Featured Application

Hearing impairment is not a barrier in the development of an athlete’s physical fitness. Inclusion in sports participation and specific tools (i.e., communication aids) appear to be crucial factors in the performance enhancement of deaf and hard-of-hearing athletes.

Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was twofold: to identify the main trends and issues that are being addressed by researchers in the context of physical fitness and sports performance in deaf and hard-of-hearing (D/HH) athletes and to indicate the needs and future directions that should be implemented in the training process of athletes with hearing impairments. The methodology of this systematic review was planned according to PRISMA guidelines. A search of electronic databases (PubMed, EBSCO, Scopus) was conducted to identify all studies on physical fitness, sports performance and participation, and D/HH athletes from 2003 to 2024. In total, 87 full-text articles were assessed to determine eligibility, while 34 studies met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to detailed analysis and assessment of their methodological quality. The presented systematic review indicates evidence that D/HH athletes are characterized by a similar or higher level in selected motor abilities compared to hearing athletes. Moreover, it seems that hearing impairment is not a barrier in the development of an athlete’s physical fitness, including aerobic capacity, muscular strength and power or speed of reaction. Furthermore, inclusion in sports participation and specific tools (i.e., communication aids) appear to be crucial factors for performance enhancement.

1. Introduction

Beyond the different kinds of disabilities, there is a single variable that combines them all. Regardless of the form and severity of the impairment, people with disabilities are faced with various barriers, with social, physical and psychological issues seeming to be the most common [1,2]. However, there are some tools that can be used to overcome these barriers, among which sports are recognized as a universal platform whose importance cannot be overemphasized [3]. This is primarily because for the population of people with disabilities, sports have become a form of social inclusion and meaningful interaction through physical activity that can be undertaken together with both able-bodied individuals and those with various impairments [4]. Secondly, sports are known to enhance everyday life by impacting various motor abilities [5], which in turn contributes to improving self-reliance [6] in the population of people with disabilities/in those with disabilities. Lastly, sports are also a platform for self-actualization, especially in the form of training and competitions that allow athletes to strengthen self-character and to reinvent themselves [7].

As disability is a multidimensional concept [8], three main athletic movements can be indicated: (1) the Paralympic Games; (2) Deaflympics; and (3) the Special Olympics. Each of them is characterized by a long tradition; however, only deaf sports are confined to a small sample of the population of people with impairments [9]. Therefore, the uniqueness of sports for people with deafness gives them multiple opportunities, especially in the context of socializing with those who have similar social needs; nevertheless, at the same time, there are multiple challenges that should be taken into consideration, including communication [10].

Moreover, deaf and hard-of-hearing athletes seem to experience a different level of sports participation [11], which can be related mostly to the intrinsic differences in their morpho-functional development [12], which requires coaches to have special skills and the ability to adequately adapt methods and forms of training to the individual needs of the deaf athlete. One of the most challenging issues in the context of deaf sports is to deal with the effects of the intrinsic disturbances of the somatosensory and vestibular systems on athletic performance [13]. As was indicated by Assaiante et al. [14], the hearing and balance organs of the human body are closely related; thus, an impairment of the abovementioned systems impacts the muscular coordination mainly by reducing motor function and decreasing balance.

However, in the context of the Deaflympics, among the athletes that are eligible to compete in this event, there are no restrictions except for the loss of at least 55 dB in the better ear [15]. Compared to the Paralympic Games, there are not as many adaptations required for a single sports discipline as there are for multiple physical, visual or intellectual impairments [16]. This may affect the development of a unique sporting environment, in which only D/HH athletes can integrate and interact with the population of people with hearing impairments. It should also be admitted that deaf sports should be seen as a phenomenon that impacts both the social and physical aspects of people with deafness and the hard of hearing.

To date, several qualitative analyses concerning the population of people with deafness or hardness of hearing have been undertaken [17,18,19]; however, it is difficult to find a systematic analysis that has analyzed the issue of deaf sports. Simultaneously, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has revealed the main research trends and needs of the above-mentioned population within the sports context. Given the above and the gap in the current scientific literature, it seems justified to perform additional research in order to assess the variables that are related to the physical fitness and sports performance of deaf (D) and hard-of-hearing (HH) athletes.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was twofold (1): to identify the main trends and issues that are being addressed by researchers in the context of physical fitness and sports performance in D/HH athletes; and (2) to indicate the needs and future directions that should be implemented in the training process of athletes with hearing impairments. This may enable the enhancement of the sports performance of D/HH athletes mainly by reducing the number of barriers induced by the acquired or congenital impairment. It may also contribute to implementing in the training process the unique requirements that are associated with the disability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

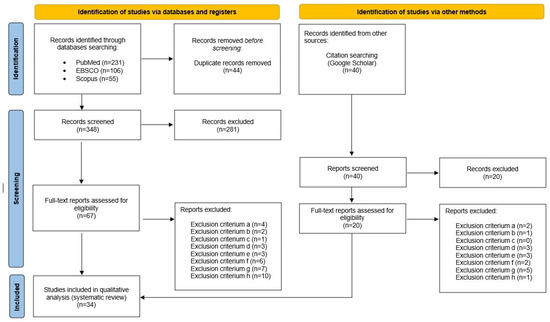

The methodology of this systematic review was planned according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20] (see Supplementary File S1).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In this systematic review, inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (a) cross-sectional study or comparative study (in order to determine athlete’s profile and not the impact of an intervention); (b) inborn/acquired hearing impairment; (c) hearing loss of at least 55 decibels (dB) in the better ear; (d) no cochlear implantation; (e) well-trained (training at least 3 times/week) athlete; (f) male and/or female athletes with hearing impairment ≥ 16 years old participating in sport competition; (g) no health condition except the hearing impairment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) article type other than cross-sectional or comparative study; (b) physical, intellectual or visual impairment; (c) hearing loss of less than 55 dB in the better ear; (d) poor methodological design; (e) well-trained/elite athletes were not the study group (opinion of parents/society); (f) no full-text available; (g) manuscript not in English language; (h) male and/or female athletes with hearing impairment under 16 years old.

2.3. Literature Search Strategy and Study Selection Process

A search of electronic databases (PubMed, EBSCO, Scopus) was conducted by two authors (E.G., J.P.-T.) to identify all studies on physical fitness, sport performance and deaf/HH athletes from 2003 to 2024 in order to analyze the most current available scientific data. The following methods were used: (a) data mining; (b) data discovery and classification. As a prerequisite, all studies were performed in healthy populations including males and females (≥16 years). Search terms were combined by Boolean logic (AND/OR) in the PubMed, EBSCO and SCOPUS databases. The search was undertaken using the following seven keyword combinations in English with the assumed hierarchy of their importance: ‘deaf’; ‘sport’; ‘athlete’; ‘hearing impairment’; ‘inclusion’; ‘hearing loss’; ‘performance’. Furthermore, two researchers (E.G., J.P.-T.) with expertise in adapted physical activity and hearing impairment reviewed the reference lists of the included studies and screened Google Scholar to find additional research. Moreover, if a systematic review was identified, the aforementioned authors (E.G., J.P.-T.) screened the references list in each of the identified qualitative analysis in order to define the missing studies. If the crucial data were not included in the original articles, corresponding authors were contacted directly by one of the authors of this present study (E.G.).

2.4. Data Extraction and Data Items

In order to determine which variables should be extracted, two independent researchers (E.G., J.P.-T.) used the Joanna Briggs institute (JBI) Qualitative Data Extraction Tool for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence [21], which was consequently updated by them as part of an independent process. The above-mentioned form included the following domains: (a) basic data; (b) methodology; (c) methods; (d) phenomena of interest; (e) setting; (f) geography; (g) culture; (h) participants; (i) data analysis; (j) author’s conclusions; and (k) reviewers’ comments. A third independent author (J.S.-R.) also checked the data for accuracy and consistency.

2.5. Methodological Quality of Included Studies (Risk of Bias)

In order to evaluate the risk of bias of the included studies, the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [22] for analytical and comparative cross-sectional studies was used. According to the current scientific literature [22], the JBI checklist is believed to be the newest and simultaneously the most preferred tool that can be used in order to assess the methodological quality of the above-mentioned kind of research. The JBI checklist consists of 8 items, which were scored as follows: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Unsure’, ‘Not applicable’. If the manuscript criterion was fulfilled, a ‘Yes’ was assigned to the analyzed item, and it simultaneously received score of one. If a ‘No’, ‘Unsure’ or ‘Not applicable’ was assigned to the evaluated item, a zero score was yielded. If missing data were identified, a ‘No’ was assigned. Two independent investigators with expertise in deaf sport and adapted physical activity (J.P.-T., J.S.-R.) read and ranked each of the included articles. Furthermore, an independent co-author (E.G.) was designated to resolve all discrepancies that could occur among the investigators during the assessment. The methodological quality was indicated by the total score (out of a possible 8 points) with the higher values representing the better quality of the included publications.

2.6. Synthesis Methods

In order to fulfil the aims of this study, manuscripts were grouped in a table created by a single researcher (E.G.) according to the main issue that was being examined by the authors of the selected research. In addition, they were summarized according to the year of publication, study design, sample size, type of sport, the research tool/test used during the measurement, the main outcomes, and the main findings of the study, including statistical results (if applicable).

3. Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

Figure 1 presents the flow of the systematic review. A total of 87 full-text articles were assessed to determine eligibility (see Table 1), while 34 studies met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to detailed analysis and assessment of their methodological quality (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram detailing the study inclusion process.

Table 1.

The assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies (risk of bias) using the JBI method for cross-sectional study.

Table 2.

The summary of the studies from 2003 to 2024 evaluating deaf sport, i.e., (I) sport performance; (II)—participation in deaf sport; (III) athlete–coach communication, (IV)—athlete’s quality of life and self-esteem.

Among 34 reports that had been assessed for their methodological quality, 16 were considered to score 8/8 points of eligibility to be included in the qualitative analysis. Seven articles were found to have 7/8 points of eligibility, four found were to have scored 6/8 points of eligibility, and five were assessed as scoring 5/8 points of eligibility. Moreover, two research studies were assessed as scoring 4/8 points of eligibility, which was the minimum score to be included into further analyses. The initial agreement of the two independent investigators (J.P-T., J.S.R.) was 90%. All discrepancies among the investigators were resolved by expert evaluation by an independent co-author (E.G.). Finally, 34 full-text articles were included in the systematic review (see Table 2).

4. Discussion

A careful examination of the current scientific data from the last two decades on the main trends and issues according to deaf sport and performance enhancement in D/HH athletes has indicated four main areas that are addressed by the researchers, i.e., (I) sport performance; (II) participation in deaf sport; (III) athlete–coach communication; and (IV) athlete’s quality of life and self-esteem. Moreover, this qualitative analysis found that the physical and physiological determinants of sport performance is a frequent topic analyzed in the scientific research. Interestingly, researchers focused not only on assessing the level of the cited variables in athletes with hearing impairments but also on the comparison of the analyzed variables with non-deaf athletes.

4.1. Sport Performance

Seven major variables can be identified according to the sport performance of D/HH athletes, namely (a) aerobic capacity, (b) reaction time, (c) postural control, (d) strength and power, (e) body composition, (f) nutrition and (g) concussion. The above-mentioned areas seem to be integrated; they can all impact on the athlete’s performance.

Among several factors that are listed in the domain of athletic performance, aerobic capacity assessed by VO2max test on a treadmill was the most frequent (see Table 2). Interestingly, out of three studies that included both D/HH athletes and non-deaf athletes [24,34,40], only a single study indicated greater values of the VO2max in the able-bodied group [40]. On the contrary, neither of the other two cited researches reported significant differences in the values of the VO2max, while at the same time indicating even lower results in the HR at 1st minute of recovery, which suggests a higher level of aerobic capacity [24,34]. Moreover, the study conducted by Milašius et al. [27] reported a longitudinal change in the level of aerobic performance in deaf athletes. As was found in the cited study, deaf players over years were characterized by improvement in the aerobic capacity, which simultaneously impacted the results of their sport performance. In light of the similarities in the aerobic capacity between deaf and non-deaf athletes, it would seem logical that vestibular disfunction does not define the athletic performance in this field.

Another important motor ability that is strictly related to the athletic performance is strength and power. The analyzed studies indicated across a wide range of methods of assessment the strength and power performance; however, a force plate was the most common (see Table 2). Also interesting and partly surprising was that several authors [36,44,48] found better strength and/or power level in D/HH athletes compared to non-deaf athletes. On the contrary, only a single study conducted by Soslu et al. [51] found decreased power performance in deaf athletes compared to the non-deaf group. Thus, it seems justified to conclude that the level of strength and power is related primarily to the training volume, its intensity and the training methods used, while its effectiveness seems not to be related to the disability of the vestibular system.

On the other hand, postural control seems to be highly decreased in athletes with hearing impairment compared to those who are able-bodied (see Table 2). All of the analyzed studies indicated that the above-mentioned kind of disability impacted on the variables that are related to postural control [35,46,47,50]. This phenomenon can also be linked to the intrinsic differences that occur as a result of activation different models of sensorial compensatory mechanisms due to the vestibular impairment [5]. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate the direct effect of different visual and hearing perceptions in order to enable generalization.

Another motor ability that is crucial for high sport performance is the speed of response. Unfortunately, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are only three research studies that have undertaken this aspect in the scientific analyses (see Table 2). Moreover, the present systematic review performed here has yielded a partially inconsistent findings: two research studies conducted by Tatlici et al. [38] and Güngör and Şahin [49] did not find any significant differences between D/HH athletes; however, the study performed by Soto-Rey et al. [28] found that athletes with hearing impairment are characterized by a shorter speed of response compared to those who are non-deaf. Based on the cited research, this phenomenon can be explained mainly by the type of sport practiced (team/individual). Moreover, male athletes seem to have a shorter speed of response compared to female athletes [28].

4.2. Participation in Deaf Sport

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the current available scientific studies in the context of participation in deaf sport are limited to three research studies (see Table 2); therefore, it is difficult to confirm the holistic perspective of strategies that are undertaken according to sport participation in the case of D/HH athletes. At the same time, it is difficult to confirm definitively the connection between the ways of participating and their impact on an athlete’s general fitness. Nevertheless, social inclusion seems to be the most important aspect that is related to the sport participation in this population [25,37]. For instance, the research conducted by Kurková et al. [25] pointed to the importance of inclusive competition between D/HH athletes and hearing athletes. This may be seen as a factor that can be related to the improvement of the sport performance in the population of athletes with hearing impairment due to enhancement of the individual level of sport-specific skills and motor abilities as a consequence of competing with non-impairment athletes. Secondly, this aspect may also be seen by D/HH athletes as a motivation for self-improvement of their physical fitness and athletic skill in order to be able to win against those who are not impaired. Partially similar findings were observed in the research by Vuljanic et al. [37], which were indicated on the inclusive system of competing in two aspects: (a) between deaf and hearing athletes, and (b) between deaf athletes seen as a separate group that is competing in an environment in which everyone is equal. However, further studies are needed to extend the perception of inclusion in the population of D/HH athletes.

4.3. Athlete Coach Communication

Undoubtedly, adequate communication between athlete and coach is a pillar for efficient cooperation. This issue is even more important in the case of D/HH athletes, in whom vestibular dysfunction is related to an intrinsic barrier to direct communication. All of the analyzed studies that are related to the above-mentioned issue (see Table 2) were consistent with regard to good communication with the coach being necessary in order to achieve high athletic performance [10,23,30,32]; however, some specific variables should be taken into consideration, including (a) the type of coach, (b) the gender of the coach/athlete and (c) the type of communication between the athlete and coach.

Based on the cited studies, it seems that hearing coaches (especially those with sign language skills) are more preferred by D/HH athletes compared to those who have hearing impairment [30,32]. Surprisingly, female athletes with disability of the vestibular system seem to have better communication compared to males [30,32]. Moreover, both sign language and oral communication seem to be received positively by the analyzed groups of athletes [10,23]; however, oral communication is likely more preferable for those who are HH [10].

4.4. Quality of Life and Self-Esteem

Another domain that is explored by multiple researchers within the context of sport performance of D/HH athletes is the quality of life and self-esteem. At the same time, as in the previously described areas of research, this domain is also limited to a small number of studies (see Table 2). Nevertheless, the researchers reached similar conclusions with regard to the relationship between sport performance and the athlete’s self-esteem and quality of life in that they seem to be intrinsically related.

With that in mind, this systematic review found that to be identified as a representative of athletes with hearing impairment is the predominant variable that decides on the quality of everyday life [4] and on the improvement in everyday satisfaction [11]. Moreover, the need to overcome obstacles, self-limits and barriers during competitions and training seems to impact on the level of self-esteem of D/HH individuals [31]. Interestingly, age and sport-specific experience seem not to be related to the level of self-esteem [33], although it must be noted that the main limitation of this topic is the limited number of research studies; thus, there is a need for the use of different surveys and protocols that should be implemented in order to provide wider scientific evidence.

4.5. Limitations

The presented qualitative analysis has several limitations that must be addressed. Even though the systematic review included two decades of available scientific research, there remain few data regarding the analyzed areas of research. On the other hand, this review simultaneously indicated the current trends in deaf sport, which enables the indication to be made of the directions that should be implemented in the future. Secondly, the analyzed data were related to various kinds of sports in which the studies’ protocols used different research tools and methods of assessment, which could be related to the different conclusions and inconsistency in the findings. Lastly, we have assessed only cross-sectional and comparative studies; thus, there may also be some experimental research that could contribute to the issue of sport performance in the context of deaf sport. However, in order to fully investigate this issue, further studies are needed.

5. Conclusions

The presented systematic review of the results of published scientific literature, on evidence, suggests that D and HH athletes tend to be similarly physically fit as hearing athletes. Moreover, it seems that hearing impairment is not a barrier in the development of selected groups of motor abilities, including aerobic capacity, muscular strength and power or speed of reaction. At the same time, multiple social and psychological factors seem to be associated with the sport performance of D and HH athletes, among which social inclusion and quality of life and self-esteem are the most common.

This systematic review also found a shortage of references in the sport sciences literature; thus, the population of deaf athletes presents an opportunity for novelty and originality in the field. Furthermore, inclusion in sport participation and specific tools (i.e., communication aids) appear to be crucial factors in their performance enhancement. In addition, specific features of this population and the activities influenced by their impairment when practicing sport appear as important areas to develop in the future (i.e., reaction time, postural control).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app14166860/s1, File S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and J.P.-T.; methodology, E.G.; validation, E.G. and J.P.-T.; formal analysis, E.G., J.P.-T. and J.S.-R.; investigation, E.G. and J.P.-T.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, E.G., J.P.-T. and J.S.-R.; visualization, E.G., J.P.-T. and J.S.-R.; supervision, A.Z.; funding acquisition, A.Z. and J.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zar, A.; Alavi, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Jafari, M. Effect of sport activities on the quality of life, mental health, and depression of the individuals with disabilities. Iran. J. Rehabil. Nurs. 2018, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Omura, J.D.; Hyde, E.T.; Whitfield, G.P.; Hollis, N.D.; Fulton, J.E.; Carlson, S.A. Differences in perceived neighborhood environmental supports and barriers for walking between US adults with and without a disability. Prev. Med. 2020, 134, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhamo, E.; Sibanda, P. Inclusion in sport: An exploration of the participation of people living with disabilities in sport. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Health Res. 2019, 3, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemček, D.; Mókušová, O. Position of sport in subjective quality of life of deaf people with different sport participation level. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2020, 87, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowska, A.; Gawlik, K.; Grabara, M. Deafness and motor abilities level. Biol. Sport 2008, 25, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D.A. Deaf Sport: The Impact of Sports Within the Deaf Community; Gallaudet University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, T.; Weber, K.M. The deaf athlete. Curr. Sport Med. Rep. 2006, 5, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Nikodelis, T.; Stojković, M. Significance of sport activities for persons with disabilities. Godišnjak Psihol. 2021, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.A.; McCarthy, D.; Robinson, J.A. Participation in deaf sport: Characteristics of deaf sport directors. APAQ 1988, 5, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, M.P.; Shingles, R.R. Communication patterns among athletes who are deaf or hard-of-hearing and athletic trainers: A pilot study. Athl. Train. 2015, 7, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemček, D.; Kručanica, L. Satisfaction with health status in people with hearing impairments. JSHS 2014, 51, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Zwierzchowska, A.; Bieńkowska, K.I. The significance of the physical and motor potential for speech development in children with cochlear implant (CI)—preliminary study. Logopedia 2017, 46, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Akınoğlu, B.; Kocahan, T. Stabilization training versus equilibrium training in karate athletes with deafness. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2019, 15, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assaiante, C.; Mallau, S.; Viel, S.; Jover, M.; Schmitz, C. Development of postural control in healthy children: A functional approach. Neural Plast. 2005, 12, 109–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szulc, A.; MBalatoni, I.; Kopeć, S. Audiometry and doping control in competitive deaf sport. Acta Med. Social. 2021, 12, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Tweedy, S.M.; Vanlandewijck, Y.C. International Paralympic Committee position stand—background and scientific principles of classification in Paralympic Sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.; Creed, P.; Hood, M.; Ching, T.Y.C. Parental Decision-Making and Deaf Children: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 2018, 23, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, E.; Simões, C.; Santos, A.C.; Mineiro, A. Resilience in deaf children: A comprehensive literature review and applications for school staff. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 1198–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yet, A.X.J.; Hapuhinne, V.; Eu, W.; Chong, E.Y.; Palanisamy, U.D. Communication methods between physicians and Deaf patients: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2841–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The PRISMA 2020 Statement: AN updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews|The EQUATOR Network. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Miami, FL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Ma, L.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 29, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochon, W.; Feinstein, S.; Soukup, M. Effectiveness of American Sign Language in Coaching Athletes Who Are Deaf. Online Submission 2006, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vujkov, S.; Dukic, M.; Drid, P. Aerobic capacity of handball players with hearing impairment. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2010, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurková, P.; Válková, H.; Scheetz, N. Factors impacting participation of European elite deaf athletes in Sport. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, N.A.; Açak, M.; Örer, G.E.; Savaş, S.; Coşkuner, Z. Comparison of max vo2 levels of elite and deaf footballers. Int. J. Sport Stud. 2012, 2, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Milašius, K.; Paulauskas, R.; Dadelienė, R.; Šatas, A. Body and functional capacity of Lithuanian deaf basketball team players and characteristics of game indices. BJSHS 2014, 119, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rey, J.; Pérez-Tejero, J.; Rojo-González, J.J.; Reina, R. Study of reaction time to visual stimuli in athletes with and without a hearing impairment. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2014, 119, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademir, T. Fear of negative evaluation of deaf athletes. Anthropologist 2015, 19, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acak, M. Evaluations of Deaf Team Athletes Concerning Professional Skills of Their Coaches. J. Rehabil. Health Disabil. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, W.; Marsh, H.W.; Hashimoto, K. Predictors and correlates of self-esteem in deaf athletes. Eur. J. Adapt. 2015, 8, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okan, I. Deaf Football Players’ Perception of the Coaches’ Occupational Skills. Anthropologist 2016, 25, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açak, M.; Kaya, O. A Review of Self-Esteem of the Hearing Impaired Football Players. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, E.A.; Kılıç, A.; Savaş, S.; Açak, M.; Bıyıklı, Z.; Töre, H.F. Deaf athlete: Is there any difference beyond the hearing loss? In Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala; Expert Projects Publishing House: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Volume 52, pp. 241–251. ISSN 1584-5397. [Google Scholar]

- Güzel, N.A.; Medeni, Ö.Ç.; Mahmut, A.C.A.K.; Savaş, S. Postural control of the elite deaf football players. JAPN 2016, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Szulc, A.M.; Buśko, K.; Sandurska, E.; Kołodziejczyk, M. The biomechanical characteristics of elite deaf and hearing female soccer players: Comparative analysis. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2017, 19, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Vuljanić, A.; Tišma, D.; Miholić, S.J. Sports-anamnesis profile of deaf elite athletes in Croatia. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference on Kinesiology, Opatija, Croatia, 10–14 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tatlici, A.; Çakmakçi, E.; Yilmaz, S.; Arslan, F. Comparison of visual reaction values of elite deaf wrestlers and elite normally hearing wrestlers. TJSE 2018, 20, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüs, M.; Eler, S. Evaluation of Physical and Physiological Characteristics of the Olympic Champion Turkish Deaf Men’s National Handball Team. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuls, F.; Botek, M.; Krejci, J.; Panska, S.; Vyhnanek, J.; McKune, A. Performance-associated parameters of players from the deaf Czech Republic national soccer team: A comparison with hearing first league players. Sport Sci. Health 2019, 15, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akınoğlu, B.; Kocahan, T. The effect of deafness on the physical fitness parameters of elite athletes. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2019, 15, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimešová, I.; Krejčí, J.; Botek, M.; Neuls, F.; Sládečková, B.; Valenta, M.; Panská, S. Hydration status and the differences between perceived beverage consumption and objective hydration status indicator in the Czech elite deaf athletes. Acta Gymnica 2019, 49, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, M.; Jablonskienė, V.; Abaravičius, J.A.; Stukas, R. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Diet Quality Profile of the Lithuanian Team of Deaf Women’s Basketball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buśko, K.; Kopczyńska, J.; Szulc, A. Physical fitness of deaf females. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 12, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suner-Keklik, S.; Çobanoğlu, G.; Savas, S.; Seven, B.; Nihan, K.A.F.A.; Güzel, N.A. Comparison of Shoulder Muscle Strength of Deaf and Healthy Basketball Players. IJDSHS 2020, 3, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobanoglu, G.; Suner-Keklik, S.; Gokdogan, C.; Kafa, N.; Savas, S.; Guzel, N.A. Static balance and proprioception evaluation in deaf national basketball players. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2021, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaracı, Y.; Soslu, R.; Özer, Ö.; Uysal, A. Center of pressure-based postural sway differences on parallel and single leg stance in Olympic deaf basketball and volleyball players. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2021, 17, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaracı, Y.; Özer, Ö.; Soslu, R.; Uysal, A. Bilateral counter movement jump, squat, and drop jump performances in deaf and normal-hearing volleyball players: A comparative study. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2021, 17, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, A.K.; Şahin, Ş. Comparison of Mental Rotation and Reaction Time Performances In Deaf Athletes And Non-Athletes. SPORMETRE J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2022, 20, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, M.P.; Talarico, M.K.; Boucher, L.C.; Yang, J.; Merfeld, D.; Onate, J.A. Hearing Status and Static Postural Control of Collegiate Athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2023, 58, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soslu, R.; Özer, Ö.; Uysal, A.; Pamuk, Ö. Deaf and non-deaf basketball and volleyball players’ multi-faceted difference on repeated counter movement jump performances: Height, force and acceleration. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2022, 4, 941629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapici, H.; Soylu, Y.; Gulu, M.; Kutlu, M.; Ayan, S.; Muluk, N.B.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Al-Mhanna, S.B. Agility Skills, Speed, Balance and CMJ Performance in Soccer: A Comparison of Players with and without a Hearing Impairment. Healthcare 2023, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, M.P.; Shingles, R.R.; Weber, Z.A. Effect of Hearing Status on Concussion Knowledge and Attitudes of Collegiate Athletes. J. Sport Rehabil. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).