Dracocephalum palmatum S. and Dracocephalum ruyschiana L. Originating from Yakutia: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

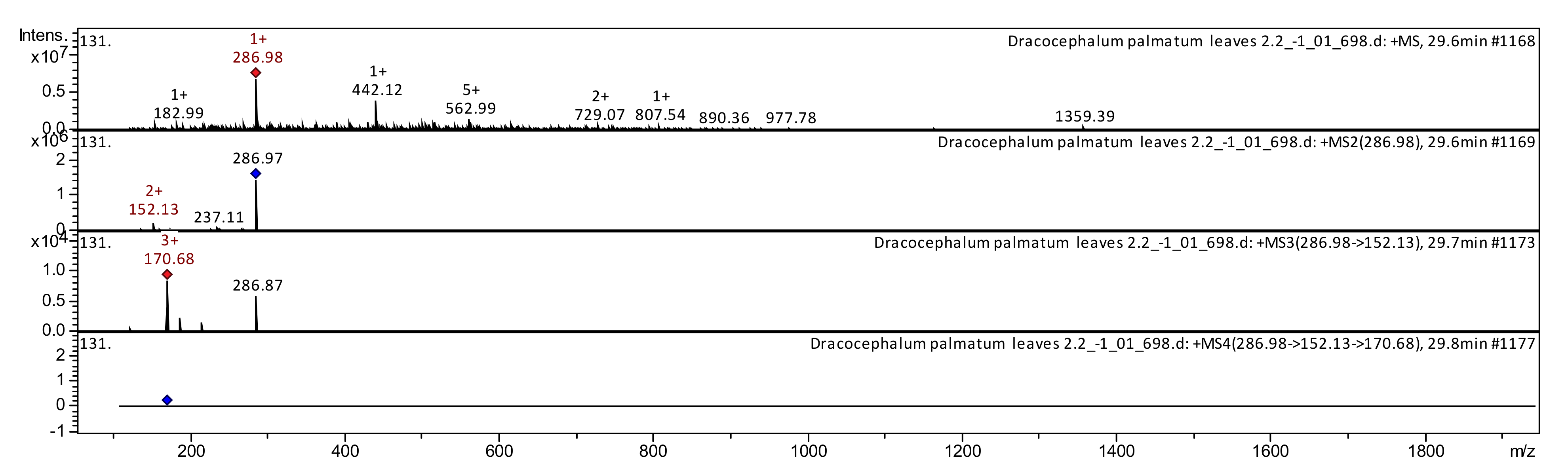

3.1. Flavones

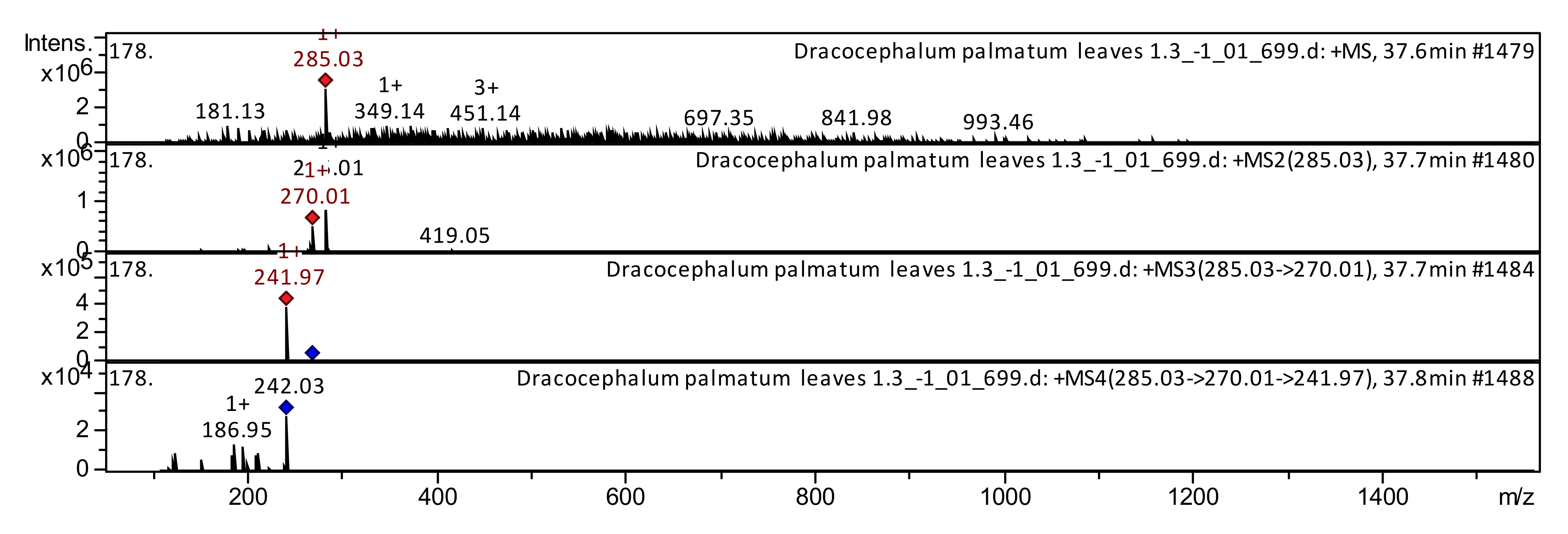

3.1.1. Trihydroxyflavones

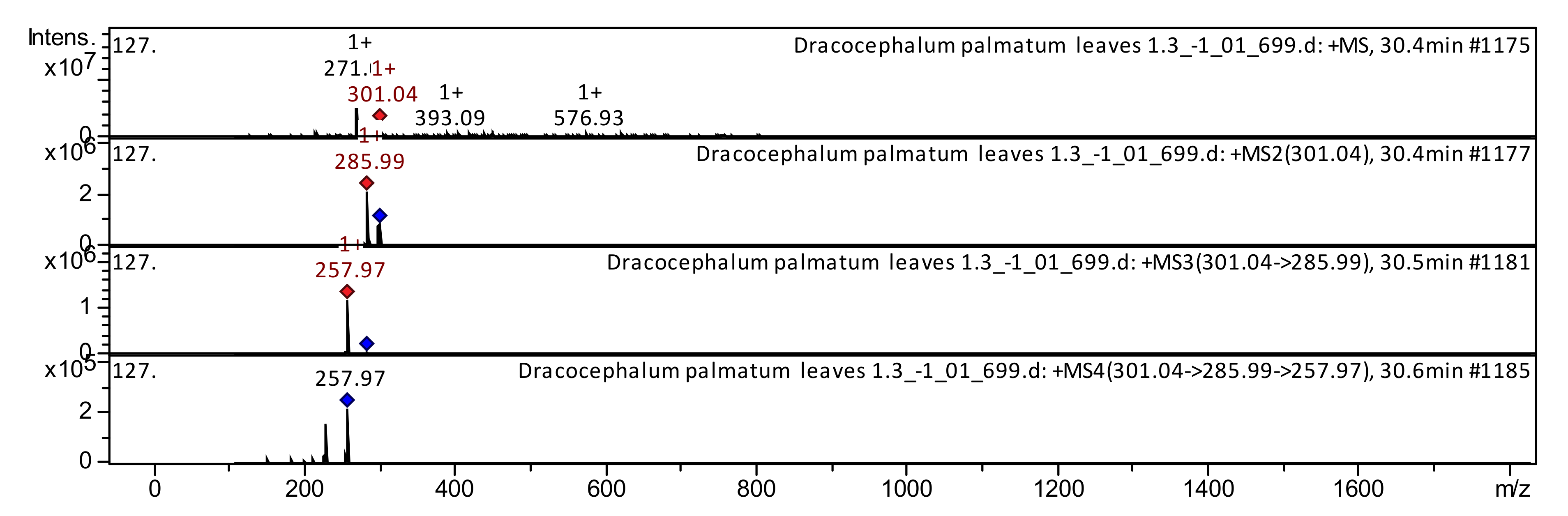

3.1.2. Tetrahydroxyflavones

3.1.3. Dimethoxyflavones

3.1.4. Trimethoxyflavone

3.1.5. Isoflavones

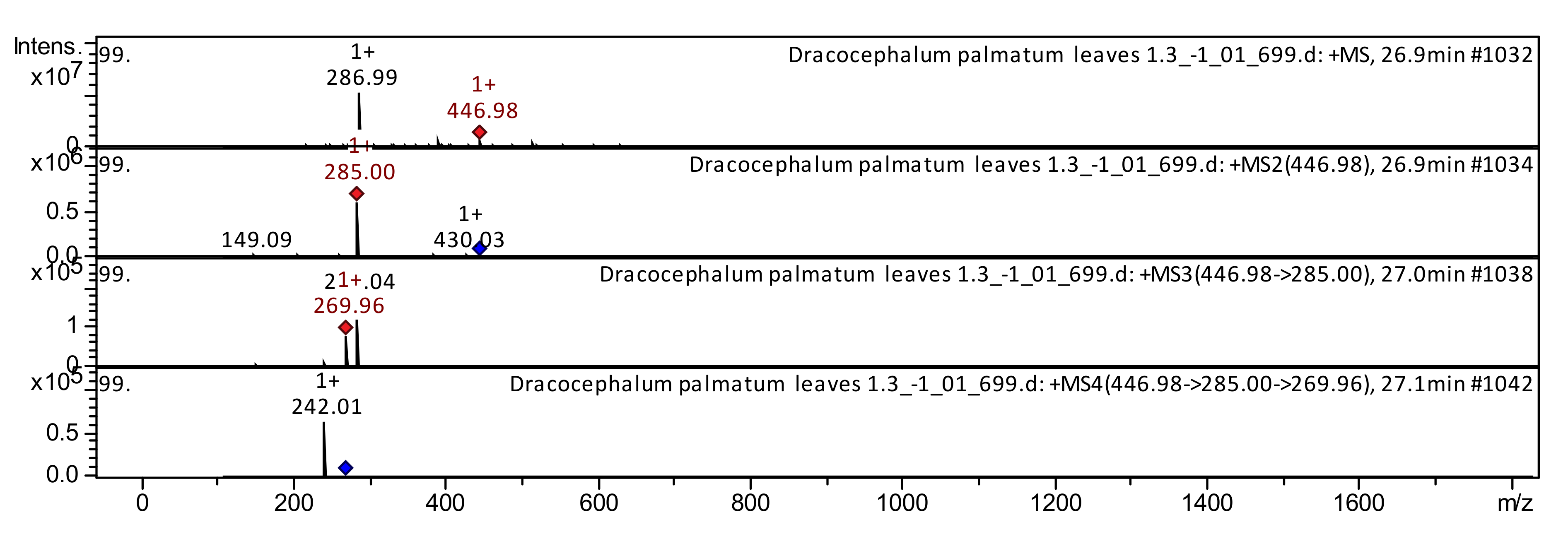

3.1.6. Flavone Glucoside

3.1.7. Flavone Glucuronide

3.2. Flavonols

3.2.1. Trihydroxyflavones

3.2.2. Tetrahydroxyflavone

3.2.3. Hexahydroxyflavone

3.2.4. Dihydroflavonols

3.3. Condensed Tannin

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Chemicals and Reagents

4.3. Fractional Maceration

4.4. Liquid Chromatography

4.5. Mass Spectrometry

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| № | Variety of Dracocephalum | Class of Compounds | Identified Compounds | Formula | Mass | Molecular Ion [M − H]− | Molecular Ion [M + H]+ | 2 Fragmentation MS/MS | 3 Fragmentation MS/MS | 4 Fragmentation MS/MS | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLYPHENOLS | |||||||||||

| 1 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigeninidin | C15H11O4 | 255.2454 | 256 | 168 | 122 | Triticum [46] | ||

| 2 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin (5,7-dixydroxy-2-(40hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) | C15H10O5 | 270.2369 | 269 | 225 | 181 | 117 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Andean blueberry [10], Lonicera japonicum [11], Mexican lupine species [12] | |

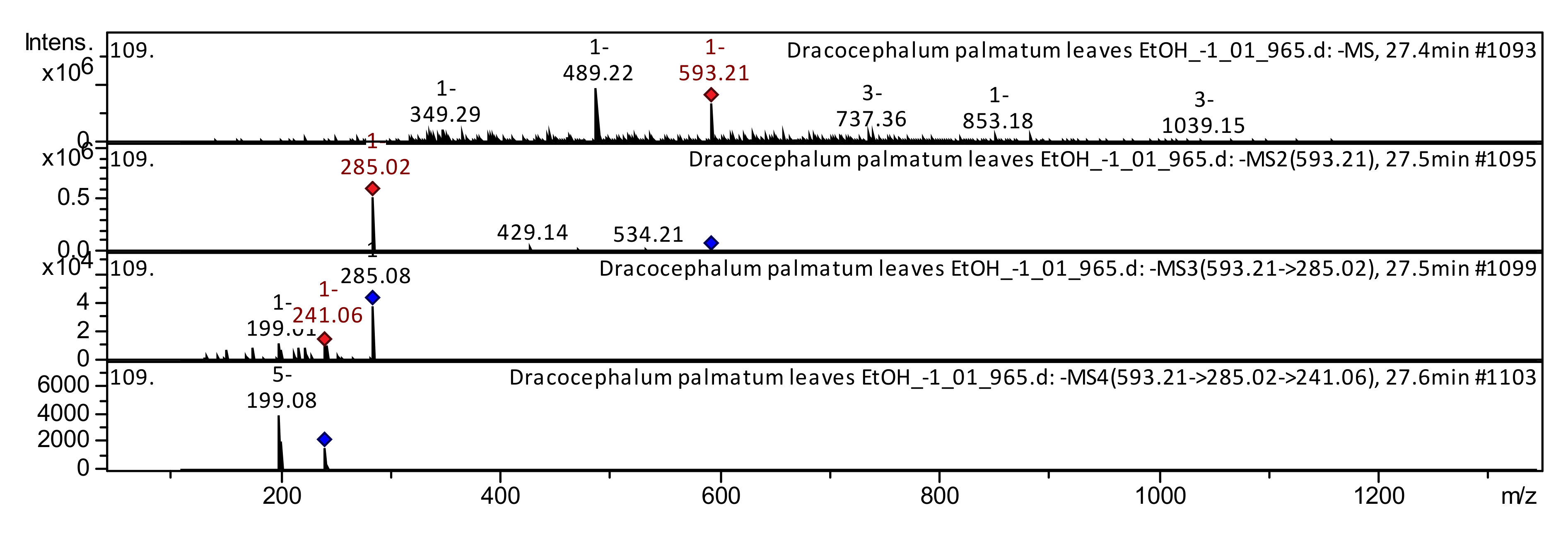

| 3 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Negletein (5,6-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-flavone) | C16H12O5 | 284.2635 | 285 | 271 | 241 | 187 | Actinocarya tibetica [19] | |

| 4 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Acacetin (linarigenin, buddleoflavonol) | C16H12O5 | 284.2635 | 285 | 268 | 211; 143 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Mexican lupine species [12], Mentha [14], Dracocephalum moldavica [15], Wissadula periplocifolia [18] | ||

| 5 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 286.2363 | 287 | 286; 153 | 171 | 153 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Eucalyptus [16], Lonicera japonicum [11] | |

| 6 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Apigenin-7, 4′-dimethyl ether | C17H14O5 | 298.2901 | 299 | 284 | 256 | Ocimum [20] | ||

| 7 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Diosmetin (luteolin 4′-methyl ether, salinigricoflavonol) | C16H12O6 | 300.2629 | 301 | 286 | 258 | Andean blueberry [10], Lonicera japonicum [11], Cirsium japonicum [13], Mentha [14], Dracocephalum moldavica [15] | ||

| 8 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Salvigenin | C18H16O6 | 328.3160 | 329 | 314; 240 | 154 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Ocimum [20] | ||

| 9 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Nevadensin | C18H16O7 | 344.3154 | 345 | 311 | 284 | 149 | Mentha [14], Ocimum [20] | |

| 10 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin 7-sulfate | C15H10O8S | 350.3001 | 349 | 269 | 223 | sulfates [18], G. linguiforme [28], | ||

| 11 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Chrysin 6-C-glucoside | C21H20O9 | 416.3781 | 417 | 51; 127 | 333; 267 | 165 | Passiflora incarnata [26] | |

| 12 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Chrysin glucuronide | C21H18O10 | 430.3616 | 431 | 255 | 255; 153 | 171 | F. pottsii [28] | |

| 13 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Apigenin-5-O-glucoside | C21H20O10 | 432.3775 | 433 | 414; 274; 215; 145 | 371; 245; 147 | 327 | Rice [22] | |

| 14 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin-7-O-glucoside (apigetrin, cosmosiin) | C21H20O10 | 432.3775 | 433 | 271 | 153 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Mentha [24], Mexican lupine species [12] | ||

| 15 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin 7-O-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | 446.361 | 447 | 271 | 153 | 271; 171 | Pear [25], Bougainvillea [27] | |

| 16 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Acacetin 7-O-glucoside (tilianin) | C22H22O10 | 446.4041 | 447 | 285; 149 | 270 | 242 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Bougainvillea [27] | |

| 17 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside | C22H22O10 | 446.4041 | 447 | 428; 344 | 343; 230; 133 | 232 | Mexican lupine species [12] | |

| 18 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-glucoside (cynaroside, luteoloside) | C21H20O11 | 448.3769 | 449 | 287; 199 | 153 | Lonicera japonicum [11], Pear [25], Passiflora incarnata [26] | ||

| 19 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Acacetin 7-O-beta-D-glucuronide | C22H20O11 | 460.3876 | 459 | 283; 343; 175 | 268 | 267 | Dracocephalum moldavica [15] | |

| 20 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Luteolin-7-O-beta-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | 462.3604 | 463 | 287 | 268 | 245; 119 | Mentha [14], rat plasma [32], Newbouldia laevis [30] | |

| 21 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Diosmetin-7-O-beta-glucoside | C22H22O11 | 462.4035 | 463 | 287 | 168 | 123 | Dracocephalum moldavica [15], Oxalis corniculata [23] | |

| 22 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Luteolin O-acetyl-hexoside | C23H22O12 | 490.4136 | 489 | 285; 450 | 199 | 155 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4] | |

| 23 | D. palmatum | Isoflavone | Apigenin 7-O-beta-D-(6″-O-malonyl)-glucoside | C24H22O13 | 518.4237 | 519 | 502; 184 | 125 | Dracocephalum moldavica [14], Zostera marina [21] | ||

| 24 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside malonylated | C25H24O13 | 532.4503 | 533 | 497; 205 | 377; 335 | Mexican lupine species [12] | ||

| 25 | D. palmatum | Isoflavone | 2′-Hydroxygenistein O-glucoside malonylated | C24H22O14 | 534.4231 | 533 | 489 | 285; 326 | 284 | Mexican lupine species [12] | |

| 26 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-beta-D-(6″-O-malonyl)-glucoside | C24H22O14 | 534.4231 | 535 | 436; 354; 287; 214 | 328; 238 | Dracocephalum moldavica [15], Zostera marina [21] | ||

| 27 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Acacetin C-glucoside methylmalonylated | C26H26O13 | 546.4758 | 547 | 529; 496; 369 | 343 | Mexican lupine species [12] | ||

| 28 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin 8-C-hexoside-6-C-pentoside | C26H28O14 | 564.4921 | 565 | 547; 511; 427 | 529; 499 | 511 | Triticum aestivum L. [47,48], Bituminaria [49], Licania Rigida [50] | |

| 29 | D. ruyschiana | Flavone | Apigenin 8-C-pentoside-6-C-hexoside | C26H28O14 | 564.4921 | 565 | 547; 274 | 529; 474; 247 | 390 | Triticum aestivum L. [47,48], Bituminaria [49], Licania Rigida [50] | |

| 30 | D. palmatum | Flavone | Apigenin 6-C-[6″-acetyl-2″-O-deoxyhexoside]-glucoside | C29H32O15 | 620.5554 | 621 | 561; 218 | 533 | 445; 222 | Passiflora incarnata [26] | |

| 31 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavonol | Kaempferol (3,5,7-trihydroxy-2-(4-hydro-xyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) | C15H10O6 | 286.2363 | 287 | 269; 202 | 233; 205 | 216 | Andean blueberry [10], Lonicera japonicum [11], Rhus coriaria (Sumac) [36], potato leaves [37], rapeseed petals [38] | |

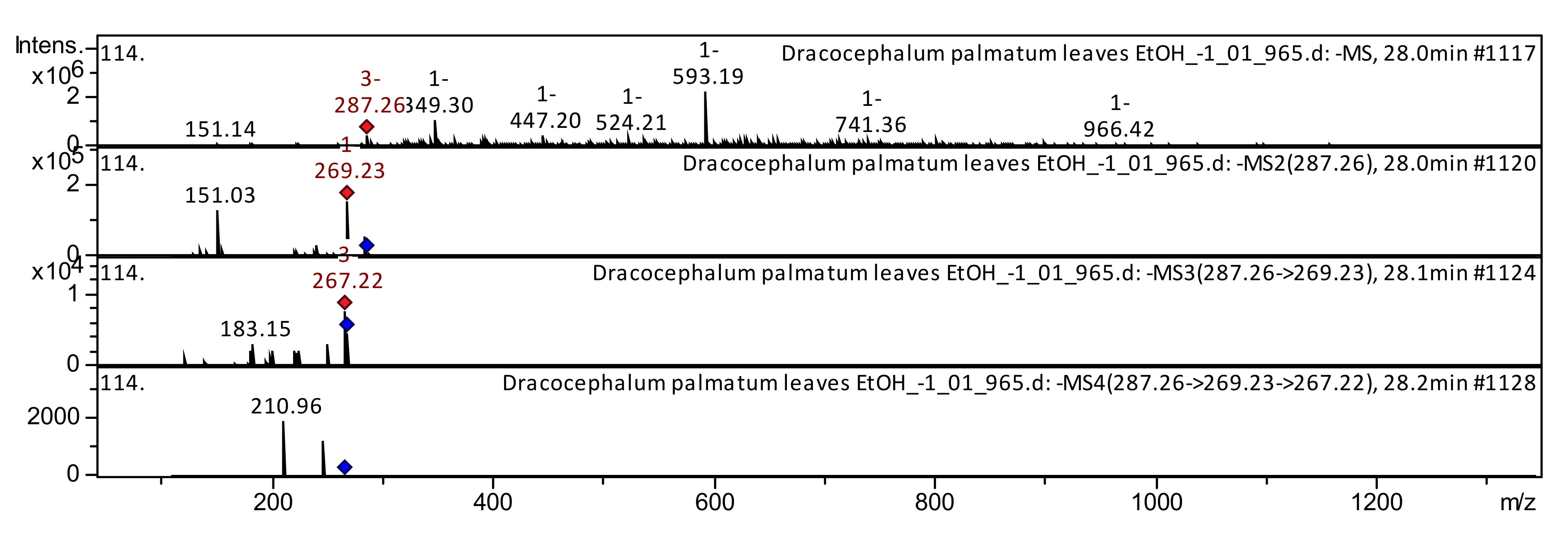

| 32 | D. palmatum | Flavonol | Dihydrokaempferol (aromadendrin, katuranin) | C15H12O6 | 288.2522 | 287 | 269; 151 | 267; 183 | 211 | F. glaucescens [28], Camellia kucha [34], Rhodiola rosea [51] | |

| 33 | D. palmatum | Flavonol | Dihydroquercetin (taxifolin, taxifoliol) | C15H12O7 | 304.2516 | 305 | 287 | 286; 186 | 185 | Andean blueberry [10], Eucalyptus [16], Camellia kucha [34], strawberry [40] | |

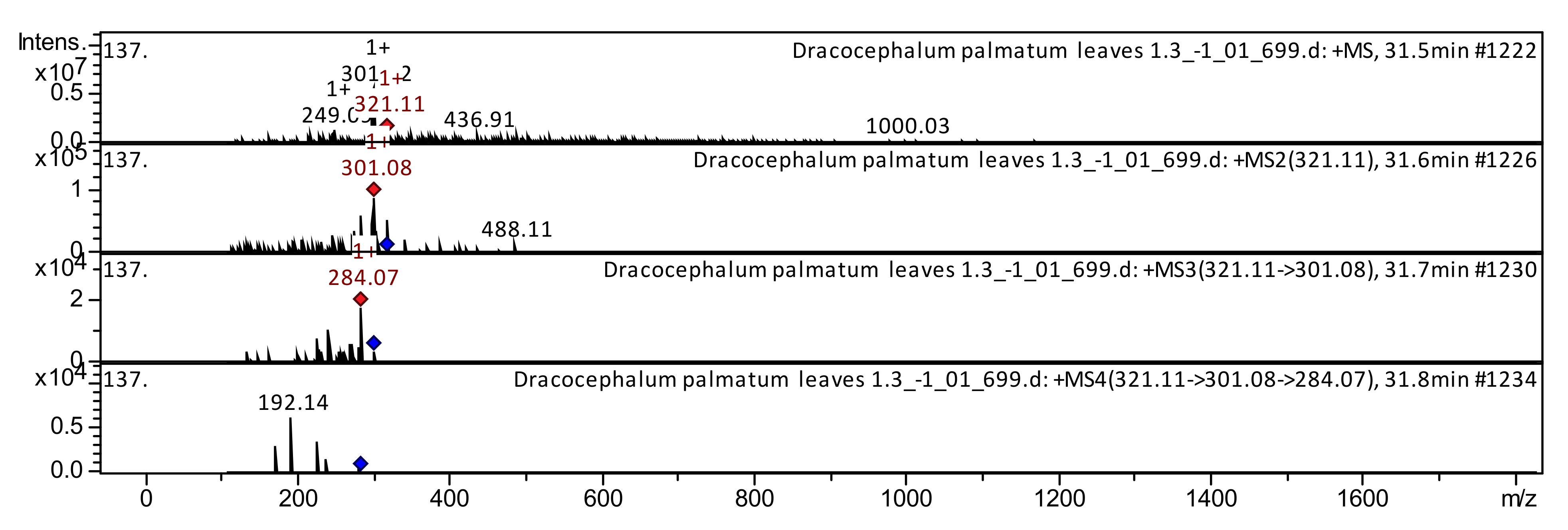

| 34 | D. palmatum | Flavonol | Ampelopsin (dihydromyricetin, ampeloptin) | C15H12O8 | 320.251 | 321 | 301 | 284 | 192 | Rhus coriaria [36], Impatiens glandulifera Royle [39] | |

| 35 | D. palmatum | Flavonol | Astragalin (kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, kaempferol-3-beta-monoglucoside) | C21H20O11 | 448.3769 | 447 | 285; 327 | 241 | 199 | Lonicera japonicum [11], Mexican lupine species [12], pear [25], Camellia kucha [34] | |

| 36 | D. ruyschiana | Flavonol | Kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | 462.3604 | 463 | 287 | 268; 169 | 241; 119 | A. cordifolia, G. linguiforme [28], Strawberry [35], Rhus coriaria [36] | |

| 37 | D. palmatum | Flavonol | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | 594.5181 | 593 | 285 | 241; 199 | 199 | Lonicera japonicum [11], Pear [25], Camellia kucha [34], strawberry [35], Rhus coriaria [36], | |

| 38 | D. ruyschiana | Flavan-3-ol | (Epi)catechin | C15H14O6 | 290.2681 | 291 | 273; 117 | 255; 145 | Andean blueberry [10], C. edulis [28], Camellia kucha [34], Radix polygoni multiflori [52], cranberry [53], | ||

| 39 | D. palmatum | Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin (+(−)gallocatechin) | C15H14O7 | 306.2675 | 307 | 289 | 259 | Licania ridigna [50], G. linguiforme [28], Vaccinium myrtillus [43], Rhodiola rosea [51] | ||

| 40 | D. palmatum | Flavanone | Naringenin (naringetol, naringenin) | C15H12O5 | 272.5228 | 273 | 153; 256 | 125 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Andean blueberry [10], Eucalyptus [16], Mexican lupine species [12], rapeseed petals [38] | ||

| 41 | D. palmatum | Flavanone | Eriodictyol (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxy-flavanone) | C15H12O6 | 288.2522 | 289 | 163; 271 | 145 | 117 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Andean blueberry [10], Eucalyptus [16], Mentha [24], peppermint [29] | |

| 42 | D. ruyschiana | Flavanone | Fustin (2,3-dihydrofistein) | C15H12O6 | 288.2522 | 287 | 269; 141 | 267; 185 | 249 | F. glaucescens, F. pottsii [28] | |

| 43 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavanone | Prunin (naringenin-7-O-glucoside) | C21H22O10 | 434.3934 | 433 | 271; 151 | 269; 151 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], rapeseed petals [38], tomato [54] | ||

| 44 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Flavanone | Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside (pyracanthoside, miscanthoside) | C21H22O11 | 450.3928 | 449 | 285; 151 | 243; 151 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Impatiens glandulifera Royle [39], peppermint [29], Mentha [24] | ||

| 45 | D. palmatum | Flavanone | Eriodictyol O-malonyl-hexoside | C24H24O14 | 536.4390 | 535 | 491; 287 | 287; 151 | 269; 151 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4] | |

| 46 | D. palmatum; D. ruyschiana | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 180.1574 | 181 | 135 | 119 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Eucalyptus [16], Triticum [46], Salvia miltiorrhiza [55] | ||

| 47 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Methylgallic acid (methyl gallate) | C8H8O5 | 184.1461 | 183 | 139 | 137 | 119 | Eucalyptus [16], papaya [35], Rhus coriaria [36] | |

| 48 | D. ruyschiana | Phenolic acid | Hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid | C10H12O4 | 196.1999 | 197 | 179 | 161 | 133 | F. herrerae, F. glaucescens [28] | |

| 49 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Ethyl caffeate (ethyl 3,4-dihydroxycinnamate) | C11H12O4 | 208.2106 | 207 | 179 | 135 | Lepechinia [56] | ||

| 50 | D. palmatum | Hydroxybenzoic acid | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA, benzoic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid) | C7H6O3 | 138.1207 | 139 | 122 | Bougainvillea [27], Triticum [46], Bituminaria [49], Vigna unguiculata [57], Eucalyptus globulus [58], | |||

| 51 | D. ruyschiana | Hydroxybenzoic acid | Ellagic acid (benzoic acid, elagostasine, lagistase, eleagic acid) | C14H6O8 | 302.1926 | 301 | 284 | 221 | 112 | Rhus coriaria [36], Eucalyptus [16], Eucalyptus globulus [58], Rubus occidentalis [59] | |

| 52 | D. palmatum | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Sinapic acid (trans-sinapic acid) | C11H12O5 | 224.21 | 225 | 206 | 138 | Andean blueberry [10], rapeseed petals [38], Triticum [46], Cranberry [53], Cherimoya [60] | ||

| 53 | D. ruyschiana | Hydroxycinnamic acid | 1-O-(4-coumaroyl)-glucose | C15H18O8 | 326.2986 | 325 | 145 | 117 | Cranberry [53], strawberry [40], Rubus occidentalis [59] | ||

| 54 | D. palmatum | Gallate ester | Beta-glucogallin (1-O-galloyl-beta-d-glucose, galloyl glucose) | C13H16O10 | 332.2601 | 333 | 314 | 271; 151 | 244; 159 | Strawberry [40,61], carao tree seeds [62] | |

| 55 | D. ruyschiana | Phenolic acid | Caffeoylshikimic acid (5-O-caffeoylshikimate) | C16H15O8 | 335.2855 | 335 | 179 | 135 | 133 | Andean blueberry [10], pear [25], passion fruits [35], Vaccinium myrtillus [43] | |

| 56 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Salvianolic acid G | C18H12O7 | 340.2837 | 341 | 296; 208 | 278; 208 | 235; 164 | Mentha [14], Salvia miltiorrhiza [55] | |

| 57 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | 1-caffeoyl-beta-D-glucose (caffeic acid-3-O-beta-D-glucoside) | C15H18O9 | 342.298 | 341 | 178; 119 | 135 | Passiflora incarnata [26], strawberry [40], Cranberry [53] | ||

| 58 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Phenolic acid | Caffeic acid-O-hexoside (caffeoyl-O-hexoside) | C15H18O9 | 342.298 | 341 | 178; 113 | pear [25], Cherimoya, papaya [35], Sasa veitchii [63] | |||

| 59 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Prolithospermic acid | C18H14O8 | 358.2990 | 359 | 341; 207 | 314; 267; 149 | Mentha [14], Salvia miltiorrhiza [55] | ||

| 60 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Rosmarinic acid | C18H16O8 | 360.3148 | 359 | 161 | 133 | Dracocephalum palmatum [4], Mentha [14], Zostera marina [21], peppermint [29], Salvia miltiorrhiza [55], Lepechinia [56] | ||

| 61 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Phenolic acid | Caffeic acid derivative | C16H18O9Na | 377.2985 | 377 | 341; 215 | 179 | Bougainvillea [27] | ||

| 62 | D. palmatum | Phenolic acid | Salvianic acid C | C18H18O9 | 378.3301 | 377 | 359; 315 | 289 | 229 | Salviae miltiorrhiza [55], Lepechinia [56] | |

| 63 | D. ruyschiana | Phenolic acid | 3,4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid (isochlorogenic acid B) | C25H24O12 | 516.4509 | 517 | 397 | 337; 135 | Lonicera japonicum [11], Pear [25], Stevia rebaudiana [64] | ||

| 64 | D. ruyschiana | Stilbene | Pinosylvin (3,5-stilbenediol, trans-3,5-dihydroxystilbene) | C14H12O2 | 212.2439 | 213 | 168 | 126 | Pinus sylvestris [50], Pinus resinosa [65] | ||

| 65 | D. ruyschiana | Stilbene | Resveratrol (trans-resveratrol, 3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene, stilbentriol) | C14H12O3 | 228.2433 | 229 | 142; 210 | 114 | A. cordifolia, F. glaucescens, F. herrerae [28], Radix polygoni multiflori [52] | ||

| 66 | D. palmatum | Lignan | Hinokinin | C20H18O6 | 354.3533 | 355 | 337; 189 | 319; 226 | Triticum aestivum L. [46], Rhodiola rosea [51], lignans [66] | ||

| 67 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Lignan | Dimethyl-secoisolariciresinol | C22H30O6 | 390.4700 | 391 | 373; 249; 121 | 355; 225 | 313; 226 | Lignans [66] | |

| 68 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Anthocyanidin | Petunidin | C16H13O7+ | 317.2702 | 318 | 166; 300 | 121 | A. cordifolia, C. edulis [28] | ||

| 69 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin O-pentoside | C20H19O10 | 419.3589 | 419 | 287 | 219 | 201 | Andean blueberry [10], Gaultheria mucronata, Gaultheria antarctica [60], Myrtle [67] | |

| 70 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Anthocyanidin | Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside (callistephin) | C21H21O10 | 433.3854 | 433 | 271 | 153; 225 | 171 | strawberry [61], Triticum aestivum [68], Rubus ulmifolius [69] | |

| 71 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Peonidin O-pentoside | C21H21O10 | 433.3854 | 433 | 301; 215; 145 | 229; 139 | Andean blueberry [10], Myrtle [67], | ||

| 72 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (cyanidin 3-O-beta-D-glucoside, kuromarin) | C21H21O11+ | 449.3848 | 449 | 287 | 153 | rice [22], Triticum [46,68], acerola [70] | ||

| 73 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Peonidin-3-O-glucoside | C22H23O11 + | 463.4114 | 463 | 301 | 286 | 258; 140 | Berberis ilicifolia, Berberis empetrifolia [60], Andean blueberry [10], strawberry [61], Triticum aestivum [68] | |

| 74 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-(acetyl)hexose | C23H23O12+ | 491.4215 | 491 | 287 | 245; 153 | 171 | Acerola [70] | |

| 75 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | C24H23O14 | 535.4310 | 535 | 287 | 285; 179 | 242; 153 | strawberry [40], strawberry [61], Triticum aestivum [68] | |

| 76 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-O-coumaroyl hexoside | C30H27O13 | 595.533 | 595 | 287 | 153 | Grape vine varieties [71] | ||

| 77 | D. palmatum | Anthocyanidin | 7-O-Methyl-delphinidin-3-O-(2″galloyl)-galactoside | C29H26O16 | 630.5071 | 631 | 317; 519 | Rhus coriaria [36] | |||

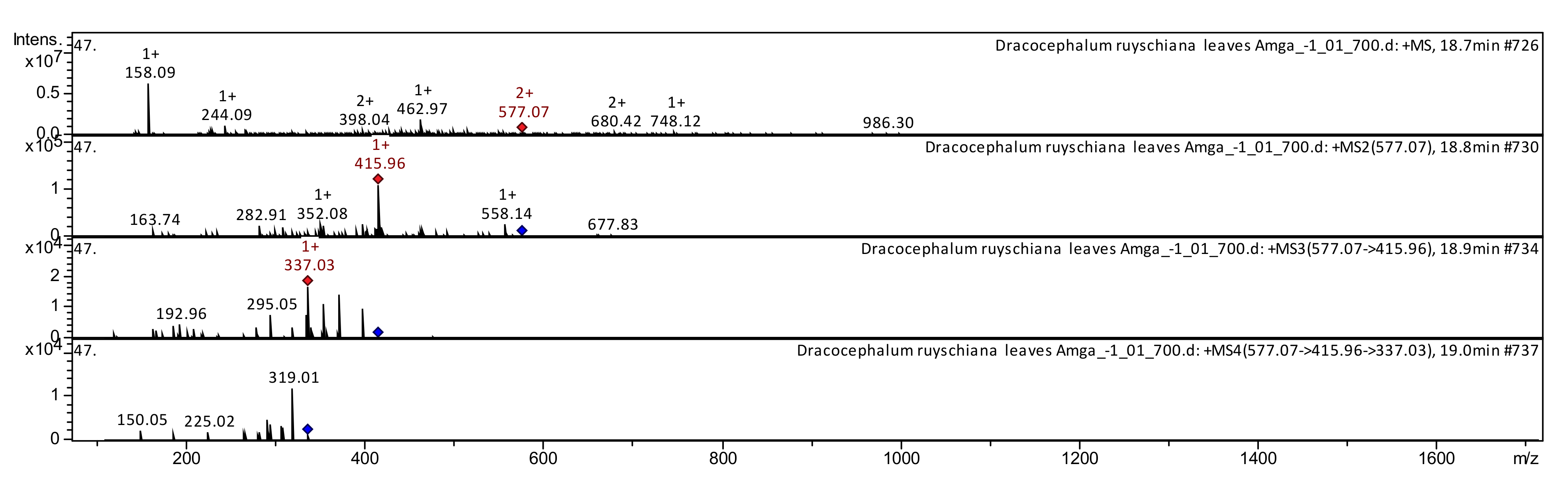

| 78 | D. ruyschiana | Condensed tannin | Procyanidin A-type dimer | C30H24O12 | 576.501 | 577 | 416; 352; 283; 164 | 337; 295; 193 | 319; 225; 150 | pear [25], Vaccinium myrtillus [43] | |

| OTHERS | |||||||||||

| 79 | D. palmatum | Amino acid | L-Leucine ((S)-2-amino-methylpentanoic acid) | C6H13NO2 | 131.1729 | 132 | 130 | Lonicera japonica [11], Camellia kucha [34], Potato leaves [37], Vigna unguiculata [57] | |||

| 80 | D. palmatum | Alpha-omega dicarboxylic acid | Hydroxymethylglutaric acid | C6H10O5 | 162.1406 | 163 | 145 | 117 | Potato leaves [37] | ||

| 81 | D. palmatum | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Perillic acid | C10H14O2 | 166.217 | 167 | 149 | 121 | Mentha [14] | ||

| 82 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Amino acid | L-tryptophan (tryptophan; (S)-tryptophan) | C11H12N2O2 | 204.2252 | 205 | 188 | 144 | 118 | Passiflora incarnata [26], Camellia kucha [34], Vigna unguiculata [57] | |

| 83 | D. palmatum | Aminoalkylindole | 5-Methoxydimethyltryptamine | C13H18N2O | 218.2948 | 219 | 201 | 159; 118 | Camellia kucha [34] | ||

| 84 | D. palmatum | Sesquiterpenoid | Epiglobulol ((−)-globulol) | C15H26O | 222.3663 | 223 | 205; 153 | 133 | Olive leaves [72] | ||

| 85 | D. palmatum | Omega-5 fatty acid | Myristoleic acid (cis-9-tetradecanoic acid) | C14H26O2 | 226.3550 | 227 | 209 | 139 | F. glaucescens [28] | ||

| 86 | D. palmatum | Medium-chain fatty acid | Hydroxydodecanoic acid | C12H22O5 | 246.3001 | 247 | 229 | 216 | F. glaucescens [28] | ||

| 87 | D. palmatum | Omega-3 unsaturated fatty acid | Hexadecatrienoic acid (hexadeca-2,4,6-trienoic acid) | C16H26O2 | 250.3764 | 251 | 233; 191 | 187 | F. glaucescens [28] | ||

| 88 | D. ruyschiana | Propionic acid | Ketoprofen | C16H14O3 | 254.2806 | 253 | 210 | 180 | Ginkgo biloba [73] | ||

| 89 | D. palmatum; D. ruyschiana | Ribonucleoside composite of adenine (purine) | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | 267.2413 | 268 | 136; 258 | Lonicera japonica [11] | |||

| 90 | D. palmatum | Sceletium alkaloid | O-Methyl-dehydrojoubertiamine | C17H21NO2 | 271.3541 | 272 | 256 | 242 | 226 | A. cordifolia [28] | |

| 91 | D. ruyschiana | Sceletium alkaloid | 4′-O-desmethyl mesembranol | C16H23NO3 | 277.3587 | 278 | 258 | 240 | 141 | A. cordifolia [28] | |

| 92 | D. palmatum | Omega-9 unsaturated fatty acid | Oleic acid (cis-9-octadecenoic acid, cis-oleic acid) | C18H34O2 | 282.4614 | 283 | 209; 114 | Sanguisorba officinalis [74], Pinus sylvestris [75] | |||

| 93 | D. palmatum | 2-Hydroxy fatty acid | 2-Hydroxyheptadecanoic acid | C17H34O3 | 286.4501 | 285 | 265 | 186 | F. pottsii [28] | ||

| 94 | D. palmatum | Alkaloid | Mesembrenol | C17H23NO3 | 289.3694 | 290 | 242; 122 | 184; 149 | Sceletium [76] | ||

| 95 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Diterpenoid | Tanshinone IIB ((S)-6-(hydroxymethyl)-1,6-dimethyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydrophenanthro[1,2-B]furan-10,11-dione) | C19H18O4 | 310.3438 | 311 | 283; 137 | 119 | Salviae miltiorrhiza [77] | ||

| 96 | D. palmatum | Alpha-omega dicarboxylic acid | Octadecanedioic acid (1,16-hexadecanedicarboxylic acid) | C18H34O4 | 314.4602 | 315 | 297; 179 | 212 | F. glaucescens [28] | ||

| 97 | D. palmatum | Unsaturated essential fatty acid | Oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid | C20H30O3 | 318.4504 | 319 | 300 | 282; 167 | 240 | F. pottsii [28] | |

| 98 | D. ruyschiana | Oxylipins | 9,10-Dihydroxy-8-oxooctadec-12-enoic acid (oxo-DHODE; oxo-dihydroxy-octadecenoic acid) | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | 327 | 229 | 209 | 183 | Bituminaria [49], Phyllostachys nigra [63] | |

| 99 | D. ruyschiana | Oxylipins | Trihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | 327 | 211; 171 | 183 | Potato leaves [37] | ||

| 100 | D. ruyschiana | Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid | Docosahexaenoic acid | C22H32O2 | 328.4883 | 327 | 309; 201 | 291; 171 | 273 | Marine extracts [78] | |

| 101 | D. palmatum, D. ruyschiana | Oxylipins | 13- Trihydroxy-octadecenoic acid (THODE) | C18H34O5 | 330.4596 | 329 | 229; 311 | 211 | 167 | Bituminaria [49], Sasa veitchii [63], Brassica oleracea [79] | |

| 102 | D. ruyschiana | Carotenoid | Beta-apo-12′-carotenal | C25H34O | 350.5369 | 351 | 259; 147 | 231; 145 | Carotenoids [80,81] | ||

| 103 | D. palmatum | Sterol | Stigmasterol (stigmasterin, beta-stigmasterol) | C29H48O | 412.6908 | 413 | 301 | 188 | A. cordifolia, F. pottsii [28], Olive leaves [72], Hedyotis diffusa [82] | ||

| 104 | D. ruyschiana | Carotenoid | Apocarotenal ((all-E)-beta-apo-caroten-8′-al) | C30H40O | 416.6380 | 417 | 399; 200 | 351 | 267 | Carica papaya [83] | |

| 105 | D. palmatum | Tetrahydroxyxanthen | Mangiferin | C19H18O11 | 422.3396 | 423 | 387; 238 | 345 | [84,85] | ||

| 106 | D. palmatum | Long-chain fatty acid | Nonacosanoic acid | C29H58O2 | 438.7696 | 439 | 395; 353; 245 | 245 | C. edulis [28] | ||

| 107 | D. palmatum | Anabolic steroid, androgen, androgen ester | Vebonol | C30H44O3 | 452.6686 | 453 | 435; 336; 226 | 336 | 209 | Rhus coriaria [36], Hylocereus polyrhizus [86] | |

| 108 | D. ruyschiana | Triterpenic acid | Oleanolic acid (oleanic acid, cariophyllin, astrantiagenin C, virgaureagenin B) | C30H48O3 | 456.7003 | 457 | 410; 325 | 342; 164 | C. edulis [28], Hedyotis diffusa [82], Folium Eriobotryae [87], Eleutherococcus [88] | ||

| 109 | D. palmatum | Indole sesquiterpene alkaloid | Sespendole | C33H45NO4 | 519.7147 | 520 | 184; 359 | 124 | Rhus coriaria [36], Hylocereus polyrhizus [86] | ||

| 110 | D. ruyschiana | Carotenoid | (Z)-lutein | C40H54O | 550.8562 | 551 | 533 | Physalis peruviana [89], carotenoids [90] | |||

| 111 | D. palmatum | Carotenoid | 5,8-epoxy-alpha-carotene | C40H56O | 552.872 | 553 | 536; 412; 207 | 299; 261 | Physalis peruviana [89] | ||

| 112 | D. ruyschiana | Carotenoid | Cryptoxanthin (beta-cryptoxanthin) | C40H56O | 552.872 | 553 | 535; 325; 223 | 517 | Carotenoids [81,91], Smilax aspera [92] | ||

| 113 | D. ruyschiana | Carotenoid | Violaxanthin (zeaxanthin dieperoxide, all-trans-violaxanthin) | C40H56O4 | 600.8702 | 601 | 364; 582 | 346; 202; 142 | 114 | Carotenoids [91] | |

| 114 | D. palmatum | Macrocyclic glycolipid lactone | Resinoside A | C31H34O13 | 614.5939 | 615 | 287; 203 | 162 | Eucalyptus genus [93] |

References

- Zakharova, V.I.; Kuznetsova, L.V. Abstract of the Flora of Yakutia: Vascular Plants; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2012; p. 272. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Karavaev, M.N. Summary of the Flora of Yakutia; Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences: Moscow, Russia, 1958; p. 189. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Danilova, N.S.; Borisova, S.Z.; Ivanova, N.S. Ornamental Plants of Yakutia: Atlas-Key; JSC “Fiton +”: Moscow, Russia, 2012; 248p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Chirikova, N.K.; Okhlopkova, Z.M.; Zulfugarov, I.S. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Tánara Ótó (Dracocephalum palmatum Stephan), a Medicinal Plant Used by the North-Yakutian Nomads. Molecules 2013, 18, 14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.N.; Park, I.; Sivtseva, S.; Okhlopkova, Z.; Zulfugarov, I.S.; Kim, S.-W. Dracocephalum palmatum Stephan extract induces caspase and mitochondria dependent apoptosis via Myc inhibition in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 2746–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.E.; Okhlopkova, Z.M.; Lim, C.; Cho, S.I. Dracocephalum palmatum Stephan extract induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells via the caspase-8-mediated extrinsic pathway. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakasy, A.; Fuzfai, Z.; Kursinszki, L.; Molnar-Perl, I.; Lemberkovics, E. Analysis of non-volatile constituents in Dracocephalum species by HPLC and GC-MS. Chromatographia 2006, 63, S17–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Jin, H.Z.; Qin, J.J.; Fu, J.J.; Hu, X.J.; Liu, J.H.; Yan, L.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.D. Chemical Constituents of Plants from the Genus Dracocephalum. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 1911–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selenge, E.; Murata, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Batkhuu, J.; Yoshizaki, F. Flavone tetraglycosides and benzyl alcohol glycosides from the mongolian medicinal plant Dracocephalum ruyschiana. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, S.E.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; Cerrato, A.; Giannelli Moneta, B.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Lagana, A. Andean Blueberry of the Genus Disterigma: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds. Separations 2021, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, C.; Zou, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Mei, Y.; Wei, L. Comparison of Multiple Bioactive Constituents in the Flower and the Caulis of Lonicera japonica Based on UFLC-QTRAP-MS/MS Combined with Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A.; Piasecka, A.; Garcia-Lopez, P.M.; Zamora-Natera, F.; Krajewski, P.; Marczak, L.; Kachlicki, P.; Stobiecki, M. Structural analysis and profiling of phenolic secondary metabolites of Mexican lupine species using LC–MS techniques. Phytochemistry 2013, 92, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, L. LC-MS/MS determination and pharmacokinetic study of seven flavonoids in rat plasma after oral administration of Cirsium japonicum DC. extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 158, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Xu, J.J.; Zhong, K.R.; Shang, Z.P.; Wang, F.; Wang, R.F.; Liu, B. Analysis of non-volatile chemical constituents of Menthae Haplocalycis herba by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry. Molecules 2017, 22, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Vazquez, M.; Estrada-Reyes, R.; Martinez-Laurrabaquio, A.; Lopez-Rubalcava, C.; Heinze, G. Neuropharmacological study of Dracocephalum moldavica L. (Lamiaceae) in mice: Sedative effect and chemical analysis of an aqueous extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, S.A.O.; Freire, C.S.R.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Neto, C.P. Characterization of Phenolic Components in Polar Extracts of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Bark by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9386–9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levandi, T.; Pussa, T.; Vaher, M.; Ingver, A.; Koppel, R. Principal component analysis of HPLC–MS/MS patterns of wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties. Food Chem. 2014, 63, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, Y.C.E.; Rebello Horta, C.C.; de Fatima Agra, M.; Siheri, W.; Boyd, M.; Igoli, J.O.; Gray, A.I.; de Fatima Vanderlei de Souza, M. New Sulphated Flavonoids from Wissadula periplocifolia (L.) C. Presl (Malvaceae). Molecules 2015, 20, 20161–20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Bajpai, V.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, K.R.; Kumar, B. Profiling of Gallic and Ellagic Acid Derivatives in Different Plant Parts of Terminalia arjuna by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS. Nat. Prod. Com. 2016, 11, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, B. HPLC–QTOF–MS/MS-based rapid screening of phenolics and triterpenic acids in leaf extracts of Ocimum species and their interspecies variation. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Tech. 2016, 39, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerstvedt, K.H.; Jordheim, M.; Andersen, O.M. Isolation and Identification of Flavonoids Found in Zostera marina Collected in Norwegian Coastal Waters. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gong, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Xiong, L.; Luo, J. A novel integrated method for large-scale detection, identification, and quantification of widely targeted metabolites: Application in the study of rice metabolomics. Mol. Plant. 2013, 6, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.P.; Pradhan, S.P.; Adhikari, K. LC-ESI-QTOF-MS for the Profiling of the Metabolites and in Vitro Enzymes Inhibition Activity of Bryophyllum pinnatum and Oxalis corniculata Collected from Ramechhap District of Nepal. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000155. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tian, T. Phytochemical Characterization of Mentha spicata L. Under Differential Dried-Conditions and Associated Nephrotoxicity Screening of Main Compound With Organ-on-a-Chip. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Tao, S.; Zhang, S. Characterization and Quantification of Polyphenols and Triterpenoids in Thinned Young Fruits of Ten Pear Varieties by UPLC-Q TRAP-MS/MS. Molecules 2019, 24, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozarowski, M.; Piasecka, A.; Paszel-Jaworska, A.; de Siqueira, A.; Chaves, D.; Romaniuk, A.; Rybczynska, M.; Gryszczynska, A.; Sawikowska, A.; Kachlicki, P.; et al. Comparison of bioactive compounds content in leaf extracts of Passiflora incarnata, P. caerulea and P. alata and in vitro cytotoxic potential on leukemia cell lines. Braz. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 28, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.A.; Abbas, F.A.; Refaat, S.; El-Shafae, A.M.; Fikry, E. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS Profile of The Ethyl Acetate Fraction of Aerial Parts of Bougainvillea ‘Scarlett O’Hara’ Cultivated in Egypt. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.R.; El-Hawary, S.S.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; El-Halawany, A.M. Identification of Chemopreventive Components from Halophytes Belonging to Aizoaceae and Cactaceae Through LC/MS –Bioassay Guided Approach. J. Chrom. Sci. 2021, 59, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodalska, A.; Kowalczyk, A.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Feska, I. Analysis of Polyphenolic Composition of a Herbal Medicinal Product—Peppermint Tincture. Molecules 2020, 25, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomford, N.E.; Dzobo, K.; Chopera, D.; Wonkam, A.; Maroyi, A.; Blackhurst, D.; Dandara, C. In vitro reversible and time-dependent CYP450 inhibition profiles of medicinal herbal plant extracts Newbouldia laevis and Cassia abbreviata: Implications for herb-drug interactions. Molecules 2016, 21, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirlini, M.; Mena, P.; Tassotti, M.; Herrlinger, K.A.; Nieman, K.M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Del Rio, D. Phenolic and volatile composition of a dry spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) extract. Molecules 2016, 21, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Pan, H.; Lu, Y.; Ding, L. An HPLC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of luteolin and its major metabolites in rat plasma and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41, 3830–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, U. Negative atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation low-energy collision activation mass spectrometry for the characterisation of flavonoids in extracts of fresh herbs. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 92, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Fang, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Pan, C.; Wu, H. Identification of key metabolites based on non-targeted metabolomics and chemometrics analyses provides insights into bitterness in Kucha [Camellia kucha (Chang et Wang) Chang]. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinola, V.; Pinto, J.; Castilho, P.C. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds of selected fruits from Madeira Island by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn and screening for their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Arraes-Roman, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. HPLC–DAD–ESI-MS/MS screening of bioactive components from Rhus coriaria L. (Sumac) fruits. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Perez, C.; Gomez-Caravaca, A.M.; Guerra-Hernandez, E.; Cerretani, L.; Garcia-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of Solanum tuberosum L. (potato) leaves T by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Molecules 2018, 112, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.-W.; Wang, S.-X.; Jia, L.-D.; Zhu, M.-C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, B.-J.; Yin, J.-M.; Lu, K.; Wang, R.; Li, J.-N.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Major Constituents in Different-Colored Rapeseed Petals by UPLC−HESI-MS/MS. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11053–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, M.N.; Winterhalter, P.; Jerz, G. Flavonoids from the flowers of Impatients glandulifera Royle isolated by high performance countercurrent chromatography. Phytochem. Anal. 2016, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhineva, K.; Karenlampi, S.O.; Aharoni, A. Resent Advances in Strawberry Metabolomics. Genes Genomes Genom. 2011, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, A.; Matros, A.; Hartmann, A.; Arapitsas, P.; Dehmer, K.J.; Martens, S.; Mock, H.P. Metabolite profiling of red and blue potatoes revealed cultivar and tissue specific patterns for anthocyanins and other polyphenols. Planta 2017, 246, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjany, N.; Senker, J.; Brandt, S.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. In Vivo Consumption of Cranberry Exerts ex Vivo Antiadhesive Activity against FimH-Dominated Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A Combined in Vivo, ex Vivo, and in Vitro Study of an Extract from Vaccinium macrocarpon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8804–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujor, O.-C. Extraction, Identification and Antioxidant Activity of the Phenolic Secondary Metabolites Isolated from the Leaves, Stems and Fruits Oo Two Shrubs of the Ericaceae Family. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Iasi, Iași, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopoeia of the Eurasian Economic Union, Approved by Decision of the Board of Eurasian Economic Commission No. 100 Dated August 11, 2020. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/texnreg/deptexreg/LSMI/Documents/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%8F%20%D0%A1%D0%BE%D1%8E%D0%B7%D0%B0%2011%2008.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.; Omar, A. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Sandhir, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, A.; Jachak, S.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, J.; Roy, J. Comparison analysis of phenolic compound characterization and their biosynthesis genes between two diverse bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties differing for chapatti (unleavened flat bread) quality. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, P.; Sun, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Harnly, J.M.; Chen, P. Comprehensive characterization of C-glycosyl flavones in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germ using UPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMSn and mass defect filtering. J. Mass Spectr. 2016, 51, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallmann, J.; Schweiger, R.; Pons, C.A.; Müller, C. Wheat growth, applied water use efficiency and flag leaf metabolome under continuous and pulsed deficit irrigation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorent-Martinez, E.J.; Spinola, V.; Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. HPLC-ESI-MSn characterization of phenolic compounds, terpenoid saponins, and other minor compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 69, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, M.A.; Silva Alves, A.I.; Andrade, J.C.; Leite-Andrade, M.C.; Lucas dos Santos, A.T.; de Oliveira, T.F.; dos Santos, F.; Silva Buonafina, M.D. Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of the Licania Rigida Leaf Ethanolic Extract against Biofilms Formed by Candida Sp. Isolates in Acrylic Resin Discs. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharenko, A.M.; Razgonova, M.P.; Pikula, K.S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Simultaneous determination of 78 compounds of Rhodiola rosea extract using supercritical CO2-extraction and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS spectrometry. HINDAWY. Biochem. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9957490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.-W.; Li, J.; Gao, X.-M.; Amponsem, E.; Kang, L.-Y.; Hu, L.-M.; Zhang, B.-L.; Chang, Y.-X. Simultaneous determination of stilbenes, phenolic acids, flavonoids and anthraquinones in Radix polygoni multiflori by LC–MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 62, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vorsa, N.; Harrington, P.; Chen, P. Nontargeted Metabolomic Study on Variation of Phenolics in Different Cranberry Cultivars Using UPLC-IM−HRMS. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12206–12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Jauregui, O.; Medina-Remón, A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Evaluation of a method to characterize the phenolic profile of organic and conventional tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3373–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.-W.; Lau, K.-M.; Hon, P.-M.; Mak, T.C.W.; Woo, K.-S.; Fung, K.-P. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Caffeic Acid Derivatives from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.A.; Villena, G.K.; Rodriguez, E.F. Phytochemical profile and rosmarinic acid purification from two Peruvian Lepechinia Willd. species (Salviinae, Mentheae, Lamiaceae). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchuk, I.; Shelenga, T.; Gurkina, M.; Miroshnichenko, E.; Burlyaeva, M. Composition of Primary and Secondary Metabolite Compounds in Seeds and Pods of Asparagus Bean (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) from China. Molecules 2020, 25, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.; Lei, Q.; Zang, N.; Zhang, H. A Strategy Based on GC-MS/MS, UPLC-MS/MS and Virtual Molecular Docking for Analysis and Prediction of Bioactive Compounds in Eucalyptus Globulus Leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, L.; Wyzgoski, F.J.; Scheerens, J.C.; Chanon, A.M.; Reese, R.N.; Smiljanic, D.; Wesdemiotis, C.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Riedl, K.M.; Rinaldi, P.L. Nonanthocyanin secondary metabolites of black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) fruits: Identification by HPLC-DAD, NMR, HPLC-ESI-MS, and ESI-MS/MS analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12032–12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Vergara, C.; von Baer, D.; Zapata, M.; Hitschfeld, A.; Obando, L.; Mardones, C. Anthocyanin profiles in south Patagonian wild berries by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Slovin, J.; Chen, P. Profiling polyphenols of two diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca) inbred lines using UHPLC-HRMSn. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia Fuentes, J.A.; Lopez-Salas, L.; Borras-Linares, I.; Navarro-Alarcon, M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Lozano-Sanchez, J. Development of an Innovative Pressurized Liquid Extraction Procedure by Response Surface Methodology to Recover Bioactive Compounds from Carao Tree Seeds. Foods 2021, 10, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoyweghen, L.; De Bosscher, K.; Haegeman, G.; Deforce, D.; Heyerick, A. In Vitro Inhibition of the Transcription Factor NF-kB and Cyclooxygenase by Bamboo Extracts. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shaari, K. LC–MS metabolomics analysis of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni leaves cultivated in Malaysia in relation to different developmental stages. Phytochem. Analys. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, F.; Legault, J.; Lavoie, S.; Mshvildadze, V.; Pichette, A. Isolation and Identification of Cytotoxic Compounds from the Wood of Pinus resinosa. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, P.C.; Backman, M.J.; Kronberg, L.A.; Smeds, A.I.; Sjoholm, R.E. Identification of lignans by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectr. 2008, 43, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Urso, G.; Sarais, G.; Lai, C.; Pizza, C.; Montoro, P. LC-MS based metabolomics study of different parts of myrtle berry from Sardinia (Italy). J. Berry Res. 2017, 7, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Chawla, M.; Chunduri, V.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Kaur, N.; Kumar, A.; Mundey, J.K.; Saini, M.K. Transfer of grain colors to elite wheat cultivars and their characterization. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 71, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.P.; Pereira, E.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Alves, M.J.; Pereira, O.R.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Rubus ulmifolius Schott fruits: A detailed study of its nutritional, chemical and bioactive properties. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera de Rosso, V.; Hillebrand, S.; Cuevas Montilla, E.; Bobbio, F.O.; Winterhalter, P.; Mercadante, A.Z. Determination of anthocyanins from acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) and ac-ai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) by HPLC–PDA–MS/MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelic, M.M.; Dabic Zagorac, D.C.; Davidovic, C.M.; Todic, S.R.; Beslic, Z.S.; Gasic, U.M.; Tesic, Z.L.; Natic, M.M. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds in berry skin, pulp, and seeds in 13 grapevine varieties grown in Serbia. Food. Chem. 2016, 211, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Montenegro, Z.J.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Mendiola, J.A.; Ibanez, E.; Cifuentes, A. Extraction and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Terpenes Recovered from Olive Leaves Using a New Adsorbent-Assisted Supercritical CO2 Process. Foods 2021, 10, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ding, C.; Ge, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Zhi, X. Simultaneous determination of ginkgolides A, B, C and bilobalide in plasma by LC–MS/MS and its application to the pharmacokinetic study of Ginkgo biloba extract in rats. J. Chromatogr. B 2008, 864, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Oh, S.; Noh, H.B.; Ji, S.; Lee, S.H.; Koo, J.M.; Choi, C.W.; Jhun, H.P. In Vitro Antioxidant and Anti-Propionibacterium acnes Activities of Cold Water, Hot Water, and Methanol Extracts, and Their Respective Ethyl Acetate Fractions, from Sanguisorba officinalis L. Roots. Molecules 2018, 23, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeberg, D.; Flate, P.-O.; Eikenes, M.; Fongen, M.; Naess-Andresen, C.F. Qualitative and quantitative determination of extractives in heartwood of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) by gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1109, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnala, S.; Kanfer, I. Medicinal use of Sceletium: Characterization of Phytochemical Components of Sceletium Plant Species using HPLC with UV and Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 18, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yang, S.T.; Wu, X.; Rui, W.; Guo, J.; Feng, Y.F. UPLC/Q-TOF-MS analysis for identification of hydrophilic phenolics and lipophilic diterpenoids from Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae. Acta Chromatogr. 2015, 27, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.C.; Dunn, S.R.; Altvater, J.; Dove, S.G.; Nette, G.W. Rapid Identification of Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in a Marine Extract by HPLC-MS Using Data-Dependent Acquisition. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 5976–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.K.; Ha, J.S.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Guo, T.J.; Lee, U.; Kim, D.-O.; Heo, H.J. Antiamnesic Effect of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) Leaves on Amyloid Beta (Aβ)1-42-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2016, 64, 3353–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, A.Z.; Rodrigues, D.B.; Petry, F.C.; Barros Mariutti, L.R. Carotenoid esters in foods—A review and practical directions on analysis and occurrence. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 830–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, M.; Giuffrida, D.; Salafia, F.; Giofre, S.V.; Mondello, L. Carotenoids and apocarotenoids determination in intact human blood samples by online supercritical fluid extraction-supercritical fluid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharma. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 1032, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, P.; Liu, B.; Wei, L.; Xu, Y. Simultaneous determination of fourteen compounds of Hedyotis diffusa Willd extract in rats by UHPLC-MS/MS method: Application to pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 159, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Abia, S.; Lobo-Rodrigo, G.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Pilar Cano, M. Carotenoid and Carotenoid Ester Profile and Their Deposition in Plastids in Fruits of New Papaya (Carica papaya L.) Varieties from the Canary Islands. Roots. Foods 2021, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geodakyan, S.V.; Voskoboinikova, I.V.; Tjukavkina, N.A.; Sokolov, S.J. Experimental pharmacokinetics of biologically active plant phenolic compounds. I. Pharmacokinetics of mangiferin in the rat. Phytother. Res. 1992, 6, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Determination of mangiferin in rat plasma by liquid–liquid extraction with UPLC–MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 51, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Shi, M.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wen, X. Metabolic Profiling of Pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) during Fruit Development and Maturation. Molecules 2019, 24, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-X.; Zhu, H.; Cai, X.-P.; He, D.-D.; Hua, J.-L.; Ju, J.-M.; Lv, H.; Ma, L.; Li, W.-L. Simultaneous determination of five triterpene acids in rat plasma by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry and its application in pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of Folium Eriobotryae effective fraction. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2015, 29, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Schmiech, M.; El Gaafary, M.; Zhang, X.; Syrovets, T.; Simmet, T. A comparative study on root and bark extracts of Eleutherococcus senticosus and their effects on human macrophages. Phytomedicine 2020, 68, 153181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzbach, L.; Pfeiffer, A.; Weber, F.; Schieber, A. Characterization of carotenoid profiles in goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.) fruits at various ripening stages and in different plant tissues by HPLC-DAD-APCI-MSn. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, F.C.; Mercadante, A.Z. Composition by LC-MS/MS of New Carotenoid Esters in Mango and Citrus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8207–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Jia, K.-P.; Wang, J.Y.; Al-Babili, S. A rapid LC-MS method for qualitative and quantitative profiling of plant apocarotenoids. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1035, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Pelayo, R.; Homero-Mendez, D. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Carotenoids and Their Esters from Sarsaparilla (Smilax aspera L.) Berries. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 60, 8225–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskes, A.M.; Goodger, J.Q.D.; Tsegay, S.; Quach, T.; Williams, S.J.; Woodrow, I.E. Localization of Oleuropeyl Glucose Esters and a Flavanone to Secretory Cavities of Myrtaceae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Class of Compounds | Identified Compounds | Formula | D. ruyschiana | D. palmatum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flavone | Apigeninidin | C15H11O4 | ||

| 2 | Flavone | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | ||

| 3 | Flavone | Negletein (5,6-dihydroxy-7-methoxyflavone) | C16H12O5 | ||

| 4 | Flavone | Acacetin (linarigenin, buddleoflavonol) | C16H12O5 | ||

| 5 | Flavone | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | ||

| 6 | Flavone | Apigenin-7, 4′-dimethyl ether | C17H14O5 | ||

| 7 | Flavone | Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | ||

| 8 | Flavone | Salvigenin | C18H16O6 | ||

| 9 | Flavone | Nevadensin | C18H16O7 | ||

| 10 | Flavone | Apigenin 7-sulfate | C15H10O8S | ||

| 11 | Flavone | Chrysin 6-C-glucoside | C21H20O9 | ||

| 12 | Flavone | Chrysin glucuronide | C21H18O10 | ||

| 13 | Flavone | Apigenin-5-O-glucoside | C21H20O10 | ||

| 14 | Flavone | Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | C21H20O10 | ||

| 15 | Flavone | Apigenin 7-O-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | ||

| 16 | Flavone | Acacetin 7-O-glucoside | C22H22O10 | ||

| 17 | Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside | C22H22O10 | ||

| 18 | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-glucoside (cynaroside, luteoloside) | C21H20O11 | ||

| 19 | Flavone | Acacetin 7-O-beta-D-glucuronide | C22H20O11 | ||

| 20 | Flavone | Luteolin-7-O-beta-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | ||

| 21 | Flavone | Diosmetin-7-O-beta-glucoside | C22H22O11 | ||

| 22 | Flavone | Luteolin O-acetyl-hexoside | C23H22O12 | ||

| 23 | Isoflavone | Apigenin 7-O-beta-D-(6″-O-malonyl)-glucoside | C24H22O13 | ||

| 24 | Flavone | Acacetin 8-C-glucoside malonylated | C25H24O13 | ||

| 25 | Isoflavone | 2′-Hydroxygenistein O-glucoside malonylated | C24H22O14 | ||

| 26 | Flavone | Luteolin 7-O-beta-D-(6″-O-malonyl)-glucoside | C24H22O14 | ||

| 27 | Flavone | Acacetin C-glucoside methylmalonylated | C26H26O13 | ||

| 28 | Flavone | Apigenin 8-C-hexoside-6-C-pentoside | C26H28O14 | ||

| 29 | Flavone | Apigenin 8-C-pentoside-6-C-hexoside | C26H28O14 | ||

| 30 | Flavone | Apigenin 6-C-[6″-acetyl-2″-O-deoxyhexoside]-glucoside | C29H32O15 | ||

| 31 | Flavonol | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | ||

| 32 | Flavonol | Dihydrokaempferol (aromadendrin; katuranin) | C15H12O6 | ||

| 33 | Flavonol | Dihydroquercetin (taxifolin, taxifoliol) | C15H12O7 | ||

| 34 | Flavonol | Ampelopsin (dihydromyricetin, ampeloptin) | C15H12O8 | ||

| 35 | Flavonol | Astragalin (kaempferol 3-O-glucoside; kaempferol-3-beta-monoglucoside, astragaline) | C21H20O11 | ||

| 36 | Flavonol | Kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | ||

| 37 | Flavonol | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | ||

| 38 | Flavan-3-ol | (epi)catechin | C15H14O6 | ||

| 39 | Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin [+(−)gallocatechin] | C15H14O7 | ||

| 40 | Flavanone | Naringenin (naringetol, naringenin) | C15H12O5 | ||

| 41 | Flavanone | Eriodictyol (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxy-flavanone) | C15H12O6 | ||

| 42 | Flavanone | Fustin (2,3-dihydrofistein) | C15H12O6 | ||

| 43 | Flavanone | Prunin (naringenin-7-O-glucoside) | C21H22O10 | ||

| 44 | Flavanone | Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside | C21H22O11 | ||

| 45 | Flavanone | Eriodictyol O-malonyl-hexoside | C24H24O14 | ||

| 46 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | ||

| 47 | Phenolic acid | Methylgallic acid (methyl gallate) | C8H8O5 | ||

| 48 | Phenolic acid | Hydroxy methoxy dimethylbenzoic acid | C10H12O4 | ||

| 49 | Phenolic acid | Ethyl caffeate (ethyl 3,4-dihydroxycinnamate) | C11H12O4 | ||

| 50 | Hydroxybenzoic acid | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | ||

| 51 | Hydroxybenzoic acid | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | ||

| 52 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Sinapic acid (trans-sinapic acid) | C11H12O5 | ||

| 53 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | 1-O-(4-Coumaroyl)-glucose | C15H18O8 | ||

| 54 | Gallate ester | Beta-glucogallin | C13H16O10 | ||

| 55 | Phenolic acid | Caffeoylshikimic acid (5-O-caffeoylshikimate) | C16H15O8 | ||

| 56 | Phenolic acid | Salvianolic acid G | C18H12O7 | ||

| 57 | Phenolic acid | 1-caffeoyl-beta-D-glucose | C15H18O9 | ||

| 58 | Phenolic acid | Caffeic acid-O-hexoside (caffeoyl-O-hexoside) | C15H18O9 | ||

| 59 | Phenolic acid | Prolithospermic acid | C18H14O8 | ||

| 60 | Phenolic acid | Rosmarinic acid | C18H16O8 | ||

| 61 | Phenolic acid | Caffeic acid derivative | C16H18O9Na | ||

| 62 | Phenolic acid | Salvianic acid C | C18H18O9 | ||

| 63 | Phenolic acid | 3,4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid (Isochlorogenic acid B) | C25H24O12 | ||

| 64 | Stilbene | Pinosylvin | C14H12O2 | ||

| 65 | Stilbene | Resveratrol | C14H12O3 | ||

| 66 | Lignan | Hinokinin | C20H18O6 | ||

| 67 | Lignan | Dimethyl-secoisolariciresinol | C22H30O6 | ||

| 68 | Anthocyanidin | Petunidin | C16H13O7+ | ||

| 69 | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin O-pentoside | C20H19O10 | ||

| 70 | Anthocyanidin | Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside (callistephin) | C21H21O10 | ||

| 71 | Anthocyanidin | Peonidin O-pentoside | C21H21O10 | ||

| 72 | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (cyanidin 3-O-beta-D-glucoside, kuromarin) | C21H21O11+ | ||

| 73 | Anthocyanidin | Peonidin-3-O-glucoside | C22H23O11+ | ||

| 74 | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-(acetyl)hexose | C23H23O12+ | ||

| 75 | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | C24H23O14 | ||

| 76 | Anthocyanidin | Cyanidin 3-O-coumaroyl hexoside | C30H27O13 | ||

| 77 | Anthocyanidin | 7-O-Methyl-delphinidin-3-O-(2″galloyl)-galactoside | C29H26O16 | ||

| 78 | Condensed tannin | Procyanidin A-type dimer | C30H24O12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okhlopkova, Z.M.; Razgonova, M.P.; Pikula, K.S.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Piekoszewski, W.; Manakov, Y.A.; Ercisli, S.; Golokhvast, K.S. Dracocephalum palmatum S. and Dracocephalum ruyschiana L. Originating from Yakutia: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031766

Okhlopkova ZM, Razgonova MP, Pikula KS, Zakharenko AM, Piekoszewski W, Manakov YA, Ercisli S, Golokhvast KS. Dracocephalum palmatum S. and Dracocephalum ruyschiana L. Originating from Yakutia: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(3):1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031766

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkhlopkova, Zhanna M., Mayya P. Razgonova, Konstantin S. Pikula, Alexander M. Zakharenko, Wojciech Piekoszewski, Yuri A. Manakov, Sezai Ercisli, and Kirill S. Golokhvast. 2022. "Dracocephalum palmatum S. and Dracocephalum ruyschiana L. Originating from Yakutia: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds" Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031766

APA StyleOkhlopkova, Z. M., Razgonova, M. P., Pikula, K. S., Zakharenko, A. M., Piekoszewski, W., Manakov, Y. A., Ercisli, S., & Golokhvast, K. S. (2022). Dracocephalum palmatum S. and Dracocephalum ruyschiana L. Originating from Yakutia: A High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach for the Comprehensive Characterization of Phenolic Compounds. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031766