Abstract

In order to solve the problem of passenger risk classification, an assessment model for air passenger risk classification based on the analytic hierarchy process and improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is constructed. The existing index systems are improved by the comprehensive method. The index system of passenger risk assessment is established, which includes 23 indexes from five aspects: basic background, personal status, economic situation, personal conduct and civil aviation travel. In addition, the weight of each index is determined by the analytic hierarchy process. An improved method of determining fuzzy relation matrixes is proposed. The single factor evaluation vectors of discrete indexes can be determined according to the results of probability statistics, and the single factor evaluation vectors of continuous indexes are calculated by fitting function. Then the assessment model for passenger risk classification based on the improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is established. According to the characteristic analysis of civil aviation passengers and terrorists, typical passenger samples of high, medium and low risk are set to verify the model. The results show that the evaluation results of typical passenger samples are consistent with the basic assumptions. The model is suitable for risk classification assessment of air passengers. Moreover, the tedious evaluation process is reduced compared with the traditional fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method.

1. Introduction

With the steady development of the social economy, the deepening reform of the civil aviation management system and the upgrading of the residents’ consumption structure, the civil aviation industry has developed rapidly. However, the traditional security check mode is strict and cumbersome, and the contradiction between the increasing passenger throughput and the limited security check resources reduces the security check efficiency and passenger satisfaction. Moreover, with the development of society, the factors affecting civil aviation security have become more complex and diverse, which makes airport security checks face great challenges and pressure. Therefore, the optimization of airport security check mode is extremely important for improving security check efficiency, rationally allocating security check resources, and improving passenger satisfaction.

To improve the current situation of airport security checks, the classified security check mode is proposed, which has been studied by many scholars. Some scholars mainly focus on the design of models for classified security check systems. McLay et al. modeled the classified security check problems under three, five and eight passenger risk levels and used a heuristic algorithm based on the greedy strategy to solve them. The marginal costs, fixed costs and security levels under three, five and eight passenger risk levels were analyzed and compared. The experimental results showed that classified security checks with fewer passenger risk levels might be more effective [1]. Babu et al., established a model to determine the number of passenger groups and the resource allocation for each group under the condition that the threat probability of all passengers is constant. The influence of the false alarm rate and the threat probability on the model was studied, concluding that the grouping strategy is related to the threat probability [2]. Different from the study by Babu et al., Nie et al. relaxed the basic assumption that the threat probability of all passengers is constant and considered the risk levels of passengers. A mixed integer linear model with the minimum false alarm rate as the objective function was built to determine the grouping strategy of passengers and the staffing of each security channel. Compared with the model established by Babu et al., the model considering passenger risk attributes makes the airport security system more effective [3]. Majeske et al., established the Bayesian decision model of the air passenger prescreening system, which divided passengers into two categories: fly passengers and no-fly passengers, and used cost parameters from the perspective of the government and passengers to evaluate classified security checks [4]. Nie et al. simulated the queuing of classified security check channels to effectively utilize resources in airport security. According to the number of passengers in the classified security channels, passengers with different risk levels are allocated to different security channels [5]. Huang et al., proposed an airport classified security check system that divided passengers into three categories according to historical security records. The two-dimensional Markov process and the Markov modulated Poisson process queue were used to build the model of the security system, and the simulated annealing method was used to solve the model. The effectiveness of the proposed classified security check system in improving service efficiency and security level was verified by examples [6]. Song et al. described an N-stage passenger screening model and analyzed it by using game theory and queuing theory. In this model, passengers have the chance to be passed or rejected at each stage. The functional relationships between application probabilities, screening probabilities, approver’s benefits and the number of screening stages were also analyzed. In addition, some suggestions on the security check strategies and the optimal number of screening stages were given [7]. Zheng et al., proposed an air passenger profiling model based on fuzzy deep learning to classify high-risk and low-risk passengers [8]. However, such models based on the neural network lack the interpretability of passenger classification and need to use a large amount of data for training. Wang et al. established and optimized the airport security check system model based on passenger risk classification. Moreover, scientific analysis and calculation of the dynamic allocation of security facility resources were carried out [9]. Song et al., modeled and analyzed the imperfect parallel queuing security inspection system in Precheck. The model was extended by considering the different distributions of passenger parameters and the risk levels of passengers. In addition, the optimal screening strategy was studied by combining game theory and queuing theory [10]. Albert et al. reviewed various kinds of literature about risk-based security checks and compared different modeling methods in the literature. Then the mathematical model of passenger screening in PreCheck was established, and the dynamic programming algorithm was used to solve it to determine the optimal strategy of dividing passengers into different risk levels. Numerical experiments showed that risk-based security check models could improve security [11]. Wang et al. studied and analyzed a limited-capacity security queuing system based on passenger risk classification and proposed a method to calculate the steady-state probability and performance indexes of the queuing system. By analyzing the relationship between the model parameters and the system performance, some guiding suggestions were provided for airport security checks under the COVID-19 epidemic [12]. Moreover, some scholars have studied the effectiveness and acceptability of classified security checks. Cavusoqlu et al. analyzed the influence of civil aviation passenger profiling on aviation security and proved that the effect of classified security checks is better than that of the traditional mode when there is a sufficiently reliable passenger screening system [13]. Subsequently, Cavusoglu et al. analyzed and compared the passenger security checks with and without the profiler in the presence of attackers, and concluded that the failure of the profiler could be overcome by adjusting the profiler and the parameters of security check equipment [14]. Bagchi et al., further verified the effectiveness of classified security check systems such as PreCheck, which allow low-risk passengers to undergo quick security checks and mitigate the adverse effects of budget shortfalls to a certain extent [15]. Stewart et al. used cost-effectiveness and risk-analytic methods to evaluate the classified security check system of American airports, concluding that it can improve the efficiency of security checks and is good for passengers, airports and airlines [16]. Wong et al., analyzed the advantages and obstacles of risk-based passenger screening and believed that the application of the classified security check system needed coordination among regulators, airports, airlines and passengers [17]. Stotz et al., studied the acceptability of classified security checks based on passenger risk as an alternative to existing security screening procedures, and concluded that people’s perception was the main driving factor [18].

Since classified security checks help to improve the quality of security check services, some airports have gradually begun to apply this security check mode. The classified security check mode adopted by Israeli airports is called behavior pattern analysis. Airport staff will call passengers three days before their departure to ask for basic information to analyze their behavior. Then, after passengers arrive at the airport, the security inspectors will inquire them and observe whether there is anything unusual in their manners, reactions and answers, and classify them accordingly [19]. Some European airports use Smart Security, a security check system that divides passengers into three categories based on their risk levels, and then allocates designated lanes [19]. In 2011, American airports started to use PreCheck, which is designed to quickly check low-risk passengers [20]. Shenzhen Airport officially implemented a new strategy of classified security checks for its domestic flight passengers in December 2018. Frequent fliers with good security credit can enter the fast lane for security checks, who are selected based on the collected information.

Although the research on the classified security check mode has achieved certain results and the classified security check mode has been widely used in the practice of airports, most of the research mainly demonstrates the effectiveness of classified security checks and seldom explains specific methods of passenger classification. Moreover, index systems of passenger risk assessment established in the existing research include many indexes, which may easily lead to the curse of dimensionality and affect the efficiency of evaluation. Moreover, the setting of indexes is not accurate enough, and there is a lack of evaluation indexes that positively reflect the risk of passengers. Therefore, this paper rearranges all levels of indexes, eliminates redundant indexes, merges similar indexes, and adjusts and increases indexes on the basis of the existing index systems and personal credit evaluation index systems to establish a more reasonable index system of passenger risk assessment. In addition, then an assessment model for air passenger risk classification is built by the analytic hierarchy process and improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method.

2. Assessment Model for Air Passenger Risk Classification

2.1. Index System of Passenger Risk Assessment

The index system of passenger risk assessment is the foundation of assessing passengers’ risk. There are many methods to construct the assessment index system, such as Delphi method, analysis method, cross method, comprehensive method and grouping method of index attribute. Although some scholars have carried out relevant research, there is no uniform standard for the establishment of passenger risk assessment index systems. Moreover, there are some problems in the existing research. For example, the established index systems are too huge. In addition, the correlation of some indexes is high. Passenger risk assessment mainly analyzes the risks that passengers have that endanger aviation safety. It is similar to the credit risk assessment of individuals by financial institutions such as banks. In addition, the personal credit assessment system is relatively mature. Therefore, this paper uses the comprehensive method to scientifically and systematically analyze the passenger risk assessment index systems in [21,22], and the current personal credit assessment index systems, and make further improvements.

The index system of passenger risk assessment established in [21] includes 5 first-level indexes and 47 second-level indexes of natural condition, occupation, economic situation, credit standing and flight situation. The index system of passenger risk assessment established in [22] includes 4 first-level indexes and 30 second-level indexes of basic situation, economic situation, public records and flight information. The above indexes are classified and sorted, and the basic background, personal status, economic situation, personal conduct and civil aviation travel record are selected as the first-level indexes, in which the basic background is the inherent attribute of passengers, the personal status is an important index to evaluate the stability of passengers, the economic situation is an index that indicates the economic level of passengers, the personal conduct is an index that describes the behavior and morality of passengers, and the civil aviation travel record reflects the situation of passengers’ civil aviation travel. According to the second-level indexes of natural condition, occupation situation in [21] and basic situation and economic situation in [22], gender, age, nationality and education are selected to describe the basic background information of passengers. In addition, occupation, place of residence, religious belief, marital status and state of health are selected to reflect the personal stability of passengers. The index of occupation is used to replace the relevant indexes such as industry, occupation, and professional title, which reduces the number of indexes while ensuring the comprehensiveness of the evaluation. Based on the personal credit evaluation system, redundant indexes such as family structure and dependent population are excluded, and the index of marital status is used to describe the marital and family situation of passengers. In terms of the economic situation, there are some indexes in [22] that are not suitable for describing the economic situation, such as family structure and supporting population. Therefore, following the principle of independence, the index of total assets is used to replace deposit, housing and other indexes of movable and immovable property on the basis of [21] to ensure the accuracy of the evaluation results. Moreover, the indexes of annual income, debt and insurance amount are retained. When selecting the indexes to evaluate passengers’ conduct based on the credit indexes in [21] and the public record indexes in [22], records of civil judgment, records of administrative penalty, records of criminal punishment and other similar indexes are combined into the index of criminal records. In addition, overdue records and tax arrears are classified as default to avoid excessive indexes affecting the efficiency of evaluation. According to the evaluation objectives, records of uncivilized civil aviation travel are further refined into bad records of security checks, and the index of awards is added to evaluate passengers from a positive perspective. In terms of civil aviation travel records, the annual number of flights, flight information, time of buying tickets and other indexes used to reflect the flight situation in the [21] are retained, and the index of frequent flyer program membership related to the annual number of flights is excluded. In addition, the index of aviation insurance is expressed in detail as the index of aviation insurance amount to ensure the measurability of the evaluation indexes. Passengers with too high or too low insurance amounts are considered to have greater risks. The index system of passenger risk assessment is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Index system of passenger risk assessment.

The information of passengers can be obtained through the public security information system, hospitals, banks, department of motor vehicles, real estate board, industrial and commercial bureau, national credit system and civil aviation information system. For data that are difficult to obtain or missing, the average, median and mode can be used to fill in.

2.2. Weights of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes

The analytic hierarchy process is used to calculate the weights of indexes in the index system of passenger risk assessment, in which the 1–9 scale method is used to compare the indexes at the same level in pairs. Meanwhile, 10 experts in the field of aviation security are consulted in the form of a questionnaire. The questionnaire is attached as Appendix A. In addition, the evaluation results of each expert are averaged to obtain each judgment matrix. Then, the weights and the greatest eigenvalues are calculated according to the judgment matrices, and the consistency check is carried out.

Table 2.

Judgment matrix of −.

Table 3.

Judgment matrix of −.

Table 4.

Judgment matrix of −.

Table 5.

Judgment matrix of −.

Table 6.

Judgment matrix of −.

Table 7.

Judgment matrix of − .

The weight vector of the judgment matrix can be calculated by Equation (1), where is the weight of the index , is the element in row and column of the judgment matrix, and is the order of the judgment matrix.

The greatest eigenvalue of the judgment matrix can be calculated by Equation (2), where is the greatest eigenvalue, is the order of the judgment matrix, and is the i’th component of .

The consistency index can be calculated by Equation (3), where is the consistency index.

Then, the numerical value of the random consistency index is obtained according to the order of the judgment matrix, and the consistency ratio can be calculated by Equation (4), where is the consistency ratio, is the consistency index, and is the random consistency index. If the consistency ratio is less than 0.1, it indicates that the judgment matrix has consistency.

The weights of indexes are calculated by MATLAB, and the weights of indexes at all levels are finally obtained as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Weights of passenger risk assessment indexes.

2.3. Improved Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method

According to the traditional fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method, it is necessary to evaluate each index of each passenger one by one to establish the fuzzy relation matrix, which is a cumbersome process. Therefore, it is considered to improve the method of determining fuzzy relation matrixes to adapt to the risk classification assessment of a large number of passengers.

2.3.1. Determination of Factor Set

The evaluation factor set is the set of factors that affect the evaluation object, which is represented by . According to the established index system of passenger risk assessment, is divided into two levels. The first level is . The second level is , , , , .

2.3.2. Determination of Evaluation Set

Referring to the existing classified security check mode and the classification of passenger risk in related research, the evaluation set of this model is set as .

2.3.3. Determination of Weight Set

It can be seen from Table 8 that the weight set of the first level is , and the weight sets of the second level are , , , , .

2.3.4. Improved Fuzzy Relation Matrixes

The fuzzy relation matrix is a mapping from the factor set to the evaluation set, and is composed of the single factor evaluation vector (), where represents the degree of membership of factor belonging to grade , . The degree of membership function can be calculated by Equation (5), where is the number of experts who judge that factor belongs to grade , and T is the number of experts participating in the evaluation.

A questionnaire is used to determine the evaluation results of 10 aviation security experts on the attribute values of some indexes, which is shown in Appendix B. The data obtained from the questionnaire are shown in Appendix C. According to the evaluation results, the standard of single factor evaluation is established for each index, and different methods are adopted to evaluate different kinds of indexes.

(1) The single factor evaluation vector () of the index whose nature is a discrete variable can be formulated according to the statistical results of expert evaluation. The degree of membership is determined by Equation (5). Then, the single factor evaluation vector of index can be calculated by Equation (6):

Taking the index of gender as an example, it can be seen from the statistical results that the single factor evaluation vector of men belonging to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk is [0.4, 0.3, 0.3], and that of women belonging to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk is [0.2, 0.3, 0.5].

(2) The single factor evaluation vector () of the index whose nature is a continuous variable can be determined after obtaining the fitting function of the degree of membership through statistical data. First, the functions () corresponding to the first are obtained by fitting. In addition, then the fitting function of can be calculated by Equation (7), where is the attribute value of the index , and is the number of comments.

When , () is calculated, then , the single factor evaluation vector of the index can be calculated by Equation (8):

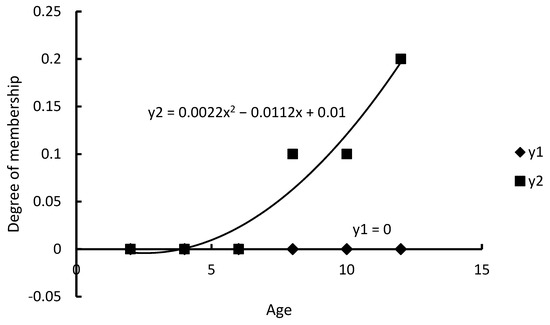

Taking the index of age as an example, this continuous variable is divided into six intervals: under 14 years old, 14–18 years old, 19–30 years old, 31–50 years old, 51–60 years old and over 60 years old. Then, the data collected in these six intervals are fitted, respectively, to obtain the single factor evaluation of different age intervals. In the interval of under 14 years old, the single factor evaluation vector is r1 = [r11, r12, r13], where r11, r12 and r13 are the degrees of belonging to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk, respectively, and r11 + r12 + r13 = 1. Let y1, y2, and y3 be the fitting functions corresponding to r11, r12, and r13. According to the existing statistical data, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 1, where y1 = 0, y2 = 0.0022x2 − 0.0112x + 0.01. Then, y3 = −0.0022x2 + 0.0112x + 0.99 can be calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 1.

Single factor evaluation for under 14 years old.

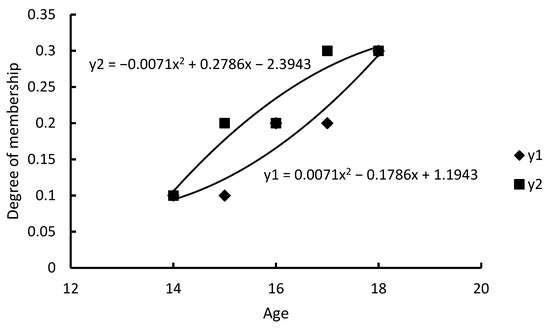

Similarly, in the interval of 14–18 years old, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 2, where y1 = 0.0071x2 − 0.1786x + 1.1943, y2 = − 0.0071x2 + 0.2786x − 2.3943. Then y3 = −0.1x + 2.2 is calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 2.

Single factor evaluation for 14–18 years old.

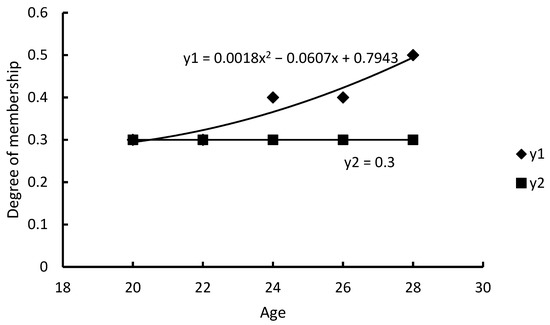

In the interval of 19–30 years old, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 3, where y1 = 0.0018x2 − 0.0607x + 0.7943, y2 = 0.3. Then y3 = −0.0018x2 + 0.0607x − 0.0943 is calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 3.

Single factor evaluation for 19–30 years old.

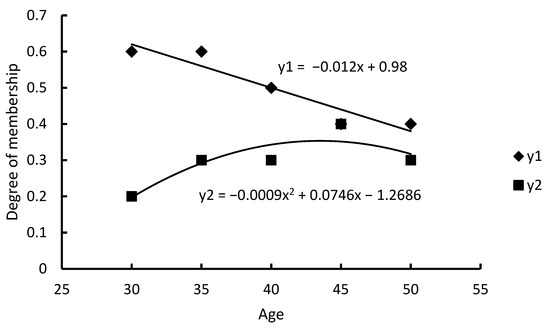

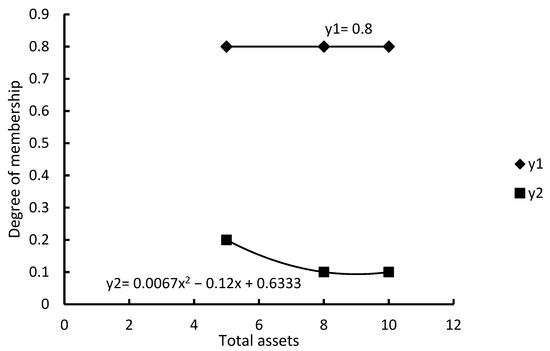

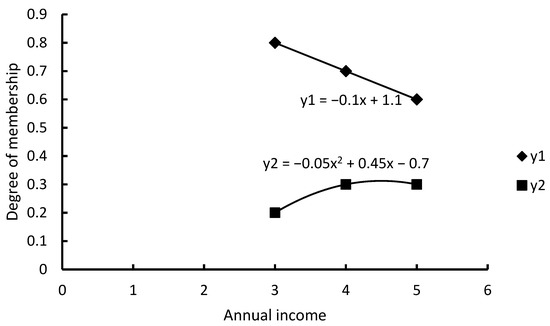

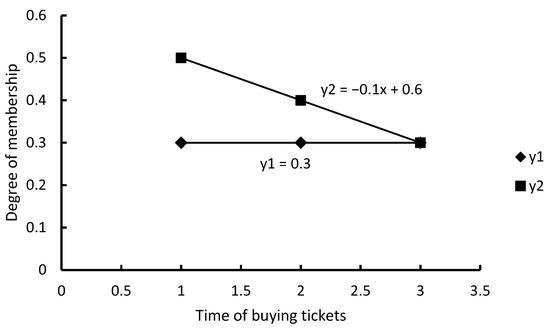

In the interval of 31–50 years old, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 4, where y1 = −0.012x + 0.98, y2 = −0.0009x2 + 0.0746x − 1.2686. Then y3 = 0.0009x2 − 0.0626x + 1.2886 is calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 4.

Single factor evaluation for 31–50 years old.

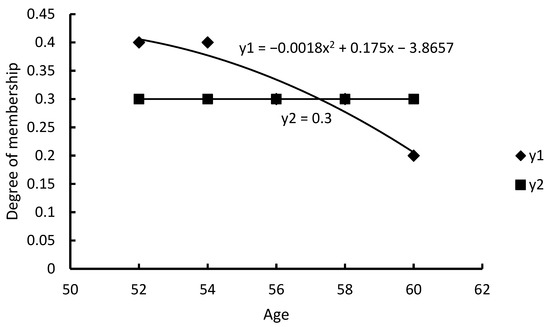

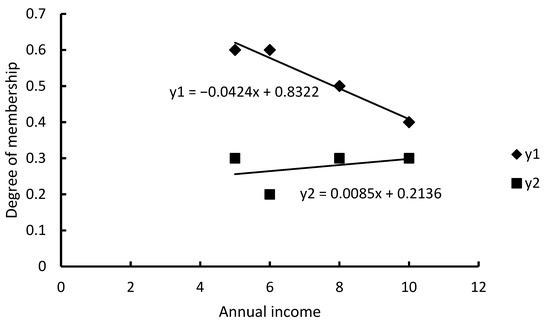

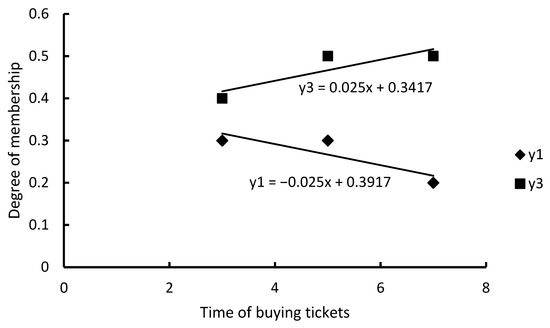

In the interval of 51–60 years old, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 5, where y1 = −0.0018x2 + 0.175x − 3.8657, y2 = 0.3. Then y3 = 0.0018x2 − 0.175x + 4.5657 is calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 5.

Single factor evaluation for 51–60 years old.

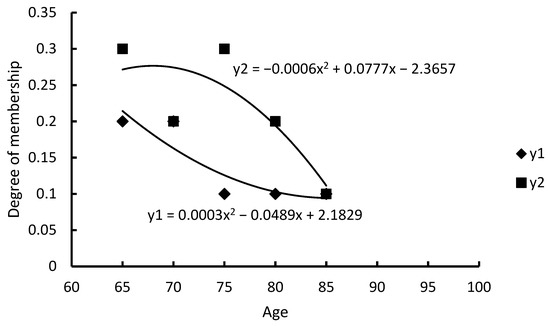

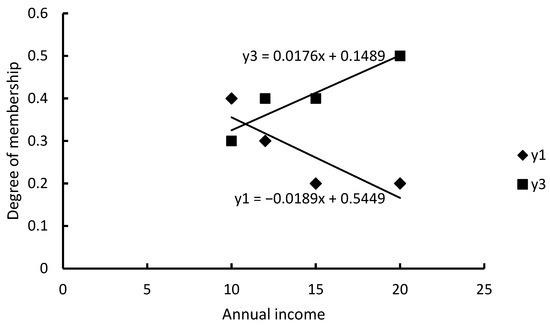

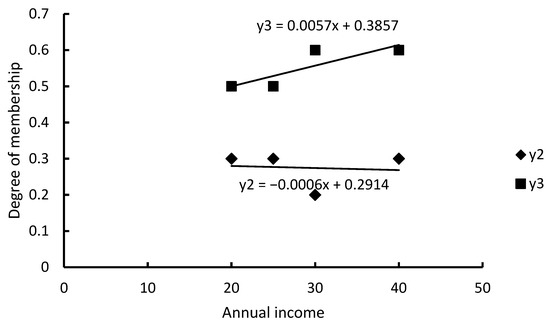

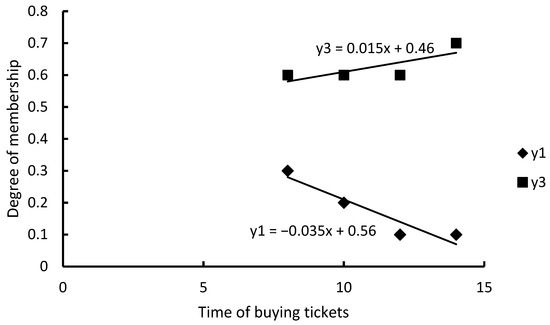

In the interval of over 60 years old, the fitting results of y1 and y2 are shown in Figure 6, where y1 = 0.0003x2 − 0.0489x + 2.1829, y2 = −0.0006x2 + 0.0777x − 2.3657. Then y3 = 0.0003x2 − 0.0288x + 1.182 is calculated by Equation (7).

Figure 6.

Single factor evaluation for over 60 years old.

The single factor evaluation vectors of other second-level indexes can be determined by the same method. Figures of the fitting functions corresponding to the single factor evaluation vectors of the other continuous second-level indexes except age are included in Appendix C. The results are shown in Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13, in which the amount of aviation insurance is divided according to 200,000 yuan each, the time of buying tickets is in days, and 12 h before departure is counted as 0.5 days. Then, the fuzzy relation matrix of the first-level indexes is established. In the actual calculation, each element in the single factor evaluation vector can be in [0, 1] by rounding, and the sum is 1.

Table 9.

Single factor evaluation of basic background indexes.

Table 10.

Single factor evaluation of personal status indexes.

Table 11.

Single factor evaluation of economic situation indexes.

Table 12.

Single factor evaluation of personal conduct indexes.

Table 13.

Single factor evaluation of civil aviation travel record indexes.

2.3.5. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model has two levels and adopts a linear weighted average operator. The first-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model is given by Equation (9), where is the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of the i’th first-level index, is the weight set of the i’th first-level index and is the fuzzy relation matrix of the i’th first-level index.

The second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model takes the results of the first-level evaluation as the single factor evaluation of the second-level model to make the final comprehensive evaluation. The second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model is given by Equation (10), where is the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation, is the weight set, is the second-level fuzzy relation matrix, and is the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of the i’th first-level index.

Finally, the results are evaluated and analyzed according to the maximum membership principle.

3. Case Study

3.1. Overview of Examples

Due to the lack of specific sample data, we referred to the relevant research on the characteristics of Chinese civil aviation passengers and obtained the following conclusions. The proportion of male passengers is generally higher than that of female passengers. In terms of age composition, the age interval of 24–50 has the largest number of passengers. Most of the passengers who choose to travel by plane have higher educational levels, and the proportion of passengers with low education levels has increased. By analyzing the professional characteristics of civil aviation passengers, it can be found that the scope of industries involved is very wide, but a large proportion of passengers are those who work in private enterprises, state-owned enterprises, foreign-funded enterprises, administrative organs and institutions. The passengers are mainly middle-and high-income groups, and the proportion of low-income passengers has increased. The annual number of flights of most passengers is concentrated in 1–9 times. In terms of the purchase time, the number of passengers who purchased tickets within three days before departure is the largest. With the change in payment methods, online payment has gradually replaced the traditional way of cash payment. Moreover, we referred to the relevant research on terrorists and found that among terrorists, 97.4% are men and 2.6% are women. Moreover, the average age of terrorists is about 23 years old. Then, according to the occupation, nationality, age, criminal record, cash payment, high insurance amounts, large debt, physical illness, religious belief and other characteristics of high-risk passengers in the attempted bombing in the United States in 2001, Dalian Air crash on 7 July 2002, the attempted hijacking of Air China flight CA1505 in 2003, and the attempted hijacking of Tianjin Airlines flight GS7554 in 2012, as well as the above-mentioned characteristics of general civil aviation passengers and terrorists, the sample data of high-risk passengers A, B and C, medium-risk passengers D and E, and low-risk passengers F, G and H are set, as shown in Table 14, Table 15, Table 16, Table 17 and Table 18.

Table 14.

Sample data of passengers (basic background indexes).

Table 15.

Sample data of passengers (personal status indexes).

Table 16.

Sample data of passengers (economic situation indexes).

Table 17.

Sample data of passengers (personal conduct indexes).

Table 18.

Sample data of passengers (civil aviation travel record indexes).

3.2. Analysis of Examples

3.2.1. Determination of Fuzzy Relation Matrixes

According to the method of determining fuzzy relationship matrixes in Section 2.3.4, the single factor evaluation vectors of discrete second-level indexes can be determined by expert evaluation results and Equation (6), and the single factor evaluation vectors of continuous second-level indexes can be determined by substituting the attribute values of indexes in the fitting function of the degree of membership in Equation (8). Then, the fuzzy relationship matrixes of the first-level indexes of the eight passengers in Table 14, Table 15, Table 16, Table 17 and Table 18 are calculated, and each element of the matrixes keep one decimal place.

Taking passenger A as an example, the relation matrix R1 of basic background indexes, the relation matrix R2 of personal status indexes, the relation matrix R3 of economic situation indexes, the relationship matrix R4 of personal conduct indexes, and the relationship matrix R5 of civil aviation travel record indexes are, respectively:

3.2.2. First-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

According to Equation (9) and the relevant data, the first-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger A is made: , , , and .

3.2.3. Second-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

It can be seen from Equation (10) that the relation matrix of the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model is , so the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger A is .

Similarly, by using MATLAB to calculate the remaining sample data, it can be obtained that the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger B is , the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger C is , the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger D is , the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger E is , the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger F is , the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger G is , and the second-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of passenger H is .

3.3. Results Analysis

According to the final calculation results of the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation, it can be found that passenger A’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 54.55%, 34.64% and 10.81%, respectively. Based on the maximum membership principle, it can be judged that passenger A is a high-risk passenger. Similarly, passenger B’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 54.98%, 30.76% and 14.26%, respectively. Therefore, passenger B is also a high-risk passenger. Passenger C’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 52.29%, 29.08% and 18.63%, respectively, so passenger C is a high-risk passenger. Passenger D’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 29.94%, 38.23% and 31.83%, respectively, so passenger D is a medium-risk passenger. Passenger E’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 27.49%, 38.85% and 33.66%, respectively. Therefore, passenger E is also a medium-risk passenger. Passenger F’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 14.77%, 18.43% and 66.80%, respectively, so passenger F is a low-risk passenger. Passenger G’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 13.16%, 16.27% and 70.57%, respectively. Therefore, passenger G is a low-risk passenger. Passenger H’s degrees of membership with regards to high-risk, medium-risk and low-risk levels are 16.25%, 15.78% and 67.97%, respectively, so passenger H is a low-risk passenger.

It can be seen from the results that the evaluation results of the established assessment model for the eight passengers are consistent with the basic assumptions, indicating that the model can objectively evaluate the risk of passengers and accurately distinguish passengers with different levels of risk. Compared with the traditional fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method, this model is easy to operate, and does not require experts to evaluate each index of passengers one by one. The improved calculation method of single factor evaluation vectors solves the problem that the fuzzy relation matrixes are difficult to determine, and realizes the risk classification assessment of passengers.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the analysis of classified security check modes, this paper used the comprehensive method to establish the index system of passenger risk assessment, and utilized the analytic hierarchy process and the improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method to build the assessment model for passenger risk classification. In addition, the feasibility of the model was verified by experimental results.

- (2)

- Compared with the existing research, the index system of passenger risk assessment established in this paper is simpler but better. It eliminates redundant indexes and retains key indexes, improving the efficiency and reliability of the evaluation. The assessment model for passenger risk classification based on the improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method establishes the standard of single factor evaluation, which avoids the tedious process of evaluating a large number of passengers and improves the evaluation efficiency to a certain extent.

- (3)

- However, there are some problems in the established index system of passenger risk assessment because of the lack of relevant data. Moreover, the selected examples only preliminarily verify the feasibility of the model in theory. In the future research, the index system will be tested and structurally optimized based on specific data, and the evaluation model will be further improved with the real data of passengers to make it better align with the actual demand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and Y.X.; methodology, H.Z. and Y.X.; experiments design, Y.X.; software, Y.X.; validation, Y.X., Z.J. and F.C.; investigation, Y.X. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., Z.J. and F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for helping us to improve this paper. We are also very grateful to the relevant staff for providing us with the help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire on the Weights of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes

Please rate the first-level indexes and second-level indexes of the passenger risk assessment index system according to your experience and professional judgment, and tick the corresponding boxes. The specific rating instructions are as follows:

The 1–9 scale method is used to compare the indexes at the same level in pairs, in which “1” means that the two indexes are equally important, “3” means that the former index is slightly more important than the latter, “5” means that the former index is obviously more important than the latter, “7” means that the former index is strongly important than the latter, “9” means that the former index is extremely important than the latter, and “2,4,6,8” is the intermediate value between the above adjacent values.

Table A1.

First-level indexes.

Table A1.

First-level indexes.

| First-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Basic background and Personal status | |||||||||

| Basic background and Economic situation | |||||||||

| Basic background and Personal conduct | |||||||||

| Basic background and Civil aviation travel record | |||||||||

| Personal status and Economic situation | |||||||||

| Personal status and Personal conduct | |||||||||

| Personal status and Civil aviation travel record | |||||||||

| Economic situation and Personal conduct | |||||||||

| Economic situation and Civil aviation travel record | |||||||||

| Personal conduct and Civil aviation travel record | |||||||||

Table A2.

Second-level indexes (basic background).

Table A2.

Second-level indexes (basic background).

| Second-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Gender and Age | |||||||||

| Gender and Nationality | |||||||||

| Gender and Education | |||||||||

| Age and Nationality | |||||||||

| Age and Education | |||||||||

| Nationality and Education | |||||||||

Table A3.

Second-level indexes (personal status).

Table A3.

Second-level indexes (personal status).

| Second-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Occupation and Place of residence | |||||||||

| Occupation and Religious belief | |||||||||

| Occupation and Marital status | |||||||||

| Occupation and State of health | |||||||||

| Place of residence and Religious belief | |||||||||

| Place of residence and Marital status | |||||||||

| Place of residence and State of health | |||||||||

| Religious belief and Marital status | |||||||||

| Religious belief and State of health | |||||||||

| Marital status and State of health | |||||||||

Table A4.

Second-level indexes (economic situation).

Table A4.

Second-level indexes (economic situation).

| Second-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Total assets and Annual income | |||||||||

| Total assets and Debt | |||||||||

| Total assets and Insurance amount | |||||||||

| Annual income and Debt | |||||||||

| Annual income and Insurance amount | |||||||||

| Debt and Insurance amount | |||||||||

Table A5.

Second-level indexes (personal conduct).

Table A5.

Second-level indexes (personal conduct).

| Second-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Criminal record and Default | |||||||||

| Criminal record and Awards | |||||||||

| Criminal record and Bad record of security check | |||||||||

| Default and Awards | |||||||||

| Default and Bad record of security check | |||||||||

| Awards and Bad record of security check | |||||||||

Table A6.

Second-level indexes (civil aviation travel record).

Table A6.

Second-level indexes (civil aviation travel record).

| Second-Level Indexes | Importance of Passenger Risk Assessment Indexes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Annual number of flights and Aviation insurance amount | |||||||||

| Annual number of flights and Flight information | |||||||||

| Annual number of flights and Ticket type | |||||||||

| Annual number of flights and Time of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Annual number of flights and Method of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Aviation insurance amount and Flight information | |||||||||

| Aviation insurance amount and Ticket type | |||||||||

| Aviation insurance amount and Time of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Aviation insurance amount and Method of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Flight information and Ticket type | |||||||||

| Flight information and Time of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Flight information and Method of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Ticket type and Time of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Ticket type and Method of buying tickets | |||||||||

| Time of buying tickets and Method of buying tickets | |||||||||

Appendix B

Questionnaire on the evaluation levels of passenger risk assessment indexes

Please determine the evaluation levels of attribute values of indexes according to your experience, and tick the corresponding boxes.

Table A7.

Single factor evaluation of basic background indexes.

Table A7.

Single factor evaluation of basic background indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Gender | Male | |||

| Female | ||||

| Age | 2 years old | |||

| 4 years old | ||||

| 6 years old | ||||

| 8 years old | ||||

| 10 years old | ||||

| 12 years old | ||||

| 14 years old | ||||

| 15 years old | ||||

| 16 years old | ||||

| 17 years old | ||||

| 18 years old | ||||

| 20 years old | ||||

| 22 years old | ||||

| 24 years old | ||||

| 26 years old | ||||

| 28 years old | ||||

| 30 years old | ||||

| 35 years old | ||||

| 40 years old | ||||

| 45 years old | ||||

| 50 years old | ||||

| 52 years old | ||||

| 54 years old | ||||

| 56 years old | ||||

| 58 years old | ||||

| 60 years old | ||||

| 65 years old | ||||

| 70 years old | ||||

| 75 years old | ||||

| 80 years old | ||||

| 85 years old | ||||

| Nationality | Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 0 | |||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 1 | ||||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 2 | ||||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 3 | ||||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 4 | ||||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 5 | ||||

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 6 | ||||

| Education | Master degree and above | |||

| Bachelor degree | ||||

| College degree | ||||

| High school or technical secondary school education | ||||

| Junior high school education and below | ||||

Table A8.

Single factor evaluation of personal status indexes.

Table A8.

Single factor evaluation of personal status indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Occupation | Administrative organ or institution | |||

| State-owned enterprise | ||||

| Private enterprise and others | ||||

| Unemployment | ||||

| Place of residence | Areas without terrorist attacks in 0 years | |||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 1 year | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 2 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 3 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 4 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 5 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 6 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 8 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 10 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 12 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 14 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 15 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 16 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 18 years | ||||

| Religious belief | Islam | |||

| Christianity | ||||

| Buddhism | ||||

| Others | ||||

| None | ||||

| Marital status | Married with children | |||

| Married without children | ||||

| Unmarried | ||||

| Divorced with children | ||||

| Divorced without children | ||||

| State of health | Bad | |||

| General | ||||

| Good | ||||

Table A9.

Single factor evaluation of economic situation indexes.

Table A9.

Single factor evaluation of economic situation indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Total assets/ten thousand yuan | 5 | |||

| 8 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 30 | ||||

| 40 | ||||

| 50 | ||||

| 60 | ||||

| 70 | ||||

| 80 | ||||

| 100 | ||||

| 150 | ||||

| 200 | ||||

| 300 | ||||

| Annual income/ten thousand yuan | 3 | |||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 12 | ||||

| 15 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 25 | ||||

| 30 | ||||

| 40 | ||||

| 60 | ||||

| 80 | ||||

| 100 | ||||

| Debt/ten thousand yuan | 0 | |||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 30 | ||||

| 50 | ||||

| 70 | ||||

| 80 | ||||

| 100 | ||||

| 150 | ||||

| 200 | ||||

| 300 | ||||

| 500 | ||||

| Insurance amount/ten thousand yuan | 0 | |||

| 0.3 | ||||

| 0.5 | ||||

| 0.8 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 30 | ||||

| 40 | ||||

Table A10.

Single factor evaluation of personal conduct indexes.

Table A10.

Single factor evaluation of personal conduct indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Criminal record | None | |||

| 1 time | ||||

| 2 times | ||||

| 3 times | ||||

| 4 times | ||||

| 5 times | ||||

| 6 times | ||||

| 7 times | ||||

| 8 times | ||||

| 9 times | ||||

| 10 times | ||||

| Default | None | |||

| 1 time | ||||

| 2 times | ||||

| 3 times | ||||

| 4 times | ||||

| 5 times | ||||

| 6 times | ||||

| 7 times | ||||

| 8 times | ||||

| 9 times | ||||

| 10 times | ||||

| 11 times | ||||

| 12 times | ||||

| 13 times | ||||

| 14 times | ||||

| 15 times | ||||

| Awards | None | |||

| 1 time | ||||

| 2 times | ||||

| 3 times | ||||

| 4 times | ||||

| 5 times | ||||

| 6 times | ||||

| 7 times | ||||

| 8 times | ||||

| 9 times | ||||

| 10 times | ||||

| 11 times | ||||

| 12 times | ||||

| 13 times | ||||

| 14 times | ||||

| 15 times | ||||

| Bad record of security check | None | |||

| 1 time | ||||

| 2 times | ||||

| 3 times | ||||

| 4 times | ||||

| 5 times | ||||

| 6 times | ||||

| 7 times | ||||

| 8 times | ||||

| 9 times | ||||

| 10 times | ||||

| 11 times | ||||

| 12 times | ||||

| 13 times | ||||

| 14 times | ||||

| 15 times | ||||

Table A11.

Single factor evaluation of civil aviation travel record indexes.

Table A11.

Single factor evaluation of civil aviation travel record indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Annual number of flights | 2 times | |||

| 5 times | ||||

| 10 times | ||||

| 12 times | ||||

| 15 times | ||||

| 18 times | ||||

| 20 times | ||||

| 25 times | ||||

| 30 times | ||||

| 35 times | ||||

| 40 times | ||||

| 45 times | ||||

| 50 times | ||||

| 55 times | ||||

| 60 times | ||||

| 65 times | ||||

| Aviation insurance amount/ten thousand yuan | 0 | |||

| 20 | ||||

| 40 | ||||

| 60 | ||||

| 80 | ||||

| 100 | ||||

| 120 | ||||

| 140 | ||||

| 160 | ||||

| 180 | ||||

| 200 | ||||

| 220 | ||||

| 240 | ||||

| Flight information | Areas without terrorist attacks in 0 years | |||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 1 year | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 2 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 3 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 4 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 5 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 6 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 8 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 10 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 12 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 14 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 15 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 16 years | ||||

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 18 years | ||||

| Ticket type | Round-trip ticket | |||

| One-way ticket | ||||

| Time of buying tickets | 1/12 days before departure | |||

| 0.5 days before departure | ||||

| 1 day before departure | ||||

| 2 days before departure | ||||

| 3 days before departure | ||||

| 5 days before departure | ||||

| 7 days before departure | ||||

| 8 days before departure | ||||

| 10 days before departure | ||||

| 12 days before departure | ||||

| 14 days before departure | ||||

| 20 days before departure | ||||

| 30 days before departure | ||||

| 40 days before departure | ||||

| 50 days before departure | ||||

| 60 days before departure | ||||

| Method of buying tickets | Online payment | |||

| Cash payment | ||||

Appendix C

The data obtained from the questionnaire in Appendix B are as follows. The numerical values in the tables are the proportions of the number of experts who judge the attribute values of indexes belonging to the evaluation levels to all the experts. Figures of the fitting functions corresponding to the single factor evaluation vectors of the other continuous second-level indexes except age are also included.

Table A12.

Single factor evaluation of basic background indexes.

Table A12.

Single factor evaluation of basic background indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Gender | Male | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Female | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Age | 2 years old | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 years old | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 years old | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 8 years old | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 10 years old | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 12 years old | 0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| 14 years old | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| 15 years old | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 16 years old | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 17 years old | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 18 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 20 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 22 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 24 years old | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 26 years old | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 28 years old | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 30 years old | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 35 years old | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 40 years old | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 45 years old | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| 50 years old | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 52 years old | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 54 years old | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 56 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 58 years old | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 60 years old | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 65 years old | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 70 years old | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 75 years old | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| 80 years old | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 85 years old | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| Nationality | Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| Countries where the annual number of wars or terrorist attacks is 6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Education | Master degree and above | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Bachelor degree | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| College degree | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| High school or technical secondary school education | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Junior high school education and below | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

Table A13.

Single factor evaluation of personal status indexes.

Table A13.

Single factor evaluation of personal status indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Occupation | Administrative organ or institution | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| State-owned enterprise | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Private enterprise and others | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Unemployment | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Place of residence | Areas without terrorist attacks in 0 years | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 1 year | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 2 years | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 3 years | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 4 years | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 5 years | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 6 years | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 8 years | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 10 years | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 12 years | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 14 years | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 15 years | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 16 years | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 18 years | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Religious belief | Islam | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Christianity | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Buddhism | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Others | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| None | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Marital status | Married with children | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Married without children | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Unmarried | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Divorced with children | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Divorced without children | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| State of health | Bad | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| General | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Good | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

Table A14.

Single factor evaluation of economic situation indexes.

Table A14.

Single factor evaluation of economic situation indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Total assets/ten thousand yuan | 5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 10 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 20 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 30 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 40 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 50 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 60 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 70 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 80 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 100 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 150 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 200 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 300 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Annual income/ten thousand yuan | 3 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 10 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 12 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 15 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| 20 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 25 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 30 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 40 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| 60 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 80 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| 100 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Debt/ten thousand yuan | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 20 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 30 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 50 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| 70 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| 80 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| 100 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| 150 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 200 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 300 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 500 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Insurance amount/ten thousand yuan | 0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| 3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 30 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 40 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

Table A15.

Single factor evaluation of personal conduct indexes.

Table A15.

Single factor evaluation of personal conduct indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Criminal record | None | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 time | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 2 times | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| 3 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 4 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 5 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 6 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Default | None | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 time | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| 2 times | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| 3 times | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 4 times | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| 5 times | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 6 times | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| 7 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 8 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 9 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 10 times | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 11 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15 times | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Awards | None | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| 1 time | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 2 times | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 3 times | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| 4 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 5 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 6 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 7 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 8 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 9 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 10 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 11 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 12 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 13 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 14 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 15 times | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Bad record of security check | None | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 time | 1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 2 times | 2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| 3 times | 3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| 4 times | 4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | |

| 5 times | 5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | |

| 6 times | 6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| 7 times | 7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | |

| 8 times | 8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | |

| 9 times | 9 | 0.9 | 0.1 | |

| 10 times | 10 | 0.9 | 0.1 | |

| 11 times | 11 | 1 | 0 | |

| 12 times | 12 | 1 | 0 | |

| 13 times | 13 | 1 | 0 | |

| 14 times | 14 | 1 | 0 | |

| 15 times | 15 | 1 | 0 | |

Table A16.

Single factor evaluation of civil aviation travel record indexes.

Table A16.

Single factor evaluation of civil aviation travel record indexes.

| Indexes | Attribute Values of Indexes | Evaluation Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Medium-risk | Low-risk | ||

| Annual number of flights | 2 times | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 5 times | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 10 times | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 12 times | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 15 times | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 18 times | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 20 times | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 25 times | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 30 times | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 35 times | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| 40 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 45 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 50 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 55 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 60 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 65 times | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Aviation insurance amount/ten thousand yuan | 0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 20 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 40 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 60 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 80 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 100 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 120 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| 140 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 160 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 180 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 200 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| 220 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 240 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Flight information | Areas without terrorist attacks in 0 years | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 1 year | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 2 years | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 3 years | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 4 years | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 5 years | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 6 years | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 8 years | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 10 years | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 12 years | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 14 years | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 15 years | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 16 years | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| Areas without terrorist attacks in 18 years | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Ticket type | Round-trip ticket | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| One-way ticket | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Time of buying tickets | 1/12 days before departure | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 0.5 days before departure | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 1 day before departure | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| 2 days before departure | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 3 days before departure | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 5 days before departure | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |

| 7 days before departure | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| 8 days before departure | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| 10 days before departure | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| 12 days before departure | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| 14 days before departure | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| 20 days before departure | 0 | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| 30 days before departure | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| 40 days before departure | 0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| 50 days before departure | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 60 days before departure | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Method of buying tickets | Online payment | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Cash payment | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

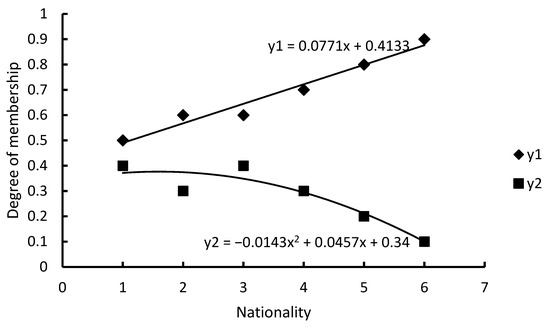

Figure A1.

Single factor evaluation for the index of nationality.

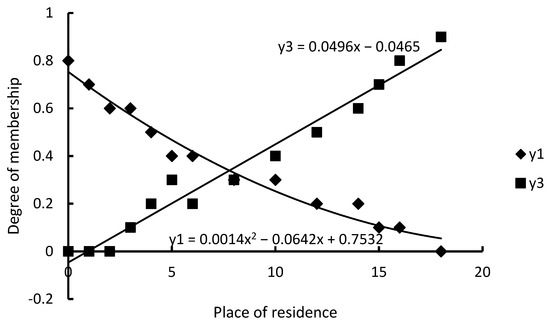

Figure A2.

Single factor evaluation for the index of place of residence.

Figure A3.

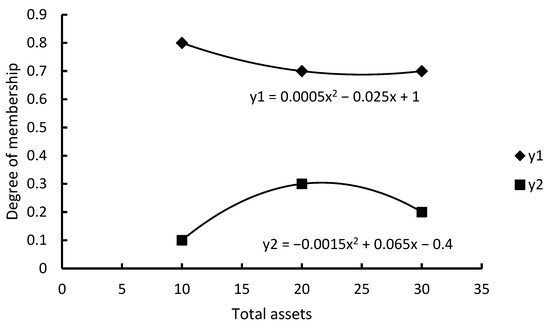

Single factor evaluation for the index of total assets (0–10 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A4.

Single factor evaluation for the index of total assets (10–30 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A5.

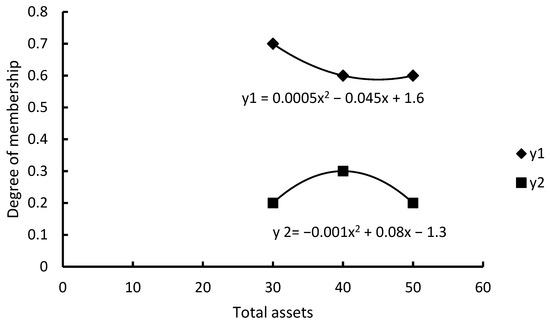

Single factor evaluation for the index of total assets (30–50 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A6.

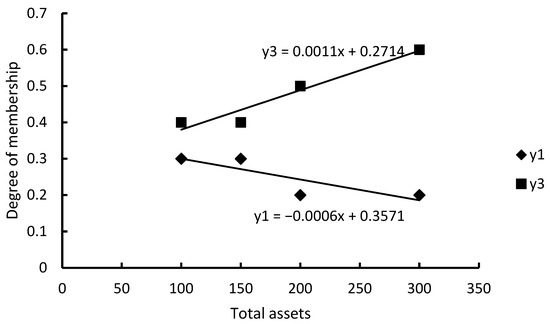

Single factor evaluation for the index of total assets (50–100 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A7.

Single factor evaluation for the index of total assets (more than 100 ten thousand yuan).

Figure A8.

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual income (0–5 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A9.

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual income (5–10 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A10.

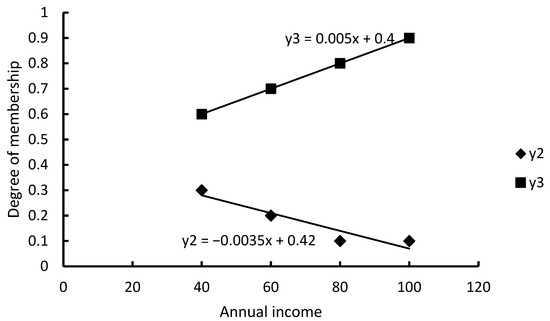

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual income (10–20 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A11.

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual income (20–40 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A12.

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual income (more than 40 ten thousand yuan).

Figure A13.

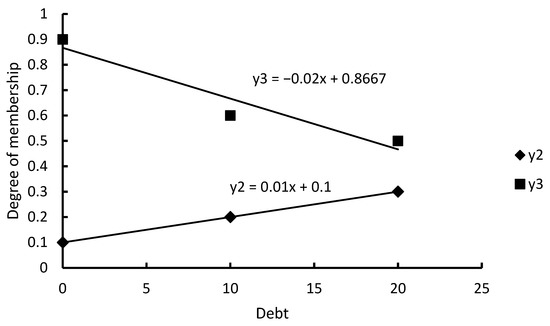

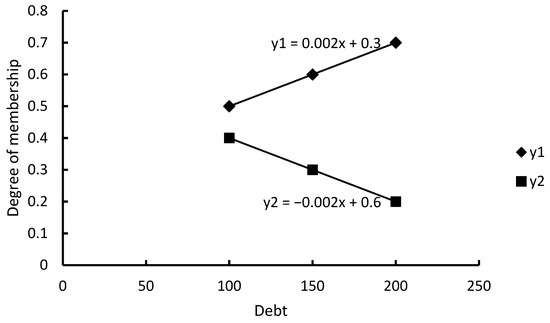

Single factor evaluation for the index of debt (0–20 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A14.

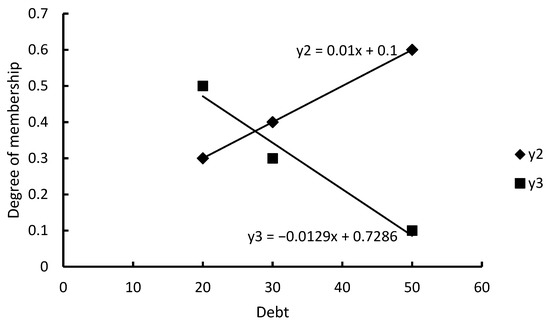

Single factor evaluation for the index of debt (20–50 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A15.

Single factor evaluation for the index of debt (50–100 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A16.

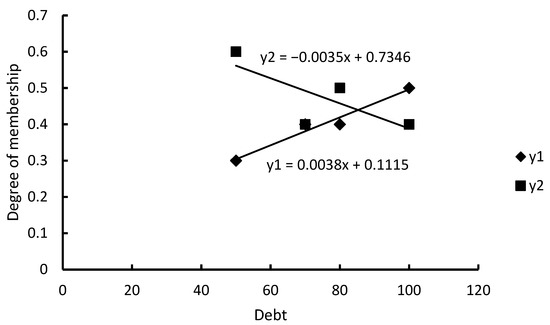

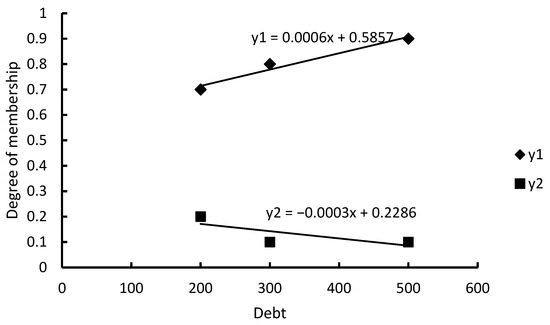

Single factor evaluation for the index of debt (100–200 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A17.

Single factor evaluation for the index of debt (more than 200 ten thousand yuan).

Figure A18.

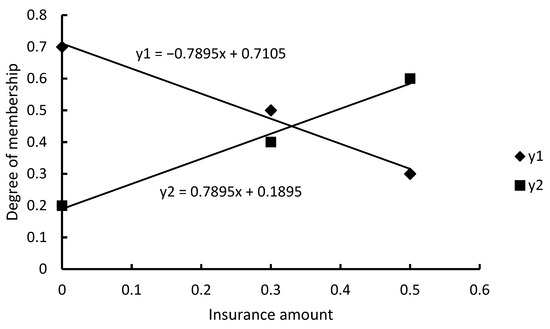

Single factor evaluation for the index of insurance amount (0–0.5 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A19.

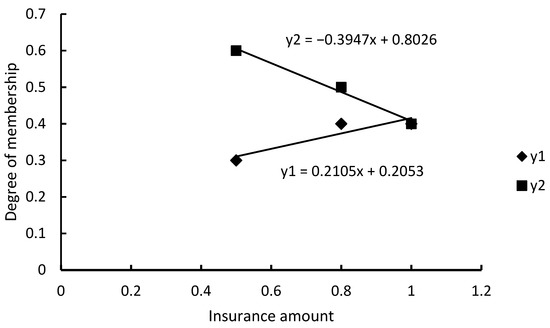

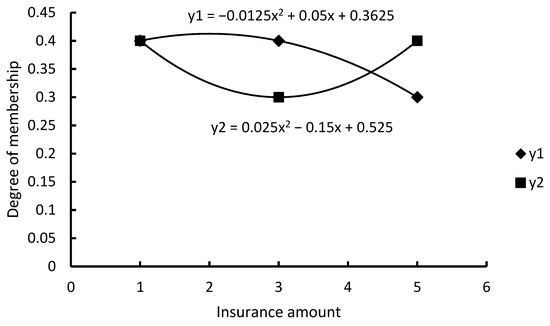

Single factor evaluation for the index of insurance amount (0.5–1 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A20.

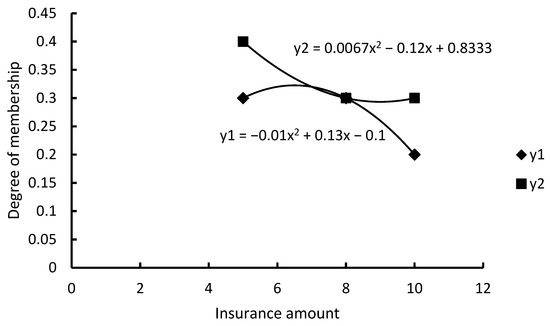

Single factor evaluation for the index of insurance amount (1–5 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

Figure A21.

Single factor evaluation for the index of insurance amount (5–10 (inclusive) ten thousand yuan).

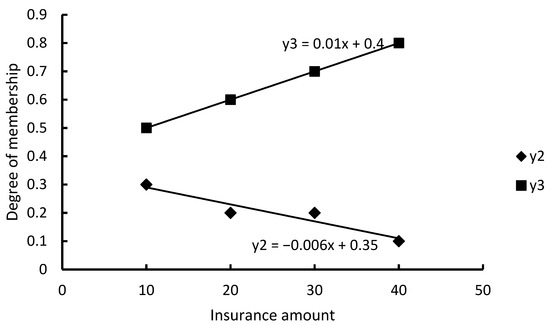

Figure A22.

Single factor evaluation for the index of insurance amount (more than 10 ten thousand yuan).

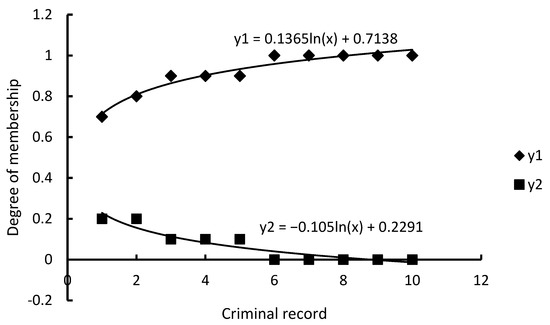

Figure A23.

Single factor evaluation for the index of criminal record (one and more times).

Figure A24.

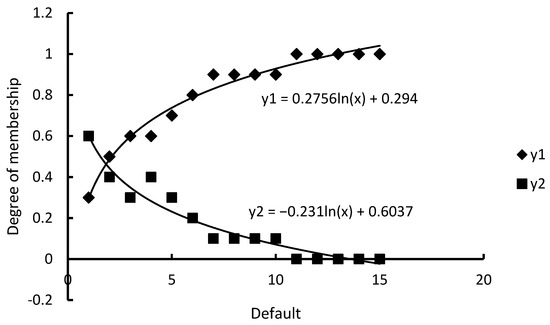

Single factor evaluation for the index of default (one and more times).

Figure A25.

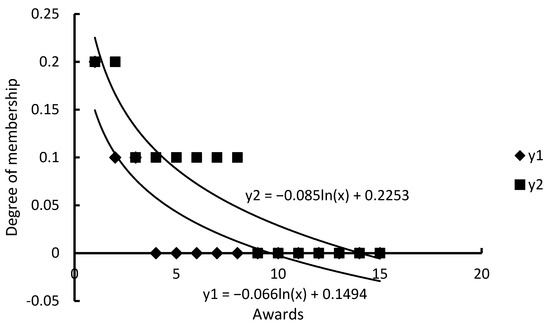

Single factor evaluation for the index of awards (one and more times).

Figure A26.

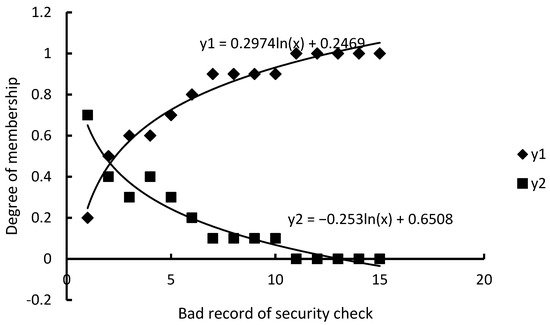

Single factor evaluation for the index of bad record of security check (one and more times).

Figure A27.

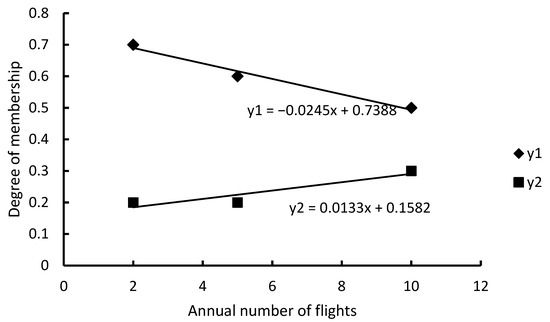

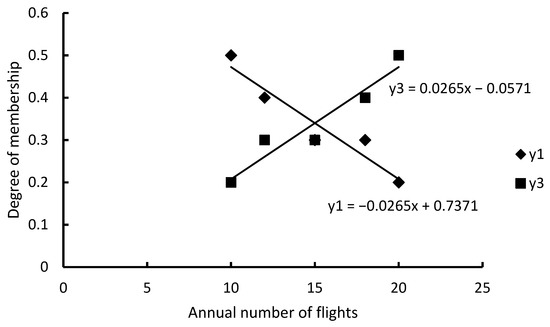

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual number of flights (0–10 times).

Figure A28.

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual number of flights (11–20 times).

Figure A29.

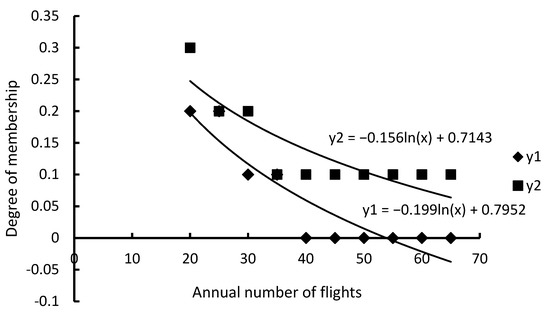

Single factor evaluation for the index of annual number of flights (more than 20 times).

Figure A30.

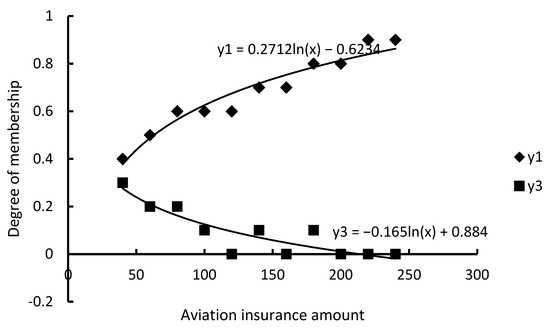

Single factor evaluation for the index of aviation insurance amount (40 ten thousand yuan and above).

Figure A31.

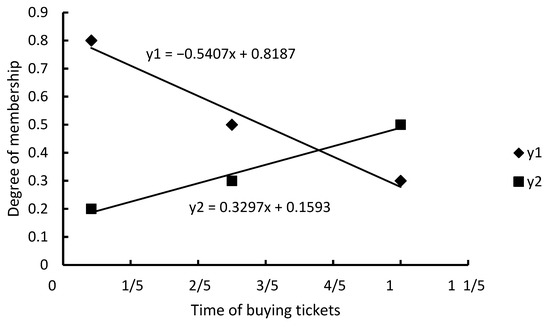

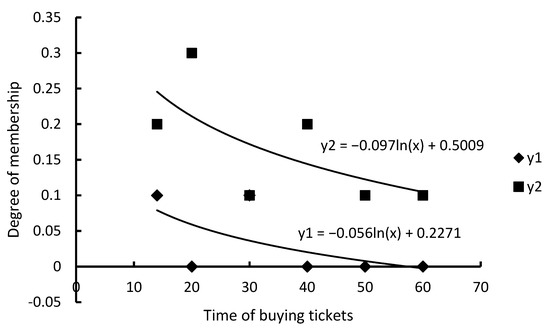

Single factor evaluation for the index of time of buying tickets (1 day before departure).

Figure A32.

Single factor evaluation for the index of time of buying tickets (1–3 days before departure).

Figure A33.

Single factor evaluation for the index of time of buying tickets (4–7 days before departure).

Figure A34.

Single factor evaluation for the index of time of buying tickets (8–14 days before departure).

Figure A35.

Single factor evaluation for the index of time of buying tickets (more than 14 days before departure).

References

- McLay, L.A.; Jacobson, S.H.; Kobza, J.E. A multilevel passenger screening problem for aviation security. Nav. Res. Logist. 2006, 53, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, V.L.L.; Batta, R.; Lin, L. Passenger grouping under constant threat probability in an airport security system. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 168, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.F.; Batta, R.; Drury, C.G.; Lin, L. Passenger grouping with risk levels in an airport security system. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 194, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeske, K.D.; Lauer, T.W. Optimizing airline passenger prescreening systems with Bayesian decision models. Comput. Oper. Res. 2011, 39, 1827–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.F.; Parab, G.; Batta, R.; Lin, L. Simulation-based selectee lane queueing design for passenger checkpoint screening. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Luh, H.; Zhang, Z.G. A queueing model for tiered inspection lines in airports. Int. J. Inf. Manage. Sci. 2016, 27, 147–177. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Zhuang, J. N-stage security screening strategies in the face of strategic applicants. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 165, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Sheng, W.G.; Sun, X.M.; Chen, S.Y. Airline passenger profiling based on fuzzy deep machine learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 2911–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.Q.; Wang, D. Research on the airport security inspection system based on passenger classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information, Computer and Education Engineering (ICICEE), Hong Kong, China, 11–12 November 2017; Available online: http://dpi-journals.com/index.php/dtcse/article/view/17215 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Song, C.; Zhuang, J. Modeling Precheck parallel screening process in the face of strategic applicants with incomplete information and screening errors. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, L.A.; Nikolaev, A.; Lee, A.J.; Fletcher, K.; Jacobson, S.H. A review of risk-based security and its impact on TSA PreCheck. IISE Trans. 2020, 53, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Chen, Y.T.; Wu, X.J. A multi-tier inspection queueing system with finite capacity for differentiated border control measures. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60489–60502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Koh, B.; Raghunathan, S. An analysis of the impact of passenger profiling for transportation security. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 1287–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, H.; Kwark, Y.; Mai, B.; Raghunathan, S. Passenger profiling and screening for aviation security in the presence of strategic attackers. Decis. Anal. 2013, 10, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, A.; Paul, J.A. Optimal allocation of resources in airport security: Profiling vs. Screening. Oper. Res. 2014, 62, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.G.; Mueller, J. Responsible policy analysis in aviation security with an evaluation of PreCheck. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 48, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Brooks, N. Evolving risk-based security: A review of current issues and emerging trends impacting security screening in the aviation industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 48, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, T.; Bearth, A.; Siegrist, M.; Ghelfi, S.M. The perceived costs and benefits that drive the acceptability of risk-based security screenings at airports. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 100, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, L.A.; Lee, A.J.; Jacobson, S.H. Risk-based policies for airport security checkpoint screening. Transp. Sci. 2010, 44, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.G.; Mueller, J. Risk and economic assessment of expedited passenger screening and TSA PreCheck. J. Transp. Secur. 2017, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.L. Study on the Index System of the Airport Passengers Classification Based on Risk. Master’s Thesis, Civil Aviation University of China, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.G.; Jiang, Z.F.F. Improving security checks and passenger risk evaluation with classification of airline passengers. Data Anal. Knowl. Discov. 2020, 4, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).