Multiscale Analysis and Preventive Measures for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mines Using a Multimethod Coupling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Overview

2.1. Landform

2.2. Engineering Geological Conditions

- (1)

- Engineering Geology

- (2)

- Slope Zoning

3. The Slope Analysis Method Is Determined

3.1. Determination of Analysis Method for Current Slope

- (1)

- L1 Section

- (2)

- L2 Section

- (3)

- L3 Section

- (4)

- L4 Section

3.2. The Design Slope Analysis Method Is Determined

- (1)

- Area A

- (2)

- XL2 Section Line

- (3)

- XL3 Section Line

- (4)

- XL4 Section Line

4. Stability Analysis of Slope Limit Equilibrium

4.1. Analysis of Groundwater Seepage

4.2. Initial Boundary Conditions and Parameter Values

4.3. Model Assignment Results

4.4. Scheme Design

4.5. Design Slope Stability Calculation and Analysis

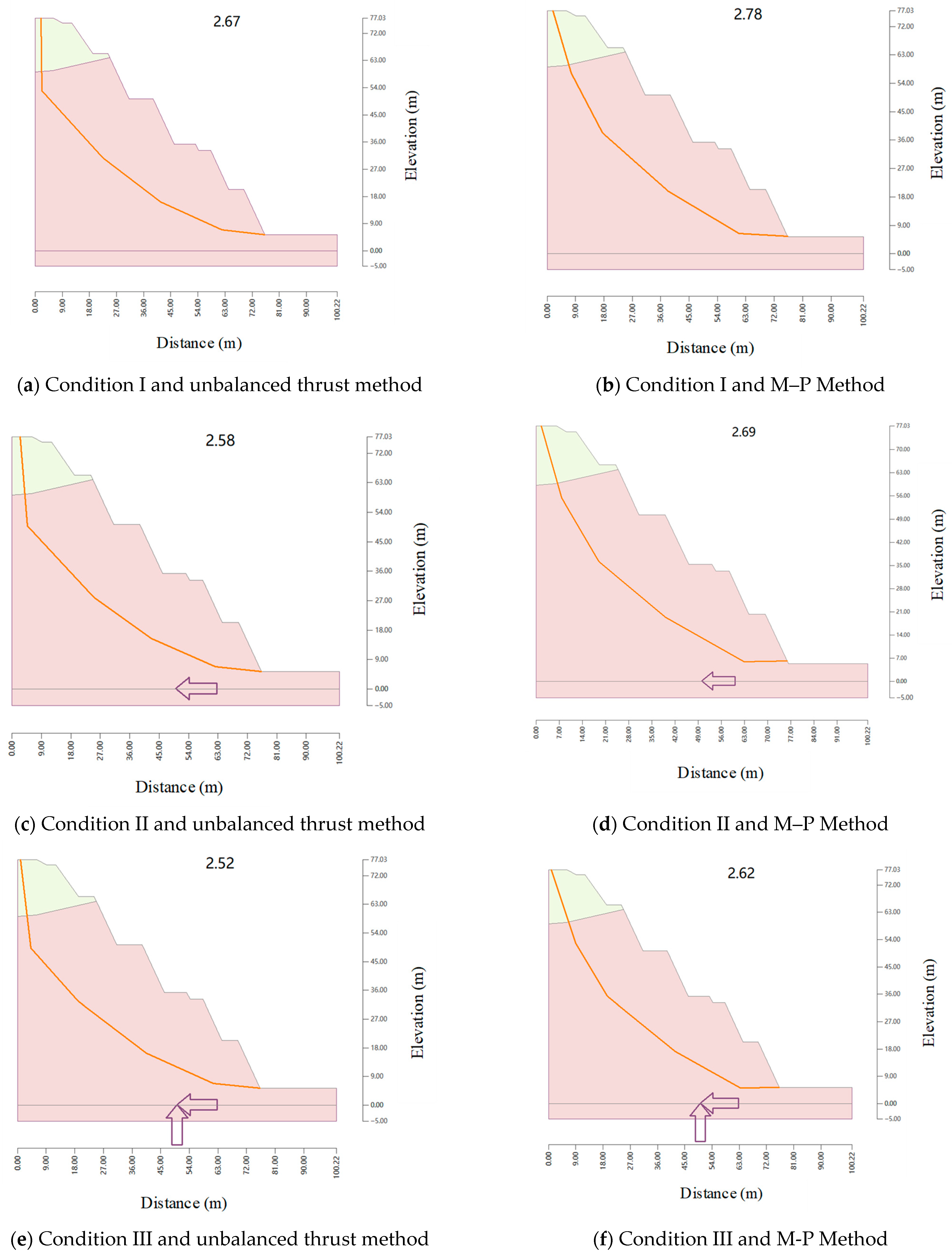

- (1)

- Overall stability analysis

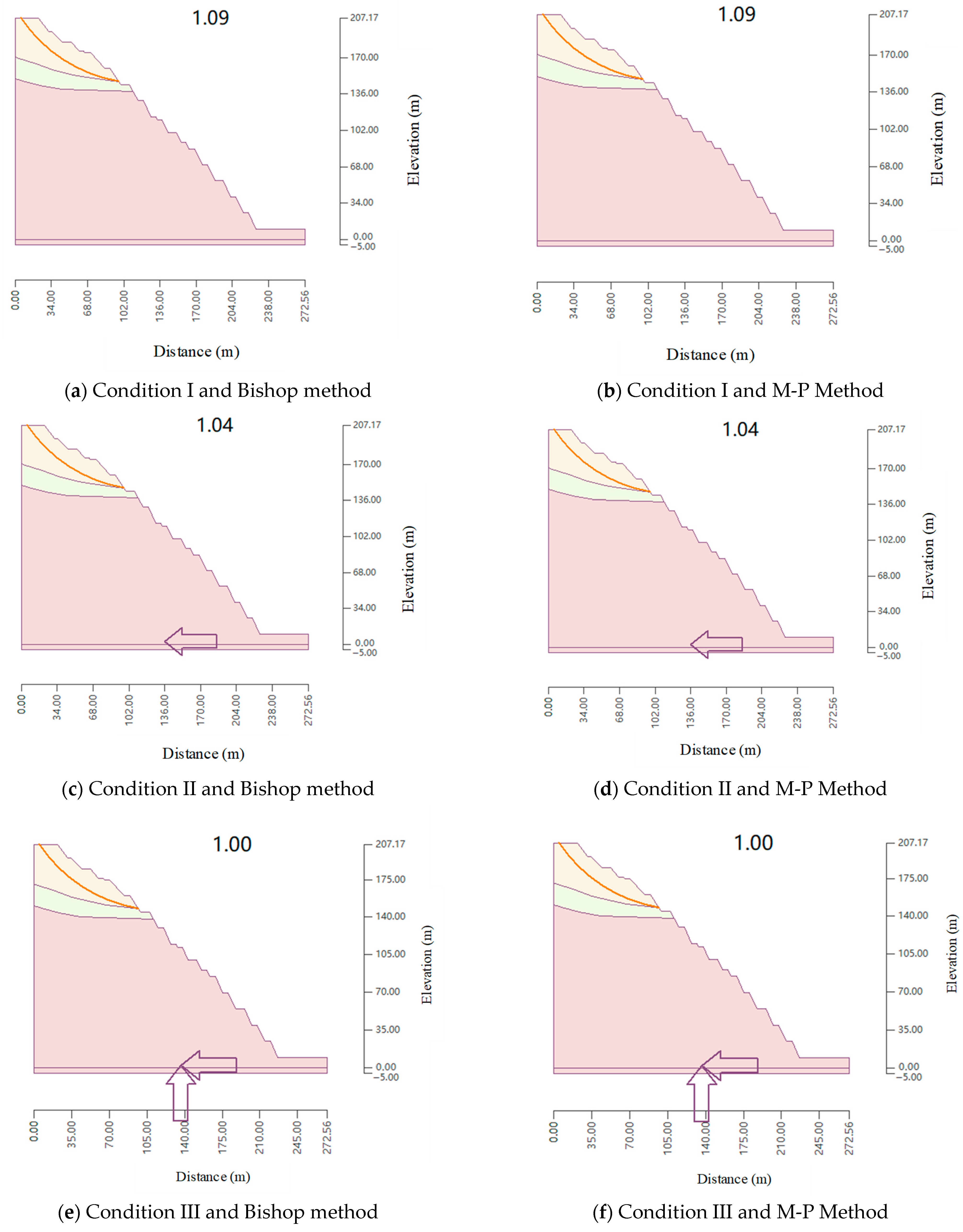

- (2)

- Local stability analysis

- (3)

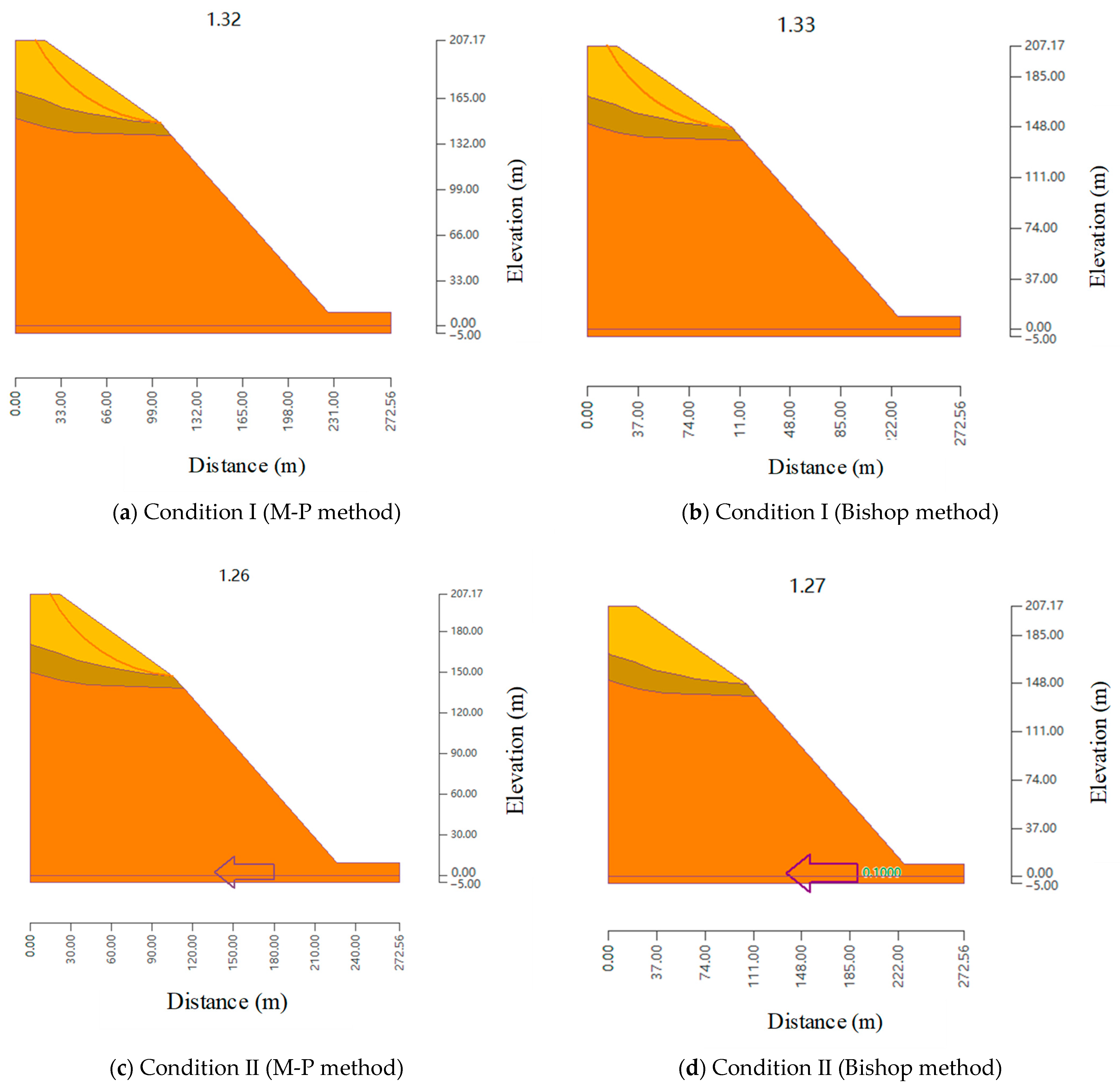

- Calculate the stability of the designed slope

- (4)

- Slope Angle Optimization

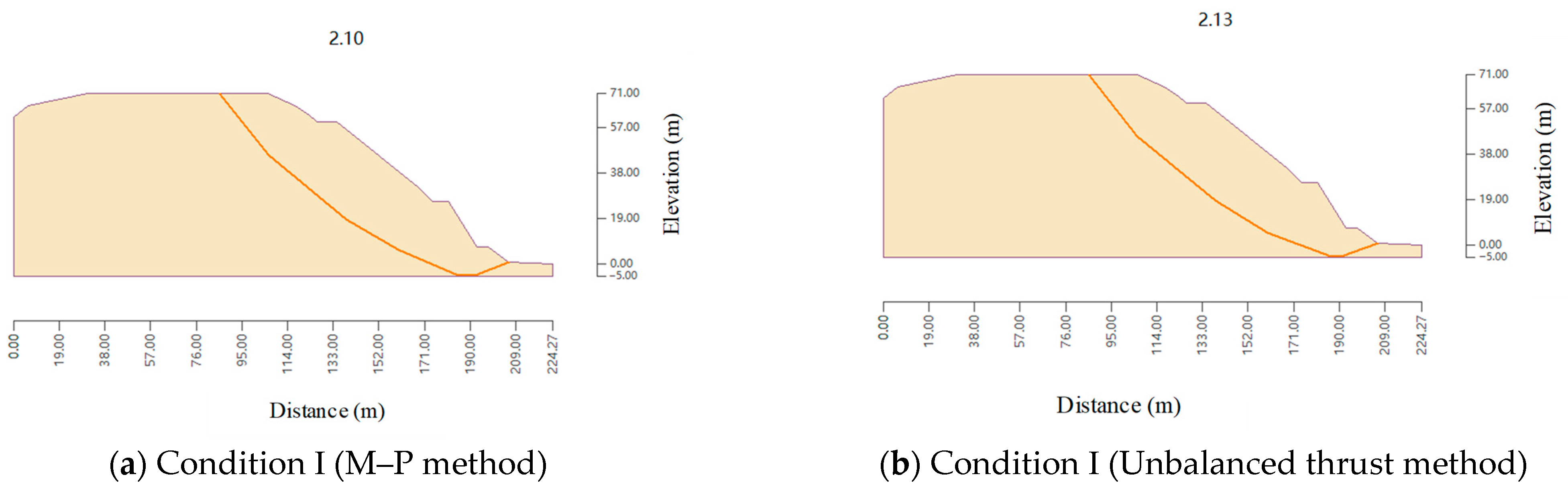

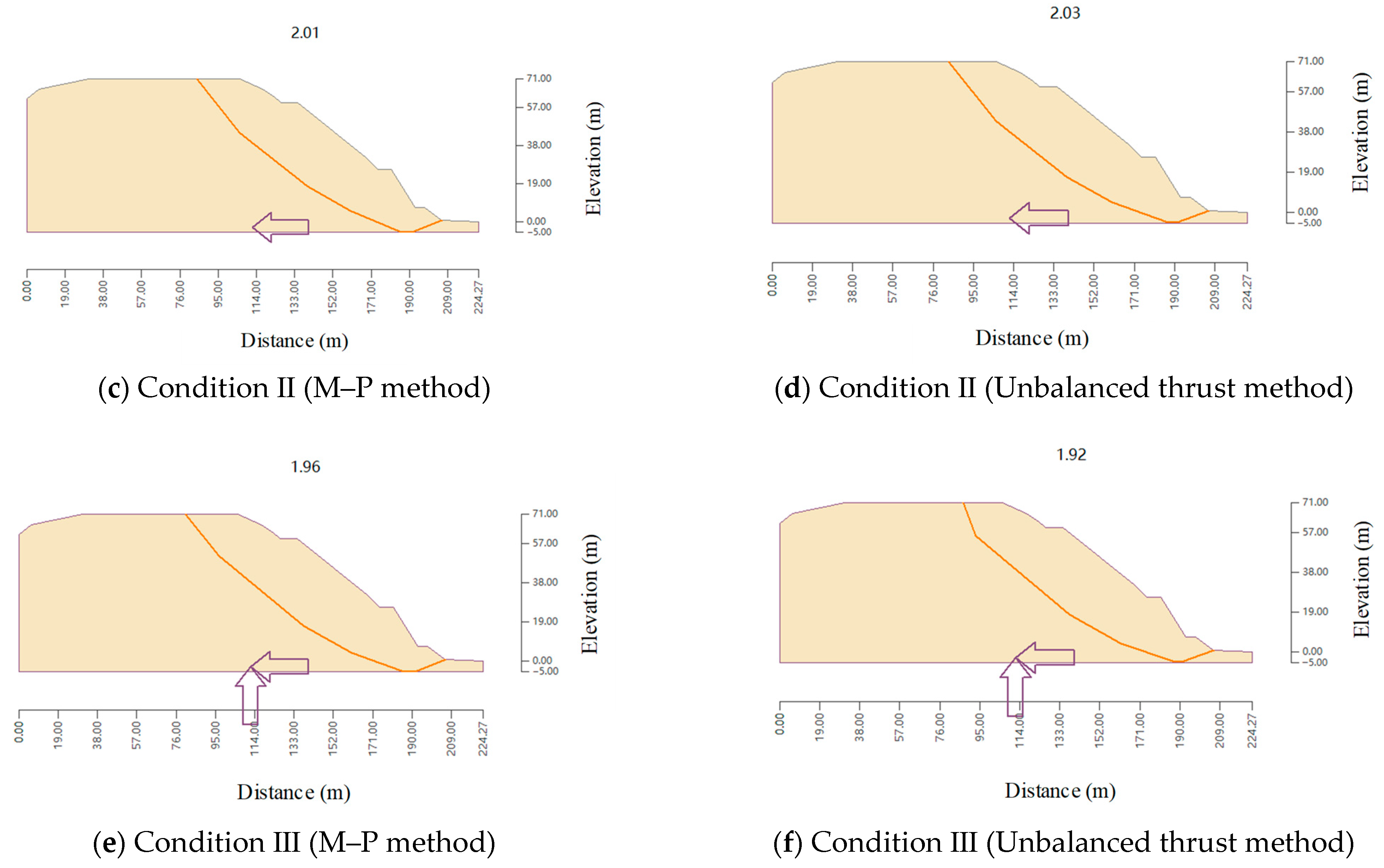

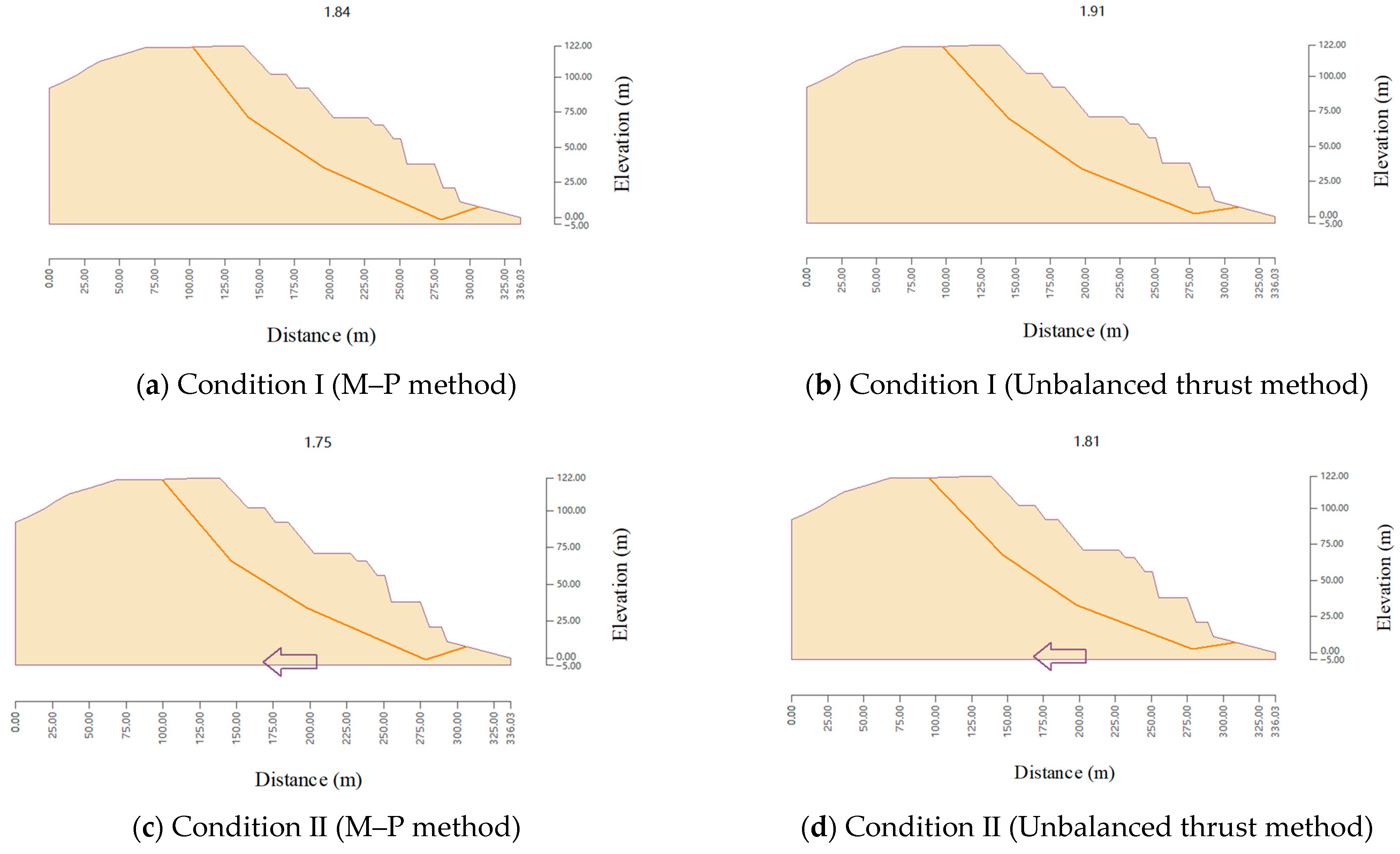

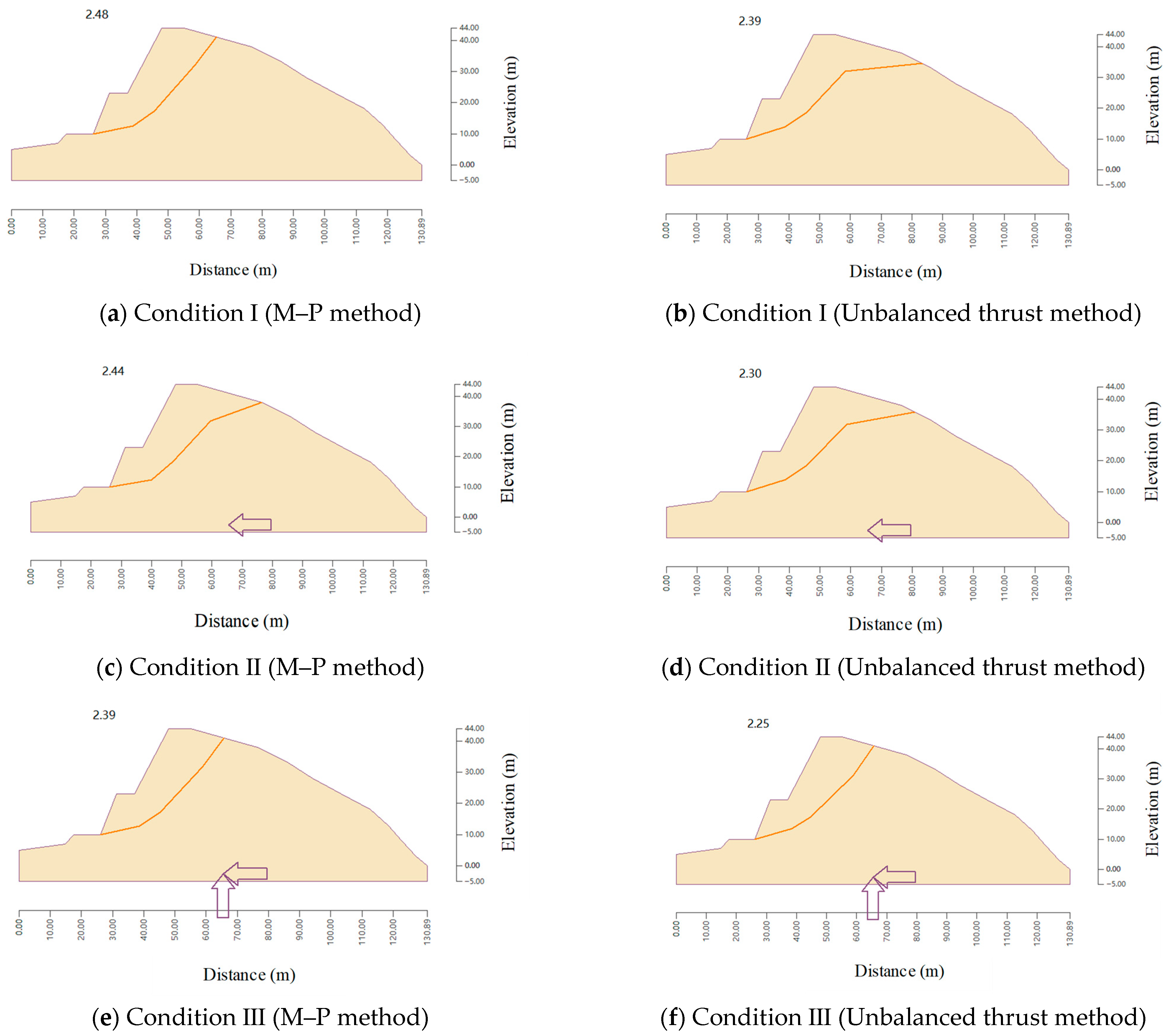

4.6. Current Slope Stability Calculation

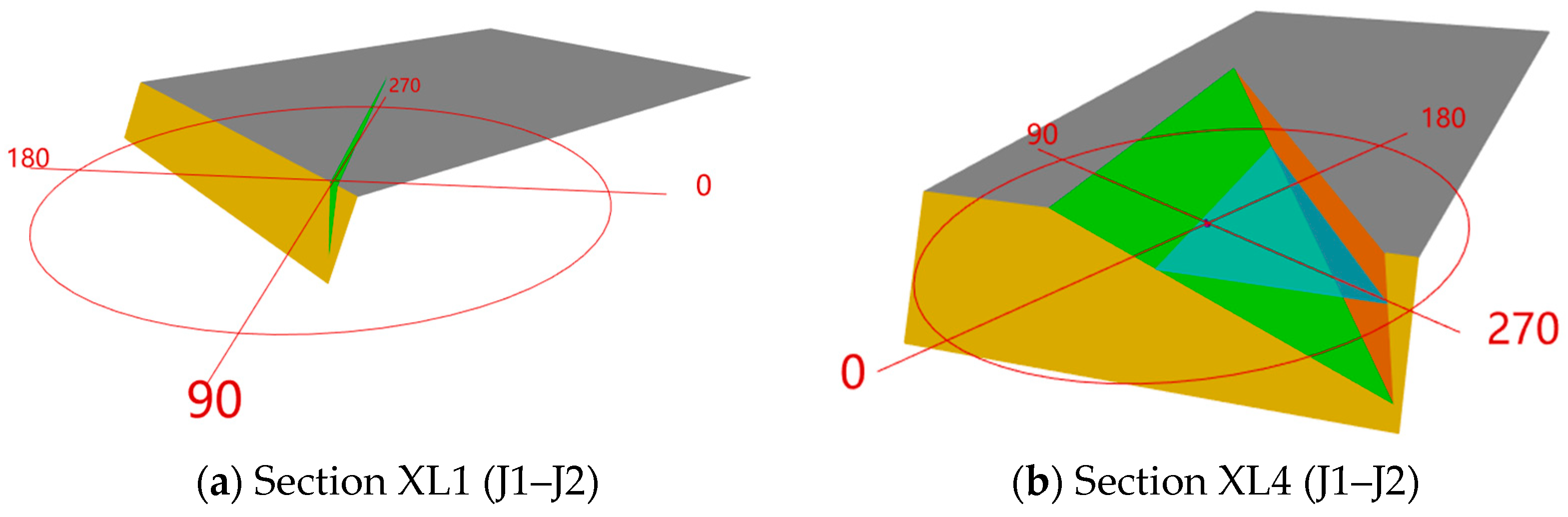

4.7. Pyramidal Analysis

- (1)

- Calculation Theory

- (2)

- Selection of Calculation Parameters

- (3)

- Analysis of Calculation Results

5. Three-Dimensional Stability Analysis of Slope

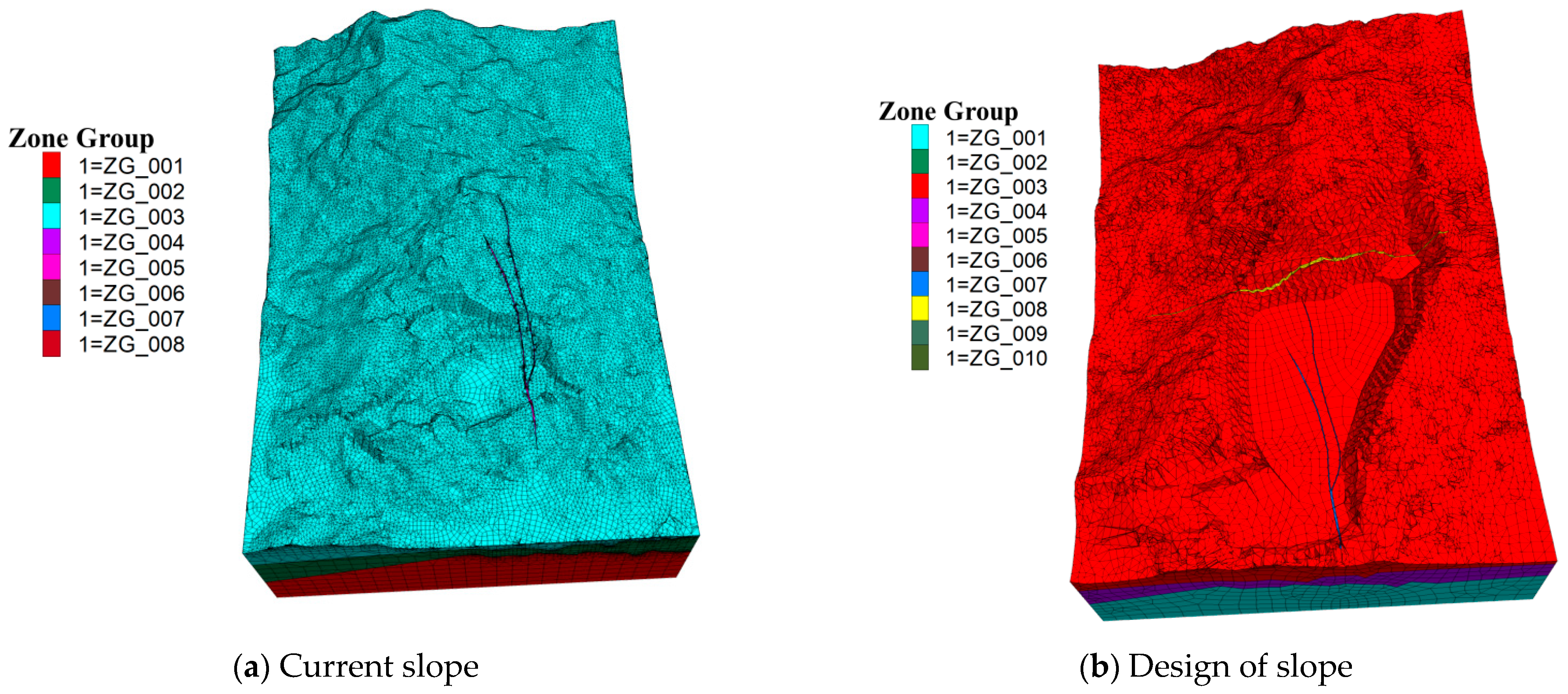

5.1. A Numerical Analysis Model Is Established

5.2. Statistical Analysis of Working Condition and Scheme Design

- (1)

- Self-weight and groundwater: The initial water table was built from engineering survey data. The final slope surface was set as a zero-hydraulic-head boundary. The pore water pressure field under seepage equilibrium was solved to perform self-weight stress and stability calculations, showing the mechanical effect of groundwater on the final slope.

- (2)

- Self-weight, groundwater, and blasting vibration: As the Early Cretaceous granite (with a saturated uniaxial compressive strength of >60 MPa) in the mining area requires blasting for extraction, on the basis of Condition 1, the dynamic vibration load from blasting was added. This quantified how blasting affects the coupled seepage-stress field.

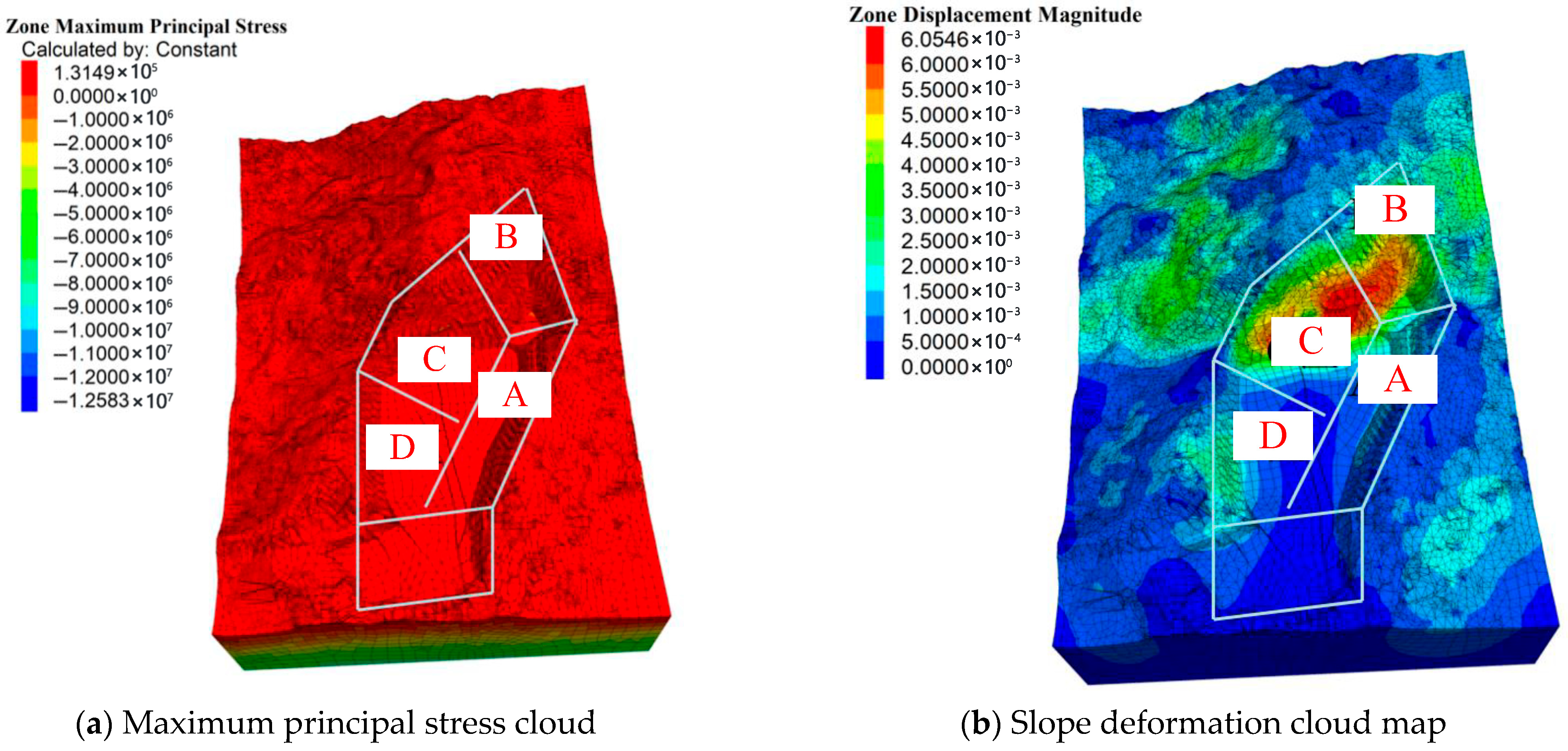

5.3. Analysis of Slope Calculation Results Under Current Situation

- (1)

- Analysis of slope force deformation and failure characteristics under self-weight and groundwater conditions

- (2)

- Analysis of Slope Stress, Deformation, and Failure Characteristics under Blasting Loads

5.4. Analysis of Force Deformation and Failure Characteristics of Slope Design

- (1)

- Analysis of slope force deformation and failure characteristics under self-weight and groundwater conditions

- (2)

- Analysis of force deformation and failure characteristics of slope under blast load

6. Landscape Slope Risk Control Measures

6.1. Slope Reinforcement

6.2. Management Optimization

- (1)

- Geological Dynamic Control Mechanism

- (2)

- Multi-Source Monitoring Coordinated System

- (3)

- Full-Process Slope Control in Mining

7. Discussion

8. Limitations

- (1)

- Complex Geological Conditions: The mining area has complex geological conditions with significant variations in rock mass properties, strong joint and fracture development, and weak structural surfaces like faults. These conditions pose challenges for slope stability analysis, and the limitations of geological exploration may affect the accuracy of the analysis.

- (2)

- Limitations of Analytical Methods: Each analytical method has its limitations. Limit equilibrium methods assume homogeneous rock and soil masses and cannot account for heterogeneity and nonlinearity. Numerical simulation methods require extensive input parameters and have strict requirements for model establishment and boundary conditions. Results from different methods may vary and need to be analyzed comprehensively.

- (3)

- Accuracy and Timeliness of Monitoring Data: The accuracy and timeliness of monitoring data are crucial for slope risk prevention. However, monitoring data may have errors due to equipment precision and environmental interference. Real-time data transmission and processing also have delays, which may affect the timeliness and accuracy of slope stability assessments.

- (4)

- Economic Costs of Risk Prevention Measures: The selection of risk prevention measures must consider economic costs. Some effective measures may be too expensive and exceed the project budget. A balance between safety and cost-effectiveness is needed.

9. Conclusions

- (1)

- In mine slopes, circular and compound failures are the main types, with local areas prone to wedge failures. The existing L1-L4 bench slopes may experience wedge failures. To ensure safety, it is recommended to promptly remove surface loose rocks and implement safety measures such as concrete hardening and rock bolt reinforcement.

- (2)

- Through overall stability calculations of the designed pit slopes under three working conditions scenarios, the overall slope safety factors meet the specification requirements. However, the safety factor for the localized highly weathered layer in Section XL3 does not satisfy the requirements. After optimizing the slope angle of the highly weathered layer in the designed slope Section XL3 from 38° to 37°, its safety factor meets the specification requirements.

- (3)

- Stability analysis of the existing slopes using the limit equilibrium method indicates that the safety factors for slopes L1 to L4 meet the specification requirements. Wedge analysis results for the designed slope Sections XL1 and XL4 show that the safety factors for unstable structural planes within the designed slopes satisfy the requirements under all three scenarios: self-weight combined with groundwater, self-weight alone, and self-weight combined with groundwater, blasting vibration, and seismic loading. However, factors such as blasting and rainfall will continuously reduce the strength of the slope rock mass. Collapse risks in areas with well-developed fractures still require attention. Measures such as concrete hardening and rock bolting should be implemented when necessary to ensure slope safety.

- (4)

- The following evaluation conclusions are obtained through three-dimensional slope stability analysis and calculations: The deformation zones in the existing slopes are mainly concentrated in the middle-lower sections of the high slopes on the western side. The deformation zones in the designed slopes are primarily located in the middle-lower sections of slopes in Zones B and C, with faults situated at the center of the deformation belts. Rainfall, blasting, and seismic action significantly increase the tensile stress on the slope surfaces, leading to increased deformation and exerting a substantial influence. Special attention to risks and enhanced real-time monitoring are required during the excavation of the middle-lower sections of slopes in Zones B and C.

- (5)

- This research provides an integrated multimethodology framework for slope stability assessment that effectively combines traditional analytical methods with advanced 3D numerical modeling. The study’s most notable contribution is the development of a practical approach for identifying critical stability thresholds in complex geological settings, particularly for highly weathered rock formations. The optimization strategy for slope angles in specific geological sections and the implementation recommendations for monitoring and reinforcement measures provide valuable guidance for similar mining operations.

- (6)

- Future research will focus on developing real-time monitoring systems incorporating IoT sensors and wireless communication technology to continuously track slope deformation, groundwater variations, and blasting impacts. We also plan to establish a machine learning-based early warning system that integrates multi-source monitoring data for predictive stability assessment. Additionally, further studies will investigate long-term weathering effects on rock mass properties and the efficiency of various reinforcement strategies under different geological conditions.

- (7)

- In terms of engineering suggestions, the excavation techniques should be optimized by adopting staged excavation with step heights and widths that match the geological conditions to minimize localized stress concentration. For stabilization/remedial works, besides the concrete hardening and rock bolting mentioned above, the implementation of advanced geotechnical structures like soil nail walls or micropile retaining walls should be considered in high-risk zones. Furthermore, the establishment of an efficient drainage system to reduce water pressure on the slopes is essential for maintaining stability. The reinforcement measures should be dynamically adjusted based on real-time monitoring data to ensure the safety of the slopes throughout the mining process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.; Su, W.; Yin, T.; Dan, Z.; Peng, K. Research Progress and Typical Case of Open-Pit to Underground Mining in China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolapo, P.; Oniyide, G.O.; Said, K.O.; Lawal, A.I.; Onifade, M.; Munemo, P. An Overview of Slope Failure in Mining Operations. Mining 2022, 2, 350–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, N.; Shahriar, K.; Afraei, S.; Bakhtavar, E. Evaluating the Impacts of the Transition from Open-Pit to Underground Mining on Sustainable Development Indexes. J. Sustain. Min. 2023, 22, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Qi, X. Freeze–Thaw Damage Characteristics of Soil–Rock Mixtures in Open-Pit Coal Mines and Stability Analysis of Slopes in Discharge Sites Based on Partial Flow Code. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, K.O.; Mwakumanya, M.A.; Tole, M.P. Slope Stability Analysis at Soapstone Mining Sites in Nyamarambe, Kisii County, Kenya. Int. J. Geogr. Geol. Environ. 2023, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Teng, L.; Yang, S. Evolution Characteristics of Mining Fissures in Overlying Strata of Stope after Converting from Open-Pit to Underground. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dintwe, T.K.M.; Sasaoka, T.; Shimada, H.; Hamanaka, A.; Moses, D. Evaluating the Influence of Underground Mining Sequence under an Open Pit Mine. J. Min. Sci. 2022, 58, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei Renani, H.; Martin, C.D. Slope Stability Analysis Using Equivalent Mohr–Coulomb and Hoek–Brown Criteria. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarafza, M.; Akgün, H.; Ghazifard, A.; Asghari-Kaljahi, E.; Rahnamarad, J.; Derakhshani, R. Discontinuous Rock Slope Stability Analysis by Limit Equilibrium Approaches—A Review. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 1918–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, S. Numerical Estimation of Shaft Stability and Surface Deformation Induced by Underground Mining Transferred from Open-Pit Mining in Jinfeng Gold Mine. Minerals 2023, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H. Numerical Investigation on Stratum and Surface Deformation in Underground Phosphorite Mining under Different Mining Methods. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 831856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.; Tan, Z.; Tan, N.; Ahmad, H.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Khurram, S.H.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, N. Remote Sensing and Numerical Simulation for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mining: Case Study of Sijiaying Iron Ore Mine, China. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigiel, A.; Apel, D.B.; Pourrahimian, Y.; Dehghanpour, H.; Pu, Y. Exploring Machine Learning Techniques for Open Stope Stability Prediction: A Comparative Study and Feature Importance Analysis. Rock Mech. Bull. 2025, 4, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskari, T.L. Study on Rheological Constitutive Model of Cililin Volcanic Clay, Indonesia in Relation to Long-Term Slope Stability. GeoMate 2021, 21, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.-L.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, P. Numerical Simulation of Slope Stability during Underground Excavation Using the Lagrange Element Strength Reduction Method. Minerals 2022, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.M.V.; Marciniak, M. Stochastic Rock Slope Stability Analysis: Open Pit Case Study with Adjacent Block Caving. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 5827–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, B.; Yin, T.; Chen, G.; Chen, G. Three-Dimensional Simulation Stability Analysis of Slopes from Underground to Open-Pit Mining. Minerals 2023, 13, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karir, D.; Ray, A.; Kumar Bharati, A.; Chaturvedi, U.; Rai, R.; Khandelwal, M. Stability Prediction of a Natural and Man-Made Slope Using Various Machine Learning Algorithms. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 34, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Yan, J. Numerical Stability Assessment of a Mining Slope Using the Synthetic Rock Mass Modeling Approach and Strength Reduction Technique. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1438277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdvyzhkova, O.; Moldabayev, S.; Bascetin, A.; Babets, D.; Kuldeyev, E.; Sultanbekova, Z.; Amankulov, M.; Issakov, B. Probabilistic Assessment of Slope Stability at Ore Mining with Steep Layers in Deep Open Pits. Min. Miner. Depos. 2022, 16, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.C.; Aryal, M.; Sharma, K.; Bhandary, N.P.; Pokhrel, R.; Acharya, I.P. Development of a Framework for the Prediction of Slope Stability Using Machine Learning Paradigms. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, M.; Dino, G.A.; Oggeri, C. Blasting of Unstable Rock Elements on Steep Slopes. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.-G.; Saroglou, C.; Chen, Y.; Lin, H.; Yong, R. A New Approach for Evaluation of Slope Stability in Large Open-Pit Mines: A Case Study at the Dexing Copper Mine, China. Env. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yuan, L.; Bi, M. Finite Element Analysis of Slope Stability of Fushun West Open-Pit Mine. Teh. Vjesn. 2024, 31, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, D.; Yuan, C.; Nie, W. An Image Recognition Method for the Deformation Area of Open-Pit Rock Slopes under Variable Rainfall. Measurement 2022, 188, 110544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, L.; Dan, Z.; Yin, T.; Chen, J. The Recent Progress China Has Made in Mining Method Transformation, Part I: Shrinkage Method Transformed into Backfilling Method. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Asad, M.W.A.; Topal, E. Timing of Transition from Open-Pit to Underground Mining: A Simultaneous Optimisation Model for Open-Pit and Underground Mine Production Schedules. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, D.; Han, X. Slope Stability Calculation Method for Highwall Mining with Open-Cut Mines. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, A.; Bar, N. The Necessity of 3D Analysis for Open-Pit Rock Slope Stability Studies: Theory and Practice. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2023, 123, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, S.O.; Olaleye, B.M.; Kunkyin-Saadaari, F.; Agyei, G. Slope Stability Assessment of Some Waste Rock Dumps at a Typical Gold Mine in Ghana. Niger. J. Technol. 2023, 42, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50218-2014; Standard for Engineering Classification of Rock Mass. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB 51016-2014; Technical Specification for Slope Engineering of Non-Coal Open-Pit Mines. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, C.; Niu, L.; Xia, P.; Wang, J. Research on Reservoir Landslide Thrust Based on Improved Morgenstern-Price Method. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 35, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-S.; Dai, J.-N.; Jiang, M.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Liang, Y. Imbalance thrust force method for transferring the maximum thrust force. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 44, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Pei, H. Stability analysis of shallow slopes under rainfall infiltration considering tensile strength cut-off. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 171, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Sun, R.; Gu, H.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, Y. Stability analysis of unsaturated soil slopes with cracks under rainfall infiltration conditions. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 165, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50021-2016; Code for Investigation of Geotechnical Engineering. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 50007-2011; Code for Design of Building Foundation. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Niu, G.; Kong, L.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, F. A Modified Method for the Fredlund and Xing (FX) Model of Soil-Water Retention Curves. Processes 2023, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yuan, J.; Cui, J.; Shan, Y.; Yu, S. Mohr–Coulomb-Model-Based Study on Gas Hydrate-Bearing Sediments and Associated Variance-Based Global Sensitivity Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Border Slope Section Number | Representative Section | Partition Basis | Advantage Structure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope Aspect | Corresponding Position | |||

| I | L1 | 247°∠32° | North of the mining area | J1:176°∠89° J2:120°∠83° J3:275°∠72° |

| II | L2 | 355°∠31° | West side of mining area | |

| III | L3 | 327°∠47° | South side of mining area | |

| IV | L4 | 271°∠36° | East side of the mining area | |

| Border Slope Section Number | Representative Section | Partition Basis | Advantage Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Slope Orientation | Height of Slope in Zone (m) | Corresponding Position | |||

| A | XL1 | Dip direction from 210° to 280°, dip angle 60° | 30–60 | East side of the mining area | 177°∠85° 358°∠86° 285°∠74° |

| B | XL2 | Dip direction from 200° to 230°, dip angle 70° | 60–110 | North of the mining area | - |

| C | XL3 | Dip direction from 50° to 75°, dip angle 70° | 160–200 | West side of mining area | 40°∠75° 155°∠42° |

| D | XL4 | Dip direction from 0° to 20°, dip angle 70° | 80–110 | South side of mining area | 119°∠82° 28°∠82° 243°∠18° |

| Name | Natural Density γ (kN/m3) | Bearing Capacity fak (kPa) | Natural/Saturated Uniaxial Compressive Strength Standard Value frk (MPa) | Cohesion c (kPa) | Friction Angle (°) | Compression Modulus Es (MPa) | Osmotic Coefficient k (cm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial fill | 17.5 | 60 | / | 5 | 20 | 2 | 6.16 × 10−3 |

| Completely weathered granite | 19.3 | 380 | / | 30.3 | 22.1 | 8 | 3.50 × 10−5 |

| Strongly weathered granite | 19.6 | 500 | / | 35.0 | 25.0 | 10 | 9.59 × 10−6 |

| Moderately weathered granite | 25.0 | 2500 | 23.94 | 250.0 | 30.0 | / | 5.44 × 10−6 |

| Slightly weathered granite | 26.0 | 9000 | 96.82 | 450.0 | 36.0 | / | 6.16 × 10−3 |

| Safety Grade of Slope Engineering | Safety Factor of Slope Engineering Design | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition I | Condition II | Condition III | |

| I | 1.25~1.20 | 1.23~1.18 | 1.20~1.15 |

| II | 1.20~1.15 | 1.18~1.13 | 1.15~1.10 |

| III | 1.15~1.10 | 1.13~1.08 | 1.10~1.05 |

| Section | Condition | Safety Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbalanced Thrust Method | M–P Method | Select a Value (min{FBishop, FM-P}) | Judge | ||

| XL1 | I | 2.67 | 2.78 | 2.67 | Satisfy |

| II | 2.58 | 2.69 | 2.58 | Satisfy | |

| III | 2.52 | 2.62 | 2.52 | Satisfy | |

| XL2 | I | 2.05 | 2.00 | 2.00 | Satisfy |

| II | 1.97 | 1.93 | 1.93 | Satisfy | |

| III | 1.91 | 1.88 | 1.88 | Satisfy | |

| XL3 | I | 1.87 | 1.83 | 1.83 | Satisfy |

| II | 1.80 | 1.76 | 1.76 | Satisfy | |

| III | 1.75 | 1.71 | 1.71 | Satisfy | |

| XL4 | I | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.26 | Satisfy |

| II | 1.25 | 1.24 | 1.24 | Satisfy | |

| III | 1.22 | 1.21 | 1.21 | Satisfy | |

| Slope Analysis Area | Section | Condition | Safety Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop Method | M–P Method | Select a Value (min{FBishop, FM-P}) | Judge | |||

| Local stability analysis | XL3 | I | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | Not satisfied |

| II | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | Not satisfied | ||

| III | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Not satisfied | ||

| Condition | M–P Method | Bishop Method | Min | Is It Stable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1.32 | 1.33 | 1.32 | True |

| II | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.26 | True |

| III | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.22 | True |

| Section | Condition | Safety Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbalanced Thrust Method | M–P Method | Select a Value (min{FBishop, FM-P}) | Judge | ||

| L1 | I | 2.10 | 2.13 | 2.10 | Satisfy |

| II | 2.01 | 2.03 | 2.03 | Satisfy | |

| III | 1.96 | 1.92 | 1.92 | Satisfy | |

| L2 | I | 1.84 | 1.91 | 1.84 | Satisfy |

| II | 1.75 | 1.81 | 1.75 | Satisfy | |

| III | 1.69 | 1.74 | 1.69 | Satisfy | |

| L3 | I | 2.73 | 2.81 | 2.73 | Satisfy |

| II | 2.58 | 2.65 | 2.58 | Satisfy | |

| III | 2.47 | 2.53 | 2.47 | Satisfy | |

| L4 | I | 2.43 | 2.34 | 2.34 | Satisfy |

| II | 2.44 | 2.30 | 2.30 | Satisfy | |

| III | 2.39 | 2.25 | 2.25 | Satisfy | |

| Type of Structural Surface | Degree of Structural Integration | Friction Angle (°) | Cohesion (kPa) |

| Hard structural surfaces | The bonding structure is well bonded | >35 | 250~150 |

| The structure surface without filling is combined with the general one | 35~27 | 150~100 | |

| Granitic clastic type, poor bonding | 27~18 | 100~50 | |

| Weak structural surfaces | Clay-clastic type, very poor bonding | 18~12 | 50~20 |

| Semi-hard rock formations | <12 | 20~2 |

| Section | Zone | Unstable Structure | Slope Aspect | Structural Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XL1 | A | J1–J2 | 134°∠46° | J1: 177°∠85° J2: 358°∠86° |

| XL4 | D | J2–J3 | 337°∠47° | J2: 28°∠82° J3: 243°∠18° |

| Section | Structural Surface Combinations | Condition | Slippery (kN) | Anti-Slip (kN) | Safety Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XL1 | J1–J2 | I | 1924.22 | 54,903.62 | 28.53 |

| II | 2358.10 | 54,807.11 | 23.24 | ||

| III | 2729.45 | 53,578.94 | 19.63 | ||

| XL4 | J2–J3 | I | 29,239.98 | 53,895.73 | 1.84 |

| II | 33,310.38 | 53,750.28 | 1.61 | ||

| III | 36,430.48 | 52,551.93 | 1.44 |

| Type | Technique | Function | Applicable Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cut the slope and press the toe of the slope | Shaping and clearing | The upper or upper middle part of the slide is cut to reduce the slope angle, so as to reduce the sliding force. | The slide has a certain anti-slide part, which can be used in the landslide section of the mining and transportation equipment in time. |

| Reduce the weight at the foot of the slope | The upper slope of the landslide is cut to reduce the sliding force below, and the soil and rock are piled up in the anti-slide part of the lower part of the landslide to increase the anti-slide force. | There is indeed a sliding resistance part in the lower part of the slide, and it is required that the lower part of the slide has enough width to accommodate the soil and rock in the upper part of the slide. | |

| Increase or maintain the strength of slope rock mass | Dewatering (surface drainage, horizontal borehole drainage, vertical drainage well, underground dewatering roadway drainage) | The groundwater in and near the rock mass is drained, and the dynamic and static water pressure is reduced. The strength of the rock mass is not reduced but increased. | The slope rock mass contains more water, and the bedrock has poor permeability. |

| Explosive blasting of the slip face | The loose blasting of the slip surface increases the friction angle in the rock body near the slip surface and makes the groundwater in the slip body infiltrate into the rock body under the slip bed. | The slip surface is simple, the weak layer is not very thick, and there are no important facilities on the slip body. | |

| Reinforce weak strata with rock | The weak surface is destroyed by mining machinery, and the water-permeable rock is backfilled immediately. After backfilling, the internal friction angle of the rock is greater than that of the weak surface. | A shallow, layered landslide with a single slip surface. | |

| slip casting | The cracks in the rock mass are filled with slurry to improve the overall strength of the rock mass and block the channels of groundwater activity; or the slurry is used to establish a seepage curtain to block the groundwater. | In the rock mass, the rock block is relatively hard, the fracture is developed and connected, and the groundwater is abundant, which seriously affects the stability of the slope. | |

| Artificial construction of retaining structures | The reinforcement/strengthening with large prestressed anchor bolts (cables) | The anchor bolts (cables) were applied and prestressed to increase the normal pressure and anti-sliding force on the sliding surface, thereby enhancing the stability of the rock mass. | The underlying surface is clearly visible, and the rock blocks within the rock mass are relatively hard, which can be used to reinforce deep landslides. |

| Anti-sling pile support | The interaction between the pile and the surrounding rock mass transfers the thrust of the sliding body to the stable rock mass below the sliding surface. | The sliding surfaces are relatively simple and clear, and the integrity of the sliding bodies in the shallow and medium-thick layers is good. | |

| Retaining wall | Build retaining walls at the lower part of the sliding mass to increase the anti-sliding force. | For shallow landslides with relatively loose slopes, there is a need for sufficient construction sites and material supplies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Dou, Z. Multiscale Analysis and Preventive Measures for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mines Using a Multimethod Coupling Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910367

Chen H, Wang B, Dou Z. Multiscale Analysis and Preventive Measures for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mines Using a Multimethod Coupling Approach. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910367

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hengyu, Baoliang Wang, and Zhongsi Dou. 2025. "Multiscale Analysis and Preventive Measures for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mines Using a Multimethod Coupling Approach" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910367

APA StyleChen, H., Wang, B., & Dou, Z. (2025). Multiscale Analysis and Preventive Measures for Slope Stability in Open-Pit Mines Using a Multimethod Coupling Approach. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910367