Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify and explore the most significant barriers in implementing smart manufacturing (SM) in terms of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). A two-round Delphi method was used to uncover them in this regard. To assess the reliability of the obtained results, Cronbach’s alpha, Intraclass correlation coefficient, and a statistical F-test were performed for both rounds. Cronbach’s alpha for round 1 was 0.729, and 0.816 for round 2. On this basis, good inter-rater reliability was demonstrated in round 2. At the same time, the Intraclass correlation coefficient from round 1 was 0.54, and from round 2, it was 0.74, indicating a significant improvement in panel consensus. The comparison of the equality of variances within the two rounds using the F-test confirmed that a third round of the survey was not necessary. Moreover, the coefficient of variation and relative interquartile range were applied to assess internal consistency among the involved experts to come to a more comprehensive and cohesive understanding of the issue at hand. A total of 30 barriers/limitations or shortages were identified in the preparatory phase of the research, which, in some sense, do not allow or slow down the implementation of the SM. The Delphi survey found that financial problems, lack of government support, and technological constraints can be considered as the most serious barriers to the implementation of SM in an SME environment. Finally, the obstacles/constraints or shortcomings that proved to be the most critical were analyzed in terms of their impact on the ability of small and medium-sized enterprises to embrace the challenges of smart manufacturing.

1. Introduction

One of the crucial features of the fourth industrial revolution is undoubtedly the smart manufacturing (SM) concept that involves disruptive technologies such as machine learning techniques, cyber-physical systems, cloud computing, Internet of Things, additive manufacturing devices, collaborative robotics, digital twin solutions, high-performance computing, and others. Moreover, it encompasses computer-integrated manufacturing philosophy, facilitating the ability to readily adjust to new manufacturing conditions, digital information technology, and other intelligent tools and devices [1,2,3]. The reasons for the emergence of this concept were related, among other factors, to the requirement to respond to rapid changes in production due to the growth of individual consumer needs. SM can be defined as a fully-integrated, collaborative manufacturing system that responds in real time to meet changing demands and conditions in the factory, in the supply network, and in customer needs [4]. The positive fact is that SM as a management strategy is becoming more common, especially in terms of large enterprises. This is manifested, e.g., by increasing machine-to-machine connections based on mobile technologies, which is measurable by the global market size in this industrial segment. According to Okkonen et al. [5], the machine-to-machine market is expected to be the largest submarket within the IoT, and its volume in 2032 is expected to be almost 58 billion USD [6]. In other words, millions of devices and machines are connected through IoT and communicate with each other [7]. It is understandable that this trend also has a positive impact on the share of small and medium-sized enterprises in the overall successful implementation of SM. Although these figures hypothetically make SM increasingly feasible, a measurable return on investment appears to be the most crucial motivating factor for implementing this manufacturing strategy from the perspective of SMEs [8]. Moreover, there are other differences between SMEs and large enterprises that determine the level of effort to implement these disruptive technologies and tools. For example, most small and medium-sized enterprises typically pursue a short-term strategy, which prevents them from focusing on long-term investments [9]. In addition, some of the above-mentioned smart tools and technologies are difficult to introduce in SMEs due to a lack of specific knowledge within a technical domain and leadership [10]. It is also important to keep in mind that the implementation of modern information systems, such as ERP, MES, CRM, or MRP in SMEs, unlike large companies, is time-consuming, financially demanding, and associated with the risk of not meeting expectations [11,12,13]. When considering the fact that SMEs represent the backbone of the economy in most countries and industries [14,15,16,17], then finding ways to overcome these disadvantages is one of the most important challenges for practitioners and researchers. In this context, the primary objective of this paper is to identify the potentially most serious obstacles to the implementation of SM in small and medium-sized enterprises. Subsequently, these obstacles are grouped into unifying areas and categorized in terms of their importance. The paper is structured as follows. After a detailed presentation of the methodological framework, the next part is devoted to identifying potential barriers to implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Bibliographic analysis tools were applied for this purpose. Subsequently, the Delphi survey is described and analyzed in detail. Finally, relevant findings and conclusions are presented.

2. Methodological Framework

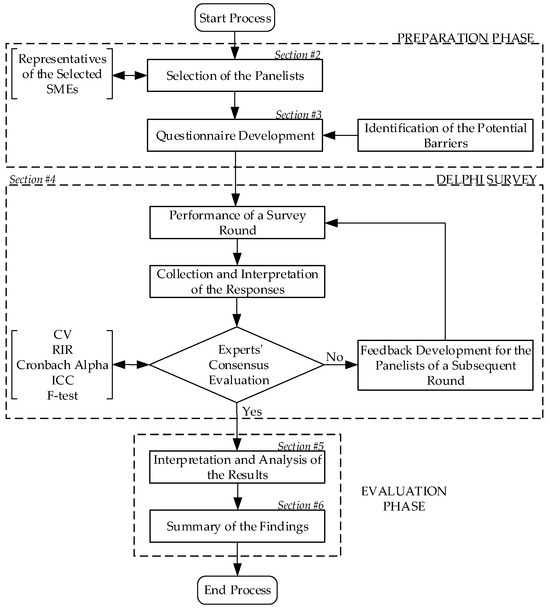

This study primarily uses the Delphi technique, a widely used method for achieving consensus among a group of experts on a specific topic. The Delphi method was developed in the 1950s by the Rand Corporation and was originally used as a forecasting technique in the military sector [18]. This method is based on the logical assumption that two or more heads are better than one [19] and that input obtained from experts is much better than intuitive estimates. It involves controlled communication between individuals in a selected sample of experts and the creation of a forum where participants can anonymously express their opinions and receive feedback from other members of the sample. In addition, it includes the possibility for individuals in the sample to revise their opinions based on the opinion of the group [20]. In other words, this method exploits the effects of collective intelligence by synthesizing human knowledge and expertise in order to objectify an opinion on a particular issue that each individual could not form on their own. The second and central methodological pillar of this method is statistical probability. The related statistical tools will be presented and applied in Section 4. It is also useful to note that, in the decades since its inception, several different modifications of the Delphi method have emerged to address specific situations and objectives [21]. However, its basis remains unchanged, given its fixed principles, which are an iterative and multi-stage process, controlled feedback, the possibility for panel members to revise their answers, and anonymity [22]. These principles are fully reflected in the presented study, in which the Delphi method was implemented according to the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Delphi technique flow chart.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the first important step in this procedure is the selection of panelists who will represent the sample of the target population being studied. It is worth noting that some authors (see, for example, [23]) consider the selection of respondents to be the most important step in the Delphi technique. Since this research was part of an international project with participants from Italy, Austria, Malta, Sweden, Germany, Slovakia, the United States, Argentina, South Africa, Thailand, and Australia (see more at https://sme50.eu/ (accessed on 20 September 2025)), the size and selection of this sample were subject to internal methodology approved by the members of the project consortium. Based on the guidelines of the project consortium, in accordance with commonly used rules for similar surveys [24], it was recommended that at least ten participants be involved in the survey. In line with this, twelve experts with relevant professional experience and willingness to participate in accordance with the relevant data protection rules were selected from various small and medium-sized enterprises. Potential respondents from large enterprises or those who did not meet the above criteria or had a conflict of interest were excluded. It should also be added that the survey involved small and medium-sized enterprises from Slovakia operating in the manufacturing sector or in sectors focused on manufacturing-related services, including owners, managers, and consultants. Since the research used the classic Delphi technique [21], the selection of respondents was carried out in such a way that the sample formed a homogeneous group of respondents who had similar expertise on the issue under investigation.

An equally important step in the diagram was the development of the questionnaire. Since it consists of several tasks, its procedure is described in more detail in the following section.

3. Identification of Potential Barriers for SM Implementation

The aim of this section is to review the relevant literature in order to identify potential barriers to SM implementation and categorize them into areas according to their common features. For this purpose, the Web of Science Core Collection database was used to select the literature with the greatest impact on the topic based on the highest number of citations. The search terms used to map the most important studies were as follows: barriers (topic) AND small and medium-sized enterprises (topic) AND industry (topic), entered on 18 June 2025. In this way, 15 articles were selected, from which the individual barriers that interested us were extracted. The list of articles, ranked from most to least significant, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Top cited articles with individual barriers of interest.

Subsequently, all 30 identified barriers/limitations/shortages were classified into six areas shown in Table 2. While five of them are assigned to the common domains, one is reserved for barriers that were not specifically classified.

Table 2.

Potential barriers divided into unifying areas.

The final step in this phase was to formulate the content of the questionnaire for the subsequent survey using the Delphi method. Since some of the identified barriers were similar in nature, they were merged to reduce their number appropriately. Some of them, such as “22. Lack of consumer interest,” were considered less significant in terms of the research objectives and were therefore not included in the final selection of identified barriers. In addition to the barriers identified in this way, respondents had the opportunity to add to the list of barriers at their own discretion. In this way, the item “No. 20 Lack of initiatives to create business clusters” was added to the list of the most important obstacles. Its final form is shown in Table 3, which aims to provide information on the potentially most influential obstacles in each of these areas. Of these barriers, 12 are internal in nature (factors 1–4, 8–14, 16), and the remaining 8 factors (5–7, 15, 17–20) are external in nature.

Table 3.

Final form of the questionnaire for the purposes of the Delphi method.

The rationale for selecting these areas can be verified or justified by relevant studies on this issue, which are discussed in the following text.

Agolla [41] emphasized the importance of human resources in this regard, as today’s workers in small and medium-sized enterprises must come to terms with the fact that their current roles may not be relevant in the future. As a result, small and medium-sized enterprises face a shortage of digital technology experts [42] and a lack of adequate training programs [43,44]. Furthermore, at the management level, it is not uncommon for competent actors to hesitate to adopt new technologies due to a lack of strategic vision and fear of failure [45,46,47,48].

As is well known, the absence of usable methodological tools for implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises similarly contributes to low interest in taking up this challenge. Other potential obstacles to these efforts include limited managerial knowledge, which can manifest itself in a lack of understanding of the Industry 4.0 concept. This often leads to small and medium-sized enterprises not having a clearly defined plan for implementing this concept [49,50,51,52].

SM, which offers a number of advantages, is more expensive than traditional manufacturing. It requires high initial investment and ongoing financial management during the digital transformation, which can cause significant difficulties for small and medium-sized enterprises, e.g., in obtaining the necessary funds. In addition, the introduction of SM in small and medium-sized enterprises requires operating costs such as software updates, system maintenance, and employee training [53,54,55]. Small and medium-sized enterprises often lack confidence in the financial benefits of implementing Industry 4.0 due to uncertain returns on investment and long payback periods [56,57,58]. This area is closely linked to the technological barriers to implementing effective SM, as limited financial resources prevent small and medium-sized enterprises from investing in digital technologies. Small and medium-sized enterprises often work with outdated technological equipment and lack the digital infrastructure necessary to implement Industry 4.0. Interoperability and integration issues with current systems further complicate the transition of small and medium-sized enterprises towards SM due to incompatibility with specific technological standards [59,60,61,62].

Another relevant area of barriers to SM implementation is information management and cybersecurity, which are an integral part of the SM concept. In relation to data management challenges, small and medium-sized enterprises often struggle with secure data management, including data collection and processing, due to a lack of understanding of advanced data analysis tools [63,64].

Of course, other areas of obstacles can also be identified, but the aim of this research is to capture the most important ones. For this reason, selected uncategorized barriers to SM implementation are labeled as other aspects. Such barriers, in our view, include insufficient support from the government and little or no support from universities. It is understandable that small and medium-sized enterprises are affected by government regulations, compliance requirements, and a lack of supportive policies, which can limit their ability to adopt innovative practices and technologies [65,66]. Compliance with regulatory requirements, therefore, represents a significant barrier to the implementation of SM [67,68]. In terms of support from universities, as stakeholders in the development of the industry, they are expected to cooperate in the implementation of Industry 4.0 and similar concepts. Universities in the context of Industry 4.0 should first of all change their curricula to ensure that their graduates are properly qualified and helpful in implementing this strategy [69,70]. Consequently, their assistance should be focused on direct cooperation with industry in the form of the transfer of research knowledge into practice. However, this perception may not always correspond to reality, in which case it becomes a hindrance, although this, in turn, should contribute to the successful implementation of SM in practice.

4. Description of the Delphi Survey

4.1. Performance of the Survey Rounds

Because Delphi is an iterative method, the exploration takes place in at least two rounds. In the first round, respondents anonymously completed a closed-ended questionnaire used for this purpose with pre-defined response options (see Table 3). In our case, the assessors were instructed to rate relevance in percentages on a scale of 0, 10, …, 100%. The first round of responses is shown in the left part of Table 4.

Table 4.

Obtained results through two rounds of the Delphi method in percentages.

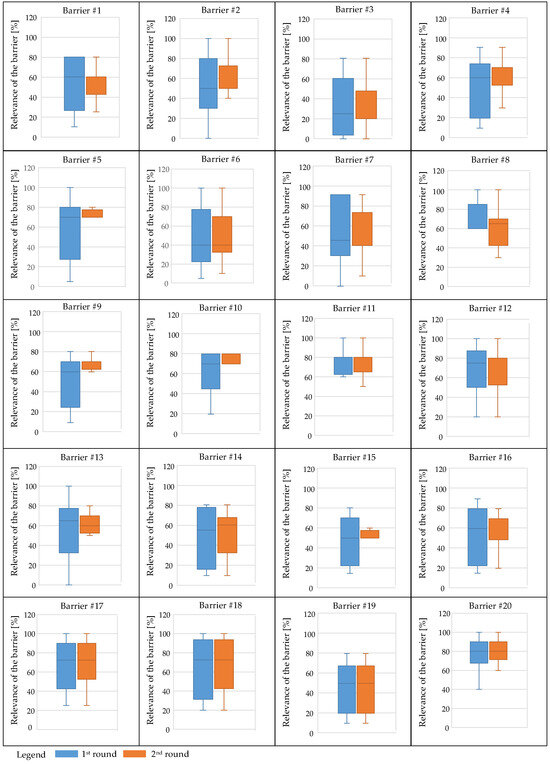

The primary objective of the survey in this round was to identify an initial view of the most influential barriers within each area. In particular, an analysis of the internal consistency of the results was carried out after the data from the first round had been collated. For the purposes of this analysis, the Coefficient of variation (CV) and Relative interquartile range (RIR) were used to assess the degree of consensus between experts’ ratings. The enumerated values, which are described in detail in Section 4.2.1, indicate that the next round is recommended. In addition, to assess the reliability of the responses between different rounds, Cronbach’s alpha has been calculated. Its value α = 0.729 indicated acceptable reliability of the first-round results (see more in Section 4.2.1). Subsequently, the results of the first round were summarized in the form of box plots for the purpose of the second round, which are shown in blue in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Boxplot diagrams comparing both rounds.

These diagrams were made available to respondents to provide feedback for the second round of the survey. Based on the responses from the first round processed in this way, the panelists had the opportunity to correct their answers in the second round. The results of the second round, which are shown in the right part of Table 4, were subsequently processed in an analogous manner. First, box plots were generated, which are shown in orange in Figure 2. The advantage of interpreting the results in the form of box plots is that their paired presentation allows a visual assessment of the degree of convergence of respondents’ opinions. Visual analysis of the box plots indicates that the Delphi method effectively improved consensus in the second round. More items showed a reduction in response variability, which is observable from the narrowing of the interquartile ranges. However, visual assessment is not sufficient to decide on the (un)necessity of a further round. For this reason, a statistical F-test was used (see its application in Section 4.2.2), which showed that the dispersion of responses had decreased sufficiently from one round to the next, indicating an acceptable level of consensus.

Moreover, after this second round, the Cronbach’s alpha value has been calculated and compared to the value from the first round. This second test equally confirmed the unnecessary nature of the third round. A comparison of the results of both rounds of the Delphi method is described in the following subsection.

4.2. Assessment of Responses’ Reliability

4.2.1. Evaluation of Internal Consistency After the First Round

Consensus evaluation of the first round was made through the three indicators, the coefficient of variation (CV), the Relative interquartile range (RIR), Cronbach’s alpha, and the Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

The coefficient of variation is a method used to measure the dispersion of opinions. It is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation (SD) to the mean () and is used in the Delphi method to measure consensus because it allows direct comparison of subsequent rounds. Increasing consensus occurs when the coefficient of variation decreases from one round to the next [71,72]. The levels of consensus are as follows [73]:

- 0 ≤ CV ≤ 0.5—good degree of consensus, no additional round necessary,

- 0.5 < CV ≤ 0.8—less than satisfactory consensus, possible need for another round,

- 0.8 ≤ CV—poor degree of consensus, need for additional round.

The CV values along with SDs and means for individual barriers are presented in Table 5 (left).

Table 5.

Calculated values of the statistical measures used after the 1st round.

When analyzing the CV values, it can be seen that a good degree of consensus was achieved in 50% of the items, while the remaining 50% of the items showed higher variability. Therefore, a subsequent round is suggested.

To assess the degree of consensus between the experts’ evaluations, the relative interquartile range was then calculated according to the formula [71]:

where Q1 is first quartile range; Q2 is median; and Q3 is third quartile range. The thresholds for RIR values interpretation in this study were compiled from different sources [74,75,76] to cover a wider range as follows:

- If 0 ≤ RIR ≤ 0.25, it means a very strong consensus, no additional round necessary,

- If 0.25 < RIR ≤ 0.50, it indicates less consensus—possible need for another round,

- 0.50 ≤ RIR, then there is a need for an additional round, due to a low consensus.

The corresponding RIR values for all individual barriers are presented in Table 5 (right). In the assessment of the RIR values, a very strong consensus (no need for an additional round) was achieved in three barriers (see items #8, #11 and #20 in Table 5), while a lower level of consensus indicating a possible need for another round was observed in two berries (see items #10 and #12 in the same table), while the remaining 75% indicated that an additional round is needed.

Cronbach’s alpha (α) as a complementary statistical measure was used to assess the internal consistency (reliability) of a set of related items in the questionnaire. In other words, ‘α’ evaluates how well the items in a scale measure the same construct, essentially showing how well the items correlate with each other. This measure is scored between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates perfect internal consistency and 0 indicates no internal consistency (items are completely unrelated). It is commonly used in survey research to ensure measurement consistency. Its expression is as follows [77]:

where k is the number of items; si is SD of i-th item; st is the sum of set of individual scores. Interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha (α) values is as done in [78]:

| α ≥ 0.9 | Excellent |

| 0.8 ≤ α < 0.9 | Good |

| 0.7 ≤ α < 0.8 | Acceptable |

| 0.6 ≤ α < 0.7 | Questionable |

| 0.5 ≤ α < 0.6 | Poor |

| α < 0.5 | Unacceptable |

The acceptable reliability of the first round was confirmed, since its value after the first round equals 0.729.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was originally introduced by Fisher in 1954 as a modification of the Pearson correlation coefficient. In today’s applications, the index ICC is derived from mean squares (estimates of population variances) based on the variability among a given set of measurements, which is obtained through analysis of variance (ANOVA). ICC is used for the enumeration of experts’ judgements, as this indicator is recommended as a measure of inter-rater agreement; it evaluates the consistency of ratings across experts. In this study, a two-way random-effects model is applied, for single measures indicator ICC (2,1), which identifies the reliability of a single expert’s rating, and for average measures indicator ICC (2,k), which measures the reliability of the average rating of the panel of k experts. Expressions of these indicators are as follows [79]:

where MSR—mean square for rows; MSE—mean square for error; k—number of raters (experts); n—number of subjects (barriers); MSC—mean square for columns.

Then, the obtained values can be interpreted as follows [79]:

| ICC ≥ 0.9 | Excellent reliability |

| 0.75 ≤ ICC < 0.9 | Good reliability |

| 0.5 ≤ ICC < 0.75 | Moderate reliability |

| ICC < 0.5 | Poor reliability |

First indicator ICC(2,1) reflects the reliability of a single expert randomly selected, and it indicates the degree of agreement between individual raters. In this case, the calculated value is low (ICC(2,1) = 0.09), but it is not unexpected in Delphi studies, as individual experts often bring heterogeneous perspectives and experiences.

Subsequently, the indicator ICC(2,k) is applied, which evaluates the reliability of the mean rating of all 12 experts (ICC(2,k) = 0.54), which means moderate reliability. As the Delphi method emphasizes group consensus rather than individual opinions, this indicator provides a more accurate reflection of the reliability of the panel’s collective judgment.

Based on CV and RIR values, it was necessary to perform a second round of the questionnaire.

4.2.2. Evaluation of Respondents’ Consensus After the Second Round

After the first round, CV, RIR, Cronbach’s alpha, and ICC values were calculated after the second round. The values are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Calculated values of the statistical measures used after the 2nd round.

Based on these values, it can be stated that:

- -

- When analyzing the CV values of the 2nd round, a total of 75% of the items (15 of 20) achieved a good degree of consensus. The remaining items fell within the moderate range, suggesting a lower, but still acceptable level of agreement. Importantly, no item exceeded the threshold of CV > 0.8.

- -

- As regards the RIR values, 55% of the items (11 of 20) showed very strong consensus. Another 35% (7 items) were in the intermediate range, and only 4 items (20%) exceeded the threshold of 0.5.

- -

- In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha value was quantified as 0.816, indicating a good level of internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire in this round. One can see that the level of respondents’ agreement in the second round increased by one level (from acceptable to good) compared to the first round.

- -

- When evaluating ICC values of the second round, ICC (2,1) equals 0.19 (poor agreement between individual experts), and in contrast, ICC (2,k) is 0.74, providing that the reliability of the panel’s mean rating is moderate, close to good. Based on that, it is demonstrated that the second round of the Delphi method effectively increased consensus within the expert panel.

In summary, the level of agreement among panelists significantly improved in the 1st round.

As mentioned in Section 4.1, the F-test to verify the improvement in consensus between rounds was also applied. The F-test is a statistical tool used to compare variances, means, or the overall fit of regression models [80,81,82]. It is based on the F-distribution and is commonly applied in ANOVA (Analysis of Variance), regression analysis, and variance equality tests. The F-test evaluates a null hypothesis (H0) against an alternative hypothesis (H1). The F-test for equality of two variances compares the variances of two populations. Under the null hypothesis, it is assumed that the variances (or standard deviations) are equal—H0: , while the alternative hypothesis considers the situation that the variances (or standard deviations) of the two populations are not equal—H1: . In order to compare the standard deviations, we calculate the F-statistic as the ratio of the variances of the two groups [83]:

where is variance of the first group; is the variance of the second group; df1 is numerator and it equals n1 − 1 (n1 is the number of items of the first group); df2 is denominator and it equals n2 − 1 (n2 is the number of items of the second group).

When the F-statistic value is identified, then the critical value is determined from the F-distribution table at a chosen significance level (α). A significance level (α) = 0.05 was used for this testing. The F-statistic can then be compared to this critical value. If the F-statistic value > critical value, H0 is rejected as the variances are significantly different. If the F-statistic value ≤ critical value, fail to reject H0 as there is no significant difference between the variances. Subsequently, the F-statistic test values were enumerated by comparing the ratio of the variances between the two rounds (see summary results in Table 7).

Table 7.

The values of standard deviations and F-statistics.

The results showed that the variance ratio between the first round and the second round was not large enough to be considered statistically significant, as the values fell within the confidence interval. This range indicates that the variability in responses did not change significantly between the rounds. Given that the F-test did not indicate any significant difference in variance, it was concluded that a 3rd round of the Delphi process was not necessary. The panelists’ responses showed a sufficient level of consensus, and the variability between the two rounds was within an acceptable range.

The above-mentioned findings suggest that the 2nd round was sufficient to refine the barriers and reach a stable set of conclusions for further analysis.

5. Discussion and Analyses of the Results

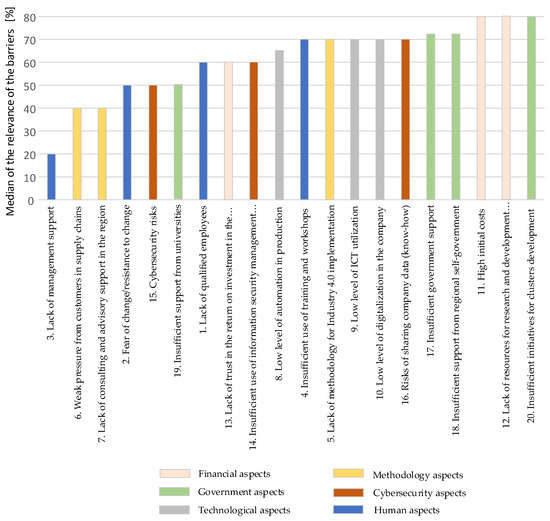

Based on the results of the second round of the survey, they can be analyzed from several perspectives. First, we can rank the individual barriers according to their perceived importance. It is also useful to examine these barriers in terms of the groups into which they were classified. For these two purposes, a bar chart was constructed as shown in Figure 3, in which the individual barriers are grouped into six groups and also in terms of their importance.

Figure 3.

Ranking barriers according to their significance and categorizing them into groups.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that the top five barriers fall into two categories: governmental factors and financial factors. Accordingly, these five groups of barriers perceived as the most significant by the respondents should be considered as the most critical challenges. In contrast, human resources factors were identified as the least significant compared to the other four.

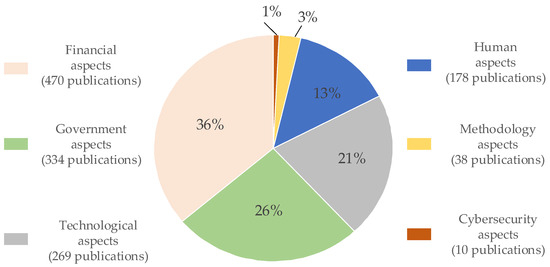

The significance and relevance of the selected aspects were further examined based on existing literature to determine whether the survey results are supported by prior research. For this purpose, the Web of Science Core Collection database was used to identify studies addressing barriers within each of the six defined categories, based on the number of publications. The search was conducted on 18 June 2025 using the following terms: barriers (Topic) AND SMEs (Topic) AND financial/government/technological/methodology/cybersecurity/human (Topic). The relevance of each aspect is summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Relevance of the investigated barriers from the perspective of SM implementation according to the number of publications.

A comparison of Figure 3 and Figure 4 confirms the relevance of the first three categories—financial, government, and technological aspects as they are supported by both the existing literature and the survey results.

Given the objective fact of knowing the most critical barriers—both from the views of the representatives themselves (Figure 3) and from the researchers’ perspective (Figure 4), it is then useful to address the question: What are the practical implications of this for SMEs? It is widely known that small and medium-sized enterprises are significantly limited in terms of financial and human resources [84,85,86], which is confirmed by earlier observations of a lack of resources in small businesses. However, small and medium-sized enterprises compensate for their disadvantage in human resources (HR) by using agile approaches and introducing a culture of developing innovative and flexible HR practices [87,88]. This may explain the finding of this study that human resources are not one of the most critical areas in this context. This differs from the conclusions of earlier studies (e.g., [89,90]), which emphasized HR as a central challenge in the transition to Industry 4.0. A completely different problem for SMEs compared to the lack of HR is financial constraints. Previous research showed that only SMEs that have sufficient financial resources consider the implementation of intelligent digital technologies as an economically realistic project [91], which is in line with the presented findings in this study. As regards technological barriers, it is indisputable that they are directly linked to financial constraints. For example, the introduction of ERP and MES, which are both crucial software systems for large companies, is approached differently in SMEs than in large enterprises [92]. This shows that SMEs often have a lower level of digitalization than their large counterparts. In addition, a large number of SMEs produce in small batches. Therefore, such enterprises had no or only weak motivation to invest in modern technologies, including digital ones. This aspect of disadvantage can be at least partially overcome by support from government institutions in the form of training, workshops, grants, etc. The results of this study show that this support is still insufficient, as can be seen from Figure 3 and Figure 4. The most serious barrier is considered to be the current situation in the area of creating business clusters for SMEs operating in the same product or technology segment, sustainability [93,94]. They often lack support from government and non-governmental institutions, and those that have already been established struggle with financial sustainability [95,96]. This forces organizations to prioritize short-term survival activities over strategic objectives. In addition, there is a lack of practical experience and specialized training in cluster management, which makes it difficult to assemble qualified teams to support joint research projects and to put existing innovative solutions into practice [97].

Building on these practical implications, to understand how and when these barriers affect SM implementation, it is important to identify the typical implementation stages. In general, SM implementation includes several phases such as (i) planning and preparation, (ii) technology adoption and human-technology integration, (iii) workforce training, and (iv) operation and evaluation phase. An assignment of the identified barriers within the mentioned stages provides better insight into their impact throughout the implementation process. In the planning and preparation phase, high initial costs, lack of trust in the return on investment, lack of clear implementation methodologies, insufficient government and regional support, and weak pressure from customers play a significant role. Moreover, lack of management support and limited resources for research and development impact this early stage. The technology adoption and integration phase includes barriers as low levels of automation, ICT utilization, and digitalization, and a lack of consulting support, which limit company progress. The workforce training phase is affected by a lack of qualified employees, resistance to change, insufficient training, and a lack of management commitment. During the last phase—the operation and evaluation stage, there are challenges as cybersecurity risks, insufficient use of information security systems, and risks related to data sharing become more significant.

Naturally, like any questionnaire study, this one also has certain limitations, mainly related to its regional nature. This fact could therefore theoretically limit the direct transferability of the presented findings to other regions where the business environment would differ in fundamental parameters. However, the authors of the study are convinced that the transferability of its results applies at least to the countries associated with the OECD, of which Slovakia joined in 2000. In addition, as is well known, the accuracy of questionnaire survey results generally increases with the consistency of respondents’ opinions. Therefore, its further iterations could provide even more objective findings.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

The study has the ambition to contribute to the identification and analysis of the critical barriers in the implementation of SM and thus contribute to a comprehensive investigation of this real problem. In this effort, the authors identified five key barriers, i.e., Lack of initiatives for establishing business clusters, Lack of resources for research and development activities, high initial costs, Insufficient support from regional self-government, and Insufficient government support. Of course, the ordering itself does not diminish the significance of the other barriers considered, but serves as a starting point for examining differences in their importance from the perspective of SMEs. In fact, mitigating the impact of these five barriers is primarily influenced by government decisions, regional government initiatives, and business support institutions such as chambers of commerce, business and information centers, business parks, and others. This goal, of course, cannot be achieved without pressure from SMEs on these institutions, which is preceded by an understanding of the importance of their support.

Understandable things are neither black nor white, and this is also true for the issue of SM implementation in SMEs. From a positive perspective on this issue, it is equally important to mention the following. Based on recent experience, it is possible to observe a trend that, despite the disadvantages of SMEs in the form of identified barriers, manufacturers in this size category are increasingly embracing digitalization in order to be able to respond more flexibly to the dynamics of the changing market and to be more competitive. To this end, they are increasingly shaking off their reluctance to invest in modern technologies in line with the Industry 4.0 concept [98]. In conclusion, the question for potential future research is what should be the pace of SM implementation for an SME category manufacturer to thrive, or at least survive, in the Industry 4.0 era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.; methodology, V.M.; formal analysis, V.M.; investigation, V.M. and Z.S.; data curation, Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M. and Z.S.; writing—review and editing, V.M. and Z.S.; visualization, Z.S.; supervision, V.M.; project administration, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the project SME 5.0 with funding received from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 101086487 and the KEGA project No. 044TUKE-4/2023 granted by the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The respondents provided their opinions and experiences voluntarily and anonymously for the purposes of this research in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision-making process.

References

- Davis, J.; Edgar, T.; Porter, J.; Bernaden, J.; Sarli, M. Smart manufacturing, manufacturing intelligence and demand-dynamic performance. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 47, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tao, F.; Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Freiheit, T. Smart manufacturing and intelligent manufacturing: A comparative review. Engineering 2021, 7, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrak, V.; Sudhakarapandian, R.; Balamurugan, A.; Soltysova, Z. A review on reinforcement learning in production scheduling: An inferential perspective. Algorithms 2024, 17, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, A. Smart manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkonen, H.; Mazhelis, O.; Ahokangas, P.; Pussinen, P.; Rajahonka, M.; Siuruainen, R.; Leminen, S.; Shveykovskiy, A.; Myllykoski, J.; Warma, H. Internet-of-Things Market, Value Networks, and Business Models: State of the Art Report. Computer Science and Information Systems Reports. TR-39. Technical Reports. 2013. Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstreams/37eb8c0b-7d2d-4d8b-aa46-88d38f66f79e/download (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Dai, G.; Huang, R.; Yuan, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, L.; Lu, J.; Ji, F. Towards Flawless Designs: Recent Progresses in Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Technology. Electronics 2023, 12, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammons, J.; Cross, M. The Basics of Cyber Safety: Computer and Mobile Device Safety Made Easy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Munasser, H. Understanding the Adoption Challenges of IoT Among Small to Medium-Size Enterprises (SMEs): Study in Sweden, Dissertation, 2024. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1918587/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Mintzberg, H. Structure et Dynamique des Organisations; d’Organisation, V., Ed.; Eyrolles: Paris, France, 1982; p. 434. ISBN 978-2708119710. [Google Scholar]

- Moeuf, A.; Tamayo, S.; Lamouri, S.; Pellerin, R.; Lelievre, A. Strengths and Weaknesses of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises Regarding the Implementation of Lean Manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, C.; Sutton, S.G.; Arnold, V. Technology Monoculture: ERP Systems, ‘Techno-Process Diversity’ and the Threat to the Information Technology Ecosystem. In Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research; Arnold, V., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.W.; Um, J.; Yoon, S.C.; Suk-Hwan, S. An architecture design for smart manufacturing execution system. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 2017, 14, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrak, V.; Mandulak, J. Mapping Development of MES Functionalities. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO 2009), Milan, Italy, 2–5 July 2009; pp. 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- Khairudin, S.M.H.H.S.; Amin, M. Towards Economic Growth—The Impact of Information Technology on Performance of SMEs. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2019, 9, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, K.; Belitski, M.; Ghobadian, A.; O’Regan, N. E-Leadership Through Strategic Alignment: An Empirical Study of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Digital Age. J. Inf. Technol. 2016, 31, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robu, M. The dynamic and importance of SMEs in economy. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2013, 13, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Soltysova, Z.; Modrak, V. Challenges of the sharing economy for SMEs: A literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N. Studies in the Quality of Life; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Stone Fish, L.; Busby, D.M. The delphi technique. In Research Methods in Family Therapy, 2nd ed.; Sprenkle, D.H., Piercy, F.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossler, T.; Falagara Sigala, I.; Wakolbinger, T.; Buber, R. Applying the Delphi method to determine best practices for outsourcing logistics in disaster relief. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2019, 9, 438–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J. Using a modified Delphi methodology to develop a competency model for vet practitioners. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of RM502E-Advanced Study in Research Methods, 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228918594_Using_a_modified_Delphi_methodology_to_develop_a_competency_model_for_VET_practitioners (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.H.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, i–xx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Application of industry 4.0 technologies in SMEs for ethical and sustainable operations: Analysis of challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M. Sustainable venture capital–catalyst for sustainable start-up success? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.S.; Thanki, S.J.; Thakkar, J.J. Ranking of drivers for integrated lean-green manufacturing for Indian manufacturing SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J.; Kammerlander, N. Digital transformation in family-owned Mittelstand firms: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 676–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazilla, R.A.R.; Sakundarini, N.; Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Ayub, N.S.; Olugu, E.U.; Musa, S.N. Drivers and barriers analysis for green manufacturing practices in Malaysian SMEs: Preliminary findings. Procedia CIRP 2015, 26, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Corbo, L.; Caputo, A. Fintech and SMEs sustainable business models: Reflections and considerations for a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Leal Filho, W.; Balogun, A.L.; Foschi, E.; Bonoli, A. Barriers and challenges to plastics valorisation in the context of a circular economy: Case studies from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, S.; Choudrie, J.; Mahbubur, R.M.; Alzougool, B. E-commerce technology adoption: A Malaysian grocery SME retail sector study. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1906–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Hu, Z.; Wiwattanakornwong, K. Unleashing the role of top management and government support in green supply chain management and sustainable development goals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8210–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, M.; Banihashemi, S.; Chileshe, N.; Namzadi, M.O.; Udaeja, C.; Rameezdeen, R.; McCuen, T. BIM adoption within Australian Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs): An innovation diffusion model. Constr. Econ. Build. 2016, 16, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkeș, M.C.; Oncioiu, I.; Aslam, H.D.; Marin-Pantelescu, A.; Topor, D.I.; Căpușneanu, S. Drivers and barriers in using industry 4.0: A perspective of SMEs in Romania. Processes 2019, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Application of DEMATEL approach to identify the influential indicators towards sustainable supply chain adoption in the auto components manufacturing sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2931–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.S. Perceived strategic value-based adoption of Big Data Analytics in emerging economy: A qualitative approach for Indian firms. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 354–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzode, A.G.; Sarma, P.R.S.; Mangla, S.K.; Yuan, H. Modeling the Industry 4.0 adoption for sustainable production in Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2013; Information technology—Security techniques—Information security management systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Agolla, J.E. Human capital in the smart manufacturing and industry 4.0 revolution. In Digital Transformation in Smart Manufacturing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Morales, J.A.; Ararat-Herrera, J.A.; López-Cadavid, D.A.; Camacho-Vargas, A. Breaking the digitalization barrier for SMEs: A fuzzy logic approach to overcoming challenges in business transformation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Nosella, A. The adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in SMEs: Results of an international study. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Carter, L. Social media tools adoption and use by SMEs: An empirical study. In Social Media and Networking: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 791–806. [Google Scholar]

- Sufian, A.T.; Abdullah, B.M.; Ateeq, M.; Wah, R.; Clements, D. Six-gear roadmap towards the smart factory. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Bhamu, J.; Sangwan, K.S. Analysis of barriers to Industry 4.0 adoption in manufacturing organizations: An ISM approach. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Garg, H.; Jain, R. Managing the barriers of Industry 4.0 adoption and implementation in textile and clothing industry: Interpretive structural model and triple helix framework. Comput. Ind. 2021, 125, 103372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour Parkouhi, S.; Safaei Ghadikolaei, A.; Fallah Lajimi, H.; Salimi, N. Smart manufacturing implementation: Identifying barriers and their related stakeholders and components of technology. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Elhusseiny, H.M.; Crispim, J. SMEs, Barriers and Opportunities on adopting Industry 4.0: A Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 196, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Islam, N.; Kazantsev, N.; Romanello, R.; Olivera, G.; Das, D.; Hamzeh, R. Barriers and Enablers for Industry 4.0 in SMEs: A Combined Integration Framework. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024; early access. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, S.; Khan, M.A.; Purohit, J.K.; Menon, K.; Romero, D.; Wuest, T. A smart manufacturing adoption framework for SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrak, V.; Soltysova, Z.; Poklemba, R. Mapping requirements and roadmap definition for introducing I 4.0 in SME environment. In Advances in Manufacturing Engineering and Materials: Proceedings of the International Conference on Manufacturing Engineering and Materials (ICMEM 2018), Nový Smokovec, Slovakia, 18–22 June 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Dalenogare, L.S.; Benitez, G.B.; Ayala, N.F.; Frank, A.G. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Anderson, G. The Economic Impact of Technology Infrastructure for Smart Manufacturing; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016.

- Ghafari, F.; Shourangiz, E.; Wang, C. Cost Effectiveness of the Industrial Internet of Things Adoption in the US Manufacturing SMEs. Intell. Sustain. Manuf. 2024, 1, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzes, G.; Poklemba, R.; Towner, W.T. Implementing Industry 4.0 in SMEs: A focus group study on organizational requirements. In Industry 4.0 for SMEs: Challenges, Opportunities and Requirements; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 251–277. [Google Scholar]

- Häring, K.; Pimentel, C.; Teixeira, L. Industry 4.0 Implementation in Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Recommendations Extracted from a Systematic Literature Review with a Focus on Maturity Models. Logistics 2023, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, D.T.; Modrak, V.; Zsifkovits, H. Industry 4.0 for SMEs: Challenges, Opportunities and Requirements; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de Mattos, C.S.; Pellegrini, G.; Hagelaar, G.; Dolfsma, W. Systematic literature review on technological transformation in SMEs: A transformation encompassing technology assimilation and business model innovation. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 1057–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzyubanenko, A.A.; Korshunov, G.I. Quality control in cyber-physical systems of smart electronics manufacturing. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2094, 042066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; O’Sullivan, E. Addressing the evolving standardisation challenges of ‘smart systems’ innovation: Emerging roles for government? Sci. Public Policy 2019, 46, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, M.; Sekhani, R.; Katiyar, T. The Role of Standards in Diffusion of Emerging Technologies Internet of Things (IoT) (No. 20-r-04); Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER): New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, M.; Michalkova, V. Data analytics in SMEs: Trends and policies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 140, 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.; Weber, P. Trends of digitalization and adoption of big data & analytics among UK SMEs: Analysis and lessons drawn from a case study of 53 SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Cardiff, UK, 15–19 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Baker, J.S.; Song, Z.; Yue, X.G.; Li, W. Government regulatory policies for digital transformation in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises: An evolutionary game analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, H.; Dominic, D.D.; Bhushan, S. The Role of Government Regulations on Manufacturing SME’s Readiness for Industry4. 0 in Malaysia. In International Conference on Machine Learning, Advances in Computing, Renewable Energy and Communication; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, D.; Szabo, R.Z. Driving forces and barriers of Industry 4.0: Do multinational and small and medium-sized companies have equal opportunities? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.I. What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halili, S.H.; Sulaiman, S.; Sulaiman, H.; Razak, R. Embracing industrial revolution 4.0 in universities. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1088, 012111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, H. Education in the Era of IR 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Management and Technology 2018 (ICIMTech 2018), Jakarta, Indonesia, 3–5 September 2018; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Von der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, A.J.; Gross, M.; Hakim, S.; Weinblatt, J. Using the delphi process to analyze social policy implementation: A post hoc case from vocational rehabilitation. Policy Sci. 1993, 26, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, J.; Zalokowski, A.; Hunter, L. Identifying indicators of laboratory management performance: A multiple constituency approach. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-León, I.M.; Olmedo-Cifuentes, I.; Soria-García, J. Could you love your job again? Organisational factors to recover teacher enchantment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 144, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollar, R.E.; Palacios, M.G.; Mangas, M.F.; Fernández, F.A.; Rodríguez, C.M.; Martín, A.C.; Morera, L.T. «safety first»: Design of an anesthetic checklist in pediatrics. Rev. Española De Anestesiol. Y Reanim. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 66, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengual-Andrés, S.; Roig-Vila, R.; Mira, J.B. Delphi study for the design and validation of a questionnaire about digital competences in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2016, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; 11.0 update; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaian, S.A.; Kasim, R.M. Terminating sequential Delphi survey data collection. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2012, 17, n5. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, H.A.; Kalaian, S.A. Which is the best parametric statistical method for analyzing Delphi data? J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salotti, J.M.; Suhir, E. Collaborative Robotics: Application of Delphi Method. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, D.S.; Zhang, Z. Introductory Statistics; Saylor Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J.M.; Buliga, O.; Voigt, K.I. Fortune favors the prepared: How SMEs approach business model innovations in Industry 4.0. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q. New IT driven service-oriented smart manufacturing: Framework and characteristics. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 49, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecklau, F.; Galeitzke, M.; Flachs, S.; Kohl, H. Holistic approach for human resource management in Industry 4.0. Procedia Cirp 2016, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretiakov, A.; Jurado, T.; Bensemann, J. Employee empowerment and HR flexibility in information technology SMEs. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2023, 63, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahi, M.H.; Ahmed, U.; Imroz, S.M.; Shah, S.M.M.; Yong, I.S.C. The flexible HRM and firm performance nexus: Can empowering leadership play any contingent role? Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 73, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.; Oktarina, R.; Reynaldo, V.; Sharina, C. Conceptual development of learning factory for industrial engineering education in Indonesia context as an enabler of students’ competencies in industry 4.0 era. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 426, 012123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, N.M.; Hoang, P.D.; Dung, N.T. Impact of the industrial revolution 4.0 on higher education in Vietnam: Challenges and opportunities. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5 (Suppl. S3), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, J.Y. An integrated model of information systems adoption in small businesses. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1999, 15, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, G.; Faverio, P.; Pigni, F.; Ravarini, A.; Sciuto, D.; Tagliavini, M. Factors affecting ERP system adoption: A comparative analysis between SMEs and large companies. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2005, 18, 384–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Kim, J.; Jahan, S.M. Global value chain-oriented industrialization: Policies revisited. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, 11, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglioni, M.; Ferazzoli, A.; Petrillo, A.; Cioffi, R.; De Felice, F.; Piscitelli, G. Digital manufacturing challenges through open innovation perspective. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 42, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, N.; Seo, Y. The Role of Institutional and Geographic Proximity in Enhancing Creating Shared Value (CSV) Initiatives Within Local Industrial Clusters: A Study of Japanese SMEs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelos, S.; Konstantia, D. Analytical support for identification trends and problems in the development of interaction between stakeholders of education, science and business. Екoнoміка Рoзвитку 2023, 4, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Digital Innovation Clusters Development in the EaP: EU Best Practices in Cluster Management. 2024. Available online: https://eufordigital.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/EU4Digital-II_Report_EU-Best-Practices-in-Cluster-Management.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Dutta, G.; Kumar, R.; Sindhwani, R.; Singh, R.K. Overcoming the barriers of effective implementation of manufacturing execution system in pursuit of smart manufacturing in SMEs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).