Abstract

This paper considers the problem of assigning nonpreemptive jobs on identical parallel machines to optimize workload balancing criteria. Since workload balancing is an important practical issue for services and production systems to ensure an efficient use of resources, different measures of performance have been considered in the scheduling literature to characterize this problem: maximum completion time, difference between maximum and minimum completion times and the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations. In this study, we propose a theoretical and computational analysis of these criteria. First, we prove that these criteria are equivalent in the case of identical jobs and in some particular cases. Then, we study the general version of the problem using jobs requiring different processing times and establish the theoretical relationship between the aforementioned criteria. Based on these theoretical developments, we propose new mathematical formulations to provide optimal solutions to some unsolved instances in order to enhance the latest benchmark presented in the literature.

1. Introduction

Balancing workload among a set of resources or operators is an important issue in many services and production environments. For instance, in the manufacturing industry, balancing the workload among machines can reduce idle time. It also helps to manage bottlenecks in many production systems. This problem can be formally defined as the assignment of a set of jobs to identical parallel machines (or other types of resources) with the objective of balancing the total workload among those machines as equally as possible. Recently, this scheduling problem has found application in the Fog Computing empowered Internet of Things (IoT) [1]. This study proposes that a workload balancing scheme may reduce the latency of data flow, which is a key performance metric for IoT applications. In addition, workload balancing criteria have gained a lot of attention in key concepts of scheduling in Industry 4.0, such as of Flexible Manufacturing System [2] and Smart Manufacturing System [3]. Balancing the workload among a set of machines or human workers is also an important issue in many practical cases. For instance, assigning human resources is an important concern for many industries and organizations like hospitals, manufacturing firms, transportation companies, etc. Cuesta et al. [4] addressed a human resources assignment problem with the objectives of maximizing employee satisfaction and production rate on a real world case of a large production firm. Azmat et al. [5] presented different MIP models to solve workforce scheduling problems for a single-shift, taking into consideration constraints relative to labor regulations. Khouja and Conrad [6] addressed on a balancing problem encountered by a mail order firm. To handle order taking and billing, and to ease order tracking, customer groups should be assigned almost equally to the employees.

Many researchers, especially in the scheduling community, are interested in the workload balancing problem. They have addressed this problem in different ways: as a series of constraints or as an objective function. For example, Schwerdfeger and Walter [7] proposed an approached optimization method based on heuristics and a genetic algorithm in order to deal with semirelated parallel machines under sequence-dependent setups and load balancing constraints. Ouazene et al. [8] introduced a mixed integer-programming model and a genetic algorithm to minimize total tardiness and workload imbalance in a parallel machine-scheduling environment. In 2012, Keskinturk et al. [9] attempted to minimize the relative workload imbalance on parallel machines via two metaheuristic methods.

Cossari et al. [10] noted that there is no established performance measure in the literature to characterize the workload balancing problem. However, different criteria have been proposed in the literature. The first is the relative percentage of imbalances (RPI) introduced by Rajakumar et al. [11,12]. However, Walter and Lawrinenko [13] showed that this criterion is equivalent to maximum completion time minimization and does not provide perfectly balanced schedule.

Ho et al. [14] introduced a new workload balancing criterion, the so-called Normalized Sum of Squared Workload Deviations (NSSWD). They also analyzed some properties of the problem and introduced a heuristic algorithm to solve it. Later, Ouazene et al. [15] showed that the criterion is equivalent to . In other words, represents a normalized variant of the problem of minimizing This problem was first treated by Chandra and Wong [16] in 1975, who analyzed the worst-case performance of Longest Processing Times rule, and derived its worst-case performance ratio, i.e., .

Ho et al. [14] also stated that, in the case of identical parallel machines, a -optimal schedule is necessarily a -optimal schedule as well. However, [13] provided a counter-example for the case with more than two machines to prove that this result was wrong. They also carried out a computational study to give an overview on as well as optimal schedules and empirically analyzed the correlation between both criteria. The numerical results revealed that the criterion may be a good approximation for when the ratio is rather small. However, for some other instances, especially the largest ones, the -optimal solution is not a good candidate solution for workload balancing.

Ouazene et al. [15] also recommended the minimization of the difference between the most and least loaded machine () as a measure for workload balancing on identical parallel machines. They performed a computational study to show that, in general, a makespan optimal schedule is not optimal for criterion.

One of the recent works dealing with this problem is that of Schwerdfeger and Walter [17]. The authors investigated the workload balancing problem on a parallel machines environment where the objective was to minimize the normalized sum of square for workload deviations. They proposed an exact subset sum-based algorithm to solve a three-machine case. In a follow-up paper, Schwerdfeger and R. Walter [18] provided a dynamic programming approach to solve the same problem. They also suggested two local search procedures to solve large instances and provided a complete and dedicated benchmark to the workload balancing problem.

This paper consists of a theoretical and computational analysis of the different criteria addressed in the literature to deal the workload balancing problem. More specifically, it aims to investigate the theoretical relationships between and problems. As mentioned by Cossari et al. [10], while workload balancing is an important practical criterion given the need of production systems to efficiently use all of their resources, there is no established measure of performance in the scheduling literature that characterizes total workload balance. Different criteria have been addressed in the literature and some of them are trivial. That is why we present in this work a rigorous theoretical analysis of the most important criteria that have been considered for this problem. The main theoretical contribution of this paper is to establish the exact mathematical relationship between NSSWD and () as a measure for the workload balancing on identical parallel machines. Then, based on this theoretical analysis, new mathematical bounds are developed and incorporated into mathematical programming models to provide a number of optimal solutions to some unsolved instances in the benchmark proposed by Schwerdfeger and R. Walter [18].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section introduces the problem considered in this study with the different notations. Section 3 presents the workload balancing problem using two cases: the case of identical jobs and the general case with jobs having different processing times. Section 4 introduces three mathematical formulations to the problem. Numerical tests are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the contribution of this paper.

2. Problem Description

2.1. Preliminary Notations and Assumptions

The problem considered in this paper is described as follows: a set of independent jobs are to be scheduled on parallel machines. All machines or resources are identical, i.e., job requires the same processing time on any machine. Each machine can process at most one job at a time, and each job must be processed without interruption by one of the machines. All the jobs are assumed to be available at time zero and each job has a deterministic integer processing time . The setup times, if any, are included in the processing time.

To avoid trivialities, it is assumed that: .

A schedule is represented by an -partition of the set jobs , where each , represents the subset of jobs assigned to the machine . The objective is to minimize the workload imbalance between the different machines.

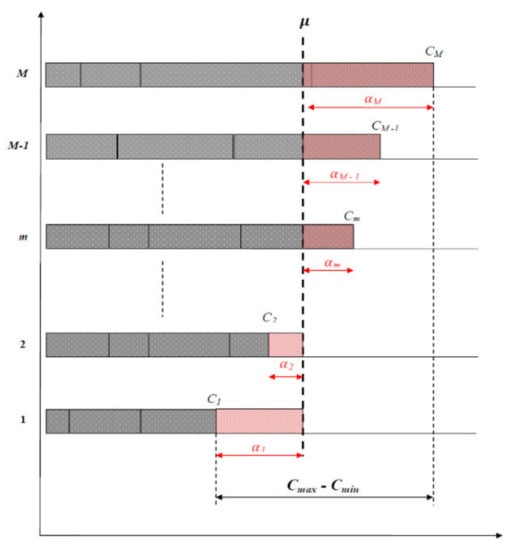

Since the machines are identical, we can assume, without loss of generality, that the indexes of the machine are rearranged in nondecreasing order according to the completion times (or workloads) as illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the workload imbalance on identical parallel machines.

The different notations used in this paper are described below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nomenclature.

2.2. Performance Criteria for Workload Balancing

In the case of identical parallel machines, a well-established criterion is the normalized sum of squared workload deviations (). This criterion was introduced by Ho et al. [14]; it is based on the sum of squares principle known in measuring variability in statistics and serves as a precise measurement criterion. is defined as follows.

where:

The authors discussed some properties of the criterion and tackled the complexity of the problem. They also showed that a non makespan-optimal schedule can be improved in terms of by reducing its maximum machine completion time.

Cossari et al. [19] showed that: , where is the standard deviation and is the coefficient of variation.

Hence, the authors concluded that the criterion is equivalent to the coefficient of variation and both two criteria may be used as performance measures.

In the particular case of identical parallel machines, is equivalent to (cf. [15,17]). It makes no difference whether we minimize or .

3. Theoretical Analysis of Different Criteria

3.1. Case with Identical Jobs

This section introduces some of the properties of the different workload balancing performance measures and establishes equivalence between the following problems: , and .

Proposition 1.

If any schedule of a parallel machines problem withidentical jobs andmachines, the problems,andare equivalent and trivial.

Proof of Proposition 1.

In any schedule of a parallel machines problem with identical jobs and machines, there is a set of machines () which have the same workload load and other machines which must have the same workload , where .

We consider that all jobs have the same processing time: , then we obtain the following cases.

Case 1:

Then, the different workload measures can be expressed as follows.

Case 2:

Then, the different workload measures can be expressed as follows.

Concerning the calculation, let us consider: . Then, the average workload can be written as follows: . The average workload can be also expressed as: .

So, based on the -criterion definition, we have:

Considering that , the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations can be expressed as follows:

Based on the demonstration detailed above, we can also conclude that in any parallel machine scheduling problem with identical jobs and machines, the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations -criterion is constant and completely independent of the job processing times (rather, it depends only on the number of jobs and the number of machines). □

3.2. Case with Different Blocks of Identical Jobs

We assume the particular case in which the jobs can be partitioned into sets such as the jobs owned the same set have the same processing time: and .

Lemma 1.

Considering the assumptions mentioned above and if we have, then the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviationsis equal to zero.

Proof of Lemma 1.

This proof is based on the preliminary results established in Proposition 1.

Finally, since all the machines have the same workload value, then the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations (NSSWD) is equal to zero. □

Proposition 2

Under the assumptions assumed above and if we haveand, then the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviationsis constant.

Proof of Proposition 2.

In the optimal schedule, there is a set of machines which have the same workload load and other machines which must have the same workload .

Let us consider: . Then, the average workload can be written as follows: . It can be also expressed as: .

So, based on the NSSWD-criterion definition, we have:

Considering that , the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations can be expressed as follows:

□

3.3. General Case with Different Jobs

In this section, we consider the workload balancing problem in its general version. The jobs may have different processing times.

A strong correlation between the two criteria and was suspected by different authors in the literature [13,14,19]. However, their different analyses were based on empirical study. As a major contribution of our paper, we establish the exact mathematical correlation between these two criteria.

3.4. Case with Two Machines

Proposition 3.

In the case of two parallel machines, the problems, andare equivalent.

Proof of Proposition 3.

First, we establish that a -optimal solution is also -optimal one. As a preliminary result, we assume the well-established relationship: .

Considering this relationship and the definition of the maximum completion time, we can write:

Since is constant and , it is clear that minimizing implies the minimization of the difference .

Then, we establish that a -optimal solution is also ()-optimal. Based on the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations definition, we can write:

Since is constant, minimizing () implies the minimization of . □

3.5. Case with More Than Two Machines

Proposition 4.

The normalized sum of the square for Workload Deviations criterioncan be bounded as follows:.

Proof of Proposition 4.

As first step, we deal with the upper bound.

Before dealing with the demonstration, we remind the reader of the following result (see [20] for details) concerning the maximum value of the standard deviation measure. It is shown that if , then the maximum possible value of standard deviation occurs when half of the values are equal ta and half of them are equal to . That means:

Based on the proposition cited above, we can establish that:

The second step of demonstration deals with the lower bound.

Or by considering the relationship: , we can conclude that:

□

Remark 1.

In the case of,andcriteria are linearly dependent. This confirms the equivalence between theandproblems established in the previous section. This relationship is given below.

Remark 2.

Based on Proposition 3, we can introduceas a new criterion to deal with the workload imbalance minimization in an identical parallel machine problem. This criterion presents the advantage of being bounded, and these bounds depend on the configuration of the instance (number of machines and sum of processing times).

We can also notice an important asymptotic behavior of this criterion. In fact, for a fixed number of machines , the criterion decreases according to the sum of processing times and we have a perfect balanced solution when .

4. Mathematical Formulations

In this section, we introduce three formulation of the problem, namely mixed-integer quadratic programming (MIQ1), mixed-integer quadratic programming with linear cuts (MIQ2) and mixed-integer linear programming (MILP).

4.1. Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming (MIQ1)

This formulation was first introduced by [17] to deal with the problem P|| NSSWD. This formulation considers binary variables , which take the value 1 if job is assigned to machine and 0 otherwise. Equation (19) describes the objective function expressed as a quadratic function. Constraints (20) ensure that each job is assigned to exactly one machine. The machine completion times are determined by Equation (21). Finally, the domains of the binary variables are defined by Equation (22).

Subject to

The following two formulation represent a new contribution based on the theoretical analysis developed in Section 3. First, we incorporate the new bounds, established by Proposition 4, as new cats in the mixed-integer quadratic programming (MIQ1) proposed by [17] in order to reduce the solution space. Then, based on the same development we introduce a new mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) to solve the problem.

4.2. Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming with Cuts (MIQ2)

This second formulation considers the same binary variables , which take the value 1 if job is assigned to machine and 0 otherwise. Equation (23) describes the objective function. Constraints (25) ensure that each job is assigned to exactly one machine. The machine completion times are determined by Equation (25). Constraints (26) and (27) define respectively the workload of the least and most loaded machine. Constraints (28) and (29) introduce the theoretical bounds established by Proposition 4 as new cats in the original model. Finally, the domains of the binary variables are defined by Equation (31).

Subject to

4.3. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP)

This third formulation addressed a linear version of the mixed integer programming model. It also considers the same binary assignment variables , which take a value of 1 if job is assigned to machine and 0 otherwise. Equation (32) describes the objective function represented by the variable . Constraints (33) and (34) define respectively the workload of the least and most loaded machine. Constraints (35) and (36) introduce the theoretical bounds established by Proposition 4 as new cats in the original model. Constraints (37) ensure that each job is assigned to exactly one machine. Finally, the domains of the binary variables are defined by Equations (38) and (39).

Subject to

5. Computational Analysis

The objective of this computational study is to analyze the performance of three formulations, namely MILP, MIQ1 and MIQ2 under the same datasets used by Schwerdfeger and Walter [18]. Concretely, we would like to gauge the impact of the linearization to the solving of linear model. In addition, the numerical analysis would track the differences made by introducing the linear cuts onto the quadratic formulation.

5.1. Benchmarks

To conduct numerical tests, we used two datasets introduced by Schwerdfeger and Walter [18], namely HGJ and DM. The HGJ dataset was generated by [21], and includes instances with the number of jobs varying from to and the number of machines from to . For each couple (number of jobs, number of machines), Haouari et al. [21] generated 20 instances. The DM dataset was generated by Dell’Amico and Martello [22] with 1900 instances. The number of jobs was generated from 10 to 10000 and the number of machines from 3 to 15. Fifty instances are generated for each couple. The reader may refer to [18] for details regarding the generation of the datasets.

We use the solver ILOG IBM CPLEX 12.5, executed on an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5120 CPU @ 2.20 GHz, with 92 GB of RAM. The solving time limit was fixed to 300 s. For each problem size, we recorded the number of instances that had been solved to optimality and the average/maximum/minimum solving time.

5.2. Results

Performance criteria: The performance of each model is based on computational performance of the solver to reach optimal solutions. The indicators are, amongst the instances with the same size :

- max time: maximal solving time.

- min time: minimal solving time.

- avg time: average solving time.

- opt: number of instances which are solved to optimality within the solving time limit fixed to 300 s.

5.2.1. Dataset DM

Table 2 lists the numerical results from solving the DM dataset by using three models (MIL, MIQ1 and MIQ2). With the linear model MIL, CPLEX solved 500 out of 1900 to optimality, i.e., 26%. The quadratic model MIQ1 yields 1269 instances solved 67% to optimality. With linear cuts, the number of opt for MIQ2 is 717, which is 38% of the total instances. The best average solving times of CPLEX was given by MIQ1, followed by MIQ2 and lastly MILP. While combining the solutions found by all the models, we increased the number of instances solved optimally to 1370, which is 72% out of 1900 instances. For this dataset, [18] found 945 optimal solutions by solving the quadratic model by Solver Gurobi.

Table 2.

Numerical results from DM Dataset.

Solving difficult instances of DM dataset (10, 25), (15, 25) and (15, 50): While the MIQ1 had the best performance overall, it encountered difficulties when dealing with the difficult-to-solve instances: (10, 25), (15, 25) and (15, 50). The same phenomenon was also frequently observed in the literature, especially in the most recent work of [18]. Schwerdfeger and Walter [18] did not find an optimal solution for all of the mentioned combinations. Interestingly, the linear formulation performed very well in those combinations: 44 (88%) instances solved to optimality for the problem size of (10, 25), and 32 (64%) instances solved to optimality for the problem size of (15, 25). The configuration (15, 50) remains problematic for our three models.

5.2.2. Dataset HGJ

Table 3 lists the numerical results from solving the HGJ dataset using three models (MILP, MIQ1 and MIQ2). For this dataset, the gap of the performance between the three models is slightly smaller than that of the DM dataset. Accordingly, out of 560 instances, the percentage of instances solved optimally was 52% for MILP, 55% for MIQ1 and 51% for MIQ2. Altogether, 389 out of 560 instances were solved optimally, which is equivalent to 61%. Again, in the configuration whereby one model has some difficulties in finding a solution, the others can solve those instances more easily. For this dataset, the authors of [18] found 37 optimal solutions by solving the quadratic model by Gurobi and 45 optimal solutions using a local search.

Table 3.

Numerical results from the HGJ Dataset.

Solving difficult instance of HGJ dataset (15, 20): we observed the same phenomenon in the DM dataset. In configuration (15, 20), the authors of [18] did not find an optimal solution; the quadratic model MIQ1 does not yield any optimal solution either. However, with a linear cut, MILP and MIQ2 found 20 optimal solutions out of 20 instances.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Workload balancing problems among a set of identical machines or resources is a challenge in many organizations and production systems. Different criteria have been addressed in the literature as performance measures to tackle this problem. The minimization of the difference between the most and least loaded machine () and the Normalized Sum of Square for Workload Deviations () are the most important and well-established ones. To the best of our knowledge, the most important works addressed in the literature have considered empirical approaches to analyze this problem.

In this paper, we proposed a rigorous theoretical analysis of the workload balancing problem on identical parallel machines and established the mathematical correlation between the two problems: and .

Based on these new theoretical proprieties, three mathematical formulations were tested using the latest benchmark described in the literature. The combination of these three models allowed us to provide optimal solutions for some unsolved instances in this benchmark.

Recently, Asadollahi-Yazdi et al. [23] discussed the concept of Industry 4.0 and its effect on the industrial world and global society. This study provided a comprehensive overview of industrial revolutions, manufacturing production plans over time, as well as a detailed analysis of Industry 4.0 and its features. One of the important concerns addressed in this paper was the necessity of integrating human factors into existing scheduling techniques and information systems in the production control of real factories. Workload balancing was identified as one of these criteria with which to assess and measure the balance or “equity” of workload assignments. We see an interesting direction for future research, which consists of generalizing the obtained results to establish a performance measure of workload equity in different, real cases, taking into account the perspective of the industry of the future.

Author Contributions

Y.O., N.-Q.N. and F.Y. contributed equally to the different steps of this research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Industrial Chair Connected-Innovation and the FEDER (Le Fonds Européen de Développement Régional).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data have been presented in the manuscript. The codes developed for the current study are available from the corresponding author if requested.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Industrial Chair Connected-Innovation and its industrial partners (https://chaire-connected-innovation.fr (accessed on 1 February 2021)), as well as FEDER (Le Fonds Européen de Développement Régional) for their financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, Q.; Ansari, N. Towards Workload Balancing in Fog Computing Empowered IoT. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, A.; Barabas, S.A. Modeling and Simulation of a Flexible Manufacturing System—A Basic Component of Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, C. A big data enabled load-balancing control for smart manufacturing of Industry 4.0. Cluster Comput. 2017, 20, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Cuesta, S.; Diego-Mas, J.A.; Canós-Darós, L.; Andrés-Romano, C. A genetic algorithm for the design of job rotation schedules considering ergonomic and competence criteria. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 60, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, C.S.; Hürlimann, T.; Widmer, M. Mixed integer programming to schedule a single-shift workforce under annualized hours. Ann. Oper. Res. 2004, 128, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouja, M.; Conrad, R. Balancing the assignment of customer groups among employees: Zero-one goal programming and heuristic approaches. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1995, 15, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.B.; Duman, E.; Krishnan, K.; Senniappan, K. Parallel machine scheduling with load balancing and sequence dependent setups. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ouazene, Y.; Hnaien, F.; Yalaoui, F.; Amodeo, L. The Joint Load Balancing and Parallel Machine Scheduling Problem. In Operations Research Proceedings 2010; Hu, B., Morasch, K., Pickl, S., Siegle, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Keskinturk, T.; Yildirim, M.B.; Barut, M. An ant colony optimization algorithm for load balancing in parallel machines with sequence-dependent setup times. Comput. Oper. Res. 2012, 39, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossari, A.; Hob, J.C.; Paletta, G.; Ruiz-Torres, A.J. Minimizing workload balancing criteria on identical parallel machines. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2013, 30, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, S.; Arunachalam, V.P.; Selladurai, V. Workflow balancing strategies in parallel machine scheduling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2004, 23, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, S.; Arunachalam, V.P.; Selladurai, V. Workflow balancing in parallel machines through genetic algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 33, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.; Lawrinenko, A. A note on minimizing the normalized sum of squared workload deviations on m parallel processors. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 75, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Tseng, T.L.; Ruiz-Torres, A.J.; López, F.J. Minimizing the normalized sum of square for workload deviations on m parallel processors. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 56, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouazene, Y.; Yalaoui, F.; Chehade, H.; Yalaoui, A. Workload balancing in identical parallel machine scheduling using a mathematical programming method. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2014, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.K.; Wong, C.K. Worst-Case Analysis of a Placement Algorithm Related to Storage Allocation. SIAM J. Comput. 1975, 4, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdfeger, S.; Walter, R. A fast and effective subset sum based improvement procedure for workload balancing on identical parallel machines. Comput. Oper. Res. 2016, 73, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdfeger, S.; Walter, R. Improved algorithms to minimize workload balancing criteria on identical parallel machines. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 93, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossari, A.; Ho, J.C.; Paletta, G.; Ruiz-Torres, A.J. A new heuristic for workload balancing on identical parallel machines and a statistical perspective on the workload balancing criteria. Comput. Oper. Res. 2012, 39, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.F.; Yousif, A.E. Properties of the standard deviation that are rarely mentioned in classrooms. Austrian J. Stat. 2009, 38, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haouari, M.; Gharbi, A.; Jemmali, M. Tight bounds for the identical parallel machine scheduling problem. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2006, 13, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Amico, M.; Martello, S. Optimal Scheduling of Tasks on Identical Parallel Processors. ORSA J. Comput. 1995, 7, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi-Yazdi, E.; Couzon, P.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Ouazene, Y.; Yalaoui, F. Industry 4.0: Revolution or Evolution? Am. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 10, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).