Abstract

Trust in information and communication technology devices is an important factor, considering the role of technology in carrying out supporting tasks in everyday human activities. The level of trust in technology will influence its application and adoption. Recognizing the importance of trust in technology, researchers in this study will examine trust components for the development of a type 2 diabetes mobile application. The results of this study resulted in three major focuses, namely the application design (consisting of architecture), UI design, and evaluation of trust factors of the application: functionality, ease of use, usefulness, security and privacy, and cost. This analysis of trust components will be useful for the application or adoption by users of a type 2 diabetes mellitus mobile application so that users will trust the application both in terms of functionality and the generated information.

1. Introduction

1.1. Mobile Health Application for Diabetes Mellitus

Mobile health applications are software tools that help users monitor their health conditions via smartphones and tablets [1]. Their functionality ranges from simple diaries, medication reminders, and tracking health progress to more complex programs certified as medical devices by health authorities. Currently, mobile health applications with a large number of users have a high potential for improving healthcare [2]. The reliability of these applications remains in doubt, limiting their widespread adoption [3]. Extensive research on trust in technology and the role of user trust in the selection of various information technology (IT) artifacts have yet to be conducted [4].

Diabetes mellitus is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous metabolic disorder characterized by carbohydrate tolerance loss [5]. Diabetes mellitus is clinically characterized by fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia, atherosclerosis, and microangiopathic vascular disease [6].

Diabetes mellitus is classified into two types: type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is characterized by the pancreas, the body’s insulin factory, being unable or less able to produce insulin [7]. As a result, the body’s insulin is lacking or not present at all, and sugar accumulates in the blood circulation because it cannot be transported into cells [8]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common type [9]. The pancreas can still produce insulin in type 2 diabetes, but the quality of the insulin is poor, and it cannot properly function, causing blood glucose levels to rise [10]. Patients with this type of diabetes usually do not need additional insulin injections in their treatment but do need drugs that work to improve insulin function, lower glucose, improve sugar processing in the liver, and perform several alternative treatments for support [11]. Age, sex, family history, physical activity, and eating habits are the risk factors that have the greatest association with the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among the many factors that cause diabetes mellitus [12].

All types of diabetes can cause many complications in the body and increase the risk of premature death. Heart attack, kidney failure, stroke, leg amputation, vision loss, and nerve damage are all possible complications. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic disease that requires ongoing therapy and patient education to prevent acute complications and lower the risk of long-term complications [13].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) problems can be overcome in various ways, including pharmacologically and non-pharmacologically. Non-pharmacological therapy includes lifestyle changes by adjusting diet (medical nutrition therapy), therapy using fruit juice, increasing physical activity, and education on various problems related to diabetes, all of which are continuously carried out. Pharmacological therapy includes oral anti-diabetic administration and insulin injections. Pharmacological therapy should be used in conjunction with non-pharmacological therapy [14].

1.2. Usability Test

Usability has a word for “usable”, which is defined as being useful. To be considered good, something must minimize failure while also providing satisfaction and benefits to application users [15]. Usability is the ease of using something. In this case, it is intended that the developed application be simple to use and testing be conducted to determine the success of the developed application by focusing on ease, effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction of users [16].

Usability is a factor that determines whether an application is good or not. There are five main components of usability [17]. The five components are learnability (easiness to learn), efficiency (efficiency), memorability (ease for users to remember), errors (error rate), and satisfaction (satisfaction) [18].

Usability testing is a process that involves people as test participants, representing targets, to evaluate the extent to which a product meets usability criteria [19]. Usability testing can be performed by interviewing or giving questionnaires to users [20]. In testing the user groups, it is recommended to use 3–4 users from each category if there are two groups. However, if there are three or more groups of users, then use three users from each category for the usability level measurement listed in Table 1 [21].

Table 1.

Usability Level Measurement.

1.3. Trust in the Mobile Application

The idea of competence is that an agent will safely, dependably, and consistently operate in a particular situation, which underlines how crucial trust is to the deployment of any online ecosystem. That is, whether an entity decides to do business with another firm is heavily influenced by trust in the original firm. The authors argue that, before using or providing services in an electronic market, both the consumers and providers must have trust in one another. If there is no mutual trust between them, then resources will not be fully shared, and there may be a lot of fraudulent transactions. Such a situation would be detrimental to honest buyers and sellers, preventing them from taking advantage of the benefits of the online world [22].

Trust, as it is in the online system, is critical to the success of mobile applications. Customers must constantly choose which mobile apps to download and/or use because there are hundreds of thousands of them available in application stores. When several mobile apps with comparable functionalities begin to appear in application stores, the decision becomes even more difficult because users must choose the most reliable application. Customers will always prefer to download and use a mobile app that is useful, dependable, and of high quality. However, it can be difficult to choose a mobile app that is thus practical, trustworthy, and high quality. This is evident from the numerous comments left by users who downloaded poor-quality mobile applications and expressed their frustration with them in the application shops. Therefore, it is essential to establish early confidence in mobile apps before users download and use them [23].

From a security and privacy standpoint, the emergence of mobile apps poses additional threats to the confidentiality of information and data. There have been several instances where mobile apps have grabbed and mined private information from users, including address books, photographs, and more. Such occurrences blatantly expose the invasion of the client’s privacy and further harm the consumers. Unfortunately, it reveals that more than half of the popular mobile applications for Android and iOS under consideration send user data to third-party servers. Aside from the issue of individual privacy, an increasing number of organizations and businesses are also opposed to their employees using mobile devices [24]. They are extremely concerned about the possibility of mobile apps accessing and gathering sensitive and important company documents (e.g., through business emails on mobile devices).

Installing security measures and policies can reduce the risk of sensitive business information being leaked to the public, but these must be supplemented and improved by the use of trust measurement. The majority of security experts agree that the best strategy for reducing the risk of document leakage in mobile apps is to prevent applications from being installed in the first place. However, such a strategy could not be advantageous for both employees and enterprises, especially in light of the fact that mobile apps increase employee productivity and benefit companies. Therefore, there are only two options left for protecting crucial corporate data: teach staff how to choose legitimate mobile apps and provide them tools for evaluating the reliability of mobile apps before installing and using them. Measuring trust in mobile apps is critical as the primary and additional layer of security and privacy protection. Trust also improves security by better-securing resources and information [25].

1.4. Previous Research

Initially, the development of an Android mobile application was focused on controlling type 2 diabetes. At this point, the research team had 20 people, ten with diabetes and ten without, participate in the use of diabetes mobile applications with supporting hardware, such as a wearable band, glucose meter, and treadmill [26]. The results of the initial research are used as reference material for the development of the second stage. At this stage, the researchers evaluate some of the functionality and accessibility of the application by conducting tests involving 40 people, consisting of twenty with diabetes and twenty without diabetes. The results of the second stage of research conclude that there is a need for changes and adaptation of applications for users, especially related to user registration for applications, as well as glucometer and wearable band (smartwatch) connectivity with various versions [27]. Previous researchers have conducted preliminary research through two previous studies, which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Previous Research.

2. Analysis

2.1. Mobile Application in Healthcare

Smartphone users continue to increase as mobile phones become more sophisticated, efficient, and portable. The use of smartphones has become an important item and a lifestyle in society. A mobile application is one that enables mobility through the use of equipment, such as a cell phone (mobile phone), a PDA (personal digital assistant), or a smartphone [28]. Mobile applications can wirelessly access and use a web application using a mobile device, where the data obtained is only in the form of text and does not require much bandwidth. The use of the mobile application only requires a mobile phone that is equipped with General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) facilities and its connection. There are several aspects that must be considered to build a mobile application, especially the hardware. In terms of bandwidth, the current network conditions have made it possible to obtain a large enough bandwidth for the cellular network [28]. Table 3 summarizes the application classification in healthcare.

Table 3.

Application Classification in Healthcare.

Several mobile-based applications in the healthcare sector have been developed with a variety of operating systems, depending on user needs, such as Android, iOS, Windows Mobile, Blackberry OS, and Symbian. Android is a mobile device software collection that includes an operating system, middleware, and the main mobile applications [29]. Android has four distinct features (Table 4) [30,31].

Table 4.

Android Characteristics.

2.2. Telehealth

As a part of telehealth, telemedicine focuses on the therapeutic side, while telemedicine covers the prophylactic, preventive, and therapeutic aspects. One of the functions of telehealth and a major requirement for providing health services is patient monitoring and scheduling [32]. The coverage of telehealth, telemedicine, and electronic health (e-health), as well as telecare and m-health, is described by Totten AM et al. (Table 5) [33].

Table 5.

Telehealth Operational Definition.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Method

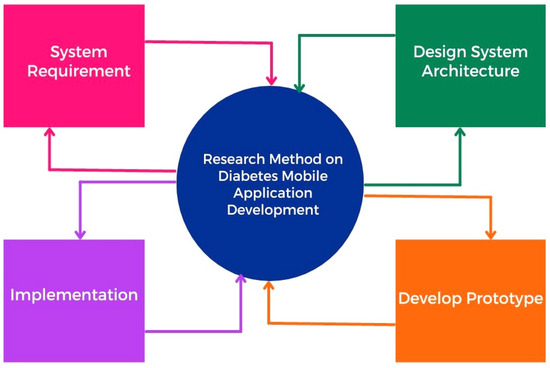

This study was carried out at Kangwon National University’s Circuit and System Design Laboratory with several systematic stages in order to produce research reports and products (a mobile application) that were in accordance with the objectives of the research implementation. The research method includes four stages (Figure 1), starting with system requirements, designing system architecture, developing a prototype, and implementing it.

Figure 1.

Research Method.

3.2. Software Development Methodology

A “framework” is a software development method that is used to structure, plan, and control the process of developing an information system. Over the years, many different frameworks have been developed, each with its own set of strengths and weaknesses. The prototype model is suitable for exploring customer requirements and specifications in more detail, but it has a high risk of increasing project costs and time. The software development model used is a prototype model [34].

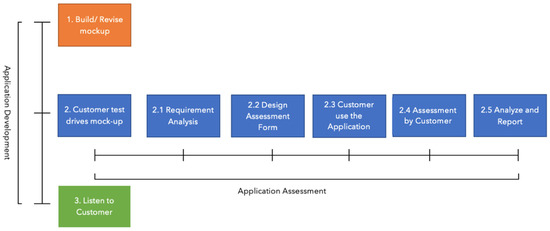

In developing this application, we use the prototype model as an approach to mobile application development. We undergo three stages: creating and revising the mockup, conducting customer test drives, and listening to customers. All steps in this prototype model were chosen because they are in accordance with the project being developed, which does not have many stages, and the parties or teams involved can also be maximized in the three existing stages (Figure 2). The details of each process are summarized in Table 6.

Figure 2.

Application Development and Assessment Process.

Table 6.

Application Development and Assessment.

4. System Design

4.1. User Interface

The user interface (UI) is the part of the experience with which the user interacts [35]. UI is not just about colors and shapes but about providing users with the right tools to achieve their goals. In addition, UI is more than just buttons, menus, and forms that the user must fill out. A “user interface” is used when the system and users can interact with each other through commands, such as using the content or entering data. The user interface is one of the most important aspects of application development because it is visible, audible, and touchable. At this point, the researchers have created (Table 7) a user interface for the type 2 diabetes mellitus mobile application based on the appropriate needs.

Table 7.

Design of the Application.

4.2. Benefits of Application and Trustworthiness

In application development, there must be benefits that are expected to be the goal of developing the application. The following are the potential benefits of the type 2 diabetes mellitus mobile application. Table 8 summarizes the potential benefits of the application.

Table 8.

Potential Benefits of the Application.

Trust components in the development of an application are an important factor (Table 9). An application user will feel comfortable using the application if it has a good level of trust. The development of the type 2 diabetes mellitus mobile application includes the following trust components.

Table 9.

Trust Components in Mobile Application Development.

4.3. Unified Modeling Language and Design Testing

Software testing is critical because everyone makes mistakes when developing software. Each software program’s errors will be distinct. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct software testing to verify and validate that the program or application created meets the requirement. If it is not the same as what is needed, it is necessary to evaluate it so that improvements can be made to the software.

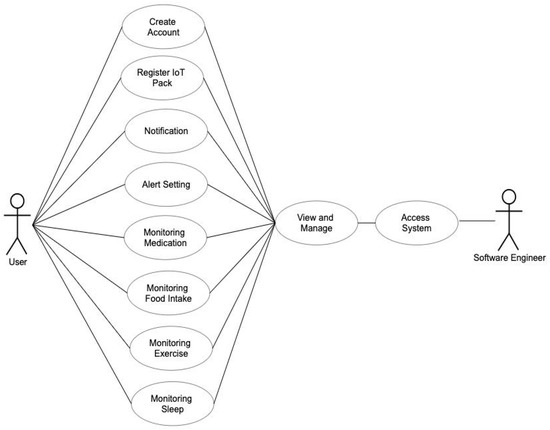

- Use Case Diagram

The Use Case diagram in the development of diabetes mobile applications will describe the interaction relationship between the system (diabetes mobile application) and the actors involved in the system. The diagram will fully and sequentially describe existing business processes and activities and describe the contents of the diabetes mobile application, where in this diabetes mobile application, the Use Case Diagram is formed from (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Use Case Diagram of User Activities.

- Actor (two actors): The actor (User) is the user of the diabetes mobile application, and the other actor (Software Engineer) is the application developer;

- Use case (10 use cases): Create an Account, Register to IoT Pack, Notification, Alert Setting, Monitoring Medication, Monitoring Food Intake, Monitoring Exercise, Monitoring Sleep, View and Manage, and Access System;

- Association (18 associations): Association between the actor (User) and Use Case, Create an Account, Register to IoT Pack, Notification, Alert Setting, Monitoring Medication, Monitoring Food Intake, Monitoring Exercise, and Monitoring Sleep. Association between the actor (Software Engineer) to Use Case Access System, View and Manage, Create Account, Register to IoT Pack, Notification, Alert Setting, Monitoring Medication, Monitoring Food Intake, Monitoring Exercise, and Monitoring Sleep.

Actors, use cases, and associations are interconnected and interact in one system (the mobile diabetes application), where each actor has different access rights in the system, and each use case will be associated with different actors or use cases according to the system that has been designed.

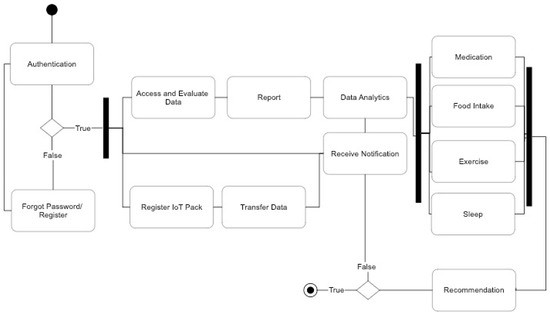

- Activity Diagram

Activity diagrams in the system (diabetes mobile application) are sequentially described in an algorithm, where each process is carried out in parallel from the start to the finish point. In the design of the diabetes mobile application activity diagram, it consists of (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Activity Diagram of User Activities.

- Start Point/Initial State;

- Activity (13 activities): Authentication, Forgot Password/Register, Access and Evaluate Data, Report, Data Analytics, Register IoT Pack, Transfer Data, Receive Notification, Medication, Food Intake, Exercise, Sleep, and Recommendation;

- Decision (two decisions): Decision After Activity (Authentication) and Decision after Activity (Recommendation);

- Synchronization (two forks, one join): Fork after Decision of Activity (Authentication), Fork After Activity (Data Analytics), and 1 Join After Activities (Medication, Food Intake, Exercise and Sleep);

- End state.

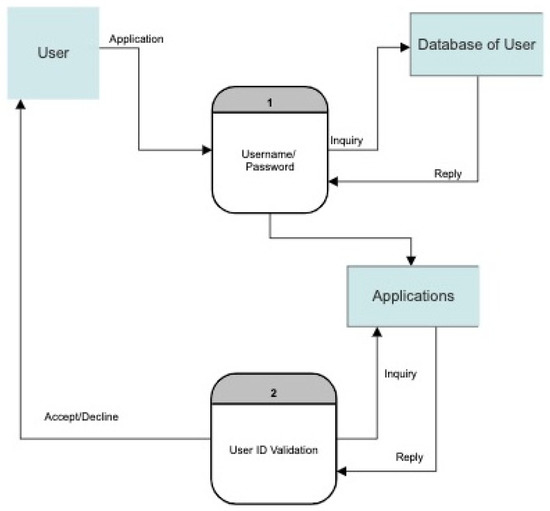

- Data Flow Diagram

The data flow diagram in the diabetes mobile application will describe the flow of data from the existing system in the application, where we can see the input and output of each process in the form of a design model consisting of (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Data Flow Diagram of User Registration.

- Functions (two Functions): Username/Password and User ID Validation;

- Input: User;

- Output: Application;

- File/Database: Database of User;

- Flow (seven Flows): Input (User) to Function (Username/Password), Function (Username/Password) to File/Database (Database of User), File/Database (Database of User) to Function (Username/Password), Function (Username/Password) to Output (Application), Output (Application) to Function (User ID Validation), Function (User ID Validation) to Output (Application), and Function (User ID Validation) to Input (User).

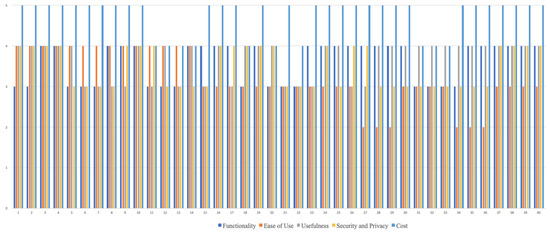

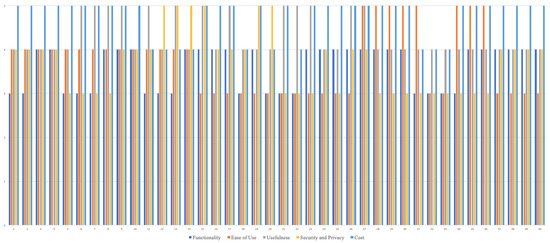

We analyze several factors that will be used as reference material for testing after the system (the diabetes mobile application) is implemented or used by the user after designing use case diagrams, activity diagrams, and data flow diagrams. We formulate five main trust factors (Table 10) in our proposed test, starting from the Functionality (Quality of Information, Core of Function, and Personalization), Ease of Use (User Interface Design and Efficiency), Usefulness, Security (Security and Privacy, Authentication) and Privacy and Costs. Figure 6 and Figure 7 and Table 11 and Table 12 show the results.

Table 10.

Trust Factors.

Figure 6.

User Trust Evaluation for the Mobile application Version 1.

Figure 7.

User Trust Evaluation for the Mobile application Version 2.

Table 11.

Demographic Results for Trust Evaluation of the Mobile Application Version 1.

Table 12.

Demographic Results for Trust Evaluation of the Mobile Application Version 2.

Researchers conducted an evaluation stage on the development of a diabetes mobile application for 40 participants who were users of mobile-based diabetes applications (diabetic patients). The user’s trust evaluation for mobile applications (Figure 7) adapts to five main trust factors (Table 10): functionality, ease of use, usefulness, security and privacy, and cost factors. The average value of each factor: functionality is 4.57; ease of use is 4.67; usefulness is 4.75; security and privacy are 5.0; cost is 4.70. The values as based on the results of the evaluation using a Likert scale of strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree with an assessment weight of 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. Based on the results of this evaluation, two indicators, namely the functionality and ease of use factors, have an evaluation with an input value of 3 (neutral). Table 13 describes the representations of the comparison between versions 1 and 2.

Table 13.

Mobile Application’s Feature Comparison.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The development of the type 2 diabetes mellitus mobile application at the development stage involves an operational feature that allows an application to run according to specified requirements. Testing is a very important stage and must be performed in software development. Tests must be carried out completely and thoroughly in order to cover all possibilities that may occur during the operation. Testing can demonstrate that the application meets the requirements and is error-free. If an error is found, it can be immediately corrected so that it can guarantee the quality of the software being developed. The testing design will boost application development success rates, allowing applications to be useful and optimally utilized by both patients and doctors involved in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Based on the trust evaluation results for mobile applications, we still need to update several indicators, specifically in terms of functionality and ease of use. Of course, this is a reference for us in developing this mobile-based diabetes application because the development of this application is still in the process of involving 40 participants who are diabetic patients. This study is also intended to serve as a reference for researchers who are currently conducting or will be conducting research in the field of developing type 2 diabetes mobile applications.

6. Future Work

Future work will aim to integrate our project mobile diabetes application with SmartPlate. In the future, through mobile diabetes applications and SmartPlate, patients and users with diabetes/non-diabetes can easily control their health through diet, activity, medication, and even control using a glucometer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information about materials and previous work can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/5/2006, https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/10/15/1820, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/1/8.

Author Contributions

S.R.J.: Evaluated project, methodology, investigation, resources, and supervision. W.A.: Developed software and evaluated functionality. J.-H.L.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. S.K.K.: Evaluation, testing, and analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by the “Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS)” through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (2022RIS-005). This study was conducted with the support of the Samcheok Culture Understanding Platform Project operated by the Sampyo Cement Social Contribution Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained within the article or in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sadhana, S.; Bandana, K.; Asgar, A.; Rajesh, Y.; Abhay, S.; Krishan, S.; Krishnan, H.; Girish, S. Mobile technology A tool for healthcare and a boon in pandemic. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Żarnowski, A.; Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Use of Mobile Apps and Wearables to Monitor Diet, Weight, and Physical Activity: A CrossSectional Survey of Adults in Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pititto, B.D.A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Paula, M.A.D.; Ferreira, G.C. BrazIliaN Type 1 & 2 DiabetEs Disease Registry (BINDER): Longitudinal, real-world study of diabetes mellitus control in Brazil. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthcare Diabetes Clin. Epidemol. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naydenova, G. An overview of existing methods for evaluating mobile applications to change user behavior. Int. Sci. J. Sci. Technol. Union Mech. Eng. 2022, 7, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kirloskar, M.M.; Bhagat, V.V.; Kodilkar, J.V.; Ketkar, M.S.; Vankudre, A.J. Prevalence of Stress Induced Hyperglycemia and Its Contributing Factors in Patients with Post Covid Mucormycosis—A Retrolective Study. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2022, 13, 926–931. [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio, L.A.; Molina, C.E.; Oram, R.A. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2019, 391, 2449–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu, M.D.; Malabu, U.H.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Mobile application intervention to promote self-management in insulin-requiring type 1 and type 2 diabetes individuals: Protocol for a mixed methods study and non-blinded randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachna, P.; Satish, R.K. Type 1 diabetes mellitus in pediatric age group A rising endemic. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Assaad, M.; Hekmat-Joo, N.; Hosry, J.; Kassem, A.; Itani, A.; Dahabra, L.; Yassine, A.A.; Zaidan, J.; El Sayegh, D. Insulin use in Type 2 diabetic patients: A predictive of mortality in COVID-19 infection. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Leburu, S.; Kulothungan, V. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment and Control of Diabetes in India from the Countrywide National NCD Monitoring Survey. J. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuland, E.V.; Dumitrescu, I.; Scheepmans, K.; Paquay, L.; Wandeler, E.D.; Vliegher, K.D. The Diabetes Team Dynamics Unraveled: A Qualitative Study. Diabetology 2022, 3, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajec, A.; Podkrajšek, K.; Tesovnik, T.; Šket, R.; Kern, B.; Bizjan, B.; Schweiger, D.; Kovac, J. Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes: Established Facts and New Insights. J. Genes 2022, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Więckowska, R.K.; Justyna, D.; Grażyna, D. The usefulness of the nutrition apps in self-control of diabetes mellitus—The review of literature and own experience. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 28, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apidechkul, T.; Chomchoei, C.; Upala, P. Epidemiology of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus among hill tribe adults in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, A.; Dubey, S.K. Usability Evaluation Methods: A Literature Review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2012, 4, 590–599. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Bastien, J.M. Usability testing: A review of some methodological andtechnical aspects of the method. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, e18–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgsson, M.; Staggers, N.; Weir, C. A Modified User-Oriented Heuristic Evaluation of a Mobile Health System for Diabetes Self-Management Support. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2016, 34, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Ikram, N.; Jallil, Z. Usability inspection: Novice crowd inspectors versus expert. J. Sytstems Softw. 2022, 183, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurni, J.; Alroobaea, R.; Alqahtani, M. Effect of User Sessions on the Heuristic Usability Method. Int. J. Open Source Softw. Process. 2018, 9, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Keenan, G.; Madandola, O.O.; Santos, F.C.D.; Macieira, T.G.R.; Bjarnadottir, R.I.; Priola, K.J.B.; Lpoez, K.D. Assessing the Usability of a Clinical Decision Support System: Heuristic Evaluation. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 10, e31758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.G.; Potrebny, T.; Larun, L.; Ciliska, D.; Olsen, N.R. Usability Methods and Attributes Reported in Usability Studies of Mobile Apps for Health Care Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2022, 8, e38259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banes, A. Development of App-Based E-Board Announcement System with SMS Support. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 15, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandesara, M.; Bodkhe, U.; Tanwar, S.; Alshehri, M.D.; Sharma, R.; Neagu, B.C.; Grigoras, G.; Raboaca, M.S. Design and Experience of Mobile Applications: A Pilot Survey. J. Math. 2022, 10, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.; Purwono, A.; Syahril. Android application development for push notification feature for Indonesian space weather service based on Google Cloud Messaging. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, K.; Iqbal, M.W.; Muhammad, H.A.B.; Fuzail, Z.; Ghafoor, Z.T.; Ahmad, S. Usability Evaluation of Mobile Banking Applications in Digital Business as Emerging Economy. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2022, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-H.; Park, J.-C.; Kim, S.-B. Therapeutic Exercise Platform for Type-2 Diabetic Mellitus. Electronics 2021, 10, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.C.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.-H. Self-Care IoT Platform for Diabetic Mellitus. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuria, J.; Peters, I.A.; Wabwoba, F. Determinants of University Students’ Perceived Usefulness of Mobile Apps. Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2022, 7, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, L.; Pourazad, N.; Michaelidou, N.; Tanusondjaja, A.; Harrigan, P. Marketing research on Mobile apps: Past, present and future. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Seo, Y.S.; Choi, J.H. Development and Effectiveness of a Smartphone Application for Clinical Practice Orientation. Int. J. Internet Broadcast. Commun. 2021, 13, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze, A.; Vanderschantz, N.; Timpany, C.; Cunningham, S.J.; Saravani, S.J.; Wilkinson, C. A Study of Mobile App Use for Teaching and Research in Higher Education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarry, A.; Rice, J.; O’Connor, E.M.; Tierney, A.C. Usage of Mobile Applications or Mobile Health Technology to Improve Diet Quality in Adults. J. Nutr. 2022, 14, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totten, A.M.; Womack, D.M.; Eden, K.B.; McDonagh, M.S.; Griffin, J.C.; Grusing, S.; Hersh, W.R. Telehealth: Mapping the Evidence for Patient Outcomes from Systematic Reviews. In AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Technical Briefs; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Joshua, S.R.; Mogea, T. Analysis and Design of Service Oriented Architecture Based in Public Senior High School Academic Information System. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering, Malang, Indonesia, 6–8 October 2017; pp. 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Alshaheen, R.; Tang, R. User Experience and Information Architecture of Selected National Library Websites: A Comparative Content Inventory, Heuristic Evaluation, and Usability Investigation. J. Web Librariansh. 2022, 16, 31–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).