Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of accurately determining the arrival time of stress wave signals in SHPB test data processing. To eliminate human error, we introduce the time-window energy ratio method and evaluate six filters for noise reduction using box fractal dimensions. A mathematical model is established to optimize the stress equilibrium and impact process, which is solved using particle swarm optimization, resulting in the PSO-TWER method. We explore the impact of inertia weight and calculation methods on optimization outcomes, defining a stress equilibrium evaluation index. The results indicate that time-window length significantly affects arrival-time outputs, and the dynamic inertia weight factor enhances optimization convergence. The method accurately determines arrival times and effectively screens test data, providing a robust approach for SHPB test data processing.

1. Introduction

Regarding early Hopkinson data processing methods, the classical two-wave method given by S.L. Lopatnikov [1] is often used for calculations, and the classic two-wave method is always used to calculate the stress and strain of loading materials. Song [2] pointed out that the alignment of the wavefront will introduce errors in the data processing, and the three-wave method with whole times was proposed. The study proved the applicability of soft materials. However, Song also proposed that the classical three-wave method is irreplaceable with respect to loading harder materials. According to the description of association standards (testing methods for determining the dynamic uniaxial compression strength of rock materials) by the China Society of Explosives and Blasting, the classic three-wave method is still the mainstream data processing method for rock material. This viewpoint is also expressed in previous research reports on rock dynamic failure [3,4,5]. With regard to test standards, the arrival picking of the incident wave can be calculated by the wave velocity of the bar, the sampling rate, and the distance between the strain gauge and the rock specimen, and the arrival point of the signal can be determined by the observer. However, different arrival pickings cause discreteness in data processing results due to the differences in test conditions. Therefore, the arrival picking problem still needs to be paid more attention. Arrival picking has been studied for many years for microseismic and seismic signals, and the research results are now more mature.

Lixibing [6] composed the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and the short-time average to long-time average (STA/LTA) to determine P-phase arrival times. Then, in continuing research, a seismic P-phase arrival picking method named the EMD-AIC picker was proposed. The method has generated precision picking results for the microseismic signals of mines. Dowan Kim [7] presented an arrival picking method based on the difference between multi-window energy ratios, and the method obtained precise arrival picking points for seismic signals with low signal-to-noise ratios. In SHPB test data, the frequency of electrical signals detected by strain gauges is far lower than for seismic and microseismic signals. In an efficient time domain, except for noise waves, only one or two significant peaks are present in incident, reflected, and transmitted waves. The substantial energy interference caused by the superposition of complex noise is less. In order to facilitate the calculations, the problem of arrival picking can be solved by the stationary time-window energy ratio method.

Due to differences in testing equipment, noise often exists in waveform signals, and denoising processing is necessary; the fractal theory can be used to describe the complexity of signals or images. Wu et al. [4] used the fractal geometry theory to analyze the development of horizontal and vertical mining cracks quantitatively during coal mining. Lei et al. [8] analyzed the fractal dimension of fracture images of coal–rock composites after uniaxial loading. Ivica et al. studied fracture network photographs using fractal dimensions. Miao et al. [9] analyzed the fractal characteristics of mining fracture networks. He et al. [10] described the fractal characteristics of carbonate-based sand and silicate-based sand, and the effect of grain size on the pore size distribution and fractal dimensions was discussed. According to the standards of the SHPB test, a stress equilibrium check must be performed prior to test data processing and show the typical waveform of the stress equilibrium. However, the relevant standards for stress balance need to be clearly defined. The stress equilibrium process is related to the load force in the terminal face of the incident bar and the transmitted bar. Based on these characteristics, Hong [11] defined a threshold in his study; the internal stress of the rock specimen reaches a constant state when the relative stress difference between the two ends of the specimen is less than 5%. Li [12] proposed the stress equilibrium factor in their study; it is considered that the stress equilibrium state of the specimen is better when the factor is close to 0. The above two methods are also widely recognized and applied; the quality of three-wave selection is closely related to the stress equilibrium state. Therefore, a mathematical model related to the stress equilibrium factor can be constructed based on the length of the time window as the independent variable.

The solution of mathematical models often relies on algorithms. Venkata Rao introduced several novel, metaphor-free, and parameter-free optimization algorithms for addressing diverse single, multi-, and many-objective optimization challenges across science and engineering [13,14]. Due to the mathematical modeling of stress equilibrium factors being diverse single problems, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm exhibits excellent performance in solving both single-objective and multi-objective optimization problems [15,16,17,18].

In the study of Mohamed El-Sayed M. SAKR [19], the optimal results of particle swarm optimization, the gravitational search algorithm with particle swarm optimization (GSA-PSO), and the eagle strategy with particle swarm optimization (ES-PSO) were compared. The problem of antenna positioning in satellite systems was solved. Qi Tang [20] improved the swarm position update formula of the PSO algorithm, then combined it with the improved DE algorithm to solve multi-UAV cooperative trajectory planning problems. Harshala Shingne [21] colligated the firefly algorithm (FA), PSO, and tabu search (TS) to solve problems in resource allocation and scheduling.

This article introduces the time-window energy ratio method for the arrival picking of a waveform in the three-wave method for Hopkinson test data processing. The robust loess fitter is used to denoise the waveform, and the fractal dimensions of signals decrease. A mathematical wave signal model of a specimen’s stress equilibrium state is established, and the PSO algorithm is used to solve the mathematical model. The article discusses the influence of five variable inertia weight factors on the optimization results. A new evaluation index for test results based on the stress balance factor is proposed, which provides a reference for Hopkinson test data processing and result evaluation.

2. Related Work

2.1. Time-Window Energy Ratio Method

For waveform signals of the incident wave, the energy difference between the time window after the incident-wave start moment and the energy in the time window before arrival is relatively large, so the energy ratio can judge the arrival moment of the waveform signal. Assuming that the waveform electrical signal recording channel is , the time (t) is the center of the time window. Then, the length (M) of the time window is taken before and after the time (t) in the recording channel. The energy ratio between the frontal and posterior time windows can be calculated by Equation (1).

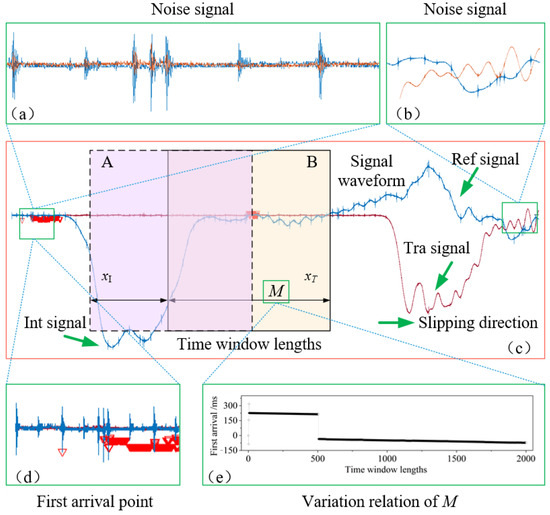

where is the amplitude of k, is the energy ratio of the frontal time window and posterior time window, and M is the length of the time window. In the study of Chang J [22], differences in M influence the selection of arrival times. The fluctuations generated by external disturbances lead to noise signals recorded during the acquisition of the voltage signal by the Hopkinson test equipment. As Figure 1a,b show, the noise signals can be observed in the whole signal [12]. In a small-scale range, noise signals can be regarded as miniature starting points with high frequency and low amplitude. A and B is the time-window of the incident wave and transmitted wave, respectively. Therefore, as Figure 1d shows, the selection of the arrival moment is more susceptible to the influence of noise signals when the time-window length (M) is too small. Figure 1e shows variation in the arrival moment for time-window length M, and the mutation evident in M is 500.

Figure 1.

The representative voltage curves and time-window energy ratios: (a) noise signal in the initial and final period; (b) noise signal in the initial period; (c) energy ratio of the two-window method; (d) first-break times; (e) first break for the time-window lengths.

2.2. Denoising of Waveform Signals

The complexity and fractal characteristics of a waveform signal are calculated by the box dimension method. The principle is that the signal curve is covered by a box with a side length r, and the number of nonempty boxes in the whole area is recorded as N(r). Then, as r is constantly changed, N(r) changes accordingly, and the fractal dimension (D) can be calculated by Equation (2) [23].

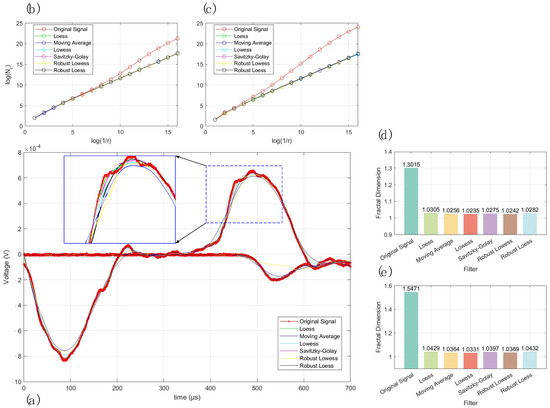

Signals measured via the SHPB test in the Impact Dynamics Laboratory of the School of Mining Engineering at the University of Science and Technology Liaoning were selected for analysis. Six different filters were selected to denoise the stress wave signals, namely, moving average, lowess, loess, Savitzky–Golay, robust lowess, and robust loess filters. The raw signal and smoothing results are shown in Figure 2a. It can be seen that there is a large amount of noise in the original image. From a qualitative point of view, the scale of the noise signal of the stress wave data is small. Due to the existence of the rod end shaper, the incident-wave waveform is close to a sine wave; each of the six filters preserves the overall trend of the stress wave signal. The difference between the results is reflected in the degree to which the signal details are retained. Since the dynamic response characteristics of rock loading depend on the values monitored by the strain gauges, the accuracy of subsequent data processing will be affected if the peak value of the smoothed curve is too large. If the moving average result leads to a decrease in the peak value of the curve, the transmitted-wave smoothing result of robust lowess is too different from the original waveform, and the result of the robust lowess filter not only retains the trend of the curve better but also has a small numerical error. The fractal dimension calculation curve for each group of results is calculated using Equation (2), as shown in Figure 2b–e. The fractal dimension of the original image and the smoothed result are significantly different, and the fractal dimensions of the incident wave and the transmitted wave are 1.3014 and 1.5471, respectively, which are the highest values in the results. After denoising, the fractal dimensions of the first group were between 1.0178 and 1.0282, and those of the second group were between 1.0178 and 1.0432. The reduction in fractal dimensions indicates a reduction in curve complexity, which further verifies the validity of the filtering results. Since the difference in the fractal dimension for each component after filtering was small, combined with the analysis of Figure 2a, it was decided to use the robust loess filter for subsequent smooth denoising.

Figure 2.

Waveform signals and denoising effects of different filters: (a) original signal and smoothed signal; (b) fractal dimension calculation at incident wave; (c) fractal dimension calculation at transmitted wave; (d) fractal dimension at incident wave; (e) fractal dimension at transmitted wave.

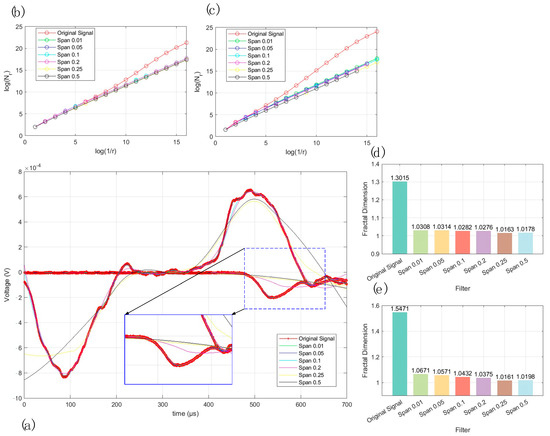

When using a robust loess filter for denoising, a span with a range of (0,1) needs to be used; the setts value represents the number of data points used for smoothing as a percentage of the total number of curve points. In order to further discuss the influence of span on the smoothing effect of curves, spans of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.25, and 0.5 were used for calculations. The results obtained are shown in Figure 3. Analyzing the overall trend, the size of the span significantly affects the overall trend of the results. When the span values are 0.2, 0.25, and 0.5, the filtering results are quite different from the overall trend of the original curve. The trend of transmitted waves at a span of 0.5 is even close to the level, indicating that there are too many data points for smoothing; the noise of the original signal is removed, while the signal details are lost to too great an extent. When the span is 0.1, the transmitted-wave denoising effect is basically the same as the original signal, and the incident wave is significantly different from the original signal at 420 μs; the filtering results for the spans of 0.01 and 0.05 are not much different, which ensures the details of the signal while removing noise. In Figure 3b–e, from the statistical results for the fractal dimensions, the fractal dimension value tends to decrease as the span increases. When the span is 0.01, the fractal dimensions are 1.0308 and 1.0671, which shows that the noise signal is effectively removed. The results at 0.05 are 1.0314 and 1.0571, which are slightly different from the results at 0.01. This shows that the impact of different spans on the results is mainly on the trend. Based on the above explanation, given the premise of ensuring the operation speed and smoothing effect, the appropriate span value of the robust loess filter should be 0.01~0.1.

Figure 3.

The waveform signals and denoising effects of different filters: (a) original signal and smoothed signal; (b) fractal dimension calculation at incident wave; (c) fractal dimension calculation at transmitted wave; (d) fractal dimension at incident wave; (e) fractal dimension at transmitted wave.

2.3. The Stress Equilibrium Factor

The assumption of stress uniformity is a precondition for proving the validity of test data in the SHPB test [12]. Due to the difference in wave impedance between elastic bars and rock materials, the transmission and reflection are relatively complicated in rock materials. It takes a certain amount of time for a rock specimen to reach the stress equilibrium; the equilibrium time can be calculated with the length of the specimen and the p-wave velocity, as shown in Equation (3):

This phenomenon of stress difference at the two ends of specimens during dynamic loading determines the stress response and equilibrium effects in rock specimens. The first method is the relative stress difference () between the two ends of the specimen, where a smaller value represents a higher state of stress equilibrium inside the specimen, and is calculated as shown in Equation (4):

where and are the stress difference and the stress average at the two ends of the rock specimen, respectively. Furthermore, and are the transmission and reflection coefficients, respectively, while and are the time of the kth propagation of the stress wave in the granite specimen and the corresponding stress, respectively. Another calculation index used to judge the stress equilibrium state of the specimen is the stress equilibrium factor. When the stress equilibrium factor is close to 1, this means that the rock specimen has reached the stress equilibrium state, which can be calculated by Equation (5):

where is the stress equilibrium factor of the specimen at time t, and , , and are the stress of the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves at time t, respectively, in MPa.

2.4. Objective Function

Firstly, for each given set of and , , , and are calculated under a condition, where , , and represent functions related to and , as shown in Equation (6):

where is the time-window length of the incident wave and is the time-window length of the transmitted wave.

Based on the above discussion, the stress equilibrium factor evaluates the stress equilibrium state of the specimen by describing the differences between the incident wave, the reflected wave, and the transmitted wave at each instant. When the results of picking up these three waves are accurate, the stress equilibrium factor for all points within the signal time domain will be close to 1. However, if the selected positions are incorrect, the value of the stress equilibrium factor will be greater than 1. When the sum of stress equilibrium factors is minimized, this indicates that the position of the particle has reached its optimal state. Therefore, the objective function can be constructed as shown in Equation (7):

2.5. PSO-TWER Method

In the PSO algorithm proposed by Kennedy and Eberhart [24], firstly, a group of random particles (random solutions) which simulate birds in a flock are initialized. After multiple iterations, the optimal results can be found in an n-dimensional space in which the current positions of particles are recorded as , the current renewal speeds of particles are recorded as , and the best positions of particles ever experienced are recorded as . The renewal speed and the position of particles can be updated by Equation (8).

where is the velocity of the particle, is a random number between 0 and 1, is the current position of the particles, and are the learning factors, pbesti is the best location currently discovered, and gbesti is the best position among all particles.

For the PSO algorithm, the diversity of particles is reduced in later iterations, and the optimal local phenomenon often occurs. In order to solve this problem, the inertia weight indicator is introduced to improve the algorithm.

where ω is the inertia factor, which plays a role in balancing global and local searches in optimization algorithms. When ω is large, the algorithm tends to maintain the current speed and direction, which helps to conduct a wider range of searches globally and enhance global optimization ability. On the contrary, when ω is small, the algorithm is more likely to change the current speed and direction, which helps to conduct more precise searches in the local range [24].

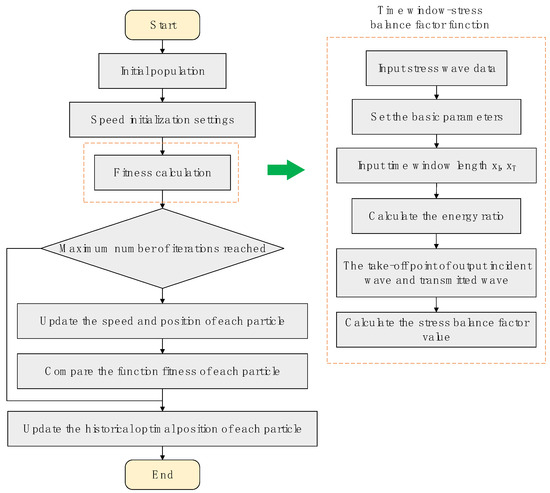

The processing steps are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of PSO algorithm.

① Initialize the particle swarm, randomly initialize the initial state of the particles in the swarm, input the inertia factor and the learning factor, and set the number of iterations (k).

② Input the stress wave data of the incident and transmitted waves.

③ Calculate the energy ratio of the particles according to Equation (1).

④ Judge the arrival point of the incident wave and the arrival point of the transmitted wave at the position with the maximum energy ratio.

⑤ Take segments of the incident wave, the reflected wave, and the transmitted wave based on the starting point obtained in step (4).

⑥ Calculate the stress equilibrium factor at the location of the particles according to Equation (4).

⑦ According to Equations (7)–(9), update the individual optimal value and the global optimal value for the particle population.

⑧ Judge whether the number of iterations reaches the termination number (k); if so, proceed to step ⑨, otherwise return to step ③ to re-evaluate the particles.

3. Results

3.1. Test Example Verification Device

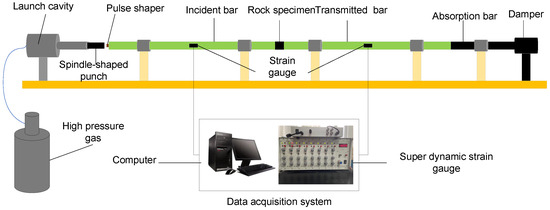

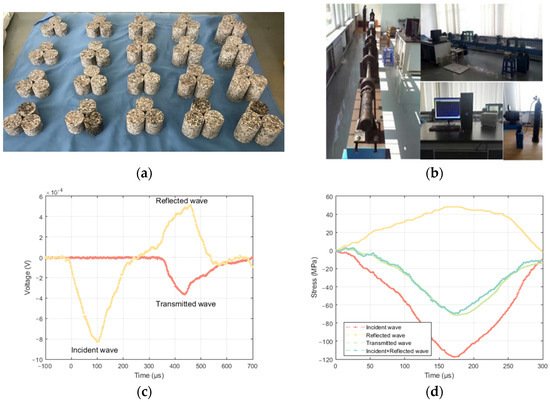

In this study, all laboratory tests were performed in the SHPB loading system at the Liaoning University of Science and Technology, as shown in Figure 5. The incident bar is 2100 mm, the transmission bar is 1800 mm, and the absorber bar is 800 mm, and the bars are all made of high-strength steel with a 50 mm diameter and a 210 GPa elasticity modulus. All the specimens were taken from a mine in Xinyang City, Henan Province, China, and the tolerance of uniformity and nonparallelism at the ends of the specimens was less than 0.02 mm. The specimens were made into cylinders with a diameter of 50 mm and a reflection coefficient of −0.55~0.52, and the mechanical parameters of the granite are shown in Table 1 and Figure 6a. As shown in Figure 6b,c, a typical test was performed to check the stress equilibrium before formal tests were conducted and to see that the typical stress wave pattern for a tested rock specimen, as well as the incident wave, the transmitted wave, and the reflected wave, met the test requirements.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the SHPB experiment system.

Table 1.

Mechanical parameters of granite under static load.

Figure 6.

Specimens of granite and dynamic stress equilibrium: (a) granite specimens; (b) SHPB system; (c) typical stress wave pattern of a tested rock specimen; (d) dynamic stress equilibrium.

3.2. Analysis of Results

According to the mathematical model described above, two groups of signals of incident and transmitted waves with a total of 28,000 points were selected for the experimental results. In this operation, the initial population number was set to 500, the population dimension was 2, the maximum iteration time was 50, the limit of the time-window length was 2 to 10,000, and the speed limit was −200 to 200; then, the mathematical model was solved by MATLAB.

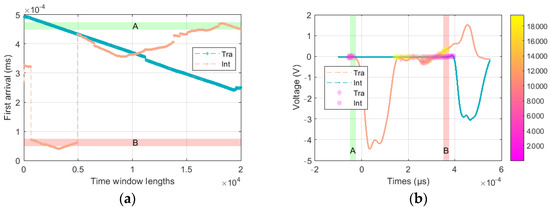

The complete stress wave signal taken in this study had 28,000 points. There were no explicit requirements regarding the time-window length in past research. Figure 7 shows the relationship between the time-window length and the detection results for the incident-wave, reflected-wave, and transmitted-wave arrival times. In Figure 7a,b, areas A and B provide a more suitable range for the incident-wave initial arrival time. During the test process, the incident wave and the reflected wave were recorded by the strain gauge of the incident bar. The incident and reflected waves had two apparent peaks in a complete time domain. In Figure 7a, the incident wave curve changes significantly when the time window is about 5000, which shows that the reflection wave affected the result of arrival picking. For the arrival picking of the reflection wave, the position of the arrival time shows a linear decreasing trend with the time-window length. This explains the fact that the time-window length significantly affected the arrival picking. In Figure 7b, the suitable time-window length is between 2000 and 6000, which explains the fact that the suitable time-window length was about 7% to 21.5% of the total number of signals.

Figure 7.

Relationship between peak stress and temperature and strain rate. (a) The relationship between time window and first arrival (b) The calculation result is in the original signal.

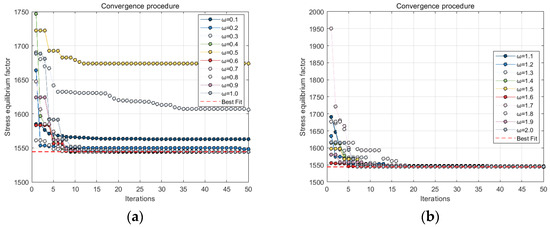

In the application of the particle swarm algorithm, the inertia weight mainly controls the global and local search ability of the PSO algorithm, and the appropriate inertia weight factor and learning factor should be selected according to the solution problem [25,26,27]. However, there is still no exact parameter calculation method. In this optimization, the learning factor was 0.5 and the inertia weight was 0.1–2.0 for 20 iteration sets of 50 iterations. The calculation results are shown in Table 1, and the convergence curves are shown in 6.

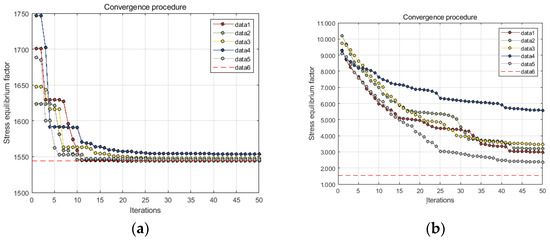

The convergence of the fitness values for ω = 0.1 to 1.0 is shown in Figure 8a. As shown in Table 2, in only 6 of the 10 sets of optimization results did the search reach the optimal fitness in 50 iterations. When ω = 0.4, 0.6, the search results were better and the algorithm was able to complete convergence within 20 iterations, while in the interval of ω = 0.7 to 1.0, the number of iterations required to reach convergence was greater than 20, and for ω = 0.9, 1.0, nearly 50 iterations were required to complete convergence. It can thus be seen that although it has a significant effect on optimization results, there is no obvious functional relationship with the increase in ω. In addition, in the experimental results that did not reach the optimum in Figure 8a, the fitness curve converges to a horizontal straight line after 30 iterations, and the fitness at this stage basically ceases to change; the particles are trapped in a local optimum. A similar situation exists in Figure 8b, where the particles show a relatively good result in finding the optimum, but the local optimum also exists in the same way, and the speed of the optimal convergence is relatively slow, close to 50 iterations.

Figure 8.

Relationship between peak stress and temperature and strain rate: (a) iteration process for average fitness; (b) iteration process for optimal fitness.

Table 2.

Parameter settings and results for PSO.

Five different methods for updating inertia weights were selected, as shown in Table 3. Methods (1), (2), and (5) are used to limit a range of inertia weight factors and calculate the inertia weight factor for each iteration according to the boundary size and the process of the iterations, and the positions of all particles in the population are updated based on ω. Methods (3) and (4) are based on the relationship between the fitness of each particle and the current optimal fitness relationship; a separate inertia weight factor is assigned to all particles.

Table 3.

The setting of inertia weights.

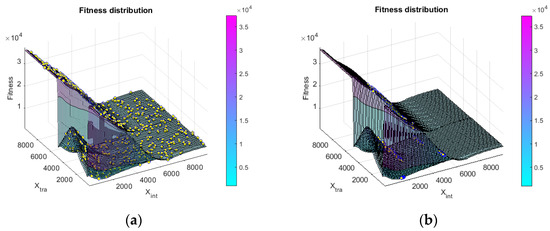

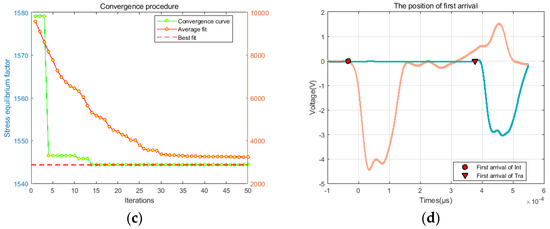

The optimal fitness and average fitness variation of the five inertia weight factors are shown in Figure 9. Method 1 and method 2 were able to reach a near-optimal fitness in 10 iterations, and both reached the optimal fitness value after around 20 cycles after a short search, as shown in Figure 9a. In Figure 9b, it can be seen that the two methods have a similar ability at the initial stage and that the average fitness differences in the late iteration are also similar. Method (3), method (4), and method (5) do not reach the optimal fitness, and method (5) shows poor search ability in Figure 9a,b. It is worth noting that although method (5) does not converge to the optimal fitness, the results are close, with an error of 0.058%, and it has outstanding performance in the early convergence and average fitness convergence of the iterations. The reason is that the inertia weight factor in the original study introduces a weight control factor (K) in the numerator term; unfortunately, the rules for the value of this factor are not provided, which also shows the strong search potential.

Figure 9.

Iteration process for inertia weight. (a) Best fitness (b) Average fitness.

Figure 10 shows the optimization results for the PSO-TWER method. Figure 10a shows the distribution of the 500 initial population particles, and the results show that the particles are distributed throughout the fetching region; Figure 10b shows the final distribution of particles after 50 iterations. The particle distribution is significantly more concentrated, indicating the algorithm’s good global search capability, but some particles are still at the local optimum. The convergence curves of the best fitness and the average global fitness of the iterations are plotted in Figure 10c, and the inertial weight updating method has a good convergence effect. The global best fitness can converge more obviously within 5 iterations and reach the minimum of the objective function within 15 iterations after falling into a short local optimum. The average fitness also shows a decreasing trend until 25 iterations. The average fitness also decreases until 25 iterations and remains low after 30 iterations. Figure 10d shows the locations of the final arrival picking of the incident wave and the transmitted wave, and the optimization results satisfy the requirements of the test standards.

Figure 10.

Relationship between peak stress and temperature and strain rate: (a) initial population distribution; (b) final population distribution; (c) iteration process of PSO-TWER; (d) final position of first break in incident wave and reflection wave.

4. Hopkinson Stress Balance Effect Index

4.1. Correction of the Segment Interval

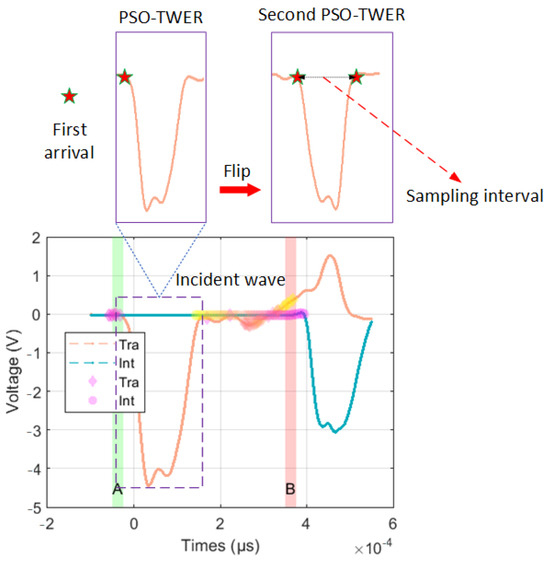

The incident wave, the reflected wave, and the transmitted wave are all functions of the loading time (t). The specific method for selecting the length of each wavelength is not given in the test standards. The segment interval can be set in advance when the PSO-TWER method is used for the first operation. The segment interval is less than the distance between the arrival time of the incident wave and the arrival time of the reflected wave as the Figure 11. The distance between the incident wave’s starting point and the reflected wave’s starting point is indicated.

Figure 11.

Correction of sampling interval.

4.2. The Stress Equilibrium Index of SHPB

In the stress equilibrium state described in the study of Hu and Wang, the loading process can be divided into three stages: the stress superposition stage, the stress equilibrium stage, and the stress deterioration stage. The stress difference between the two ends of the specimen will fluctuate in a range during the impact loading, and it is challenging to reach absolute stress equilibrium in rock specimens. Because the specimen experiences a brief state of stress disequilibrium–stress equilibrium–stress disequilibrium, the number of calculated stress equilibrium factors close to one point can be used to evaluate the stress equilibrium effect, and a new evaluation index can be established by Equation (12).

where is the evaluation index of the test results, is the number of points in the segment, and is the number of points close to the stress equilibrium position.

The calculation of is shown in Equation (13).

where represents the function related to the loading time (t) and a is the correction coefficient, its physical meaning being the allowable error. In this study, the median is taken as 1.5.

4.3. Applicability Analysis

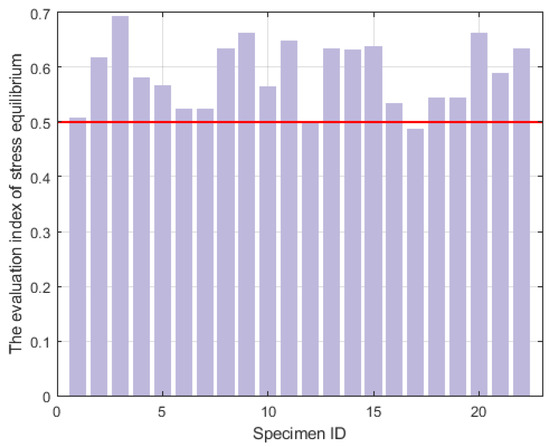

The stress equilibrium effect of granite specimens is shown in Table 4, and the stress balance evaluation indicators range from 0.4884 to 0.6939. Meeting the threshold of the qualified stress equilibrium is set as . As shown in Figure 12, most of the data in the test results meet the stress equilibrium. It is worth noting that it is difficult to reach a value above 0.7. Maintaining stress equilibrium during the entire period in the specimen is difficult. Further, due to microfractures and microporosity in rock, there is hole closure and microcrack expansion, resulting in plastic deformation and irreversible damage to the specimen, and the stress equilibrium state is poor.

Table 4.

The stress equilibrium effect of the granite specimens.

Figure 12.

The statistical results for the stress equilibrium index.

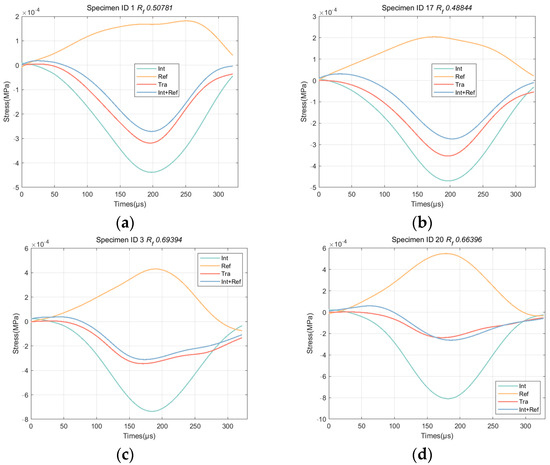

From the results shown in Figure 12, the highest and lowest test results were selected, and the stress equilibrium curves were plotted, as shown in Figure 13. In Figure 13a,b, the stress equilibrium index was near the set threshold of 0.5, and the transmission wave curve and incident + reflection wave curve almost did not coincide during the entire loading process, indicating that the stress equilibrium state of the specimen was poor. In Figure 13c,d, the stress equilibrium index was more significant than 0.65. The difference between the transmitted wave curve and the incident + reflected wave curve was relatively small, with overlapping parts. The stress equilibrium state of the specimen met the test requirements.

Figure 13.

The statistical results and stress equilibrium curves. (a) Specimen ID 1 (b) Specimen ID 17 (c) Specimen ID 3 (d) Specimen ID 20.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study addresses the selection of the stress waveform arrival time in SHPB test data processing, establishes a mathematical model with the stress equilibrium factor as the objective function, then proposes the PSO-TWER method, studies the influence of the inertia weight factor on the algorithm seeking effect, and proposes the stress equilibrium evaluation index according to the importance of the stress equilibrium effect in the impact test, with the following specific conclusions: the SHPB waveform signal has small-scale noise, the recognition effect of the time-window energy ratio method is easily affected by noisy signals, and the time-window length significantly affects the selection of a signal. The strain signal of the incident bar is less regular due to the existence of two waveforms, the incident wave and the reflection wave, and the influence of the time-window length is less regular. The location of the arrival time at a length of about 17.8% of the total time domain of the signal will produce abrupt changes, and a suitable time-window length for a signal is between 7% and 21.5% of the total signal. The PSO-TWER algorithm with dynamic weight improvement can quickly converge within 5 iterations, reach the minimum value of the objective function within 15 iterations, and meet the testing criteria for arrival picking, demonstrating the applicability of the PSO-TWER method in Hopkinson data processing. The proposed stress equilibrium evaluation index is able to judge the stress balance effect of a specimen during the full impact process and has good applicability. In the future, we plan to use this method to detect the dynamic properties of more materials, not just rocks. Furthermore, from an algorithmic perspective, a termination strategy with a fixed number of iterations may be inefficient, and fitness may be able to establish a relationship with the termination strategy of the algorithm, which may provide new ideas in subsequent research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, X.W. and L.G.; Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation, X.W. and Z.X.; Visualization, Investigation, Z.X. and L.G.; Formal analysis, X.W. Visualization, X.W.; Writing—Reviewing and Editing, X.W. and Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51974187), Educational Commission of Liaoning Province of China (Grant No. LJKZ0282) and Liao Ning Revitalization Talents Program (Grant 2203173) and Foundation for University Key Teacher by University of Science and Technology Liaoning (Grant No. 601011507-25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lopatnikov, S.L.; Gama, B.A.; Krauthouser, K.; Gillespie, G. Applicability of the Classical Analysis of Experiments with Split Hopkins Pressure Bar. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2004, 30, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, S.; Hanajima, N.; Zhang, X.; Pu, R. Energy Dispatching Based on an Improved PSO-ACO Algorithm. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 2023, 3160184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatnikov, S.L.; Gama, B.A.; Krauthouser, K.; Gillespie, G. Influences of the number of non-consecutive joints on the dynamic mechanical properties and failure characteristics of a rock-like material. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 146, 107101. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Li, H.; Fukuda, D.; Liu, H. Development of a finite-discrete element method with finite-strain elasto-plasticity and cohesive zone models for simulating the dynamic fracture of rocks. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 156, 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jin, T.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Li, C.; Li, X. Dynamic characteristics and crack evolution laws of coal and rock under split Hopkinson pressure bar impact loading. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 075601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, Z.L. Numerical Simulation of the Rock SHPB Test with a Special Shape Striker Based on the Discrete Element Method. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2014, 47, 1693–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Joo, Y.; Byun, J. First-Break Picking Method Based on the Difference Between Multiwindow Energy Ratios. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Hao, D.; Cao, S. Study on Uniaxial Compression Deformation and Fracture Development Characteristics of Weak Interlayer Coal–Rock Combination. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Tu, S.; Tu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Research on Fractal Evolution Characteristics and Safe Mining Technology of Overburden Fissures under Gully Water Body. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.H.; Ding, Z.; Hu, H.B.; Gao, M. Effect of grain size on microscopic pore structure and fractal characteristics of carbonate-based sand and silicate-based sand. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L. Size Effect on Strength and Energy Dissipation in Fracture of Rock under Impact Loads; Central South University: Changsha, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xibing, L. Rock Dynamics Fundamentals and applications; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, R. Rao algorithms: Three metaphor-less simple algorithms for solving optimization problems. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2020, 11, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Keesari, H.S. A self-adaptive population Rao algorithm for optimization of selected bio-energy systems. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2021, 8, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A.; Schenck, W. A conceptual and practical comparison of PSO-style optimization algorithms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Mao, G.; Liang, Y. PSO-sono: A novel PSO variant for single-objective numerical optimization. Inf. Sci. 2022, 586, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Moayedi, H.; Foong, L.K.; Al Najjar HA, H.; Jusoh WA, W.; Rashid AS, A.; Jamali, J. Optimizing ANN models with PSO for predicting short building seismic response. Eng. Comput. 2020, 36, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, R.; Tang, S.; Su, H.; Cao, K. Intelligent fault diagnosis of hydraulic piston pump combining improved LeNet-5 and PSO hyperparameter optimization. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 183, 108336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.M.; Hassanm, A.M. Satellite Tracking Control System Using Optimal Variable Coefficients Controllers Based on Evolutionary Optimization Techniques. El-Cezeri 2023, 10, 326–348. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Dai, J.; Ying, J.; Wu, G. Multi-UAV trajectory planning based on differential evolution of Levy flights particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyber Security, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Economy (CSAIDE 2023), Nanjing, China, 3–5 March 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shingne, H.; Shriram, R. Heuristic deep learning scheduling in cloud for resource-intensive internet of things systems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 108, 108652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.M.; Chao, W.A.; Kuo, Y.T.; Yang, C.M.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Field experiments: How well can seismic monitoring assess rock mass falling? Eng. Geol. 2023, 323, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xie, D.; Yi, S.; Yin, S.; Hu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Fractal Study of the Development Law of Mining Cracks. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Shi, Y.; Fang, J. Evaluation scheme design of college information construction based on a combined algorithm. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, S.; Dalei, R.K.; Rath, S.K.; Sahu, U.K. Selection of PSO parameters based on Taguchi design-ANOVA-ANN methodology for missile gliding trajectory optimization. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, S.; Zi, B.; Chen, B.; Zhu, W. Multi-Objective Optimal Design of a Cable-Driven Parallel Robot Based on an Adaptive Adjustment Inertia Weight Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. J. Mech. Des. 2023, 145, 083301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Zhao, K.; Shen, X. Fractional Order Control of Airborne Optoelectronic Platform Based on Improved PSO Algorithm. Electron. Opt. Control 2023, 30, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.Y.; Li, Y.B.; Sun, Q. A Novel Short-Term Ship Motion Prediction Algorithm Based on EMD and Adaptive PSO-LSTM with the Sliding Window Approach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).