Abstract

Data hiding technology has achieved many technological developments through continuous research over the past 20 years along with the development of Internet technology and is one of the research fields that are still receiving attention. In the beginning, there were an intensive amount of studies on digital copyright issues, and since then, interest in the field of secret communications has been increasing. In addition, research on various security issues using this technology is being actively conducted. Research on data hiding is mainly based on images and videos, and there are many studies using JPEG and BMP in particular. This may be due to the use of redundant bits that are characteristic of data hiding techniques. On the other hand, block truncation coding-based images are relatively lacking in redundant bits useful for data hiding. For this reason, researchers began to pay more attention to data hiding based on block-cutting coding. As a result, many related papers have been published in recent years. Therefore, in this paper, the existing research on data hiding technology of images compressed by block-cut coding among compressed images is summarized to introduce the contents of research so far in this field. We simulate a representative methodology among existing studies to find out which methods are effective through experiments and present opinions on future research directions. In the future, it is expected that various data hiding techniques and practical applications based on modified forms of absolute moment block truncation coding will continue to develop.

1. Introduction

With the development of Internet technology, a large number of multimedia data are exchanged on the Internet. Moreover, the development of social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter have made it possible for many people to conveniently share and communicate their digital content. In other words, data such as text, image, video, and audio are exchanged through the platforms. These contents are often copied, edited, and distributed by other users and are used for purposes other than the original creators’ intention, causing legal problems. Data Hiding (DH) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] technology can also be used to protect data and verify that received content has been tampered with. Encryption [8] technology can also be one solution to this security problem. However, there is also the problem of making the attacker more interested in encrypted digital content in this case.

The DH can conceal its existence by secretly embedding secret data into cover media such as text, images, and video.

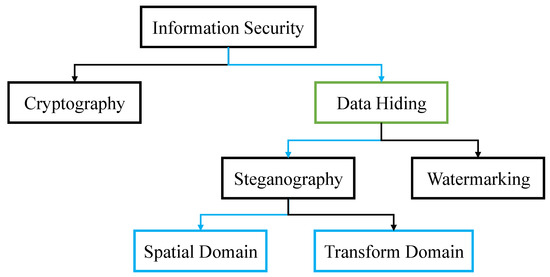

Meanwhile, information security can be described in a simplified manner as the prevention of unauthorized access or alteration during the time of storing data or transferring it from one machine to another. The information can be biometrics, social media profiles, data on mobile phones, etc., due to which the research for information security covers various sectors such as cryptocurrency and online forensics. Information security is one of the useful technologies to achieve its purpose by encryption and data hiding technology. Data hiding techniques can be broadly classified into steganography [3,9,10,11,12] and watermarking [7,8,13,14] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification of information security.

It can use three methods according to the characteristics of digital media, which correspond to the spatial domain, the frequency domain, and the compression domain. The spatial domain-based method [15,16,17] may embed secret data in the Least Significant Bit (LSB) of pixels directly. The merit of this kind of method is that it is intuitive to embed secret data while maintaining image quality. On the other hand, there is a problem that hidden data may be lost by an attack, such as compression. The frequency-domain method [18,19] is a method of inserting data into the transformed coefficients after each block of the cover image is converted to a frequency domain. The advantage is that it has strong characteristics in image transformation, such as compression, while the disadvantage is that it cannot hide enough data, and the image quality is sensitive by the transformed coefficients.

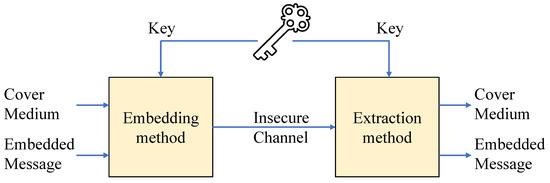

Generally, the DH follows the procedure in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Basic structure of data hiding.

One method that extracts data from a stego image, in which data are hidden and then can exactly restore the original cover image, is called Reversible DH (RDH) [4,5,6,20], and another method that does not is classified as non-RDH, i.e., DH. The RDH can be considered as a superior method compared to the DH.

Compressed domain-based methods embed data in coefficients covertly, such as Block Truncation Coding (BTC) [21], Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) [22], and compressed archieve [12] On the other hand, JPEG and BTC [21] compression methods are lossy compression methods to increase compression performance and are evaluated as methods that balance image quality and compression performance. In particular, the JPEG is a method using the characteristic that the human eye has a lower ability to distinguish when the brightness changes at high frequencies. Because of this, much of the high-frequency component can be discarded. This operation divides each component in the frequency domain by a certain constant and obtains the quotient of the integer. The high-frequency components obtained here can be positive or nearly zero and are often negative. By applying weights during quantization, a lot of low frequencies with high energy are saved, but high frequencies are cut off because there is little difference in the total energy.

Bruno et al. [12] proposed steganography for cloud-based data exchange utilizing compressed archives as a buying matrix. Data hiding is achieved by properly encoding the characteristics of the compressed archive, namely the hierarchical structure and the compression algorithm used to create it. For BTC, compression is performed by obtaining a bitmap and two quantized levels for each block using a simple formula, and the image quality is inferior to that of JPEG, but it shows a level of performance that is not significantly different according to the human visual system.

The lossy compression technique is effective in reducing the bandwidth by reducing the media size when the loss of some content does not significantly affect the meaning of the media. In other words, the lossy compression method can reduce the bandwidth in terms of content sharing of the Social Networking Service (SNS) platform, so it affects the overall performance of the system. For this reason, DH technology based on lossy compression is also being actively studied, and among them, many papers on DH technology based on BTC are being researched and published. At this point, we think that it is meaningful to classify research papers on BTC-based DH, evaluate the performance, and consider the direction of future research.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives the introduction of the background of Absolute Moment BTC (AMBTC). The existing data hiding research based on AMBTC and BTC are described in detail in Section 3. The simulation results are analyzed in Section 4. Section 5 draws the conclusions.

2. Absolute Moment Block Truncation Coding

BTC is a lossy compression method for grayscale images that divides the original image into blocks and then uses quantization to reduce the number of grayscale levels using the mean and standard deviation. This method can also be applied to video compression. BTC was first proposed by Delp and Mitchell [21]. Another variation of BTC is Absolute Moment Block Truncation Coding, or AMBTC, in which, instead of using standard deviations, absolute moments are preserved with the mean. AMBTC is simpler to calculate than BTC and usually has a lower mean squared error.

AMBTC was proposed by Lema and Mitchell [23]. For pixels per block, it is compressed at a ratio of () when a pixel is 8 bits, where 2 denotes two quantization levels. Increasing the block size improves the compression rate, while the quality of the image allowed is bad. A block of AMBTC is composed of two quantization levels and a bitmap for each block after compression. The distortion of AMBTC is the difference between the compressed pixels and the original pixels, but the difference is not high. If the block size is , the compression ratio (CR) (=original image size/compressed image size) is 4, so the bitrate of the block is 2 bits per pixel. The merit of it is simple computation and fast image compression. In AMBTC, a grayscale image is divided into non-overlapping ()-sized blocks, where k will be , , and so on. For each block, the mean pixel value is computed by

where is the value of the ith pixel of the block of size . Every pixel in the block is quantized into the bitmap (0 or 1). That is, if the corresponding pixel is greater than or equal to the mean (), it will be replaced with ‘1’, otherwise ‘0’. The pixels in each block are divided into two groups: ‘1’ and ‘0’. The symbols t and represent the number of pixels of ‘1’ and the number of pixels of ‘0’, respectively. The two quantization levels are calculated by Equation (2).

where and are also used to reconstruct AMBTC, and and denote the quantization levels. is the floor function that takes real number x and gives as output the greatest integer less than or equal to x. For example, it is used like . and are, respectively, the higher and lower means. Each pixel in a bitmap is created by using the original pixels and the mean of a block. That is, if each pixel is larger than the mean, it is assigned to ‘1’ and otherwise, ‘0’ (see Equation (3)).

The basic unit of compression is trio (), and is composed of two quantization levels , and a bitmap (BM). To reconstruct the image, decoding is performed using Equation (4).

Finally, a block of the image is compressed into two quantization levels (, ) and a bitmap , i.e., trio . A bitmap contains the bit-planes that represent the pixels, and the values and are used to decode the AMBTC compressed image. For the case , e.g., we deal with an image by block-wise operation. Sixteen pixels in a block are represented as a trio of 8 + 8 + 16 = 32 bits, and thus the CR is ()/32 = 4. Consider the example of a -pixel image. The file size of bits can be reduced to bits. In decoding phase, when two quantization levels and the bitmap obtained, the corresponding image block can be easily reconstructed by replacing every ‘1’ in a bitmap with , while every ‘0’ is replaced with .

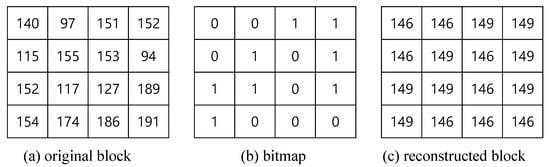

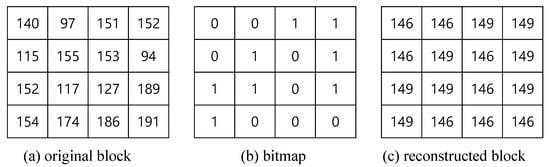

Example 1.

Here, we explain the encoding of one block of a grayscale image using AMBTC. Figure 3a is a grayscale block, and the mean value of the pixels is 122. By applying Equations (2)–(4) on Figure 3a, we can obtain the bitmap as shown in Figure 3b and two quantization levels (). The basic unit of each block is trio () = (146, 149, 0011010111011000). Using the trio, we may recover the grayscale block as shown in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

An example of AMBTC; (a) original block; (b) a bitmap; (c) reconstructed block.

3. Survey of Related Works

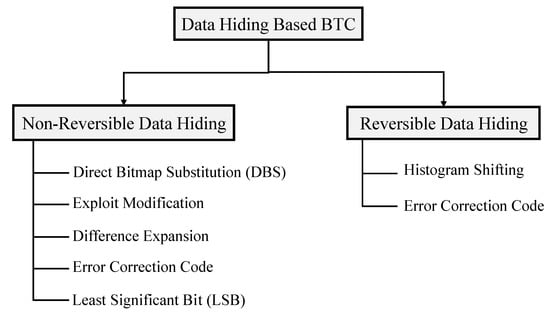

In this section, we summarize the various DH schemes based on AMBTC [23] and BTC [21,24]. The reason for summarizing this field is the advantage of seeing the big picture of this field of research by arranging and summarizing individual studies. In addition, it is possible to clarify the direction of future research based on this. Therefore, in this paper, we will examine DH papers based on AMBTC and BTC with a systematic category. DHs are classified into two categories as Non-Reversible DH (NRDH) and Reversible DH (RDH), as mentioned before (Figure 4). The scheme of DH is classified into direct bitmap substitution [25], exploit modification [26], difference expansion [27], Errorr Correction Coding (ECC) [28], and Least Signficant Bit (LSB). RDH methods are classified into Histogram Shifting (HS) and ECC.

Figure 4.

Classification of DH based on BTC/AMBTC.

In this section, we will briefly introduce the representative papers of the classified methods.

3.1. Non-Reversible Data Hiding

3.1.1. Direct Bitmap Substitution (DBS)

Chuang and Chang [25] proposed an AMBTC-based DH that directly partitions the blocks of an image into smooth blocks and complex blocks and then substitubes the bitmaps of the smooth blocks with secret bits. The threshold T is used to divide the image into smooth and non-smooth blocks. The T is a means of determining the embedding capacity (EC) and the quality of the cover image. That is, if T is raised, the EC increases in proportion to it, and on the contrary, the quality of the cover image deteriorates. That is, the merit of it is that the quality of the stego image (note that the cover image hides the secret bit) can be controlled by adjusting the threshold .

Ou and Sun [29] introduced a method of inserting data into a bitmap of a smooth block and proposed a method to reduce distortion of the image by adjusting the two quantization levels through recomputation, but the recomputation requires the original image. Chen and Chi [30] subdivided less complex blocks and highly complex blocks. In 2016, Malik et al. [31] introduced an AMBTC-based DH using a 2-bit plane and four quantization levels. The merit of this method is the high payload, and the demerit is the reduced compression ratio. This study, after further extension by Kumar et al., provides improved image quality and higher DH capacity while reducing the compression ratio in half. Existing studies based on BTC used DBS together with their methods. The reason seems to lie in the improvement of the data hiding capacity and the improvement of the image quality.

Example 2.

Here, we explain how to embed 16-bits into the trio () = (146, 149, 0011010111011000) by using DBS (see Figure 3). Let us assume that the secret data d = {1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0} are used here, and the threshold value T is 5. If the difference between the two quantization levels is less than 5 (predefined threshold value), it corresponds to a smooth block. Therefore, DBS need to be performed. As a result, the updated trio is trio () = (146, 149, 1001001011110000), where underlined pixels are updated.

3.1.2. Exploit Modification Direction

Hong [32] introduced a DH method based on Pixel Pair Matching (PPM) [33], which is originated from the Exploit Modification Direction (EMD) [26]. The EMD method belongs to the superior method among spatial domain-based DH methods. PPM is a technique that embeds digits in -ary notational system into pixel pairs by matching the secret digits with entities in a reference table, which is a table that fills with digits ranging from 0 to . Let us assume that is the entity located at the i-th column and the j-th row of the reference table , where is a constant. For instance, when and 64, , and 14, respectively. Let , , and the secret digits in 16-ary notational system be embedded as . The reference table can be constructed using . The design of the reference table affects the embedding performance of the PPM-based method. As this method is applied to two quantized pixels per block, when a small amount of data are hidden, the quality of the cover image can be guaranteed, but when a large amount of data are hidden, the quality of the image can greatly deteriorate.

Hong et al. [34] introduced a difference matching technique to minimize distortion caused by inserting secret data into the quantization levels. This technique adjusts the quantization values to minimize. Thus, the quality of the cover image and DH capacity were improved.

Su et al. [35] proposed an authentication method for AMBTC. First, after dividing each block into two sub-bitmaps, a 6-bit authentication code is allocated to the two sub-codes. In order to hide the 6-bit authentication code, each separated bitmap is allocated as a codeword, and then 3 bits are inserted using matrix encoding, respectively. To overcome the distortion caused by bitmap modifications, instead of directly flipping these bits in the bitmap, the corresponding bit position information to be flipped is written. Then, the bit position is inserted into the quantization level based on the adjusted quantization level matching.

Kim et al. [36] proposed a method of hiding data by applying the EMD method [26] (Equation (5)) to two divided parts of a bitmap block. First of all, each divided bitmap converted to decimal number is required before performing DH.

No modification is needed if a secret digit d equals the extraction function of the original pixel group. When , calculate . If s is greater than or equal to 2, increase the value of by 1; otherwise, decrease the value of by 1.

Lee et al. [37] proposed a turtle shell method that is derived from EMD [26]. It has proven to be effective against AMBTC as well as having excellent DH performance, especially in spatial domain-based images. This method requires a turtle shell table for data hiding and extraction. The merit of this method is that it is strong against security attacks. That is, even if the attacker knows that the data is hidden, it is difficult to infer the hidden data in this way.

Example 3.

Suppose two AMBTC trios ( are to be embedded with secret data . For example, consider the quantization levels () and the threshold is . We may obtain in a 5-ary notational system. Since in this example, no correction is needed for the two quantization levels in this example.

3.1.3. Difference Expansion (DE)

Alattar et al. [4] introducted an algorithm that hides several bits in the difference expansion (DE) of vectors of adjacent pixels. In 2017, Huang et al. [38] proposed a DH method exploiting the pixel difference of two quantization levels using DE and the embedding bit rate of this method is -bits. To improve image quality, a way of adjusting the difference between two quantization levels is introduced.

Let be the difference between two quantization levels and , i.e., . Here, let D be the decimal value of secret bits. The following Equations (6) and (7) allow to revise quantization levels to carry secret bits:

Example 4.

Suppose , and the bits to be embedded are . Because , the block is smooth, and we have . According to Equation (6), we have , . To extract the embedded bits, we calculate . The embedded bits are .

3.1.4. Error Correction Coding (ECC)

Kim et al. [39] enlarged the cover image using the nearest neighbor interpolation algorithm and converted it to AMBTC, and proposed a method for efficiently hiding large amounts of data by applying the HC (7,4) code to this cover image. It seems that their method is superior to the existing DH method in terms of efficiency. Hamming Code (HC) is a single Error-Correcting linear block Code (ECC) with a minimum distance of three for all the codewords. In HC (), n is the length of the codeword, k is the number of information bits, and is the number of parity bits. Let x be a k-bit information word, and the n-bit codewords y are generated by using , where G is the matrix. Let be the error vector that determines whether an error occurred while sending y. The single error e could be corrected by using the syndrome , where the syndrome S denotes the position of the error in the codeword. HC (7,4) is used to hide 3 bits for every 7-bit pixel group of the bitmap, and BM in trios is a codeword.

Bai and Chang [40] introduced a way to hide data using Hamming code. However, this method had problems in efficiency compared to the existing methods. In order to improve the problems of Bai and Chang [40], Kim et al. [41] use an optimized Hamming code lookup table to minimize errors in data hiding. The performance of the proposed method is good in terms of DH capacity and quality.

Kumar et al. [42] proposed a new AMBTC-based DH technique using Hamming distance and pixel value difference method. This method first preprocesses the original image with a smoothing filter so that the quality can be maintained even after AMBTC compression. After that, 8 bits of secret data are inserted into the bit plane of the less complex block using Hamming distance calculation.

Example 5.

When trio is () = (146, 149, 0011010111011000), the first 7 bits of BM are as the codeword. For the codeword y, first find the syndrome . When the secret bit , in order to hide the secret bits d in the codeword, a new is obtained, and then the 6th pixel of is flipped. The codeword has hidden bits d. In case that this trio is transmitted to the receiving side, it will directly obtain 3-bit information from the first 7 pixels of the trio’s BM by using HC (7, 4). That is, .

3.1.5. Least Significant Bits (LSB) Substitution

Horng et al. [43] use quotient value difference (QVD) and LSB substitution to hide secret data in AMBTC. This method includes three phases of embedding. In the first phase, QVD and LSB substitution are applied to embed secret digits into the low mean and high mean values. In the second phase, an additional bit is embedded by alternating the order of the low mean and high mean or not. Secret digits are embedded in the third phase by substituting the bitmap of smooth blocks. Assume that the decimal conversion value of n hidden bits to be hidden is D. In order to hide D in two quantization values, we need to know the difference and range of the two quantization values. First, the difference between the quotients of the two quantized values is , where and . Second, the range of is . Third, the new is , and the DH is determined by Equation (8).

Kim et al. [44] present a DH method based on Adaptive BTC Edge Quantization (ABTC-EQ) using an optimal pixel adjustment process (OPAP) [45] to optimize two quantization levels. ABTC-EQ as a cover media is superior to AMBTC in maintaining a high-quality image after encoding is completed. ABTC-EQ is represented by a form of trio () where is quantization levels () and BM is a bitmap. LSB substitution for OPAP is performing the following procedure: First, suppose that the n-bit secret message D is to be embedded into the k-rightmost LSBs of two quantization levels, where . Second, the secret message D is rearranged to form a k-bit as . The mapping between the n-bit secret message D and the embedded message can be defined as . Third, the pixel value p (here, two quantization levels) is modified to form as .

Example 6.

The given trio, secret bits, and k are () = (146, 149, 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0), , and , respectively; we embed the secret bit using the LSB replacement. That is, and . Here, 4 bits were hidden in 2 pixels, and an error of 1 bit occurred. Assuming that the transmitting side and the receiving side share k, the remainders obtained by dividing each pixel by become the hidden values.

3.2. Reversible Data Hiding

3.2.1. Histogram Modification

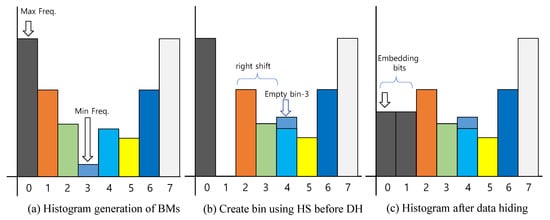

Lin et al. [46] proposed the RDH based on histogram shifting (HS). First, a histogram is constructed from the bitmaps. Second, it embeds secret data by revising the histogram according to be hidden bits. That is, after generating a histogram on three-pixel groups (patterns) in the bitmap BM, the highest and lowest frequencies will be obtained, respectively. Since it is impossible to directly apply HS to bitmap images, a process of converting them to decimal is required. After creating a histogram from virtual pixel values (a decimal number made up of binary numbers), DH is performed by moving the pixel values according to the hidden bits. The detailed process [6] of DH follows the procedure below.

- 1.

- Generate its histogram .

- 2.

- Grayscale value is obtained from converting three pixels in the bitmap image to a decimal number.

- 3.

- In the histogram , find the maximum point and the minimum point .

- 4.

- If the minimum point , save the position of those pixels and the pixel gray value b as bookkeeping information.

- 5.

- Move the whole part of the histogram with to the right by 1 unit (Figure 5b).

- 6.

- Scan the image, and once meeting the pixel a, check the to-be-embedded bit. If the to-be-embedded bit is ‘1’, the pixel grayscale value is changed . If the bit is ‘0’, the pixel value remains a (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Embedding procedure using histogram shift.

In Lin and Liu [46], the first process is to use the order of two compressed quantization levels such as trio (). If the difference between the values of the quantization levels is , the data can be embedded by the order of the quantization levels. That is, if the bit is , the trio () is intact, and if , replace it with trio (). Hidden bits can be extracted simply by scanning the order of two quantization levels, and there is no problem in restoring the original order. The method of histogram-based DH here is similar to what was mentioned before. First, the BM image is scanned in 4-bit units. If the 4-bit pattern is the peak point and the secret bit is , the peak point is not changed. Otherwise, if the 4-bit pattern is the peak point and , change the peak point to a zero point pattern. For the histogram shift method, it is best if the zero point is 0. Otherwise, the zero point part should be recorded in a separate method and used when restoring the image.

Shie et al. [47] introduced HS for DH within every bitmap. First, the histogram is constructed after converting all blocks except for the block where the difference value (DV, ) is 0 in 4-bit units. Find the two pairs of peak P and low point L in the generated histogram. For each frequency, find the midpoint between the highest and lowest points. If the secret bit is 0, leave the bitmap unchanged. Otherwise, it modifies the bitmap into a bitmap with converted decimal values equal to the values at that midpoint. Only bitmaps of blocks whose DV is lower than the predefined threshold T are used to contain secret bits.

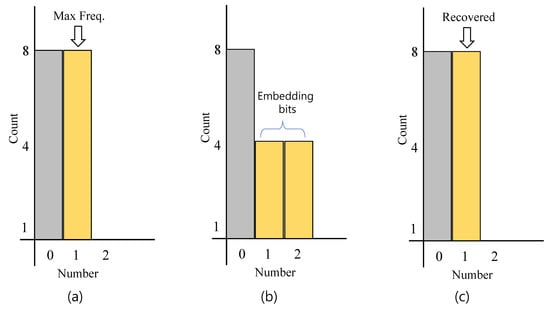

Kim et al. [48] proposed RDH using HS for AMBTC compressed images. As mentioned earlier, each block of AMBTC contains a bitmap BM made up of 0’s and 1’s. Here, their suggestion is to use ‘2’ in addition to ‘0’ and ‘1’ for the bitmap. In other words, the secret bit is hidden by moving the pixel ‘1’ to ‘2’ according to hidden bits. Figure 6a shows a histogram of a bitmap BM, where the number of ‘0’ pixels is 8 and ‘1’ pixels is 8. Next, it begins data embedding by dealing out bin ‘1’ according to the message. If the secret bit is ‘0,’ keep ‘1’ (bin 1) values without moving to 2’s (bin 2). Otherwise, the 1’s (bin 1) move to 2’s (bin 2). Figure 6b shows the image after DH is completed, and Figure 6c shows the histogram of the restored bitmap after extracting the data hidden in the bitmap. This method provides high EC while maintaining low distortion.

Figure 6.

Embedding procedure using histogram shift based on BM: (a) histogram generation of a BM (), (b) histogram after embedding bits, and (c) extraction of hidden bits and reconstructed histogram.

To further increase EC, there have been several variants such as multilevel histogram shifting given by Zhao et al. [49], residual histogram shifting by Chang et al. [50], and bi-stretch hiding by Li et al. [51].

3.2.2. Error Correction Coding

Lin et al. [52] proposed a two-layer DH scheme to enhance the EC without causing increasing computation complexity for AMBTC. For the first layer, four disjoint sets using different combinations of the mean value (AVG) and the standard deviation (VAR) are derived from the combination of secret bits and the corresponding bitmap. For the second layer, these four disjoint sets are extended by adding or subtracting 1 according to a matrix (HC (7,4)) code. To maintain reversibility, we must return the irreversible block to its previous state, which is the state after the first layer of data is embedded. Then, to losslessly recover the AMBTC-compressed images after extracting the secret bits, we use the continuity feature, the parity of pixels value, and the unique number of changed pixels in the same row to restore AVG and VAR. According to the experimental results, this method was measured to have high EC and good image quality. However, the compression rate deteriorates by using 2 bits for all pixels of the 2-bitmap. In addition, the decoded pixel uses eight types of pixels, which is differentiated from the two types of pixels of the traditional AMBTC.

Lin et al. [53] proposed a two-layer RDH method based on AMBTC applying HC (7,4). It is mainly composed of two parts: the data embedding phase, and the data extraction and image recovery phase. In the data embedding phase, the embedding method has two layers. The first layer is based on Lin et al.’s method. The second layer is based on matrix embedding with HC (7,4). In order to restore the original quantization levels and , a location map is needed in order to record some multi-solution cases. During the extract phase, it restores the original and and extracts confidential messages.

4. Performance Analysis

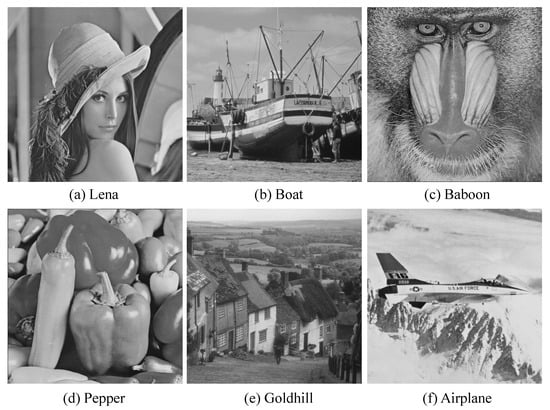

We have classified the AMBTC-based DH method so far and summarized each classification method. In this section, the performance of the proposed DH method is evaluated with six original grayscale images. The evaluation of existing methods is based on the EC and the quality of the displayed images. EC is the total number of bits embedded in AMBTC and the quality of the marked image is measured in PSNR as

The six original images [54] used in the experiment are Lena, Boat, Baboon, Peppers, Goldhill, and Airplane as shown in Figure 7. These original images must be converted into AMBTC before experimental evaluation. The hidden bits to be used in the experiment are generated by the random number generation library function provided by Matlab. The existing methods are applied to the units of trios converted to AMBTC, that is, the bitmap and two quantization levels.

Figure 7.

Original grayscale images for experiments.

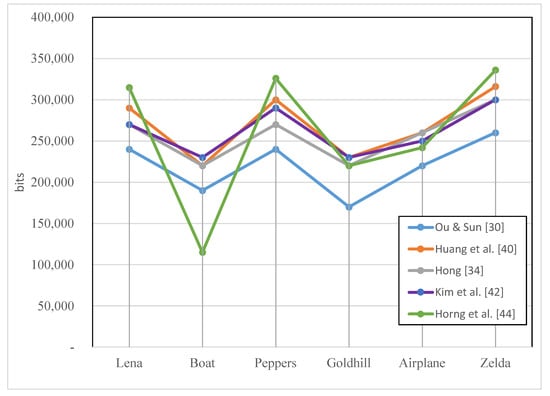

Figure 8 shows the comparison of the EC of the representative DH methods (i.e., Ou and Sun [29], Huang et al. [38], Hong [32], Kim et al. [41] and Horng et al. [43] using six images [54]. Here, EC was measured in case that the image quality was above 30 dB. The reason is that the measured EC when less than 30 dB may not be suitable for use in real systems. Although the other researches ignore this, in Figure 8, EC was measured with this criteria. Of course, even if the experimental result maintains 30 dB, it cannot be guaranteed that the image is not absolutely broken, but for the objective of the experiment, the lower limit of the image is set to 30 dB.

Figure 8.

Comparisons of EC performance among existing DH methods.

The methods in Figure 8 use the DBS method [29] commonly, which is to substitute bits of the same size in a bitmap. The merit of DBS is essential for hiding a large number of bits (1 bpp), and the image quality does not deteriorate significantly even after performing DBS, because on average 50% of the original pixel values of the block are maintained after DBS is performed.

The methods of Huang et al. [38] and Horng et al. [43], respectively, proposed a DH technique that exploits the difference between two pixels to sufficiently hide the data at the quantization level. Huang et al.’s method [38] and Horng et al.’s method [43] have average bpp of 1.3 and 1.28, respectively, and Huang et al.’s method is slightly superior. Since Ou and Sun’s method [29] hides data only with the DBS method, the data hiding rate corresponds to 1 bpp. The methods of Hong [32] and Kim et al. [41] is 1.18 bpp and 1.16 bpp, respectively, which is superior to DBS, but it is measured to be slightly inferior in performance compared to the Huang et al.’s method. AMBTC-based DH does not have enough redundant bits compared to standard grayscale images, so achieving an average of 1.2 bpp while maintaining about 30 dB is a very valuable achievement.

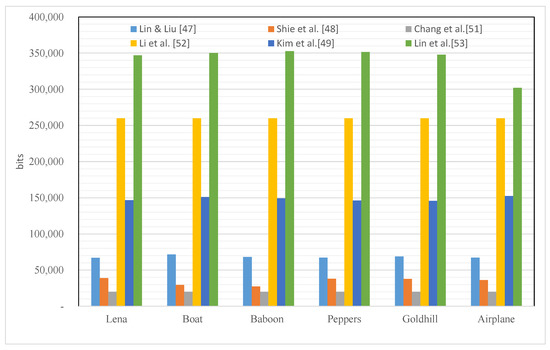

Figure 9 compares and evaluates the performance of a typical RDH method. The methods of Lin and Liu [46], Shie et al. [47], and Chang et al. [50] are AMBTC-based RDH methods that were proposed relatively early. Lin and Liu [46] and Shie et al. [47] are RDH methods using histograms, and Chang et al.’s method [50] is a method using HC (7,4). The data hiding performance is 0.08 bpp, 0.13 bpp, and 0.24 bpp, respectively. These methods show the potential of early BTC-based RDH and can be considered valuable. On the other hand, the relatively recent RDHs (Kim et al. [48], Li et al. [51], and Lin et al. [52]) range from about 0.57 bpp to about 1.3 bpp. In particular, Lin et al.’s method [52] utilizes multiple histograms, so it shows the best performance. Like the existing gray image-based RDH, it can be seen that the HS method is usefully used in the BTC-based RDH system. It is evaluated that methods capable of higher EC will be proposed through the development of a modified method of HS in the future. Meanwhile, sufficient bitmap resources are required to hide a large amount of data. For this purpose, it is a recent trend to use a method of increasing the number of pixels in the bitmap, but this is only expedient. Since the performance is improved by distorting the original method of AMBTC, the compression performance is of course badly affected.

Figure 9.

Comparisons of EC performance among existing RDH methods.

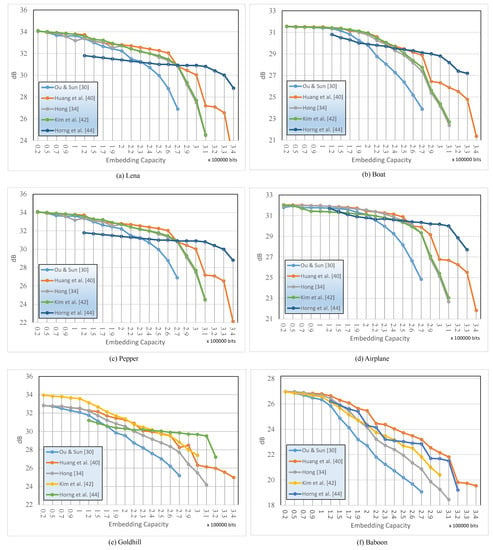

Figure 10 shows a chart where the correlation between EC and PSNR can be observed when six conventional methods are applied to six standard images. The existing five methods can see the data hiding ability through Figure 8. In Figure 10a–f, it is common that the increase in data deteriorates the image quality. Because it is accompanied by distortion of the image. Nevertheless, depending on the performance of the proposed method, the PSNR may be lowered gently or rapidly. We can observe such a basic point. In Figure 10, it can be visually judged that the method proposed by Horng is the method that best meets the two evaluation criteria with the most data. It can be observed that Huang et al.’s [38] method is the best when only the data hiding capacity is used as a standard. In the figure, if the data hiding capacity is limited to 0.2 ∼ 1.5, Horng et al.’s [43] method may not be recommended. In this case, it can be said that all existing methods are excellent. Figure 10f is an image belonging to a high-frequency image, and since the quality of the cover image itself belongs to about 27 dB, when data is hidden in this cover image, it is lowered to a maximum of about 18 dB, so it is not suitable for data hiding by BTC compression.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the performance of PSNR vs. EC.

5. Conclusions

We briefly looked at the studies and analyzed their performance using simulations after classifying the various studies on AMBTC-based DH. The cover images used in the experiment are Lena, Boat, Baboon, Peppers, Goldhill, and Airplane. The PSNRs of these cover images are 33.65, 31.57, 26.97, 34.09, 32.83, and 32.03, respectively. Therefore, hiding an amount of data while maintaining more than 30 dB can be a very difficult challenge. However, in the case of a high-frequency image such as the Baboon image, it is difficult to use it as a cover image because the image quality does not reach 30 dB after compression with BTC. With DH and RDH, the maximum data hiding performance is 1.3 bpp. However, if data is hidden by 1.3 bpp, it may not be suitable for the purpose of confidential communication or copyright protection. Existing methods can be a good alternative if existing methods are selected according to the purpose. Most of the methods proposed so far are actually modified methods used in gray images to apply the compression method. In other words, most of the methods verified in the grayscale image were applied to BTC and showed good performance. In the future, we intend to review the papers of various methods to consider future research directions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K.; methodology, C.K.; software, L.L.; validation, C.-N.Y.; formal analysis, C.-N.Y.; investigation, L.L.; resources, J.B.; data curation, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, C.K.; visualization, L.L.; supervision, C.-N.Y.; project administration, C.K.; funding acquisition, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) under Grant 108-2221-E-259-009-MY2 and 109-2221-E-259-010 and by the faculty research fund of Sejong University in 2020. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61866028.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the reviewers who reviewed this paper and the MDPI editor who edited it professionally.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DH | Data Hiding |

| RDH | Reversible Data Hiding |

| BTC | Block Truncation Coding |

| AMBTC | Absolute Moment BTC |

| DCT | Discrete Cosine Transform |

| LSB | Least Significant Bit |

| OPAP | Optimal Pixel Adjustment Process |

| HS | Histogram Shifting |

| ECC | Error Correction Code |

| DBS | Direct Bitmap Substitution |

| ith pixel of the block | |

| Mean pixel value of a block | |

| A block of common bitmap | |

| Two quantization levels of a block | |

| T | |

| Modular operator | |

| f | Extraction function as weighted sum modulo 5 |

| ⊕ | Exclusive or operator |

| H | Parity-check matrix for HC(7,4) |

| Histogram of an image, where x is a pixel | |

| M | n-bit secret message |

References

- Bender, W.; Gruhl, D.; Morimoto, N.; Lu, A. Techniques for data hiding. IBM Syst. J. 1996, 35, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitcolas, F.A.P.; Anderson, R.J.; Kuhn, M.G. Information hiding-a survey. Proc. IEEE 1999, 87, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provos, N.; Honeyman, P. Hide and seek: An introduction to steganography. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2003, 1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, A.M. Reversible watermark using the difference expansion of a generalized integer transform. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, M.U.; Sharma, G.; Tekalp, A.M.; Saber, E. Lossless generalized-LSB data embedding. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2005, 14, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Z.; Shi, Y.Q.; Ansari, N.; Su, W. Reversible data hiding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2006, 16, 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.T.; Wu, J.L. Hidden digital watermarks in images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1999, 8, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dang, P.P.; Chau, P.M. Image encryption for secure Internet multimedia applications. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2000, 46, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.F.; Jajodia, S. Exploring steganography: Seeing the unseen. Computer 1998, 31, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.J.; Petitcolas, F.A.P. On the limits of steganography. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 1998, 16, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrich, J.; Goljan, M.; Du, R. Detecting LSB steganography in color, and gray-scale images. IEEE Multimed. 2001, 8, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C.; Arcangelo, C.; Alfredo, D.S.; Francesco, P.; Pizzolante, R. Compression-based steganography. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e5322. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, I.J.; Kilian, J.; Leighton, F.T.; Shamoon, T. Secure spread spectrum watermarking for multimedia. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1997, 6, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, F.; Kutter, M. Multimedia watermarking techniques. Proc. IEEE 1999, 87, 1079–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, A.D. Steganalysis of LSB matching in grayscale images. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2005, 12, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielikainen, J. LSB matching revisited. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2006, 13, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.S.; Gutub, A. Improving data hiding within colour images using hue component of HSV colour space. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.D.; Chen, C.F. A robust DCT-based watermarking for copyright protection. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2000, 46, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solachidis, V.; Pitas, L. Circularly symmetric watermark embedding in 2-D DFT domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2001, 10, 1741–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.S.; Gutub, A. Novel embedding secrecy within images utilizing an improved interpolation-based reversible data hiding scheme. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, E.; Mitchell, O. Image compression using block truncation coding. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1979, 27, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelaar, G.C.; Lagendijk, R.L. Optimal differential energy watermarking of DCT encoded images and video. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2001, 10, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lema, M.; Mitchell, O. Absolute moment block truncation coding and its application to color images. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1984, 32, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Hwang, M.S. An improved reversible data hiding for block truncation coding compressed images. IETE Tech. Rev. 2020, 37, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.C.; Chang, C.C. Using a simple and fast image compression algorithm to hide secret information. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2006, 28, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Efficient steganographic embedding by exploiting modification direction. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2006, 10, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J. Reversible data embedding using a difference expansion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2003, 13, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamming, R.W. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1950, 29, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, D.; Sun, W. High payload image steganography with minimum distortion based on absolute moment block truncation coding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015, 74, 9117–9139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chi, K.Y. Cloud image watermarking: High quality data hiding, and blind decoding scheme based on block truncation coding. Multimed. Syst. 2019, 25, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Sikka, G.; Verma, H.K. An AMBTC compression-based data hiding scheme using pixel value adjusting strategy. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 29, 1801–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W. Efficient data hiding based on block truncation coding using pixel pair matching technique. Symmetry 2018, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Chen, T.S. A novel data embedding method using adaptive pixel pair matching. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2012, 7, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Li, Y.; Weng, S. A difference matching technique for data embedment based on absolute moment block truncation coding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 13987–14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.D.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.C. High-precision authentication scheme based on matrix encoding for AMBTC—Compressed images. Symmetry 2019, 11, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Data hiding based on BTC using EMD. J. Inst. Internet, Broadcast. Commun. (IIBC) 2014, 14, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.F.; Chang, C.C.; Li, G.L. A data hiding scheme based on turtle-shell for AMBTC compressed images. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 2554–2575. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.H.; Chang, C.C.; Chen, Y.H. Hybrid secret hiding schemes based on absolute moment block truncation coding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 6159–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Shin, D.; Yang, C.N. High capacity data hiding with absolute moment block truncation codingimage based on interpolation. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Chang, C.C. A high payload steganographic scheme for compressed images with Hamming code. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2016, 18, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Shin, D.K.; Yang, C.N.; Leng, L. Hybrid data hiding based on AMBTC using enhanced Hamming code. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kim, D.S.; Jung, K.H. Enhanced AMBTC based data hiding method using hamming distance and pixel value differencing. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 47, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.; Chang, C.; Li, G. Steganography using quotient value differencing and LSB substitution for AMBTC compressed Images. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 129347–129358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Yang, C.N.; Leng, L. High-capacity data hiding for ABTC-EQ based compressed image. Electronics 2020, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Z.; Lin, C.F.; Lin, J.C. Hiding data in images by optimal moderately significant-bit replacement. IEE Electron. Lett. 2000, 36, 2069–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Liu, X. A reversible data hiding scheme for block truncation compressions based on Histogram modification. In Proceedings of the 2012 Sixth International Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computing, Kitakyushu, Japan, 25–28 August 2012; pp. 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shie, S.; Jiang, J.; Su, Y.; Chang, W. An improved steganographic scheme implemented on the compression domain of image using BTC and Histogram modification. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops (WAINA), Krakow, Poland, 16–18 May 2018; pp. 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Shin, D.; Leng, L.; Yang, C.N. Lossless data hiding for absolute moment block truncation coding using histogram modification. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2018, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.F.; Tang, L.L. High-capacity reversible data hiding in AMBTC-compressed images. Int. J. Digit Content Technol. Appl. 2012, 6, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.I.; Hu, C.Y.; Chen, L.W.; Lu, C.C. High capacity reversible data hiding scheme based on residual histogram shifting for block truncation coding. Signal Process. 2015, 108, 376–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Lu, Z.M.; Su, Y.X. Reversible data hiding for BTC-compressed images based on bitplane flipping and histogram shifting of mean tables. Inf. Technol. J. 2011, 10, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, C.-C.; Lin, J.; Chang, C.-C. Reversible data hiding for AMBTC compressed images based on matrix and Hamming coding. Electronics 2021, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Weng, S.; Zhang, T.; Ou, B.; Chang, C. Two-layer reversible data hiding based on AMBTC image with (7, 4) Hamming code. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21534–21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Images. 2021. Available online: http://sipi.usc.edu/database/ (accessed on 26 September 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).