Abstract

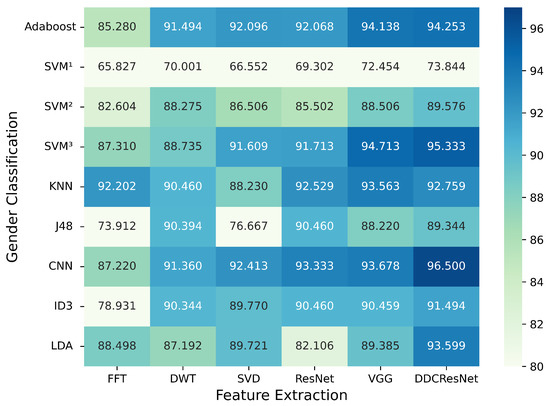

The fingerprint is an important biological feature of the human body, which contains abundant biometric information. At present, the academic exploration of fingerprint gender characteristics is generally at the level of understanding, and the standardization research is quite limited. A robust approach is presented in this article, Dense Dilated Convolution ResNet Autoencoder, to extract valid gender information from fingerprints. By replacing the normal convolution operations with the atrous convolution in the backbone, prior knowledge is provided to keep the edge details, and the global reception field can be extended. The results were explored from three aspects: (1) Efficiency of DDC-ResNet. We conducted experiments using a combination of 6 typical automatic feature extractors with 9 classifiers for a total of 54 combinations are evaluated in our dataset; the experimental results show that the combination of methods we used achieved an average accuracy of 96.5%, with a classification accuracy of 97.52% for males and 95.48% for females, which outperformed the other experimental combinations. (2) The effect of the finger. The results showed that the right ring finger was the most effective for finger classification by gender. (3) The effect of specific features. We used the Class Activating Mapping method to plot fingerprint concentration thermograms, which allowed us to infer that fingerprint epidermal texture features are related to gender. The results demonstrated that autoencoder networks are a powerful method for extracting gender-specific features to help hide the privacy information of the user’s gender contained in the fingerprint. Our experiments also identified three levels of features in fingerprints that are important for gender differentiation, including loops and whorls shape, bifurcations shape, and line shapes.

1. Introduction

Fingerprint gender identification aims to extract gender-related features from an unidentified fingerprint to recognize one’s gender information. It can be divided into two stages, namely extracting as well as classifying [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], in which the first step is of great significance, since the effectiveness of gender identification is determined primarily by the sufficiency of gender-related features. Nowadays, classifying ridge-related features extracted manually has achieved fairly good results, reaching an overall accuracy of 90% for the average [8,9,10]. High performances, however, depend strongly on the manual extraction of features from well-selected regions [11]. These methods have major shortcomings, such as high error, weak robustness, and high labor consumption. So far, with the growing popularity of machine learning and deep learning, automatic feature extraction has become a major focus.

To realize the automatic feature extraction, considerable work has been done. In machine learning, methods such as DWT, SVD, PCA, as well as FFT are extensively used [3,12,13]. For deep learning-based methods, including deep autoencoder, neural networks such as VGG and ResNet have been investigated [14].

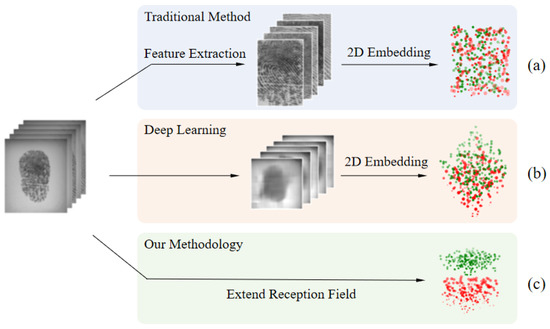

Although numerous algorithms have been proposed, there are still two major challenges. First, traditional approaches acquire excessive labor consumption and lack automation. Second, the automatic feature extraction method lacks robustness, which only concerns regions, instead of considering the global field. Figure 1 shows the difference between the normal automatic feature extraction method and the deep neural network with global reception consideration. The latter can divide the feature space normatively. In addition, private datasets with disparate data distributions and sizes will directly influence the accuracy, and fingerprint information contains a lot of noise, resulting in low recognition accuracy. Thus, because of the above challenges, we propose a global feature extraction method to improve the efficiency of gender classification.

Figure 1.

General automatic gender classification methods preview. (a) Traditional method for gender feature extraction; (b) Deep learning method for gender feature extraction; (c) We propose a feature extraction method of fingerprint that takes global features into account.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- We propose a feature extraction method of fingerprint that takes global features into account. For existing typical automatic feature extraction methods and classification methods, we make comprehensive comparisons with fair implementation details.

- We make a comprehensive comparison to test the efficiency of our method. The finger with the richest gender-related characteristics is detected using the highest-performance method. Finally, we visualize the concentrations using the selected method, which indicates the regions with the highest contributions and their corresponding specific features in the gender identification task.

- We will finally open source the dataset since the open-source datasets in fingerprint gender classification are limited.

2. Related Work

Previous discussions have demonstrated that gender-related features have a significant impact on fingerprint gender identification. In this section, we will review the papers according to the extraction method of fingerprint gender features.

Manual feature extraction. Manual feature extraction was the earliest method of fingerprint gender feature extraction. Initially, it was found that gender could be identified by the ridges of the fingerprint epidermis [11,15,16]. Acree et al. manually calculated the number of ridges in 66 regions of the fingerprint epidermis and demonstrated that the number of ridges can determine gender [15]. Guangdin found a ridge density threshold of 13 ridges/25 mm2, which determines gender as male when the ridge density is below the threshold [16]. In other words, females have a higher ridge density, possibly because they have a lower ridge width [11]. Owing to the low accuracy of manually extracted fingerprint epidermal features, Badawi proposed manual extraction of ridge counts, ridge thickness to valley thickness ratio (RTVTR) and white line counts and used fuzzy CMeans, Linear Discriminant Analysis and neural networks as classifiers to determine gender. The method used manual extraction of fingerprint epidermal features and classification using an automatic classifier to obtain accuracies of 80.39%, 86.5%, and 88.5%, respectively [10].

Automatic feature extraction. Due to the inevitable error and high manpower consumption of manual feature extractions, automatic fingerprint extraction has been proposed. In 2012, ridge features have been analyzed in the spatial domain using FFT, 2D-DCT, and PSD [12], reaching an accuracy of 90% for females and 79.07% for males, respectively. In the same year, Gnanasivam proposed a method using DWT and SVD as the feature extractor [3]. In 2014, Marasco used LBP and LPQ on texture features and used PCA to reduce the features, then the kNN classifier was applied to the extracted features [13]. The author reached 88.7% prediction rate.

Deep learning feature extraction. Due to the development of convolutional neural networks, deep learning has been widely used in recent years for feature extraction tasks, especially in the field of biometrics. Initially, people used a combination of automatic feature extraction and neural networks. Gupta used the discrete wavelet transform to extract fingerprint features, which were then output to a back propagation neural network for gender classification, ultimately achieving a classification accuracy of 91.45% [4]. To obtain better performance, biometric feature extraction was performed entirely using deep learning methods. Shehu used CNN models, specifically ResNet-34, trained with transfer learning techniques to complete fingerprint feature extraction and achieved a combined classification accuracy of 75.20% [17]. In manual biometric feature extraction tasks, most require a priori knowledge. Since the existence of deep convolutional self-encoder neural networks, Chen et al. have proposed an autoencoder-based framework to extract feature information from medical images due to the autoencoder’s ability to automatically extract important essential features from the data. In recent years, many studies have shown that autoencoders have shown outstanding performance in feature extraction tasks, especially in the field of biometrics [14]. In addition, the combination of encoder and classifier also achieved satisfactory results on many deep learning tasks. Prajwal Kaushal et al. used BERT in combination with six machine learning classification algorithms for sentiment analysis and personality prediction, respectively, and the experiments found that the SVM classifier performed better than the other algorithms and achieved good results in the task of predicting personality traits and qualities of Twitter users [18]. Yuhao Zhao et al. proposed a multichannel feature relationship classification model of BERT and LSTM. The semantic information of the two models is fused through an attention mechanism to obtain the final classification results, and the method outperforms previous design methods [19]. This method of combining encoder and classifier for experiments is widely used on various deep learning tasks and has excellent performance in deep feature mining of data.

3. Materials and Methods

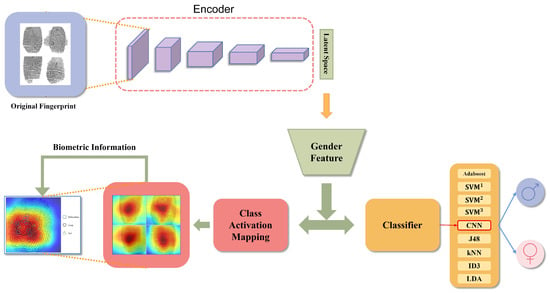

In this section, we will introduce our approaches and the implementation principles of automatic feature extraction methods. In addition, we will outline the classification methods utilized in this paper in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodologies Demonstrate: The original fingerprint images will walk through an encoder (DDCResNet) to extract gender features. The gender features could be used in class activation for biometric information or in a classifier (CNN) for gender classification.

3.1. Dataset

The fingerprint dataset used in experiments is obtained from ZK fingerprint acquisition equipment (Figure 3) with 500 dpi, containing 200 persons (102 females and 98 males) and 6000 images. Each finger is collected 3 times to ensure the quality of the fingerprint image.

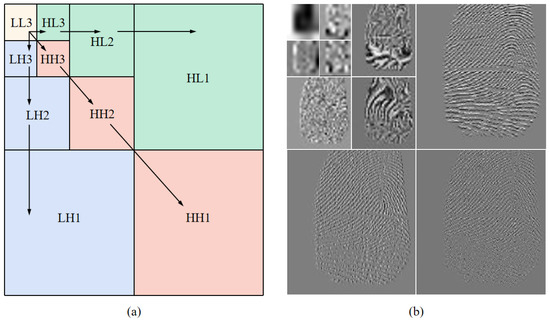

Figure 3.

Discrete Wavelet Transform for the fingers’ gender classification. (a) Wavelet decomposes an image into sub-bands containing frequency and orientation information to represent valid signals. Specifically, a fingerprint image is decomposed into four sub-bands at one level, namely low–low (LL), low–high (LH), high–low (HL), and high–high (HH); (b) Fingerprint image decomposition feature signal.

3.2. Implementation Details

- a.

- Pre-processing: In the prepossessing step, we resize each fingerprint image to 256 × 256 and normalize it to . Train:Test ratio is 4:1, No repetitive finger is guaranteed in both the training set and the test set.

- b.

- Encoders: In the encoding step, the implementation details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Encoder details.

Table 1. Encoder details. - c.

- Classifiers: In the classification step, the implementation details are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Classifier details.

Table 2. Classifier details.

3.3. Feature Extraction

3.3.1. Discrete Wavelet Transformation

Wavelet has been extensively applied in feature extraction, soft-biometrics recognition, and denoising, etc. It decomposes an image into sub-bands containing frequency and orientation information to represent valid signals. Specifically, a fingerprint image is decomposed into four sub-bands at one level, namely low–low (LL), low–high (LH), high–low (HL), and high–high (HH), which is shown in Figure 3. Typically, the LL sub-band will be decomposed repeatedly since it is thought to represent the most energy, and k refers to the repeat times. If k is set, (3 × k) + 1 sub-bands are available. The energy of each sub-band is calculated by Equation (1), which will be used as a feature vector for gender classification (), where represents the pixel at the position i and j at the kth level. W and H represent the width and the height of the sub-band, respectively.

3.3.2. Singular Value Decomposition

The fundamental of SVD is that any rectangular matrix can be transformed into the product of three new matrices. Specifically, given a fingerprint image matrix A with H rows and W columns, it can be factored into U, S, and V by using Equation (2), where and and S are diagonal matrices that contain the square root eigenvalues with the size of H by W, which is stored for gender classification.

3.3.3. Fast Fourier Transform

The FFT is used to transform a fingerprint image into the frequency domain. The transformed vector contains most of the information in the spatial domain and is used for gender classification. It is presented in Equation (3), where M and N represent the height and width of the fingerprint image, k and l represent frequency variables, respectively. 0 ≤ m, k ≤ M − 1, 0 ≤ n, 1 ≤ N − 1.

3.3.4. Our Method

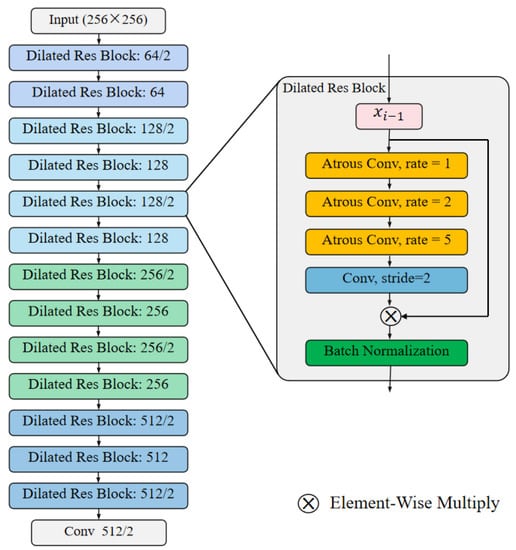

Autoencoder neural networks can be divided into encoder and decoder. Concretely, in the encoder step, the low-dimensional data will be compressed into a feature vector in high-dimensional space, and the decoder step is to reconstruct the original data without redundant features. The general equation is described in (4) where f is the activation function (in this work, we utilized leaky Relu), the W is the parameter matrix, and b is a vector of bias parameters. The feature vector can be optimized by minimizing the distance between the original data and the reconstructed data and can be used for gender classification. Our method uses ResNet as the backbone and uses the atrous convolution operation to replace normal convolutions, as shown in Figure 4. In the block res, we utilize atrous rates as 1, 2, and 5 to prevent the gridding effect [21]. In addition, we put the feature vector output from the final convolution layer in the decoder into the classifier for classification.

Figure 4.

DDC-ResNet.

3.4. Gender Classification

To ensure the fairness of experiments, we adopt nine commonly used classifiers in gender classification problems, which are CNN, SVM (three kernels), kNN, Adaboost, J48, ID3, and LDA. Among them, the three kernels in SVM refer to linear, radial basis function, and polynomial, respectively. CNN is made up of fully connected layers. These are all mainstream algorithms used in classification tasks. Therefore, we only highlight their implementation details in the experimental result section, and more details of the methods are presented in the experimental setup section.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we first introduce our dataset and adopted implementation details. In the experimental stage, factors that affect gender-related features will be analyzed comprehensively to provide some useful conclusions.

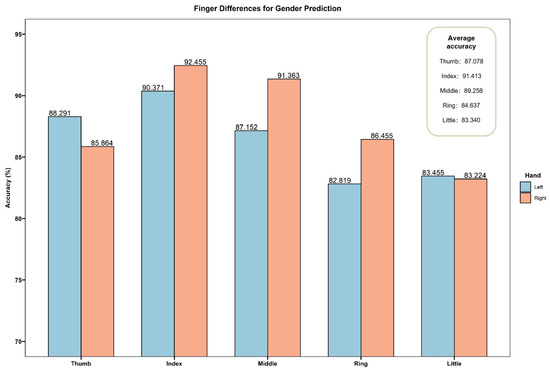

4.1. Effect of Fingers

After studying the effect of different methods on gender-related features, we further explore the effect of each finger. We divide the testing fingerprints into 10 sets, each set of which corresponds to a specific finger that contains 660 fingerprint images. We apply the DDC-ResNet coupled with CNN (best-performance method above) to test the 10 sets, as show in Figure 5. The result indicates that for each specific finger, the right ring finger (R2) shows the highest accuracy, reaching 92.455%. For five pairs of fingers, ring fingers outperform other pairs, reaching an accuracy of 91.413%. For the overall hand, the right hand achieves a higher accuracy than the left hand, reaching 87.872%. To better understand the effect of fingers on gender-related features, more careful studies will be carried out in the following part.

Figure 5.

This is a heat map of different networks. The x axis presents the network of feature extraction model and the y axis presents the network of a gender classification model. Value in each cell represents the average accuracy (%). The most accurate model pair is the CNN and the DDCResNet.

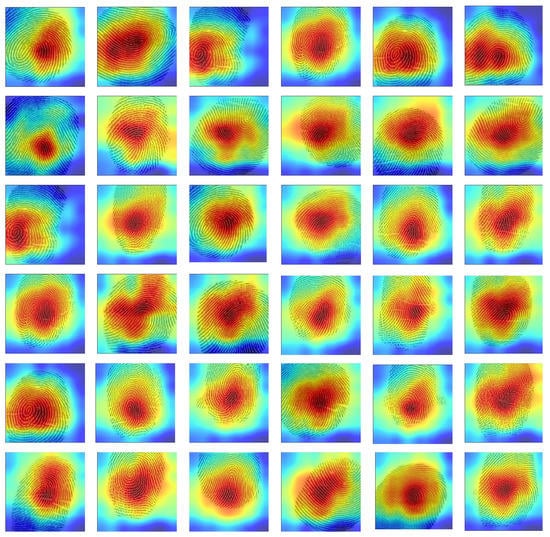

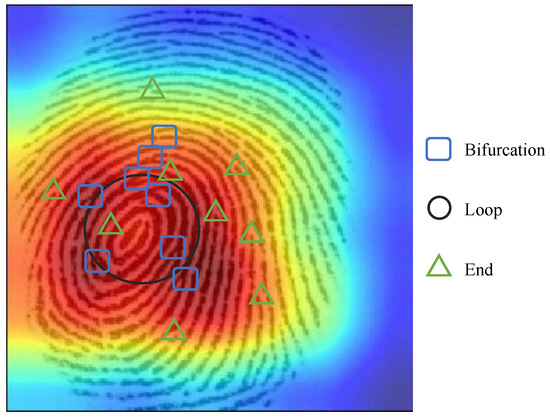

4.2. Effect of Features

To further research on gender-related features, we apply the grad-cam [22] technique to visualize the heat maps, seeing which part contributes the most. Specifically, on the basis of earlier results, we visualize testing fingers by using the DDC-ResNet extractor. The overview of visualization is shown in Figure 2, it can be seen that concentrations are mainly on or around the center of the fingerprints. Detailed observation is shown in Figure 3. The concentration covers the whorl part, which belongs to the pattern features of level 1. Further observation reveals that bifurcations are collected in concentration regions. However, we excluded the sweat pores around the bifurcations since other parts containing more remarkable sweat pores have not received attention. We also find that the concentration regions prefer to be continuous parts. Therefore, it is not hard to say that the foundation of recognition is complete ridges, which explains the reason for the manual extraction of minutiae features in well-selected continuous regions.

5. Discussion

In this study, we use deep learning methods for fingerprint epidermal gender feature extraction. The results show that the combination of our proposed feature extractor DDC-ResNet and CNN classifier outperforms other combinations, with an average accuracy of 96.50%. In addition, the study found that most males were more correct in their predictions than females, with an average accuracy rate of 87.330% for males and 87.205% for females. The highest accuracy rate for males was 2.04% higher than that of females. In particular, for the combination, the difference was more than 10%, indicating that the male fingerprint epidermis is richer in gender-related features than the female. In the study of the fingers, we found that the right ring finger had the highest accuracy rate of 92.455%. Among the five pairs of fingers, the ring finger performed significantly better than the other fingers and had a higher average accuracy rate for the right hand than the left hand, with an average accuracy rate of 87.872% for the right hand and 86.418% for the left hand. Most studies of manually extracted features have focused on the ridges of the fingerprint epidermis. This study visualized the heat map through the grad-cam technique and found that the concentration was mainly on or around the center of the fingerprint, as shown in Figure 6. with the concentration area tending to be more of a continuous section, and it can be said that the basis of recognition is the complete ridge feature, thus, also confirming the reason for the manual extraction of features and also validating the interpretability of this paper. This work not only comprehensively explores the efficiency of the proposed method, but also provides a way to observe fingerprint identification features much more closely. These specific features will be quantified in the future to further explore the impact on fingerprint recognition further.

Figure 6.

Overall heatmaps.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes an effective network considering the global reception field in the gender classification task, which is realized by replacing normal convolutions with dilated convolutions in the extraction method. The experiment thoroughly explores efficiency from three aspects. First, we compare our method with various methods with fair implementation details in our dataset. Six typical automatic feature extraction methods like DWT, SVD, VGG, and our method coupled with nine mainstream classifiers such as Adaboost, kNN, SVM, CNN, etc., a total of 54 combinations are evaluated. The experimental results reveal that the combination of our extractor with the CNN classifier outperforms other combinations. For average accuracy, it reaches 96.50% and for separate gender accuracy, it reaches 0.9752 (males)/0.9548 (females). Second, we investigate the effect of fingers by classifying gender using separate fingers and find the best-performing finger is the right ring finger, which reaches an accuracy of 92.455%, as shown in Figure 7. Third, we study the effect of features by visualizing the concentrations of fingerprints. Depending on the analysis, loops/whorls (level 1), bifurcations (level 2), and line shapes (level 3) may have a close relationship with gender, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Estimate performance of each finger (%), in which represents Finger x. The index from 1 to 5 means little finger, ring finger, middle finger, index finger, and thumb, respectively. In addition, the represents the average of their fingers. The highest average accuracy is index finger at 91.413% and the lowest is little finger at 83.340%.

Figure 8.

This study visualized the heat map through the grad-cam technique and found that the concentration was mainly on or around the center of the fingerprint, with the concentration area tending to be more of a continuous section, and it can be said that the basis of recognition is the complete ridge feature, thus, also confirming the reason for the manual extraction of features and also validating the interpretability of this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q.; data curation, M.Q.; formal analysis, F.W. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the serving local special projects of the education office of Shaanxi province, China [grant number No. 22JC019] and China Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program [grant number S202110708067].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shaanxi University of Science and Technology (710021, 31 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

This study does not involve any informed consent issues since there all the data used in this paper is simulated.

Data Availability Statement

If anyone wants the data availability of this paper, please send an e-mail to qiyong@sust.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| DDC-ResNet | Dense Dilated Convolution ResNet |

| CAM | Class Activating Mapping |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transformation |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| VGG | Visual Geometry Group |

| 2D-DCT | 2-Dimension Discrete Cosine Transform |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| LBP | Local Binary Pattern |

| LPQ | Local Phase Quantization |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| kNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| ID3 | Iterative Dichotomiser 3 |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

References

- Abdullah, S.; Rahman, A.F.N.A.; Abas, Z.A.; Saad, W.H.B.M. Fingerprint gender classification using univariate decision tree (j48). Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.F.; Rahman, A.; Abas, Z.; Saad, W. Support Vector Machine, Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network, Bayes Net and k-Nearest Neighbor in Classifying Gender using Fingerprint Features. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2016, 14, 336. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanasivam, P.; Muttan, D.S. Fingerprint gender classification using wavelet transform and singular value decomposition. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1205.6745. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Rao, A.P. Fingerprint based gender classification using discrete wavelet transform & artificial neural network. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Mob. Comput. 2014, 3, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Maheshwary, P. A novel technique for fingerprint classification based on naive bayes classifier and support vector machine. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 975, 8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, V.; Gurupriya, S.; Gayadhri, S.; Sowmya, S. Dactyloscopy Based Gender Classification Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on System, Computation, Automation and Networking (ICSCAN), Pondicherry, India, 29–30 March 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, M.K.; Annadate, S. Analysis of fingerprint image for gender classification or identification: Using wavelet transform and singular value decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computing Communication Control and Automation, Pune, India, 26–27 February 2015; pp. 650–654. [Google Scholar]

- Wedpathak, G.S.; Kadam, D.; Kadam, K.; Mhetre, A.; Jankar, V. Fingerprint Based Gender Classification Using ANN. Int. J. Recent Trends Eng. Res. (IJRTER) 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Arun, K.; Sarath, K. A machine learning approach for fingerprint based gender identification. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Recent Advances in Intelligent Computational Systems, Trivandrum, India, 22–24 September 2011; pp. 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Badawi, A.M.; Mahfouz, M.; Tadross, R.; Jantz, R. Fingerprint-Based Gender Classification. IPCV 2006, 6, l. [Google Scholar]

- Kralik, M.; Novotny, V. Epidermal ridge breadth: An indicator of age and sex in paleodermatoglyphics. Var. Evol. 2003, 11, 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Mazumdar, S.G. Fingerprint based gender identification using frequency domain analysis. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2012, 3, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Marasco, E.; Lugini, L.; Cukic, B. Exploiting quality and texture features to estimate age and gender from fingerprints. In Biometric and Surveillance Technology for Human and Activity Identification XI, Proceedings of the SPIE Defense + Security, Baltimore, MD, USA, 5–9 May 2014; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9075, p. 90750F. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Guizani, M. Deep features learning for medical image analysis with convolutional autoencoder neural network. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2017, 7, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acree, M.A. Is there a gender difference in fingerprint ridge density? Forensic Sci. Int. 1999, 102, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudesh Gungadin, M. Sex determination from fingerprint ridge density. Internet J. Med. Update 2007, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shehu, Y.I.; Ruiz-Garcia, A.; Palade, V.; James, A. Detailed identification of fingerprints using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 December 2018; pp. 1161–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Yin, S. A Multi-channel Character Relationship Classification Model Based on Attention Mechanism. Int. J. Math. Sci. Comput. 2022, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, P.; Nithin Bharadwaj, B.P.; Pranav, M.S.; Koushik, S.; Koundinya, A.K. Myers-briggs Personality Prediction and Sentiment Analysis of Twitter using Machine Learning Classifiers and BERT. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Sci. 2021, 13, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.; Donkin, A.; Witten, I.H. WEKA: A machine learning workbench. In Proceedings of the ANZIIS’94-Australian New Zealnd Intelligent Information Systems Conference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 29 November 1994–2 December 1994; pp. 357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Koltun, V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07122. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).