Abstract

Electronic evidence is an essential component in most legal trials of criminal activities, and digital forensics is therefore a crucial support for law enforcement investigations. For instance, a wide range of electronic devices contain Not AND (NAND) flash memory chips, and when a criminal leaves digital evidence on non-operational or locked systems, accessing this memory is crucial. Student acquisition of the necessary competences and skills associated with electronic devices, their basic principles, and the associated technologies can be provided by experimental training, as done with the optional Digital Forensics module included in the degree in Criminalistics: Forensic Sciences and Technologies offered by the University of Alcalá (Spain). This module equips students with the appropriate skills to extract, process, and authenticate evidence information using suitable tools. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of experimental learning, deployed through laboratory digital forensic tasks. A literature review was conducted of novel data extraction and analysis tools and procedures as a guide to the design of data recovery tasks incorporating experimental learning. Drawing on student feedback, our results highlight positive learning outcomes for the students. It is concluded that powerful forensic image analysis freeware is capable of identifying elements, and practical tests involving JTAG/chip−off extraction and analysis yield favorable results. A proposal for future studies is to reduce the destructiveness of invasive extraction methods.

1. Introduction

Electronic forensic research is a rapidly evolving field due to continuous technological advancements and the increasing prevalence of digital devices. Forensic science based on electronics, also known as digital forensics or computer forensics, is a branch of science focused on the identification, preservation, examination, and analysis of electronic data and digital devices. The main aim is to investigate and prevent cybercrime and to provide evidence in legal cases [1,2], and this requires the systematic collection and examination of digital data to uncover electronic evidence that can be used for investigative purposes and in court [3]. Furthermore, with the rapid growth of cybercrime, criminal investigators and law enforcement agencies increasingly rely on the expertise of digital forensic experts to examine confiscated data for evidence. Forensic research aimed at investigating criminal activities is a complex process that includes a stage dedicated to the acquisition and authentication of forensic copies and their subsequent analysis [4]. It is crucial to ensure the chain of custody, the integrity of the evidence, and the preservation and immutability of the original data [5,6]. Data acquisition should ensure the integrity of the original data, and each copy must be authenticated on creation to ensure support for the ultimate analysis results. As modern computer memories store large amounts of data, the challenge lies in discriminating between relevant and irrelevant information [7].

Digital forensic analysis, encompassing the preservation, identification, extraction, and documentation of digital evidence, is a relatively new and emerging academic discipline within information technology [2,8,9]. Despite demand for forensic technology specialists and the increasing number of postgraduate degrees in computer science and electronics, students often lack the necessary hands−on learning opportunities to acquire the kind of knowledge sought by employers. University criminalistics courses, for instance, mainly focus on theoretical principles and concepts rather than on practical applications [10].

A key emerging area in modern law enforcement is digital forensics, which aims to address the growing need for skilled professionals to handle increasing volumes of digital evidence. Particular challenges are posed by advanced technologies, like NAND flash memories, and by the current gaps in practical training in academic courses.

This research highlights the importance of electronic evidence in pursuing criminal activities and the crucial role played by appropriate digital forensics training. Its main contributions are based on a literature review that identifies novel tools and established data extraction procedures, and an exploration of innovative experimental learning methodologies, distinguishing between data recovery and data analysis tools. The importance of experimental learning for undergraduates is underscored as a means of developing key digital forensic skills, related to identifying electronic devices and associated technologies, and extracting, processing, and authenticating digital evidence from non−operational or locked systems. Providing students with hands−on experience in using advanced forensic tools and techniques bridges the gap between theory and practice, and ultimately enhances the effectiveness of real−world forensic investigations. This study’s findings and recommendations underscore the need for continuous adaptation to technological advances and the importance of enhancing forensic methods to ensure the integrity and reliability of digital evidence.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the tools and software for studying NAND flash memories; Section 3 describes the laboratory activities performed with students taking an optional digital forensics subject as part of a criminalistics degree; and Section 4 details the corresponding results. Finally, this paper ends by drawing some conclusions in Section 5.

2. Related Work

Criminals attempt to dispose of potential evidence by blocking devices or rendering them unusable. To demonstrate criminal activities from inaccessible or inoperative electronic devices equipped with NAND flash memories, advanced or destructive extraction techniques are usually required. However, deployed tools must be kept up to date due to the rapid and constant evolution of forensic technology, and this necessitates continuous adaptation. Specialized technologies focus on improving processing times, enhancing detection of explicit/sensitive content, expanding support for device models and memory types, and expediting information decryption, among others.

2.1. Data Extraction from NAND Flash Memories

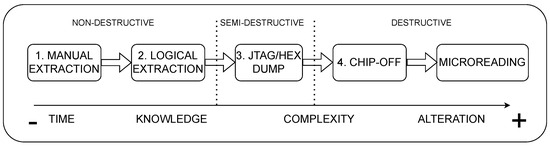

A wide variety of methods are available for data acquisition, depending on the degree of alteration of the original evidence. Methods can be classified according to cost, required time, or complexity, or according to the level of destructiveness, as depicted in Figure 1, which shows destructiveness ranked by levels from 1 to 5. For instance, if a device is neither damaged nor locked, it is preferable to employ a level 1 non−invasive technique to ensure the integrity of the original data [11]. The five levels are explained as follows:

Figure 1.

Data extraction methods, ranked 1 to 5, reflecting levels of destructiveness in terms of a sliding scale based on time, knowledge, complexity, and alteration [11].

- Level 1. Manual extraction. This involves a low−complexity, non−destructive, and thorough search for evidence. A locked device is its primary limitation. Additionally, manually navigating through evidence sources may affect data integrity. Tools such as ZRT Screen Capture [12] and Eclipse 3 Pro−Kit [13] can be used at this level.

- Level 2. Logical extraction. This is performed by connecting the device to a forensic workstation for data extraction using Oxygen Forensic Detective (OFD), Cellebrite, or OpenText EnCase Forensic (EnCase) software [14]. As a limitation, not all log files and data from analyzed devices are accessible.

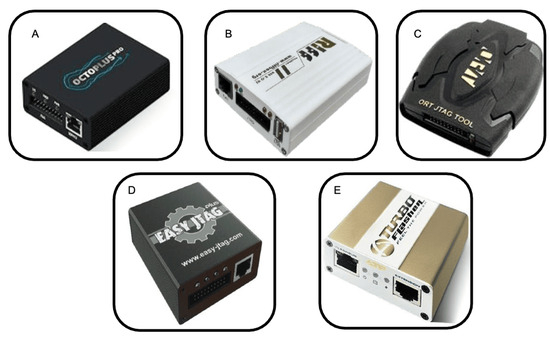

- Level 3. JTAG and HEX dump. This involves testing the circuits of memory cards, USB drives, SSDs, or eMMC devices and requires tools to disassemble devices and access their JTAG ports. The method is semi−destructive as it uses TAPs located on motherboards for functionality testing. Figure 2 shows various available commercial models. Although JTAG is primarily used in smartphone manufacture, it can also be employed to bypass OS−imposed access restrictions.

Figure 2. Commercial hardware platforms used for JTAG extraction: (A) Octoplus; (B) Riff Box; (C) Ort JTAG Tool; (D) Easy JTAG Box; and (E) Advanced Turbo Flasher (ATF) Box.

Figure 2. Commercial hardware platforms used for JTAG extraction: (A) Octoplus; (B) Riff Box; (C) Ort JTAG Tool; (D) Easy JTAG Box; and (E) Advanced Turbo Flasher (ATF) Box. - Level 4. Chip−off. This complex destructive technique involves physically extracting the device memory chip for reading using specialized equipment, e.g., RT809H, sourced from Shenzhen Sintech Electronic Co., Shenzhen, China. It is crucial not to damage the chip during extraction, as this could cause irreversible bit or even byte failures; this approach is therefore only recommended when less invasive methods cannot be used.

- Level 5. Microreading. This involves the physical observation of chips using scanning electron microscopy, e.g., JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. It is typically reserved for high−priority cases as it requires more resources, time, and expertise than the other extraction methods [6,15,16].

2.2. Data Analysis Tools

Of the tools available for forensic investigation, some are applied to specific tasks, while others are used for complete studies (i.e., acquisition, authentication, and analysis) [17,18]. The main tools used for data analysis are as follows:

- Oxygen Forensic Detective (OFD). This is used for logical and physical extractions, including data analysis and visualization in forensic image formats and in different types of electronic devices. OFD generates judicially admissible reports directly from the application and offers extensive support for Android devices and brute−force decryption of 7−Zip files. The main drawbacks are that it is an expensive and complex software [19].

- OpenText EnCase Forensic (EnCase). This software, which performs memory acquisition, data extraction, forensic report generation, and password recovery, is widely recognized by judicial departments and forensic research agencies. It supports a large number of mobile device and tablet models, and its latest version features EnCase Media Analyzer, which uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to identify and categorize the content of forensic images based on datasets. The generated reports employ a format admitted in judicial processes and also preserve the chain of custody for all the examined sources [20].

- Cellebrite Inseyets, Cellebrite UFED, and Cellebrite Digital Collector. These enable the recovery of deleted data, information decryption, and password extraction. Supporting a wide range of devices, including Android and Apple mobile devices, they can unlock devices and acquire logical and physical data. Inseyets integrates Universal Forensics Extraction Device (UFED) services with autonomy and quick−view technologies, which enable electronic device content to be viewed before creating forensic images, while novel capabilities allow for the simultaneous automation of multiple processes [21,22,23].

- Passware Kit Forensic (PKF). This enables the acquisition and processing of disk images and password recovery through brute−force, dictionary, and pattern attacks. PKF, useful when encrypted or locked data need to be accessed without using more invasive techniques, includes a resource manager that maximizes the performance of the analysis machine and an improved bootable memory imager mode, which creates memory images during computer startup. PKF does not include report generation suitable for judicial procedures, and support for mobile device processing is only included in the Ultimate edition [24,25].

- Belkasoft X Forensic (BXF). This enables the acquisition and authentication of NAND memory images through various analytical tasks (e.g., timelines and advanced searches). BXF, which supports numerous types of electronic devices and dump formats, can examine messaging applications, web browsing data, email inboxes, documents, images, video and audio files, file systems, and mobile applications. Processing times can be reduced through task automation and the use of specific search approaches. Additionally, BXF provides bit−level analysis through its HEX viewer and file system window, and BelkaCarving can recover and validate deleted, hidden, or corrupted information in databases [26].

- SANS Investigative Forensic Toolkit (SIFT). Available as a downloadable virtual machine, SIFT, a workstation designed for forensic analysis, uses key functionalities that include the Rekall Framework, Sleuth Kit, and Volatility. It offers extensive support for file systems and disk images, and comprehensive step−by−step documentation is available online [27].

- Sleuth Kit and Autopsy. Used to recover information and reconstruct scenarios, Sleuth Kit facilitates forensic image examination, file and directory analyses, keyword and file type searches, data recovery, and metadata verification. Autopsy, an open−source digital forensics platform that serves as a graphical interface for the Sleuth Kit functions, generates reports in various formats, such as HTML, Google Earth, KML, and Excel. However, it requires the use of additional tools for memory image acquisition [28].

- Toolsley. Designed to find hashes, identify file types, and analyze binary images using effective and straightforward tools, Toolsley’s simplicity is particularly advantageous for cases requiring urgent or remote investigation. However, notable drawbacks are that certain functions are outdated or formats may be incompatible [29].

- Forensic Tool Kit Imager Lite (FTK−IL). This is mainly used for data extraction and authentication from computers, mobile devices, and networks. Additional features are available under license, including password recovery and digital evidence integrity evaluation. It is widely used by judicial agents and administrative entities [30].

Table 1 lists the various types of software, their features (extraction, analysis, and reporting) and OS type (Android, MacOS, Linux, and Windows), together with reference works that use the proposed tools. Those commercial tools are capable of performing comprehensive analyses of the content from numerous electronic device types, although similar results can be achieved by combining the use of freeware options. Forensic copies can be extracted, data can be analyzed, and reports can be generated from devices running in different OSs for OFD, EnCase, Cellebrite, and BXF. PKF processes data and generates reports. SIFT is suitable for data extraction and analysis but does not support all types of forensic images or report generation. FTK−IL is similar to SIFT but differs in terms of extensive support. Lastly, neither Autopsy nor Toolsley is capable of acquiring forensic copies, but both tools are considered useful for analyzing data from binary images. Furthermore, Autopsy can generate highly detailed forensic reports.

Table 1.

Different types of supported tools and the related features categorized by specific features and OS type. (Note: ! indicates unavailable information. X, and ✓ indicate unavailable and available performance, respectively).

2.3. Practical Learning Context

Higher education in digital forensics is evolving to meet the demands of a rapidly changing technological landscape. The integration of novel techniques into academic settings is still in its early stages, with limited evidence on practical deployment despite promising proof−of−concept studies [48]. The integration of virtual laboratories and online resources allows for flexible learning environments, accommodating both on−site and remote students. While institutions are encouraged to share resources and best practices to enhance the quality and the accessibility of digital forensics education [49], the lack of cohesive educational frameworks remains a barrier to the effective training of future digital forensics professionals.

The use of experiential learning theory in designing a digital forensics curriculum has been shown to enhance the student learning experience [50]. Incorporating hands-on experience of working on various digital forensic research topics provides students with practical skills and a deeper understanding of investigative processes [51]. Experiential learning involves students engaging in practical tasks in which knowledge and skills reflecting real-world contexts are applied [52]. Following this pedagogical approach, instructors often take industry problems and adapt them to classroom projects. For instance, an emphasis on the importance of active participation and reflection contributes to the broader discourse on experiential learning, with experiential learning methods that foster meaningful, engaged learning in various educational contexts, e.g., through game-based approaches, shown to be particularly effective [53,54].

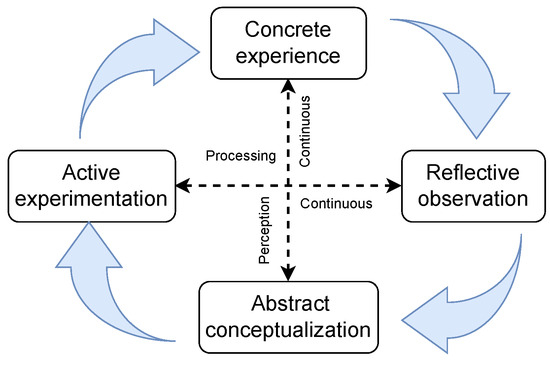

Figure 3 depicts the experiential learning cycle, whereby students gain relevant and practical skills from the design of practical, collaborative, and reflective learning experiences based on four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [55]. In the experience and observation stages, students, individually or in teams, actively engage in handling electronic devices and the associated software. The abstract conceptualization stage requires students to establish connections between laboratory work and learned theories from lectures and the ideas of peers and instructors. Finally, in the experimentation stage, students consider how learned lessons are applied in collaborative work scenarios.

Figure 3.

Kolb’s learning styles and the experiential learning cycle.

3. Methods

Classroom activities, based on qualitative and exploratory−descriptive evaluations, were carried out as part of the optional subject of digital forensics [56], a module in the undergraduate degree in Criminalistics: Forensic Sciences and Technologies offered by the University of Alcalá (Spain), with 13 enrolled students for the academic year 2023–2024.

The objective of this module is to introduce students to digital devices and data storage configurations. Students learn about the basic principles, technologies, and techniques of digital forensics by extracting data, applying processing techniques, implementing applications, and authenticating evidence from commonly used compact and mobile devices, as well as the necessary concepts for understanding how data are stored in semiconductor elements. In gaining practical experience with electronic storage devices by studying their functionality, the students acquire valuable insights into the field of forensic electronics.

This study is embedded in tasks completed in practical laboratory sessions. The concrete experience and reflective observation phases are implemented by the design and development of experimental setups, whereby students engage in assembling electronic circuits and exploring digital forensic techniques and tools. Experimental setups for forensic data analysis include non-volatile storage devices, such as hard drives and NAND memories, as well as mobile device analysis. This activity aims to foster reflective observation and abstract conceptualization. Different didactic modules are presented along with practical experiences, with students implementing the tools studied during the concrete experience and reflective observation phases.

3.1. Data Recovery

The extraction of evidence from potentially damaged storage devices is an increasingly common practice in forensic science, while the difficulty in directly reading data from devices requires the use of novel techniques. To familiarize students with retrieving information from storage systems, they perform 3 experimental tasks involving the extraction of data from memories, described in the following subsections.

3.1.1. MicroSD Card Data Extraction

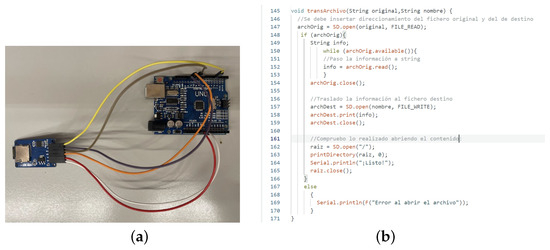

A simple open-source hardware platform (Arduino) is used for microSD card reading and writing actions. The experimental setup includes an additional SD memory card reader as depicted in Figure 4a. The activity involves reading and writing files to memory and creating a sketch to display the content of the files located in the source folder using the serial monitor. The data are captured using external software developed by the students (see example in Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Experimental setup for microSD memory extraction. (b) Software developed for file transfer.

3.1.2. NAND Memory Reading and Writing Capabilities

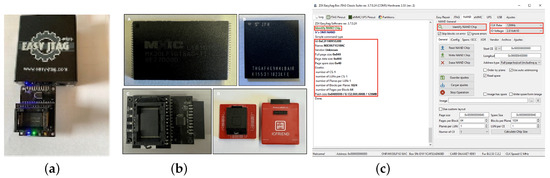

Figure 5 shows an example of memory reading by EasyTAG resulting in valuable information, e.g., erasure, memory size allocation, and read-write block configuration. The objective of the activity, based on NAND chips with TSOP and BGA encapsulations, is to explore memory characteristics (i.e., model, size, voltage, and operating frequency) before proceeding to reading and data extraction. Students use different evaluation boards and adapters to manipulate the NAND memory models and packages. The content is also extracted using JTAG and analyzed with forensic tools. Additional tools used are specific sockets, JTAG Classic Suite, HxD (freeware HEX editor and reader of binary images and files), Autopsy, Toolsley, PKF, AccessData, FTK-IL, and BXF.

Figure 5.

(a) Experimental setup for TSOP operations. (b) TSOP and BGA NAND memories. (c) EasyTAG software used for NAND memory analysis.

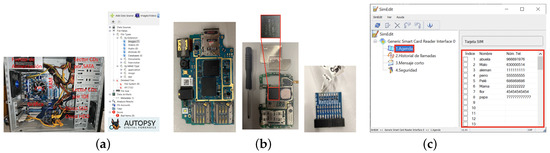

3.1.3. Information Extraction from Commercial Devices

Students identify different computer components and extract the storage devices for forensic analysis. Hard drive data analysis is performed by Autopsy and the content is backed up and cloned. Mobile phone terminals and unidentified boards are provided for data extraction, as shown in Figure 6a. Students obtain identification numbers (e.g., memory chips) to determine device model and characteristics. Using the unique mobile device identifier, information is retrieved and the storage components are analyzed to identify their JTAG connections, as shown in Figure 6b. Subsequently, pins are soldered to the corresponding socket to create a dump, i.e., a binary file containing a copy of the memory (commonly used in diagnosing and debugging issues in computer systems). Additionally, SIM card data (i.e., call logs, received/sent messages, etc.) are analyzed using SimEdit, as shown in Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental setup for hard disk content extraction and analysis by Autopsy. (b) Examples of mobile terminals for identification. (c) Board developed for memory reading by JTAG, with SimEdit used for the SIM card analysis.

Table 2 describes the main advantages and disadvantages of the proposed instruction method. Note that the advantages and disadvantages are likely to depend on the number of students, the complexity of the activity, and the time available.

Table 2.

Description of the main advantages and disadvantages of the proposed instruction method.

4. Results

Questionnaires regarding perceptions of the forensic laboratory, virtual classroom diaries to record comments and opinions, and questionnaires to evaluate technical knowledge were used to evaluate the experiential learning outcomes. Prior to questionnaire completion, the researcher (also the module instructor) informed the students that their responses would remain entirely anonymous. The students acknowledged their understanding of the activity as a research project component and consented to participate. To safeguard anonymity, any questions that could potentially reveal identifying information about the students were excluded.

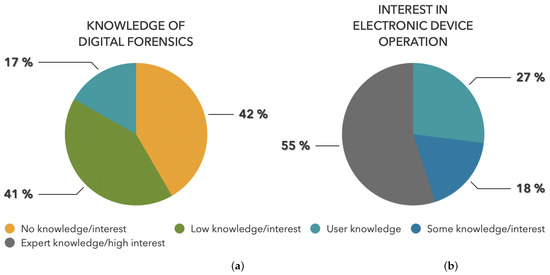

A preliminary questionnaire aimed to test their familiarity with programmable hardware devices and the term JTAG, how hard drives function, and the difference between RAM and ROM memory. The corresponding insights informed the teaching approach and helped tailor the content to the students’ knowledge.

The results, shown in Figure 7, indicated that around 42% of the students had no knowledge of digital forensics, and 80% had no familiarity with programmable devices or specific terminology, like JTAG. There was also an evident lack of training in inspecting internal components of devices. However, more than 70% of the students depicted a strong interest in understanding electronic device operation.

Figure 7.

Preliminary questionnaire results. (a) Digital forensics-related knowledge. (b) Interest in electronic device operation.

Experiential activities provided the students with the opportunity to apply the knowledge gained in theoretical classes. The students demonstrated significant motivation and interest in the laboratory activity involving the soldering of PCB components and successfully verified the proper functioning of the assembled PCB circuit. Regarding instruments and explanations provided for the precise soldering of electronic components using the hot-air technique, the students perceived this activity as not entirely suitable for teamwork. The need to demonstrate alternative methods and tools for forensic analysis, such as Arduino and other electronic devices, was highlighted, pointing to challenges to be resolved, such as instability in code execution (the required directories were not properly created). Furthermore, NAND memory data extraction equipment exhibited flaws and deficiencies leading to setbacks and errors and posing a challenge in terms of handling the equipment. Conceptually, manipulating NAND memories was entirely new for the students, and the equipment used presented certain difficulties in terms of compatibility with computer systems, resulting in occasional delays. This feedback was provided by the students, who suggested their own improvements to the organizational planning of the activity.

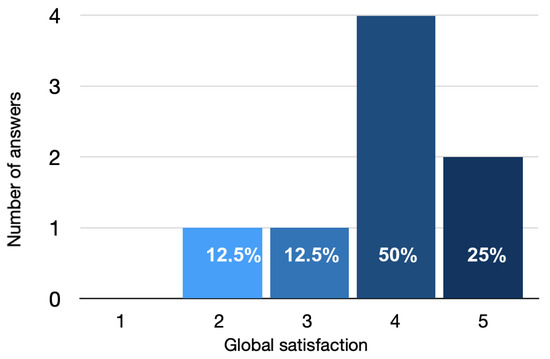

The practical activities aided student understanding of theoretical concepts, as indicated by an average satisfaction rating of 3.9 out of 5 (see Figure 8). Overall however, the students found the activities to be somewhat ambitious, given the equipment and laboratory time constraints.

Figure 8.

Satisfaction scores (%) regarding laboratory work as a reflection of theoretical content.75% of the responses mark a high and a very high satisfaction (y axis—number of answers and x axis—global satisfaction rate from 1 to 5).

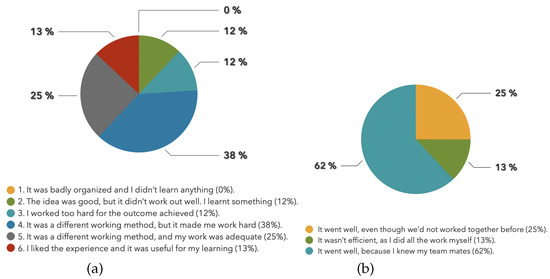

The laboratory activities were evaluated according to the six possible answers listed in Table 3. The feedback was positive overall for 76% of the students, as depicted in Figure 9a. The students also responded positively regarding the cross−cutting competency of teamwork, as shown in Figure 9b. Note, however, that only a few students completed the section of their reports that required them to discuss their main results and conclusions.

Table 3.

Possible answers for practice session feedback.

Figure 9.

(a) Feedback obtained for the final practice session (according to the statements in Table 3). (b) Feedback regarding teamwork.

Questionnaires were also issued for each activity to gauge participant satisfaction and feedback focused on variables, such as the experience of assembly and memory analysis, lessons learned, acquired knowledge of digital forensics, and familiarity with other learning tools.

Finally, student opinions were surveyed at the end of the module by means of 20 questions, 17 of which were responded to on a Likert scale, where 0 and 5 represented the lowest/most negative and highest/most positive scores (see Table 4). The 17 questions covered the suitability of the laboratory teaching format, understanding of the course objectives, usefulness of the learning activities, and student opinions as to their capacity to learn and understand content. Additionally, three open-ended questions were posed to collect information that could suggest future improvements: How would you improve the activities? Should additional activities be included in the disk and memory forensic analyses? Do you consider that improvements are needed that enhance learning effectiveness?

Table 4.

Final satisfaction survey results. (1 = lowest score; 5 = highest score). Averages were calculated based on response distribution.

Overall, the student responses to the 17 Likert-scored questions suggest that the hands-on laboratory activities were a highly effective method for teaching digital forensics. In their responses to the three open-ended questions, the students proposed additional laboratory sessions, given that “It’s not always possible to recover everything, nor it is always possible to determine 100% of the crime based on the evidence retrieved. The larger the volume of files to analyze, the more complex the investigation becomes”. The results also suggested a need for improvement in the organizational planning of activities, particularly in addressing challenges related to equipment and alternative methods and tools for forensic analysis. The experiential learning involving teamwork tasks such as data extraction, analysis, and reporting and hands-on tasks (e.g., desoldering complex NAND devices, such as TSOP or BGA), collaborative projects (e.g., resolving a fictional case), and reflective observation enhanced the understanding of concepts and the acquisition of practical digital forensic skills.

Student laboratory performance was relatively satisfactory (around 7 to 9 out of 10), indicating a good understanding and application of the activities. The few lower scores might suggest a struggle with challenges encountered during assembly experiments, as such activities require precision, attention to detail, and sometimes problem solving under time constraints, as shown during the microSD card data extraction activity.

Finally, the incorporation of experiential learning significantly deepened the understanding of theoretical concepts and equipped the students with the practical skills essential to accurately and confidently perform the experimental activities. In an evaluation based on a multiple-choice theory test (30 questions on a broad range of topics related to static, dynamic, and synchronous memory concepts; NAND memory operations and standards; digital forensics and inspection techniques and procedures such as ChipOff and JTAG; and hardware and electronics, such as Arduino, SD cards, chip desoldering, etc.), the tasks were well aligned with the skills required by the course. The assessment was appropriately challenging, yet accessible, for the majority of the students.

Discussion

The scientific validation of digital forensics methods and the growing complexity of cybercrime require the continuous development of advanced analytical tools, universal procedural standards, enhanced training, and a focus on ethical considerations [57]. Digital forensic laboratories face challenges encompassing technical, procedural, and organizational aspects of forensic analysis, given, in addition to overwhelming data volumes, the complexities of mobile devices, issues in standardization, legal ambiguities, and budget constraints [58]. Further hindering investigations is the need for skilled personnel to conduct advanced JTAG and chip-off analyses and the time required for forensic imaging of high-volume storage media. The development of 3D NAND memories and 5-bit cells allow for even greater device storage expansion, and this increase in data volumes poses a further challenge for forensic analysis.

Recent tools such as OFD, EnCase, Cellebrite Inseyets, Autopsy, and PKF have incorporated methods to expedite functions, such as preliminary content visualization that avoids exhaustive extractions (OFD and Cellebrite), or specific search approaches (Autopsy and BXF). EnCase employs artificial intelligence and machine learning to optimize file classification, and PKF has introduced resource managers and GPU acceleration. Overall, the analyzed tools have broadly similar functions; most allow for HEX viewing of image content but not Toolsley and PKF. PKF acquires relevant data but yields reports with limited information, potentially making the extra cost unnecessary.

Outcomes in terms of skills development and learning for the undergraduate students who engaged in experimental digital forensic activities were broadly positive. The fact that the tasks often involved real-world problem solving ensured a rich educational environment involving teamwork. The experimental activities resulted in the successful acquisition and analysis of forensic images from NAND chips using suitable tools and data extraction and evaluation using JTAG and chip-off techniques. Easy JTAG Plus was used to produce compatible forensic images with different tools, although skipping the physical chip extraction step overlooked the true challenge of this acquisition method. Overall, the hands-on lab activities and course projects fostered the kind of problem-solving and analytical skills in students that are fundamental to digital forensic investigations.

Despite limitations of being based on a small sample and being conducted in a specific educational setting, this study offers valuable preliminary insights into the effectiveness of experiential learning for digital forensics. The findings, however, should be interpreted with care and be validated through further research with a larger number of students. Qualitative data, such as student feedback and detailed case studies, could also provide important insights into the broader impact of the teaching methods. Furthermore, prospective studies that follow students over multiple semesters or years will increase the sample size and also provide insights into the long-term impact of the teaching methods.

5. Conclusions

Digital evidence is becoming increasingly relevant due to exponential growth in all the technological sciences, rendering precise digital forensics knowledge crucial. This review of tools and data extraction procedures covered highly comprehensive tools that are widely used in forensic investigations. Nevertheless, while those tools may indeed be useful, consolidating analyses performed by multiple tools could potentially enhance evidence reliability.

Instructors can usefully deploy experiential learning in the design of digital forensic laboratory experiences. Collaborative hands-on activities can dynamically and engagingly consolidate student knowledge and understanding of digital forensics, as demonstrated for the criminalistics undergraduate degree offered by the University of Alcalá, where outcomes were positive in terms of enhancing student skills and their understanding of real-world investigative processes.

Overall, incorporating experimental activities in digital forensics training not only enhances educational outcomes but also contributes to advancing practices and addressing challenges in the forensics field. Planned for future research is an evaluation of the capabilities of the studied tools in handling encrypted and/or explicit data, as such data frequently arise in criminal cases. Future research will also be conducted with a larger sample by more students or through collaborative online international learning (COIL) activities with other institutions.

Funding

Meriting special mention is the Erasmus+ project DECEL-Digital Electronics Collaborative Enhanced Learning (2021-1-ES01-KA220-HED-000032189).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the or Ethics Committee of University of Alcalá and date of approval 25 October 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following computer-related acronyms and abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| ATF | Advanced Turbo Flasher |

| BGA | Ball Grid Array |

| BXF | Belkasoft X Forensic |

| eMMC | Embedded Multi-Media Card |

| EnCase | OpenText EnCase Forensic |

| FTK-IL | Forensic Tool Kit Imager Lite |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HEX | Hexadecimal |

| HTML | HyperText Markup Language |

| JTAG | Joint Test Action Group |

| KML | Keyhole Markup Language |

| NAND | Not AND |

| OFD | Oxygen Forensic Detective |

| OS | Operating System |

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

| PKF | Passware Kit Forensic |

| RAM | Random-Access Memory |

| ROM | Read-Only Memory |

| SD | Secure Digital |

| SIFT | SANS Investigative Forensic Toolkit |

| SIM | Subscriber Identity Module |

| SSD | Solid-State Drive |

| TAP | Test Access Point |

| TSOP | Thin Small Outline Package |

| UFED | Universal Forensics Extraction Device |

| USB | Universal Serial Bus |

References

- Beebe, N. Digital Forensic Research: The Good, the Bad and the Unaddressed. In IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Bhatti, D.; Park, T.; Ishtiaq, H.; Ryou, J.; Kim, K. Cloud Digital Forensics: Beyond tools, techniques, and challenges. Sensors 2024, 24, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollitt, M. A history of digital forensics. In IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armoogum, S.; Khonje, P.; Li, X. Digital Forensics of Cyber Physical Systems and the Internet of Things; CRC Press eBooks: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, S.M. Introduction to digital forensics and commonly used technologies. Int. J. Electron. Crime Investig. 2018, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, R.; Skulkin, O.; Mahalik, H.; Bommisetty, S. Practical Mobile Forensics, 3rd ed.; O’Reilly Online Learning: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, K.; Meshram, B. Digital Forensic Investigation Tools and Procedures. Int. J. Comput. Netw. Inf. Secur. 2012, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, M.; Carr, C.; Gunsch, G. An examination of digital forensic models. Int. J. Digit. Evid. 2002, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fagbola, F.; Venter, H. Smart Digital Forensic Readiness model for shadow IoT devices. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, E.; Shumba, R. Teaching digital forensics and cyber investigations online: Our experiences. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2014, 10, 3986. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M. Mobile phone forensics—A systematic approach, tools, techniques and challenges. Int. J. Electron. Secur. Digit. Forensics 2021, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infosecinstitute. 2024. Available online: https://www.infosecinstitute.com/resources/digital-forensics/common-mobile-forensics-tools-techniques/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Sumuri. Sumuri Eclipse 3 Kit. 2024. Available online: https://sumuri.com/product/eclipse-3-kit/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Oxygenforensics. Oxygen Forensics Website. 2024. Available online: https://oxygenforensics.com/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Razdan, V. Chip-Off Technique in Mobile Forensics. Acad. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 5, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Savoldi, A.; Gubian, P. Data Recovery from Windows CE Based Handheld Devices. In Advances in Digital Forensics IV; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 285, pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Rosenberg, M.; D’Cruze, H. Integration of mobile forensic tool capabilities. In Information Technology—New Generations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 738, pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, C.M.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr.; de Oliveira Albuquerque, R.; Amvame Nze, G.D.; De Oliveira Júnior, G.A.; Sandoval Orozco, A.L.; García Villalba, L.J. Methodology for Forensics Data Reconstruction on Mobile Devices with Android Operating System Applying In-System Programming and Combination Firmware. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forensics, O. Oxygen Forensic Detective Release Notes 16.2. 2024. Available online: https://oxygenforensics.com/uploads/press_kit/OFDv162ReleaseNotes.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Opentext. Opentext EnCase Forensic. 2024. Available online: https://www.opentext.com/file_source/OpenText/en_US/PDF/opentext-po-encase-forensic-en.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Ahmed Alyas, A.; Kumar, V. Lawfully Data Collection Techniques in Mobile Forensic & Analysis Using Cellebrite Physical Analyzer. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4483864 (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Caballero, M.; Cilleros Serrano, D. Análisis Forense; Anaya Multimedia: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 692–711. [Google Scholar]

- Cellebrite. Cellebrite Inseyets. 2024. Available online: https://cellebrite.com/en/cellebrite-inseyets (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Passware. Passware Kit Forensic. 2024. Available online: https://www.passware.com/files/passware_kit_forensic_datasheet.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Azam, H.; Dulloo, M.; Majeed, M.; Wan, J.; Xin, L.; Sindiramutty, S. Cybercrime Unmasked: Investigating cases and digital evidence. Int. J. Emerg. Multidiscip. Comput. Sci. Artif. Intell. 2023, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkasoft. Belkasoft X Forensic. 2024. Available online: https://belkasoft.com/x (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- SANS. SIFT Workstation. 2024. Available online: https://www.sans.org/tools/sift-workstation/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Labs, S.K. Autopsy—Digital Forensics. 2024. Available online: https://www.autopsy.com/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Toolsley. Browser tools for the modern web. 2016. Available online: https://www.toolsley.com/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Exterro. Create Forensic Images with Exterro FTK Imager. 2024. Available online: https://www.exterro.com/digital-forensics-software/ftk-imager (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Parth, C.; Tamanna, J.; Kumar, A. Comparative analysis of mobile forensic proprietary tools: An application in forensic investigation. J. Forensic Sci. Res. 2022, 6, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tara, H.; Mishra, A. A comparative study of digital forensic tools for data extraction from electronic devices. J. Punjab Acad. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2021, 21, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riadi, I.; Yudhana, A.; Inngam Ganani, G. Comparative Analysis of Forensic Software on Android-based MiChat. J. Resti 2023, 7, 86–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Akbal, E. Analysis of mobile phones in digital forensics. In Proceedings of the 2017 40th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 22–26 May 2017; pp. 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluyo, A.; Cahyono, M.; Mahfud, A. Digital forensic analysis on caller ID spoofing attack. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Big Data and Information Security (IWBIS), Depok, Indonesia, 1–3 October 2022; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, A.; Azhar, M. Forensic acquisitions of WhatsApp data on popular mobile platforms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Security Technologies (EST), Washington, DC, USA, 3–5 September 2015; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, A.; Hannan Bin Azhar, M. Comparisons of Forensic Tools to Recover Ephemeral Data from iOS Apps Used for Cyberbullying. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Cyber-Technologies and Cyber-Systems (CYBER 2019), Porto, Portugal, 22–26 September 2019; pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Singh, V. Digital Forensic Investigation: Ontology, Methodology, and Technological Advancement; Apple Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, B. Evaluation of Open-Source & Proprietary Forensic Software Tools. Comput. Forensics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moric, Z.; Redzepagic, J.; Gatti, F. Enterprise Tools for Data Forensics 2021. In Proceedings of the DAAAM International Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 28–29 October 2021; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman Javed, A.; Ahmed, W.; Alazab, M.; Jalil, Z.; Kifayat, K.; Gadekallu, T. A comprehensive survey on computer forensics: State-of-the-Art, tools, techniques, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 11065–11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, R.; Lobo, K.; Ghelani, M.; Sujan, D.; Shirole, M. Comparative analysis of commercial and open source mobile device forensic tools. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Contemporary Computing (IC3), Noida, India, 11–13 August 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, J.; Zargari, S. Memory Forensics. Lat. Am. J. Comput. 2022, 9, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, M.; Jani, S. Memory forensic: Acquisition and analysis of memory and its tools comparison. Commun. Integr. Netw. Signal Process. 2018, 5, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabaawi, A. Digital forensics for infected computer disk and memory: Acquire, analyse, and report. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 16–18 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, H.; Bhatt, S.; Negi, L. Digital Forensics Techniques and Trends: A Review. Int. Arab. J. Inf. Technol. 2023, 20, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.; Spathoulas, G.; Anagnostopoulos, M.; Ghosal, A.; Borocz, I.; Patsakis, C. Research trends, challenges, and emerging topics in digital forensics: A review of reviews. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 25464–25493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Davies, R.; Reddy, M. Using digital forensics in higher education to detect academic misconduct. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2022, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, I.; Wood, E.; Nagy, S.; Garcia, G.; Bashir, M.; Campbell, R. Digital Forensics Education: A Multidisciplinary Curriculum Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–8 October 2015; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Namin, A.; Tavakoli, N.; Siami-Namini, S.; Jones, K. Using experiential learning to teach and learn digital forensics: Educator and student perspectives. Comput. Educ. Open 2021, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.; Blauw, F. An augmented reality approach to delivering a connected digital forensics training experience. In Proceedings of the Information Science and Applications: ICISA 2019, Singapore, 16–18 December 2019; Volume 621, pp. 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.; Williams, C. Experiential learning: Past and present. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1994, 62, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Hsu, Y.; Lai, C.; Chen, F.; Yang, M. Applying Game-Based Experiential Learning to Comprehensive Sustainable Development-Based Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, J. What is Experiential Learning; Nichols Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 9, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, T. Experiential learning–a systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Alcalá. Teaching Guide of Electronic Forensic; University of Alcalá: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.; Anwar, A.; Khan, A. Current Issues and Challenges with Scientific Validation of Digital Evidence. Rev. Comput. Eng. Stud. 2022, 9, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, H.; AlSharaiah, M.; Alkalaileh, M.; Dweikat, F. Overview of Challenges Faced by Digital Forensic. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26–28 February 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).