Abstract

The integration of a large number of distributed generation (DG) units has altered the grid structure and fault characteristics of distribution networks, posing significant challenges to conventional protection methods. To address this, this paper proposes an adaptive current differential protection method based on comparing the similarity of current waveforms at both ends of a line. After a fault occurs, the current waveforms at both ends of each line are first extracted and normalized. The Fréchet distance algorithm is then introduced to quantify the waveform similarity. Based on the calculated Fréchet distance, the restraint coefficient of the current differential protection is constructed and the protection criterion is improved. Finally, a logic function is derived from the improved criterion. A short-circuit fault within the section is identified when the sum of the logic functions across all sampling points exceeds 50% of the total number of sampling points. A simulation model built in PSCAD/EMTDC is used for validation. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method is unaffected by fault type, transition resistance, fault location, or DG grid-connected capacity, has low data synchronization requirements, and exhibits excellent reliability and selectivity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, increasing energy demands and global warming have made the development of new energy sources particularly important. DG such as solar and wind power has been extensively integrated into distribution networks due to its advantages of being renewable, abundant, and pollution-free [1,2]. This significantly reduces fossil energy consumption and markedly enhances system power supply reliability. However, the integration of DGs has transformed traditional distribution networks from single-source radial networks into multi-terminal supplied networks. Under normal operating conditions, load currents and post-fault short-circuit currents may flow bidirectionally under different operational modes [3,4,5]. The uncertainty in current magnitude and direction affects the operating characteristics of traditional distribution protection schemes, potentially causing maloperation or failure to operate, which in severe cases may endanger equipment, personnel safety, and system stability [6,7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more sensitive and reliable line protection methods in distribution networks.

Currently, protection methods for active distribution networks can be broadly categorized into two types. The first type relies on single-ended measurements and adaptively adjusts protection settings based on fault conditions [8,9]. Although these methods are simple in principle, they suffer from difficulties in protection coordination and high requirements for data processing. Reference [10] derived an adaptive adjustment algorithm for setting impedance, achieving adaptive changes in the protection zone and improving the reliability of traditional distance protection. Reference [11] proposed an adaptive current protection method. Building on traditional current protection, it utilized steady-state fault currents to design an adaptive non-pilot current protection scheme and established criteria for adaptive main and backup protection settings, significantly expanding the protection range of current-based schemes. However, when the penetration level of DG is high, the current setting for this method becomes highly challenging.

The second category uses dual-ended measurements, adapting transmission-line pilot protection methods for distribution networks. Although this type of method requires additional communication channels, it offers absolute selectivity and high reliability, making it a current research hotspot. Reference [12] proposed a d-axis current differential protection method. While this method is unaffected by DG and significantly reduces communication channel requirements, it demands high data synchronization accuracy. References [13,14,15] proposed power differential protection methods, all of which require voltage information from both ends of the protected line. However, as voltage transformers are generally not installed in existing distribution line protection systems, these methods face challenges in practical field application.

Meanwhile, in the time domain, current differential protection methods based on waveform similarity have been widely adopted. Reference [16] utilized the Pearson coefficient and cosine coefficient, respectively, to characterize differences in current waveform variations based on the correlation between currents at both ends. However, when DG exhibits Weak Infeed characteristics, the sampled data on the load side approaches zero, making the formula structures of these algorithms prone to 0/0 division problems. Furthermore, correlation coefficients based on statistical characteristics of data struggle to establish an interpretable mathematical relationship with magnitude and phase differences in time-domain waveforms. The selection of threshold values predominantly relies on simulations and field experience.

In recent years, protection methods based on machine learning have gained significant attention. Reference [17] employs artificial neural networks and SVM algorithms to achieve online identification of equivalent impedance in photovoltaic systems, thereby proposing an adaptive current protection strategy. Reference [18] introduces a multi-class probability SVM model, modeling grid-connected protection as a three-class problem. However, the “black-box” nature of machine learning methods makes the decision-making process difficult to interpret, and their performance is heavily dependent on the completeness of large-scale, high-quality training data. Furthermore, the computational overhead introduced by complex models, high development and maintenance costs, and the difficulty of conducting comprehensive reliability validation due to their lack of interpretability pose significant challenges in protection applications that require high reliability.

To overcome the limitations of existing methods, this paper proposes an adaptive current differential protection method for active distribution networks based on the Fréchet distance algorithm. First, the Fréchet distance is used to quantify the similarity between current waveforms at both ends of each line after a fault occurrence. The restraint coefficient of the current differential protection is then adaptively adjusted based on the calculated Fréchet distance. Subsequently, the differential protection criterion is applied within a rolling time window to identify the faulted section. A simulation model is built in PSCAD/EMTDC, and different fault scenarios are established to verify the effectiveness of the proposed protection method.

Finally, the faulted section is determined by comparing the sum of the logic functions across all sampling points with the total number of sampling points. A simulation model is built in PSCAD/EMTDC, and different fault scenarios are established to verify the effectiveness of the proposed protection method.

2. Analysis of Output Current Fault Characteristics in Differential Protection

2.1. Current Characteristics of Active Distribution Networks with IIDG

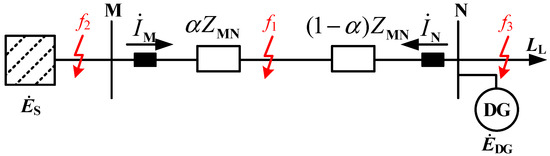

The schematic diagram of the active distribution network containing an IIDG is shown in Figure 1. Es denotes the electromotive force (EMF) of the main system source, EDG denotes the EMF of the IIDG, IM and IN denote the currents at both ends of the protection zone, LL denotes the load connected at the end of the feeder; ZMN denotes the equivalent impedance of feeder MN; f1 denotes the internal fault point, f2 and f3 denote external fault points; α denotes the position coefficient of f1.

Figure 1.

Topology diagram of active distribution network.

Given the widespread adoption of non-effectively grounded neutral points in China’s distribution networks, this paper focuses on analyzing two-phase faults. Influenced by fault resistance and load impedance, a non-metallic fault in an IIDG feeder may cause part of the short-circuit current to bypass the fault point, flowing into non-faulted sections as a through-current. This phenomenon affects the magnitude and phase characteristics of the currents at both ends of the system, potentially leading to the failure of relevant protection schemes.

When the system operates normally or an external fault occurs on line MN, the current flowing through both sides of the protection is through-current. Due to the short length of distribution network feeders, the influence of capacitive current can be neglected. The currents at both ends, IM and IN have identical magnitudes and opposite phases.

When an internal fault occurs on line MN, the output current of the IIDG is controlled by power electronic devices. It can be considered that the IIDG still satisfies the superposition principle and is equivalent to a current source in the fault additional network. Figure 2 shows the equivalent network diagram of the active distribution network containing the IIDG.

Figure 2.

Positive sequence equivalent network of active distribution network with IIDG.

In the figure, Idg denotes the output current of the IIDG; ZM denotes the equivalent impedance on the system side; Zdg denotes the internal impedance of the DG; ZF denotes the fault resistance; and ZL denotes the load impedance.

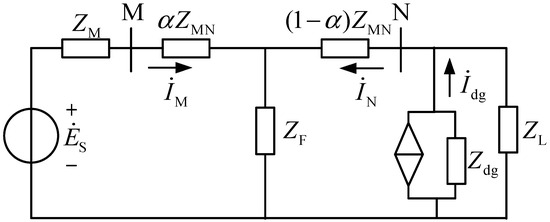

According to the superposition principle, the system in Figure 2 can be decomposed into equivalent networks where the system power source and the IIDG act separately.

In the figure, I1s and I2DG denote the short-circuit currents provided by the system power source and the IIDG, respectively; I2S and I1DG denote the through-currents provided by the system power source and the IIDG, respectively.

The positive direction of current is defined as flowing from the busbar to the line. Thus, from Figure 3, it follows that

Figure 3.

Positive sequence network of the system power source and IIDG acting separately.

From Equation (1) to Equation (3), it can be concluded that the phase angles of the currents IM and IN at both ends are influenced by the through-currents I1DG and I2S in the faulted section, while the magnitudes and phase angles of I1DG and I2S are determined by the system power source, IIDG, load, and fault resistance. Due to the randomness of fault resistance values and fault locations, as well as the limited capacity of grid-connected DG, the currents flowing through both ends of line MN are no longer equal, resulting in significant differences in current waveforms.

First, the difference in the magnitude of the current waveforms at both ends is analyzed. Under normal circumstances, the short-circuit current supplied by the system power source in the distribution network is at least three times the rated current [19], whereas the maximum short-circuit current provided by an IIDG is 1.2 to 2 times the rated current. Therefore, when an internal fault occurs, the magnitude ratio of the fault current components at both ends of the feeder in a distribution network with an IIDG is significantly greater than 1. Here, the amplitude ratio of the fault current components at both ends is defined as ε, with ε > 1. Considering extreme conditions [20], current transformer measurement errors, and a certain margin, εmin ≈ 1.6.

Furthermore, the phase relationship of the current waveforms at both ends is analyzed. Beyond the inverter’s current-limiting control, the IIDG’s fault current is also influenced by Voltage Through (LVRT) requirements [21,22]. The output current of an IIDG under LVRT conditions exhibits the following characteristics: First, within a certain voltage sag range, the IIDG must remain grid-connected and prioritize reactive current output to provide voltage support, per regulatory requirements. Secondly, to maintain the active power balance of the grid and ensure the safe operation of the IIDG, it should inject as much active current as possible within the inverter’s allowable limits. Therefore, the reactive current Iq and the active current Id provided by the IIDG during LVRT can be expressed as follows

In the formula, K is the proportionality coefficient; IN is the rated current of the IIDG; γ is the voltage sag coefficient; Imax is the maximum allowable output current of the IIDG after the fault; Pref is the active power reference value output by the IIDG during normal operation; and UPCC is the voltage magnitude at the DG grid-connection point after the fault.

From Equation (1) to Equation (5), it can be seen that the fault components of the currents on both sides of the upstream feeder of the IIDG are influenced by multiple factors such as fault location, fault type, transition resistance, and the output limits of the IIDG, resulting in extremely complex fault characteristics. When the fault point is far from the IIDG grid-connection point and involves high transition resistance, the short-circuit current provided by the system power source continues to flow downstream to the fault point, while the short-circuit current provided by the DG no longer flows upstream to the fault point, causing a through-current to appear on the N side. In this case, the phase difference θMN of the fault current components between the two sides is large. According to research [23], θMN can reach up to 180°.

2.2. Analysis of Adaptability Issues in Traditional Differential Protection

The entirely different fault characteristics of IIDGs compared to traditional synchronous machines lead to adaptability issues in conventional current differential protection. The principle of traditional current differential protection is described as follows:

In the formula, Idif denotes the operating current; Ires denotes the restraint current; and Kres denotes the restraint coefficient, typically set between 0.5 and 0.8.

It is further derived from Equation (6) that

In the formula, θMN denotes the angle between the short-circuit currents IM and IN at both ends of the protected line; and IM and IN denote the magnitudes of the current phasors at both ends of the protection zone. Let λ = Idif/Ires. Combining with Equation (7), it follows that

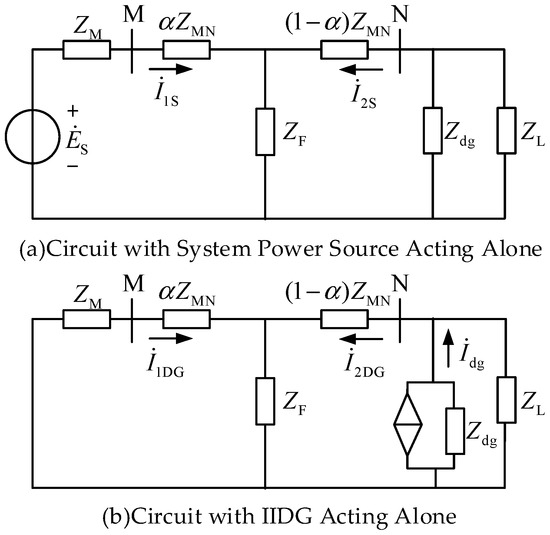

Equation (8) shows the restraint coefficient is determined by ε and cosθMN, where ε relates only to the amplitude characteristics of the currents at both ends, and cosθMN depends solely on their phase angle characteristics. The relationship between the restraint coefficient λ, ε, and θMN is illustrated in the planar graph shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Braking Coefficient Variation Surface.

As can be seen from Figure 4, when a fault occurs downstream of an IIDG, the phase difference between the short-circuit currents at both ends varies significantly, with a maximum value reaching 180° as discussed in Section 2.1. In extreme cases, the amplitude ratio at both ends approaches εmin ≈ 0.67. As the fault condition approaches this extreme state, the operating point moves away from the restraint boundary, ultimately preventing correct protection operation. While reducing the setting value can improve sensitivity for internal faults, an excessively small Kres value may lead to maloperation during external faults, thereby reducing reliability.

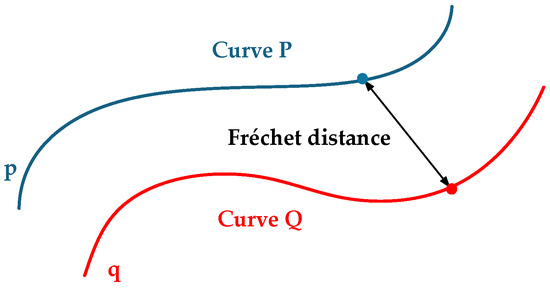

3. Fréchet Distance Algorithm

The Fréchet distance algorithm is a similarity metric in path space proposed by the French mathematician Maurice René Fréchet. Its core concept involves quantifying waveform differences by calculating the minimum value of the maximum distance between corresponding points during the traversal of two curves, as illustrated in the Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

Schematic Diagram of the Fréchet Distance.

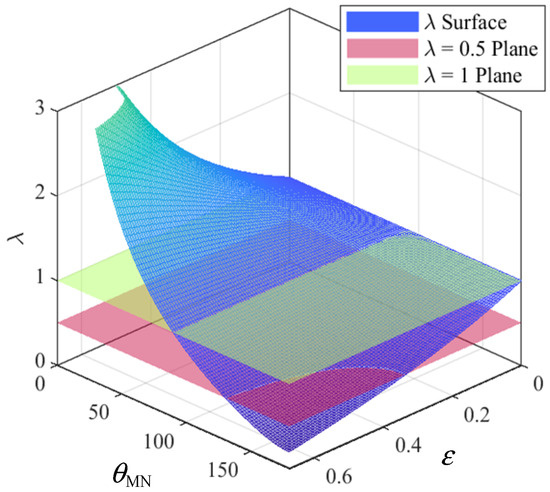

Assume that points p and q start moving along their respective trajectories P and Q at speeds u(t) and v(t), forming two continuous trajectories P(t) and Q(t). For a segment t⋲[t0,t0 + T], the mathematical expression of their Fréchet distance is

In the formula, P(u(t)) represents the position of point p at time t; Q(v(t)) denotes the position of point q at time t; and d signifies the metric function in space; and Inf is the infimum.

The Fréchet distance captures the dissimilarity between two curves through its unique spatio-temporal path matching mechanism. It dynamically searches for the optimal path of point-to-point movement along the two curves, enforcing the minimization of the maximum distance among all matched point pairs. This approach simultaneously captures both global waveform morphology differences and local temporal offsets.

Accordingly, it is introduced into time-domain signals to compare the dissimilarity between current waveforms at terminals M and N of the line.

Two continuous sinusoidal AC current signals, P and Q, are selected. Identical time segments t⋲[t0,t0 + T] are extracted from both, yielding two continuous signal waveforms expressed as follows:

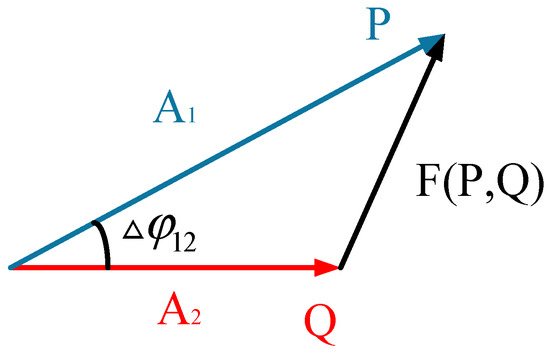

The two signal segments can be regarded as two continuous trajectories starting from the position at time t0 and moving at the same angular velocity ω. Selecting d as the Euclidean distance, the Fréchet distance between P and Q is calculated according to Equation (9) as follows:

Analysis based on Equations (11) and (12) indicates that when the two waveforms are identical, = 0 and the Fréchet distance equals 0. When differences exist between the waveforms, larger discrepancies result in increased values of ∆A12 and ∆φ12, which in turn cause to rise, thereby leading to a larger Fréchet distance. Consequently, the Fréchet distance can be employed to evaluate the dissimilarity between two waveforms.

When the selected time window exceeds half a cycle, the amplitude of the extracted signal becomes independent of time, as shown in Equation (11). Its form is analogous to the Law of Cosines. Therefore, the physical interpretation of the Fréchet distance for sinusoidal signals of the same frequency can be represented by Figure 6. It can be observed that the Fréchet distance between sinusoidal signals P and Q is essentially the magnitude of the vector difference between the two signals.

Figure 6.

Fréchet Distance Physical Vector Diagram.

4. Adaptive Current Differential Protection Method

4.1. Principle of the Adaptive Current Differential Protection Method

To uniformly quantify the current waveform similarity at both ends of each line, we introduce the Fréchet distance into the protection analysis. When an internal fault occurs within the protected line section, the calculated Fréchet distance between the current waveforms i1 and i2 at both ends will be large, as it depends on both the amplitude and phase of the currents (when the sampling period is <10 ms). During normal system operation or external faults outside the protected line section, the calculated Fréchet distance between waveforms i1 and i2 will be small, approaching 0.

Therefore, to further quantify the Fréchet distance, the collected current waveforms are normalized according to Equation (13). This confines the calculated Fréchet distance within the range of [0,1], achieving data standardization while preserving the original relationships between the current waveforms.

M represents the number of the circuit breaker or section switch connected at both ends of the protected line, iMg is the normalized current flowing through terminal M, iM is the current flowing through terminal M before normalization, imax is the maximum current value flowing through terminal M within the sampling time window, and imin is the minimum current value flowing through terminal m within the sampling time window.

Furthermore, the adaptive restraint coefficient for current differential protection is constructed as shown in Equation (14).

In the formula, IMg and −INg represent the normalized current arrays at both ends of the protected line, and F(IMg, −INg) denotes the calculated Fréchet distance between the currents at terminals M and N over one data window. Based on the analysis in Section 3, when the data window length exceeds 10 ms, the result converges to a stable value. Therefore, a data window length of 10 ms is sufficient to capture complete fault information from the currents at both ends.

Unlike traditional methods using a fixed value, the proposed restraint coefficient varies flexibly with the waveform similarity at both line ends. This significantly enhances both the sensitivity and reliability of the protection. When an internal fault occurs, the calculated Fréchet distance approaches 1, causing the adaptive restraint coefficient to approach 0. This ensures the restraint current is significantly smaller than the differential current, enabling reliable protection operation. During normal operation or external faults, the calculated Fréchet distance approaches 0, causing the adaptive restraint coefficient to approach 1. This ensures the restraint current is significantly larger than the differential current, ensuring reliable protection stability (non-operation).

To facilitate the implementation of the protection method, the operating criterion for the adaptive current differential protection method is constructed as shown in Equation (15).

In Equation (15), IM(k) and IN(k) represent the currents at the k-th sampling point of terminals M and N of the protected line, respectively; Idiff(k) and Ires(k) denote the differential current and restraint current at the k-th sampling point, respectively; Iop is the operation threshold. Comprehensively considering influences such as measurement errors and communication errors, Iop is set to 0.01 kA.

Furthermore, to eliminate the impact of randomness at individual sampling points and sampling time asynchronism between protections at both ends of the line on the correct operation of the protection, it is considered to utilize the current data within a sampling time window to construct the protection criterion.

First, define the logic function Sk. Assuming there are n sampling points within one sampling cycle, i.e., k ranges from 1, 2, 3, …, n, the expression for Sk is given below.

Based on the logic function Sk, the current differential protection criterion can be defined as shown below.

When over 50% of the sampling points within one data window satisfy the condition that the differential current exceeds the restraint current, it is determined as an internal fault, and a trip signal is issued to remove the faulted line.

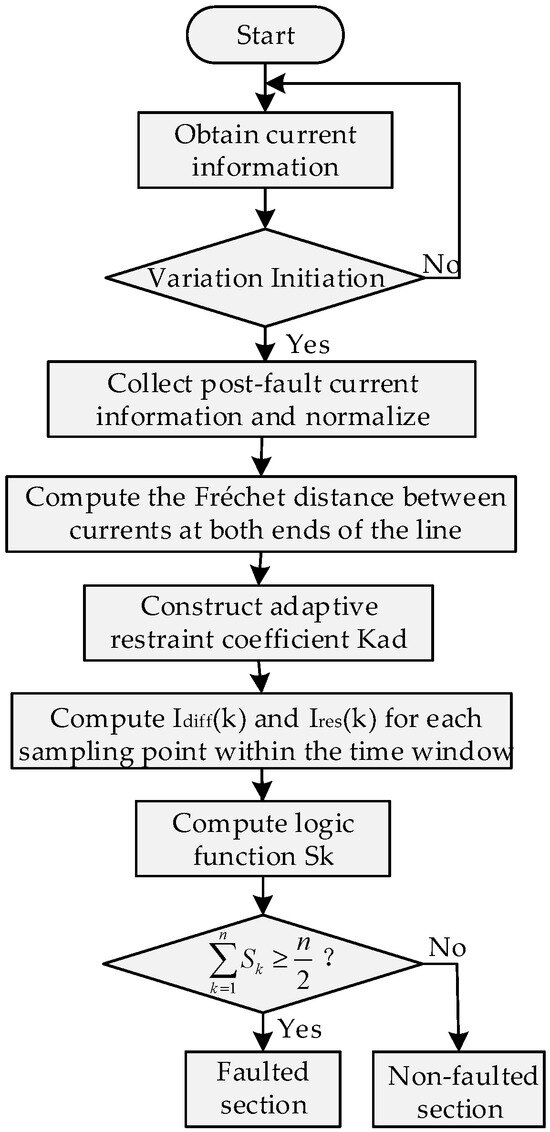

4.2. Overall Procedure of the Adaptive Current Differential Protection Method

Figure 7 illustrates the overall procedure of the proposed method.

Figure 7.

Flowchart of the protection method proposed in this article.

The proposed protection method is implemented using the phase current variation criterion shown in Equation (18) to achieve protection initiation.

In Equation (18), i(t) denotes the phase current at the t-th sampling point, T represents the number of sampling points within one power frequency cycle, and IN is the rated current. To avoid maloperation caused by factors such as line switching or data distortion, protection is initiated only when three consecutive sampling points of any phase current satisfy Equation (18).

After protection initiation, the current information at both ends of each line is first collected and normalized; the Fréchet distance algorithm is then used to quantify the waveform similarity of the currents at both ends of the protected line, from which the adaptive restraint coefficient can be derived. The obtained restraint coefficient and the current data of each sampling point within the data window are substituted into the differential protection operating criterion to further calculate the logic function corresponding to each sampling point. Finally, by comparing the logic function result with the number of sampling points, fault occurrence is determined: when the calculated logic function result is not less than 0.5 times the number of sampling points, it is judged as an internal fault, requiring a trip signal to be issued and the faulted line removed; otherwise, it indicates no fault within the protected section.

To ensure real-time protection performance, the computational complexity is briefly analyzed. The main time consumption lies in calculating the Fréchet distance. Since the current waveforms on both sides are divided into small data windows for comparison, making the overall computational load light and ensuring that real-time protection performance is not affected.

Moreover, our algorithm employs a 10 ms time window. As elaborated in Section 3, for power-frequency AC waveforms, when the time window reaches or exceeds 10 ms, the algorithm solely involves straightforward computations of amplitude and phase without requiring traversal-based solutions. This approach substantially reduces computational complexity while maintaining effective fault feature extraction capabilities.

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. Simulation Model

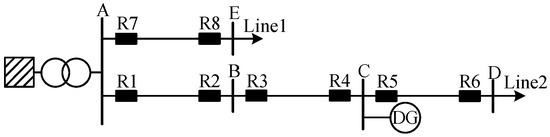

To verify the operating characteristics of the proposed adaptive current differential protection method, a simulation model of the active distribution network was built in PSCAD/EMTDC according to Figure 8. The system voltage level is 10 kV. Two feeders are connected from the busbar, with their parameters selected according to Table 1. The lengths of the two lines are 15 km and 8 km, respectively. Line 1 contains three sections, while Line 2 contains only one section. Each section is named according to the circuit breakers at its ends. The lengths of Sections 1–2, 3–4, and 5–6 are 5 km, 6 km, and 4 km, respectively. Additionally, loads of 4 MW + 1.33 MVAR and 2.7 MW + 1.32 MVAR are connected to the ends of the two lines, respectively. The distributed generation unit is connected to Bus C. Its capacity is adjustable within the range of 1 MVA to 4 MVA. It employs constant power control with an outer power loop and an inner current loop, along with LVRT control. The parameters of its LVRT component are presented in Table 2. The sampling frequency adopted in the simulation presented in this paper is 1 kHz, with the fault inception time set at 2 s.

Figure 8.

Simulation model of active distribution network.

Table 1.

Line parameters.

Table 2.

LVRT parameters.

5.2. Simulation Results Under Different Data Window Lengths

According to the analysis in Section 3, when the data window length exceeds half a cycle, the Fréchet distance result converges to a constant value. To determine an appropriate data window length, tests were conducted to evaluate the impact of 5 ms, 10 ms, and 20 ms windows on protection performance. A three-phase short-circuit fault was set at the midpoint of section 3–4, with the distributed generation unit having a grid-connected capacity of 1 MW and a transition resistance of 0.01 Ω. The simulation results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation results under different data window lengths.

The results indicate that when a 5 ms data window is selected, the Fréchet distance significantly differs from those obtained with 10 ms and 20 ms windows, which aligns with the analysis presented in Section 3. Although the protection system maintains correct operation under all three window settings. However, since the sensitivity of differential protection is inversely proportional to the restraint coefficient Kap, selecting 5 ms reduces sensitivity, and the smaller number of data points in a 5 ms window makes it more susceptible to disturbances. On the other hand, a 20 ms window is not suitable either, as it compromises fast operation and increases computational complexity. Therefore, a 10 ms window is adopted in the simulations.

5.3. Simulation Verification for Typical Internal and External Faults

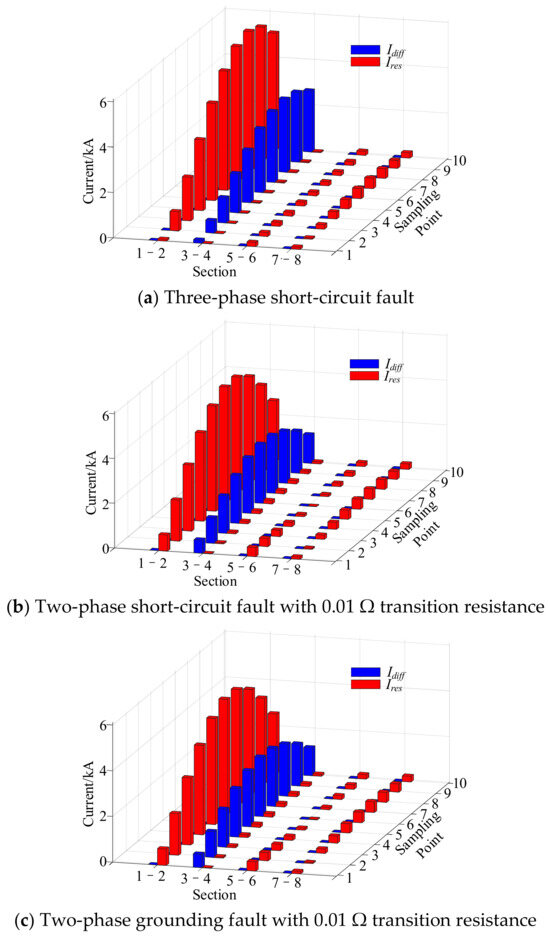

With the simulation settings unchanged, a three-phase short circuit, a two-phase short circuit with a 0.01 Ω transition resistance, and a two-phase-to-ground fault with a 0.01 Ω transition resistance are applied at the midpoint of section 3–4. The distributions of differential current and restraint current under different fault types are shown in Figure 9, and the fault identification results are presented in Table 4.

Figure 9.

Current distribution diagrams under different fault types.

Table 4.

Simulation results when fault occurs in section 3–4.

As can be seen from the simulation data, regardless of the fault type, the Fréchet distance for the faulted section is consistently large, approaching 1, enabling the protection to accurately identify and operate. In contrast, the Fréchet distance for non-faulted sections remains very small, approaching 0, ensuring the protection reliably remains stable.

5.4. Simulation Results Under Different Transition Resistances

To verify the proposed protection method’s tolerance to transition resistance, two-phase short-circuit and two-phase-to-ground faults with different transition resistance values are simulated, and the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Simulation results under different transition resistances.

As the transition resistance increases, the Fréchet distance between the currents at both ends of the protected section decreases. However, the proposed method can still accurately identify faults through the constructed logic function, confirming its strong tolerance to transition resistance.

5.5. Simulation Results Under Different Fault Locations

The distance between the DG grid-connection point and the fault location affects the voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC), which consequently influences the output current characteristics of the DG. Therefore, while maintaining the grid-connected capacity of the DG at 1 MVA, a three-phase short-circuit fault is used as an example. Faults are set at the midpoint of four different sections in the simulation model to further verify the applicability of the proposed protection method. The simulation results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Simulation results under different fault locations.

When the fault location changes, the sum of the logic functions across all sampling points remains well above 50% of the total, confirming that the proposed method is unaffected by fault location and can accurately identify faults.

5.6. Simulation Results Under Different Distributed Generation Capacities

A three-phase short-circuit fault is applied at the midpoint of section 3–4, and the distributed generation capacity is varied to further verify the effectiveness of the proposed protection method under different DG capacities. The simulation results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Simulation results under different distributed power generation capacities.

From the above simulation results, it can be observed that as the grid-connected capacity of DG increases, the Fréchet distance between the current sampling values at both ends of the faulted section decreases accordingly. However, by calculating and summing the logic functions of each sampling point, the proposed method maintains a sum of logic functions that is still significantly greater than the set threshold value. The protection thus retains high sensitivity and can reliably process the fault.

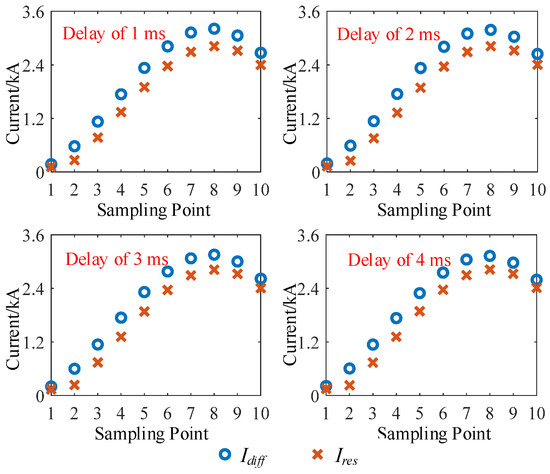

5.7. Simulation Results Under Data Asynchronization Conditions

Traditional current differential protection has high requirements for data synchronization. If the currents at both ends are not sampled synchronously, it is highly likely to cause protection maloperation or failure to operate. To verify the proposed current differential protection method’s tolerance to data asynchrony, the fault settings are kept unchanged while varying the sampling interval between the two sides of the protection by 1 ms, 2 ms, 3 ms, and 4 ms, corresponding to phase angle differences of 18°, 36°, 54°, and 72°, respectively. The simulation results are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Simulation results when data is not synchronized.

As can be seen from Figure 10, when a three-phase short-circuit occurs in the system, even if the sampling times of the currents at both ends of the protected section are not synchronized, the proposed adaptive current differential protection method can still ensure that the differential current exceeds the restraint current for more than 50% of the sampling points, achieving accurate fault identification and clearance.

With a further increase in synchronization error, the simulation results of the first data window after the fault are shown in the Table 8 below. It can be observed that both the Fréchet distance and the sum of the logic functions show a decreasing trend as the synchronization error grows. Nevertheless, the proposed protection method can still correctly identify faults, confirming its strong tolerance to synchronization errors and its low dependence on data synchronization.

Table 8.

Simulation results under different synchronization errors.

As evidenced by the table, synchronization errors do not compromise the correct operation of the protection system. This robustness stems from the algorithm’s primary focus on amplitude discrepancies between the current waveforms at both ends, while phase differences are merely incorporated as a single term in the formulation. Consequently, the computed Fréchet distance metric exhibits minimal sensitivity to phase variations, resulting in exceptional tolerance to synchronization errors.

5.8. Simulation Results Under Different Interfering Signal

With the increasing use of power electronic devices in active distribution networks, the interference signals on the lines are also growing. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the impact of different interference signals on protection performance. The following considerations separately examine the effects of varying levels of noise, current transformer errors, and higher harmonics on protection. The simulation results are shown in Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 9.

Simulation results under different signal-to-noise ratios.

Table 10.

Simulation results under different current transformer errors.

Table 11.

Simulation results under higher harmonics.

The results indicate that the protection can operate correctly under various disturbances. This is because the proposed algorithm is an adaptive current differential protection scheme built upon traditional differential protection principles. The half-cycle Fourier algorithm used for phasor calculation inherently possesses certain capabilities to resist noise and abnormal data. Moreover, the restraint coefficient Kap indicates that the protection sensitivity is only slightly affected and remains at a high level.

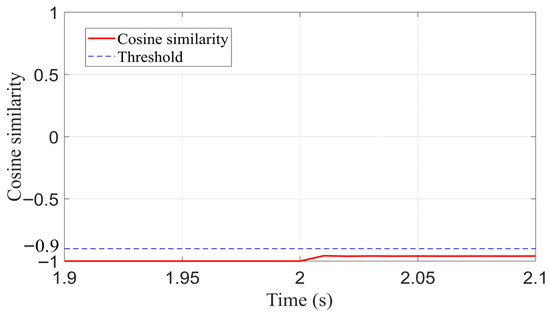

5.9. Comparison with Other Methods

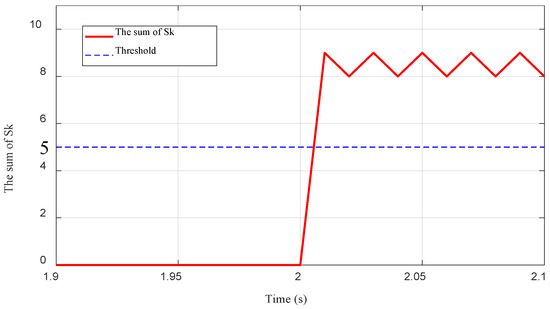

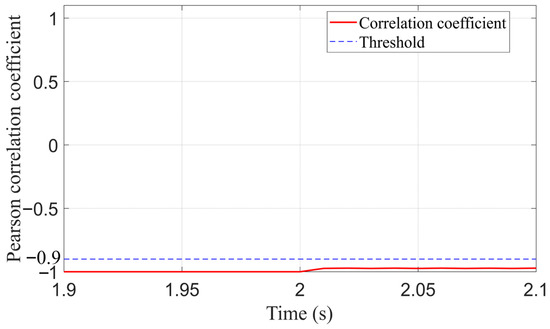

To further validate the novelty and effectiveness of the proposed method, it is compared with the Pearson algorithm and the cosine similarity method. Considering extreme fault conditions, a ground fault with a grounding resistance of 100 Ω is applied 3–4. The simulation waveforms of the three protection schemes are compared as shown in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 below.

Figure 11.

The performance of the proposed method under extreme high-impedance conditions.

Figure 12.

The performance of the Pearson correlation coefficient method under extreme high-impedance conditions.

Figure 13.

The performance of the cosine similarity method under extreme high-impedance conditions.

Both the Pearson correlation coefficient and cosine similarity methods, grounded in statistical correlation theory, rely on normalization to assess the consistency in variation trends or directional alignment between signals. This approach reduces sensitivity to amplitude variations and emphasizes relative waveform changes. However, it may lead to decreased protection sensitivity under high-impedance fault conditions where signal amplitudes are significantly attenuated. In contrast, the Fréchet distance method adopted in this paper comprehensively considers the temporal structure and overall spatial morphology of waveforms, thus offering stronger shape discrepancy discrimination and enhanced anti-interference capability. From the comparative results, it can be concluded that even under extreme high-impedance conditions, the proposed method can rapidly identify faults, demonstrating stronger reliability and effectiveness compared to other approaches. Furthermore, since the algorithm avoids division-by-zero errors during computation, it is more suitable for weak-infeed scenarios involving DG, highlighting its broader applicability and robustness.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces the Fréchet distance algorithm to quantify the similarity between current waveforms at both ends of the protected line. Based on the calculated Fréchet distance, the restraint coefficient of the current differential protection is adaptively adjusted, achieving rapid and precise handling of short-circuit faults in active distribution networks. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Quantifying current waveform similarity and adaptively adjusting the protection criterion accordingly significantly improves sensitivity. Compared with traditional waveform similarity algorithms, it fundamentally avoids the empirical and uncertain nature of threshold selection.

(2) The proposed protection method is unaffected by factors such as fault type, transition resistance, fault location, and DG capacity, and can accurately identify faults in all cases. Furthermore, due to the introduction of the logic function, the method has low requirements for data synchronization. Moreover, compared to Pearson correlation coefficient and cosine similarity methods, it is more suitable for special scenarios like DG weak-infeed and extreme high-impedance conditions, and demonstrates broader applicability.

(3) This paper provides an in-depth theoretical analysis and simulation verification of the proposed protection method but does not include hardware prototype development. Future work will focus on further optimizing the algorithm, extending it to large-scale medium- and high-voltage networks with distributed generation, and developing a prototype for engineering tests to provide stronger practical support for the proposed approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and J.T.; methodology, H.L.; software, Z.S.; validation, Z.S.; formal analysis, C.H. and P.H.; investigation, C.H.; resources, J.T.; data curation, C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and H.J.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and H.J.; visualization, H.L. and C.H.; supervision, J.T., G.Z. and T.D.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Project of Guangxi Power Grid Corporation grant number 046000KK52230003 And the APC was funded by Shandong Shanda Power Technology Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Haiyong Li, Chao Huang, Zizheng Shen, Pengfei Huang and Junyang Tian were employed by company Guangxi Power Grid. Author Tao Du was employed by company Shandong University Electric Power Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors Xiang Li, Haoyang Ju, Guibin Zou declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Barani, M.; Aghaei, J.; Akbari, M.A.; Niknam, T.; Farahmand, H.; Korpås, M. Optimal Partitioning of Smart Distribution Systems into Supply-Sufficient Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, S.F.; Khankalantary, S. Protection of active distribution networks with conventional and inverter-based distributed generators. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 129, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J. Research on Intelligent Distributed Protection Scheme for Distribution Network. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Nanjing, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Hooshyar, A.; Iravani, R. A new directional element for microgrid protection. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 6862–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Ahmed, M.A.; Illindala, M.S. The influence of inverter-based DGs and their controllers on distribution network protection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 50, 2928–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, K.I.; Booth, C.D.; Coffele, F.; Roscoe, A.J. Investigation of the sympathetic tripping problem in power systems with large penetrations of distributed generation. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2015, 9, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Gao, H.; Peng, F.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q. Adaptive Quasi-Power Differential Protection Scheme for Active Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Zhao, Y.S.; Wang, B. Phase differential protection scheme of active distribution network based on optical current transformer. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Singh, R.K.; Choudhary, N.K. Coordination of dual setting overcurrent relays in microgrid with optimally determined relay characteristics for dual operating modes. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2022, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, W.; Zha, W. Adaptive mho characteristic-based distance protection for lines emanating from photovoltaic power plants under unbalanced faults. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 15, 3506–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Phadke, A.G. A novel adaptive current protection scheme for distribution systems with distributed generation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 43, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, J.; Xu, B. Principle and implementation of current differential protection in distribution networks with high penetration of DGs. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, F.; Jamali, S.; Crossley, P.A. Power Differential Protection as Primary. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Developments in Power System Protection (DPSP 2008), Glasgow, UK, 17–20 March 2008; pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.M.A.; Zobaa, A.F.; Ibrahim, D.K.; Awad, M.M. Transmission lines differential protection based on the energy conservation law. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2008, 78, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, H.A.; Taalab, A.-I.; Ahmed, E.S. Investigation of power differential concept for line protection. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, T.S.; Karegar, H.K.; Zeineldin, H.H. Variable tripping time differential protection for microgrids considering DG stability. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y. Research on Adaptive Current Protection for Distribution Networks with Photovoltaic Grid Integration. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P. Research on Grid-Connected Protection for Distributed Generation Based on Machine Learning. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Li, T.; Xue, Y. Distribution Network Relay Protection and Automation; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gao, H.L.; Zhu, G.F. Inverse-Time Current Differential Protection for Active Distribution Networks Considering Characteristics of Inverter-Interfaced Distributed Generation. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2016, 31, 74–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.R.; Wang, G.; Li, H.; Pan, G.; Gao, X. Analysis on the Distribution Network with Distributed Generators Under Phase-to-Phase Short-Circuit Faults. Proc. CSEE 2013, 33, 130–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.P.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, X.; Wang, F.; He, M. Study on Fault Current Characteristics and Fault Analysis Method of Power Grid with Inverter Interfaced Distributed Generation. Proc. CSEE 2013, 33, 65–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Studies on Current Differential Protection and Implementation Technologies in Active Distribution Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).