Abstract

Globally, unhealthy dietary behaviours are consistently seen to significantly contribute to the burden caused by diet-related diseases (DRDs). This is particularly evident among adolescents, a demographic that are at a critical stage of development for lifelong eating habits. This study aims to map the efficacy of post-primary school-based nutritional education (NE) interventions in the modification of adolescent dietary behaviours. A scoping review methodology was implemented, following the Joanna Briggs Institute framework, and adhering to PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Peer-reviewed research from 2015 to 2024 was thoroughly searched using the PubMed and Scopus databases, with inclusion criteria centred on school-based NE interventions aimed at changing post-primary students’ eating habits. In total, 50 studies were selected for analysis, which were then further categorised into five key intervention approaches: knowledge and behaviour-focused programmes, DRD-specific interventions, gamified or interactive learning methods, peer-led or externally facilitated programmes, and school food environment modifications. The findings indicate that structured NE interventions, particularly those incorporating behavioural theories, show positive outcomes in enhancing adolescent dietary knowledge and self-efficacy. The gamified interventions and interactive approaches demonstrated high engagement among participants, but the success of long-term changes was varied. The interventions addressing DRDs, especially obesity, showed significant impacts when combining educational components with structural modifications to school food environments. Peer-led models improved relatability and participation rates but faced challenges in terms of standardisation and repeatability. While school-based NE interventions effectively improve adolescent nutritional knowledge and behaviours, future research should focus on long-term follow-up assessments to determine the sustainability of these changes. These findings offer valuable insights for educators designing curricula, policymakers developing school health strategies, and practitioners seeking to implement feasible, evidence-based nutrition programmes in diverse educational settings.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Unhealthy dietary behaviours are associated with a myriad of diseases and health complications. In spite of this, in many advanced economies, diet quality remains suboptimal, with only a small fraction of the population adhering to established dietary guidelines [1,2,3]. Unhealthy diets primarily consist of processed fast foods and high-sugar snacks, together with excessive consumption of red and processed meats [4,5,6]. Following this type of dietary pattern greatly increases the risk of obesity, alongside cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and many other diet-related diseases (DRDs) [4,7,8]. DRDs are a primary concern for the public health sector, with one in five deaths in adults globally being linked to an unhealthy diet [9,10,11]. Healthcare systems across the world face substantial financial burdens from these conditions while experiencing dramatic increases in both patient illness and death rates [12,13]. The World Health Organisation [14] reports that non-communicable diseases were linked to 75% of global non-pandemic-related deaths in 2021, while inadequate nutrition played a role in many of these fatal outcomes. Nutritional education (NE) and interventions are emerging as pivotal tools for successfully promoting healthier eating habits and could be implemented to reduce the incidence of DRDs [15,16,17]. School-based interventions in particular are theoretically grounded in behavioural change models such as the social cognitive theory (SCT), which emphasises observational learning and self-efficacy [18,19], and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), which highlights the role of intention, attitude, and perceived behavioural control in guiding action [20,21]. These frameworks support the idea that adolescents, when placed in supportive school environments that foster knowledge, motivation, and skill-building, are more likely to adopt and maintain healthier behaviours [18,19,20,21]. It is also important to note that while the term “post-primary setting” is widely used in research to refer to education following the age of 11 or 12, there are international variations in how secondary education is structured. In some countries, secondary education does not begin until the age of 13 or 14. As such, for the purposes of this review, “post-primary” is used to broadly refer to educational contexts serving adolescents, typically between the ages of 12 to 18, to reflect this global variation.

1.2. Influencing Factors and Adolescent Dietary Habits

Adolescence is considered a critical stage for growth and development and can have massive implications for a person’s long-term health [22]. Research has shown that attitudes and behaviours developed in adolescence relating to dietary practices often continue into adulthood [23,24]. One recent study has shown that participants who established positive dietary habits and experiences during mid-adolescence were more likely to maintain a greater interest in following a healthier diet in adulthood, compared to those who did not [24]. If unhealthy eating habits, physical inactivity, and other weight-related issues become the norm from adolescence into early adulthood, young adults, and the future generations they influence as parents, will encounter an elevated risk and prevalence of DRDs [25]. Some of the more common eating habits held by adolescents today include skipping meals, frequent snacking, and dining out, often accompanied by a diet which lacks nutritious foods (fruits, vegetables, and whole grains) and is instead made up of processed foods and drinks high in saturated fats, salt, or added sugars [26,27]. Due to the impressionable nature of children, we must consider that there is a range of factors and influences that could encourage them to succumb to these behaviours.

Advertising campaigns which endorse unhealthy foods and market them to children and adolescents pose a substantial barrier to promoting healthy eating habits. Aggressive advertising, particularly through digital platforms, targets children with products high in sugar, fats, and salts, undermining NE efforts [28,29]. This exposure not only normalises poor dietary choices but also negatively impacts the efficacy of interventions to develop a solid foundation during formative years [30,31]. Socioeconomic factors also play a pivotal role in shaping dietary behaviours among adolescents. Food insecurity and limited access to affordable, nutritious food are prevalent in lower-income communities, resulting in a reliance on unhealthy food options [32,33]. Studies have shown that these disparities can correlate with higher rates of DRDs, emphasising the need for targeted NE interventions particularly aimed at the lower levels of the socioeconomic ladder [34,35]. Cultural influences also shape dietary behaviours by promoting specific food traditions, beliefs, and practices. In some cultures, diets high in carbohydrates or fats are common, and when consumed in excess, greatly contribute to the incidence of DRDs. Adolescents in cultures where large portions and fast food are common may adopt unhealthy habits such as frequent snacking, high fast-food intake, and low fruit and vegetable consumption [36,37].

1.3. The Role of NE in Adolescence

Focusing on adolescents through food literacy and skills-based food interventions is one possible way to instil lifelong healthy eating habits, ultimately reducing the burden of DRDs. At this age, there is typically an evolution from a largely parental-controlled diet to a more self-directed and peer-influenced dietary lifestyle [38,39]. During this period, young people generally assert independence in their dietary decisions and eating behaviours [39,40]. As a result, good NE during this developmental stage might prompt healthy eating behaviours, thereby mitigating subsequent health risks [41,42]. Effective NE programmes equip adolescents with the knowledge and skills necessary to make informed decisions about their diets, which is particularly important given the increasing exposure to unhealthy food options and conflicting dietary information through social media and peer influence [43,44]. Furthermore, these interventions provide a foundation for understanding the long-term consequences of dietary habits, reinforcing the importance of balanced nutrition in preventing the onset of DRDs and promoting overall well-being [45,46]. By encouraging young people to think critically about their food choices, these interventions might act as a deterrent from the allure of unhealthy eating patterns prevalent in adolescence. When grounded in behavioural change theory, these programmes can enhance adolescents’ confidence and motivation to adopt healthier eating patterns, thereby increasing the likelihood of lasting impact.

While the merits of NE are well-established, a thorough examination of intervention strategies specifically aimed at post-primary cohorts is yet to be explored. The primary aim of this paper was to conduct a scoping review of the literature pertaining to school-based food and NE programmes aimed at adolescents and in particular, those focused on altering dietary behaviours in this demographic. The secondary aim was to allow the researcher to comprehensively analyse current data, in order to provide a thorough overview of various intervention components and the outcomes they achieved and identify research gaps which can be further explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Protocol

A systematic scoping review was undertaken for this paper in accordance with the most recent guidance set out by the Joanna Briggs Institute [47], as it provides a comprehensive and well-established methodological framework specifically designed for scoping reviews. In accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews, no formal quality appraisal of included studies was conducted, as the primary aim was to map the extent and nature of research activity rather than evaluate study quality. This framework ensures accuracy in identifying, selecting, and synthesising the relevant literature, and is particularly useful when exploring broad or emerging areas of research, such as post-primary food education interventions [48]. By adhering to these guidelines, the paper could systematically map central themes, identify gaps in the literature, and examine the extent and nature of the research available on the topic [48].

This paper employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist standards [49]. The PRISMA-ScR checklist is internationally recognised for enhancing transparency and consistency in reporting scoping reviews, ensuring that all relevant steps in the research process are documented clearly. This increases the reliability of the review’s findings and allows for easier replication by future researchers. The checklist which indicates compliance with the guidelines, is reported in Table A1 of Appendix A. Although no external registration was completed, an internal protocol was developed to guide the review process, such as eligibility criteria and charting strategy. The researchers acknowledge that the absence of protocol registration limits external reproducibility and transparency.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria outline the specific parameters that determine the publications which would be included or excluded from the scoping review [50]. To be included in the review, the articles must have met pre-determined inclusion criteria, which were English-language, full-text, peer-reviewed journal papers published from 2015 to March 2024 evaluating educational interventions or initiatives implemented in post-primary settings. The decision to focus on this time frame is consistent with other systematic studies examining educational nutrition-focused interventions [51,52], allowing the review to capture the most recent and relevant literature. Limiting the scope to post-primary settings aligns with the research focus on secondary education, ensuring that the interventions target the relevant age group for the paper’s goals. Additionally, the emphasis on evaluating the effectiveness and suitability of educational interventions is crucial, as these criteria provide direct insight into the success and applicability of the interventions in preventing DRDs. For the purpose of this review, “educational interventions” are defined as structured programmes or strategies delivered in school settings with the aim of improving adolescents’ nutritional knowledge, dietary attitudes, and/or eating behaviours. These include, but are not limited to, curriculum-integrated lessons, interactive workshops, gamified learning modules, peer-led sessions, and environment-focused education, such as canteen adjustments supported by educational messaging.

Studies that were non-peer-reviewed literature, dissertations, conference abstracts, and publications not available in English were excluded. Limiting to English-language publications is a practical decision, as translating studies could introduce bias or inaccuracies, though the researcher acknowledges that this may limit some potentially relevant findings. Interventions which failed to involve a post-primary or equivalent cohort, or which did not involve educational interventions related to diet/health-related diseases, were also not considered for inclusion. This ensured that the scope of the review remained focused and relevant, specifically targeting interventions applicable to this paper’s primary objectives [53].

2.3. Search and Information Sources

Articles from two scientific databases (PubMed and Scopus) were retrieved using the keywords and MeSH Terms seen in Table 1 utilising logical operators AND or OR. These two databases were chosen as they are the ones most frequently used from a food and education perspective [54,55]. The search was conducted in March 2024, and the search results were transferred into Rayyan software (https://www.rayyan.ai).

Table 1.

Search terms derived from associated concepts.

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

All articles collected were extracted to the Rayyan software, which identified duplicates that were then screened and removed. Rayyan is widely recognised for its ability to streamline the systematic review process, especially in terms of screening and managing large volumes of references [56]. Its duplicate identification feature reduces manual labour and ensures efficiency by automatically flagging multiple entries of the same publication, maintaining the integrity of the dataset.

The decided-upon inclusion and exclusion criteria were used by the primary researcher (KM) to screen both the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles. This step ensures concise study selection of relevant studies before moving on to full-text analysis, providing an efficient method to refine the dataset. Two secondary researchers (AM and LM) also screened all titles and abstracts, adding an extra layer of reliability to the process. Using two reviewers helps minimise bias and errors, which aligns with best practices for systematic reviews [57]. All researchers discussed and deliberated on any conflicting decisions and came to a consensus on whether to include each journal, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, to prevent bias.

2.5. Data Charting Process and Data Items

The included studies were descriptively analysed by a researcher (KM) using a customised electronic data sheet using the following headings: author, publication year, title, country, study design, objective, intervention details, outcomes measured, duration, and results (Table 2). This standardised approach ensures consistency across studies, reducing bias and enabling a systematic comparison of data.

Table 2.

Data extracted from included articles.

3. Results

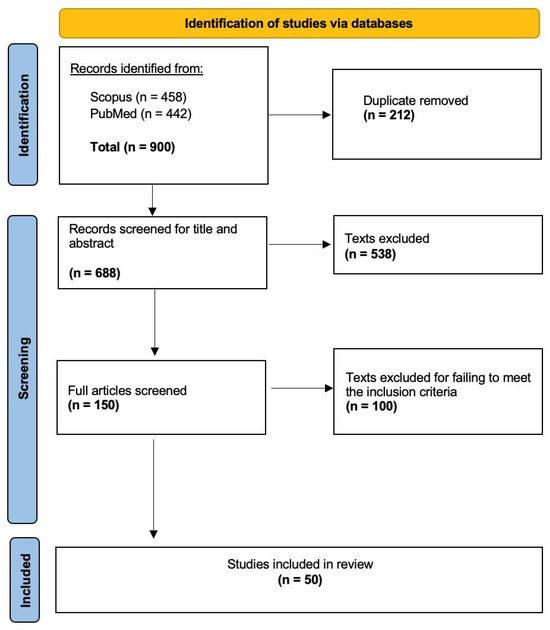

The initial database searches yielded 900 articles. Following this, all duplicates were removed (n = 212), as seen in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. The remaining articles (n = 688) were screened based on their titles and abstracts to see if they met the inclusion criteria and if they included key words or sentences in the title or abstract derived from the concepts in Table 1. The remaining articles (n = 150) were included for full data extraction. Following a secondary review, the included articles were further refined to exclude all studies conducted outside of the post-primary setting. Any articles which were heavily focused on physical activity (PA), i.e., making up approximately more than half of the intervention, were also excluded. The remaining articles (n = 50) were used to populate Table 2. Using quantitative content analysis, five key themes or categories were observed within these articles, and they were grouped accordingly.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram illustrating the study selection process [47].

3.1. Study Characteristics

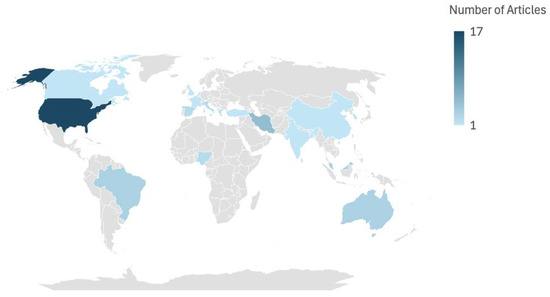

This scoping review highlights the extent to which interventions targeting adolescent dietary behaviours are being implemented globally, with studies spanning six continents, as shown in Figure 2. The largest proportion of research was conducted in North America (n = 18), likely reflecting the region’s strong focus on addressing DRDs, given the fact that NCDs are the leading cause of mortality in North America [106]. However, this geographic concentration may limit the generalisability of the findings to other educational systems, particularly those in low- and middle-income countries, where curricular structures, health priorities, and resource availability may differ significantly. The remaining studies were carried out in Asia (n = 15), Europe (n = 9), South America (n = 3), Oceania (n = 3), and Africa (n = 2).

Figure 2.

Heat map of publications by region (n = 50).

The duration of the included studies exhibited considerable variability, reflecting the diverse methodological approaches employed to evaluate each intervention, respectively. Intervention lengths ranged from as brief as 1 h to as extensive as 4 years, allowing for the assessment of both short and long-term outcomes. More than half of studies (n = 29) fell within a duration of 3 months to 1 year, striking a balance between practical implementation and the opportunity to observe meaningful behavioural changes. Notably, three studies did not specify a duration [79,94,97], while one study evaluated a previously completed intervention; therefore, the study duration was inconsequential [91].

3.2. Knowledge and/or Behaviour-Focused Interventions

Interventions which had a focus on knowledge and behavioural changes formed a significant portion of the reviewed literature, with studies frequently employing structured nutrition and health education sessions aimed at fostering healthier eating habits among adolescents (n = 15). These interventions frequently relied on established behavioural theories, including the social cognitive theory, transtheoretical model, and health belief model, to guide programme development and implementation [58,76,85,86,88,100]. Theoretical underpinnings enabled a focus on elements such as knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy, goal setting, and behaviour modification. Sessions were typically classroom-based and tailored to the age group, aiming to make nutrition concepts accessible and relevant to students [70,84]. A key advantage of education-based interventions is their ability to be incorporated into existing school curricula, making them logistically feasible and cost-effective [76]. The content covered ranged from basic nutritional knowledge such as understanding macronutrients and portion sizes to practical applications, such as meal planning and label reading [17,74,96,101]. The duration of these interventions varied from a few weeks to several months, with more extended programs often showing greater impact [63,70,72,74] with the exception of one study (Westfall et al., 2020 [74]).

However, challenges were noted, including varying levels of student engagement and retention of information. Some studies highlighted the importance of interactive and participatory elements, such as discussions, group activities, and hands-on demonstrations, to enhance the learning experience [17,70]. Additionally, studies emphasised the need for culturally appropriate content to address the diverse dietary habits and preferences of adolescents around the world [17,63].

3.3. Interventions Focused on Diet-Related Diseases

A number of studies (n = 14) employed interventions aimed at preventing or managing DRDs, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions. These programmes emphasised the link between dietary behaviours and health outcomes, often incorporating specific dietary recommendations tailored to the disease in focus [89]. DRD-targeting interventions generally adopted a two-pronged approach: providing foundational knowledge about the disease and equipping participants with actionable strategies to manage or mitigate risk [69,75,89,100]. Several interventions also integrated components on physical activity and stress management, recognising the multifaceted nature of DRDs [75,78,90]. The educational delivery methods varied, with some relying on traditional didactic approaches, while others used multimedia resources, visual aids, and interactive workshops to engage participants.

Challenges associated with DRD-focused education, including the potential for stigmatisation, particularly among overweight or obese adolescents, were discussed by Fernandez-Jimenez et al. [78]. Researchers, including Schapiro et al. [66] and Selamat [69], emphasised the importance of a non-judgmental and supportive approach to foster inclusivity and engagement. Another critical factor noted by Schapiro et al. [66] and Fernandez-Jimenez et al. [78] was the involvement of families, as dietary habits are often shaped within the household context. Programmes that included some level of parent workshops or take-home materials reported improved outcomes, suggesting that extending education beyond the classroom enhances effectiveness [93].

3.4. Interventions Involving Gamified/Digital or Interactive Learning

The use of gamified or interactive learning tools to educate adolescents about healthy eating was another key theme explored within some articles (n = 6). These interventions employed innovative methods, such as educational games [60], digital simulations [103], and interactive booklets [77], to increase engagement and improve learning outcomes. The gamified approach capitalised on adolescents’ preference for interactive and technology-based activities, making it particularly appealing for the post-primary cohort [60,103]. Some games and simulations incorporated scenarios requiring participants to make dietary decisions, providing immediate feedback on their choices [60,103]. For instance, some programs used computer-based tools that allowed students to simulate meal planning or navigate virtual grocery stores, reinforcing concepts such as balanced diets and budget-friendly shopping [60]. Other interventions involved more hands-on activities, such as interactive food challenges or organising a cooking show [59], which encouraged skill-building alongside knowledge acquisition. The use of rewards and challenges within these tools helped sustain motivation and participation, while the interactive nature facilitated active learning [103]. Shen et al. [73] discussed the use of a smartphone app which tracked students’ self-reported biometrics and issued tailored feedback to them. Studies frequently highlighted the role of enjoyment and fun in enhancing the effectiveness of these programs, as adolescents were more likely to remain engaged and internalise lessons when the learning process was entertaining [59,103]. The limitations of gamified approaches included the potential for unequal access to technology and the risk of oversimplifying complex nutritional concepts [99]. Additionally, the novelty of the approach often posed challenges in aligning the games’ content with standardised curricula.

3.5. Involvement of External or Peer Facilitators

The use of some form of external facilitation to promote healthier eating behaviours among adolescents was observed in multiple studies (n = 7). Partida et al. [87] and Slawson et al. [102] noted the role of healthcare professionals, such as dietitians or university students, in delivering these interventions, adding a layer of credibility and expertise. Saez et al. [82] researched peer-led interventions, which often involved older students or trained adolescent leaders conducting workshops, cooking demonstrations, or discussion groups. The relatable nature of peer educators was found to enhance engagement and credibility, as participants were more likely to trust and emulate individuals close to their age [97,98]. This type of intervention emphasised the social and cultural dimensions of eating, with activities designed to reflect the dietary practices and preferences of the target population. Challenges in implementing these interventions were identified by Saez et al. [82] and included logistical issues, such as training peer educators and coordinating with community stakeholders. Additionally, as Heo et al. [98] outlined, maintaining consistency and quality across diverse settings posed significant hurdles. Nonetheless, the social aspects of these programs, as noted by Huitink et al. [68], often led to improved attitudes towards healthy eating and increased confidence in making healthier food choices.

3.6. Adjustments to the School Food Environment

A number of studies utilised adjustments to the school’s food environment (n = 8) in order to improve dietary behaviours among students. These interventions involved structural [65] and policy [67] modifications within schools to create environments that facilitated healthier food choices. Common strategies included the introduction of healthy vending machines [71], the installation of water stations [65], and adjustments to cafeteria offerings, such as featuring prominently displayed fruits and vegetables or reducing the availability of sugary snacks [79]. Some programmes also incorporated promotional campaigns, using posters, announcements, or student ambassadors to increase awareness and encourage participation [91,94]. The rationale for these interventions lies in the substantial amount of time adolescents spend in school, making it a critical setting for influencing dietary behaviours. By modifying the “choice architecture” of the school food environment, these interventions aimed to make healthier options more accessible and appealing [79]. Studies emphasised the importance of visibility and convenience, noting that small changes, such as placing water bottles at eye level, significantly influenced students’ selections [79]. As outlined by Askelson et al. [81], barriers to implementation included resistance from stakeholders, such as cafeteria staff or school administrators, particularly when interventions impacted revenue from less healthy but popular options. Additionally, interventions were often limited by budget constraints and there was a need for external funding [67]. Despite these challenges, school-environment changes were effective in shifting consumption patterns, particularly when combined with educational components [65,71,81].

4. Discussion

This paper aimed to map the literature relevant to school-based food and NE programmes aimed at adolescents and in particular, those programmes focused on altering dietary behaviours in this demographic.

4.1. Knowledge- and/or Behaviour-Focused Interventions

Numerous interventions (n = 15) focused on improving general knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours relating to healthy eating, without targeting a specific DRD. Instead, they prioritised providing the participating students with a strong food literacy foundation, along with the skills needed to make educated choices regarding their diet. They often taught participants important knowledge about macronutrients, portion sizes, and the advantages of a balanced diet, all of which are pertinent to creating a healthy lifestyle. In addition to this, many interventions incorporated practical components, such as cooking demonstrations, meal planning exercises, and food label reading activities, to help participants apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios. Embedding these programs into school curricula ensured accessibility and allowed for consistent delivery, while tailoring content to the developmental stage of participants made lessons more engaging and relevant. Despite these strengths, some studies highlighted challenges, including varying levels of student engagement and retention, as well as the need for culturally tailored materials to address diverse dietary habits and preferences. While foundational knowledge is essential, it may not translate into meaningful behavioural change without deeper structural or socio-environmental support [107]. Additionally, the general focus on health education limited the ability to measure direct impacts on specific DRDs, limiting its applicability for high-risk populations. While these broad interventions lay the groundwork for healthier populations, combining them with targeted programs for specific conditions could maximise their impact. However, it is important to note that such programmes, particularly those embedded into curricula with hands-on components such as cooking or label-reading, may incur significant staffing, training, and material costs. Future planning should consider scalable models and cost–benefit analyses to support broader implementation in resource-limited schools.

4.2. Interventions Focused on Diet-Related Diseases

When left unmanaged, DRDs, such as obesity and diabetes, significantly shorten life expectancy [61]. DRDs demand long-term care, straining healthcare budgets and diverting resources from areas such as infectious diseases, maternal health, and prevention. A number of studies (n = 14) offered valuable information about the effectiveness of interventions aimed at DRDs, with the majority placing a critical focus on obesity (n = 10). One justification for this priority may be due to the high prevalence of overweight and obesity within the post-primary cohort of children globally. Furthermore, more than half of these studies relating to obesity (n = 6) were conducted in the USA, which could indicate an attempt to curb their increasingly high rates of obesity in both the adolescent and adult population [66,80,95,98,104,105]. All studies (n = 11) reported being successful to some extent in achieving their desired targets and goals. Many studies utilised anthropometric measurements such as BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio to track quantifiable data over the course of the interventions (n = 7). The use of clear and standardised anthropometric measures positively contributes to evidence-based decision making when analysing the effectiveness of the intervention. However, as stated, a large portion of these studies were conducted in the USA, which may hinder the generalisability of such interventions on a large scale, as contexts may vary across populations. For instance, interventions development in high-income contexts may not account for cultural, socioeconomic, or structural barriers in lower-resource settings. Furthermore, there is potential that publication bias may have led to the absence of similar studies that were unsuccessful or did not receive desired results. Although clinical outcomes such as BMI or waist circumference provide compelling evidence, these assessments require trained personnel and equipment, which can increase implementation costs. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of such interventions will be essential to guide sustainable investment by health and education sectors.

4.3. Interventions Involving Gamified/Digital or Interactive Learning

The use of gamified or interactive learning interventions is a novel pedagogical approach to improving dietary behaviours among adolescents. Within this review, studies offered a combination of positive outcomes, as well as notable limitations. Numerous studies demonstrated improvements in knowledge comprehension, such as enhanced quiz performance [77] and increased awareness of nutrition and food systems [60,99], which could suggest that this is an effective method of engaging students in learning complex concepts. However, the limited impact on behavioural change in some studies, such as the inability of one intervention to significantly shift parental perceptions of students’ nutritional status [73] or to promote healthier behaviours despite being engaging [59], underscores the gap between knowledge gains and sustained practical outcomes. The novelty of the gaming experience could be enough to boost short-term extrinsic motivation, yet it may fail to impart lasting internalised behaviour. The impact of the studies varied considerably, largely due to the differences in study designs. For example, one study found significant dietary changes, including higher intake of white meat, eggs, and legumes, along with a reduction in sugary snacks [103]. In contrast, other studies concentrated mainly on short-term improvements in knowledge and understanding, with limited evidence supporting sustained behavioural change [99]. This suggests that engagement alone may be insufficient for sustained behavioural change without complementary strategies such as the intervention design, the target demographic, and cultural relevance. Despite encouraging short-term gains in knowledge and dietary habits, the lack of extended follow-up in many studies limits the opportunity to assess the long-term sustainability and real-world impact of gamified interventions. Moreover, while digital tools and games can increase engagement, development and technology access costs may present barriers to equity and scalability, particularly in under-resourced regions. Future studies should explore the balance between initial investment and long-term educational return.

4.4. Involvement of External or Peer Facilitators

By using peers of an interventions’ target population, some studies were able to successfully increase engagement and participation levels among students [82,97,98]. Through fostering relatability and more approachable social support, students develop deeper understanding and are more motivated to adopt healthier eating behaviours. In order to improve their general relatability and approachability, two studies emphasised the use of peer facilitators who are chosen based on their strong leadership qualities or their comparable socioeconomic position to the students participating in the intervention [82]. However, peer relatability is not guaranteed; therefore, it is crucial to take cultural and social variables into account when choosing peer leaders to make sure they can, to the best of their ability, inspire and connect with the learners involved. However, youth peers do invite the possibility of spreading misinformation if improperly informed, as well as the risk of peer pressure or a power dynamic in some settings.

Other studies benefited from the inclusion of external facilitators, such as college students, dietitians, or nutritionists, to help provide guidance and specialised knowledge to peer facilitators through lessons on nutrition, physical activity, and self-efficacy. The expertise that they provide can further contribute to the effectiveness of an intervention by improving the participants’ knowledge in specific areas, such as the relationship between protein intake and exercise [68,87,102]. Although external facilitators offer experience, their recruitment is resource-intensive, which might restrict intervention scalability, particularly in underfunded education settings. In order to ensure that specialised knowledge is presented in an approachable and interesting way, the most successful interventions integrate the advantages of peer-led elements and external facilitators. However, some of the major limitations of these studies included their reliance on self-reported data in the form of post-study surveys, which may introduce bias. Another limitation would be the concept that the effectiveness of peer-led initiatives is directly linked to the learner’s individual situation, which can vary across different contexts and demographics. Customisability seems necessary to address socio-cultural variation; however, this introduces further challenges, such as the standardisation of interventions. Additionally, the reliance on either peer or external facilitators can significantly affect intervention costs and feasibility. While peer-led approaches may offer a low-cost alternative, they require robust training frameworks. In contrast, external facilitators enhance quality but increase programme costs. Careful consideration of these trade-offs is necessary when designing scalable models.

4.5. Adjustments to the School Food Environment

A number of studies (n = 8) facilitated interventions that mainly focused on or had elements involving adjustments to the school’s food environment. Despite varied approaches, all of these aimed to reshape the school food environment to encourage healthier behaviours, yet the consistency and depth of implementation varied greatly. Rearranging food placement to make healthier options easier to choose showed potential, but its impact was limited by mixed messages and a lack of readily available healthy choices [79]. The cause of this shortfall is unclear, but it could be due to budget, supply chain issues, or school policies which limited the healthy food options made available. Furthermore, some students found it difficult to prioritise the available healthy foods when there were still unhealthy options to choose from [79]. Other studies took a more compressive approach and included adjustments to the schools’ food environment, such as healthier canteen menu options, alongside educational learning opportunities [91,92,94]. The results of the initiatives indicated improvements in health metrics such as cholesterol, blood pressure, and obesity levels among participants, along with notable increases in healthy eating behaviours and nutritional understanding [91,92]. Another study took an approach that focused on improving the canteen atmosphere and fostering better interactions with staff, alongside increasing the availability of dairy, vegetables, and fruits [81]. This consequently lead the majority of participating schools to achieve their goals of increased healthy food consumption. An intervention targeting sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in disadvantaged Australian schools [67] achieved only modest reductions, underscoring the difficulty of driving behavioural change in such contexts. In contrast, the “Thirsty? Choose Water!” campaign effectively reduced sugary drink intake and boosted water consumption and the use of reusable water bottles, through the provision of chilled water stations and targeted education [65]. One explanation for the effectiveness of these two beverage-focused studies, could be the duration, with the more successful one taking place over the course of one year, compared to 6 months. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of school-based interventions while emphasising the need for well-funded, multifaceted strategies and extended durations to ensure lasting impact and sustained behavioural change. However, environmental changes, such as menu modifications or infrastructure improvements (e.g., chilled water stations) can carry substantial upfront and maintenance costs. Without adequate budgeting and long-term funding models, such changes may not be sustainable. Policymakers should prioritise interventions with demonstrated cost-effectiveness and feasibility in varying economic contexts.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

A predominant issue across many studies was the absence of long-term follow-up, limiting understanding of whether observed behavioural changes were sustained after the intervention period concluded. Furthermore, a heavy reliance on self-reported data, particularly in peer-led and gamified interventions, raises concerns around accuracy due to recall bias and social desirability, possibly leading to an exaggeration of effectiveness. Future research should consider integrating objective measures where possible, such as wearable devices or teacher-reported behavioural logs, to triangulate data and improve validity. Interventions involving clinical metrics (e.g., cholesterol or BMI) faced additional challenges, as ethical approval and clinical oversight are difficult to secure in school settings unless qualified health professionals are included as part of the intervention team. This raises questions around feasibility and role clarity, especially in under-resourced schools, where there may be tension or confusion around health-related responsibilities. To address this, partnerships with community health services or mobile clinics could offer a viable alternative for data collection and oversight without overburdening school staff. Moreover, many interventions were implemented in specific cultural or socioeconomic contexts, most notably in high-income settings such as the U.S., which limits generalisability to other regions. Although the studies spanned diverse cultural contexts, few reported how interventions were meaningfully adapted to fit local norms and practices. Where cultural tailoring was mentioned, it was often limited to translation or familiar food examples. This highlights a need for more intentional and transparent cultural adaptation in future nutrition education research. Adaptable intervention models and inclusive study designs that involve co-creation with local stakeholders can help enhance cultural relevance and scalability across diverse settings. Future studies should focus on flexible, practical approaches that take into account different school settings and real-world challenges, while also being mindful of ethics and available resources. It is acknowledged that long-term research in school settings is often limited by ethical considerations, the complexity of controlling for confounding variables, time constraints, and potential crossover between educational and clinical responsibilities. Further research should also explore the long-term impacts of nutrition education, including potential effects on body weight and cardio-metabolic outcomes, particularly during key developmental stages such as pre-puberty. Equally important is the integration of economic evaluations in future research to assess cost-effectiveness and inform policy-level decision-making. Clear reporting of resource use, staffing requirements, and delivery costs will support the development of scalable and sustainable programmes.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review aimed to map the current literature relating to the efficacy of post-primary NE interventions and their potential to halt the rising concern of DRDs. The findings partially support this aim; however, the strength of the conclusions must be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of study designs, intervention components, and outcome measures, as well as several methodological limitations present across the included studies. While many interventions led to improvements in nutritional knowledge and short-term behaviour, fewer demonstrated sustained change or consistent clinical outcomes. This suggests that the success of such programmes depends heavily on factors such as intervention design, duration, cultural relevance, and available resources. Accordingly, broader generalisations about intervention effectiveness should be avoided without further high-quality evidence. Future work would benefit from the inclusion of longitudinal studies alongside culturally tailored interventions to evaluate the impact overtime across diverse school settings. In light of these findings, it is recommended that policymakers prioritise sustained, theory-based NE interventions that are contextually adaptable and supported by adequate resources. Schools should integrate NE more holistically into the curriculum, ensuring the programmes are age-appropriate, culturally relevant, and designed with input from educators, health professionals, and families. Intervention designers are encouraged to align future programmes with behavioural change theories and include mechanisms for long-term follow-up to assess lasting impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.; formal analysis, K.M., L.M. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M., L.M. and A.M.; visualization, K.M.; supervision; L.M. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DRD | Diet-related disease |

| NE | Nutritional education |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Review and Meta-Analyses |

| SCT | Social cognitive theory |

| TPB | Theory of planned behaviour |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3–4 |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 4–5 |

| Data charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5–6 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 6–15 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 6–18 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 6–18 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 18–21 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 21 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 21 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 21 |

* Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and Web sites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley (6) and Levac and colleagues (7) and the JBI guidance (4, 5) refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of "risk of bias" (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document).

References

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewen, O.K.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Ohinmmaa, A.; Veugelers, P.J. Economic Burden of Not Complying with Canadian Food Recommendations in 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, L.; Opie, R.S. A nutrition strategy to reduce the burden of diet related disease: Access to dietician services must complement population health approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; Riddle, M.C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Hu, F.B. Red and Processed Meats and Health Risks: How Strong Is the Evidence? Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirullah, M.N.; Llc, A.P. Fast Food Addiction: A Major Public Health Issue. Nutr. Food Process. 2020, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.V.; Roux, A.V.D.; Nettleton, J.A.; Jacobs, D.R.; Franco, M. Fast-food consumption, diet quality, and neighborhood exposure to fast food: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, W. How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2221–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropper, S.S. The Role of Nutrition in Chronic Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Caballero, B.; Cousins, R.J.; Tucker, K.L. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease; Jones Bartlett Learn: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://books.google.ie/books?id=9zZvEAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/349086/WHO-EURO-2021-4007-43766-61591-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Jih, J.; Stijacic-Cenzer, I.; Seligman, H.K.; Boscardin, W.J.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ritchie, C.S. Chronic disease burden predicts food insecurity among older adults. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candari, C.J.; Cylus, J.; Nolte, E.; Policies, E.O.O.H.S.A.; De L’europe, O.M.D.L.S.B.R. Assessing the Economic Costs of Unhealthy Diets and Low Physical Activity: An Evidence Review and Proposed Framework; WHO Regional Office For Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28787114/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ahmed, K.R.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Khan, A. Efficacy of a school-based education intervention on the consumption of fruits, vegetables and carbonated soft drinks among adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 3112–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.; Lynch, K.T.; Kass, A.E.; Burrows, A.; Williams, J.; Wilfley, D.E.; Taylor, C.B. Healthy weight regulation and eating disorder prevention in high school students: A universal and targeted web-based intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahnazi, H.; Koon, P.B.; Talib, R.A.; Lubis, S.H.; Dashti, M.G.; Khatooni, E.; Esfahani, N.B. Can the BASNEF Model Help to Develop Self-Administered Healthy Behavior in Iranian Youth? Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e23847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 1: Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M. Theory of Planned Behavior. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S.A.; Frongillo, E.A.; Black, M.M.; Dong, Y.; Fall, C.; Lampl, M.; Liese, A.D.; Naguib, M.; Prentice, A.; Rochat, T.; et al. Nutrition in adolescent growth and development. Lancet 2022, 399, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.D.; Zuelch, M.L.; Dimitratos, S.M.; Scherr, R.E. Adolescent Obesity: Diet Quality, Psychosocial Health, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Nutrients 2019, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, L.; Ishida, A. Effect of Mid-Adolescent Dietary Practices on Eating Behaviors and Attitudes in Adulthood. Nutrients 2023, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Larson, N.I.; Christoph, M.J.; Sherwood, N.E. Eating, Activity, and Weight-related Problems From Adolescence to Adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizia, S.; Felińczak, A.; Włodarek, D.; Syrkiewicz-Świtała, M. Evaluation of Eating Habits and Their Impact on Health among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ammari, A.; El Kazdouh, H.; Bouftini, S.; El Fakir, S.; El Achhab, Y. Social-ecological influences on unhealthy dietary behaviours among Moroccan adolescents: A mixed-methods study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghirad, B.; Duhaney, T.; Motaghipisheh, S.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Johnston, B.C. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, H.; König, L.M.; Tăut, D.; Ollila, H.; Băban, A.; Absetz, P.; Schupp, H.; Renner, B. Exploring the Association between Television Advertising of Healthy and Unhealthy Foods, Self-Control, and Food Intake in Three European Countries. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 7, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Ng, S.; Adams, J.; Allemandi, L.; Bahena-Bahena-Espina, L.; Barquera, S.; Boyland, E.; Calleja, P.; Carmona-Garcés, I.C.; et al. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, R.; Harrold, J.; Child, S.; Halford, J.; Boyland, E. The Health Halo Trend in UK Television Food Advertising Viewed by Children: The Rise of Implicit and Explicit Health Messaging in the Promotion of Unhealthy Foods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziso, D.; Chun, O.K.; Puglisi, M.J. Increasing Access to Healthy Foods through Improving Food Environment: A Review of Mixed Methods Intervention Studies with Residents of Low-Income Communities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facina, V.B.; Fonseca, R.d.R.; da Conceição-Machado, M.E.P.; Ribeiro-Silva, R.d.C.; dos Santos, S.M.C.; de Santana, M.L.P. Association between Socioeconomic Factors, Food Insecurity, and Dietary Patterns of Adolescents: A Latent Class Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B.K.; Hong, Y.-Y. Mere experience of low subjective socioeconomic status stimulates appetite food intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.Z.H.; Lwin, M.O.; Ho, S.S. The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslin, A.M.; McNulty, B. Adolescent nutrition and health: Characteristics, risk factors and opportunities of an overlooked life stage. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Mansouri, T.H.; Gregory, A.M.; Barich, R.A.; Hatzinger, L.A.; Leone, L.A.; Temple, J.L. An Ecological Perspective of Food Choice and Eating Autonomy Among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 654139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, R.; Chapman, G.E.; Beagan, B.L. Autonomy and control: The co-construction of adolescent food choice. Appetite 2008, 50, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winpenny, E.M.; Penney, T.L.; Corder, K.; White, M.; Van Sluijs, E.M. Change in diet in the period from adolescence to early adulthood: A systematic scoping review of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Paya, N.; Ensenyat, A.; Castro-Viñuales, I.; Real, J.; Sinfreu-Bergués, X.; Zapata, A.; Mur, J.M.; Galindo-Ortego, G.; Solé-Mir, E.; Teixido, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a Multi-Component Intervention for Overweight and Obese Children (Nereu Program): A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, S.; Alperin, H. Health Education in the 21st Century: A Skills-based Approach. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2019, 90, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; Renner, B.; Clarys, P.; Lien, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Deliens, T. Understanding Eating Behavior during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: A Literature Review and Perspective on Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, M.E.; Pederiva, C.; Viggiano, C.; De Santis, R.; Banderali, G.; Biasucci, G. Nutritional Approach to Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease in Childhood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Mancino, J.; Burke, L.E.; Glanz, K. Current Theoretical Bases for Nutrition Intervention and Their Uses. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, J.E.; Brennan, S.E.; Ryan, R.E.; Thomson, H.J.; Johnston, R.V.; Thomas, J. Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurc, J.; Laaksonen, C. Effectiveness of Health Promotion Interventions in Primary Schools—A Mixed Methods Literature Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-Soler, R.; Alférez-Pastor, M.; Torres, F.L.; Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Navarro, N. A Systematic Review of Healthy Nutrition Intervention Programs in Kindergarten and Primary Education. Nutrients 2023, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, C.M.; Ferreira, J.C. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Studies: Definitions and Why They Matter. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2018, 44, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus. Scopus Content; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/content (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- PubMed. PubMed Overview; PubMed: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/about/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, C.R.; Izadi, S.; Fowler, S.; Green, P.; Suls, J.; Colditz, G.A. The Value of a Second Reviewer for Study Selection in Systematic Reviews. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haroni, H.; Farid, N.D.N.; Azanan, M.S.; Alhalaiqa, F. Effectiveness of education intervention, with regards to physical activity level and a healthy diet, among Middle Eastern adolescents in Malaysia: A study protocol for a randomized control trial, based on a health belief model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0289937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresi, G.; Giampaolo, M.; Chiavegatti, B.; Marta, E. Process Evaluation of Food Game: A Gamified School-Based Intervention to Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Dietary Choices. J. Prev. 2023, 44, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Barwood, D.; Devine, A.; Boston, J.; Smith, S.; Masek, M. Rethinking Adolescent School Nutrition Education Through a Food Systems Lens. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, J.Z.; Kumar, P.; Kulkarni, M.M.; Kamath, A. Outcome of structured health education intervention for obesity-risk reduction among junior high school students: Stratified cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) in South India. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, M.; Hassandra, M.; Krommidas, C.; Kolovelonis, A.; Bouglas, V.; Theodorakis, Y. Implementation and Evaluation of a School-Based Educational Program Targeting Healthy Diet and Exercise (DIEX) for Greek High School Students. Sports 2022, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, L.; Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.J. Effect Evaluation of Sahtak bi Sahnak, a Lebanese Secondary School-Based Nutrition Intervention: A Cluster Randomised Trial. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 824020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, J.; Ward, S.; LeBlanc, C.P. An elective high school cooking course improves students’ cooking and food skills: A quasi-experimental study. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowland-Ella, J.; Batchelor, S.; David, M.; Lewis, P.; Kajons, N. The outcomes of Thirsty? Choose Water! Determining the effects of a behavioural and an environmental intervention on water and sugar sweetened beverage consumption in adolescents: A randomised controlled trial. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 34, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, N.A.; Green, E.K.; Kaller, S.; Brindis, C.D.; Rodriguez, A.; Alkebulan-Abakah, M.; Chen, J.-L. Impact on Healthy Behaviors of Group Obesity Management Visits in Middle School Health Centers. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, J.Y.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.L.; Janssen, L.M.; Reilly, K.; Nathan, N.; Sutherland, R. A trial of a six-month sugar-sweetened beverage intervention in secondary schools from a socio-economically disadvantaged region in Australia. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2021, 45, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitink, M.; Poelman, M.P.; Seidell, J.C.; Dijkstra, S.C. The Healthy Supermarket Coach: Effects of a Nutrition Peer-Education Intervention in Dutch Supermarkets Involving Adolescents With a Lower Education Level. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 48, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, R.; Raib, J.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Zulkafly, N.; Ismail, A.N.; Mohamad, W.N.A.W.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Zain, F.M.; Ishak, Z.; Yahya, A.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake among overweight and obese school children: A cluster randomised control trial. Malays. J. Nutr. 2021, 27, 067–079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orta, L.; Yepez, E.; Nguyen, N.; Rico, R.; Trieu, S.L. Bridging the GAP: Leveraging Partnerships to Bring Quality Nutrition Education to the Gardening Apprenticeship Program. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 22, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.D.; Gorodnichenko, A.; Fradkin, A.; Weiss, B. The Impact of a Short-term Intervention on Adolescent Eating Habits and Nutritional Knowledge. Deleted J. 2021, 23, 720–724. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeanu, V.N.; Edeh, C.G.; Ani, P.N. Evidence-based strategy for prevention of hidden hunger among adolescents in a suburb of Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.-Y.; Lo, Y.-T.C.; Chilinda, Z.B.; Huang, Y.-C. After-school nutrition education programme improves eating behaviour in economically disadvantaged adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westfall, M.; Roth, S.E.; Gill, M.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Rice, L.N.; Crespi, C.M.; Prelip, M.L. Exploring the Relationship Between MyPlate Knowledge, Perceived Diet Quality, and Healthy Eating Behaviors Among Adolescents. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeihooni, A.K.; Heidari, M.S.; Harsini, P.A.; Azizinia, S. Application of PRECEDE model in education of nutrition and physical activities in obesity and overweight female high school students. Obes. Med. 2019, 14, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwa, M.; Haque, A.; Khalequzzaman, M.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.R.; Choudhury, S.R. Towards reducing behavioral risk factors of non-communicable diseases among adolescents: Protocol for a school-based health education program in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.M.; Zangerolamo, L.; Rosa, L.R.O.; Branco, R.C.S.; Carneiro, E.M.; Barbosa-Sampaio, H.C. Impact of a playful booklet about diabetes and obesity on high school students in Campinas, Brazil. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2019, 43, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Santos-Beneit, G.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Bodega, P.; de Miguel, M.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Rodríguez, C.; Carral, V.; Orrit, X.; Haro, D.; et al. Rationale and design of the school-based SI! Program to face obesity and promote health among Spanish adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am. Heart J. 2019, 215, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, L.; Bradley, J.; Adamson, A.J.; Spence, S. The ‘Voice’ of Key Stakeholders in a School Food and Drink Intervention in Two Secondary Schools in NE England: Findings from a Feasibility Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, L.; Speiser, P.W.; Accacha, S.; Altshuler, L.; Fennoy, I.; Lowell, B.; Rapaport, R.; Rosenfeld, W.; Shelov, S.P.; Ten, S.; et al. Demographics and anthropometrics impact benefits of health intervention: Data from the Reduce Obesity and Diabetes Project. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2019, 5, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askelson, N.M.; Brady, P.; Ryan, G.; Meier, C.; Ortiz, C.; Scheidel, C.; Delger, P. Actively Involving Middle School Students in the Implementation of a Pilot of a Behavioral Economics–Based Lunchroom Intervention in Rural Schools. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 20, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, L.; Legrand, K.; Alleyrat, C.; Ramisasoa, S.; Langlois, J.; Muller, L.; Omorou, A.Y.; De Lavenne, R.; Kivits, J.; Lecomte, E.; et al. Using facilitator–receiver peer dyads matched according to socioeconomic status to promote behaviour change in overweight adolescents: A feasibility study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, M.; Jimenez, C.C.; Lim, J.; Isasi, C.R.; Blank, A.E.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Fredericks, L.; Bouchard, M.; Faith, M.S.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Effective nationwide school-based participatory extramural program on adolescent body mass index, health knowledge and behaviors. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton-Lopez, M.M.; Manore, M.M.; Branscum, A.; Meng, Y.; Wong, S.S. Changes in Sport Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes/Beliefs and Behaviors Following a Two-Year Sport Nutrition Education and Life-Skills Intervention among High School Soccer Players. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Pirzadeh, A.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Mostafavi, F. The Effect of a Social Cognitive Theory-Based Intervention on Fast Food Consumption Among Students. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2018, 12, e10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, M.; Rahimi, A.; Zare-Farashbandi, F.; Naeini, A.A.; Hasanzadeh, A. The effect of nutrition education course on awareness of obese and overweight female 1st-year High School students of Isfahan based on transtheoretical model of behavioral change. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida, S.; Marshall, A.; Henry, R.; Townsend, J.; Toy, A. Attitudes toward Nutrition and Dietary Habits and Effectiveness of Nutrition Education in Active Adolescents in a Private School Setting: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, L.; Masoudi, R.; Lotfizadeh, M. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Nutritional Education based on Health Belief Model on Self-Esteem and BMI of Overweight and at Risk of Overweight Adolescent Girls. Int. J. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jeong, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Suk, S.-H. Stroke awareness in Korean high school students. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2017, 117, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, D.S.; Goulart, M.R.; Barbiero, S.M.; Sica, C.D.; Borges, R.; Moraes, D.W.; Pellanda, L.C. Healthy School, Happy School: Design and Protocol for a Randomized Clinical Trial Designed to Prevent Weight Gain in Children. Arq. Bras. de Cardiol. 2017, 108, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.; Krallman, R.; Jackson, E.A.; DuRussel-Weston, J.; Palma-Davis, L.; de Visser, R.; Eagle, T.; Eagle, K.A.; Kline-Rogers, E. Top 10 Lessons Learned from Project Healthy Schools. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 990.e1–990.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meseri, R.; Ergin, I.; Mermer, G.; Hassoy, H.; Yörük, S.; Çatalgöl, Ş. School based multifaceted nutrition intervention decreased obesity in a high school: An intervention study from Turkey. Prog. Nutr. 2017, 19, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacopoulou, F.; Landis, G.; Rentoumis, A.; Tsitsika, A.; Efthymiou, V. Mediterranean diet decreases adolescent waist circumference. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 47, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamerson, T.; Sylvester, R.; Jiang, Q.; Corriveau, N.; DuRussel-Weston, J.; Kline-Rogers, E.; Jackson, E.A.; Eagle, K.A. Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Health Behaviors Between Black and Non-Black Students Participating in a School-Based Health Promotion Program. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 31, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorick, S.; Fang, X.; Crawford, Y. The MATCH Program: Long-Term Obesity Prevention Through a Middle School Based Intervention. Child. Obes. 2016, 12, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.M.F.d.C.; Lima, K.C.; Alves, M.D.S.C.F. Promoting public health through nutrition labeling—A study in Brazil. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, S.I.Z.S.; Chin, Y.S.; Taib, M.N.M.; Shariff, Z.M. School-based intervention to prevent overweight and disordered eating in secondary school Malaysian adolescents: A study protocol. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.; Irvin, E.; Ostrovsky, N.; Isasi, C.; Blank, A.E.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Fredericks, L.; Yom, T.; Ginsberg, M.; Hayes, S.; et al. Behaviors and Knowledge of HealthCorps New York City High School Students: Nutrition, Mental Health, and Physical Activity. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsile, S.E.; Ogundele, B.O. Effect of game-enhanced nutrition education on knowledge, attitude and practice of healthy eating among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2016, 54, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.L.; Contento, I.R.; Koch, P.A. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum, ‘Choice, Control and Change’. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Joram, E.; Matvienko, O.; Woolf, S.; Knesting, K. Impact of an intuitive eating education program on high school students’ eating attitudes. Health Educ. 2015, 115, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawson, D.L.; Dalton, W.T.; Dula, T.M.; Southerland, J.; Wang, L.; Littleton, M.A.; Mozen, D.; Relyea, G.; Schetzina, K.; Lowe, E.F.; et al. College students as facilitators in reducing adolescent obesity disparity in Southern Appalachia: Team Up for Healthy Living. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 43, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, D.; Fraticelli, F.; Polcini, F.; Lato, R.; Pintaudi, B.; Nicolucci, A.; Fulcheri, M.; Mohn, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Di Vieste, G.; et al. Preventing Adolescents’ Diabesity: Design, Development, and First Evaluation of “Gustavo in Gnam’s Planet”. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweat, V.; Bruzzese, J.-M.; Fierman, A.; Mangone, A.; Siegel, C.; Laska, E.; Convit, A. Outcomes of The BODY Project: A Program to Halt Obesity and Its Medical Consequences in High School Students. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazorick, S.; Fang, X.; Hardison, G.T.; Crawford, Y. Improved Body Mass Index Measures Following a Middle School-Based Obesity Intervention—The MATCH Program. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. The Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in the Region of the Americas, 2000–2019; ENLACE Data Portal; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, T. Practice-ing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]