Abstract

One of the reasons for the still prevailing concerns about the recycling of treated wastewater is the low efficiency of current Waste Water Treatment Plant (WWTP) technologies for removing Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCP) substances, especially pharmaceuticals. The goal of this investigation was to verify the behaviour of these substances after infiltration into the fluvial aquifer. During an experiment, this water (containing 45 PPCP substances) was infiltrated using a 10 m deep well for a period of one month. The whole process of infiltration was intensified by pumping at a well in a distance of 52 m. In the surrounding monitoring wells, 113 PPCP substances were monitored at three-day intervals with a detection limit in the order of tens of ng/L. The results showed that 32 PPCP substances were already present in the fluvial aquifer before the start of the infiltration experiment and thus represent “background” values. These substances are the result of river water seepage. The influence of infiltration was manifested by changes in the chemistry of the monitoring wells 8–12 days after the beginning of the experiment. The experiment demonstrated the high natural attenuation capacity of the fluvial aquifer, which eliminated a wide range of PPCP substances to a level below the detection limit.

1. Introduction, Motivation of the Experiment

In the last decade, Central Europe, including the Czech Republic, has increasingly been faced with the negative effects of drought [1,2,3]. In some regions, long-term drought has caused in extreme cases the drying up of rivers and a long-term drop in groundwater levels [4,5]. The related water management problems are manifested mainly in agriculture, but also in the supply of drinking water to the population [6].

One of the partial solutions is an approach used in Greece, Malta, Portugal, Italy, and Spain, where the share of reused urban effluent ranges between 1 and 12% [7]. Analysis carried out in preparation for the Water Reuse Regulation expected a provision cost for the reclaimed water of less than EUR 0.5 per m3 [8]. The current, relatively restrained attitude towards the reuse of treated waste water in Europe might be gradually mitigated [9]. The European Commission included wastewater in the circular economy action plan and set itself the goal of facilitating water reuse, especially in the field of irrigation [10]. Cleaned wastewater used for irrigation of crops that are not intended for direct human consumption can thus become an important tool for reducing demands on water resources in European agriculture.

The annual production of all WWTPs in the Czech Republic is 23 m3/s, i.e., 738 Million m3/year [11]. These water currently leave the territory of the state without any use in a short period of time. A more meaningful use of this water, for example by its infiltration and subsequent reuse, is prevented by current legislation. Primarily, waste water treatment plants must discharge their production into the receiving water in the river in the Czech Republic. Only in exceptional cases treated wastewater can be infiltrated into an aquifer, never directly into the saturated zone, but always through the soil layer.

One of the main reasons why today’s European public is so cautious about treated wastewater is the fear of discharging PPCPs into the groundwater. Today’s waste water cleaning technologies mostly remove these substances only with problematic efficiency [12,13,14]. The published results suggest that many PPCPs are released into the rivers in nanograms to micrograms per liter concentrations [15,16,17].

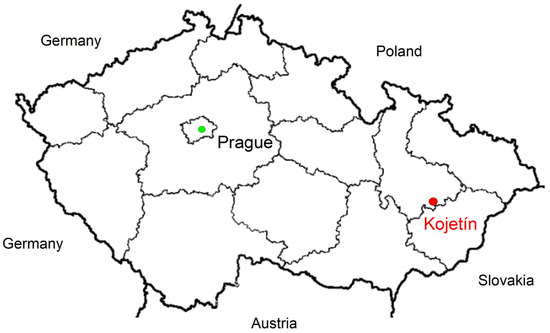

The main goal of the project was to provide expert documents that would confirm or, on the contrary, remove objections against the infiltration of treated wastewater into the fluvial quaternary and its possible reuse. The work focused primarily on clarifying the behavior of different types of PPCP substances, the speed of their spread and the possibility of natural attenuation. The tool for solving these questions was an experiment consisting in the infiltration of 2366 m3 of treated wastewater over into a fluvial sand-gravel and monitoring the behavior of 113 monitored PPCP substances at the test site Kojetín in South Moravia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the experimental site.

2. Natural Characteristics of the Experimental Site

The Kojetín area is located 220 km east of the capital of the Czech Republic, Prague. Climatically, the area is slightly warmer and drier than the national average (average annual temperature in Kojetín (1961–2019) is 8.9 °C, in the Czech Republic 7.8 °C; average precipitation in Kojetín is 660 mm, in the Czech Republic 675 mm). Over the past 60 years, the average annual temperature in the Czech Republic has risen by 2 °C. Regarding precipitation, no significant trends have been observed. The nationwide long-term average of precipitation over the last sixty years is stable, only the course of precipitation changes during the year. Increased temperatures, especially in the summer months, result in high evapotranspiration, which is manifested by a decrease in river flows [18,19].

Kojetín experimental site is located on the right bank of the most important watercourse in the eastern part of the Republic, the Morava River. In 2022, only 45% of the long-term monthly flow (which is ca. 47 m3/s) flowed through the Morava River in Kojetín.

Morphologically, the Kojetín area is part of a floodplain with an altitude of around 190 m a.s.l. Geological and hydrogeological conditions are relatively simple. The uppermost zone is represented by flood clays with low permeability, causing the artesian regime of the underlying Quaternary aquifer. This aquifer of fluvial gravel-sands have a thickness of 2.6 to 6 m, and is characterized by an average hydraulic conductivity value of 7.8 × 10−4 m/s and is in close hydraulic connection with the adjacent watercourse of the Morava River. The subsoil of the fluvial Quaternary is represented by Tertiary clays, which form an lower impermeable layer.

3. Experimental Setup and Performance

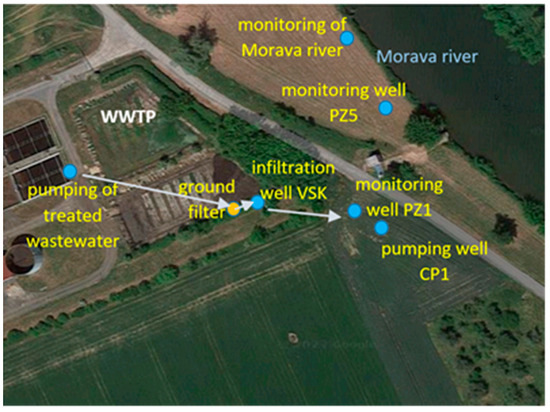

The area of interest was equipped with observation wells PZ1, PZ5, and CP1 (Figure 2). A well VSK was used for infiltration of treated wastewater from the local WWTP. All wells penetrated the entire thickness of the aquifer. The depth of the wells was between 8 and 10 m, depending on the thickness of the fluvial Quaternary. The casing diameter of pumping/infiltration wells CP1, CP5 and VSK was 425 mm, in the case of monitoring wells PZ1 and PZ13 the diameter was 273 mm. Length of casing again depended on local lithological conditions and was most often in the range of 2–7 m.

Figure 2.

Location of pumping (CP1), monitoring (PZ1 and PZ5), and infiltration wells (VSK) at the Kojetín experimental site (blue points—wells, yellow point—ground filter)

Special attention was paid to monitoring the expected clogging of the VSK infiltration well, which was equipped with a casing observation probe Solinst for this purpose. The probe worked on the principle of measuring barometric pressure and was placed in a pipe in the filter material of the well.

The level in the Morava River is maintained by manipulation at the weir at 190.9 m a.s.l. The levels in the wells VSK, CP1, PZ1 in the original artesian regime are at the level of 190.6 m a.s.l.

Czech legislation does not allow the discharge of wastewater into groundwater, but always through the unsaturated zone. Therefore, a container with a volume of 1 m3 filled with fine-grained sand (its granulometry was very similar to the unsaturated zone) was placed between the outlet of the WWTP and the infiltration VSK well.

A slug test was performed before the major infiltration experiment conducted with clean water. The goal was to specify the infiltration rate into the VSK well. The water level measurement took 5.5 h. At one time, the borehole was filled with 212 L of water and the decrease in its level over time was measured. The test was evaluated using the Jacob-Lohman method [20].

The initial amount of infiltrated wastewater was set at 2 L/s and then adjusted so that the level in the VSK well was constant. Due to clogging, the infiltration rate in VSK well gradually decreased from 1.8 L/s to 0.7 L/s.

The infiltration was intensified by pumping from adjacent well CP1. The withdrawal from well CP1 was therefore maintained systematic greater than the infiltration rate. The pumped volume of groundwater from CP1 well ranged from 2.9 L/s to 1.6 L/s. During the experiment, 2366 m3 of treated wastewater was infiltrated into VSK well, and 4332 m3 of groundwater was pumped from CP1 well.

Water samples were taken at scheduled intervals from five monitoring points—the inlet into VSK well with treated wastewater, CP1 well, PZ5 and PZ1 wells, and Morava River for a period of 36 days. A total of 113 PPCP substances were analyzed.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Qualitative Changes

Table 1 provides a complete overview of the occurrence of PPCP substances at the monitoring points in the period before and during the infiltration experiment. For substances that were analyzed in more detail, the mean and median content values are also given.

Table 1.

Information on the presence of PPCP substances at monitoring objects (black fields—values above the detection limit, white fields of values below the detection limit, green period “background” data before the experiment, yellow period data during the experiment).

A comparison of both recipients of PPCPs (i.e., treated wastewater from the WWTP and water in the Morava River) reveals their similarity in terms of the range of detected components. Upstream from the Kojetín site, many other wastewater treatment plants are connected to Morava River. A total of 80 PPCP substances with values above the detection limit appeared in at least one sample on the monitored objects.

The permanent occurrence (that is, they were detected in all samples) exhibited 45 PPCP substances concerning treated wastewater and 32 substances concerning water in the Morava River. At the beginning of the VSK infiltration experiment (7 November 2022), well PZ5 already contained 29 PPCP substances, whilst wells CP1 and PZ1 contained 13 resp. 12 substances. The PZ5 well is located in the proximity of the Morava River (Figure 2). It follows that the river water negatively affects the adjacent fluvial aquifer and a non-negligible set of PPCP substances is “naturally” present in the groundwater unaffected by the infiltration experiment. During floods and due to the dam cascade, influent conditions exist occasionally or permanently in some of areas between the aquifer and the Morava River. This causes the PPCP to transport from the river into fluvial sediments.

The presence of more or less similar PPCP substances both in the river and in the outlet from the WWTP is not surprising; especially in times of low flows, inflows from treatment plants represent a non-negligible part of the flow of watercourses in Europe. This fact is documented by comparing the contents of PPCP substances in some Central European (CE) rivers (see Table 2). The water quality in the Morava River in terms of the range of detected PPCP substances fits very well into this regional context; in absolute values the contents of some substances are even significantly higher (e.g., Oxypurinol, Iopromide, Telmisartan).

Table 2.

PPCPs occurrence in six watercourses in CE region (The colour indicates the frequency of occurrence: red in all rivers; orange—the substance was missing in one of the streams; yellow—the substance was missing in two streams; green—the substance was missing in three rivers [21].

Despite the presence of more or less identical substances, large quantitative differences occur between the outlet of WWTP and the Morava River. The highest average concentration in treated wastewater was exhibited by Oxypurinol (13,903 ng/L; Table 1). However, such high difference in content are not always usual. For the other eight substances, average content was higher than 1 µg/L; these were Valsartan acid, Lamotrigine, Diclofenac, Telmisartan, Tramadol, Benzotriazole, Hydrochlorothiazide, and Sucralose. All these substances can also be found in river water, but in lower orders of magnitude—due to the dilution, degradation, or gradual transformation into others. However, such high differences in content are not always a general rule. In Table 1, the group of substances occur where the differences in PPCP content are smaller, or negligible, between the WWTP outlet and river Morava. These are, for example, 4-formylaminoantipyrine, Gabapentin, or Valsartan; the content of Metformin is more or less equal, with Acesulfame even more in the river water than in the WWTP discharge.

The data from Table 1 also shows the significant role of infiltrated water from the Morava River: the adjacent well PZ5 contained a significantly more varied range of PPCP substances before the start of the infiltration experiment than wells CP1 and PZ1 further from the river. The effect of the infiltration of treated wastewater in the VSK well was evidently not manifested in the PZ5 well.

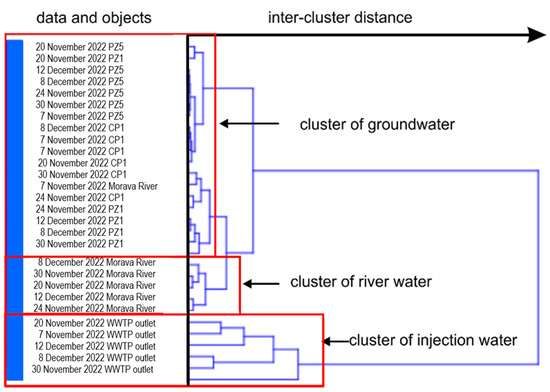

4.2. Cluster Analysis

Changes in groundwater chemistry in wells PZ1 and CP1 due to the infiltration of treated groundwater into the VSK well was confirmed by statistical processing using cluster analysis. Cluster analysis is one of the methods that deal with investigating the similarity of multidimensional objects and classifying them into classes. It allows assessment of the relationships between individual clusters.

In the case of the implemented experiment, 30 chemical analyzes of water for PPCP substances were available, each of these contained a determination of the content of 113 substances (matrix of 30 × 113 elements). Cluster analysis focused on:

- the number of clusters of PPCP substances—i.e., substances belonging to one set;

- a measurable degree of difference in the occurrence of pharmaceuticals between individual observation objects.

The graphical output of this analysis is a dendrogram which allows measurable evaluation of the difference in the framework of the entire data matrix. The differences between groundwater, Morava river water, and infiltrated water during the whole experiment are documented in Figure 3. The difference of individual clusters is determined by the so-called inter-cluster distance. The measure expressing the probability of agreement of the created distribution of objects into individual groups is the cophenetics correlation coefficient (CP). The value of cophenetics coefficient was CP = 0.906.

Figure 3.

Results of cluster analysis documenting the relationships between monitored parameters.

The results showed that the groundwater in wells PZ1, CP1, and PZ5 was significantly different from the output from the WWTP and mostly from the Morava River throughout the experiment. The water in Morava River is significantly more “related” to groundwater than water from the WWTP. As a result of infiltration into the VSK well, the difference between the infiltrated water from the WWTP and groundwater has decreased. This statistically confirmed the change in groundwater quality due to infiltrated water originating from the WWTP.

4.3. Characterization of the Transport Process

The transport of PPCPs from the VSK infiltration well to the PZ1, CP1, or PZ5 boreholes can be demonstrated based on increases in the content of PPCP substances. Temporal changes in content enable the approximate assessment of transport rates. The most obvious markers are potentially those substances which did not occur in monitoring wells at the beginning of the experiment, but appeared later. The focus was on substances that, could be used as tracers due to their physical and chemical properties. Such non-degrading and non-sorbing substances migrate in the rock environment at the same speed as groundwater flows—i.e., without retardation. Oxypurinol and Benzotriazole were supposed to be in this category.

A comparison of both substances reveals that their content are significantly higher in treated wastewater than in the Morava river (Table 3 and Table 4). In well PZ5, the content of both pharmaceuticals were already present before the start of the infiltration experiment and remained more or less stable during the entire test, or there was no fundamental fluctuation. Neither Benzotriazole nor Oxypurinol was present in the CP1 and PZ1 boreholes before the start of the infiltration test. Both substances appeared in these objects with a delay of 8–12 days from the start of the experiment and had an upward trend. The values given correspond to velocities of 6.6–4.4 m/day. The distance between VSK and CP1 wells is 52.5 m. In the context of objectivity, it is necessary to emphasize that the calculated mentioned transport rates are not natural, but influenced by pumping in well CP1.

Table 3.

Time development of Benzotriazole content at monitored objects.

Table 4.

Time development of Oxypurinol content at monitored objects.

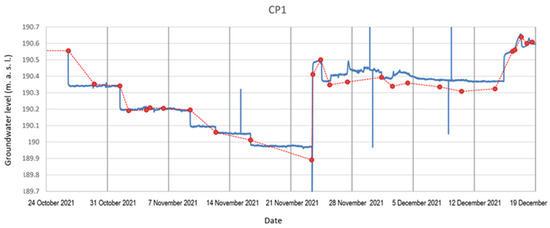

4.4. Evaluation of Groundwater Flow Velocities and Clogging

All the hydraulic experiments conducted at Kojetín experimental site, including several pumping tests and VSK infiltration, were analysed using MODGLOW-USG software [22]. Inflow tests were carried out in the period 26 October 2021–16 December 2021 (length 52 days). The CP wells and the VSK well are 50 and 80 m from Morava, respectively. After the completion of the pumping of the CP1 and CP2 wells and at the end of the period, short recovery tests were carried out. The maximum withdrawal reached in the final phase of inflow tests, when pumping the VSK well, was 4 L/s. For well CP1, the value of hydraulic conductivity kf was determined in the range of 1.3 × 10−3–1.8 × 10−3 m/s, for well CP2 in the range of 1.3 × 10−3–1.8 × 10−3 m/s and for well VSK in the range of 9.1 × 10−4–1.2 × 10−3 m/s.

The model simulations described the period of inflow tests at wells CP1, CP2 and VSK. Model calibration consisted in optimizing the agreement between measured and simulated groundwater levels. The agreement of the model and measurements was achieved by a combination of manual and semi-automatic tuning of selected hydraulic parameters of the model. The model simulation faithfully affected the observed development of the levels, including the tested wells. The withdrawals were simulated using the Neuman boundary condition (the pumped amount of groundwater was entered) and the groundwater level in the pumped wells was calculated by the model (see example Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of measured and modeled groundwater levels, pumped borehole CP1. blue line—measured data, red points and line—simulated data.

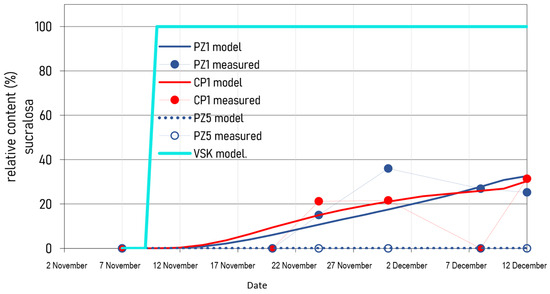

The transport of non-sorbing, non-reacting PPCPs from VSK well was simulated too. Figure 5 demonstrate the example of simulation of Sucralose content.

Figure 5.

Measured and modelled content of Sucralose in 2022, relative values.

The best agreement between measurement and model result was achieved with the aquifer porosity of 15%, which is the expected value when considering a fluvial aquifer. In accordance with the measurement, the model also predicted that the locality of the PZ5 well remained unaffected by transport from the VSK well.

Model calculated breakthrough time (3–5 days) is shorter than observed (8–12 days), even though the model longitudinal dispersivity was reduced to 1 m to minimise dispersion. This suggests that during the initial phase of the transport process, sucralose was degraded. The same process probably took place which caused the initial content of this substance to be zero. We repeated the same experiments and calculations for oxypurinol and benzotriazole with practically identical results.

Clogging of the VSK borehole was manifested by a huge difference in groundwater level response during the pumping and infiltration period. Throughout the proceeding pumping test, the water level in the VSK well decreased by 1 m, when 4 L/s were abstracted. The infiltration experiment was finished with the recharge rate of approximately 0.7 L/s and the water level increased by 4 m. The level difference between the VSK borehole and the casing observation probe increased too. The reason is the position of the observation probe in a pipe in the filter material of the well.

The persistently relatively small level difference between the infiltration well and the casing probe proves that the hydraulic resistance against infiltration arose only at the filter pack/aquifer interface. It is likely that physico-chemical processes caused by the seepage of oxygenated water into the originally anoxic environment, in combination with microbiological processes and sorption to precipitated Fe3+ compounds, contributed significantly to the clogging. It is evident from the obtained data that the artificial recharge of wastewater using the technology of infiltration wells will bring technical problems associated with a decrease in yield.

4.5. Generalization of PPCP Substance Behaviour

The results of the infiltration experiment at the Kojetín site enable PPCP substances to be divided into four groups

- Substances with random occurrence in very low concentrations and therefore with an undetectable origin.

At the WWTP outlet, the substances of this group often had concentrations below the detection limit, so the infiltration experiment could not affect the concentrations of these substances in the monitoring wells PZ1, CP1 and PZ5. Nevertheless, they were analyzed in low concentrations at irregular intervals in some samples. An example of this group of substances is caffeine, which was detected in well PZ1 in the sample from 20 November and in well CP1 in the sample from 30 November. However, during the entire experiment, caffeine was not detected in the WWTP water samples. A similar result can be observed with other substances such as Bisphenol S, Methylparaben, Paracetamol, Paraxanthine, Propylparaben, and Saccharin. The problem with these substances is their general presence in various components of the environment, including practically all watercourses, so their origin is difficult to unambiguously detect.

- Substances, the contents of which increased in the Quaternary aquifer after the infiltration experiment.

Substances of this group are characterized by a high concentration in treated wastewater, which was later manifested in the occurrence in wells PZ1 and CP1. It is important that these substances were not present in the wells before the start of the experiment. The resulting content of these substances in the wells remain lower than at the WWTP outlet. Characteristic representatives of this group are oxypurinol, Sucralose, Hydrochlorothiazide, Diclofenac-4-hydroxy, and Benzotriazole. But all the substances which systematically occurred during the infiltration experiment should be included (Table 2). Absence of these substances at the beginning of the experiment reveals that they are degrading at some rate in the groundwater.

- Substances persistent, apparently without significant WWTP influence

Substances in this group are characterized by a higher concentration in wells than in treated wastewater. They usually occurred in the groundwater from the beginning of the infiltration experiment. The water in the observed wells was therefore more similar to water from the Morava River than to the WWTP. A typical representative is Acesulfame, whose concentrations in the river exceeded twice the average values of the water leaving the WWTP. This group also includes DEET and Sulfamethazine, which are all persistent substances that are not subject to degradation either in the Morava River or in the rock environment of the gravel sands of the experimental site.

- Substances with a high natural attenuation capacity.

Substances in this group are characterized by concentrations above the detection limit in the water leaving the WWTP, possibly also in the Morava River. Nevertheless, these substances were not detected in the observation wells. It can be assumed that these substances have a good sorption/degradation capability in the rock environment. This is a relatively large group of substances that includes Acebutolol, Atenolol, Azithromycin, Benzotriazole 1-methyl, Bisoprolol, Celiprolol, Cetirizine, Citalopram, Clarithromycin, Climbazole, Clindamycin, Cyclophosphamide, Erythromycin, Fexofenadine, Fluconazole, Irbesartan, Carbamazepine-2-hydr., Carbamazepine-DHH, Carbamazepine-E, Lamotrigine, Iosartan, Metoprolol, Mirtazapine, Naproxen, Naproxen-O-desmeth, Oxcarbazepine, PFOS, Sertraline, Sitagliptin, Sotalol, Sulfamethoxazole, Telmisartan, Tramadol, Trimethoprim, Venlafaxine, Venlafaxine O-desmet, Verapamil, and Warfarin.

5. Conclusions

- An experiment consisting of the gradual infiltration of 2366 m3 of treated wastewater over a period of 36 days into a fluvial sand-gravel aquifer demonstrated a diverse influence on the quality of groundwater. Of the 113 monitored PPCP substances, 80 were detected at the experimental site, of which 69 were in the WWTP discharge.

- Groundwater contained a non-negligible range of PPCP substances even before the start of the experiment (PZ1 12 substances, CP1 11 substances and PZ5 17 substances), which represent “background” values. The source of these, mainly pharmaceuticals, is bank infiltration from the Morava River. River water contains a similar range of PPCP substances as WWTP discharge, although mostly in much lower concentrations.

- The influence of infiltration into the VSK infiltration well was manifested by changes in chemistry about 50 m away with a delay of 8–12 days.

- Of the monitored PPCP substances present in WWTP discharge, roughly half did not appear in the groundwater at all. It shows the selectively high degree of natural attenuation of the fluvial gravel sand sediments for some substances.

- On the other hand, a group of substances such Oxypurinol or Benzotriazole, which are often contained in treated wastewater in concentrations of the order of thousands of ng/L, migrated with groundwater, despite the fact that they were not detected as background values. Probably some degree of degradation of these occurred in the aquifer.

- Due to the lack of long-term medical studies that would document the possible negative impact of the detected substances on human health, the only option is to use the precautionary principle. Until a more efficient wastewater treatment technology is applied, it is clear that, despite the very good attenuation capacity of the rock environment for some substances, the infiltration of treated wastewater remains a problematic issue.

- However, this depends on the purpose for which the infiltration technology would be used. Both surface and shallow groundwater (in some places) in Central Europe already contain a non-negligible amount of PPCP substances. Therefore, in regions suffering from a lack of water for agricultural purposes, it would be possible potentially to infiltrate WWTP output into groundwater in accordance with current Czech legislation. After purification, these newly generated sources of groundwater could be used for irrigation in the event of a lack of another water source.

Author Contributions

Z.H. and F.P. prepared the manuscript and approved the manuscript, including graphical and statistical interpretations. Z.H. was responsible for the overall coordination of the research and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was completed with support from the project “Water retention in the landscape using artificial recharge as a tool in the fight against drought”. This project has received funding from the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic, SS—Programme of applied research, experimental development and environmental innovation SS01020275.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available through the T.G. Masaryk Water Research Institute, Prague.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brázdil, R.; Trnka, M.; Mikšovský, J.; Tolasz, R.; Dobrovolný, P.; Řezníčková, L.; Dolák, L. Drought events in the Czech Republic: Past, present, future. In Proceedings of the 19th EGU General Assembly, EGU2017, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2017; p. 19285. [Google Scholar]

- Brázdil, R.; Trnka, M.; Dobrovolný, P.; Chromá, K.; Hlavinka, P.; Žalud, Z. Variability of droughts in the Czech Republic, 1881–2006. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2008, 97, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásny, T.; Mátyás, C.; Seidl, R.; Kulla, L.; Merganičová, K.; Trombik, J.; Dobor, L.; Barcza, Z.; Konôpka, B. Climate change increases the drought risk in Central European forests: What are the options for adaptation? Cent. Eur. For. J. 2014, 60, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyncl, M.; Heviankova, S.; Nguien, T.L.C. Study of supply of drinking water in dry seasons in the Czech Republic. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 92, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavíková, L.; Malý, V.; Rost, M. Impacts of Climate Variables on Residential Water Consumption in the Czech Republic. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potop, V.; Türkott, L.; Kožnarová, V. Drought episodes in the Czech Republic and their potential effects in agriculture. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2010, 99, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Waterbase—UWWTD: Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive—Reported Data. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/waterbase-uwwtd-urban-waste-water-treatment-directive-7 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- EC Commission Staff Working Document, Executive Summary of the Impact Assessment Accompanying the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Minimum Requirements for Water Reuse (COM(2018) 337 Final of 28 May 2015). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/pdf/water_reuse_regulation_impact_assessment_summary.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- EU Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020 on Minimum Requirements for Water Reuse. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020R0741&from=EN (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Alcalde-Sanz, L.; Gawlik, B.M. Minimum Quality Requirements for Water Reuse in Agricultural Irrigation and Aquifer Recharge—Towards a Water Reuse Regulatory Instrument at EU Level, EUR 28962 EN, 2018; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hrkal, Z.; Harstadt, K.; Rozman, D.; Těšitel, T.; Kušová, D.; Novotná, E.; Váňa, V. Socio-economic impacts of the pharmaceuticals detection and activated carbon treatment technology in water management—An example from the Czech Republic. Water Environ. J. 2019, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulton, R.L.; Kohn, T.; Cwiertny, D.M. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in effluent matrices: A survey of transformation and removal during wastewater treatment and implications for wastewater management. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 1956–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, B.D.; Crago, J.P.; Hedman, C.J.; Magruder, C.; Royer, L.S.; Treguer, R.F.J.; Klaper, R.D. Evaluation of a model for the removal of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and hormones from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J.D.; Furlong, E.T.; Burkhardt, M.R.; Kolpin, D.; Anderson, L.G. Determination of pharmaceutical compounds in surface- and ground-water samples by solid-phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1041, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.P.; Chu, K.H. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and personal care products along the West Prong Little Pigeon River in east Tennessee, USA. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Helm, P.A.; Metcalfe, C.D. Sampling in the Great Lakes for pharmaceutical, personal care products, and endcrine-disrupting substances using the passive polar organic chemical integrative sampler. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brázdil, R.; Zahradníček, P.; Dobrovolný, P.; Štěpánek, P.; Miroslav Trnka, M. Observed changes in precipitation during recent warming: The Czech Republic, 1961–2019. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 3881–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, R.; Chromá, K.; Dobrovolný, P.; Tolasz, R. Climate fluctuations in the Czech Republic during the period 1961–2005. Int. J. Climatol. 2009, 29, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.E.; Lohman, S.W. Nonsteady flow to a well of constant drawdown in an extensive aquifer. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1952, 33, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrkal, Z.; Reberski, J.L.; Selak, A. (Eds.) Board for Detection and Assessment of Pharmaceutical Drug Residues in Drinking Water—Capacity Building for Water Management in CE; MONOGRAPH of the boDEREC-CE Project; Croatian Geological Survey: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, S.; Langengevin, C.D.; Niswonger, R.G.; Ibaraki, M.; Hughes, J.D. MODFLOW–USG Version 1: An Unstructured Grid Version of MODFLOW for Simulating Groundwater Flow and Tightly Coupled Processes Using a Control Volume Finite-Difference Formulation; U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods: Louisville, KY, USA, 2013; Chapter A45; 66p.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).