Abstract

The problem of focusing only on the efficiency of an ICTs’ digital convergence in technology-oriented smart city construction has been raised. To address this problem, Plan Smart City Comprehensive Plan is in progress, excluding play spaces in public spaces where the city and users communicate directly or indirectly. In addition, when looking at Christopher Alexander’s 253 pattern languages, which many scholars and experts consider as a study guide for urban planning projects, there is no design alternative for ICTs’ digital convergence for future smart cities. Therefore, in this study, we propose a 4th plan model for ICTs’ future smart city development regarding digital technology and a place-oriented digilog strategic plan. This model proposal is applied to an actual project where the user and the space can interact based on the user’s behavior analysis using the keywords of participation, sharing, and cooperation in the public play space. This study aims to verify the rational method of the ICTs’ smart city Future 4th plan model alternative. There is a strategic plan for ICTs’ participatory media user interaction in a public play space in which: 1. the way people behave in the space; 2. the way people interact with the space; 3. the way people accept the actions of others for entertainment and enjoyment. This study can contribute as a strategic plan for ICTs’ participatory media-user interaction in a public play space; it can contribute to the rational design of the presentation of digilog strategic planning.

1. Introduction

At this point in the AI era, the direction of the development of the entire global village to digitalize generational change is already in full swing. In almost every industry, the pace of digital transformation has accelerated at an unprecedented rate [1]. However, this change does not foreshadow the disappearance of analog. Instead, analog is expected to coexist or converge with digital, while developing into digital convergence. However, although new alternatives are being proposed for the construction of future smart cities in countries around the world, most of the future urban planning proposals are solutions to urban problems in which only hardware aspects are considered. This is because it is a digital convergence service in which only ICTs, such as construction, transportation, safety, and the environment, are grafted. In addition, reckless digital services do not harmonize with the surrounding environment and become visual pollution that worsens the aesthetics of the city. Currently, the architectural façade is a large media screen function, and its main role is to deliver visual information. The entire exterior wall of a building was strategized with LED mapping digital technology, media art, and commercial advertising panels. This idea focuses only on the efficiency of ICTs’ digital convergence and raises the issue of technology-oriented smart city construction so that it can become a center of openness, participation, sharing, and cooperation, along with being technology-oriented [2]. It is time to study ICTs’ future smart city model in regards to public space and its users.

However, in the current Korean smart city comprehensive plan, plans for public spaces, which are communication media for users, are excluded. Additionally, most of Alexander Christopher’s previous studies, to which urban planning researchers looked as the criteria for urban design guidelines, found a rational basis for the theory through physical network analysis that hardware for buildings and facilities uses pattern language. This research revealed that in Alexander Christopher’s pattern language, there was no guiding plan for the media public play space, which is the standard for future smart city plans in regards to public space and design guidelines; the proposed public entertainment space plan is differentiated from previous studies by the presentation of an actual project plan.

Particularly, based on Alexander Christopher’s design guidelines for pattern language, this study analyzes the utility of public spaces where users can directly or indirectly communicate in existing public spaces. At this time, we find a rational connection between the public play space of the media, which is not presented in Alexander Christopher’s design guidelines for pattern language. Through this connection, the future smart city comprehensive plan, based on analyzing the user’s space behavior in which ICTs’ digital convergence is grafted into the existing public space, we propose a plan for the public play space [2]. This suggests the rationality of the research model by planning and producing ICTs’ digital convergence media content that enhances communication between cities and humans through the combination of digital technology and human touch, by actual project planning and production in urban regeneration public spaces. This is a place of idleness (communication), where ICTs’ futuristic smart city leads users to natural participation in the public play space (openness). In addition, by proposing a participatory, interactive media medium through which city residents can form a partnership (cooperation), we intend to present study on the place of communication in a public play space. In many aspects, this study aims to investigate the effects of the explanation derived from the problem of the technology center of a smart city—it proposes the ICTs’ future smart city 4th plan model for the place-oriented digilog strategic plan.

2. Media City of Public Space and Spatiality of Play Space

2.1. Christopher Alexander’s Notion

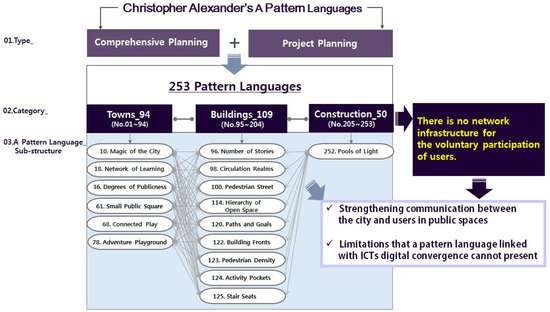

Christopher Alexander (A Pattern Language, Oxford University Press, 1977, and The Timeless Way of Building, Oxford University Press, 1979) found that architectural design patterns were derived in 253 steps as a methodology for environmental factors related to human behavior. This design pattern analyzes and reviews the form of language used in architecture and urban planning [3] and presents the meaning of the design formative language as a guide for design theory to create a building or city. This is primarily divided into three categories in the language pattern, consisting of 94 cities, 109 architectures, and 50 small-scale sub-structure networks, considering the interconnection of detailed patterns for each hierarchy. The pattern association of this network structure is a category index type language, and it cannot be used an index pattern language with one complete association. Because this is comprehensive planning or project planning used during urban planning (Alexander, 1988), the city and community are contextually defined through experience and observation [2,4] (Figure 1). Until now, most of the research on pattern language has been limited to analyzing the characteristics perceived by the eyes of physical indexing facilities, such as hardware facilities in an urban environment, and revealing the physical formation index factors [3]. In other words, it is a theoretical sub-structure network of hardware index pattern language for buildings and facilities divided into three categories. It has been used as a guide for comprehensive rational urban planning in the existing urban space design method. This illustrates the point that until the present, many researchers and planners have used Christopher Alexander’s architectural design patterns as the theory of the value of samples when studying urban environments and architectural spaces. However, in the present and future urban spatial planning, which has entered the 4th industrial age, when looking at the guidelines for the 253 physical index design patterns, the presentation of spatial media planning needs to be improved.

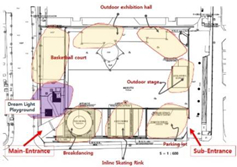

Figure 1.

A total of 16 out of 253 pattern languages were derived for strengthening communication between the city and users in public spaces.

2.2. The Spatiality of a Public Play Space with a Pattern Language

The pattern language does not contain the physical and contextual network infrastructure elements that create voluntary participation in the urban planning of the public space as analog urban planning, which is traditional urban planning. In other words, there are physical planning hardware guidelines but no infrastructure software elements in which users can participate. First, the interrelationship between public space and users was examined as a place-oriented strategy of openness, participation, sharing, and cooperation for 253 pattern languages based on existing urban planning standards [2]. As a result, the physical factor for public play space suggested by Christopher Alexander was a street network centered on private buildings and architectural spaces (Figure 1). This was the application of pattern language for activating the street environment with a fixed architectural infrastructure and facilities, excluding physical factors in which users voluntarily participate. Therefore, it is insufficient to reflect the user’s requirements according to the spatial characteristics of a pattern language [3]. This phenomenon is a contextual evolution in which 253 pattern languages did not form the basis for user experience and observation through the comprehensive or business plan of urban planning [4]. In addition, 16 out of 253 pattern languages were derived from examining the interconnection of cooperation and joint participation in using the 253 pattern languages, according to the region’s characteristics, to strengthen communication between the city and the users in public spaces (Figure 1).

In other words, in the current urban spatial planning, the medium of communication between users and public space is the digital convergence media façade. It has the advantage of being formed so that it can be maintained and communicated. These advantages include that attachment to a place arises when there is a genuine ability to communicate within the space [5]. At this time, since how to respond to the form or environment needs to be clarified, the development of digital convergence media technology plays a role in the connection of sympathy and understanding of the communication system in public space planning. The interactive media public space created based on this aspect should show a new method different from the conventional method used to create the city environment [5].

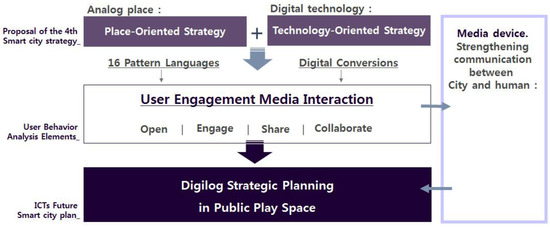

In current and future smart city planning, the new method should emphasize the digital convergence media interaction, which is the subject of direct user participation and information sharing in ICTs’ convergence, according to urban problem solving and the quality improvement of the lives of city residents (stated in Washburn and Sindhu, 2010) [2]. However, many smart city projects in Korea are being discussed as a focused issue centered on construction and user non-participation technology [2]. This focus on the efficiency of technology and communication between people and various exchanges between people and things, and things and things, along with the evolution of ICTs’, are intensive tasks to be dealt with in smart cities in the future. Therefore, as it evolves from a user non-participation technology-oriented strategy to a user engaged, place-oriented strategy, it is necessary to define a digilog-participatory media interaction relationship [6]. This should not be hardware technology-oriented but a software-connected people-centered, urban network regarding the construction infrastructure to solve urban problems [7] (Figure 2). At this point, when the digital environment is emphasized in the ICTs’ smart city platform planned by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport of Korea, the projects in progress are

Figure 2.

ICTs’ smart city platform planned by the Korean Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport.

- Smart infrastructure: digital twin, data AI center, smart IoT establishment.

- Smart service: smart transportation, healthcare, education, energy, environment, safety, and living (Figure 2).

In this respect, the limitations of the 3rd smart city plan should be considered in the ICTs’ Future 4th smart city plan, a model to strengthen communication between cities and humans using 16 pattern languages derived from existing public spaces (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This is a model plan in which user participation is the subject, and digital convergence media-interaction is strengthened. As a method for verifying this, a public play space based on user behavior analysis was established, with user participation-type digital technology and place-oriented open participation, sharing, and cooperation software keywords in 16 hardware pattern languages (Figure 3). In particular, existing public space and ICTs’ Future 4th Plan in the smart city at the public play space, digilog strategic planning, should be research models that include digital technology and human touch, which are communication tools to strengthen user participation (Figure 3).

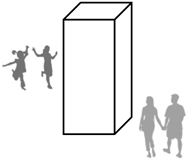

Figure 3.

The ICTs’ future smart city planning presents a digilog strategic plan.

2.3. Case Analysis of Media City and Spatiality of Public Play Space

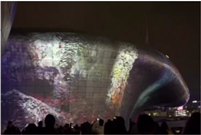

The digilog strategy model for strengthening user participation in public play spaces is based on ICTs’, and media interaction plays an essential role in media content communication connecting users and spatial relationships. In the case of the media façade of Diamond Bridge in Busan, it is an attraction visited by about 1 million tourists during the fireworks festival every year, which is a representative event, and it is a local place valuable city that not only highlights the characteristics of the place, but also actively expresses human activities [8] (Figure 4). Therefore, the characteristic of the urban brand value of local attractions is a community place that elicits empathy for users and a local place with a community network that connects users’ lives [9].

Figure 4.

The appearance of Diamond Bridge before the 1993 construction started and the landscape media facade after the construction started in 2003 at Gwangalli Beach, Busan. (A,B) general life information media color (2019), (C) BTS concert event period (2022), (D) Fireworks Festival (2018), (E) Drone Shows (2022), (F) Natural scenery before the construction of the Diamond Bridge.

When comparing the changes in landscape media signs before construction in 1993 and after 2003, the Diamond Bridge was highlighted as an active tourist attraction from the general landscape facility of Diamond Bridge in 1993 to Diamond Bridge Media in 2003 (Figure 4). Currently, in most coastal and urban landscapes, media facades that provide image information on landscape facilities and building facades have limitations in their visual information delivery methods. This is because they only deliver commercial visual information, not a public space with user participation. Instead of participating in the delivering the experience that users hope to obtain in a public space, they remain in the media space and are exposed to the media environment [5,10] (Figure 4). Therefore, the digilog strategy model should consider participatory media interaction using user devices. It is not simply a physical architectural appearance, but a media public communication space that establishes a relationship between the user and the public space. Media communication that establishes a relationship between the user and the public space should be communicated in the public space with feedback regarding the user’s needs through manipulation and participation (Figure 3 and Figure 5, Table 1). Therefore, for the digital technology and user participation place-oriented digital log strategy model, we intend to derive an interactive media model in a public play space to analyze user behavior with the keywords of open, participation, sharing, and cooperation (Figure 3, Table 1). As the criteria for model derivation, media interaction spatial type, and media-user interaction techniques, case analysis was conducted. As a result, as a type criterion, (A) the subjective intention of the designer or artist is conveyed visually in one direction, and (B) participation is drawn through interaction with the user [11] (Table 1 and Table 2). (A), (B) The two types are divided into (a) screen, (b) façade, and (c) object media technology expression methods according to the physical architecture and object structure. It is the (a) screen, (b) façade, and (c) object media descriptions that are closely related to the surrounding environment of the public play space. The surrounding environment greatly influences media technology expression by light (Table 1 and Table 2). Therefore, it is divided into projection mapping and multi-display (LED) technology as major categories. First of all, depending on the surrounding environment, projection mapping technology, which is mainly expressed indoors, is affected by the brightness of light, so it is effective in a dark room ((a) Screen). On the other hand, multi-display (LED) technology, which is more economical than projection mapping technology, can be applied both indoors and outdoors, but expresses excellent colors in an outdoor environment that is less affected by light intensity ((b) Facade, (c) Object). The user participation method is different regarding (a) screen, (b) façade, (c) object depending on the media description expression (Table 1 and Table 2). How users engage in entertainment in public spaces varies according to (1) the way people behave in the space, (2) the way people interact with the space, and (3) the way they accept the actions of others [12] (Table 1 and Table 2). In addition, the correlation between physical architecture and objects for (A) and (B) and the media technology expression methods (a), (b), and (c) varies according to how the user has occupied area (Table 1 and Table 2). In the future, the design of public play spaces in ICTs’ Future 4th smart city plan should be interactive, using existing public spaces. Therefore, digilog strategic planning should be explored as a solution, based on the results shown in Table 1 showing the criteria for the lack of user participation in the existing digital media public space.

Table 1.

Media interaction space type: (A), (B) Two types of (a) screen, (b) façade, (c) object media technology expression analyzed according to physical architecture and object structure form.

Table 2.

Case study by type of media-interaction space: media case analysis in a user participatory public play space.

In the future, ICTs’ Future 4th Plan is a strategic plan providing opportunities for citizens and spaces to interact in public play spaces in smart cities, taking into consideration:

- The way people act in the space;

- The way people interact with the space;

- The way other people accept the behavior.

A digilog strategic plan for entertainment and something enjoyable with which to interact should be presented.

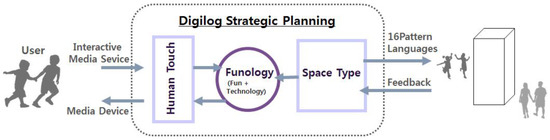

3. The Interaction Model of Media Users in Public Play Spaces

In fact, ICTs’ digital technology is no longer an entity separate from the environment, but it must be studied as an environmental device that integrates with the environment and implements human-centered technology [10]. To design a public entertainment space where various people live; it is crucial to use the interaction of communication so that the content can grow spontaneously in a cyclical manner, rather than as a one-time occurrence. Various users play a role in creating the characteristics of urban space while interacting with public facilities for content providing pleasure and fun in public idle spaces [2]. Therefore, human touch model research should be proposed to make the characteristics of ICTs’ participatory in a media public play space, which should complement human contact, rather than promote disconnection with humans. Therefore, in order to realize this definition of human touch, (1) user-centered movement planning with public play spaces and (2) media touch screens to enhance human communication should be utilized [16] (Figure 5). In order to effectively implement this, media interactive content is a tool for communication with users, and it is necessary to include the user’s five senses and emotions, according to the type of space, in detail. This interactive element of media experience reflects human psychology and should be cyclical. For human touch cyclical self-reliance, media interaction content types include four spatial criteria—interactive, responsive, immersive, and sensory—to satisfy various environmental requirements of public play spaces [2,17]. At this time, since human touch user feedback and participation induction are essential, (1) how people behave in space, (2) how people interact with space, and (3) criteria for accepting other people’s actions according to changes in the user’s five senses can be used to design a detailed plan. Through this, it is possible to determine communication infrastructure elements of user behavioral characteristics for entertainment in public play spaces [12,17]. (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Table 3.

Media experience type classification [2,12,17]—the communication infrastructure element for user behavioral characteristics: (1)–(3).

Table 3.

Media experience type classification [2,12,17]—the communication infrastructure element for user behavioral characteristics: (1)–(3).

| Space and Media Type | Element | Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Interactive | Sensation, Action | Media users and communities |

| Responsive | Cognition, Behavior | It provides surprising effects to the user and reacts to the user’s bodily actions. |

| Immersive | Emotions, Relationships | Interactions with content and information provision |

| Sensory | Sensation, Emotion | Inducing emotional changes that stimulate the five senses |

Figure 5.

ICTs’ participatory media user interaction model included in Table 3.

Figure 6.

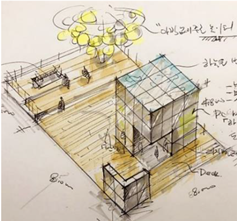

This example plan shows the ICTs’ Future 4th Plan public play space, splace-oriented strategy through a project model.

In parallel, these communication infrastructure elements related to user behavior characteristics will provide new media services to the digilog strategic planning of the public play space. In other words, the interactive human touch service can be proposed as an ICTs’ user-participating media interaction model, providing new entertainment (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

4. Proposal of Application of Media User Interaction Model in Public Play Space

4.1. Propose a Digilog Strategic Plan for Public Play Space

This is a practical model study regarding project planning and production of ICTs’ digital convergence media contents that strengthens communication between cities and humans by combining digital technology and human touch (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Based on the user’s behavior analysis, human touch services were derived, and facilities and systems were designed and contents developed for this purpose. Moreover, it establishes a communication method for new digital convergence media content between users and computer systems. In other words, it is proposed that the user interface can be manipulated through dialogue, reaction, and sensory experience in a natural and intuitive form (Table 3, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Therefore, as a participatory, interactive media medium in ICTs future-type public play space, we propose a digilog strategy sample plan for the purpose of proposing ICTs’ Future 4th Plan public play space, using a place-oriented strategy in for the smart city.

4.2. Space Analysis of the Proposed Project in Three Pattern Languages

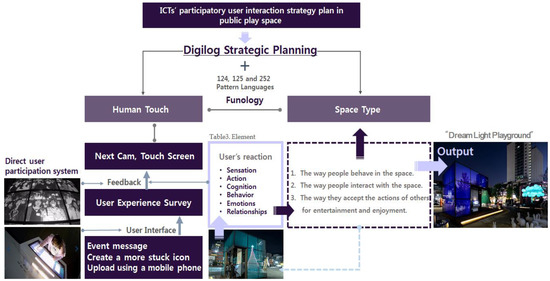

Of the 16 pattern languages, 3 pattern languages were derived—124. Activity Pockets, 125. Stair Seats, and 252. Pools of Light—and spatial planning was based on user behavior analysis, as shown in Figure 5.

- (1)

- The way people behave in the space;

- (2)

- The way people interact with the space;

- (3)

- The way they accept the actions of others for entertainment and enjoyment.

Spatial proposal analysis was performed as a reference (Table 4). Thus, in order to analyze the relationship between the new communication places where users participate in the “dream light playground” actually produced, 3 pattern languages and (1)–(3). Furthermore, it was intended to analyze and propose correlations through user behavior analysis. Moreover, we analyzed and proposed the possible range of space types as a participatory, interactive media medium for interactive human touch relationships to strengthen communication between the city and humans (Table 4).

Table 4.

Media experience type classification: Select 3 pattern languages from 16 pattern languages and compare and analyze them with the actual project site.

Using a pattern language, Alexander planned which architectural elements would be required to make people happy [6]. Similarly, it was the planning intention of “a space where everyone can share” in the context of the environmental approach regarding the public space of the urban playground. Alexander’s interaction architecture design pattern language is not significantly different in the social context of the researcher’s environmental approach to urban regeneration space (Table 4).

4.3. Case Analysis of Media City and Spatiality of Public Play Space

There have been several ways in which participatory media has allowed people to create, connect, and share their content or build friendships through media [20] (Table 4). Suggesting that the user experience media interaction in the public space environment was of vital importance. It was our intent to participate in various means of communication through the interaction between dialogue and action through media devices. Thus, there are two 1. Dream Light Tree, and 2. Dream Light Cube objects in the actual manufactured Dream Playground that actually produced this proposal (Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

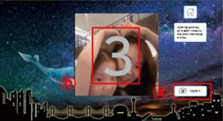

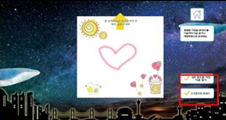

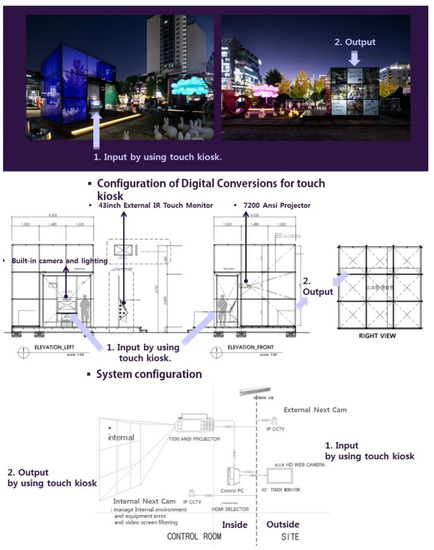

Figure 7.

User engagement media-interaction plans for the “Dream Light Cube,” project [17], Adapted from Lee, Byungyoung, Lee, Jonghyuk (2019 of Publication): 1. With media interaction technology, users input photos or messages on the kiosk touch screen. The touch kiosk screen is a smartphone application concept system that anyone can use. 2. The content entered by the user is linked to one screen out of nine screens by a beam projector, and media is transmitted in a time-difference rotation on the large screen. Reprinted from Choi, Kyubok (2019 of Publication).

In the case of the produced “Dream Light Cube,” this project consists of a system that can be viewed on a large external screen by entering a picture or message you want to show on the kiosk screen. A total of nine different contents are projected (Figure 7: 2. Output by using touch kiosk). It is a user-participation media interaction and consists of two types of (1) icon type and painting and (2) event type programs (Table 5).

Table 5.

User engagement media-interaction for the “Dream Light Cube”, project: Touch Kiosk 2; type programs: (1) icon type and painting and (2) event type. Adapted from Lee, Jonghyuk (2019 of Publication).

This large screen embodies the cultural method of young people who communicate through novel networks and screens using media interaction technology (Table 3 and Table 5, Figure 5 and Figure 6). (1) and (2) through the kiosk, users can take a picture or send it by handwriting directly on the screen. The operation method is the same system as the concept of a smartphone’s touch application (Figure 7: 1. Input by using touch kiosk). This system concept is a media communication tool, and the kiosk induces natural user recognition. The easily recognized UI scheme is designed so anyone can efficiently operate it. Most media interaction technologies do not transmit information through projection mapping and multi-display (LED) synchronization, but have adopted a method of transmitting content in conjunction with a beam projector. (Table 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7: 2. Output by using touch kiosk).

In particular, through the interactive touch screen kiosk, the user’s participation was induced with a system that allows users to display drawings or characters as desired by hand, or to use various icons and drawing filters to recognize human faces (Table 5, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). In addition, icons directly drawn by citizens for icon emoticon design are provided at the kiosk, and a system that induces citizen participation through regular updates is planned (Table 5). The screen installed in the facility’s structure is designed to provide a variety of interactive experiences so that it can provide leisure activities for families, acquaintances, and friends through (2) event type the interactive service of the user output that is displayed in real-time in the form of an LED signboard (Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

5. Conclusions

In this study, the necessity of a public play space in the Future 4th Plan for the smart city is assessed. In evaluating the role of information transmission viewed only by the media in that space, we propose that it is the necessity to realize an interactive medium of mutual relationship that facilitate communication between the public play space and the user. Our purpose is to propose a guideline model for the use of media in public play spaces based on social action participation. The use of devices and services in this space and maintaining the urban environment of the continuous public play space should also be considered. Therefore, we proposed a digilog strategy sample plan to research the Future 4th Plan, a place-centered strategy proposal for public idle space within a smart city that requires the consideration of contents that reflect all environmental aspects of a public play space. The overall results show that as a strategic plan for ICTs participatory media user interaction in a public play space should be evaluated regarding 1. how people behave in the space, 2. how people interact with the space, and 3. how people accept the behavior of others. Thus, it is essential to choose the optimal location for the kiosk. This is because the space should catch the eye at a glance and anticipate the users’ natural flow of movement. The most effective method is the proper use of a combination of signs and sign systems. In addition, imprinting that the kiosk and the main object are “connected” can increase the accessibility of public users. Despite the advantages and disadvantages of individual materials, it is proposed that, in this project design study based on Alexander Christopher’s theoretical background, the study’s strength comes from media installations, which played a vital role in recognizing user accessibility to the surrounding environment and allowing various users to enjoy and communicate in a cultural play space. However, the disadvantage of the research project was that it was necessary to secure sufficient space and kiosk installation in case many people used it simultaneously. In particular, LED equipment was expensive; thus, the beam project equipment was used instead to express the LED effect in a sculptural form. It is true that when analyzing users through Next Cam and field observation from 2019 to the present, the two limitations of this proposed project are: 1. in many cases, groups often use kiosks in public places together, such as in families. In order to supplement this, research on ICTs’ digital convergence among users from various fields needs to be studied; 2. through a user feedback survey regarding media touch screen use, the guideline criteria should be established as a study of the digilog strategy; and 3. there is a need for research to replace the multi-LED technology that can employ a touch screen which is not affected by reflections from ambient light, and can thus be used even during the day. It is reasonable that LED equipment is much more expensive than beam project equipment in terms of cost; most media exhibitions are used in indoor spaces which are not affected by the light of nearby places or objects. This study can contribute to a need for research on outdoor media technology that can be distributed in various public play spaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and S.L.; methodology, D.L.; formal analysis, D.L.; investigation, D.L. and S.L.; data curation, D.L. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, D.L.; supervision, S.L.; funding acquisition, D.L. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the publishd version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) with a grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF-2020R1A2C4002026). This research was also funded by the Busan Architecture Festival Organizing Committee, grant number 2019, and the Busan Metropolitan City Office of Education. The HUG-Korea Housing and Urban Guarantee Corporation was funded by 263 million won, which was awarded for this project. (Urban Playground Project) (BAF B.N.; 607-82-10251).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this analysis are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICTs | Information Communication Technologies |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| Digilog | A combination of digital and analog |

References

- Social PR Team. ‘Human Touch’ (Feat. LG ThinQ) to Add Warmth in the Untact Era. LIVE LG; LG Electronics Social Magazine. 2021. Available online: https://live.lge.co.kr/human_touch_technology/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Lee, S.-H.; Im, Y.-T.; Ahn, S.-Y. Smart City: Ebook, 2nd ed.; CommunicationBooks: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022; pp. 10–43. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.K.; Cho, Y.K.; Kang, H.W. A Study on Interelation between Street Furniture and Christoper Alexander’s Pattern Language as the vitalization factor of Commercial Street. Archit. Inst. Korea 2010, 26, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A Pattern Language-Towns Building Construction; Oxford University Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1977; pp. 3–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.; Kemp, M. Interactive Architecture, Spacetime Korean Editon; Princeton Architectural Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea; New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 103–224. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, C.; Robert, R.; David, C.; Christopher, N. About Face: The Essence of Interaction Design, Acorn Publishing House, 4th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2014; pp. 31–428. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-ie/About+Face%3A+The+Essentials+of+Interaction+Design%2C+4th+Edition-p-9781118766583 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- 3rd Smart City Comprehensive Plan: 2019–2023; The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020; pp. 27–71.

- Gwangalli Beach, Busan. Available online: https://www.dbeway.co.kr/kor/CMS/TravelPoint/viewb.do?mCode=MN173&idx=103 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Kim, N.-D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jeon, M.-J.; Lee, H.-E.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Alex Suh, Y.-H.; Kwon, J.-Y.; Han, D.-H. 2021 Consumer Trend Korea Insights, 2nd ed.; Mirabook Publishing Co.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021; Volume 11, pp. 251–275. Available online: http://www.miraebook.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=m02_01&wr_id=396&sca=%EA%B2%BD%EC%A0%9C%EA%B2%BD%EC%98%81&sfl=wr_1&stx=%EA%B9%80%EB%82%9C%EB%8F%84&sop=and&page=1 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Chae, J.-W.; Cha, S.-H.; Kwon, Y.-G. The Language of Spatial Design, 1st ed.; Nalmadabooks: Souel, Republic of Korea, 2011; pp. 87–372. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, Y.-S.; Chae, J.-W. Extension of the Concept of Urban Ecology by Interactive Media. J. Korea Inst. Spat. Des. 2018, 13, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, K.-S. A Study on the Media Expression Method to Urban Street Landscape. J. Integr. Des. Res. 2011, 10, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immersive Art Exhibition of Bunker Des Lumieres. Bunker History. Available online: https://www.deslumieres.co.kr/bunker (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Jeon, S.-I. ‘Crown Fountain’ Represents Chicago Public Art: The Science Times. 2021. Available online: https://www.sciencetimes.co.kr/news/%EC%8B%9C%EC%B9%B4%EA%B3%A0-%EA%B3%B5%EA%B3%B5%EB%AF%B8%EC%88%A0%EC%9D%84-%EB%8C%80%ED%91%9C%ED%95%98%EB%8A%94-%ED%81%AC%EB%9D%BC%EC%9A%B4-%EB%B6%84%EC%88%98/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Media Art of the Architectural Exterior. Available online: https://hub.zum.com/aliceon/5640 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Kim, N.-D.; Jeon, M.-J.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, H.-E.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Alex Suh, Y.-H.; Kwon, J.-Y.; Han, D.-H.; Lee, H.-W. Trend Korea 2022; Mirabook Publishing, Co.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022; Volume 12, pp. 51–52. Available online: http://www.miraebook.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=m02_01&sca=%EA%B2%BD%EC%A0%9C%EA%B2%BD%EC%98%81&sfl=wr_1&stx=%EA%B9%80%EB%82%9C%EB%8F%84&sop=and&page=2&page=1 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Lee, D.-H.; Lee, B.-Y.; Lee, J.-H. Dream Light Playground of Concept Presentation Material; Busan Architecture Festival Organizing Committee: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Busan Metropolitan City Office. Of Education Drawing provided by Busan Metropolitan City Office of Education; Busan Metropolitan City Office: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Urban Playground Project. Available online: http://www.biacf.org/?d=show&f=playgd (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Participatory Culture. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Participatory_culture (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).