Abstract

Building bridges sustainably is essential for advancing infrastructure development and ensuring long-term environmental, social, and economic viability. This study presents a framework that integrates risk management strategies and Building Information Modeling (BIM) with Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) standards to enhance bridge project sustainability. Through a targeted survey, the study evaluates risks across bridge lifecycle phases, identifying the main processes that significantly impact sustainability. Using the Pareto Principle, the framework prioritizes these processes and associated risks, guiding the creation of targeted improvement guidelines aligned with ISO 9001:2015, BIM, and LCSA standards, which support high quality and efficiency. The results reveal that 38 of 55 identified risks account for 80% of the lifecycle impact, and they include the majority of those derived from international standards, underscoring their significance in sustainability efforts. Additionally, 36 of 47 main processes are subject to 80% of the impact from these vital risks, highlighting phases like Construction and Supervision as priority areas for intervention. By linking specific risks to each process within these phases, the study outlines essential guidelines and strategic measures, ensuring a focused approach to sustainable bridge development that aligns with international standards and maximizes lifecycle sustainability outcomes.

1. Introduction

Transportation networks are vital for societal welfare and economic growth, with bridges enabling the smooth movement of people and goods. The rise in bridge construction mirrors economic expansion and urbanization, highlighting their importance in modern infrastructure. Effective bridge management is crucial for achieving sustainable development goals, as emphasized by the Brundtland Commission [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. While bridges provide significant benefits, they also present environmental, economic, and societal challenges, including substantial CO2 emissions throughout their lifecycle. The increasing need for bridge restoration and construction, coupled with growing infrastructure demands and aging structures, underscores the importance of mitigating the risks that impact sustainability [16,17,18,19,20]. Global data highlight the scale and challenges of bridge infrastructure. In China, the number of road bridges grew from 658,100 in 2010 to 1,033,200 in 2022, a 57% increase. The U.S. has 617,000 bridges, 42% of which are over 50 years old, with 46,154 classified as structurally deficient, impacting millions of commuters. In Canada, 40% of roads and bridges are in fair or poor condition and need replacement. Meanwhile, Germany has significantly increased its spending on bridge development and renovation [3,13,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The large number of bridges places a maintenance burden on owners, industry, and governments, making economic factors more significant than environmental and social ones in bridge construction decisions. Recently, the World Bank allocated over 20% of its loans to transportation infrastructure. Understanding the greenhouse gas emissions from bridges is vital for future infrastructure planning. Additionally, the societal impact of these projects remains underexplored despite its importance to sustainability [9,11,21,26,27,28]. The continued use of conventional techniques in bridge projects, rather than modern technologies, exacerbates challenges. These projects are complex, involving advanced designs and difficult configurations that cannot be easily planned with 2D drawings alone. Fragmented information flow during a bridge’s lifespan raises repair costs and delays, impeding sustainable development. To achieve economic gains while protecting the environment and society, enterprises must adopt innovative approaches for comprehensive project management across the entire lifecycle [1,2,3,6,8,29,30].

To improve bridge sustainability by tackling these challenges, efficient methods like Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Lifecycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) are essential for effective management. These technologies aim to enhance planning, resource allocation, and integrate long-term sustainability in bridge projects. However, their implementation in bridge management has yet to meet expectations, based on the current state of their use [3,4]. BIM has been used in various aspects of bridge building to enhance design quality, foster collaboration, and improve feasibility through precise 3D models. It also improves coordination and efficiency throughout the bridge’s entire lifespan, from design to construction [4,8,31,32,33]. LCSA has been used in railway bridge construction to assess environmental impacts, particularly during the material production stage and across various environmental indicators. It highlights the importance of regular maintenance to reduce costs and ecological effects, underscoring LCSA’s role in managing materials and evaluating environmental impacts for sustainable infrastructure development [18,34,35,36,37,38,39].

After reviewing extensive studies on bridge projects, a multitude of risks impact each phase of these projects’ lifecycles. Given the complexity of bridge projects and their unique nature compared to traditional construction projects, traditional methods alone often fall short in effectively managing these risks, especially as the demand for achieving high levels of sustainability becomes increasingly essential. To address this, innovative approaches like Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) offer powerful solutions, as they provide critical insights and play essential roles in identifying, assessing, and mitigating a broad range of risks. However, the precise and accurate application of these approaches is crucial for their effectiveness, and alignment with ISO standards is one of the best ways to achieve this. These standards provide structured well-defined guidance that clarifies, simplifies, and organizes each process throughout the project lifecycle, ensuring that the integration of BIM and risk analysis with LCSA can be applied cohesively and effectively. Nevertheless, integrating these advanced tools and technologies to elevate sustainability levels in bridge projects is no simple task. It requires careful selection and prioritization of the most suitable methods and tools, beginning with the processes that have the highest impact on the bridge lifecycle. By strategically focusing on these critical areas and following a structured standards-based approach, bridge projects can maximize the benefits of modern technology, leading to enhanced resilience, efficiency, and sustainability.

Based on the previous information, this research aims to address the problem by formulating the following question:

How can the integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and risk management strategies with the Lifecycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) be utilized in bridge projects to enhance sustainability? Specifically, how can these tools aid in identifying, optimizing, and developing targeted guidelines and strategic measures for the most impactful processes, in alignment with ISO standards, throughout the bridge’s lifespan?

2. Literature Review

Through the research question posed, it is evident that several tools and techniques will be combined to enhance sustainability in bridge projects. The process will start with the analysis of risks across the bridge’s lifecycle, followed by Building Information Modeling (BIM), then linked with Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) in accordance with ISO standards. Furthermore, a guide will be developed in alignment with ISO 9001 specifications to outline the essential information that must be incorporated at each stage of the lifecycle, ensuring the achievement of sustainability across economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Accordingly, a literature review must be conducted regarding these elements, focusing on the following aspects.

2.1. Risks in Bridge Projects

Risk is defined as an event with known uncertainty, measured by its probability and severity of impact. It has the potential to significantly affect project outcomes, including cost, time, scope, and quality, and can be perceived individually or collectively, with both negative and positive impacts on project goals [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Often overlooked, risk and uncertainty play a crucial role in the sustainability challenge, particularly in economic analyses of sustainable development [50]. Risk management is essential to decision-making and is integrated into the structure, operations, and activities of an organization at strategic, operational, program, and project levels. It involves systematically applying rules, procedures, and practices to communication, context definition, risk assessment, treatment, monitoring, review, and reporting. Researchers classify risks as internal, external, environmental, economic, social, financial, market, safety risks, etc., which vary by project size, type, and scope. Effective risk management is vital to mitigating these risks and achieving time, cost, quality, safety, and environmental sustainability goals. It enables project teams to make timely decisions by identifying, classifying, quantifying, managing, and controlling risks, balancing the effort to manage risks with the resulting benefits in a cost–benefit analysis to maximize project value [41,42,44,48,49,51,52].

The complexity of bridge projects exposes them to a wide range of interconnected risks that significantly impact project lifecycles. Numerous studies have highlighted these risks, categorizing them into different categories that influence project success. A systematic review of 26 studies identified key risks in bridge projects that can be mitigated or managed using Building Information Modeling (BIM), grouping them into environmental, economic, and social categories. Common challenges include information management, document automation, structural maintenance, and resource allocation throughout the bridge project. Environmental risks involve selecting climate-appropriate eco-friendly materials and managing carbon footprints. Economic risks encompass communication gaps, inaccuracies in cost and schedule planning, and inefficiencies in execution monitoring. Additional economic challenges include supply chain disruptions, productivity issues, and organizational problems. Social risks cover safety evaluations, community engagement, and team organization [4]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 21 studies on bridge projects in China found that safety risk factors often stem from interconnected sources, including environmental conditions, materials, technical aspects, management practices, and personnel. Environmental risks, such as extreme weather and natural disasters, can disrupt construction. Technical risks are related to design flaws and construction errors, while management risks stem from poor planning and inadequate oversight. Personnel risks impact project outcomes through safety and skill level issues, while bridge-specific risks require tailored management strategies to ensure safety and functionality [53]. Additionally, a study analyzing 23 papers identified risks categorized as internal (project-specific challenges like environmental and management practices) and external (broader factors like natural hazards and economic impacts). The analysis covered environmental, economic, and social impacts on communities, stakeholder satisfaction, and structural adequacy under varied conditions. Other highlighted risks include natural hazards, political threats, congestion, land acquisition issues, and internal management conflicts. This research underscores the need for comprehensive risk management strategies to address the diverse and interconnected risks in bridge projects [54]. By integrating comprehensive risk management strategies, project teams can make informed decisions that enhance safety, optimize resources, and ensure the successful delivery of bridge projects. Recognizing the critical role of these studies is essential to developing resilient and sustainable infrastructure that meets both current and future demands.

2.2. Application of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Bridge Projects

Building Information Modeling (BIM), as defined by Autodesk, is the process of creating and managing information for a built asset using an intelligent model and a cloud platform, integrating multidisciplinary data throughout the asset’s lifecycle—from planning to operations. Pioneered by Chuck Eastman, BIM has evolved into a comprehensive methodology encompassing product representation, collaboration, and lifecycle management, widely adopted for its benefit to project stakeholders [1,55,56,57,58]. BIM has advanced significantly in global engineering construction, covering the entire project lifecycle, including quality control, cost management, scheduling, data handling, clash detection, and maintenance simulations through 3D data models. Integrating BIM into information frameworks reduces costs, enhances visualization, ensures data accuracy, and improves project integration. A Stanford University study found that BIM use can lead to a 40% reduction in change orders, a 10% decrease in contract costs, and a 7% reduction in project durations. However, widespread BIM adoption faces challenges in countries like the UK, Canada, the US, China, South Africa, Ghana, Australia, and India, including financial constraints, cost–benefit concerns, resistance to new practices, and legal issues. Additionally, BIM’s use in operations and maintenance is limited due to stakeholders’ lack of understanding and integration challenges with traditional contracting methods. Thus, a comprehensive study of BIM’s practical applications in construction is necessary to fully explore its benefits and challenges [5,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. BIM is an emerging technology in bridge construction that enhances design quality, collaboration, and feasibility through precise 3D models [5,29,69]. The ISO 19650 standard guides its implementation, aligning with UK 1192 standards and the UK BIM Framework to manage information efficiently throughout a building asset’s lifecycle [70,71,72]. Studies highlight BIM’s role in improving infrastructure, particularly in complex bridge projects requiring high accuracy. A key strategy for advancing bridge management with BIM is to use a specialized information schema that boosts coordination and efficiency across all stages of a bridge’s lifecycle, from design to construction [29]. A strategic plan for implementing BIM in bridge projects includes identifying BIM applications at various project stages, designing processes with process maps, defining BIM deliverables through information exchanges, and establishing connections to support implementation. A Bridge Information Modeling (BrIM) framework has also been developed, integrating features from Bridge Management Systems (BMS), such as databases, inspection modules, and condition assessment tools. This framework aims to build a comprehensive bridge component database, generate inspection spreadsheets, and enhance time and cost management by automating cost estimation and performance measurement during project execution [31,32,33]. Bridge projects have developed various BIM-based solutions to enhance design and construction efficiency, with a focus on design phases, construction sequences, and process monitoring. One conceptual framework integrates BIM with advanced imaging and computation technologies to enhance asset management. To optimize maintenance, a visual framework assesses the condition of concrete bridge elements, and structural assessments use BIM-IoT strategies. Furthermore, studies have highlighted the enhancement of bridge management systems by integrating Geographic Information Systems (GIS). In order to deepen understanding of BIM’s potential impact on the industry, further research is necessary to achieve more precise and reliable outcomes, as these efforts advance BIM applications in bridge construction and management [8,13,15,72,73,74]. The integration of BIM with the Internet of Things (IoT), Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and data analytics has expanded its role in bridge management systems. These technologies facilitate continuous data monitoring, informed decision-making, predictive maintenance, and improved operational efficiency in bridge management [37,75,76,77]. Researchers have extensively studied BIM applications to improve bridge construction, but more research is necessary to attain more accurate and dependable results. This effort aims to fully understand the technology’s capabilities and its potential to advance the industry.

2.3. Application of Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) in Bridge Projects

The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) defines sustainability as a global goal comprising environmental, economic, and social dimensions. The growing emphasis on sustainability has led to the development of the Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), a comprehensive approach that evaluates the full range of environmental, social, and economic impacts of products. Introduced over 15 years ago, LCSA integrates Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (E-LCA), Life Cycle Costing (LCC), and Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) based on standards like ISO 14044, ISO 14040, ISO 14047-ISO 14049, ISO 15663, and ISO 14072. Aligning with triple-bottom-line theory, LCSA supports sustainable decision-making across a product’s life cycle. Zhou first presented the term “LCSA” in 2007 and Kloepffer further developed it in 2008, marking a significant advancement in sustainability assessment [7,58,78,79,80,81,82,83]. The field of LCSA is continually evolving, with ongoing efforts to refine its framework and methods to more accurately measure sustainability. LCSA’s broad applicability spans industries such as construction, transportation, manufacturing, energy, and agriculture, aiming to promote a Circular Economy (CE), which emphasizes sharing, reusing, repairing, and recycling resources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and extend material lifespans. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) assesses environmental impacts within specific system boundaries, while Life Cycle Costing (LCC) addresses economic aspects, ensuring accurate cost planning throughout a product’s lifecycle. The addition of the Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) broadens LCSA by evaluating the social impacts on stakeholders at various levels. While LCSA still requires further development to enhance its applicability, it plays a critical role in advancing a sustainable economy by integrating sustainability with economic and social considerations, aiding informed decision-making in design and construction projects [7,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

In bridge projects, LCSA has evolved from managing material life cycles to analyzing environmental impacts and maintenance challenges. Initially, LCSA focused on comparing the lifespans of standard and minimal-girder bridges through steel durability tests to enhance performance. Further developments included evaluating conventional versus alternative materials for bridge decks to extend their lifespan and reduce maintenance needs [34,60]. The scope of LCSA has expanded to evaluate the environmental impacts of railway bridge construction, highlighting the significant effects of material production. Comprehensive assessments have measured the environmental impacts of various bridge activities and components using diverse environmental indicators. Studies on completed bridges have shown that material manufacturing and operation stages are major contributors to environmental impacts. Exercise-based Life Cycle Assessment has provided insights into the environmental sustainability of bridges, especially in critical stages like raw material manufacturing and processing [18,36,37,38]. Regular bridge maintenance is critical for reducing costs and minimizing environmental impacts, compared to the higher investments and environmental consequences of irregular maintenance. In bridge projects, LCSA encompasses material management, environmental impact analysis, and maintenance considerations to promote sustainable infrastructure development [39]. Several studies have combined Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Costing (LCC) to better manage environmental impacts and costs in bridge maintenance. A genetic algorithm-based framework was developed to optimize bridge maintenance, focusing on maximizing safety, minimizing costs, and reducing environmental effects. Multiple bridge projects employed life-cycle cost analysis to assess the cost-effectiveness of various alternatives, such as reinforcement bars, while taking environmental and climate factors into account. A method was developed to assess the ecological impacts and costs of maintaining concrete bridge structures throughout their lifespan, particularly focusing on repair and maintenance activities. The integration of LCA in preventive maintenance and bridge management is essential, especially in steel-concrete composite bridge design, making environmental LCA a key tool in bridge project management [91,92,93,94]. Bridge project management commonly uses environmental Life Cycle Assessment, but there is still limited implementation of social life cycle evaluation. To fully integrate all aspects of life cycle sustainability assessment into bridge management practices, further research is necessary.

2.4. Quality Management System (ISO 9001:2015)

ISO 9001:2015 is a globally recognized management system that can be applied in all types of companies, regardless of size or sector, to ensure quality and improve performance through top management’s implementation. This standard defines the requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining, and continually improving a quality management system (QMS), helping organizations demonstrate their commitment to quality, meet customer expectations, and comply with legal requirements. By putting in place effective processes and training staff, companies can consistently deliver flawless products or services [95]. The standard has evolved through several stages to reach its current form. The International Organization for Standardization issued the first quality assurance standard, ISO 9000, based on the British Standard BS 5750. The second edition, ISO 9000, appeared in 1994, followed by ISO 9001 in 2000, which replaced the 1994 version. The fourth edition, ISO 9001:2008, replaced previous versions in 2008 [95,96], and the latest version, ISO 9001:2015, was released in October 2015 and remains in use, with the final modification in 2024 addressing climate action change. So, companies must implement and comply with the ISO 9001:2015 standard, which is divided into 10 main clauses and 28 sub-clauses, as follows [96]:

- -

- Clause 1 describes the scope;

- -

- Clause 2 covers references;

- -

- Clause 3 deals with terms and definitions;

- -

- Clause 4 pertains to the context of the organization, which includes understanding the organization and its surroundings, comprehending the requirements and expectations of stakeholders, determining the scope of the quality management system, and evaluating the system and its processes;

- -

- Clause 5 discusses leadership, including leadership and commitment, quality policy, organizational roles, responsibilities, and authorities;

- -

- Clause 6 focuses on planning for the quality management system, including actions to address risks and opportunities, quality objectives, planning to achieve them, and planning for changes;

- -

- Clause 7 deals with support, including resources, competence, awareness, communication, and documented information;

- -

- Clause 8 focuses on operations, including operational planning and control, requirements for products and services, design and development, control of externally provided processes, products, and services, production and service provision, release of products and services, and control of nonconforming outputs, products, and services;

- -

- Clause 9 covers performance evaluation, including monitoring, measurement, analysis, evaluation, internal audit, and management review;

- -

- Clause 10 addresses improvement, including general improvement, nonconformity, corrective action, and continual improvement.

The required controls for each clause of the standard have been defined, but the specific methods are not prescribed, as they depend on the company’s management system and the unique nature of its business to establish and maintain documented procedures ensuring compliance with the requirements. Proper application of this standard provides companies with a comprehensive internal management system, ensuring numerous internal benefits, enhancing their competitive position, increasing market share, and offering other desired external advantages.

In conclusion, integrating risk management, Building Information Modeling (BIM), Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), and ISO standards are essential for enhancing sustainability in bridge projects. Risk management identifies and mitigates potential impacts across the bridge lifecycle, supporting project teams in maintaining time, cost, and quality objectives while addressing environmental, economic, and social sustainability. BIM enables precise 3D modeling, data management, and collaboration across project stages, while its integration with LCSA ensures that environmental and social impacts are continuously assessed. LCSA offers a comprehensive view of sustainability by evaluating environmental, economic, and social impacts and promoting informed sustainable decision-making. Lastly, ISO 9001 offers a structured quality management framework that facilitates the consistent application of these tools, guaranteeing the organization, optimization, and alignment of all processes with sustainability goals throughout the bridge project lifecycle.

While ISO 9001:2015, BIM, and LCSA standards provide robust frameworks, their application to bridge projects in diverse regions presents unique challenges. Limited infrastructure, resource constraints, and varying regulatory requirements may hinder seamless adoption. For instance, the high cost and training requirements for BIM implementation pose significant barriers in less-developed contexts. Similarly, the availability of reliable environmental data affects the accuracy of LCSA analyses. To address these challenges, the proposed framework in this paper serves as a foundation that can be adapted to regional contexts, integrating local practices and data into its process.

3. Methodology

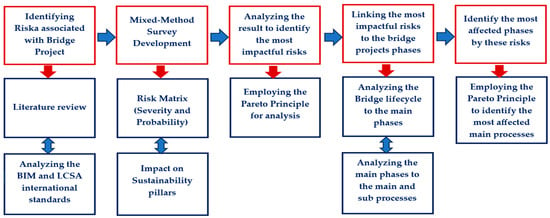

To address the previously mentioned research inquiries, the following methodology, shown in Figure 1, was employed:

Figure 1.

Research methodology.

3.1. Identifying Significant Risks Associated with Bridge Projects

To achieve the objectives of this research and enhance the sustainability of bridge projects, it is essential to begin with a comprehensive analysis of the potential risks that may arise. This process involves identifying the most significant risks from the perspective of the stakeholders involved in these projects. Two key phases led to the identification of risks associated with bridge projects. First, a thorough review of existing research was conducted to gather and categorize relevant risks. This review provided the foundational data needed for classifying and assessing risks. The second phase focused on an in-depth examination of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) international standards. Standards often encompass both tangible and intangible risks, assuming effective management of these risks once included within the framework. However, this approach ignores the need to accurately assess the implementation of the standards. Therefore, simply recognizing risks within standards is insufficient and does not guarantee their effectiveness or mitigation. Bridge projects apply broader standards related to construction, information management (BIM), and life cycle sustainability (LCSA), despite the absence of specific international standards for bridges. Standards like ISO 19650 and ISO 14040 offer broad guidelines tailored to the unique requirements of bridge design, construction, and sustainability. This analysis aimed to identify the sustainability requirements across environmental, economic, and social domains and to identify potential risks that could arise from the improper implementation of these standards.

The literature review [4,5,53,54,58,59,60,61,62,63,97,98,99,100,101] initially identified 41 potential risks to bridge projects. To deepen this analysis, international standards presented in Table 1 and Table 2 were examined. The results, shown in Table 3 and Table 4, show the sustainability requirements and risks that come from ISO 19650-1:2018 and ISO 19650-2:2018 (BIM standards). Table 5 and Table 6 show the results that come from ISO 14040:2006 and ISO 14044:2006 (LCSA standards). This method was systematically applied across all relevant standards. The result is a comprehensive list of 55 risks pertinent to bridge projects. These risks will undergo further evaluation through a mixed-method survey approach.

Table 1.

BIM international standards.

Table 2.

LCSA international standards.

Table 3.

Sustainability requirements and associated risks from ISO 19650-1:2018.

Table 4.

Sustainability requirements and associated risks from ISO 19650-2:2018.

Table 5.

Sustainability requirements and associated risks from ISO 14040:2006.

Table 6.

Sustainability requirements and associated risks from ISO 14044:2006.

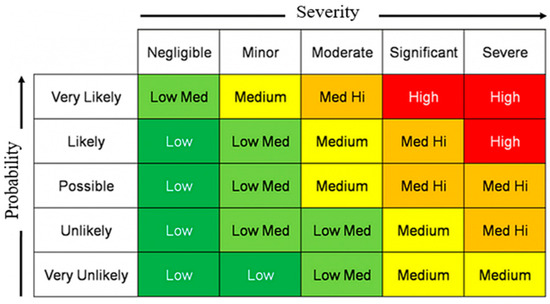

3.2. Mixed-Method Survey Development

To thoroughly evaluate the risks identified in the previous analysis, a mixed-method survey was designed with three key components for assessment. The first section gathers respondent information, including their background and familiarity with core concepts relevant to this research, such as BIM, LCSA, and ISO international standards. The second section focuses on the 55 identified risks, each linked to phases of the bridge project lifecycle and evaluated through two distinct lenses. The first lens assesses each risk against the three sustainability pillars (environmental, economic, and social), using a scale of Low, Moderate, and High. The second lens is shown in Figure 2, it uses a risk matrix to figure out the severity and likelihood of each risk’s possible effect on the project as a whole, not just one part of it. For this assessment, respondents use a five-point Likert scale to indicate their view on probability (1—Very Unlikely, 2—Unlikely, 3—Possible, 4—Likely, 5—Very Likely) and severity (1—Negligible, 2—Minor, 3—Moderate, 4—Significant, 5—Severe) for each risk. The final section includes an open-ended question, inviting respondents to identify any additional risks not mentioned in the survey and to assess these using the same methods.

Figure 2.

Example of a risk matrix.

A total of 75 surveys were distributed to professionals specializing in various types of bridge projects in different countries, such as Syria, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands. Of these, 41 complete surveys were returned and deemed suitable for analysis. These responses were used to evaluate the risks affecting the lifecycle of bridge projects.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the survey data, several measures were implemented. Strict inclusion criteria, targeting professionals with significant experience in bridge project management, risk assessment, and sustainability practices, guided the selection of respondents. The participant pool represented diverse geographic regions, with approximately 56.2% from Europe, 29.4% from the Gulf States, and 14.4% from the Middle East, ensuring a balance of perspectives across developed and less-developed contexts. These experts held roles such as bridge engineers, project managers, and sustainability analysts, with an average of 10 years of professional experience.

The survey was pilot-tested with a small group of experts to refine question clarity and eliminate potential biases. Measures such as randomizing question order and ensuring respondent anonymity were also employed to minimize response bias. Responses were reviewed for completeness and consistency, and ambiguous or incomplete entries were excluded from the analysis. This rigorous approach ensured the survey captured diverse insights while aligning the results with international standards.

3.3. The Results of the Survey

Table 7 illustrates the analysis of the survey respondents’ data, which involved calculating the average of each risk’s severity (S) and probability (P) and then determining the overall risk impact (RI). The total risk impact is calculated by multiplying the risk severity by the risk probability. Additionally, the average identifies the three sustainability pillars, environmental (EN), economic (EC), and social (SO), for later use in determining the necessary data to develop essential guidelines for the targeted processes. Also, in reviewing the data, distinct trends emerge based on geographical location, economic conditions, and technological infrastructure. Experts from Middle Eastern countries, such as UAE and Saudi Arabia, generally perceive environmental and resource-related risks as higher, likely due to regional climate challenges and resource-intensive construction processes. In contrast, countries like Syria exhibit heightened concerns about both economic and political stability, which may impact project continuity and increase overall project risk. European nations like Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands, with strong economic and political stability, reflect lower risk ratings in these areas. These countries benefit from advanced technological infrastructures, allowing them to integrate cutting-edge tools and processes, such as BIM and lifecycle sustainability assessments, more effectively. Their emphasis is often on optimizing resource management and minimizing environmental impacts, as these countries are typically more technologically prepared and have established sustainability practices within their infrastructure projects.

Table 7.

The result of the risk evaluation (risks in red from the international standards).

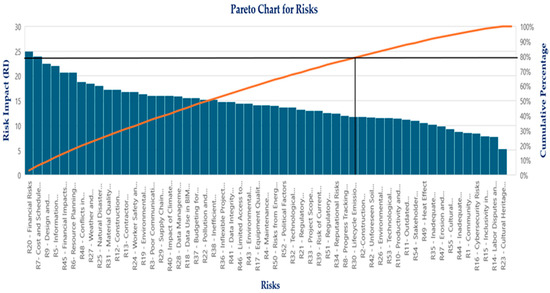

To effectively address these risks, it is essential to focus on those with the greatest impact on the bridge lifecycle. By applying the Pareto principle, which typically suggests that 20% of causes are often responsible for 80% of the effects, to the survey results, Table 8 has been organized to include all necessary data for creating a Pareto chart. This chart enables the identification of the critical 20% of risks that contribute to 80% of the impact on sustainability throughout the bridge project lifecycle.

Table 8.

The required data for the Pareto chart for risks.

The results from Table 8 and Figure 3 illustrate the application of the Pareto principle, showing that the most critical risks—those that collectively account for 80% of the impact on the bridge project lifecycle—are concentrated on the left side of the chart, specifically from R20 to R30, totaling 38 risks. Notably, most of the risks identified based on international standards fall within this range. This finding deviates from the typical Pareto distribution, where approximately 20% of causes account for 80% of effects. Instead, these risks affect a larger proportion of processes, reflecting the complex and interconnected nature of risks in bridge projects. While achieving a strict 80/20 distribution was not feasible due to the broader distribution of significant risks across processes, the Pareto Principle served as a valuable tool to prioritize and rank risks systematically. By ranking risks in descending order of importance, the proposed framework enables stakeholders to focus resources on higher-priority risks while retaining a comprehensive understanding of lower-tier risks that may influence specific phases or contexts.

Figure 3.

Pareto chart for risks.

This broader interpretation of the Pareto Principle may reflect the unique complexities of bridge projects, where risks are often interconnected and require a more comprehensive evaluation. While this adaptation deviates from traditional applications, it ensures that no significant risks are overlooked while allowing for tailored prioritization based on specific project contexts. This adapted approach to the Pareto Principle ensures a flexible and actionable framework, allowing project teams to address the most critical risks first while maintaining adaptability for diverse project contexts. The next step involves linking these vital risks to the processes within each phase of the bridge lifecycle.

3.4. Linking the Risks to the Processes of a Bridge Project Lifecycle

This step involves segmenting the bridge lifecycle into eight primary phases—Planning and Design, Procurement and Contracting, Construction and Supervision, Testing and Commissioning, Operation, Maintenance, Rehabilitation, and Decommissioning. Each phase is further detailed into its main processes and subprocesses. This structure is informed by an extensive review of previous studies, guidance from the PMBOK Guide, 7th Edition, and insights from bridge professionals. Relevant risks are then mapped to each subprocess to provide a comprehensive view of how these risks impact each main process and, consequently, the broader project lifecycle. To ensure objectivity and consistency, the following systematic approach was implemented:

- 1-

- Risk-Process Relevance Assessment: For each subprocess, the nature of the task was analyzed, and the critical aspects or objectives that each subprocess aims to achieve were identified (e.g., accuracy in financial analysis for cost–benefit analysis or environmental protection in Environmental Impact Assessment). Each risk from the vital list was then reviewed to determine how it might impact or threaten these specific objectives of the subprocesses. This ensured that risks were only assigned to subprocesses where their influence was logically relevant and significant;

- 2-

- Risk Impact Analysis: Each risk’s potential to directly or indirectly influence the success of each subprocess was evaluated. Both direct risks (those impacting subprocess outcomes directly) and indirect risks (those affecting resources, scheduling, stakeholder engagement, or other supportive aspects) were considered. For instance, financial risks (R20) were inherently linked to processes like cost–benefit analysis and budgeting, as these risks directly affect financial stability and planning. Similarly, Environmental Compliance Risks (R43) and Pollution and Waste Management Issues (R22) were linked to Environmental Impact Assessments due to their direct relationship with assessing and mitigating environmental impacts;

- 3-

- Cross-Referencing for Completeness: The scope of each risk was used to cross-check its relevance to multiple subprocesses where applicable. For example, Project Scope Creep (R33), while directly impacting budgeting, was also found to affect traffic and demand analysis and cost–benefit analysis due to potential misalignments between scope and demand or budget. This ensured comprehensive coverage of risks across all applicable subprocesses;

- 4-

- Risk-Context Matching: Each risk was matched to its specific context within the project lifecycle phase to ensure relevance and clarity. For example, ’Supply Chain Disruptions’ (R29), while primarily associated with Procurement and Construction, was also linked to Maintenance because disruptions in the availability of replacement parts or materials could affect maintenance schedules and outcomes. Worker safety and health risks (R24) were linked to site selection due to the potential safety hazards of certain locations, while data management challenges (R28) were linked to traffic and demand analysis because of the data-intensive nature of these analyses. Similarly, Lifecycle Emission Assessment Issues (R30) were primarily linked to the Planning and Construction phases, where material selection and operational planning directly influence emissions. However, limited relevance was also noted for the Maintenance and Decommissioning phases to account for emissions generated during maintenance activities and end-of-life processes, such as demolition and material recycling. Some risks, such as Information Management Issues (R5) and Data Management Challenges (R28), may appear similar but were linked to different phases to reflect their distinct roles. For instance, (R5) pertains to challenges in organizing and accessing data during early project phases like Planning and Design, whereas R28 emphasizes interoperability and integration issues that arise during collaborative phases such as Operation and Maintenance. Also, Resource Planning Issues (R6) focus on inefficiencies in resource allocation during early phases like Procurement, while Inefficient Resource Utilization (R38) highlights suboptimal use of resources during later phases like Construction and Operation. This differentiation ensures that risks are mapped to their most relevant contexts, avoiding redundancy while providing actionable insights for targeted mitigation;

- 5-

- Final Validation for Accuracy and Completeness: After risks were assigned, each linkage was reviewed and validated by industry professionals with expertise in bridge lifecycle management. This step ensured that the assignments were practical, consistent, and reflective of real-world conditions, with particular attention given to critical subprocesses such as geotechnical studies, which involve complex conditions and require consideration of various risk factors (e.g., climate, geology, and technology).

A systematic prioritization process was employed to ensure that risks with the highest potential impact, either directly or indirectly, were given precedence in the analysis. This prioritization aligns with the Pareto Principle, focusing resources on the vital risks that significantly influence project outcomes.

The assignment of risks to multiple phases reflects the interconnected nature of processes in bridge projects. The degree of impact of each risk varies across phases depending on its relevance and intensity in each context. For instance, while ’Natural Disaster Risks’ (R25) and ’Impact of Climate Change’ (R40) have significant direct impacts during the Construction phase due to potential disruptions or material vulnerabilities, they may have indirect or limited effects in the Maintenance or Decommissioning phases. Furthermore, risks like ’Supply Chain Disruptions’ (R29) are critical during Procurement and Construction but are less likely to impact the operation phase. This variability reflects the practical dynamics of risk influence and was considered in the analysis to ensure a nuanced understanding of their relevance to each phase. Such a context-dependent approach ensures that the framework remains adaptable to diverse scenarios and enables a more precise understanding of risk distribution across the bridge lifecycle.

While this methodology provides a structured and consistent approach to risk mapping, it should be recognized that evolving project contexts or unforeseen factors may influence the relative importance of certain risks, necessitating periodic re-evaluation.

Table 9 and Table 10 illustrate the application of this methodology to the Planning And Design as well as Procurement And Contracting phases of the bridge lifecycle.

Table 9.

The analysis of the planning and design phase and its associated risks.

Table 10.

The analysis of the Procurement and Contracting phase and its associated risks.

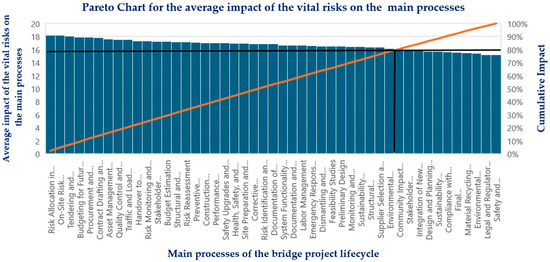

After the outlined methodology was applied across all phases of the bridge lifecycle, the total number of risks from the vital risks list associated with each subprocess was identified, allowing for the calculation of risks related to each main process, which made it possible to calculate the average impact of vital risks affecting each main process. Then, the Pareto Principle was subsequently applied to the bridge lifecycle phases through the average impact of the vital risks that affected each main process. This approach pinpointed the most impactful processes within each phase of the bridge project lifecycle, enabling targeted improvements in these areas. Table 11 presents the data needed to create the Pareto chart for the bridge lifecycle phases: Planning and Design (P&D), Procurement and Contracting (P&C), Construction and Supervision (C&S), Testing and Commissioning (T&C), Operation (O), Maintenance (M), Rehabilitation and Retrofit (R&R), and Decommissioning and End-of-Life (D&E).

Table 11.

The required data for the Pareto chart for the bridge lifecycle phases.

The identified vital risks significantly influence 36 out of 47 main processes, as Table 11 and Figure 4 demonstrate. Applying the Pareto Principle enabled a strategic prioritization of processes, focusing efforts on those most impacted by risks to develop targeted mitigation plans. This prioritization emphasizes that the most effective way to manage critical risks in the bridge lifecycle is by prioritizing processes based on their cumulative risk impact. For instance, focusing on the process with the highest impact—risk allocation in contracts during the Procurement And Contracting phase—and utilizing precise risk management tools can establish a strong foundation that positively impacts other processes. Eleven vital risks (R3, R6, R9, R13, R20, R29, R41, R43, R45, R48, and R52) affect this process alone, underscoring the substantial impact that effective risk mitigation can have on the overall project.

Figure 4.

Pareto chart for the average impact of the vital risks on the main processes.

Applying this systematic approach to other high-impact processes within the “vital zone” of the analysis chart offers a powerful opportunity to enhance sustainability throughout the bridge lifecycle. By effectively managing these prioritized processes and addressing associated risks, significant improvements can be achieved in environmental, economic, and social sustainability. This focused approach not only optimizes the use of resources but also ensures the development of robust, enduring bridge infrastructure that aligns with comprehensive sustainability objectives. Finally, Table 12 presents the percentage distribution of affected phases in the bridge project lifecycle impacted by the vital risks.

Table 12.

The percentage of the affected phases by the vital risks in the bridge project lifecycle according to the Pareto Principle.

Analyzing the results in Table 12 reveals the following insights:

- 1-

- High-Risk Phases: The Construction and Supervision phase is notably high-risk, with 100% of its main processes affected by vital risks. This result indicates that every aspect of this phase requires close management due to the dynamic nature of on-site activities, resource demands, and regulatory compliance. Additionally, the procurement and contracting, operation, and maintenance phases each have 83.33% of their processes impacted by vital risks. The significant risk exposure during these phases shows the necessity for effective risk management measures;

- 2-

- Phases Affected Moderately: Each of the Planning and Design as well as Testing and Commissioning phases exhibit 80% process impact, emphasizing the criticality of early risk mitigation during these foundational stages. The rehabilitation and retrofit phase affects 60% of processes, indicating a concentration of vital risks in specific areas, likely due to its narrower scope compared to other phases like construction and maintenance;

- 3-

- Lower-Risk Phase: The decommissioning and end-of-life phase shows the lowest percentage of affected processes, with only 33.33% impacted. This lower percentage suggests that this phase, being terminal, involves fewer operational or construction-related risks.

Vital risks impact 36 out of 47 main processes across all phases, accounting for 76.6% of the total. This high proportion of affected processes indicates that vital risks substantially influence the entire bridge lifecycle, illustrating the need for a comprehensive approach to risk management. Prioritizing high-risk phases such as Construction and Supervision, procurement, operation, and maintenance would yield substantial improvements in risk mitigation. Additionally, focusing on the main processes within planning and design, testing, and commissioning can help manage risks early in the lifecycle, contributing to better outcomes across the project, and commissioning can help manage risks early in the lifecycle, leading to better outcomes across the project.

3.5. Developing the Essential Guidelines and Strategic Measures

Based on the previous results, the ideal starting point for developing essential guidelines and strategic measures is to focus on the high-impact processes within the Construction and Supervision phase. This phase is critical, with 100% of its main processes affected by vital risks. Key areas, such as on-site risk management, quality control and assurance, and health, safety, and environment (HSE) management, should be prioritized, as they directly impact project safety, quality, and regulatory compliance. Establishing guidelines in these areas will lay a strong foundation for risk management, creating positive effects that resonate throughout the entire project.

Each main process within this phase should develop essential guidelines and strategic measures to achieve targeted improvements and mitigate vital risks affecting its processes. These measures should specifically address the identified risks while aligning with the ISO 9001:2015 international standards. This alignment ensures high-quality performance, continuous improvement, and precise results. Additionally, the guidelines must integrate considerations for the sustainability pillars impacted by these risks, incorporating the necessary requirements to enhance process efficiency and outcomes. The survey results from Table 5 provide valuable insights for assessing the impact of these risks on the sustainability pillars. Applying the Pareto Principle to both risks and processes reveals the influence of 28 vital risks on the Construction and Supervision phase. These risks have a significant impact on both the main processes and subprocesses within this phase, as illustrated in Table 13.

Table 13.

The most impactful risks in the Construction and Supervision phase.

The analysis of Table 13 indicates that many of the identified risks in the Construction and Supervision phase significantly impact the economic sustainability pillar, making it a primary focus for this phase. Risks such as R20—financial risks, R7—cost and schedule planning issues, and R45—financial impacts from design changes are characterized by their high economic impact, underscoring the importance of financial viability in maintaining project continuity and preventing budget overruns. However, economic considerations alone are not sufficient; environmental and social sustainability must also be prioritized to achieve a balanced and sustainable project outcome. Environmental sustainability in this phase is critical for mitigating potential ecological risks, ensuring compliance with environmental regulations, and promoting long-term project viability. Risks such as R19—Environmental Impact Assessments, R22—Pollution and Waste Management Issues, and R43—Environmental Compliance Risks highlight the need for integrating environmental considerations into construction practices. Effective monitoring systems and sustainable construction practices should be implemented to minimize ecological impacts and ensure adherence to environmental standards. Social sustainability also plays an essential role in the Construction and Supervision phase, focusing on worker safety, community engagement, and stakeholder communication. Worker safety and health risks (R24) must be addressed through robust health, safety, and environment (HSE) management systems to ensure the well-being of workers and prevent accidents. Similarly, risks such as R3—poor communication and stakeholder engagement—emphasize the importance of involving stakeholders and maintaining open communication to align construction activities with community values and safety needs. An integrated approach that considers all three pillars of sustainability—economic, environmental, and social—is essential in the Construction and Supervision phase. While economic viability is critical, it must be pursued alongside environmental protection and social responsibility. Improvement guidelines should be developed to enhance not only economic outcomes but also environmental and social aspects. This can be achieved by incorporating sustainability criteria into construction processes and ensuring that decisions made during this phase reflect their impact across all pillars. By adopting such a comprehensive approach, the Construction and Supervision phase can contribute to a more successful and sustainable project outcome.

The creation of essential guidelines for the Construction and Supervision phase, in alignment with ISO 9001:2015 and according to BIM and LCSA international standards, begins with the main process: On-Site Risk Management with average risk impact (18.13), which is affected by several vital risks, including R3, R5, R6, R7, R9, R13, R20, R24, R25, R27, R29, R36, R40, R41, R43, and R52. The first three clauses of ISO 9001:2015—Clause 1 (Scope), Clause 2 (Normative References), and Clause 3 (Terms and Definitions)—provide essential background, scope, and definitions to ensure clarity and consistency in applying the standard. While they do not contain specific requirements, they establish a framework for understanding the quality management system. The actionable guidelines begin with Clause 4, which defines the organization’s context and serves as the starting point for implementing effective quality management in the On-Site Risk Management process. Table 14 outlines the essential components of this guideline, systematically linked to the vital risks that must be addressed at each step. Following this structured approach, comprehensive guidelines have been developed for all of the main processes within the Construction and Supervision phases and then the other phases in the bridge lifecycle. When combined, these guidelines form an integrated framework to effectively enhance the sustainability of the entire bridge lifecycle.

Table 14.

The key elements of the On-Site Risk Management guideline.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

The recognition of building sustainable bridges is essential for advancing infrastructure development and achieving long-term environmental, social, and economic viability. This study introduced a comprehensive and novel multidisciplinary framework that integrates risk management strategies with Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) under international standards, such as ISO 9001:2015. By synergizing these tools with global standards, the framework enhances process quality, consistency, and efficiency, establishing a robust pathway for sustainability improvements throughout the bridge lifecycle. This integration represents a significant contribution to the field, offering a structured approach to bridge project sustainability that aligns with global engineering best practices. The precision of BIM in nD modeling and data management, combined with LCSA’s holistic evaluation of environmental, economic, and social impacts, ensures that sustainability considerations are seamlessly embedded into every phase of the bridge lifecycle. The targeted survey conducted as part of this study identified 38 out of 55 risks that account for 80% of the impact on the bridge lifecycle, according to the Pareto Principle. These risks, which largely align with international standards, influence 36 out of 47 main processes. The findings underscore the importance of prioritizing high-impact processes, particularly during the Construction and Supervision phases, where the development of targeted guidelines aligned with ISO 9001:2015 and international BIM and LCSA standards providing a clear strategy for mitigating key risks.

This study offers actionable guidelines and recommendations with broad engineering validity, making it a valuable resource for bridge project stakeholders. It focuses on high-impact processes such as On-Site Risk Management, quality control, health, safety, and environment (HSE) management during construction and supervision. Developing practical tools and workflows that align with ISO 9001:2015 is conducted to ensure consistent quality and efficiency across diverse bridge types and environments and promote capacity-building initiatives to overcome barriers to adoption, such as training requirements and resource constraints, ensuring scalability and widespread implementation. Future research should focus on developing methodologies that equally address all three pillars of sustainability—economic, environmental, and social—ensuring a holistic approach to risk management in bridge projects. It should also focus on developing and testing context-specific adaptations of this framework. This includes pilot studies in regions with varying levels of infrastructure and resources to identify practical barriers and effective strategies for implementation. Such efforts will ensure the framework’s applicability and scalability across diverse scenarios.

The integration of emerging technologies, such as AI and smart infrastructure, holds significant potential for enhancing predictive risk management and real-time monitoring, offering innovative solutions to evolving challenges. Additionally, practical applications of this framework should be investigated through case studies to validate its effectiveness in real-world scenarios. By prioritizing high-impact processes, leveraging innovative tools, and addressing barriers to adoption, this multidisciplinary framework offers a groundbreaking approach to achieving sustainable, resilient, and efficient bridge projects while setting a benchmark for broader infrastructural engineering practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.A. methodology, D.M.A., L.G. and R.A.M.; validation, D.M.A., L.G. and R.A.M.; formal analysis, D.M.A. and R.A.M.; investigation, D.M.A.; resources, D.M.A.; data curation, D.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation D.M.A.; writing—review and editing, D.M.A., L.G. and R.A.M.; visualization, D.M.A.; supervision, L.G. and R.A.M.; project administration, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Zsolt Bencze of the KTI Hungarian Institute for Transport Sciences and Logistics for his invaluable guidance and support throughout the research process. His expertise and constructive feedback significantly contributed to the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costin, A.; Adibfar, A.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.S. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Transportation Infrastructure—Literature Review, Applications, Challenges, and Recommendations. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, H.W. Analysis of the Sustainability of Bridges. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing, Zhangjiajie, China, 23–25 April 2021; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, D.M.; Gáspár, L.; Bencze, Z. BIM and LCSA Applications for Managing Bridge Projects to Achieve Sustainability: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Congress of Finance and Tax, Konya, Türkiye, 10–11 March 2023; pp. 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, D.M.; Gáspár, L.; Bencze, Z.; Maya, R.A. The Role of BIM in Managing Risks in Sustainability of Bridge Projects: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Tu, C.; Li, G. Application of BIM Technology in Bridge Engineering and Obstacle Research. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 798, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, W.; Lee, I.; Lee, J. Bridge Inspection Practices and Bridge Management Programs in China, Japan, Korea, and U.S. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2018, 3, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, V.G.; Tollin, N.; Sattrup, P.A.; Birkved, M.; Holmboe, T. What Are the Challenges in Assessing Circular Economy for the Built Environment? A Literature Review on Integrating LCA, LCC, and S-LCA in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment, LCSA. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Guo, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Using BIM to Improve the Design and Construction of Bridge Projects: A Case Study of a Long-Span Steel-Box Arch Bridge Project. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2014, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhang, W.; Luo, W.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Yeung, N.; Kite, S. Assessing the CO2 Reduction Target Gap and Sustainability for Bridges in China by 2040. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizwa, F.; Kassim, E.R.; Philip, S. Risk Analysis in Bridge Construction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction Management, Angamaly, India, 7–9 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Penadés-Plà, V.; García-Segura, T.; Martí, J.V.; Yepes, V. A Review of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods Applied to the Sustainable Bridge Design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly. 42nd Session, 1987–1988. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ga/cpc/dec42450.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Wan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Ding, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Yin, F. Development of a Bridge Management System Based on the Building Information Modeling Technology. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yuan, Y.; Wei, X.; Shen, R.; Zheng, K.; Qian, Y.; Pu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, H.; Li, X.; et al. Review of Annual Progress of Bridge Engineering in 2019. Adv. Bridge Eng. 2020, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Qin, G.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Han, D. Integrating BIM and IoT for Smart Bridge Management. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 371, p. 022034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Sresakoolchai, J.; Zhou, Z. Sustainability-Based Lifecycle Management for Bridge Infrastructure Using 6D BIM. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Research on Risk Management of Cross-Sea Bridges Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process—Taking Hangzhou Bay Bridge as an Example. World J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Karoumi, R. Life Cycle Assessment of a Railway Bridge: Comparison of Two Superstructure Designs. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2013, 9, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongkowijoyo, C.S.; Gurmu, A.; Andi, A. Investigating Risk of Bridge Construction Project: Exploring Suramadu Strait-Crossing Cable-Stayed Bridge in Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2021, 12, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Yan, J.; Lu, Q.; Chen, L.; Yang, P.; Tang, J.; Jiang, F.; Broyd, T.; Hong, J. Systematic Literature Review of Carbon Footprint Decision-Making Approaches for Infrastructure and Building Projects. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahangi, M.; Guven, G.; Olanrewaju, B.; Saxe, S. Embodied Greenhouse Gas Assessment of a Bridge: A Comparison of Pre-construction Building Information Model and Construction Records. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). American Infrastructure Report Card; American Society of Civil Engineering: Reston, VA, USA, 2021; 172p, Available online: https://infrastructurereportcard.org/ (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Canadian Infrastructure Report Card. Monitoring the State of Canada’s Core Public Infrastructure. 2019. Available online: http://canadianinfrastructure.ca/en/municipal-roads.html (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistischen Bundesamt). 2021. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2021/07/PE21_N048_61.html (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of China. Number of Road Bridges in China from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s) [Graph]. In Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/258358/number-of-road-bridges-in-china/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Wang, J.; Pan, K.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Wei, J.; Guo, K.; Liu, Z. Integrated Carbon Emissions and Carbon Costs for Bridge Construction Projects Using Carbon Trading and Tax Systems—Taking Beijing as an Example. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, I.; Yepes, V.; Marti, J. Sustainability Life Cycle Design of Bridges in Aggressive Environments Considering Social Impacts. Int. J. Comput. Methods Exp. Meas. 2021, 9, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisi, F.; Algohi, B.; Mufti, A.; Thomson, D. Reducing Carbon Dioxide Emissions through Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 11, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.; Yun, N.; Song, H. Application of 3D Bridge Information Modeling to Design and Construction of Bridges. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saback de Freitas Bello, V.; Popescu, C.; Blanksvärd, T.; Täljsten, B. Framework for Bridge Management Systems (BMS) Using Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the European Association on Quality Control of Bridges and Structures (EURO-STRUCT 2021); Pellegrino, C., Faleschini, F., Zanini, M.A., Matos, J.C., Casas, J.R., Strauss, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 200, pp. 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Hisham, M.; Ismail, S.; Youssef, M.; Seif, O. On the Use of Building Information Modeling in Infrastructure Bridges. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference-Applications of IT in the AEC Industry (CIB W78), Cairo, Egypt, 16–18 November 2010; Volume 136, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Hisham, M. Bridge Information Modeling in Sustainable Bridge Management. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Design and Construction (ICSDC 2011), Kansas City, MO, USA, 23–25 March 2011; pp. 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Hisham, M. Implementing Earned Value Management Using Bridge Information Modeling. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 18, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Kitagawa, T. Using CO2 Emission Quantities in Bridge Lifecycle Analysis. Eng. Struct. 2003, 25, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keoleian, G.A.; Kendall, A.; Dettling, J.E.; Smith, V.M.; Chandler, R.F.; Lepech, M.D.; Li, V.C. Life Cycle Modeling of Concrete Bridge Design: Comparison of Engineered Cementitious Composite Link Slabs and Conventional Steel Expansion Joints. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2005, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Safi, M.; Pettersson, L.; Karoumi, R. Life Cycle Assessment as a Decision Support Tool for Bridge Procurement: Environmental Impact Comparison Among Five Bridge Designs. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1948–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammervold, J.; Reenaas, M.; Brattebø, H. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Bridges. J. Bridge Eng. 2013, 18, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, Z.; Xue, K.; Liu, M. Exergy-Based Life Cycle Assessment Model for Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Bridge: Principle and Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinger, B.; Németh, A.; Major, Z.; Kegyes-Brassai, O. Comparative Life Cycle Analyses of Regular and Irregular Maintenance of Bridges with Different Support Systems and Construction Technologies. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 94, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Chen, M. Sustainable Risk Management in the Construction Industry: Lessons Learned from the IT Industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 21, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, B.Y.; Agumba, J.N.; Ansary, N. A Theoretical Review of Risk Identification: Perspective of Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the 5th Applied Research Conference in Africa (ARCA), Cape Coast, Ghana, 25–27 August 2016; pp. 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 31000; Risk Management–Guidelines, 2nd ed. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; 16p.

- Okate, A.; Kakade, V. Risk Management in Road Construction Projects: High Volume Roads. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Infrastructure Development & Management (SIDM), Nagpur, India, 20 January 2019; 4p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinives, K. Process of Risk Management. In Perspectives on Risk, Assessment, and Management Paradigms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/64630 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Hayashi, Y.; Kamei, K. Risk Management. In Science of Societal Safety. Trust; Abe, S., Ozawa, M., Kawata, Y., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, F. On the Definition of Risk. J. Risk Manag. Financ. Inst. 2020, 13, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iten, R.; Wagner, J.; Röschmann, A.Z. On the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Risks in Smart Homes: A Systematic Literature Review. Risks 2021, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute (PMI). Guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th ed.; Project Management Institute: Upper Darby, PA, USA, 2021; 370p, ISBN 978-1-62825-664-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hemant, G.; Mishra, A.K.; Aithal, P.S. Risk Management Practice Adopted in Road Construction Project. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2022, 7, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, F. Risk Management as a Tool for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamid, R.A.; Doh, S.I. A Review of Risk Management Process in Construction Projects of Developing Countries. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 271, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, O. Risk Management in Construction Sector. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2020, 8, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Liang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chen, H. Research on the Correlation of Safety Risk of Railway Bridge Construction Based on Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.T.; Nur, M.; Purba, H.H. Bridge Project Development Risk Management: A Literature Review. EPRA Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2020, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk. Building Information Modeling. What Is BIM. Available online: https://www.autodesk.eu/solutions/bim (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers, and Contractors, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jiang, S.; Skibniewski, M.; Man, Q.; Shen, L. A Literature Review of the Factors Limiting the Application of BIM in the Construction Industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 23, 764–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, G.; Huang, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sadick, A.-M. BIM and GIS Applications in Bridge Projects: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zheng, Y. Application of BIM in Bridge Engineering and Its Risk Analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 526, 012223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Research on Construction of Highway Bridge Quality Engineering Based on BIM Technology. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 510, 052092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, L.; Saad, T. Building Information Modeling for Highway Bridges Projects. Manual for Quality Control for Plants and Production of Structural Precast Concrete Products, 5th ed.; MNL (116-21); Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021; pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Fischer, M. Framework and Case Studies Comparing Implementations and Impacts of 3D/4D Modeling across Projects; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008; 101p. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Y. BIM for Bridge Design. IABSE Symp. Rep. 2016, 106, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmualim, A.; Gilder, J. BIM: Innovation in Design Management, Influence, and Challenges of Implementation. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2014, 10, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Lill, I.; Witt, E. An Overview of BIM Adoption in the Construction Industry: Benefits and Barriers. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Construction Economics and Organization, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–8 May 2019; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Vu, D.; Le, N.; Nguyen, T. Benefits and Challenges of BIM Implementation for Facility Management in Operation and Maintenance Phase of Buildings in Vietnam. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 869, 022032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M. An Overview of Benefits and Challenges of Building Information Modelling (BIM) Adoption in UK Residential Projects. Constr. Innov. 2019, 19, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hire, S.; Sandbhor, S.; Ruikar, K.; Amarnath, C. BIM Usage Benefits and Challenges for Site Safety Application in the Indian Construction Sector. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfsen, C.N.; Lassen, A.K.; Han, D.; Hosamo, H.; Ying, C. The Use of the BIM-Model and Scanning Quality Assurance of Bridge Constructions. In ECPPM 2021–eWork and eBusiness in Architecture, Engineering and Construction, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021; 4p. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Mateen Khan, A.; Eldin, S.M.; Aslam, F.; Kashif Ur Rehman, S.; Jameel, M. BIM Adoption in Sustainability, Energy Modelling, and Implementation Using ISO 19650: A Review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 15, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.Y.; Al-Kazzaz, D.A. A Comparative Analysis of BIM Standards and Guidelines Between UK and USA. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1973, 012176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M. BIM-Based Bridge Management System. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Engineering, Project, and Product Management (EPPM 2017), Amman, Jordan, 20–22 September 2017; Şahin, S., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.; Guan, H.; Hou, L.; Jo, J.; Blumenstein, M.; Wang, J. Defining a Conceptual Framework for the Integration of Modelling and Advanced Imaging for Improving the Reliability and Efficiency of Bridge Assessments. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 6, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, P. BIM/GIS Integration for Web GIS-Based Bridge Management. Ann. GIS 2021, 27, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. An Intelligent Bridge Management and Maintenance Model Using BIM Technology. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 7130546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, D.; Zhang, T.; Han, L. Development of a BIM-Based Bridge Maintenance System (BMS) for Managing Defect Data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccone, A.; Suglia, P.; Asprone, D.; Salzano, A.; Nicolella, M. Defining a Digital Strategy in a BIM Environment to Manage Existing Reinforced Concrete Bridges in the Context of Italian Regulation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.J.; Neugebauer, S.; Lehmann, A.; Scheumann, R.; Finkbeiner, M. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment Approaches for Manufacturing. In Sustainable Manufacturing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloepffer, W. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Products. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, A.; Richter, F.; Götze, U. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Manufacturing—Analysis of Existing Approaches. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 43, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/SETAC. Towards a Lifecycle Sustainability Assessment: Making Informed Choices on Products; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya; Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC): Pensacola, FL, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Valdivia, S.; Ugaya, C.M.; Hildenbrand, J.; Traverso, M.; Mazijn, B.; Sonnemann, G. A UNEP/SETAC Approach Towards a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment—Our Contribution to Rio+20. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Ren, J. Life Cycle Decision Support Framework: Methods and Case Study. In Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Decision-Making; ScienceDirect: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Pradip, P.K.; Deepjyoti, D. Advancing Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment Using Multiple Criteria Decision Making. In Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Decision-Making; ScienceDirect: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; 23p. [Google Scholar]