Abstract

Placentae and their derivatives have been used in both traditional and modern medicine, as well as in cosmetic sciences. Although hair loss is frequently mentioned among problems for which the placenta is supposed to be a remedy, the evidence seems rather scarce. The aim of this study was to highlight the clinical evidence for the efficacy of placenta products against baldness and hair loss. Methods: This systematic review was performed according to PRISMA and PICO guidelines. Database searches were conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus. Results: Among the 2922 articles retrieved by the query, only 3 previously published clinical trials on placental products were identified. One study was a randomized controlled trial, in which the efficacy of a bovine placenta hair tonic was found to be comparable to that of minoxidil 2% in women with androgenic alopecia. Another controlled study showed that a porcine placenta extract significantly accelerated the regrowth of shaved hair in healthy people. The third study was an uncontrolled trial of a hair shampoo and tonic containing equine placental growth factor in women with postpartum telogen effluvium with unclear and difficult-to-interpret results. Due to the design and methodology of these studies, the level of evidence as assessed with the GRADE method was low for the first study and very low for the other two. Conclusions: The very limited scientific evidence available to date appears, overall, to indicate the efficacy of placental products in both inhibiting hair loss and stimulating hair growth. Unfortunately, the number of clinical studies published to date is very limited. Further, carefully designed, randomized controlled trials of well-defined placental products are needed to definitively address the question of the value of the placenta and its derivatives in hair loss.

Keywords:

placenta; placental protein; hair loss; alopecia; effluvium; baldness; clinical trials; systematic review 1. Introduction

The placenta is arguably the least understood organ, perhaps due to its transitional nature [1,2]. Despite its short lifespan, lasting 9 months of pregnancy, it performs functions typically carried out by various organs, including the lungs, liver, intestines, kidneys, and endocrine glands [3,4,5]. The variety of morphological forms of the placenta throughout mammals makes it hard to define by a list of common features [6]. Harland Mossman stated that “the normal mammalian placenta is the apposition or fusion of the fetal membranes with the uterine mucosa for physiological exchange” [7]. The medicinal uses of the placenta date as far back as 2500 years ago. It has been used as an elixir of eternal youth and longevity, and is also valued as a remedy for physical and mental fatigue and weakness [8]. Traditional Chinese medicine experts believed that the placenta contains a “life force” and used it for boosting lactation, blood circulation, and immunity, as well as for lethargy, skin aging and hair loss [9]. Vladimir Petrovitch Filatov (1885–1956) believed that any tissue of human or animal origin could be used for therapeutic purposes, even if histologically different from the diseased tissue—a concept he called the “therapeutic tissue principle” [10]. Although placental extracts have been popular for over a century in Europe and parts of Asia (mainly China, Korea and Japan), there was no scientific evidence of their effectiveness until recently [10].

Nowadays, the placenta is known to be rich in bioactive molecules used as regenerative and anti-aging agents with significant therapeutic properties [11,12,13]. The composition of placenta extracts, and thus their biological effects depend on the method of preparation [14]. The manufacture of biological products for direct use in humans requires full compliance with the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), at all stages of production, starting from the retrieval of the raw material of which the active ingredients are made [15]. This review focuses on the use of two forms of placenta derivatives, namely placental proteins and protein hydrolysates. Placental protein extract is a mixture of proteins derived from animal placentae, whereas hydrolyzed placental proteins are produced by digesting placental proteins with acidic, enzymatic, or other hydrolysis methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cosmetics ingredients database (CosIng) characteristics of placental protein and hydrolyzed placental protein [16].

The strongest biostimulating effects are ascribed to aqueous extracts of fresh, full-term human placenta [19]. The human placenta fulfills a variety of functions, therefore, it contains a range of biologically active compounds, most of which are proteins that act as hormones, enzymes, proenzymes, activators, inhibitors, immunoregulatory factors, transport and storage proteins, receptors or structural proteins [20]. Examples of placenta-specific hormones are human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and human placental lactogen (hPL), placental enzymes include heat-stable alkaline phosphatase (HSAP), diamine oxidase (DAO) and oxytocinases, e.g., insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP) or leucyl and cystinyl aminopeptidase (LNPEP) [20]. Placenta extracts contain abundant amounts of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factors (IGF), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) [21]. VEGF and IGF-1 from the umbilical cord protein extract can accelerate the proliferation of hair follicle (HF) and interfollicular cells [19]. The nutritional value of the human placenta is due to its abundance of proteins, including the iron storage protein ferritin and structural proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, as well as amino acids, minerals, fats, and vitamins [9,20]. According to the EU and US law, placental extracts cannot be considered cosmetic ingredients due to the presence of hormones [22]. In the EU, ingredients of human origin must not be used in cosmetics as stipulated in the Cosmetics Regulation no. 1223/2009/entry 419/Annex II due to concerns about the transmission of human diseases [17]. The use of umbilical cord extract is unrestricted in Japan, with most of its ingredients described as hair-conditioning or skin-conditioning agents [22]. In Malaysia, the placenta is not listed among prohibited ingredients in the Guidelines for Control of Cosmetic Products by the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency and the Ministry of Health. However, the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM) refused to issue halal certificates for placenta derivatives [23]. Table 2 provides an overview of the biologically active components of the placenta.

Table 2.

Overview of biologically active substances in placenta ([24,25,26,27,28,29,30], further sources cited in the table).

The original life-supporting and growth-stimulating functions of the placenta, combined with the multidirectional biological effects of its numerous components appeal to the imagination of consumers which, in turn, stimulates the industry’s interest in developing therapeutic and cosmetic products based on the placenta [76]. In a recent study of trichological shampoos (i.e., specialist shampoos against hair loss of foreign or domestic brands) available on the Polish market, 7.7% of the products contained placental protein or hydrolyzed placental protein on the declared list of ingredients, putting it in rank 5 of active ingredients added most frequently [77]. On the other hand, concerns about the safety of exposure to materials of human or animal origin have led to legal restrictions in many countries [78].

In an attempt to enrich this discussion with an evidence-based assessment of the possible benefits of placenta derivatives, we have undertaken this systematic review of data from clinical studies in humans on the effectiveness of placental extract, placental protein or hydrolyzed placental protein in hair growth-promoting or hair-loss-reducing products.

2. Methods

The systematic review was performed according to PRISMA and PICO protocols. Databases PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched from January to June 2024, using the query (“placenta” OR “placental protein”) AND (hair OR alopecia OR effluvium OR bald* OR pilo* OR pili). The “all fields” option was active in the query, no additional filters like language or publication date were applied. We included only original articles describing results of clinical trials on placenta, placental proteins and hydrolyzed placental proteins on hair loss or hair growth in humans (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inclusion criteria for the human studies covered in this systematic review.

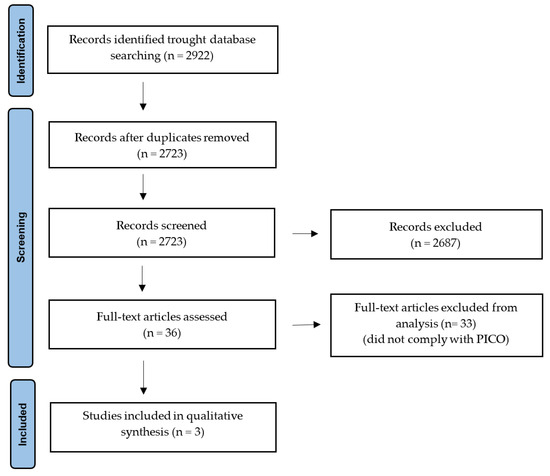

We excluded review articles, as well as studies published only as abstracts, posters, or meeting reports. The GRADE classification was used to assess the quality of evidence for the studies included in this review as either very low, low, moderate, or high [79]. Altogether, 2922 articles were identified, of which 199 duplicates were excluded. Further 2687 articles were excluded after screening of abstracts or full texts. A detailed full-text analysis was performed on 36 articles. Finally, only 3 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A flowchart for PRISMA protocol of data acquisition.

3. Results

The placenta preparations tested in humans were all of animal (bovine, equine, and porcine) origin and were tested in the form of a shampoo, hair tonic or serum [80,81,82]. The formulations tested were a shampoo (one article), a serum (one article), and lotions (two articles). Two preparations (lotion and shampoo) were tested simultaneously in one study. All formulations were intended for direct application to the scalp, including one rinse-off product (shampoo) and three leave-on products (serum, lotion). The total number of people analyzed in all articles was 127, including 115 women (90.5%) with androgenic alopecia (AGA) or postpartum telogen effluvium (TE), and 12 healthy volunteers of undisclosed gender (9.5%). The age of the combined group of participants (n = 127) ranged from 18 to 40 years. The diagnoses serving as inclusion criteria were: androgenetic alopecia (90 patients), postpartum telogen effluvium (25 patients), and healthy participants without any alopecia (12 subjects).

One study was a randomized controlled trial of a cow placenta hair tonic lotion at an undisclosed concentration, with minoxidil 2% as the comparator [80]. The authors concluded that the cow placenta product tested can be as effective as minoxidil in women with AGA [80]. Another site-to-site controlled study demonstrated that porcine placenta extract significantly accelerated the regrowth of shaved hair in healthy people, with a shaved and untreated patch serving as a control [81]. The third study identified was an uncontrolled trial of a hair shampoo and tonic with equine placental growth factor and three other ingredients (pumpkin extract, panthenol, niacinamide) at undisclosed concentrations in women with postpartum TE with ambiguous results which were difficult to interpret [82]. In the last case, the authors expressed their positive impression, although the lack of control, as well as the complex composition of the test product combining placental growth factor (PlGF), pumpkin extract, panthenol, and niacinamide gave us no choice but to put the evidence level mark at “very low”. An overview of the trials is collated in Table 4 and, in more detail, in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials.

Table 4.

An overview of clinical trials on the effectiveness of placenta products in hair loss (see Supplementary Material, Table S1 for more details).

4. Discussion

Hair loss is not a debilitating health issue or a life-threatening condition, nevertheless, it can cause psychological or social problems [83]. Patients with baldness have a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and social phobia as compared to the rest of the population [84]. Worryingly, the number of patients with excessive hair loss and baldness is increasing year by year [85]. Modern lifestyles and habits, stress at work and environmental pollution put a strain on the scalp and hair [86]. Therefore, it is important to make an early diagnosis and initiate treatment as soon as possible. Alopecia is divided into scarring and non-scarring variants. Primary scarring alopecia is caused by autoimmune diseases while secondary scarring alopecia results from burns, trauma or infections. Non-scarring alopecia includes androgenetic alopecia, telogen effluvium and alopecia areata [87]. Hair follicles cycle through anagen, catagen, and telogen phases that form a periodical regenerative cycle of hair growth, shedding, and regrowth, a disruption in this cycle results in hair loss [88]. Hair follicles are located in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue [89]. The most pivotal structure in hair follicles is the dermal papilla, which delivers nutrients and oxygen as well as signals that sustain and orchestrate the hair growth cycle [90]. Normal hair cycle and regeneration depend on signals from the surrounding cellular microenvironment that include hormones, cytokines, and other mediators. Growth factors, like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-5S, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 play a significant role in the regulation of hair cycle and regeneration. Several signaling pathways are involved in this process, including the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [87]. There are various causes for dysregulation of the hair growth cycle in women and men, including aging, hormonal imbalances, nutritional deficiencies, and stress [91].

Disorders of hair growth and hair loss should be promptly diagnosed and treated. To date, the US Food and Drug Administration has approved only two hair-loss drugs: minoxidil—a potassium channel opener, and finasteride—a blocker of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) synthesis [92]. Pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies are looking for new ingredients to stop excessive hair loss and restore a normal hair cycle. Among the ingredients in the spotlight are placental proteins and their hydrolysates. As a complex organ with multiple functions, the placenta contains a multitude of substances with a broad range of biological effects and possible applications. Various functions are ascribed to placenta derivatives, including moisturizing, soothing, anti-aging or, more broadly, conditioning effects on the skin, hair or scalp [93]. At present, ingredients of animal origin are used less frequently for various reasons, including the risk of infectious contaminations, and legal restrictions, but also to ethical issues and concerns about animal welfare and the protection of biodiversity [94,95]. The use of animal by-products in the cosmetics industry is only permitted if they meet the requirements of purity, safety and hygiene [95]. For safety reasons, they often are replaced with similar plant or synthetic substances. In addition, consumers often pay attention to certifications of products as vegan or cruelty-free [96,97]. A range of animal ingredients that were used in cosmetics in the past are abandoned now because modern research has failed to demonstrate their effectiveness or found unacceptable risks to consumers’ health [98]. The FDA recommends that placenta-derived ingredients which for safety reasons are depleted of hormones and other biologically active substances should not be identified as “placenta extract” because it may be misleading to consumers who associate the name with certain biological activities [22]. In Singapore, the human placenta is readily available from China in a dried form and broadly used to treat baldness. In addition to restoring hair growth, human placenta extract was found to be effective in reducing wrinkles and strengthening the immune response [9]. Injections of placenta extract have been used with some success in women with hair loss and other cosmetic applications [99]. Human placenta extract was also shown to induce hair regrowth after chemotherapy-induced alopecia, possibly due to inhibition of apoptosis and stimulation of proliferation in hair follicles [100]. An ex vivo study in human scalp samples sourced from facelift surgery demonstrated the ability of human placenta extracellular matrix (HPECM) hydrogel to regenerate hair follicles and induce hair growth [101].

The overall impression from the present systematic review is that very limited clinical evidence is available to date for the effectiveness of placenta products against hair loss in humans. In the entire literature, we could identify a mere three clinical trials that met the inclusion criteria, all studied exclusively animal (bovine, equine, and porcine) placenta derivatives. Moreover, a complex mixture of equine placental growth factors with pumpkin extract, panthenol, and niacinamide was tested in one of the trials in an uncontrolled manner, making any assessment of placenta effects virtually impossible [82]. One of the components in the mixture—niacinamide, contrary to expectations, might actually inhibit hair growth thus possibly counteracting the putative effects of other ingredients [102,103]. There are also four recent animal studies (three in mice, one in rats) with a design similar to the human trials, among them one of human placenta extract [104]. All four animal studies were controlled with minoxidil (Table 5).

Table 5.

An overview of animal studies on the influence of placenta products on hair growth (see Supplementary Materials, Table S2 for more details).

Altogether, the results from animal research suggest that the effects of placenta products on hair growth are comparable to minoxidil. Nevertheless, when looking at these data, one has to keep in mind the significant morphological and physiological differences between human hair and that of laboratory animals [107]. Moreover, laboratory models of hair loss used in these studies like fur shaving or chemical depilation have little in common with effluvium or alopecia in men and women.

Natural materials such as placenta products are mixtures of various compounds. Therefore, it is difficult to ascribe observed effects to particular placenta compounds and single out involved metabolic pathways. Moreover, various components may act synergistically or—on the contrary—mutually block their effects. More studies are needed to understand the complex mechanisms of the placenta’s influence on the hair and scalp. The available data are insufficient to confirm the safety of placental derivatives in cosmetics, hence many restrictions on their use. In addition to the rather modest body of evidence regarding the activity of placenta derivatives, safety concerns seem to be the major factor limiting their use in hair products nowadays.

5. Conclusions

The limited scientific evidence available to date seems to hint at the effectiveness of the placenta in both inhibiting hair loss and stimulating hair growth. Unfortunately, the number of human trials published to date is very limited and their quality is low. They also lack information on the concentration and composition of placenta derivatives. In order to make a definitive statement on the influence of the placenta and its derivatives on hair growth and hair loss, further, carefully designed, randomized controlled trials of well-defined placental products in patients with well-defined hair loss problems are needed to ultimately address the question about the value of the placenta in hair loss.

6. Future Perspective

In order to find a reliable answer to the question about the efficacy of the placenta and its derivatives in hair loss, we postulate that future clinical studies need to address the following:

- They should be designed as double-blind, randomized trials, controlled by the use of a matched comparator (placebo)—preferably an identical hair product devoid only of the placenta derivative tested, or replaced by minoxidil which is well-established in hair loss trials and routine clinical use.

- Studies should be conducted in patients with well-defined clinical diagnoses (AGA, TE, alopecia areata, etc.). The sizes of study groups should be sufficiently large to produce statistically meaningful data (e.g., hundreds, rather than dozens of patients).

- The studies should involve control groups of gender-, age-, nutrition-, and general health status-matched patients of similar sizes. Controls with the same disease should be preferred over healthy individuals.

- The observation time has to be sufficiently long, considering the velocity of hair growth and duration of the hair cycle phases of interest (we suggest at least 6 months for TE studies, which is within the range of a natural recovery after an acute episode of TE). Longer periods might be necessary for other types of hair loss, or when measuring hair-growth-promoting effects.

- The study outcomes should include objective measures, the number of hairs shed in one standardized combing and trichoscopy seem most suitable. Possible changes in the hair density or hair shaft thickness are likely to become noticeable after several months and would reflect hair growth-promoting, rather than hair-loss-preventing effects.

- When utilizing “investigator assessment” as the measure of effect, the assessment method should be standardized and clearly defined. Investigators should be blinded as to which of the compared photographs shows the “before” and which is the “after” status. Assessment by several investigators (“voting”) should be preferred over an assessment by a single investigator.

- Patient satisfaction and quality of life are important, therefore, patient-centered measures also should be used; however, their susceptibility to subjective bias should always be kept in mind.

- Tested placenta derivatives should be well defined: A minimal set of descriptors should include the animal source and processing protocol, as well as the concentration and placenta protein content in the final product. Other details should be given whenever possible, e.g., physicochemical properties, pH, spectroscopy, molecular weight, amino acid content, lipids, salt content, etc.

Aside from clinical efficacy, the safety of the tested products should always be a priority. This topic, however, was beyond the scope of the present study and deserves dedicated research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app142210301/s1, Table S1: A detailed overview of clinical trials in humans on the effectiveness of placenta products in hair loss. Table S2: A detailed overview of animal studies on the influence of placenta products on hair growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.; methodology, R.S. and E.S.; bibliographic query, E.S.; data extraction, E.S.; data curation, E.S. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and R.S.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jagiellonian University Medical College, grant number N42/DBS/000445.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burton, G.J.; Fowden, A.L. The placenta: A multifaceted, transient organ. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E. What is the placenta? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evain-Brion, D.; Malassine, A. Human placenta as an endocrine organ. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2003, 13, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turco, M.Y.; Moffett, A. Development of the human placenta. Development 2019, 146, 163428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.D.; Gupta, A. The Placenta-A Temporary, Multifunctional Organ Does Wonders for The Embryo. J. Gynecol. Reprod. Med. 2021, 5, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A.M.; Enders, A.C. Placentation in mammals: Definitive placenta, yolk sac, and paraplacenta. Theriogenology 2016, 1, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, H.W. Comparative morphogenesis of the fetal membranes and accessory uterine structures. Contrib. Embryol. 1937, 26, 129–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunton, C.; Kothari, S.; Smith, L.; Steele, D. A history of materials and practices for wound management. Wound Pract. Res. 2012, 20, 174–186. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, V.M.; Paradakar, A.R.; Mahadik, K.R. Human placenta: Potential source of bioactive compounds. Pharmacologyonline 2009, 1, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P.D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Aqueous extract of human placenta as a therapeutic agent. In Recent Advances in Research on the Human Placenta; Zheng, J., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lijuan, G.; Jingjie, L.; Zheng, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z. Cow placenta extract promotes murine hair growth through enhancing the insulin-like growth factor-1. Indian J. Dermatol. 2011, 56, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Mallick, S.; Mandal, S.K.; Das, M.; Dutta, A.K.; Datta, P.K. A human placental extract: In vivo and in vitro assessments of its melanocyte growth and pigment-inducing activities. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 411, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogozhykh, O.; Prokopyuk, V.; Figueiredo, C.; Pogozhykh, D. Placenta and Placental Derivatives in Regenerative Therapies: Experimental Studies, History, and Prospects. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 4837930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, K.; Komatsu, Y. Novel Placenta-Derived Liquid Product Suitable for Cosmetic Application Produced by Fermentation and Digestion of Porcine or Equine Placenta Using Lactic Acid Bacterium. Enterococcus faecalis PR31. Fermentation 2024, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations, Annex 2. WHO Tech. Rep. Ser. 1992, 823, 80–91. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/trs823-annex2 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Commission. CosIng—Cosmetics Ingredients Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/ (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. OJEU 2009, 342, 59–62. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1223/oj (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 laying down health rules as regards animal by-products and derived products not intended for human consumption and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 (Animal by-products Regulation). OJEU 2009, 300, 1–10. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1069/oj (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Wu, C.H.; Chang, G.Y.; Chang, W.C.; Hsu, C.T.; Chen, R.S. Wound healing effects of porcine placental extracts on rats with thermal injury. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 148, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, H.; Winckler, W.; Grundmann, U. Immunochemically detected placental proteins and their biological functions. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 1991, 249, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odorisio, T.; Cianfarani, F.; Failla, C.M.; Zambruno, G. The placenta growth factor in skin angiogenesis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2006, 41, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.; Elmore, A.R. Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Human Placental Protein, Hydrolyzed Human Placental Protein, Human Placental Enzymes, Human Placental Lipids, Human Umbilical Extract, Placental Protein, Hydrolyzed Placental Protein, Placental Enzymes, Placental Lipids, and Umbilical Extract. Int. J. Toxicol. 2002, 21, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisham, R.B.; Tukiran, N.A.; Jamaludin, M.A. Placenta in Cosmetic Products: An Analysis from Shariah and Legal Perspective in Malaysia. ESTEEM J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2024, 8, 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, J.P.; Roderuck, C.; Coryell, M.; Macy, I.G. Composition of the human placenta; vitamin content. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1946, 52, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Póvoa, G.; Diniz, L.M. Growth hormone system: Skin interactions. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2011, 86, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, P.; Scior, T.; Do, Q.T. Modulating testosterone pathway: A new strategy to tackle male skin aging? Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chang, S.; Lodico, L.; Williams, Z. Nutritional composition and heavy metal content of the human placenta. Placenta 2017, 60, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, E.J.; Chéret, J.; Paus, R. Growth Hormone and the Human Hair Follicle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine-Fenning, N.J.; Brincat, M.P.; Muscat-Baron, Y. Skin aging and menopause: Implications for treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 4, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martier, A.T.; Maurice, Y.V.; Conrad, K.M.; Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Mondrinos, M.J. Sex-specific actions of estradiol and testosterone on human fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation, bioenergetics, and vasculogenesis. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5950, Alanine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Alanine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6322, Arginine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Arginine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5960, Aspartic Acid: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Aspartic-Acid (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 171548, Biotin: Bethesda, Maryland, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Biotin (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5460341, Calcium: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Calcium (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for Collagen: Bethesda, MD, USA,, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Collagen (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 23978, Copper: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Copper (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 67678, Cystine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Cystine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Ota, T.; Chen, C.H.J.; Robinson, J.C. Cystine aminopeptidase and leucine aminopeptidase of choriocarcinoma cells grown in culture. Am. J. Obstet. Gyn. 1975, 122, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Schwarzer, V.; Bieber, T.; van der Ven, K.; Novak, N. Effects of histamine and diamine oxidase activities on pregnancy: A critical review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5757, Estradiol.: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Estradiol (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for Ferritin: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ferritin (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Dalton, C.J.; Lemmon, C.A. Fibronectin: Molecular Structure, Fibrillar Structure and Mechanochemical Signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 33032, Glutamic Acid: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Glutamic-Acid (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 750, Glycine.: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Glycine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Lowe, D.; Sanvictores, T.; Zubair, M.; Alkaline Phosphatase. StatPearls. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459201/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6274, Histidine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Histidine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for Human Chorionic Gonadotropin.: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Human-Chorionic-Gonadotropin (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Rassie, K.; Giri, R.; Joham, A.E.; Teede, H.; Mousa, A. Human Placental Lactogen in Relation to Maternal Metabolic Health and Fetal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6306, l-Isoleucine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/l-Isoleucine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 23925, Iron: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Iron (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Niki, T. 7—Immunohistochemistry of Laminin-5 in Lung Carcinoma. In Handbook of Immunohistochemistry and In Situ Hybridization of Human Carcinomas; Hayat, M.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6106, Leucine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Leucine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5962, Lysine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lysine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5462224, Magnesium: Bethesda, MD USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Magnesium (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6137, Methionine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Methionine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 938, Nicotinic acid: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Nicotinic-acid (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6613, Pantothenic Acid: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Pantothenic-Acid (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6140, Phenylalanine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Phenylalanine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Royal Society of Chemistry. Phosphorus. Available online: https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/15/phosphorus (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5462222, Potassium: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Potassium (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5994, Progesterone: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Progesterone (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 493570, Riboflavin: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Riboflavin (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6326970, Selenium: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Selenium (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5951, Serine.: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Serine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5360545, Sodium: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Sodium (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 170907453, Growth hormone: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Growth-hormone (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6013, Testosterone: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Testosterone (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 1130, Thiamine: .Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Thiamine (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6288, Threonine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Threonine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6305, Tryptophan: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Tryptophan (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6057, Tyrosine.: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Tyrosine (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6287, Valine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Valine (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 23930, Manganese: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Manganese (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 23994, Zinc: Bethesda, Maryland, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Zinc (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Kroløkke, C.; Dickinson, E.; Foss, K.A. The placenta economy: From trashed to treasured bio-products. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2018, 25, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. An analysis of the presence of ingredients that were declared by the producers as "active" in trichological shampoos for hair loss. Estetol. Med. Kosmetol. 2024, 14, 001.en. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, L.; Guagni, M. Zooceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients Derived from Animals. Cosmetics. 2022, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barat, T.; Abdollahimajd, F.; Dadkhahfar, S.; Moravvej, H. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cow placenta extract lotion versus minoxidil 2% in the treatment of female pattern androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2020, 6, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansathien, K.; Ngawhirunpat, T.; Rangsimawong, W.; Patrojanasophon, P.; Opanasopit, P.; Nuntharatanapong, N. In Vitro Biological Activity and In Vivo Human Study of Porcine-Placenta-Extract-Loaded Nanovesicle Formulations for Skin and Hair Rejuvenation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, J.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Park, E.S.; Kim, J.Y. Effectiveness of Hair Care Products Containing Placental Growth Factor for the Treatment of Postpartum Telogen Effluvium. Arch. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 23, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.R.; Oh, C.T.; Park, H.M.; Han, H.J.; Ji, H.J.; Kim, B.J. Potential synergistic effects of human placental extract and minoxidil on hair growth-promoting activity in C57BL/6J mice. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 40, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmezci, E.; Dündar, C.; Türkoğlu, M. A proprietary herbal extract against hair loss in androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium: A placebo-controlled, single-blind, clinical-instrumental study. Acta Derm. Venerol. 2018, 27, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P. Bald is beautiful? The psychosocial impact of alopecia areata. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.J.; Park, Y.S.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.Y. A Study on the Development of a Web Platform for Scalp Diagnosis Using EfficientNet. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, G.; Su, X.; Li, H.; Gong, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, F. Application of Non-Pharmacologic Therapy in Hair Loss Treatment and Hair Regrowth. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, L. Morphogenesis, Growth cycle and molecular regulation of hair follicles. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 899095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.M.; Khan, S.; Rawnsley, J. Hair biology: Growth and pigmentation. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 26, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, A.; Verma, R.; Singh, A.T. Review of hair follicle dermal papilla cells as in vitro screening model for hair growth. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, K.; Brown, M.; Stulberg, D.L. Common hair loss disorders. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 68, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Price, V.H. Treatment of hair loss. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, N.; Bashar, R.; Jimmy, A.N.; Khan, N.A. Unraveling Consumer Decisions towards Animal Ingredients in Personal-care Items: The Case of Dhaka City Dwellers. Am. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 6, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, C.; Barros, R.B.G. Natural and Organic Cosmetics: Definition and Concepts. Preprints 2020, 2020050374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sreen, N.; Rana, J.; Dhir, A.; Sadarangani, P.H. Impact of ethical certifications and product involvement on consumers decision to purchase ethical products at price premiums in an emerging market context. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2021, 19, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaouir, T.; Gustavsson, R.; Schmidt, N.; Factors Driving Purchase Intention for Cruelty-Free Cosmetics. A Study of Female Millennials in Jönköping, Sweden. Bachelor’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2019. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1320983&dswid=1908 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Cardoso, B.M.F. The Role of Cruelty-Free and Vegan Logos on Purchase Intention: Investigating the Effects of Certification, Logo Recognizability and Pro-Environmental Attitude. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University of Portugal, Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.ucp.pt/handle/10400.14/38362 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Betlloch, M.I.; Chiner, E.; Chiner-Betlloch, J.; Llorca-Ibi, F.X.; Martín-Pascual, L. The use of animals in medicine of Latin tradition: Study of the Tresor de Beutat, a medieval treatise devoted to female cosmetics. J. Ethnobiol. Trad. Med. 2014, 121, 752–760. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, G.A. Placental extract injections in the treatment of loss of hair in women. Int. J. Tissue React. 1982, 4, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, K.; Lee, H.; Yang, W.M. Human placenta induces hair regrowth in chemotherapy-induced alopecia via inhibition of apoptotic factors and proliferation of hair follicles. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Liu, B.; Miao, Y.; Hu, Z. Use of extracellular matrix hydrogel from human placenta to restore hair-inductive potential of dermal papilla cells. Regen. Med. 2019, 14, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, I.S.; Hardman, J.A.; Paus, R. Topically Applied Nicotinamide Inhibits Human Hair Follicle Growth Ex Vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1420–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblong, J.E.; Peplow, A.W.; Hartman, S.M.; Davis, M.G. Topical niacinamide does not stimulate hair growth based on the existing body of evidence. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2020, 42, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.S.; Lee, D.J.; Chung, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, B.J.; Jung, M.H.; Ha, K.T.; Jeong, H.S. Hominis Placenta facilitates hair re-growth by upregulating cellular proliferation and expression of fibroblast growth factor-7. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, A.I.; Sagita, E.; Iskandarsyah. Placenta extract-loaded novasome significantly improved hair growth in a rat in vivo model. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2023, 15, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Yoon, J.S.; Jo, S.J.; Shin, C.Y.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, J.I.; Kwon, O.; Kim, K.H. A role of placental growth factor in hair growth. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 74, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelsdorf, S.; Vergou, T.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J.; Patzelt, A. Comparative study of hair follicle morphology in eight mammalian species and humans. Skin Res. Technol. 2014, 20, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).