Abstract

(1) Background: This five-year systematic review seeks to assess the impact of oral and peri-oral photobiomodulation therapies (PBMTs) on the adjunctive management of deeper tissue biofunction, pathologies related to pain and inflammatory disorders and post-surgical events. (2) Methods: The search engines PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, EMBASE and EBSCO were used with appropriate Boolean operatives. The initial number of 14,932 articles was reduced to 261. Further exclusions performed to identify PBM therapy in third molar surgery, orthodontic and TMJ articles resulted in 19, 15 and 20 of these, respectively. Each paper was scrutinised to identify visible red–NIR laser wavelength PBM applications, concerning dosimetry and outcomes. (3) Results: A dataset analysis was employed using post hoc ANOVA and linear regression strategies, both with a Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05). The outcomes of articles related to oral surgery pain revealed a statistically significant relation between PBMT and a positive adjunct (p = 0.00625), whereas biofunction stimulation across all other groupings failed to establish a positive association for PBMT. (4) Conclusions: The lack of significance is suggested to be attributable to a lack of operational detail relating to laser operating parameters, together with variation in a consistent clinical technique. The adoption of a consistent parameter recording and the possible inclusion of laser data within ethical approval applications may help to address the shortcomings in the objective benefits of laser PBM.

1. Introduction

Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT), formerly known as low-level laser therapy, is the application of sub-ablative photonic energy to a tissue target for the therapeutic relief of pain and inflammation [1]. The influence of laser photobiomodulation (PBM) as a significant source of adjunctive therapy in clinical dentistry has now received growing acceptance through peer-reviewed research [2]. From early in vitro cellular analyses, the fundamental and downstream effects of the lower levels of photonic energy were observed to be below the threshold associated with damage to the cellular apparatus to be examined [3]. This has allowed for prescriptive applications of chosen wavelengths and appropriate light doses to be applied, both to influence the healing of post-surgical oral and dental conditions and as a stand-alone therapeutic management of inflammatory and syndromic pathologies [4].

The laser photoexcitation of target cellular structures may be seen as ineffective if the photon stream energy density is too low to influence any reaction; equally, if excessively high photoexcitation is delivered, such levels may prove cytotoxic. Between these extremes, an ascending positive reaction, termed biostimulation, contributes to increased cell performance [5]. Recent reviews of evidence-based data have also presented arguments to indicate a zone of inhibition consequent upon a light dose above an upper limit of biostimulation, but within a tolerable zone below that of any damaging cell effects [6]. This has been termed a hormetic response, and it is a generally favourable stress-induced characteristic of the response of many biological processes upon exposure to increasing amounts of a stressor [7].

Tissue trauma, surgery or pathology characterised by a level of inflammation as a primary reaction, associated negative aspects of pro-inflammatory biochemical and cellular mediators and aspects of inflammation including tissue swelling, pain and structural disruption all pose major clinical challenges to achieving resolution [8,9]. The three primary outcomes of PBM therapy within the confines of a defined clinical strategy are the mitigation of reduced inflammation and pain, analgesia and a process of optimal wound healing within the biological capacity of the tissues to respond, which is a process best described as uneventful [10].

Consensus on the fundamental principles that underpin PBM therapy to normal as well as impaired or dysfunctional tissue suggest that the application of a therapeutic light dose leads to a cellular response, mediated by mitochondrial mechanisms along with downstream effects within anatomical sites [11]. Studies have shown that these changes can modify the peak and duration of the pain and inflammatory responses to trauma or infection, as well as promote good quality, “uneventful” healing and tissue repair [12,13].

Mitochondria represent significant operators of many cellular physiological processes, within the inner membrane of which are located a series of five molecular complexes known collectively as the Electron Transport Chain (ETC). Within the mitochondrion, the ETC creates an electrochemical gradient that leads to the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through a complete system known as oxidative phosphorylation [14]. A by-product of this series of reactions stimulates the manufacture and release of nitric oxide (NO●) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn have an impact on local extracellular vasodilation and the cellular gene transcription of growth factors and local extracellular vasodilation, respectively [15]. Extended concepts of secondary intracellular effects include accentuated pro-mitotic pathways that promote cell division processes as well as enhance cellular resistance to stress or positive cell function. From this early work extended in vitro and in vivo animal studies, which led to human trial studies, together, these applications have provided an evidence base for the direct and indirect outcomes of a chosen specific sub-ablative damage threshold photoirradiation parameters dose [16]. Table 1 provides a summary of tissue and biochemical factors that may be influenced through PBM action.

Table 1.

Growth factors associated with PBM therapeutic irradiation, molecular targets and recorded outcomes.

The totality and extent of PBM-mediated activity remains the product of multi-factorial elements, such as the target tissue, target pathology, applied photonic dose (at surface/at depth), wavelength, irradiance (W/cm2), spot (irradiance) area size, spectral beam profile, gated or continuous wave modes, dose repetition and total energy delivered. Published studies have highlighted the inconsistency of PBM delivery, with a lack of consensus agreement in all clinical aspects of light therapy, resulting in a sizable contribution toward the wide variation in the reported supportive outcomes of PBMT and consequent potential lack of consensus regarding its effectiveness [17].

Opinions have been well established, through peer-review publications, to support the wide scope of PBM within all aspects of clinical dentistry [18,19,20,21].

The purpose of this systematic review was to consider three clinical entities in commonplace dental practice, each with differing aetiologies or reasons for treatment, and where randomised clinical trials exist to evaluate the adjunctive support of PBM in affecting the outcome. These are listed as follows:

- Temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome (TMJDS) may encompass a mixed and often complex aetiology, but common symptoms generally arise through muscle pain and spasms together with degrees of trismus; this may be representative of both an acute as well as a chronic inflammatory condition.

- The surgical removal of mandibular third molars, for whatever reason, may involve the incision and raising of a full muco-gingival flap and bone removal to assist in the location and delivery of the tooth. Such surgical intervention will provoke an acute inflammatory reaction, notably through observed post-operative swelling, trismus and pain.

- Orthodontic treatment—embracing appliance-based tooth movement and/or tooth arch expansion—offers an opportunity for otherwise stable and healthy supporting tissue to be reorganised to allow the passage of teeth to a new prescribed location in the dental arch. Inasmuch, there may be induced low-stress inflammation associated with such a therapy, and some levels of pain and discomfort are often experienced. In essence, however, the contribution of PBM therapy is claimed to accentuate the osseous and dental supportive soft tissue cellular activity and to promote reductions in pain episodes and the overall active treatment time.

Since each group may exhibit a differing symptomology, if at all, the application of laser PBM may be assumed to promote differing accents of tissue activity and responses, and thus provide some guidance to optimise the delivery parameters to be consistent with the outcome.

The null hypothesis is that within these three distinct therapy groups, each based upon differing degrees of an acute/chronic inflammatory response and PBM application technique, no appreciable differences exist in the outcome of such adjunctive therapy. For each treatment group of published RCTs, the following basic questions were considered:

- Does PBM positively affect and augment the successful outcome of treatment, commensurate with a statistically significant comparison when compared to a control?

- Where inconsistency exists between the three groups, is the outcome of PBM therapy predictability affected according to the underlying status of the treatment area in terms of inflammation or pathology?

- Where inconsistency exists between the groups, is the effectiveness of PBM affected by disparity in light-dose, irradiation spot size or other laser operating parameters?

In general, a systematic review, through the analysis of accepted published data, criteria and conclusions, may be seen as an evolving confirmation of the contemporary evidence base. The limitations of such an analysis derive from the completeness and discipline of the randomised clinical trials, concerning the delivery of the essentials of study reproducibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol of the present study was submitted and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO—CRD42024503029) and followed the guidelines of the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement for reports [22].

The PICOS questions relating to clinical studies are as follows [23]:

- (i)

- P (Participant): adult patients who received active clinical treatment, associated with one of the three groups of therapy.

- (ii)

- I (Intervention): laser-activated in-office adjunctive PBM therapy.

- (iii)

- C (Control): dental treatment undertaken to address the presenting clinical need, but without adjunctive PBM therapy.

- (iv)

- O (Outcome): clinical assessment of improved outcome and reduction in negative symptoms.

- (v)

- S (Study Type): Randomised clinical trial peer-reviewed published studies.

2.2. Search Strategy

An electronic database search was performed relating to the effects of laser PBM application associated with surgical tooth removal, TMJDS or orthodontic treatment. The data platforms used were ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane, Scopus and EBSCO, using the following MeSH terms and Boolean operators: (Photobiomodulation OR PBM OR LLLT OR Low level Laser) AND (soft tissue OR oral surgery OR buccal mucosa) for oral surgery, (Photobiomodulation OR PBM OR LLLT OR Low level Laser) AND (orthodontic OR maxillary expansion) for orthodontic tooth movement, (Photobiomodulation OR PBM OR LLLT OR Low level Laser) AND (TMJ) for TMJ, published after 2018. The last search for recently published papers was carried out in February 2024.

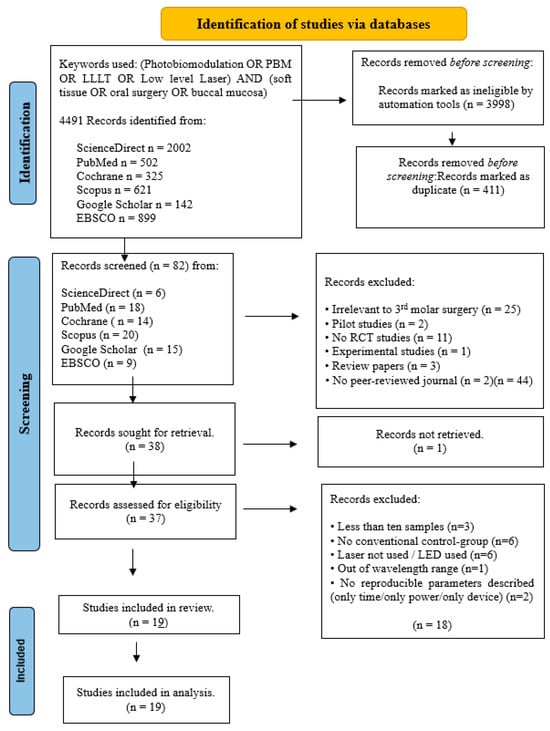

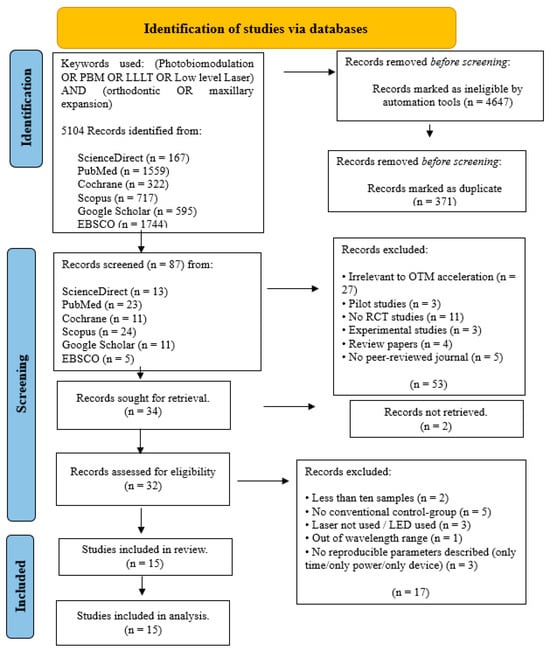

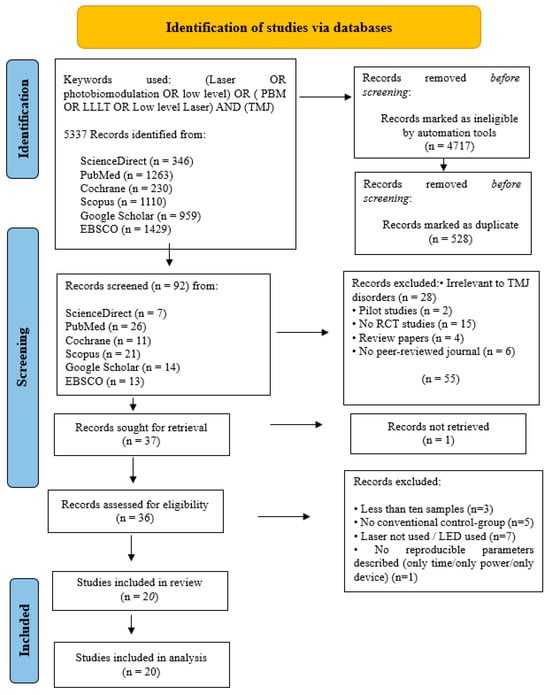

The initial article scanning delivered a total of 4491 for oral surgery, 5104 for orthodontic tooth movement and 5337 for TMJ.

After removing ineligible trial articles and duplicated reports, the remaining articles were 82 for oral surgery, 87 for orthodontic tooth movement and 92 for TMJ.

Subsequently, the titles and abstracts of these articles were independently screened by three reviewers (SP, EA, VM), using the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed below. Any disagreements that arose during this process were resolved through discussion between the researchers involved.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Randomised clinical trials;

- Laser PBM therapy associated with wavelengths in the range of 445–1064 nm;

- Articles were written in the English language;

- Control group and appropriate conventional non-PBM therapy;

- A minimum of 10 patients/samples per group;

- An adequate and appropriate protocol description.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Laser wavelength outside the range 445–1064 nm;

- Case studies;

- Narrative review papers;

- Languages other than English;

- Pilot studies and/or case series;

- Experimental studies;

- Animal studies;

- Conference presentation papers or book chapters;

- Editorial articles or opinions;

- Short notes or comments in erratum;

- Press articles in the press;

- Non-retrievable studies.

After the implementation of these criteria, 54 studies were included in this systematic review, spread across oral surgery (n = 19), orthodontic tooth movement (n = 15) and TMJ (n = 20).

In accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement [22], the details of the selection criteria are presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow-chart of selected criteria for the included oral surgery studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow-chart of selected criteria for the included orthodontic studies.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow-chart of selected criteria for the included TMJ studies.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted by the same three reviewers (S.P., E.A. and V.M, working independently) based on the following factors:

- Origin;

- Patient numbers represented in control and test groups;

- Use of randomisation and blinding;

- Laser wavelength applied;

- Laser operation parameters;

- Fluence (as calculated);

- Outcome (statistical significance).

2.4. Quality Assessment

A risk of bias assessment of all included articles was performed following the data extraction by the same independent reviewers (S.P, E.A. and V.M.). The requirements of the systematic review allowed the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [24] to be adequately modified. Applying the questions listed below provided either positive or negative responses, and these were tabulated and quantified to provide statistically relevant allocations of the bias risk.

The variables evaluated were the following:

- Randomization employed;

- Existence of sample size calculation and required sample number included;

- Blinding employed;

- Baseline situation similar for all groups;

- Laser operating parameters appropriately described, and any associated calculations correct;

- Optimal fluence applied;

- Power meter used to calibrate the laser used;

- Statistical analysis able to be applied to numerical results;

- Outcome data complete;

- Correct interpretation of data and results.

The determination of the degree of bias was based on the relative number of positive and negative responses, with the classification as follows:

- High risk: 0–4;

- Moderate risk: 5–7;

- Low risk: 8–10.

In case of any disagreements arising, these were resolved through discussions between the researchers involved.

3. Results

The results were classified according to each dental field as follows.

3.1. Oral Surgery

3.1.1. Primary Outcomes

The primary objectives of this systematic review were (a) to critically appraise the PBM irradiation protocols and (b) to examine the PBM treatment efficacy in terms of the pain, trismus and oedema reductions compared to those of the positive or negative control groups.

3.1.2. Data Presentation

The data extrapolated and evaluated from the included studies are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data extraction for oral surgery studies.

3.1.3. Quality Assessment

The risk of bias (ROB) assessment results for the oral surgery studies are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Modified risk of bias table for oral surgery studies.

The following are revealed in Table 3:

- Low risk of bias in 6/19 of the articles (31.6%):

- ▪

- One [34] scored 9/10;

- ▪

- Five [25,26,33,40,42] scored 8/10.

- Moderate risk of bias in 13/19 of the articles (68.4%):

- ▪

- Seven [27,28,29,30,31,32,38] scored 7/10;

- ▪

- Five [35,37,39,41,43] scored 6/10;

- ▪

- One [36] scored 5/10.

- High risk of bias in none of the studies.

Overall, the mean ± standard error (SEM) Cochrane risk of bias score parameter was 7.00 ± 0.23 out of a perfect value of 10 [95% confidence intervals: 6.52–7.48].

A power meter was employed in only one of the studies. The other negative answers most commonly found concerned (a) laser operating parameters described and correct calculations, and (b) optimal fluence applied, followed by (c) the sample size calculations and numbers included, (d) all relevant outcome data included and (e) a baseline situation similar for all groups.

3.1.4. Data Analysis

It is evident that a wide variety of laser irradiation protocols have been performed. Regarding the wavelengths applied, the vast majority were in the near-infrared range (789–980 nm), while five studies [31,34,35,36,40] examined a combination of red (632 nm or 660 nm) and infrared (810 nm) wavelengths.

As far as the other parameters are concerned in most of the studies, fluence was up to 30 J/cm2, treatment was performed in multiple repetitions, and the application was executed either intra-orally, or in a combination of intra- and extra-orally.

As for the treatment outcomes observed, 12/19 studies (63.2%) [25,26,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,38,39,41] presented a positive result, while 7/19 (36.8%) [27,29,36,37,40,42,43] showed no difference with the control group.

3.2. Orthodontic Movement

3.2.1. Primary Outcomes

The primary goals of this systematic review were (a) to critically appraise the PBM irradiation protocols and (b) to examine the PBM treatment efficacy in terms of speed of tooth movement compared to positive or negative control groups.

3.2.2. Data Presentation

The data extrapolated and evaluated from the included studies are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data extraction for orthodontic studies.

3.2.3. Quality Assessment

The risk of bias (ROB) assessment results for the examined studies are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Modified risk of bias table for orthodontic studies.

The following are revealed in Table 5:

- Low risk of bias in 7/15 of the articles (46.7%):

- Two [52,57] scored 9/10;

- Five [45,46,49,53,54] scored 8/10.

- Moderate risk of bias in 8/15 of the articles (53.3%):

- Seven [44,47,48,50,55,56,58] scored 7/10;

- One [51] scored 6/10.

- High risk of bias in none of the studies.

Overall, the mean ± standard error (SEM) Cochrane risk of bias score parameter was 7.50 ± 0.22 out of a perfect value of 10 [95% confidence intervals: 7.01–7.99].

A power meter was employed in only two of the studies. The other negative answers most commonly found concerned (a) laser operating parameters described and calculations correct, and (b) optimal fluence applied, followed by (c) the sample size calculations and numbers included, (d) the blinding of study researchers and (e) a baseline situation similar for all groups.

3.2.4. Data Analysis

It is evident that a wide variety of laser irradiation protocols have been performed. Regarding the wavelength applied, the vast majority was in the near infrared range (780–980 nm), while one study [50] examined a multi-panel system emitting polychromatic lights in the range of 450 nm to 835 nm.

As far as the other parameters are concerned in most of the studies, fluence was up to 30 J/cm2, treatment was performed in multiple repetitions, and the application was executed only intra-orally.

As for the treatment outcomes observed, 11/15 studies (73.3%) [44,45,46,48,49,50,52,53,55,56,58] presented a positive result, while 4/15 (26.7%) [47,51,54,57] showed no difference from the control group.

3.3. TMJ Studies

3.3.1. Primary Outcomes

The primary goals of this systematic review were (a) to critically appraise the PBM irradiation protocols and (b) to examine the PBM treatment efficacy in terms of pain and trismus reduction compared to positive or negative control groups.

3.3.2. Data Presentation

The data extrapolated and evaluated from the included studies are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Data extraction for TMJ studies.

3.3.3. Quality Assessment

The risk of bias (ROB) assessment results for the examined studies are outlined in Table 7.

Table 7.

Modified risk of bias table for TMJ studies.

The following are revealed in Table 7:

- Low risk of bias in 10/20 of the articles (50%):

- Three [64,71,73] scored 9/10;

- Seven [63,65,66,67,68,72,74] scored 8/10.

- Moderate risk of bias in 10/20 of the articles (50%):

- Eight [59,60,61,62,69,70,76,77] scored 7/10;

- One [78] scored 6/10;

- One [75] scored 5/10.

- High risk of bias in none of the studies.

Overall, the mean ± standard error (SEM) Cochrane risk of bias score parameter was 7.50 ± 0.22 out of a perfect value of 10 [95% confidence intervals: 7.03–7.97].

A power meter was employed in eight of the studies. The other negative answers most commonly found concerned (a) laser operating parameters described and calculations correct, and (b) optimal fluence applied, followed by (c) a baseline situation similar for all groups, and (d) the sample size calculations and numbers included.

3.3.4. Data Analysis

It is evident that a wide variety of laser irradiation protocols have been performed. Regarding the wavelength applied, the vast majority was in the near-infrared range (780–940 nm), while five studies [61,67,70,76,77] examined the red wavelengths, and two [59,60], the 1064 nm wavelength.

As far as the other parameters are concerned in most of the studies, the total fluence per session was up to 300 J/cm2, treatment was performed in multiple repetitions, and the application was executed only extra-orally.

As for the treatment outcomes observed, 12/20 studies (60%) [59,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,70,73,74,75] presented a positive result, while 8/20 (40%) [65,68,69,71,72,76,77,78] showed no difference from the control group.

4. Statistical Analysis

For the three separate group models outlined below, full datasets were primarily subjected to univariate data analysis in order to screen for those that appear to significantly contribute toward the outcome parameters (albeit in a univariate context). ANOVA and linear regression approaches were employed for this purpose, with the output variable being scored 0 for no difference from the control, and +1 for a statistically significant difference observed.

For the ANOVA and LR screening approaches, all publication data points were weighted according to the total number of participants recruited to the study, i.e., a total combination of those in the test and control groups.

Subsequently, these significant variables were then incorporated into Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R) or Discriminatory Analysis (PLS-DA) models for the significant ‘predictor’ variables in order to determine any multicollinearities (cross-correlations) between them. However, in following the univariate selection of variables, which were significant only for the oral surgery datasets examined, all of these multivariate models constructed were found to not be significantly validated (Q2 statistic values were close to or even less than zero for all models examined). The data analysis was summarised using XLSTAT2021 software BASIC+ (Addinsoft, Paris, France).

4.1. Oral Surgery

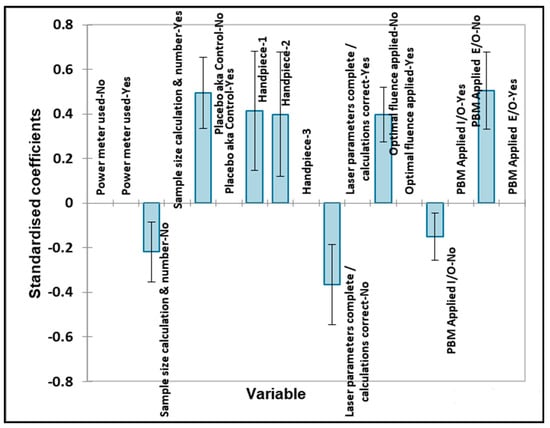

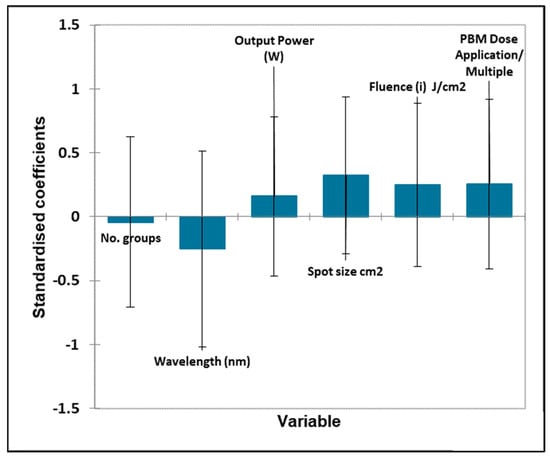

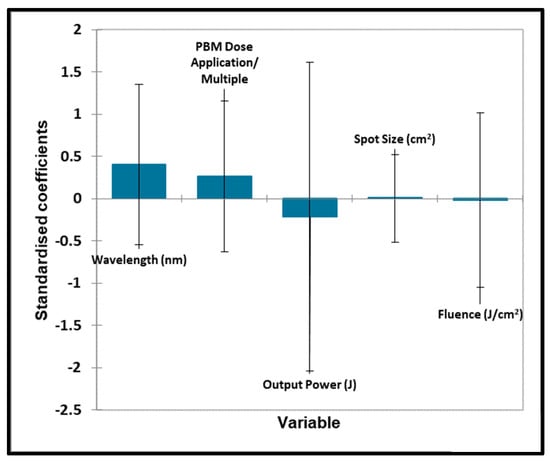

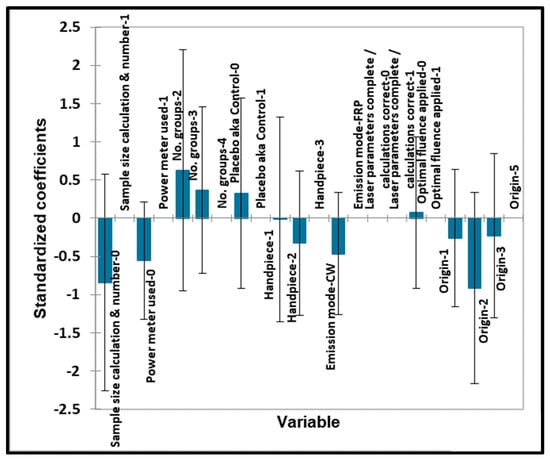

Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 concern oral surgery data pain (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and biostimulation (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Oral surgery quantitative variables—pain. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quantitative explanatory variables evaluated using the regression models employed for predicting the outcome variable for pain (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 5.

Oral surgery qualitative variables—pain. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for qualitative explanatory variables evaluated using the ANOVA models employed for predicting the outcome variable for pain (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 6.

Oral surgery quantitative variables—biostimulation. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quantitative explanatory variables evaluated using the regression models employed for predicting the outcome variable for biostimulation (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 7.

Oral surgery qualitative variables—biostimulation. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for qualitative explanatory variables evaluated using the ANOVA models employed for predicting the outcome variable for biostimulation (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

For the quantitative variables, the output power and wavelength were both statistically significant, with the positive effect increasing with the output power level but inversely related to the wavelength in nm, i.e., the lower the wavelength (and higher the energy) used, the better the effect. Fluence and spot size were also close to significance, with enhanced effects observed at higher fluences and larger spot sizes.

Significantly improved outcomes were found with the inclusion of a placebo (control) group, the use of handpieces #1 (bare fibre) and #2 (single tooth), the optimal application of fluence and no extraoral (E/O) PBM applied. Negative outcomes were significantly caused by no prior sample size calculation, no laser parameters being completed and no intraoral (I/O) PBM applied, as might be expected.

The Bonferroni-corrected p value required for statistical significance was found to be 0.00625, so therefore, all of the above significant variables were found to have a significant contributory effect on the pain outcome.

None of the quantitative variables were found to be statistically significant for this outcome score.

Again, no significant effects of any of the qualitative variables were found for the biostimulation output variable.

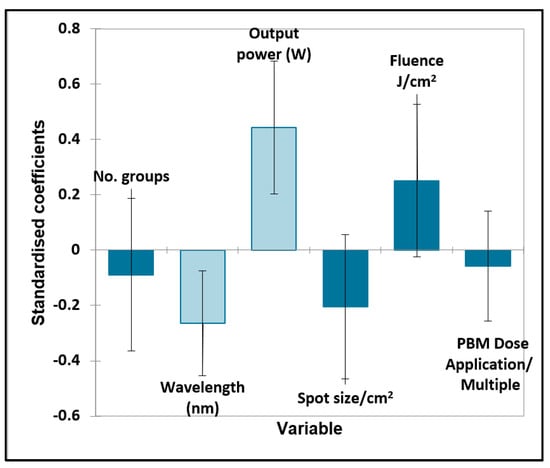

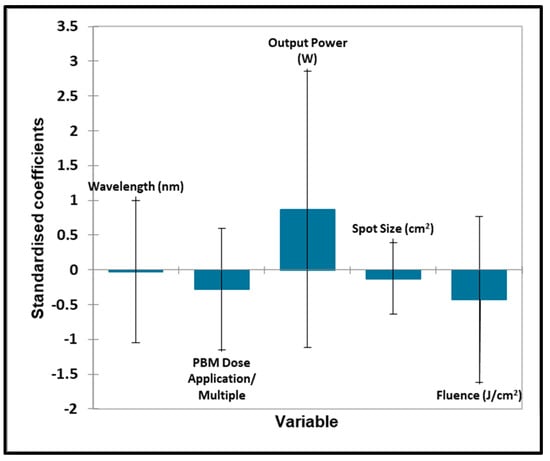

4.2. Orthodontic Tooth Movement

No significant contributions were found for any of the quantitative variables considered.

Respectively, an analysis of the qualitative variables associated with orthodontic tooth movement was performed. Unfortunately, this model was computationally blocked since there were too many variables and an insufficient number of studies reported. However, there were no significant correlations found between the outcome significance and all ‘predictive’ variables. Therefore, it can be attested that none of these variables significantly contributed toward the outcome variable (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Orthodontic tooth movement quantitative variables. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quantitative explanatory variables evaluated using the regression models employed for predicting the outcome variable for orthodontic tooth movement (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

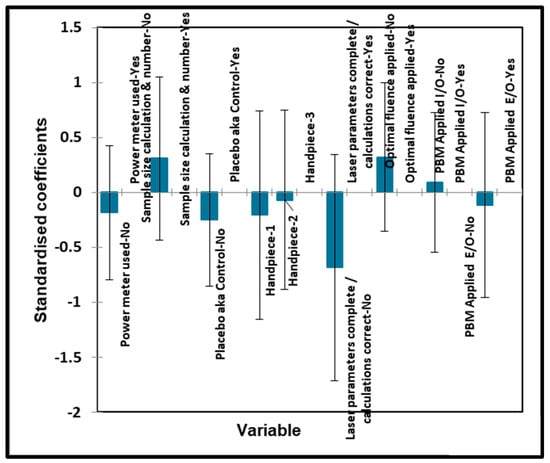

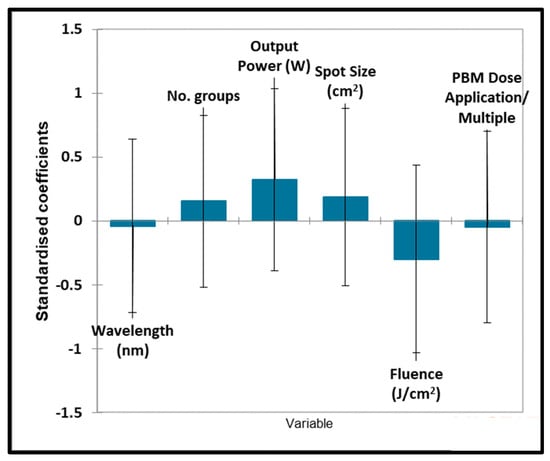

4.3. TMJ

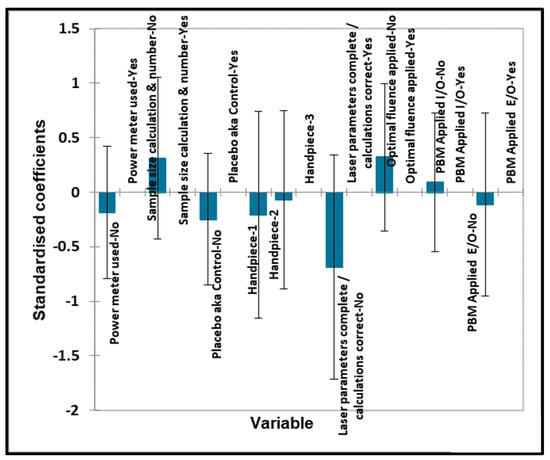

Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 concern the quantitative and qualitative variables associated with TMJ pain and the quantitative and qualitative variables associated with TMJ biostimulation, respectively.

Figure 9.

TMJ quantitative variables—pain. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quantitative explanatory variables evaluated using the regression models employed for predicting the outcome variable for pain (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 10.

TMJ qualitative variables—pain. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for qualitative explanatory variables evaluated using the ANOVA models employed for predicting the outcome variable for pain (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 11.

TMJ quantitative variables—biostimulation. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quantitative explanatory variables evaluated using the regression models employed for predicting the outcome variable for biostimulation (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Figure 12.

TMJ qualitative variables—biostimulation. Plot of estimated standardised coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for qualitative explanatory variables evaluated using the ANOVA models employed for predicting the outcome variable for biostimulation (0 for no effect, and +1 for a statistically significant influence).

Unfortunately, no significant contributions toward the outcome variable were found for all quantitative ‘predictor’ variables considered.

In Figure 9 and Figure 10, no significant contributions were found for any of the qualitative ‘predictor’ variables. No significant contributions were found for any of the quantitative ‘predictor’ variables evaluated. No significant contributions were found for any of the qualitative ‘predictor’ variables evaluated.

5. Discussion

Through a systematic review, this study developed an analysis of the many variables associated with PBM therapy, applied in three areas of dental/oral surgical treatments, using randomised clinical human trials [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. The basis of this investigation sought treatments related to the underlying nature of inflammation in general, whether acute, chronic or, in the case of elective orthodontic tooth movement, pre-operatively non-existent, to determine if any pertinent conclusions might be drawn. Although rather simplistic in its generalisation, the application of PBM may be seen to address conditions that are standalone pathologies or conditions contemporary with and consequent of surgical intervention with oral, dental hard and soft tissue diseases or trauma. As such, the presence of acute or chronic inflammation, with associated tissue imbalance (pain, oedema and trismus), may present an opportunity for beneficial PBM therapy. In addition, there may be opportunities to positively influence the status of otherwise ‘normal’ tissue that may be associated with a clinical procedure, such as orthodontic therapy as well as adjunctive applications associated with regenerative therapies such as stem cells [79] and the hard and soft tissue graft osseointegration of dental implants [80]; other areas of PBM influence include burning mouth syndrome [17], following nerve damage caused by oral surgery [81] and idiopathic tooth hypersensitivity [82,83].

The data extraction and groupings were subjected to a statistical evaluation in order to seek those elements of therapy that represent possible significance and allow meaningful comparisons to be identified. The focus of selection of published papers was to identify the empirical use of laser photobiomodulation within three areas of adjunctive therapy; the intention was to conduct a refine analysis to enable direct comparisons across the three treatment groups. Additionally, the short time frame of the published randomised clinical trials reflects the high level of research activity during the past five years; however, when compared to the extended span of decades of preceding research, it is questionable as to how little consensus has emerged in terms of a standardisation of laser application techniques, or of the many elements of a general PBM light dose during all phases of treatment.

The objectives of this systematic review originated around three areas of interest: ‘Was the influence of PBM therapy primarily related to the presenting condition?’, ‘Was any benefit influenced by the reported operating technique and surgical anatomy?’, and ‘Was any benefit of PBM therapy related to the chosen operating parameters?’. As seen from the statistical analysis, there appears to be no significant difference between the three treatment groups to allow for an indication regarding the comparative usefulness of PBM therapy with any underlying clinical condition. Therefore, to draw any significance concerning tissue status appears equivocal.

The prime PBM outcomes of reduced inflammation, analgesia and uneventful healing are potent claims that have been refined through many studies, offering the promise of adjunctive support in the clinical management of disease, disorder or injury. From Table 1, many biochemical mediators have been shown to be influenced through applied PBM therapy; although several areas of activity may be a consequence of an inflammatory response as a precursor to tissue repair, the influences of PBM may be judged as wide ranging.

The choice of three areas of treatment allows some analysis of the applied light doses to be conducted relative to the surgical site. Indeed, as has been researched extensively, the inherent Gaussian distribution of the majority of photonic emission beams, together with the anisotropic nature of oral and dental soft and hard tissue, has considerable effect on the potential attenuation of the surface applied dose, resulting in variable degrees of beam scattering, non-target absorption at depth and a consequently reduced fluence at sub-surface surgical sites [10,17]. The clinical objectives of biostimulation and/or pain mitigation relative to the three anatomically heterogenous treatment areas pose consequently differing dose delivery challenges to the clinician. Key to effective PBM at depth is the employment of an optimal surface fluence in order to accommodate the beam density reduction as it passes through tissue layers.

The influence of varying (non-PBM) treatment protocols, such as surgical access preferences or (orthodontic) appliance therapy, has been demonstrated to have influence on the outcomes [84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Across the three groups, the variation in clinical outcome, as a measure of the effective PBM application, however, appears to be related to the laser operating parameters. This may be related to and draws upon the inherent nature of the laser being used (wavelength, emission mode, delivery mechanism, output power range). Consequent to this, operator-applied permutations of an overall light dose (‘spot’ size, fluence, irradiation, average power) together with the dose regimen (frequency of application, repetition, total energy) may significantly influence the therapeutic benefits offered by PBM. A third area of influence may be seen in terms of the nature of the clinical condition (pathology, wound trauma, otherwise ‘normal’ tissue modulation), along with the anatomical site in terms of a possible three-dimensional irradiation, and the effects of photon absorption and scattering. However, with the exception of outcomes relating to oral surgical molar removal, no statistical significance was found.

The influences of variable elements may be considered as follows [91]:

Group structure—test/control/placebo: Many positive outcomes were reported in the included studies, albeit with little statistical significance. Within the orthodontic movement group, the majority of studies utilised a split-mouth design as a control; within the TMJ group, an element of significance related to the influence of a placebo photonic delivery. Hence, it appears that within third molar oral surgery studies, adjunctive PBM effects were measured against a pure surgical treatment, albeit with some variation in the applied light dose and intra-oral verses extra-oral differences.

Wavelength/emission mode: Across all groups, there appears no significance. Even allowing for the extensive emergence of PBM and PBM-type effects with short visible wavelengths, as well as mid- and far-IR, the choice of predominantly visible diode red and NIR wavelengths constitutes a logical choice. However, in view of the wide variation in applied fluences relative to tissue type and surgical site, there has been no opportunity to analyse differences in outcomes across the wavelength range chosen.

Power meter: According to recent primary research [92], the significant variation in the optic fibre delivery fluence arising from impurities may exert considerable influence. That only very few (in number) of the studies analysed cited the use of a power meter or calibration must be seen as a source of error in the results and outcomes of such studies.

Delivery/spot size: Across the groups, some variation was shown in the ‘spot’ size, i.e., beam diameter, along with contact versus non-contact tip-to-tissue application. Non-contact, non-focused beams will undergo considerable variation in irradiation, which, in tandem with the effects of a non-linear Gaussian spectral beam profile, impacts the fluence values with even short distances. In many instances, no record of such measurements occurred.

Applied fluence/computed/relative to therapeutic optimal dose: during the past twenty years, a gradual acceptance of photonic ‘dose’ values relative to cellular and then whole-tissue radiation has defined therapeutic PBM delivery. Biphasic light-dose delivery may provide biostimulation, with ascending energy density values leading to a hormetic zone associated with cellular/tissue inhibition; at higher levels, this may lead to permanent damaging effects. Allowing for a nominal standard deviation, the biostimulatory fluence is observed at 5 Joules/cm2; above 10 Joules/cm2, with an average of 15 Joules/cm2, cell/tissue inhibition may be observed. Moreover, an upper value of 30 Joules/cm2 has been proposed as the threshold of damaging effects. However, the biological capacity of tissues to withstand photo-induced stress is a function of the rate of the dose delivery, expressed as irradiance (W/cm2). High-intensity photon exposure induces a potential damaging photothermal response; conversely, the accumulated energy expressed as fluence (J/cm2) may be high with extended low-value irradiance settings, as well as with repeated treatments. From our analysis of all groups, there is wide and significant variation in the fluence values applied, with most instances citing low or sub-therapeutic values.

Application/number/repetition/relative to anatomical site and dose variation with depth: It has been seen earlier that because of the non-isotropic nature of oral soft and hard tissues, with dental hard tissue structures, considerable variation exists between the chosen laser wavelength and associated absorption of applied fluence. Additionally, such phenomena may influence the applied dose at depth, with the reduction in fluence approaching 70–90% at 10 mm in oral soft tissue. The analysis of the applied target dose at depth versus the surface value, across the treatment groups and individual treatment schedules, showed significant variation and may contribute to a compromise in the effectiveness of PBM irradiation at tissue depth.

Significance of outcomes: Taken individually or collectively, the measurable variation in laser-relevant elements needs to be considered and set against the outcomes of individual randomised clinical trials. The consequence of this strict systematic review raises the significance of RCT data in defining ongoing evidence-based knowledge and the application of PBM therapy in dentistry. It is outside the scope of this review to define the extent of discipline to be applied to the parameters of clinical PBM delivery, but the study design and full disclosure of the delivery values should still be fully evaluated at the ethical approval stage of studies.

6. Conclusions

An analysis of randomised clinical trials relating to photobiomodulation was carried out within a specific five-year period and within three areas of adjunctive therapy. A detailed data extraction and analyses have allowed the scrutiny of the inter-group differences of PBM effectiveness and revealed a common benefit of such adjunct therapy. The scrutiny of a large amount of data relating to recorded laser operating and calculated dose parameters has revealed inconsistent statistical differences, when data group comparisons were applied. From the evaluations of all aspects of this study, we conclude that PBM offers positive benefits in a wide range of clinical treatment modalities. However, in considering the current spread of data recording that exists within contemporary randomised clinical trials, and in agreement with other study findings, there is a substantive need for a standardisation in PBM therapy dose parameters. With greater discipline applied to effectively record such parameters and easier comparisons between RCT outcomes, the effectiveness and predictability of adjunctive PBM treatments may become more attainable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.P.; methodology, S.P., E.A. and V.M.; validation, E.A. and V.M.; formal analysis, S.P., E.A. and V.M.; investigation and data extraction, S.P., E.A. and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.P., V.M., E.A., M.C., E.L. and M.G.; statistical analysis, M.G.; visualisation, S.P.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cronshaw, M.; Mylona, V. Ch. 7. Photobiomodulation Therapy Within Clinical Dentistry: Theoretical and Applied Concepts. In Lasers in Dentistry—Current Concepts, 2nd ed.; Coluzzi, D., Parker, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; p. 175. ISBN 978-3-031-43337-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, M.R.; Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and Applications of the Anti-inflammatory Effects of Photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karu, T. Primary and Secondary Mechanisms of Action of Visible to Near-ir Radiation on Cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1999, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R.; Hamblin, M.R. The Nuts and Bolts of Low-level Laser (light) Therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekrazad, R.; Fekrazad, R.; Arany, P.R. Photobiomodulation Therapy in Clinical Dentistry. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Dhawan, G.; Kapoor, R.; Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, V. Hormesis: Wound Healing and Fibroblasts. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 184, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csaba, G. Hormesis and Immunity: A Review. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2018, 66, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarian, M.; Zulkefli, N.; Che Zain, M.; Maniam, S.; Fakurazi, S. A review with updated perspectives on in vitro and in vivo wound healing models. Turk. J. Biol. 2023, 47, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M.; Grootveld, M. Photobiomodulation Delivery Parameters in Dentistry: An Evidence-based Approach. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.; Ferraresi, C.; Huang, Y.; Freitas, L.; Carroll, J. Chapter 1: Photobiomodulation. In Low-Level Light Therapy, 1st ed.; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kuffler, D.P. Photobiomodulation in Promoting Wound Healing: A Review. Regen. Med. 2016, 11, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronshaw, M.; Parker, S.; Arany, P.R. Feeling the Heat: Evolutionary and Microbial Basis for the Analgesic Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation Therapy. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.-H.P.J. Enzymatic Regeneration and Conservation of ATP: Challenges and Opportunities. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, G.; Wilkinson, M.L.; Gow, A.J. Nitric Oxide Regulation of Cellular Metabolism: Adaptive Tuning of Cellular Energy. Nitric Oxide 2022, 131, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.-S.; Calderhead, R.G. Is Light-emitting Diode Phototherapy ((LED-LLLT) Really Effective? Laser Ther. 2011, 20, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronshaw, M.; Cronshaw, M.; Parker, S.; Anagnostaki, E.; Mylona, V.; Lynch, E.; Grootveld, M. Photobiomodulation Dose Parameters in Dentistry: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dompe, C.; Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M. Photobiomodulation-underlying Mechanism and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoro, L.H.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Wainwright, M.; Garcia, V.G. LASER in Periodontal Treatment: Is It an Effective Treatment or Science Fiction? Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35, e099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauark-Fontes, E.; Migliorati, C.A.; Epstein, J.B.; Bensadoun, R.-J.; Gueiros, L.A.M.; Carroll, J.; Ramalho, L.M.P.; Santos-Silva, A.R. Twenty-year Analysis of Photobiomodulation Clinical Studies for Oral Mucositis: A Scoping Review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2022, 135, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornaini, C.; Fornaini, C.; Arany, P.R.; Rocca, J.-P.; Merigo, E. Photobiomodulation in Pediatric Dentistry: A Current State-of-the-art. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The impact of PICO as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: A systematic review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.; da Silva, C.; de Paula, J.; de Oliveira, K.; de Siqueira, S.; de Freitas, P. Effectiveness of Laser Therapy and Laser Acupuncture on Treating Paraesthesia After Extraction of Lower Third Molars. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyfarth, S.; Silva Fraga, R.; Da Costa Fontes, K.B.F.; Guimarães, L.S.; Alves Antunes, L.A.; Antunes, L.S. Do Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy and Low-level Laser Therapy Influence Oral Health-related Quality of Life After Molar Extraction? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 8, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, E.; Barati, H.; Arbabi, M.R.; Jalali, B.; Moosavi, M.-S. Low-level Laser Therapy Using Laser Diode 940 Nm in the Mandibular Impacted Third Molar Surgery: Double-blind Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isolan, C.P.; de Kinalski, M.A.; de Leão, O.A.A.; Post, L.K.; Isolan, T.M.P.; dos Santos, M.B.F. Photobiomodulation Therapy Reduces Postoperative Pain After Third Molar Extractions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2020, 26, e341–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asutay, F.; Ozcan-Kucuk, A.; Alan, H.; Koparal, M. Three-dimensional Evaluation of the Effect of Low-level Laser Therapy on Facial Swelling After Lower Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bianchi Moraes, M.; de Gomes Oliveira, R.; Raldi, F.V.; Nascimento, R.D.; Santamaria, M.P.; Loureiro Sato, F.R. Does the Low-intensity Laser Protocol Affect Tissue Healing After Third Molar Removal? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 1920.e1–1920.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajerani, H.; Tabeie, F.; Alirezaei, A.; Keyvani, G.; Bemanali, M. Does Combined Low-level Laser and Light-emitting Diode Light Irradiation Reduce Pain, Swelling, and Trismus After Surgical Extraction of Mandibular Third Molars? A Randomized Double-blinded Crossover Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Andrade, K.; Martins, C.; Chaves, F.; Oliveira, D.; Sampieri, M. Effectiveness of low power laser in reducing postoperative signs and symptoms after third molar surgery: A triple-blind clinical trial. Braz. Dent. J. 2023, 34, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feslihan, E.; Eroglu, C.N. Can Photobiomodulation Therapy Be an Alternative to Methylprednisolone in Reducing Pain, Swelling, and Trismus After Removal of Impacted Third Molars? Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, A.; Eshghpour, M.; Danaeifar, N.; Abrishami, M.; Vahdatinia, F.; Fekrazad, R.; Fekrazad, R. Effect of Photobiomodulation on the Incidence of Alveolar Osteitis and Postoperative Pain Following Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Double-blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badravalli Gururaj, S.; Shankar, S.; Parveen, F.; Kunthur Chidambar, C.; Bhushan, K.S.; Prabhudev, C. Assessment of Healing and Pain Response at Mandibular Third Molar Extraction Sites with and Without Pre- and Postoperative Photobiomodulation at Red and Near-infrared Wavelengths: A Clinical Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14, S470–S474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, F.; Eshghpour, M.; Zare, R.; Ebrahimi, S.; Fallahrastegar, A.; Khaki, H. Effectiveness of Low-level Laser Irradiation in Reducing Pain and Accelerating Socket Healing After Undisturbed Tooth Extraction. J. Laser Med. Sci. 2020, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, S.; Messina, P.; Scardina, G.A. Effectiveness of Low-level Laser Therapy on Pain Intensity After Lower Third Molar Extraction. Int. J. Clin. Dent. 2019, 12, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Vidya, K.C.; Srikar, M.V.; Pathi, J.; Jaiswal, A. Effectiveness of Low-level Laser Therapy After Surgical Removal of Impacted Mandibular Third Molars: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Al-Adili, S. Low level laser therapy on postoperative trismus and swelling after surgical removal of impacted lower third molar. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.M.; Prado, L.F.; Santos, K.; Rodrigues, L.; Valladares-Neto, J.; de Torres, É.M.; Silva, M.A. Efficacy of Two Low-level Laser Therapy Protocols Following Lower Third Molar Surgery—A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2022, 35, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Saeed, A.; Al-Fakharany, A. Effect of single dose low-level laser therapy on some sequalae after impacted lower third molar surgery. Al-Azhar J. Dent. Sci. 2020, 23, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Peimani, A.; Sardari, F.; Sarafi, S.; Sarafi, S.; Aghdam, H.; Chiniforush, N. The evaluation of photobiomodulation by 980 nm diode laser on postoperative complications after third molar surgery. J. Regen. Reconstr. Restor. (Triple R) 2018, 3, x. [Google Scholar]

- Fakour, S.; Hashemzehi, H.; Jahantigh, H.; Arab, K.; Gholami, L. Adjunctive Low-level Laser Therapy Using 980-nm Diode Laser after Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Avicenna J. Clin. Med. 2020, 26, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivrajani, S.J.; Bhad, W.A. Effect of Low Intensity Laser Therapy (LILT) on MMP-9 Expression in Gingival Crevicular Fluid and Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Patients Undergoing Canine Retraction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadian, N.; Miresmaeili, A.; Borjali, M.; Salehisaheb, H.; Farhadian, M.; Rezaei-Soufi, L.; Alijani, S.; Soheilifar, S.; Farhadifard, H. The Effect of Intra-oral LED Device and Low-level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Orthod. 2021, 19, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalnunpuii, H.; Batra, P.; Sharma, K.; Srivastava, A.; Raghavan, S. Comparison of Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Adolescent Patients Undergoing Treatment by First Bicuspid Extraction and En-mass Retraction, Associated with Low Level Laser Therapy in Passive Self-ligating and Conventional Brackets: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, D.; Dalci, O.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Papadopoulou, A.K. The Effects of a Clinically Feasible Application of Low-level Laser Therapy on the Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Triple-blind, Split-mouth, Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 157, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Rajeh, N.; Hajeer, M.; Hamadah, O.; Ajaj, M. Evaluation of the acceleration, skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of low-level laser therapy combined with fixed posterior bite blocks in children with skeletal anterior open bite: A three-arm randomised controlled trial. Int. Orthod. 2022, 20, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérignon, B.; Bandiaky, O.N.; Fromont-Colson, C.; Renaudin, S.; Pere, M.; Badran, Z.; Cuny-Houchmand, M.; Soueidan, A. Effect of 970 Nm Low-level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Tooth Movement During Class II Intermaxillary Elastics Treatment: A RCT. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Nucera, R.; Leonardi, R.; Paiusco, A.; Baldoni, M.; Caccianiga, G. A Comparative Assessment of the Efficiency of Orthodontic Treatment with and Without Photobiomodulation During Mandibular Decrowding in Young Subjects: A Single-center, Single-blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, D.S.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; de Santos, C.O.; da Saraiva, M.C.P.; Marques, F.V.; Matsumoto, M.A.N.; Romano, F.L. Evaluation of Photobiomodulation Therapy to Accelerate Bone Formation in the Mid Palatal Suture After Rapid Palatal Expansion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, F.; El-Kenany, W.A.; Mowafy, M.; El-Kalza, A.R.; Guindi, M. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Effect of Two Low-level Laser Irradiation Protocols on the Rate of Canine Retraction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Briguglio, F.; Grassia, V.; Picciolo, G.; Fiorillo, L.; Fiorillo, L.; Matarese, G. Effectiveness of Low-level Laser Therapy During Tooth Movement: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Materials 2019, 12, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Pereira, S.C.; Alvarez Avila, F.E.; Pinzan, A.; Lima, L.M.; Storniolo-Souza, J.M.; Janson, G. Low Intensity Laser Influence on Orthodontic Movement: A Randomized Clinical and Radiographic Trial. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2020, 54, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yang, K. Clinical Research: Low-level Laser Therapy in Accelerating Orthodontic Tooth Movement. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, B.; Güldüren, K.; Kamiloğlu, B. Effect of Low-level Laser Therapy on Orthodontic Tooth Movement During Miniscrew-supported Maxillary Molar Distalization in Humans: A Single-blind, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellán, R.; Gómez, C.M.; Palma, J.C. Effects of Photobiomodulation on the Upper First Molar Intrusion Movement Using Mini-screws Anchorage: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, M.A. Effect of Photobiomodulation on Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Gingival Crevicular Fluid Cytokines in Adolescent Patients Undergoing Fixed Orthodontic Therapy. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 9, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, Ö.; Dündar, Ü.; Gökay, G.; Büyükbosna, M. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Different Treatment Modalities in Individuals with Painful Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement with Reduction: A Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 60, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekici, Ö.; Dündar, Ü.; Büyükbosna, M. Effectiveness of High-intensity Laser Therapy in Patients with Myogenic Temporomandibular Joint Disorder: A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, e90–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, D.; Thirupathy, M. Comparative Efficacy of Low-level Laser and TENS in the Symptomatic Relief of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shousha, T.M.; Mohamed Alayat, M.S.M.; Moustafa, I.M.; Moustafa, I.M. Effects of Low-level Laser Therapy Versus Soft Occlusive Splints on Mouth Opening and Surface Electromyography in Females with Temporomandibular Dysfunction: A Randomized-controlled Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, A.; Ahrari, F.; Fallahrastegar, A.; Daghestani, N. A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Low-level Laser Therapy (LLLT) and Laser Acupuncture Therapy (LAT) in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, F.T.; de Jesus, L.H.; Carrard, V.C.; Freddo, A.L.; Chaves, K.D.B.; Martins, M.D. Comparative Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation and Manual Therapy Alone or Combined in TMD Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.A.; de Melchior, M.O.; Magri, L.V.; Mazzetto, M.O. Can the Severity of Orofacial Myofunctional Conditions Interfere with the Response of Analgesia Promoted by Active or Placebo Low-level Laser Therapy? Cranio 2020, 38, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aisaiti, A.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, W.; Zhou, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, K. Effect of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Painful Temporomandibular Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, L.; Ferreira, R.; Resende, T.; Pacheco, J.; Salazar, F. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation in Temporomandibular Disorder-related Pain Using a 635 Nm Diode Laser: A Randomized, Blinded, and Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, L.V.; Carvalho, V.A.; Rodrigues, F.C.C.; Bataglion, C.; Leite-Panissi, C.R.A. Non-specific Effects and Clusters of Women with Painful TMD Responders and Non-responders to LLLT: Double-blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes da Silva Dias, W.C.F.; Cavalcanti, R.V.A.; Magalhães Junior, H.V.; de Pernambuco, L.A.; dos Santos Alves, G.Â. Effects of Photobiomodulation Combined with Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy on the Quality of Life of Individuals with Temporomandibular Disorder. Codas 2022, 34, e20200313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, S.; Srivastava, A.; Shivakumar, G.; Marrapodi, M.; Herford, A.; Cicciu, M.; Minervini, G. Comparative effectiveness of low-level laser therapy and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in symptomatic temporomandibular joint disorders: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengue Maggi Borges, R.; Steffen Cardoso, D.; Chuaste Flores, B.; Dimer da Luz, R.; Roberta Machado, C.; Pessoa Cerveira, G.; Boff Daitx, R.; Baptista Dohnert, M. Effects of Different Photobiomodulation Dosimetries on Temporomandibular Dysfunction: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maracci, L.M.; Stasiak, G.; de Chami, V.O.; Franciscatto, G.J.; de Milanesi, J.M.; Figueiró, C.; Silva, T.B.; Guimarães, M.B.; Marquezan, M. Treatment of Myofascial Pain with a Rapid Laser Therapy Protocol Compared to Occlusal Splint: A Double-blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Cranio 2020, 5, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Chami, V.; Maracci, L.M.; Tomazoni, F.; Centeno, A.C.T.; Porporatti, A.L.; Ferrazzo, V.A.; Marquezan, M. Rapid LLLT Protocol for Myofascial Pain and Mouth Opening Limitation Treatment in the Clinical Practice: An RCT. Cranio 2020, 4, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadershah, M.; Abdel-Alim, H.M.; Abdel-Alim, H.M.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Jan, A.M.; Elatrouni, A.; Jadu, F.M. Photobiomodulation Therapy for Myofascial Pain in Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction: A Double-blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourian, A.; Pourshahidi, S.; Sadrzadeh-Afshar, M.-S.; Ebrahimi, H. A Comparative Study of Low-level Laser Therapy and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation as an Adjunct to Pharmaceutical Therapy for Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Dent. 2019, 16, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.P.; Roy, S.K.; Semi, R.S.; Balasundaram, T. Efficacy of Low-level Laser Therapy in Management of Temporomandibular Joint Pain: A Double Blind and Placebo Controlled Trial. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2021, 3, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, S.; Awad, S.; Kamel, H.M. Comparative Evaluation of Low-level Laser Therapy (lllt) Versus Sodium Hyaluronate with Arthrocentesis in Management Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (tmd): A Clinical Randomized Controlled Study. Egypt. Dent. J. 2021, 67, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiomy, A.A.; Baiomy, A.; Farhat, M.; Helal, M.A. Efficacy of Occlusal Splints and Low-level Laser Therapy on the Mandibular Range of Motion in Subjects with Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement with Reduction. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2023, 13, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Diniz, I.; de Cara, S.; Pedroni, A.; Abe, G.; D’Almeida-Couto, R.; Lima, P.; Tedesco, T.; Moreira, M. Photobiomodulation of Dental Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Systematic Review. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, C.; Pansani, T.; Cardoso, L.; Ribeiro, I.; Silva-Sousa, Y.; de Souza Costa, C.; Basso, F. Photobiomodulation using LLLT and LED of cells involved in osseointegration and peri-implant soft tissue healing. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, A.; Moslemi, N. Efficacy of photobiomodulation therapy on neurosensory recovery in patients with inferior alveolar nerve injury following oral surgical procedures: A systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2021, 52, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Femiano, F.; Femiano, R.; Scotti, N.; Nucci, L.; Lo Giudice, A.; Grassia, V. The Use of Diode Low-Power Laser Therapy before In-Office Bleaching to Prevent Bleaching-Induced Tooth Sensitivity: A Clinical Double-Blind Randomized Study. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femiano, F.; Femiano, L.; Nucci, L.; Grassia, V.; Scotti, N.; Femiano, R. Evaluation of the Effectiveness on Dentin Hypersensitivity of Sodium Fluoride and a New Desensitizing Agent, Used Alone or in Combination with a Diode Laser: A Clinical Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosola, S.; Kim, Y.; Park, Y.; Giammarinaro, E.; Covani, U. Coronectomy of Mandibular Third Molar: Four Years of Follow-Up of 130 Cases. Medicina 2020, 56, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, R.; Rastogi, S.; Rohatgi, R.; Abdulrahman, B.; Dutta, S.; Giri, K. Does pedicle flap design influence the postoperative sequel of lower third molar surgery and quality of life? J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2022, 12, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DE Marco, G.; Lanza, A.; Cristache, C.; Capcha, E.; Espinoza, K.; Rullo, R.; Vernal, R.; Cafferata, E.; DI Francesco, F. The influence of flap design on patients’ experiencing pain, swelling, and trismus after mandibular third molar surgery: A scoping systematic review. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2021, 29, e20200932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilir, H.; Kurt, H. Influence of Stabilization Splint Thickness on Temporomandibular Disorders. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 35, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gikić, M.; Vrbanović, E.; Zlendić, M.; Alajbeg, I. Treatment responses in chronic temporomandibular patients depending on the treatment modalities and frequency of parafunctional behaviour. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supakomonnun, S.; Mitrirattanakul, S.; Chintavalakorn, R.; Saengfai, N. Influence of functional and esthetic expectations on orthodontic pain. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2023, 84, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrusio, C.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Blasi, A.; Leuci, S.; Adamo, D.; Nicolò, M. The effect of orthodontic treatment on periodontal tissue inflammation: A systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. Laser Photonic Energy Delivery in Clinical Dentistry: Scrutiny of Parameter Variables. Ph.D. Thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK, May 2023. Available online: https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/items/5a60b157-6d26-46ad-ab2a-657aebbef704 (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M.; Grootveld, M.; George, R.; Anagnostaki, E.; Mylona, V.; Chala, M.; Walsh, L.J. The Influence of Delivery Power Losses and Full Operating Parametry on the Effectiveness of Diode Visible–near Infra-red (445–1064 nm) Laser Therapy in Dentistry—A Multi-centre Investigation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).