Abstract

Ex vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy (eFuCM) is a promising new technique for real-time histological diagnosis, requiring minimal tissue preparation and avoiding tissue waste. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of eFuCM in identifying key liver biopsy lesions and patterns, and to assess the impact of eFuCM reading experience on diagnostic accuracy. Twenty-three fresh liver biopsies were analyzed using eFuCM to produce H&E-like digital images, which were reviewed by two pathologists and compared with a conventional H&E diagnosis. The liver architecture was clearly visible on the eFuCM images. Pathologist 1, with no prior eFuCM experience, achieved a substantial agreement with the H&E diagnosis (κ = 0.65), while Pathologist 2, with eFuCM experience, reached almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.88). However, lower agreement levels were found in the evaluation of inflammation. Importantly, tissue preparation for eFuCM did not compromise subsequent conventional histological processing. These findings suggest that eFuCM has great potential as a time- and material-saving tool in liver pathology, though its diagnostic accuracy improves with pathologist experience, indicating that there is a learning curve related to its use.

1. Introduction

Liver biopsy remains a pivotal part of daily practice for the diagnosis of several liver diseases. It also plays a critical role in acute hepatitis work-up and in the post-transplantation setting, situations in which timely pathologist feedback can be crucial. However, conventional biopsy processing through formalin fixation and paraffin embedding (FFPE) is still a time-consuming approach as it usually takes between 18 and 24 h.

Frozen section analysis has long been an essential diagnostic tool in surgical pathology. This widely used method offers histological diagnostic information in less than 30 min, which is particularly valuable during oncologic surgical procedures. Despite its usefulness, frozen sections have certain limitations such as the presence of artifacts and it is a material-consuming and costly procedure, requiring specialized equipment and skilled technicians and pathologists [1,2,3].

Ex vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy (eFuCM) VivaScope 2500M-G4 (MAVIG GmbH, Munich, Germany) has emerged in response, enabling real-time, high-resolution digital Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E)-like imaging of tissue specimens with cellular and subcellular detail [4]. It does not waste tissue, keeping all sample intact for further FFPE, H&E, histo- and immunohistochemical stains and/or molecular analysis, since it does not alter the tissue composition. In recent years, the non-invasive nature of eFuCM has allowed for faster intraoperative decision-making and simplifying intraoperative samples workflow as it reduces the need for traditional frozen section evaluation [4,5,6,7,8].

eFuCM is mainly used in Mohs intraoperative surgery for the assessment of the surgical margins of skin tumors and has shown good results [6,7,9]. It has also been used in the diagnosis of prostate, kidney and breast cancer with promising results [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Regarding the liver, few studies have been conducted to date. The initial studies involved a limited number of cases of liver pathology focused on neoplastic pathology, although they did not define it precisely [18]. Other studies have examined the utility of eFuCM in the transplantation setting [19], with only one study attempting to explore its usefulness in non-tumoral parenchyma by comparing different types of samples, both surgical and biopsy specimens [20]. None of these studies have considered the experience of the professional reading the eFuCM images.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the performance of Ex vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy on liver biopsies for the identification of basic lesions and patterns and the evaluation of the tissue integrity as well as to determine the influence of eFuCM image reading experience among pathologists.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Tissue Collection

We conducted a prospective study including 23 liver core biopsies obtained from fresh surgically removed livers using a 16 Gauge size BARD® MAX-CORE® disposable core biopsy instrument (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, EEUU). Core biopsies were performed on non-tumoral parenchyma, except in one case in which tumor representation was also obtained. Core biopsies were immediately immersed in saline-soaked solution until they were prepared for eFuCM imaging.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (Registration number HCB/2020/1165) and carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All data were handled anonymously.

2.2. Ex Vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy Sample Preparation and Image Acquisition

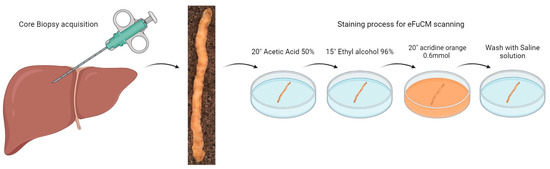

After biopsy acquisition, fresh liver tissue cores went through a quick staining process. Cylinders were immersed in acetic acid 50% for 20 s, then immersed in ethyl alcohol at 96° for 20 s and finally immersed in acridine orange 0.6 mmol for 20 s (Figure 1). After the sample was washed in saline the solution, it was placed on a magnetized glass slide and covered with a magnetized coverslip which immobilized the sample in the same position during eFuCM scanning.

Figure 1.

Sample acquisition and preparation for eFuCM visualization. After core biopsy acquisition, a fast-staining process was performed for further eFuCM scanning.

Fusion Confocal images were obtained using the fourth-generation VivaScope 2500. It simultaneously uses 2 lasers with wavelengths of 488 nm (blue, fluorescent signal) and 638 nm (infrared, reflection signal) and has a resolution image of 1024 × 1024 pixels. Acridine orange is excited by the blue laser and acetic acid produces a higher contrast at the reflectance signal. A built-in algorithm was used to fuse both laser signals and translate the fluorescent signal to blue color and the reflection signals to pink color, creating a H&E-like pseudo-colored image, similar to optical microscope images from conventional H&E staining.

2.3. Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Sample Analysis

After eFuCM image acquisition, scanned samples were immediately immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for routine processing, in order to be able to compare the eFuCM scanned images with the standard H&E pathological analysis. The samples were processed following the routine protocol for liver core biopsies at our pathology department, which includes a Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) stain as well as histochemical stains (Masson’s Trichrome and Reticulin). Samples were also tested for immunohistochemistry with both cytoplasmic (Hep-Par-1) and nuclear (Ki-67) antibodies. DNA and RNA extraction were performed to assess each sample’s quality and compare it with liver tissue which did not go through the eFuCM preparation stains.

2.4. Image Evaluation

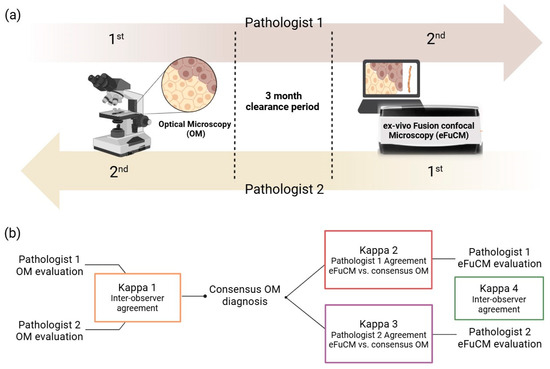

Both the H&E slides and eFuCM images were completely anonymized and blindly examined by 2 liver pathologists (one with eFuCM image reading experience and the other one without any experience), with a clearance period of three months between both techniques (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Histology evaluation process: Pathologist 1 first evaluated H&E slides and secondly eFuCM digital images, while Pathologist 2 first evaluated eFuCM images before finishing with the evaluation of H&E slides. (b) Results analysis algorithm: Both pathologist 1 and 2’s optical microscopy (OM) evaluations were compared, and the inter-observer agreement was calculated (Kappa 1). A consensus diagnosis of histological findings and patterns for OM evaluations was achieved to be compared with the individual eFuCM diagnosis (Kappa 2 and 3). Finally, the agreement between both pathologists for eFuCM-diagnosed histological patterns was calculated (Kappa 4).

Each pathologist recorded their findings in a preformed questionnaire. The presence of portal tracts and central veins was noted as well as the identification of arteries and bile ducts. The presence/absence of steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, fibrous septa and cirrhosis was recorded using a binary system (being 0 absent and 1 present). When present, the degree inflammation was evaluated in a 3-tiered system (1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe), differentiating between portal and lobular inflammation. When steatosis was present, it was graded in a semi-quantitative system according to the NASH Clinical Research Network System (1 = 5–33%; 2 = 33–66% and 3 > 66%) [21]. Although it was not the aim of the study, if a tumor was present it was noted. Finally, a pattern approach to diagnosis approximation was performed for acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, steatosis, cirrhosis, tumor or normal/minimal changes.

The conventional histological diagnoses of both pathologists were statistically compared. Their discordances were then assessed to reach a consensus diagnosis. Finally, the eFuCM diagnoses from each pathologist were compared with the consensus of the conventional H&E diagnosis (Figure 2b).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables and inter- and intra-observer agreement between both techniques were evaluated by unweighted Cohens Kappa statistic (Figure 2b), which calculates the degree of agreement expected by chance. Kappa is scored as a number between 0 and 1, where <0 is no agreement; 0–0.20 is slight agreement; 0.21–0.40 is fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 is moderate agreement; 0.61–0.8 is substantial agreement; 0.81–0.99 is almost perfect agreement; and 1 is perfect agreement. The software used for the statistical analysis was the R program (4.0.3 version; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

Our data set included a total of 23 biopsies from 22 patients, 12 men and 10 women, with a median age of 58.7 (range 23–81). All liver core biopsies were obtained from fresh liver surgical resections. Specimens were subsequently handled following the routine protocols to reach the pathological diagnosis. The type of specimen, the surgery indications and the final pathological diagnosis are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Type of specimens, surgery indication and final diagnosis of the cohort.

3.1. Characterization of Normal Liver Structures and Liver Tissue Integrity

It took an average of 3.3 min (1.4–5.2 min) to obtain an eFuCM digital H&E-like image from each 15 mm sized core biopsy.

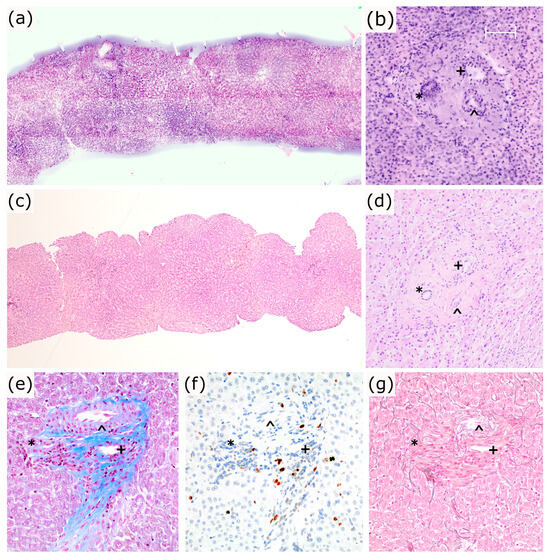

The basic liver architecture was easily identified on the eFuCM images, with the portal tracts and central veins being easily distinguished, as well as the capsule, if present (Figure 3a–d). It also allowed for the distinction of the main portal tract structures: bile ducts, arteries and portal veins. Sample preparation for eFuCM did not affect the posterior quality of the FFPE tissue. Histochemical and immunohistochemical stains had a good quality as well as both DNA and RNA, when compared with non eFuCM controls (Figure 3e–g).

Figure 3.

(a–d): Liver basic structure and tissue integrity. (a,b) eFuCM digital images and (c,d) 20× and 100×, respectively; H&E images from a liver core biopsy and a portal tract (*: bile duct; ^: artery; +: portal vein); (e–g): Same portal tract at 100×, stained with Masson’s Trichrome (e), Ki-67 (f) and Reticulin (g).

3.2. Characterization of the Main Liver Pathological Features by Optical Microscopy

Table 2 (Parts I and II) summarize the main histopathological findings and patterns identified by conventional microscopy as well as the degree of agreement between both pathologists. Overall, the pathologists’ agreement was substantial-to-perfect, except for the presence of lobular inflammation (κ = 0.55) and its degree (κ = 0.37).

Table 2.

Reproducibility of histopathologic features by conventional optical microscopy.

3.3. Reproducibility of Pathological Features and Patterns with eFuCM

After reaching a consensus diagnosis in discordant cases, the results were compared with individual eFuCM evaluations (Table 3). Pathologist 1, the non-eFuCM-experienced operator, had slight-to-fair levels of agreement for the presence of lobular inflammation (κ = 0.247), the grade of lobular inflammation (κ = 0.158) and the grade of portal inflammation (κ = 0.233). The agreement for the remaining features was moderate-to-substantial. Pathologist 2, the eFuCM-experienced operator, had a moderate-to-almost-perfect agreement for all the histopathological features, with lower kappa values for inflammation and steatosis grading.

Table 3.

Reproducibility of histopathologic features by Ex vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy.

A substantial agreement (κ = 0.650) was observed for the overall intra-observer agreement between eFuCM patterns diagnosis and conventional H&E for Pathologist 1 and an almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.88) for Pathologist 2. The overall inter-observer agreement for the eFuCM patterns diagnosis was moderate between Pathologist 1 and 2 (κ = 0.601). Table 4 shows intra-observer agreement for both pathologists 1 and 2 with the conventional microscopy consensus diagnosis for each diagnosis pattern. The inter-observer agreement (Kappa 4) for the eFuCM pattern evaluation was perfect (κ = 1) for chronic hepatitis and tumor, substantial for steatosis (κ = 0.746), and moderate for acute hepatitis patterns (κ = 0.556) or normal samples (κ = 0.468)

Table 4.

Reproducibility of histopathologic patterns by Ex vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy.

3.4. Additional Findings

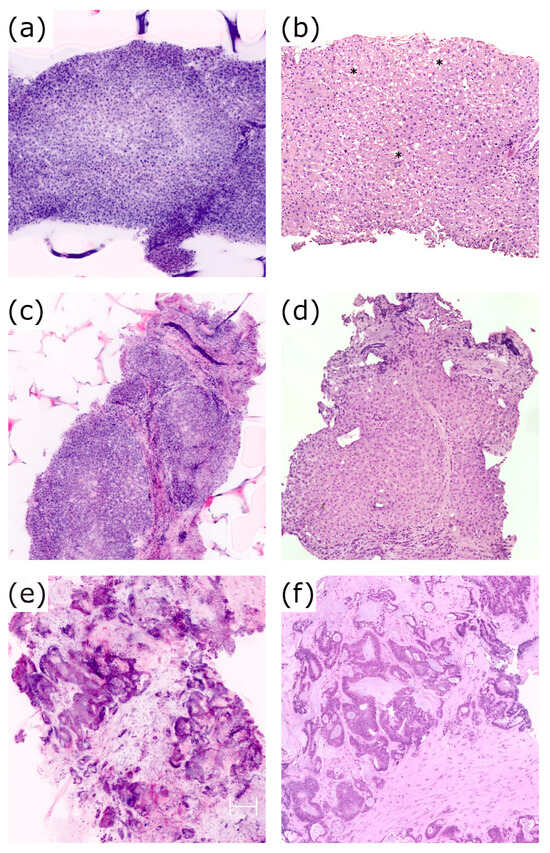

There was a total of seven discrepancies between the conventional H&E staining and eFuCM regarding pattern classification. Two of them were considered to be major discrepancies, corresponding to acute hepatitis which was misclassified as cirrhosis. In these cases, extensive areas of confluent necrosis were not easily identified on the eFuCM images, being confused with bands of fibrosis. The remaining discrepancies were considered to be minor and they consisted of a normal liver being misdiagnosed with very mild acute hepatitis on eFuCM (two cases), cirrhosis being classified as chronic hepatitis with advanced fibrosis (two cases) and mild steatosis not being identified on the eFuCM images (one case). Some of these situations are represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a,b): Case 14. Steatosis vacuoles (*) visible on H&E slides, 40× (b), which could not be correctly identified in eFuCM digital images (a); (c,d): Case 4. Stablished cirrhosis on eFuCM images (c) and in the H&E 40× (d); (e,f): Case 20. eFuCM image (e) and H&E 100× (f) of the colorectal carcinoma metastasis.

Additionally, cytoplasmatic changes in hepatocytes (ballooning, pigments or Mallory–Denk bodies) were hardly identifiable, even retrospectively as they were very subtle. Also, bilirrubinostasis could not be identified in the eFuCM images. Low degrees of fibrosis (less than F3) were not visible on the eFuCM images, or the H&E slides, with a Masson’s Trichrome stain being necessary in these cases.

Although we intentionally sampled non-tumoral livers, the biopsy from case 20 also contained a metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Neoplastic glandular structures were easily identified and compared with conventional H&E histology in that case (Figure 4e,f).

4. Discussion

Ex vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy (eFuCM) is a technique that provides high-resolution and real-time digital imaging of native tissues, resembling Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E)-stained slides. This technology has been increasingly utilized in surgical settings, particularly in dermatology and urology [6,9,13,22]. This prospective observational study is the first to specifically address the use of eFuCM for the diagnosis of fresh non-tumoral liver biopsies, while also examining the influence of pathologist experience with eFuCM, a factor that has not been previously explored.

Our findings demonstrate that eFuCM is well-suited for identifying fundamental liver structures and for detecting key non-neoplastic parenchymal changes such as cirrhosis, steatosis and portal inflammation, with generally acceptable levels of agreement compared to conventional histology. However, as we have shown, the accuracy of eFuCM interpretation is closely related to the pathologist’s familiarity with the technology. The significant discrepancy between conventional microscopy and eFuCM, observed in cases where the pathologist lacked prior experience, highlights the existence of a learning curve. This learning curve must be taken into account in future research and when implementing this technology in pathology departments for the liver as well as other tissues. Future research should involve multiple pathologists with varying levels of expertise in both conventional microscopy and eFuCM to achieve more reliable conclusions.

There were certain limitations in the agreement between eFuCM and the conventional liver pathology, particularly in assessing lobular inflammation, grading inflammation and staging fibrosis. Similar challenges have been observed in conventional H&E liver biopsy evaluations, with previous studies showing significant variability both between and within observers [22,23,24,25]. In our study, difficulties also arose in identifying the acute hepatitis pattern, and in two cases, it was impossible to distinguish between confluent necrosis and bridging fibrosis. This underscores the limitations of eFuCM in fully replacing conventional histochemical stains like Reticulin and Masson’s Trichrome, which are critical in liver pathology for fibrosis staging.

Only two previous studies have specifically addressed the usefulness of eFuCM for liver biopsies. Our findings align with those of Titze et al. [23] who reported an excellent suitability for tumor diagnosis (ĸ = 1.00) and a moderate-to-good suitability for assessing inflammation severity and localization (ĸ = 0.4–0.6), with similar limitations, such as challenges in evaluating cytoplasmic features. However, unlike our study, Titze et al. used various types of liver samples, not just liver core biopsies. The other study focused on intraoperative consultations for donor liver biopsies, demonstrating better correlations with eFuCM than conventional H&E staining [19]. eFuCM is emerging as an attractive alternative to using frozen sections for evaluating donor liver specimens, and it may also hold potential for intraoperative consultations, such as margin evaluation.

A significant strength of eFuCM is its ability to perform real-time histopathological diagnosis without losing tissue in the process, as occurs with conventional or frozen diagnosis procedures. As demonstrated in other pathologies where samples are scarce, such as renal biopsies [13,22], prostate biopsies [24,25] or small colorectal polyps [26], this technology can be useful for the rapid evaluation of liver core biopsies, where material is precious for additional IHC or molecular analysis. Additionally, we also confirmed that the eFuCM staining process and laser scanning did not affect tissue integrity or the IHC or molecular analysis.

Despite these strengths, the main limitation of this study is the need for specialized training in eFuCM analysis for liver pathologists, which added to the small sample size, may have influenced the learning curve of the inexperienced pathologist and contributed to lower levels of agreement. Nonetheless, we focused specifically on non-tumoral samples using a standardized collection method ensuring that all cases were based on the same type of biopsy. This methodology mirrors the liver biopsy samples typically received by pathology departments from emergency settings, contrasting with prior studies that included a variety of sample types [20,23].

Another limitation of eFuCM is that, despite its ability to provide fine-tuned real-time focusing similar to conventional microscopy, its imaging depth is limited to a few hundred microns. In this situation, simulating the diagnostic approach in conventional histopathological analysis of liver biopsies, which uses serial sections, may be challenging. Additionally, the different imaging contrast mechanisms used in eFuCM and optical microscopy [27] may also contributed to the observed variability in concordance between both techniques when evaluating certain histological features.

Despite its limitations, eFuCM shows promise as a time-efficient and tissue-preserving alternative to conventional histopathology, but further studies are needed to better understand its limitations and to optimize its integration into routine diagnostic practice.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the use of eFuCM for liver biopsy analysis and demonstrates the potential of this technology to open new diagnostic perspectives in liver pathology. This proof-of-concept study underscore the importance of proper training pathologists in emerging technologies, as there is a clear learning curve before achieving diagnostic proficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.-P. and A.D.; methodology, S.L.-P., R.M., C.F.-A., L.B. and A.D.; statistical analysis, S.L.-P.; data curation, C.F.-A. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.-P., C.F.-A. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, S.L.-P., C.F.-A., R.M., J.F.-F., O.B., M.C. and A.D.; supervision, A.D.; project administration, S.L.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (protocol code HCB/2020/1165 approved the 21 October of 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Javiera Pérez-Anker for generously sharing her valuable expertise in eFuCM with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Del Pilar, R.; Panqueva, L. Histopathological Evaluation of Liver Donors: An Approach to Intraoperative Consultation During Liver Transplantation. 2015. Available online: https://www.revistagastrocol.com/index.php/rcg/article/view/14/14 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Nackenhorst, M.C.; Kasiri, M.; Gollackner, B.; Regele, H. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy: Chances and Changes in the Analysis of Breast Tissue. Diagn. Pathol. 2022, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bahrawy, M.; Ganesan, R. Frozen Section in Gynaecology: Uses and Limitations. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instant Digital Pathology Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy ExVivo-with VivaScope® 2500. Available online: https://www.vivascope.com/instant-digital-pathology-ex-vivo/vivascope-2500-ex-vivo/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Braunschweig, T.; Knüchel-Clarke, R. Editorial for: Bertoni et al. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy: Prostatic and Periprostatic Tissues Atlas and Evaluation of the Learning Curve. Virchows Archiv. 2020, 476, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Anker, J.; Ribero, S.; Yélamos, O.; García-Herrera, A.; Alos, L.; Alejo, B.; Combalia, M.; Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Malvehy, J.; Puig, S. Basal Cell Carcinoma Characterization Using Fusion Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy: A Promising Change in Conventional Skin Histopathology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Anker, J.; Puig, S.; Malvehy, J. A Fast and Effective Option for Tissue Flattening: Optimizing Time and Efficacy in Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, e157–e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.C.; Fitzmaurice, M.; Reder, N.P.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kennedy, M.; Tearney, G.J.; Shevchuk-Chaban, M.M. Development of Functional Requirements for Ex Vivo Pathology Applications of In Vivo Microscopy Systems. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 143, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvehy, J.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Toll, A.; Pigem, R.; Garcia, A.; Alos, L.L.; Puig, S. Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy: Revolution in Fast Pathology in Dermatology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puliatti, S.; Bertoni, L.; Pirola, G.M.; Azzoni, P.; Bevilacqua, L.; Eissa, A.; Elsherbiny, A.; Sighinolfi, M.C.; Chester, J.; Kaleci, S.; et al. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy: The First Application for Real-Time Pathological Examination of Prostatic Tissue. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavlokhova, V.; Flechtenmacher, C.; Sandhu, S.; Vollmer, M.; Vollmer, A.; Saravi, B.; Engel, M.; Ristow, O.; Hoffmann, J.; Freudlsperger, C. Ex Vivo Fluorescent Confocal Microscopy Images of Oral Mucosa: Tissue Atlas and Evaluation of the Learning Curve. J. Biophotonics 2022, 15, e202100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kyrish, M.; Benveniste, A.P.; Yang, W.; Richards-Kortum, R. Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy for Rapid Evaluation of Invasive Tumor Cellularity of Inflammatory Breast Carcinoma Core Needle Biopsies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, J.Z.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Puig, S.; Pellacani, G.; Solé, M.; Malvehy, J.; Quintana, L.F.; García-Herrera, A. Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy Performs Real-Time Assessment of Renal Biopsy in Non-Neoplastic Diseases. J. Nephrol. 2020, 34, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoni, L.; Azzoni, P.; Reggiani, C.; Pisciotta, A.; Carnevale, G.; Chester, J.; Kaleci, S.; Reggiani Bonetti, L.; Cesinaro, A.M.; Longo, C.; et al. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy for Intraoperative, Real-Time Diagnosis of Cutaneous Inflammatory Diseases: A Preliminary Study. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavlokhova, V.; Flechtenmacher, C.; Sandhu, S.; Vollmer, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Engel, M.; Ristow, O.; Freudlsperger, C. Features of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovieno, A.; Longo, C.; De Luca, M.; Piana, S.; Fontana, L.; Ragazzi, M. Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy for Ex Vivo Diagnosis of Conjunctival Tumors: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 168, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, F.; Cinotti, E.; Yvorel, V.; Habougit, C.; Vassal, F.; Nuti, C.; Perrot, J.L.; Labeille, B.; Péoc’h, M. Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy Imaging to Identify Tumor Tissue on Freshly Removed Brain Sample. J. Neurooncol 2015, 124, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Sabir, S.; Ban, K.; Wu, Y.; Sheth, R.; Tam, A.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Shaw, K.; Mills, G.; Bassett, R.; et al. Comparison of Real-Time Fluorescence Confocal Digital Microscopy With Hematoxylin-Eosin–Stained Sections of Core-Needle Biopsy Specimens. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinzler, M.N.; Schulze, F.; Reitz, A.; Gretser, S.; Ziegler, P.; Shmorhun, O.; Friedrich-Rust, M.; Bojunga, J.; Zeuzem, S.; Schnitzbauer, A.A.; et al. Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy on Liver Specimens for Full Digitization of Transplant Pathology. Liver Transplant. 2023, 29, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Cortes, A.; Lopez, M.; Wallace, M.; Sabir, S.; Shaw, K.; Mills, G. Ex Vivo Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy for Rapid Evaluation of Tissues in Surgical Pathology Practice. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.-C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and Validation of a Histological Scoring System for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal, J.Z.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Puig, S.; Xipell, M.; Espinosa, G.; Barnadas, E.; Larque, A.B.; Malvehy, J.; Cervera, R.; Pereira, A.; et al. Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy Detects Basic Patterns of Acute and Chronic Lesions Using Fresh Kidney Samples. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze, U.; Sievert, K.D.; Titze, B.; Schulz, B.; Schlieker, H.; Madarasz, Z.; Weise, C.; Hansen, T. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy in Specimens of the Liver: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marenco, J.; Calatrava, A.; Casanova, J.; Claps, F.; Mascaros, J.; Wong, A.; Barrios, M.; Martin, I.; Rubio, J. Evaluation of Fluorescent Confocal Microscopy for Intraoperative Analysis of Prostate Biopsy Cores. Eur. Urol. Focus 2021, 7, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, K.D.; Hansen, T.; Titze, B.; Schulz, B.; Omran, A.; Brockkötter, L.; Gunnemann, A.; Titze, U. Ex Vivo Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy (FCM) of Prostate Biopsies Rethought: Opportunities of Intraoperative Examinations of MRI-Guided Targeted Biopsies in Routine Diagnostics. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.A.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Archilla, I.; Diaz, A.; Lopez-Prades, S.; Rodrigo-Calvo, M.; Lahoz, S.; Camps, J.; Puig, S.; et al. Ex Vivo Fusion Confocal Microscopy of Colorectal Polyps: A Fast Turnaround Time of Pathological Diagnosis. Pathobiology 2021, 88, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.W.; Maitland, K.C.; Rajadhyaksha, M.; Liu, J.T.C. In Vivo Microscopy as an Adjunctive Tool to Guide Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J. Biomed. Opt. 2022, 27, 040601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).