Abstract

The advancement of the Internet has changed people’s ways of expressing and sharing their views with the world. Moreover, user-generated content has become a primary guide for customer purchasing decisions. Therefore, motivated by commercial interest, some sellers have started manipulating Internet ratings by writing false positive reviews to encourage the sale of their goods and writing false negative reviews to discredit competitors. These reviews are generally referred to as deceptive reviews. Deceptive reviews mislead customers in purchasing goods that are inconsistent with online information and thus obstruct fair competition among businesses. To protect the right of consumers and sellers, an effective method is required to automate the detection of misleading reviews. Previously developed methods of translating text into feature vectors usually fail to interpret polysemous words, which leads to such functions being obstructed. By using dynamic feature vectors, the present study developed several misleading review-detection models for the Chinese language. The developed models were then compared with the standard detection-efficiency models. The deceptive reviews collected from various online forums in Taiwan by previous studies were used to test the models. The results showed that the models proposed in this study can achieve 0.92 in terms of precision, 0.91 in terms of recall, and 0.91 in terms of F1-score. The improvement rate of our proposal is higher than 20%. Accordingly, we prove that our proposal demonstrated improved performance in detecting misleading reviews, and the models based on dynamic feature vectors were capable of more accurately capturing semantic terms than the conventional models based on the static feature vectors, thereby enhancing effectiveness.

1. Introduction

With the development of the Internet, e-commerce platforms have become the mainstream method for consumers to purchase products. Therefore, purchasing goods on the Internet, rather than in physical stores, has become an increasingly popular preference for consumers. However, because consumers do not have direct physical access to the goods, they rely on online product reviews to overcome information asymmetry in their purchasing decisions [1]. These reviews enhance the product value as a key consumer reference. A 2018 study [2] found that 82% of consumers believed that product reviews influenced their purchase decisions. For sellers, product reviews are a method of online marketing whereby positive reviews facilitate sales while negative reviews hinder sales, as demonstrated in a 2013 study [3].

By capitalizing on the business potential found in customer feedback, some sellers started writing false positive reviews to boost their credibility or write false negative reviews to discredit rivals. This practice, which is known as “deceptive reviews,” can be found both in Taiwan and other countries. In 2013, Samsung Taiwan was criticized for publishing “fake reviews” [4]. Samsung was found to ask its employees to write favorable reviews on Samsung cellphones and negative reviews on the products of its competitor HTC in Taiwan’s largest lifestyle and product forum website Mobile01.com (accessed on 22 March 2022). In another example, the TripAdvisor annual review report in 2019 [5] revealed that out of 60 million reviews, 1.38 million were deceptive. Because deceptive reviews provide false information that misleads consumers and intensifies vicious rivalry among sellers, effective methods of detecting such reviews are necessary.

The use of machine learning and deep learning to identify deceptive reviews has been explored in past studies [6,7,8,9]. One of the disadvantages highlighted in the literature is that classification in machine learning relies on prior knowledge of experts, which limits the classification efficiency of the model on features selected by experts. Although deep learning does not rely on the prior knowledge of experts, the method encounters a bottleneck when used to interpret texts because of the use of polysemous terms, which results in two current challenges when detecting deceptive reviews. First, a difficulty exists in deciphering polysemous words. For example, the word “蘋果 (apple)” in the sentences “蘋果很好吃 (Apples are delicious)” and “我買了蘋果手機 (I bought an Apple iPhone)” conveys different meanings. In the first sentence “apple” refers to the fruit, whereas in the second sentence, Apple refers to a brand. However, in both situations, the word “蘋果 (apple)” is represented by the same set of word vectors. Second, because of the high costs and low efficiency in manually labeling deceptive reviews, pre-labeled datasets are generally unavailable. In addition, because of the substantial differences between the proportion of real and deceptive reviews in dataset samples, the training process would likely be biased toward one category over the other, thereby affecting the classification efficiency of the model.

The present study specifically focuses on the analysis of Chinese text because the majority of existing methods generally perform well when applied to the English language but generally perform very poorly when applied to Chinese language contexts. The reasons for such a discrepancy are the following. First, the word boundaries between the two languages are different. For example, in the English sentence “I like to eat an apple,” a space can be placed between each pair of words to indicate the word boundaries, which can easily be recognized by the machine-learning model. However, in the Chinese sentence “他的才能非凡 (his talent is extraordinary),” the characters are joined without spaces and none of the characters serves as a distinct word boundary. In this situation, tokenizers are required to separate the words, which are highly contextual. However, because each character in the same sentence might be differently tokenized, the training of word vectors presents a particular challenge. For example, the aforementioned sentence can be segmented into “他/的/才能/非凡 (his talent is extraordinary)” or “他/的/才/能/非凡 (he is just able to be extraordinary).” Second, different permutations and combinations of Chinese characters generate different meanings because words that are formed from multiple characters may have starkly different meanings from the component characters when individually used. Furthermore, some characters do not have independent meaning at all and must be combined with other characters to establish a meaning. Therefore, exploring deceptive-review detectors for the Chinese language is necessary.

Deceptive reviews are scattered across a wide range of industries such as in restaurants, hotels, 3C products (i.e., computer, communication, and consumer electronics), and beauty products. The present study utilized the deceptive reviews extracted from two secondary sources: restaurants reviews collected by Li et al. [10] from dianping.com (the largest consumer review website for restaurants in Mainland China) and the reviews collected by Chen and Chen [11] in their study of the Samsung case.

The bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) [12] technique was introduced as a base natural-language processing (NLP) architecture where the deceptive review-detection models were constructed. BERT is a pre-trained NLP model developed by Google in 2018. In general, BERT more accurately captures semantic contents than conventional models that use static word vectors. By using dynamic feature vectors, BERT effectively identifies the polysemous word meaning based on the context. In addition, because BERT can use Chinese characters as a basic unit, the issues caused by applying other architecture to word segmentation can be avoided. Therefore, BERT is a more suitable technology in handling Chinese texts. Furthermore, the textgenrnn model [13] is employed to generate new sets of deceptive reviews to assist in model training. The objectives of this study are as follows.

- To develop models based on the BERT architecture to detect deceptive reviews in the Chinese language and to compare the efficiency of the constructed models with standard approaches;

- To determine whether dynamic feature-vector models are more effective in extracting and identifying the text features of deceptive reviews than the static conventional feature-vector models.

2. Related Works

In this section, we briefly introduce the most popular methods for the detection of deceptive reviews and machine-learning methods for NLP. Based on the core idea behind them, we categorized the methods into two categories: machine- and deep-learning methods. To clearly explain the classical evolution of NLP models, we also introduced the principle behind these methods in Section 2.3. Before introducing our proposed deep-learning-based model for the detection of deceptive Chinese reviews, we introduced the core modules in our model, the pre-trained BERT language models.

2.1. Detection of Deceptive Reviews

Buller and Burgoon [14] defined deception as “an intentional act in which senders knowingly transmit messages intended to foster a false belief or interpretation by the receiver”. Bond and DePaulo [15] found that without assistance or training, the test subjects generally cannot distinguish between truth and lies, scoring an accuracy rate of only 54%. False or fraudulent content is delivered to recipients in various methods. The method most commonly encountered online consists of deceptive reviews. Therefore, the importance of automating assistance in the identification of false information has increased in recent years.

A model for “deceptive reviews” was first proposed by Jindal and Liu [16], who summarized three types of deceptive reviews: untruthful opinions, reviews on brands only, and non-reviews. Compared with the first type, the second and third types of deceptive reviews are generally easier to identify, and they can be effectively detected using conventional machine learning by manually labeling reviews as spam or not. However, the first type of false review is carefully created to promote the reputation of a brand or damage the reputation of other brands. They tend to appear similar to ordinary reviews and are difficult to identify by simply reading them. However, because of the scarcity of labeled deceptive-review datasets and the difficulties in artificially producing such training sets, breakthrough achievements on deceptive-review detection in research have been limited.

2.2. Machine- and Deep-Learning Methods

Currently, two main methods are used to detect deceptive reviews: conventional machine-learning and deep-learning classification methods. Among the standard approaches to machine learning, supervised learning is the most commonly adopted method. However, because of the difficulties in obtaining marked datasets and the low accuracy of human classification, much of the literature has either adopted simulated datasets or small-size real-world datasets for model training. Ott et al. [17] pioneered the use of machine learning for deceptive-review detection. Meanwhile, real reviews of 20 of the most popular five-star hotels in the Chicago area, which were extracted from the website TripAdvisor (including 400 real positive and 400 real negative reviews), were collected. Next, Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) was employed to collect 400 false positive and 400 false negative reviews of the same hotels. Thus, 1600 real and deceptive reviews were compiled. This dataset was subsequently referred to as the “gold-standard” dataset thereafter. Three approaches were used for feature extraction, namely, n-grams, psychological features, and a part-of-speech feature, and a support vector machine (SVM) classifier was trained to find a higher dimensional hyperplane between the two categories of data. The accuracy rate of the constructed model was found to be 89.8%, which was almost 30% higher than that of human judgment (61.9%).

However, Mukherjee et al. [18] found that the linguistic features of deceptive and real reviews in MTurk were substantially different, whereas those in Yelp tended to be similar. Hence, the deceptive reviews in Yelp were significantly more difficult to identify. The Unigram feature sets and SVM classifiers yielded an accuracy rate of 88.4% when used to detect the deceptive reviews in MTurk [17], whereas in Yelp, the accuracy rate dropped to 67.8% [18]. These findings demonstrated that identifying deceptive reviews in the real world is more difficult than in marketplaces. Thus, the use of closed marketplace data does not reflect real-world review contexts because the length, quantity, content, and repetition of the reviews in MTurk were highly correlated to the cost of services instead of the experience of reviewers.

The majority of the past studies on deceptive-review detection using machine-learning technology tended to use conventional word forms, shallow syntactic features, and deep linguistic features as text features. Under such conditions, machine-learning models rely on prior knowledge where the accuracy is limited by the selected feature sets. Furthermore, because the datasets used in the studies are not comparable, determining the optimal combination of feature sets is not possible. In addition, applying the same feature-selection method and classification model to different datasets may yield different accuracy rates. The semantics of artificially simulated deceptive reviews and the deceptive reviews generated in marketplaces are not the same as those written by humans for real-world contexts. Therefore, the expected classification performance of such models on real-world datasets could not be obtained. Nevertheless, Shahariar et al. [19] found that conventional machine learning has suffered a bottleneck where, even if more training data were available, the accuracy could not be noticeably improved.

For this reason, scholars have instead shifted toward deep-learning methods to identify deceptive reviews. The majority of Taiwanese studies on deep-learning deceptive-review detection models have tended to focus on the Samsung case. According to a set of deceptive reviews extracted from TaiwanSamsungleaks.org, Wang et al. [20] conducted six experiments, namely, temporal analysis, sentiment analysis, semantic analysis, social-network analysis, machine learning, and deep learning. The deep-learning method utilized text features to build a dictionary, which was then converted into strings and ensured that each review had the same length. A long short-term memory (LSTM) network model was then constructed to train and test the data. The accuracy of the constructed model was 68.8%. The study results revealed that the manually labeled dataset performed the best, whereas the deep-learning methods such as the multilayer perceptron and LSTM outperformed the standard machine-learning methods such as SVM in every respect. In the study of Wang et al. [21], Jieba (a Chinese word-segmenting list) was used to segment the deceptive reviews of the Samsung case into word feature sets, which were then converted into word embedding. LSTM was used for the training, resulting in an accuracy of 75%.

The aforementioned studies have demonstrated that compared with the conventional machine-learning methods, deep learning is a superior method in detecting deceptive reviews. The most commonly used methods include LSTM, bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM), and general regression neural networks. Overall, Bi-LSTM was found to exhibit the best performance. However, the feature engineering methods for texts still apply the conventional methods such as term frequency-inverse document frequency and n-grams, as well as static word vectors such as Word2Vec. Past studies customarily focused on model design. Ren and Zhang [22] and Wang et al. [23] developed attention neural networks so that the models were able to remember the hidden state of each word and retained more information. In addition, they assigned weights to the vectors so that the model prioritized sentences with larger weights. However, Li et al. [24] pointed out that the weights for attention and those of the hidden states were pre-defined values; hence, the model could only perform well if the feature vectors are appropriately calculated.

2.3. Evolution of NLP Models

Past attempts that applied deep-learning models to image recognition have achieved good results because both inputs and outputs could be represented by fixed-length vectors. When the length of the vector changes, the zero-padding technique can be applied. However, the input and output dimensions require prior definition to train a deep-learning model, whereas the output dimensions are usually not pre-definable in real-world problems such as speech recognition, virtual assistants, and machine translation. Therefore, Google proposed an encoder–decoder sequence-to-sequence learning (Seq2Seq) architecture [25], which solved the problem of unknown output dimensions and allowed the effective application of the model to various NLP tasks. Thereafter, the attention mechanism, self-attention mechanism, and natural-language models such as ELMo, BERT, and generative pre-trained transformer were developed, respectively.

The encoder–decoder model is one of the most important concepts in the field of NLP and has become the general architecture used in almost all corresponding models. The encoder is used to convert real problems into numerical form and obtain a fixed-length vector as the vector representation of the input data. The decoder is used to solve numerical problems and convert them into solutions and to decode the vector representation into the corresponding outputs. Such examples include text-to-text (such as translating English into Chinese), image-to-text (describing images with words), and voice-to-text (converting voice messages into text sequences). However, the Seq2Seq framework suffers from a notable disadvantage. Specifically, regardless of the length of the text, its input sequence must be compressed into a context vector with a fixed vector dimension. Therefore, less information is stored in the context vector, which leads to distortion in the input text with a longer length, and thus reduces performance.

Bahdanau et al. [26] developed the attention mechanism, which overcame the disadvantages of Seq2Seq. Instead of compressing a text sequence into a context vector, the attention mechanism generates a context vector for each word in a text sequence. Hence, it can effectively retain all information. The attention mechanism is a bidirectional recurrent neural network (RNN) model that does not operate with sufficient parallelization, thus reducing the computational efficiency. Furthermore, the calculation of the context vectors is complex, which requires substantial memory for the computation. The AI team of Facebook later replaced the RNN model with the CNN model [27], which allows more parallel pathways. However, CNN can only extract text in fragments at a time and lacks a comprehensive text-learning feature. Although the vectors of all the fragments can be merged into a single vector through continuous stacking, the complicated algorithm leads to computational inefficiency. In 2017, Google proposed the transformer model [28], which abandoned the RNN and CNN architecture and resolved the problems of the attention model by introducing a multi-head self-attention mechanism. The performance of the model was proven to be satisfactory.

The ELMo model was developed [29], which targeted the bottleneck of the conventional models (where static word vectors struggle to interpret polysemy). In contrast to the static vectors that assign a fixed vector for a given word, the ELMo model uses dynamic feature vectors that assign different vectors to a word based on the context. However, the multi-head self-attention mechanism was found to outperform Bi-LSTM in text extraction [30]. Google further proposed the BERT model [12], which is a pre-trained language model that utilizes the encoder from the transformer model while overcoming the insufficient capture of the semantics of the ELMo model. Thereafter, BERT has broken records and achieved the highest overall results across 11 NLP tasks. Specifically, it set records in the general language understanding evaluation benchmark at 80.5% (7.7% increase), accuracy rating in the multi-genre natural language inference to 86.7% (5.6% increase), and F1-score in the Stanford Question Answering Dataset v1.1 to 93.2 (an increase of 1.5 points). Thus, the development of BERT allowed for the rapid development of NLP. Since its conception, studies have proven that BERT outperforms ELMo in classification tasks across various NLP tasks. Therefore, in the current study, BERT was logically selected as the basis to develop the specific classification models used for deceptive-review detection.

2.4. Pre-Trained BERT Language Model

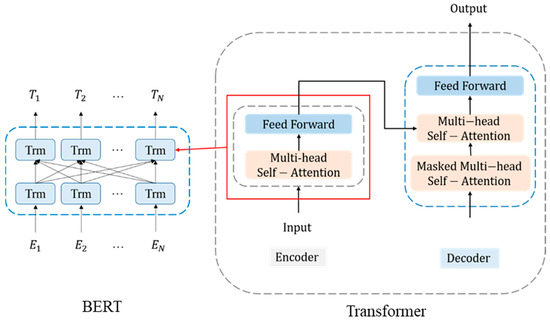

BERT is a pre-trained language model developed by Google in 2018 [12]. Its architecture is composed of an encoder based on the multi-layer bidirectional transformer [28], which allows deep bidirectional representation in both the left and right contexts in all layers. Figure 1 shows the BERT architecture, where “Trm” refers to the transformer encoder. The input of BERT can be a single text sentence or a pair of sentences. A special classification token ([CLS]) needs to be added to the beginning of each input sequence. The final hidden state of the [CLS] token is considered as a fixed-dimensional pooled representation of the input sequence. In addition, a separator token ([SEP]) must be added to the end of the input sequence. When the input sequence is a pair of sentences, [SEP] is used to distinguish the two sentences.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the BERT model.

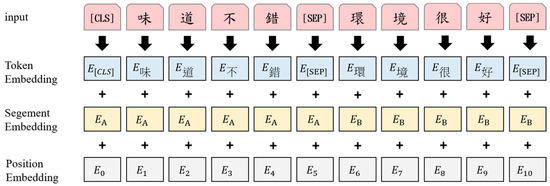

Next, the input-text sequence is converted into three embedding vectors, namely, token, segment, and position embedding. The token embedding divides the input sequence into the smallest units (WordPiece token for English and a character token for Chinese). To deal with the difference between the WordPiece token for English and a character token for Chinese, Cui et al. [31] proposed MacBERT which develops a whole word masking (WWM) strategy for Chinese BERT. Furthermore, Dai et al. [32] trained three Chinese BERT models with standard character-level masking (CLM), WWM, and a combination of CLM and WWM to evaluate the effectiveness of WWM. Their experimental results show that WWM plays a crucial role in Chinese BERT and transform it into Chinese applications properly. Besides, the segment embedding helps the model distinguish two inputs in a pair of sentences. Specifically, the first sentence is assigned to index zero and the second sentence is assigned to index one. The position embedding encodes the position information of the word into a feature vector. The maximum supported length of a word is 512 characters. Figure 2 shows the input representation of BERT. The three embedding vectors are then combined into the model input.

Figure 2.

Input representation used by BERT. Remark: Translation of the sentence in the example is “味道不錯 (the taste is good); 環境很好 (the environment is nice)”.

BERT is trained using two unsupervised tasks: the masked language model (MLM) and next-sentence prediction (NSP). MLM is used to train the deep two-way language expression vector, which uses masked words as prediction targets. NSP is used to pre-train a binary classification model to learn the relationship among sentences and predict whether a given sentence is a subsequent sentence of another sentence. Thus, a model with an excellent text-representation ability can be obtained. BERT can be used to handle various NLP tasks such as paired sentence classification, single sentence classification, question-and-answer tasks, and sequence labeling. Fine-tuning of the specific tasks can be achieved by adding an output layer instead of changing the internal structure of the model.

2.5. Introduction of Textgenrnn Modules

Textgenrnn [13] is a Python 3 module that creates text generators in units of characters or words. It is an RNN that applies attention weighting and skip embedding to accelerate model training and improve the training quality. Textgenrnn can calculate the probability of occurrence of each Chinese character in a training set and use the calculated probabilities to generate a new training sample through random sampling. The adjustable parameter, namely, temperature, allows for the control of the sampling probability. Specifically, higher temperature indicates that word occurrences with lower probability values are selected for the resampled set. For example, assuming that the probability is associated with the word-frequency occurrences, words with a higher frequency of occurrence have a higher probability of being selected for the set, and words with a lower frequency of occurrence have a lower probability. When the temperature value is larger, fewer common words are extracted. Generally, the range of temperature is between zero and one, and setting the temperature value to more than one is not recommended.

2.6. Introduction of the Information Set of Deceptive Reviews

In this study, consumer reviews from two industries (restaurants reviews from dianping.com and the reviews collected from the Samsung case) were used as the training and test samples to evaluate the effectiveness of the constructed models. Table 1 lists a comparison of the number of real and deceptive reviews from the two sources. The restaurant reviews were obtained from the study of Li et al. The dataset contained two categories: filtered reviews determined by the fake review-detection system and unfiltered reviews from the website. Each piece of data included a class label (label), user code (user), anonymized IP address (ip), rating (star), and review text (text). Because the current study only needed deceptive reviews, the content of the reviews was used as a feature alongside the class labels.

Table 1.

Number of real and false reviews according to the sample set.

The Samsung case reviews were obtained from the study of Chen et al. [11]. The data were obtained from Mobile01, including the deceptive and real reviews, and mainly consisted of cellphone reviews. The original data included the message-board original posts and replies. However, the present study only used the original posts, which included the content of the post (content), position relative to the other posts in the thread (nfloor), page number of the page where the post was posted (pnum), submission time of the post (time), ID of the poster (uid), username of the poster (uname), and label (is_spam). Because this study only performed classification based on the review text, the content of the reviews was used as both the feature and class labels.

3. Methodology

The objectives of this study were to construct BERT classification models, explore their effectiveness at identifying deceptive reviews, and compare the effectiveness of the constructed models with the conventional models, i.e., the conventional and dynamic-feature text. Unlike the conventional models, our framework considered both word-level and character-level detection. As mentioned earlier, conventional models for Chinese deceptive reviews usually perform on the word level, which means the conventional models must require data cleansing, word segmentation, and the removal of stop words. Although word-level features generally reflect more meaningful and more precise concepts, the errors of word segmentation usually lead to much worse influences for model building. Therefore, we involved the BERT classification model which performs on the character level so that the errors of word segmentation could be corrected.

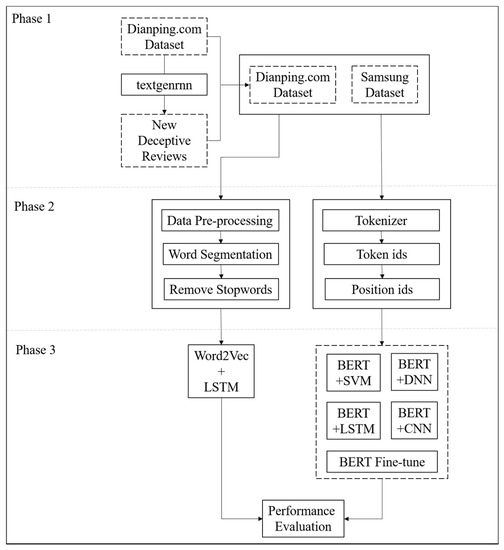

To construct a hybrid model which can perform on both word-level and character-level features, we proposed a hybrid framework, as shown in Figure 3. This study was divided into three phases. The first phase involved the processing of the dataset (review generation and deletion of unusable reviews). The second phase involved the preprocessing of text data, which was divided into the conventional methods (data cleansing, word segmentation, and removal of stop words) and the BERT method (tokenization and conversion of characters into token and position IDs). The third phase was model training. To compare the conventional and dynamic-feature text classification methods, a classification model based on static features was set as a benchmark.

Figure 3.

Research Framework.

3.1. Phase 1: Dataset Processing

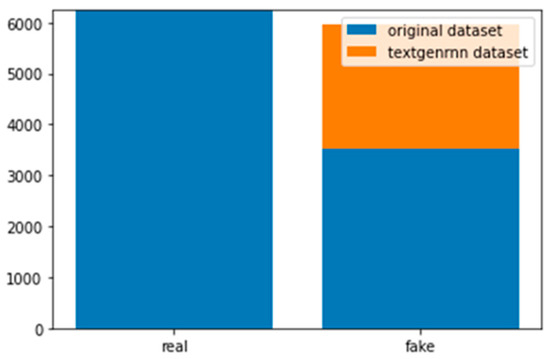

A total of 6241 real reviews and 3524 deceptive reviews were available in the Dianping dataset. We observed that a noticeable discrepancy existed between the proportions of the two review categories. In addition, the reviews tended to be short in terms of length. To minimize the influence of the aforementioned features on the classification performance of the model, the textgenrnn [13] module was employed to generate new deceptive review samples to facilitate the training phase. The temperature value was set to 0.5. The temperature is a hyperparameter of textgenrnn which can control the sampling probability of Chinese characters. The larger the temperature, the smaller the sampling probability. Thus, the initial value of 0.5 led every Chinese character to share the same initial sampling rate. A total of 2433 new deceptive reviews were generated, and the simulated reviews were semantically segmented and smoothened. Table 2 shows an example of the generated deceptive reviews, and Figure 4 shows the histograms of the original reviews and generated fake reviews by texgenrnn. Because the Dianping dataset mainly was from Mainland China and other countries of which people would use simplified Chinese to write reviews, the reviews were in simplified Chinese characters. However, the reviews of the Samsung case were in traditional Chinese characters. To ensure the use of the same language, the reviews from Dianping were converted into traditional Chinese.

Table 2.

An example of deceptive reviews generated by texgenrnn.

Figure 4.

Histograms of original reviews and generated fake reviews by texgenrnn.

The original Samsung dataset garnered 16,759 reviews. However, only 750 were deceptive reviews. We could observe that the two types of reviews were largely disproportionate. To minimize the influence of such a gap on the training and classification performance of the models, this study randomly selected 2250 real reviews so that the ratio between the real and deceptive reviews was only 3:1. The next stage was data cleansing, which involved deleting null values and any unusable reviews (such as duplicate reviews and reviews that in fact advertised products and services). Because such reviews were few, they were manually removed from the dataset. The length of most of the reviews from both datasets was within 100 characters, whereas a few reviews were less than 30 characters in length. Excessively short text, i.e., where disproportionally fewer text features were present, might cause noise. Thus, any text with fewer than 30 characters was removed from the dataset.

3.2. Phase 2: Data Pre-Processing

Phase 2 involved dividing the constructed models into conventional and BERT models. The two classification types had different input formats and processing methods. First, as part of the conventional text pre-processing, data cleansing was performed to delete punctuation marks, numbers, non-Chinese characters, and any null values. Subsequently, the existing tokenizer was used to segment the text. The commonly used tokenizers included Jieba, CoreNLP, and CKIP. Because CKIP does not provide a Chinese language resource kit, it was not adopted. When a 2000-character-long text was tokenized, the execution time of Jieba was 0.01 s and that of CoreNLP was 1.32 s, which indicated that Jieba is superior to CoreNLP in terms of computational efficiency. In addition, when an unrecognizable word was encountered, CoreNLP tended to segment it into individual characters. For example, when the term “同婚專法 (abbreviation of ‘同性婚姻專法,’ which means ‘same-sex marriage law’)” was tokenized using Jieba, the result was “同婚 (same-sex marriage)/專法 (dedicated law).” However, when tokenizing was performed using CoreNLP, the result became “同 (same)/婚 (marriage)/專 (dedicated)/法 (law).” We could observe that the output of the word segmentation by Jieba was thus more consistent with the Chinese linguistic logic. Hence, Jieba was selected for the word-segmentation process in this study. Equation (1) formally defines the segmentation function based on Jieba.

where indicates the TF-IDF value [33] of a word in Jieba corpus [21] and indicates all sub-words of the word .

After the segmentation, the stop words were removed. Stop words are characters that are frequently used yet are not helpful in the text analysis and thus should be removed. Common stop words in Chinese include prepositions (such as “為” and “在”), adverbs (such as “也”), and auxiliary words (such as “的”). This study used the stop word table proposed by the Harbin Institute of Technology as a reference to remove any stop words present in the texts. Table 3 lists an example of the output of each step using the conventional text pre-processing method.

Table 3.

Outputs of text pre-processing using the conventional method.

Next, the BERT method was used for the text pre-processing. First, the length of the text was determined. Because BERT only supports up to five hundred and twelve tokens and the characters that follow the five hundred and twelfth token are truncated, the maximum length of each review was set to five hundred and twelve characters. Next, the reviews were converted into an input format that is compatible with BERT. Because the sentences used in this study were single sentences, they only needed to be converted into two ID tensors (token and position IDs) and did not require the conversion of segment IDs. The detailed conversion process is explained in the following.

Figure 5 shows an example of how the text was converted into token and position IDs. For the Chinese language, BERT uses characters, instead of words, as training features. Therefore, the text was first tokenized, and each Chinese character was individually regarded as a token. In contrast to the conventional methods, the punctuation did not need to be removed during this process because the dictionary used by BERT contains not only Chinese characters but also punctuations, which were treated as a feature value in the training. Each Chinese character corresponded to an index value (ID) in the dictionary. [CLS] was added at the start of the text sequence. [CLS] was considered as the vector representation of the entire input sequence, which was equivalent to the sentence vector. [SEP] was added at the end of the text sequence to indicate the end of a text. Equation (2) shows a recurrent definition of the sentence vector generated by BERT.

where is an encoder block of the transformer with multi-head attention [28] that can learn multiple representation features from the text.

Figure 5.

Example conversion process of the token and position IDs. Note: The translation of the sentence in the example is “那服務沒話說~ ([I have] no negative comments about that service at all) 主動 (proactive), 熱情 (enthusiastic), 但真的不會讓人覺得不舒服~ (But [it] really won’t make you feel uncomfortable)”.

To ensure that all input sequences had the same length, zero-padding was performed at the back end of each text sequence. For example, assuming that the expected length was set to 100, if the length of a given text was 56, 44 zeros were added to the end of the text so that its length was normalized to a value of 100 characters. The zeros thus corresponded to the token length [PAD]. If the length of the input sequence exceeded one hundred, the characters following the one hundredth text were truncated. The corresponding position IDs were then generated according to the length of the text sequence. Because the function of the position IDs that were used to record the position of the real tokens was to define the range of the attention mechanism, “1” was used to represent the positions of the real tokens (the position the model should pay attention to), and “0” was used as padding (the position the model does not need to pay attention to). For example, if the length of each text in the training set was 100 characters and the length of input A was 56, then the length of the position IDs of A would also be 100, where 56 are “1 s” and 44 are “0 s”. Finally, the token and position IDs were converted into tensors and input into the model for training.

3.3. Phase 3: Model Designing

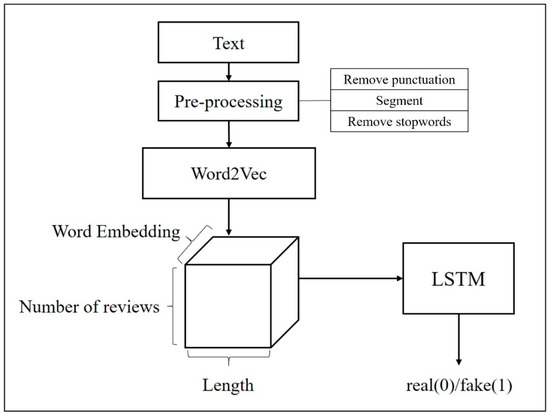

3.3.1. Word2Vec + LSTM

To compare the performance between the BERT and conventional models, this study established a baseline model that used Word2Vec as a tool for training the word vectors and LSTM as the classifier because the combination of Word2Vec and LSTM was deemed to be the most optimal combination among the models. First, the pre-processed dataset (tokenized and with the punctuation and stop words removed) was introduced into the Word2Vec model to train the word vectors. The number of dimensions was set to 150 [11]. Because the average number of words in the Dianping reviews was 45.79 and that of the Samsung reviews was 104.26, the input length was set to 100 characters.

The word-vector matrix of each review was thus (100, 150), and that of the dictionary was defined by the number of words in the dictionary (100). The word vectors of all reviews were then combined into a three-tuple (containing the number of reviews of 100 and 150) and input into the LSTM model for training to binary classification to either real- or false-review categories. Figure 6 shows the architecture of the conventional classification model that combined Word2Vec and LSTM.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the Word2Vec + LSTM model.

3.3.2. BERT Classification Model

BERT provides two training models with different sizes, namely, 12-layer, 768-hidden and 24-layer, 1024-hidden . In this study, the BERT-base for Chinese was used. The BERT models adopt two approaches: fine-tuning and feature approach. Fine-tuning allows users to use their own datasets and fine-tune the BERT model to complete specific NLP tasks. The advantage of this approach is that many parameters of the model do not need re-learning. Hence, the training and learning efficiency is high. Moreover, it indicates that even if the size of the training-data samples is limited, the classification output remains satisfactory.

The feature approach uses the BERT model to extract text features. The first token [CLS] that is output by the last layer of the BERT model is used as the vector representation of the corresponding input sequence, and the output vectors that follow [CLS] are used as the word vectors of each word in the corresponding input sequence. In addition, the output vector of the last layer of the BERT model can be input into other models for training. This study used the BERT feature-extraction method to construct four classification models. In addition, BertForSequenceClassification (a text classification model), which was developed by Hugging Face [34], was employed, and the main dataset in this study was input to fine-tune the model. Please note that different variants of our proposed model could deal with different datasets. In other words, we could choose the variant according to the validation result in a given dataset.

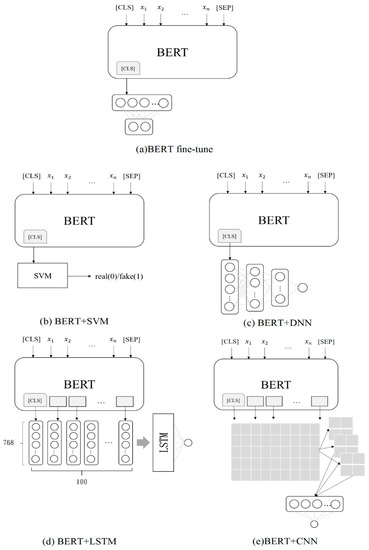

- Fine-tuning

BertForSequenceClassification [34] was employed in the present study to fine-tune the dataset, which was composed of a BERT model with a single linear classification layer. When data were input into the model, the pre-training model and linear classification layer were trained together. Adam was used as the optimizer. The learning rate was set at 2 × e−5 with three epochs and a batch size of eight. Figure 7a shows the architecture of the BERT fine-tuning model.

Figure 7.

BERT classification models.

- b.

- BERT + SVM

The first feature model built by this study used the first token [CLS] (a set of 768-dimensional sentence vectors) that was output by the last layer of the BERT model as an input to the SVM model. The radial basis function kernel was used as the kernel function. The SVM classifier output was either “0” or “1” (“0” represented real reviews and “1” represented deceptive reviews). Figure 7b shows the architecture of the BERT + SVM model.

- c.

- BERT + DNN

The second feature model used the first token [CLS] that was output by the last layer of the BERT model as an input to the DNN model. The input layer contained 768 nodes with two fully connected hidden layers (with 484 and 128 hidden nodes). The final output node was one. The activation function of each layer was performed by the rectified linear unit (ReLU), and the activation function of the last layer was compressed using the sigmoid function. The dropout of each layer was set to 0.1. The optimizer used was AdaMax. The learning rate was 0.0001, the number of epochs was set to 20, the batch size was split to 1024, and the final output was either “0” or “1” (“0” represented a real review and “1” represented a deceptive review). Figure 7c shows the architecture of the BERT + DNN model.

- d.

- BERT + LSTM

The third feature model used all the character vectors that were output by the last layer of the BERT model as inputs to the LSTM model. However, because the length of the majority of the reviews was less than 100 characters, when the LTSM input length was fixed at 512 characters, a large number of null values had to be added. To avoid the effect of the null values on the training performance, the maximum input length was set to 100. Each character vector contained 768 dimensions. The character–vector matrix for a single review input was (100, 768), which was the LSTM input shape. A hidden layer with 256 nodes was also used. ReLU was used as the activation function. The output node of the last layer was one. Thus, final compression was required using the sigmoid function. The dropout for each layer was set to 0.1. The optimizer used was AdaMax. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, the number of epochs was set to 10, the batch size was 1024, and the final output was either “0” or “1” (“0” represented real reviews and “1” represented deceptive reviews). Figure 7d shows the architecture of the BERT + LSTM model.

- e.

- BERT + CNN

The fourth feature model used all the character vectors that were output by the last layer of the BERT model as inputs to the CNN model. The input length was set to 100. Each character vector contained 768 dimensions with a height of one. The character–vector tuple that contained a single review input was (100, 768, 1), which was used to define the CNN input shape. The convolutional layer used a size filter (3, 768). Because 768 dimensions were required to represent a single character, three characters were selected at a time and were made to pass through 32 filters. The size of the largest pooling layer was (2, 2). A total of 256 nodes were connected to the previously fully connected layer. ReLU was again used as the activation function. The output node of the last layer was set to one; thus, the sigmoid function was applied to the final layer output. The dropout for each layer was set to 0.3. AdaMax was again used as the optimizer. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, the number of epochs was fixed at 10, the size of the batches was set to 24, and the final output was either “0” or “1” (“0” represented real reviews and “1” represented deceptive reviews). Figure 7e shows the architecture of the BERT + CNN model.

4. Experimental Evaluations

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets. First, the dataset was split into training and test sets at a ratio of 70:30. Then, the training set was further divided into training and validation sets at a ratio of 90:10. Thus, 63% of the data were used to train the models, 7% were used to adjust the hyperparameters of the models and to preliminarily evaluate their classification ability, and 30% were used to test the accuracy of the models.

To facilitate the performance evaluation, a confusion matrix was employed to calculate the accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under ROC (AUC) of the models. This study put more emphasis on accuracy, which was defined as the ratio of correctly classified samples to the total samples, to demonstrate the reliability of the classification results. A total of 15,089 reviews were collected from the Dianping and Samsung datasets. The number of valid reviews that were retained after the removal of the null values, reviews with a length of fewer than 30 characters, and unusable reviews was 14,954. The real and deceptive reviews from the Dianping and Samsung cases are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Real and deceptive reviews from the Dianping and Samsung case.

The three different datasets (Dianping, Samsung, and combined datasets) were used to verify the classification efficiency of the models, and the classification results are listed in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, respectively. In addition, the aforementioned classification results were compared with the results of past studies that also used the same Samsung dataset (Table 8).

Table 5.

Classification results using the Dianping dataset.

Table 6.

Classification results using the Samsung dataset.

Table 7.

Classification results using the combined dataset (Dianping and Samsung).

Table 8.

Comparison of the classification efficiency between the present and past studies using the Samsung dataset.

The lists in Table 5 and Table 6 indicate that regardless of whether the reviews originated from Dianping or Samsung, both feature- and fine-tuning-based BERT models exhibited better overall performance than the Word2Vec + LSTM model, demonstrating an 8–10% increase in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. In addition to the individual testing of the models using the Dianping and Samsung datasets, the two datasets were combined to investigate whether the models proposed by the present study could effectively distinguish real from deceptive reviews from different industries. The results are listed in Table 7 which indicates that the highest detection accuracy of the models that used the combined dataset was 80%.

The results listed in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 indicated that the models that used all the character vectors that were output by the last layer of BERT as training features (BERT + LSTM and BERT + CNN) did not significantly perform better than those that used [CLS] outputs by the last layer of BERT as training features (BERT + SVM and BERT + DNN). However, the model that used only the sentence vectors for classification yielded overall good results as evidenced by the accuracy of the SVM model scoring more than 80%. We can thus conclude that even though character vectors were used as training features, the performance of the model did not noticeably improve.

The effectiveness of the established models in terms of detecting deceptive reviews was then compared. The BERT models were found to demonstrate better overall performance than the static feature-vector models with a maximum accuracy of 77% using the Dianping dataset and 92% accuracy using the Samsung dataset. In addition, the effectiveness of the models was compared with those of the models constructed in the past studies. The results showed that the dynamic feature models constructed in this study significantly outperformed the models proposed in previous studies.

First, a model based on the static feature word vectors was established as a baseline model. Next, five BERT models were subsequently established. Table 8 indicates that the classification efficiency of the dynamic-feature models developed in this study was better than that of the methods proposed in past studies. Among all the proposed models, the performance of the BERT + DNN was the highest, exhibiting an accuracy of 92%, which was 17% higher than the best result of past studies (75%).

In addition, this study combined the two datasets to investigate whether the models proposed by this study could effectively distinguish real from deceptive reviews in different industries. The highest achieved accuracy of the models that used the combined dataset was 80%. The findings of this study revealed that the accuracy of the models based on dynamic features was 8–10% higher than that of the models based on static features. The BERT models that used dynamic word vectors demonstrated improvement over the models that used static word vectors in capturing semantics. Overall, the classification results were more satisfactory.

5. Conclusions

This study used word vectors as classification features of the models to identify deceptive reviews. Past research on deceptive-review detection tended to use tools with static word vectors (such as Word2Vec and GLoVe). Because the vector results were fixed, the models could neither be applied to different contexts nor could they reliably identify polysemy in the Chinese language. Therefore, the classification efficiency of these models was limited by the influence of the word vectors. To accurately capture the semantics and improve the prediction results, the present study constructed models based on BERT architecture. BERT has achieved breakthrough development in various fields of NLP. Compared with the methods that use static word vectors, BERT considers contextual relationships and assigns each word with a set of word vectors that are suitable for the semantics embedded within the text. Such a dynamic approach minimizes the problem of polysemy and improves performance when capturing semantics. The experimental results show that our proposal can achieve 0.92 in terms of precision, 0.91 in terms of recall, and 0.91 in terms of F1-score. The improvement rate of our proposal is higher than 20%.

Besides, according to the experimental results, we found that the models that used all the character vectors of the last layer output by BERT as a training feature did not significantly perform better than those that used [CLS] (as a sentence vector) as a training feature. Because BERT is a sequence-level model, the features at the word/character level are thus not well represented. Therefore, the word/character vectors other than [CLS] that were output by the last layer of BERT did not help the model improve the classification performance. Although our proposal achieved excellent performance, it is difficult to update the model in real-time. Accordingly, for future works, we will involve the notion of transfer learning to fine-tune the model so that our model can be aware and deal with the occurrence of new labels. Besides, we plan to utilize the mechanism of incremental learning to retrain the model in real-time. Furthermore, we will consider the word-vector features in the model to further enhance the classification effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, C.-H.W.; supervision, K.-C.L.; review and editing, J.-C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology grant number MOST 109-2221-E-005-057-MY2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akerlof, G. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Li, D.; Wei, S.; Wang, M. Research of Deceptive Review Detection Based on Target Product Identification and Metapath Feature Weight Calculation. Complexity 2018, 2018, 5321280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Dac, N.N.; Carson, S.J.; Moore, W.L. The Effects of Positive and Negative Online Customer Reviews: Do Brand Strength and Category Maturity Matter? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samsung Fined for Hiring Bloggers to Write Fake Reviews, Attack Rival HTC. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/technology/samsung-fined-for-hiring-bloggers-to-write-fake-reviews-attack-rival-htc-20131025-2w5nx.html (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- 2019 Tripadvisor Review Transparency Report. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/TripAdvisorInsights/w5144 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Bhundiya, M.; Trivedi, M. An Efficient Spam Review Detection Using Active Deep Learning Classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Vision (AIMV), Gandhinagar, India, 24–26 September 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathla, G.; Kumar, A. Opinion spam detection using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 26–27 August 2021; pp. 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Using Inductive Transfer Learning to Improve Hotel Review Spam Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–12 August 2021; pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.; Kumar Dubey, M. An overview of soft computing techniques on Review Spam Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM), London, UK, 28–30 April 2021; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Shao, J. Spotting Fake Reviews via Collective Positive-Unlabeled Learning. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Shenzhen, China, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-R.; Chen, H.-H. Opinion Spam Detection in Web Forum. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web, Florence, Italy, 18–22 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, M. Textgenrnn. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/textgenrnn/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Buller, D.B.; Burgoon, J.K. Interpersonal Deception Theory. Commun. Theory 1996, 6, 203–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.F.; DePaulo, B.M. Accuracy of Deception Judgments. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, N.; Liu, B. Opinion Spam and Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2008 international conference on web search and data mining, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 11–12 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, M.; Choi, Y.; Cardie, C.; Hancock, J.T. Finding deceptive opinion spam by any stretch of the imagination. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1107.4557. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Venkataraman, V.; Liu, B.; Glance, N. What yelp fake review filter might be doing? In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Boston, MA, USA, 8–10 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shahariar, G.M.; Biswas, S.; Omar, F.; Shah, F.M.; Hassan, S.B. Spam Review Detection Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–19 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-C. Fake news and related concepts: Definitions and recent research development. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2020, 16, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Day, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Liou, J.-W. Detecting spamming reviews using long short-term memory recurrent neural network framework. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on E-commerce, E-Business and E-Government, Hong Kong, China, 13–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y. Deceptive opinion spam detection using neural network. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING), Osaka, Japan, 11–16 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Detecting deceptive review spam via attention-based neural networks. In Proceedings of the Sixth Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing, Dalian, China, 8–12 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Qin, B.; Ren, W.; Liu, T. Document representation and feature combination for deceptive spam review detection. Neurocomputing 2017, 254, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, J.; Auli, M.; Grangier, D.; Yarats, D.; Dauphin, Y.N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Neumann, M.; Iyyer, M.; Gardner, M.; Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Zettlemoyer, L. Deep Contextualized Word Representations. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Müller, M.; Rios, A.; Sennrich, R. Why self-attention? a targeted evaluation of neural machine translation architectures. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.08946. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B.; Yang, Z. Pre-training with whole word masking for chinese bert. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 3504–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, C.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, E.; Qiu, X.; Li, P.; Tang, D. Is Whole Word Masking Always Better for Chinese BERT?: Probing on Chinese Grammatical Error Correction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.00286. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman, A.; Ullman, J.D. Data Mining; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-139-05845-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. Huggingface’s transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.03771. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).