Abstract

Exercise-induced fatigue can degrade athletic performance and increase injury risk, yet traditional fatigue assessments often rely on subjective measures. This study proposes an objective fatigue recognition approach using high-fidelity motion capture data and deep learning. This study induced both cognitive and physical fatigue in 50 male participants through a dual task (mental challenge followed by intense exercise) and collected three-dimensional lower-limb joint kinematics and kinetics during vertical jumps. A bidirectional Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU) with an attention mechanism (BiGRU + Attention) was trained to classify pre- vs. post-fatigue states. Five-fold cross-validation was employed for within-sample evaluation, and attention weight analysis provided insight into key fatigue-related movement phases. The BiGRU + Attention model achieved superior performance with 92% classification accuracy and an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 96%, significantly outperforming the single-layer GRU baseline (85% accuracy, AUC 92%). It also exhibited higher recall and fewer missed detections of fatigue. The attention mechanism highlighted critical moments (end of countermovement and landing) associated with fatigue-induced biomechanical changes, enhancing model interpretability. This study collects spatial data and biomechanical data during movement, and uses a bidirectional Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU) model with an attention mechanism to distinguish between non-fatigue states and fatigue states involving both physical and psychological aspects, which holds certain pioneering significance in the field of fatigue state identification. This study lays the foundation for real-time fatigue monitoring systems in sports and rehabilitation, enabling timely interventions to prevent performance decline and injury.

1. Introduction

Exercise-induced fatigue refers to the decline in physiological function following prolonged or high-intensity physical activity, manifesting as reduced muscle strength, impaired neuromuscular control, and diminished cognitive performance. If not identified and managed promptly, fatigue accumulation can impair athletic performance and elevate injury risk [1]. Traditionally, these assessments of exercise fatigue have relied on subjective scales or simple performance metrics. However, these approaches often lack objectivity and sensitivity, making them insufficient for detecting subtle changes in fatigue during movement [2]. By analyzing and quantifying movement, clinicians can identify specific impairments [3]. Similarly, we can determine whether the human body is in a state of fatigue by analyzing and quantifying movement patterns.

The world is witnessing interesting challenges in several fields, including medicine, etc. Solutions to many of these challenges are being developed in the field of artificial intelligence [4]. In recent years, advancements in biomechanical measurement and artificial intelligence have driven a surge of research into objective fatigue detection using sensor data combined with machine learning algorithms. For example, Chang et al. employed wearable sensors to collect movement signals and employed machine learning models to estimate fatigue levels [5]. Deep learning is the fastest-growing field of data science and is built on artificial neural networks to tackle unstructured data [6]. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) models are extensively applied neural network models. Hernandez et al. used 3D motion capture data and RNN models to evaluate fatigue factors in repetitive manual tasks [7]. In another study, Chang et al. collected running data using multi-sensor inertial measurement units (IMUs) before, during, and after fatigue, comparing the performance of various deep learning models for running fatigue classification. Their results demonstrated that deep learning models can achieve strong classification performance, with the inclusion of attention mechanisms in LSTM models further enhancing efficiency in processing raw sequential data [8]. These works highlight the potential of deep learning in exercise fatigue detection.

Meanwhile, fatigue is frequently accompanied by complex biomechanical alterations. For instance, studies examining the effects of running-induced fatigue on vertical jump performance have shown that, under fatigue, lower limb kinematics and kinetics change significantly: during the eccentric phase, increases are seen in ankle inversion angle, minimum knee flexion angle, and peak hip flexion moment; during landing, peak ankle inversion and external rotation angles increase, while peak knee flexion and hip extension moments decrease [9]. These findings indicate that fatigue induces characteristic biomechanical changes in critical movement phases, suggesting that capturing these changes may enable more accurate fatigue detection. However, current research on the changes in movement patterns under combined physical and mental fatigue remains limited, particularly in the application of deep learning models to explosive movements such as jumping.

In sports science, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants have been successfully applied to action state classification. For example, Arias et al. used Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models to identify different movement disorders in postural control tasks for patients with cerebral palsy, achieving an accuracy of 76.43% [10]. More complex deep learning architectures, such as the Convolutional Neural Network and Gated Recurrent Unit (CNN-GRU) model, combining convolutional, recurrent, and attention modules, have reached over 99% accuracy in daily and sports activity recognition tasks [11]. These advances provide a foundation for the application of BiGRU and attention mechanisms in fatigue detection.

Given this context, the present study aims to develop an automated motion fatigue recognition model based on high-fidelity motion capture data and deep learning methods. It primarily addresses two objectives: designing a methodology to acquire high-fidelity motion capture data from both spatial displacement and biomechanical perspectives, and applying innovative deep learning approaches to establish a highly effective motion fatigue classification model while evaluating its performance. We chose a combined physical and cognitive fatigue induction protocol to better simulate real-world fatigue. Both physical and cognitive aspects of fatigue are known to interact and contribute to overall performance decrements. Physical fatigue alone may not capture the full impact on motor performance, especially in tasks requiring sustained attention, such as sports and daily activities. The data was acquired with three-Vicon motion capture and force platforms, and extracted standardized time-series biomechanical features. A Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit model with an attention mechanism (BiGRU + Attention) was developed for fatigue state classification. Its performance was then evaluated against a single-layer GRU baseline under identical conditions. This study hypothesized that incorporating a bidirectional recurrent structure would better capture temporal dependencies in the motion sequence, and that the attention mechanism would highlight key moments with the greatest fatigue-induced changes, thereby improving classification accuracy and model interpretability.

Notably, Chang et al. employed wearable sensors requiring device donning/doffing during testing, rendering them suboptimal for real-world implementation. Both Chang and Hernandez’s investigations were confined to analyzing spatial motion data [5,7]. Furthermore, extant research predominantly emphasizes mental fatigue while inadequately addressing physical fatigue dimensions. Innovatively, this study integrates optical motion capture systems for kinematic position tracking and three-dimensional force platforms for kinetic data acquisition. The fatigue state paradigm of this study concurrently accounts for co-occurring mental and physical fatigue manifestations, implementing a bidirectional GRU model augmented with an attention mechanism for classification. These methodological advances aim to establish a more comprehensive fatigue detection framework.

Additionally, Arias’s comparative analysis of healthy and pathological cohorts revealed more pronounced feature disparities between population types than between fatigue states [10]. Plus, their model architecture omitted attention mechanisms. This study further examines the BiGRU model’s adaptability to fatigue detection challenges when enhanced with attention mechanisms.

In this study, attention weights are analyzed to explore the relationship between model focus and biomechanical changes during fatigue. Our work provides a novel framework for objective fatigue monitoring based on movement data, with potential applications in athletic training monitoring, rehabilitation assessment, and fatigue warning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty healthy male undergraduate students (22.3 ± 0.9 years, 180.4 ± 5.3 cm, 78.6 ± 8.1 kg), all majoring in Physical Education, were recruited. Inclusion criteria required the absence of lower-limb injury within the preceding six months and no neuromuscular disorders. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Approval No. TY2025050), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Data Acquisition

Reflective markers were placed according to the previously established protocol (38 markers) and tracked at 200 Hz using a 10-camera Vicon Vero system (Oxford Metrics Ltd., Oxford, UK) [12]. Simultaneously, ground reaction forces were collected at 1000 Hz by two Kistler 3D force platforms (model 9287C; Kistler Instrumente AG, Winterthur, Switzerland) [13]. Each participant performed three maximal bilateral vertical countermovement jumps with the left foot on one plate and the right foot on the other, hands on hips. All subjects were tested three times before and after fatigue, with the data from the second test being used [14]. Therefore, the model in this study can be considered to have 100 samples, evenly divided into two groups: before fatigue and after fatigue.

2.3. Fatigue Induction and Verification

A combined mental–physical protocol was implemented to induce fatigue [15]. First, each participant completed three baseline assessments in sequence. Then, they performed a 3 min Psychomotor Vigilance Test-Brief (PVT-B), a validated cognitive assessment tool designed to measure mental fatigue objectively by assessing response time, accuracy, and variability [16]. Participants responded to a flashing circle on the screen, with their performance indicating cognitive performance. Following the PVT-B, participants rated their mental fatigue and perceived exertion using two separate Borg CR10 scales: one for mental fatigue (0 = no fatigue; 10 = maximal fatigue) and one for perceived exertion (0 = no exertion; 10 = maximal exertion) [17].

Next, participants completed the TloadDback (TLDB) task, which was designed to induce mental fatigue through a combination of cognitive load tasks. The task involved a 1-back memory updating task and a number decision-making task. In the 1-back task, participants viewed a series of arrows and responded by indicating whether the current arrow matched the previous one. The number decision-making task required participants to decide whether flashing numbers were odd or even, pressing 1 for odd and 2 for even. The task is adaptive: difficulty adjusts based on performance, shortening the inter-stimulus interval when accuracy exceeds 90%, and lengthening it when accuracy falls below 80% [18]. This adaptive mechanism ensures cognitive load is maintained at a challenging level throughout the 15 min task.

After completing the PVT-B and Borg scales, participants watched a standardized video demonstration of the Countermovement Jump (CMJ) and performed several practice trials. Subjective mental fatigue and perceived exertion were assessed pre- and post-intervention via separate Borg CR10 scales, and objective vigilance was measured using a 3 min Psychomotor Vigilance Task B administered on the SOMA-NPT smartphone application (SOMA Analytics, Root, Switzerland).

2.4. Data Preprocessing

Raw marker trajectories and force data were first low-pass filtered with a zero-lag, fourth-order Butterworth filter (cut-off 6 Hz) to remove high-frequency noise [19]. Filtered data were imported into Visual3D (C-Motion, Germantown, MD, USA) to compute three-dimensional joint kinematics (angles) and kinetics (joint moments) for the left and right hip, knee, and ankle. Each joint has three rotational degrees of freedom (x, y, z axes), for which the study computed three kinematic channels (joint angles) and three kinetic channels (net joint moments). Thus, with six joints analyzed (bilateral hip/knee/ankle), each contributing six channels (3 kinematic + 3 kinetic), a total of 36 biomechanical channels were generated per trial Each trial was then temporally normalized to 101 frames, spanning from the moment the participant achieved quiet upright standing on the force plates, through the countermovement jump and landing, up to return to an upright standing posture, thereby ensuring a consistent time base across all jumps.

2.5. Feature Preparation

is a 3 × 1 matrix composed of the specific joint angles of the left hip joint along the l, m, and n rotation axes at the t-th frame during a jumping process, and so forth for other variables. The meaning of this variable can be found in Table 1, as is the case with all other variables appearing in the paper.

Table 1.

Variable Table for Equations (1)–(15).

Let the 3-D joint angle and net moment vectors at frame t be

Concatenate them along the channel axis (including all three rotational axes) to form the 36-dimensional feature at each frame:

and stack over = 101 frames:

To standardize across N trials, reshape

into

compute channel-wise mean and standard deviation , and apply

Finally, reshape back to

for input to the GRU and BiGRU + Attention models.

2.6. Model Architectures

This study developed a bidirectional GRU model with a temporal attention mechanism and compared its performance against a baseline single-layer GRU network. The bidirectional GRU+attention model’s map a trial’s normalized kinematic/kinetic time series to a binary fatigue label.

2.6.1. Single-Layer GRU

Let denotes the dimensionality of the GRU hidden state.

Input: with frames and D = 36 channels.

Recurrent layer: a unidirectional GRU

Read-out: the final hidden state is passed through a fully connected layer

producing logits y ∈ for the pre- vs. post-fatigue classification.

All GRU model parameters were initialized with Xavier uniform, and the GRU recurrence contributes H (3D + H) parameters, and the classifier adds 2H.

2.6.2. Bidirectional GRU + Attention

Bidirectional GRU: Two stacked GRU layers run forward and backward over the sequence:

Concatenated into

Temporal attention:

- 1.

- Scoring

- 2.

- Normalization

- 3.

- Context vector

Classification:

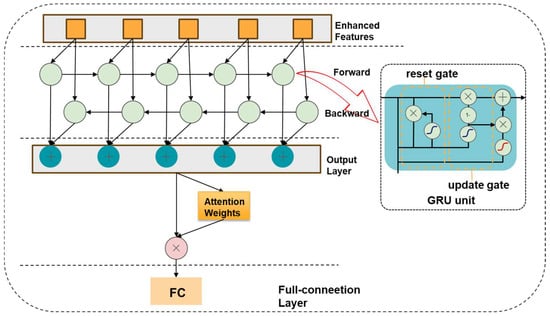

To complement the theoretical derivations, Figure 1 visually illustrates the bidirectional GRU with a temporal attention architecture. It maps the flow of sequential features through bidirectional recurrent layers (capturing forward/backward dependencies) and attention-guided aggregation, aligning with the mathematical formulations for fatigue classification.

Figure 1.

Overview of the model architectures used for fatigue classification.

2.7. Training & Validation

All models were implemented in Python 3.8 with PyTorch 1.13.1 and trained on a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU, Colorful NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 Ti, Colorful Technology Development Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China) To ensure full reproducibility, the random seed was fixed at 42 for dataset splits, weight initialization, and Compute Unified Device Architecture(CUDA) operations. Training minimized the categorical cross-entropy loss using the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate 1 × 10−3, L2 weight decay 1 × 10−5) on mini-batches of size 4; gradients were clipped to a global norm of 5.0, and a dropout layer (p = 0.5) was applied to the GRU outputs immediately prior to the final fully connected layer [20]. All GRU and linear weights were initialized with Xavier (Glorot) uniform, and training proceeded for up to 30 epochs with early stopping if validation accuracy failed to improve for five consecutive epochs (typically between epochs 12–18). The hidden-state dimensionality was set to H = 64, and, for the bidirectional model, the attention dimension to A = 128; the model corresponding to the highest validation accuracy was preserved for final evaluation. Continuous monitoring of the ROC area under the curve (AUC) further ensured robust probabilistic discrimination.

To evaluate both within-sample stability and cross-subject generalization, this study implemented complementary cross-validation schemes. In 5-fold cross-validation (with a total of 100 samples, each fold containing 20 trials balanced between pre- and post-fatigue conditions), trials were randomly partitioned into five equal folds. During each iteration, four folds (80 trials) were used for training, while the remaining fold (20 trials) served as the validation set. The best-performing model from each fold (selected based on validation accuracy) was then used to generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and compute the AUC. We report the mean ± standard deviation of AUC values across all folds.

Additionally, for each held-out test set under both validation schemes, we calculated classification accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. To further analyze model performance, we visualized confusion matrices using heatmaps, enabling detailed inspection of class-specific error patterns [21].

2.8. Evaluation Metrics & Explainability

Model performance was assessed using both threshold-dependent and threshold-independent measures. For each held-out set in the 5-fold cross-validation schemes, we computed classification accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score, where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

To characterize probabilistic discrimination independent of any threshold, this study plotted ROC curves and computed the AUC curves for each fold or subject, reporting the of AUC across all evaluations. Finally, confusion matrices were visualized as heatmaps to reveal detailed class-specific error patterns. All metrics were computed using scikit-learn’s metrics module, ensuring consistency and reproducibility.

To interpret the decision-making process of the BiGRU + Attention model, the learned temporal attention weights for each trial were extracted. During inference, the model’s forward pass was modified to return both the classification logits and the frame-level attention vector α ∈ , where T = 101. Collecting these vectors across all N trials yielded an attention matrix A ∈ × T [22,23].

3. Results

3.1. Fatigue Assessment

The combined fatigue protocol markedly impaired PVT-B performance and elevated self-reported fatigue. Paired-samples t-tests revealed that response variability increased significantly from pre- to post-fatigue (Pre = 23.25 ± 4.94; Post = 80.38 ± 8.97), response accuracy declined (Pre = 92.29 ± 2.63; Post = 86.42 ± 3.89), reaction time slowed (Pre = 328.13 ± 18.55 ms; Post = 357.13 ± 25.51 ms), subjective mental fatigue on the Borg CR10 scale rose substantially (Pre = 1.62 ± 0.82; Post = 6.33 ± 1.09), and perceived exertion also rose (Pre = 0.92 ± 0.58; Post = 8.67 ± 1.01), with all these pre-post differences being statistically significant at p < 0.001. These findings confirm that the dual-task plus burpee protocol effectively induced both cognitive performance decrements and pronounced subjective fatigue.

3.2. Classification Performance

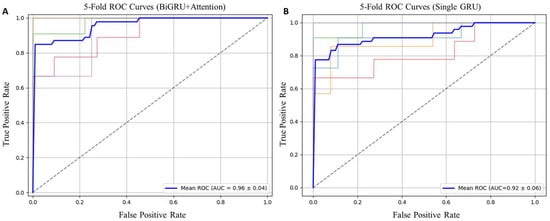

A systematic comparison was conducted between the single-layer GRU model and the BiGRU + Attention model regarding their overall classification performance in exercise-induced fatigue recognition. Under 5-fold cross-validation, the BiGRU + Attention model achieved an average accuracy of 92.0%, precision of 94.0%, recall of 94.0%, F1-score of 94.0%, and an AUC of 96 ± 4%, all of which were notably superior to those of the single-layer GRU model (accuracy: 85.0%, precision: 88.0%, recall: 82.0%, F1-score: 85.0%, AUC: 92 ± 6%). These results can be found in Table 2. Notably, as can be seen from Figure 2, the BiGRU + Attention model demonstrated particularly significant performance in terms of recall and AUC. Both of which reflect discriminative capability, indicating greater sensitivity in detecting fatigue states and reducing the rate of missed detections.

Table 2.

Comparisons of classification performance between single-layer GRU and BiGRU + Attention models.

Figure 2.

ROC curves for the classification of fatigue states using two deep learning models based on 5-fold cross-validation. (A) ROC curves for the BiGRU + Attention model; (B) ROC curves for the single-layer GRU model.

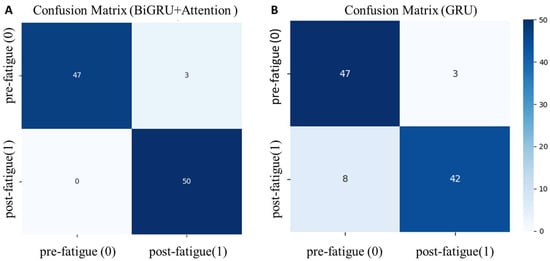

3.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

To further examine the details of model classification, the confusion matrix of the BiGRU + Attention model on the entire sample set was calculated (as shown in Figure 3A, with pre-fatigue as the negative class and post-fatigue as the positive class). As indicated, there were 47 pre-fatigue samples correctly classified as non-fatigue (true negatives, TN = 47) and 3 misclassified as fatigue (false positives, FP = 3). All 50 post-fatigue samples were correctly identified as fatigue (true positives, TP = 50), with no samples misclassified as non-fatigue (false negatives, FN = 0). Based on these results, the following performance metrics were obtained: Precision for the non-fatigue class (class 0): 100%; Precision for the fatigue class (class 1): 94.3%; Recall for the non-fatigue class (class 0): 94.0%; Recall for the fatigue class (class 1): 100%; Overall accuracy: 97.0%.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrices of the BiGRU + Attention model (A) and Single GRU model (B) on the entire dataset. The x-axis denotes the predicted labels and the y-axis denotes the true labels. Each cell shows the sample count for each category (pre-fatigue: 0; post-fatigue: 1). The diagonal elements represent correct classifications, while off-diagonal elements represent misclassifications. The confusion matrix provides a detailed comparison of the classification performance between the two models.

To provide further insight into the classification behavior, the confusion matrix for the Single GRU model on the entire sample set was also calculated (as shown in Figure 3B, with pre-fatigue as the negative class and post-fatigue as the positive class). According to the results, 47 pre-fatigue samples were correctly classified as non-fatigue (TN = 47) and 3 were incorrectly classified as fatigue (FP = 3); among post-fatigue samples, 42 were correctly classified as fatigue (TP = 42), while 8 were misclassified as non-fatigue (FN = 8). The corresponding metrics are as follows: Precision for the non-fatigue class (class 0): 85.5%; Precision for the fatigue class (class 1): 93.3%; Recall for the non-fatigue class (class 0): 94.0%; Recall for the fatigue class (class 1): 84.0%; Overall accuracy: 89.0%.

3.4. Attention Weight Visualization

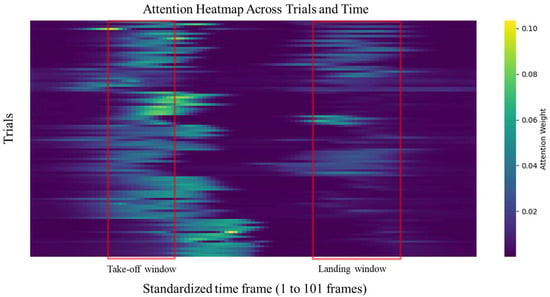

To further elucidate the decision basis of the model during fatigue classification, a systematic analysis was performed on the temporal attention weights learned by the BiGRU + Attention model. Figure 4 presents a heatmap of the attention weight distribution across all jump trials over the entire normalized movement cycle. The results demonstrate that the attention weights assigned by the model exhibit distinct phase-specific peaks along the temporal dimension, rather than being evenly distributed throughout the entire movement. Moreover, the frames corresponding to these phase-specific peaks align precisely with the take-off and landing windows (demarcated by red rectangles in Figure 4). Specifically, most prominent attention peaks are observed near the end of the countermovement phase and during the landing impact phase, whereas the middle phase of the action (such as the flight phase) is characterized by relatively low attention weights.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of temporal attention weights across all jump trials as learned by the BiGRU + Attention model. The x-axis represents the normalized time frames of the action cycle, and each row corresponds to an individual trial. The color intensity indicates the magnitude of the attention weight assigned at each time point, with higher values shown in yellow.

This pattern is highly consistent with biomechanical literature regarding the temporal effects of fatigue, suggesting that these phases are particularly informative for fatigue classification by the model [24]. In addition, the heatmap reveals some inter-individual variability in the temporal location of high-attention peaks; however, the majority of high weights remain concentrated in the aforementioned key movement phases.

4. Discussion

This study developed a deep learning model for exercise-induced fatigue recognition by integrating a bidirectional GRU and an attention mechanism, and demonstrated its effectiveness. The experimental results showed that, compared with the conventional single-layer GRU model, the BiGRU + Attention model achieved significant improvements in fatigue classification accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC. In particular, the BiGRU + Attention model achieved an accuracy of approximately 92% and an AUC of 96% under five-fold cross-validation, indicating that it can reliably distinguish between pre- and post-fatigue movement patterns [5]. By contrast, the single-layer GRU model was able to recognize fatigue to a certain extent (accuracy around 85%) but showed higher rates of false positives and false negatives, suggesting that the extraction of only unidirectional temporal information is insufficient to characterize the complex effects of fatigue. Our findings confirm the advantage of bidirectional recurrent structures for extracting comprehensive temporal features from movement, and the role of attention mechanisms in highlighting key information while suppressing redundant features. These advantages jointly contributed to the improved performance of the model. Such findings are consistent with those of Chang et al., who demonstrated in running fatigue detection that deep learning models can effectively classify fatigue data, and that incorporating attention mechanisms improves the efficiency and effectiveness of recurrent networks in processing temporal data [25]. In the method of this study, the attention mechanism similarly focused on “fatigue hotspot” moments during the movement process (such as the landing phase), which proved critical for fatigue recognition.

Notably, this study adopted a dual-task protocol combining both cognitive and physical components to induce fatigue, which differs from traditional studies that focus solely on physical fatigue. This design more closely approximates the actual conditions of competitive environments, thereby conferring greater ecological validity on the learned movement patterns. However, it is important to recognize that such composite fatigue is more complex, potentially involving the effects of cognitive interference on motor control. Thus, in the classification task, the model was required to capture not only the direct effects of muscle strength decline but also the indirect effects, such as the loss of coordination resulting from central or mental fatigue. The high accuracy achieved in this study suggests that the model successfully captured the combined kinematic alterations resulting from both physiological and psychological fatigue, highlighting the feasibility and effectiveness of using deep learning to detect fatigue states that integrate both physical and mental factors. This finding extends previous work that has mainly focused on single-physiological fatigue, providing a more comprehensive approach for monitoring the mental and physical status of athletes.

The attention interpretability analysis revealed that the model was highly sensitive to features at the end of the countermovement and the moment of landing, which is in close agreement with biomechanical knowledge regarding the effects of fatigue [26]. In the fatigued state, lower-limb power output during takeoff may decrease, and compensatory mechanisms can alter technical details; during landing, due to muscle fatigue, buffering may be insufficient or joint control may be reduced, resulting in altered force impact distribution [27,28]. All these phenomena were reflected in the model’s attention weights.

It is important to note that attention weights do not imply causality, but rather indicate the phases in the movement where the model places more emphasis during classification. Some studies have noted that overall performance indices, such as maximal jump height, may not decline significantly under fatigue, but detailed parameters (e.g., joint angles, joint moments) already show pronounced changes [29,30].

Compared to existing studies, the method of this study offers certain innovations and advantages. Arias et al. also applied BiGRU and other deep networks for posture control classification in cerebral palsy, achieving good results; however, their classification task (healthy vs. types of cerebral palsy) differs substantially from our fatigue recognition task in both population and target. The model achieved higher accuracy for binary fatigue classification in healthy adults, which can be attributed to the use of high-resolution kinematic and kinetic data and the fact that pre- and post-fatigue states represent within-subject changes, allowing the model to learn more uniform patterns from subtle signal differences. Furthermore, in the field of exercise fatigue detection, most prior studies have used data from wearable sensors as input. For example, Chang et al. successfully distinguished different fatigue states during running using IMU data; Youn et al. fused EMG and accelerometer data, employing a CNN-LSTM-attention network to achieve high-precision muscle fatigue detection [5]. This study utilized an optical motion capture system to acquire movement data. To further enhance portability, future research will explore the feasibility of using wearable devices for motion data collection and the potential for embedding built-in models directly on such devices to enable efficient fatigue state detection. Indeed, some researchers have begun exploring multimodal wearable data for fatigue monitoring, obtaining promising initial results [31]. This method should be regarded as a foundational approach under high-precision laboratory conditions, whose discovered biomechanical patterns may inform the development of simplified systems for practical use.

Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, all participants were young and healthy males, resulting in a relatively homogeneous sample. Patterns of fatigue manifestation may differ across sex, age, or training level, and model applicability to other populations requires further verification. Second, only vertical jumping was examined; fatigue characteristics differ across movement types, and models must be retrained for each. Third, the sample size was limited; while cross-validation offers some reliability, small datasets may restrict the learning of more complex patterns. Although we modeled fatigue as a binary pre–post state, fatigue plausibly unfolds along a continuum.

Future work could move beyond dichotomies by adopting graded (ordinal or multiclass) labels or a continuous fatigue index that integrates subjective ratings, cognitive performance, and task outputs [32,33]. Such extensions would benefit from denser measurement stages within the protocol and larger, more diverse samples to ensure stable estimation and external validity. In this context, our binary formulation should be viewed as a pragmatic first step that establishes feasibility while motivating graded or continuous representations in subsequent studies [34,35]. Further integration of other explainable AI methods may provide deeper insight into the relationship between deep model decisions and specific biomechanical changes.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an automated exercise fatigue recognition approach based on a bidirectional GRU with an attention mechanism and validated its effectiveness through vertical jump experiments. High-precision motion capture and force measurement technologies were used to collect comprehensive biomechanical data before and after fatigue, from which 36-dimensional time-series features were constructed. The results demonstrated that the BiGRU + Attention model could identify whether a subject was fatigued with an accuracy exceeding 90%, outperforming traditional unidirectional GRU models. Moreover, the attention mechanism not only improved the model’s discriminative power but also enhanced interpretability—revealing that key movement phases such as countermovement and landing played a decisive role in fatigue classification. In future research, this method could be extended to encompass a broader range of movement types and diverse target populations. Additionally, integrating this method with wearable monitoring devices holds the potential to facilitate the development of portable, real-time fatigue monitoring systems. In the context of sports training and competition, such a method could support coaches and athletes in real-time assessment of fatigue status, optimization of training regimens, and prevention of overtraining and sports injuries. In rehabilitation medicine, it may also facilitate the evaluation of fatigue levels during repetitive functional training, thus informing the adjustment of rehabilitation protocols.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, Y.W. and X.L.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and X.L.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, Y.W. and X.L.; project administration, Y.W. and X.L.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Science, China Jiliang University (TY2025050).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, P.; Gong, Z.; Meng, Y.; Baker, J.S.; István, B.; Gu, Y. The acute influence of running-induced fatigue on the performance and biomechanics of a countermovement jump. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnochie, G.; Fox, A.; Badger, H.; Bellenger, C.; Thewlis, D. Fatigue assessment in distance runners: A scoping review of inertial sensor-based biomechanical outcomes and their relation to fatigue markers and assessment conditions. Gait Posture 2025, 115, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagomarsino, B.; Massone, A.; Odone, F.; Casadio, M.; Moro, M. Video-based markerless assessment of bilateral upper limb motor activity following cervical spinal cord injury. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latreche, A.; Kelaiaia, R.; Chemori, A.; Kerboua, A. A New Home-Based Upper- and Lower-Limb Telerehabilitation Platform with Experimental Validation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 10825–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Lu, A. Identification of runner fatigue stages based on inertial sensors and deep learning. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1302911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, U.B.; Naeem, M.; Stasolla, F.; Syed, M.H.; Abbas, M.; Coronato, A. Impact of AI-Powered Solutions in Rehabilitation Process: Recent Improvements and Future Trends. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 943–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, G. Using Deep Learning for Motion Analysis of 3D Motion Capture Data for Forecasting Motion and Fatigue. Master’s Thesis, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Shardt, Y.A.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C. Deep learning with spatiotemporal attention-based LSTM for industrial soft sensor model development. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 4404–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, S.; Prigent, G.; Stöggl, T.; Martínez, A.; Snyder, C.; Gremeaux-Bader, V.; Aminian, K. Biomechanical response of the lower extremity to running-induced acute fatigue: A systematic review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 646042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Valdivia, J.T.; Gatica Rojas, V.; Astudillo, C.A. Deep learning-based classification of hemiplegia and diplegia in cerebral palsy using postural control analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekruksavanich, S.; Phaphan, W.; Hnoohom, N.; Jitpattanakul, A. Recognition of sports and daily activities through deep learning and convolutional block attention. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Sun, D.; Song, Y.; Fang, Y.; Cen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, Y. Comparison of Landing Biomechanics in Male Amateur Basketball Players with and without Patellar Tendinopathy during Simulated Games. J. Hum. Kinet. 2025, 96, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.P.-Y.; Sterkenburg, N.; Everett, K.; Chapman, D.W.; White, N.; Mengersen, K. Predicting fatigue using countermovement jump force-time signatures: PCA can distinguish neuromuscular versus metabolic fatigue. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, H.; Dallaway, N.; Ring, C. Effects of isolated and combined mental and physical fatigue on motor skill and endurance exercise performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 75, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Yan, S.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, K. Transfer learning-enhanced CNN-GRU-attention model for knee joint torque prediction. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1530950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, J.; González-Ponce, I.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; López-Gajardo, M.Á.; Ramírez-Bravo, I.; Rubio-Morales, A.; García-Calvo, T. Mental Load and Fatigue Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe, K.; Hodder, S.; Lloyd, A. A comparison of methods used for inducing mental fatigue in performance research: Individualised, dual-task and short duration cognitive tests are most effective. Ergonomics 2019, 63, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, L.; Buurke, J.H.; van Beijnum, B.-J.F.; Reenalda, J. Towards machine learning-based detection of running-induced fatigue in real-world scenarios: Evaluation of IMU sensor configurations to reduce intrusiveness. Sensors 2021, 21, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Sardinia, Italy, 13–15 May 2010; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, L.; Gu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yu, P.; Shim, V.; Wang, A.; Fernandez, J. Integrating an LSTM framework for predicting ankle joint biomechanics during gait using inertial sensors. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, I.; Scagnetto, A.; Romani, S.; Barbati, G. Interpretability of time-series deep learning models: A study in cardiovascular patients admitted to Intensive care unit. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 121, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Chang, X.; Fujita, H.; Wu, J. An attention-based deep learning model for multi-horizon time series forecasting by considering periodic characteristic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 185, 109667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Gerritsen, K.G.M.; Litjens, M.C.A.; VAN Soest, A.J. Why is countermovement jump height greater than squat jump height? Occup. Health Ind. Med. 1997, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Amin, O.; Shihada, B. Intelligent wearable systems: Opportunities and challenges in health and sports. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, M.; Groll, A.; Nolte, K.; Willwacher, S.; Alt, T.; Schmidt, M.; Jaitner, T. Predictive modeling of lower extremity injury risk in male elite youth soccer players using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, N.; Onate, J.; Morrison, S. Differential effects of fatigue on movement variability. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, L.J.; Webster, K.E. The effect of fatigue on lower-limb biomechanics during single-limb landings: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, N.M.; Cabarkapa, D.; Eserhaut, D.A.; Yu, D.; Fry, A.C. Repeat sprint fatigue and altered neuromuscular performance in recreationally trained basketball players. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.J.; Sporer, B.C.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sleivert, G.G. Comparison of the Capacity of Different Jump and Sprint Field Tests to Detect Neuromuscular Fatigue. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Xie, K.; Niu, K.; He, J.; Zhang, W. Remote photoplethysmography and motion tracking convolutional neural network with bidirectional long short-term memory: Non-invasive fatigue detection method based on multi-modal fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, P.; Ghosh, D.M.; Ramakrishnan, S. Surface electromyography based muscle fatigue detection using high-resolution time-frequency methods and machine learning algorithms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 154, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuber, P.M.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Rashedi, E. Machine learning-based fatigue level prediction for exoskeleton-assisted trunk flexion tasks using wearable sensors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Osborne, M.; Lee, G.G.; Park, J.C. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Wallace, B.C. Attention Is Not Explanation; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).