Abstract

This article presents the results of a systematic review investigating the potential of agricultural wastes as sustainable and low-carbon alternatives in reinforced concrete (RC) production. Background: The depletion of natural resources and the environmental burden of conventional construction materials necessitate innovative solutions to reduce the carbon footprint of construction. Agricultural wastes, including coconut shells (CSs), rice husk ash (RHA), and palm oil (PO) fuel ash, emerge as promising materials due to their abundance and mechanical benefits. Objective: This review evaluates the potential of agricultural wastes to improve sustainability and enhance the mechanical properties of RC structural elements while reducing carbon emissions. Design: Studies were systematically analyzed to explore the sources, classification, and material properties of agro-wastes (AWs), with a particular focus on their environmental benefits and performance in concrete. Results: Key findings demonstrate that AWs enhance compressive strength, tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity while reducing the carbon footprint of construction. However, challenges such as variability in material properties, limited long-term durability data, and lack of standardized guidelines hinder their broader adoption. Conclusions: AWs hold significant potential as sustainable additives for RC elements, aligning with global sustainability goals. Future research should address material optimization, lifecycle assessments, and regulatory integration to facilitate their mainstream adoption in construction.

1. Introduction

The rapid increase in the world’s population and technological advancements have led to a continual depletion of natural resources that meet human needs [1]. For future generations to benefit from these resources, global attention has shifted toward environmental sustainability. To achieve sustainability, existing resources must be utilized efficiently, and waste generated from production processes should be repurposed in the best possible manner. Studies aiming to address the economic and environmental crises caused by excessive consumption and inefficient resource usage seek solutions that prioritize resource conservation and efficiency, providing a roadmap for a sustainable economic model.

Agricultural land constitutes approximately 36% of the world’s total land area, indicating that many countries depend heavily on agricultural activities for their economy [2]. The production and processing of agricultural products generate plant and animal wastes, collectively referred to as agro-wastes (AWs). The recycling of these wastes is crucial for agricultural production and environmental sustainability [3]. In countries where agricultural activities are prominent, such as India, Brazil, China, Indonesia, and the United States, the feasibility of recycling these wastes and the opportunities it presents should be thoroughly assessed and managed, with appropriate methods applied to reduce waste at its source and convert it into reusable forms [4].

AWs can be utilized in various sectors, such as construction materials in the building industry [5,6], in textile manufacturing [7], and for energy production [8,9]. Such applications not only reduce environmental pollution but also facilitate the transfer of resources to future generations by minimizing the use of existing resources. Additionally, if agricultural enterprises supply these wastes as raw materials to other sectors, they can increase their income.

The concept of sustainability has recently gained significant attention in the construction sector as well. Humanity’s need for shelter and protection has evolved since the dawn of history, and the aim to preserve this legacy for future generations has become one of the primary goals of the construction industry. Today, the construction sector, which plays a crucial role in the development of emerging economies, occupies a central position in terms of sustainability due to its environmental, economic, and social impacts. For instance, the construction industry accounts for approximately 38% of global carbon dioxide emissions, and green technologies like AW integration can reduce embodied carbon significantly [5,6]. Economically, using AW in concrete production can lower costs by 15–20%, while socially, it offers opportunities to create local employment and improve community incomes [10]. The growth of the human population leads to an increase in construction activities, which, in turn, raises energy demand and resource consumption. The development of the construction sector and the expansion of urbanization have led to the depletion of non-renewable resources; the loss of biodiversity; deforestation; the reduction of agricultural land; soil, air, and water pollution; and global warming [5,6,11]. Furthermore, throughout a building’s life cycle and upon its demolition, the production of construction materials, which requires considerable energy and depletes natural resources, results in ongoing environmental challenges [10].

Concrete is a widely used building material that requires large amounts of components, making it costly. Studies have highlighted the resource-intensive nature of concrete production, which significantly impacts its cost and environmental footprint. As a major contributor to global CO₂ emissions, accounting for approximately 5–8% of the total due to its cement content, concrete production has driven the search for solutions to enhance sustainability and reduce carbon footprints within the industry [12,13,14,15]. These emissions from cement production underscore the necessity of adopting innovative approaches, such as alternative materials and recycled components [12,13,14,15]. Furthermore, recent research demonstrates how optimizing concrete properties and utilizing waste materials can mitigate these challenges, as evidenced in studies on autoclaved aerated concrete and ferroaluminate cement [16,17,18].

In many industrialized countries, the use of lightweight aggregates (LWAs) has somewhat reduced the depletion of natural resources. Additionally, the production of LWAs from industrial waste materials contributes significantly to sustainability. Using waste materials, such as expanded palletized fly ash (FA), expanded slag gravel, and blast furnace slag, as LWAs has led to substantial savings in construction [19,20].

Applying by-products, such as wheat straw (WS) ash, to geo-polymer beams as an eco-friendly alternative to traditional Portland cement concrete offers advantages like rapid strength gain, excellent mechanical properties, and prevention of water contamination [21]. Numerous studies have been conducted on using AWs in concrete production. An experimental study on the performance of RC beams found that using sustainable PO fuel ash (POFA) mortar (PM) and normal mortar as a bonding agent between the concrete substrate and glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) rods, instead of epoxy adhesive, demonstrated that POFA, an AW, could be used in construction [22]. Another study revealed that PO shells increased concrete strength, achieving compressive strengths greater than 40 MPa when used as concrete aggregates [23].

Research has shown that adding steel fibers, an AW, to CS concrete beams increased their ultimate moment capacity by 5–14% and flexural toughness by up to 45%. The span-to-deflection ratio of all fiber-reinforced CS concrete beams was reported to meet the requirements of IS 456:2000 [24] and BS 8110-97 [25,26]. RHA, an AW, creates a calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel around cement particles in concrete, resulting in a dense matrix that accelerates early strength development with an average density of approximately 2200–2550 kg/m3 [15].

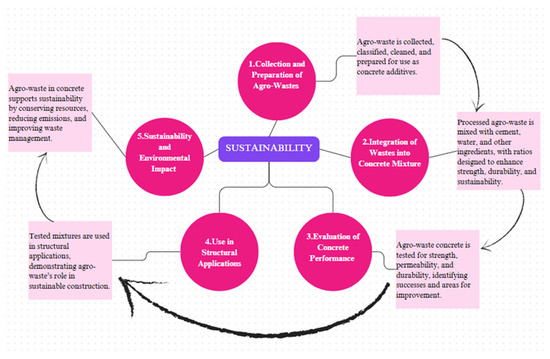

This study examines the use of AWs as sustainable materials in the construction sector. The growing global population and limited natural resources make environmental sustainability imperative. Recycling AWs provides both economic and environmental benefits (Figure 1). Accordingly, this study evaluates the existing literature on the potential and challenges of using AWs as construction materials in RC structures (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Broader process of sustainable utilization of agricultural waste (own research).

In recent years, the construction industry has explored various approaches to mitigate carbon emissions, including the development of low-heat cement. Studies such as “Hydration and Fractal Analysis on Low-heat Portland Cement Pastes Using Thermodynamic-Based Methods” highlight the energy-saving and carbon-reducing potential of this material. In addition to the utilization of agricultural wastes, these methods demonstrate the industry’s efforts to align with global sustainability goals. Incorporating such complementary strategies into concrete production could further enhance the sector’s environmental performance [27].

Agro-waste recycling is a significant approach to reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials. When considered alongside other carbon-reduction strategies, such as the use of low-heat cement and geo-polymer alternatives, it becomes evident that these approaches collectively contribute to a more sustainable construction industry. This integrative perspective highlights the potential of a multi-faceted approach to achieving carbon neutrality in the sector [28].

This scoping review aims to systematically explore the applicability of AW materials as sustainable, low-carbon alternatives in RC structural systems. Given the variety of agricultural by-products and their potential benefits in concrete production, a scoping review approach is well-suited to map current knowledge and identify key gaps. The review is organized around three main elements: population, which includes studies on AW in construction; concepts, focused on the integration of AW to enhance concrete’s sustainability and mechanical properties; and context, limited to applications in the construction industry, emphasizing load-bearing capacity. By consolidating findings from diverse studies, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the environmental and mechanical impacts of AWs in RC systems, offering a foundation for developing more sustainable construction practices and highlighting areas for future research within industry standards.

2. Definition, Classification, and Potential Applications of Agro-Wastes

AWs consist of plant- and animal-derived materials generated from agricultural and livestock activities. These wastes can generally be categorized into three main types: plant-based wastes, animal-based wastes, and food processing wastes.

Plant-based wastes are derived from plant production and processing activities. For example, residues such as straw, leaves, husks, and fruit pits result from agricultural activities. Materials like rice husk, wheat straw, and coconut shell fall under this category of AWs. Given their positive effects on concrete properties, such as strength and permeability, or their ability to enhance mechanical properties, reduce plastic cracking, and improve impact resistance, these wastes hold potential for use in concrete production in the construction industry. They are generally low-density and organic in nature, making them particularly appealing for lightweight concrete production [29,30].

Animal-based wastes from livestock activities include materials such as manure, hair, hooves, hides, bones, and blood. These wastes can be used as organic fertilizers and evaluated as biomass for energy production. Processing animal wastes for organic fertilizer production or converting them into biomass for energy generation is an important step for environmental sustainability [31].

Food processing wastes arise from processing activities in the agriculture and food industries. Examples include pulp generated during juice production or husks and seeds released during oil processing. These wastes can be utilized as fertilizer or energy sources through composting or pyrolysis processes. Some of these wastes also have potential applications in the construction sector [32].

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on the potential use of AWs, particularly for lightweight concrete production in the construction sector. Recent studies have investigated the potential of wastes like coconut fiber and RHA to enhance concrete’s mechanical properties and offer environmentally friendly solutions [30,33]. The behavior of these wastes in concrete and their performance as fibrous building materials are further examined to understand their potential more closely.

AWs are valuable resources that can be utilized across various sectors beyond construction. Applications such as energy generation, composting, and fertilization enhance environmental sustainability by promoting the recovery of these wastes [34]. For example, using AWs as biomass contributes to the development of renewable energy sources. Additionally, organic fertilizers derived from these wastes can replace chemical fertilizers in agriculture, enhancing soil fertility. Thus, the versatile use of AWs is essential for mitigating environmental issues and providing economic benefits [34].

In the coming years, the use of AWs in the construction sector is expected to become more widespread. The search for sustainable construction materials increases the potential of AWs and encourages researchers to develop innovative solutions in this area. The incorporation of wastes such as coconut fiber, rice husk, and WS in concrete not only improves material properties but also reduces environmental impacts. In this context, AWs are anticipated to be used more frequently in the production of lightweight concrete, composite materials, and other building materials. This shift within the industry will enhance environmental sustainability while reducing costs.

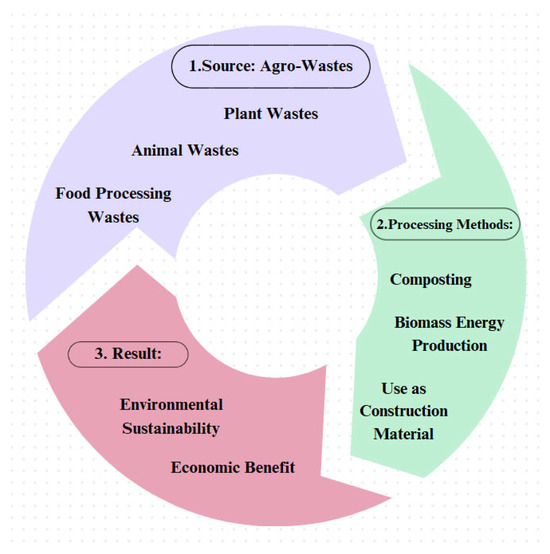

The definition, classification, and potential applications of AWs across various sectors highlight the value of these materials (Figure 2 and Table 2). Figure 2 specifically illustrates the sources of AWs, the various processing methods (e.g., composting, biomass energy production, and construction material use), and the resulting environmental and economic benefits. The effective utilization of AWs contributes to environmental sustainability while preserving natural resources. Therefore, developing new policies to increase the integration of AWs and promoting research in this area are necessary. Moreover, conducting more experimental and theoretical studies on the use of AWs in the construction sector will advance knowledge in this field. In the future, the evaluation of AWs within the framework of the circular economy will be of great importance for sustainable development.

Figure 2.

Sources, processing methods, and results of agro-waste utilization (own research).

Table 2.

Potential environmental benefits according to agro-waste types and usage fields (own research).

3. The Use of Agro-Wastes in Concrete Production

This section examines studies in the literature on the use of AWs in concrete production.

3.1. Use of Coconut Shells and Fibers

Among AWs, CSs and other fibers, when combined with FA in the cement matrix, have improved properties such as compressive strength, flexural and tensile strength, water absorption, porosity, and permeability of concrete. Compared to concrete where only CS is used, this combination has shown better results [30,35].

For instance, CS + 0.75% steel fiber concrete exhibited a compressive strength of 47.8 MPa, compared to 35.6 MPa for CS concrete without fibers, representing a significant improvement [26]. Additionally, the inclusion of FA enhanced the workability of fresh concrete and mitigated the strength loss observed in mixes with higher CS content. The combination of CS and FA improved tensile strength by 15%, reaching up to 4.8 MPa in certain mixes [26,30,35].

CS can be partially used as a coarse aggregate in lightweight concrete production and is suitable for non-load-bearing structures, strip foundations, and non-structural elements. Using waste CS materials in sustainable and efficient applications is thought to minimize environmental concerns. With a specific gravity of 1.33 tons/m3 compared to traditional concrete’s 2.67 tons/m3, CS allows concrete to be classified as lightweight [36]. According to ASTM C330 [37], the 28-day compressive strength of lightweight concrete containing CS aggregate is reported to be 16 N/mm2. Replacing 20% of coarse aggregate with CS can yield higher strength.

Initially, CS concrete shows low resistance to water absorption; however, this resistance improves in later stages as the bond between the cement paste and aggregates strengthens [36].

Studies indicate that adding not only CS but also fibers and FA enhances the mechanical properties of concrete [26,30,35]. The use of coconut fibers as reinforcement in a cement matrix offers potential for producing lighter composites due to its low intrinsic density and structure that allows air bubble accumulation [38,39]. CS concrete partially substituted with FA is environmentally friendly, given that CSs are renewable and FA is an industrial by-product [35,40]. Compressive strength decreases as the CS content increases, with a 24% reduction observed when 15% CS is substituted in regular concrete [36].

Experiments to determine the thermal conductivity of fiber bundles found that increasing the density of fiber bundles from 30 to 120 kg/m3 reduced thermal conductivity from 0.052 to 0.024 W/m·K [38]. While heat treatment reduced tensile strength, tensile stress at break increased significantly after chemical and physical treatments by 18% and 51%, respectively, with increased ductility [39,41]. Adding coconut fibers improved both conventional concrete and CS aggregate concrete properties; however, further studies on durability, temperature resistance, and structural behavior under various loading types are needed. Mechanical test results indicate that excessive fiber content or fiber orientation in the matrix significantly contributes to the strength properties of the mix [41]. Optimal strength performance for mortars was obtained with a 1% fiber content, though overlapping fibers in cases of high fiber volume may create failure paths under load.

Although the strength of concrete decreases with increased CS aggregate content, values close to conventional concrete allow for using CS aggregates at 10–20% levels [40,42]. Complete replacement of natural coarse aggregates with CS aggregate leads to gradual reductions in both slump and hardened properties. Incorporating FA into the cement paste improves fresh concrete workability, and adding up to 20% FA can compensate for concrete strength loss [35,43]. Thus, using CS aggregate alongside FA is a viable alternative for environmentally sustainable concrete production [26,30].

The mechanical properties of AW concrete show significant improvements when specific combinations are used. For example, CS concrete combined with 0.75% steel fibers exhibited a compressive strength of 47.8 MPa compared to 35.6 MPa for CS concrete without fibers [26,43]. Additionally, the inclusion of FA improved the tensile strength by 15% and enhanced fresh concrete workability [35,42]. The modulus of elasticity remained comparable to conventional mixes, ensuring suitability for lightweight structural applications [38]. However, challenges such as variability in material properties and long-term durability remain, highlighting the need for further research [39].

3.2. Contributions of Palm Oil Fuel and Rice Husk Ash

A PO fuel ash and RHA, other AWs used as supplementary cementitious materials in concrete production, can significantly enhance concrete’s compressive strength. While studies indicate that calcined PO fuel ash (heated to 600 °C for two hours) can significantly improve compressive strength, limited research is available regarding the specific effects of raw PO fuel ash and raw RHA on compressive strength. However, studies such as [44] have shown that calcination significantly enhances the performance of these materials. This increase is attributed to higher amorphous silica content and reduced loss on ignition (LOI) due to heat treatment [44,45].

Similarly, using finely ground RHA as a supplementary cementitious material increased the compressive strength of the concrete compared to control concrete. Optimal compressive strength for RHA concrete was observed at a 20% substitution rate, attributed to increased pozzolanic activity and more nucleation sites [46,47]. Higher RHA content, however, resulted in strength reduction due to a dilution effect. Substituting Ordinary Portland Cement with 20% PO fuel ash increased compressive strength by 10.8%, while adding 20% RHA improved strength by 11.9% compared to reference concrete [44,45,46,47].

Concrete produced using PO shell aggregate is classified as lightweight. After 28 days of air drying, this concrete’s density, approximately 1960 kg/m3, is 18% lighter than normal-weight concrete (2400 kg/m3). Additionally, the compressive strength obtained after 28 days exceeds the 17 MPa minimum required for structural lightweight concrete by 35–65% [48].

In another study, PO shell was investigated as an aggregate for lightweight concrete, with 28-day compressive strength tests conducted with and without limestone powder. Results demonstrated compressive strengths of approximately 43–48 MPa and dry densities of about 1870–1990 kg/m3. The addition of limestone powder improves particle packing density, reduces porosity, and enhances compressive strength through its filler effect and role as a nucleation site for hydration reactions. These improvements contribute to the observed differences in strength and density between the two cases [49].

Studies on PO shell, PO shell ash, and PO clinker in concrete production have shown that green lightweight concrete positively impacts workability, density, compressive strength, split tensile strength, flexural strength, stress-strain curve, modulus of elasticity, water absorption, and shrinkage. These findings suggest that using high-volume PO waste as lightweight aggregates supports environmentally friendly structural lightweight concrete production. This approach can also contribute to sustainable development in the construction and agriculture sectors of PO-producing countries [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

3.3. Use of Wheat Straw in Concrete Production

Another AW used in the construction sector is WS. Straw concrete, a bio-based composite, is designed for thermal insulation in new buildings and thermal retrofitting of existing ones. WS is combined with lime or gypsum binders and natural additives (such as hemoglobin, casein, and gelatin) to enhance the material’s thermal and mechanical properties. These composites exhibit attractive thermal conductivity and acceptable mechanical strength [62].

WS additives are considered suitable for non-load-bearing building insulation materials. Optimizing the orientation of straw fibers in bales reduces thermal conductivity by 38% compared to conventional agricultural bales, allowing for similar reductions in insulation thickness while achieving equivalent performance. Additionally, optimizing fiber orientation reduces water vapor permeability, moisture buffering, and moisture ingress by up to 76% [63].

WS was also evaluated as an insulation material for fired clay hollow bricks, with significant energy efficiency contributions. Walls containing densely compacted straw achieved energy savings of up to 69.08%. This finding highlights WS’s potential to insulate hollow clay bricks used in building walls, offering energy and cost savings and environmental advantages [64].

WS ash is another AW with potential for concrete use. Adding WS ash to concrete improves mechanical properties such as compressive strength, flexural strength, modulus of elasticity, and tensile strength. Compared to conventional concrete, mixes with 5% and 10% cement replacement with WS ash showed compressive strength increases of 8% and 12%, respectively. However, higher ash dosages reduce mechanical performance due to decreased flowability. Depending on the source, aggregates, water-to-binder ratio, and mix design, the optimal dose of WS ash is between 10% and 20% [65].

3.4. Other Agro-Wastes and Lightweight Concrete Applications

AWs like sugarcane, pineapple waste, and walnut shells can also enhance concrete’s strength and compressive strength [2]. Studies have shown that such wastes benefit concrete strength, compressive strength, thermal insulation, and sound insulation in non-load-bearing structures. For example, sugarcane bagasse ash has been reported to enhance thermal insulation properties [66], while walnut shells contribute to reducing sound transmission in lightweight concrete applications [67]. Pineapple fiber-based composites have also demonstrated improvements in both compressive strength and insulation capabilities [68].

Overall, research shows that using AWs as alternative materials in concrete production provides environmental sustainability and economic benefits. In lightweight concrete applications developed for non-load-bearing structural elements, wastes like CS [40,43], PO ash [44,45], RHA [46,47], and WS [21,65] offer positive contributions to properties such as strength, thermal insulation, and sound insulation. Using these wastes in conjunction with other cementitious materials increases concrete’s compliance with standards, expanding its potential applications (Table 3). Future studies should further investigate these materials’ long-term durability, thermal performance, water absorption behavior, and mechanical strength properties under various loading conditions.

Table 3.

Technical, environmental, and economic contributions of agro-wastes to concrete (own research).

3.5. Durability and Long-Term Performance of Agro-Wastes in Concrete

The durability and long-term performance of AWs in concrete remain critical factors for their widespread applicability in structural systems. While short-term studies have demonstrated improvements in mechanical properties, water absorption resistance, and compressive strength, limited data exist on their performance under real-world environmental conditions, including moisture exposure, freeze-thaw cycles, and chemical attacks.

RHA and PO fuel ash have shown notable contributions to durability as partial replacements for cement. For instance, studies indicate the following:

- RHA at an optimal replacement level of 20% significantly enhances compressive strength and durability, reducing the carbon footprint and industrial waste [47,53,54,55,56].

- PO fuel ash improves the mechanical properties and durability when heat-treated, with positive effects on resistance to aggressive environmental conditions [50,54,55,56,57].

However, for other AW materials such as CSs, coconut fibers, WS, and other AWs, studies focusing on long-term durability and performance remain scarce.

- CSs and fibers: Although these materials improve mechanical properties, tensile strength, and ductility, their behavior under long-term exposure to moisture, freeze-thaw cycles, and chemical attacks is not well understood. Further studies are required to assess their degradation rates and overall stability in structural applications.

- WS and ash: Research has highlighted their contributions to thermal insulation and mechanical properties. However, the long-term durability of WS-based composites, particularly their resistance to biodegradation and thermal stress, requires further investigation.

- Other AWs: Materials such as PO clinker and other lightweight agro-based aggregates have shown promise in enhancing mechanical properties, but their performance in varying environmental conditions has not been comprehensively studied.

To address these gaps, future studies should focus on the following key areas:

- Conducting lifecycle analyses (LCA) to evaluate the full environmental impact of AWs in concrete, including production, usage, and end-of-life stages.

- Investigating the degradation rates of AW-based concrete under diverse environmental conditions, such as humidity, freeze-thaw cycles, chemical exposure, and thermal variations.

- Developing standardized durability testing protocols to ensure the consistent evaluation of AW materials in structural applications.

These efforts will provide a comprehensive understanding of the viability of AWs in real-world applications and contribute to their acceptance as sustainable alternatives in the construction industry.

4. Feasibility of Agro-Waste Utilization in Reinforced Concrete (RC) Elements

This section provides an in-depth analysis of the applicability of AWs specifically in RC beams, assessed through the findings in the literature and the summarized data presented in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A. Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A consolidates data derived from studies investigating the effects of AWs on RC beams and their mechanical properties. The purpose of this evaluation is to expand the existing knowledge and to promote the feasibility of AWs as sustainable alternatives in RC elements. The findings related to the use of AWs in RC elements are discussed under the following headings.

4.1. Potential of Agro-Wastes for Use in Reinforced Concrete Elements

The impact of AWs on structural systems holds significant importance in terms of both environmental pollution and sustainability. This section examines the effects of AWs on the construction industry, particularly their influence on RC beams. Data from studies investigating the structural effects of AWs on RC beams are summarized in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A. The increasing use of agricultural by-products as construction materials underscores the growing demand for sustainable building materials [69,70,71]. However, the available data on the performance of these wastes in RC beams remain limited. This study aims to address this knowledge gap and serve as a valuable resource for relevant industries.

Research findings indicate that AWs make valuable contributions to understanding the effects of these materials on the durability, strength, and overall performance of RC beams in the construction sector [72,73,74,75]. Additionally, it is emphasized that further comprehensive studies are required to investigate the structural advantages of using AWs in varying proportions and types. Future research should expand to include an evaluation of the environmental and economic benefits of these materials.

4.2. Agro-Waste Types Used in RC Elements

Studies have identified the use of various AW types in the production of RC beams. Materials such as flax-reinforced coconut fibers [76], PO shells [69,74], palm kernel shells [77,78], PO fuel ash [45], CS [38,73], WS ash [21], banana fibers [79,80], natural fibers [41,81], and other agricultural by-products have been considered within this scope. These materials have led to significant modifications in the mechanical properties of RC beams. Recent studies, such as [81], highlight the potential of advanced natural fiber composites in improving structural behavior and promoting sustainability in RC systems.

Particularly, research has focused more extensively on the application of PO shells, palm kernel shells, and PO clinker in concrete beams. These materials have been found to exert notable effects on both the mechanical and physical properties of the resulting RC elements [75,82,83,84].

4.3. Effects of Agro-Wastes on RC Elements

The impacts of AWs on RC (RC) elements represent a compelling area of research, both in terms of environmental sustainability and structural performance. This section provides a detailed examination of the utilization of various AW types in RC beams, evaluated in light of relevant standards (BS8110 [25], ASTM C330 [37], ACI-318 [72]) and experimental studies in the literature. The effects of AWs on structural parameters such as mechanical properties, density, ductility, and cracking behavior are analyzed, emphasizing their potential for advancing sustainable construction materials. The following subsections comprehensively evaluate these effects.

4.3.1. Mechanical Properties and Structural Performance

In the reviewed studies, concrete beams prepared with AW used in RC beam production were compared with traditional concrete beams. An assessment was conducted to determine whether they met the requirements specified in standards such as BS8110 [25], ASTM C330 [37], and ACI-318 [72]. The geometric properties of the beams used in these studies, as well as the effects of AW, are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Studies on the use of agro-waste in reinforced concrete beam production (own research).

The effects of agro-waste on the mechanical strength of load-bearing systems necessitate the examination of mechanical properties such as compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, and tensile strength. Determining these effects is crucial for evaluating the mechanical performance and structural durability of materials. Studies have demonstrated that the fibers contained in AW positively influence the strength and resilience of beam materials.

Experimental data reveal that AW improves the structure and durability of beams while enhancing resistance to corrosion. These findings support the broader adoption of AW in the construction sector, particularly for sustainable applications [89,90]. However, further studies are required to comprehensively evaluate the effects of AWs on corrosion resistance under aggressive environmental conditions, such as chloride penetration and carbonation. Limited data indicate that AW materials may influence the alkalinity of the concrete matrix, potentially impacting the protective environment for embedded steel reinforcement. Additionally, environmental effects must also be considered, and waste management strategies should be developed.

Preliminary tests conducted on concrete containing various proportions of AW have assessed mechanical properties, which are summarized in Table 5. Table 5 presents the results of mechanical tests performed to evaluate the effects of AW on RC elements. The table includes information on the types of AW used in concrete mixtures, contribution ratios, tested mechanical properties (e.g., compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, flexural strength), test conditions, and performance comparisons.

Table 5.

Mechanical properties and test results of agro-waste blended concrete (own research).

4.3.2. Density and Insulation Properties of Concrete

Studies have shown that lightweight concrete produced with palm oil shells has a lower density and better insulation properties compared to conventional lightweight concrete [74]. Furthermore, the results of shear strength tests on foamed concrete reveal that lower-density concretes tend to exhibit lower shear strength. This observation suggests that while lightweight aggregates can optimize the density properties of concrete, they may also introduce certain mechanical limitations [69].

The use of PO shells as lightweight aggregates has been highlighted for its positive impact not only on density but also on thermal insulation performance. The incorporation of such AWs in RC structures presents significant potential for developing sustainable construction materials and enhancing energy efficiency in buildings.

4.3.3. Ductility and Cracking Behavior

Concrete beams produced with PO shells exhibit higher ductility ratios compared to conventional concrete beams, with an elastic modulus measuring only 25% of that of control concrete. Furthermore, it has been observed that PO shell concrete beams experience twice as many shear and flexural cracks as conventional beams, with closer crack spacing and narrower crack widths [69].

Concrete beams incorporating CSs behave similarly to conventional concrete beams under torsion but exhibit slightly wider crack widths and less stiffness compared to traditional crushed stone aggregates [84]. The addition of steel fibers exceeding 0.5% significantly enhances the moment capacity and crack resistance of beam specimens [26].

These findings indicate that AW materials can be effectively utilized to optimize the ductility and cracking behavior of concrete beams. For instance, studies on flax fiber-reinforced coconut fiber concrete beams show that while the inclusion of coconut fibers has a limited effect on flexural strength, it significantly improves ductility performance [85].

The use of PO shells as lightweight aggregates has also been reported to enhance the strength and durability of concrete. Additionally, beams produced with PO shells demonstrate satisfactory flexural performance and positively influence stiffness and strength properties. Experimental results confirm that these beams exhibit good ductility behavior and maintain crack widths within acceptable limits [70,74,86].

Palm kernel shells, used as coarse aggregates in structural concrete, also present a viable alternative. Beams made with palm kernel shell concrete perform better than conventional concrete beams in terms of cracking, reinforcement stress, and aggregate interlock. Despite having a lower fracture modulus, which may lead to early cracking, these beams exhibit narrower and more closely spaced cracks, along with high ductility [77,78].

4.3.4. The Impact of Agro-Waste on Energy Absorption and Torsional Strength

Steel fiber-reinforced palm shell concrete beams have shown a significant increase in torsional strength and improved pre-crack torsional behavior due to enhanced concrete strength [83]. PO clinker concrete beams exhibit similar properties to those made with PO shells, although an increase in steel reinforcement ratio is associated with a reduction in ductility [75,82].

In terms of energy absorption, concrete beams prepared with PO fuel ash demonstrate lower energy absorption compared to traditional concrete. However, combining such AW with steel fibers enables the optimization of energy absorption properties and enhances torsional strength [22].

PO fuel ash, categorized as AW, holds significant potential for improving the strength of reinforced concrete structures. Its use aligns with zero-waste initiatives, offering a sustainable alternative material when employed as a partial adhesive substitute in concrete beams [22].

AW ashes exhibit notable potential as sustainable construction materials in RC beams. Incorporating these ashes into concrete mixtures has led to significant improvements in load-bearing capacity, torsional strength, ductility, and deflection compared to traditional concrete beams. These advancements contribute to the development of more flexible and sustainable concrete structures. AW ashes, such as WS ash and RHA, have been highlighted as environmentally sustainable materials capable of enhancing concrete structure durability [71].

Experimental investigations on concrete beams reinforced with WS ash and RHA under static loading conditions reveal the impact of varying mixture ratios on structural performance. Results indicate that using these ashes at an optimal 15% replacement ratio significantly improves flexural behavior, representing a balance between mechanical strength and structural sustainability [88].

Recycled agricultural and industrial waste materials offer considerable advantages in geo-polymer RC beams. For example, geo-polymer concrete incorporating fibers derived from turning shops or workshops, combined with WS ash, demonstrates both economic and mechanical superiority. These materials have enhanced load-bearing capacity compared to traditional RC beams and exhibit improved energy absorption and reduced crack propagation. The addition of steel and recycled turning fibers has resulted in higher ultimate load capacity and increased structural resilience, emphasizing the potential of recycled WS ash as a sustainable alternative to steel fibers [21].

4.3.5. Performance of Coconut Shell and Banana Fiber-Reinforced Concrete

Concrete reinforced with steel fibers and CSs, partially replacing coarse aggregates and cement with Class F FA, has shown an increase in ultimate moment capacities by 5–14% during beam tests [26]. Additionally, CS concrete beams exhibited good ductile behavior, with crack widths remaining within acceptable limits. It is also suggested that the fire resistance of such concrete types should be further investigated to assess their viability in ensuring fire safety [73].

Banana fiber-RC beams demonstrated approximately 25% higher flexural strength compared to unreinforced beams, although the compressive strength of the concrete had a limited effect on the ultimate load capacity. This indicates the potential of banana fibers as a performance-enhancing reinforcement material in RC elements [79,80,91].

Studies on flax fiber-reinforced coconut fiber concrete beams revealed that while coconut fiber content had a limited impact on flexural strength, specimens containing 3% coconut fiber achieved the highest energy absorption of approximately 83.23 J compared to other specimens [85]. Research on steel-RC and flax fiber-reinforced polymer tube-confined coconut fiber concrete beams demonstrated that adding coconut fibers significantly improved ultimate load capacity, deflection, and ductility. These findings highlight the potential of coconut fiber additions to reduce reliance on steel reinforcements [76].

Steel fibers remain a widely used material for improving the durability of RC structures. However, utilizing AWs in the construction sector as part of a sustainability agenda provides significant benefits for conserving natural resources. It is crucial to conduct more comprehensive research on the standalone effects of AWs in concrete applications to fully understand their potential.

4.4. Limitations of Using Agro-Wastes in RC Elements

Studies indicate that AWs, such as PO residues, used as aggregate supplements in concrete production, demonstrate structural behaviors comparable to or even superior to conventional concrete. The primary aim of incorporating AWs into RC structures is to reduce the consumption of natural resources and contribute to effective waste management processes. However, these materials are often combined with steel or adhesive reinforcements to enhance their performance. Further research is needed to evaluate the standalone efficacy of AWs as structural materials without supplementary reinforcements. Additionally, more comprehensive studies are required to assess their practical applicability on a larger scale.

Materials like CSs have shown promising results as effective alternatives in RC elements. Specifically, they have exhibited typical structural behavior in flexural tests, with acceptable crack widths and good ductility. Despite these positive findings, the large-scale application of CSs as a replacement for conventional coarse aggregates necessitates more experimental data and validation [73].

Several factors limiting the application of AWs in RC elements have been identified in the literature:

- Material Homogeneity: Variations in the physical and chemical properties of AWs pose challenges in mix design, potentially affecting material homogeneity and performance consistency [6,7].

- Long-Term Durability: The inclusion of AWs in concrete may influence long-term mechanical strength and environmental resistance. This highlights the need for considering unaddressed parameters in existing standards and conducting durability tests to evaluate their long-term effects [34].

- Lack of Standards: The absence of comprehensive international standards regulating the use of AWs in RC elements restricts their widespread adoption. Existing standards such as BS8110, ASTM C330, and ACI-318 need to be expanded to address the potential applications and performance of AWs [25,37,72].

These limitations represent the primary challenges hindering the widespread use of AWs in RC elements. Addressing these issues will be a crucial step toward developing more sustainable construction materials.

4.5. Future Research Directions

Understanding the behavior of CS-based concrete beams in real structural environments requires field studies and applied research. Developing new reinforcement techniques is critical to enhancing the durability of these types of concrete. Such advancements can promote the broader adoption of CS-based concrete in the construction industry and help maximize its potential benefits. Additionally, investigating the effects of different components and mix ratios of CS-based concrete on the behavior of RC elements is essential. Exploring specific structural properties, such as fire resistance, could reveal the potential of this material to improve fire safety. The findings from these studies can encourage the widespread use of CS-based concrete and contribute to the sustainability of construction projects.

Similarly, the positive effects of banana fiber reinforcement on concrete structural elements indicate its potential as a performance-enhancing material in the construction sector. Further research is required to explore the economic benefits and structural performance of banana fiber-reinforced RC elements.

Future studies on the use of AWs in RC elements should focus on the following areas:

- Fire Resistance: The fire behavior of AW-based concretes, particularly CS-based concrete, should be examined to evaluate its potential for improving fire safety in structural applications.

- Innovative Reinforcement Techniques: Novel reinforcement methods should be developed to enhance the durability of RC elements. These innovations can support the sustainable use of materials in both existing RC elements and new constructions.

- Economic and Environmental Impacts: The economic advantages and contributions of AWs to environmental sustainability as construction materials should be analyzed in detail. Life cycle assessments can provide valuable insights into these impacts.

- Applied Research: Field studies and practical experiments in real structural environments are essential. Such research would provide a deeper understanding of the long-term durability, load-bearing capacity, and other structural properties of AW-based concretes.

These research directions aim to encourage the use of AWs in RC elements, thereby supporting environmental and economic sustainability goals within the construction industry.

5. International Standards and Current Regulations

This section explores the relationship between AW applications in RC elements and existing international standards and regulations. While the use of AW in construction has gained attention for its sustainability potential, current codes and standards (e.g., BS8110 [25], ASTM C330 [37], ACI 318 [72]) often fail to comprehensively address the integration of these innovative materials. This limitation presents challenges in ensuring compliance and optimizing structural performance in practical applications.

5.1. Overview of Relevant Standards

- BS8110: A structural design standard focused on reinforced and prestressed concrete. Its application in experimental studies of AW materials, particularly in beams, has highlighted its limitations in accommodating novel materials with variable properties [26,73].

- ACI 318: A widely recognized standard for concrete building design, covering structural integrity, durability, and reinforcement design. Its adaptability to materials such as CSs or palm kernel ash has yet to be adequately tested in real-world scenarios [74,75].

- ASTM C330: Primarily addressing lightweight aggregates, it has limited provision for alternative materials such as PO shells or banana fibers [69,77].

5.2. Challenges in Standard Adaptation

The integration of AW-based materials into RC elements poses unique challenges, particularly when it comes to adapting existing standards to accommodate these unconventional materials. These challenges can be categorized into material-specific limitations, modeling uncertainties, and assessment methods, including force-based and displacement-based evaluations.

Material-Specific Limitations. The heterogeneity and variability in the properties of AW materials present significant obstacles in achieving consistent performance predictions:

- Material Homogeneity: AW aggregates and fibers exhibit varying physical and chemical properties, influencing both mechanical and durability characteristics [6,11]. This variability complicates standard calibration efforts.

- Durability Concerns: Long-term performance under environmental exposure, such as carbonation and freeze-thaw cycles, is insufficiently addressed in existing standards [34]. For instance, the absence of provisions for bio-based material degradation in codes such as BS8110 and ACI 318 limits their application [25,72].

Modeling Uncertainties. Incorporating AW-based materials into structural design introduces modeling complexities, as conventional methods may not fully capture their mechanical behavior:

- Force-Based Evaluations: Standards like ACI 318 [72] rely on force-based design principles, which assume isotropic and homogenous material properties. However, AW materials often deviate from these assumptions, leading to discrepancies in predicted versus observed behaviors [69]. For example, PO shell concrete beams exhibited deviations of up to 25% in shear force predictions under force-based methods [69].

- Displacement-Based Methods: Advanced assessment techniques, such as displacement-based design, can better account for the ductility and cracking patterns observed in AW-modified concretes [26,80]. Coconut aggregate beams, for instance, demonstrated high ductility under displacement-controlled loading conditions, challenging the current reliance on force-based metrics [26].

Assessment and Calibration Gaps. Despite the progress in experimental studies, the lack of harmonization between experimental findings and code provisions limits the broader application of AW materials:

- Seismic Performance Considerations: The absence of guidelines for displacement-based seismic design using AW-based concretes is a critical gap. Experimental results, such as those from banana fiber-reinforced beams, suggest significant energy dissipation potential, yet these characteristics are not reflected in existing seismic design codes [91].

- Calibration for Bio-Based Materials: Standards like ASTM C330 [37] focus on lightweight aggregates but do not account for bio-based material properties such as moisture absorption and fiber-matrix bonding. Studies on palm kernel shell concretes have revealed the importance of these factors in predicting shear capacity [77].

Broader Implications. Bridging these gaps requires coordinated efforts to adapt and expand existing standards:

- The development of material-specific calibration factors for force- and displacement-based methods.

- Incorporating environmental degradation factors and bio-material interactions into durability provisions [22,83].

- Harmonizing experimental findings, such as those summarized in Annex 1, with the predictive models employed in international standards [73,80].

The inclusion of AW materials in RC elements represents a pivotal opportunity for sustainable construction. However, addressing the challenges in adapting standards will require a collaborative approach, combining experimental evidence, advanced modeling techniques, and regulatory updates.

5.3. Comparison of Experimental and Theoretical Results

The comparison of experimental and theoretical results reveals valuable insights into the structural performance of AW-based RC beams. Variations in predictive accuracy often stem from material properties, reinforcement configurations, and the complexity of theoretical models. For instance,

- Coconut aggregate beams [26] showed up to a 10% deviation in failure load predictions, highlighting the need for further refinement in theoretical models for natural aggregate replacements.

- PO shell foamed concrete beams [69] exhibited variations in shear force prediction depending on reinforcement type and ratio, with deviations ranging between 5% and 15%.

- Rice straw ash-RC beams [88] demonstrated deviations in flexural strength predictions, with experimental values being approximately 10% higher than theoretical predictions for certain reinforcement ratios.

- Banana fiber-reinforced beams [80,91] indicated consistent discrepancies in failure torque, with experimental results surpassing theoretical predictions by up to 20%, emphasizing the impact of fiber properties on load-bearing capacity.

- Palm kernel shell concrete without shear reinforcement [77] displayed deviations in shear force prediction, with experimental results nearly 25% higher than theoretical estimates, suggesting the need for incorporating material-specific calibration factors in theoretical equations.

- PO concrete beams with steel fibers [83] demonstrated deviations in predicted crack torque values of up to 15%, underscoring the importance of accurately modeling fiber-concrete interactions.

These comparisons highlight the complexity of modeling AW-based concrete and underline the necessity for advancing theoretical frameworks to better reflect the unique properties and behaviors of these innovative materials.

5.4. Recommendations for Standard Evolution

The integration of AW into RC standards requires a structured approach, addressing the challenges identified in previous sections. This approach must encompass the development of new testing protocols, updates to existing standards, and the promotion of practical applications. Table 6 provides a detailed summary of the challenges, relevant standards, and specific recommendations identified throughout this study. These insights aim to facilitate the evolution of RC standards while supporting sustainability and innovation in construction materials.

Table 6.

Comprehensive insights and recommendations for agro-waste integration in RC standards (own research).

This framework provides actionable steps to address the challenges and limitations of integrating AW into RC standards. By focusing on material performance, predictive accuracy, and sustainability, these recommendations aim to bridge the gap between experimental research and real-world applications, ensuring a robust and environmentally responsible approach to construction practices. To integrate AW materials into RC element standards and fully harness their sustainability and performance potential, the following steps are recommended:

I. Develop Specific Testing Protocols. Existing testing protocols are often insufficient to address the unique properties of AW materials:

- Customized Testing: Develop modified compression and shear testing methods tailored for bio-based aggregates and fibers. For instance, palm oil shell concrete demonstrated distinct cracking patterns that require alternative testing metrics [69,77].

- Environmental Simulation: Introduce durability tests accounting for moisture absorption, carbonation, and freeze-thaw cycles unique to agricultural materials [34,80].

II. Incorporate Predictive Models. Theoretical and numerical models can play a crucial role in adapting standards:

- Theoretical Frameworks: Utilize predictive models such as ACI Equality 11-3 and 11-5 for shear force predictions, ensuring compatibility with AW-based materials [69,73].

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Expand the use of FEA for structural performance predictions, as it has been successfully applied to CS and banana fiber concrete beams [26,91].

- Calibration Factors: Introduce material-specific calibration factors to align experimental and theoretical predictions. For example, Vexp/VFEA ratios for palm kernel shell concretes highlight the need for adjustments [77].

III. Encourage Field Applications. Pilot projects are essential to validate experimental findings and assess real-world performance:

- Demonstration Projects: Encourage field trials for AW-based RC elements under varying climatic and loading conditions [73,88].

- Long-Term Monitoring: Implement monitoring programs for pilot projects to gather data on durability, cracking, and load-carrying behavior over time [74,84].

IV. Expand Regulatory Coverage. Standards must explicitly address the unique characteristics of AW materials:

- Material Specifications: Update standards like ACI 318 [72] and ASTM C330 [37] to include detailed specifications for bio-based materials, such as fiber content and aggregate replacement ratios.

- Performance Benchmarks: Establish benchmarks for properties such as ductility, energy dissipation, and cracking resistance, drawing from experimental findings [26,91].

- Seismic Considerations: Include provisions for displacement-based seismic design, leveraging findings on the ductility and energy absorption of AW-modified concretes [80,91].

V. Address Sustainability and Circular Economy Goals. Integrating AW into construction aligns with broader sustainability objectives:

- Life-Cycle Analysis: Mandate life-cycle assessments to quantify the environmental benefits of AW-based materials [22,77].

- Waste Management Strategies: Encourage policies that link waste management and construction industries to ensure a steady supply of AW for concrete production [83].

VI. Foster International Collaboration. A harmonized global approach can accelerate the adoption of AW materials:

- Collaborative Research: Establish international research initiatives to develop unified standards for AW-based concretes [34,71].

- Knowledge Sharing: Create platforms for sharing best practices, pilot project results, and calibration data across regions [73,84].

By adopting these recommendations, the construction industry can not only overcome the challenges associated with AW integration but also contribute to the development of sustainable and high-performance RC structures.

In addition to addressing regulatory gaps, it is crucial to explore the market incentives and barriers that influence the adoption of AW materials in construction practices.

- Incentives: The cost-effectiveness of AW materials, coupled with their environmental benefits, such as reduced carbon emissions and energy savings, presents significant opportunities for market adoption. For example, the use of CS concrete has been shown to reduce production costs by up to 20% compared to conventional aggregates [26,75]. Additionally, alignment with circular economy goals and sustainability targets encourages the use of alternative materials.

- Barriers: Despite these advantages, several challenges hinder market adoption. These include regional disparities in AW availability, high processing and transportation costs, and a lack of standardized economic evaluations. Furthermore, the absence of awareness and policies promoting the use of AWs limits their acceptance in mainstream construction practices.

- Future Directions: To overcome these barriers, future research should focus on developing comprehensive cost-benefit analyses, pilot projects for validating economic and technical feasibility, and policies that incentivize the use of AW materials in construction. Addressing these aspects will facilitate broader acceptance and scalability of AW-based concrete in the market.

5.5. Integration with Sustainability Goals

The integration of AW materials into RC elements aligns closely with global sustainability initiatives, addressing environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainable development. The following key points highlight how AW-based RC elements contribute to sustainability goals:

I. Reducing Carbon Footprint. The replacement of conventional materials with AW significantly reduces the carbon emissions associated with concrete production:

- Cement Reduction: AW ashes, such as WS and RHA, serve as supplementary cementitious materials, reducing clinker usage and CO₂ emissions [26,88].

- Lightweight Alternatives: Materials like PO shell aggregate and CS contribute to lightweight concrete production, reducing transportation emissions [69,73].

- Lifecycle Analysis: Lifecycle assessments of AW-modified concretes show reduced embodied energy and carbon footprints compared to conventional concrete [22,77].

II. Promoting Circular Economy. Integrating AW into construction promotes the circular economy by creating value from waste:

- Waste Valorization: Utilizing materials like palm kernel shells and banana fibers diverts significant amounts of AW from landfills [77,91].

- Resource Efficiency: AW enables resource-efficient practices by replacing non-renewable aggregates and reducing reliance on finite raw materials [80].

- Local Sourcing: Encouraging the use of locally available AW reduces supply chain emissions and supports regional economies [34,71].

III. Enhancing Energy Efficiency. AW materials improve the thermal performance of concrete structures:

- Thermal Insulation: Materials like PO shell foamed concrete exhibit superior thermal insulation properties, reducing energy consumption in buildings [69,73].

- Energy Absorption: Enhanced energy absorption capabilities of AW-based concretes contribute to sustainable structural design in seismic regions [84,91].

IV. Addressing Waste Management Challenges. Construction applications offer a practical solution for AW management:

- Volume Reduction: Large-scale use of AW in RC elements can significantly reduce AW volumes and related disposal issues [83].

- Policy Alignment: Integrating AW into construction supports zero-waste policies and broader environmental regulations [22,74].

V. Supporting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). AW-based RC elements contribute to several SDGs, including the following:

- Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): By enabling sustainable construction practices, AW materials promote greener urban development [26,88].

- Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production): The adoption of circular practices in construction aligns with responsible resource management [77,91].

- Goal 13 (Climate Action): Reduced carbon emissions and sustainable material use directly support climate change mitigation efforts [71].

VI. Economic and Social Benefits. The integration of AW materials creates economic opportunities and enhances social sustainability:

- Job Creation: The collection, processing, and use of AW materials generate employment opportunities in rural areas [34,77].

- Cost Savings: The availability and cost-effectiveness of AW materials offer economic advantages for construction projects [83].

- Community Engagement: Promoting the use of locally sourced waste materials fosters community involvement and strengthens regional economies [73,80].

By aligning AW-based RC elements with sustainability goals, the construction industry can play a pivotal role in reducing environmental impacts, promoting economic growth, and enhancing societal well-being. These efforts also support the industry’s transition towards a greener and more sustainable future. In addition to aligning with sustainability goals, the adoption of AW materials requires supportive policies and incentives to address market barriers and promote their widespread use in construction practices.

6. Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agro-Wastes

The integration of AWs into the construction industry provides multifaceted economic and environmental advantages. Particularly in developing countries, where resource affordability is a pressing issue, AWs offer a cost-effective alternative to conventional construction materials. For instance, concrete beams incorporating CSs can reduce production costs by 15–20% compared to traditional beams [26,69]. Additionally, the cost benefits of AW materials, such as CSs and PO fuel ash, are further detailed in Section 3 and Table 3, which highlight reductions in production costs for lightweight concrete. Additionally, adopting AWs in construction processes can lead to energy savings of up to 30%, potentially reducing fossil fuel consumption by millions of tons annually [6,70]. Substituting AWs for cement could mitigate approximately 0.9 tons of carbon dioxide emissions per ton of cement produced [6,77].

From an environmental perspective, the use of AWs addresses critical challenges in global waste management. With an estimated annual generation of 500 million tons of AW, utilizing even 10% of this amount could result in the recycling of 50 million tons of waste globally [71,80]. Substituting AWs for cement could mitigate approximately 0.9 tons of carbon dioxide emissions per ton of cement produced [6,77], as detailed in Section 3 and Table 3. These environmental benefits are further supported by Section 4 and Table 6, which demonstrate reductions in carbon footprints and energy consumption in structural applications of RC beams incorporating AW materials. PO shell concrete, for example, exhibits 30% lower density compared to traditional lightweight concrete, enhancing energy efficiency in construction [70,74]. Furthermore, thermal insulation properties of these materials have been shown to reduce building energy consumption by 20%, further minimizing carbon footprints and associated costs [6,72].

Social and sustainability benefits are also evident. Recycling and processing AWs locally could increase rural employment opportunities by approximately 15%, driving economic growth in underprivileged regions [79,91]. Materials like banana fibers and CSs, which are up to 80% recyclable, emerge as environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional aggregates. Moreover, AW-based construction materials reduce energy consumption by 10%, decreasing dependency on fossil fuels and encouraging a shift toward renewable energy sources [26,70].

Despite these significant advantages, there remains a lack of detailed comparative economic analysis for AW materials, particularly in lightweight and RC applications. While Section 4 and Table 6 provide insights into the structural performance of RC beams with AW materials, further studies are needed to evaluate their cost-effectiveness and economic scalability in diverse construction scenarios. While theoretical studies highlight potential cost reductions and energy savings, comprehensive cost-benefit evaluations under diverse conditions are limited. For example, while CS concrete is reported to reduce production costs by 15–20% [26,69], these claims often overlook the expenses associated with processing, transportation, and adaptation to existing construction methods. Additionally, regional disparities in the availability and quality of AWs can significantly influence their economic viability.

To strengthen the case for AW adoption in construction, future research should focus on detailed life-cycle cost analyses, incorporating factors such as waste processing costs, logistical challenges, and long-term economic impacts. Establishing standardized metrics for evaluating economic trade-offs will be essential to validate and scale the use of AW materials globally.

These considerations underscore the transformative potential of AWs. Beyond their immediate applications in construction, they serve as a catalyst for advancing circular economy initiatives, reducing environmental impacts, and unlocking economic opportunities in resource-constrained regions.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions. This study provided a comprehensive review of the use of agricultural wastes in RC elements. The findings highlight the following:

- Structural Performance: The use of agricultural wastes as aggregates or reinforcement materials in RC elements, especially beams, has demonstrated positive impacts on strength, ductility, and energy absorption. For instance, materials such as CSs and banana fibers have improved durability and optimized ductility behavior. However, these materials exhibit greater variability compared to conventional concrete materials.

- Economic and Environmental Benefits: Agricultural wastes reduce costs and contribute to environmental sustainability. These materials have the potential to lower carbon emissions, facilitate waste management, and enable energy savings.

- Lack of Standardization: The review revealed gaps in international standards related to the use of agricultural wastes in concrete structures. Existing standards need to be updated to encourage the adoption of these novel materials.

- Implementation Constraints: More data are needed on the mechanical performance and long-term durability of agricultural wastes. Additionally, the effects of these materials on mix design and homogeneity require further testing through practical field studies.

Recommendations.

- Research and Development (R&D): Experimental and theoretical studies aimed at optimizing the behavior of agricultural wastes in RC elements should be encouraged. Future research should focus on fire resistance, environmental impacts, and long-term durability.

- Standardization Efforts: New standards that include testing protocols and performance criteria for agricultural wastes in RC elements should be developed. Existing standards, such as ACI 318 and ASTM C330, should be revised to accommodate the specific needs of these materials.

- Field Applications: Pilot projects are critical for evaluating the performance of agricultural wastes in real-world structural conditions. Such projects can validate the applicability and scalability of these materials.

- Education and Awareness: Awareness campaigns should target the construction industry and local communities to promote the use of agricultural wastes. Developing countries, in particular, should be informed about the economic and environmental advantages of these materials.

- Alignment with Sustainability Goals: The integration of agricultural wastes into RC elements should align with circular economy principles and sustainability objectives. Strategies should include waste management practices and carbon reduction targets.

Overall Assessment.

- Challenges in Uniformity and Durability: Highlighted the variability in raw AW materials and its impact on mechanical performance and durability. The discussion emphasizes the importance of standardized processing methods to ensure uniformity and reliability under various environmental conditions.

- Environmental Impact and Lifecycle Analysis: Critically analyzed the potential of AWs to reduce costs and enhance environmental sustainability. The section underscores gaps in lifecycle assessments and the need for comprehensive studies on long-term ecological benefits.

- Economic Feasibility and Regional Challenges: Detailed the challenges related to the absence of international standards for AW usage in RC elements. Recommendations for addressing these gaps through innovative supply chain solutions and robust economic models were included.

The use of agricultural wastes in RC elements represents a promising innovation that not only enhances structural performance but also supports environmental sustainability. However, widespread adoption of these materials requires extensive research, regulatory updates, and practical applications. Future research should prioritize the assessment of corrosion resistance and long-term durability in AW-based RC. These studies are essential for ensuring the reliability of such structures, particularly under environmental challenges like chloride penetration and carbonation. Addressing these challenges through standardized test methods and lifecycle analyses will further validate the practical applicability of AW materials in RC. Future efforts should aim to establish these innovative materials as a norm in the construction industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and A.K.; methodology, H.K. and A.K.; software, H.K. and A.K.; validation, H.K. and A.K.; formal analysis, H.K. and A.K.; investigation, H.K. and A.K.; resources, H.K. and A.K.; data curation, H.K. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K. and A.K.; visualization, H.K. and A.K.; supervision, H.K. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Structural performance indicators (flexural tests) (own research).

Table A1.

Structural performance indicators (flexural tests) (own research).

| Ref. No. | Beam Specimen | Initial Shear Crack (kN) | Yield Shear Force (kN) | Ultimate Shear Force (kN) | Yield Displacement (mm) | Ultimate Displacement (mm) | Ductile Ratio (mm/mm) | Energy Absorption Capacity (kN-mm) | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | Conventional Concrete | 27.00 | 135.00 | 10.44 | 7.91 | 704.70 | |||

| Steel Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C1 | 36.00 | 149.00 | 12.67 | 7.28 | 943.91 | ||||

| Steel Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C2 | 38.00 | 153.00 | 15.87 | 8.40 | 1214.06 | ||||

| Steel Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C3 | 44.00 | 160.00 | 17.08 | 7.94 | 1366.40 | ||||

| Steel Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C4 | 41.00 | 156.00 | 16.97 | 8.20 | 1323.66 | ||||

| Lathe Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C1 | 33.00 | 138.00 | 12.60 | 7.37 | 869.40 | ||||

| Lathe Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C2 | 35.00 | 141.00 | 15.83 | 9.05 | 1116.02 | ||||

| Lathe Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C3 | 40.00 | 147.00 | 17.01 | 8.18 | 1250.24 | ||||

| Lathe Fiber Reinforced Wheat Straw Ash C4 | 38.00 | 144.00 | 16.89 | 9.13 | 1216.08 | ||||

| [22] | Control Concrete Beam | 11.50 | 68.00 | 2.90 | 2037.00 | ||||

| 25% Epoxy Adhesive + Palmiye Fuel Ash Beam | 17.80 | 119.50 | 4.85 | 3390.00 | |||||

| 25% Epoxy Adhesive + Normal Mortar Beam | 17.30 | 117.00 | 3.90 | 3370.00 | |||||

| 50% Epoxy Adhesive + Palmiye Fuel Ash Beam | 19.30 | 124.00 | 4.50 | 3560.00 | |||||

| 50% Epoxy Adhesive + Normal Mortar Beam | 18.80 | 119.00 | 4.25 | 3485.00 | |||||

| 75% Epoxy Adhesive + Palmiye Fuel Ash Beam | 20.60 | 127.00 | 4.05 | 3660.00 | |||||

| 75% Epoxy Adhesive + Normal Mortar Beam | 20.80 | 128.00 | 3.90 | 3520.00 | |||||

| 100% Epoxy Adhesive Prepared Beam | 25.80 | 130.50 | 3.35 | 3800.00 | |||||

| [26] | Coconut Aggregate Beam | 13.28 | 4.90 | 328.99 | |||||

| Coconut Shell + 0.25% Steel Fiber Beam | 13.88 | 4.30 | 362.70 | ||||||

| Coconut Shell + 0.50% Steel Fiber Beam | 14.90 | 3.70 | 394.84 | ||||||

| Coconut Shell + 0.75% Steel Fiber Beam | 15.67 | 3.50 | 420.29 | ||||||

| Coconut Shell + 1% Steel Fiber Beam | 17.04 | 3.20 | 476.13 | ||||||

| [69] | Shear Reinforced Palm Oil Shell Foamed Concrete | 12.00 | 40.00 | 47.10 | 14.90 | 50.00 | 3.40 | Local Yielding | |

| Shear Reinforced Palm Oil Shell Foamed Concrete | 12.00 | 32.00 | 46.70 | 15.00 | 63.00 | 4.20 | Bending | ||

| Shear Reinforced Normal Concrete | 12.00 | 31.00 | 51.10 | 13.70 | 35.00 | 2.60 | Bending | ||

| Shear Reinforced Normal Concrete | 14.00 | 30.00 | 48.80 | 14.00 | 25.00 | 1,80 | Bending | ||

| Palm Oil Shell Foamed Plain Concrete | 12.00 | 31.00 | 43.00 | 15.50 | 62.00 | 4.00 | Shearing/Anchoring | ||

| Palm Oil Shell Foamed Plain Concrete | 14.00 | 35.00 | 44.50 | 13.60 | 73.00 | 5.40 | Shearing/Anchoring | ||

| Normal Concrete Without Shear Reinforcement | 16.00 | 32.00 | 40.10 | 14.10 | 44.00 | 3.10 | Shearing | ||

| Normal Concrete Without Shear Reinforcement | 20.00 | 31.00 | 37.20 | 14.00 | 45.00 | 3.20 | Shearing/Anchoring | ||

| [70] | Palm Oil Shell Beam 1 | 9.05 kNm | 15.60 kNm | 11.40 | 70.15 | 6.15 | |||

| Palm Oil Shell Beam 2 | 10.80 kNm | 21.40 kNm | 11.70 | 71.15 | 6.08 | ||||

| Palm Oil Shell Beam 3 | 16.10 kNm | 32.20 kNm | 11.90 | 74.80 | 6.28 | ||||

| [71] * | Control Concrete Beam Section 1 | 7.43 | 0.0728 | ||||||

| Control Concrete Beam Section 2 | 5.74 | 0.0728 | |||||||

| Black Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 1 | 6.35 | 0.0905 | |||||||

| Black Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 2 | 6.56 | 0.0905 | |||||||

| Green Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 1 | 5.73 | 0.0978 | |||||||

| Green Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 2 | 5.04 | 0.0978 | |||||||

| Horse Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 1 | 4.83 | 0.0858 | |||||||

| Horse Gram Pod Ash Concrete Beam Section 2 | 5.36 | 0.0858 | |||||||

| Pigeon Pea Stalk Ash Concrete Beam Section 1 | 4.96 | 0.1088 | |||||||

| Pigeon Pea Stalk Ash Concrete Beam Section 2 | 5.07 | 0.1088 | |||||||

| [73] | Single Strengthened Beam CC (S1) | 9.17 | |||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam CC (S2) | 4.44 | ||||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam CC (S3) | 2.97 | ||||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam CSC (S1) | 4.35 | ||||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam CSC (S2) | 4.02 | ||||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam CSC (S3) | 4.50 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CC (D1) | 5.33 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CC (D2) | 7.47 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CC (D3) | 5.03 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CSC (D1) | 7.34 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CSC (D2) | 7.21 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam CSC (D3) | 5.00 | ||||||||

| [74] | Single Strengthened Beam (S1) | 4.34 | |||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam (S2) | 4.20 | ||||||||

| Single Strengthened Beam (S3) | 3.55 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam (D1) | 3.14 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam (D2) | 2.65 | ||||||||

| Double Strengthened Beam (D3) | 2.49 | ||||||||

| [75] | AD-3 ((a/d) = 3) | 23.00 | 27.50 | Shear Anchorage | |||||

| AD-1 ((a/d) = 1) | 16.00 | 19.50 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||

| WC-1 ((M-3) = 20.3 Mpa) | 13.00 | 21.50 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||

| WC-3 ((M-1) = 39.8 Mpa) | 14.00 | 25.00 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||

| SR-1 ((ρ) = 3.4) | 14.00 | 30.50 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||

| SR-3 ((ρ) = 0.3) | 7.00 | 12.50 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||

| AD/WC/SR-2 ((a/d) = 2; (M-1) = 31.5 Mpa; (ρ) = 1) | 10.00 | 23.00 | Shear Anchorage | ||||||