Abstract

Under extreme operating conditions, the internal lubricating flow field of high-speed gear transmission systems exhibits a transient oil–gas multiphase flow, predominantly governed by cavitation-induced phase transitions and turbulent shear. This phenomenon involves complex mechanisms of nonlinear multi-physical coupling and energy dissipation. Traditional lubrication theories and single-phase flow simplified models show significant limitations in capturing microsecond-scale flow features, dynamic interface evolution, and turbulence modulation mechanisms. To address these challenges, this study developed a cross-scale coupled numerical framework based on the Lattice Boltzmann method and large eddy simulation (LBM-LES). By incorporating an adaptive time relaxation algorithm, the framework effectively enhances the computational accuracy and stability for high-speed rotational flow fields, enabling the precise characterization of lubricant splashing, distribution, and its interaction with air. The research systematically reveals the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the internal flow field within the gearbox and focuses on analyzing the nonlinear regulatory effect of baffle geometric parameters on the system’s energy transport and dissipation characteristics. Numerical results indicate that the baffle structure significantly influences the spatial distribution of the vorticity field and turbulence intensity by reconstructing the shear layer topology. Low-profile baffles optimize the energy transfer pathway, effectively reducing the flow enthalpy, whereas excessively tall baffles induce strong secondary recirculation flows, exacerbating vortex-induced energy losses. Simultaneously, appropriately increasing the spacing between double baffles helps enhance global lubricant transport efficiency and suppresses unsteady dissipation caused by localized momentum accumulation. Furthermore, the geometrically optimized double-baffle configuration can achieve synergistic improvements in lubrication performance, oil film stability, and system energy efficiency by guiding the main shear flow and mitigating localized high-momentum impacts. This study provides crucial theoretical foundations and design guidelines for developing the next generation of theory-driven, energy-efficient lubrication design strategies for gear transmissions.

1. Introduction

Gear transmission systems represent the core power transmission components in contemporary high-end mechanical equipment. Achieving a synergistic optimization of their lubrication behavior and thermodynamic performance poses a series of critical technical challenges, particularly under extreme operational conditions involving high loads and high rotational speeds [1,2,3]. Accumulated experimental evidence has demonstrated that intense turbulent shear stresses generated during high-speed gear meshing can trigger cavitation-induced phase transitions within the lubricating oil film. These transitions give rise to transient oil–gas two-phase flow fields characterized by unsteady pulsation and spatial–temporal variability. Such complex multiphase interactions not only compromise the efficiency of lubricant transport but also promote surface failure mechanisms, including micropitting, scuffing, and localized thermal welding [4,5,6]. As a result, gaining a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic distribution and evolution of internal flow fields within gearboxes is of paramount importance for improving transmission efficiency, thermal stability, and overall operational reliability.

Traditional elastohydrodynamic lubrication theory, which is based on steady-state assumptions and idealized boundary conditions, proves inadequate for capturing the transient rupture and reformation dynamics of lubricating films subjected to high-speed and variable loading conditions. Experimental investigations into such phenomena remain constrained by the inherently limited optical accessibility of enclosed gearbox architectures, which restricts in situ flow visualization. Existing particle image velocimetry techniques lack the temporal resolution necessary to accurately track lubricant splash trajectories and resolve spatial distributions at microsecond timescales, thereby impeding quantitative assessment of phenomena such as air barrier formation and disruption [7,8]. Although computational modeling offers a valuable supplement to physical experiments, currently available interface tracking algorithms remain insufficient for reliably simulating the dynamic evolution of complex oil–gas interfaces. This modeling limitation presents a substantial obstacle to solving key engineering challenges [9,10,11]. Consequently, the development of high-fidelity flow field characterization techniques and multiparameter-coupled lubrication models has become essential. Advancements in this area are expected to facilitate a deeper mechanistic understanding of energy dissipation processes under complex operational conditions, offering critical theoretical support for precision lubrication design and accurate service life prediction in gear transmission systems.

In response to the aforementioned key research challenges, numerous scholars have conducted comprehensive and systematic studies by integrating experimental techniques with advanced numerical simulation methods. Handschuh et al. [12] quantitatively analyzed the no-load power losses associated with spur gears, helical gears, and bevel gears through carefully designed experiments, thereby revealing the differentiated impacts that various gear structures impose on overall transmission efficiency and power dissipation. Changenet et al. [13] designed and constructed a highly flexible, adjustable test bench, and their investigations demonstrated that the strategic addition of side plates could significantly mitigate oil churning losses. Furthermore, they found that variations in axial gaps exert a more pronounced influence on loss reduction than changes in radial gaps. Meanwhile, Arisawa et al. [14,15] successfully achieved a substantial reduction—over 60%—in aerodynamic windage losses by developing an optimized oil guide cover tailored specifically for aviation-grade bevel gear assemblies. Hildebrand et al. [16] carried out a detailed and in-depth analysis of the internal oil flow field within a spur gearbox equipped with flow-guiding plates. Their study identified the relative contributions of different gear tooth surface regions to oil churning resistance torque and provided a rational explanation for the coupling mechanism between the pressure gradient acting along the tooth flanks and the localized shear forces present within the meshing zone. Liu et al. [17,18] employed the Moving Particle Semi-implicit (MPS) numerical method to simulate the lubrication characteristics and performance of engineering gear transmission systems. Their results demonstrated that this method is particularly advantageous in preserving intricate structural details of real gearboxes and significantly enhancing computational efficiency, as confirmed by comparisons with high-speed photographic imaging. Atencio et al. [19] applied the LBM to analyze oil flow behavior in vertically arranged gearboxes, and their experiments provided strong validation of the method’s high accuracy and reliability in capturing and tracking complex multiphase flow interface phenomena.

Current research focuses on the churning loss for gearbox lubrication, but there remains a significant theoretical gap in the study of the energy transfer mechanism and baffle control optimization of oil–gas two-phase systems [20,21,22]. Although the interaction between lubricating oil and air significantly affects the load-bearing characteristics of the oil film, existing numerical models generally adopt a single-phase flow simplification: they reduce the complex gas–liquid interactions to a single medium viscous flow, systematically neglecting the control mechanisms of turbulent energy dissipation [23,24,25]. While this simplification improves computational efficiency, it distorts key physical processes—centrifugal splashing of lubricating oil is equated to steady-state shear flow, and the oscillation of gas cavities and the evolution of secondary vortices in the tooth gap are excluded from the governing equations. More notably, traditional finite volume methods face methodological limitations when dealing with dynamic meshing boundaries: the micron-level meshing gaps require grid division to have both local refinement accuracy and global dynamic adaptability, while the strong coupling demands of rotating boundaries and phase interface tracking lead to exponential increases in computational complexity [26,27]. In addition, prior studies have not established a systematic investigation into the quantitative relationships between baffle geometric parameters (e.g., height, gap ratio) and lubrication performance metrics [28]. This theoretical deficiency results in a lack of multiphase flow dynamics criteria in lubrication design, making it difficult to quantify how baffle structures regulate the fragmentation threshold of the oil–gas interface [29]. The Lattice Boltzmann method (LBM), due to its mesoscopic particle dynamics nature, is inherently suitable for capturing transient multiphase flow phenomena such as the dynamic evolution of gas–liquid interfaces and cavitation phase transitions, and can handle the dynamic boundaries of gear meshing areas without the need for complex grid reconstruction. Meanwhile, LES directly resolves the large-scale ordered structures of dominant turbulent kinetic energy through sub-grid stress models, accurately characterizing non-stationary turbulent features such as shear layer instability and vortex shedding at high Reynolds numbers [30]. The synergy of these two methods achieves seamless transition from mesoscopic collision mechanisms to macroscopic turbulent transport, breaking through the computational bottlenecks of traditional methods in dynamic grid adaptability and multiphase interface tracking, providing unprecedented simulation accuracy and physical insight for revealing the regulatory mechanisms of impeller geometric parameters on the threshold of oil film fragmentation and energy dissipation pathways.

This paper develops a refined multiphase coupled transport dynamics model grounded in an LBM–LES cross-scale coupling framework. To enhance computational efficiency and accuracy in simulating high-speed rotating flow fields, an adaptive time relaxation algorithm is introduced for iterative optimization and stability control. A comprehensive dynamic evolution model of the internal flow field is constructed under the coupled influence of gas, liquid, and solid phases, enabling an in-depth analysis of the spatial–temporal evolution characteristics and interaction mechanisms within the multiphase system. The model further reveals the complex nonlinear regulation mechanisms of turbulence energy distribution, governed by the geometric parameters—such as height and spacing—of the internal baffle structures.

The organizational structure of the paper is as follows: In Section 2, the mathematical analysis model for the high-speed gear lubrication flow field based on the LBM-LES method is introduced. In Section 3, a numerical model of the lubricating oil film in high-speed gears with baffles is presented. In Section 4, the relationship between baffle parameters and oil distribution is analyzed, and corresponding optimization strategies are proposed. In Section 5, the main conclusions of the study are summarized.

2. Mathematical Analysis Model of High-Speed Gear Lubricating Oil Field

2.1. Mathematical Model of Gear Lubrication Based on LBM

The lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) is a numerical simulation framework rooted in mesoscopic particle dynamics, which reconstructs macroscopic fluid behavior by evolving the particle distribution function in discrete velocity space while inherently preserving microscopic collision mechanisms [31]. The governing equation for the distribution function evolution is the Lattice Boltzmann equation [32].

In the equation, fi(x,t) represents the density distribution function of the i-th component of the discrete velocity space, located at the discrete spatial position x and at time t, ξ is the molecular velocity vector, F(x,t) is the external force term, and Ωi is the collision operator. The right side of Equation (1) represents the local collision operator, while the left side indicates convective transport.

The LBM has been widely applied in various fields of fluid dynamics. D3Q19 and D3Q27 are commonly used models for establishing three-dimensional simulations. The D3Q27 model uses 27 discrete velocities in three-dimensional space. Compared to the D3Q15 model, D3Q27 captures details such as velocity gradients within the fluid more accurately by introducing diagonal velocity components, allowing for a more precise analysis of three-dimensional vortex structures and non-equilibrium stresses, which is particularly important for addressing complex fluid dynamics problems. The velocity configuration of D3Q27 is as follows:

The lattice speed is calculated using c = Δx/Δt, and the macroscopic density and momentum can be computed through the zeroth and first moments of the distribution function.

where u represents the macroscopic velocity of the fluid, ρ is the fluid density, and the pressure p is calculated through the state equation.

where cs represents the lattice speed of sound, which is a constant in the D3Q27 model.

The equilibrium distribution function is generally represented by the following macroscopic variables.

where i represents the various coordinate directions, adhering to the summation convention, α and β represent the various coordinate directions, adhering to the summation convention, and wi denotes the weights under the D3Q27 model.

To ensure the stability of the solution at high Reynolds numbers, the cumulant model is used for Ωi, where the density distribution function f is replaced by cumulant variables obtained from the Laplace transform; the cumulant quantities are defined in the frequency domain [33].

where F(Ξ) represents the generating function obtained by mapping the density distribution function f(ξ) in velocity space ξ to frequency space Ξ via the Laplace transform. The cumulant kαβγ, where α, β, and γ denote the coordinate directions, is calculated as a higher-order mixed partial derivative of the log-generating function. Ξ, Y, and Z are wavenumber variables in frequency space.

Each cumulant of order α + β + γ satisfies Galilean invariance. The cumulant collision process is represented, where ωαβγ denotes the relaxation rate, and represents the cumulant in the equilibrium state.

2.2. LBM-LES Coupled Model

The large eddy simulation (LES) is an advanced turbulence simulation method. Through the direct numerical solution of the instantaneous Navier–Stokes equations for all large-scale vortices larger than the filtering width, LES can precisely capture the dominant structures and unsteady characteristics of the flow field. For the small-scale vortices that are filtered out and their associated effects, they are approximately simulated through a mathematical relationship known as the sub-grid scale model [34,35]. The LES constructs a multi-scale analytical framework for turbulence through a subgrid stress model (SGS), directly solving for the large-scale quasi-ordered structures that dominate turbulent kinetic energy, while employing statistical closure modeling for small-scale fluctuations [35,36]. This strategy, when coupled with the LBM, highlights its technical advantages: the mesoscopic particle evolution mechanism of LBM naturally aligns with the time-stepping solution characteristics of LES, allowing for precise capture of microsecond-scale physical processes such as sudden changes in pressure gradients of transient squeezed flows in the gear meshing area and the unsteady shedding of leakage vortices at the tooth tips. The dynamic Smagorinsky subgrid model dynamically calibrates the eddy viscosity coefficient through local turbulent kinetic energy balance, and its synergistic effect with the nonlinear characteristics of the LBM collision operator significantly enhances the predictive accuracy of turbulent kinetic energy transport in the wall boundary layer and secondary flow separation regions [37,38,39,40].

Based on this, this paper adopts a coupling framework of LES and LBM, in which the subgrid-scale eddy viscosity vsgs calculated from the turbulence model [39,40] is incorporated into the LBM framework through the effective viscosity ν to determine the local relaxation time τ. The total kinematic viscosity is defined as the sum of the molecular and subgrid-scale components, and the corresponding LBM relation is expressed as:

Here, cs is the lattice speed of sound, δt is the time step, and ν represents the total viscosity incorporating both molecular and turbulent effects. In this way, the turbulence-resolving capacity of LES is embedded within the LBM solver via dynamic adjustment of τ at each lattice node, enabling scale-consistent representation of eddy viscosity effects.

This study specifically uses the wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) subgrid model to compute vsgs and close the turbulent stress. The WALE formulation is given by:

In the equation: vsgs is the subgrid-scale motion viscosity; Sαβ and Gαβ are the strain rate tensors at the resolved scale; ui is the fluid velocity in the i direction; xi is the fluid coordinate in the i direction; Δ is the filter width in LES; the constant Cw is typically taken as 0.325; τiαβ is the subgrid stress closure tensor used to construct the subgrid-scale stress term. The resulting vsgs is added to the molecular viscosity and substituted into Equation (12) to determine the relaxation time used in LBM, thereby realizing a consistent coupling between turbulence modeling and mesoscopic fluid evolution.

Considering that the numerical solution of boundary layer turbulence requires a large number of grid cells, wall functions can be used to solve for the near-wall boundary layer velocity. During the LBM solving process, the minimum size of the boundary layer grid can be directly set, thereby determining the actual y+ value used in the calculations and enabling a reasonable solution for the boundary layer velocity.

2.3. Numerical Simulation Based on LBM-LES Coupling

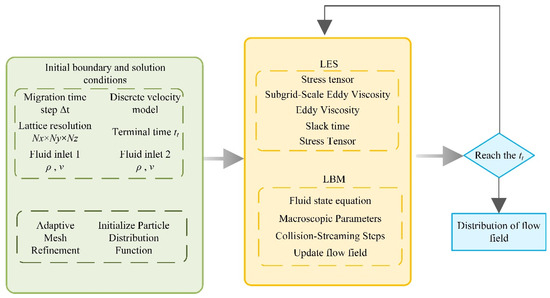

In this study, based on the simulation experiments of gear oil lubrication, a multi-physical field coupling numerical solution system has been established, aiming to achieve efficient and accurate simulation of fluid dynamics behavior. This method is based on a previously constructed mathematical model and integrates the LBM with LES, as shown in Figure 1. The entire simulation process begins by setting key parameters of the computational domain, such as lattice size, output interval, and fluid inlet conditions, to ensure the accuracy and scope of the solution [41,42,43,44]. Additionally, an adaptive lattice sizing algorithm is incorporated to dynamically refine grid dimensions based on localized flow gradients, enhancing resolution in critical regions while maintaining computational efficiency.

Figure 1.

Coupling calculation flowchart of the LBM-LES coupling method.

This study employs a mesoscopic LBM to construct the fluid dynamics solution framework, achieving high-precision simulation of flow field evolution through a two-stage iterative mechanism. The process begins by specifying the initial boundary and solution conditions, which include the migration time step Δt, the discrete velocity model, and the lattice resolution (Nx × Ny × Nz). The fluid inlet conditions at two separate inlet boundaries (ρ, v) are also prescribed to accurately represent the mass and momentum inflow characteristics. Adaptive mesh refinement techniques are incorporated to ensure computational resource efficiency by dynamically adjusting the grid resolution in regions with significant velocity or pressure gradients. The particle distribution function is initialized to establish the mesoscopic kinetic description of the fluid. The core of the simulation is structured around a two-stage iterative algorithm. In the first stage, the LBM is employed to resolve the fluid state equations, calculate macroscopic parameters, and perform collision-streaming steps to update the flow field [45,46,47]. In the second stage, the LES module refines the solution by resolving the large-scale vortex dynamics and subgrid-scale eddy viscosity effects, employing a dynamic calibration of the eddy viscosity coefficient to ensure the closure of the subgrid stress tensors [48,49,50]. This hybrid approach leverages the mesoscopic–macroscopic coupling capabilities of LBM with the high-order turbulence resolution of LES. The computational loop proceeds iteratively, continuously updating the flow field at each time step and monitoring the alignment with the prescribed terminal time. Once the convergence criteria are met and the final state is reached, the simulation outputs a comprehensive dataset detailing the distribution of the flow field. This dataset includes temporally and spatially continuous information on key flow parameters such as velocity fields, pressure distributions, Reynolds stresses, and characteristic vortex structures [51,52,53].

In the context of turbulent analysis, a high-order turbulence dynamics model is constructed using the LES method. This model is based on spatial filtering theory, separating resolvable scale vortex structures from subgrid-scale fluctuations, with a focus on analyzing the evolution of large-scale vortices that dominate turbulent kinetic energy levels [54,55,56]. The technical implementation path includes the closure of subgrid stress tensors and dynamic calibration of the eddy viscosity coefficient, which is further embedded into the LBM framework via the viscosity–relaxation time relation. The simulation system employs a strict time-stepping control strategy, continuously monitoring the alignment between the computational process and preset termination conditions, and outputs a multidimensional flow field dataset when convergence criteria are met. This dataset includes characteristic quantities such as turbulent fluctuation energy spectra, Reynolds stress tensors, and vortex identification parameters. This multi-scale coupled numerical method system provides a systematic analytical tool for revealing the turbulence modulation mechanisms in the lubrication process of gear oil [57,58,59].

3. Numerical Model of High-Speed Gear Lubrication Oil Field

3.1. Geometric Model and Numerical Model

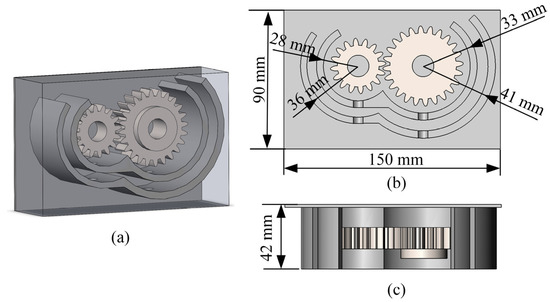

The real gearbox system has complex structural characteristics, and its simplification method must be constructed based on retaining the core mechanism of oil dynamic migration, in order to accurately simulate the flow field distribution in the gear meshing area and its surrounding profile while reducing the computational load [60]. The geometric model of the gearbox is designed as a simplified rectangular shape, with overall dimensions of 150 mm × 90 mm × 42 mm, and a boundary distance of 10 mm from the nearest point of the gear, with a width of 20 mm. The basic parameter is listed: number of teeth: small gear: 16 teeth, large gear: 24 teeth; Module: 2 mm; pressure angle: 20°; profile shift coefficient: 0 (standard involute profile); gear width: 20 mm. This design retains the geometric features of the gears while reducing the computational load and optimizing the simulation accuracy of the flow field distribution. The bottom of the baffle is designed with two through holes with a radius of 8 mm to allow the lubrication oil to flow. The simplified gearbox model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geometric model. (a) Three-dimensional gearbox structure diagram. (b) Front view. (c) Top view.

The numerical model is based on the moving particle semi-implicit (MPS) and achieves precise analysis of the dynamic lubrication behavior of the gear system through an automatic grid partitioning technique using an octagonal lattice [61,62,63,64]. The model employs a layered discretization strategy: a locally refined mesh is constructed in the boundary layer of the engagement area, with a minimum element size of 0.02 mm. The total number of lattice elements used in the final simulation is 923,463.

3.2. Model Boundary Conditions and Initial Conditions

Based on the numerical model, the gear oil stirring process can be observed within a limited physical space, where the boundary conditions of the gearbox and the basic parameters of the gas–liquid fluid medium are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic parameters of the gearbox.

In this study, the gear is set as a rotating wall, while the inner wall of the gearbox is a no-slip fixed wall of the fluid domain. The submerged area of the gear is initialized as the oil phase (volume fraction > 0.99), is set to represent a fully oil-submerged region, which is consistent with typical gearbox lubrication conditions. The remaining area is defined as the gas phase. A dynamic layered unstructured mesh technique is employed for the rotating components to dynamically track the oil film morphology in the gear contact area. The initial pressure field of the model is set to standard atmospheric pressure (101,325 Pa), and an angular velocity boundary condition of ω = 3600 rpm is applied to the rotating wall of the small gear, coupled with the effect of the gravitational field (g = 9.81 m/s2). The total simulation time is 0.2 s, with a time step of Δt = 2 × 10−5 s. The solver used an adaptive time-stepping strategy to maintain numerical stability. The CFL condition is enforced to be below 0.5.

3.3. Lattice Independence Verification

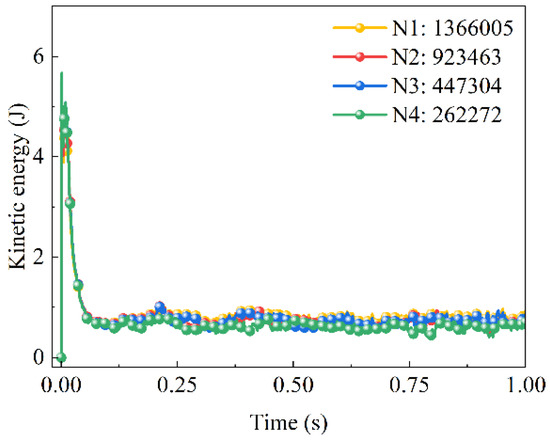

In the Lagrangian particle framework, lattice resolution has a decisive impact on the computational results. The adaptive particle refinement mechanism based on the LBM can capture complex flow features through dynamic densification while avoiding computational redundancy caused by globally high density [65,66,67,68,69,70]. An excessively high initial lattice density significantly increases CPU memory usage, while a sparse distribution can lead to distortion of important physical fields such as vortex structures [69,70]. In this paper, the number of fluid domain lattices of N1 = 262,272, N2 = 447,304, N3 = 923,463, and N4 = 1,366,005 are selected. The corresponding fluid kinetic energy is shown in Figure 3. It can be observed that when the number of lattice elements reaches N2, the relative error remains relatively large. It is not until the lattice number reaches N3 that the relative error meets the required criteria for grid independence. This modeling framework effectively balances computational accuracy and efficiency, providing a reliable numerical experimental platform for the study of lubrication dynamics in gearboxes. For example, with a mesh number of N3, a complete calculation on a single Intel Core i7-12700K CPU workstation took about 48 h, mainly due to the detailed gear meshing computations. Using domain decomposition and 10 threads, the time can be reduced to around 12 h.

Figure 3.

Verification of lattice independence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution Mechanism of Lubricating Oil in High-Speed Gearbox

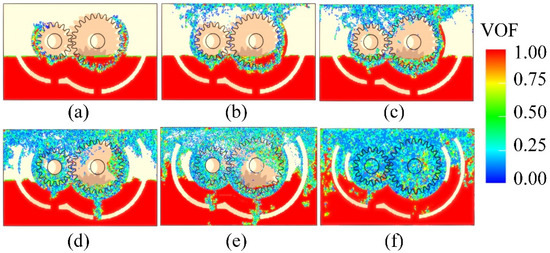

In response to the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of the flow field in the gearbox lubrication system, this study selected an input shaft speed of ω = 3600 rpm (counterclockwise direction) as the baseline condition for numerical simulation, systematically analyzing the dynamic characteristics of the liquid phase volume fraction within the gearbox over time. Through numerical simulation, the profile of the liquid phase volume fraction as it changes over time was obtained, as shown in Figure 4. The volume fraction contours are reconstructed from the LBM particle distribution functions for visualization purposes, representing the oil–gas interface evolution. Each subplot corresponds to the fluid distribution state at different time points, providing an initial understanding of the complex flow field behavior of the lubrication system during dynamic operation.

Figure 4.

The volume of fluid (VOF) diagram of the flow field. (a) t = 0.002 s; (b) t = 0.012 s; (c) t = 0.018 s; (d) t = 0.04 s; (e) t = 0.12 s; (f) t = 0.2 s.

Figure 4a illustrates the fluid distribution characteristics during the initial operational phase of the gear system. At this stage, a portion of the lubricating oil adheres to the lower surface of the gear due to centrifugal forces. Simultaneously, a small volume of air flows toward the overflow hole located at the center of the gear’s bottom. This interaction initiates the formation of a boundary interface between the fluid and the air. As shown in Figure 4b, with the progression of time, the fluid adhering to the lower gear surface is thrown upward by rotational motion. It subsequently falls back into the gear meshing area under the influence of gravity. Meanwhile, the fluid at the end face of the large gear begins to mix with the surrounding air. As a result, the uniformity of the fluid distribution gradually deteriorates. This observation signifies the onset of nonlinear dynamic behavior in the flow field. Figure 4c–e further depict the increasingly complex nature of fluid distribution. The lubricating oil lifted by both the small and large gears converges in the central region, producing a distinct impact phenomenon. Following this, the oil spreads upward toward the top of the gearbox, driven by both rotational forces and inertia. Concurrently, the airflow passing through the internal baffle shows a tendency toward horizontal diffusion, moving in the direction of the second through-hole. Figure 4f presents the final, stabilized state of the lubrication system during dynamic operation. At this point, the distribution of lubricating oil at both the gear tooth tips and roots is uniform and sufficient, ensuring effective lubrication in the gear meshing region. Additionally, the degree of fluid–air mixing within the baffle gap is significantly higher than in earlier stages. The flow field exhibits enhanced stability, indicating that the lubrication system has reached a state of dynamic equilibrium under the given operating conditions. In conclusion, this study elucidates the evolution of nonlinear dynamic characteristics within the gearbox lubrication system. The findings, obtained through numerical simulation, offer a theoretical foundation for the future optimization of lubrication system design.

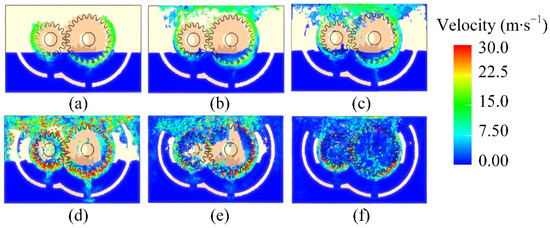

Figure 5 presents the velocity distribution at various time points in a gear transmission system operating under dual baffle conditions. Figure 5a illustrates the velocity distribution characteristics during the initial phase of gear operation. At this stage, the rotation of the gear agitates the lubricating oil. Due to the shear force, the area where the gear touches the inner wall of the housing exhibits a relatively high flow rate. Instead, the fluid speed decreases in a gradual manner from the contact surface to the outer edge of the gear.

Figure 5.

Velocity field distribution of the flow field. (a) t = 0.002 s; (b) t = 0.012 s; (c) t = 0.018 s; (d) t = 0.04 s; (e) t = 0.12 s; (f) t = 0.2 s.

Simultaneously, a low-velocity fluid region is observed at the bottom edge of the gear. This indicates that the fluid in this region is partially affected by rotational forces, whereas other surrounding areas remain nearly stationary. As shown in Figure 5b, continued gear rotation lifts the low-velocity fluid upward. The lubricating oil is driven along the curved inner wall toward the top of the gearbox by centrifugal force. At the wall junction, the fluid splashes outward due to kinetic energy dissipation. This stage signifies that the influence of gear rotation on the fluid is becoming more pronounced, and the flow field begins to develop a dynamic distribution pattern. Figure 5c,d further demonstrate a notable increase in overall fluid velocity within the gearbox. In particular, the fluid velocity in the gear meshing area is significantly higher than in other regions. This is attributed to the gear’s rotational motion, which actively drives the surrounding fluid. Moreover, the meshing and disengaging actions of the gear teeth cause localized acceleration and deceleration, resulting in the formation of high-velocity flows in the meshing zone.

In the upper section of the gear, the fluid is propelled outward from the center at high velocity due to the influence of centrifugal force. Conversely, the fluid in the gap between the baffles maintains a low flow velocity, constrained by the structural obstruction of the baffles. During this stage, the geometric configuration and surface roughness of the gear teeth begin to influence the flow pattern. These factors contribute to the formation of vortices in localized regions of the flow field. Figure 5e,f depict a subsequent decrease in the overall velocity within the fluid domain. The system gradually approaches a dynamically stable equilibrium state.

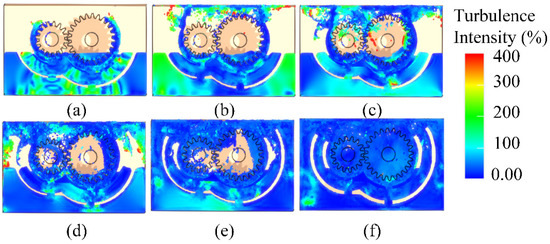

During this process, the geometric shape and surface roughness of the gear teeth significantly influence the fluid flow pattern. These factors contribute to the formation of vortices in specific regions of the gearbox. Figure 6 illustrates the temporal variation in turbulence intensity within the gearbox. Figure 6a shows the distribution of turbulence intensity in the initial phase of gear rotation, during which the rotation of the gear initiates fluid motion. However, due to the low initial kinetic energy, the overall turbulence intensity remains weak. Despite this, noticeable turbulence fluctuations occur in the regions inside and outside the baffle. These fluctuations are likely caused by the shear effect at the baffle edge and localized turbulence generated by the interaction between the fluid and the baffle structure.

Figure 6.

Distribution of turbulence intensity in the flow field. (a) t = 0.002 s; (b) t = 0.012 s; (c) t = 0.018 s; (d) t = 0.04 s; (e) t = 0.12 s; (f) t = 0.2 s.

The turbulence characteristics observed at this stage suggest that although the fluid flow is relatively stable during the early rotation of the gear, the presence of the baffle significantly disrupts the flow field stability. As shown in Figure 6b, continued gear rotation enhances the interaction between the gear and the inner wall of the casing. This interaction leads to a marked increase in turbulence intensity in the upper region of the gearbox. The phenomenon can be attributed to the combined effects of centrifugal forces generated by gear rotation and the constraints imposed by the casing walls. These conditions result in the formation of a strong shear layer in the upper region, thereby triggering turbulence. Simultaneously, turbulent fluctuations in the lower part of the gearbox become concentrated on both sides of the external baffle. Figure 6c,d further demonstrate a pronounced increase in turbulence intensity on both sides of the gearbox. In contrast, the turbulence intensity below the oil level decreases, exhibiting primarily periodic fluctuations centered around the through-hole in the baffle. The vertical motion of the fluid is constrained by the baffle’s geometry, especially its through-hole, leading to an uneven horizontal distribution of turbulence intensity. Figure 6e,f show a reduction in overall turbulence intensity, indicating that the system is gradually approaching a dynamically stable state. As the gear continues to rotate, the kinetic energy of the fluid dissipates progressively, resulting in reduced turbulence. The flow field characteristics at this stage indicate that the gearbox lubrication system can maintain a relatively stable turbulent regime during extended operation. This ensures a consistent lubrication environment for gear transmission.

The observed evolutionary process confirms that the baffle structure plays a regulatory role in shaping the flow field distribution. Moreover, its geometric configuration exerts a significant influence on the generation and development of turbulence. These findings provide a theoretical foundation for understanding flow behavior in gearbox lubrication systems. They also offer practical guidance for optimizing gearbox structural design and enhancing lubrication performance.

4.2. Mechanism of Influence of Baffle Geometric Parameters

The influence of baffles on fluid flow involves highly intricate fluid dynamic mechanisms. Variations in their geometric parameters can result in substantial reconstructions of the internal flow field. Moreover, the dimensions of the baffle not only impact the degree of local flow confinement but may also induce the development and evolution of turbulent structures. These turbulent changes, in turn, can significantly alter the mixing behavior and distribution characteristics within the boundary layer. Consequently, in order to effectively reduce energy consumption throughout the gear transmission process, it is of critical importance to carry out a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the regulatory effects imposed by baffle geometry. Such investigations can provide essential insights into how geometric modifications influence flow organization and turbulence modulation within the lubrication system.

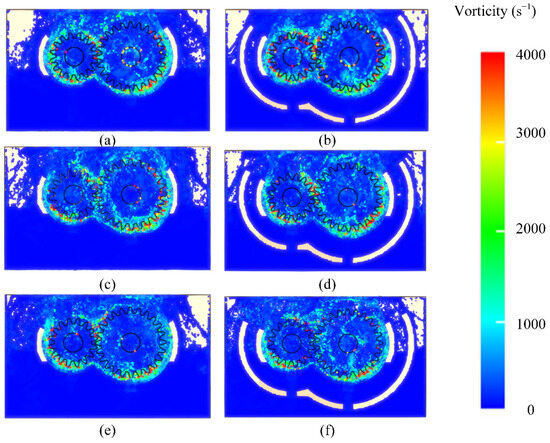

Figure 7 presents the steady-state contour maps of the vorticity distribution within the internal flow field of the gearbox under different baffle configurations at time point t = 0.5 s. In Figure 7a,b, Figure 7c,d and Figure 7e,f, the angles between the cutoff end face of the baffle and the horizontal oil surface are 24°, 30°, and 36°, respectively. Throughout all three cases, the gap between the two baffles remains constant.

Figure 7.

Steady-state vorticity field cloud maps under different baffle conditions. (a) Single baffle at 36°; (b) Double baffles at 36°; (c) Single baffle at 30°; (d) Double baffles at 30°; (e) Single baffle at 24°; (f) Double baffles at 24°.

The results indicate that under these configurations, regions of high vorticity consistently appear in the boundary layer separation zone submerged in oil, as well as within the shear band located at the entrance of the gear meshing area. This observation suggests that the presence of the baffle exerts a significant influence on the shear behavior of the fluid, thereby promoting the localized concentration of vorticity. As the baffle angle decreases, the overall vorticity intensity within the flow field exhibits a noticeable downward trend. This reduction can be attributed to the enhanced confinement effect imposed by the smaller baffle angle, which suppresses both the generation and the further development of vortical structures. Furthermore, the center of vorticity within the gear meshing region gradually shifts upward with decreasing baffle angle. This upward shift indicates that changes in baffle geometry have a substantial impact on energy dissipation processes occurring within the meshing zone. By comparing Figure 7a–f, it can be observed that the fluid distribution under the double-baffle configuration is significantly more concentrated than that under the single-baffle configuration. In the case of a single baffle plate, the lubrication fluid tends to splash outward after joining at the top of the gear, resulting in a more dispersed vorticity distribution throughout the flow field. In the double-baffle arrangement, the fluid is mainly concentrated in the upper region near the outer baffle, which leads to a more local and concentrated vorticity distribution. This evident difference demonstrates that the double-baffle configuration effectively suppresses chaotic fluid motion by constraining the possible flow paths. As a result, the overall structure of the flow field is optimized. Furthermore, the angle between the cutoff end face of the baffle and the horizontal oil surface, along with variations in baffle height, exerts a substantial influence on the spatial distribution of vorticity within the flow field.

By appropriately adjusting the geometric parameters of the baffle structure, it is possible to optimize the internal flow organization. Such modifications help in reducing the irregular and chaotic motion of the fluid, thereby offering a theoretical foundation for minimizing oil churning losses in the gearbox system.

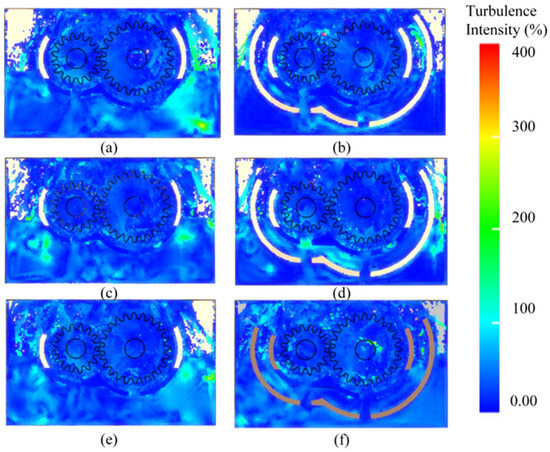

Figure 8 presents the steady-state contour maps of turbulence intensity distribution within the internal flow field of the gearbox under various baffle configurations. Under the single-baffle condition, regions of high turbulent kinetic energy are predominantly concentrated in the recirculation zone located below the baffle lateral edge. In contrast, under the double-baffle configuration, turbulence is primarily distributed around the through-hole of the baffle and extends both inside and outside of the baffle region.

Figure 8.

Steady-state turbulence intensity field cloud maps under different baffle conditions. (a) Single baffle at 36°; (b) Double baffles at 36°; (c) Single baffle at 30°; (d) Double baffles at 30°; (e) Single baffle at 24°; (f) Double baffles at 24°.

By comparing Figure 8b–f, it is observed that as the baffle angle decreases and the height of the baffle is reduced, the turbulence intensity increasingly accumulates in the fluid region at the bottom of the gearbox, outside the baffle. Meanwhile, the turbulence intensity in the vicinity of the gear teeth correspondingly decreases. These variations indicate that the spatial distribution of turbulence intensity is highly sensitive to changes in the baffle configuration. In the case of the single-baffle design, turbulence tends to concentrate within the recirculation zone. However, under the double-baffle configuration, the interaction between secondary flows and the main flow within the gap between the baffles gives rise to alternating vortex-shedding structures. These vortex structures enhance radial momentum transfer and facilitate a more uniform spatial redistribution of flow field energy. Therefore, the mitigation of turbulence intensity in proximity to the gear significantly decreases both oil stirring losses and energy consumption within the gear meshing zone.

Overall, the results suggest that by optimizing the baffle geometry and configuration, it is possible to improve the turbulence characteristics of the internal flow field. Such optimization contributes to enhanced lubrication efficiency and improved operational stability of the gearbox.

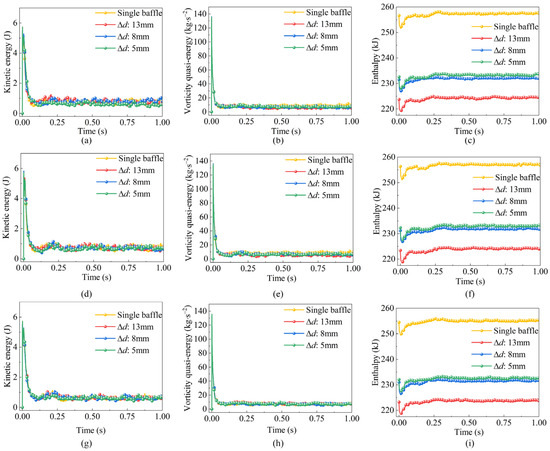

To further examine the regulatory mechanisms by which baffle configurations influence energy transport characteristics during the gear transmission process, the temporal variations in fluid enstrophy, kinetic energy, and enthalpy under different baffle conditions were extracted and are illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Curves of vorticity quasi-energy, kinetic energy and enthalpy of fluid with time under different baffle conditions. (a) Kinetic energy at 36°; (b) Vorticity quasi-energy at 36°; (c) Enthalpy at 36°; (d) Kinetic energy at 30°; (e) Vorticity quasi-energy at 30°; (f) Enthalpy at 30°; (g) Kinetic energy at 24°; (h) Vorticity quasi-energy at 24°; (i) Enthalpy at 24°.

As shown in the figure, both enstrophy and kinetic energy exhibit a similar three-stage evolution pattern throughout the gear transmission process. In the initial stage, there is a rapid and pronounced increase in both enstrophy and kinetic energy. This surge is primarily attributed to the occurrence of shear-induced flow separation at the baffle edges, which destabilizes the boundary layer. The onset of boundary layer instability subsequently promotes the rapid formation and breakdown of vortex structures, leading to a significant escalation in enstrophy and kinetic energy levels. During the intermediate stage, the energy transport process displays an oscillatory decay pattern. At this phase, the generation and dissipation of vortical structures approach a dynamic equilibrium. As a result, the kinetic energy of the fluid is progressively dissipated into the surrounding environment. This dissipation causes a gradual attenuation in the amplitude of energy fluctuations. The oscillatory nature of this stage reflects an ongoing internal redistribution of energy within the flow field and signifies the system’s gradual transition toward a more stable dynamical state.

In the final stage, the energy transport processes exhibit signs of stabilization. Fluctuations in enstrophy and kinetic energy are markedly reduced, indicating that the internal energy distribution within the flow field has reached a state of dynamic equilibrium. The stability observed in this terminal phase suggests that, during long-term operation, the gear transmission system is capable of sustaining efficient energy transport and redistribution. This ensures consistent and smooth operation of the gear mechanism under steady-state conditions.

In contrast to the evolution of enstrophy, the temporal progression of the enthalpy field exhibits a pronounced asynchrony. During the initial operating stage of the gear transmission system, the enthalpy field undergoes a sharp and abrupt decline. This phenomenon is primarily induced by an instantaneous pressure drop occurring in the gear meshing region.

The sudden decrease in local pressure initiates a cavitation effect within this zone. More specifically, the intense pressure fluctuations generated during the meshing of gear teeth cause the localized pressure to fall below the saturated vapor pressure of the lubricating fluid. As a result, cavitation is triggered, leading to the rapid formation of vapor cavities. This phase-change process, which occurs over a very short timescale, not only modifies the physical properties of the fluid but also induces a significant shift in the energy transport mechanism. Consequently, the abrupt transformation in the thermodynamic state of the fluid manifests as a steep drop in enthalpy, marking a loss of dynamic equilibrium within the internal flow field. As the system gradually adapts to the evolving flow conditions, the enthalpy field begins to exhibit a slow and steady increase. Simultaneously, the amplitude of enthalpy fluctuations diminishes, indicating a progressive reorganization of the internal energy distribution within the flow field. At this transitional stage, a turbulence-dominated mechanism for energy redistribution is activated. During this phase, two dominant processes govern the energy transport: vortex breakdown and the energy cascade. The vortex breakdown mechanism facilitates the decomposition of large-scale coherent vortices into smaller-scale structures. Meanwhile, the energy cascade process transfers energy from these large scales to progressively smaller scales, where it is ultimately dissipated into thermal energy through viscous effects. This multi-scale transformation results in a comprehensive redistribution of kinetic and thermal energy within the fluid domain, marking the onset of a dynamic recovery period. During this stage, the intensity of energy fluctuations continues to decrease, and the flow field gradually approaches a more stable configuration. Eventually, the system reaches a quasi-equilibrium state characterized by a sustained and relatively stable energy flux. This evolutionary trajectory of the enthalpy field not only reflects the intricate fluid dynamics within the gearbox but also offers valuable theoretical guidance for optimizing gearbox structure and minimizing energy losses during transmission.

As illustrated in the figure, the enthalpy values under the dual-baffle configuration are consistently lower than those observed in the single-baffle system. This difference primarily arises from the distinct energy transfer mechanisms and flow field regulation capabilities inherent to each configuration. Although the single-baffle system is capable of achieving sufficient lubrication, its structurally simplistic design results in concentrated high-momentum impacts within specific regions. Additionally, the absence of secondary flow regulation limits the available energy dissipation pathways. These constraints contribute to elevated local energy losses and ultimately lead to a higher overall enthalpy within the flow field. In contrast, the dual-baffle configuration effectively reconstructs the energy transfer pathways within the flow channel through the coordinated placement of the front and rear baffles. The front baffle serves as a geometric guide, redirecting the high-momentum shear flow away from vulnerable regions. This diversion minimizes energy dissipation associated with localized high-speed impacts. Simultaneously, the rear baffle enhances the spatial distribution of the flow by optimizing the gap geometry. This promotes better interaction between the low-temperature ambient fluid and key regions of the gearbox, thereby facilitating a more uniform internal fluid distribution and reducing overall energy loss. Together, this dual-baffle system operates as a coordinated regulatory mechanism that significantly improves the efficiency of energy transport within the flow field. It mitigates localized momentum concentrations and enhances energy dissipation pathways, ultimately resulting in systematically lower enthalpy values when compared to the single-baffle configuration.

Research indicates that the dual-baffle configuration, by reconstructing the flow field distribution and energy transfer pathways, is capable of significantly reducing system energy losses while enhancing lubrication efficiency. Furthermore, variations in the geometric parameters of the baffles exert a direct influence on the evolution of flow separation and the development of vortex structures, which in turn dynamically regulate the coupling mechanisms between mechanical energy conversion and fluid energy transport processes. The synergistic interactions revealed in this study between fluid dynamic responses and energy transformation provide essential theoretical guidance for the optimized design of gearbox lubrication systems. Additionally, they offer valuable insights into the efficient regulation of complex flow energy within enclosed transmission environments.

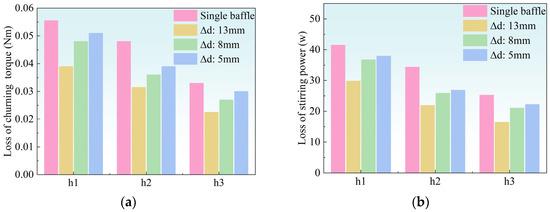

Figure 10 presents the oil stirring loss performance under various baffle conditions. Research shows that reducing the baffle height can effectively lower both stirring torque and power losses. This is primarily due to the optimization of the flow path and the mitigation of shear effects. Specifically, low-height baffles reconstruct the lubrication oil transport path by diverting laterally splashed oil toward the gear meshing zone. This diversion reduces the ineffective contact area on non-working gear surfaces, thereby decreasing torque loss dominated by shear forces. Additionally, a reduction in baffle height shortens the oil retention time, suppresses the sustained formation of local vortices, and significantly reduces the proportion of turbulent dissipation energy.

Figure 10.

Oil stirring losses under different baffle conditions. (a) Stirring torque losses; (b) Stirring power losses.

In contrast, the single-baffle system, due to its limited unidirectional guiding capability, cannot completely prevent the axial end-face backflow of oil. This limitation results in some energy being dissipated through secondary flows. Conversely, the dual-baffle configuration, by constraining the flow through bilateral channels, effectively inhibits disordered radial diffusion and concentrates the main shear flow in the meshing zone, thereby further reducing power loss. However, it is important to note that as the spacing between the baffles decreases, the radial migration path of the lubrication oil becomes obstructed. This obstruction leads to a pronounced increase in the intensity of axial backflow. Such reverse flow not only interferes with the main shear flow but also forms localized high-pressure zones in the gear interface gaps, further exacerbating energy losses. Moreover, although the contraction of the flow channels can accelerate flow velocity and improve the uniformity of oil coverage, the resulting sharp rise in wall shear stress causes the rate of frictional power loss to exceed the gains in lubrication efficiency.

Based on the above phenomena, it can be observed that optimizing lubrication in a dual-baffle configuration requires balancing spatial constraint intensity and flow resistance. When the baffle gap falls within a reasonable range, the front and rear baffles jointly optimize the oil transport pathway: the front baffle controls radial splashing through height adjustments, while the rear baffle maintains axial flow continuity by regulating the gap. This mechanism stabilizes both oil retention time and turbulence intensity in the working area, thereby preventing the uneven oil film coverage seen in single-baffle systems and avoiding flow blockage caused by excessively narrow dual-baffle gaps. By appropriately adjusting the combination of baffle parameters, an effective oil film thickness can be maintained while keeping oil stirring losses within a reasonable range, thus achieving global optimization of lubrication performance and energy efficiency. This optimization not only improves gearbox operational efficiency but also enhances system stability and reliability.

5. Conclusions

Studying the optimization mechanisms of baffle configurations in high-speed gear lubrication systems is critically important for improving the energy efficiency and reliability of lubrication performance under extreme operating conditions. In this study, a cross-scale multiphase coupled transport modeling approach is proposed to analyze gear-induced stirring lubrication. This method explores the nonlinear evolution of multiphase vortex-coupled transport phenomena in the flow field under varying baffle geometric parameters. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Based on the LBM-LES cross-scale coupled framework, a multiphase-coupled transport dynamics model was developed. This model characterizes the collaborative evolution of enstrophy, kinetic energy, and enthalpy. It reveals the nonlinear dynamic features within the flow field of the gearbox lubrication system. The rotation of the gears drives the fluid toward the top of the housing, forming a dynamic distribution. The fluid velocity in the gear meshing zone is significantly higher than in other regions. Its flow pattern is regulated by both the gear tooth profile and surface roughness, exhibiting complex nonlinear characteristics. In the top region, turbulence is markedly enhanced due to the combined effects of centrifugal force and wall constraints. In the bottom region, turbulence fluctuations are concentrated along both sides of the baffles. This leads to a flow field distribution with clear nonlinear dynamic features.

- (2)

- Changes in the cutoff-end angle of the baffle significantly affect the distribution of enstrophy in the flow field. A decrease in the angle enhances the confinement effect on the fluid, thereby suppressing the generation and development of enstrophy. The dual-baffle configuration optimizes the flow field structure by constraining the fluid pathways, effectively inhibiting disordered fluid motion. The distribution of turbulence intensity is closely related to the baffle configuration. The dual-baffle design, through alternate shedding of vortex structures, enhances radial momentum transport. This reduces both the turbulence intensity in the gear meshing zone and the associated oil stirring losses.

- (3)

- The dual-baffle configuration reduces localized high-momentum impacts and energy dissipation by optimizing the energy transfer pathways within the flow channel. This results in lower system enthalpy compared to the single-baffle system. Reducing baffle height effectively decreases stirring torque and power losses by optimizing the flow path and suppressing the formation of local vortices. However, a smaller gap between the baffles intensifies axial backflow and exacerbates energy losses. The study confirms that by optimizing the combination of baffle parameters, it is possible to maintain an effective oil film thickness while keeping stirring losses within an acceptable range. This approach achieves a global optimum in lubrication performance and energy efficiency.

The current model simplifies the system by neglecting bearing structures, which implies that the simulated flow interactions are valid under the condition of rigid gearbox housing. While this assumption allows focused analysis of baffle geometry effects, future studies will incorporate bearing dynamics to evaluate their coupling with oil transport mechanisms. Moreover, future research will consider using lubricants of different viscosities and further explore the effects of viscosity changes on the formation of oil films, turbulent structures, and energy losses, in order to verify the applicability of the model under different operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Y.T.: Writing-review & editing, Writing-original draft, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Q.L.: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation. D.T.: Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. L.L.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing-Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (RF-A2024001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| fi(x,t) | density distribution function of the i-th component |

| x | discrete spatial position |

| t | time |

| ξ | molecular velocity vector |

| F(x,t) | external force term |

| Ωi | collision operator |

| c | lattice speed |

| u | macroscopic velocity of the fluid |

| ρ | fluid density |

| p | pressure |

| cs | Lattice Speed of Sound |

| α | coordinate directions |

| wi | total particle distribution function |

| F(Ξ) | generating function obtained by mapping the density distribution function |

| Ξ | frequency space |

| Y | wavenumber variables in frequency space |

| kαβγ | cumulant |

| ωαβγ | relaxation rate |

| β | coordinate directions |

| γ | coordinate directions |

| cumulant in equilibrium state | |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| vsgs | subgrid-scale motion viscosity |

| Sαβ | strain rate tensors |

| Gαβ | strain rate tensors |

| Δ | filter width |

| τiαβ | subgrid stress closure tensor |

| v | total viscosity |

| τ | relaxation time |

Abbreviations

| LBM | lattice Boltzmann method |

| LES | large eddy simulation |

| MPS | moving particle semi-implicit |

| SGS | subgrid stress model |

| WALE | Wall-Adapting Local Eddy-viscosity |

| VOF | Volume of Fluid |

References

- Bao, H.; Huang, W.; Lu, F. Investigation of engagement characteristics of a multi-disc wet friction clutch. Tribol. Int. 2021, 159, 106940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, P.; Quan, C.; Wang, J. CFD investigation on oil injection lubrication of meshing spur gears via Lattice Boltzmann Method. Lubricants 2022, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Chen, G.; Luo, X.; Cheng, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, A. Bionic octopus-like flexible three-dimensional force sensor for meticulous handwriting recognition in human-computer interactions. Nano Energy 2024, 123, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiban, R.; Changenet, C.; Marchesse, Y.; Ville, F.; Belmonte, J. Churning losses of spiral bevel gears at high rotational speed. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2020, 234, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, F.-N.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, K.-Q.; Song, Y.; Lu, J.-T.; Xu, M.-J.; Qian, M.-Y.; Zhang, W.-A.; Wu, J.-X.; et al. Quantitative softness and texture bimodal haptic sensors for robotic clinical feature identification and intelligent picking. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp0348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrone, M.N.; Concli, F. Simulation of fluid’s aeration: Implementation of a numerical model in an open source environment. Adv. Fluid Dyn. 2021, 132, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell, M.; Sawicki, J. Pumping loss of shrouded meshed spur gears. ASME J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2020, 142, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M.; Song, C.; Yang, X.; Tang, H. Enhancing the Mechanical Behaviors of 18Ni300 Steel through Microstructural Evolution in Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 4215–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concli, F.; Mastrone, M.N. Latest advancements in the lubricant simulations of geared systems: A technology ready for industrial applications. Forsch. Ingenieurwesen 2023, 87, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hong, B.; Chen, H.; Qi, H.; Zhang, J.; Hang, W.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, K.; Lyu, B. Enhancing Tungsten Machinability via Laser Pretreatment for Abrasive Particles-based Shear Rheological Polishing. Powder Technol. 2025, 455, 120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, P.; Li, Q.H.; Yin, Z.C.; Zheng, R.Y.; Wu, J.F.; Bao, J.J.; Qi, H.; Tan, D.P. Multi-field coupling particle flow dynamic behaviors of the microreactor and ultrasonic control method. Powder Technol. 2025, 454, 120731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschuh, M.; Guner, A.; Kahraman, A. An experimental investigation of windage and oil churning power losses of gears and discs. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2023, 237, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changenet, C.; Vel, P. Housing influence on churning losses in geared transmissions. J. Mech. Des. 2008, 130, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisawa, H.; Nishimura, M.; Imai, H.; Goi, T. CFD simulation for reduction of oil churning loss and windage loss on aeroengine transmission gears. In ASME TurboExpo 2009: Power for Land, Sea, and Air; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Arisawa, H.; Nishimura, M.; Imai, H.; Goi, T. Computational fluid dynamics simulations and experiments for reduction of oil churning loss and windage loss in aeroengine transmission gears. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2014, 136, 092604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, L.; Dangl, F.; Sedlmair, M.; Thomas, L.; Karsten, S. CFD analysis on the oil flow of a gear stage with guide plate. Forsch. Ingenieurwesen 2022, 86, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jurkshat, T.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Detailed investigations on the oil flow in dip-lubricated gearboxes by the finite volume CFD method. Lubricants 2018, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jurkshat, T.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Determination of oil distribution and churning power loss of gearboxes by finite volume CFD method. Tribol. Int. 2017, 109, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atencio, B.N.; Yao, H.D.; Chernoray, V. Experiments and Lattice-Boltzmann simulation of flow in a vertically aligned gearbox. J. Tribol. 2023, 145, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concli, F.; Mastrone, M.N. Advanced lubrication simulations of an entire test rig: Optimization of the nozzle orientation to maximize the lubrication capability. Lubricants 2023, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, S.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X. Investigation of characteristics of splash lubrication and churning power loss in gearboxes with a guide plate. Tribol. Int. 2024, 198, 109875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Huang, H.; Yan, C.; Yuan, X.; Tang, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, S. An efficient aluminum gradient mesh wick for enhancing boiling heat transfer performance. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 152, 107320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikhansky, A. An engineering model of a turbulent liquid film flow. Eur. J. Mech. -B Fluids 2021, 90, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wu, W.; Hou, X.; Nelias, D.; Yuan, S. Research on flow pattern of low temperature lubrication flow field of rotating disk based on MPS method. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wu, W.; Gui, P.; Zou, T.; Zhang, J. Investigation of churning torque for hydraulic torque converter based on CFD. Tribol. Int. 2022, 174, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.Q.; Lin, Y.H.; Qi, H.; Li, Y.T.; Li, X.L.; Li, C.; Li, Z.A.; Xu, K.Q. The impact of ultrasonic-induced jet morphology on polishing efficiency. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 284, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Xu, P.; Wang, T.; Yan, Q. Study on the bubble collapse characteristics and heat transfer mechanism of the microchannel reactor. Processes 2025, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, L.; Chernoray, V.; Bohnert, C.; Concli, F. Particle Image velocimetry measurements inside a tapered roller bearing with an outer ring made of sapphire: Design and operation of an innovative test rig. Tribol. Int. 2022, 165, 107313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Xunmei, W.; Mengtao, H.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of solid wall boundary conditions in the lattice Boltzmann method on turbulent outdoor flow: A case study of a single 1:1:2 building model. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.F.; Ni, Y.S.; Xu, W.X.; Xie, Y.S.; Li, L.; Tan, D.P. Key technologies and development trends of the soft abrasive flow finishing method. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2023, 24, 1043–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, F.; Jacon, J.; Sagaut, P. A multidisciplinary model coupling Lattice-Boltzmann-based CFD and a social force model for the simulation of pollutant dispersion in evacuation situations. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, M.; Schönherr, M.; Pasquali, A.; Krafczyk, M. The cumulant lattice Boltzmann equation in three dimensions: Theory and validation. Comput. Math. Appl. 2015, 70, 507–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Eldho, T.I. A meshless weak strong form method for the groundwater flow simulation in an unconfined aquifer. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2022, 137, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Zhan, W.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Dai, W.; Gong, R.; Wang, F. Application of the least-square meshless method to gas-water flow simulation of complex-shape shale gas reservoirs. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2021, 129, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkariani, M.R.; Firoozjaee, A.R. An improved node moving technique for adaptive analysis using collocated discrete least squares meshless method. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2021, 130, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.J.; Li, L. Analysis of Flow Field and Machining Parameters in RUREMM for High-precision Micro-texture Fabrication on SS304 Surfaces. Processes 2025, 13, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafczyk, M.; Tölke, J.; Luo, L. Large-eddy simulations with a multiple-relaxation-time LBE model. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2003, 17, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Shi, B. Multiple-relaxation-time lattice Boltzmann method for the Navier-Stokes and nonlinear convection-diffusion equations: Modeling, analysis, and elements. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 023306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, P.; Li, Q.H.; Zheng, R.Y.; Xu, X.M.; Wu, J.F.; He, B.Y.; Bao, J.J.; Tan, D.P. A coupled LBM-LES-DEM particle flow modeling for microfluidic chip and ultrasonic-based particle aggregation control method. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 143, 116025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ma, M.; Qi, H.; Wang, X.; Xing, Z.; Alowasheeir, A.; Tang, H.; Jun, S.C.; Yamauchi, Y.; Liu, S. 3D-Printed photocatalysts for revolutionizing catalytic conversion of solar to chemical energy. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 151, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yu, J.; Lin, L.; Yuan, J.; Tan, D. Multi-physical coupling modeling and ultrasonic crack detection mechanism analysis for underwater steel structures. Ocean Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Wang, L. GPU-based unresolved LBM-DEM for fast simulation of gas–solid flows. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tang, R.; Wang, S.; Zou, Z. A coupled LES-LBM-IMB-DEM modeling for evaluating pressure drop of a heterogeneous alternating-layer packed bed. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniello, A.; Schuster, D.; Werner, P.; Boussuge, J.F.; Gatti, M.; Mirat, C.; Rude, U. Comparison of a finite volume and two Lattice Boltzmann solvers for swirled confined flows. Comput. Fluids 2022, 241, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Z. A numerical study on the sedimentation of adhesive particles in viscous fluids using LBM-LES-DEM. Powder Technol. 2021, 391, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, L. Mechanism of multiphase flow transport in laterally-compressed cathode channels with fin-type obstacles for PEMFC. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Shen, Q.; Ma, M.; Ji, R.; Guo, H.; Qi, H.; Xing, W.; Tang, H. 3D Printing of Porous Ceramics for Enhanced Thermal Insulation Properties. Adv. Sci. 2024, 12, 2412554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wen, R.; Ma, X.; Yang, R. Liquid film boiling enabled ultra-high conductance and high flux heat spreaders. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, Q.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, L.; Tan, D.P.; Wu, H.P. Interlayer healing mechanism of multipath deposition 3D printing models and interlayer strength regulation method. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 141, 1031–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Shao, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z. Research on splash lubrication characteristics of a spiral bevel gearbox based on the mps method. Lubricants 2023, 11, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Li, S. A fully-resolved LBM-LES-DEM numerical scheme for adhesive and cohesive particle-laden turbulent flows in three dimensions. Powder Technol. 2024, 440, 119800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Hang, W.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A novel in-situ sensor calibration method for building thermal systems based on virtual samples and autoencoder. Energy 2024, 297, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.S.; Jeong, Y.H. An investigation of pressure build-up effects due to check valve’s closing characteristics using dynamic mesh techniques of CFD. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 152, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Wu, J.F.; Xie, Y.S.; Yin, Z.C.; Tan, D.P. Deposition Mechanism of Microscopic Impacting Droplets on Flexible Porous Substrates. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 288, 110050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, L.; Rubio-Clemente, A.; Chica, E. Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Vortex Profiles in Gravitational Water Vortex Hydraulic Turbines. Energies 2024, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Shi, L.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Yang, P.; Xiao, H.; Chen, D.; Zhao, P.; Shen, X. A virtual sample diffusion generation method guided by LLM-generated knowledge for enhancing information completeness and zero-shot fault diagnosis in building thermal systems. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, J.T. Theoretical investigations on lattice Boltzmann method: An amended MBD and improved LBM. Acta Mech. Sin. 2021, 37, 1659–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, Q.H.; Xu, P.; Zheng, R.Y.; Bao, J.J.; Li, L.; Tan, D.P. Transport mechanism and optimization design of the LBM-LES coupling-based two-phase flow in static mixers. Processes 2025, 13, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.H.; Li, L.; Zheng, G.A. Study on the dynamic characteristics of the gear lubrication flow field with baffles and optimization design strategies. Lubricants 2025, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Peng, F.; Xu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Tokunaga, K.; Wu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; et al. Hydrogen retention and affecting factors in rolled tungsten: Thermal desorption spectra and molecular dynamics simulations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 30522–30531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Ai, D.; Wang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Li, Y. Multi-component LBM-LES model of the air and methane flow in tunnels and its validation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 553, 124279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Yao, H.-D.; Davidson, L. Synthetic turbulence generator for lattice Boltzmann method at the interface between RANS and LES. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 055118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.H.; Xu, P.; Li, L.; Xu, W.X.; Tan, D.P. Investigation on the Lubrication Heat Transfer Mechanism of the Multilevel Gearbox by the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Process 2024, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, L.; Pu, X.; Zheng, R.; Yin, Z.; Bao, J.; Yang, Y.; Tan, D. Multiscale heat transfer mechanism and dynamic regulation of free-surface swirling flow based on LBM-LES coupling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Devahdhanush, V.S.; Mudawer, I. Investigation of subcooled and saturated boiling heat transfer mechanisms, instabilities, and transient flow regime maps for large length-to-diameter ratio micro-channel heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 123, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, P.; Luo, L.S.; Krafczyk, M. The lattice Boltzmann method for nearly incompressible flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2021, 431, 109713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Bian, J.; Dai, Y. A quasi-analytical prediction method for gear load independent power losses for shroud approaching. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 48, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Boivin, P.; Thévenin, D.; Karlin, I. Lattice Boltzmann methods for combustion applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 102, 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Linton, D.; Thornber, B. Rotorcraft fuselage and ship airwakes simulations using an immersed boundary method. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2022, 93, 108916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. Simulation of High-Viscosity Generalized Newtonian Fluid Flows in the Mixing Section of a Screw Extruder Using the Lattice Boltzmann Model. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47991–48018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).