Abstract

Remote, online learning provides opportunities for flexible, accessible, and personalised education, regardless of geographical boundaries. This study mode also promises to democratise education, making it more adaptable to individual learning styles. However, transitioning to this digital paradigm also brings challenges, including issues related to students’ mental health and motivation and communication barriers. Integrating social robots into this evolving educational landscape presents an effective approach to enhancing student support and engagement. In this article, we focus on the potential of social robots in higher education, identifying a significant gap in the educational technology landscape that could be filled by open-source learning robots tailored to university students’ needs. To bridge this gap, we introduce the Robotic Study Companion (RSC), a customisable, open-source social robot developed with cost-effective off-the-shelf parts. Designed to provide an interactive and multimodal learning experience, the RSC aims to enhance student engagement and success in their studies. This paper documents the development of the RSC, from establishing literature-based requirements to detailing the design process and build instructions. As an open development platform, the RSC offers a solution to current educational challenges and lays the groundwork for personalised, interactive, and affordable AI-enabled robotic companions.

1. Introduction

Education trends increasingly favour remote and online study settings [1,2], which have been praised for offering new learning venues and flexibility in location and scheduling [2,3,4]. Despite these advantages, numerous studies have identified issues students face in such settings, including problems with mental health, motivation, distractions, communication, and time management, as well as technical difficulties [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The COVID-19 pandemic further emphasised these challenges, underlining the profound impact of isolation on students’ learning capabilities and emotional health [7,8,9]. Social robots as physical artificial-intelligence (AI) agents in human–AI interaction may be a promising approach to facilitating personalised learning experiences, reducing loneliness, and providing academic support.

There are many tools used to facilitate personalised interactive learning, e.g., computer and web-based programs [10,11,12], smartphone apps [13,14,15], and robots [16,17]. However, existing research indicates that students learn more and comprehend better with physical robots than with their virtual counterparts [17,18,19,20]. Social robots have proven valuable in primary and secondary education, aiding in language learning [21,22] and personalised instruction [17,18,19] and helping to support special-needs students [23,24,25]. However, their application in higher education remains largely unexplored [20]. This presents a significant opportunity, especially in university environments, where the focus on self-directed study and lecture-based learning necessitates the use of efficient and self-motivating learning strategies for academic success [20].

Studies with social robots in education predominantly utilise pre-existing robots [26], neglecting the exploration of technical features required explicitly for university students [27]. Additionally, multiple factors impede the integration of social robots into higher education, such as stock limitations due to market disruptions, privacy concerns, limited customisability, and few affordable options [26,28]. One approach to addressing these issues is to develop open-source hardware (OSHW) solutions. According to [29], OSHW projects can enhance teaching methods, foster creativity and engagement, support distance learning, and reduce costs while increasing transparency in design and manufacturing. They also provide broader applicability because they incorporate publicly modifiable solutions for individual needs [30].

Robotic companions are described as consistently helpful, interactive social robots designed to assist human users over extended periods [31]. Thus, these robots have the potential to provide educational support while offering a reassuring physical presence to students [18], especially during isolated study sessions. Robotic companions specialising in study support could aid students in reflecting on and monitoring their progress [32,33], providing feedback through insights into learning strategies and exam preparation [27,33]. They can also enable educators to effectively track student progress, identify areas requiring focus, and support struggling students [34,35].

This paper presents the open-source Robotic Study Companion (RSC), a physical desktop social robot designed for human–AI interaction with learners in higher education (Figure 1). Using cost-effective off-the-shelf components, university students can build and customise their own RSC, enabling them to adapt it to their learning styles. We summarise the contributions of our paper as follows:

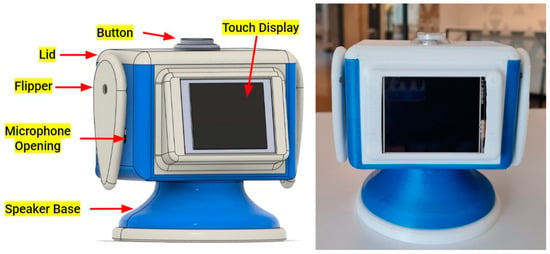

Figure 1.

Fully assembled 3D-printed open-source Robotic Study Companion (RSC) (left) and a learner sitting at a desk with the RSC (right).

- Based on the literature (Section 2), we developed requirements (Section 2.4) for an RSC tailored to the needs of university students and highlight the main design considerations based on the needs of students and educators.

- We designed and implemented the hardware and software for an RSC with multimodal human–robot interaction (Section 3).

- We have documented and released our solution as an open-source hardware project in a public repository on GitHub [36] and invite others to replicate and improve on our solution.

2. Related Works and Requirements

In recent years, social robots have emerged as promising tools for enhancing learning across various educational contexts [17,18,20,21,22,23,24,28,37,38,39]. These robots can range in design from humanoid to animal-like to abstract or biomimetic designs [26,40]. Some have been primarily researched for classroom use, with researchers focusing on improving educational quality [26,37]. Although most of the research on social robots in education focuses on children [20], studies indicate that many of these robots fail to meet the specific needs and preferences of learners in higher education [27]. The Softbank Robotics’ humanoid robot Nao is often used in research and has been praised for enhancing learning experiences [37,41] but is impractically expensive for most students [42]. On the other hand, during the COVID-19 pandemic, student-designed robots like Moody Study Buddy [8] and AMIGUS [9] emerged; these models focus on providing students with emotional support and are built using off-the-shelf components. However, these robots lack features such as adaptive learning, subject-specific assistance, and collaborative learning opportunities for university students [20,27,41]. Furthermore, their development frameworks offer limited avenues for open contributions and customisation, restricting their adaptability to diverse educational needs and settings.

This section further delves into works related to social robots used in education and research, starting with teacher and student perspectives (Section 2.1) on the use of social–educational robots. We review and synthesise the design and interaction modalities of various commercially available social robots (Section 2.2) and natural language processing, along with the potential of generative AI technologies (Section 2.3), to inform the design decisions we made in creating a social Robot Study Companion (RSC). Finally, we conclude this section by formulating a set of requirements (Section 2.4) to aid in guiding the creation of a physical human–AI-interacting RSC prototype for university students.

2.1. Teacher & Student Perspectives

Social–educational robots [26,43] enhance learning by providing subject-specific support and serving as personal tutors. A study on German teachers’ attitudes [41] showed a preference for robots as individual or small-group tutors. Teachers expect robots to improve motivation, act as information sources, assess progress, and provide support. They also sought classroom-ready robots with voice control. However, they had concerns regarding programming workload, maintenance, acquisition costs, and budget constraints. International studies [34,35,44,45,46] highlighted the engagement potential of social robots for all students but raised challenges in regard to equitable access, classroom disruptions, privacy, and cross-cultural adaptation.

Reich-Stiebert et al. [27] investigated 116 university students’ preferences with regard to educational-robot design, interaction modes, and personality traits. Most preferred a medium-sized (~100 cm), machine-like robot in gender-neutral colours with speech as the primary interaction mode, followed by a touch screen, gestures, and touch. Key desired features included facial and emotional recognition and a display of positive emotions, while negative personality traits like pessimism were viewed unfavourably. The study emphasised the need to consider different learning environments and personal factors, such as motivation, privacy, safety, and ease of handling, in the design of these robots.

Studies indicate that personalised robot tutors enhance task performance and interaction in university settings [17], with their physical presence aiding measurable learning gains [18]. Research on university tutoring revealed that students are interested in exam-preparation assistance and exhibit a preference for more time spent in interaction [20]. These studies suggest significant potential for robot study companions with personalised features to improve learning outcomes, underscoring the role of social robots in higher education.

2.2. Design and Interaction Modalities of Social Robots

Jibo, launched in 2014, is a 30 cm tall, 2 kg desktop robot designed for emotional connection through voice interaction, expressive interfaces, and lifelike movements [47]. Despite its multifaceted interaction capabilities [48], Jibo’s design has raised concerns about surveillance and limited portability. The company has transitioned to new ownership [49], and acquiring a Jibo remains challenging due to its inconsistent market availability and prohibitive cost. Honda Robotics introduced Haru, a robot akin to Jibo, in 2018.

Haru is a tabletop robot with a minimalist design for emotional and long-term interaction featuring a 22-centimetre base, animated eyes, and an LED display [50,51]. It excels as a multimodal communicative agent [52] but faces challenges in portability and maintainability. Like Jibo, Haru’s market unavailability, reliance on proprietary components, and closed-source software limit its customisability and availability to most students, failing to alleviate the concerns of teachers and students regarding affordability and accessibility.

Moxie, a socially interactive robot companion developed by Embodied, was designed to promote social, emotional, and cognitive development in children aged 5–10 [53], particularly those on the autism spectrum [19]. While its endearing design and portability make it appealing, Moxie’s high cost, privacy concerns due to built-in cameras and microphones [54], and lack of customizability limit its suitability for use in higher education. Moxie is accompanied by a companion app that provides parents with insights into their child’s interactions with the robot; however, its availability is limited to certain countries, which further impedes its global accessibility.

Robots like Anki’s Cozmo (released in 2016) and Vector (released in 2018) effectively promote engagement and collaboration in educational contexts with their animated, expressive features [23,55]. However, despite their cute and engaging design and affordability, these closed-source robots are also no longer sold. In contrast, the open-source ElectronBot enables a hands-on approach to building a desktop companion robot using DIY 3D printing [56], providing a more accessible option for students. While it addresses the accessibility concern, it lacks the sophistication and advanced features desired by university students for their educational needs.

The DIY desktop robot Mira [57,58], modelled after ‘Pia the robot’ [58], and Eilik [59] explore diverse physical forms and interaction modalities for affective (emotional) communication and interactions. Additionally, ElliQ, a robot companion designed to aid older adults in various activities to support their well-being, has achieved commercial success but is primarily tailored for use by older adults [60,61]. These affordable, entertaining desktop social robots offer valuable insights into interactive social human–robot interaction (HRI) [62]. However, their focus on entertainment may limit their suitability for educational purposes, as they lack the features and functionalities necessary for effective subject-specific support and personal tutoring.

Many of the commercial robot platforms listed above [19,49,51,59,61,63] often have limited manufacturing cycles, making them less accessible in the long term. Additionally, many of these platforms [54] are cost-prohibitive and offer limited customisability, even though customisability is essential for meeting the diverse needs of university academic settings [27]. These challenges highlight the need for a new, affordable, open-source platform targeting this demographic.

2.3. NLP & GenAI Technologies

The advancement of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has been pivotal in fostering speech-based human–robot interactions, the most common modality in social robots [26,64]. NLP technologies such as Conversational Intelligent Tutoring Systems (C-ITS) offer tailored instruction and have demonstrated their versatility in various educational domains, including algebra tutoring [65], Scratch programming [66], and serving as an AI-assisted tutor [67]. However, these technologies are intangible and lack the engagement of a physical robot [18,19]. The Google AIY Voice Kit [68] was a notable attempt to combine hardware assembly with voice-enabled applications [69]. However, as of January 2023, this AIY project is now archived and no longer supported for further development.

Generative AI (GenAI) expands on traditional NLP systems by enabling robots and machines to generate coherent, contextually appropriate responses. This advancement empowers not only chatbots, virtual assistants, and conversational agents, but also conversational agents within physical robots, facilitating more natural human–AI interaction.

The deployment of large pre-trained language models such as Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) [70] demonstrates significant potential in facilitating rapid prototyping for physical robot applications [71,72,73,74]. This emerging application allows for the integration of APIs like GPT-3 [70,75] into the Robot Study Companion (RSC), transforming it into a personalised physical AI robot capable of enhanced interactions.

2.4. Requirements for the RSC

Designing social robots is an involved, multifaceted process spanning physical and functional considerations, brought to life with software. To guide the design, features, and personality of an RSC for university students, we formulated the following requirements (Table 1) based on the literature outlined above. We observe that to establish effective human–AI interaction, the RSC should feature multimodal communication (Req 1 in Table 1) and a portable and customizable design (Req 2), in addition to being readily available (Req 3). These requirements will enable interactive conversation and learning support (Req 4), aligning with the principal role of an RSC, which is to assist and monitor studies, facilitating personalised learning experiences [17,20,33]. Finally, the RSC should be reliable and secure (Req 5, 6).

Table 1.

Literature-Derived Requirements for Robot Study Companions.

In summary, the RSC should have a compact, visually appealing design and interact with users through speech while offering additional interaction modalities. It should engage in interactive conversations, support learning, and adapt to individual student needs. Finally, the RSC should be user-friendly, secure, and reliable. In this paper, we document the prototype development of the RSC as a new open-source desktop social robot study companion platform.

3. Design and Implementation

The Robotic Study Companion (RSC) presented in this article is an affordable, open-source desktop robot (Table 2; Figure 2) designed primarily to serve as a social and physical AI agent to support learning for university students. Featuring a sleek and friendly design, the RSC is made from off-the-shelf components, supporting reconfigurability and balancing cost and performance. All the custom mechanical components are 3D-printed to ensure scalability, availability, and further customisation of the platform. The RSC aims to enrich learning experiences by facilitating multimodal human–AI interaction including visual, auditory, and tactile communication cues (Table 3). It employs three main feedback modes—light, motion, and sound—to provide subtle, intuitive, and informative cues. This multimodal approach offers diverse ways for users to engage, with the option of activating modalities based on preference, enhancing the study sessions and interactions.

Table 2.

Overview of open-source RSC hardware specifications.

Figure 2.

Computer-Aided Design (CAD) model (left) and fully assembled 3D-printed RSC (right). Existing desktop robot-companion solutions (discussed in Section 2.2) inspired the RSC’s design. As a result, the RSC’s small form-factor tabletop solution features curved edges, circular shapes, and outward shells that are neutral in colour [76]. It houses the speaker within the base and secures the remaining peripherals within its rectangular body.

Table 3.

Overview of social-interaction modalities.

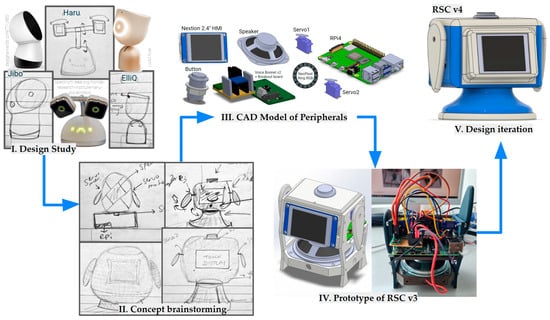

To continuously develop the RSC, we adopt the Design Science Research Method [77] to systematically create a purposeful artefact to meet the outlined challenges. We document insights gained throughout the design process in an approach akin to the design thinking model [51], which emphasises rapid design iterations and building on the understanding gained with each implementation. We rely on previous studies and discussions (Section 2) to inform the prototype’s creation, aiming to benefit the open-source community and enable future refinements.

3.1. Design

This section highlights the design process, files, and features. The mechanical design of the RSC helped bring to life the required features, particularly those relating to verbal and non-verbal social interaction (Table 3). Given the compactness and multimodal-interaction requirements (Req 1), the main challenge was packing several components into a confined space, keeping them protected, and enabling tool-free maintenance access. The RSC (Figure 2) adopts an hourglass-like shape, which sits comfortably in the hand (Req 2). We employed snap-fit assembly to house the internals with the construction parts (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Design-file summary; more information in the project’s GitHub repository [36].

Table 5.

Bill of materials for the RSC.

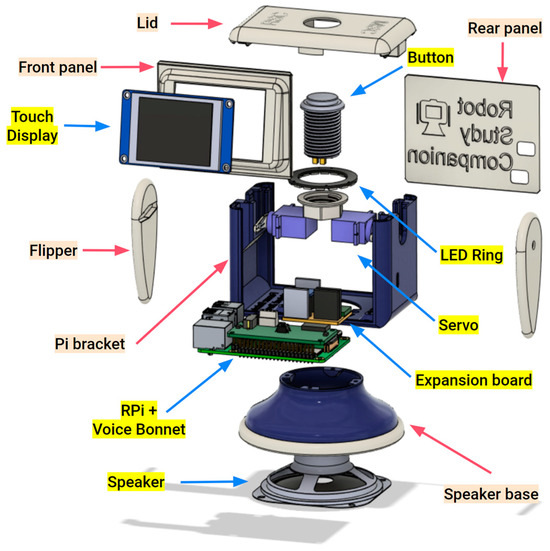

The top lid (white) features an arcade button and snaps into place (Figure 3), locking the front and back panels. The front panel, featuring a small screw-mounted touch display, slides into place with the help of guide grooves embedded in the main body (blue, Pi bracket). Similarly, the rear panel, with openings for power-supply connectors, also slides into place using these grooves. On either side of the main (blue) body are two small, flat, conical servo-mounted flippers (white). The servos rotating the flippers are press-fit into the main body. At the base of the RSC is a screw-attached bell shape (blue speaker base) hiding an embedded bottom-firing speaker and ending with a round anti-slip padding detail (white).

Figure 3.

Exploded assembly view of the RSC. Components are denoted by yellow highlights and blue arrows, while 3D-printed construction parts are indicated by orange highlights and red arrows. More information on the assembly can be found on the project’s GitHub page [36].

The RSC’s design overall prioritises a cost-effective, portable solution at ~11 cm high and a weight of ~375 g. Our RSC prototype-development process (Figure 4) helped establish the size, shape, and peripheral placement. The Pi bracket houses bespoke slots that fit servos to actuate the flippers and features openings for both microphones (Figure 2 and Figure 3). In addition to the arcade button, the lid houses an LED ring. We chose a blue-and-white colour palette to give the device a friendly appearance [76], using white and blue polylactic acid (PLA) 3D-printing filament. The base is printed out of white thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) filament, which improves grip and stability on desktop surfaces.

Figure 4.

Process of design thinking and rapid prototyping development. The progression involves (I.) conducting a design study to investigate features of existing social robots, a step that is followed by (II.) brainstorming and concept sketching. Subsequently, (III.) component modelling is carried out in CAD-enabled layout exploration. The initial prototype design was an open-enclosure test assembly to secure all components (IV.). This test assembly helped document additional design insights. The RSC was ready for further development after identified issues had been addressed and additional features incorporated (V.).

All CAD files for this design are available in the MechDesign repository in our replication package [78] with ready-to-print files and assembly instructions.

3.2. Bill of Materials

The Bill of Materials (BOM; Table 5) lists all main components needed to reproduce the RSC, including component names with quantities, descriptions, and associated costs (in EUR). The RSC costs amount to ~240EUR at the time of writing. An extended, up-to-date BOM can be found in the project’s repository [36].

3.3. Electronics

This section outlines component integration and peripheral communication protocols. To meet the requirements for multimodal, responsive interaction (Req 1), the RSC must be able to hear and playback audio, which is why we chose the AIY Voice Bonnet v2 [68,79]. It features a button connector, a dual speaker terminal, integrated left and right microphones, headers to connect servo motors and serial devices, and documentation with examples of use [80]. The Voice Bonnet’s drivers also come pre-packaged with a ready-to-use operating system image [81]. We used a Raspberry Pi single-board computer because it was turnkey and compatible with the AIY Voice Bonnet and drivers. Specifically, we used model 4B with 8 GB RAM [82] (state-of-the-art at the time of development), as it provides shorter compilation times than did previous-generation models.

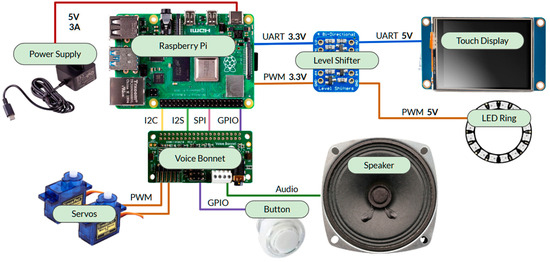

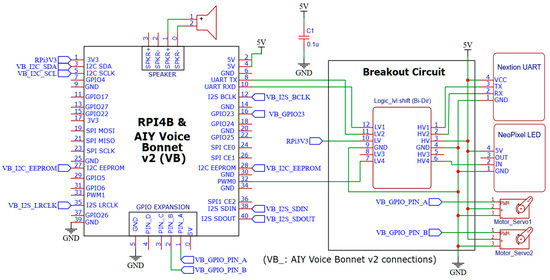

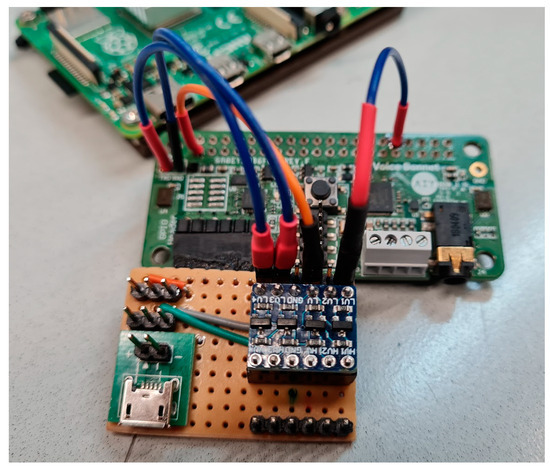

We integrated several peripheral devices (Figure 5) to meet RSC requirements, using a custom expansion board to power the connected devices (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This board includes a logic-level shifter circuit, ensuring communication with peripherals operating at different voltage levels.

Figure 5.

Simplified system-communication diagram.

Figure 6.

RSC Electronics schematic.

Figure 7.

Custom expansion board installed in the AIY Voice Bonnet extension header. Depicted on the brown protoboard to the right is a bidirectional logic level shifter (blue). To the left of the protoboard is a USB power-supply connector and two servo pin headers.

The HMI Nextion touch display [83] talks with the RPi using the universal asynchronous receiver transmitter (UART) protocol. It is connected through the expansion board headers and requires logic-level conversion (3.3 V to 5 V). The RGB NeoPixel LED ring [84], connected through the expansion board, also requires logic-level conversion for reliable pulse-width-modulated (PWM) communication. On the other hand, the servo motors [85] work with the 3.3 V level PWM signal from the RPi, routed through the Voice Bonnet to the expansion board, where they connect and receive 5 V power. Finally, the arcade button connects to a dedicated general-purpose input–output (GPIO) header on the Voice Bonnet [79].

This schematic (Figure 6) outlines the connections and layout for a Raspberry Pi 4B integrated with an AIY Voice Bonnet v2, detailing the connectivity for multiple peripherals. It shows direct speaker connections, the expansion board (Figure 7) with a logic level shifter [86] for interfacing between the Raspberry Pi and the Nextion UART touch display and NeoPixel LED at different voltage levels, and two servos controlled via PWM.

Additional files are available in the ElectroCircuits folder of the repository [36,78].

3.4. Software Architecture

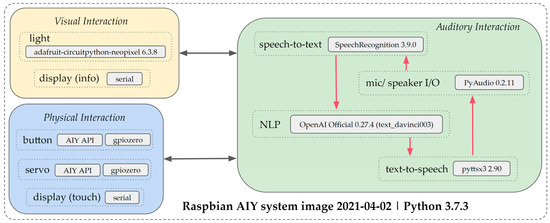

This section describes the software architecture and libraries in the development process. While the voice bonnet connects the peripherals, the RPi handles the processing. The AIY Voice kit [68] ships with a Debian/Raspbian-based system image [87] and a Python library [79] for working with the Voice Bonnet and connected peripherals. Preparing the RSC prototype involved integrating various components and software libraries to enable its functionality and provide seamless user interaction.

To provide coherent, context-aware text responses that enable engaging, interactive conversations, we selected OpenAI’s text_davinci003, a variant of the Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) model [88]. OpenAI’s official Python library (v0.27.4) [89] provided a convenient, user-friendly interface for their NLP API.

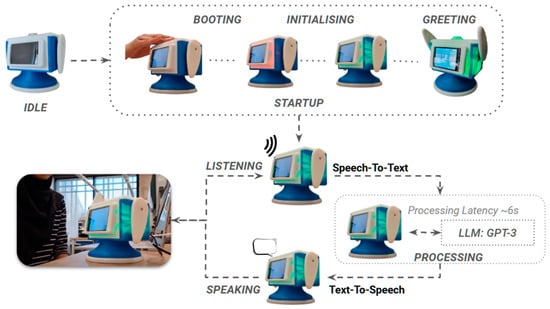

The RSC, in its current state, engages users using a demo interaction loop (Figure 8) that was written in Python v3.7.3 [90] using compatible speech and language-processing libraries. Multiple speech-processing libraries enable automatic speech-to-text (STT) and text-to-speech (TTS) transcription. ‘PyAudio’ v0.2.11 [91] helps the RSC listen and speak by accessing the microphones (record audio) and speaker (play audio). The ‘SpeechRecognition’ library v3.9.0 [92] allows the RSC to interpret spoken user inputs by transcribing spoken language (audio) into written text. The ‘pyttsx3’ library v2.90 [93] enables the RSC to respond to responses by converting text to speech (audio).

Figure 8.

Interaction–state loop diagram. After the loop starts, a brief setup phase commences. Once it is ready for user input (question), the RSC listens, transcribes spoken words into text, and sends the question to OpenAI for processing. The RSC then ‘speaks’ the response from the API to the user.

In addition to audio-related libraries, the RSC also features additional peripherals and their libraries (Figure 9). The ‘adafruit-circuitpython-neopixel’ library version 6.3.8 [94] integrates and controls the NeoPixel RGB LED ring. It provides an interface for managing the colour and brightness of the 16 individually addressable NeoPixel LEDs on the ring. This level of customizability allows for dynamic lighting effects, contributing to the interactive experience.

Figure 9.

HRI block diagram and library flow. Auditory interaction (green, right) incorporates preinstalled libraries: AIY (enabling Voice Bonnet I/O access), pyttsx3 (text-to-speech), and pyaudio (audio input/output). We installed OpenAI and SpeechRecognition to facilitate comprehensive auditory interaction. To accommodate physical (blue, bottom left) and visual (yellow, top left) interactions, we installed the CircuitPy and Adafruit-NeoPixel libraries. Both physical and visual interaction are governed by auditory interaction (NLP).

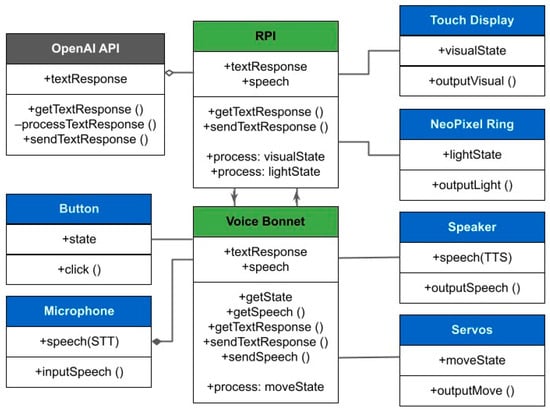

The ‘AIY Voice Bonnet’ library [79,87], in addition to providing access to the speaker and microphones, also provides access to servos and buttons connected to the Voice Bonnet. We aimed to establish a basic interactive and functional baseline for the RSC that can be continuously improved and expanded on in an open-source community. The class diagram (Figure 10) illustrates how all the peripherals communicate with their qualities (attributes) and data operations (methods).

Figure 10.

Class diagram illustrating all the peripherals of the RSC, including various objects, their attributes, and data operations.

The visibility of an attribute or method sets the accessibility for that attribute or method: a private (−) method cannot be accessed by another class, whereas another class can access a public (+) method. The lines represent the relationship between objects and classes. The empty diamond terminator denotes that OpenAI API operates independently of the RPi because the computation is offloaded to the OpenAI services. Meanwhile, the filled diamond terminator shows that audio input via the microphone depends on the Voice Bonnet.

All code files can be found in the CodeStation folder of the repository [36,78].

4. Results and Discussion

This section discusses the ongoing work on the RSC prototype, documents its limitations, and assesses how well it meets our established requirements.

4.1. Requirements Analysis

Research indicates that university students can improve their comprehension and learning outcomes by interacting with physical robots rather than virtual human–AI interaction counterparts, especially when these robots feature practical, machine-like designs that are easy to handle and minimise learning interruptions [17,18,19,20,27,41]. Building on these and other insights, we derived a set of requirements (Table 1) from related works (Section 2) to guide the development of a Robotic Study Companion (RSC). Table 6 provides an overview of the outcomes of this development process and the extent to which the RSC meets the requirements described in Table 1.

Table 6.

Analysis of the RSC prototype with respect to requirements.

The prototype RSC we designed and implemented features a student-centric design and incorporates remote large language model (LLM) services packaged in a visually appealing manner that supports interactive conversations. However, the RSC still needs to deliver a fully personalised learning experience. Videos demonstrating the prototype RSC in action can be found in the Supplementary Materials [95].

The RSC prototype developed in this study successfully implements several user-centred design elements derived from our background literature review (Section 2). However, while the prototype has made significant strides in design, affordability, and open-source availability, there remain challenges in achieving optimal performance, learning support, and reliability, indicating substantial opportunities for continued development.

As an open-source project, the RSC offers global accessibility and the potential for significant market impact without traditional barriers, such as cost or market availability. Teachers’ expectations (Section 2.1) were met because the prototypes improve motivation, act as information sources, and are classroom-ready robots with voice control. The multimodal, portable, and modular design was created to empower students, giving them greater autonomy by serving as a study support robot. The RSC distinguishes itself from other existing social robot companions (Section 2.2) by using readily available components to create an open development platform. It can support isolated study sessions where motivation is critical and provide a more engaging and interactive physical presence compared to conventional screen-based methods. This enhances the potential for reflective engagement and supports a richer variety of interaction modes, delivering additional value in educational settings.

4.2. Preliminary User Evaluation

Formally assessing the various educational use cases of the RSC is one plan for ongoing work. However, we conducted an informal survey to gather preliminary user impressions during a two-hour student design competition event held in May 2023 at the University of Tartu. We displayed the prototype RSC, and eight (N = 8) students shared their feedback using a Google form after briefly interacting with the prototype (max 5 min). Overall, the feedback was positive, with many supportive comments; for example, students said, “I liked the prototype and I would like to see its further development” and “Very promising prototype with some unfortunate glitches”.

Initial comments touching on the aesthetic included descriptions such as “tiny”, “cute”, “small robot tutor”, “geeky”, and “interesting”. Participants also ranked their preferred interaction modes, with speech and touch as top priorities, followed by gestures, with web/text/chat-based in last place. Their main concerns were privacy and affordability, in line with requirements (Req 3, 6). Participants suggested improving the RSC with remarks such as “make it portable by adding batteries and [add] touch sensors for more interaction” and “use better voice generator [for] more input and output options”. One participant shared their screen preference: “I would love to see a bigger screen on it …”, while another noted they would prefer a more compact, flipper-free design: “I actually don’t think the arms are necessary, and it could be made more compact without them”.

As we continue to develop the RSC, we are conducting ongoing cross-cultural user evaluations at partner universities to validate the use cases of the RSC. The successful integration and utility of the Robot Study Companion (RSC) hinge on its acceptance and usability, which require comprehensive evaluation through user studies, planned as part of our future research. In designing the RSC, we adhered to the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) principles [96,97], focusing on perceived ease of use and usefulness—key factors for user adoption. Although empirical validation of the RSC’s acceptance and effectiveness is pending, we expect these design considerations to promote platform adoption among university students. We foresee the RSC’s utilisation in university settings in individual and group exam-study sessions, in laboratories to store and communicate information, and as a motivational reminder for students during study sessions.

4.3. Limitations & Future Work

While developing the RSC prototype, we encountered several limitations that influenced the final prototype and identified areas for future exploration and refinement. These limitations encompassed various domains, including technical constraints, software challenges, and the absence of extensive user evaluations. Regardless, each limitation reveals a unique set of difficulties and learning opportunities.

The prototype’s electronic system faces several power-supply challenges. Notably, the absence of an integrated battery restricts the device’s portability to areas with power outlets. We initially estimated the peak power draw of all devices could exceed 15W. During development, we included a USB connector to attach a second power supply in case this became a recurring issue. We do not recommend using two separate power supplies due to the risk of ground loops, voltage-level variances and uneven load distribution. An alternative solution for this scenario is to use a higher-rated power supply.

Relying on a custom expansion board means users aiming to build their own RSC must understand the electronics and how to use specialised tools, complicating basic setup and maintenance. Additionally, the wiring in the prototype’s internals is highly disorganised (see ElectroCircuits [36]), causing excessive crosstalk and interference. Meanwhile, the end-of-life status of the Voice Bonnet v2 without OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) support limits future scalability and hinders maintenance options. Finally, the servos we used produce power-line noise when active due to insufficient power-line filtering, impacting overall system reliability.

Mechanically, the servos emit loud noises due to insufficient sound-dampening measures. We could mitigate this issue by switching to higher-quality servos or alternate motor types, like small brushless direct-current gimbal motors. At the same time, the single degree of freedom of both flippers limits the prototype’s expressive motion gestures. Adding encoder-based odometry and perhaps a more sophisticated shoulder joint with more degrees of freedom could substantially enrich the prototype’s functionality and expressiveness. Finally, we observed durability concerns with regard to the LCD panel and the lid-panel locking mechanism, which typically lasts ~100 cycles in regular use. These issues indicate a need for design improvements to enhance longevity and the user experience.

One of the significant technical constraints involved optimising the accuracy and reliability of the open-source speech-to-text and text-to-speech systems, particularly concerning handling diverse accents and dialects and ensuring their integration with the RSC. Despite leveraging the pyttsx3 library to enhance voice communication, the generated voice maintained a robotic timbre and presented comprehensibility challenges, indicating a need for further work to provide a more natural and engaging text-to-speech solution to enhance social interaction (Req 1).

Google’s archiving of AIY projects and the associated GitHub repositories in February 2023 made finding support and documentation more difficult, slowing overall progress. Integrating OpenAI’s NLP API created an additional issue by introducing latency due to the offloading of computation to online services, impacting real-time interactions. For instance, users wait approximately 6 s when starting a conversation and an additional 3 s before receiving a reply to a question. The effect of this delay on overall immersion when studying with the RSC needs to be investigated. At the same time, development should focus on optimising the software and hardware integration to reduce latency and improve the system’s overall responsiveness.

During the prototyping phase in spring 2023, we utilised OpenAI’s GPT-3 (text_davinci003) API, which was considered state-of-the-art at the time but which was deprecated in January 2024. While this LLM (GPT-3) allows for subject-specific interactions that can be motivating during the conversation, the system does not retain this context-specific engagement after the conversation ends, limiting the RSC’s effectiveness in supporting sustained study goals. Future enhancements will focus on developing a functional software stack capable of analysing student interactions. This study engine must include adapting responses to enhance learning experiences through personalisation and gamification to keep users engaged beyond their initial interactions (Req 4).

Another priority of technical future developments (Req 3, 4, 5) should include enhancing system stability to support longer uptimes without interruptions. Updated documentation will remain essential, ensuring all users can easily set up, maintain, and benefit from the RSC without extensive technical knowledge. Lastly, for the RSC to achieve ongoing security and privacy (Req 6), it should adopt a zero-trust-like architecture. With this approach, the RSC must rely on local processing, which should enhance data security. This shift will require substantial changes in how the RSC handles data, including the development of local LLM inference capabilities that do not compromise the functionality or responsiveness of the device.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the gap in social robotics for university students by developing an open-source Robotic Study Companion (RSC) platform. We derived insights from an extensive literature review that helped us formulate precise requirements, guiding the RSC prototype’s design and development. We present the resulting prototype, which was built using off-the-shelf components and integrates OpenAI’s conversational API, leveraging its capacity to simplify complex concepts and enhance human–AI interaction.

The RSC embodies a step towards creating accessible, customisable, and cost-effective human–AI learning companions. The RSC has the potential to positively impact the future of education, facilitating more engaging and personalised learning experiences for university students. The RSC platform is under active development, and we welcome external contributions. More information can be found in the project’s repository [36], replication package [78], and demo videos [95].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://github.com/RobotStudyCompanion/RSC2023 (accessed on 25 May 2024). Our replication package: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11962698 (accessed on 18 June 2024). Videos: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11671444 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.; methodology, F.B. and M.B.Z.; software, F.B.; validation, F.B. and M.B.Z.; formal analysis, F.B. and M.B.Z.; investigation, F.B.; resources, F.B.; data curation, F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.; writing—review and editing, F.B., M.B.Z. and K.K.; visualization, F.B. and M.B.Z.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All files, including CAD designs, code, and images related to this study, are available under open-source licenses on our GitHub page at: https://github.com/RobotStudyCompanion/RSC2023 (accessed on 25 May 2024) or https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11962698 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the recognition received at the HCII2023, where our project was awarded a Bronze Prize in the Student Design Competition, and at ICSR2023, for a Special Mention in the Robot Design Challenge. We also thank the OSHWA for featuring our project in Make Magazine, which has supported our visibility and outreach.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ratten, V. The Post COVID-19 Pandemic Era: Changes in Teaching and Learning Methods for Management Educators. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Singleton, E.S.; Hill, J.R.; Koh, M.H. Improving Online Learning: Student Perceptions of Useful and Challenging Characteristics. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, L.; Lei, M. Challenges of Online Learning amid the COVID-19: College Students’ Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1037311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mawee, W.; Kwayu, K.M.; Gharaibeh, T. Student’s Perspective on Distance Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Western Michigan University, United States. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2021, 2, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrot, J.S.; Llenares, I.I.; del Rosario, L.S. Students’ Online Learning Challenges during the Pandemic and How They Cope with Them: The Case of the Philippines. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7321–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheshlagh, R.G.; Ahsan, M.; Jafari, M.; Mahmoodi, H. Identifying the Challenges of Online Education from the Perspective of University of Medical Sciences Students in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Q-Methodology-Based Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, S.A.; Ajlouni, A.O. Undergraduates’ Perspectives and Challenges of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case from the University of Jordan. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2021, 12, 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J. Moody Study Buddy: Robotic Lamp That Keeps Students’ Company During the Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 8 March 2021; pp. 642–644. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, C.; Alamo, A.; Raez, R. AMIGUS: A Robot Companion for Students. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Sapporo, Japan, 7–10 March 2022; pp. 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoors, R.; Elen, J.; Raes, A.; Depaepe, F. An Overview of 25 Years of Research on Digital Personalised Learning in Primary and Secondary Education: A Systematic Review of Conceptual and Methodological Trends. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1798–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciss, S.; Sosnovsky, S.; Schnaubert, L.; Andrès, E.; Eichelmann, A.; Goguadze, G.; Melis, E. Exploring Feedback and Student Characteristics Relevant for Personalizing Feedback Strategies. Comput. Educ. 2014, 71, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboleva, E.V.; Zhumakulov, K.K.; Umurkulov, K.P.; Ibragimov, G.I.; Kochneva, L.V.; Timofeeva, M.O. Developing a Personalised Learning Model Based on Interactive Novels to Improve the Quality of Mathematics Education. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2022, 18, em2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, M.A.; Bardesi, H.J. Towards Adaptive Mobile Learning System. In Proceedings of the 2011 11th International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems (HIS), Melacca, Malaysia, 5–8 December 2011; pp. 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Ingkavara, T.; Panjaburee, P.; Srisawasdi, N.; Sajjapanroj, S. The Use of a Personalized Learning Approach to Implementing Self-Regulated Online Learning. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabudi, T.; Pappas, I.; Olsen, D.H. AI-Enabled Adaptive Learning Systems: A Systematic Mapping of the Literature. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.; Spaulding, S.; Westlund, J.K.; Lee, J.J.; Plummer, L.; Martinez, M.; Das, M.; Breazeal, C. Affective Personalization of a Social Robot Tutor for Children’s Second Language Skills. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 17 February 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyzberg, D.; Spaulding, S.; Scassellati, B. Personalizing Robot Tutors to Individuals’ Learning Differences. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 3 March 2014; pp. 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Leyzberg, D.; Spaulding, S.; Toneva, M.; Scassellati, B. The Physical Presence of a Robot Tutor Increases Cognitive Learning Gains. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Sapporo, Japan, 1–4 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, N.; Clabaugh, C.E.; Baynes, R.; Cohn, J.F.; Mitroff, D.; Scherer, S. Social and Emotional Skills Training with Embodied Moxie. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnermann, M.; Schaper, P.; Lugrin, B. Integrating a Social Robot in Higher Education—A Field Study. In Proceedings of the 2020 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Naples, Italy, 31 August–4 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kanero, J.; Geçkin, V.; Oranç, C.; Mamus, E.; Küntay, A.C.; Göksun, T. Social Robots for Early Language Learning: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, N. Learning French with Sophie—Personal Robots Group. Sophie the Language Learning Companion 2012. Available online: https://robots.media.mit.edu/portfolio/learning-french-sophie/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Balasuriya, S.S.; Sitbon, L.; Brereton, M.; Koplick, S. How Can Social Robots Spark Collaboration and Engagement among People with Intellectual Disability? In Proceedings of the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction, Fremantle, Australia, 2–5 December 2019; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, G.A.; Sidiropoulos, G.K.; Papadopoulou, C.I.; Vrochidou, E.; Kaburlasos, V.G.; Papadopoulou, M.T.; Holeva, V.; Nikopoulou, V.-A.; Dalivigkas, N. Social Robots in Special Education: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why Do Children with Autism Learn Better from Robots? Available online: https://luxai.com/blog/why-children-with-autism-learn-better-from-robots/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Mahdi, H.; Akgun, S.A.; Saleh, S.; Dautenhahn, K. A Survey on the Design and Evolution of Social Robots—Past, Present and Future. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 156, 104193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich-Stiebert, N.; Eyssel, F.; Hohnemann, C. Exploring University Students’ Preferences for Educational Robot Design by Means of a User-Centered Design Approach. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Webb, N.; Strzalkowski, T. Nelson: A Low-Cost Social Robot for Research and Education. In Proceedings of the 42nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 9 March 2011; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Heradio, R.; Chacon, J.; Vargas, H.; Galan, D.; Saenz, J.; De La Torre, L.; Dormido, S. Open-Source Hardware in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 72094–72103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellermann, M.; Jolles, J.W.; Ortiz, D.; Seabra, R.; Wenzel, T.; Wilson, H.; Tanner, R.L. Open Hardware in Science: The Benefits of Open Electronics. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2022, 62, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzierski, J.; Kaczmarek, P.; Dziergwa, M.; Tchoń, K. Design for a Robotic Companion. Int. J. Humanoid Robot. 2015, 12, 1550007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Social Robot Reading Partner for Explorative Guidance. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/epdf/10.1145/3568162.3576968 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Yun, H.; Fortenbacher, A.; Pinkwart, N. Improving a Mobile Learning Companion for Self-Regulated Learning Using Sensors. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 April 2017; pp. 531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Serholt, S.; Barendregt, W.; Leite, I.; Hastie, H.; Jones, A.; Paiva, A.; Vasalou, A.; Castellano, G. Teachers’ Views on the Use of Empathic Robotic Tutors in the Classroom. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Edinburgh, UK, 25–29 August 2014; Volume 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ceha, J.; Law, E.; Kulić, D.; Oudeyer, P.-Y.; Roy, D. Identifying Functions and Behaviours of Social Robots for In-Class Learning Activities: Teachers’ Perspective. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, F. RobotStudyCompanion/RSC2023: Replication Package for RSC (Robotic Study Companion) v1 (2023). Available online: https://github.com/RobotStudyCompanion/RSC2023 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Belpaeme, T.; Kennedy, J.; Ramachandran, A.; Scassellati, B.; Tanaka, F. Social Robots for Education: A Review. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaat5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, H.; Ponce Chulani, J.; Merino, L.; Szapiro, D.; Gomez, R. Developing a Lightweight Rock-Paper-Scissors Framework for Human-Robot Collaborative Gaming. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 202958–202968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABii’s World by Van Robotics. Available online: https://www.smartrobottutor.com (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Breazeal, C.; Dautenhahn, K.; Kanda, T. Social Robotics. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer Handbooks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1935–1972. ISBN 978-3-319-32552-1. [Google Scholar]

- Reich-Stiebert, N.; Eyssel, F. Robots in the Classroom: What Teachers Think About Teaching and Learning with Education Robots. In Proceedings of the Social Robotics; Agah, A., Cabibihan, J.-J., Howard, A.M., Salichs, M.A., He, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Vaudel, C. NAO Robot V5 Open Box Edition for Schools. Available online: https://www.robotlab.com/store/naov5-open-box-edition (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Reich-Stiebert, N.; Eyssel, F. Learning with Educational Companion Robots? Toward Attitudes on Education Robots, Predictors of Attitudes, and Application Potentials for Education Robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewijk, G.; Smakman, M.; Konijn, E. Teachers’ Perspectives on Social Robots in Education: An Exploratory Case Study. In Proceedings of the Interaction Design and Children Conference, London, UK, 17–24 June 2020; Volume 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Lemaignan, S.; Belpaeme, T. The Cautious Attitude of Teachers Towards Social Robots in Schools. In Proceedings of the Robots 4 Learning Workshop at RO-MAN 2016, New York, NY, USA, 26–31 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Hyun, E.; Kim, M.; Cho, H.-K.; Kanda, T.; Nomura, T. The Cross-Cultural Acceptance of Tutoring Robots with Augmented Reality Services. JDCTA 2009, 3, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIBO—By DESIGN TEAM/HUGE DESIGN/Core77 Design Awards. Available online: https://designawards.core77.com/home/award_permalink?id=34998&category_id=1 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Yeung, G.; Bailey, A.L.; Afshan, A.; Tinkler, M.; Perez, M.Q.; Pogossian, A.A.; Spaulding, S.; Park, H.W.; Muco, M.; Breazeal, C. A Robotic Interface for the Administration of Language, Literacy, and Speech Pathology Assessments for Children. In Proceedings of the 8th ISCA Workshop on Speech and Language Technology in Education, Graz, Austria, 20–21 September 2019; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, A. Jibo, the Social Robot That Was Supposed to Die, Is Getting a Second Life. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2020/7/23/21325644/jibo-social-robot-ntt-disruptionfunding (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Haru: An Experimental Social Robot From Honda Research—IEEE Spectrum. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/haru-an-experimental-social-robot-from-honda-research (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Gomez, R.; Szapiro, D.; Galindo, K.; Nakamura, K. Haru: Hardware Design of an Experimental Tabletop Robot Assistant. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Chicago, IL, USA, 26 February 2018; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Meet Haru, the Unassuming Big-Eyed Robot Helping Researchers Study Social Robotics—IEEE Spectrum. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/honda-research-institute-haru-social-robot (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- The World’s First AI Robot for Kids Aged 5–10. Available online: https://moxierobot.com/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Ziouzios, D.; Chatzisavvas, A.; Baras, N.; Kapris, G.; Dasygenis, M. An Emotional Intelligent Robot for Primary Education: The Software Development. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Preveza, Greece, 24–26 September 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Khordi-moodi, M.; Lohan, K.S. Social Robot for STEM Education. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1 April 2020; pp. 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.-H. ElectronBot: Mini Desktop Robot 2023. Available online: https://github.com/peng-zhihui/ElectronBot (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Mira the Baby Robot—Background Research—16-223 Work. Available online: https://courses.ideate.cmu.edu/16-223/f2018/work/2018/09/12/mira-the-baby-robot-background-research/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Marco Mira the Robot Waits for You to Smile. Available online: https://www.personalrobots.biz/mira-the-robot-waits-for-you-to-smile/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Eilik. Available online: https://store.energizelab.com/products/eilik (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- World, S. ElliQ Is an Emotionally Intelligent, Intuitive Robot Sidekick for the Ageing. Available online: https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-elliq-is-an-emotionally-intelligent-intuitive-robot-sidekick-for-the-ageing (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- ElliQ. The Sidekick for Healthier, Happier Aging. Available online: https://elliq.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Caudwell, C.; Lacey, C.; Sandoval, E.B. The (Ir)Relevance of Robot Cuteness: An Exploratory Study of Emotionally Durable Robot Design. In Proceedings of the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 10 January 2020; pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cozmo vs Vector—5 Differences between Them, and Which One Is Better. The Answer Might Surprise You!—What Is the Difference between the Two? Available online: https://ankicozmorobot.com/cozmo-vs-vector/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Fadelli, I.; Xplore, T. A Robotic Planner That Responds to Natural Language Commands. Available online: https://techxplore.com/news/2020-03-robotic-planner-natural-language.html (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Albornoz-De Luise, R.S.; Arnau-González, P.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M. Conversational Agent Design for Algebra Tutoring. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Prague, Czech Republic, 9–12 October 2022; pp. 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Katchapakirin, K.; Anutariya, C. An Architectural Design of ScratchThAI: A Conversational Agent for Computational Thinking Development Using Scratch. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Advances in Information Technology, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 10 December 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Axios Login: Khan’s AI Tutor. Available online: https://www.axios.com/newsletters/axios-login/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Voice Kit from Google. Available online: https://aiyprojects.withgoogle.com/voice/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Lin, P.-C.; Yankson, B.; Chauhan, V.; Tsukada, M. Building a Speech Recognition System with Privacy Identification Information Based on Google Voice for Social Robots. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 15060–15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Matuszek, C.; Mead, R.; Depalma, N. Scarecrows in Oz: The Use of Large Language Models in HRI. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot. Interact. 2024, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hasler, S.; Tanneberg, D.; Ocker, F.; Joublin, F.; Ceravola, A.; Deigmoeller, J.; Gienger, M. LaMI: Large Language Models for Multi-Modal Human-Robot Interaction. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understanding Large-Language Model (LLM)-Powered Human-Robot Interaction. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/epdf/10.1145/3610977.3634966 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Theory of Mind Abilities of Large Language Models in Human-Robot Interaction: An Illusion? Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/epdf/10.1145/3610978.3640767 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Loos, E.; Gröpler, J.; Goudeau, M.-L.S. Using ChatGPT in Education: Human Reflection on ChatGPT’s Self-Reflection. Societies 2023, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman-Pincu, E.; Parmet, Y.; Oron-Gilad, T. Judging a Socially Assistive Robot by Its Cover: The Effect of Body Structure, Outline, and Color on Users’ Perception. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot. Interact. 2023, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Brocke, J.; Hevner, A.; Maedche, A. Introduction to Design Science Research. In Design Science Research: Cases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-3-030-46780-7. [Google Scholar]

- Baksh, F.; Zorec, M. RobotStudyCompanion-RSC2023-Replication-Package; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voice Kit Overview—Documentation. Available online: https://aiyprojects.readthedocs.io/en/latest/voice.html#voice-bonnet-voice-kit-v2 (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- AIY Voice Bonnet at Raspberry Pi GPIO Pinout. Available online: https://pinout.xyz/pinout/aiy_voice_bonnet (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- AIY Projects—Github Repo. Available online: https://github.com/google/aiyprojects-raspbian (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Buy a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/raspberry-pi-4-model-b/ (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Nextion NX3224T024. Available online: https://nextion.tech/datasheets/nx3224t024/ (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Adafruit NeoPixel Ring—16 × 5050 RGB LED with Integrated Drivers. Available online: https://www.adafruit.com/product/1463 (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- DFRobot DF9GMS 360 Degree Micro Servo (1.6 Kg). Available online: https://core-electronics.com.au/towerpro-sg90c-360-degree-micro-servo-1-6kg.html (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Pololu—Logic Level Shifter, 4-Channel, Bidirectional. Available online: https://www.pololu.com/product/2595 (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Releases Google/Aiyprojects-Raspbian. Available online: https://github.com/google/aiyprojects-raspbian/releases (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Models|GPT-3.5. Available online: https://platform.openai.com (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- OPENAI. OpenAI Python Library. Available online: https://github.com/openai/openai-python (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Python Release Python 3.7.3. Available online: https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-373/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Pham, H. PyAudio: Cross-Platform Audio I/O with PortAudio. Available online: https://people.csail.mit.edu/hubert/pyaudio/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- SpeechRecognition—Github. Available online: https://github.com/Uberi/speech_recognition#readme (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Bhat, N. Pyttsx3: Text to Speech (TTS) Library for Python 2 and 3. Available online: https://github.com/nateshmbhat/pyttsx3 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- CircuitPython Essentials. Available online: https://learn.adafruit.com/circuitpython-essentials/circuitpython-neopixel (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Baksh, F.; Zorec, M. RSC2023 Demo Videos; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse-Based Learning Platforms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.C.; Su, X.; Lin, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, N.; Zhang, Y. Determinants of Technology Acceptance: Two Model-Based Meta-Analytic Reviews. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2021, 98, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).