Abstract

Zero-shot classification presents a challenge since it necessitates a model to categorize images belonging to classes it has not encountered during its training phase. Previous research in the field of remote sensing (RS) has explored this task by training image-based models on known RS classes and then attempting to predict the outcomes for unfamiliar classes. Despite these endeavors, the outcomes have proven to be less than satisfactory. In this paper, we propose an alternative approach that leverages vision-language models (VLMs), which have undergone pre-training to grasp the associations between general computer vision image-text pairs in diverse datasets. Specifically, our investigation focuses on thirteen VLMs derived from Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training (CLIP/Open-CLIP) with varying levels of parameter complexity. In our experiments, we ascertain the most suitable prompt for RS images to query the language capabilities of the VLM. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the accuracy of zero-shot classification, particularly when using large CLIP models, on three widely recognized RS scene datasets yields superior results compared to existing RS solutions.

1. Introduction

Scene classification is a fundamental research problem in remote sensing (RS) that involves automatically classifying remotely sensed data into different land cover or land use categories. This information is critical for a variety of applications, such as urban planning, agriculture, natural resource management, and disaster response. Scene classification is typically performed using a supervised learning approach, in which a model is trained on a labeled dataset of RS images along with their corresponding labels. Nevertheless, these models require a significant amount of labeled data for each RS class to be effective, which can be challenging to obtain in RS due to the time-consuming, expensive, and specialized nature of data collection.

To overcome this challenge, researchers have explored domain adaptation techniques to leverage the knowledge learned from a source domain with available data to a target domain in which the data is limited or unavailable [1]. More recently, researchers have explored new learning paradigms such as few-shot learning and zero-shot learning for RS scene classification [2]. Few-shot learning involves training a model on a small number of labeled samples, whereas zero-shot learning involves predicting the class of a new image into scene categories that were not observed during training. These approaches have shown the potential to reduce the need for large amounts of labeled data, expand the range of land cover or land use categories that can be classified, and improve the generalization performance of the model.

A common zero-shot learning technique is to leverage semantic information to enable the classification of new classes without requiring labeled training data, which can be useful in RS where new classes may emerge or existing classes may change over time. In this context, vision-language models such as CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training) can be used to learn the semantic relationship between the visual features of the images and the textual descriptions of the scene categories, enabling them to generalize to new categories without the need for explicit training on those categories. CLIP is trained on a large dataset of image-text pairs to associate natural language descriptions with visual concepts in a process known as contrastive learning. One of the key advantages of CLIP is its ability to generalize to new tasks and classes without the need for additional training, making it powerful and flexible enough to perform zero-shot learning. It is worth recalling that these models have been successfully applied to RS tasks related to RS image-text retrieval [3] and visual question answering [4,5].

This paper presents an extensive evaluation of large vision-language models, specifically CLIP models, for zero-shot scene classification in RS. In this study, we investigate the effectiveness of prompt engineering in enhancing the performance of these models by identifying the most effective prompts for zero-shot RS scene classification. The results of this investigation shed light on the potential of vision-language models and prompt engineering techniques for improving the accuracy of scene classification in RS imagery. In particular, the experimental results show impressive results on three well-known RS scene datasets by establishing new state-of-the-art zero-shot classification.

2. Related Work

In this section, we provide an overview of various works related to the fields of few-shot and zero-shot learning. One of the earliest studies by Li et al. [2] introduces a method that relies on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). They utilize the conditional Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) to produce image features. Given the challenges posed by RS images, which exhibit both inter-class similarity and intra-class diversity, they incorporate several constraints on the generator. These constraints include a classification loss to maintain discrimination between different classes, and a semantic regression component is employed to verify that the generated image features accurately reflect semantic attributes. Additionally, a class-prototype loss is introduced to encourage variation among the synthesized image features, preventing them from becoming excessively uniform.

The work proposed by [6] introduces Class Adapting Principal Directions (CAPDs) and an alignment process to transfer information from seen to unseen classes, incorporates automatic selection of useful seen classes, adapts to few-shot learning, and generalizes CAPDs to improve performance by using different learning scenarios. In contrast, the methodology in [7] involves leveraging deep learning and meta-learning techniques to address the challenge of classifying RS scenes with limited labeled data. The preliminary results of this methodology have been reported using various RS scene datasets, indicating its potential effectiveness in few-shot learning. Another approach by Yang et al. [8] focuses on scene image classification by constructing a new knowledge graph from scratch, specifically designed for RS data. They create a semantic representation of scene categories through representation learning. To achieve robust cross-modal matching between visual features and semantic representations, they propose a deep alignment network with a series of carefully designed optimization constraints. This network addresses both zero-shot and generalized zero-shot remote sensing image scene classification.

Xiang Li et al. [9] introduce a VLM approach for RS scene classification, enhancing feature representations and enabling improved zero-shot classification accuracy across multiple benchmark datasets. The authors in [10] highlight the vital role of few-shot learning in addressing the data scarcity issue in RS image interpretation, a domain greatly benefiting from deep learning. The study offers a comprehensive review, categorizes two key few-shot learning methods, and outlines three primary applications, complete with datasets and evaluation criteria. In [11], they address the challenge of few-shot classification by introducing an approach based on the Earth Mover’s Distance with spatial and channel attention modules.

Zhengwu Yuan [12] presents a solution for generating synthetic training data for overhead object detection in satellite imagery, addressing challenges in acquiring real data. The proposed solution demonstrates effectiveness in zero-shot and few-shot learning scenarios and provides insights into design parameters while making its implementation and experimental imagery details available for wider use.

Wang et al. [13] present a semantic autoencoder with distance constraints designed for the task of zero-shot classification in RS scenes. They develop a semantic autoencoder for known scene classes, aligning the visual and semantic spaces. To enhance the discriminative capability of this semantic autoencoder, they introduce a discriminative distance metric constraint, aiming to minimize distances between encoded vectors of samples from the same class and maximize distances between samples from different classes.

In a different study, Quan and co-authors [14] suggest a zero-shot technique that relies on Sammon embedding and spectral clustering. They employ a semi-supervised Sammon embedding algorithm to modify semantic space prototypes to better align with visual space prototypes, making it possible to synthesize unseen class prototypes effectively in the visual space. This allows for the use of a nearest-neighbor method with these unseen class prototypes to accomplish the classification task.

Li et al. [15] present a method for classifying RS scene images using the natural language processing model Word2Vec to map the names of seen and unseen scene classes to semantic vectors. They construct a semantic-directed graph based on these vectors to describe relationships between unseen and seen classes. Knowledge transfer from seen to unseen classes is facilitated through initial label predictions using an unsupervised domain adaptation model. A label-propagation algorithm, aided by the semantic-directed graph and initial predictions, is then employed for zero-shot scene classification. To mitigate noise in zero-shot classification results, a label refinement approach based on sparse learning is used, leveraging visual similarities among images within the same scene class.

Finally, Sumbul et al. [16] undertake a zero-shot investigation with a specific emphasis on fine-grained recognition of RS images. They create a matching function and illustrate the process of transferring knowledge to unfamiliar categories. However, it is noteworthy that most of these methods primarily revolve around devising visual-semantic embedding models that exclusively consider known classes. This limitation makes it challenging to ensure effective extension to unseen classes. Additionally, models trained solely on known data tend to misclassify unseen test instances into known categories, leading to a pronounced imbalanced classification problem.

3. RS Zero-Shot Classification

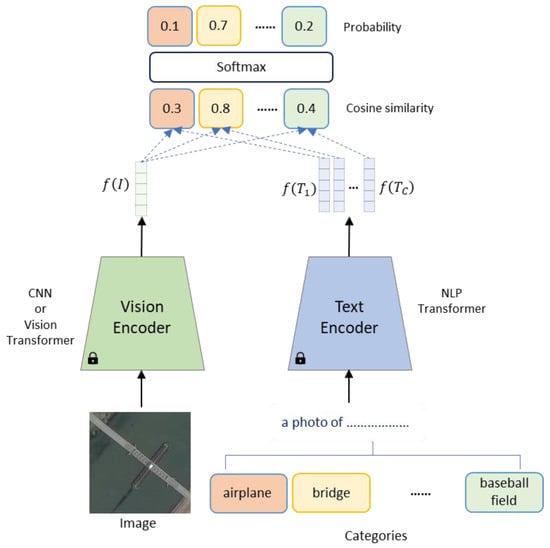

In zero-shot classification, we are given only a test set composed of images, where each image is The aim is to classify each into one of the following classes: As mentioned previously, we adopted the CLIP family of models for carrying out this task. CLIP is a vision-language model composed of image and text encoders. The text encoders are typically based on natural language processing (NLP) transformers, while the vision backbone is based on CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks) or vision transformers.

Figure 1 shows an overall view of the proposed zero-shot classification for RS imagery. Recall that we do not fine-tune these models at all on RS images; instead, they are frozen, and we use them directly for classification only. Typically, the model consists of a parallel vision and language encoders. The vision encoder embeds the test image (for simplicity, we remove the subscript j) into a visual feature . For the language encoder, we embed all class names present in the dataset into a set of textual features: . This is done by appending the name of the classes present in the dataset, for example, to a predefined prompt set in the CLIP model. For example, we append the name “airplane” to the prompt “a photo of”, yielding the prompt “a photo of an airplane”. Next, we feed this prompt to the language encoder to obtain the textual feature representation and compute the cosine similarity score between the image representation and all textual representations as follows:

where refers to the l2-norm.

Figure 1.

Zero-shot classification with CLIP/Open-CLIP Models.

Finally, we compute the probability for each class and assign the image to the class yielding the maximum probability:

Since RS images possess unique characteristics and are acquired from top-view satellites, we anticipate that utilizing more appropriate prompts can lead to improved results compared to the predefined prompt ‘a photo of’. In this regard, we employ alternative prompts outlined in Table 1, incorporating terms related to RS, scene, and top-view. Through our experiments, we demonstrate that utilizing these prompts can yield superior results when compared to the original prompt defined by CLIP.

Table 1.

Prompts used for the language model.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we present the experimental results for vision-language models for zero-shot classification of RS images. In Section 4.1, we describe the used dataset in addition to the experiment setup; in Section 4.2, we show the results; and finally, in Section 4.3, we compare our results against the SOTA.

4.1. Dataset Description and Experiments Setup

The Merced dataset comprises 21 categories of Earth scenes, each containing 100 RGB images. These images, acquired from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Map, have a ground resolution of 0.3 m and a size of 256 × 256 pixels [17]. Meanwhile, the AID dataset encompasses 10,000 RGB images sourced from Google Earth, with 30 scene classifications and a size of 600 × 600 pixels. The ground resolution for AID images varies from 0.5 to 8 m [18]. The NWPU-RESISC45 dataset consists of 31,500 RS images grouped into 45 categories, with each class containing 700 images extracted from Google Earth imagery. These images have a size of 256 × 256 pixels, and their spatial resolution ranges from 30 m to 0.2 m, with exceptions for certain classes [19]. Figure 2 displays samples from these three datasets, and Table 2 summarizes the class count and images per class.

Figure 2.

Examples from (a) Merced, (b) AID, and (c) NWPU datasets.

Table 2.

RS datasets used in the experiments: (A) general statistics and (B) names of classes.

To assess the proposed approach’s effectiveness, we conducted a set of experiments with all classes considered as unseen. Specifically, we regarded 21, 30, and 45 classes as unseen for the Merced, AID, and NWPU datasets, respectively.

In this study, we explored 13 distinct models based on CNNs and Transformers. We present the classification results in terms of overall accuracy (OA), representing the percentage of correct classifications relative to the total number of images in each dataset, along with class-specific accuracy.

The experiments were carried out using a computer with an Intel i9 processor, 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX GPU with 11 GB of memory.

4.2. Results

Table 3 shows the models investigated for zero-shot classification, while Table 4 shows the OA zero-shot accuracy produced by the different CLIP/Open-CLIP models on the three datasets. For Merced, the top three performing models for the six different prompt templates are xlm-roberta-large, ViT-H-14 from Open-CLIP, and ViT-H-14 from CLIP, with average accuracies of 77.00%, 72.00%, and 71.33%, respectively. For AID, xlm-roberta-large followed by RN50x64 from CLIP and ViT-H-14 from Open-CLIP exhibit the best behavior, yielding average accuracies of 68.33%, 62.33%, and 61.17%, respectively. For NWPU, ViT-H-14 from Open-CLIP yields the highest average accuracy with 66.83%, followed by convnext_large_d as well as from Open-CLIP and ViT-L-14 from CLIP with accuracies of 63.17% and 62.83%, respectively. However, we observe that xlm-roberta-large also yields an accuracy of 62.50%, which is very close to ViT-L-14 from CLIP. By averaging the results across the three datasets, we notice that the top three performing models are xlm-roberta-large, ViT-H-14 from Open-CLIP, and ViT-L-14 from CLIP, confirming the generalization ability of models with large parameters compared with models with a moderate or low number of parameters. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the confusion matrix for used datasets obtained by xlm-roberta-large and ViT-H-14.

Table 3.

Models investigated for zero-shot classification.

Table 4.

Zero-shot classification results for (A) Merced, (B) AID, and (C) NWPU datasets.

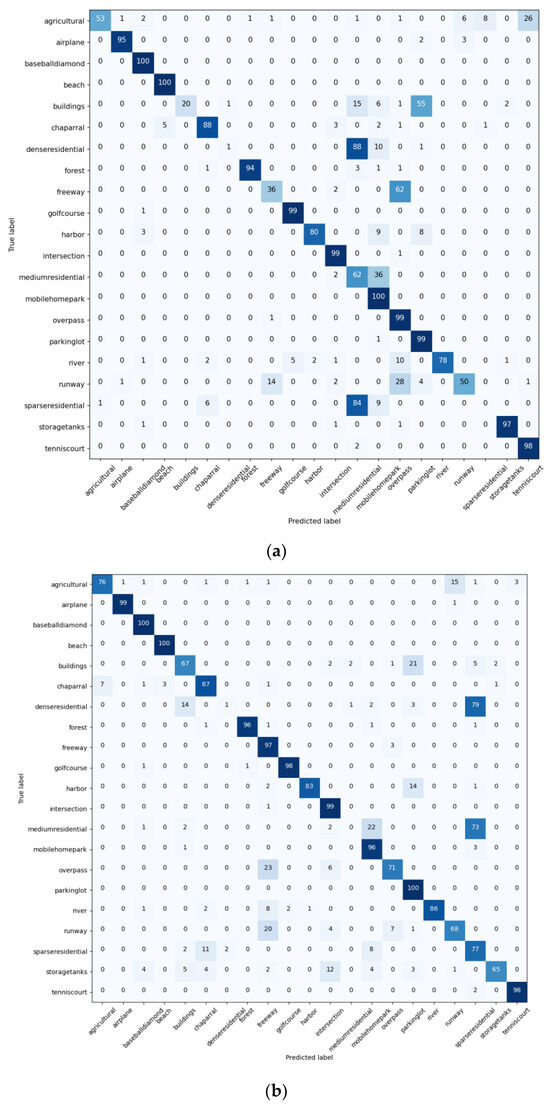

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix for (a) Merced dataset obtained by xlm-roberta-large (OA = 75%) and (b) ViT-H-14 (OA = 73%).

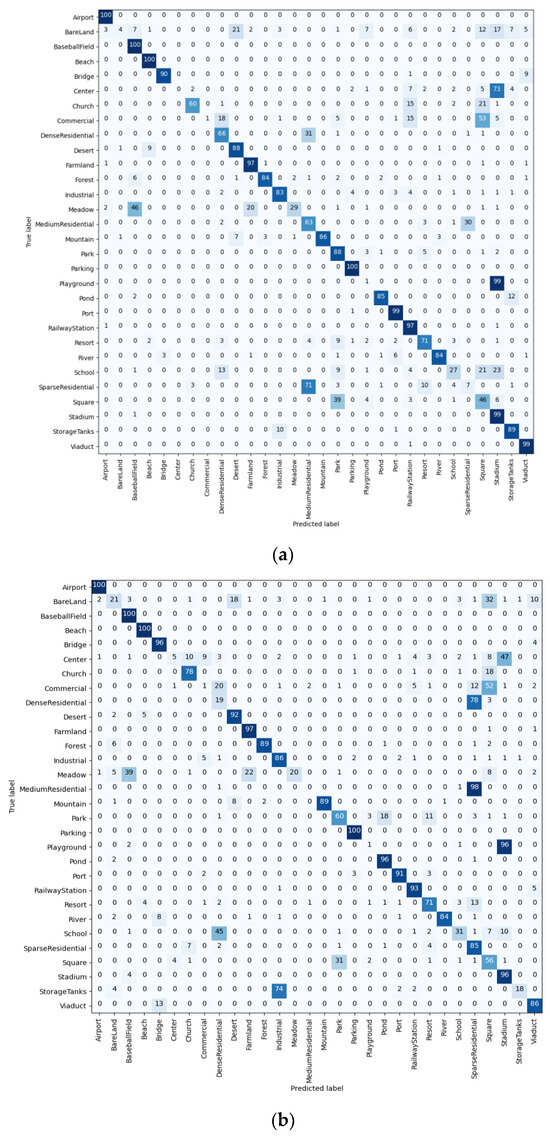

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix for (a) AID dataset obtained by xlm-roberta-large (OA = 70%) and (b) ViT-H-14 (OA = 73%).

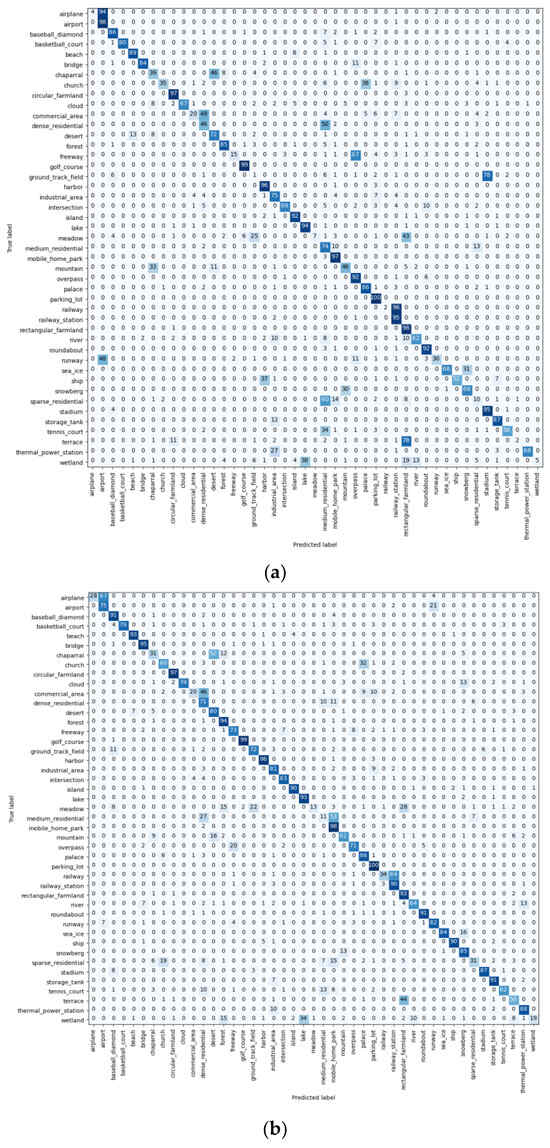

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix for (a) NWPU dataset obtained by xlm-roberta-large (OA = 66%) and (b) ViT-H-14 (OA = 72%).

The results presented in Table 1 shed light on the significance of employing RS-related terms in the prompts, which consistently yield higher accuracy compared to CLIP’s original prompt, “a photo of a <class_name>”. Notably, prompt template 5, “a satellite image of a <class_name>”, emerges as particularly effective, demonstrating slightly superior average accuracy across all three datasets.

On a conclusive note, the top-performing models across the three datasets are identified as xlm-roberta-large and ViT-H-14 from Open-CLIP. Specifically, for the Merced dataset, zero-shot overall accuracy (OA) reaches impressive levels of 75% and 73% (xlm-roberta-large and ViT-H-14). Likewise, for the AID dataset, the accuracies are notably high at 70% and 73%, and the NWPU dataset attains accuracies of 66% and 72%, further highlighting the robust performance of these models.

To delve deeper into the nuances of zero-shot classification at the class level, we provide a comprehensive view through confusion matrices for the Merced, AID, and NWPU datasets. These matrices depict the performance of both xlm-roberta-large and ViT-H-14, offering valuable insights. Remarkably, eleven classes in the Merced dataset, eleven in the AID dataset, and fifteen in the NWPU dataset achieved classification accuracy surpassing 90%.

Unveiling the challenges encountered, the Merced dataset exhibited particular difficulty in distinguishing sparse residential scenes, often misclassified as intersections, while dense residential scenes were sometimes confused with intersections or medium residential areas. Additionally, building classes were occasionally misinterpreted as parking lots.

In the AID dataset, complexities emerged with dense and sparse residential categories for xlm-roberta-large, while ViT-H-14 faced challenges with dense and medium residential classes. Within the NWPU dataset, xlm-roberta-large grappled with the identification of airplanes, ground track fields, and terrace scenes, while ViT-H-14 encountered hurdles with meadows and medium and sparse residential classes.

These findings underscore the remarkable capabilities of vision-language models (VLMs) in accurately classifying RS scenes despite their training in entirely distinct domains. Nevertheless, further enhancements in analyzing and interpreting these results can offer deeper insights into their implications and potential applications.

4.3. Comparison to Existing Solutions

In this section, we compare our results to the existing zero-shot solutions proposed for RS scenes. Examples of such methods include those based on stacked autoencoders and GANs. Table 5 shows the results for different unseen ratios for Merced, AID, and NWPU datasets. It is worth recalling that while existing solutions use the seen classes for learning, in our case, we do not use them at all. Instead, we simply classify the unseen classes using VLMs. The results provided in the tables clearly confirm the great capabilities of VLMs in performing zero-shot classification. VLMs significantly surpass the existing models and establish new state-of-the-art results for all three datasets. In addition, we observe that the larger the VLM, the better the obtained results. Indeed, these results show that larger VLMs learn more complex relationships between images and text pairs. This improved generalization ability is essential for zero-shot classification, as it allows VLMs to perform well on classes they have not seen during training.

Table 5.

Zero-shot classification accuracies with different unseen ratios. Unlike SOTA models, we use VLMs for classifying unseen classes without training on the classes considered as seen. (A) Merced, (B) AID, and (C) NWPU datasets.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented an approach to address the challenging task of zero-shot classification in RS. Previous solutions struggled to achieve satisfactory results when attempting to classify unseen classes using image-based models. In this study, we have introduced a novel strategy based on VLMs that have been pre-trained to understand the relationships between images and text. Specifically, we have explored thirteen VLMs derived from CLIP/Open-CLIP, each with varying parameter complexities. Through a series of experiments, we have identified that the prompt “a satellite image of + class_name” is the most effective prompt for RS images to query the language backbone of the CLIP model. The obtained results exhibit better compared to existing RS solutions on three well-known RS scene datasets. This research indicates a promising direction for improving zero-shot classification in the field of RS, leveraging the power of VLMs to enhance classification accuracy for unseen classes.

For future research, we propose focusing on fine-tuning VLMs, exploring different model architectures, and addressing challenges specific to temporal and multimodal data in addition to images with coarser resolution.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.M.A.R. and Y.B.; Software, Y.B.; Formal analysis, H.E.; Investigation, H.E.; Writing—original draft, M.Z.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD-2023R607), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available in Merced [17], NWPU-RESISC45 [18], and AID [19].

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project (RSPD-2023R607), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Othman, E.; Bazi, Y.; Melgani, F.; Alhichri, H.; Alajlan, N.; Zuair, M. Domain Adaptation Network for Cross-Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 4441–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Zhang, J. Generative Adversarial Networks for Zero-Shot Remote Sensing Scene Classification. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahhal, M.M.A.; Bazi, Y.; Alsharif, N.A.; Bashmal, L.; Alajlan, N.; Melgani, F. Multilanguage Transformer for Improved Text to Remote Sensing Image Retrieval. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9115–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, Y.; Rahhal, M.M.A.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Zuair, M.A.A.; Melgani, F. Bi-Modal Transformer-Based Approach for Visual Question Answering in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4708011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rahhal, M.M.; Bazi, Y.; Alsaleh, S.O.; Al-Razgan, M.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Al Zuair, M.; Alajlan, N. Open-Ended Remote Sensing Visual Question Answering with Transformers. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 6809–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Khan, S.; Porikli, F. A Unified Approach for Conventional Zero-Shot, Generalized Zero-Shot, and Few-Shot Learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 5652–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alajaji, D.A.; Alhichri, H. Few Shot Scene Classification in Remote Sensing Using Meta-Agnostic Machine. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th Conference on Data Science and Machine Learning Applications (CDMA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 4–5 March 2020; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L. Robust Deep Alignment Network with Remote Sensing Knowledge Graph for Zero-Shot and Generalized Zero-Shot Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, N. RS-CLIP: Zero Shot Remote Sensing Scene Classification via Contrastive Vision-Language Supervision. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Fu, K. Research Progress on Few-Shot Learning for Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 2387–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Huang, W. Multi-Attention DeepEMD for Few-Shot Learning in Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 9th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), Chongqing, China, 11–13 December 2020; Volume 9, pp. 1097–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, B.; Luo, X.; Bradbury, K.; Malof, J.M. SIMPL: Generating Synthetic Overhead Imagery to Address Custom Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Detection Problems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4386–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Peng, G.; De Baets, B. A Distance-Constrained Semantic Autoencoder for Zero-Shot Remote Sensing Scene Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 12545–12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Structural Alignment Based Zero-Shot Classification for Remote Sensing Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electronics and Communication Engineering (ICECE), Xi’an, China, 10–12 December 2018; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiang, T.; Wen, J.-R. Zero-Shot Scene Classification for High Spatial Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 4157–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbul, G.; Cinbis, R.G.; Aksoy, S. Fine-Grained Object Recognition and Zero-Shot Learning in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-Visual-Words and Spatial Extensions for Land-Use Classification. In Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 2–5 November 2010; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.; Hu, J.; Hu, F.; Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, X. AID: A Benchmark Data Set for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Benchmark and State of the Art. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Saligrama, V. Zero-Shot Learning via Semantic Similarity Embedding. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4166–4174. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Zero-Shot Recognition Using Dual Visual-Semantic Mapping Paths. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3279–3287. [Google Scholar]

- Kodirov, E.; Xiang, T.; Gong, S. Semantic Autoencoder for Zero-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3174–3183. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Yan, Y.; Chen, S.; Huang, X.; Wu, Q.; Ng, M.K. Joint Visual and Semantic Optimization for Zero-Shot Learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 215, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Lorenz, T.; Schiele, B.; Akata, Z. Feature Generating Networks for Zero-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 5542–5551. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, R.; Kumar, B.G.V.; Reid, I.; Carneiro, G. Multi-Modal Cycle-Consistent Generalized Zero-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).