Abstract

This paper investigates for the first time how the implementation of semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA)-based devices in photonic networks can negatively impact the integrity of two-dimensional wavelength-hopping time-spreading (2D-WH/TS) optical code-division multiple access (OCDMA) codes based on multi-wavelength picosecond code carriers. It is demonstrated and confirmed by simulations that the influence of an SOA under driving currents of 50 mA to 250 mA causes a 0.08 to 0.8 nm multi-wavelength picosecond code carriers’ wavelength redshift. The results obtained are then used to calculate the degradation of OCDMA system performance in terms of the probability of error Pe and the decrease in the number of simultaneous users. It is shown that, when the SOA-induced 0.8 nm code carriers redshift becomes equal to the code carries wavelength channel spacing, the (8,53)-OCDMA system performs only as a (7,53)-OCDMA system, and the number of simultaneous users drops from 14 to 10 or 84 to 74 with the forward error correction (FEC) Pe of 10−9, respectively. The impact of the 0.8 nm redshift is then shown on a (4,53)-OCDMA system, where it causes a drop in the number of simultaneous users from 4 to 3 or 37 to 24 with the FEC Pe of 10−9, respectively.

1. Introduction

Incoherent optical code-division multiple access (OCDMA) is a promising multiplexing technique known for its soft blocking capabilities that allows a trade-off between the system bit-error-rate (BER) and number of users [1]. To ensure the optimal operation of an OCDMA system, it is necessary to maintain the integrity and fidelity of optical codes during system operation. For instance, the use of two-dimensional (2D) wavelength-hopping time-spreading (WH/TS) incoherent OCDMA with implemented carrier-hopping prime code (CHPC) [2] (a class of 2D asynchronous codes that support wavelength hopping within time spreading over the Galois field of prime numbers with zero autocorrelation side-lobes and periodic cross correlation functions of at most one) will ensure minimal multiple-access interference. The code offers good cardinality and supports a large number of simultaneous users. To further improve the code scalability, 2D-WH/TS coding uses a set of wavelengths as the code carries with a temporal duration of a few picoseconds [3].

In past decades, semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs) were developed and demonstrated to support different tasks and functionalities in optical systems, networks, and applications including data centres [4,5,6,7]. A great deal of switching architectures utilizing SOAs in different configurations such as 2 × 2 multi-cascaded switch fabrics, cross-point matrices, for broadcast and select, wavelength selection [8], and DeMux operation [9] have already been successfully demonstrated.

The severity of gain recovery time on 2D-WH/TS OCDMA systems using SOAs is evident even at low data rates [10]. This is because of the nature of the code carriers’ time-spreading. The code carriers are spread with different time delays when forming a unique code signature for each user. The SOA’s response time to incoming code is related to carrier lifetime, which in turn determines the SOA gain recovery [11]. A slow SOA gain recovery time poses a stringent limitation on the choices of the 2D-WH/TS code spreading, thus limiting the overall system scalability, including the number of simultaneous users. For the sake of illustration, even a 2.5 Gbit/s OCDMA system, if using a temporal code carriers’ separation of 25 ps (i.e., 40 OCDMA GHz/s chip rate), will experience the equivalent SOA limitations of a 40 Gbit/s on-off keying (OOK) system.

Many techniques have been developed and demonstrated to address and improve the gain recovery time of SOAs [11,12] and these techniques fall into three categories. In the first category, a continuous wave beam is utilized to saturate the SOA at the operating wavelength, which lies in the SOA’s spectral gain region or near the transparency point. The second method comprises the use of quantum wells or quantum dots semiconductors [11]. The third technique utilizes the SOA’s amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) when driving the SOA with a high bias current into saturation. In [12], this method was used to reduce the gain recovery time from 200 ps down to 10 ps with the caveat that signal quality margins were somewhat sacrificed in situations where the SOA was followed by spectral slicing [13]. As the 2D-WH/TS systems can deploy both SOAs and spectral slicing, more investigations are required.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the impact of SOA-induced redshift on multi wavelength picosecond code carriers under different bias conditions is investigated, experimentally demonstrated, and then confirmed by simulations. In Section 3, the impact of the SOA operating under high bias current/gain conditions is demonstrated on the 2D-WH/TS OCDMA code integrity. The overall performance (the probability of error and the maximum number of simultaneous users) of two different 2D-WH/TS OCDMA systems deploying the SOA is calculated. The results obtained are discussed in Section 4 and then summarized in the Conclusion.

2. Impact of SOA-Based Devices Deployed in Fiber Link on Multi-Wavelength Picosecond Code Carriers

In a 2D-WH/TS OCDMA system, each user’s data are carried by a unique code. Each code requires a unique time-spreading of wavelengths (i.e., code carriers) over a bit period. The temporal separation of code carriers can be anywhere from a few to several hundreds of picoseconds and depends on the design parameters and the targeted number of simultaneous users [1]. SOA-based optical devices can be implemented in OCDMA systems to play an important role [3,13,14]. However incorrect implementation may have undesirable effects on the system performance. The subsequent investigation will demonstrate how the use of an SOA under different driving conditions influences OCDMA code carriers and affects the code integrity.

2.1. Description of Experimental Setup

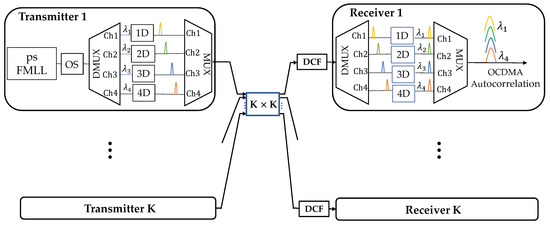

The experimental setup for the above investigation is shown in Figure 1. Here, an optical clock of wavelength of 1547 nm, generated by an erbium doped fiber mode locked laser (FMLL) manufactured by PriTel, Inc. (Naperville, IL, USA), has a linewidth of 1.4 nm. The optical clock is driven by an RF synthesizer (Agilent E8257D) at 2.5 GHz. The optical clock pulses then enter an optical supercontinuum (OS) generator, which consists of a 25 dBm erbium doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) and an approximately 1 km long dispersion decreasing fiber, thus producing a 3.2 nm wide optical supercontinuum in the spectral region from 1550 to 1553.2 nm. The 2D-WH/TS code is then generated by an encoder comprising of a 1 × 4 DWDM de-multiplexer (DMUX), four adjustable fiber optical delay lines, and a 4 × 1 DWDM multiplexer (MUX). Both MUX and DMUX have a channel spacing of 100 GHz (i.e., 0.8 nm). The resulting pulse-width at the MUX output is 7 ps at Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM). The DMUX spectrally slices the optical supercontinuum into four wavelengths (to be used as code carriers), = 1550.12 nm, = 1550.92 nm, = 1551.72 nm, and = 1552.52 nm. The wavelength separation corresponds to a 100 GHz channel spacing (ITU channels CH34 to CH31). After being appropriately delayed by optical delay lines, the individual code carriers are then recombined by a MUX to form the desired 2D-WH/TS code. The generated code then passes through a 16 km long SMF-28 optical fiber followed by a 2.5 km long matched chromatic dispersion compensating fiber (DCF) module, thus forming an 18.5 km chromatic-dispersion compensated (CDC) fiber link. The SMF-28 fiber has its group velocity dispersion parameter (GVD) /km. The 2D-WH/TS OCDMA encoder’s delay lines, D1, D2, D3, and D4 (see Figure 1), were set to generate 1, 6, 11, and 16 chip delays, respectively. An optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) (Agilent 86146B) with 0.06 nm resolution was used in all measurements.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup with illustration of two-dimensional wavelength-hopping time-spreading (2D-WH/TS) code carriers in frequency (FD, top) and time (TD, bottom) domain, respectively. TD—time domain, FD—frequency domain, ps FMLL—picosecond fiber mode locked laser, OS—optical supercontinuum, DMUX—de-multiplexer, MUX—multiplexer, SOA—semiconductor optical amplifier, DCF—chromatic dispersion compensating fiber.

It should be noted that a 1 chip delay is defined as Tbit /N, where Tbit is a bit period and N is the number of chips. Here, Tbit/N = 400/53, i.e., ~7.5 ps/chip (~133 GHz chip rate). The encoder thus generates a 2D-WH/TS code (1-, 6-, 11-, 16-) having a code carriers’ temporal separation of 30 ps < t (where t is the gain recovery time of the SOA). This means that the SOA-based device does not have enough time for full gain recovery. Similarly, a matched decoder was set to (16-, 11-, 6-, 1-). These settings will guarantee the arrival of all four wavelengths code carriers to arrive at the OCDMA decoder’s output at the same time. This enables the formation of an OCDMA autocorrelation peak of the code weight w = 4.

The impact of the SOA under different driving conditions on code carriers will be investigated next.

2.2. Investigation of 2D-WH/TS OCDMA Code Carriers’ Distortion under Different SOA Driving Conditions

The 2D-WH/TS OCDMA code carriers’ distortion was explored for SOA bias currents of 7 mA, 80 mA, and 250 mA, which provide a gain of 6 dB, 12 dB, and 24 dB, respectively. For this investigation, we used a Kamelian small gain SOA (OPA-20-N-C-FA) with a max gain of 24 dB, saturation output of 9 dBm, and polarisation dependency of 0.6 dBm [15]. The ASE power level was −26 dBm, a slightly higher value when compared with its counterparts made by Thorlabs and InPhenix Inc. (Livermore, CA, USA) when biased at 500 mA [16,17].

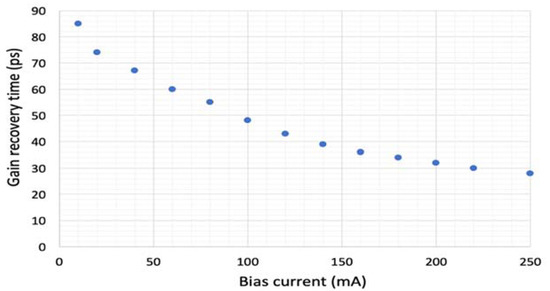

At the start, the SOA gain recovery time was measured using the technique described in [18]. The results are shown in Figure 2. The shortest measured value 28 ps corresponds to a 250 mA driving current.

Figure 2.

SOA’s gain recovery time against the bias current.

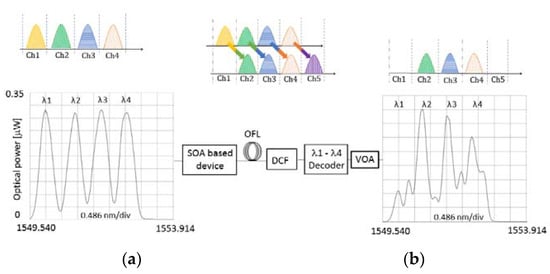

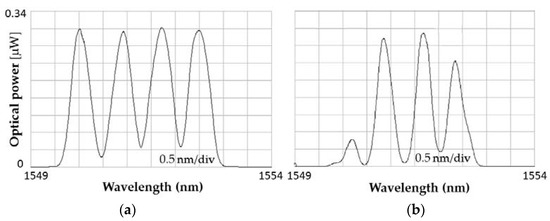

The code integrity was first observed using an optical spectrum analyzer by comparing the code spectrum before and after traveling through a chromatic dispersion compensating fibre link with an SOA device driven at 175 mA (see Figure 3). This current level was chosen arbitrarily to illustrate a code carriers’ redshift by comparing Figure 3a,b. For ease of comparison, the measurements obtained were plotted relative to the signal strength at the SOA input, i.e., a variable optical attenuator (VOA) was used to compensate for the SOA gain. This way, both graphs in Figure 3 can use an identical Y-scale. Figure 3a depicts four wavelength code carriers with 30 ps temporal separation before entering the SOA. The optical average power and carriers’ peak power was 4 mW and 57 mW, respectively. Figure 3b shows the impact of the SOA on the code integrity—the code carriers are clearly affected by a 0.73 nm wavelength redshift. A carriers’ height variation is also observed. In WDM systems, the effect of non-uniformity of the gain during a stream of pulses passing the SOA is resolved using a Lyot filter [19]. Contrary to the WDM and its regular bit rate, in 2D-WH/TS OCDMA systems, the 2D-WH/TS OCDMA code formation leads to an uneven temporal multi-wavelength code carrier’s separation. Using this solution is thus not feasible. Further analyses of Figure 3b reveal that the induced wavelength redshift has led to a code carrier ‘loss’. This is explained by inspection of Figure 3. Here, a 2D-WH/TS code composed of four wavelength code carriers is shown before entering the SOA (biased at 175 mA), after the SOA, and then again after passing a λ1–λ4 decoder. After passing the λ1–λ4 decoder with an unmatched channel spacing of 0.8 nm, the code exits distorted and with three code carries only because of the code carriers’ redshift of ~0.73 nm. The observed height differences among code carriers results in part from a non-ideal SOA gain flatness in the 1550 nm region.

Figure 3.

(a) Optical spectrum of the 2D-WH/TS OCDMA code based on four λ1 to λ4 multi-wavelength picosecond code carries before entering the SOA biased at ~175 mA; (b) after passing the SOA followed by dispersion compensated fiber link (DCF) and λ1–λ4 decoder. VOA—variable optical attenuator, OFL—optical fiber lin.

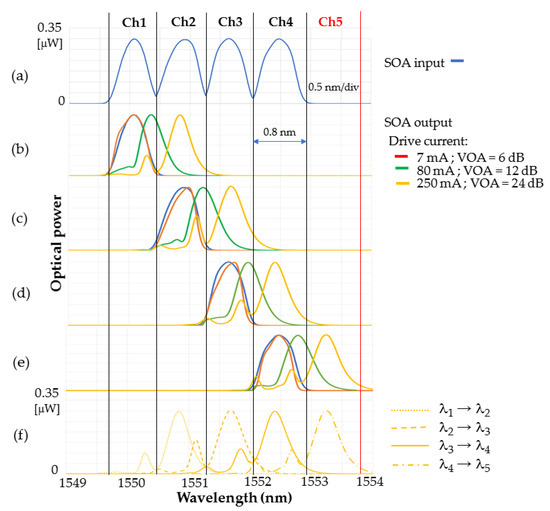

The impact of the SOA on individual wavelength code carriers will now be investigated under three different SOA driving conditions: 7 mA, 80 mA, and 250 mA, representing an SOA gain of +6 dB, +12 dB, and +24 dB, respectively. The results obtained are shown in Figure 4. For reference, Figure 4a shows all four wavelength code carriers at the input of the SOA. To graph the results obtained using an identical Y-axis scale for different SOA gain levels, a VOA was placed after the SOA, but before the OSA. The measurements obtained are shown in red, green, and yellow and represent SOA driving currents of 7 mA, 80 mA, and 250 mA, respectively. The SOA-induced redshift on individual code carriers , , and is shown in Figure 4b–d, respectively. Figure 4f shows how the entire code spectrum is affected by the SOA biased at 250 mA/24 dB gain (i.e., under the shortest gain recovery time ~30 ps (see Figure 2)).

Figure 4.

Experimental demonstration of code carriers’ wavelength redshift observed on the optical spectrum analyser: (a) code carriers at the input of the SOA; (b) effect of SOA on code carrier at an SOA current of 7 mA/6dB gain, 80 mA/12 dB gain, and 250 mA/24 dB gain, respectively; (c) similarly for ; (d) for ; (e) for ; (f) illustration of redshift on all four wavelength code carriers for an SOA current of 250 mA/24 dB gain.

In the case of 7 mA/6 dB gain, all four code carriers exhibit slight linewidth and spectral shape variations after passing the SOA and the 18.5 km long chromatic-dispersion compensated fiber link.

In the case of 80 mA/12 dB gain, the carriers’ spectra are affected by self-phase modulation (SPM). Spectral peaks shift towards the longer wavelengths (redshift), leaving a noticeable ‘trace’ in the original spectral pulse position. The amount of shifting is mainly dominated by the SOA gain and carrier density changes, causing noticeable variations in the refractive index [12]. Consequently, an SPM-induced frequency chirp is imposed on all spectral pulses as they pass the SOA [20].

In the third case of 250 mA/24 dB gain, the SOA is in its highly nonlinear regime and the pulse spectrum shifts further to the red side in addition to one or more new peaks on the blue side. These observations agree with [20]. The achieved redshift was ~100 GHz/0.8 nm.

As explained above, a matched OCDMA decoder and encoder pair are required to accurately recover the user’s data and produce an OCDMA autocorrelation peak. Based on the results in Figure 4f, this would not be possible. It can be seen that the 100 GHz spectral redshift affected all four wavelength code carriers: became , , , and . However, the matching 100 GHz lambda DMUX in the OCDMA decoder (see Figure 1) was designed to handle only (, , , ), thus it cannot recognize the newly ‘created’ wavelength resulting from the wavelength redshift. As a consequence, the number of wavelengths forming the OCDMA autocorrelation peak at the decoder output will be reduced from four to three. Furthermore, a slightly unequal amount of redshift imposed on individual wavelength code carriers is also observed. This is a result of the fact that the SOA gain is not flat and peaks at around 1550 nm [15]. Thus, multi wavelength code carriers passing the SOA experience slightly different saturation rates. This leads to a slightly different SPM, and thus amount of redshift. This was confirmed by the measurements shown in Figure 5.

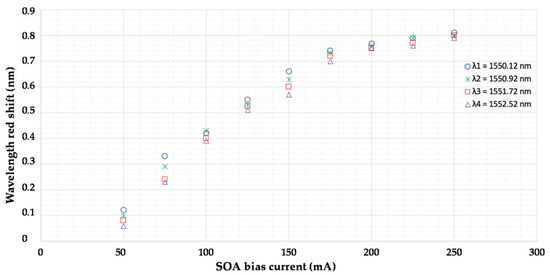

Figure 5.

The measured amount of code carriers’ wavelength redshift as a function of the SOA bias current.

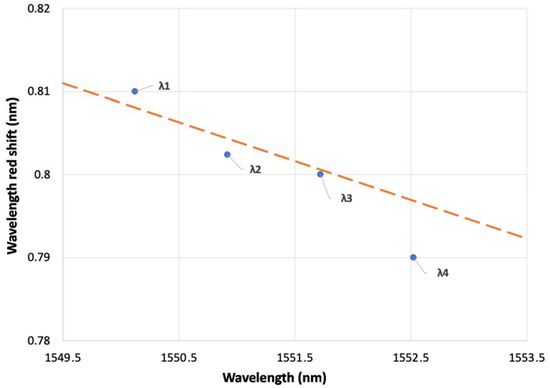

The measured amount of the code carriers’ redshift inflicted by the SOA on individual code carriers can be also found theoretically. The nonlinear effect induced by the SOA can be simulated by adopting the model described in [21]. A great deal of consistency (see Figure 5) was found between the simulated and measured results. More precise measurements would require a higher resolution OSA than the one available for the experiment, which has a resolution of 0.06 nm. The calculated slope from the measured and simulation values was found to be −0.0083 and −0.0054, respectively. This is shown in Figure 6, where the dashed line represents the simulation, while the dots are measured values.

Figure 6.

Wavelength red shift for the SOA biased at 250 mA. The dashed line is simulations and the dots are measured values for .

The multi wavelength code carriers at the input of the SOA were assumed to have a temporal Gaussian shape and measured FWHM of 7 ps ( = 4.2 ps at 1/e). The model used is applicable if the temporal pulse width of code carriers passing the SOA is ≥1 ps. The parameters used in the simulations are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Geometrical and material parameters used in the simulation.

3. Impact of SOA High Bias Current/Gain on 2D-WH/TS OCDMA Prime Code Fidelity

Here, the investigation was repeated by replacing the DWDM-based OCDMA encoder and decoder with a commercial fiber Bragg grating-based encoder and decoder manufactured by OKI, Japan. The implemented 2D-WH/TS OCDMA carrier-hopping prime code (CHPC) [2] is optimised to ensure that the periodic cross correlation function is at most one [2]. This minimises the multiple-access interference. The encoder/decoder pair uses four wavelength code carriers from a code space (w, N) = (4, 53), where w indicates a number of wavelength code carriers with a channel spacing of 100 GHz and N is the number of chips [3] per the bit period. The code signature (1-, 21-, 27-, 39-) guarantees a minimal separation between adjacent code carriers of more than 30 ps. The SOA bias current/gain and code average/code carriers’ peak power at the SOA input were 250 mA/24 dB and 4 mW/57 mW, respectively, resulting in a 100 GHz/0.8 nm code carriers’ redshift. The results obtained are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a is the OCDMA code optical spectrum recorded by the OSA without, and Figure 7b with an SOA being part of the chromatic dispersion compensated transmission link. By comparing both results, it can be observed that wavelength code carriers were red-shifted by 100 GHz/ 0.8 nm. As explained in Section 2, because of this redshift, became , , , and . However, the OCDMA fiber Bragg grating (FBG) decoder was designed to handle only (, , , ). Therefore, the wavelength resulted from the redshift is ‘missing’ in Figure 7b. As a consequence, the resulting OCDMA autocorrelation height will be reduced by one to its new value w − 1. This code weight reduction will decrease the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and cause deterioration in the OCDMA system bit-error-rate (BER), which in turn reduces the number of simultaneous users. The performance degradation resulting from the code carriers’ red-shifting can be theoretically evaluated using Equation (1) to calculate the probability of error Pe. Equation (1) is valid for an OCDMA receiver with hard limiting capabilities [3]. Pe can be used to evaluate the number of simultaneous users (K).

Figure 7.

Impact of SOA on 2D-WH/TS code based on four-wavelength code carriers as recorded by an optical spectrum analyser: (a) without and (b) with the SOA present in the chromatic-dispersion (CD) compensated transmission link.

Here, , w is the code weight, L is a number of wavelength code carriers (in this case w = L), and N is the number of chips.

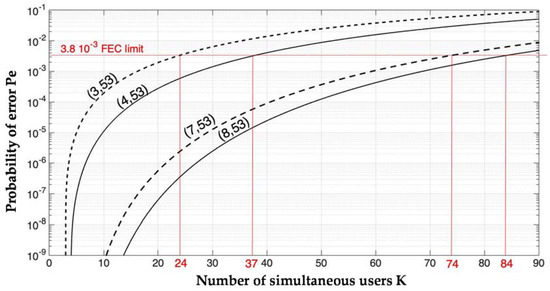

The results obtained are shown in Figure 8. Solid lines show the probability of error of two different 2D-WH/TS OCDMA systems: one that has four wavelength code carriers (w = 4) and N = 53 chips, denoted by (w, N) = (4, 53), and the second, having w = 8 and N = 53, denoted by (8, 53). Dashed lines represent calculations of the respective degraded Pe due to the code carrier redshift, which causes autocorrelation peak reduction from w to w − 1 (i.e., from 4 to 3 and from 8 to 7, respectively).

Figure 8.

Probability of error as a function of K simultaneous users for a (4, 53)/(3, 53) and (8, 53)/(7, 53) 2D-WH/TS OCDMA system without/with the deployment of an SOA, respectively, the latter causing a one channel code carriers’ redshift.

4. Discussion

As shown in Figure 5, the SOA driving current variations between 50 mA and 250 mA will result in a 2D-WH/TS code carriers’ redshift from 0.08 to 0.8 nm. By analysing the results in Figure 8, the impact of the SOA-induced redshift on the OCDMA system performance and number of simultaneous OCDMA users was found. First, the OCDMA system performance was determined for the (8, 53) OCDMA without the presence of SOA. The system supports 14 simultaneous users, each operating at Pe of 10−9. Thanks to OCDMA soft-blocking capabilities, one can readily trade the system’s Pe for a number of simultaneous users and then take advantage of the implemented hard-decision forward error correction (HD-FEC) with 7% overhead. By doing so, the number of simultaneous users will be increased (up to 84) by allowing a drop in the Pe to 3.8 × 10−3 and then in turn using FEC to return the Pe back to 10−9 (see Figure 8). However, the SOA present in the transmission link driven at 250 mA leads to the code carriers’ redshift of 0.8 nm equal to their channel spacing. As a consequence, the system’s OCDMA autocorrelation is reduced by 1 (from 8 to 7) and the (8, 53)-OCDMA system now performs only as (7, 53)-OCDMA. This will result a drop in the number of simultaneous users from 14 to 10 or 84 to 74 with the FEC Pe of 10−9, respectively. Similar performance degradation is demonstrated for a (4, 53)-OCDMA when the system operates under the same experimental conditions. The SOA’s 250 mA driving current-induced redshift of 0.8 nm equal to code carriers channel spacing causes a drop in the number of simultaneous users from 4 to 3 or 37 to 24 with the FEC Pe of 10−9, respectively. Thus, the (4, 53)-OCDMA system only performs as (3, 53)-OCDMA to maintain the Pe of 10−9.

5. Conclusions

The impact of SOA-induced wavelength redshift on 2D-WH/TS multi wavelength picosecond code carriers was investigated for the first time. For the SOA bias current of 50 to 250 mA, the amount of induced redshift was found to be 0.08 to 0.8 nm. Next, the detrimental effect of 0.8 nm redshift on (8, 53)- and (4, 53)-WH/TS OCDMA systems was investigated. It can be stated that, when the amount of SOA-induced redshift is equal to the code carriers’ wavelength channel spacing, then a (w, N)-WH/TS OCDMA system will only perform as a (w − 1, N)-WH/TS OCDMA system to maintain the Pe of 10−9.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.A.K. and A.L.S.; formal analysis, M.A., A.L.S. and I.G.; investigation, M.A. and U.A.K.; Methodology, M.A.; resources, I.G.; Software, M.A. and W.C.K.; supervision, I.G.; validation, M.A., W.C.K. and I.G.; writing—original draft, M.A.; writing—review & editing, A.L.S., W.C.K. and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie under Grant 734331.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, G.-C.; Kwong, W.C. Prime Codes with Applications to CDMA Optical and Wireless Networks; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R. Design and performance analysis of 1D, 2D and 3D prime sequence code family for optical CDMA network. J. Opt. 2016, 45, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W.C.; Yang, G.-C. Optical Coding Theory with Prime; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wonfor, A.; Wang, H.; Penty, R.V.; White, I.H. Large port count high-speed optical switch fabric for use within datacentres. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2011, 3, A32–A39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.; Kaler, R.S. Performance evaluation of EDFA, RAMAN and SOA optical amplifier for WDM systems. Opt. ELSEVIER 2013, 124, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Glesk, I. Management of OCDMA Auto-Correlation Width by Chirp Manipulation Using SOA. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2018, 30, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Hong, W.; Huang, D. Experimental study of SOA-based NRZ-to-PRZ conversion and distortion elimination of amplified NRZ signal using spectral filtering. Opt. Commun. 2008, 281, 5618–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, R.; Albores-Meija, A.; Rohit, A.; Williams, K.A. Integrated optical switch matrices for packet data networks. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2016, 2, 15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glesk, I.; Sokoloff, J.P.; Prucnal, P.R. Demonstration of all-optical demultiplexing of TDM data at 250 Gbit/s. Electron. Lett. 1994, 30, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Ghafouri-Shiraz, H.; Hou, L.; Kelly, A.E. High-speed pulse train amplification in semiconductor optical amplifiers with optimized bias current. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, G.P. Fiber-Optic Communication Systems, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baveja, P.P.; Maywar, D.N.; Kaplan, A.M.; Agrawal, G.P. Self- Phase modulation in semiconductor optical amplifiers: Impact of amplified spontaneous emission. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2010, 46, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A.D.; Ibsen, M.; Horak, P.; Thomsen, B.C.; Richardson, D.J. Feasibility study of SOA-base noise suppression for spectral amplitude coded OCDMA. J. Lightwave Technol. 2007, 25, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.B. Tunable photonic microwave notch filter using SOA-based single-longitudinal mode dual-wavelength laser. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 13216–13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OPA-20-N-C-FA, 1550 nm Nonlinear SOA From Kamelian. Available online: http://www.kamelian.com/data/opa_15_ds.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2009).

- Ummy, M.A.; Bikorimana, S.; Madamopoulos, N.; Dorsinville, R. Beam Combining of SOA-Based Bidirectional Tunable Fiber Nested Ring Lasers With Continuous Tunability Over the C-band at Room Temperature. J. Lightwave Technol. 2016, 34, 3703–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlabs. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/newgrouppage9.cfm?objectgroup_id=3901 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Liu, Y.; Tangdiongga, E.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; de Waardt, H.; Khoe, G.D.; Dorren, H.J. Error-free all-optical wavelength conversion at 160 gb/s using a semiconductor optical amplifier and an optical bandpass filter. J. Lightwave Technol. 2006, 24, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoiros, K.E.; O’Riordan, C.; Connelly, M.J. Semiconductor optical amplifier pattern effect suppression using Lyot filter. Electron. Lett. 2009, 45, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, N.A.; Agrawal, G.P. Spectral shift and distortion due to self-phase modulation of picosecond pulses in 1.5 pm optical amplifiers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1989, 55, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.P.; Olsson, N.A. Self-phase modulation and spectral broadening of optical pulses I semiconductor laser amplifiers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1989, QE-25, 2297–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, M.J. Wideband semiconductor optical amplifier steady-state numerical model. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2001, 37, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, A.M.; Petermann, K. On the amplified emission noise modelling of semiconductor optical amplifiers. Opt. Commun. 2008, 281, 4598–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguet, C. Homogeneous buried ridge stripe semiconductor optical amplifier with near polarization independence. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Optical Communication, Nice, France, 26–30 September 1999; pp. 46–47. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).