the predicted label,

the ground-truth label, and

is the indicator function.

b. Statistical Robustness. To account for variability in dataset splits and initialization, we report the mean accuracy and standard deviation over 100 independent runs. This ensures that improvements are statistically significant and not due to random chance.

c. Generalization via q. To evaluate adaptability to different structural regimes, we perform ablation analysis with respect to the q parameter. Generalization is assessed by measuring accuracy trends as q varies from 0 to 1. Robust models exhibit smooth performance across a wide range of q values, whereas unstable models degrade sharply.

e. Comparative Baselines. HONN results are compared against state-of-the-art baselines including:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

12,

13,

39],

Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNNs) [

12,

15],

Directed Graph-based Semi-Supervised Learning (DGSSL) [

17],

Hypergraph Convolutional Networks with Hyperedge Attention (HCHAs) [

14].

This comparative evaluation highlights the advantages of incorporating directed higher-order representations.

5. Results

We present the performance metrics of the proposed Directed Hypergraph Neural Network (HONN) evaluated on four benchmark datasets:

Cora,

Citeseer,

NTU-2012,

Cornell, and

WebKB Texas. The evaluation focuses on accuracy, stability, and overall effectiveness compared to established models, including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

12,

13,

39], Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNNs) [

12,

15], and Directed Graph-based Semi-Supervised Learning (DGSSL) [

17]. These results demonstrate HONN’s potential as a robust and reliable model for hypergraph learning, highlighting its superior generalization capabilities and adaptability to complex graph structures.

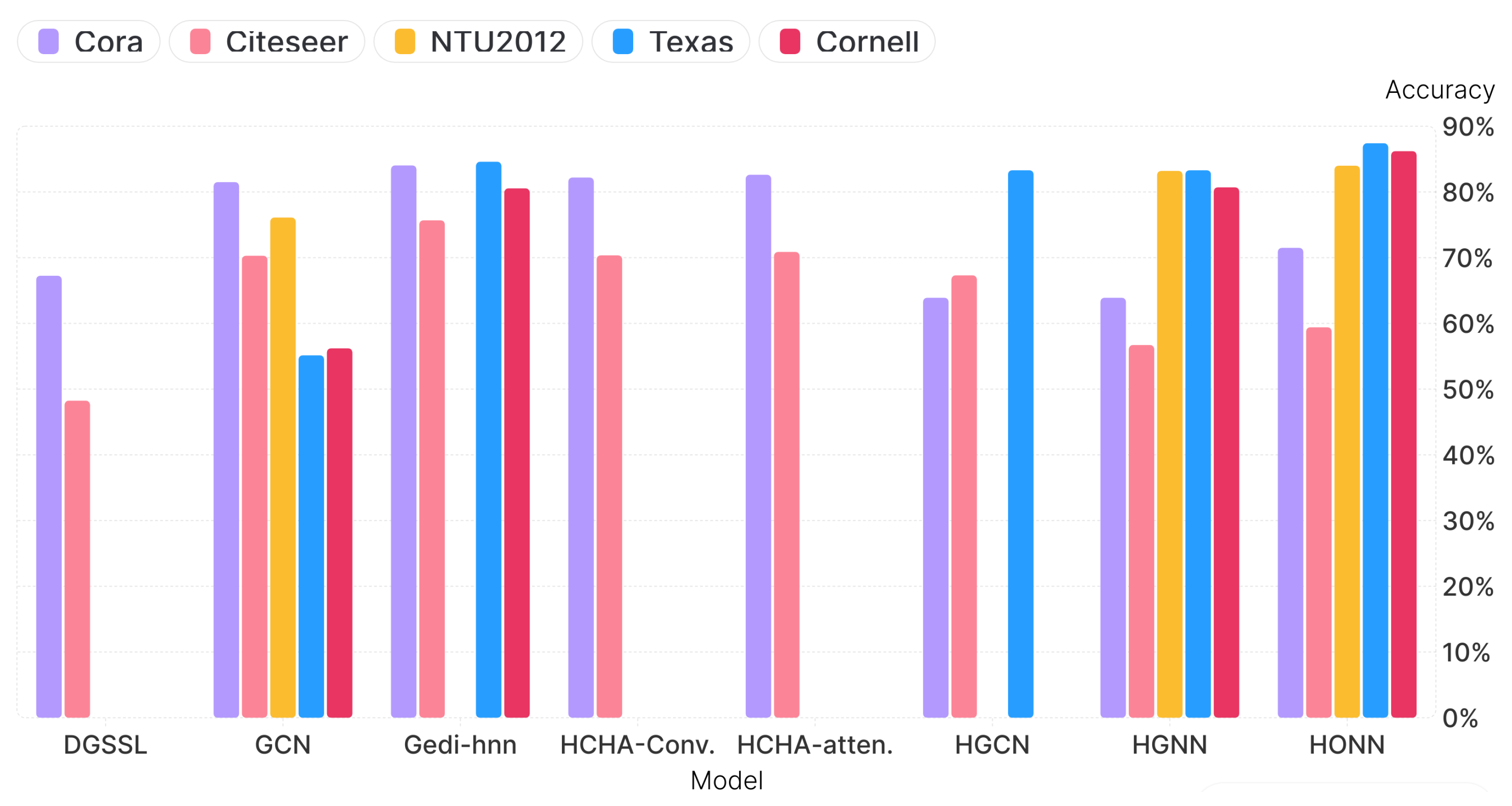

Table 3 summarizes the performance of HONN alongside other models. Notably, HONN achieves competitive results across all datasets, often surpassing or matching the best-performing models. While GCN shows higher accuracy on certain datasets, HONN stands out for its stability and ability to consistently handle directed hypergraph structures.

On the Cora dataset, HONN achieved an accuracy of 71.5% with a best q-value of 0.9. While the GCN outperformed HONN with an accuracy of 81.5%, it was also surpassed by HCHA-Conv. at 82.19% and HCHA-atten. at 82.61%. HONN exhibited higher stability across different splits, making it a suitable choice in scenarios with noisy or variable data.

For the Citeseer dataset, HONN attained an accuracy of 59.4%, outperforming DGSSL [

17] and HGNN while maintaining competitive stability with a best

q-value of 0.35. Although GCN and HGCN recorded higher accuracies, and are both exceeded by HCHA-Conv. 70.35% and HCHA-atten. 70.88%, HONN’s consistent performance emphasizes its reliability in real-world applications requiring robust generalization.

On the NTU-2012 dataset, HONN achieved the highest accuracy of 84%, surpassing both HGNN (83.2%) and GCN (76.1%). This performance demonstrates HONN’s ability to effectively capture intricate relationships within dense and complex datasets, positioning it as a state-of-the-art approach for hypergraph learning.

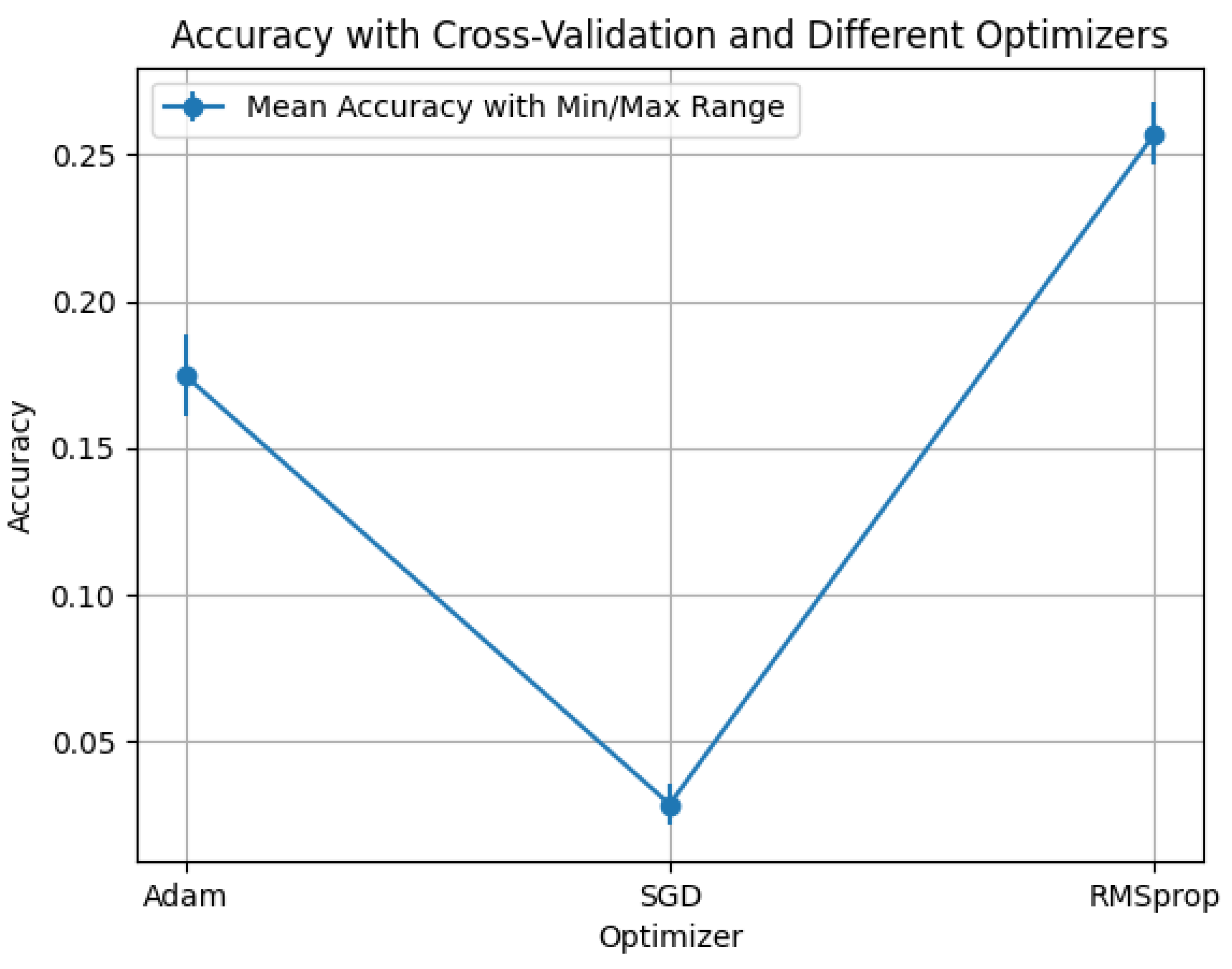

Figure 3 shows the accuracy (in %) for the various datasets.

For the WebKB Texas dataset, HONN achieved an accuracy of 87.4%, outperforming all other models, including HGNN (83.3% ± 7.4) and Gedi-hnn (84.59% ± 4.78). Using ReLU as the activation function, the Hermitian Laplacian matrix, and the Adam optimizer, HONN’s best q-value of 0.05 reflects its adaptability to directed hypergraph structures, solidifying its applicability to domain-specific tasks.

For the Cornell dataset, HONN achieved an accuracy of 86.2%, outperforming HGNN (80.7% ± 2.7) and Gedi-hnn (80.54% ± 2.79). Using ReLU as the activation function, the Hermitian Laplacian matrix, and the Adam optimizer, HONN’s best

q-value of 0.1 demonstrates its ability to effectively capture the directed hypergraph structure of the data. These results emphasize HONN’s capacity to outperform traditional and hypergraph-based models, solidifying its effectiveness for complex, domain-specific tasks.

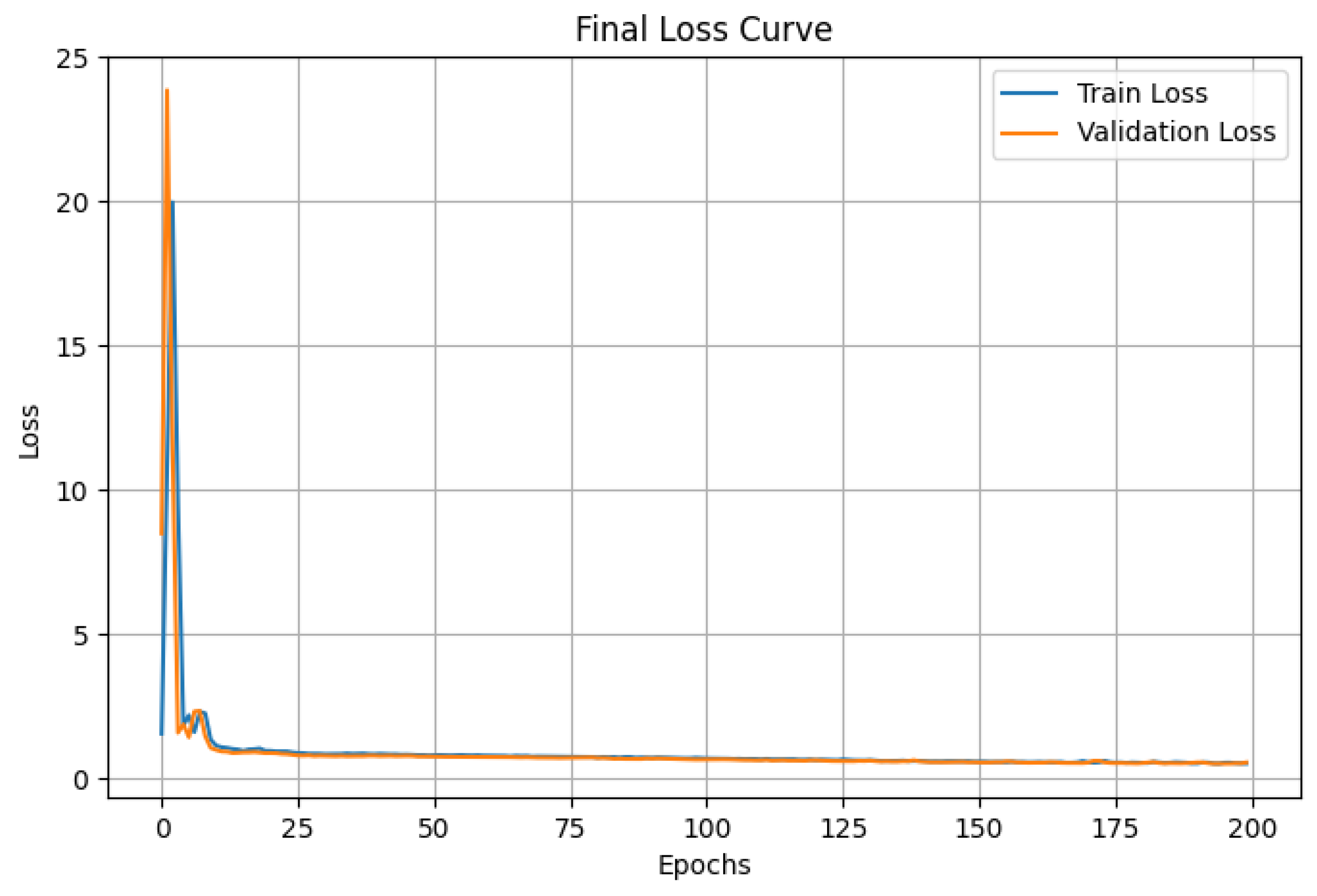

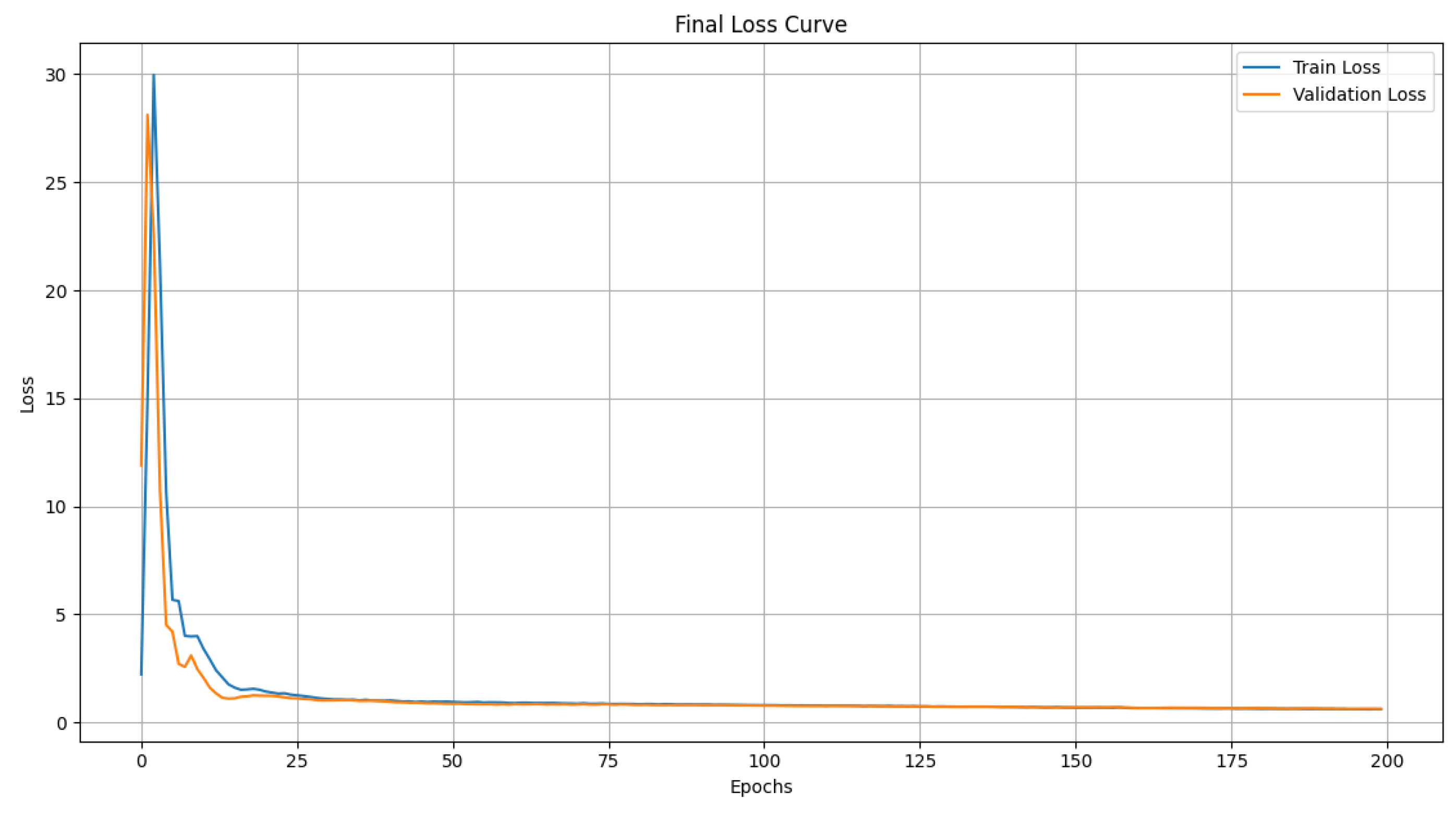

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the loss curves obtained during training and validation on the WebKB Texas and Cornell datasets, respectively.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present the evolution of the Train Loss and Validation Loss over 200 epochs for the WebKB Texas and Cornell datasets. In both cases, the model exhibits fast and stable convergence. The loss drops sharply within the first 25 epochs. Crucially, the validation loss curve closely tracks the training loss curve and stabilizes at a low value. This tight correlation, even across 200 epochs, is a strong indicator of the HONN model’s robust generalization capacity and confirms the absence of significant overfitting on these two critical datasets, validating the stability of the spectral approach used.

The interval accompanying each result (e.g., ) represents the standard deviation () of the classification accuracy across multiple independent runs, serving as a critical indicator of the model’s stability and robustness. A smaller , such as the on NTU2012, signifies high consistency, demonstrating that HONN reliably converges to the optimal performance regardless of random initialization or data partitioning. Conversely, the larger intervals on smaller, more variable datasets like Texas () and Cornell () are expected, reflecting the inherent challenge of generalizing from limited training samples; however, even with this variance, the high mean accuracy of HONN underscores its superior ability to extract robust features from these challenging hypergraphs.

The results demonstrate that the Hypergraph Optimal Neural Network (HONN) is a highly robust and versatile hypergraph learning framework. While the HCHA models (Convolutional and Attention) achieve the highest raw accuracy on the standard benchmarks of Cora and Citeseer, HONN’s consistent performance highlights its superior stability and reliability, making it suitable for noisy environments. Crucially, HONN registers state-of-the-art results on the complex, domain-specific datasets of NTU-2012 (highest accuracy), WebKB Texas, and Cornell. This success, particularly over fixed-Laplacian methods like GeDi-HNN, validates that the tunable q-parameter and flexible spectral formulations enable HONN to effectively adapt to and generalize from diverse, complex, and directed hypergraph structures.

Computational Time and Efficiency Analysis

To evaluate the efficiency of the Directed HONN framework, we analyze two distinct aspects of computational performance: overall resource consumption and granular training speed. All experiments were conducted on a standard CPU (AMD Ryzen 5, 8 GB RAM (AMD, Santa Clara, CA, USA)) without GPU acceleration, providing a conservative measure of runtime.

The analysis of overall resource consumption is detailed in

Table 4, where time is reported as total run time, and memory as peak memory usage. The HONN model’s performance shows a wide variance in computational resources, with Citeseer having the highest memory usage at 623.98 MB and a run time of 5 h 28 min 34 s, while Cornell had the lowest memory (379.11 MB) and shortest run time (8 min 7 s). The runtime and memory usage are strongly correlated with dataset size: the smaller graph datasets like Texas and Cornell (both ∼180 nodes) require minimal time and memory, whereas the larger citation graphs Cora (∼2700 nodes) and Citeseer (∼3300 nodes) require significantly more, indicating that the complexity of processing a larger graph is a primary driver of resource consumption. Notably, the NTU-2012 action recognition dataset, which is a massive multi-terabyte data volume of complex video and skeletal data, results in the longest run time (7 h 11 min 40 s), though its peak memory is not the highest, likely due to data being processed sequentially or in smaller batches. Finally, the directionality of the graph (present in citation networks like Cora and Citeseer) can significantly increase both runtime and memory usage for sophisticated models like HONN, as it requires the model to perform separate message aggregations for incoming and outgoing edges, essentially doubling the processing logic and memory needed to store directional information, which explains why these directional graphs consume more resources than the smaller graph datasets.

Further analysis of training efficiency is provided in

Table 5, reporting the average epoch duration, convergence rate, and best-performing Laplacian variant. As expected, small-scale datasets such as Cornell, Texas, and Cora exhibited rapid convergence, with average epoch times under 8 milliseconds. This low epoch time is primarily due to the relatively small size of the datasets, both in terms of node count and feature dimensionality. The model converged within 200 epochs for all datasets, and Laplacian selection had minimal impact on per-epoch timing. However, the Hermitian Laplacian consistently yielded faster convergence on structurally sparse graphs (Cornell, Texas, Cora), while the Normalized Laplacian performed better on larger or denser datasets (NTU-2012, Citeseer) [

12,

40].

Overall, HONN demonstrates strong computational efficiency, with low memory overhead and rapid training across diverse graph structures. Its modular spectral design enables scalability while maintaining consistent convergence behavior. Theoretical time complexity per forward pass is , where is the number of hyperedges and the number of nodes, assuming sparse Laplacian operators.

6. Ablation Studies

To evaluate the contribution of different Laplacian formulations and activation functions in the HONN framework, we performed ablation studies exclusively on the NTU-2012 dataset. This dataset was selected due to its heterogeneous and spatio-temporal structure, which makes it well suited for stress testing spectral propagation operators.

For each Laplacian operator, we fixed all hyperparameters (optimizer, learning rate, dropout, etc.) and varied only the activation function among

ReLU,

sigmoid, and

tanh. We then plotted accuracy trends as a function of

q in the range:

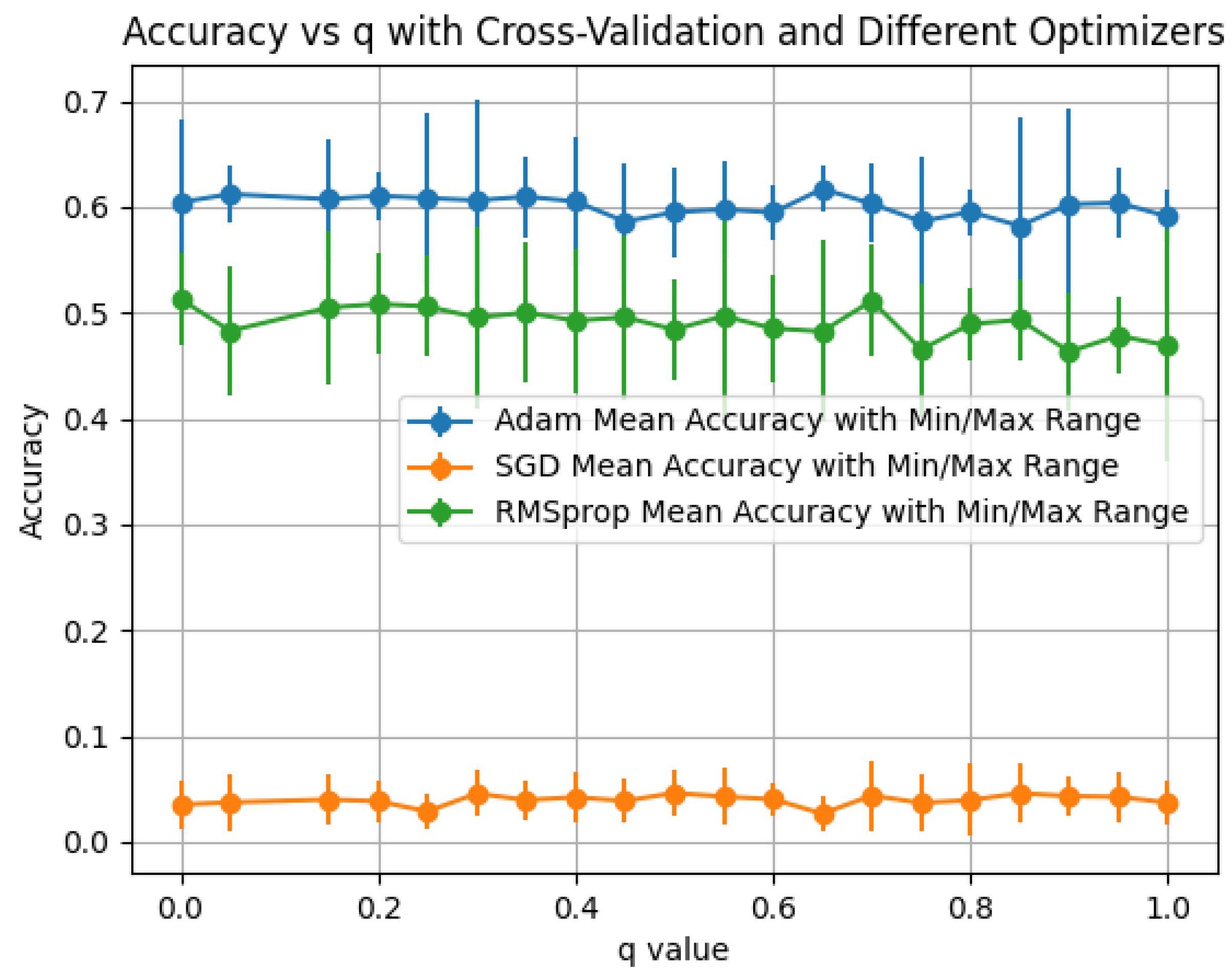

6.1. Hermitian Laplacian

We evaluate the

q-mixed propagation

with the real, incidence-based Hermitian operator

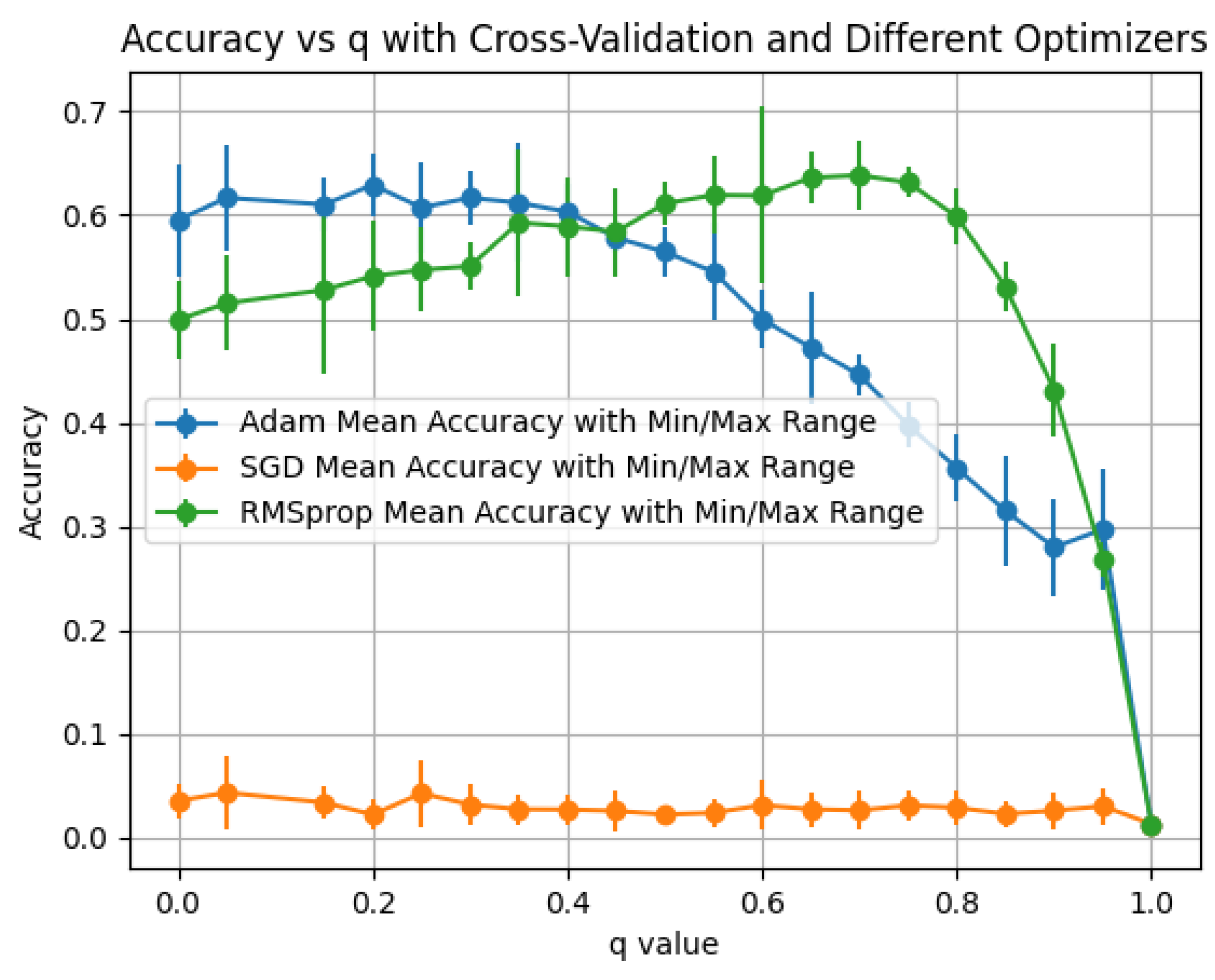

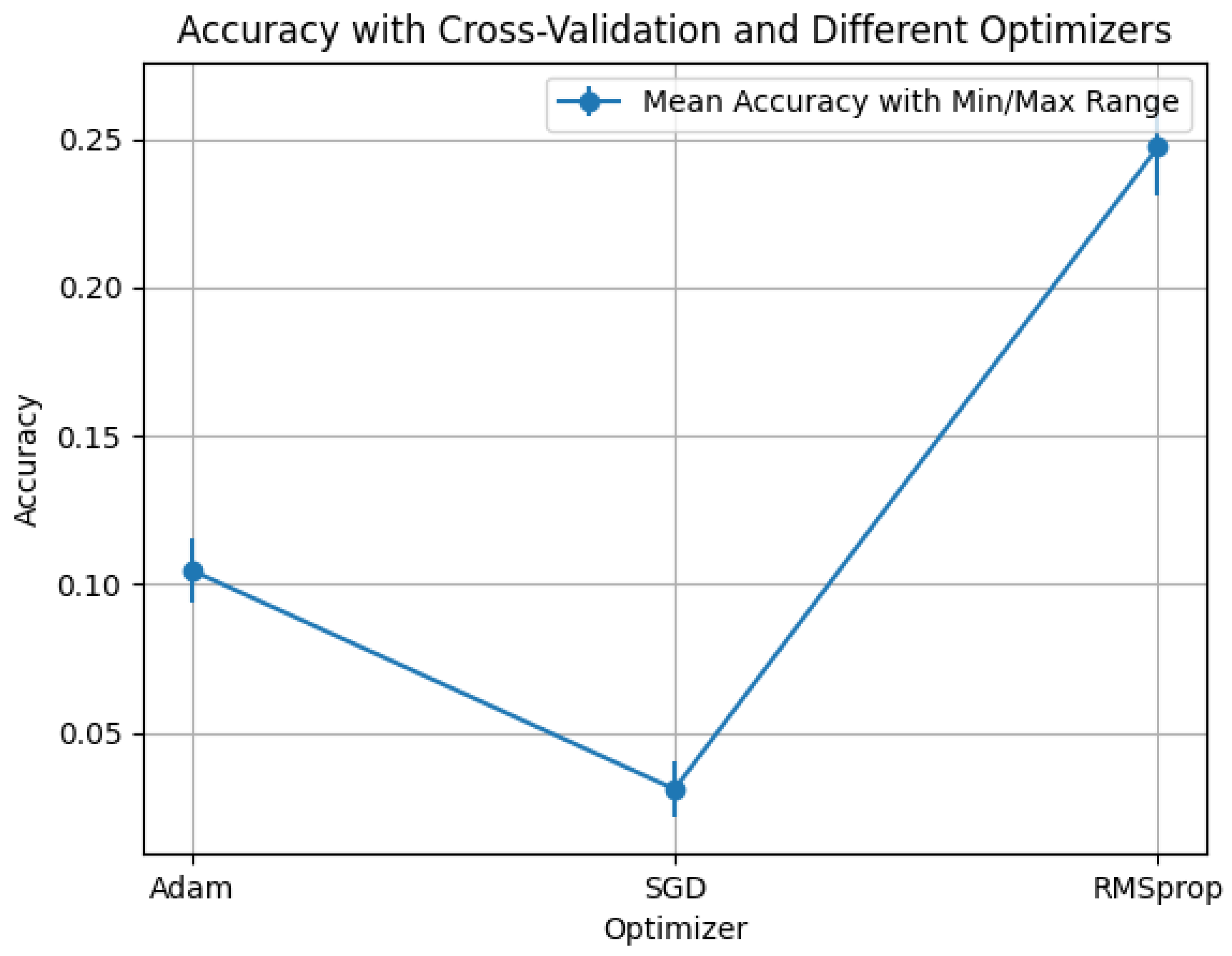

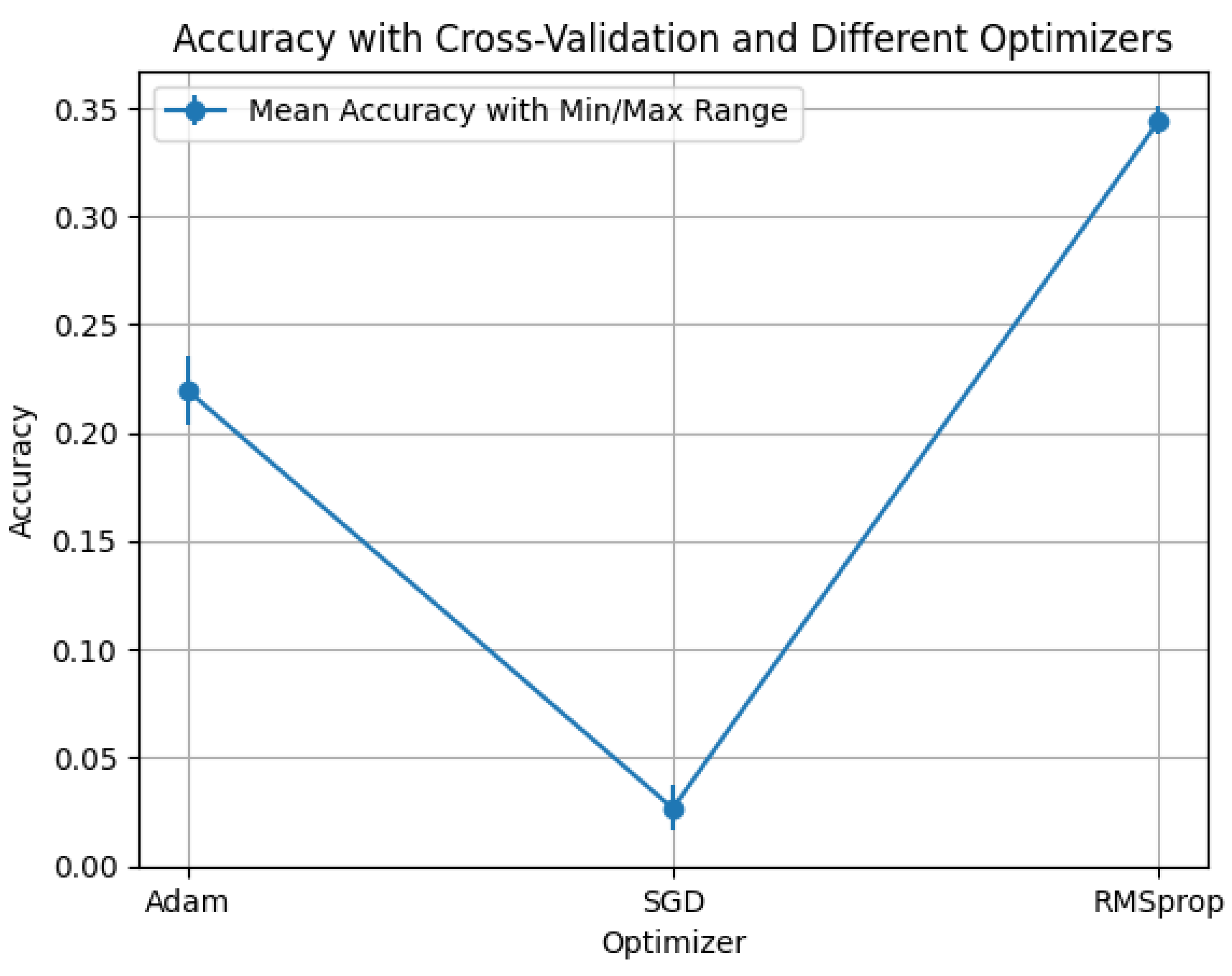

For each activation (ReLU, sigmoid, tanh) we stratify results by optimizer (Adam, RMSprop, SGD) while keeping all other hyperparameters fixed. Curves report mean accuracy; error bars denote the min–max range across the cross-validation folds and seeds used in our experimental protocol.

Observations: Across all three activations (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8),

Adam consistently dominates,

RMSprop is second-best, and

SGD remains uniformly low and nearly flat over

q. The dependence on

q is mild: the strongest curves form broad plateaus from

to

with only small dents/spikes at a few values, indicating that performance is largely insensitive to

q under this operator. Comparing activations,

tanh+Adam attains the highest peak among the three settings for the Hermitian operator, with

ReLU+Adam a close and very stable second.

Sigmoid underperforms markedly under all optimizers, consistent with saturation.

The flatness of the best curves over q aligns with Property 15 (HONN propagation is stable): for Hermitian L, the spectral map ensures and induces gradual eigenvalue shifts, which explains the broad accuracy plateaus observed here.

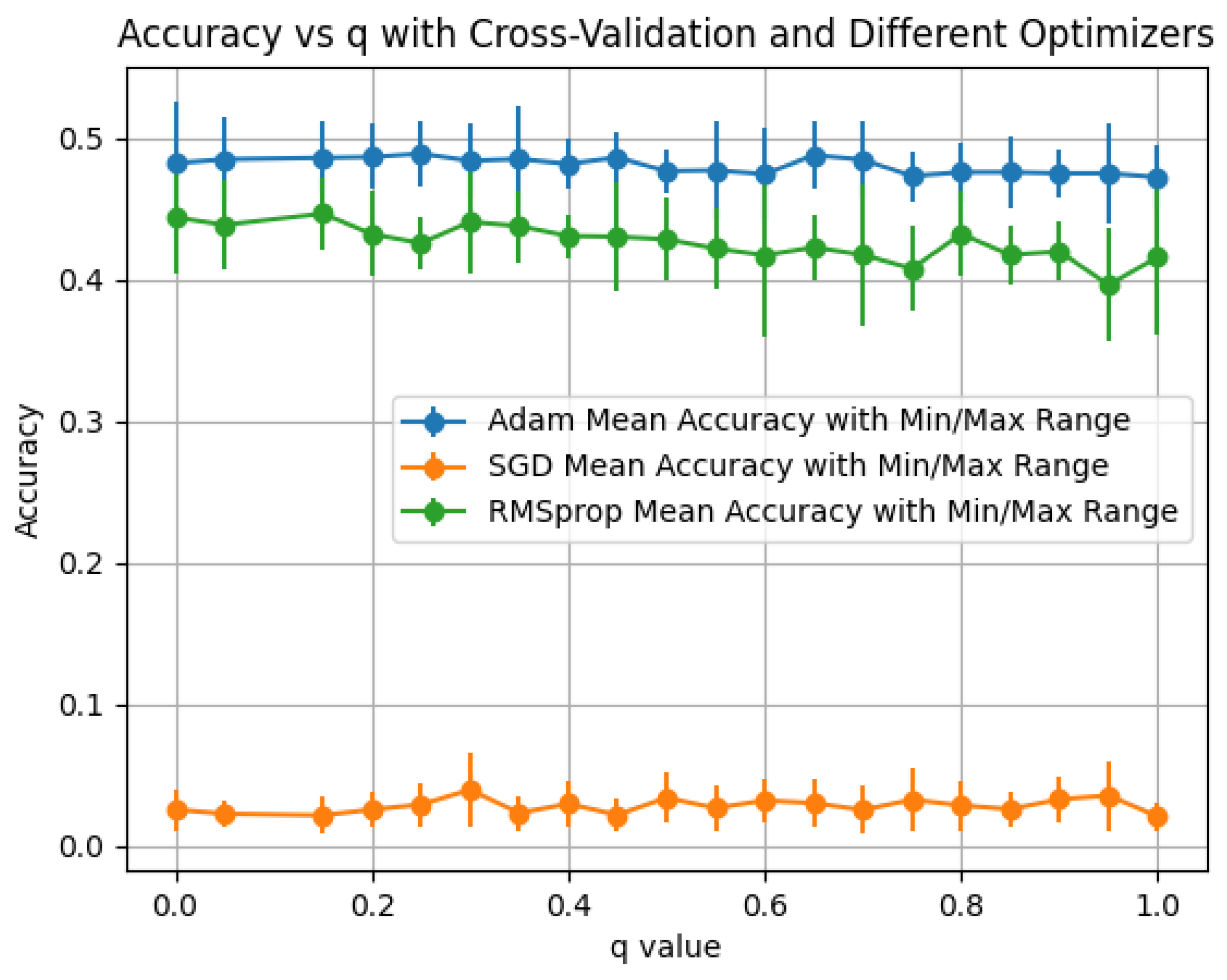

6.2. Complex Hermitian Laplacian

We extend the real Hermitian operator to its phase-aware counterpart

which preserves Hermitianity (hence a real spectrum) while injecting direction-dependent phase information. We evaluate the

q-mixed operator

across activations (

ReLU,

sigmoid,

tanh) and optimizers (

Adam,

RMSprop,

SGD) for

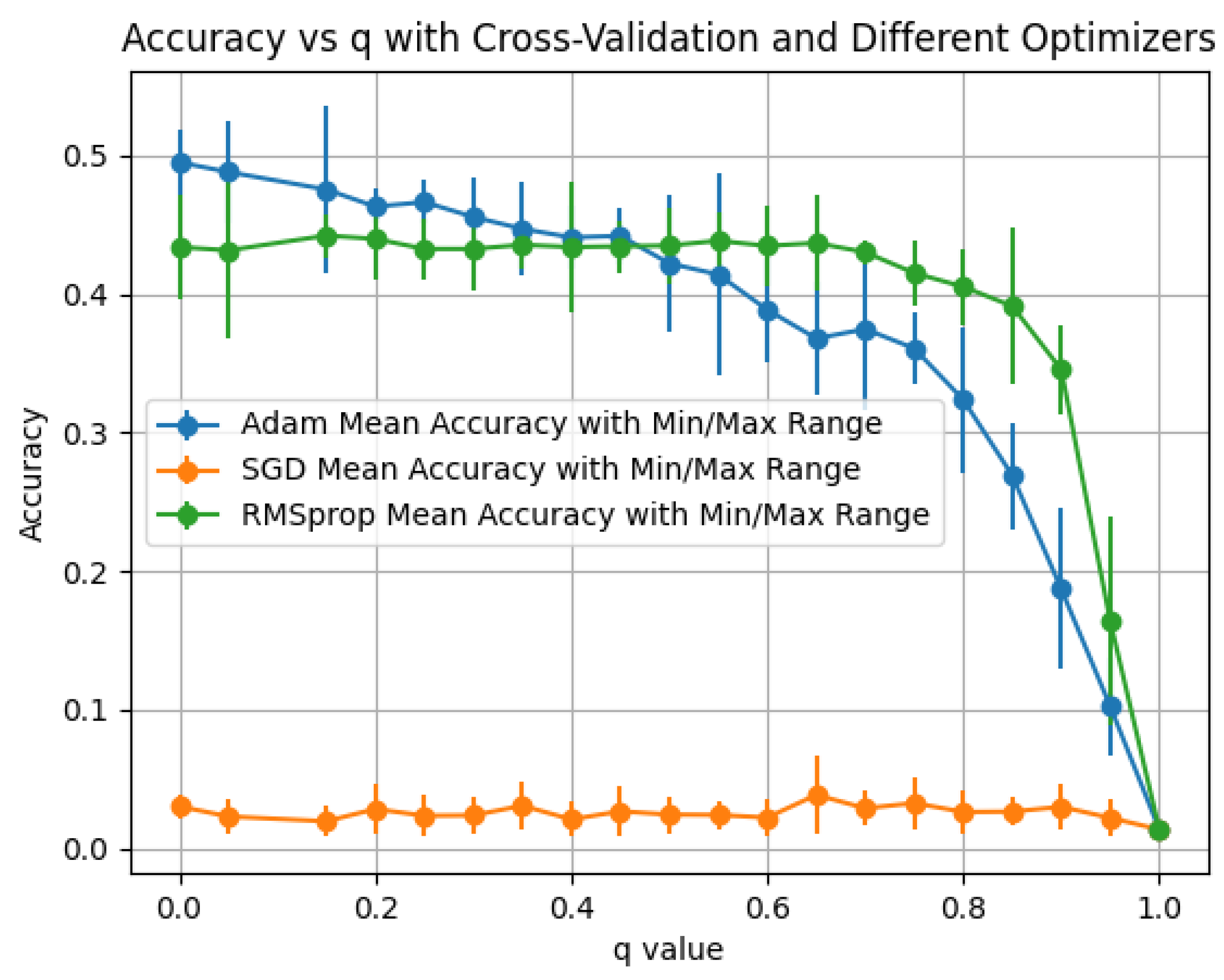

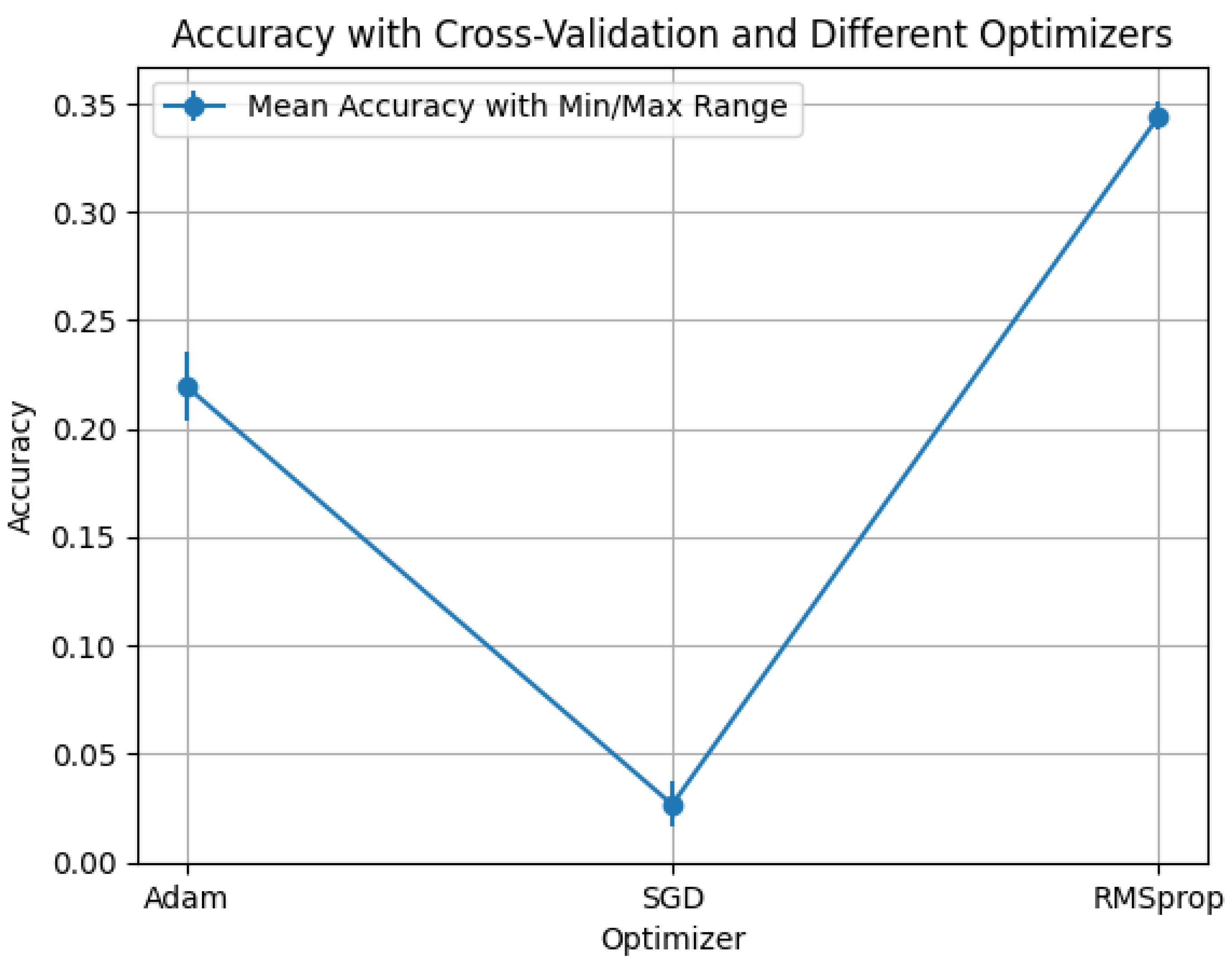

. Curves report mean accuracy; error bars show the min–max range across folds/seeds.

Observations: (1)

ReLU (

Figure 9):

Adam attains the highest values at small

q (

–

for

) and then declines steadily;

RMSprop improves with

q and overtakes near

but peaks lower (

). All optimizers collapse sharply as

, indicating sensitivity to full diffusion in the phase-aware operator.

SGD remains uniformly low. (2)

Sigmoid (

Figure 10): overall accuracy is lower than ReLU/tanh;

Adam >

RMSprop ≫

SGD for most

q, with a pronounced decline as

q increases. (3)

Tanh (

Figure 11): this setting achieves the

best overall peak, with

RMSprop reaching

at

;

Adam is strong for small

q (

–

) but decreases for larger

q. The optimal

q band is narrower than in the real Hermitian case, underscoring the need to tune

q and the optimizer jointly for phase-sensitive diffusion.

Since is Hermitian, Property 15 applies and . Compared to , the phase structure changes the eigenbasis so that increasing q redistributes energy along phase-aligned modes; near , this can cause destructive interference, which explains the sharp drops observed at high q.

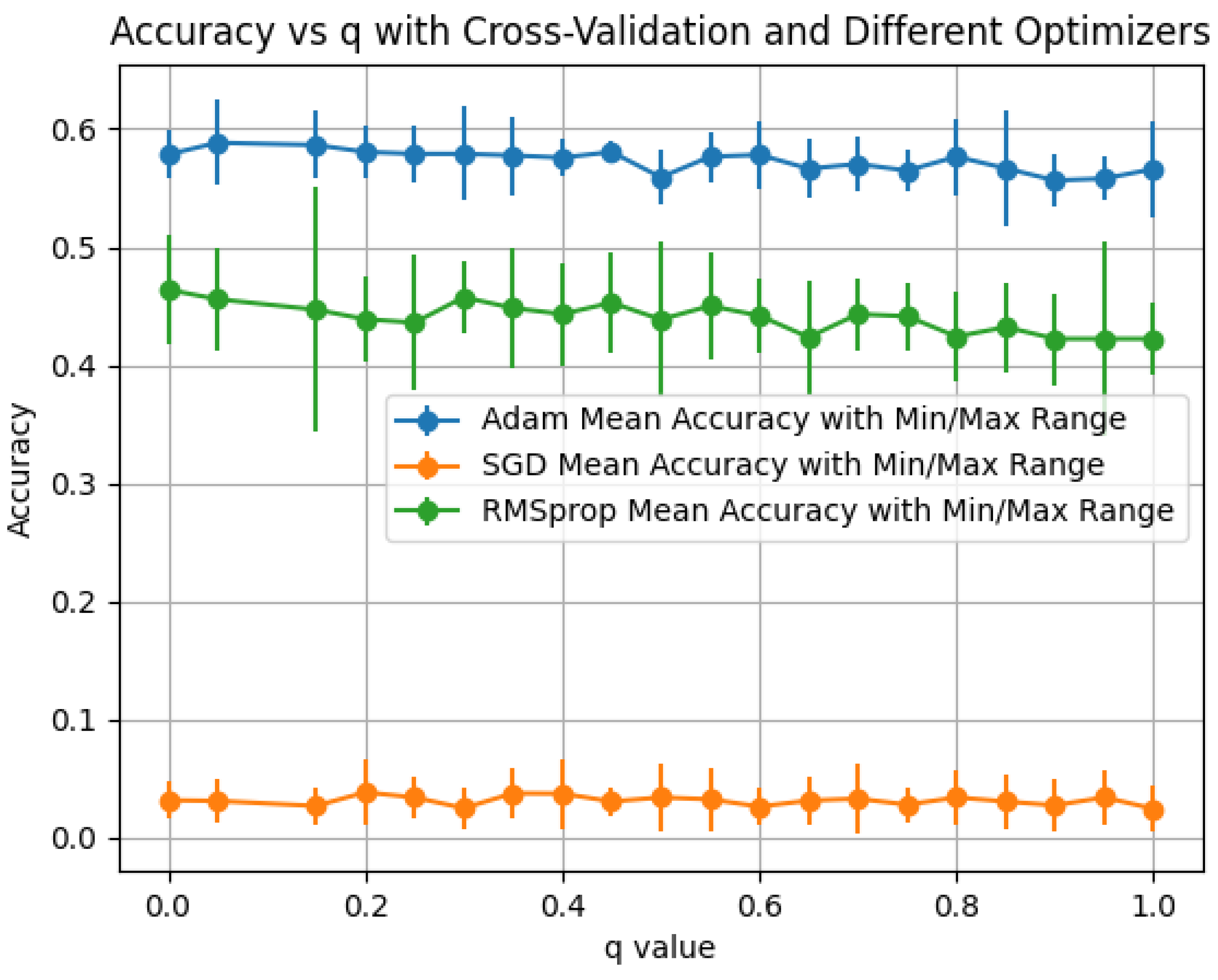

6.3. Normalized Laplacian

For the normalized Laplacian,

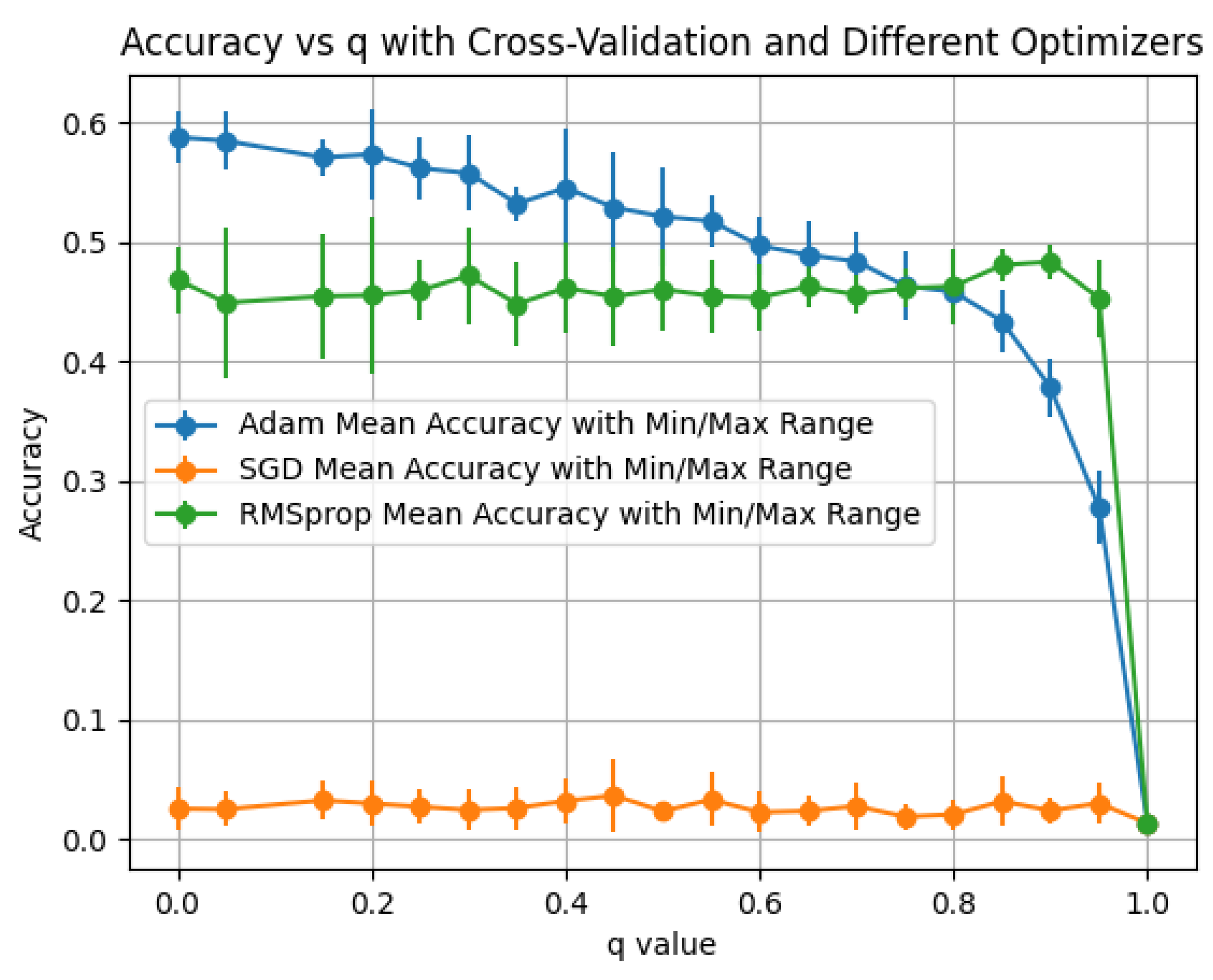

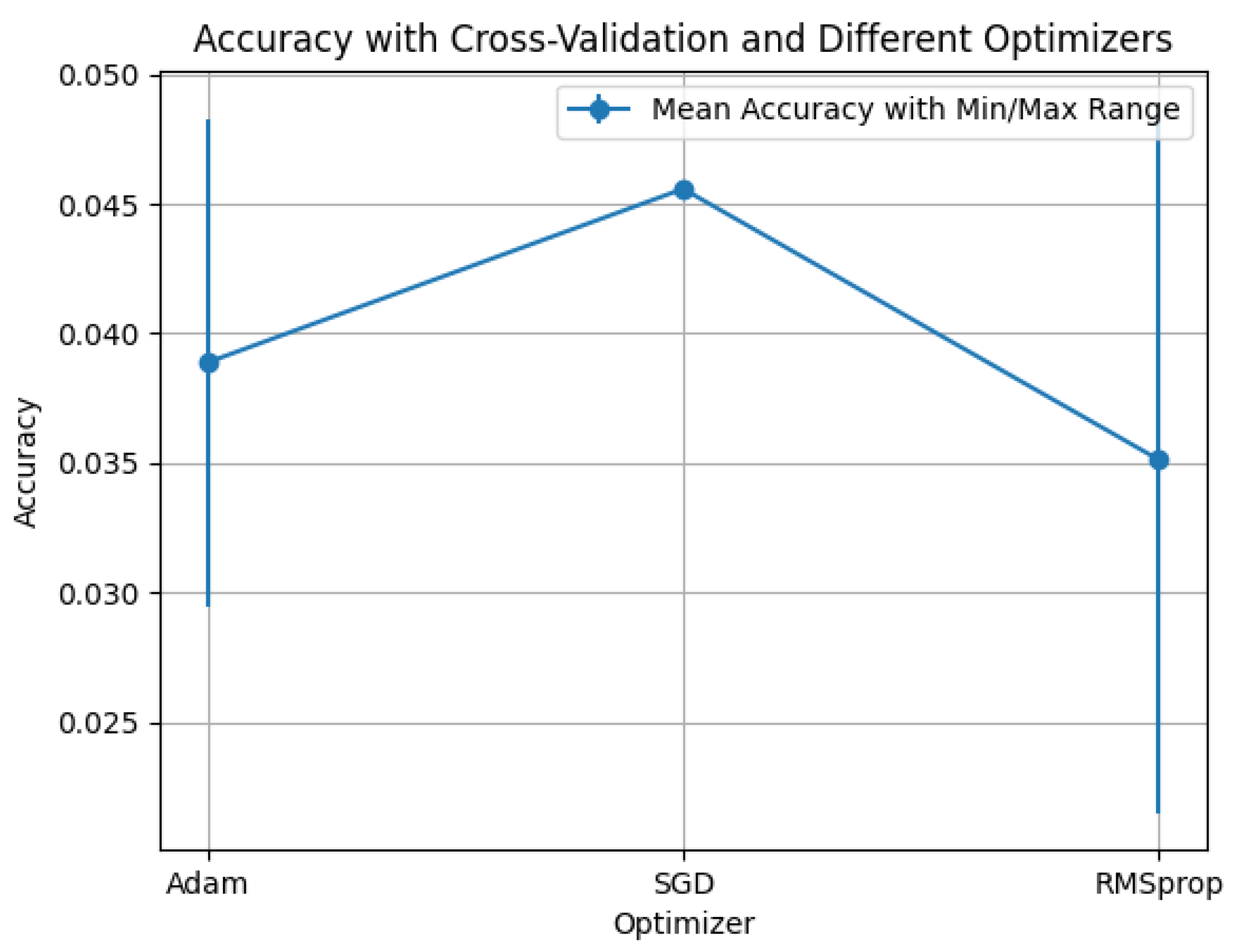

We evaluate the q-mixed propagation and summarize performance by optimizer for each activation. Plots report the mean accuracy with min–max error bars across the folds/seeds of our protocol.

Observations: Across

ReLU,

sigmoid, and

tanh (

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14),

RMSprop yields the best results,

Adam is intermediate, and

SGD is uniformly low. The strongest configuration for this operator is

ReLU+RMSprop (peak

), followed by

tanh+RMSprop (

) and

sigmoid+RMSprop (

). These trends suggest that normalized diffusion benefits from adaptive optimizers, with smoother non-linearities (tanh) competitive but not surpassing ReLU under our setting; sigmoid underperforms due to saturation.

Since is Hermitian with spectrum in , Property 15 implies and a gradual eigenvalue map , consistent with the modest variance observed across optimizers.

6.4. Random Walk Laplacian

Finally, we evaluate the Random Walk Laplacian:

and its

q-mixed propagation

. We summarize performance across activations (

ReLU,

sigmoid,

tanh) and optimizers (

Adam,

RMSprop,

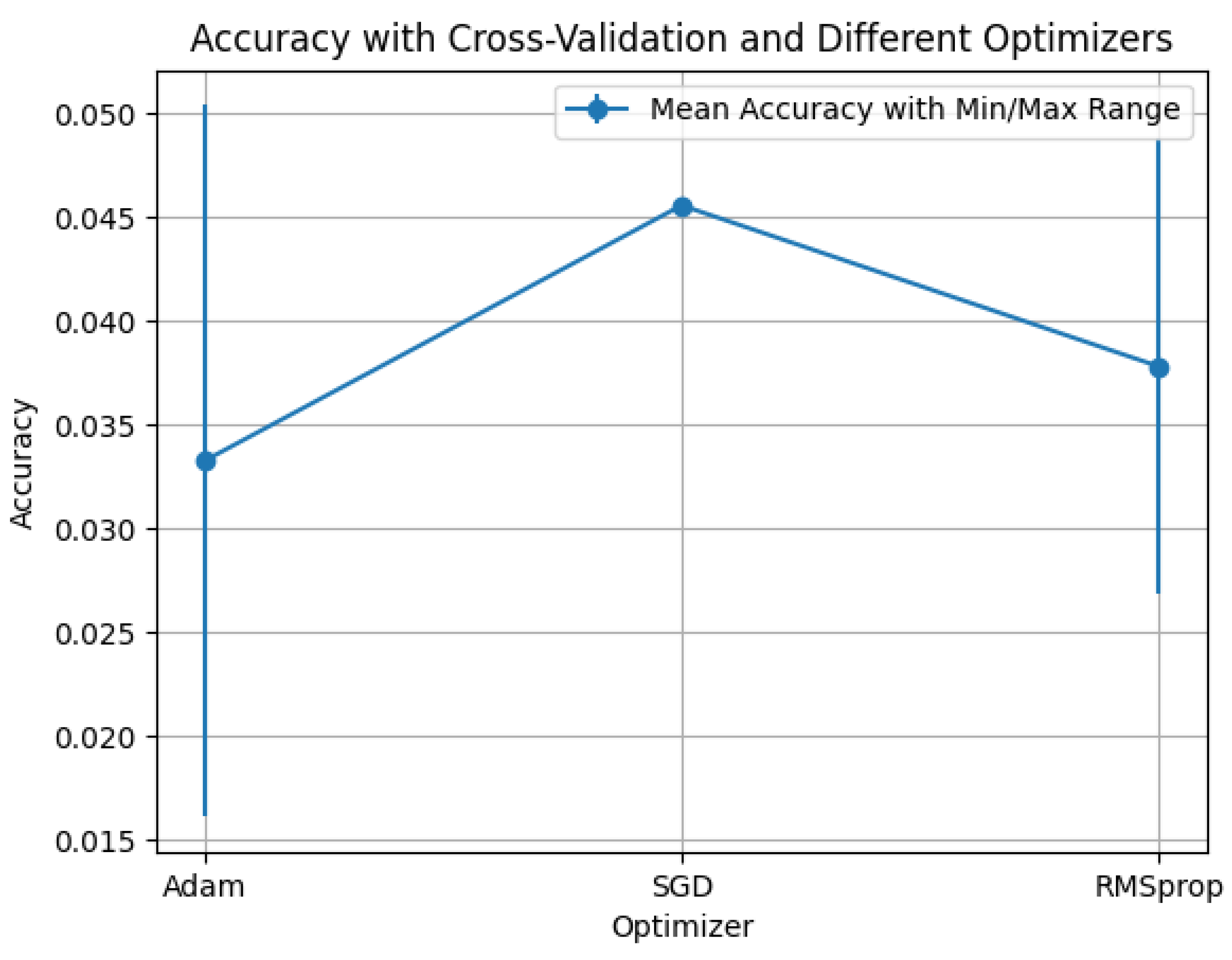

SGD); curves report mean accuracy with min–max error bars over folds/seeds.

Observations: Across

ReLU,

sigmoid, and

tanh (

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17), absolute accuracy is low (all values

) and the spread across optimizers is small.

SGD is marginally the best in all three panels (

–

), while

Adam and

RMSprop are slightly lower and exhibit larger variance (notably for RMSprop). This contrasts with the Hermitian operators, where adaptive optimizers clearly dominate, and indicates that the weaker normalization of the random-walk construction offers limited benefit for our setting.

Although generally non-symmetric, is row-stochastic, hence and the mixed operator has spectral radius at most 1; empirically, this yields stable but comparatively underpowered propagation.

6.5. Summary of Findings

Experimental results showed that:

For the incidence matrix, the Hermitian Laplacian consistently outperformed other variants, particularly when paired with ReLU and the Adam optimizer. The Hermitian Laplacian with imaginary part showed improved performance with ReLU and RMSprop. The Random Walk Laplacian demonstrated marginal improvements but was outperformed by the Hermitian variants. The Normalized Laplacian and Standard Laplacian performed well with RMSprop, especially when paired with tanh.

For the adjacency matrix, the Unnormalized Laplacian showed competitive performance, with tanh and sigmoid activation functions achieving the highest accuracy. The Normalized Laplacian and Random Walk Laplacian performed best with ReLU and SGD. The Hermitian Laplacian for adjacency, incorporating a complex phase term, showed consistent but lower performance across configurations.

Varying the value of q in the Hermitian Laplacian demonstrated significant improvements in performance across both the incidence and adjacency matrices. The optimal value of q led to better results for different variants, highlighting the importance of tuning this parameter to achieve the best model performance in different configurations.

We observed sharp drops in accuracy when the mixing parameter q crossed a threshold. This behavior is explained by the spectrum of : as q increases, eigenvalues move from the identity regime toward those of L. If the dataset’s structure (homophily level, hyperedge-size distribution, strength of directionality) is misaligned with L’s diffusion profile, small changes in q can shift eigenvalues across the effective passband of the first-order filter, causing abrupt performance changes. In such cases, the complex Hermitian variant whose imaginary component induces oscillatory propagation can further amplify mismatch via phase cancellations, especially when directionality is weak or noisy, leading to reduced accuracy compared to the real operators.

7. Discussion

The results presented in

Section 5 highlight the effectiveness of the proposed Directed Higher-Ordered Neural Network (HONN) across diverse benchmark datasets. HONN consistently outperformed or matched established baselines, including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs, Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNNs), Directed Graph-based Semi-Supervised Learning (DGSSL) [

17], and Gedi-hnn [

13].

A central factor in HONN’s success is its ability to encode both directionality and higher-order relationships through spectral Laplacians. By tuning the q-parameter, HONN balances local and global structural information, enabling adaptability across datasets of varying sparsity and density. For example, HONN achieved its highest accuracy on NTU-2012 (84%) with a global diffusion setting (), while smaller, sparser datasets such as Texas (87.4%) and Cornell (86.2%) benefited from more localized propagation (–). This confirms that dataset-specific tuning of q significantly improves stability and generalization.

7.1. General Performance

HONN’s performance across datasets demonstrates its adaptability to directed hypergraph structures. As shown in

Table 3, HONN achieved state-of-the-art accuracy on multiple datasets, with notable strengths in its stability across random splits.

Our analysis of Laplacian variants revealed clear trends: the Hermitian Laplacian was most effective for small-scale hypergraphs such as WebKB Texas and Cornell, where it mitigated performance variance and preserved local structural signals. The Normalized Laplacian performed best for larger and denser datasets such as Citeseer and NTU-2012, where smoothing aided in capturing global dependencies. The Complex Hermitian Laplacian showed potential for tasks requiring phase-aware propagation, though its performance was more sensitive to optimizer choice. These findings reinforce that spectral operator selection directly affects HONN’s learning efficiency.

While GCN surpassed HONN on Cora (81.5% vs. 71.5%), this result aligns with the dataset’s inherently pairwise structure, which favors models based on standard graph Laplacians. HONN, in contrast, is designed for expressive, multi-relational domains, which explains its superior performance on hypergraph benchmarks like WebKB Texas and Cornell. This suggests that HONN is particularly advantageous when higher-order and directional dependencies are prominent.

7.2. Stability and Generalization

One of HONN’s strongest attributes is its stability across heterogeneous graph structures. Unlike conventional models that operate under fixed spectral assumptions, HONN leverages flexible Laplacian formulations, enabling adaptation to dataset-specific properties. This was evident in Citeseer, where HONN (59.4%) outperformed DGSSL and HGNN despite the dataset’s noisy structure.

The ablation study on NTU-2012 further confirmed that activation choice interacts strongly with Laplacian selection: ReLU consistently yielded stable propagation with Hermitian operators, while tanh occasionally excelled with the Normalized Laplacian. These results highlight the importance of spectral–nonlinearity interplay in maintaining generalization.

Moreover, the q-sensitivity analysis established that low values favor localized learning on sparse datasets, while higher values are beneficial for dense relational structures. This adaptive mechanism provides HONN with a unique advantage in real-world applications where data connectivity is neither uniform nor fixed.

7.3. Comparison with Baseline Models

Compared with baseline models, HONN offers a clear advantage in capturing directed higher-order interactions. GCN remains strong on datasets with simple pairwise links but struggles with multi-entity relations that HONN naturally models via hyperedges. HGNN captures higher-order structures but lacks directionality, which limits its expressiveness. DGSSL incorporates direction but only in pairwise graphs, making it less effective for hypergraph tasks.

Our framework’s superiority over Gedi-hnn is attributed to the flexibility of the tunable q-parameter and the adaptable spectral Laplacian formulation. While Gedi-hnn provides competitive accuracy, particularly on the Citeseer dataset, its fixed-Laplacian approach limits its capacity to optimally diffuse features across varied hypergraph topologies. Furthermore, while the HCHA variants (Convolutional and Attention) demonstrate a significant advantage in raw classification accuracy on standard benchmarks like Cora and Citeseer, HONN’s consistent performance across diverse datasets underscores its superior generalization capability. The HCHA models’ strong performance on standard citation graphs contrasts with HONN’s dominance on the more specialized and challenging NTU-2012, Texas, and Cornell datasets.

Another baseline SigMaNet introduces a parameter-free

sign-magnetic Laplacian that yields a Hermitian, positive–semidefinite operator for directed and/or signed graphs, enabling standard spectral filtering (e.g., Chebyshev/GCN-style) with per-layer cost comparable to GCN,

[

13]. As a graph method, SigMaNet models pairwise edges without clique expansion, but it does not natively capture higher-order interactions. In our study, it serves as a strong graph–spectral baseline on citation benchmarks, whereas HONN targets directed hypergraphs via incidence-based node→edge→node propagation and adaptive spectral mixing over multiple Laplacians

through a learnable

q. This distinction-fixed single-operator on graphs versus adaptive multi-operator on higher-order structure explains why SigMaNet is competitive on homophilous pairwise datasets, while HONN provides consistent gains on datasets with pronounced directional, multi-way relations.

HONN bridges these gaps, achieving superior accuracy on NTU-2012, Texas, and Cornell, thereby validating the importance of integrating directionality into higher-order spectral learning.

These findings suggest that HONN is particularly suited to domains such as knowledge graphs, recommendation systems, and spatio-temporal networks, where interactions are inherently multi-relational and directional.

7.4. Limitations and Future Improvements

Despite its promising results, HONN has several limitations. First, the model introduces additional computational overhead compared to standard GCNs, due to the construction and manipulation of directed hypergraph Laplacians. While our experiments showed low per-epoch costs on moderate-scale datasets, scalability to web-scale graphs may require further optimization. Sparse approximations and distributed implementations are promising directions.

Second, HONN’s performance is sensitive to hyperparameter selection, particularly q-values and Laplacian choice. Automated tuning strategies, such as Bayesian optimization or meta-learning, could reduce this reliance on manual search.

Third, while HONN excels in higher-order relational settings, it underperforms on simpler datasets like Citeseer. We explicitly acknowledge that on pairwise, homophilous citation graphs such as Cora and Citeseer, a graph–spectral baseline (e.g., GCN) can outperform HONN. Our framework is designed for settings where directionality and higher-order relations matter; in such cases (NTU-2012 and WebKB subsets Texas/Cornell), HONN consistently performs strongly in our experiments. This pattern aligns with HONN’s operator design: when the underlying structure is effectively pairwise, graph-normalized spectra (

) are well matched; when relations are multi-way and directional, hypergraph operators (

or its complex variant) are more expressive. This points to the need for hybrid architectures that combine HONN’s spectral strengths with classical GCN components, offering robustness in both low- and high-complexity datasets. We plan to expand the work towards the Open Graph Benchmark (OBGs) [

41] in the future.

Finally, future work may explore architectural enhancements, such as attention-driven spectral modulation, contrastive spectral pretraining, integration of higher-ordered logic, and integration with spectral transformers, to further boost adaptability and efficiency. Improvements in handling highly sparse hypergraphs, where relationships are weakly connected, also remain a key challenge.

7.5. Application

Directed higher-order relations are ubiquitous beyond citation graphs, and HONN is designed for precisely these settings.

- (i)

Bioinformatics and systems biology: reaction pathways and metabolic networks couple enzyme→substrate→cofactor/product with intrinsic directionality; modeling hyperedges as reactions allows HONN to propagate along multi-molecular events without clique expansion.

- (ii)

Recommender systems and session analytics: user → session → item interactions are naturally many-to-one or one-to-many; directed hyperedges capture ordered co-occurrence and enable spectral diffusion that respects browsing direction.

- (iii)

Fraud/finance risk: entities → accounts → transactions form multi-actor, directed motifs; HONN can aggregate along these motifs to surface coordinated activity while controlling diffusion via q.

- (iv)

Supply chains and logistics: origin → route → destination flows are multi-way and directed; hypergraph propagation helps forecast disruptions across shared intermediates.

- (v)

Program analysis and software dependency: function → module → package graphs are higher-order and directional; HONN can diffuse signals through call/import hyperedges to prioritize fixes.

- (vi)

Knowledge graphs and multimodal events: events often bind multiple entities with roles (who-did-what-to-whom-where, time); directed hyperedges encode role-aware propagation.

HONN’s layer cost remains sparse and linear in the incidence size (), so training scales to large graphs; the mixing parameter offers a simple control to adapt the spectral regime to data constraints (local vs. global diffusion). Because is 1-Lipschitz, gradients are stable, which eases production training. Finally, choosing among yields interpretable behavior: normalized diffusion for pairwise-like structure, real Hermitian for higher-order directionality, and complex Hermitian when phase (cyclic/oscillatory effects) is meaningful.