Abstract

As the significance of meticulous and precise map creation grows in modern Geographic Information Systems (GISs), urban planning, disaster response, and other domains, the necessity for sophisticated map generation technology has become increasingly evident. In response to this demand, this paper puts forward a technique based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for converting aerial imagery into high-quality maps. The proposed method, comprising a generator and a discriminator, introduces novel strategies to overcome existing challenges; namely, the use of a Canny edge detector and Residual Blocks. The proposed loss function enhances the generator’s performance by assigning greater weight to edge regions using the Canny edge map and eliminating superfluous information. This approach enhances the visual quality of the generated maps and ensures the accurate capture of fine details. The experimental results demonstrate that this method generates maps of superior visual quality, achieving outstanding performance compared to existing methodologies. The results show that the proposed technology has significant potential for practical applications in a range of real-world scenarios.

1. Introduction

In modern fields such as Geographic Information Systems (GISs), urban planning, and disaster response, accurate and detailed maps play a pivotal role. Maps provide a visual representation of geographic spaces, allowing complex spatial information to be interpreted and utilized for decision-making processes in various domains. In rapidly urbanizing societies, precise mapping data are essential for the planning and development of new residential areas, commercial facilities, and transportation networks. Beyond simple topographical information, these maps support critical decision-making in infrastructure management, transportation planning, resource allocation, and emergency response strategies [1,2].

Aerial imagery, especially with the aid of UAVs and modern high-resolution sensors, provides a distinct advantage over traditional cartography for generating detailed maps and accurate geographic models [3,4]. Traditional map-making methods are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and struggle to keep up with the rapidly changing landscape. As urban development accelerates, the need for real-time map updates becomes urgent, yet traditional methods fall short of keeping pace. This delay results in inefficiencies in urban planning, resource management, and transportation network expansion. In emergency response scenarios, the lack of up-to-date map information significantly hampers the ability to deploy resources swiftly. Consequently, there is a growing demand for automated systems capable of rapidly processing spatial data and generating real-time maps that reflect the latest geographical changes [5].

One promising solution is the automated generation of maps from aerial images. Aerial images offer high-resolution, large-scale data covering extensive areas, with detailed information about roads, buildings, and natural landscapes. These attributes make aerial imagery a valuable resource for urban planning and disaster management. Converting aerial images into map representations can dramatically improve both the speed and accuracy of map creation, making it possible to incorporate the most current spatial information. Thus, techniques for automatically mapping aerial imagery have the potential to extend beyond traditional map-making and serve as valuable assets with significant social impact.

In recent years, image-to-image translation techniques [6,7,8,9,10,11] have gained attention for their applicability in transforming aerial imagery into map representations. Image-to-image translation is a process by which one type of image is converted into another, and in this context, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have shown remarkable effectiveness. A GAN comprises two adversarial neural networks: a generator, which creates new images, and a discriminator, which distinguishes between generated and real images. The adversarial structure of GANs enables them to produce increasingly realistic images, making GANs well-suited for the automatic generation of maps from aerial images [12].

However, applying GANs to aerial-to-map translation presents certain challenges, primarily in preserving critical details such as road networks, boundaries, and other key infrastructural elements. These details are crucial in domains like urban planning, transportation network design, and disaster response. If such details are lost, the accuracy and reliability of the generated maps can be significantly compromised. For example, a map lacking a clear representation of road networks may hinder transportation planning, and indistinct building boundaries can reduce the map’s utility during disaster response, where precise infrastructure information is essential. Although existing GAN-based methods have attempted to address these issues, they often fall short of fully preserving essential details, necessitating further research to develop improved methodologies.

This study proposes a novel GAN-based map generation approach designed to address these issues. The proposed method is specifically structured to preserve critical details, such as road networks and building boundaries, during the transformation of aerial images into map formats. To achieve this, we introduce Residual Blocks into the generator network and employ a loss function based on the Canny edge detector to enhance edge detail preservation. In this approach, the Canny edge detector incorporates convolution operations to implement the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) process, enabling faster and more accurate convergence compared to traditional algorithms. Residual Blocks mitigate information loss and suppress unnecessary noise during the GAN training process, while the Canny edge detector effectively extracts and reinforces essential edge features like roads and building boundaries. Together, these components enable the proposed model to address the detail preservation challenges encountered by existing methods and improve the performance of map generation.

The primary objective of this research is to generate high-quality map data from aerial images, enhancing practical utility for urban planning, infrastructure management, and disaster response. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through a series of experiments and performance comparisons with existing approaches to demonstrate its superiority and real-world applicability. Through this study, we aim to contribute to the advancement of high-quality map generation technology and its potential impact across various application domains.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews existing research on image-to-image translation and presents the theoretical background and analysis of the proposed method. Section 3 details the design of the proposed GAN-based network structure and the specific implementation of the loss function. Section 4 validates the performance of the proposed method through various experiments and compares the results with existing methodologies. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a summary of the key findings and discusses future research directions. Through this study, we aim to advance high-quality map generation technology and demonstrate its practical applicability in diverse real-world scenarios.

2. Related Works

Image-to-image translation has been a significant research topic in computer vision, with numerous studies conducted in this area. This domain involves generating a new image by mapping the style of one image onto another [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Multiple research initiatives are underway to transform satellite images into map representations [13,14,15,16] and improve resolution enhancement and related techniques about aerial image [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. By introducing and analyzing research on edge detection, this study underscores the significance of edge preservation [24,25,26].

2.1. Image-to-Image Translation

Pix2Pix [6] is a study based on Conditional GANs, where the generator is trained to transform and generate images using actual images as inputs, rather than random noise. The generator in Pix2Pix [6] adopts a U-Net architecture, effectively preserving detailed structures of the input image, while the discriminator employs a PatchGAN architecture, assessing the realism of each patch within the image. This architecture is particularly well-suited for image-to-image translation tasks and produces more realistic transformation results compared to previous GAN models that generate images from noise. CycleGAN [7] does not require paired image sets, instead learning to translate between two distinct domains. This approach is especially useful in scenarios where paired datasets are difficult to obtain. It incorporates a backward function to restore the translated image back to its original form, thereby maintaining consistency between the original and translated images. Additionally, it introduces a Consistency Loss function to ensure alignment between the generated and original images, allowing for effective cross-domain transformation without paired data.

However, Pix2Pix [6] and CycleGAN [7] face limitations in generating precise, high-resolution maps due to difficulties in capturing detailed information. When generating maps from aerial images, it is essential to preserve key geographical features, including the precise delineation of roads and building edges. Thus, this study introduces a novel approach to overcome these limitations in existing research, addressing critical issues related to detail preservation and noise reduction required for map generation. By doing so, it effectively preserves essential features while eliminating superfluous details, thus enhancing the accurate representation of geographical information.

StarGAN [8] proposes a method for translating images across multiple domains using a single generator, addressing the limitations of fixed-domain translation. StarGAN [8] primarily focuses on translating facial images, which differentiates it from the proposed method in terms of subject matter. However, its ability to perform multi-domain image translation lays a foundational basis for research in image-to-image translation that extends beyond a single domain, offering flexibility for various transformation tasks. CoMoGAN [9] introduces Functional Instance Normalization and Disentanglement of Residual Block structures into the GAN architecture, enabling continuous image translation. The incorporation of residual structures allows for smoother and more natural transitions during complex transformations. In the proposed method, similar residual block structures are utilized to preserve intricate details and reduce noise, which is crucial for generating maps from aerial images.

Wan et al. [10] proposed a Recurrent Transformer Network for the restoration of damaged old film images, converting them back into high-quality photographs. This study achieved significant restoration performance by leveraging hidden information between adjacent frames, thereby ensuring temporal consistency during frame-by-frame restoration. While the subject and objectives differ from the proposed method, both share a focus on image restoration within the broader context of image-to-image translation. The key distinction of the proposed method lies in its focus on preserving critical geographical elements for map generation from independent aerial images rather than utilizing temporal information from adjacent frames. Hourglass Block-GAN [11] employs a U-Net-based hourglass structure to restore highly compressed images back to their original high-resolution state. This study also aims to achieve image-to-image translation through GANs, focusing on recovering lost details. However, while Hourglass Block-GAN concentrates on restoring compressed images, the proposed method focuses on generating maps from aerial images. Similar to the purpose of the hourglass structure in maintaining detailed information, the proposed method leverages residual block structures to ensure the preservation of critical features in map generation.

Thus, while StarGAN [8], CoMoGAN [9], Wan et al. [10], and Hourglass Block-GAN [11] are related to the proposed method under the broader theme of image-to-image translation, their specific goals differ. The proposed method distinguishes itself by advancing beyond traditional image restoration and translation techniques, specifically targeting the generation of detailed and accurate maps, thereby presenting a novel approach that emphasizes detail preservation for geographic information.

2.2. Generation of Aerial Image to Map

SAM-GAN [13] addresses a similar topic as the proposed method, focusing on translating aerial images into maps. SAM-GAN generates translated map images by combining the outputs of an encoder that extracts style information from map images and an encoder that extracts content from aerial images. This approach effectively integrates the stylistic elements unique to maps with the content of aerial images, enhancing cartographic representation. However, due to its reliance on combining content and style features, it may face limitations in preserving fine details and detecting critical boundaries of geographical elements within the translated map images. To overcome these challenges, the proposed method incorporates Residual Blocks and a modified Canny edge detection algorithm, which aim to enhance the preservation of terrain details and boundaries in map generation.

CannyGAN [14], another related study, integrates the Canny edge detector within the GAN architecture, sharing significant commonalities with the proposed method. It uses a disentangled structure to separate content and style domains, enabling effective edge detection within thermal images, which are characterized by heat distribution rather than standard visual features. By separating content and style, it is able to emphasize edges more distinctly. However, the additional step of disentangling content and style introduces complexity that may hinder detail preservation and high-resolution image translation. In contrast, the proposed method modifies the Canny edge detection algorithm to utilize convolutional operations, incorporating it directly as a loss function. This approach avoids the need for complex disentanglement processes while efficiently enhancing major geographical boundaries within aerial images. By using edge detection in the loss function, the proposed method optimizes map generation, focusing on detail preservation.

Thus, while SAM-GAN [13] and CannyGAN [14] share the same goal of image-to-image translation for map generation, both approaches exhibit limitations in achieving precise translation results. The proposed method addresses these limitations by leveraging residual structures and edge detection to ensure more accurate representation of critical geographical features and boundaries within the generated maps, offering a distinct and refined approach to map generation. Although it is not available as open-source, preventing direct experimentation, it can be emphasized that this topic is highly significant within the related field.

Ying et al. [15] proposed a map generation approach that utilizes both a discriminative module and a creative module to preserve geographical information and detailed features in aerial imagery. In this approach, the discriminative module classifies semantic information for each pixel in the aerial image to extract accurate geospatial data, leveraging DeepLabv3+ to enhance semantic segmentation performance for high-resolution map generation. Following this, the creative module employs a conditional GAN (cGAN) to transform semantic information into a map style, using a U-Net-based generator architecture to improve visual quality. This module comprises both a global and a local generator, enabling balanced representation of overall structure and fine details. Additionally, a multi-scale discriminator is applied to optimize the visual quality of generated maps across various resolutions. While this paper adopts a similar approach to Fu et al. [15] in preserving geographic details when transforming aerial imagery into maps, it distinguishes itself by incorporating the Canny edge detector as a loss function to more precisely retain boundary information. Although this approach effectively enhances semantic information and visual quality, it lacks a dedicated edge preservation method, potentially resulting in blurred or undefined geographical boundaries. In contrast, this study reinforces boundary information using edge detection, maintaining distinct geospatial elements while minimizing structural complexity, thus proposing a more efficient map generation process.

SMAPGAN [16] utilizes two GANs to generate styled map tiles from remote sensing images and, conversely, to generate remote sensing images from map tiles. A key feature is its use of a semi-supervised learning strategy that leverages both paired and unpaired data. To achieve this, it divides its training into an unsupervised pretraining stage and a supervised fine-tuning stage, where initial weights are learned from unpaired data, followed by detailed refinement using paired data. In particular, it introduces a topological consistency loss function to preserve the spatial relationships between objects during map generation. The method proposed in this paper shares SMAPGAN [16]’s objective of preserving accurate spatial relationships between objects during the map generation process but differs significantly in its approach. Whereas SMAPGAN [16] focuses on enhancing structural relationships through topological consistency loss, this study integrates the Canny edge detector into the loss function to emphasize the preservation of key boundary information. This approach allows the proposed method to more effectively retain the edges and spatial positions of geographical features, ensuring high fidelity in the representation of object boundaries and topographical elements.

2.3. Research Across Various Fields Related to Aerial Image

Li et al. [17] proposed a model for detecting multiple targets in UAV aerial images, enhancing the YOLOv8-s model’s ‘neck’ section with a Bi-PAN-FPN structure to reduce the misdetection and false detection of small objects. This structure enhances the accuracy of detecting small objects in aerial images, focusing specifically on object detection in UAV imagery. In contrast, our research is centered on accurately representing geographic information for the purpose of map generation. DiffusionSat [18] enhances existing diffusion models to generate realistic remote sensing data, utilizing large-scale public satellite image datasets and metadata, such as geographic location, to create realistic satellite images. This model supports various generative tasks, including multi-spectral super-resolution, temporal generation, and in-painting. Although our research also focuses on image generation, it is distinguished by its emphasis on map generation rather than aerial image generation, setting our approach apart from DiffusionSat [18].

D2ANet [19] introduces a dual-temporal satellite imagery approach for detecting building locations and enabling multi-level change detection, focusing on feature channel differences between pre- and post-disaster images and activating change-sensitive channels to learn global change patterns. While this approach is beneficial for detecting terrain changes in map generation, our study focuses on generating maps from single-timepoint images, providing precise boundary and geographical element representation. He et al. [20] proposed a framework combining spatial geometric feature data with aerial images to estimate building features and generate visually reliable building outlines. This method uses a deep network configuration involving generative modeling, segmentation, and adversarial learning to compensate for degraded aerial image quality. Though our study also employs a generative model, it emphasizes preserving geographic boundaries for map generation and uniquely integrates edge detail preservation as a loss function based on Canny edge detection.

Mall et al. [21] proposed a method for learning effective representations from unlabeled satellite image data using self-supervised learning, introducing a new loss function and a sampling method across diverse geographical regions to enhance semantic segmentation and change detection. While our research shares the objective of achieving high performance, our method is specialized for preserving boundaries and details critical for map generation. Ma et al. [22] presented a cloud removal method for satellite images. This model utilizes a convolutional neural network to extract cloud transparency information and restore surface details in thin cloud regions. While our research does not address cloud removal, it shares the objective of enhancing terrain detail preservation to improve map generation accuracy. Xu et al. [23] introduced P2Cnet, a model for extracting roads from aerial images and partial road maps, filtering out irrelevant information and focusing on absent road pixels. Although our research also emphasizes boundary detection and map generation, it offers a more comprehensive approach by generating detailed maps that encompass multiple geographical elements beyond roads alone.

In summary, previous research [17,18,19,20,21,22,23] provides various approaches to achieve specific objectives within satellite and aerial image analysis. However, our study contributes a unique approach focusing on map generation through detail preservation and boundary accuracy, delivering comprehensive geographic information.

2.4. Edge Detection

Edge detection is a fundamental task in computer vision, focused on identifying boundaries or transitions between regions in an image to extract structural information. However, accurately preserving edge details while detecting them remains a significant challenge. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted to develop advanced methodologies that address this issue.

Elharrouss et al. [24] presented a refined edge detection approach using a cascaded and high-resolution network to tackle challenges in detecting precise edges in complex scenes. The method emphasizes maintaining edge resolution throughout the network stages and refines edges using batch normalization layers as erosion operations. The method proposed in this paper focuses on preserving and enhancing edge information using the Canny edge detector, whereas the research by Elharrouss et al. [24] differentiates itself by employing a deep learning model that leverages advanced computational techniques in the field of image processing for edge detection.

Jin et al. [25] proposed a network based on edge detection to enhance the semantic segmentation performance of remote sensing images. This method utilizes an edge detection guide module to effectively combine detailed and semantic information between high-level and low-level features, enabling data fusion centered on boundary information. However, unlike the method proposed in this paper, their research emphasizes the design of a deep learning network specifically for edge detection as its primary objective, with semantic segmentation as a supporting task. To achieve this, the network is trained using paired data with edge ground truth, enhancing the accuracy of edge detection and maximizing semantic segmentation performance.

Chen et al. [26] proposed a Multi-scale Patch Generative Adversarial Network (MPGE) based on edge detection to enhance image inpainting performance. The MPGE integrates an edge detector into the generator to refine edge contours in reconstructed images and combines L2 loss with a patch-GAN to maintain high resolution and stylistic consistency. Additionally, a multi-head attention mechanism is employed to improve global consistency in the inpainting process. The similarity between this study and MPGE lies in utilizing edge information as a loss function. However, while this paper employs the Canny edge detector to preserve edge details, MPGE leverages a custom-designed network to effectively incorporate edge information, highlighting the methodological distinction.

3. Map Generation from Aerial Image

This paper proposes a method for converting aerial images into high-quality maps. The core of this transformation process is to focus on key features such as roads and buildings in the aerial imagery while excluding extraneous elements not represented on the map. For instance, roads must be color-coded based on their type (e.g., regular roads, highways). Additionally, only the edges of buildings are marked, with the interior areas of buildings represented in a single color. The paper introduces a GAN-based generative network for image-to-image translation to achieve this.

The proposed system comprises two main modules: a generator and a discriminator. The generator aims to generate indistinguishable images from real ones, while the discriminator’s objective is to classify the provided images as real or fake accurately. However, existing image-to-image translation studies often encounter errors in accurately converting authentic aerial images to maps, with unnecessary details lowering the quality of the images. To address these issues, the proposed method incorporates Residual Blocks into each layer of the generator’s architecture to better preserve critical features.

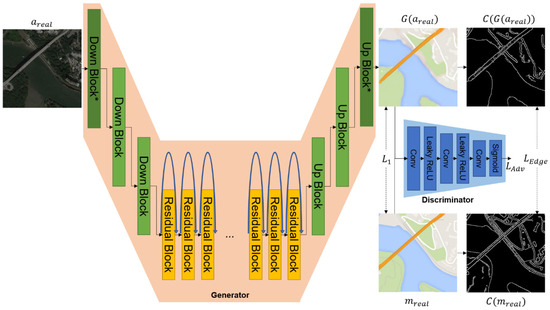

Additionally, the method applies computational operations commonly used in image processing as loss functions to enhance the quality of the generated maps. Specifically, the difference between the Canny edge detection results is used as a loss function to process the edges of roads and buildings and remove unnecessary interior details. This approach is illustrated in the process described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overall process of the proposed method.

The generator takes aerial image as input and generates fake map images that closely resemble real maps. The generator mainly comprises three types of blocks: Down Block, Up Block, and Residual Block.

Down Block is designed to increase the depth of the feature maps while decreasing the width and height dimensions. This block includes zero padding, convolution, normalization, and the ReLU activation function. After passing through a Down Block, the height and width of the feature map are halved and the channel depth is doubled.

In contrast with the aforementioned Down Block, the Down Block* is the most proximal to the input. The kernel size is 7, the stride is 1, and replicate padding is employed to compute the feature map. In contrast, the Up Block performs operations that are opposite to those of the Down Block, with the objective of restoring the image size. In comparison to the conventional convolution operation, transpose convolution results in a reduction of the channel depth while simultaneously doubling the height and width. The Up Block* incorporates replicate padding prior to the transpose convolution and replaces the activation function with Tanh. The application of zero padding serves to streamline the calculations and mitigate the risk of overfitting. However, this may result in the loss of edge information. Consequently, the design employs zero padding in certain blocks, while replication padding is utilized for sections proximate to the input and within the Residual Blocks.

The generator’s Residual Block consists of a sequence of convolution, normalization, ReLU activation, convolution, and normalization. In this block, replicate padding is used during convolution to maintain the same feature map size with a fixed kernel size of 3. The generator performs this Residual Block N times across four layers. After executing each block, the output is added to the previous layer’s output and passed through the ReLU activation function.

The discriminator includes three convolutional layers, with output channel depths set to 64, 128, and 1, respectively. A Leaky ReLU activation function follows each convolution operation, and after the final convolution, a Sigmoid function adjusts the output values between 0 and 1. Table 1 describes the detailed specifications of the proposed network.

Table 1.

Architectures of the network of generator and discriminator. The blocks marked with an asterisk (*) have the same structure as the existing Down and Up blocks, but with minor differences in stride, kernel size, and padding.

Although the Residual Block helps preserve the features of aerial photographs, this paper employs the Canny edge detector to ensure the edges in the real map photos are considered during training. The Canny edge detector identifies edges in images through the following process. First, a 5 × 5 Gaussian filter is used for smoothing to remove noise. Then, a 3 × 3 Sobel operator calculates the brightness gradient in the x and y directions. These gradients indicate the direction of the most significant brightness change and are perpendicular to the edges. Non-Maximum Suppression is then applied to retain only the maximum values, leaving precise edges. Finally, Hysteresis Thresholding is conducted. The thresholding uses two thresholds to distinguish strong edges from weak edges; strong edges that exceed the high threshold are considered definite edges.

In contrast, weak edges between the low and high thresholds are only considered to be edges if they are connected to strong edges. The overall process of Canny edge detection remains unchanged; however, it can be observed that Non-Maximum Suppression has been streamlined through the utilization of convolution operations. The initial stage of the process involves applying a two-dimensional max pooling operation to each pixel in the magnitude matrix. This operation utilizes a 3 × 3 kernel, a stride of 1, and a padding of 1, with the objective of identifying the maximum value present within each 3 × 3 neighborhood. Subsequently, a Boolean mask is generated, wherein each element is set to True if it represents a local maximum within its 3 × 3 neighborhood. Only the local maximum values are retained within the matrix through the utilization of this Boolean mask. Ultimately, the function returns the suppressed magnitude matrix.

This paper uses the difference between and , computed by the Canny edge detector, as a loss function to minimize, aiming to generate accurate and high-quality map images. The optimal parameters for the two thresholds are determined through exploration in the paper. Unlike the traditional Non-Maximum Suppression process, this approach compares the original and convolution-processed images to retain only the parts of the original image with matching values.

The loss function for training the proposed GAN network is defined as follows. First, the Adversarial Loss functions for the generator and discriminator are defined in Equations (1) and (2). The discriminator aims to classify as real and as fake. Therefore, if all samples are correctly classified, Equation (1) evaluates to zero. However, Equation (2) works oppositely, where the generator aims to deceive the discriminator by classifying as real. It requires to be similar to and generate realistic images.

Additional loss functions are introduced in Equations (3) and (4) to generate images similar to the target . Equation (3) serves as the primary loss function in image-to-image translation, ensuring the overall distribution (e.g., color and general structure) is similar. It minimizes the difference between images, facilitating the transformation of aerial images into map images. However, relying solely on the L1 Loss makes it challenging to generate fine details, as it focuses on the overall distribution. Detailed features, such as the shape of roads and the location of buildings, might need to be addressed. Thus, this paper incorporates edge detection to preserve these details, as represented in Equation (4). The goal is to make and similar by applying the Canny edge detector. Therefore, minimizing requires to generate these detailed features.

Equation (5) gives the overall loss function used for training in this paper, where and are c images.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets and Environments

The Maps dataset [27] used in this paper is constructed using aerial image and map tiles from Google Maps, each with a resolution of 600 × 600 pixels. As shown in Table 2, the dataset is divided for training and testing, consisting of 4384 images set at a 1:1 ratio. The dataset includes aerial and map images in and around New York City. This dataset provides diverse scenarios applicable to image-to-image translation research, allowing the model to train and evaluate the visual style of maps during training. It is based on the publicly available dataset from the Pix2Pix [6] project. The dataset images were resized from the original 600 × 600 resolution to 256 × 256 using OpenCV functionality.

Table 2.

Detailed information of datasets.

All experiments are conducted on an Ubuntu 18.04 LTS operating system. An NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics card with 24 GB of memory is utilized for training and inference. The programming is based on Python version 3.9 and the model implementation employs PyTorch framework version 1.10.1. Training is performed over 100 epochs, with an initial learning rate 0.0002. The learning rate is maintained for the first 50 epochs and then linearly decreases to zero over the remaining epochs until epoch 100. This approach gradually optimizes the model’s performance. The Adam optimizer is selected with = 0.9 and = 0.999. Given the batch size of 1, the training is effectively done using Stochastic Gradient Descent. The model’s input and output image sizes are set to 256 × 256 pixels. In the loss function, the hyperparameters are set as = 0.5, = 10, and = 100. For the Canny edge detection, weak edges are set at 10% of the maximum pixel value (255), and strong edges are set at 30%.

4.2. Performance Analysis and Comparisons

We analyze and discuss the performance variation of the model based on the number of Residual Block repetitions, denoted as N. Table 3 presents the performance results from the experiments. Performance is assessed using the metrics PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS [28], an upward arrow indicates that higher values represent better performance, while a downward arrow signifies that lower values correspond to better performance. PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (Structural Similarity Index) are objective image quality measures, with higher values indicating more remarkable similarity to the original image. LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity) measures the similarity between images by comparing feature maps extracted using a VGG network, where lower values indicate higher similarity.

Table 3.

Experimental results based on the number of residual block repetition (N).

When N is equal to 15, the PSNR value is 30.735, which is indicative of optimal performance. An examination of the PSNR values from N = 9 to N = 17 reveals that an increase in the number of Residual Block repetitions does not necessarily result in enhanced performance. It is, therefore, imperative to select an appropriate value for N. SSIM is a metric that evaluates the structural similarity of images, and similarly, higher values indicate better performance. The SSIM value is highest at 0.806 when N is 15, indicating that the structural similarity of the image is best preserved with this number of Residual Block repetitions. LPIPS measures the learned perceptual image patch similarity; lower values indicate better performance. The LPIPS value is lowest at 0.304 when N is 15, indicating the best perceptual quality of the image.

A comprehensive analysis of the experimental results shows that the model achieves optimal performance in terms of PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS when the number of Residual Block repetitions, N, is 15. It demonstrates that increasing the number of Residual Block repetitions enhances the model’s performance up to a certain point, but further increases can lead to diminishing returns or even performance degradation.

Therefore, selecting an optimal number of Residual Block repetitions is crucial for maximizing the model’s performance. This study found that N = 15 provides the optimal performance, indicating that this number of repetitions best preserves the information from the aerial images while generating map images from aerial images.

Table 4 presents the results of evaluating and comparing the performance of various models for generating maps from aerial images using GAN-based techniques. In the experiments, the performance of the proposed model is analyzed in comparison with the existing Pix2Pix [6], CycleGAN [7], and SMAPGAN [16]. The proposed model is evaluated under different configurations, including using Residual Blocks and applying .

Table 4.

Evaluations and comparisons of performance.

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model, which integrates Residual Blocks and , achieves the highest values in PSNR and SSIM. This suggests that the quality of the generated map images is improved compared to other models. Specifically, the proposed method records a PSNR of 30.735, an SSIM of 0.806, and an LPIPS of 0.304, indicating superior performance across these evaluation metrics. Analysis of the results shows a significant improvement in model performance with the application of Residual Blocks, highlighting their role in preserving image features. Although performance improvement is also observed using , it is not as pronounced. This is likely because Canny edge detection emphasizes structural features (edges), potentially causing variations in overall color distribution.

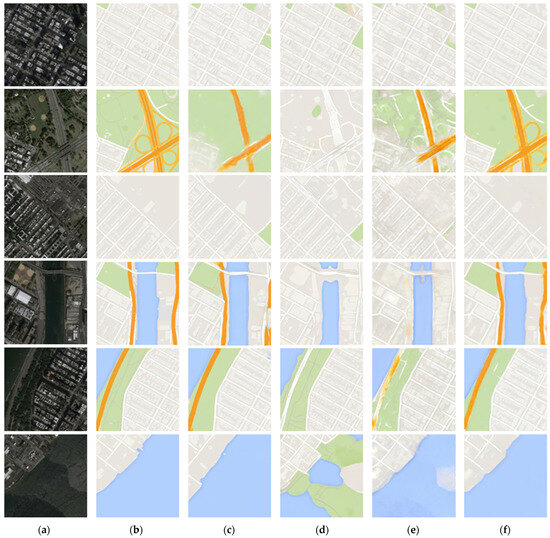

In all model configurations, the LPIPS value is low, indicating that the proposed model generates map images most similar to the original. Figure 2 illustrates map images generated by related studies and the proposed +method, corresponding to and . Pix2Pix [6] exhibits a poor representation of highways, while CycleGAN [7] focuses excessively on constructing roads, resulting in significant differences from . The proposed method closely approximates the original image in more straightforward scenarios, as shown in the first row of Figure 2. However, in the more complex situations depicted in the second row of Figure 2, although the proposed method performs better than those in related studies, its ability to accurately represent the map is relatively lower. In the third row, the results of Pix2Pix [6] and the proposed method show no significant differences.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of generation results between the proposed method and related works ((a): original aerial image, (b): original map image, (c): Pix2Pix [6], (d): CycleGAN [7], (e): SMAPGAN [16], and (f): our research).

However, in the fourth row, the proposed method demonstrates superior performance in generating the orange roads. In contrast, CycleGAN [7] fails to account for the green and orange areas. For the fifth row, while the color differences between Pix2Pix [6] and the proposed method are minimal, the proposed method exhibits sharper building generation capabilities. Lastly, the results in the sixth row include an area with water. Here, CycleGAN [7] generates land, resulting in entirely different results. When comparing Pix2Pix [4] and the proposed method, the proposed method performs better in generating white roads. SMAPGAN [16] focuses primarily on preserving detailed features. While the generated results for buildings are similar to the ground truth, discrepancies are observed in terms of color and roads. In some cases, roads are generated in areas where they do not exist, or highways are omitted, leading to incorrect outputs. Therefore, apart from building generation, SMAPGAN [16] demonstrates suboptimal performance, as evidenced by the quantitative evaluation in Table 4, which shows low performance metrics. Through the results presented in Figure 2, we can directly compare the results of the proposed method with those of related studies on map transformation. This comparison demonstrates that the proposed method exhibits superior performance.

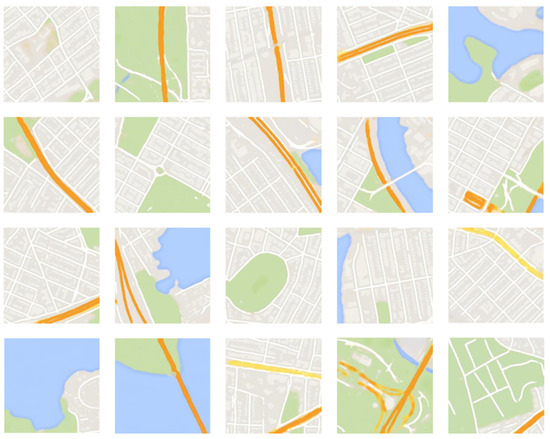

Figure 3 illustrates the map images generated using the proposed method. When compared with conventional approaches, the proposed method demonstrates superior performance in generating maps. Elements like houses, forests, roads, and oceans are depicted with greater clarity. However, in some instances, blurred edges or disconnected roads can be observed. This phenomenon occurs due to the inherent limitations of the original aerial imagery, where edge details are not well represented, such as areas obscured by trees. As a result, the model must infer the boundaries on its own in the absence of clear edge features, leading to these occasional artifacts. These artifacts highlight the limitations of aerial imagery as a data source, especially in situations where feature representation is constrained. Despite these challenges, the proposed method successfully generates map images that closely resemble the real-world environment, demonstrating its robustness and effectiveness in handling such scenarios.

Figure 3.

Examples of map images generated using the proposed method.

5. Discussion

The proposed method in this study aims to generate maps from aerial imagery by preserving high accuracy and detailed geographic information, suggesting practical applications across various scientific fields. By examining the key characteristics of this approach and its potential applications, we can explore how this research may contribute not only to map generation but also to other diverse areas.

The proposed method combines Residual Blocks and Canny edge detection to maximize detail preservation during map generation. Residual Blocks effectively retain essential geographic information at each layer, while the Canny edge detection is applied as a loss function to emphasize detailed features, such as primary terrain boundaries. These features enable the model to excel in generating maps of complex terrains, achieving more precise boundary representation compared to conventional map generation models [6,7,16] which often struggle with such detail.

This method demonstrates substantial potential for applications in geology. Geological mapping plays a crucial role in analyzing structures such as faults, folds, and stratigraphic layers, which are essential for understanding the characteristics and formation processes of specific regions. The proposed approach significantly enhances the generation of high-resolution maps, enabling precise identification of key geological features, including fault lines, layer boundaries, and structural deformations. The method’s adaptability to aerial imagery and 3D models further improves the development of detailed Digital Elevation Models (DEMs). For instance, applying these methods to studies like those of Bello et al. [29], UAV imagery captured after catastrophic events such as earthquakes could greatly enhance coseismic fracture mapping, providing higher spatial resolution and detail. Similarly, in monitoring vertical rock faces or identifying fractures and joints within rock masses as in Cirillo et al. [30], our approach could further refine image quality, improving results and aiding in landslide and rockfall risk mitigation. Furthermore, the method extends its applications to environmental monitoring, providing valuable tools for tracking natural changes. By enhancing the extraction of precise, detailed data, the proposed approach adds an additional layer of analysis that can improve risk mitigation strategies, significantly reducing the impact of geological hazards and other environmental challenges. The proposed method’s strength in detail preservation and accurate terrain boundary representation makes it a versatile tool with potential applications not only in mapping but also in broader fields where high-resolution and precise geographic data are critical.

6. Conclusions

This study introduced a GAN-based method for generating high-quality maps from aerial imagery. The proposed model effectively incorporates Residual Blocks to reduce noise while preserving essential structural features and employs a Canny edge detection-based loss function to enhance edge preservation during the map generation process. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed method outperforms traditional approaches, generating maps with clear representations of houses, forests, roads, and coastlines. However, several limitations were identified in this study. The model struggled with accurately generating maps in complex terrains, such as mountainous regions and dense road networks. These issues stem from the limitations inherent in aerial imagery, where certain areas, such as roads, may be occluded by trees or other obstacles, resulting in incomplete or blurred edge information. In such cases, the GAN model is forced to infer the boundaries, leading to occasional artifacts like discontinuous roads or blurred edges.

To address these limitations, future work should incorporate a more diverse set of aerial images captured under different environmental conditions. The current dataset primarily consists of images captured under specific weather conditions and during certain times of the year. Incorporating data captured during different seasons and under various climatic conditions would allow the model to generalize better. For instance, roads may be obscured by snow in winter, while dense foliage may obstruct visibility in summer. By including such diverse data, the model can be trained to handle a wider range of scenarios and produce more robust and generalized map outputs. Moreover, additional techniques are required to handle the accurate generation of maps in challenging terrains, such as mountainous regions and dense urban road networks. One potential approach is to incorporate multi-resolution aerial imagery, which would provide higher detail for specific regions, or to integrate 3D terrain data with aerial imagery. The use of 3D terrain data, which includes information on elevation and surface contours, can provide additional context to the GAN model, enabling it to generate more accurate representations of complex geographies, especially in regions where elevation changes are significant.

In addition, the map generation process can be further refined by adopting task-specific training strategies. For instance, if the goal is to generate maps for transportation network design, priority should be placed on accurately preserving road connectivity and boundaries. In such cases, the use of specialized loss functions that emphasize road networks or incorporating a road recognition module could improve performance. On the other hand, maps intended for environmental conservation efforts may require more accurate representations of forests, rivers, and other natural features, necessitating a different approach to feature extraction and training.

In conclusion, the proposed GAN-based method successfully generated high-quality maps from aerial imagery, demonstrating superior performance in noise reduction and structural feature preservation compared to existing methods. However, to further enhance the model’s capability, future research should focus on expanding the dataset to include aerial images captured under diverse environmental conditions, as well as integrating additional data sources, such as 3D terrain information, to improve the model’s performance in complex terrains. Task-specific optimization techniques should also be explored to tailor the map generation process to different application domains, such as transportation planning or environmental monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and S.K.; methodology, J.S.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S.; formal analysis, J.S. and S.K.; investigation, J.S.; resources, S.K.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, J.S. and S.K.; project administration, S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology development Program (S3344882) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Map datasets at http://efrosgans.eecs.berkeley.edu/pix2pix/datasets/maps.tar.gz, accessed on 27 September 2024, reference number [27].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Research Council; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Earth Sciences and Resources; Mapping Science Committee; Infrastructure Committee on Planning for Catastrophe: A Blueprint for Improving Geospatial Data, Tools. Successful Response Starts with a Map: Improving Geospatial Support for Disaster Management; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani, S.M.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Urban Resilience Enabled with Asset and Disaster Risk Management Approaches and GIS-Based Decision Support Tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, D.; Cerritelli, F.; Agostini, S.; Bello, S.; Lavecchia, G.; Brozzetti, F. Integrating Post-Processing Kinematic (PPK)–Structure-from-Motion (SfM) with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Photogrammetry and Digital Field Mapping for Structural Geological Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Remote Sensing Applications—A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carricondo, P.; Agüera-Vega, F.; Carvajal-Ramírez, F.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J.; García-Ferrer, A.; Pérez-Porras, F.-J. Assessment of UAV-photogrammetric mapping accuracy based on variation of ground control points. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isolaa, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-image Translation using Cycle-consistent Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Choi, M.; Kim, M.; Ha, J.W.; Kim, S.; Choo, J. StarGAN: Unified Generative Adversarial Networks for Multi-domain Image-to-image Translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8789–8797. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzati, F.; Cerri, P.; De Charette, R. CoMoGAN: Continuous Model-guided Image-to-image Translation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14288–14298. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; Liao, J. Bringing Old Films Back to Life. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2022), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–20 June 2022; pp. 17694–17703. [Google Scholar]

- Si, J.; Kim, S. Restoration of the JPEG Maximum Lossy Compressed Face Images with Hourglass Block-GAN. CMC—Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 78, 2893–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; Cao, J.N. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Challenges, Solutions, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Han, C.; Dong, B.; Li, H. SAM-GAN: Supervised Learning-based Aerial Image-to-map Translation via Generative Adversarial Networks. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, T.; Liu, L.; Wiliem, A.; Lovell, B. CannyGAN: Edge-preserving Image Translation with Disentangled Features. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liang, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, Z. Translation of aerial image into digital map via discriminative segmentation and creative generation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote 2021, 60, 4703715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, T.; Yin, B.; Peng, J.; Mei, X.; Li, H. SMAPGAN: Generative adversarial network-based semisupervised styled map tile generation method. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote 2020, 59, 4388–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, Q.; Huang, H.; Han, Z.; Gu, Q. A modified YOLOv8 detection network for UAV aerial image recognition. Drones 2023, 7, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; Meng, C.; Rombach, R.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.B.; Ermon, S. Diffusionsat: A generative foundation model for satellite imagery. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, J.; Zheng, Y.B.; Cheng, M.M. D2ANet: Difference-aware attention network for multi-level change detection from satellite imagery. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Shan, J.; Aliaga, D. Generative building feature estimation from satellite images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote 2023, 61, 4700613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, U.; Hariharan, B.; Bala, K. Change-aware sampling and contrastive learning for satellite images. In Proceedings of the 0023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 5261–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wu, R.; Xiao, D.; Sui, B. Cloud Removal from Satellite Images Using a Deep Learning Model with the Cloud-Matting Method. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.X.; Long, C.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C. Road Extraction With Satellite Images and Partial Road Maps. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote 2023, 61, 4501214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharrouss, O.; Hmamouche, Y.; Idrissi, A.K.; El Khamlichi, B.; El Fallah-Seghrouchni, A. Refined edge detection with cascaded and high-resolution convolutional network. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 138, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhou, W.; Yang, R.; Ye, L.; Yu, L. Edge detection guide network for semantic segmentation of remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote 2023, 20, 5000505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Liu, W. Multi-scale patch-GAN with edge detection for image inpainting. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 3917–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Map Datasets. Available online: http://efrosgans.eecs.berkeley.edu/pix2pix/datasets/maps.tar.gz (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, S.; Andrenacci, C.; Cirillo, D.; Scott, C.P.; Brozzetti, F.; Arrowsmith, J.R.; Lavecchia, G. High-Detail Fault Segmentation: Deep Insight into the Anatomy of the 1983 Borah Peak Earthquake Rupture Zone (Mw 6.9, Idaho, USA). Lithosphere 2022, 1, 8100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, D.; Zappa, M.; Tangari, A.C.; Brozzetti, F.; Ietto, F. Rockfall Analysis from UAV-Based Photogrammetry and 3D Models of a Cliff Area. Drones 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).