Abstract

Trust management provides an alternative solution for securing open, dynamic, and distributed multi-agent systems, where conventional cryptographic methods prove to be impractical. However, existing trust models face challenges such as agent mobility, which causes agents to lose accumulated trust when moving across networks; changing behaviors, where previously reliable agents may degrade over time; and the cold start problem, which hinders the evaluation of newly introduced agents due to a lack of prior data. To address these issues, we introduced a biologically inspired trust model in which trustees assess their own capabilities and store trust data locally. This design improves mobility support, reduces communication overhead, resists disinformation, and preserves privacy. Despite these advantages, prior evaluations revealed the limitations of our model in adapting to provider population changes and continuous performance fluctuations. This study proposes a novel algorithm, incorporating a self-classification mechanism for providers to detect performance drops that are potentially harmful for service consumers. The simulation results demonstrate that the new algorithm outperforms its original version and FIRE, a well-known trust and reputation model, particularly in handling dynamic trustee behavior. While FIRE remains competitive under extreme environmental changes, the proposed algorithm demonstrates greater adaptability across various conditions. In contrast to existing trust modeling research, this study conducts a comprehensive evaluation of our model using widely recognized trust model criteria, assessing its resilience against common trust-related attacks while identifying strengths, weaknesses, and potential countermeasures. Finally, several key directions for future research are proposed.

1. Introduction

Conventional cryptographic methods, such as the use of certificates, digital signatures, and Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), depend on a static, centralized authority for certificate verification. However, this approach may be impractical or insecure in open, dynamic, and highly distributed networks [1]. Additionally, entities in such networks may have limited resources, making it difficult for them to handle the computational demands of cryptographic protocols [2]. To overcome these challenges, trust management provides an alternative approach, enabling entities to gather reliable and accurate information from their surrounding network.

Various methods for evaluating trust and reputation have been developed for real-world distributed networks that can be considered multi-agent systems (MASs), such as peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, online marketplaces, pervasive computing, Smart Grids, the Internet of Things (IoT), and many more. However, existing trust management approaches still face major challenges. In open MASs, agents frequently join and leave the system, making it difficult for most trust models to adapt [3]. Additionally, assigning trust values in the absence of evidence and detecting dynamic behavioral changes remain unresolved issues [4]. Trust and reputation models, which rely on data-driven methods, often struggle when assessing new agents with no prior interactions. This issue, known as the cold start problem, commonly arises in dynamic groups where agents may have interacted with previous neighbors but lack connections to newly introduced agents. Moreover, in dynamic environments, agents’ behaviors can change rapidly, necessitating that consumer agents recognize these changes to select reliable providers. The challenge in trust assessment lies in the fact that behavioral changes occur at varying speeds and times, making conventional methods, such as forgetting old data at a fixed rate, ineffective [4].

To address these challenges, we previously introduced a novel trust model for open MASs, inspired by synaptic plasticity, the process that enables neurons in the human brain to form structured groups known as assemblies, which is why we named our model “Create Assemblies (CA)”. CA’s distinguishing characteristic is that, unlike traditional trust models where the trustor selects a trustee, CA allows the trustee to determine whether it has the necessary skills to complete a given task. To briefly describe the CA approach, we note that activities are initiated by a service requester, the trustor, which broadcasts a request message that includes task details such as its category and specific requirements. Upon receiving the request, potential trustees (i.e., service providers within the service requester’s vicinity) store the message locally and establish a connection with the trustor if one does not already exist. Each connection is assigned a weight, a value between 0 and 1, representing the trust level or the probability of the trustee successfully completing the task. In the CA model, trust update is event-driven. After the task’s completion, the trustor provides performance feedback, which the trustee uses to adjust the connection weight—increasing it for successful execution and decreasing it otherwise.

The CA approach offers several key advantages in open and highly dynamic MASs due to its unique design, where the trustor does not select a trustee, and all trust-related data concerning the trustee are stored locally within the trustee. First, since each trustee retains its own trust information, these data can be readily accessed and utilized across different applications or systems the agent joins. This provides a major advantage in handling mobility, an ongoing challenge in MASs [5]. By allowing a new service provider to estimate its performance for a given task based on past executions in other systems, the CA model effectively addresses the cold start problem. Second, in conventional trust models, trustors must collect and exchange extensive trust information (e.g., recommendations) before making a selection, leading to increased communication overhead. This is particularly problematic in resource-constrained networks, where communication is more expensive than computation [2]. Sato and Sugawara explained in [6] that task allocation in such settings is a complex combinatorial problem, requiring multiple message exchanges. In contrast, the CA model reduces this burden by limiting communication to request messages from service requesters and feedback messages containing performance ratings, significantly minimizing communication time and overhead. Third, since agents in the CA model do not share trust information, this approach is inherently more resistant to disinformation tactics, such as false or dishonest recommendations, which are common in other trust-based approaches. However, as we will discuss later, there are still some potential vulnerabilities that need to be addressed. Finally, privacy concerns often discourage agents from sharing trust-related data in traditional models. Since CA does not rely on recommendations, agents do not have to disclose how they evaluate others’ services, thereby preserving their privacy.

In our previous work [7], we proposed a CA algorithm as a solution for managing the constant entry and exit of agents in open MASs, as well as their dynamic behaviors. Through an extensive comparison between CA and FIRE, a well-known trust model for open MASs, we found the following:

- CA demonstrated stable performance under various environmental changes;

- CA’s main strength was its resilience to fluctuations in the consumer population (unlike FIRE, CA does not depend on consumers for witness reputation, making it more effective in such scenarios);

- FIRE was more resilient to changes in the provider population (since CA relies on providers’ self-assessment of their capabilities, newly introduced providers—who lack prior experience—must learn from scratch);

- Among all environmental changes tested, the most detrimental to both models was frequent shifts in provider behavior, particularly when providers switched performance profiles, where FIRE exhibited greater resilience than CA.

Motivated by these findings, this work begins with a semi-formal analysis aimed at identifying potential modifications to the CA algorithm that could enhance its performance when dealing with dynamic trustees’ profiles. Based on this analysis, we introduce an improved version of the CA algorithm with a key modification: after providing a service, a service provider re-evaluates its performance, and if it falls below a predefined threshold, it classifies itself as a bad provider. This modification ensures that each provider maintains an up-to-date evaluation of its own performance, allowing for the immediate detection of performance drops that could harm consumers. Next, we conduct a series of simulation experiments to compare the performance of the updated CA algorithm against the previous version. The results demonstrate that the new version outperforms the original CA algorithm under all tested environmental conditions. In particular, when trustees change performance profiles, the improved CA algorithm surpasses both FIRE and its earlier version. We then present a comprehensive evaluation of the CA model based on thirteen widely recognized trust model criteria from the literature. While the model satisfies essential criteria such as decentralization, subjectivity, context awareness, dynamicity, availability, integrity, and transparency, further research and enhancements are identified. In this work, we make the assumption of willing and honest agents, but we acknowledge that our solution should be made generalizable to more realistic settings, where dishonesty and unwillingness are common conditions among agents’ societies. To this end, we examine CA’s resilience against common trust-related attacks, highlighting its strengths and limitations while proposing potential countermeasures. To our knowledge, addressing both openness and dishonesty together is novel.

This thorough assessment not only underscores the model’s strengths but also reflects a commitment to ongoing improvement, establishing it as a promising foundation for future trust management solutions in critical applications, such as computing resources, energy sharing, and environmental sensing—particularly in highly dynamic and distributed environments where security and privacy are paramount. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews several trust management protocols related to our work. Section 3 provides background information concerning the CA and FIRE models, as well as the original CA algorithm. In Section 4, we conduct a semi-formal analysis of the CA algorithm’s behavior, leading to the introduction of a new version that avoids unwarranted task executions. Section 5 outlines the experimental setup and the methodology for the simulation experiments, with the results presented in Section 6. Section 7 offers a comprehensive evaluation of the CA model, based on widely accepted evaluation criteria, while Section 8 examines its robustness against common trust-related attacks. Finally, Section 9 concludes our work and suggests potential directions for future work.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review various trust management protocols relevant to our work. First, we identify IoT service crowdsourcing as a suitable domain for implementing trustee-oriented models, like CA. We then explore different methods proposed to address the cold start problem and agent mobility, highlighting how our approach tackles these challenges. Additionally, we review existing solutions for handling agents’ dynamically changing behaviors, discuss their limitations, and explain how the CA model effectively addresses this issue. Next, we review two representative trust management protocols which, like CA, assign service providers the responsibility of assessing their ability to fulfill a requested task and deciding whether to accept or reject service requests, comparing their similarities and differences with our approach. Lastly, we emphasize that when service requesters lose control over selecting service providers, a mechanism is required to encourage honest service provision. To strengthen the CA model’s robustness against trust-related attacks, we review several trust management protocols with promising mechanisms that could be integrated into our approach.

2.1. Trust Models for IoT Service Crowdsourcing

The unique design of the CA model makes it well suited for IoT service crowdsourcing, where IoT devices offer services to nearby devices, known as crowdsourced IoT services. These services can include computing resources, energy sharing, and environmental sensing. For instance, in energy-sharing services, IoT devices acting as service providers can wirelessly transfer energy to nearby devices with low battery levels, which act as service consumers. Two key characteristics of IoT platforms necessitate specialized trust management frameworks, like the CA model; these are device volatility (IoT devices have a short lifespan, frequently joining and leaving the network) and context-aware trust (trustworthiness in IoT environments is influenced by various factors, such as the owner’s reputation, the operating system, and the device manufacturer).

In [8], Samuel et al. presented a Blockchain-Based Trust Management System (BTMS) for energy trading, integrating blockchain, trust management, and MASs to enhance security and reliability. The system is structured into four layers: a Blockchain Layer, which securely stores and encrypts trust values and feedback; Aggregator Layer, where coalitions of agents are managed by consensus-elected aggregators that assess trust and update blockchain records; Prosumer Layer, consisting of energy-producing and -consuming agents that trade energy while exchanging trust data with aggregators; and a Physical Layer, which includes distributed energy resources such as solar panels, wind turbines, and energy storage. The trust evaluation process incorporates direct and indirect assessments using a weighted average method, while multi-source feedback from aggregators is stored on the blockchain. Trust credibility is determined based on trust distortion, consistency, and reliability, ensuring accurate evaluation and identifying dishonest agents. Additionally, each agent is assigned a token, known as a Balanced Trust Incentive (BTI) unit, which is used to interact with other agents. BTI increases with honest behavior and decreases when dishonesty is detected, fostering a transparent and trustworthy energy trading environment.

Khalid et al. [9] build upon the Blockchain-Based Trust Management System (BTMS) introduced by Samuel et al. [8], addressing unresolved challenges related to agent-to-agent cooperation and privacy in trust management within MASs. Khalid et al. identify that while the original BTMS effectively integrates blockchain with trust management to enhance security and reliability in energy trading, it lacks mechanisms to (i) foster agent-to-agent cooperation, as in dynamic and decentralized environments, agents may behave selfishly or maliciously, undermining collective system performance; and (ii) ensure privacy preservation, as agents are concerned about their privacy and security, making it inappropriate for them to reveal trust information to others. To address these issues, Khalid et al. leverage game theory, treating trust evaluation as a repeated game to encourage effective agent cooperation. In this framework, agents that refuse to cooperate face penalties in subsequent rounds, as others will also decline cooperation. A Tit-3-For-Tat (T3FT) strategy is employed, immediately penalizing noncooperative agents, with the punishment duration depending on their level of cooperation. Defaulter agents may regain their trust after cooperating for three consecutive plays. Afterwards, their cheating behavior is forgiven. To ensure secure and verifiable trust evaluation, a Publicly Verifiable Secret Sharing (PVSS) mechanism is implemented. It distributes sensitive information, such as cryptographic keys, among three entities: dealers (blockchain miners) who allocate shares, participants who store shares, and a combiner (aggregator) who reconstructs the secret based on a defined threshold. PVSS enhances security by enabling the public verification of share validity, deterring dishonest actions. Additionally, a Proof-of-Cooperation (PoC) consensus protocol is introduced within a consortium blockchain network to govern miner selection and block validation while fostering agent cooperation. However, this study focuses only on two trust-related attacks: bad-mouthing and on–off.

To assess context-dependent trust in dynamic IoT services, Bahutair et al. [10] propose a perspective-based trust management framework, which evaluates trust through three key perspectives: the Owner perspective (determined by social relationships and locality), the Device perspective (based on device reputation, which includes attributes like the manufacturer and operating system), and the Service perspective (focuses on service reliability, measuring performance and its impact on trust). These attributes are processed using a machine learning-based algorithm to build a trust model for crowdsourced IoT services. The authors highlight that in some IoT crowdsourcing applications—especially energy-sharing services—service reliability is a more critical factor than privacy. Additionally, social network-based trust models alone may be insufficient for evaluating trust between IoT service providers and consumers.

The CA model primarily relies on service reliability to assess the trustworthiness of service providers; thus, it can be widely used in IoT service crowdsourcing applications.

2.2. The Cold Start Problem

Trust and reputation models typically perform poorly when dealing with newcomer service providers. This challenge, known as the cold start problem, arises because service requesters have difficulty assessing the trustworthiness of newcomer service providers with whom they have no previous interactions but are now connected to. Stereotyping, first introduced by Meyerson et al. in [11], operates on the idea that agents with similar observable characteristics are likely to behave similarly. This approach helps improve trust assessments for newcomers or agents with no prior interaction history. More recently, the cold start problem has been addressed using machine learning, where trust models predict a newcomer’s trustworthiness [12]. Additionally, roles within virtual organizations and social relationships among entities can serve as sources of trust information [5], particularly when direct or indirect trust data are unavailable. Another approach involves assigning an initial trust value until the agent can gather direct experience. This value may represent the average performance or be inferred from interactions with other agents [4].

The CA algorithm applies this principle to mitigate the cold start problem. When a service provider receives a request to complete a specific task for a particular service requester for the first time, it establishes a connection and assigns an initial weight based on the average of existing weights for that task (from interactions with other service requesters). In essence, the CA algorithm allows the trustee to leverage prior experience from performing the same task for other trustors. If no prior knowledge is available, the algorithm sets the initial weight to a predetermined value, representing a baseline performance level.

2.3. Agent Mobility

A major concern with trust and reputation systems is their lack of interoperability across applications, known as the issue of the mobility of agents. When entities move between different applications, their trust and reputation data do not follow them; instead, this information remains isolated, requiring entities to rebuild their reputation in each new application. Enabling the transfer of trust and reputation data across applications remains an open challenge.

To address this issue, Jelenc [5] proposed a general framework to enable the exchange of trust and reputation information. This framework establishes a set of messages and a protocol that allows trust and reputation systems to request ratings, provide responses, and communicate errors. Additionally, to streamline message creation, they developed a grammar for generating queries from strings and introduced a procedure for parsing these query messages.

In [2], Jabeen et al. proposed a hybrid trust management framework which enables trust evaluation between entities using both centralized and distributed approaches, specifically addressing agent mobility. The network is divided into multiple sub-networks to improve management efficiency and scalability. Each sub-network contains a resource-rich fog node, known as the kingpin node, responsible for sharing service provider reputation scores upon request. For global reputation assessment, kingpin nodes aggregate reputation scores and forward them to the cloud. When a service provider moves to a different sub-network, it can present the ID of the kingpin from its previous sub-network. The new kingpin can then retrieve the service provider’s reputation from the cloud using this ID.

In the CA approach, however, a service provider retains all trust-related information concerning itself in the form of stored connections. This allows the service provider to directly access its own trust data and manage mobility by calculating its trustworthiness as a global reputation.

2.4. Dynamic Changes in Agents’ Behaviors

In dynamic environments, agents’ behavior can change rapidly, making it essential for consumer agents to detect these changes when using trust and reputation models to select reliable provider agents. Behavioral changes may stem from malicious intent, but they can also result from resource limitations, such as reduced battery power [2]. In MASs, dynamic behavior can be influenced by various factors, including seasonal variations, device malfunctions, malicious actions, network congestion, and more [4]. Some changes occur randomly and unpredictably, while others follow cyclical patterns. Additionally, group dynamics can contribute to behavioral changes, as relationships between agents evolve due to changing motivations or external influences, such as environmental changes.

An example of agents exhibiting continuously changing behavior is found in Fifth-Generation (5G) networks, where forwarding entities are responsible for relaying packets along a route. These entities may drop packets, leading to a reduced packet delivery rate. Their behavior is inherently dynamic, as they can switch between malicious and legitimate states at any time [13]. Reinforcement Learning (RL) allows legitimate forwarding entities to learn about the behavior of other potential forwarders. However, malicious entities can also exploit RL to strategically drop packets while avoiding detection, thereby manipulating the learning environment of legitimate entities. To address this issue, Ahmad et al. propose in [13] a hybrid trust model for secure routing in 5G networks. In this model, Q-learning enables distributed legitimate entities to evaluate the trustworthiness of neighboring forwarding entities. Additionally, using network-wide trust data and RL, a central authority can decide whether legitimate entities should continue or halt their learning process, depending on the proportion of legitimate to malicious entities in the network. However, the effectiveness of this model has not been experimentally validated.

To handle dynamic behavior, current trust and reputation models continue to utilize methods like sliding windows and forgetting factors [4]. A sliding window of size preserves only the most recent experiences, based on the assumption that these interactions best reflect an agent’s current behavior, while older records are discarded as they become less relevant. A forgetting factor gradually decreases the influence of past interactions over time, retaining all instances but assigning greater weight to more recent experiences. The trust model for pervasive computing applications proposed by Kolomvatsos et al. in [14] is an instance of the forgetting factor approach, as it progressively reduces the influence of past interactions through referral age in social trust calculations. It integrates both personal experience and reputation using fuzzy logic (FL) principles. The model consists of three subsystems, with two of the subsystems responsible for evaluating an entity’s trust level based on individual experiences and referrals. To address the dynamic nature of trust, the calculation of social trust depends on two key factors: the referral age and the referrer reputation. Each referral is timestamped, and its influence on social trust decreases over time. Once it surpasses a predefined expiration point, it is no longer considered. The credibility of the referrer determines how much weight their referral carries in the final trust calculation. The system employs a central authority to manage storage and access to referrals. However, this introduces a single point of failure, which can be a limitation. After determining social and individual trust, each intelligent agent uses a weighted sum method to compute the final trust value. The third FL subsystem is responsible for determining the weight assigned to social trust, using as inputs the total number of social referrals and the total number of past individual interactions.

Assessing trust in MASs is particularly challenging due to the dynamic nature of agent behavior, which can change at varying speeds and times. This variability makes traditional approaches, such as forgetting old data at a constant rate and sliding windows, ineffective [4]. To address this issue, Player and Griffiths in [4] propose RaPTaR, a framework that sits on top of existing trust and reputation models to detect and adapt to behavior changes within agent groups. RaPTaR enhances trust algorithms by supplying past experience data that have been statistically evaluated to reflect an agent’s current behavior. The system identifies behavioral shifts by analyzing the outcome patterns of agent groups using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) statistical test. Additionally, it records transitions between behavior changes to recognize recurring patterns, which can be leveraged for future predictions. By exploiting repetitive behavior, RaPTaR improves trust assessment in dynamic environments. The experimental results indicate that while RaPTaR effectively detects and responds to random behavioral changes, its accuracy remains limited and can be improved.

Reputation-based trust models are widely used in distributed networks, but they encounter two major challenges: the transmitted reputation may not accurately reflect an entity’s current trustworthiness, and over-reliance on reputation makes the system vulnerable to collusion, where malicious entities conspire to fabricate trust values. One possible solution is trust prediction, which estimates an entity’s current trustworthiness based on past interactions, behavioral history, and other objective factors. Traditional time-based prediction methods fall into two categories. One is the complete arithmetic mean, which computes the average of all past data to predict the next trust value. The other method is mean shift, which prioritizes recent data, ignoring long-term history. A more refined approach is exponential smoothing, which balances both methods by incorporating past data while assigning diminishing weight as time elapses. However, pure exponential smoothing struggles with highly volatile data, especially in cases where a service provider is hijacked by adversaries, causing an abrupt shift from high trust to deception. In such situations, exponential smoothing alone can lead to significant deviations in trust estimation. To address this issue, Wang et al. in [15] propose a dynamic trust model that integrates direct and indirect trust computation with trust prediction. Their approach first applies exponential smoothing to compute a trend curve and then utilizes a Markov chain model to adjust for fluctuations, improving prediction accuracy. This is a refined method for handling abrupt behavioral shifts, such as when an entity transitions from trustworthy to malicious.

In the proposed CA algorithm, after delivering a service, a service provider reassesses its performance. If the performance falls below a predefined threshold, the service provider categorizes itself as a bad provider. This ensures that each provider continuously maintains an updated assessment of its capabilities, enabling the prompt detection of performance declines that could negatively impact consumers.

2.5. Assessing Trust from the Trustee’s Perspective

Similarly to the CA approach, several studies [16,17] place the responsibility on service providers to determine whether they can complete a requested task and assess the potential benefits before deciding whether to accept or decline service requests. Latif in [16] introduces ConTrust, a context-aware trust model for the Social Internet of Things (SIoT), designed to help service consumers select reliable providers for task assignments. In this approach, the requester broadcasts the task, specifying its requirements, and providers evaluate their ability to fulfill the request along with the potential benefits. If a provider is willing to take on the task, it responds to the requester, who then assesses the trustworthiness of the candidates and selects a specific provider. Trustworthiness in ConTrust is measured using a weighted sum of three factors: the service provider’s capability, commitment, and job satisfaction feedback. The CA model shares similarities with ConTrust in that it is also context-aware, as trust evaluation considers the task type and requirements within the specific environment where the service is provided. Additionally, the consumer broadcasts a request, and each provider evaluates its own capability to complete the task. However, the CA model differs in a fundamental way: service consumers do not select providers. Instead, trust assessment is handled by the provider itself, based on consumer feedback.

A key issue with trust and reputation systems that rely solely on distributed infrastructures is that each entity only retains information about a small fraction of the entire network. As a result, knowledge about the number of available service providers is limited to local information, reducing the likelihood of selecting highly trustworthy providers [2]. This limitation does not apply to the CA approach. In CA, the request message is broadcasted to all service providers within the consumer agent’s vicinity. However, unreliable providers, who are aware of their own limitations, will opt out of executing tasks they are not capable of handling. Consequently, this self-selection process increases the probability of obtaining service from highly trustworthy service providers.

When a service requester no longer has control over selecting service providers, and instead, the service providers themselves decide whether to offer a service, a mechanism is needed to incentivize honest service provision. Additionally, most trust and reputation models assume that service requesters act honestly, which is often unrealistic in agent-based systems. To address these issues, Alam et al. proposed in [17] a blockchain-based, two-way reputation system for the SIoT, incorporating a penalty mechanism for both dishonest service providers and service requesters. This approach evaluates a service provider’s local trust, global trust, and reputation by considering both social trust and Quality of Service (QoS) factors, such as availability, accuracy, Cruciality, Responsiveness, and cooperation. After receiving a service, service requesters must provide feedback by rating the service providers. However, relying on a single cumulative rating has drawbacks: (i) it does not clarify the evaluation criteria used for assessing service providers; (ii) dishonest service requesters can intentionally lower a service provider’s rating, even if the service is good; and (iii) inexperienced service requesters may struggle to provide meaningful feedback. To overcome these challenges, the authors propose a “two-stage parameterized feedback” system. Tlocal (local trust) is calculated in two phases: pre-service avail and post-service avail. Comparing Tlocal and Tglobal (global trust) helps detect suspicious or dishonest service requesters, who are then classified into three categories: suspicious, temporarily banned (can only request certain services), and permanently banned (prohibited from requesting any service). For service providers, a penalty mechanism using a fee charge system imposes monetary losses on dishonest providers. Service providers are categorized into three status lists based on their reputation: the white list (highest service fees and selection priority), gray list (moderate reputation, lower fees), and black list (least trustworthy, low selection probability). Each feedback update adjusts a service provider’s trust and reputation value, and service providers can accept or decline service requests. The approach also allows service requesters to choose service providers based on cost preference—for example, a service requester aiming to reduce expenses may prefer a service provider from the gray list rather than the white list. The experimental results show that this method is resilient to various trust-related attacks, including on–off, Discriminatory, opportunistic service, Selective Behavior, bad-mouthing, and ballot stuffing attacks. However, this study does not address the Whitewashing Attack. The proposed mechanisms offer valuable insights that could serve as a foundation for adapting the CA approach to more realistic environments where dishonest behavior is prevalent.

2.6. Mechanisms for Promoting Honest Behavior

Besides [17], several other studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24] propose mechanisms aimed at promoting honest behavior among agents during their interactions. These mechanisms serve as a basis for formulating a customized approach within the CA framework to counter various trust-related attacks, which we explore further in Section 8.

A key requirement in large, dynamic, and heterogeneous networks—where node participation is constantly changing—is a mechanism for establishing a secure, authenticated channel between any two participating nodes to exchange sensitive information. Fragkos et al. present in [18] a Bayesian trust model that probabilistically estimates node trust scores in an IoT environment, even in the absence of complete information. The authors propose a contract-theoretic incentive mechanism to build trust between devices in an ad hoc manner by leveraging locally adjacent nodes. Each IoT node independently stores and advertises its absolute trust score. The proposed effort–reward model motivates selected nodes to accurately report their trust scores and actively contribute to the authentication process, with rewards aligned to their actual trust levels. Unlike traditional blockchain-based solutions, this approach does not depend on cryptographic primitives or a central authority, and the final consensus is localized rather than being a universally shared state across all nodes in the system.

To enhance content trust, Pan et al. introduced in [19] TrustCoin, a smart trust evaluation framework for Information-Centric Networks (ICNs) in Beyond Fifth-Generation (B5G) networks, leveraging consortium blockchain technology. In this scheme, each TrustCoin user—whether a publisher/producer or a subscriber/consumer—is assigned credit quotas (i.e., coins) that reflect its reputation and serve as a measure of trust. A higher coin balance indicates greater credibility. Users must first register to obtain a legal identity and initial credit coins before they can request to publish content or report potentially malicious data. When content is published, a checking server verifies the publisher’s credit balance on the blockchain to ensure it meets a predefined threshold. For content sharing, edge nodes authenticate user identities, while Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) is employed to assess content credibility. TrustCoin incorporates an incentive mechanism that encourages users to proactively publish trustworthy content. The system updates the credit coins of publishers and subscribers based on the content credibility determined by DRL-driven evaluations. Higher credibility results in rewards for publishers, reinforcing trustworthy behavior, while subscribers may face penalties. Conversely, if a publisher shares low-credibility content, they incur a penalty, while the subscriber is rewarded for correctly identifying and reporting it.

In IoT networks, connected nodes may exhibit reluctance to forward packets in order to conserve resources such as battery life, energy, bandwidth, and memory. To address this issue, Muhammad et al. propose in [20] a trust-based approach called HBST, which fosters cooperation by forming a credible community based on honesty. Unlike conventional methods that permanently remove selfish nodes from the network, HBST instead isolates them in a separate domain, preventing interactions with honest nodes while offering then an opportunity to improve their behavior and re-enter the network. The proposed model consists of two phases. In the first phase, credible nodes—those with a sufficient community reputation—are selected from the main network to form a “credible community”. A node’s reputation is determined by its honesty level, assessed using metrics such as interaction frequency, credibility, and community engagement. In the second phase, a social selection process appoints two leaders from this credible community based on factors such as seniority, cooperative behavior, and energy levels. The node with the highest reputation weight is designated as the Selected Community Head (SCH), while the second highest becomes the Selected Monitoring Head (SMH). These leaders play key roles in mitigating selfish behavior: the SCH is responsible for encouraging selfish nodes to participate and can impose penalties on reported offenders, while the SMH monitors node behavior and flags selfish activity to the SCH. Selfish nodes are initially isolated in a separate domain, barring communication with the rest of the network. If a selfish node repeatedly fails to improve, it may face expulsion—a strict penalty. However, unlike permanent removal, HBST allows selfish nodes to rejoin the main community by improving their honesty level beyond a predefined threshold. In cases of persistent selfish behavior, a warning message is broadcasted to neighboring communities, instructing them to cease communication with the offending node as a severe consequence.

In the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), numerous smart health monitoring devices communicate and transmit data for analysis and real-time decision-making. Secure communication among these devices is essential to ensure timely and accurate patient data processing. However, establishing reliable communication in large-scale IoMT networks is both time-intensive and energy-demanding. To address this challenge, Ali et al. propose in [21] BFT-IoMT, a distributed, energy-efficient, fuzzy logic-based, blockchain-enabled, and fog-assisted trust management framework. This framework employs a cluster-based trust evaluation mechanism to detect and isolate Sybil nodes. The process begins with a topology lookup module, which identifies network topology whenever an IoMT device joins or leaves the network. Next, clusters and Cluster Heads (CHs) are formed, with CHs registered on the blockchain. Each IoMT node’s trust-related parameters are collected and analyzed by a trust calculator module. The computed trust scores are then stored on the blockchain. If a node’s trust score falls below a predefined threshold, it is flagged as a malicious (Sybil) node and isolated from the network. The final decision on whether a node is malicious or benign is then broadcasted across the IoMT system. The fog-assisted trust framework is designed to enhance network throughput while reducing latency, energy consumption, and communication overhead. The use of fuzzy logic—which efficiently handles ambiguous and uncertain data, common in healthcare applications—improves the computational power and effectiveness of the decentralized trust management system. However, the proposed protocol assumes that CHs are inherently trusted nodes, which is an impractical assumption in most IoT environments.

Kouicem et al. in [22] aim to develop a fully distributed and scalable trust management protocol, enabling IoT devices to assess the trustworthiness of any service provider on the Internet without relying on pre-trusted entities. They introduce a decentralized trust management protocol for the Internet of Everything (IoE), leveraging blockchain technology and the fog computing paradigm. In this system, powerful fog nodes maintain the blockchain, relieving lightweight IoT devices of the burden of trust data storage and intensive computations. This approach optimizes resource usage, bandwidth efficiency, and scalability. By utilizing blockchain, the protocol provides a global perspective on the trustworthiness of each service provider within the network. A key feature of the proposed solution is its fine-grained trust evaluation mechanism—IoT devices receive recommendations about service providers not only based on the requested service but also according to a set of specific requirements that the providers can fulfill. Additionally, blockchain technology enhances the protocol’s adaptability to high-mobility scenarios. Through experiments, the authors demonstrate the resilience and robustness of their approach against various malicious attacks, including self-promotion, bad-mouthing, ballot stuffing, opportunistic service, and on–off attacks. They further validate their results through a theoretical analysis of trust value convergence under different attack scenarios. To mitigate the impact of cooperative attacks, the authors propose an online countermeasure algorithm that analyzes the recommendation history recorded on the blockchain. This real-time algorithm is executed whenever fog nodes compute trust recommendations. Each fog node aggregates all recommendations for a particular IoT service provider and evaluates the minimum and maximum recommendation values. If the difference exceeds a predefined threshold, the provider is flagged as potentially engaging in a cooperative attack, and its recommendations are disregarded. The proposed protocol takes advantage of blockchain technology’s strengths but also inherits its drawbacks. One major limitation is high resource consumption, as miners require substantial computing power to achieve consensus.

Ouechtati et al. introduced in [23] a fuzzy logic-based model to filter dishonest recommendations in the SIoT. The model evaluates recommendations based on factors such as recommendation values, the sender’s location coordinates, the time of submission, and social relationships. The proposed approach detects Sybil attacks by applying fuzzy classification to received recommendations, considering their Cosine Distance and temporal proximity. The underlying assumption is that recommendations that are similar in content, closely timed, and sent from nearby locations are likely generated by the same attacker conducting a Sybil attack. Once Sybil recommendations are identified, the remaining recommendations are classified based on the existing social relationships between the senders and the recommended object. These relationships include the Ownership Object Relationship (OOR), Co-Location Relationship (C-LOR), Co-Work Relationship (C-WOR), and Social Object Relationship (SOR). To further assess recommendation reliability, the model evaluates Internal Similarity (IS), which measures how closely each recommendation aligns with the median value of trusted witness objects within the same community. Simultaneously, it calculates the Degree of Social Relationship (DSR), which quantifies the strength of connections between the senders and the recommended object. The DSR is determined by the number of past transactions between objects, with greater interaction frequency indicating higher trustworthiness. Additionally, recommendations from specific communities, such as the OOR, carry more weight in the evaluation. The IS and DSR metrics play a crucial role in detecting good-mouthing and bad-mouthing attacks. If both the IS and DSR values are very low, the recommendation is deemed unreliable, suggesting that the sender may be attempting to manipulate trust through either a good-mouthing or bad-mouthing attack.

In Vehicular Edge Computing (VEC), edge servers may request data from Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) to support intelligent applications such as Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs). However, economic concerns, including power consumption, create challenges in integrating data sharing within the dynamic VEC network. A promising alternative is shifting form data sharing to data trading, which incentivizes AVs to exchange their data for rewards. However, integrating data trading into edge servers introduces additional concerns related to security, privacy, and trust. To address these challenges, Mianji et al. propose in [24] a novel reputation management system for data trading that utilizes DRL. Their approach, called the Dynamic Selection of Trusted Sellers using Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DSTSDPG), dynamically adjusts a credibility score threshold to identify the most reliable data sellers among the available AVs. The proposed system follows a hierarchical network architecture consisting of three levels: the Vehicle level (Autonomous Vehicles), Edge level (Roadside Units (RSUs) or edge servers), and Cloud level (a central cloud server). Within each cluster, a designated VEC server retrieves credibility values from the cloud and uses multiple parameters to calculate an AV’s credibility score using the DRL-based approach. Based on this score, the edge server selects the most trustworthy AV for data transactions. The computed scores are uploaded to the cloud and can be shared with other edge servers when an AV moves to a different cluster addressing the issue of mobility. However, since this method relies on a centralized architecture involving both cloud and edge servers, it inherits typical limitations such as the risk of a single point of failure. For credibility score calculation, the proposed approach considers three key factors: historical reputation (past interactions influence trustworthiness), familiarity (higher values indicate that an edge server has more prior knowledge of an AV), and freshness (recent interactions are weighted more heavily). The proposed trust and reputation model is built on subjective logic, and the credibility score is derived from a weighted sum of familiarity and freshness. However, the authors do not clarify how the weights are determined.

Existing trustworthiness models can only detect a subset of known attacks, but none can defend against all types [25]. This is because attack patterns are highly diverse, with malicious nodes strategically exploiting weaknesses in trust algorithms to evade detection. To address this challenge, Marche and Nitti examine in [25] all trust-related attacks documented in the literature that can impact IoT systems. They propose a decentralized trust management model that leverages a machine learning algorithm and introduces three novel parameters: goodness, usefulness, and perseverance scores. These scores enable the model to continuously learn, adapt, and effectively identify and counteract a wide range of malicious attacks. Therefore, developing algorithms capable of detecting diverse malicious activity patterns is crucial [26]. To this end, in Section 8, we further discuss how various mechanisms can be integrated into the CA approach to enhance its resilience against existing trust-related attacks.

3. Background

In this section, we begin by outlining the key features of FIRE and CA, the two trust models evaluated in our simulation experiments, explaining the rationale behind selecting FIRE as a reference model for comparison, followed by an overview of the previous version of the CA algorithm, which incorporates a mechanism for handling dynamic trustee profiles.

3.1. FIRE

Huynh et al. introduced the FIRE model in [27], naming it after “fides” (Latin for “trust”) and “reputation”. We selected FIRE as a reference model for comparison with CA because it is a well-established trust and reputation model for open MASs that, like CA, adopts a decentralized approach. Additionally, FIRE represents the traditional trust management approach, where trustors select trustees, providing a contrast to the CA model, where trustees are not chosen by trustors. It consists of four key modules:

- Interaction Trust (IT): Evaluates an agent’s trustworthiness based on its past interactions with the evaluator.

- Witness Reputation (WR): Assesses the target’s agent’s trustworthiness using feedback from witnesses—other agents that have previously interacted with it.

- Role-based Trust (RT): Determines trustworthiness based on role-based relationships with the target agent, incorporating domain knowledge such as norms and regulations.

- Certified Reputation (CR): Relies on third-party references stored by the target agent, which can be accessed on demand to assess trustworthiness.

IT is the most reliable trust information source, as it directly reflects the evaluator’s satisfaction. However, if the evaluator has no prior interactions with the target agent, FIRE cannot utilize the IT module and must rely on the other three modules, primarily WR. However, when a large number of witnesses leave the system, WR becomes ineffective, forcing FIRE to depend mainly on the CR module for trust assessments. Yet, CR is not highly reliable, as trustees may selectively store only favorable third-party references, leading to the overestimation of their performance.

3.2. CA Model

CA is a biologically inspired computational trust model. It is inspired by biology concepts, particularly synaptic plasticity in the human brain and the formation of assemblies of neurons. In our previous work [28], we provided a detailed explanation of synaptic plasticity and how it is applied in our model.

An MAS is used to represent a social environment where agents communicate and collaborate to execute tasks. In [28], we formally defined the key concepts necessary for describing our model, but here, we summarize the most essential ones. A trustor is an agent that defines a task and broadcasts a request message containing all relevant details, including the following: (i) the task category (type of work to be performed) and (ii) a set of requirements, as specified by the trustor.

In the CA approach, the trustee, rather than the trustor, decides whether to engage in an interaction and perform a given task. When a trustee receives a request message, it establishes and maintains a connection weight , representing the strength of this connection. This weight reflects the probability of successful task completion and is updated by the trustee, based on the performance feedback provided by the trustor. If the trustee successfully completes the task, the weight is increased according to the following:

If the trustee fails, the weight decreases as follows:

where and are positive parameters controlling the rate of increase and decrease, respectively.

The trustee decides whether to accept a task request by comparing the connection weight with a predefined . If the weight meets or exceeds this threshold , the trustee proceeds with task execution.

Table 1 summarizes the main differences between FIRE and CA across several core dimensions of trust modeling, including trust evaluation methods, trust update mechanisms, and trust storage approaches.

Table 1.

Comparison between FIRE and CA trust models.

3.3. The CA Algorithm Used to Handle Dynamic Trustee Profiles

In this subsection, we present the original version of the CA algorithm, as introduced in [7], including a brief description and the pseudocode, for the sake of completeness and to facilitate comparison with the updated version, presented in Section 4.2 of this work.

When a trustor identifies a new task to be executed by a trustee, it broadcasts a request message containing relevant task details (lines 2–3). Upon receiving this request, each potential trustee stores it in a list and establishes a new connection with the requesting trustor if one does not already exist (lines 4–12). Lines 6–11 address the cold start problem, which arises when a trustee lacks prior experience with a specific task and thus cannot assess its own capability to complete it. In the version shown in Algorithm 1, the trustee leverages prior knowledge gained from performing the same task for other trustors. Specifically, line 7 checks whether agent has previously interacted with other agents (denoted by ) for the same task. If such similar connections exist, the agent will use the average weight of those connections to initialize the new one. If no prior experience exists (i.e., the trustee has never performed the task for any trustor), the connection weight is initialized to a default value of 0.5 (line 10), as was performed in the original algorithm proposed in [28].

At each time step, each trustee reviews the tasks stored in that list and attempts to execute the task with the highest connection weight, provided that the task remains available and the weight does not exceed a predefined threshold (lines 13–21). Lines 14–16 are part of the agent’s decision-making process before attempting to perform a task. They serve as a sequence of filters that ensure the task is worth pursuing, feasible, and assigned with sufficient trust. The check in line 14—“task is not visible or not done yet”—captures scenarios where the agent must move within a range to personally verify the task’s completion. In some cases, other agents might provide that information. Line 15 ensures the task is physically accessible and not already being performed by another agent or that the agent has the resources to perform it. Finally, line 16 introduces a trust-based filter. Even if a task is available and the agent is able to approach and undertake it, the agent proceeds only if the trust level with the task requester for the specific task meets or exceeds a predefined threshold. This promotes cautious behavior by ensuring that the agent only commits to tasks where sufficient trust exists in the cooperation.

If task execution is successful, the trustee increases the connection weight; otherwise, it decreases it (lines 22–26). This CA algorithm also accounts for dynamic trustee profiles as follows (lines 27–31). If a connection’s weight falls below the threshold, the trustee interprets this as an indication of its incapability to complete the task successfully and stops attempting it to save resources. However, if the trustee performs well on an easier task, it may infer that it has likely learned how to execute more complex tasks within the same category. In such cases, it increases the connection weight of those previously failed tasks to the threshold value, allowing itself an opportunity to attempt them again in the future.

To improve the understanding of Algorithm 1, Table 2 summarizes the main symbols and their meanings.

Table 2.

Notation table.

| Algorithm 1: CA v2, for agent |

| 1: while True do # --- broadcast a request message when a new task is perceived --- 2: when perceived a new task = (c, r) 3: broadcast message m = (request, i, task) # --- Receive/store a request message and initialize a new connection--- 4: when received a new message m = (request, j, task) 5: add m to message list M 6: if no existing connection co = (i, j, _, task) then 7: if there are similar connections co’ = (i,~j,_,task) from i to other agents for the same task then 8: create co = (i, j, avg_w, task), where avg_w = average of all weights for (i, ~j, _, task) 9: else 10: create co = (i, j, 0.5, task) # initialize weight to default initial trust 0.5 11: end if 12: end if # --- Select and Attempt task --- 13: select m = (request, j, task) from M such that co = (i, j, w, task) has the highest weight among all (i, k, w’, task) 14: if task is not visible or not done yet then 15: if canAccessAndUndertake(task) then 16: if w ≥ Threshold then 17: (result, performance) ← performTask(task) 18: end if 19: end if 20: end if 21: delete m from M # --- Update connection weight based on result --- 22: if result = success then 23: strengthen co using Equation (1) 24: else 25: weaken co using Equation (2) 26: end if # --- Dynamic profile update --- 27: for all failed connections co’ = (i, j, w’, task’) where w’ < Threshold and task’ = (c, r’) with r’ > r do 28: if performance ≥ minSuccessfulPerformance(task’) then 29: w’ ← Threshold # Give another chance on harder tasks 30: end if 31: end for 32: end while |

4. Enhancing Performance by Avoiding Unwarranted Task Executions

In this section, we begin with a semi-formal analysis of the CA algorithm to identify potential modifications that could enhance its performance. Following this, we introduce an improved CA algorithm designed to detect and prevent unwarranted task executions.

4.1. A Semi-Formal Analysis of the CA Algorithm to Identify and Avoid Unwarranted Task Executions

To identify potential improvements to the performance of the CA algorithm, we conducted the following semi-formal analysis. While this analysis incorporates formal elements such as assumptions, definitions, propositions, and a proof by induction, it does not constitute a strictly formal analysis in the traditional mathematical or computer science sense. Instead, it represents a blend of formal reasoning and empirical evaluation for the following reasons:

- Although induction is used to support Proposition 1, many conclusions rely more on empirical observation than on rigorous formal logic;

- The conclusions are drawn from specific experimental conditions (e.g., Threshold = 0.5, a = β = 0.1), whereas a purely formal analysis would typically strive to derive results that hold regardless of particular parameter values;

- Several conclusions are derived from example scenarios rather than universally valid logical proofs.

In our testbed, each consumer requesting the service at a certain performance level waits for a period equal to WT for the service to be provided by a provider in its operational range (nearby provider). If the requested , where is not performed, either because there are no nearby providers or none of the nearby providers are willing to perform the task, then the consumer requests the service at the next lower performance level, assuming that any consumer can manage with a lower-quality service.

Assumption 1.

WT is large enough so that if there is a capable provider in the operational range of the consumer, then the task will be successfully executed.

Assumption 2.

The reason why a nearby provider may not be willing to perform a task is only because the weight of the relevant connection is less than the threshold vale. We assume that there are no other reasons, i.e., the providers are not selfish or malicious. In other words, we assume that the providers are always honest and comply with the implemented protocols, having no intention to harm the trustors.

Since every rational consumer aims to maximize its profit, the sequence of tasks that it may request until a provider is found to provide the service is as follows: , , , , and . In Table 3, the requirements of each task are specified.

Table 3.

Explanation of requirements.

Definition 1.

Given that is a consumer requesting the successful execution of , is a provider in the operational range of receiving a request from for the execution of , and does not yet have a connection for and , we define as having learned its incapability to perform (meaning that it cannot always perform successfully) when it initializes the weight of a new connection for and to a value smaller than the threshold value, which will result in not executing for .

Since only bad and intermittent providers have negative (causing damage to the consumers) performances, we analyze how bad providers learn their own capabilities in each of the five tasks, aiming to identify ways to reduce task executions with negative performances and thus improve the performance of the CA algorithm.

We consider a system of four consumers, , , , and , and only one provider: the bad provider . Each consumer has in its operational range the provider . The provider has no knowledge of its capabilities in performing tasks, meaning that it has not formed any connections yet.

Phase A: Provider learns its incapability in performing .

Assume that requests the execution of broadcasting the message . According to the CA algorithm, when receives message , it will create the connection , initializing its weight to the value 0.5. Since the condition is satisfied, will perform , but it will fail because its performance range is in , and requires a performance equal to 10. After it fails, will decrease the weight of to the value , by using equation , where in our experiments.

Now, let require the execution of by sending the message . When receives the message and because it already has the connection , it will create the connection , initializing its weight to the average of the weights of the connections it has with other consumers for . In this case, , where denotes the weight of connection . Because the weight of is less than the threshold value, will decide not to perform for consumer .

Assumption 3.

For simplicity, we assume that will not change its ability to provide so that the weights of all connections will remain constant over time.

Now, we can prove by induction the following proposition.

Proposition 1.

Given Assumption 3, every new connection that will create for will be initialized to the average of the weights of the connections it has already created for , which will remain constant and equal to 0.45.

The proof is provided in Appendix A. By Proposition 1 and Definition 1, it follows that , in a single trial, has learned that it cannot successfully perform . We can generalize every bad provider to the following conclusion.

Conclusion 1.

Given our experimental conditions (i.e., Threshold = 0.5, α = β = 0.1), every bad provider needs only one trial to learn that it cannot successfully perform task1.

Phase B: Provider learns its incapability in performing .

Following the same analysis as in Phase A, we can conclude as follows.

Conclusion 2.

Given our experimental conditions (i.e., Threshold = 0.5, α = β = 0.1), every bad provider needs only one trial to learn that it cannot successfully perform task2.

Phase C: Provider learns its incapability in performing .

Assume that requests the execution of broadcasting the message . When receives message , it will create the connection , initializing its weight to the value 0.5. Since the condition is satisfied, will perform . Due to its performance range in and the task’s requirement that performance must be bigger or equal to zero in order to be successful, has a small probability of having a performance equal to zero and thus a successful execution of .

So, consider a scenario where the performance of on on its first trial is 0. After it succeeds, it will increase the weight of to the value by using equation , where in our experiments. Now, let request the execution of broadcasting the message . When receives message and because it already has the connection , it will calculate the average weight of existing connections as . Then, it will create the connection , initializing its weight to the average just calculated. Since the condition is satisfied, will execute for . Suppose that fails this time and decreases the weight of to the value . The scenario continues with two consecutive failed executions of for consumers and . In Table 4, we can see the average weights of the connections after each task execution.

Table 4.

Evolution of average connection weights after each execution of for consumer to .

In the scenario above, needed three consecutive failed executions after the successful first execution of to learn (according to Definition 1) that it is not capable of always performing this task in a successful way, because the average weight of its connections for is now less than the threshold value. This leads us to the following more general conclusion.

Conclusion 3.

The successful execution of on the first trial of a bad provider requires a number of consecutive failed executions to learn that it cannot always execute this task successfully.

Phase D: Provider learns its incapability in performing .

Since has a performance range in and requires a to be successful, has a good probability of being successful in its first trial of . If we repeat the analysis of phase C, we will be led to the following conclusion.

Conclusion 4.

The successful execution of on the first trial of a bad provider requires a number of consecutive failed executions to learn that it cannot always execute this task successfully.

Phase E: Provider learns its capability in performing .

Since has a performance range in and is successfully executed if , will always execute this task successfully.

Conclusion 5.

A bad provider will always execute

Ideally, we would prefer that a bad provider not provide the service at all, because its poor performance harms the consumer, but providing the service at least once is required to assess the provider’s capabilities. However, the previous analysis demonstrates that the CA algorithm allows the bad provider to provide the service multiple times. Despite its negative performance on , performed poorly with a negative performance in phase B as well. A more intelligent agent could consider its negative performance from the first time and decide not to execute . Furthermore, in both phase C and phase D, the successful first execution of the task requires a series of consecutive failed executions, which we would like to avoid.

To this end, in the following section, we propose an improved CA algorithm designed to detect bad providers early on and prevent them from damaging the consumers with their negative performances.

4.2. The Proposed CA Algorithm for the Early Detection of Bad Providers

In the proposed algorithm for the early detection of bad providers, each provider maintains a task-specific self-assessment mechanism through the , which is initialized with a default value of false for each task (line 1). This means that when a provider is created, it implicitly assumes it is not bad for any task it has not yet performed—there is no need to explicitly initialize entries for unknown tasks. After performing a task, the provider re-evaluates its performance (lines 25–29). If the performance is less than or equal to zero, it considers itself a bad provider for that specific task by setting ; otherwise, it maintains or resets the value to false. This enables rapid, task-specific reassessment, allowing the provider to dynamically adapt its trustworthiness profile based on its most recent outcomes.

In lines 7–14 of the proposed algorithm, this self-assessment is used to initialize the trust weight of a new connection. If the provider believes it is bad and the task requires a performance level of PERFECT, GOOD, or OK, the connection is initialized with a trust weight of 0.45 (line 9). Otherwise, the algorithm falls back to the original initialization logic (lines 10–13), which either averages existing weights from similar connections or sets a default trust of 0.5, as described in Section 3.3 for the previous version algorithm1.

In lines 15–19, if the connection already exists, the provider re-evaluates whether it should adjust the weight based on its current self-assessment. If the provider considers itself bad and the task requires a performance level ≥ 0 (i.e., PERFECT, GOOD, or OK), it lowers the weight of the existing connection to 0.45, reinforcing a cautious stance toward engaging in the task.

This modification enhances the context-awareness and reliability of the decision-making process by ensuring that each provider is consistently informed by its own recent experience when evaluating and responding to task requests.

Core functionalities from Algorithm 1—such as broadcasting task requests, handling incoming messages, task selection and execution, connection weight updates, and dynamic profile adjustments—are preserved without modification in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: CA v3, for agent |

| # --- Initialize task-specific self-assessment memory --- 1: define i.bad_tasks as a map with default value false # assumes good unless proven otherwise 2: while True do # --- Broadcast a request message when a new task is perceived --- 3: when perceived a new task = (c, r) 4: broadcast message m = (request, i, task) # --- Receive/store a request message and initialize a new connection --- 5: when received a new message m = (request, j, task) 6: add m to message list M # --- Initialize a new connection --- 7: if no existing connection co = (i, j, _, task) then 8: if i.bad_tasks[task] = true and task.performance_level ∈ {PERFECT, GOOD, OK} then 9: create co = (i, j, 0.45, task) # cautious trust level for task-specific bad assessment 10: else if there are similar connections co’ = (i, ~j, _, task) from i to other agents for the same task then 11: create co = (i, j, avg_w, task), where avg_w = average of all weights for (i, ~j, _, task) 12: else 13: create co = (i, j, 0.5, task) # initialize to default trust 14: end if 15: else #if connection co = (i, j, _, task) exists # --- modify an existing connection if certain conditions hold--- 16: if i.bad_tasks[task] = true and task.performance_level ∈ {PERFECT, GOOD, OK} then 17: modify co = (i, j, 0.45, task) 18: end if 19: end if # --- Select and Attempt task --- 20: select m = (request, j, task) from M such that co = (i, j, w, task) has the highest weight among all (i, k, w’, task) 21: if task is not visible or not done yet then 22: if canAccessAndUndertake(task) then 23: if w ≥ Threshold then 24: (result, performance) ← performTask(task) # --- Re-evaluate task-specific self-assessment based on latest performance --- 25: if performance ≤ 0 then 26: i.bad_tasks[task] ← true 27: else 28: i.bad_tasks[task] ← false 29: end if 30: end if 31: end if 32: end if 33: delete m from M # --- Update connection weight based on result --- 34: if result = success then 35: strengthen co using Equation (1) 36: else 37: weaken co using Equation (2) 38: end if # --- Dynamic profile update --- 39: for all failed connections co’ = (i, j, w’, task’) where w’ < Threshold and task’ = (c, r’) with r’ > r do 40: if performance ≥ minSuccessfulPerformance(task’) then 41: w’ ← Threshold # Give another chance on harder tasks 42: end if 43: end for 44: end while |

5. Experimental Setup and Methodology

5.1. The Testbed

To test the performance of the revised algorithm, we performed an extensive simulation-based experimentation on a testbed based on the one described in [27].

The environment of the testbed consists of agents that either provide services (referred to as providers or trustees) or use these services (referred to as service requesters, consumers, or trustors). For simplicity, we assume all providers offer the same service, i.e., there exists only one type of task. The agents are randomly distributed within a spherical world with a radius of 1.0. The agent’s radius of operation ( represents its capacity to interact with others (e.g., available bandwidth), and it is uniform across all agents, set to half the radius of the spherical world. Each agent has acquaintances, which are other agents located within its operational radius.

Provider performance varies and determines the utility gain (UG) for consumers during interactions. There are four types of providers, good, ordinary, intermittent, and bad, as defined in [27]. Except for intermittent providers, each type has a mean performance level , with the actual performance following a normal distribution around this mean. Table 5 shows the values of and the associated standard deviation for each provider type. Intermittent providers perform randomly within the range . The radius of operation of a provider also represents the range within which it can offer services without a loss of quality. If a consumer is outside this range, the service quality deteriorates linearly based on the distance, but the final performance remains within and corresponds to the utility the consumer gains from the interaction.

Table 5.

Profiles of provider agents (performance constants defined in Table 6).

The simulations in the testbed are conducted in rounds. As in real life, consumers do not require services in every round. When a consumer is created, its probability of requiring a service () is selected randomly. There are no limitations on the number of agents that can participate in a round. If a consumer needs a service in a round, the request is always made within that round. The round number marks the time for any event.

Consumers fall into one of three categories: (a) those using FIRE, (b) those using the old version of the CA algorithm, or (c) those using the new version of the CA algorithm. If a consumer requires a service in a round, it locates all nearby providers. FIRE consumers select a provider following the four-step process outlined in [27]. After choosing a provider, they use the service, gain utility, and rate the service based on the UG they received. This rating is recorded for future trust assessments. The provider is also informed of the rating and may keep it for future interactions.

CA consumers do not choose a provider. Instead, they send a request message to all nearby providers specifying the required service quality. Table 6 lists five performance levels that define the possible service qualities. CA consumers first request service at the highest quality (PERFECT). After a predetermined waiting time (WT), any CA consumer still unserved sends a new request for a lower-performance-level service (GOOD). This process continues until the lowest service level is reached or all consumers are served. When a provider receives a request, it stores it locally and applies the CA algorithm (CA_OLD or CA_NEW, depending on the consumer group it belongs to). WT is a parameter that defines the maximum time allowed for all requested services in a round to be provided.

Table 6.

Performance level constants.

We assume that any consumer can manage with a lower-quality service. This assumption does not raise an issue of unfair comparison between FIRE and CA, since it also applies to consumers using FIRE. For instance, they may end up selecting a provider—potentially the only available option—whose service ultimately delivers the lowest performance level (WORST).

Agents can enter and exit the open MAS at any time, which is simulated by replacing a number of randomly selected agents with new ones. The number of agents added or removed after each round varies but must remain within certain percentage limits of the total population. The parameters and define these population change limits for consumers and providers, respectively. The characteristics of new agents are randomly determined, but the proportions of provider types and consumer groups are maintained.

When an agent changes location, it affects both its own situation and its interactions with others. The location is specified using polar coordinates , and the agent’s position is updated by adding random angular changes and to and . and are chosen randomly from the range . Consumers and providers change their locations with probabilities and , respectively.

A provider’s performance can also change by a random amount within the range with a probability of in each round. Additionally, with a probability of , a provider may switch to a different profile after each round.

5.2. Experimental Methodology

In our experiments, we compare the performance of the following three consumer groups:

- FIRE: consumer agents use the FIRE algorithm.

- CA_OLD: consumers use the previous version of the CA algorithm.

- CA_NEW: consumers use the new version of the CA algorithm.

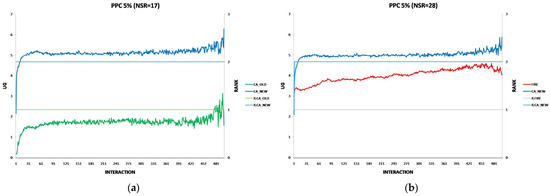

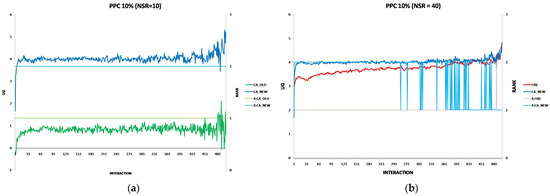

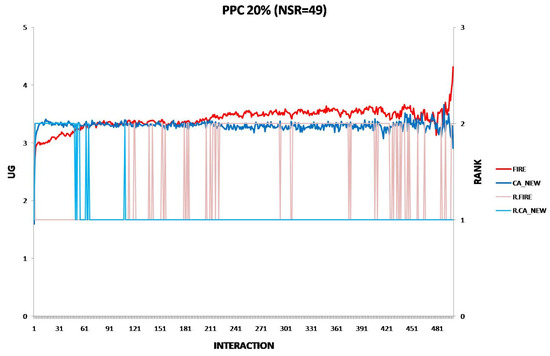

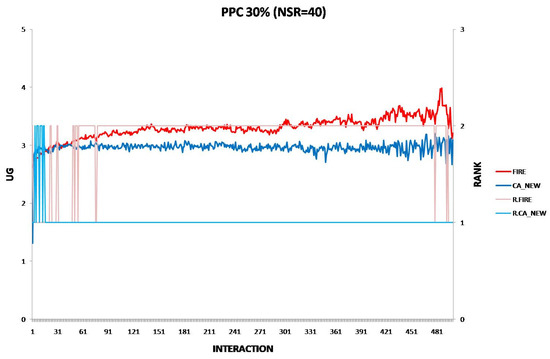

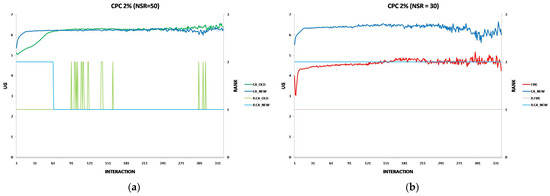

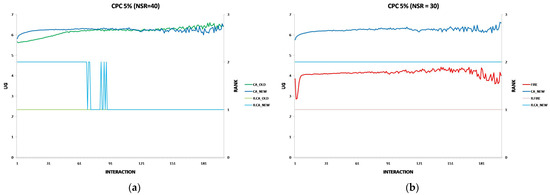

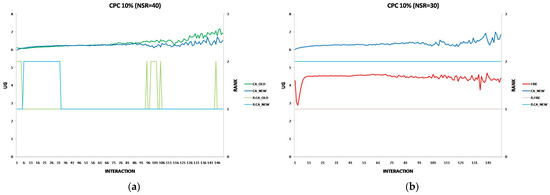

To ensure accuracy and minimize random noise, we conduct multiple independent simulation runs for each consumer group. The exact Number of Simulation Independent Runs (NSIR) varies per experiment to achieve statistically significant results. The exact NSIR values are displayed in the graphs illustrating the experimental results.

The effectiveness of each algorithm in identifying trustworthy provider agents is measured by the utility gain (UG) achieved by consumer agents during simulations. Throughout each simulation run, the testbed records the UG for each consumer interaction, along with the algorithm used (FIRE, CA_OLD, or CA_NEW).

After completing all simulation runs, we calculate the average UG for each interaction per consumer group. We then apply a two-sample t-test for mean comparison [29] with a 95% confidence level to compare the average UG between the following:

- CA_OLD and CA_NEW;

- FIRE and CA_NEW.

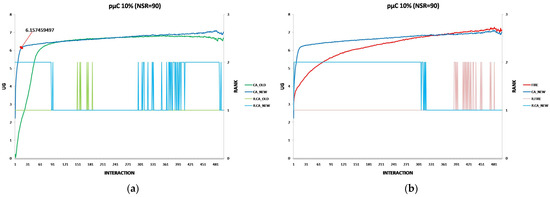

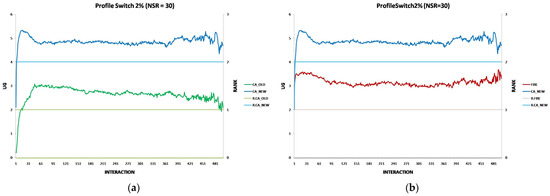

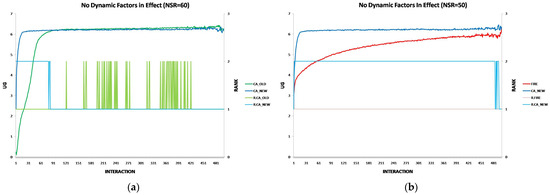

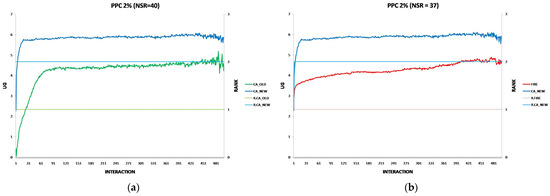

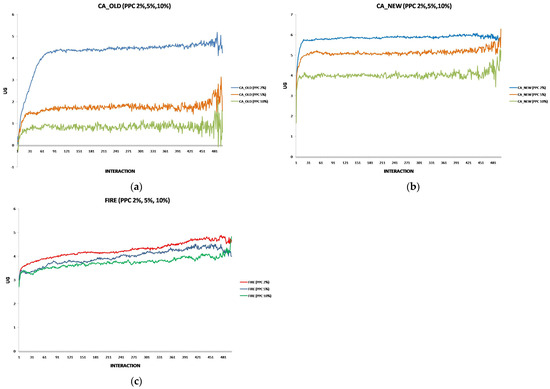

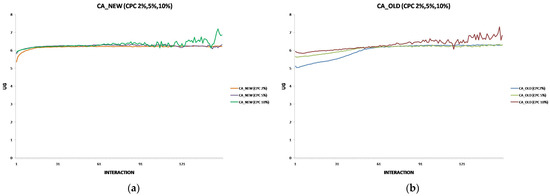

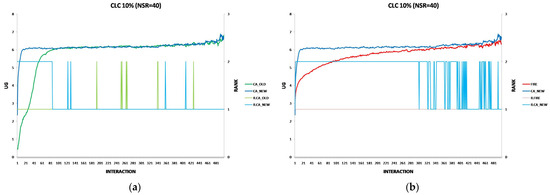

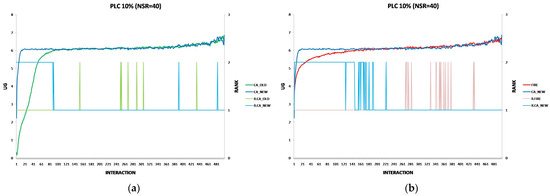

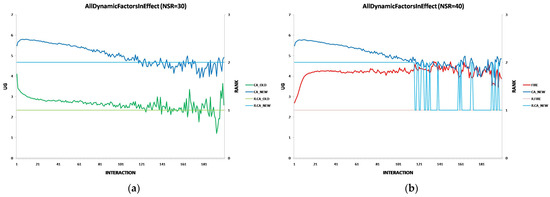

Each experiment’s results are displayed using two two-axis graphs: one comparing CA_OLD and CA_NEW and another comparing FIRE and CA_NEW. In each graph, the left y-axis represents the UG means for consumer groups per interaction, while the right y-axis displays the performance rankings produced by the UG mean comparison using the t-test. The ranking is denoted with the prefix “R” (e.g., R.CA), where a higher rank indicates superior performance. If two groups share the same rank, their performance difference is statistically insignificant. For instance, in Figure 1a, at the 17th interaction (x-axis), consumer agents in the CA_NEW group achieve an average UG of 6.15 (left y-axis), and according to the t-test ranking, the CA_NEW group holds a rank of 2 (right y-axis).

Figure 1.

(a) A performance comparison of CA_NEW and CA_OLD, when providers change performance with 10% probability per round: CA_NEW achieves better performance, especially in early interactions. (b) A performance comparison of CA_NEW and FIRE, when providers change performance with 10% probability per round: CA_NEW excels in early interactions (except for the first interaction), while FIRE adapts and slightly outperforms over time.