Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Paper Contributions

1.4. Paper Organization

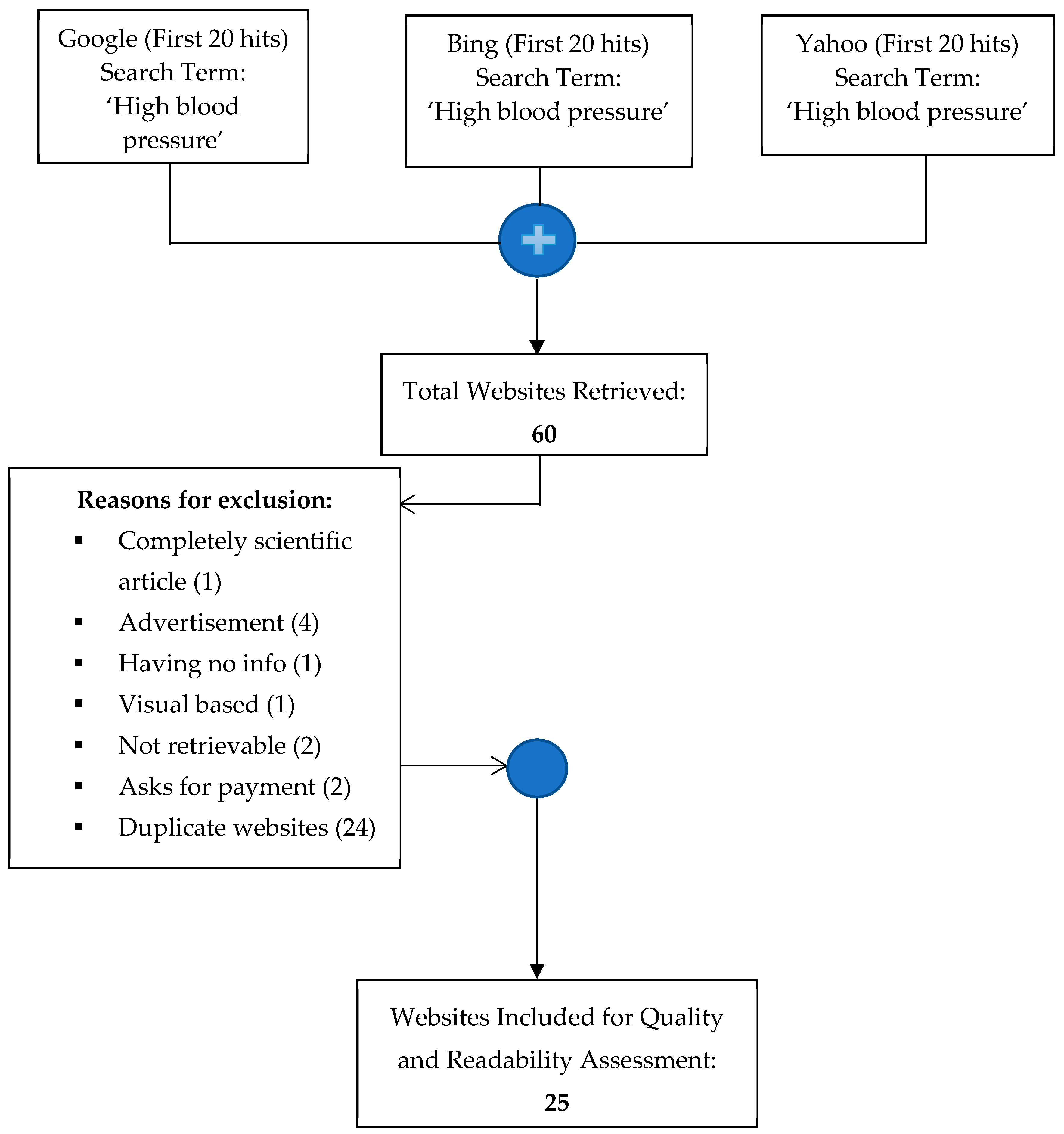

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of Search Engines and Web Browser

2.2. Websites Selection for the Study

2.3. Quality Assessment Instrument

2.4. Readability Assessment

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Websites Evaluation

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group 1: Health Professional

3.1.1. High Scoring Websites

3.1.2. Quality of Included URLs

- A.

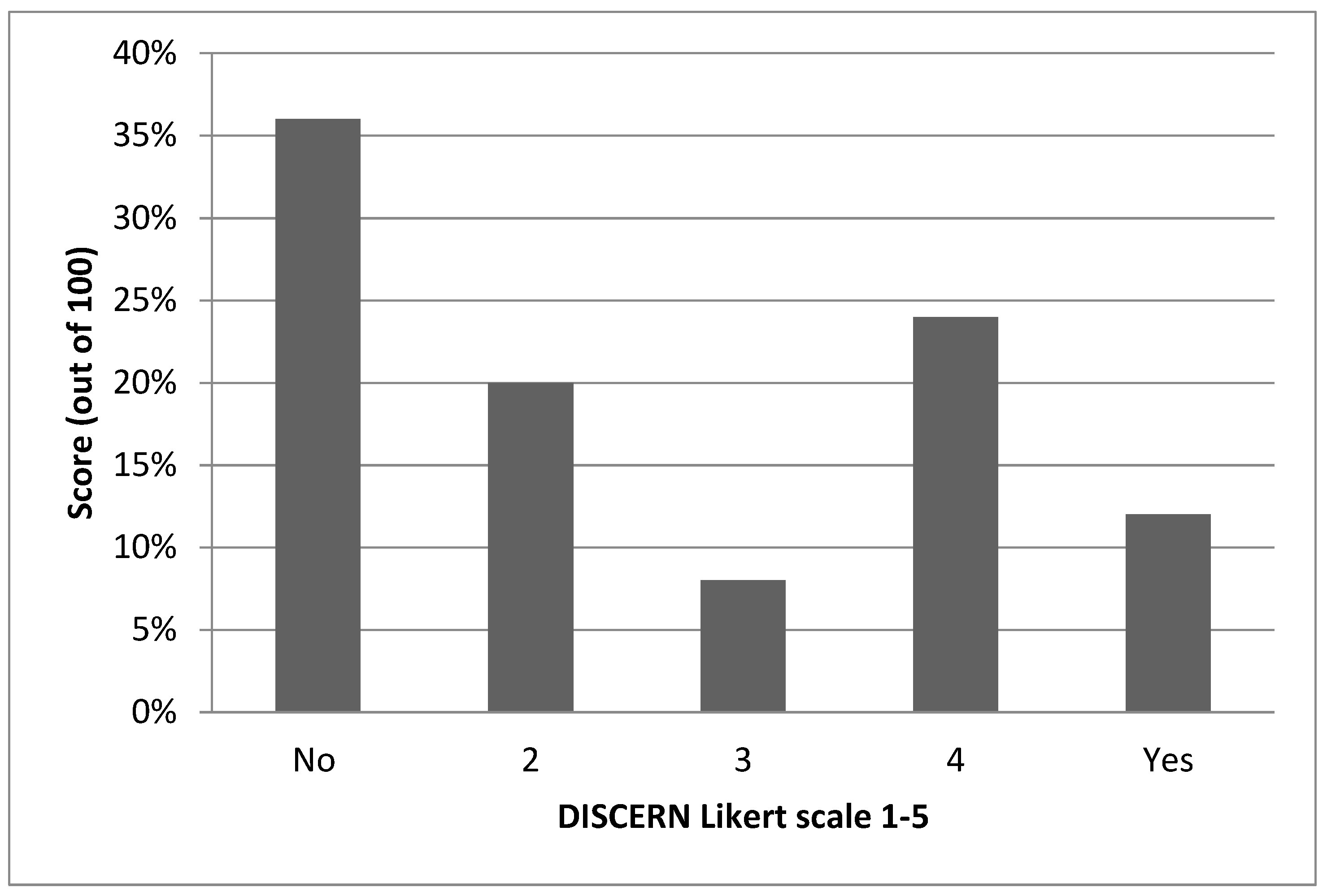

- DISCERN’s Part-I (Question 1–8)

- B.

- DISCERN’s Part-II (Question 9–15)

- C.

- DISCERN’s Part-III (Question 16)

3.1.3. DISCERN Indicator: Clarity of Sources

3.1.4. DISCERN Indicator: Additional Source of Information

3.2. Group 2: Lay Subjects

3.2.1. High Scoring Websites

3.2.2. Quality of Included URLs

- A.

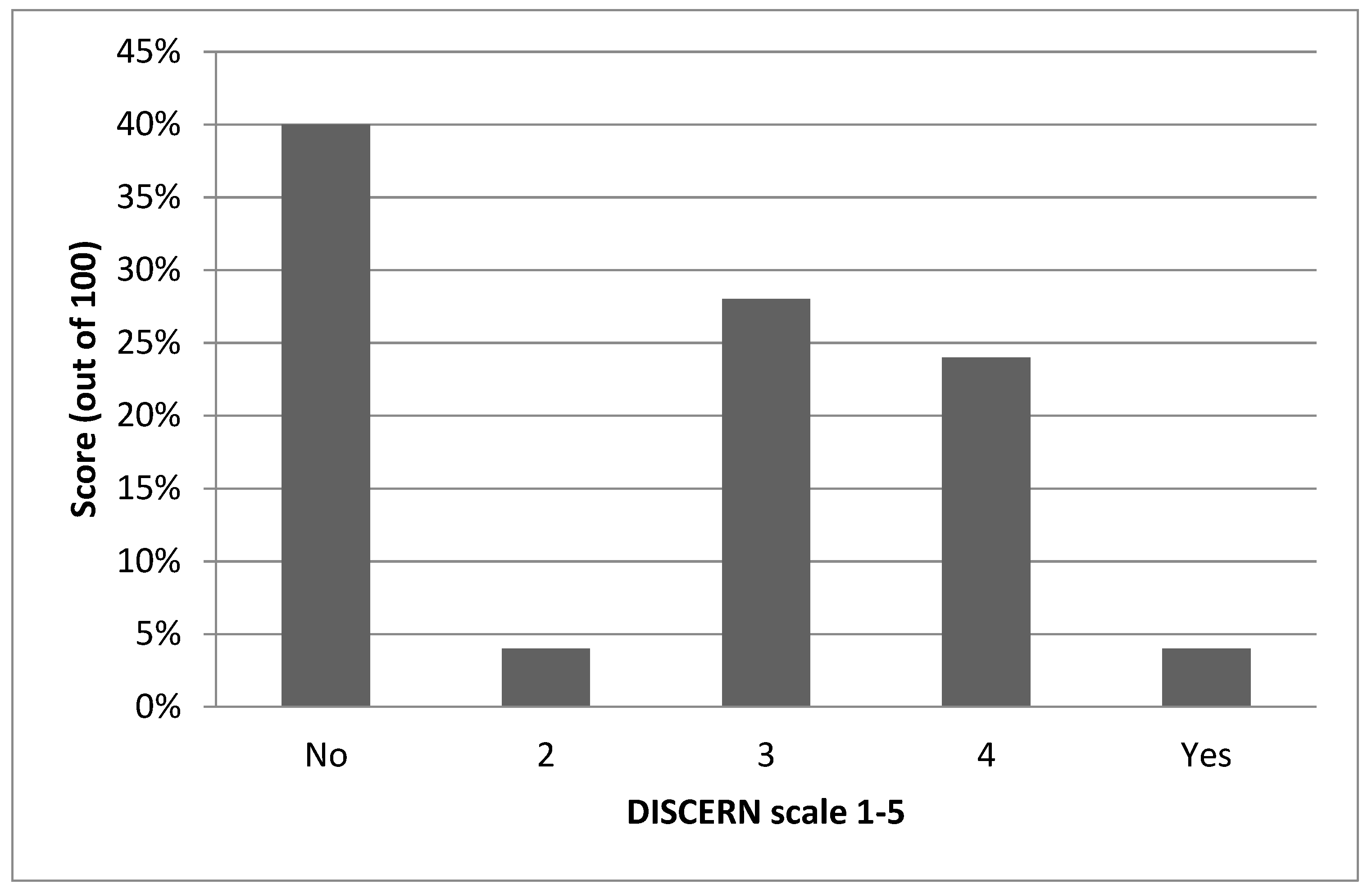

- DISCERN’s Part-I (Questions 1–8)

- B.

- DISCERN’s Part-II (Questions 9–15):

- C.

- DISCERN’s Part-III (Question 16):

3.2.3. DISCERN Indicator: Clarity of Sources

3.2.4. DISCERN Indicator: Additional Source of Information

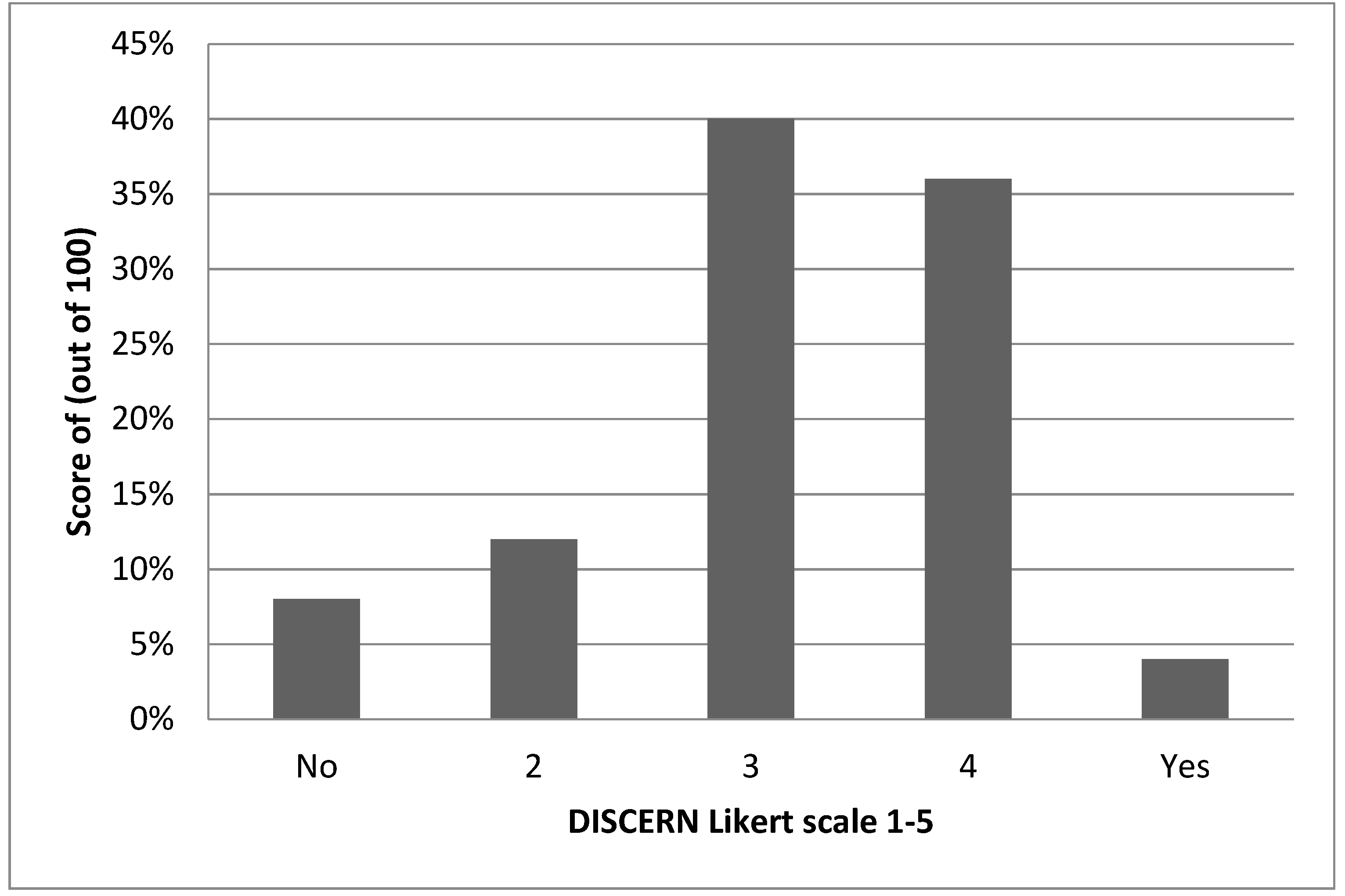

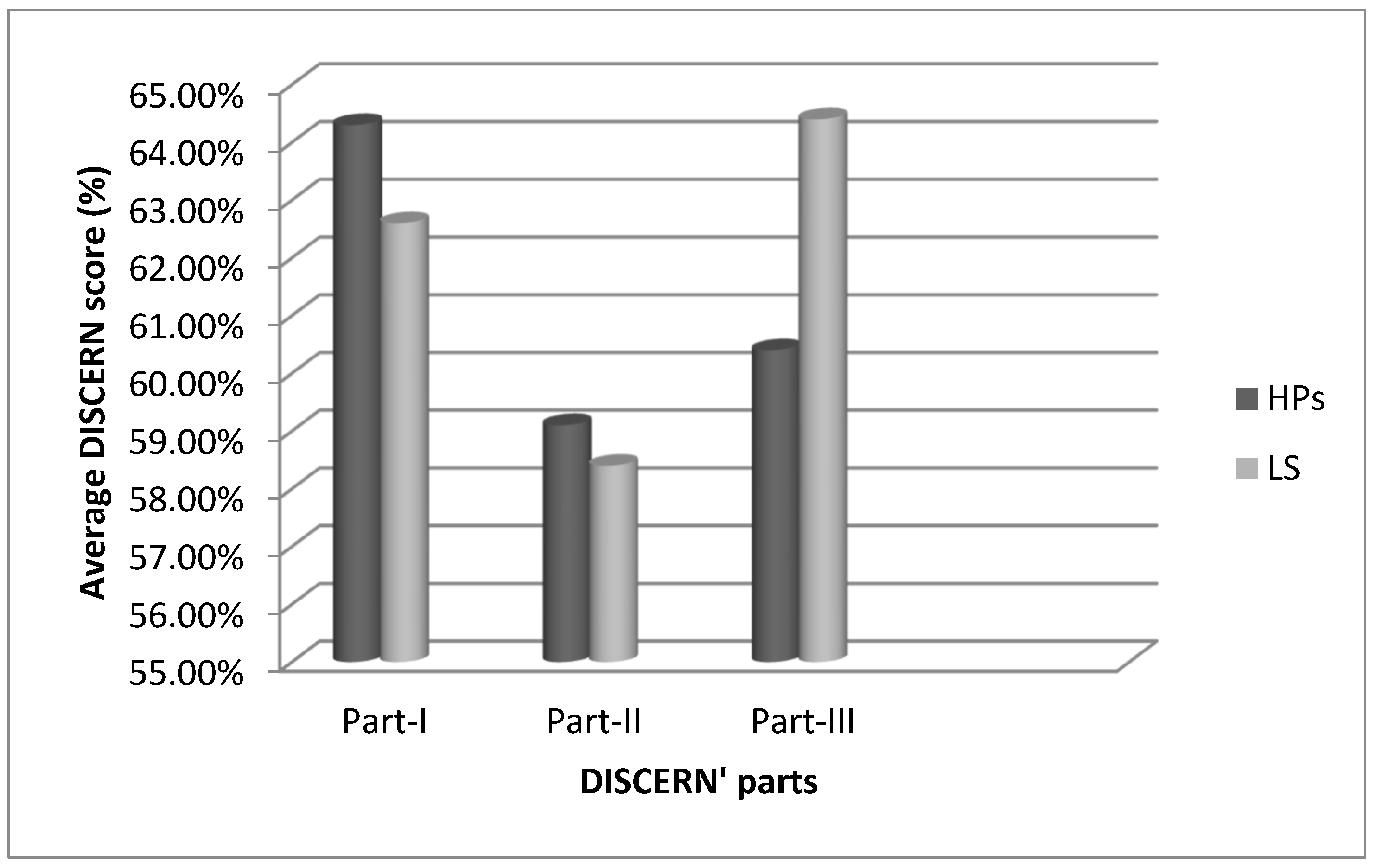

3.3. Results Comparison of Both Groups (HPs & LS)

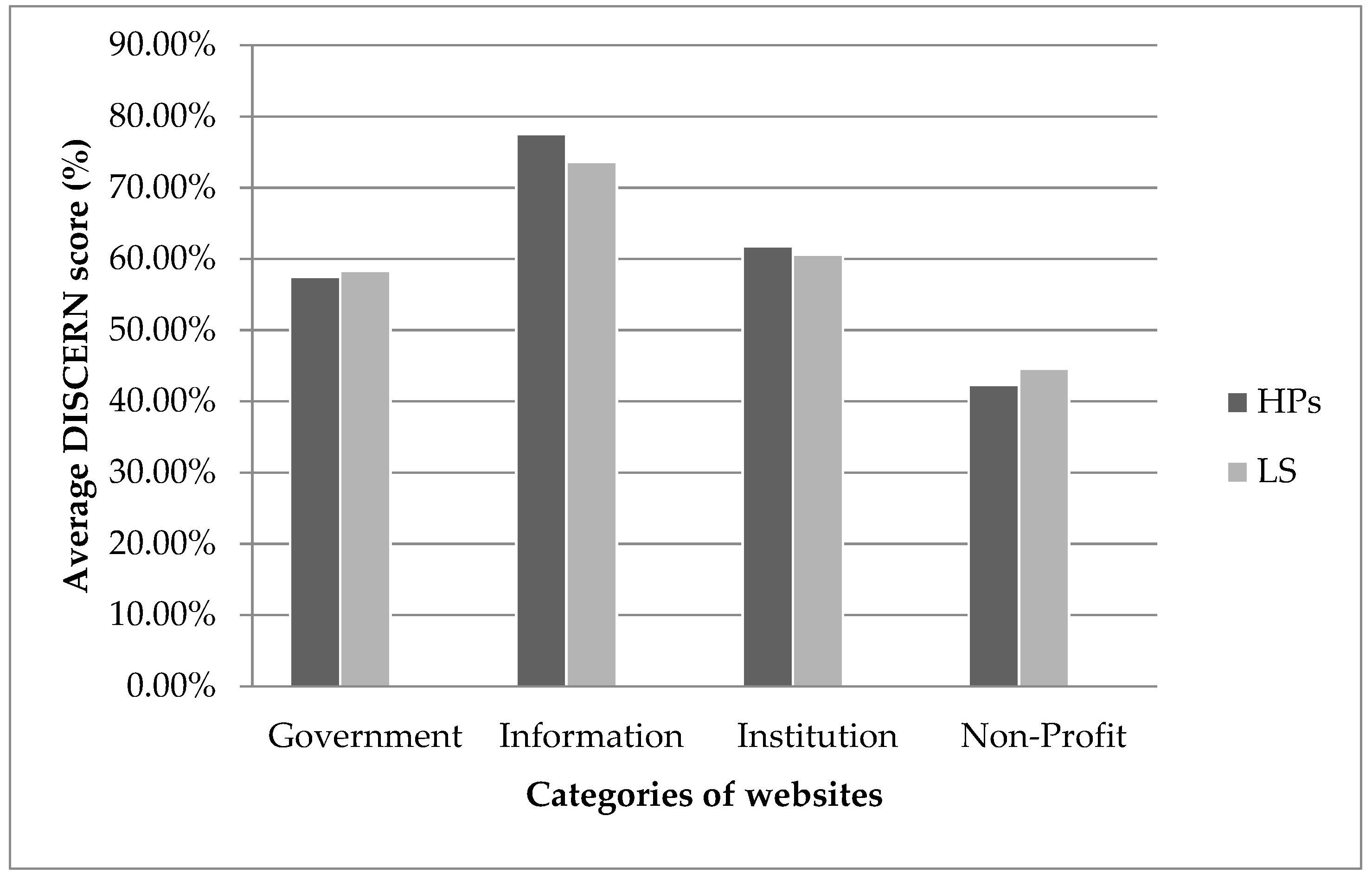

3.4. Website’s Category Wise Comparison of Both Groups (HPs and LS)

3.5. Statistical Analysis

3.6. Readability Level of All Included Websites

4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section 1: Reliability of Publication |

| Q1: Are the aims clear? Q2: Does it achieve its aims? Q3: Is it relevant? Q4: Is it clear what sources of information were used to compile the publication (other than the author or producer)? Q5: Is it clear when the information used to reported in the publication was produced? Q6: Is it balanced and unbiased? Q7: Does it provide details of additional sources of support and information? Q8: Does it refer to areas of uncertainty? |

| Rating: No: give 1 point Partially: give 2, 3 or 4 points Yes: give 5 points |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

| Section 2: Quality of information on treatment choices |

| Q9: Does it describe how each treatment works? Q10: Does it describe the benefits of each treatment? Q11: Does it describe the risks of each treatment? Q12: Does it describe what would happen if no treatment is used? Q13: Does it describe how the treatment choices affect overall quality of life? Q14: Is it clear there may be more than one possible treatment choice? Q15: Does it provide support for shared decision-making? |

| Rating: No: give 1 point Partially: give 2, 3 or 4 points Yes: give 5 points |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

| Section 3: Overall rating of the publication |

| Q16: On the basis of the answers to all of the above questions, rate the overall quality of the publication as a source of information about treatment choices. |

| Rating: Low: give 1 point (serious extensive deficiencies Moderate: give 2, 3 or 4 points (potentially important but not serious deficiencies) Yes: give 5 points (minimum deficiencies) |

References

- World Health Organization. Non Communicable Disease WHO Experts Warn Against Inadequate Prevention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mirrezaie, S.M.; Jalil, S.K.; Mirrezaie, N. The Quality of Websites Related to Hypertension in Iranian Internet Space. Int. J. Health Stud. 2015, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.K.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Islam, S.; Gupta, R.; Avezum, A.; Bahonar, A.; Chifamba, J.; Dagenais, G.; Diaz, R.; et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. Jama 2013, 310, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.; Shah, Q.; Shah, A.J. The burden and high prevalence of hypertension in Pakistani adolescents: A meta-analysis of the published studies. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; Aryee, M.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diviani, N.; van den Putte, B.; Giani, S.; van Weert, J.C. Low health literacy and evaluation of online health information: A systematic review of the literature. J. Medical. Int. Res. 2015, 17, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Internet World Stats – Usage and Populations Statistics. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Cerminara, C.N.; Malhany, E. Website and Headache: Assessment of the Information Quality Using the DISCERN Tool. J. Neurol. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dr Google Will See You Now. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2019/03/10/google-sifting-one-billion-health-questions-day/ (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Reynolds, M.; Hoi, A.; Buchanan, R.R.C. Assessing the quality, reliability and readability of online health information regarding systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2018, 27, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More People Search for Health Online. Available online: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3077086/t/more-people-search-health-online/#.W8o4kkszbIU (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Europeans Becoming Enthusiastic Users of Online Health Information: Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/europeans-becoming-enthusiastic-users-online-health-information. (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Patel, P.P.; Hoppe, I.C.; Ahuja, N.K.; Ciminello, F.S. Analysis of Comprehensibility of Patient Information Regarding Complex Craniofacial Conditions. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2011, 22, 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit, B.F.; Koca, T.T.; Akaltun, M.S. Quality and Readability of Online Information on Ankylosing Spondylitis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 3269–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Lo, B.; Pollack, L.; Donelan, K.; Catania, J.; Lee, K.; Zapert, K.; Turner, R. The impact of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: National US survey among 1.050 US physicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N.; Varnam, R.; Rogers, A.; Roland, M. What predicts patients’ interest in the Internet as a health resource in primary care in England? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2003, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, J.J.; Steinwachs, D.; Rubin, H.R. Conceptual framework for a new tool for evaluating the quality of diabetes consumer-information Web sites. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, D. The DISCERN Handbook: Quality Criteria for Consumer Health Information on Treatment Choices. Available online: http://www.discern.org.uk (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Friedman, D.B.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Arocha, J.F. Health literacy and the World Wide Web: Comparing the readability of leading incident cancers on the Internet. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2006, 31, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, J.F.; Neiger, B.L.; Thackeray, R. Planning, Implementing & Evaluating Health Promotion Programs: A Primer; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meleo-Erwin, Z.; Basch, C.; Fera, J.; Ethan, D.; Garcia, P. Readability of Online Patient-Based Information on Bariatric Surgery. Health Promot. Perspect. 2019, 9, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groller, K.D. Systematic Review of Patient Education Practices in Weight Loss Surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansberry, D.R.; Agarwal, N.; Shah, R.; Schmitt, P.J.; Baredes, S.; Setzen, M.; Carmel, P.W.; Prestigiacomo, C.J.; Liu, J.K.; Eloy, J.A. Analysis of the Readability of Patient Education Materials from Surgical Subspecialties. Laryngoscope 2013, 124, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G.; Powell, J.; Kuss, O.; Sa, E.R. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: A systematic review. Jama 2002, 287, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, T.M.; Khan, M.S.; Victory, L.; Mehmood, A.; Cooke, F. An assessment of the quality and content of information on diverticulitis on the Internet. Surgeon 2018, 16, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, N.; Ghezzi, P. Quality of online information on breast cancer treatment options. Breast 2018, 37, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerminara, C.; Santarone, M.E.; Casarelli, L.; Curatolo, P.; El Malhany, N. Use of the DISCERN tool for evaluating web searches in childhood epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014, 41, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaicker, J.; Dang, W.; Mondal, T. Assessing the quality and reliability of health information on ERCP using the DISCERN instrument. Health Care Curr. Rev. 2013, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipser, J.C.; Dewing, S.; Stein, D.J. A systematic review of the quality of information on the treatment of anxiety disorders on the Internet. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2007, 9, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, M.G.; Joury, A.U. Quality, Readability, and Understandability of Internet-Based Information on Cataract. Health Technol. 2019, 9, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, C.; Kumar, S. Quality and Readability of Online Patient Education Information and the Parents Comprehension for Childhood Depression. J. Health Med Inform. 2016, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saithna, A.; Ajayi, O.O.; Davis, E.T. The Quality of Internet Sites Providing Information Relating to Hip Resurfacing. Surgeon 2008, 6, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Giorgi, M.R.M.; de Groot, O.S.D.; Dikkers, F.G. Quality and readability assessment of websites related to recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 2293–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joury, A.; Joraid, A.; Alqahtani, F.; Alghamdi, A.; Batwa, A.; Pines, J.M. The Variation in Quality and Content of Patient-Focused Health Information on the Internet for Otitis Media. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 44, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.S.; Subramani, S.; Veerapan, S.; Khan, S.A. Evaluation of Online Health Information on Clubfoot Using the DISCERN Tool. J. Pediatric Orthop. B 2014, 23, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Moore, J.L.; Steege, L.M.; Koopman, R.J.; Belden, J.L.; Canfield, S.M.; Meadows, S.E.; Elliott, S.G.; Kim, M.S. Health information needs, sources, and barriers of primary care patients to achieve patient-centered care: A literature review. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 992–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Hypertension. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M. Using the Internet: Skill related problems in users’ online behavior. Interact. Comput. 2009, 21, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. How Do Consumers Search for and Appraise Health Information on the World Wide Web? Qualitative Study Using Focus Groups, Usability Tests, and in-Depth Interviews. BMJ 2002, 324, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabeel, K.L.; Russomanno, J.; Oelschlegel, S.; Tester, E.; Heidel, R.E. Computerized versus hand-scored health literacy tools: A comparison of Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) and Flesch-Kincaid in printed patient education materials. J. Med Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2018, 106, 38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabharwal, S.; Badarudeen, S.; Kunju, S.U. Readability of online patient education materials from the AAOS web site. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protheroe, J.; Estacio, E.V.; Saidy-Khan, S. Patient Information Materials in General Practices and Promotion of Health Literacy: An Observational Study of Their Effectiveness. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e192–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Yamat, H. Testing the Validity and Reliability of the “Learn, Pick, Flip, Check, Reward” (LPFCR) Card Game in Homophone Comprehension. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.M.; Wah, Y.B. Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov, lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. J. Stat. Modeling Anal. 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, D. Fundamental Statistics for Social Research: Step-By-Step Calculations and Computer Techniques Using SPSS for Windows; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Category of Website | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Information | 36% |

| Government | 24% |

| Institution | 24% |

| Non-Profit Organization | 16% |

| DISCERN Score | Out of 100 | Quality Level |

|---|---|---|

| 64–80 | 80% & above | Excellent |

| 52–63 | 65% to 79% | Good |

| 41–51 | 51% to 64% | Fair |

| 30–40 | 37% to 50% | Poor |

| 16–29 | 20% to 36% | Very Poor |

| Kappa Statistics | Strength of Agreement |

|---|---|

| <0.00 | Poor |

| 0.00–0.20 | Slight |

| 0.21–0.40 | Fair |

| 0.41–0.60 | Moderate |

| 0.61–0.80 | Substantial |

| 0.81–1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| N = 25 | Very Poor (Score = 16–29) (20% to 36%) | Poor (Score: 30–40) (37% to 50%) | Fair (Score: 41–51) (51% to 64%) | Good (Score: 52–63) (65 % to 79%) | Excellent (score: 64–80) (80%&above) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISCERN: Part-I (Q1 to Q8) Reliability of Publication | 2(8%) | 2(8%) | 10(40%) | 6 (24%) | 5 (20%) |

| DISCERN: Part-II (Q9 to Q15) Quality of Information on Treatment | 5(20%) | 2(8%) | 9(36%) | 4 (16%) | 5 (20%) |

| DISCERN: Part-III (Q16) Overall Quality | 2(8%) | 5(20%) | 8(32%) | 5(20%) | 5(20%) |

| N = 25 | Very Poor (Score = 16–29) (20% to 36%) | Poor (Score:30–40) (37% to 50%) | Fair (Score: 41–51) (51% to 64%) | Good (Score: 52–63) (65% to 79%) | Excellent (Score: 64–80) (80% & above) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISCERN: Part-I (Q1 to Q8) Reliability of Publication | 2(8%) | 2(8%) | 10(40%) | 6 (24%) | 5 (20%) |

| DISCERN: Part-II (Q9 to Q15) Quality of Information on Treatment | 1(4%) | 8(32%) | 5(20%) | 8(32%) | 3 (12%) |

| DISCERN: Part-III(Q16) Overall Quality | 1(4%) | 4(16%) | 9(36%) | 5(20%) | 6(24%) |

| Category of Websites | t-Value | p-Value at p < 0.05 |

|---|---|---|

| Information | 1.80123 | 0.040863 |

| Government | −0.1165 | 0.908034 |

| Institution | −0.52381 | 0.60426 |

| Non-profit organization | −0.70927 | 0.483292 |

| Category | No. of Websites | FRES | AGL | p-Value at p < 0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | 6 | 64.4 ± 8.2 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 0.908034 |

| Information | 9 | 48.7± 10.8 | 10.5 ± 1.9 | 0.040863 |

| Institution | 4 | 60.8 ± 6.3 | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 0.60426 |

| Non-Profit | 6 | 65.8 ± 5.7 | 7.8 ± 1.3 | 0.483292 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahir, M.; Usman, M.; Muhammad, F.; Rehman, S.u.; Khan, I.; Idrees, M.; Irfan, M.; Glowacz, A. Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3214. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093214

Tahir M, Usman M, Muhammad F, Rehman Su, Khan I, Idrees M, Irfan M, Glowacz A. Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(9):3214. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093214

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahir, Muhammad, Muhammad Usman, Fazal Muhammad, Shams ur Rehman, Imran Khan, Muhammad Idrees, Muhammad Irfan, and Adam Glowacz. 2020. "Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools" Applied Sciences 10, no. 9: 3214. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093214

APA StyleTahir, M., Usman, M., Muhammad, F., Rehman, S. u., Khan, I., Idrees, M., Irfan, M., & Glowacz, A. (2020). Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools. Applied Sciences, 10(9), 3214. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093214