Examining the Efficacy of Post-Primary Nutritional Education Interventions as a Preventative Measure for Diet-Related Diseases: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Influencing Factors and Adolescent Dietary Habits

1.3. The Role of NE in Adolescence

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search and Information Sources

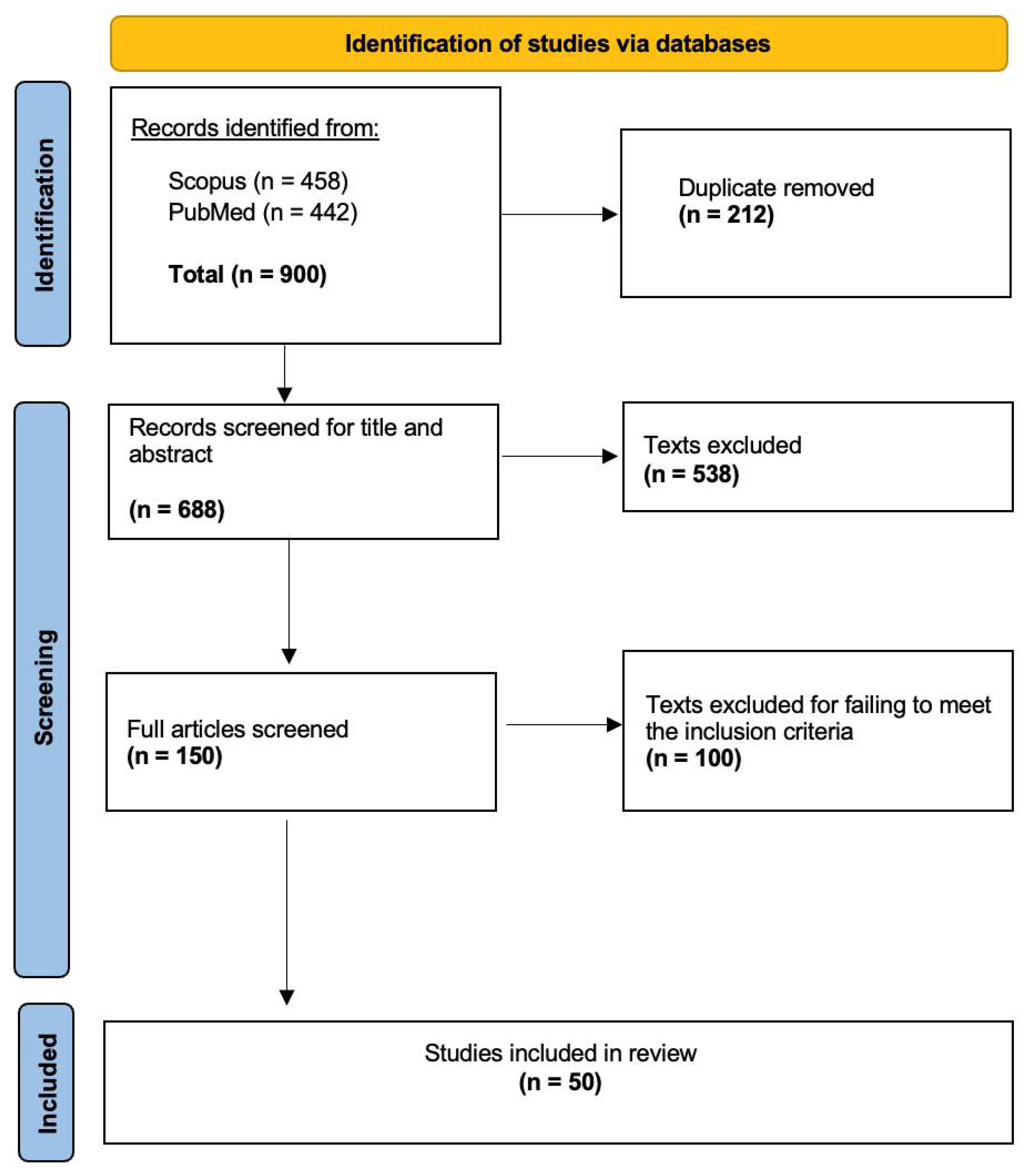

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.5. Data Charting Process and Data Items

3. Results

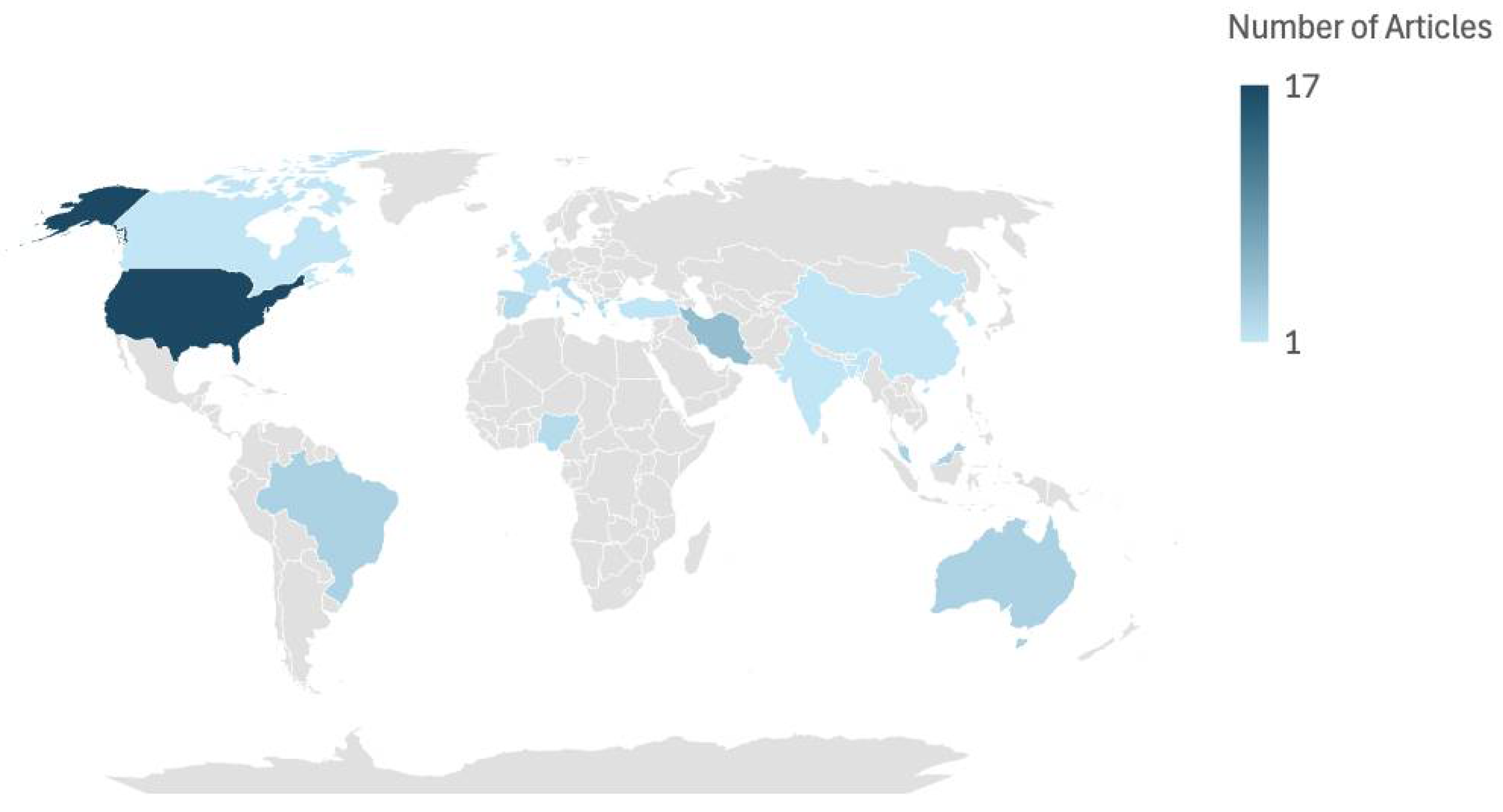

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Knowledge and/or Behaviour-Focused Interventions

3.3. Interventions Focused on Diet-Related Diseases

3.4. Interventions Involving Gamified/Digital or Interactive Learning

3.5. Involvement of External or Peer Facilitators

3.6. Adjustments to the School Food Environment

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge- and/or Behaviour-Focused Interventions

4.2. Interventions Focused on Diet-Related Diseases

4.3. Interventions Involving Gamified/Digital or Interactive Learning

4.4. Involvement of External or Peer Facilitators

4.5. Adjustments to the School Food Environment

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRD | Diet-related disease |

| NE | Nutritional education |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Review and Meta-Analyses |

| SCT | Social cognitive theory |

| TPB | Theory of planned behaviour |

Appendix A

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3–4 |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 4–5 |

| Data charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5–6 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 6–15 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 6–18 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 6–18 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 18–21 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 21 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 21 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 21 |

References

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewen, O.K.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Ohinmmaa, A.; Veugelers, P.J. Economic Burden of Not Complying with Canadian Food Recommendations in 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, L.; Opie, R.S. A nutrition strategy to reduce the burden of diet related disease: Access to dietician services must complement population health approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; Riddle, M.C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Hu, F.B. Red and Processed Meats and Health Risks: How Strong Is the Evidence? Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirullah, M.N.; Llc, A.P. Fast Food Addiction: A Major Public Health Issue. Nutr. Food Process. 2020, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.V.; Roux, A.V.D.; Nettleton, J.A.; Jacobs, D.R.; Franco, M. Fast-food consumption, diet quality, and neighborhood exposure to fast food: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, W. How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2221–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropper, S.S. The Role of Nutrition in Chronic Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Caballero, B.; Cousins, R.J.; Tucker, K.L. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease; Jones Bartlett Learn: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://books.google.ie/books?id=9zZvEAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/349086/WHO-EURO-2021-4007-43766-61591-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Jih, J.; Stijacic-Cenzer, I.; Seligman, H.K.; Boscardin, W.J.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ritchie, C.S. Chronic disease burden predicts food insecurity among older adults. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candari, C.J.; Cylus, J.; Nolte, E.; Policies, E.O.O.H.S.A.; De L’europe, O.M.D.L.S.B.R. Assessing the Economic Costs of Unhealthy Diets and Low Physical Activity: An Evidence Review and Proposed Framework; WHO Regional Office For Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28787114/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ahmed, K.R.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Khan, A. Efficacy of a school-based education intervention on the consumption of fruits, vegetables and carbonated soft drinks among adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 3112–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.; Lynch, K.T.; Kass, A.E.; Burrows, A.; Williams, J.; Wilfley, D.E.; Taylor, C.B. Healthy weight regulation and eating disorder prevention in high school students: A universal and targeted web-based intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahnazi, H.; Koon, P.B.; Talib, R.A.; Lubis, S.H.; Dashti, M.G.; Khatooni, E.; Esfahani, N.B. Can the BASNEF Model Help to Develop Self-Administered Healthy Behavior in Iranian Youth? Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e23847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 1: Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M. Theory of Planned Behavior. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S.A.; Frongillo, E.A.; Black, M.M.; Dong, Y.; Fall, C.; Lampl, M.; Liese, A.D.; Naguib, M.; Prentice, A.; Rochat, T.; et al. Nutrition in adolescent growth and development. Lancet 2022, 399, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.D.; Zuelch, M.L.; Dimitratos, S.M.; Scherr, R.E. Adolescent Obesity: Diet Quality, Psychosocial Health, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Nutrients 2019, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, L.; Ishida, A. Effect of Mid-Adolescent Dietary Practices on Eating Behaviors and Attitudes in Adulthood. Nutrients 2023, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Larson, N.I.; Christoph, M.J.; Sherwood, N.E. Eating, Activity, and Weight-related Problems From Adolescence to Adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizia, S.; Felińczak, A.; Włodarek, D.; Syrkiewicz-Świtała, M. Evaluation of Eating Habits and Their Impact on Health among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ammari, A.; El Kazdouh, H.; Bouftini, S.; El Fakir, S.; El Achhab, Y. Social-ecological influences on unhealthy dietary behaviours among Moroccan adolescents: A mixed-methods study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghirad, B.; Duhaney, T.; Motaghipisheh, S.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Johnston, B.C. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, H.; König, L.M.; Tăut, D.; Ollila, H.; Băban, A.; Absetz, P.; Schupp, H.; Renner, B. Exploring the Association between Television Advertising of Healthy and Unhealthy Foods, Self-Control, and Food Intake in Three European Countries. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 7, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Ng, S.; Adams, J.; Allemandi, L.; Bahena-Bahena-Espina, L.; Barquera, S.; Boyland, E.; Calleja, P.; Carmona-Garcés, I.C.; et al. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, R.; Harrold, J.; Child, S.; Halford, J.; Boyland, E. The Health Halo Trend in UK Television Food Advertising Viewed by Children: The Rise of Implicit and Explicit Health Messaging in the Promotion of Unhealthy Foods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziso, D.; Chun, O.K.; Puglisi, M.J. Increasing Access to Healthy Foods through Improving Food Environment: A Review of Mixed Methods Intervention Studies with Residents of Low-Income Communities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facina, V.B.; Fonseca, R.d.R.; da Conceição-Machado, M.E.P.; Ribeiro-Silva, R.d.C.; dos Santos, S.M.C.; de Santana, M.L.P. Association between Socioeconomic Factors, Food Insecurity, and Dietary Patterns of Adolescents: A Latent Class Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B.K.; Hong, Y.-Y. Mere experience of low subjective socioeconomic status stimulates appetite food intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.Z.H.; Lwin, M.O.; Ho, S.S. The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslin, A.M.; McNulty, B. Adolescent nutrition and health: Characteristics, risk factors and opportunities of an overlooked life stage. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Mansouri, T.H.; Gregory, A.M.; Barich, R.A.; Hatzinger, L.A.; Leone, L.A.; Temple, J.L. An Ecological Perspective of Food Choice and Eating Autonomy Among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 654139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, R.; Chapman, G.E.; Beagan, B.L. Autonomy and control: The co-construction of adolescent food choice. Appetite 2008, 50, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winpenny, E.M.; Penney, T.L.; Corder, K.; White, M.; Van Sluijs, E.M. Change in diet in the period from adolescence to early adulthood: A systematic scoping review of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Paya, N.; Ensenyat, A.; Castro-Viñuales, I.; Real, J.; Sinfreu-Bergués, X.; Zapata, A.; Mur, J.M.; Galindo-Ortego, G.; Solé-Mir, E.; Teixido, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a Multi-Component Intervention for Overweight and Obese Children (Nereu Program): A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, S.; Alperin, H. Health Education in the 21st Century: A Skills-based Approach. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2019, 90, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; Renner, B.; Clarys, P.; Lien, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Deliens, T. Understanding Eating Behavior during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: A Literature Review and Perspective on Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, M.E.; Pederiva, C.; Viggiano, C.; De Santis, R.; Banderali, G.; Biasucci, G. Nutritional Approach to Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease in Childhood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Mancino, J.; Burke, L.E.; Glanz, K. Current Theoretical Bases for Nutrition Intervention and Their Uses. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, J.E.; Brennan, S.E.; Ryan, R.E.; Thomson, H.J.; Johnston, R.V.; Thomas, J. Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurc, J.; Laaksonen, C. Effectiveness of Health Promotion Interventions in Primary Schools—A Mixed Methods Literature Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-Soler, R.; Alférez-Pastor, M.; Torres, F.L.; Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Navarro, N. A Systematic Review of Healthy Nutrition Intervention Programs in Kindergarten and Primary Education. Nutrients 2023, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, C.M.; Ferreira, J.C. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Studies: Definitions and Why They Matter. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2018, 44, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus. Scopus Content; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/content (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- PubMed. PubMed Overview; PubMed: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/about/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, C.R.; Izadi, S.; Fowler, S.; Green, P.; Suls, J.; Colditz, G.A. The Value of a Second Reviewer for Study Selection in Systematic Reviews. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haroni, H.; Farid, N.D.N.; Azanan, M.S.; Alhalaiqa, F. Effectiveness of education intervention, with regards to physical activity level and a healthy diet, among Middle Eastern adolescents in Malaysia: A study protocol for a randomized control trial, based on a health belief model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0289937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresi, G.; Giampaolo, M.; Chiavegatti, B.; Marta, E. Process Evaluation of Food Game: A Gamified School-Based Intervention to Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Dietary Choices. J. Prev. 2023, 44, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Barwood, D.; Devine, A.; Boston, J.; Smith, S.; Masek, M. Rethinking Adolescent School Nutrition Education Through a Food Systems Lens. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, J.Z.; Kumar, P.; Kulkarni, M.M.; Kamath, A. Outcome of structured health education intervention for obesity-risk reduction among junior high school students: Stratified cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) in South India. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, M.; Hassandra, M.; Krommidas, C.; Kolovelonis, A.; Bouglas, V.; Theodorakis, Y. Implementation and Evaluation of a School-Based Educational Program Targeting Healthy Diet and Exercise (DIEX) for Greek High School Students. Sports 2022, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, L.; Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.J. Effect Evaluation of Sahtak bi Sahnak, a Lebanese Secondary School-Based Nutrition Intervention: A Cluster Randomised Trial. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 824020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, J.; Ward, S.; LeBlanc, C.P. An elective high school cooking course improves students’ cooking and food skills: A quasi-experimental study. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowland-Ella, J.; Batchelor, S.; David, M.; Lewis, P.; Kajons, N. The outcomes of Thirsty? Choose Water! Determining the effects of a behavioural and an environmental intervention on water and sugar sweetened beverage consumption in adolescents: A randomised controlled trial. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 34, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, N.A.; Green, E.K.; Kaller, S.; Brindis, C.D.; Rodriguez, A.; Alkebulan-Abakah, M.; Chen, J.-L. Impact on Healthy Behaviors of Group Obesity Management Visits in Middle School Health Centers. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, J.Y.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.L.; Janssen, L.M.; Reilly, K.; Nathan, N.; Sutherland, R. A trial of a six-month sugar-sweetened beverage intervention in secondary schools from a socio-economically disadvantaged region in Australia. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2021, 45, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitink, M.; Poelman, M.P.; Seidell, J.C.; Dijkstra, S.C. The Healthy Supermarket Coach: Effects of a Nutrition Peer-Education Intervention in Dutch Supermarkets Involving Adolescents With a Lower Education Level. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 48, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, R.; Raib, J.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Zulkafly, N.; Ismail, A.N.; Mohamad, W.N.A.W.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Zain, F.M.; Ishak, Z.; Yahya, A.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake among overweight and obese school children: A cluster randomised control trial. Malays. J. Nutr. 2021, 27, 067–079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orta, L.; Yepez, E.; Nguyen, N.; Rico, R.; Trieu, S.L. Bridging the GAP: Leveraging Partnerships to Bring Quality Nutrition Education to the Gardening Apprenticeship Program. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 22, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.D.; Gorodnichenko, A.; Fradkin, A.; Weiss, B. The Impact of a Short-term Intervention on Adolescent Eating Habits and Nutritional Knowledge. Deleted J. 2021, 23, 720–724. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeanu, V.N.; Edeh, C.G.; Ani, P.N. Evidence-based strategy for prevention of hidden hunger among adolescents in a suburb of Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.-Y.; Lo, Y.-T.C.; Chilinda, Z.B.; Huang, Y.-C. After-school nutrition education programme improves eating behaviour in economically disadvantaged adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westfall, M.; Roth, S.E.; Gill, M.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Rice, L.N.; Crespi, C.M.; Prelip, M.L. Exploring the Relationship Between MyPlate Knowledge, Perceived Diet Quality, and Healthy Eating Behaviors Among Adolescents. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeihooni, A.K.; Heidari, M.S.; Harsini, P.A.; Azizinia, S. Application of PRECEDE model in education of nutrition and physical activities in obesity and overweight female high school students. Obes. Med. 2019, 14, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwa, M.; Haque, A.; Khalequzzaman, M.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.R.; Choudhury, S.R. Towards reducing behavioral risk factors of non-communicable diseases among adolescents: Protocol for a school-based health education program in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.M.; Zangerolamo, L.; Rosa, L.R.O.; Branco, R.C.S.; Carneiro, E.M.; Barbosa-Sampaio, H.C. Impact of a playful booklet about diabetes and obesity on high school students in Campinas, Brazil. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2019, 43, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Santos-Beneit, G.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Bodega, P.; de Miguel, M.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Rodríguez, C.; Carral, V.; Orrit, X.; Haro, D.; et al. Rationale and design of the school-based SI! Program to face obesity and promote health among Spanish adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am. Heart J. 2019, 215, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, L.; Bradley, J.; Adamson, A.J.; Spence, S. The ‘Voice’ of Key Stakeholders in a School Food and Drink Intervention in Two Secondary Schools in NE England: Findings from a Feasibility Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, L.; Speiser, P.W.; Accacha, S.; Altshuler, L.; Fennoy, I.; Lowell, B.; Rapaport, R.; Rosenfeld, W.; Shelov, S.P.; Ten, S.; et al. Demographics and anthropometrics impact benefits of health intervention: Data from the Reduce Obesity and Diabetes Project. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2019, 5, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askelson, N.M.; Brady, P.; Ryan, G.; Meier, C.; Ortiz, C.; Scheidel, C.; Delger, P. Actively Involving Middle School Students in the Implementation of a Pilot of a Behavioral Economics–Based Lunchroom Intervention in Rural Schools. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 20, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, L.; Legrand, K.; Alleyrat, C.; Ramisasoa, S.; Langlois, J.; Muller, L.; Omorou, A.Y.; De Lavenne, R.; Kivits, J.; Lecomte, E.; et al. Using facilitator–receiver peer dyads matched according to socioeconomic status to promote behaviour change in overweight adolescents: A feasibility study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, M.; Jimenez, C.C.; Lim, J.; Isasi, C.R.; Blank, A.E.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Fredericks, L.; Bouchard, M.; Faith, M.S.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Effective nationwide school-based participatory extramural program on adolescent body mass index, health knowledge and behaviors. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton-Lopez, M.M.; Manore, M.M.; Branscum, A.; Meng, Y.; Wong, S.S. Changes in Sport Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes/Beliefs and Behaviors Following a Two-Year Sport Nutrition Education and Life-Skills Intervention among High School Soccer Players. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Pirzadeh, A.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Mostafavi, F. The Effect of a Social Cognitive Theory-Based Intervention on Fast Food Consumption Among Students. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2018, 12, e10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, M.; Rahimi, A.; Zare-Farashbandi, F.; Naeini, A.A.; Hasanzadeh, A. The effect of nutrition education course on awareness of obese and overweight female 1st-year High School students of Isfahan based on transtheoretical model of behavioral change. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida, S.; Marshall, A.; Henry, R.; Townsend, J.; Toy, A. Attitudes toward Nutrition and Dietary Habits and Effectiveness of Nutrition Education in Active Adolescents in a Private School Setting: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, L.; Masoudi, R.; Lotfizadeh, M. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Nutritional Education based on Health Belief Model on Self-Esteem and BMI of Overweight and at Risk of Overweight Adolescent Girls. Int. J. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jeong, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Suk, S.-H. Stroke awareness in Korean high school students. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2017, 117, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, D.S.; Goulart, M.R.; Barbiero, S.M.; Sica, C.D.; Borges, R.; Moraes, D.W.; Pellanda, L.C. Healthy School, Happy School: Design and Protocol for a Randomized Clinical Trial Designed to Prevent Weight Gain in Children. Arq. Bras. de Cardiol. 2017, 108, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.; Krallman, R.; Jackson, E.A.; DuRussel-Weston, J.; Palma-Davis, L.; de Visser, R.; Eagle, T.; Eagle, K.A.; Kline-Rogers, E. Top 10 Lessons Learned from Project Healthy Schools. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 990.e1–990.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meseri, R.; Ergin, I.; Mermer, G.; Hassoy, H.; Yörük, S.; Çatalgöl, Ş. School based multifaceted nutrition intervention decreased obesity in a high school: An intervention study from Turkey. Prog. Nutr. 2017, 19, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacopoulou, F.; Landis, G.; Rentoumis, A.; Tsitsika, A.; Efthymiou, V. Mediterranean diet decreases adolescent waist circumference. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 47, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamerson, T.; Sylvester, R.; Jiang, Q.; Corriveau, N.; DuRussel-Weston, J.; Kline-Rogers, E.; Jackson, E.A.; Eagle, K.A. Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Health Behaviors Between Black and Non-Black Students Participating in a School-Based Health Promotion Program. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 31, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorick, S.; Fang, X.; Crawford, Y. The MATCH Program: Long-Term Obesity Prevention Through a Middle School Based Intervention. Child. Obes. 2016, 12, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.M.F.d.C.; Lima, K.C.; Alves, M.D.S.C.F. Promoting public health through nutrition labeling—A study in Brazil. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, S.I.Z.S.; Chin, Y.S.; Taib, M.N.M.; Shariff, Z.M. School-based intervention to prevent overweight and disordered eating in secondary school Malaysian adolescents: A study protocol. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.; Irvin, E.; Ostrovsky, N.; Isasi, C.; Blank, A.E.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Fredericks, L.; Yom, T.; Ginsberg, M.; Hayes, S.; et al. Behaviors and Knowledge of HealthCorps New York City High School Students: Nutrition, Mental Health, and Physical Activity. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsile, S.E.; Ogundele, B.O. Effect of game-enhanced nutrition education on knowledge, attitude and practice of healthy eating among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2016, 54, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.L.; Contento, I.R.; Koch, P.A. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum, ‘Choice, Control and Change’. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Joram, E.; Matvienko, O.; Woolf, S.; Knesting, K. Impact of an intuitive eating education program on high school students’ eating attitudes. Health Educ. 2015, 115, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawson, D.L.; Dalton, W.T.; Dula, T.M.; Southerland, J.; Wang, L.; Littleton, M.A.; Mozen, D.; Relyea, G.; Schetzina, K.; Lowe, E.F.; et al. College students as facilitators in reducing adolescent obesity disparity in Southern Appalachia: Team Up for Healthy Living. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 43, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, D.; Fraticelli, F.; Polcini, F.; Lato, R.; Pintaudi, B.; Nicolucci, A.; Fulcheri, M.; Mohn, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Di Vieste, G.; et al. Preventing Adolescents’ Diabesity: Design, Development, and First Evaluation of “Gustavo in Gnam’s Planet”. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweat, V.; Bruzzese, J.-M.; Fierman, A.; Mangone, A.; Siegel, C.; Laska, E.; Convit, A. Outcomes of The BODY Project: A Program to Halt Obesity and Its Medical Consequences in High School Students. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazorick, S.; Fang, X.; Hardison, G.T.; Crawford, Y. Improved Body Mass Index Measures Following a Middle School-Based Obesity Intervention—The MATCH Program. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. The Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in the Region of the Americas, 2000–2019; ENLACE Data Portal; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, T. Practice-ing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Search Term |

|---|---|

| Educational intervention | “Education* program*” OR “Food Education” OR “Health education” OR “Cooking skills” OR “nutrition education” OR “Intervention strategies*” OR “School-based intervention*” |

| AND | |

| Post-primary cohort | “Secondary School*” OR “Post primary” OR “High School” OR “Middle school” |

| AND | |

| Diet-related disease | “Diet* disease*” OR “diet-related disease*” OR “Nutri* related disease*” |

| Author | Title | Country | Study Design | Study Objective | Intervention Detail | Evaluation Process/Outcomes Measured | Duration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Haroni et al., 2024 [58] | Effectiveness of education intervention, with regards to physical activity level and a healthy diet, among Middle Eastern adolescents in Malaysia: A study protocol for a randomised control trial, based on a health belief model | Malaysia | Randomised controlled Trial | To improve knowledge, attitude, and practices about body weight, nutrition, and physical activity among Middle Eastern adolescents | Integrated health education intervention. 6 fortnightly sessions (45 min/session) over 6 weeks. Target group: 13–14-year-olds in Arabic secondary schools in Malaysia. | Anthropometric measurements: -Knowledge, attitude, and practices; -Physical activity and sedentary behaviour; -Food assessment and eating attitudes; -Baseline, post-intervention, and 2-month follow-up. | 2 months total (6-week intervention plus follow-up) | Data collection ongoing. Expected to improve physical activity, diet adherence, and reduce NCD risk behaviours. |

| Aresi et al., 2023 [59] | Process Evaluation of Food Game: A Gamified School-Based Intervention to Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Dietary Choices | Italy | Mixed methods process evaluation | To evaluate and gather information on the food game | Offline and online competitions to design and communicate products and ideas that promote health and sustainability. | Change in perceptions of students. Teacher experience with the programme. | 1 year | Acceptable and engaging intervention. No sufficient evidence to show it promotes healthier/more sustainable behaviours. |

| Miller et al., 2023 [60] | Rethinking Adolescent School Nutrition Education Through a Food Systems Lens | Australia | Mixed methods case study | To explore food systems as an alternative approach to engage students in nutrition education | Played a food systems computer game (“Farm to Fork”). Group discussions on food systems, food production, and food waste. | Key themes identified in group discussions about food production, food waste, and healthy food choices. Request for additional content on food production, costs, processing, and accessing local produce. | 1 year | Students reported crop growth, food production, food waste, and food systems knowledge as game outcomes. Requested more content on food production, handling, and local produce. Preferred experiential learning activities. |

| Rizvi et al., 2022 [61] | Outcome of structured health education intervention for obesity-risk reduction among junior high school students: Stratified cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) in South India | India | Randomised controlled trial | Assess health education’s impact on obesity-related KAP in adolescents and estimate post-intervention changes in BMI and body fat % | Presentation including motivational pictures, phrases and videos. Reinforced with posters and worksheets. | Questionnaire to assess KAP towards diet and physical activity over 3 visits. | 2 years | Intervention group had better knowledge regarding diet and health; however, knowledge improved in both groups. |

| Angeli et al., 2022 [62] | Implementation and Evaluation of a School-Based Educational Program Targeting Healthy Diet and Exercise (DIEX) for Greek High School Students | Greece | Quasi-experimental design | To assess the effectiveness of the DIEX programme in improving adolescents’ knowledge and behaviour regarding healthy diet and exercise | DIEX programme based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), life skills training, and digital elements. 10 sessions, 1 h each, implemented by schoolteachers. Topics included behaviour-modification, goal setting, stress management, problem-solving, and cognitive restructuring. | Changes in students’ knowledge and behaviour regarding healthy eating. Attitudes and satisfaction towards the DIEX program. Perceived impact on subjective norms, intentions, and perceived behavioural control (PBC). | 10 sessions (1 h each) | Significant improvements in knowledge and behaviour related to a healthy diet. Positive attitudes and high satisfaction with the program. No significant impact on subjective norms, intentions, or perceived behavioural control. Programme successfully changed students’ behaviour related to healthier diets. |

| Said et al., 2022 [63] | Effect Evaluation of Sahtak bi Sahnak, a Lebanese Secondary School-Based Nutrition Intervention: A Cluster Randomised Trial | Lebanon | Cluster randomised controlled trial | To evaluate the effectiveness of Sahtak bi Sahnak on dietary knowledge and adherence to dietary guidelines in Lebanese adolescents | Sahtak bi Sahnak: educational school-based intervention. Aimed at improving dietary knowledge, adherence to nutritional guidelines, and preventing obesity. Intervention designed using the intervention mapping framework. | Dietary knowledge and adherence to dietary guidelines measured at baseline and post-intervention using validated questionnaires. | 2 months (7 educational sessions, covering 11 lessons: 20–40 min each) | Improved dietary knowledge. Increased intake of healthy foods. Decreased intake of unhealthy foods. |

| LeBlanc et al., 2022 [64] | An elective high school cooking course improves students’ cooking and food skills: a quasi-experimental study | Canada | Quasi-experimental design | To evaluate the effectiveness of the Professional Cooking (PC) course on cooking skills, food behaviours, and vegetable and fruit consumption | Teaches cooking techniques, food safety, and recipe following. | Cooking skills, food and cooking skills, vegetable and fruit consumption, and eating behaviours measured using pre- and post-questionnaires. | 18 weeks | Significant improvements in cooking skills for students in the PC course. No significant impact on vegetable and fruit consumption or other eating behaviours. |

| Gowland-Ella et al., 2022 [65] | Thirsty? Choose Water! Encouraging Secondary School Students to choose water over sugary drinks. A descriptive analysis of intervention components | Australia | Randomised controlled trial | To evaluate the effectiveness of a behavioural intervention (BI) and a chilled water station (CWS) on encouraging students to choose water over sugary drinks | Behavioural intervention (BI): delivered through classroom lessons, school promotions, and vaccination clinic. Chilled water station (CWS): one CWS installed per school. | Changes in student knowledge about sugary drinks (SSBs) and hydration, daily SSB consumption, water bottle usage, and water consumption measured via student surveys. | 3 time points (baseline, post-intervention, follow-up) (over the course of 1 year) | The BI led to improved student knowledge about sugary drinks and dehydration, along with reduced sugary drink consumption. The CWS resulted in increased water consumption and higher rates of students carrying water bottles to school. |

| Schapiro et al., 2021 [66] | Impact on Healthy Behaviors of Group Obesity Management Visits in Middle School Health Centers | USA | Mixed-methods community-based participatory pilot study | To examine the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of group obesity management visits through school health centres | Group obesity management visits were implemented through three school-based health centres serving primarily Latinx and African American youth. The intervention included group visits with focus on diet, exercise, and stress-reduction mindfulness exercises. | Changes in soda consumption, exercise days, and social support. Knowledge and self-efficacy related to healthy eating. Student focus group feedback on programme activities. | Pre- and post-surveys, focus groups conducted after the intervention and 18 months later | Significant decrease in soda consumption. Increased support from classmates and more exercise days. Positive feedback from students about cooking, tasting, and shopping activities, family involvement and mindfulness techniques. Young people suggested programme refinements, such as better access to healthy foods. |

| Ooi et al., 2021 [67] | A trial of a six-month sugar-sweetened beverage intervention in secondary schools from a socio-economically disadvantaged region in Australia | Australia | Pilot cluster randomised controlled trial | To assess the effectiveness of a multi-component school-based intervention on reducing daily SSB consumption and energy from SSBs in adolescents | The intervention included strategies based on the WHO’s Health Promoting School (HPS) framework, targeting school SSB availability, pricing, health-related self-efficacy, peer influence, and family factors. It involved behavioural change techniques to improve students’ capability and motivation to reduce SSB intake. | Primary outcomes: overall daily SSB consumption (mL), daily percentage of energy from SSBs. Secondary outcomes: SSB consumption at school, daily energy intake (kJ), student BMI z-scores. | Pre- and post-surveys, food frequency questionnaires, BMI measurement 6 months | There were no significant differences between the intervention and control schools for SSB consumption, energy intake, or BMI. Small reductions in SSB consumption and energy from SSBs were observed within the intervention group but were not statistically significant when compared to the control group. The findings suggest the need for more robust implementation strategies and potentially extending the intervention duration. |

| Huitink et al., 2021 [68] | The Healthy Supermarket Coach: Effects of a Nutrition Peer-Education Intervention in Dutch Supermarkets Involving Adolescents With a Lower Education Level | Netherlands | Quasi-experimental pre–post design with a comparison school | To investigate the impact of a supermarket-based nutrition peer education intervention on adolescents’ nutritional knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating | The intervention was held in supermarkets near schools and involved peer education. It aimed to improve adolescents’ nutritional knowledge and attitudes toward healthy eating, particularly targeting those with lower education levels. | Primary outcomes: nutritional knowledge, attitudes toward healthy eating. Secondary outcomes: self-reported dietary behaviours during school hours, food purchases. | Pre- and post-intervention surveys, comparison of intervention and control schools 3 months | Statistically significant improvements in nutritional knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating were found in the intervention group compared to the comparison school. The intervention was well received by participants, and most adolescents reported purchasing food from supermarkets during school hours. |

| Selamat et al., 2021 [69] | Fruit and vegetable intake among overweight and obese school children: A cluster randomised control trial | Malaysia | Cluster randomised controlled trial | To evaluate the effect of a nutrition education intervention (NEI) based on the trans-theoretical model (TTM) on fruit and vegetable intake among overweight and obese secondary school children | The intervention (MyBFF@school) included 24 weeks of NEI with 40–60 min sessions every two weeks. The Nutrition Education Module (NEM) covered five main topics: body weight, healthy eating, smart shopping, and more, focusing on fruit and vegetable intake. The sessions were delivered by trained personnel using interactive and practical methods. | Primary outcome: stages of change for fruit and vegetable intake (action, maintenance, etc.). Secondary outcome: changes in the percentage of children with adequate fruit and vegetable intake. | 24 weeks for intervention group, with 6-month follow-up | No significant differences in stages of change between the intervention and control groups, but both showed a slight reduction in the maintenance stage. The intervention group saw a significant increase in adequate fruit and vegetable intake (from 17.8% to 28%), while the control group showed a smaller increase (from 20.6% to 26.6%). Significant increases in intake were observed in the intervention group at the pre-action and action stages. |

| Orta et al., 2021 [70] | Bridging the GAP: Leveraging Partnerships to Bring Quality Nutrition Education to the Gardening Apprenticeship Program | USA | Programme evaluation (non-RCT) | To assess the impact of a yearlong after-school intervention combining gardening, nutrition education, and hands-on cooking demonstrations to address food insecurity and improve health behaviours in adolescents | The intervention integrated hands-on cooking lessons with nutrition education in the Gardening Apprenticeship Program (GAP). The programme involved garden-based activities teaching food and environmental justice, alongside nutrition lessons from the Nourish curriculum. Each lesson included participatory cooking demonstrations. | Outcomes: participants’ knowledge of fruits and vegetables, food traditions, and influences on food choices. Specific lessons covered topics such as food labels, healthy drinks, and MyPlate. Programme success was assessed via pre- and post-programme evaluation of students’ attitudes and knowledge. | 16 weeks of nutrition education with bi-monthly sessions, part of a yearlong intervention | The programme successfully engaged 12 high school students, enhancing their knowledge of nutrition and improving their skills in cooking healthy meals. Participants demonstrated increased knowledge and confidence in preparing healthy meals and were better able to identify the benefits of fruits and vegetables. |

| Berger et al., 2021 [71] | The Impact of a Short-term Intervention on Adolescent Eating Habits and Nutritional Knowledge | Israel | Prospective questionnaire-based study | To evaluate the effects of a school-based intervention on adolescents’ nutritional knowledge, eating habits, and physical activity | The intervention included the installation of vending machines with milk products, two nutrition lectures on age-appropriate nutrition and calcium, and one active sports day. | Outcomes: changes in eating habits (e.g., breakfast consumption, food purchasing habits), calcium knowledge, milk consumption, and physical activity levels. | One academic year (September 2014 to September 2015) | A significant increase in students eating breakfast. A decrease in the purchase of food at school. No significant changes were observed in milk consumption, vegetable consumption, knowledge about calcium, or physical activity. |

| Ibeanu et al., 2020 [72] | Evidence-based strategy for prevention of hidden hunger among adolescents in a suburb of Nigeria | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental, pretest and post-test | To evaluate the impact of a 14-page nutrition education aid on adolescents’ knowledge of micronutrients and their food choices | The intervention involved a 14-page locally developed nutrition education aid, which included nutrition facts, pictures of micronutrient-rich foods, and computer graphics. The intervention aimed to improve knowledge on food sources, functions, and deficiencies in micronutrients such as vitamin C, folic acid, iron, calcium, and zinc. | Pre- and post-intervention knowledge of nutrition and food choices; consumption of micronutrient-rich foods before and after the intervention. | 6 months (September 2016–July 2017) | Post-intervention, there was a significant improvement in nutrition knowledge, particularly regarding general nutrition and food sources of nutrients. Additionally, there was an increase in the daily consumption of micronutrient-rich foods such as meat, mango, watermelon, carrot, and leafy vegetables, while the proportion of students who rarely consumed these foods decreased. |

| Shen et al., 2020 [73] | The smartphone-assisted intervention improved perception of nutritional status among middle school students | China | Parallel-group controlled trial (non-randomised) | To examine the effectiveness of a smartphone-assisted intervention on improving students’ and parents’ perception of students’ nutritional status | There were three components: health education sessions for students and parents, regular monitoring of students’ weight, and providing feedback through a smartphone application. Schools in the control group continued their usual practices. | Primary outcomes measured were the students’ and parents’ accurate perceptions of students’ nutritional status (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese). | 3 months | The percentage of students in the intervention group who accurately perceived their nutritional status increased, while the control group showed a decrease. However, the intervention did not significantly improve parental perception of students’ nutritional status. |

| Westfall et al., 2020 [74] | Exploring the Relationship Between MyPlate Knowledge, Perceived Diet Quality, and Healthy Eating Behaviors Among Adolescents | USA | Secondary analysis of cross-sectional data | To evaluate middle school students’ knowledge of MyPlate nutrition messages and its association with dietary intake and perceived diet quality | The study assessed students’ knowledge of MyPlate using three questions about portion sizes (fruits and vegetables, grains, proteins). It also used a brief food frequency questionnaire to assess intake of various foods and beverages. | The study measured MyPlate knowledge, intake of fruits, vegetables, sweets, salty snacks, fast food, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), as well as students’ self-rated diet quality. | 1 academic year (eighth grade) | MyPlate Knowledge: Only 11% of the students correctly answered all questions related to MyPlate portion sizes. Dietary Intake: MyPlate knowledge was associated with a reduced likelihood of consuming sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), but it was also linked to higher consumption of sweets. There was no significant impact on the intake of fruits, vegetables, salty snacks, or students’ self-perceived diet quality. |

| Jeihooni et al., 2019 [75] | Application of PRECEDE model in education of nutrition and physical activities in obesity and overweight female high school students | Iran | Quasi-experimental study | To assess the impact of an educational intervention based on the PRECEDE model on the nutrition and physical activity behaviours, and weight/BMI of overweight and obese female high school students | Educational intervention based on the PRECEDE model, delivered through 10 sessions (50–55 min each) focusing on nutrition, physical activity, and behaviour change. | Questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, enabling and reinforcing factors, physical and nutrition performance, weight, and BMI. | 3 months | Significant improvements in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, and physical/nutritional behaviours were observed in the experimental group. A reduction in weight and BMI was also noted in the experimental group, with no changes in the control group. |

| Salwa et al., 2019 [76] | Towards reducing behavioral risk factors of non-communicable diseases among adolescents: Protocol for a school-based health education program in Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Before–after design intervention study | To implement and evaluate a behaviour change intervention aimed at reducing behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among adolescents in Bangladesh | Health promotion sessions based on motivational interviewing and social cognitive theory, delivered in groups of up to 25 students by trained facilitators. | Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAPs) related to NCDs were assessed before and after the intervention using a questionnaire. | 3 months | Results yet to be collected. Expected outcomes include increased awareness and behaviour change regarding NCD risk factors, with a focus on cost-effectiveness and group delivery. |

| Soares et al., 2019 [77] | Impact of a playful booklet about diabetes and obesity on high school students in Campinas, Brazil | Brazil | Pretest–post-test design | To evaluate the efficacy of a playful educational booklet focused on diabetes and obesity for high school students | A playful educational booklet with illustrations, games, and activities about diabetes and obesity. The booklet includes a range of activities from simple games to more complex knowledge-based tasks. | Student performance on a 10-question test was measured before and after using the booklet. The number of correct answers for each question was tracked. | 1 h (booklet completion time) | Significant improvement in quiz performance after using the booklet. The percentage of correct answers increased in 7 out of 10 questions (p < 0.05). The greatest improvements were in questions 5 (36%), 8 (19%), and 6 (15%). |

| Fernandez-Jimenez et al., 2019 [78] | Rationale and design of the school-based SI! Program to face obesity and promote health among Spanish adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial | Spain | Cluster-randomized controlled trial | To evaluate the impact of the SI! Programme on adolescent lifestyle behaviours and health parameters. | The intervention involved a multilevel, multicomponent school-based health-promotion intervention targeting adolescents aged 12–16 years. It includes a curriculum-based educational programme over 2 or 4 academic years. | Primary endpoint: change in composite Ideal Cardiovascular Health (ICH) score (BMI, dietary habits, physical activity, smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose) at 2-year and 4-year follow-ups. Secondary endpoints: changes in ICH subcomponents, Fuster–BEWAT health scale, adiposity markers, polyphenol and carotenoid intake, and emotion management. | 2–4 years | Results yet to be collected. |

| McSweeney et al., 2019 [79] | The ‘voice’ of key stakeholders in a school food and drink intervention in two secondary schools in NE England: Findings from a feasibility study | United Kingdom | Qualitative study using focus groups and interviews | To explore perceptions of school food provision and a food architecture intervention among pupils and staff | The intervention involved rearranging the placement of food items: fruit placed in front of cakes/cookies, and water positioned at eye level. | Thematic analysis of pupil focus groups (n = 4) and staff interviews (n = 8); assessed dining practices, food choices, health awareness, and intervention knowledge. | Not specified | Pupils are aware of healthy options but often chose less healthy ones; structural changes improved the visibility and convenience of healthier choices, but mixed messages and food availability limited effectiveness. |

| Ostrowski et al., 2019 [80] | Demographics and anthropometrics impact benefits of health intervention: data from the Reduce Obesity and Diabetes Project | USA | Quasi-experimental, school-based intervention | To evaluate the efficacy of a 4-month health, nutrition, and exercise intervention on body fat in middle school students | Included a 12-session classroom-based health and nutrition programme incorporated into regular curriculum; optional exercise intervention offered. | Height, weight, waist circumference, BMI, and body composition measured pre- and post-intervention; subgroup analysis based on demographic and anthropometric factors. | 4 months | Significant reductions in adiposity indices (BMI z-scores, body fat %, waist circumference); greater effects in males, obese students, and South Asians. |

| Askelson et al., 2018 [81] | Actively Involving Middle School Students in the Implementation of a Pilot of a Behavioural Economics–Based Lunchroom Intervention in Rural Schools | USA | Pilot study with multicomponent evaluation | To improve the lunchroom environment and empower food service staff to encourage healthy eating behaviours among middle school students | The intervention involved changes to the lunchroom environment using behavioural economics principles, communication training for food service staff, and food service staff cues to encourage healthy food choices. | Lunchroom assessments, surveys, production records, and interviews with food service directors and staff. | 1 academic year | Five schools showed improvement in lunchroom assessment scores, and four schools increased the production of healthy food servings. Food service directors reported the intervention as feasible and well received. |

| Saez et al., 2018 [82] | Using facilitator-receiver peer dyads matched according to socioeconomic status to promote behaviour change in overweight adolescents: A feasibility study | France | Feasibility study (embedded within larger trial) | To evaluate the feasibility of a peer intervention promoting healthy eating and physical activity, targeting less-advantaged overweight adolescents | Peer facilitators, selected according to socioeconomic status, were trained to organize weight-control activities for peer receivers. | Primary: demand, acceptability, implementation, and practicality of the intervention. Secondary: socio-demographic and health characteristics; participant feedback on the experience. | 1 year (larger study: 3 years) | Participation was higher when asked by peers (51.2% discordant pairs, p < 0.02). Participants (mostly girls, mean age 16) reported positive experiences, especially regarding social support. |

| Heo et al., 2018 [83] | Effective nationwide school-based participatory extramural program on adolescent body mass index, health knowledge and behaviors | USA | Quasi-experimental (pre-post comparison) | To evaluate the effectiveness of the HealthCorps programme on BMI z-scores, obesity rates, health knowledge, and behaviours among high school students | HealthCorps provided weekly or bi-weekly classroom lessons and after-school activities focusing on nutrition, physical activity, sleep, breakfast intake, and mental resilience. | Primary: changes in BMI z-scores. Secondary: changes in health knowledge and behaviours (fruit/vegetable intake, physical activity). | 1 academic year | Significant decrease in BMI z-scores for overweight/obese and obese female students in the HealthCorps group. HealthCorps students showed significant increases in health knowledge and positive behaviour changes compared to the comparison group. |

| Patton-Lopez et al., 2018 [84] | Changes in sport nutrition knowledge, attitudes/beliefs and behaviors following a two-year sport nutrition education and life-skills intervention among high school soccer players | USA | Pre-post design (3-time assessments) | To evaluate the impact of a sport nutrition education and life-skills intervention on sport nutrition knowledge (SNK), attitudes/beliefs, and dietary behaviours among high school soccer players. | The WAVE programme included face-to-face sports, nutrition lessons, experiential learning, and team-building workshops (TBWs) focusing on nutrition and life skills such as meal planning, shopping on a budget, and food preparation. | Primary: changes in SNK scores, attitudes/beliefs, and dietary behaviours (breakfast, lunch consumption, eating for performance). | 2 years | Significant improvements in SNK scores, especially in female athletes. IG players were more likely to report eating for performance and showed increased lunch consumption. The intervention also increased awareness of athletes’ nutritional needs compared to non-athletes. |

| Ahmadi et al., 2018 [85] | The effect of a social cognitive theory-based intervention on fast food consumption among students | Iran | Quasi-experimental (pre-post comparison) | To determine the effect of a social cognitive theory (SCT)-based intervention on fast food consumption among students | The intervention consisted of 4 sessions: defining fast food and its detriments, discussing value expectations (health risks), and improving self-efficacy to replace fast foods with healthier options. | Primary: changes in fast food consumption, self-efficacy, knowledge, and outcome expectations. Pre- and post-survey 3 months after intervention. | 4 sessions (conducted within a short period) | Significant reduction in fast food consumption in the intervention group (p < 0.001). Improved self-efficacy, knowledge, and outcome expectancy in the intervention group. The control group showed no significant changes. The intervention group had significantly better scores in fast food consumption, knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectancy compared to the control group. |

| Hashemzadeh et al., 2018 [86] | The effect of nutrition education course on awareness of obese and overweight female 1st-year High School students of Isfahan based on transtheoretical model of behavioral change | Iran | Semi-empirical (pretest-post-test with control and experimental groups) | To investigate the effects of a nutrition education course on the awareness of female 1st-year high school students based on the transtheoretical model (TTM) of behavioural change | Sessions every 2 weeks, with one brochure and 3 educational messages each week for the experimental group. | Pre- and post-intervention surveys using the following: Nutrition Awareness Questionnaire (15 items); Stages of Change Questionnaire. Statistical analysis: Independent t-test and Mann–Whitney test. | 2 months | Significant improvement in nutrition awareness scores and progression to higher stages of change in the experimental group. The control group showed no significant changes. The intervention was effective in improving students’ awareness and behavioural stages related to nutrition. |

| Partida et al., 2018 [87] | Attitudes toward nutrition and dietary habits and effectiveness of nutrition education in active adolescents in a private school setting: A pilot study | USA | Pilot survey study | To investigate nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about nutrition, exercise, and dietary habits of active adolescents | Three-part nutrition education intervention: -2 sessions by a registered dietitian in the classroom for middle school and high school students; -Educational posters; -Social media. | Surveys before and after intervention: -General and sport nutrition knowledge; -Dietary habits; -Attitudes toward nutrition education; -Self-reported exercise and sports participation. | Approx. 1 month | Most students expressed a desire to learn more about nutrition. The most effective delivery method was classroom lectures. Educational posters and social media were ineffective. Significant increase in knowledge about protein and exercise. Need for improvement in both general and sports nutrition knowledge. |

| Rabiei et al., 2017 [88] | Evaluation of the effectiveness of nutritional education based on the health belief model on self-esteem and BMI of overweight and at risk of overweight adolescent girls | Iran | Randomized controlled trial | To determine the effectiveness of nutrition education based on the health belief model (HBM) on self-esteem and BMI of overweight and at-risk adolescent girls | Health belief model-based intervention: -6 sessions (60 min each) focusing on overweight prevention. Topics: perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, self-efficacy. Educational materials: lectures, Q&A, slides, booklets. | Pre- and post-intervention evaluations: -Knowledge: based on HBM structures; -Self-esteem: assessed via self-report; -BMI: measured by standardized tools; -Perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and self-efficacy: questionnaire scores. | 3 months | Significant improvements in knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and self-esteem in the intervention group. BMI significantly decreased in the intervention group but not in the control group. Positive long-term effects on knowledge and behaviour were observed. |

| Park et al., 2017 [89] | Stroke awareness in Korean high school students | South Korea | Pretest and post-test intervention study | To investigate the basic knowledge of Korean adolescents about stroke and evaluate the improvement after an educational lecture | Stroke education program: 50-min lecture on stroke: risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis, and management. Emphasised modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, etc. | Pre-E, Post-E1, Post-E2 questionnaire: -Knowledge assessment on stroke risk factors, symptoms, and management; -Performance comparison on Pre-E, Post-E1, and Post-E2 tests; -Difference in performance for students who reported paying attention. | 2 weeks | Significant improvement in stroke knowledge immediately after the lecture and at 2-week follow-up (p < 0.001). The students who paid attention during the lecture showed greater improvement in knowledge. The study supports incorporating stroke education into school curricula to reduce stroke risk behaviours in adolescents. |

| Schuh et al., 2017 [90] | Healthy school, happy school: Design and protocol for a randomized clinical trial designed to prevent weight gain in children | Brazil | Cluster-randomised parallel two-arm study | To evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention designed to improve knowledge of food choices and lifestyle in children and adolescents | Intervention activities: -Monthly activities in school’s multimedia room or sports court focusing on the following: -Nutritional education, physical activity, and lifestyle changes. -Control group receives usual school recommendations. | Primary outcomes: -Anthropometric measures (BMI percentiles); -Physical activity levels (International Physical Activity Questionnaire). Secondary outcomes: -Healthy eating behaviours, preferences for fruits/vegetables, increased physical activity, reduced sedentary behaviour. | Ongoing | Results not collected. Expected Outcomes: Increased consumption of fresh foods. Decreased consumption of sugary/processed foods. Reduced sedentary behaviour. The goal is to equip children with knowledge to make healthier choices for a better future. |

| Rogers et al., 2017 [91] | Top 10 Lessons Learned from Project Healthy Schools | USA | Non-randomized, observational study | To evaluate the effectiveness of Project Healthy Schools (PHSs) on improving childhood obesity and associated cardiovascular risk factors | Project Healthy Schools (PHSs): a school-based programme focusing on health education and environmental changes to promote healthy lifestyle choices in middle school students. -10 educational sessions (20–45 min each) covering topics such as healthy eating, physical activity, and reducing sedentary behaviour. -Environmental changes, such as providing healthier food and beverage options in schools. | Primary outcome: -Physiologic changes (e.g., lipid levels). Secondary outcome: -Health behaviours (e.g., diet, physical activity). | N/A | Improved Health Outcomes: Significant improvements in physiological measures (e.g., lipid profiles) and health behaviours (e.g., increased physical activity, healthier eating). Behavioural Changes: Students consumed healthier foods, engaged in more physical activity, and reduced screen time. Impact of Environmental Changes: The availability of healthier food and beverage options in schools supported these positive changes. |

| Meseri et al., 2017 [92] | School based multifaceted nutrition intervention decreased obesity in a high school: An intervention study from Turkey | Turkey | Interventional study | Assess nutritional knowledge, behaviours, and obesity status among high school students before and after interventions | Multifaceted nutrition and physical activity interventions, including lessons, changes to food environment, and support for PA. | BMI percentiles for obesity status, nutritional knowledge (10 multiple-choice questions), and behaviours via a nutrition score (scale 1–10). | 1 year | Improved nutritional knowledge and behaviours; reduced mean BMI and overweight prevalence. There was a 25.7% reduction in overweight prevalence post-intervention. |

| Bacopoulou et al., 2017 [93] | Mediterranean diet decreases adolescent waist circumference | Greece | Multicomponent-multilevel intervention | Explore the effects of a school-based educational intervention on nutritional habits and abdominal obesity indices | A 6-month school-based programme with 36 adolescent sessions, 9 parent sessions, and workshops for teachers and health staff, addressing the Mediterranean diet (MD), PA, and healthy body image. Tailored guidebooks and an educational website. | Dietary habits via KIDMED index, BMI, WC, waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), blood pressure. Measurements at baseline and post-intervention. | 6 months | Increased adherence to the MD; reduced waist circumference, WHtR, overweight/obesity prevalence, and BP. Living with both parents and higher parental education were associated with better dietary adherence. |

| Shahnazi et al., 2016 [17] | Can the BASNEF Model Help to Develop Self-Administered Healthy Behavior in Iranian Youth? | Iran | Quasi-experimental intervention study | To determine the effectiveness of an educational intervention programme based on the BASNEF model to improve nutritional habits and lifestyle among high school students | Four educational sessions (120–150 min each), implementing dietary changes at school and home. Activities included hands-on tasks, video presentations, exhibitions, group discussions, and educational materials (pamphlets, CDs, and slides). Topics included obesity awareness, healthy eating habits, physical activity benefits, and dietary recommendations. | Beliefs and attitudes about nutrition using BASNEF scores. Frequency of physical activity. Evaluation through pretest, post-test, and follow-up with Likert-scale questionnaires and student diaries. | 3 months (follow-up post-intervention) | Significant improvement in nutritional beliefs (79.2% for girls, 70.1% for boys) and attitudes (61.2% for girls, 59.4% for boys) in the intervention group compared to controls (p < 0.001). Physical activity increased significantly (p < 0.001). BASNEF model deemed effective for fostering long-term healthy habits. |

| Jamerson et al., 2016 [94] | Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Health Behaviors between Black and Non-Black Students Participating in a School-Based Health Promotion Program | USA | Pre–post intervention, survey-based design | To compare cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors of black and non-black children participating in Project Healthy Schools (PHSs) | Project Healthy Schools Intervention: -A school-based wellness programme to reduce obesity and CVD risk by promoting healthy eating and physical activity. -Includes 10 interactive lessons, assemblies, school events, after-school activities, and collaboration with food service vendors for healthier meal options. | Primary outcome: -Changes in physiological measures (e.g., BMI, blood tests). Secondary outcome: -Changes in dietary habits, physical activity levels, and sedentary behaviour (self-reported surveys). | Baseline and follow-up measurements (time not specified) | At baseline, black students had higher rates of obesity and poorer health habits, while non-black students had worse lipid profiles. Post-intervention, both groups showed significant improvements in health behaviours and physiological measures. Early intervention is effective in modifying CVD risk, particularly in high-risk groups. |

| Lazorick et al., 2016 [95] | The MATCH Program: Long-Term Obesity Prevention Through a Middle School Based Intervention | USA | Quasi-experimental study | To evaluate the long-term effectiveness of MATCH, a school-based obesity intervention for adolescents, on BMI and health behaviours | MATCH integrated into regular 7th-grade curriculum. Teachers delivered 26–30 lessons in science and other classes over 14 weeks. Key components included: -Web-based BMI and nutrition tools; -Graphing software for personal data analysis; -Pedometers and non-food incentives. | BMI and zBMI (standardized BMI) changes. Weight categories (obesity incidence/remission). Self-reported dietary habits (e.g., sweetened beverage and snack intake, TV viewing time). | 14 weeks (intervention) + 4 years (follow-up) | The MATCH group had a significant reduction in zBMI (−0.15 vs. +0.04 in control, p = 0.02). Lower obesity incidence (13% vs. 39%) and higher remission to healthy weight (40% vs. 26%) in the MATCH group. Improved health behaviours: reduced sweetened beverage/snack intake and TV viewing. MATCH demonstrates long-term potential for obesity prevention. |

| Souza et al., 2016 [96] | Promoting public health through nutrition labelling-a study in Brazil | Brazil | Quasi-experimental study | To evaluate the effectiveness of an educational intervention on nutrition labelling to promote healthy food choices | Participants received a 50 min dialogue and exposure session covering the following: -Nutrition-labelling legislation; -Importance of nutrition info for chronic disease prevention; -Traffic light system for sugar, fat, sodium, and fibre content; -Folder with educational material. | -Pretest and post-test questionnaire. -Questions assessed: • Frequency of consulting nutrition labels; • Ability to identify healthy foods using a traffic light system. -Statistical analysis: McNemar test and Wilcoxon test for response comparison (p < 0.05 significant). | 30 days | Participants consulting nutrition labels increased significantly from 55.8% to 72.0% (p < 0.001). Borderline significance in changes regarding the purchase of packaged foods. The intervention was feasible, improved label usage knowledge, and reinforced the importance of healthy food choices. |

| Ishak et al., 2016 [97] | School-based intervention to prevent overweight and disordered eating in secondary school Malaysian adolescents: A study protocol | Malaysia | Quasi-experimental study | To promote a healthy lifestyle, prevent overweight, and reduce disordered eating among adolescents | -Target group: secondary school adolescents (ages 13–14). -Peer-education strategy: peers conveyed knowledge and taught skills. -Promoted the following: • Healthy eating habits; • Positive body image; • Active lifestyle. | -Parameters assessed at baseline, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up: • Body weight; • Disordered eating; • Stages of change for diet and activity behaviours; • Body image, quality of life, self-esteem; • Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards a healthy lifestyle; • Eating and physical activity behaviours. | Intervention duration not specified; assessments conducted over multiple time points | Results to be collected. Expected outcomes include positive effects on body weight and healthy lifestyle behaviours. Prevention of disordered eating and overweight. Improvements in quality of life, self-esteem, and peer educators’ health-related knowledge. |

| Heo et al., 2016 [98] | Behaviors and Knowledge of HealthCorps New York City High School Students: Nutrition, Mental Health, and Physical Activity | USA | Quasi-experimental | To evaluate effects of HealthCorps curricula on nutrition, mental health, and physical activity knowledge and behaviour | HealthCorps programme included classroom teaching, mentoring, wellness councils, afterschool clubs, health fairs, Teen Battle Chef, and Youth-Led Action Research. | Knowledge: nutrition, physical activity, and mental health; Behaviour: fruit/vegetable intake, breakfast consumption, SSB intake, energy-dense foods; changes by sex. | 1 academic year (2012–2013) | Significant improvements in all knowledge domains (p < 0.05). Key behavioural changes: • Boys: increased fruit/vegetable intake (p = 0.03). • Girls: increased acceptance of fruits/vegetables, breakfast consumption, decreased consumption of sugary drinks (p < 0.05). -Knowledge–behaviour links stronger for boys. |

| Ogunsile and Ogundele, 2016 [99] | Effect of game-enhanced nutrition education on knowledge, attitude and practice of healthy eating among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental (non-equivalent group) | To evaluate the main effect of nutrition education on knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to healthy eating among adolescents | Eight-week nutrition education programme conducted in Ibadan, Oyo State. Topics included nutritional needs, importance of breakfast, effects of sugary foods and drinks, etc. Sessions lasted 1 h 20 min weekly and were facilitated by a researcher and four trained assistants. | ANCOVA for knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthy eating; gender and geographical location effects analysed; post-test mean scores compared by group and location. | January–March 2014 3 months | Significant main effects of nutrition education on knowledge (36% variance), practice (31.3%), and attitude (12.1%). Moderate effect sizes for knowledge and practice. Urban participants had higher knowledge; peri-urban participants demonstrated better practices. |