Abstract

Robotic process automation (RPA)* based on the use of software robots has proven to be one of the most demanded technologies to emerge in recent years used for automating daily IT routines in many sectors, such as banking and finance. As with any new technology, RPA has a number of potential cyber security weaknesses, caused either by fundamental logical mistakes in the approach or by cyber-human mistakes made during the implementation, configuration, and operation phases. It is important to have an extensive understanding of the related risks before RPA integration into enterprise IT infrastructure. The main asset operated by RPA is confidential enterprise data. Data leakage and theft are the two main threats. The wide application of RPA technology in information security-sensitive sectors makes the protection of RPA against cyber-attacks an important task. Still, this topic is not yet adequately investigated in the scientific press and existing articles mainly concentrate on stating the RPA security importance and describing some threats. In this article, we present a flexible tool, security-oriented ontology OntoSecRPA*, which systematically describes RPA-specific assets, risks, security, threats, vulnerabilities, and countermeasures. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no ontologies available that are specific to the RPA domain, and existing security ontologies lack RPA-related features. In the future, the proposed ontology can be updated and used in different ways, for example, as a checklist for risk management tasks in RPA solutions and a source of information for an expert system or a concentrated domain-specific source of information, which indicates its wide practical application. The proposed ontology was formally verified by applying ontology completeness assessment and used for risk assessment in a sample scenario.

1. Introduction

Robotic process automation (RPA) is a family of business process automation technologies based on the use of software robots and artificial intelligence. The software robot reproduces human actions by interacting with the interfaces of information systems. The scenario of its behavior is programmed by the developer based on observing a real user performing a task using computer technology. It is assumed that the introduction of RPA robots shortly will free up a significant number of company personnel engaged in routine information processing. The use of technologies allows reducing the number of employees performing routine work, increases the speed of business processes, reduces the cost of operating the company, allows performing business processes at any time of the day, reduces the number of mistakes made by people and increase the volume of information processed. Nowadays, RPA continues to develop in the IT industry market. Global RPA software end-user spending is projected to reach $2.9 billion in 2022, an increase of 19.5% from 2021, according to the latest forecast from Gartner, Inc. [1] (Table 1). The global robotic process automation market size is expected to grow from USD 10.01 billion in 2022 to USD 43.52 billion by 2029 at a CAGR of 23.4% [2].

Table 1.

Report Garntner2022, August. Worldwide RPA Software End-User Spending Forecast (Millions of U.S. Dollars).

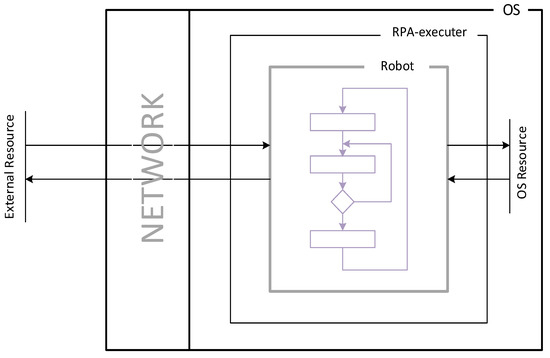

The general concept of software robot functioning is presented in Figure 1. Usually, a robot can be considered as a looped sequence of steps, each of which runs a specific program, usually using the results of previous steps and, in turn, generating data for the next, which is shown in the center of Figure 1. In the course of their work, they can generate reports, use the local computer’s file system, and interact with external computer systems—OS Recourses and other External Recourses (mail servers, database servers, internet services, cloud systems, and enterprise automated systems). All the program code running within the robot can be divided into three groups: built-in, standard (utilities), and user-defined. These programs use the resources of the local operating system (file system, RAM, CPU time). The local computer interacts with external computer systems (mail servers, database servers, Internet services, cloud systems, automated enterprise systems). Embedded programs are usually part of an application that is labeled as an RPA- executer. The main purpose of the RPA-executer application is to start and stop the robot. The utilities are provided as part of the robot’s software and are designed to perform standard actions: text recognition, sending and receiving emails, filling in templates, forms, and so on. Usually, the robot developer embeds a call to the utilities in the robot’s execution cycle. In the drawing, the execution cycle is indicated by an internal contour with the Robot label.

Figure 1.

RPA application Architecture.

User programs are used if the functionality of the built-in and standard software does not cover the necessary functionality of the robot being developed. The development of such programs is based on the standards and interfaces (APIs)* described in the RPA system documentation. User code, similar to utilities, functions as part of the work execution cycle. As a rule, only linear processes can be robotized, in which limited decision-making variability is applied, and algorithms for robot interaction with its environment are strictly deterministic. The main advantages and disadvantages of RPA are listed in Table 2:

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of the RPA.

While limitations related to primitiveness and linear applicability can be seen as innate for the RPA approach, the information security risks need to be mitigated. Management of security risks should be a top-priority issue while developing RPA solutions since security becomes fundamental in our society and the survival of organizations depends on the correct management of up-to-date security elements [3]. The high number of information security risks in RPA solutions can be explained by a high number of communicating components and channels, utilizing different communication protocols (including plaintext) for transmitting sensitive authentication data or having known security flaws, thus giving numerous possibilities for sniffing, MITM*, spoofing and other attacks. The most ardent problem is to ensure that confidential data is not misused via the privileges attributed to software robots or those that develop the workflows for the robots. The issue of data security can be broken down into two highly interconnected points one being data security and the other access security. This ensures that the data being accessed and processed by the robot remains confidential and is based on the ‘least privilege’ security principle. Moreover, these robots have elevated permissions to perform tasks and access passwords. Access management of these robots must be properly assigned and reviewed similar to reviewing and managing service accounts [3].

A systematic approach to the mitigation of the risks in any area assumes that risk assessment in scope should be conducted in order to determine what might happen and cause potential damage and to gain an understanding of how, where, and why that damage might occur. The risks should be taken into account, regardless of whether the source of these risks is under the control of the organization or not. Assessment typically includes identification of assets, identification of threats, identification of controls and protection measures, identification of vulnerabilities (not only in software or hardware) that can be exploited by current threats, and identification of the consequences of the implementation of threats. As this process should be conducted regularly and in the case of every new RPA deployment there is a need for a tool, that could help in performing all these assessment steps. While traditionally checklists of threats and vulnerabilities are used, we propose systemizing the related knowledge and concepts in a more flexible ontology format.

An ontology defines the basic terms and relations compromising the vocabulary of a topic area as well as the rules for combining terms and relations to define extensions to the vocabulary [4]. The ontology provides better communication, reusability, and organization of knowledge by decreasing language ambiguity and structuring transferred data [5]. In addition, ontologies can be used as a knowledge base for expert systems, for risk analysis, and to extend existing security ontologies. As the security area is very broad and has many relations between its concepts, the usage of security ontology could improve security knowledge description unambiguity in information systems. The necessity of security ontology can be noticed in various security communities and is considered an important challenge and a research branch [5]. In addition, the advantage of using ontologies is the ability to analyze, accumulate and reuse knowledge about the subject area obtained from different sources. To our knowledge currently, there are no available RPA domain-specific ontologies, while existing security ontologies lack RPA-related features. However, similar to other approaches to the systematization of knowledge, the ontological approach has a number of shortcomings. However, the ontological approach used in describing a narrow subject area—RPA security, cannot be an unchanging fundamental systematized base. Since the set of assets, their security, and vulnerabilities may change and differ based on the practical experience of the researcher and vendor in software robotics.

In the article “Ontology-Based Metrics Computation for System Security Assurance Evaluation” [6], the author presents a study on the topic “Ontologies in security assurance”. So, Wang and Guo propose an ontology-based approach to analyzing and assessing the security posture of software products. It provides quantitative measurements for a software product based on an ontology built for vulnerability management, called OVM*. Users can query the OVM to infer similar products and collect the related vulnerability information for each product. For generating an overall score, they propose an algorithm based on the CVSS metrics of the vulnerabilities inside the software. Gao et al. proposed an ontology-based framework for assessing the security of network and computer systems from the attacker’s perspective. The proposed taxonomy consists of five dimensions, which include attack impact, attack vector, the target of attacks, vulnerability, and defense.

Moreover, in the context of the cloud system assessment, Koinig et al. established a knowledge-based ontology (Contrology) for capturing the knowledge required to audit a cloud computing environment. Their work is based on the ontology proposed by Fenz and Ekelhart, which consists of six classes: assets, controls, security attributes, security recommendations, threats, and vulnerabilities. Likewise, Maroc and Zhang developed an ontology (CS-CASEOnto) for cloud services security evaluation, which covered necessary security knowledge and relevant cloud concepts of significance to security measurement.

In addition, several ontologies are proposed in the scientific community for assessing security in certain areas or contexts. For example, in the field of the Internet of Things (IoT), González-Gil et al. proposed a context-based security assessment ontology (IoTSecEv) to describe the different security preferences of IoT device end users based on concerns and interests in various security elements such as threats, vulnerabilities, security mechanisms or functions. In this regard, it is possible to evaluate security from a contextual perspective, in which the various interests and concerns of users are properly taken into account.

However, security ontologies in the field of RPA were not found, which made it possible to consider this important niche empty.

The ontology is based on six classes: assets, risks, security, threats, vulnerabilities, and countermeasures, identified as the most important, which formed the basis of the ontology of security developed for RPA. The top-down domain analysis approach was used when building the ontology, expanding and supplementing the presented classes, instances, subclasses, and properties.

In this article, we present the proposed security ontology for RPA (OntoSecRPA) which systematically describes RPA-specific assets, risks, security, threats, vulnerabilities, and countermeasures.

Later the proposed ontology can be updated and used in different ways, such as a checklist for risk management tasks in RPA solutions and a source of information for an expert system or concentrated domain-specific source of information. The proposed ontology is formally verified by applying the ontograph assessment method. In order to evaluate the ontology, two types of assessment methods were chosen: Formal Ontology Verification [7,8,9,10,11] and Experimental Ontology Verification, presented in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 respectively. The risk analysis was carried out on the basis of the general requirements of the ISO 27005 standard.

All acronyms used in this article are collected in the table of acronyms (Table 3). The acronyms collected in the table in the text are marked with an asterisk*.

Table 3.

Table of acronyms.

2. Related Work

The development of domain-specific security ontology requires an understanding of current and prospective threats, as well as existing security ontologies. “An ontology is a formal and explicit specification of a shared conceptualization” [12]. One of the first known security ontologies was by Schumacher [13]. Later similar approach was applied by Tsoumas and Gritzalis [14]. Currently, a number of security-related ontologies were developed, such as more than 400 times higher (572,311 records for “security”, compared to 2663 records for “cyber ontology” or “security ontology”) of publications on security ontology-related topics in the Web of Science Core Collection is constantly increasing. This indicates that the security ontology topic has been analyzed in scientific papers with the same growth as security in general [15].

Still, it is necessary to say, that currently no RPA security-related ontologies were found. Based on that the related work review is mainly concentrated on the main RPA threats, identified in the scientific literature.

When considering the main groups of RPA-related threats, the following types can be distinguished as the most important ones [16]:

Vulnerabilities are flaws in the information system that enable attackers to gain access to the system to perform illegal actions. Most RPA systems today use data encryption, which reduces the risk of vulnerabilities, but they are still found in some relatively weakly secured solutions. For example:

- A security vulnerability could exist in the virtual machine environment, which is the environment where the Bot runs. Automation Anywhere Bots are deployed in 27 Microsoft VM Windows server 2012 R2 and if there is a security vulnerability in the virtual machine environment, the attacker could access the VM* remotely and possibly access sensitive data [17];

- Bot developers could program the Bot to send/receive sensitive data without encryption. This data is vulnerable and could be exploited by an attacker.

Internet Abuse. The use of company information security data. According to statistics, more than 70% of data leaks occur due to the fact that people with accounts with increased access give them to someone for personal gain. If a robot has privileges, attackers can use it to compromise the system and misuse information. For example:

- An attacker may be able to compromise an administrator account used by the Bot. An attacker could use the admin account to gain access to sensitive data;

- Before leaving employment, a former employee could program the Bot to delete important data and interrupt the business process.

System failure. A hardware or software malfunction may cause the system to stop functioning. Downtime is most often associated with the human factor (employee errors), the state of the equipment, errors on the server, and problems of interaction between software solutions. A network failure can disrupt the robot, similar to other software solution, and result in poor performance. Interruptions in the system or even shutdown can cause an overload caused by an excessively fast sequence of actions of the robot with the system not ready. For example:

- Some bad programming practices could make the Bot consume all of the virtual machine system resources and cause the virtual machine to become unresponsive and therefore unable to perform any work;

- A virtual machine could be affected by unplanned system upgrades or network maintenance, which could result in a loss in an outage.

Disclosure of confidential information. In relation to RPA, this risk lies in the possibility of deliberate or accidental incorrect training of the robot, in which data will be leaked to the internet or third-party users. For example:

- A bot developer could mistakenly program the Bot to upload highly confidential data, such as credit card information, to a database that is accessed by the public via the web;

- A bot developer could use his or her account to steal intellectual property [18].

The main identified root causes for RPA vulnerabilities are provided below, although it should not be considered as the finite list:

- Information disclosed by accident—a bot could be poorly designed and expose sensitive data to the internet or other unsecured source;

- Lack of or vulnerable encryption and access controls;

- Weak authentication features;

- RPA software bots require privileged access (or “power access”) to perform their required tasks, such as logging into ERP, CRM, or other business systems to access, copy or paste information or to move data through a process from one step to the next. This need for constant access means that privileged credentials are often hard-coded directly into the script or rules-based process the bot follows. Or the script may include a step to retrieve the credentials from an insecure location, such as a commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS*) application configuration file or database;

- RPA credentials are often shared so they can be used over and over again. Because these accounts and credentials are left unchanged and unsecured, a cyber attacker can steal them, use them to elevate privileges, and move laterally to gain access to critical systems, applications, and data. Or users with administrator privileges can retrieve credentials stored in insecure locations.

Some of the recommended security controls for RPA can be found in technical literature [19].

- Full audit logs;

- Integration of data protection technologies;

- Employing encryption;

- Resource and role-based access control;

- Minimize the attack surface area;

- Establish secure defaults;

- Principle of least privilege;

- Principle of defense in depth;

- Fail securely;

- Do not trust services;

- Separation of duties;

- Avoid security by obscurity;

- Keep security simple;

- Fix security issues correctly.

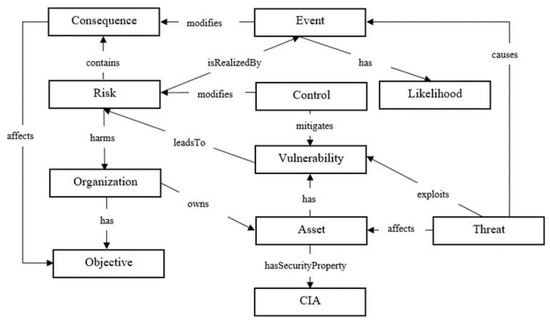

Still, it is necessary to say, that controls may vary depending on the RPA platform and there is no single point for such control inventory. For the successful design of a software robot, minimizing risks, ensuring the security of the robot, and compliance with industry-accepted standards, an RPA security ontology should be created and compared with the list of risk identification criteria in the current ISO/IEC 27005: 2018 methodology. ISO/IEC 27005: 2018 “Information technology—Security techniques—Information security risk management” [20]. Such an approach has been proven successful in security ontology construction [21,22]. ISO27005 standard provides guidelines for information security risk management that include information and risk management of telecommunications technology security risks. The methods described in this standard follow the general concept, models, and processes specified in ISO/IEC 27001 [23]. One of the ISO27005-based security ontologies was presented in «Towards the Ontology of ISO/IEC 27005:2011 Risk Management Standard V. Agrawal». The main concepts introduced and their relations are presented in Figure 2. Figure 2 presents the ontology to capture core concepts of the ISO27005 standard and the relationship among them.

Figure 2.

The proposed ontology for ISO27005 standard [21].

On the Figure 2 propose the following hierarchy: each class/entity is defined through a definition. The ontology class definitions are taken from ISO 27005 (27005, 2011) and ISOAEC 27000:2014 (27000, 2014).

Organization. This class represents a single person or a group that achieves its objectives by using its own functions, responsibilities, authorities, and relationships to achieve its objectives

Objective. This class represents the result to be achieved by an organization

Asset. This class represents any resource that has value and importance to the owner

Threat. This class represents a potential cause of an unwanted incident, which may result in harm to a system or organization.

Risk. This class represents the effect of uncertainty on objectives

Vulnerability. This class represents any weakness of an asset that can be exploited by one or more threats.

The related work demonstrates that a number of RPA-related threats exist, but neither they, nor appropriate countermeasures are systemized in one or another form, and even research on threats is still fragmented. The creation of a security ontology for RPA will make it possible to quickly determine the key points in information security issues: when designing a software robot, during active work, assess the degree of security of the robot, and determine what countermeasures should be taken to increase the degree of security.

3. Security Ontology for RPA

An ontology can be viewed as an apparatus for constructing a conceptual model of a domain, which includes concepts, relationships, and constraints on domain elements. Ontologies form the domain model of the PS, similar to the class diagram in UML.

Ontology on the Web contains a description apparatus, rules for constructing the syntax, and formalisms for defining a conceptual schema (model) containing data structures, relevant classes of objects, their relationships and theorems, statements, restrictions, etc.

Suggested ontology was created using the standardized OWL language. OWL is a Semantic Web language designed to represent rich and complex knowledge about things, groups of things, and relations between things.

To build the ontology the systematic domain analysis approach was utilized to capture the concepts and relationships specific to a particular type of subject area.

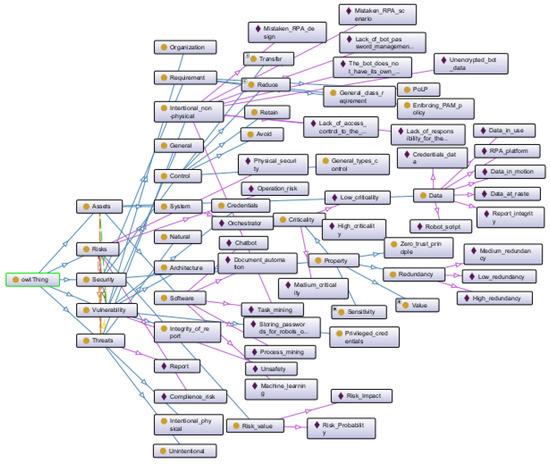

The proposed ontology includes 5 main concepts and 8 relationships. Figure 3 presents the ontology that captures the core concepts of RPA.

Figure 3.

Proposed OntoSecRPA ontology for RPA security.

The rationale behind the ontology is structured as follows:

- Robot owns some assets.

- Assets are protected by security. An asset has some vulnerability that leads to risk in the system, while a control decreases the vulnerability.

- A risk contains risk_value and risk_impact that affects robot performance.

- A potential risk harms the robot.

- Risk is realized by threats in the system.

- A threat affects an asset as it exploits the vulnerability of the asset.

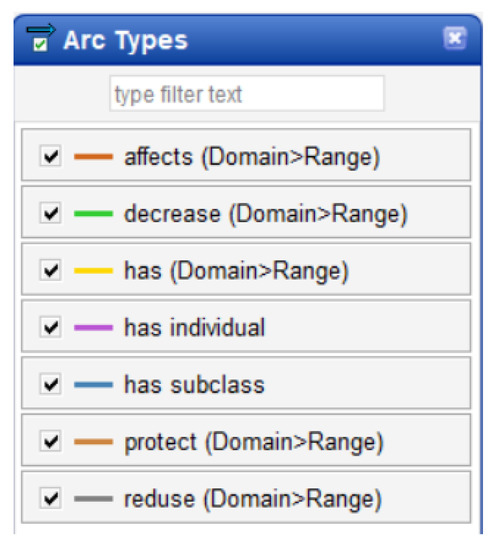

The colorful arcs shown in Figure 3 correspond to the related properties of the object. The color legend is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Types of arcs on ontograph.

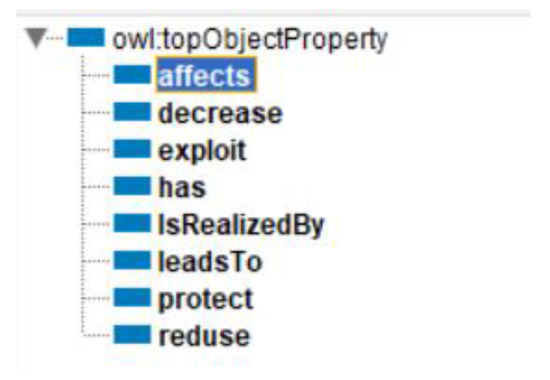

The list of object properties of the proposed ontology includes the following points (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Object property ontology for RPA security.

Explanations of object property (domains and ranges) are provided in Table 4. Information in this table should be read as follows: Threats Affects Assets, Security Decrease Vulnerability, and so on.

Table 4.

Domains and ranges of object properties.

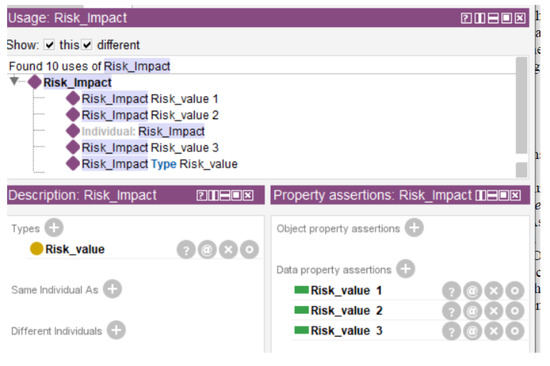

In addition to object properties, some instances of classes have date properties. In Figure 6 we can see the data properties of Risk_value. This value can change from 1 to 3, where the value depends on the value of Risk_Impact and Risk_Probability; 1 is low-risk impact and probability, 2 is medium-risk impact and probability, and 3 is high-risk impact and probability.

Figure 6.

Example of Data property of the OntoSecRPA.

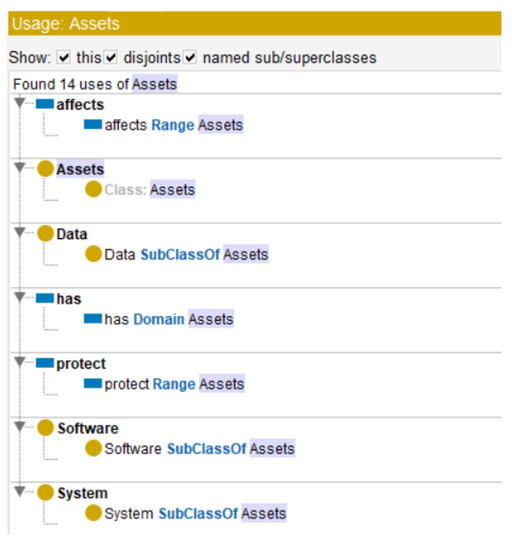

In Figure 7 we can see all interactions in class Assets.

Figure 7.

Interactions class Assets.

Below a description of different classes of OntoSecRPA ontology, related parameters, and actions is provided. The ontology was developed using Protege 5.6.1. Due to the big ontology size later, separate parts are extracted and described for a more comfortable view. Practical samples are based on the IBM Robotic Process Automation platform.

The proposed ontology has the following base metrics. All values were taken from Protégé 5.6.1 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Base metrics for OntoSecRPA ontology.

3.1. Assets

Assets usually represent shared variables or credentials that can be used in different automation projects. They allow you to store specific information so that the robots can easily access it.

The Get Asset and Get Credential activities used in Studio request information from Orchestrator about a specific asset, according to the provided AssetName. If the AssetName provided in the studio coincides with the name of an asset stored in the Orchestrator database, and the robot has the required permissions, the asset information is retrieved and used by the robot when executing the automation project. There are four types of assets:

- Text—stores only strings (it is not required to add quotation marks);

- Bool—supports true or false values;

- Integer—stores only whole numbers;

- Credential—contains usernames and passwords that the Robot requires to execute particular processes, such as login details for SAP or SalesForce [24].

A credential is a key that identifies in IBM Robotic Process Automation a user and password pair. You use credentials to access an application, module, or a specific feature that is being automated. You can also use credentials to automatically unlock the machine where the bot will be executed.

For the system vault, the credential represents a set of users and passwords, whereas, for the user vault, the credential itself does not represent a specific user, nor a set of users and passwords, but rather a “profile” of a specific user and password pairs. Credentials are used in bots for users who must perform a task or process. These credentials are also used in the execution of user-scheduled requests in IBM Robotic Process Automation, and in these cases, the system impersonates the user represented by the credential logged in at the time of scheduling. Note that all user access permissions are used to perform the task [25].

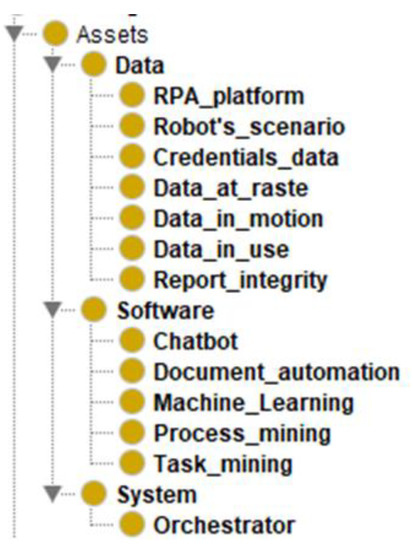

There are we highlight 3 groups of assets: Data, Software, and System (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed ontology for RPA: Assets.

The description of Data group assets is provided below:

- Robot’s_scenario—an accurate, step-by-step description of all the robot’s actions to achieve the assigned task. Based on the script, a diagram is created, the developer tests the execution of processes, configures the program, and eliminates the errors that arise;

- Assets Platform_RPA data is assumed that border directly on the functionality of the robot: data on the validity of licenses, the operability of the robot application, data on the robot launch control module;

- Credentials_data—credentials that are passed to the robot to work with third-party programs that require authorization;

- Data at rest. This term used is a term used to describe all data in computer storage that is not currently being used or transmitted. Data at rest is not a fixed state, although some data may remain in archived or help files, where it is rarely or never used or moved. Examples of stored data might include important corporate files stored on the hard drive of an employee’s computer, files on an external hard drive, data left on a storage area network, or files on the servers of a third-party backup service provider;

- Data in use. To protect the user vault’s credentials, the Bot Runtime requests them to the Bot Agent when needed. Then, the Bot Agent makes another request to the Vault system, which prompts the user to open the Vault if it is not opened yet and returns the encrypted master password to the Bot Agent. With this, the Bot Agent now requests to the IBM Robotic Process Automation API the public and private key pair and, after they are returned, they are used to decrypt the master password and get the credential. In the system vault, the private key is obtained using the specified configuration in the Web Client, and the public is stored in the Server;

- Data in motion. The data traffic between the IBM Robotic Process Automation Server and the Vault, both user and system vaults, is encrypted using polymorphic algorithms, employing a variety of secure encryption algorithms and OTP*. [25];

- Report integrity. Cleardata’s Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Service uses software robots to automate business data reporting. The robots can login to your business systems, gather data, and pull together your data reporting.

3.2. Security

Because of the volume of automation, RPA inherently deals with much confidential business data, regardless of whether the technology is deployed within an SME* (small-medium enterprise) or a global company. In automating everyday business processes such as transferring files, processing orders, and running payroll, RPA’s software robots process information from various company databases and log into different accounts using supplied passwords. In this way, the automation platform gains access to all kinds of information (inventory lists, credit card numbers, addresses, financial information, passwords, etc.) about a company’s employees, customers, and vendors [26].

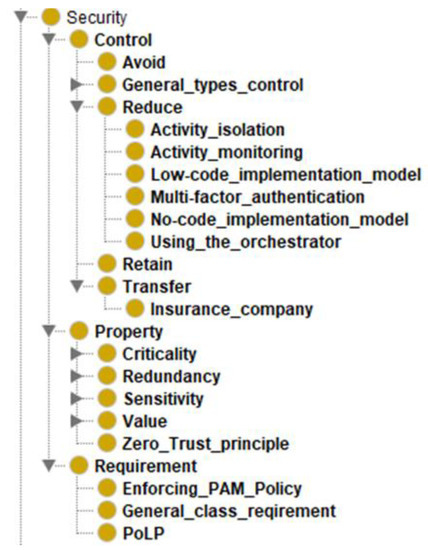

The Security class of the OntoSecRPA is split into 3 sub-classes (Control, Property, and Requirement), each of which has its sub-classes on its turn (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Proposed ontology for RPA: Security.

Consider the most important of them:

Multifactor authentication. No access or action regarding RPA should be permitted without prior authentication. This applies to humans and bots, as well as unattended and attended automation. This is conducted with an Enterprise Control Room to manage and monitor all the processes of your RPA infrastructure.

- Control Room authentication includes integration with Microsoft Active Directory using LDAP*, Active Directory using Kerberos, and local authentication using the embedded Credential Vault or an external third-party-privileged access system, such as CyberArk;

- Completing a task could involve a single authentication with one person and his or her credentials. Or, it could involve multiple authentications with more than one person and their credentials, as well as application credentials. You need a solution that accommodates all types: single and multifactor. Automation Anywhere offers that flexibility.

Comprehensive access control. Successful authentication is only the first level of security to consider. Within the typical architecture and primary functions of an RPA platform, bot access to systems should be centrally administered and controlled. That is accomplished by using an extensive set of role-based access controls to determine which user may perform which action(s) in the system at scale.

- Enterprise Control Room provides multilayered identification and authentication to restrict access of users and attended and unattended bots to systems and data. Administrative roles and steps are available to enforce principles of least privilege and separation of duties;

- Automation Anywhere takes the separation of duties to a higher level with fine-grained RBAC that offers customization. Administrators can easily define custom roles, and setting privileges/permissions of objects and functions—including user management, licensing, dashboards, and audit logs. This added capability makes it possible to share bots while separating access by business units and functions;

- In addition, bots created with Automation Anywhere RPA can be restricted to only operate using a specific set of user IDs (human or system). This further strengthens the segregation of duties and auditing capabilities.

End-to-end data encryption. Equally important for a secure environment is maintaining the confidentiality and integrity of data. The solution should not only protect data at rest and in transit but also while it is being used on systems.

- For data at rest, Automation Anywhere encrypts local credentials and selected runtime data used by bots and provides secure storage for sensitive configuration information. For data in transit between components, Transport Layer Security is employed. Runtime security includes distributed credential protection—no credentials are stored locally.

Zero-trust principles

- Avoid reusing human workers’ credentials for bots to save short-term costs;

- treat each bot as an IT asset;

- assign each bot to an automation owner;

- apply zero-trust principles to secure your bots;

- remember that RPA bots can be an internal or external attack point;

- a summary of this subsection is needed.

3.3. Threats and Vulnerabilities

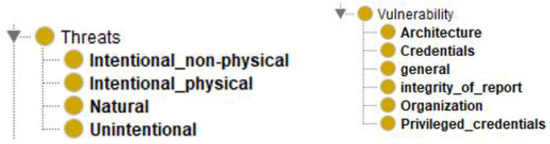

Despite its many advantages and application areas, RPA technology has a number of vulnerabilities and related threats. Exposed vulnerabilities can cause big financial and reputational damage. Knowing them is also important from the security control deployment and risk management perspective (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Proposed treats and vulnerability or RPA: Threats and Vulnerabilities.

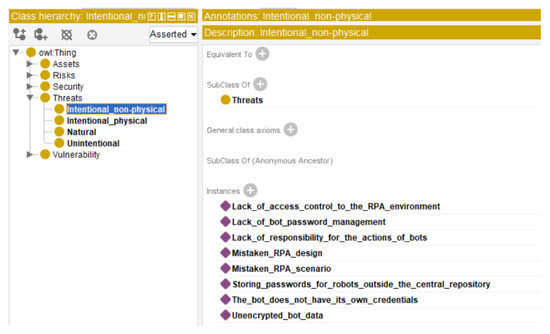

A threat is anything that can disrupt or harm a robot. Threats can be natural, intentional, and unintentional. Natural disasters are hazards such as earthquakes, floods, and wildfires that are random in duration and impact. Intentional threats are intentional actions, such as stealing data or damaging computer resources, hardware, and data. Unintentional threats are explained by the human factor, i.e., leaving the door to IT servers unlocked or leaving the front door of an organization containing sensitive information unattended (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Proposed instances for Threats.

A vulnerability is a weakness in a security system that attackers can exploit to achieve their goals. A vulnerability assessment is a systematic review of weaknesses in a security system and evaluates if a system is affected by any known vulnerabilities, it should assign severity levels to those vulnerabilities and then recommend a fix or mitigation if and when needed. Vulnerabilities in the work of RPA can be:

Architecture—an incorrectly built robot architecture can become a weak point in its application, for example, vulnerabilities in the backend of the RPA system can provide cyber-attacks with access to the corporate network.

Credentials, and in particular privileged credentials, can be illustrated either by the accounts of members of an IT group or by the accounts of employees who process sensitive company data on a daily basis.

In terms of automation, the risks associated with privileged access abuse by RPA robots are similar to the risks associated with privileged access abuse by humans, i.e.,

- The privileged access granted to a robot account can be used by attackers to compromise the system and steal or misuse sensitive information;

- Attackers can train a robot to disrupt important business processes related to customers, orders, or transactions.

The integrity of the report. The activity report of a robot that has undergone a violation of its integrity: a change in internal data is also a vulnerability. Most RPA systems today use data encryption, which reduces the risk of vulnerabilities, but they still occur in some relatively weakly secure solutions.

The Organization’s vulnerability refers to the presence of weaknesses in the performance of the system as a whole. Due to a hardware or software system, events may stop occurring. A simple frequent case related to human problems (employee errors), equipment condition, errors on messages, and interaction of software solutions. A network failure can break the robot, similar to other solutions and show performance results. Interruptions in the system or even its shutdown can cause overload, a rapid sequence of actions of the robot, to the system getting into an unready system.

4. Ontology Formal and Experimental Verification

In this section, we perform the formal verification of the proposed ontology in order to ensure its correctness. Later the OntoSecRPA ontology is used to demonstrate its applicability for practical tasks in the case scenario of a finance department in a fictional ACME company.

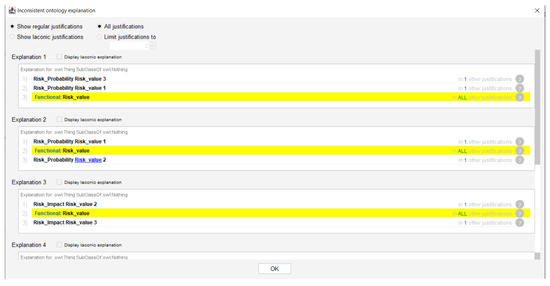

The ontology was first evaluated with the help of HermiT. HermiT is a reasoner for ontologies written using the Web Ontology Language (OWL) [27].

Through the use of this tool, inaccuracies in the specified properties were identified (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Ontology evaluation with HermiT.

After correcting the identified inaccuracies, we proceed directly to verification ontology.

4.1. Formal Ontology Verification

For determining the quality of the developed ontology of a specific domain, it is necessary to determine the methods and stages of ontology verification. By verifying the ontology, we mean evaluating the technical quality of an ontology against a set of criteria, depending on the method of ontology evaluation [28]:

- data-driven method;

- expert-based evaluation method;

- comparison with a “gold-standard”;

- evaluation of ontograph topology.

Data-driven methods are associated with the extraction of concepts—the basic concepts of a given subject area and building links between concepts thus determining the relationships and interactions of basic concepts. The completeness and consistency of the knowledge presented in it determines the quality of the developed ontology.

For expert-based evaluation methods, it is necessary to collect opinions of people competent in the domain area and to perform evaluations on the basis of their evaluation.

The method of comparison with the “gold standard” implies finding similarities between the prepared ontology and the already existing one, taken as a standard. The similarity between ontologies is calculated using the similarity function: sim: O × O → [0, 1].

The method of ontograph topology evaluation evaluates the basic indicators associated with the structure of the developed ontology.

Since the development of ontology in our case was standard-based, thus ensuring completeness of the domain knowledge, expert-based evaluation is considered subjective in many cases and there is no “gold-standard” in the domain yet, the ontograph evaluation method was selected for OntoSecRPA ontology verification.

In order to determine if the metric values are acceptable, it is initially necessary to get information about the size of the ontology. To do this, it is necessary to calculate the following metrics: the number of graph vertices, the maximum distance from the root node, the number of ontology tree leaves, the number of ontology tree vertices that have leaves in their immediate descendants, and the number of ontology graph arcs. The values for the OntoSecRPA ontology are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Value of OntoSecRPA Ontology Size Metrics.

The next stage of ontology evaluation is dedicated to detecting critical errors, i.e., such errors, that make further evaluation of ontology pointless until they are corrected. Such errors are the presence of cycles in the ontology and multiple inheritances. Values for the ontology presented are given in Table 7.

Table 7.

Critical errors in OntoSecRPA.

Later analysis of the depth metric value is performed. This metric evaluates the balance of ontological models, as well as the quality of perception of ontological models, which is characterized by the length of different graph paths [28].

There are three metrics for calculating depth by Gangemi:

Absolute depth. This value is calculated as the sum of the lengths of all graph paths (any sequence of interconnected vertices that starts from the root vertex and ends with a leaf of the graph) (1).

where is the cardinality of each path j from the set of paths P in a graph g.

Average depth. The average depth states at which degree the ontology has vertical modeling of hierarchies. Equals the absolute depth divided by the number of paths in the graph (2):

where is the cardinality of each path j from the set of paths P in a graph g and is the cardinality of P.

Maximum depth. Equals the maximum path length (3)

where N_(j∈P) and N_(i∈P) is the cardinality of each path j from the set of paths P in a graph g.

The depth metrics are provided in Table 8.

Table 8.

Depth Metrics of OntoSecRPA Ontology.

It should be noted that the maximum depth of OntoSecRPA consists of 3 concepts, which meet the requirements of ergonomics: the smaller the depth, the easier the graph is to perceive.

The next evaluated metrics are cardinalities: absolute root cardinality, absolute leaf cardinality, and absolute sibling cardinality. Cardinality is a property of a graph that expresses a graph-related number of specific elements.

Absolute root cardinality. The absolute cardinality of roots is a property of a directed graph that represents the number of root nodes in the graph (Equation (4)).

where is the cardinality of the set ROO in the directed graph g.

Absolute leaf cardinality. Absolute root cardinality is a property of a directed graph that is related to leaf node sets and represents the number of leaf nodes of the graph (Equation (5)).

where n_(LEA⊆g) is the cardinality of the set LEA in the directed graph g.

Absolute sibling cardinality. Absolute root cardinality is a property of a directed graph that is related to sibling node sets and represents the number of sibling nodes of the graph (Equation (6)).

where N_(j∈SIB) is the cardinality of a sibling set j from SIB in the graph g.

The OntoSecRPA cardinalities are given in Table 9.

Table 9.

Cardinalities of OntoSecRPA Ontology.

The Absolute leaf cardinality metric characterizes the “Understandability” of the ontology. The Absolute root cardinality and Absolute sibling cardinality metrics evaluate the quality of the ontology in terms of “Cohesion”. The higher these values, the more accurate the ontology. The developed ontology has a sufficient degree of accuracy and coherence.

Finally, the breadth metric is evaluated. This property is related to the number of levels, so-called generations, in a directed graph.

Absolute breadth. Is equal to the sum of the number of vertices for each level of the hierarchy across all levels (Equation (7)).

where , is the cardinality of each level/generation j from a set of generations L in a directed graph g.

Average breadth. The average breadth states at which degree the ontology has horizontal modeling of hierarchies (Equation (8)).

where is the s the cardinality of each generation j from the set of generations L in a directed graph g and is the cardinality of L.

Maximum breadth is equal to the number of vertices on the largest level by the number of vertices. The smaller it is, the better from the point of view of cognitive ergonomics (Equation (9)).

where N_(i∈L) and N_(j∈L) is the cardinality of each generation j from the set of generations L in a graph g.

The metric “Maximum ratio of the width of neighboring levels” is a metric included in the analysis of the main metrics, within which the vertices are counted for each level of the ontology [28].

The OntoSecRPA breadth values are given in Table 10.

Table 10.

Breadth values of OntoSecRPA Ontology.

The breadth metric corresponds to the recommended minimum, since small values of these metrics are preferable, as the smaller the breadth, the better the ontology from the point of view of cognitive ergonomics.

The given estimates of the main ontology metrics demonstrate, that OntoSecRPA ontology has no critical errors, the average depth and breadth values are small, and indicate the uniformity of distribution and susceptibility from the point of view of cognitive ergonomics. However, the obtained cardinality value requires additional analysis of ontology branches to minimize the value, although this could be problematic due to the domain specifics. In general, formal verification is evaluated as positive.

4.2. Experimental OntologyVerification

The objective of this task is to show the ontology potential for risk identification. Experimental evaluation is not considered to be a full-scope risk analysis scenario but rather serves for demonstrational and proof-of-concept purposes. Table 11 presents the overview of all the classes of ontology and instances of each class based on the scenario. Later in Table 12, Table 13, Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16 sub-cases of the main scenario are analyzed in more detail.

Table 11.

Classes of ontology and instances of each class based on the scenario.

Table 12.

Case 1: Settlement with Suppliers and Contractors for Goods and Services Delivered.

Table 13.

Case 2: Verification of Transactional Data Collected from Several Sources.

Table 14.

Case 3: Bank Account Reconciliation.

Table 15.

Case 4: Data Creating and Tracking in the Ledger.

Table 16.

Case 5: Provision of Reports in a Pre-Approved Format.

Risk is calculated according to (Equation (10).

and is classified as follows: very low = 1, low = 2, medium = 3, high = 4, very high = 5.

Scenario

By the end of the reporting period, the ACME accounting department has to close the monthly records in order to balance the accounts and provide an accurate financial statement. This process is known to be a routine procedure due to manual data extraction and entry, causing overtime, and requiring attention to detail, thus making it a good candidate for RPA automation.

Tasks that can be delegated to the robot:

- the settlement with suppliers and contractors for goods and services delivered;

- verification of transactional data collected from several sources;

- bank account reconciliation;

- data creating and tracking in the ledger;

- provision of reports in a pre-approved format.

The above examples and scenarios show that the assets, security, threats, and vulnerabilities associated with the implementation of RPA are not much different from the traditional components that are commonly found when working with other systems. However, there are still characteristic features exclusively for systems with RPA, so the developed scenarios in the financial sector make it possible to highlight these features.

Using the identified threats and vulnerabilities later experts can perform risk analysis in a more efficient way, calculating risk values and taking into consideration already company-specific information. However, it should be noted that due to the use of ontology, the time for conducting risk analysis be reduced several times, since ontology serves as a checklist for threat and vulnerability identification.

It should be noted that the purpose of this work was not to concern the computational overhead in the cost and complexity of the proposed computational work. We considered it expedient to carry out the calculation in practical application to a specific problem, which can become part of the study of the future.

5. Conclusions

The performed literature review has shown that widely used RPA technology has a number of information security risks due to a high number of communicating components and channels, utilizing different communication protocols used and there is a need for their risk management and mitigation. For efficient risk management there is a need for a single source of information were RPA related assets, threats, and countermeasures could be stored and ontology could be seen as a promising way of storing such data, but currently no RPA-security-related ontologies were found and the need for developing RPA security-oriented ontology arise. The creation of a security ontology for RPA will make it possible to quickly determine the key points in information security issues: when designing a software robot, during active work, assess the degree of security of the robot, and determine what countermeasures should be taken to increase the degree of security.

The OWL-based OntoSecRPA ontology was proposed with the following core concepts: asset, threat, vulnerability, risks, security goal, and defense strategy. All the core concepts are subclassed or instantiated to provide the domain vocabulary of information security. Ontology can be used as a source of information on RPA security in such tasks as risk assessment or the development of RPA-related expert systems.

The performed formal OntoSecRPA ontology verification using the ontograph topology evaluation method has demonstrated that the proposed topology has no critical mistakes and fulfills the ergonomic requirement in the majority of evaluated metrics. Later performed a demonstration of the ontology used for risk assessment in a typical RPA application scenario in financial accounting has shown both principal ontology usability for this and the potential for minimizing time consumption for risk assessment and making it more systematic.

We hope that the proposed ontology will be a trigger for discussions leading to the general increase of RPA security and research on the topic. Ontology can be downloaded from [29].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G.; methodology, N.G.; validation, A.K.; formal analysis, N.G.; investigation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, N.G.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available and can be found here: https://github.com/oleferovich/-OntoSecRPA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gartner. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2022-08-1-rpa-forecast-2022-2q22-press-release (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Gitnux. Available online: https://blog.gitnux.com/robotic-process-automation-statistics/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Cigen. Available online: https://www.cigen.com.au/cigenblog/security-risks-robotic-process-automation-rpa-how-prevent-them (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Štorga, M.; Andreasen, M.M.; Marjanović, D. Towards A Formal Design Model Based on A Genetic Design Model System. In Proceedings of the ICED 05, the 15th International Conference on Engineering Design, Melbourne, Australia, 15–18 August 2005; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanauskaite, S.; Olifer, D.; Goranin, N.; Čenys, A. Security Ontology for Adaptive Mapping of Security Standards. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control. 2013, 8, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.-F. Ontology-Based Metrics Computation for System Security Assurance Evaluation. J. Appl. Secur. Res. 2022, 12, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smekhun, Y.A.; Sistemakh, O. Ontologies in the knowledge based systems: Possibilities of their application. Int. Res. J. 2016, 5, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, A.I. Organizational and Economic Modelling: Textbook: In 3 Parts; Part 2: Expert Opinions—M.: Publishing House of BMSTU: Beijing, China, 2016; p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Vrandeci, D. Ontology Evaluation. [Electronic Resource]. Ph.D. Thesis, Karlsruher Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany, 2010; 235p. Available online: http:simia.net/download/ontology_evaluation.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Hlomani, H.; Stacey, D. Approaches, methods, metrics, measures, and subjectivity in ontology evaluation: A survey. Semant. Web J. 2014, 1, 1–11. Available online: http://www.semantic-webjournal.net/system/files/swj657.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Gangemi, A.; Catenacci, C.; Ciaramita, M.; Lehmann, J. Ontology Evaluation and Validation an Integrated Formal Model for the Quality Diagnostic Task; Laboratory of Applied Ontologies—CNR: Rome, Italy, 2005; pp. 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.R.; Fensel, D. Knowledge engineering: Principles and methods. Data Knowl. Eng. 1998, 25, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M. 3. Schumacher, M. 3. Ontologies. In Security Engineering with Patterns; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumas, B.; Dritsas, S.; Gritzalis, D. An Ontology-Based Approach to Information Systems Security Management. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Mathematical Methods, Models, and Architectures for Computer Network Security, St. Petersburg, Russia, MMM-ACNS 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanauskaite, S.; Shein, A.; Cenys, A.; Rastenis, J. Security Ontology Structure for Formalization of Security Document Knowledge. Electronics 2022, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElectoNeek. Security Concerns in RPA: A 4-Step Guide to Address Them. Available online: https://electroneek.com/blog/security-concerns-in-rpa-4-step-guide-to-address-them/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Microsoft. Azure Policy Built-in Definitions for Azure Virtual Machines. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/virtual-machines/policy-reference (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- EY. How do You Protect the Robots from Cyber Attack? Retrieved 20 November 2021. Available online: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-how-do-you-protectrobots-from-cyber-attack/$FILE/ey-how-do-you-protect-robots-from-cyberattack.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Automationanywhere. 10 Best Practices for Secure Bot Design. Available online: https://www.automationanywhere.com/company/blog/learn-rpa/ten-best-practices-for-secure-bot-design (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- ISO/IEC 27005:2018. Information Technology-Security Techniques -Information Security Risk Management. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75281.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Fenz, S.; Plieschnegger, S.; Hobel, H. Mapping information security standard ISO 27002 to an ontological structure. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2016, 25, 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001. Information Security Systems. Available online: https://www.iso.org/ru/isoiec-27001-information-security.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Clarke, N.; Furnell, S. Proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security & Assurance; HAISA: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uipath. About Assets. Available online: https://docs.uipath.com/orchestrator/docs/about-assets (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- IBM. IBM Robotic Process Automation Vault. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/rpa/20.12?topic=security-vault#what-is-a-credential (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Uipath. The Security Requirements for a Global RPA Platform. Available online: https://www.uipath.com/blog/the-security-requirements-for-a-global-rpa-platform (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- HermiT OWL Reasoner. Available online: http://www.hermit-reasoner.com/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Bolotnikova, E.S.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Gorovoy, V.A. On one method for evaluating ontologies//Izvestiya RAN. Theory Control Syst. 2011, 3, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub. Link for Downloading the Ontology. Available online: https://github.com/oleferovich/-OntoSecRPA (accessed on 8 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).