Abstract

Ecuador, located in the Neotropics, has 66 protected natural areas, which represent about 13.77% of its overall territory. The Reserva Ecológica Arenillas reserve (REAr), located in southwestern Ecuador, protects an area of dry forest, coastal thorn forest, and mangroves. This dry forest is part of the Pacific equatorial core and is included the Tumbes–Chocó–Magdalena, one of the 34 biodiversity hot spots of the world. It is an extremely fragile ecosystem and therefore the need for conservation is of the utmost importance. Knowledge of the flora and their ecological characteristics is still limited, which was one of the main objectives of this work. In this study, 118 plots located in different locations of the REAr were selected in order to sample the trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants within them. This information was supplemented with data from the literature and the GBIF; life forms were included according to Raunkiaer’s classification and their growth habits. The flora of the REAr was represented by 381 species, belonging to 77 families. The two most numerous families were the Fabaceae (51 plant species) and Malvaceae (31 species). The dominant life form was the phanerophytes with 200 species (52.5%), followed by therophytes with 104 species (27.3%), and camephytes with 22 species (5.8%). Physiognomy was dominated by the herbaceous growth (44%). The biodiversity indices of two ecosystems were studied (The deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland and the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland), obtaining higher values for the deciduous forest ecosystem of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland. With these indicators, a classification of each forest type was made by performing a hierarchical cluster analysis. The information provided in this paper is particularly important for focusing conservation efforts and preventing the loss of flora diversity in these forests, which are subject to great anthropogenic pressures.

1. Introduction

Ecuador is one of the 17 mega-diverse countries of the world [1]. It has 17,748 confirmed species of native flora, and it is estimated that with the continuation of studies of Ecuadorian flora, the total number of vascular plants could reach 25,000 species [2]. A large proportion of these species (1600) are included in the IUCN Red List. Furthermore, more species are added to the Red List every year. In 2019, a total of 354 new species were included in the list.

Dry ecosystems are one of the most valuable types of ecosystems in Ecuador. Together with dry ecosystems of northern Peru they form the Tumbesian Region. This is one of the areas of South America with the greatest number of endemic species, while at the same time being one of the most threatened regions [3]. Among the different dry ecosystems in the Tumbesian region in Ecuador, the equatorial dry forest is among the most fragile [4]. This is a unique ecosystem of the world and is located in the south of the country, in the regions of Esmeraldas, Manabí, Santa Elena, Guayas, El Oro, and Loja.

One of the main remnants of the equatorial dry forest in the south of Ecuador is the Reserva Ecológica Arenillas reserve (henceforth REAr). Moreover, it is the only ecological reserve that conserves mangroves and tropical dry forests in the southwestern region of the country. In spite of its ecological relevance, the REAr presents conservation problems, such as the fragmentation of its ecosystems, the expansion of agriculture and cattle ranching inside the limits of the reserve, and several climate change-related impacts [5]. Another difficulty encountered by the REAr is the redefinition of its limits. It has been a military base and an exclusion zone since the 1970s because of its strategic location on the border with Peru [6]. Originally, the former military base had an area of 22,000 ha. When the Ecological Reserve was created in 2001, the protected area comprised only 17,082.7 ha of the original extent and in 2012, it was reduced to 13,170.03 ha. [7].

Since the creation of the natural reserve, the REAr has been studied very little from a floristic point of view. One of the first studies was that of Ceron et al. [8], in which 105 species belonging to 49 families were identified. These results were similar to those found by Estrella and Troya [9] (104 species grouped into 82 genera and 48 families) and Ochoa et al. [10] (79 species grouped into 69 genera and 41 families). Nevertheless, other studies that were based on higher sampling efforts have documented highly diverse flora [11], indicating that increasing the sampling effort may reveal much larger numbers. Based on these studies and other studies in different dry forest regions, it is also known that there are evident differences in the composition and biodiversity between the different zones of the REAr [12], but the factors that delimit this special differentiation in the dry forest have not yet been explored in great detail. Thus, it becomes difficult to study and obtain rigorous conclusions about the current lists of scientific data on the species that exist in this ecosystem.

Overall, the REAr, due to its history, diversity of habitats, geographic location, and sociological environment, is an interesting biodiversity scenario for the study of conservation, monitoring of plant species, and the improvement of our knowledge of the main functions of this ecosystem that is threatened by anthropic pressure. However, not much information exists about its floral composition, diversity, and the underlying drivers. Therefore, the objective of this work was to analyze the floristic composition, ecological characteristics, and diversity of the ecosystems within the REAr. By doing so, we updated the information on the flora of the REAr, increasing its value for conservation initiatives and contributing to a proper design of future management and conservation actions.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

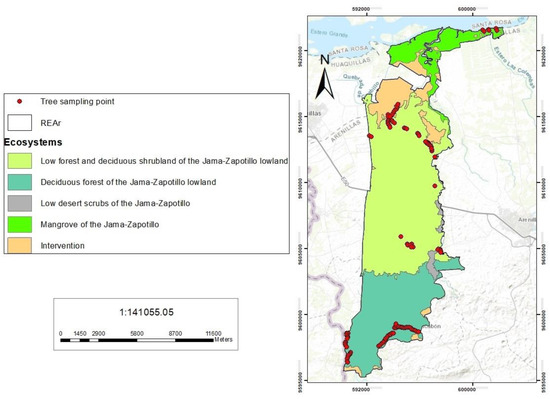

This study is conducted in the REAr, which is located to the south of the equator between the cantons of Huaquillas and Arenillas (Figure 1), within the latitudes from 3°27′30.94″ S to 3°39′37.49″ S and from 80° 9′18.65″ W to 80° 9′47.93″ W. This reserve has an area of 13,170 ha and an average elevation of 120 m above sea level (masl) [8]. The REAr is composed of a matrix of dry forests, desert scrubs, and mangroves. The climate of the study area is warm-dry, with an average temperature of 24 °C, and rainfall varies between 300 and 500 mm/year from the lower elevated northern area of the reserve to the higher elevated southern part.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the REAr, the ecosystems represented, and the selected sampling points.

2.2. Characterization of the Richness, Composition, and Diversity of Flora Species in the REAr

According to the ecosystem classification system of Ecuador [13], we can find four types of ecosystems in the study area: (1) The deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland, (2) the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland, (3) the mangrove of the Jama-Zapotillo, and (4) the low desert scrubs of the Jama-Zapotillo. In this study, we sampled 118 plots of 20 × 20 m surface areas in two of the different dry forest types (the low deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo and low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo) and in the mangrove (the mangrove of the Jama-Zapotillo) (Figure 1). Sampling locations were selected following a random design, but locations with difficult or impossible access were discarded. In each 20 × 20 m plot, four 5 × 5 m subplots were selected to study shrubs, and four 1 × 1 m subplots to study herbs. Life form classes were identified according to Raunkiaer’s classification [14]. Field sampling was carried out during the rainy season to achieve a better identification of the species, according to the flowering and fruiting times of most of the known species. The physiognomies of the plants (herbaceous, shrubs, and trees) were noted in the field during sampling. Each of the plots were georeferenced with a handheld GPS (GARMIN GPSMAP 65) with a 5 m horizontal accuracy. The list of flora of the REAr created by Molina Moreira in 2017 [11] was used as the basis for the study. This is the latest and most complete study conducted so far in the REAr, and included 291 species from 64 families. The specimens from this area that have already been deposited in the Reinaldo Espinoza Herbarium of the Universidad Nacional de Loja (LOJA), the Herbarium of the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (HUTPL), the Herbarium of the Universidad de Guayaquil (GUAY), and the Herbarium of the Universidad de Almería (HUAL) [15], were also studied.

A database was created with information on the species found in scientific literature and those detected during field sampling. This database was complemented with the records of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) [16] and Tropicos [17], and we used the information about the ecosystem type to locate where sampling plots or literature records were acquired according to the ecosystem classification system of continental Ecuador.

The nomenclature of the scientific names was based on Plants of the World Online, Kew Science (https://powo.science.kew.org/; last access on 15 August 2022), and the families were classified according to the APG IV classification system.

2.3. Data Analysis

Based on the field sampling records, we studied the plant diversity of the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland and the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland ecosystems. To achieve this, we selected the results of 110 plots (the remaining eight plots belonged to the mangrove ecosystem) and calculated species richness, abundance, and diversity. Species richness was calculated as the number of species present per plot. Abundance was calculated as the numbers of each individual species per plot. Two different diversity indices were used, Shannon’s index and Simpson’s index, according to Equations (1) and (2), respectively:

where H = Shannon’s index, D = Simpson’s diversity index, pi = Abundance of specie i (N) relative to the total number of species (N), and S = species richness [18].

With these indicators obtained at the plot level in the two sampled ecosystems, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using Sorensen’s distance measure [19,20]. The Ward method was then used to achieve the highest clustering structure coefficient. The analysis was performed using the Agnes function of the cluster ‘factoextra’ package in the R software, version 4.2.1. [21].

This analysis was performed at the plot level and for each of the two sampled ecosystems within the REAr (the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland and low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland), separately. Differences in the different indices between the classes obtained after hierarchical classification were tested by one-way ANOVA and HSD post hoc analyses using the ‘dplyr’ package of the R software version 4.2.1 [21]. The p-value was set to be <0.05.

We used the Ward method because of its strong grouping structure for our variables (abundance, richness, and diversity) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Agglomeration factors of the four clustering methods.

3. Results

In the REAr, 381 plant species belonging to 77 families were identified. Physiognomy was dominated by the herbaceous growth form, containing 167 plant species (44%), followed by 134 species of shrubs (35%) and 80 species of trees (21%). The three largest families were the Fabaceae with 51 plant species, followed by the Malvaceae with 31 species and the Euphorbiaceae with 26 species. The dominant life forms were phanerophytes with 200 species (52.5%), followed by therophytes with 104 species (27.3%), chamephytes with 22 species (5.8%), epiphytes with 21 species (5.5%), hemicryptophytes with 21 species (5.5%), geophytes with 7 species (1.8%) and hydrophytes with 6 species (1.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the list of vascular plants of the REAr, with their scientific name, family, growth habit, and life form, according to Raunkiaer’s classification (G, geophytes; H, hemicryptophytes; Hy, hydrophytes; P, phanerophytes; T, therophytes; E, epiphytes).

Forest Classification

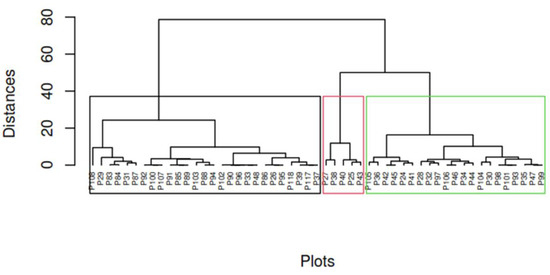

Based on the hierarchical grouping performed on the similarities of species richness, abundance, Shannon index, and Simpson index (Supplement S1 in Supplementary Material), we identified three dry forest types in the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowlands ecosystem. Type I (black line) contains 12 sample plots, type II (red line) contains 26 sample plots and type III (green line) contains 19 sample plots (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A dendrogram (Using the ward.D algorithm and Euclidean distance) of the grouping of the plots sampled in the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland ecosystem. The grouping of the plots into the three forest types, according to the calculated diversity indices, is illustrated.

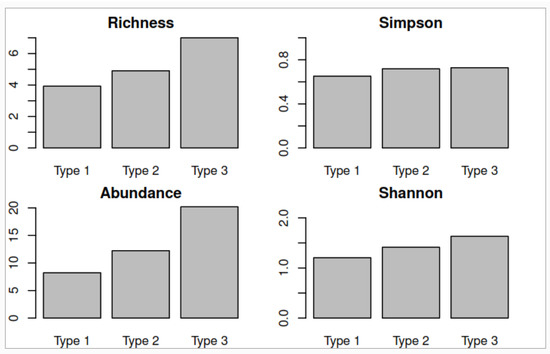

The mean values of the diversity indices showed significant differences between forest types I and III. Type I presented the highest species richness (6.16) and abundance (18.58). The type I forest was also the ecosystem with the highest values of the two different diversity indices, but no significant differences were found between this ecosystem and ecosystem type III. Forest type III had the lowest values of both diversity indices. The highest values of richness, abundance, and diversity that were found in forest type I (Figure 3) fits with the specific features that define a conserved forest, with some relevant species such as Handroanthus chrysanthus, Eriotheca ruizii, Bursera graveolens, and Ceiba trischistandra. The maximum height that was determined in this forest was 27 m, which was represented by the presence of the species Ceiba trischistandra.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the mean values of each diversity index in the three forest types determined in the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland ecosystem.

As similarly observed in the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland, the hierarchical grouping of the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland discriminated three forest types based on the similarity of the indicators: species richness, abundance, Shannon index, and Simpson index. Type I (black line) contains 27 plots, type II (red line) contains 5 plots and type III (green line) 21 plots. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A dendrogram (Using the ward.D algorithm and Euclidean distance) of the grouping of the plots sampled in the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland ecosystem of the REAr. The grouping of the plots into three forest types, according to the calculated diversity indices, is illustrated.

Significant differences in species richness (p-value = 1.27 × 10−6), abundance (p-value < 2 × 10−16), and Shannon index (p-value = 0.00712) were identified among the three forest types identified for this ecosystem. Forest type III had the highest species richness (7.00), abundance (20.20), alpha diversity with Simpson’s index (0.72), and Shannon index (1.63), which represent characteristics that define a well preserved forest (Figure 5). In type III, the following species stood out: Cochlospermum vitifolium, Handroanthus chrysanthus, Caesalpinia glabrata, and Geoffroea spinosa. The maximum height that was determined in this forest was 13 m.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the mean values in the three forest types of the low forest and deciduous shrubland of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland ecosystem.

4. Discussion

The detailed floristic analysis of our study reveals that, despite only focusing our sampling on two of the four ecosystems, [13], the richness and diversity of the species in this ecological reserve is greater than what was described in the last catalog of vascular flora detailing the complete sets of ecosystems included within the REAr [11]. The physiognomy of the species found in the study area was dominated by the herbaceous growth form with 167 species (44%). This is particularly interesting, as the tree species component in the tropical dry forests of the equatorial Pacific region is known, but knowledge of the shrubs and herbs is very limited. Nevertheless, seasonal dry forests have a very wide range of climatic tolerance [22], the predominance of herbaceous species over tree species may be due to the climatic conditions [23,24,25]. In the present study, all flora species were inventoried during the rainy season, corresponding with the onset of herbaceous flora.

Our findings are similar to those obtained in studies analyzing the floristic features of the dry forests of the central coastal Andes mountains that cover the Tumbesian region (58 forest families) [24] and other studies on Ecuador’s dry forests that report data on woody plant species [26,27]. Among all of the families, the Fabaceae was the most abundant, followed by the Malvaceae and Euphorbiaceae, and the dominant species in the reserve was the Handroanthus chrysanthus. These results are in accordance with previous studies reporting the Fabaceae as the best represented group in neotropical dry forests [28] and with specific studies in this region. For example, Molina [11] documented that the Fabaceae and Euphorbiaceae were the two predominant families in the REAr, and Luna et al. [12] cited the Fabaceae and Malvaceae as the most representative families. In 2006, Cerón et al. [8] reported that the Malvaceae and Poaceae were the most numerous families, with 8 species each, while the Fabaceae had 7 species.

Species assemblages in tropical dry forests appear to be primarily controlled by altitude and water availability [28], and the life forms reflect the bioclimate of the area. Raunkiaer [14] designed three main phytoclimates based on the landform spectrum, including phanerophyte for the tropics, therophyte for xeric environments, and hemicryptophyte for the cool temperate region. The present study identified seven different classes of life forms in the study area. As is the case in most dry forest remnants, our study reveals that the dominant life forms in the REAr were phanerophytes (52.5%) and terophytes (86%).

Many botanists have collected and studied the flora of Ecuador since the early 18th century [29,30,31,32]; the findings of our study highlight the importance of conserving the forests of the REAr and the species composition of the region. The analysis of species dominance and diversity within the REAr shows that 35% of the tree species identified are exclusive to the large floristic group of the Central Andes of the neotropical dry forest coast [24]. In the seasonal dry forests of Ecuador and Peru, 313 woody species can be found [33]. The presence of the Andes is one of the main causes of the isolation of the trans-Andean Pacific coastal region, which is characterized by the high levels of floristic endemism in the seasonal dry forests of Ecuador [33,34].

Many species are shared between dry forest formations and between the provinces of Ecuador [26]. In this study, we have observed that the species richness and diversity of REAr ecosystems depend on the dominant ecosystem type. Herbaceous species abundance and Shannon type diversity were higher in the deciduous forest of the Jama-Zapotillo lowland. The dominant families by number of species, density, abundance, and dominance of individuals are: the Fabaceae, Mimosaceae, Moraceae, and Bombacaceae [35,36]. The species composition analysis of this dry forest was dominated by species such as Handroanthus chrysanthus and revealed a general pattern of variation in community diversity and species composition. Several authors [26,34,37] have reported similar composition patterns of this species in the dry forests of the same region. The dendrograms divide the ecosystems studied into three types that differ in richness, abundance, and diversity. This seems to be related to the anthropic pressures exerted, with the least rich and diverse areas being the most degraded near the border, roads, or agricultural environments.

The information provided in this study is especially relevant due to the fragility of the tropical dry forest, which is the main ecosystem within the REAr and is the ecosystem where our specific data collection has been performed. Indeed, the tropical dry forest is one of the most threatened biomes in the world [26,38] and has experienced one of the most extensive rates of habitat loss during the last few decades [38]. Be that as it may, it is a much less-studied ecosystem than other tropical ecosystems, such as rainforests [6]. The small extension and high fragmentation of the Ecuadorian dry forests makes them more sensitive than those which are located in other countries [39]; this situation is especially relevant in the REAr. Despite being classified as a natural reserve, the highest protection level in Ecuador, it is a vulnerable area due to the constant pressure of extracting resources and expanding the agricultural and ranching areas within the REAr limits. In addition, clandestine crossings by outsiders and the deforestation of trees to create new access routes occur in this border area. These activities exert a strong negative impact on the vegetation. Further studies are needed on the biodiversity of the REAr and the relationships within the ecosystems and external pressures. Furthermore, transdisciplinary initiatives that take into account the ecological and human dimensions are a priority for safeguarding the integrity of the REAr [40,41] along with similar regions. Strategies can be implemented in this manner to reduce the negative impacts on these regions and provide alternative livelihoods for local communities. This would allow for the sustainable use and conservation of the REAr’s invaluable biodiversity for future generations, as well as its associated ecosystem services [42,43,44].

5. Conclusions

The present study reveals that the REAr has a greater floristic diversity than has previously been described. These new data are beneficial for the protection and conservation of this region.

The predominant life forms are phanerophytes and terophytes, which are conditioned by the presence of dry tropical climate in deciduous forests.

Within the dry forest zone, there is a great variety of forest types with different levels of richness, possibly because of differences in the level anthropogenic pressure between zones (i.e., greater impacts and more degraded areas with less richness are on the edges of the reserve, the areas closest to access roads or agricultural zones).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app12178656/s1, Supplement S1: Ecosystem type and biodiversity and richness values of all field plots.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.D.L.-F., D.A.N.-N., E.R.-C., J.L.M.-P. and E.G.-L.; validation, formal analysis and investigation: D.A.N.-N. and A.D.L.-F.; resources: E.G.-L.; writing: A.D.L.-F.; visualization: A.D.L.-F., E.G.-L., E.R.-C., J.L.M.-P. and D.A.N.-N.; supervision: E.G.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the park rangers and the person in charge of the REAr, who are the direct actors in the control and care of this protected area attached to the National System of Protected Areas, part of the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition of Ecuador; through the approved research permit No. 005-2018-IC-FLO/FAU-DPAEO-MAE, it was possible to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mittermeier, R. Megadiversidad: Los Países Biológicamente Más Ricos Del Mundo; PEMEX: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997; ISBN 968-6397-49-3. [Google Scholar]

- Neill, D.A. ¿Cuantas especies nativas de plantas vasculares hay en Ecuador? Rev. Amaz. Cienc. Tecnol. 2012, 1, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, M.A.; Freire, J.F. Biodiversidad En Los Bosques Secos de La Zona de Cerro Negro-Cazaderos, Occidente de La Provincia de Loja: Un Reporte de Las Evaluaciones Ecológicas y Socioeconómicas Rápidas; EcoCiencia: Quito, Ecuador, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Palomino, R.; Kvist, L.P.; Aguirre-Mendoza, Z.; Gonzales-Inca, C. Diversity and Endemism of Woody Plant Species in the Equatorial Pacific Seasonally Dry Forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 19, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Moreira, M.N.; Valencia Chacón, N.; Pérez Flor, J.; Lavayen Tamayo, J. Composición Florística y Nuevos Registros Para La Reserva Ecológica Arenillas, El Oro-Ecuador. Investigatio 2016, 8, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Avila, G.; Cervera, L.; Ordóñez-Delgado, L.; Jara-Guerrero, A.; Amador, L.; Paladines, B.; Briceño, J.; Peréz-Jiménez, V.; Lizcano, D.; Duncan, D.; et al. Biodiversity Patterns and Ecological Processes in Neotropical Dry Forest: The Need to Connect Research and Management for Long-Term Conservation. Neotrop. Biodivers. 2017, 3, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019-1. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Cerón, C.; Reyes, C.; Vela, C. Características Botánicas de La Reserva Militar y Ecológica Arenillas, El Oro-Ecuador. Cinchonia 2006, 7, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.A.E.; Costa, S.M.T. Estudio etnobotánico en la Reserva Ecológica Militar Arenillas, Provincia de El Oro; Universidad Nacional de Loja: Loja, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, D.; Valle, D.; Ordóñez-Delgado, L. Plan de Manejo de La Reserva Ecológica Militar Arenillas (REMA); Conservación Internacional: Loja, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Moreira, M.N. Biodversidad y Zonación de Los Ecosistemas de La Reserva Ecológica Arenillas-Ecuador; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Luna Florin, A.D.; Sánchez Asanza, H.W.; Maza Maza, J.E.; Castillo Figueroa, J.E. Índices de Diversidad Florística Forestal En La Reserva Ecológica Arenillas. Agroecosistemas 2022, 10, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. Sistema de Clasificación de Los Ecosistemas Del Ecuador Continental; Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, C. Las Formas de Vida de Las Plantas y La Geografía Estadística de Las Plantas: Siendo Los Papeles Recopilados de C. Raunkiaer; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- NYBG. Index Herbariorum. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- GBIF. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Tropicos. Available online: https://tropicos.org/home (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Magurran, A.E. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; ISBN 978-94-015-7358-0. [Google Scholar]

- Beals, E.W. Bray-Curtis Ordination: An Effective Strategy for Analysis of Multivariate Ecological Data. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1984, 14, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- McCune, B.; Beals, E.W. History of the Development of Bray-Curtis Ordination; Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters: Madison, WI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Miles, L.; Newton, A.C.; DeFries, R.S.; Ravilious, C.; May, I.; Blyth, S.; Kapos, V.; Gordon, J.E. A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forest.s. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.G.; Lugo, A.E. Dry Forests of Central America and the Caribbean; Bullock, S.H., Mooney, H.A., Medina, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, T. Plant Diversity Patterns in Neotropical Dry Forests and Their Conservation Implications. Science 2016, 353, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cervigón, A.I.; Camarero, J.J.; Cueva, E.; Espinosa, C.I.; Escudero, A. Climate Seasonality and Tree Growth Strategies in a Tropical Dry Forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2019, 31, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Mendoza, Z.; Kvist, L.P.; Sánchez, T.O. Bosques Secos En Ecuador y Su Diversidad. In Botanica Economica De Los Andes Centrales; Moraes, M., Øllgaard, R.B., Kvist, L.P., Borchsenius, F., Balslev, H., Eds.; Universidad Mayor de San Andrés: La Paz, Bolivia, 2006; pp. 162–187. [Google Scholar]

- Luna Florin, A.D.; Sánchez Asanza, A.W.; Maza Maza, J.E.; Castillo Figueroa, J.E. Biomasa Forestal y Cáptura de Carbono En El Bosque Seco de La Reserva Ecológica Arenillas. Agroecosistemas 2021, 9, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, C.I.; Cabrera, O.; Luzuriaga, A.L.; Escudero, A. What Factors Affect Diversity and Species Composition of Endangered Tumbesian Dry Forests in Southern Ecuador? bioTROPICA 2011, 43, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire Fierro, A. Botánica Sistemática Ecuatoriana; Missouri Botanical Garden Press ix: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2004; ISBN 9978-43-481-X. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, P.M.; León-Yánez, S. Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, L.; Navarrete, H.; Muriel, M.P.; Macía, M.J.; Balslev, H. Enciclopedia de de Las Plantas Útiles Del Ecuador; Herbario QCA de la Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador; Herbario AAU del Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad de Aarhus: Aarhus, Denmark, 2008; ISBN 978-9978-77-135-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, P.M.; Ulloa, C.; Maldonado, C. Riqueza de Plantas Vasculares. In Botanica Economica De Los Andes Centrales; Moraes, M., Øllgaard, R.B., Kvist, L.P., Borchsenius, F., Balslev, H., Eds.; Universidad Mayor de San Andrés: La Paz, Bolivia; pp. 37–50.

- Davis, S.D.; Heywood, S.H.; Herrer-MacBryde, O.; Villa-Lobos, J.; Hamilton, A. Centres of Plant Diversity: A Guide and Strategy for Their Conservation; IUCN Publications Unit: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Mendoza, Z.; Kvist, L.P. Compisición Florística y Estado de Conservación de Los Bosques Secos Del Sur-Occidente Del Ecuador. Lyonia 2005, 8, 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, T.; Aguirre-Mendoza, Z. Vegetación de Los Bosques Secos de Cazaderos-Mangaurco, Occidente de La Provincia de Loja; EcoCiencia: Quito, Ecuador, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, O.; Aguirre-Mendoza, Z.; Quispe, W.; Alvarado, R. Estado Actual de Conservación de Los Bosques Secos Del Sur-Occidente Ecuatoriano.; Aguirre, Z., Ed.; Editorial ABYA: Loja, Ecuador, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yaguana Puglla, C.; Aguirre-Mendoza, Z. Riqueza Florística Del Centro de Investigación El Chilco Región Tumbesina, Ecuador. Bosques Latid. Cero 2014, 4, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, J.M.; Boucher, T.M.; Ricketts, T.H.; Roberts, C. Confronting a Biome Crisis: Global Disparities of Habitat Loss and Protection. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo-Quintero, C.A.; Sánchez-Azofeifa, G.A. Extent and Conservation of Ropical Dry Forests in the Americas. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Azofeifa, G.A.; Quesada, M.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Nassar, J.M.; Stoner, K.E.; Castillo, A.; Garvin, T.; Zent, E.L.; Calvo-Alvarado, J.C.; Kalacska, M.E.; et al. Research Priorities for Neotropical Dry Forests. Biotropica 2005, 37, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Yánez, P. Las Áreas Naturales Protegidas Del Ecuador: Características y Problemática General. Qualitas 2016, 11, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.G.; Lugo, A.E. Ecology of Tropical Dry Forest. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1986, 17, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Macías, C.A.; Alegre Orihuela, J.C.; Iglesias Abad, S. Estimation of Above-Ground Live Biomass and Carbon Stocks in Different Plant Formations and in the Soil of Dry Forests of the Ecuadorian Coast. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, e00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijas, S.; Romero-Duque, L.P.; Trilleras, J.M.; Conti, G.; Kolb, M.; Brignone, E.; Dellafiore, C. Linking Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, and Beneficiaries of Tropical Dry Forests of Latin America: Review and New Perspectives. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 36, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).