Abstract

Due to the fractal nature of retinal blood vessels, the retinal fractal dimension is a natural parameter for researchers to explore and has garnered interest as a potential diagnostic tool. This review aims to summarize the current scientific evidence regarding the relationship between fractal dimension and retinal pathology and thus assess the clinical value of retinal fractal dimension. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a literature search for research articles was conducted in several internet databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus). This led to a result of 28 studies included in the final review, which were analyzed via meta-analysis to determine whether the fractal dimension changes significantly in retinal disease versus normal individuals. From the meta-analysis, summary effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were derived for each disease category. The results for diabetic retinopathy and myopia suggest decreased retinal fractal dimension for those pathologies with the association for other diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and glaucoma remaining uncertain. Due to heterogeneity in imaging/fractal analysis setups used between studies, it is recommended that standardized retinal fractal analysis procedures be implemented in order to facilitate future meta-analyses.

Keywords:

fractal dimension; retina; vascular network; pathology; biomarker; ophthalmology; vision; biophysics 1. Introduction

1.1. Retinal Vasculature and Fractal Dimension

The retina is of crucial importance to eye care professionals as retinal diseases are the leading cause of blindness worldwide. The retina is a thin, light-sensitive neural layer and is supplied by a sophisticated microvascular network that delivers nutrients and carries away waste. As part of the human circulatory system, the network’s development tends to seek configurations which minimize operational energy expenditure, reflected by Murray’s Law of Minimal Work which relates the radii of parent and daughter vessels, giving rise to the network’s branching pattern [1]. Often diseases will have a vascular component that can manifest as abnormalities in this network and thus the network can be observed to acquire insight into the presence(or absence) of disease [2,3,4,5]. With advancements in non-invasive ocular imaging techniques such as optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) permitting the segmentation of the vasculature into well-defined layers [6], the retinal vasculature has become more accessible than ever for researchers. Hence, increasing attention has been paid to analyzing its quantitative characteristics as a potential diagnostic tool.

The retinal blood vessels form a complex branching pattern that has been shown to be fractal [5]. Therefore, a natural parameter for describing the retinal vasculature is the fractal dimension, first described by [7] and then introduced into ophthalmology by [4]. The fractal dimension is a real number that describes how an object’s detail changes at different magnifications. It can be thought of as an extension of the familiar Euclidean dimensions to allow for intermediate states. The fractal dimension of the retinal vascular tree lies between 1 and 2 [5], indicating that its branching pattern fills space more thoroughly than a line, but less than a plane. Thus, the retinal fractal dimension provides a measure of the tree’s global branching complexity, which can be altered by the rarefaction or proliferation of blood vessels in a disease scenario. In healthy human subjects, the retinal FD is around 1.7, which is similar to that of a 2D diffusion-limited aggregation process [4,5]. It has been postulated that this is because the retinal vasculature grows through diffusion of angiogenic factors in the retinal plane [8].

1.2. Common Methods for Measuring Retinal Fractal Dimension

After image acquisition, retinal images need to be processed first to extract the features of the vascular tree, a process known as vessel segmentation, before image binarization and then fractal analysis. Several algorithms exist for this purpose and the reader is referred to the literature [9,10,11]. We will now briefly discuss commonly used methods for calculating retinal fractal dimension.

Box-counting (capacity) dimension: The simplest and most common method used in the literature is the box-counting method [7] for fractal dimension. Given a binarized image of the retinal vascular tree, we overlay the image with a grid of boxes of side-length ε and count how many boxes contain a part of the tree. By decreasing ε, we capture more and more fine details of the tree from the covering. Taking N(ε) to be the box-count as a function of ε, the box-counting (capacity) dimension [12,13] is defined as

It should be noted that the base of the logarithm does not affect the calculated value.

Information dimension: Similar to the method for determining the box-counting dimension, we overlay the retinal image with a grid of boxes of side-length ε. Instead of a box count however, we assign to each box a weight based on its contribution to the tree’s information entropy and sum up the weights for each box, defining the information dimension [13,14] as

where is the total number of boxes that contain a part of the tree and is the proportion of retinal tree contained in the i-th box; is the number of pixels in the i-th box and is the total number of pixels in the tree.

Correlation dimension: We overlay the retinal image with a grid of side-length boxes and define the correlation integral [13] as

where H is the Heaviside step function and counts the number of tree pixel pairs such that the distance between them is less than . The correlation dimension is then defined as

Generalized dimensions: When discussing multifractal structures such as the retinal vasculature, they are more accurately described by an infinite hierarchy of fractal dimensions [15]. For any real q, the generalized fractal dimension is defined as

where

It can be seen and verified mathematically that correspond to the capacity, information, and correlation dimensions respectively as previously discussed. If then [16], so we have that , which is a useful check when computing fractal dimensions in practice.

1.3. Objective

This objective of this review is to provide an overview of the current scientific evidence of the association between human retinal FD and common retinal disorders, such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), retinal detachment, glaucoma, etc.

1.4. Research Question

Does the fractal dimension of the retinal vasculature change significantly due to retinal disease when compared to normals?

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The Preferred Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [17] were followed for this review. A search was conducted in the databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Scopus. Search queries were constructed by combining relevant subject headings and keywords with Boolean operators.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The goal of this review is to examine the scientific evidence comprehensively for a wide variety of retinal disorders rather than a select few. The eligibility criteria was determined using the PICO framework [18]. The study populations comprised of participants of any age, race, or gender that had been diagnosed with a retinal disorder. Interventions consisted of calculation of fractal dimensions on processed retinal vasculature images of subjects. Preferably, studies would state the model of the imaging device used, the region of interest which fractal analysis is conducted over, fractal analysis software packages used, and the types of fractal parameters that were calculated. Finally, studies had to compare fractal dimension in case subjects versus control subjects or contrast fractal dimension with disease progression from baseline to follow-ups.

Case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and case series were included. Studies that employed the following imaging techniques were acceptable:

- Digital fundus photography

- Fundus fluorescein angiography

- Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA)

- Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO)

Reviews and other types of articles without original research were not included. No restrictions on submission date or language were placed.

2.3. Screening Process

Search results from each of the databases were exported to Mendeley Reference Manager (Mendeley, London, UK) where duplicates were identified and removed. Subsequently, articles were screened based on title and abstract for relevance.

2.4. Meta-Analysis

To answer the question of whether the retinal fractal dimension changes significantly due to retinal disease, a meta-analysis was conducted using the data from the included studies. For each disease category, sample mean (SD) fractal dimensions were collected from each study of that category. For cases where studies provided different values for different retinal layers or disease severities, the combined mean (SD) FD was taken of all subgroups. If the study did not provide sample mean (SD) fractal dimension, then it was estimated from other statistics such as median (IQR) fractal dimension using methods by [19,20]. Otherwise, if there was too much discrepancy, then the study was excluded from the meta-analysis. Mean (SD) fractal dimensions were used to determine effect sizes for each study, which were then used to derive a summary effect size for each disease category using a random-effects model [21].

3. Results

3.1. Results of Study Selection

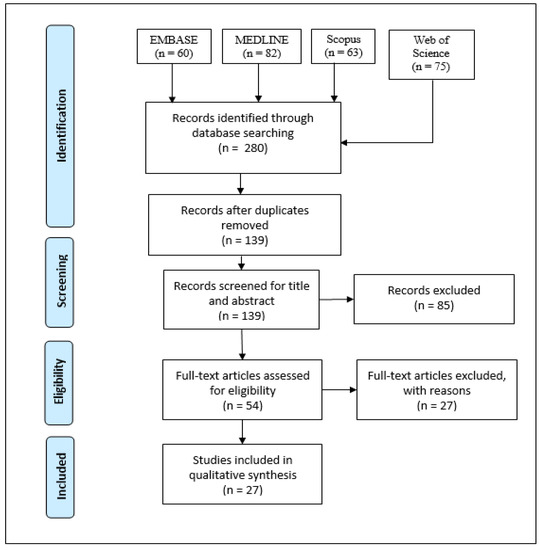

A total of 280 records were found initially from the search, leaving 139 records after duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts were then screened for relevance based off the PICO criteria described in the Methods section. This left 54 studies remaining to be considered, which were all read in-depth, resulting in 28 studies included in the final synthesis with reasons for exclusion for those that did not make the cut. The selection process is summarized in Figure 1. 27 of the selected studies exclusively focused on one disease: 10 on diabetic retinopathy (DR), 5 on myopia, 5 on diabetes mellitus (DM) in general, 2 on glaucoma, 2 on hypertension, 1 on macular telangiectasia type 2 (MacTel2), 1 on retinal occlusions, and 1 on nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). Only one study examined multiple diseases: DM, hypertension, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), myopia, and glaucoma.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Results of Specially Included Study

We decided to include the results of an earlier investigation conducted by [8], where the box-counting fractal dimension was measured for RNF and FFA images collected from patients at the University of Missouri School of Optometry. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes of fractal analysis on patients as reported by [8].

3.3. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Studies from Search

In total, 9514 subjects were considered in total for this review. We note that in reality, the number of eyes evaluated represents the true number of cases, but for compatibility reasons, we choose patients as our unit as some studies do not report the number of eyes examined. Studies focusing on diabetes mellitus mainly used random plasma glucose, Hb1Ac test, and/or diabetes duration as diabetic factors when comparing fractal dimensions. All diabetic retinopathy studies differentiated between different stages of disease with the most (5) using the ETDRS classification [22,23], 2 using the International Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale [24], and the remaining 3 not specifying a grading system. Classification of myopia varied among the myopia studies. Some studies considered patients that have high myopia, those with spherical equivalent refraction (SER) worse than −6 diopters. In contrast, the World Health Organization defines high myopia as having less than or equal to 5 diopters [25]. Others included patients with varying levels of myopic refraction with a cut-off point at −1.00 diopters. Of the studies which examined glaucoma, two used the International Society of Geographical and Epidemiological Ophthalmology scheme [26], while one used the Glaucoma Hemifield Test [27], pattern standard deviation, and optic nerve damage as indicators but did not say whether it was part of some standardized procedure. Studies on hypertension generally defined it as systolic blood pressure above 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure 80 mmHg. The clinical characteristics for each study can be seen in Table 2. Most of the studies adjusted for potential confounding factors such as age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors, and optical disorders using exclusion and/or multivariate regression. Age ranges varied between studies from schoolchildren as young at ages 11–12 to elderly adults as old as 71.

Table 2.

Demographic information and clinical characteristics of study populations.

3.4. Results of Studies Conducting Fractal Analysis on Retinal Images

Changes in the FD of the retinal vasculature in patients with retinal disorders are reported in Table 3. Setups for retinal imaging, vessel segmentation, and FD calculation were varied. Methodological variance was especially prominent for studies that employed OCTA as the imaging method, as often different studies considered different retinal vascular layers when calculating FD. Some studies also calculated FD on only the veins or arteries in an image, leading to the distinct parameters venular and arteriolar FD, apart from total FD. Digital fundus photography was the most common retinal imaging method, which was used by 14 out of the 28 studies with the most common field of view (FOV) being 45 degrees. The next most common imaging method was OCTA, which was used by 13 studies. Only one study used fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) as the imaging method. Although methodological setups were relatively varied across the studies, there were some similarities. One setup that was used by 5 of the studies was the use of the Singapore I Vessel Assessment (SIVA, National University of Singapore, Singapore) software combined with an optic disc centered annular ROI of 0.5 to 2.0 disc diameters. Another was the use of digital retinal photography combined with the fractal analysis package of the International Retinal Imaging Software (IRIS) for a circular ROI of 3.5 disc diameters centered at the optic disc, which was the choice of 4 other studies. Most of the studies (25 out of 28) calculated just the monofractal box-counting dimension of the retinal vascular tree and did not consider its multifractal properties. It should also be noted that 22 of the 28 studies examined retinal vascular parameters other than fractal dimension such as branching angles, caliber, and tortuosity. One study [28] was unique among the rest in that it examined the relationship between FD and a variety of different pathologies for the Singapore Malay Eye Study (SiMES) cohort. Another study [28] found a significant, independent association between decreased retinal FD and morbidities such as blood pressure and myopia. Glaucoma and Age-related macular degeneration were not significantly associated with FD and an association between diabetic retinopathy and FD was ruled out after multivariate regression analysis [28]. For the studies that looked at myopia [28,29,30,31,32,33], hypertension [27,33,34], glaucoma, and diabetes [34,35,36,37,38], all generally observed a mean decrease in fractal dimension relative to the control group or a decreasing trend with respect to increasing disease severity. In contrast, findings from the diabetic retinopathy studies were more mixed. Decreased retinal FD was found to be associated with presence of NPDR [39,40] and PDR [40]. Retinal FD also showed a decreasing trend with respect to diabetic retinopathy severity ranging from mild NPDR to PDR [37,38,41,42]. However, three studies found that greater retinal FD was associated with early retinopathy signs in young type 1 diabetic patients [43], incidence of referable diabetic retinopathy in urban Malay adults [44], and presence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes [45]. For retinographies from the DRIVE database, no significant change in FD was reported for patients with mild NPDR for the entire retina although a significant difference was found for the macular region [46]. A cohort study [47] also reported no association found between retinal FD and incident diabetic retinopathy in young diabetes patients after a mean (SD) follow-up period of 2.9 (2.0) years. For the studies that examined less common retinal diseases, decreased FD was found for OCTA images of the superficial and deep retinal layers in patients with retinal occlusions [48], an increase in arteriolar/venular FDs was found in NAION patients [49], and FD decreases were found in the deep/superficial retinal plexuses in MacTel2 patients [50].

Table 3.

Outcomes of fractal analysis for retinal pathology.

3.5. Results of Meta-Analysis

The results of the meta-analysis are reported in Table 4. Meta-analysis was conducted for the disease categories: diabetic retinopathy, diabetes mellitus, myopia, hypertension, and glaucoma. Studies examining retinal occlusions, AMD, NAION, and MacTel2 were excluded due to those categories each having less than two studies found from the search. Due to some studies stratifying their results by disease severity and/or retinal vascular layer, the averaged result was taken for those cases. For example, Zahid et al. (2016) provides mean (SD) FD values for both the deep and superficial capillary plexuses of the control group but not for the whole retina [40]; to obtain a value suitable for use in the meta-analysis, the combined mean and SD was computed with the two samples. Study effect sizes were calculated by subtracting the normal group mean from the case group mean. Due to heterogeneity between studies, a random effect model [21] was used to synthesize all study effect sizes to derive a summary effect size and its 95% confidence interval for each disease category. The diabetic retinopathy and myopia categories had the most data available and had summary effect sizes [95% C.I.] of −0.00269 [−0.0441, −0.0097] and −0.0176 [−0.0279, −0.0073] respectively, suggesting decreased fractal dimension for those pathologies. The other categories: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and glaucoma had summary effect sizes [95% C.I.] of −0.0118 [−0.0453, 0.0218], −0.0054 [−0.0125, 0.0017], and −0.0049 [−0.0423, 0.0324] respectively with the relationship remaining uncertain due the confidence intervals encompassing positive effect sizes as well.

Table 4.

Results of meta-analysis for retinal disease subgroups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations/Stability of Fractal Dimension

The outcomes of fractal analysis show decreased retinal FD in myopia, glaucoma, and hypertension but show inconsistent results for diabetic retinopathy. Other diseases that were considered in this review: AMD, MacTel2, NAION, and retinal occlusions were not investigated extensively enough in the literature for meta-analysis or to form a conclusive consensus. It is difficult to compare fractal analysis outcomes due to heterogeneity in methods. Often studies considered different regions of interest and vascular layers, as well as ignoring certain types of blood vessels instead of calculating over the entire tree. Variation in imaging methods, image processing, and fractal analysis tools is also concerning when comparing research between studies. Previously, the robustness of the FD parameter was explored with respect to different methodological setups and shown that retinal FD can be misleading in clinical applications due to its sensitivity to image quality and technique used [13]. Similarly, a significant dependence of FD on the vessel segmentation and dimensional calculation methods used has been found [51]. Even lesser factors such as image brightness, contrast, and focus can have significant impact on the final FD estimate [52]. A review has also been conducted on the association between retinal FD and neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s, cognitive impairment, and stroke [53]. Although a general decrease in retinal FD for patients with neurodegenerative pathology was observed, difficulties were also expressed with study comparison and there was a call for uniformization and standardization of procedures related to calculating retinal FD before establishing clinical applications [53]. Another important limitation of this study is that certain diseases may have significant changes in one retinal layer, but not for another layer.

4.2. Meta-Analysis

To answer the question of whether retinal FD changes significantly in a quantitative manner, a meta-analysis was conducted for each retinal disease category to derive a summary effect size using the available studies. A negative summary effect size was found for diabetic retinopathy and myopia, suggesting decreased retinal fractal dimension for patients with those pathologies while the results for diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, hypertension are uncertain. Some limitations of this analysis include combining the retinal vascular layers into one group, estimation of mean (SD) FD, study heterogeneity, as well as low sample size for diabetes, glaucoma, and hypertension. Taking the combined average of mean (SD) FD calculations over different retinal vascular layers is a source of error as the fractal dimension over the whole retina can be greater than over its constituent layers. Estimating the mean (SD) FD for a study given median (IQR) FD can also lead to errors in the meta-analysis. Furthermore, the demographics of each study vary widely in age and ocular history. This combined with the many variables that go into each stage of data acquisition/processing when performing fractal analysis leads to large heterogeneity. Due to this, we reiterate that a standardized procedure for retinal fractal analysis should be developed to facilitate inter-study comparison and support future meta-analyses.

5. Conclusions

This review summarizes the current scientific literature on the association between FD and retinal disease. The nature of the association depends on the type of retinal disease in consideration. The results of the qualitative synthesis show decreased fractal dimension associated with presence of glaucoma, hypertension, and myopia. However, the results of the meta-analysis show that the decrease is strongest with diabetic retinopathy and myopia and weak for diabetes, glaucoma, hypertension. Due to the variances in methodological setups for retinal image processing and FD calculation, it is difficult to form a consensus on effect. Hence, before moving onto clinical applications of FD, it is necessary that a standardized protocol for image acquisition/processing be established first to facilitate inter-study comparison.

Author Contributions

Reading and writing, S.Y. and V.L.; project proposal, review and editing, V.L. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.Y. received funding from the Government of Canada’s Student Work Placement Program (SWPP) to do a four-month co-op with the Faculty of Science, University of Waterloo under the supervision of V.L., V.L. also acknowledges a Discovery grant from The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| AMD | age-related macular degeneration |

| AVR | arteriolar to venular diameter ratio |

| BAa/v | arteriolar/venular branching angle |

| BCa/v | arteriolar/venular branching coefficient |

| CRAE | central retinal arteriolar equivalent |

| CRVE | central retinal venular equivalent |

| cTORTa/v | curvature arteriolar/venular tortuosity |

| DCP | deep capillary plexus |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DR | diabetic retinopathy |

| DRL | deep retinal layer |

| DVP | deep vascular plexus |

| FD | fractal dimension |

| FAZ | foveal avascular zone |

| FFA | fundus fluorescein angiography |

| FOV | field of view |

| FDa/v/t | arteriolar/venular/total fractal dimension |

| IOP | intraocular pressure |

| MacTel2 | macular telangiectasia type 2 |

| NAION | nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| NPDR | non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| OCTA | optical coherence tomography angiography |

| OD | optic disc |

| PDR | proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| POAG | primary open angle glaucoma |

| RNF | retinal nerve fiber |

| ROI | region of interest |

| RVP | retinal vessel parameter |

| SCP | superficial capillary plexus |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SRL | superficial retinal layer |

| SVP | superficial vascular plexus |

| TORTa/v | arteriolar/venular simple tortuosity |

References

- Murray, C.D. The Physiological Principle of Minimum Work: I. The Vascular System and the Cost of Blood Volume. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1926, 12, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daxer, A. Characterisation of the Neovascularisation Process in Diabetic Retinopathy by Means of Fractal Geometry: Diagnostic Implications. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch. Klin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1993, 231, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daxer, A. The Fractal Geometry of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Implications for the Diagnosis and the Process of Retinal Vasculogenesis. Curr. Eye Res. 1993, 12, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Family, F.; Masters, B.R.; Platt, D.E. Fractal Pattern Formation in Human Retinal Vessels. Phys. Nonlinear Phenom. 1989, 38, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainster, M.A. The Fractal Properties of Retinal Vessels: Embryological and Clinical Implications. Eye Lond. Engl. 1990, 4, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.P.; Zhang, M.; Hwang, T.S.; Bailey, S.T.; Wilson, D.J.; Jia, Y.; Huang, D. Detailed Vascular Anatomy of the Human Retina by Projection-Resolved Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Wheeler, J.A. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. Am. J. Phys. 1983, 51, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, V.; Raghuram, A.; Myerson, J.; Varadharajan, S. The Fractal Dimension in Retinal Pathology. J. Mod. Opt. J. MOD Opt. 2003, 50, 1701–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.V.B.; Leandro, J.J.G.; Cesar, R.M.; Jelinek, H.F.; Cree, M.J. Retinal Vessel Segmentation Using the 2-D Gabor Wavelet and Supervised Classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2006, 25, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bekkers, E.; Abbasi, S.; Dashtbozorg, B.; ter Haar Romeny, B. Robust and Fast Vessel Segmentation via Gaussian Derivatives in Orientation Scores. In Image Analysis and Processing—ICIAP 2015; Murino, V., Puppo, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 537–547. [Google Scholar]

- Staal, J.; Abramoff, M.D.; Niemeijer, M.; Viergever, M.A.; van Ginneken, B. Ridge-Based Vessel Segmentation in Color Images of the Retina. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2004, 23, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M. Box-Counting Fractal Dimension in Application to Recognition of Hypertension through the Retinal Image Analysis. Przeglad Elektrotechniczny 2013, 89, 286–289. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Dashtbozorg, B.; Zhang, J.; Bekkers, E.; Abbasi-Sureshjani, S.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; Ter Haar Romeny, B.M. Reliability of Using Retinal Vascular Fractal Dimension as a Biomarker in the Diabetic Retinopathy Detection. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 6259047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On the Dimension and Entropy of Probability Distributions. Acta Math. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1959, 10, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tălu, S. Multifractal Geometry in Analysis and Processing of Digital Retinal Photographs for Early Diagnosis of Human Diabetic Macular Edema. Curr. Eye Res. 2013, 38, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E. Chaos in Dynamical Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-521-43799-8. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally Estimating the Sample Mean from the Sample Size, Median, Mid-Range, and/or Mid-Quartile Range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, G. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. Alex J. Sutton, Keith R. Abrams, David R. Jones, Trevor A. Sheldon and Fujian Song, Wiley, Chichester, U.K., 2000. No. of Pages: Xvii+317. ISBN 0-471-49066-0. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 3112–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Study. Report Number 6. Design, Methods, and Baseline Results. Report Number 7. A Modification of the Airlie House Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981, 21, 1–226. [Google Scholar]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading Diabetic Retinopathy from Stereoscopic Color Fundus Photographs--an Extension of the Modified Airlie House Classification. ETDRS Report Number 10. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C.P.; Ferris, F.L.; Klein, R.E.; Lee, P.P.; Agardh, C.D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J.T.; et al. Proposed International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema Disease Severity Scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Brien Holden Vision Institute The Impact of Myopia and High Myopia. Report of the Joint World Health Organization-Brien Holden Vision Institute Global Scientific Meeting on Myopia. Available online: https://www.visionuk.org.uk/download/WHO_Report_Myopia_2016.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Foster, P.J.; Buhrmann, R.; Quigley, H.A.; Johnson, G.J. The Definition and Classification of Glaucoma in Prevalence Surveys. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asman, P.; Heijl, A. Glaucoma Hemifield Test. Automated Visual Field Evaluation. Arch. Ophthalmol. Chic. Ill 1960 1992, 110, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Thomas, G.N.; Tay, W.; Ikram, M.K.; Hsu, W.; Lee, M.L.; Lau, Q.P.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Fractal Dimension and Its Relationship With Cardiovascular and Ocular Risk Factors. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 154, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sheikh, M.; Phasukkijwatana, N.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Rahimi, M.; Iafe, N.A.; Freund, K.B.; Sadda, S.R.; Sarraf, D. Quantitative OCT Angiography of the Retinal Microvasculature and the Choriocapillaris in Myopic Eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemin, M.Z.C.; Daud, N.M.; Ab Hamid, F.; Zahari, I.; Sapuan, A.H. Influence of Refractive Condition on Retinal Vasculature Complexity in Younger Subjects. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 783525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Mitchell, P.; Liew, G.; Rochtchina, E.; Kifley, A.; Wong, T.Y.; Hsu, W.; Lee, M.L.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, J.J. Lens Opacity and Refractive Influences on the Measurement of Retinal Vascular Fractal Dimension. Acta Ophthalmologica 2010, 88, e234–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Gregori, G.; Roisman, L.; Zheng, F.; Ke, B.; Qu, D.; Wang, J. Retinal Microvascular Network and Microcirculation Assessments in High Myopia. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 174, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Yang, X.; Feng, L.; Hu, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, F.; Shen, M. Retinal Microvasculature Alteration in High Myopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 6020–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grauslund, J.; Green, A.; Kawasaki, R.; Hodgson, L.; Sjolie, A.K. Retinal Vascular Fractals and Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications in Type 1 Diabetes. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, M.; Bates, N.M.; Milosevic, N.T.; Tian, J.; Smiddy, W.E.; Lee, W.-H.; Somfai, G.M.; Feuer, W.J.; Shiffman, J.C.; Kuriyan, A.E.; et al. Investigating the Fractal Dimension of the Foveal Microvasculature in Relation to the Morphology of the Foveal Avascular Zone and to the Macular Circulation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydkjaer-Olsen, U.; Soegaard Hansen, R.; Pedersen, K.; Peto, T.; Grauslund, J. Retinal Vascular Fractals Correlate With Early Neurodegeneration in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 7438–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tang, F.Y.; Ng, D.S.; Lam, A.; Luk, F.; Wong, R.; Chan, C.; Mohamed, S.; Fong, A.; Lok, J.; Tso, T.; et al. Determinants of Quantitative Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Metrics in Patients with Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.Y.; Chan, E.O.; Sun, Z.; Wong, R.; Lok, J.; Szeto, S.; Chan, J.C.; Lam, A.; Tham, C.C.; Ng, D.S.; et al. Clinically Relevant Factors Associated with Quantitative Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Metrics in Deep Capillary Plexus in Patients with Diabetes. EYE Vis. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avakian, A.; Kalina, R.E.; Sage, E.H.; Rambhia, A.H.; Elliott, K.E.; Chuang, E.L.; Clark, J.I.; Hwang, J.-N.; Parsons-Wingerter, P. Fractal Analysis of Region-Based Vascular Change in the Normal and Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retina. Curr. Eye Res. 2002, 24, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, S.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Freund, K.B.; Balaratnasingam, C.; Dansingani, K.; Gilani, F.; Mehta, N.; Young, E.; Klifto, M.R.; Chae, B.; et al. Fractal Dimensional Analysis of Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Eyes With Diabetic Retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 4940–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Tsui, E.; Zahid, S.; Young, E.; Mehta, N.; Agemy, S.; Garcia, P.; Rosen, R.B.; Young, J.A. Value Of Fractal Analysis Of Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography In Various Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy. Retina 2018, 38, 1816–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Kitahara, J.; Toriyama, Y.; Kasamatsu, H.; Murata, T.; Sadda, S. Quantifying Vascular Density and Morphology Using Different Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiographic Scan Patterns in Diabetic Retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N.; Donaghue, K.C.; Liew, G.; Rogers, S.L.; Wang, J.J.; Lim, S.-W.; Jenkins, A.J.; Hsu, W.; Li Lee, M.; Wong, T.Y. Quantitative Assessment of Early Diabetic Retinopathy Using Fractal Analysis. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Sabanayagam, C.; Law, A.K.; Kumari, N.; Ting, D.S.; Tan, G.; Mitchell, P.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Geometry and 6 Year Incidence and Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Tan, G.S.W.; Agrawal, R.; Yanagi, Y.; Sie, N.M.; Wong, C.W.; San Yeo, I.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Wong, T.Y. Optical Coherence Tomographic Angiography in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki, A.C.B.; Oliveira, A.J.; Mendonca, M.B.M.; Barbosa, C.T.F.; Nogueira, R.A. Can the Fractal Dimension Be Applied for the Early Diagnosis of Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy? Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2009, 42, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lim, S.W.; Cheung, N.; Wang, J.J.; Donaghue, K.C.; Liew, G.; Islam, F.M.A.; Jenkins, A.J.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Fractal Dimension and Risk of Early Diabetic Retinopathy: A Prospective Study of Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2081–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulisis, N.; Kim, A.Y.; Chu, Z.; Shahidzadeh, A.; Burkemper, B.; De Koo, L.C.O.; Moshfeghi, A.A.; Ameri, H.; Puliafito, C.A.; Isozaki, V.L.; et al. Quantitative Microvascular Analysis of Retinal Venous Occlusions by Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remond, P.; Aptel, F.; Cunnac, P.; Labarere, J.; Palombi, K.; Pepin, J.L.; Pollet-Villard, F.; Hogg, S.; Wang, R.; MacGillivray, T.; et al. Retinal Vessel Phenotype in Patients with Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 208, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzaridis, S.; Wintergerst, M.W.M.; Mai, C.; Heeren, T.F.C.; Holz, F.G.; Charbel Issa, P.; Herrmann, P. Quantification of Retinal and Choriocapillaris Perfusion in Different Stages of Macular Telangiectasia Type 2. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 3556–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo de Mendonça, M.B.; de Amorim Garcia, C.A.; de Albuquerque Nogueira, R.; Gomes, M.A.F.; Valença, M.M.; Oréfice, F. Fractal analysis of retinal vascular tree: Segmentation and estimation methods. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2007, 70, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wainwright, A.; Liew, G.; Burlutsky, G.; Rochtchina, E.; Zhang, Y.; Hsu, W.; Lee, J.; Wong, T.-Y.; Mitchell, P.; Wang, J. Effect of Image Quality, Color, and Format on the Measurement of Retinal Vascular Fractal Dimension. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 5525–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, S.; Devulder, A.; Van Keer, K.; Bierkens, J.; De Boever, P.; Stalmans, I. Systematic Review on Fractal Dimension of the Retinal Vasculature in Neurodegeneration and Stroke: Assessment of a Potential Biomarker. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).