Abstract

Emotion is a significant factor influencing education and teaching, closely intertwined with learners’ cognitive processing. Conducting analysis of learners’ emotions based on cross-modal data is beneficial for achieving personalized guidance in intelligent educational environments. Currently, due to factors such as data scarcity and environmental noise, data imbalances have led to incomplete or missing emotional information. Therefore, this study proposes a collaborative analysis model based on attention mechanisms. The model extracts features from various types of data using different tools and employs multi-head attention mechanisms for parallel processing of feature vectors. Subsequently, through a cross-modal attention collaborative interaction module, effective interaction among visual, auditory, and textual information is facilitated, significantly enhancing comprehensive understanding and the analytical capabilities of cross-modal data. Finally, empirical evidence demonstrates that the model can effectively improve the accuracy and robustness of emotion recognition in cross-modal data.

1. Introduction

Currently, the new generation of information technology represented by artificial intelligence has become an important driving force for innovative changes in teaching. The new generation of information technology led by artificial intelligence is redefining and changing the connotations, structure, and ecology of education and teaching. Artificial intelligence technology helps to achieve personalized learning paths and precise recommendations for learning resources and can solve the problem of large-scale personalized teaching. In this context, the development of the Internet of Things sensing technology has made it possible to obtain large-scale cross-modal data, such as emotion recognition [1], behavior recognition [2], and video retrieval [3]. Based on the analysis of students’ learning states using cross-modal teaching process data, it is possible to accurately grasp the individual state of each student, thereby helping to achieve large-scale and quality personalized education.

Emotional learning is an important factor in students’ learning states, and the recognition of students’ learning emotions plays a crucial role in implementing personalized tutoring. Through analyzing students’ non-verbal information such as facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language during classroom learning, it is possible to more accurately grasp students’ learning motivations, emotional states, and cognitive loads, thus effectively identifying students’ learning difficulties and emotional barriers [4]. This is crucial for promoting students’ emotional well-being, enhancing their interest and efficiency in learning, and even stimulating their proactive learning enthusiasm. Furthermore, emotional recognition can also facilitate personalized teaching. Through deeply exploring the emotional states of all students, teachers can provide personalized guidance and support based on each student’s individual circumstances.

There have been many research results on the extraction of emotional states, such as methods based on local information. Firstly, facial keypoints or key regions were manually selected and local features were then extracted for expression classification (Pantic et al., 2004 [5]; Bashyal et al., 2008 [6]; Cheon et al., 2009 [7]). Subspace feature extraction methods, focusing on the overall facial features, were employed to obtain the optimal transformation under certain criteria, projecting high-dimensional data into a low-dimensional space, retaining only discriminative features for facial expression classification in the subspace, thereby achieving the goal of dimensionality reduction, correlation elimination, and improved classification performance (Shan et al., 2006). However, traditional emotion-recognition models mainly have relied on unimodal data, such as text or speech [8]. While this unimodal approach can provide useful emotion-recognition results in specific contexts, the accuracy of recognition results is not high. Unimodal emotion-recognition models often struggle to fully capture and understand students’ emotional states. This is because emotional expression in students’ learning processes is multidimensional, including language, tone of voice, facial expressions, and even body posture [9], These multimodal pieces of information collectively provide a more comprehensive reflection of individuals’ emotional states. Therefore, through employing multimodal emotion recognition models, it is possible to significantly enrich the dimensions of educational assessment, enhance the quality and effectiveness of education and teaching, and achieve a more humane and intelligent educational environment.

However, achieving more scientific, comprehensive, reasonable, and real-time personalized tutoring for learners based on cross-modal teaching process data still faces many difficulties. In many cases, the real facial images acquired in the classroom have numerous issues such as occlusion, small targets, image blurring, non-frontal faces, etc. The incompleteness of information and environmental noise further increase the difficulty of emotion recognition. To address these challenges, this study proposes a collaborative perception model based on attention mechanisms. This model integrates multimodal data from visual, audio, and text sources and enhances the synergistic learning effect between modalities through a specially designed interaction layer. Such a design aims to dynamically adjust the focus on different modal data, thereby improving the accuracy of emotion recognition and overcoming the adverse effects of data incompleteness and environmental noise. It aims to better explore the potential information in cross-modal teaching process data to achieve intelligent tutoring for individuals and groups and has significant research and application value.

2. Related Works

2.1. Cross-Modal Feature Fusion

Cross-modal feature fusion is a crucial technique that plays a vital role in both cross-modal learning and cross-modal applications. Its core objective is to integrate information from different modalities to establish a richer and more comprehensive model representation, thereby enhancing the performance and effectiveness of the system. Multimodal data often encompasses information from various domains such as visual, textual, and auditory sources. These pieces of information are interrelated and complementary to each other. Therefore, how to effectively integrate them has become one of the focal points of research.

2.1.1. Early Fusion

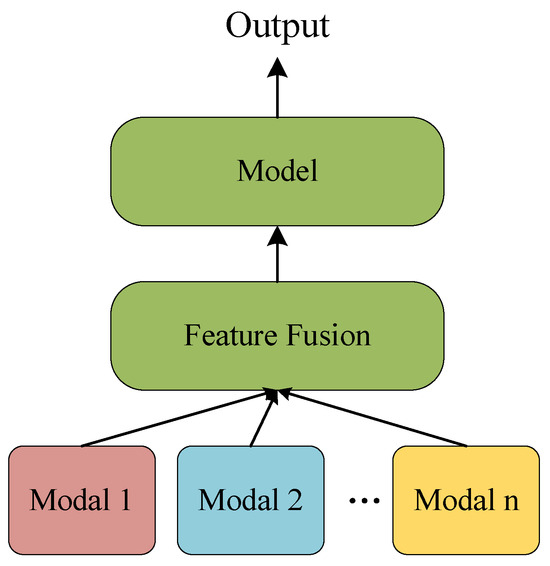

Early fusion is a simple and direct method of multimodal feature fusion. Its core idea is to directly integrate information from different modalities at the input level to form a comprehensive feature representation. In practice, this is often achieved in straightforward ways, such as concatenating feature vectors from different modalities, weighted summation, or using other forms of integration methods.

The principle of early fusion lies in unifying multimodal data in the feature space to construct a comprehensive model input. Through merging information from different modalities at the input level, early fusion allows the model to directly access information from multiple data sources without additional processing steps. This direct fusion simplifies the design and implementation of the model, reduces system complexity, and enables rapid integration of multimodal information. The schematic diagram of early fusion is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Early fusion diagram.

However, early fusion also has some limitations, with the most significant being the potential for information confusion or conflict between different modalities. Because features from different modalities have different representations and semantic information, direct concatenation may lead to the loss or distortion of some information. Therefore, in practice, it is important to carefully select appropriate fusion methods to fully utilize the information from different modalities and improve the performance and effectiveness of the model.

2.1.2. Late fusion

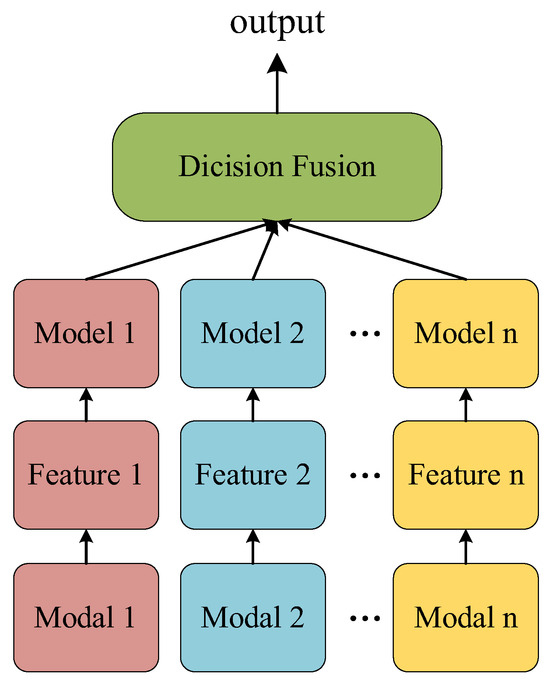

Late fusion is a method where each modality is processed independently before fusion. In late fusion, each modality undergoes separate deep processing, for example, using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image processing and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for text processing, and their output features are then fused together.

The principle of late fusion lies in fully exploring the feature information within each modality and modeling it through independent processing. Through processing each modality separately, late fusion can better preserve the specific information of each modality, thereby improving the model’s expressive power and generalization performance. Additionally, late fusion can also flexibly perform inter-modal information interaction, thus better capturing the correlation and semantic association between modalities.

However, late fusion also presents some challenges, with the most significant being increased computational costs and model complexity. Since each modality requires independently designed and trained specialized models, this may result in higher computational and storage overheads. Therefore, in practice, it is necessary to carefully design the model structure to balance performance and complexity and fully utilize existing computational resources. The schematic diagram of late fusion is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Late fusion diagram.

Furthermore, to optimize late fusion, researchers are also exploring more efficient feature fusion techniques, such as learning-based fusion layers or adaptive fusion mechanisms. These methods may further improve the efficiency and accuracy of models. Such advancements ensure that late fusion maintains broad application prospects when dealing with complex multimodal data.

2.1.3. Hybrid Fusion

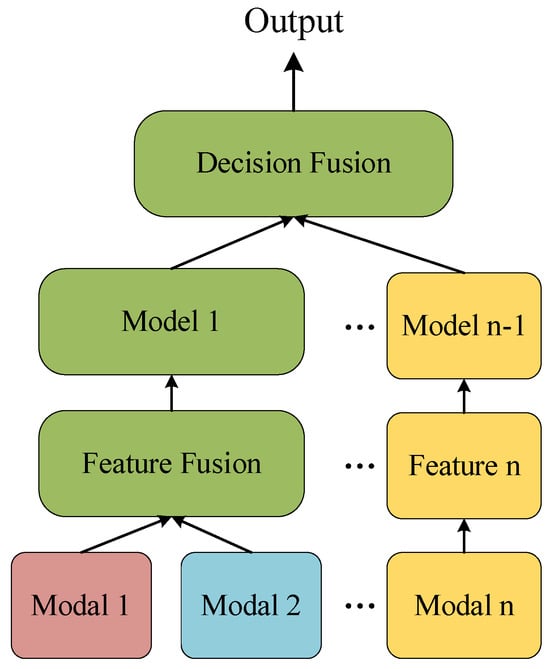

The method of hybrid fusion combines the advantages of both early and late fusion, retaining the simplicity and directness of early fusion while enabling deep processing when necessary. In hybrid fusion, certain modalities may undergo simple fusion at an early stage, while others undergo deeper processing, and their features are then fused together at a later stage.

The principle of hybrid fusion lies in flexibly selecting fusion strategies based on the specific task requirements and the relationship between modalities. Through early-stage simple fusion, multimodal information can be quickly integrated, reducing model complexity. Meanwhile, in the late fusion stage, the advantages of deep processing can be utilized to better explore the correlations and interactions between modalities, thereby improving the model’s performance and effectiveness.

The advantage of hybrid fusion lies in its ability to flexibly select fusion strategies based on specific task requirements and the relationships between modalities. This flexibility allows the hybrid fusion method to adapt to different application scenarios and achieve good results in various multimodal learning tasks. At the same time, hybrid fusion can fully utilize the advantages of both early and late fusion, thereby retaining simplicity and directness while enhancing the model’s expressive power and generalization performance. The schematic diagram of hybrid fusion is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Hybrid fusion diagram.

2.2. Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanism, as an important neural network technology, was inspired by the human visual and cognitive systems. Its earliest proposal can be traced back to the field of cognitive psychology in the 1980s. However, the application of attention mechanisms in the field of deep learning began in recent years. Early work laid the foundation for the introduction of attention mechanisms into neural networks. These studies introduced attention mechanisms into autoencoders and neural machine translation models, demonstrating their potential in improving model performance and generalization ability.

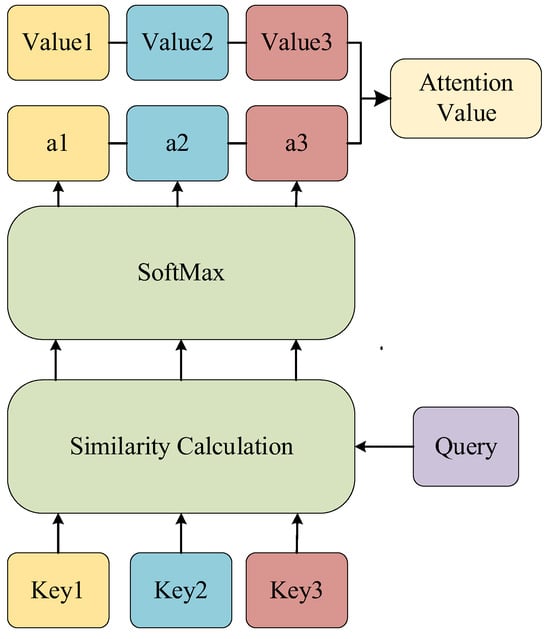

The attention mechanism achieves targeted focus and weight allocation of information through a mechanism called Query–Attention–Key. The core concept of this mechanism is to compute the relevance between a query and a set of keys and use this relevance to determine the weight distribution of the final output values. The computation process of the attention mechanism is illustrated in Figure 4. Specifically, it first computes the relevance between the query and each key using some calculation method (e.g., dot product). Then, it uses some normalization function (e.g., softmax function) to transform these relevances into a weight distribution, ensuring that the sum of all weights is 1. Finally, it uses these weight allocations to aggregate all values, generating the final output result.

Figure 4.

The computational process diagram of the attention mechanism.

The specific calculation methods as shown in Formulas (1) to (3):

The attention mechanism plays a crucial role in multimodal feature fusion, effectively capturing the correlations between different modalities and dynamically adjusting the features’ weights to enhance the model’s performance and expressive power. Introducing the attention mechanism into modal fusion allows the model to flexibly focus on essential information from different modalities, achieving more precise fusion. The attention mechanism enables the model to dynamically learn the weights of each feature when processing each modality and adjust the fusion weights based on their importance, making significant features more prominent and suppressing less relevant ones. This dynamic adjustment mechanism enhances the model’s flexibility and generalization ability. For instance, consider a multimodal task involving vision and text. In early fusion, the feature vectors of vision and text can be concatenated, and the attention mechanism dynamically adjusts the weights of different modal features to reflect their importance in the task. In late fusion, after each modality undergoes independent processing, the attention mechanism is used to fuse different modal features to better capture inter-modal correlations. In practical applications, attention mechanisms can be implemented in various ways, such as fully connected layers, convolutional layers, or self-attention mechanisms. Self-attention mechanisms are particularly effective as they consider the relationships between different positions in the input sequence, better capturing long-distance dependencies within the sequence. This mechanism has achieved significant success in fields like natural language processing and computer vision and has been widely applied in multimodal learning tasks.

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Architecture

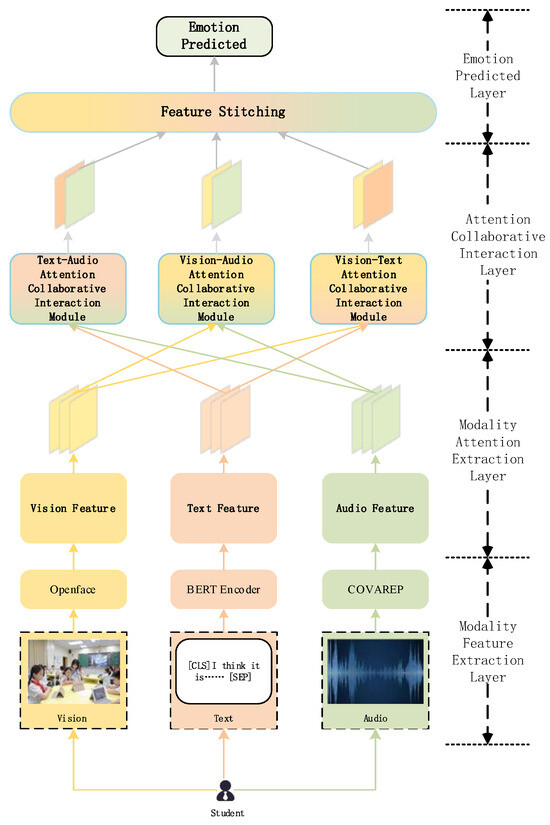

The overall architecture of the collaborative perception model based on attention mechanism is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

ACAM architecture diagram.

This model mainly consists of four core components:

The first part is the modality feature extraction layer, which extracts key information from different input modalities such as text, video, and audio, laying the foundation for subsequent processing;

The second part is the modality attention extraction module, which utilizes multi-head attention mechanisms to delve into the complex relationships within each modality, enhancing the model’s understanding of specific modality features;

The third part is the cross-modal attention collaborative interaction layer, which achieves complementary and integrated information exchange between different modalities through cross-modal collaborative analysis, facilitating the model to capture richer cross-modal interaction information;

The fourth part is the emotion prediction layer, which uses multilayer perceptrons to comprehensively judge and make decisions based on the information processed in the previous three parts, outputting the final model prediction results. This module not only integrates features from various modalities but also optimizes the flow and processing of information, ensuring high-quality and accurate model outputs.

3.2. Modality Feature Extraction Module

This article employs three main tools and techniques to extract feature vectors from different modalities: the BERT pre-processing model, COVAREP, and OpenFace, used for extracting features from text, audio, and visual modalities, respectively.

Firstly, the model utilized the BERT pre-processing model for word embedding. The BERT (bidirectional encoder representations from transformers) model is a leading pre-trained language-representation model, involving multiple key steps in the word-embedding process. After processing through the BERT structure, we obtained feature vectors for the entire text and for each word. These feature vectors encapsulated contextual information within the text and were directly used as inputs for subsequent downstream tasks. Additionally, the pre-trained BERT model itself possesses powerful capabilities for learning contextual information, which were embedded into our model as an upstream structure and to dynamically adjust word embeddings during model training.

Next, for audio modality data, this model utilized COVAREP [10] for feature extraction. COVAREP is a tool used to extract speech features, primarily including fundamental frequency, voice intensity, and spectral envelope, among other basic acoustic parameters. In the experiments with this model, the audio signal was framed in frames of 20 milliseconds, and acoustic parameters were extracted, including fundamental frequency in the range of 50 Hz to 400 Hz and voice intensity between 40 and 90 dB. Additionally, spectral analysis was conducted to capture the energy distribution of the audio signal at different frequencies.

Finally, for visual modality data, this model employed OpenFace [11] for feature extraction. OpenFace is a tool used for facial expression recognition and facial feature extraction, capable of extracting facial expressions, actions, geometric features, and other information from images or videos. In the processing of visual modality, the images were first processed and face detection was performed, then OpenFace was used to extract facial features. OpenFace utilizes deep learning techniques such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), residual networks (ResNet), etc. Through these deep learning models, OpenFace efficiently identified facial regions and extracted rich facial features. These features included facial expressions, facial actions, facial geometric features, etc., providing important visual information for the multimodal model.

3.3. Modality Attention Extraction Module

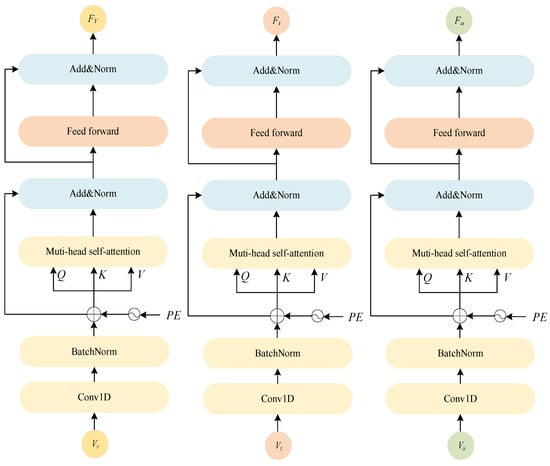

An attention mechanism can be utilized to enhance a model’s focus on important parts of a time series. For instance, in a long video sequence, the model may only need to focus on a few key frames to determine the overall sentiment, while ignoring irrelevant or low-information parts. The application of attention mechanisms helps the model more accurately integrate information from different modalities such as visual, textual, and auditory, thereby improving performance. Through learning the correlations and importance between modalities, the model optimizes the use of multimodal information for decision making and prediction. Next, the principle of the module relying on the attention mechanism for feature extraction is introduced, as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Modality attention extraction module structure diagram.

Firstly, through the aforementioned classroom streaming-media feature extraction module, we obtained three feature vectors with different dimensions. These feature vectors represented different modalities of information, namely textual, visual, and auditory information. In order to achieve dimensionality uniformity and facilitate subsequent processing, we input these feature vectors into one-dimensional convolutional layers and batched normalization layers to stabilize the feature distribution. Finally, we obtained three-dimensionally consistent feature representations, which we respectively named as textual features , visual features and auditory features . After obtaining standardized feature representations, the formula is as follows, where U represents the unprocessed feature vector, , K corresponds to the convolution kernel size for each modality. The specific formulas are as shown in Equations (4) and (5):

Next, we calculated positional embeddings for each position index in the sequence. Assuming the specific process followed Equations (4)–(6), the next step involved extracting self-attention mechanisms between the features of different modalities. This study utilized the superior performance of sine-based positional embedding functions as the positional encoding mechanism in the sequence model:

Taking textual features as an example, assuming that after being processed by a linear layer, the textual feature is a matrix of dimension , firstly, we mapped the input feature vectors through linear transformations to obtain query (), key (), and value () vectors. This mapping process was controlled by three weight matrices , , , which respectively acted on the input feature vectors to yield query vectors Q, key vectors K, and value vectors V. Through training, the neural network adjusted these weight matrices so that the model could better capture the correlations and importance between input features.

The specific mathematical expressions are shown in Equations (7)–(9), where there are weight matrices for learnable linear mappings :

Next, we input the query (), key (), and value () vectors into a multi-head self-attention mechanism. This mechanism aggregated information via computing attention weights. The multi-head mechanism enabled the model to learn different feature representations because each head learned different attention weights. Finally, we linearly transformed and concatenated the results from multiple heads using an output weight matrix , which served as the output of the multi-head attention mechanism. The specific formulas were as follows; here, are the weight matrices for learned linear mappings, is the weight matrix for the output linear mapping, and the concat operation concatenates the results of each head before applying the output linear transformation:

After obtaining the output of the multi-head attention mechanism, we added it to the input feature vectors and then applied layer normalization to the result. This step promoted stable training of the network and prevented gradient vanishing or explosion. Next, the output of the added and normalized layer was subjected to convolutional operations, resulting in the convolutional layer output . This step aided in further feature extraction and introduced local correlations to better capture structural information from the input feature vectors. Here, we utilized the ReLU function as the activation function to introduce non-linearity. The formula is depicted in Equation (12), where represents the weight parameters of the convolutional layer:

Finally, the features were further adjusted and normalized through the added and normalized layer once more to facilitate model training and performance improvement. This resulted in obtaining a textual feature representation processed through the self-attention mechanism. The formula is depicted in Equation (13):

Based on the same operations, we obtained and .

3.4. Cross-Modal Attention Cooperative Interaction Module

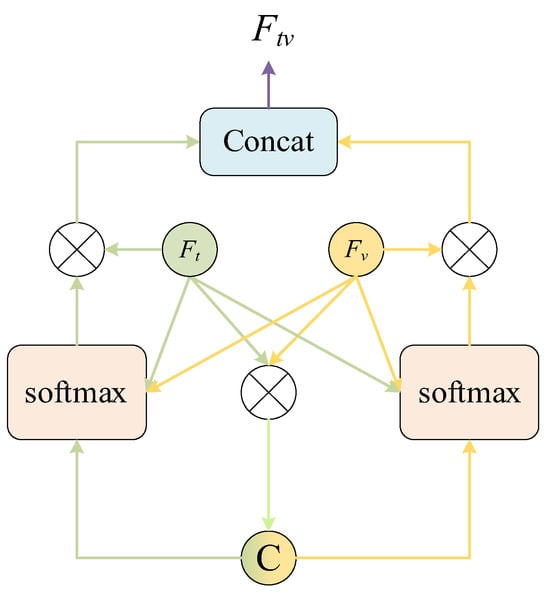

The cross-modal self-attention interaction learning module is a key component aimed at effectively integrating multimodal information. Through modality interaction encoders, feature vectors from each modality are encoded to extract modality-specific information and weighted through self-attention mechanisms to highlight key information within each modality. This interactive learning strategy enables modalities to learn from each other, acquiring richer contextual information. This module not only integrates information from multimodal data but also enhances the correlations between modalities, thereby improving the model’s performance and generalization capabilities.

Let us denote the text modality and the visual modality . The attention cooperative interaction module is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Collaborative attention interaction module schematic diagram.

Firstly, we computed the correlation between features from the two different modalities. We applied linear transformations to and using weight matrices and respectively, and then calculated their transpose multiplication to obtain the interaction matrix .

Then, we combined the text and visual features using the hyperbolic tangent function to obtain bidirectional attention weights. This step helped capture the complex relationships between text and visual features. The specific formulas were from Equations (14)–(16), where , , , are learnable weight matrices:

Then, we normalized the bidirectional attention weights for text and visual features using the softmax function to obtain attention weights and . This step allowed the network to focus attention on important feature information, thus improving feature representation. The specific formulas are shown in Equations (17) and (18), where , is a learnable weight matrix.

During the feature weighting stage, the model used attention weights to weight the text and visual features, obtaining the final weighted feature representations. Through applying attention weights and to the text features and visual features , respectively, the model obtained the corresponding weighted feature vectors and .These weighted feature vectors can be seen as projections of text and image in a common semantic space, reflecting the model’s understanding and expression of semantic information from text and images. Finally, the two feature vectors were concatenated to obtain the bimodal attention interaction feature vector . The specific formulas were from Equations (19)–(21):

Based on the same operations, we obtained two more feature vectors and .

3.5. Emotion Prediction Module

The emotion prediction module has been designed to integrate multimodal information, fully exploit the correlations between different modalities, and achieve precise prediction of emotional information using deep learning methods. This module concatenates the cross-modal feature vectors extracted via the cross-modal cooperative attention interaction module and feeds them into a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for processing. The MLP, as a deep neural network model, is capable of nonlinear mapping and modeling complex relationships within input features, thereby better capturing the inherent patterns and semantic information among features.

After the attention processing across the three modalities described above, we obtained interaction feature vectors for each modality. These feature vectors were then fused through a tanh-activated MLP after being concatenated, ultimately yielding the predicted value , as shown in Equation (22):

The model utilizes mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. MSE is a method to measure the difference between predicted values and true values via computing the squared difference between predicted values and true values to evaluate the model’s performance. Its formula is shown as Equation (23):

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Environment

The experiments reported in this paper were mainly encoded in a Python 3.8, Pytorch 1.7.1, CUDNN 8.0.5, Cuda 11.1 environment and trained on a computer with Intel-i5-9600k CPU (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), RTX 3070 graphics card (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 32 g memory.

The model employed the dropout technique, where each neuron had a 10% probability of being randomly dropped out, helping to reduce the risk of overfitting. The batch size during training was set to 32, balancing training speed and memory utilization. The model underwent 180 epochs of training, with each epoch representing a complete traversal of the entire training dataset. We chose the AdamW optimizer to optimize model parameters, incorporating weight decay regularization. The learning rate was set to 1 × 10−4, controlling the step size of the model’s parameter updates to accelerate convergence. Additionally, we applied regularization with a weight decay rate of 1 × 10−2 to penalize the size of model parameters and prevent overfitting. These comprehensive parameter settings aimed to ensure the model had good generalization performance and efficient training. The specific model parameter settings are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

ACAM Parameter Configuration.

4.2. Dataset

The data in this study were primarily built upon the publicly available dataset CMU-MOSI. The CMU-MOSI dataset was collected by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and aims to provide benchmark data for tasks such as emotion recognition, sentiment analysis, and multimodal emotion analysis. It consists of video, audio, and text data, with over 93 h of video data, 39 speakers, 23,453 sentences, and approximately ten million words. The emotional labels in the dataset are based on the VA affective model dimensions, namely valence, arousal, and dominance. Additionally, the dataset includes audio and text features to support multimodal emotion-analysis tasks. This dataset has been widely used in research on emotion recognition, sentiment analysis, and multimodal emotion analysis, making it a valuable resource.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

This model’s output can be used for both classification and regression tasks. It categorizes cross-modal emotional expressions into predefined emotion categories while also quantifying the intensity or subtle differences in emotions to adapt to various application scenarios and analytical needs. Therefore, this research adopted evaluation metrics for both regression and classification tasks to comprehensively assess the model’s performance, including mean absolute error (MAE), correlation (Corr), accuracy (Acc), and F1 score, represented by the following formulas:

MAE (mean absolute error) is one of the metrics used to evaluate the accuracy of prediction models. It measures the predictive performance of a model through calculating the average of the absolute errors between predicted values and true values. Here, represents the absolute difference between the true values and the predicted values, and n represents the number of samples:

Correlation (Corr) measures the degree of association between the true values of data labels and the values predicted with the model. Here, represents the true values of data labels, and represents the predicted values of data labels.

Accuracy (Acc) represents the proportion of samples correctly predicted by the classifier out of the total sample size and is a key metric for evaluating the accuracy of classification models. In this context, TP denotes the number of true positives, TN denotes the number of true negatives, FP denotes the number of false positives, and FN denotes the number of false negatives. High accuracy implies that the model has a high level of accuracy in classifying the data.

The F1 score combines a model’s precision and recall, where precision represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples out of all samples predicted as positive, and recall represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples out of all actual positive samples.

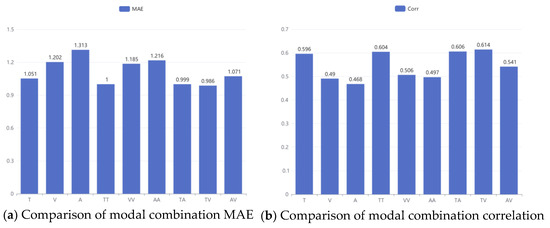

4.4. Module Ablation Experiments

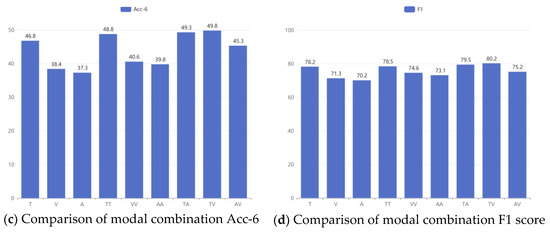

In this study, a series of modality ablation experiments were designed to evaluate the impact of different modalities and their fusion methods on the model’s prediction performance. In the experimental setup, the symbols T, V, and A represent scenarios where predictions were made using a single modality (text, visual, audio), respectively. Correspondingly, symbols TT, VV, AA indicate scenarios where self-attention mechanisms were applied to each modality to enhance the model’s processing capability for single-modality information, followed by predictions.

Additionally, this section also explores the complementarity between modalities, denoted by TA, TV, and VA, representing scenarios where two different types of modality data were fused through a cooperative attention module before predictions were made. Subsequently, the mean absolute error (MAE), correlation (Corr), accuracy (Acc), and F1 score were tested for each of nine scenarios. The specific experimental results are displayed in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Modality ablation experiment results.

Based on the experimental data, we can draw three conclusions:

(1) Comparing the single modalities (T, V, A) with their counterparts enhanced through attention mechanisms (TT, VV, AA), it was observed that the attention mechanism effectively improved the model’s performance across all three modalities of text, visual, and audio. For instance, in the text modality, the enhancement with attention mechanism (TT) reduced MAE from 1.051 to 0.1 and increased the F1 score from 78.2 to 78.5, indicating that the attention mechanism more effectively captured important features and complex relationships within each modality;

(2) When comparing the combined modalities (TA, TV, AV) with single modalities and their enhanced counterparts, we observed that the cooperative attention module further improved performance. Particularly in the text–audio (TA) and text–visual (TV) combinations, MAE, correlation (Corr), Acc-6, and F1 scores were all superior to the single modality T and the enhanced modality TT. This reflects the effectiveness of the cooperative attention module in integrating different modality information and extracting richer and complementary features;

(3) The superiority of the text modality was evident in the data, particularly in several key performance indicators. The text modality had an MAE of 1.051 and an F1 score of 78.2, whereas the visual and audio modalities had MAE values of 1.502 and 1.313, respectively, and F1 scores of 71.3 and 70.2. The research results indicated that in emotion-recognition tasks, the text modality provided more accurate and relevant predictions.

This is primarily because text data contains rich semantic and syntactic information, which are important factors for accurately capturing and understanding emotions. The richness of text enables the model to deeply analyze and interpret emotional states, which is often not achievable in visual or audio modalities. In the field of natural language processing, a significant amount of research and technological advancements have focused on how to extract features from text, such as word embeddings, contextual embedding techniques, and pre-trained models like BERT in particular. Due to their ability to capture deep semantic relationships, text feature extraction has become more efficient with models like BERT.

Additionally, in classroom streaming datasets, audio quality may be affected by background noise, student whispers, or speakers being too far from the microphone, resulting in unclear audio. Moreover, there may be modalities missing due to students not speaking during streaming sessions. Also, visual information may lose critical non-verbal cues due to scene restrictions or occlusion. In contrast, text data tends to be more complete due to collaborative organization through online teaching platforms and speech recognition. This explains why the performance of the text modality outperformed other modalities in modal ablation experiments.

4.5. Network Comparison Experiment

In this section, in order to evaluate the performance of the model proposed in this paper, it is compared with the evaluation indexes of the algorithm models ResNet50 [12], BERT [13], LMF [14], TFN [15], MFN [16], MulT [17] and GMFN [18].The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the Network Comparison Experiment.

Firstly, the ResNet50 and BERT models, which utilized only the visual and text modalities, lacked deep fusion and complementary information between modalities. This limitation restricted their performance in complex tasks compared with multimodal models that can comprehensively leverage multiple sources of information.

Although LMF simplifies computation through reducing the rank of modality features, its ability to handle complex relationships is limited, as evidenced by its unsatisfactory performance on Mae and Corr metrics. TFN, using higher-order tensors to simulate complex interactions between modalities, exhibited improved performance, but its high computational complexity restricts its practical application range. GMFN, which introduces graph structures to capture dynamic relationships between modalities, showed better performance, but its reliance on graph structures increases the model’s design complexity. MFN attempts to integrate different modalities through adaptive learning, achieving relatively good results, but it still fell short in handling nonlinear complex relationships. MulT utilizes cross-attention mechanisms to handle text, visual, and auditory modalities, achieving significant progress with multiple metrics, yet its understanding of long-term dependencies and deep interactions between modalities remains limited. The MISA model achieved higher performance through reinforcing intra-modal and cross-modal self-attention mechanisms, achieving finer information fusion, but there was still room for improvement in capturing and utilizing modality-specific information.

From Table 2, it is evident that the ACAM model outperformed the aforementioned models on several key performance metrics. Its Mae was lower and Corr was higher compared with competitors. Additionally, the Acc-6 and F1 scores reached 49.9% and 80.5%, respectively, demonstrating its significant advantages in multimodal fusion for classroom assessment tasks. This performance improvement not only reflects the progress of ACAM in modal fusion accuracy but also underscores its efficient capability in understanding and utilizing multimodal information.

5. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence-assisted education has brought great possibilities to educational teaching. In the past, learner assessment often relied on exam scores, homework assignments, etc. However, the emergence of artificial intelligence enables learner assessment based on comprehensive learning process data, forming learner profiles that fully showcase students’ emotions, attention, and cognitive states. This study conducted collaborative analysis based on learners’ multimodal data to explore their potential emotional states, thereby providing assistance for personalized teaching guidance.

This paper proposes a collaborative perception model based on attention mechanism, which innovatively achieves effective fusion of multimodal data, fully considering the complementarity between modalities and enhancing the model’s dynamic adaptation to different modal information. Experimental results demonstrated that the model outperformed traditional methods in emotion recognition, exhibiting high accuracy and robustness in practical applications.

However, from the perspective of optimizing modal alignment, although the model proposed in this study effectively integrates multimodal data, it is difficult to ensure accurate matching and synchronization of information between different modalities; i.e., the problem of modal alignment remains a major challenge. Future work can deepen modal alignment technology, such as using advanced time-alignment algorithms to process asynchronous data, or using deep learning algorithms to automatically identify and synchronize the correlation between different modalities, in order to improve the accuracy and efficiency of emotion recognition.

Author Contributions

Methodology, W.W., J.Z. and X.S.; Data curation, X.S.; Writing—original draft, W.W.; Supervision, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangdong Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of China grant number [GD23YJY08] and by National Natural Science Foundation of China [62237001].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wei, Q.; Sun, B.; He, J.; Yu, L. BNU-LSVED 2.0: Spontaneous multimodal student affect database with multi-dimensional labels. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2017, 59, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, Z.; Alnajjar, F.; Parambil, M.M.A.; Gochoo, M.; Ali, L. Real-Time Attention Monitoring System for Classroom: A Deep Learning Approach for Student’s Behavior Recognition. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Lu, Z.; Shang, L.; Li, H. Multimodal convolutional neural networks for matching image and sentence. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Washington, DC, USA, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Bajpai, R.; Hussain, A. A review of affective computing: From unimodal analysis to multimodal fusion. Inf. Fusion. 2017, 37, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, M.; Rothkrantz, L. Facial Action Recognition for Facial Expression Analysis From Static Face Images. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part B 2004, 34, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashyal, S.; Venayagamoorthy, G. Recognition of Facial Expression Using Gabor Wavelets and Learning Vector Quantization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2008, 21, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, Y.; Kim, D. Natural Facial Expression Recognition Using Differential-AAM and Manifold Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2009, 42, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.F.; Gong, S.G.; Peter, W. A Comprehensive Empirical Study on Linear Subspace Methods for Facial Expression Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshop, Washington, DC, USA, 17–22 June 2006; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, P.; Wang, T. A review of multimodal sentiment analysis. J. Commun. Univ. China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 29, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, M. Research on emotion recognition methods based on audio and video. Signal Process. 2021, 37, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Degottex, G.; Kane, J.; Drugman, T.; Raitio, T.; Scherer, S. COVAREP—A collaborative voice analysis repository for speech technologies. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Florence, Italy, 4–9 May 2014; pp. 960–964. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Robinson, P.; Morency, L.P. OpenFace: An open source facial behavior analysis toolkit. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Placid, NY, USA, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, S.; Okur, E.; Kumar, S.H.; Nachman, L. Low rank fusion based transformers for multimodal sequences. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; p. 2934. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; pp. 1103–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Mazumder, N.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Memory fusion network for multi-view sequential learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 5634–5641. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P.P.; Kolter, J.Z.; Morency, L.-P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2 2019; pp. 6558–6569. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).